SUMMARY

Autocrine, paracrine and juxtacrine are recognized modes of action for mammalian EGFR ligands that include EGF, TGF-α (TGFα), amphiregulin (AREG), heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor (HB-EGF), betacellulin, epiregulin and epigen. We identify a new mode of EGFR ligand signaling via exosomes. Human breast and colorectal cancer cells release exosomes containing full-length, signaling-competent EGFR ligands. Exosomes isolated from MDCK cells expressing individual full-length EGFR ligands displayed differential activities; AREG exosomes increased invasiveness of recipient breast cancer cells four-fold over TGFα or HB-EGF exosomes and five-fold over equivalent amounts of recombinant AREG. Exosomal AREG displayed significantly greater membrane stability than TGFα or HB-EGF. An average of 24 AREG molecules are packaged within an individual exosome, and AREG exosomes are rapidly internalized by recipient cells. Whether the composition and behavior of exosomes differ between non-transformed and transformed cells is unknown. We show that exosomes from DLD-1 colon cancer cells with a mutant KRAS allele exhibited both higher AREG levels and greater invasive potential than exosomes from isogenically matched, non-transformed cells in which mutant KRAS was eliminated by homologous recombination. We speculate that EGFR ligand signaling via exosomes may contribute to diverse cancer phenomena such as field effect and priming the metastatic niche.

Keywords: Exosomes, EGF Receptor, amphiregulin, TGF-α, HB-EGF

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

EGFR ligands are present in exosomes

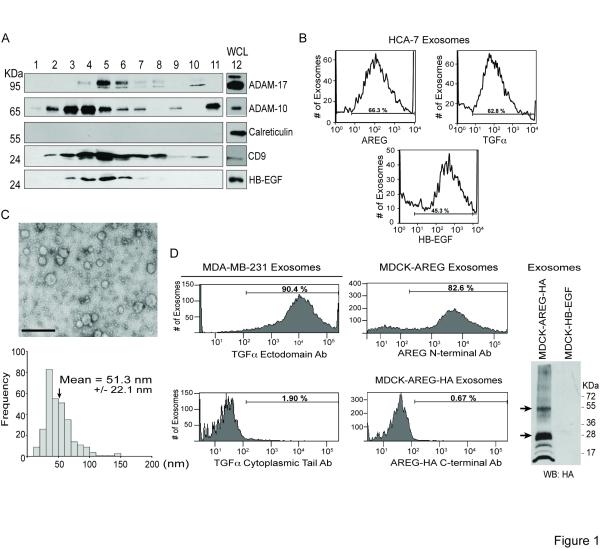

EGFR ligands are produced as type 1 transmembrane proteins [1]. How they are trafficked, processed and released determine the range, amplitude and duration of downstream EGFR signaling [2]. This study was spurred by our detection of full-length HB-EGF in the conditioned medium of MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells without its presence at the plasma membrane (PM) (not shown). EGFR ligands act as soluble autocrine and paracrine factors or in a juxtacrine manner as full-length, uncleaved, cell surface ligands [3, 4]. However, we hypothesized extracellular release of HB-EGF in exosomes might explain our observation. Exosomes are 30-100 nm extracellular nanovesicles produced by intralumenal budding of multivesicular bodies (MVB) and MVB-PM fusion [5]. We purified <200 nm extracellular vesicles from MDA-MB-231 cell conditioned medium by sucrose gradient fractionation (Experimental Procedures). These fractions were immunoblotted; fractions 4-6 contained peak levels of HB-EGF and exosomal proteins CD9, ADAM-10 and ADAM-17 [6, 7], but were negative for the ER marker calreticulin (Figure 1A). Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) of fractions 4-6 shows 30-50 nm vesicles with morphology characteristic of exosomes (Figure S1A) [5].

Figure 1.

Biochemical analysis of exosomes isolated from MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells, HCA-7 colon cancer cells and MDCK cells stably expressing EGFR ligands. (A) Extracellular vesicles were purified from MDA-MB-231 conditioned medium by sucrose gradient fractionation (Experimental Procedures). Fractions 1-11 and whole cell lysate (WCL), lane 12, were separated by SDS-PAGE, and equal volumes were immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. (B) Representative histograms from FAVS analysis of exosomes isolated from HCA-7 cells using the indicated ectodomain antibodies. Horizontal bars represent the gate with the percent of positive exosomes indicated. (C) Relative size of AREG exosomes. Three independent exosome preparations from MDCK cells stably expressing AREG were negatively stained and viewed by TEM. A representative field image (upper) shows vesicles with a smooth, saucer-like morphology characteristic of exosomes. The mean diameter of 300 vesicles was calculated from TEM images. Scale bar represents 250 nm. (D) Topology of endogenous TGFα and heterologous AREG in exosomes. Exosomes from MDA-MB-231 cells (left panel) were subjected to FAVS analysis using antibodies against the ectodomain (top) and cytoplasmic tail (bottom) of TGFα. Exosomes from MDCK cells expressing full-length AREG with a C-terminal HA tag (middle panel) were subjected to FAVS analysis using an AREG ectodomain antibody (top) or an HA antibody (bottom). Horizontal bars represent the gate with the percent of positive exosomes indicated. Right panel, exosomes were isolated from conditioned medium of MDCK cells stably expressing HA-tagged AREG or HB-EGF and immunoblotted with an anti-HA antibody to detect full-length AREG (arrows).

To determine if other EGFR ligands were localized in these extracellular vesicles, we utilized fluorescence-activated vesicle sorting (FAVS). We developed this approach to isolate small (<100 nm) vesicles [8] and to perform vesicle-by-vesicle analysis, avoiding signal loss due to bulk measurements and signal averaging. HB-EGF and TGFα were detected in extracellular vesicles purified from MDA-MB-231 cells and HCA-7 colorectal cancer cells, whereas AREG was detected only in HCA-7 vesicles (Figures 1B and S1B). These results provide the first evidence that EGFR ligands are released in extracellular vesicles.

To be more confident that EGFR ligand-containing extracellular vesicles are exosomes, whole cell lysates (WCL) or vesicle preparations from the conditioned medium of MDCK cells stably expressing AREG (MDCK AREG) were immunoblotted for AREG, exosomal markers (Hsp-70 [9-11], Tsg101 [12, 13] and flotillin-1 [14-16]), nuclear markers (lamin a/c and poly [ADP-ribose] polymerase [PARP]), the ER marker (calreticulin) and the mitochondrial marker (voltage-dependent anion channel [VDAC]). The vesicle preparations contained exosomal markers, but not the other organelle markers (Figure S1B), supporting the idea that these vesicles are exosomes. Furthermore, the calculated mean diameter from three independent sets of vesicles from the conditioned medium of MDCK AREG cells was 51.3 nm (Figure 1B and C), a size previously described as characteristic of exosomes [5]. We detected only scattered vesicles larger than 100 nm and little cellular debris. We cannot exclude the possibility that our extracellular vesicle preparations also contain shedding vesicles. However, shed vesicles are classically defined as up to 1 μm in diameter; smaller shedding vesicles have been described, but they are typically not less than 100-200 nm [17]. Therefore, based on their size (Figures 1C and S1A) and composition (Figures 1A and S1C), our vesicle preparations appear to be highly enriched for exosomes.

Utilizing FAVS, we tested whether exosomal EGFR ligands were full-length and displayed in a proper orientation to engage receptor on recipient cells. Using N- or C-terminus-specific antibodies, we found the N-terminus of endogenous TGFα on the outside of MDA-MB-231 exosomes and heterologous AREG on the outside of exosomes from MDCK cells expressing wild-type AREG or C-terminally HA-tagged AREG (Figure 1D). These results demonstrate that exosomal TGFα and AREG are in a signaling-competent orientation such that the N-terminus is available to engage recipient cell EGFR.

AREG-containing exosomes induce recipient cell invasion

To examine the function of individual EGFR ligands, we purified exosomes from parental MDCK cells expressing undetectable levels of EGFR ligands [18] and MDCK cells overexpressing HB-EGF, TGFα or AREG. As a functional readout of exosome activity, we assessed the effect of exosomes on recipient cancer cell invasion, a hallmark of malignancy. Using a modified Boyden chamber assay, AREG exosomes stimulated similar levels of invasion for MDA-MB-231-derived LM2-4175 and LMO-1833 recipient cells that metastasize to lung and bone, respectively [19]; results from LM2-4175 cells are shown. We determined exosomes purified from the conditioned medium of MDCK cells overnight or after two-hr exposure to ionomycin exhibited identical invasive effects; thus, these two preparations were pooled in all subsequent experiments (Figure S2A).

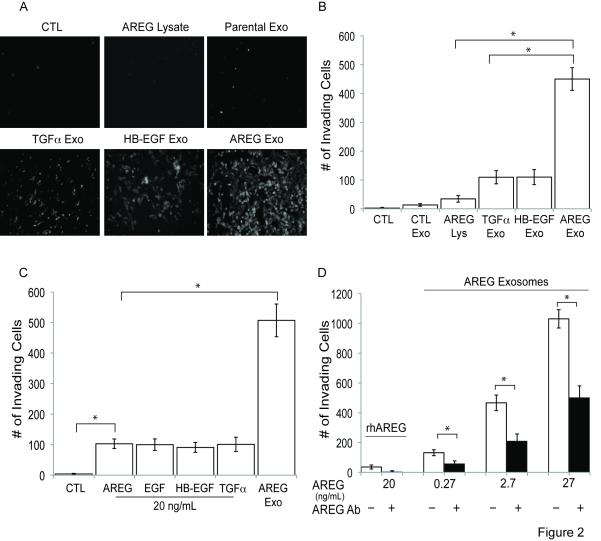

For the invasion assays, LM2-4175 cells were treated with serum-free medium alone or with the following supplements: MDCK AREG WCL or parental, HB-EGF, TGFα or AREG exosomes. Treatment-containing, serum-free medium was replaced every 24 hrs, and the number of cells that invaded through Matrigel to the undersurface of Transwell filters was quantified after 72 hrs. LM2-4175 cell invasion was not affected by serum-free medium, and increases in serum concentration increased invasion (not shown). When viewed microscopically and quantified, AREG exosomes enhanced invasiveness of LM2-4175 cells four-fold over TGFα or HB-EGF exosomes and five-fold over parental MDCK exosomes or MDCK AREG WCL (Figure 2A and B). From two experiments performed in duplicate, the concentration per mg of exosomal protein was 793.5 ng of AREG, 749 ng of TGFα and 931.5 ng of HB-EGF, suggesting similar amounts of the ligands in MDCK cell exosomes. Thus, differences in exosomal ligand concentration cannot explain the greater invasive potential of AREG exosomes.

Figure 2.

Exosomes from AREG-expressing MDCK cells induce the highest invasive activity in recipient breast cancer cells. (A and B) LM2-4175 cells were incubated for 2 hrs with serum-free medium containing 100 μg/mL BSA (CTL), 100 μg/mL of MDCK-AREG WCL, 100 μg/mL of parental MDCK cell exosomes, TGFα exosomes, HB-EGF exosomes or AREG exosomes. Cells then were plated in a Matrigel-coated Boyden chamber, and the numbers of cells on the bottom of Transwell filters was imaged (A) or quantified (B) after 72 hrs (Experimental Procedures). (B) Data represent the mean +/− the SD. (C) LM2-4175 cells were incubated with exosomes containing 20 ng/mL of AREG as measured by ELISA or 20 ng/mL recombinant human ligands, a similar concentration of AREG found in MDCK exosomes as measured by ELISA. Data represent the mean +/− the SD. (D) LM2-4175 cells were treated with increasing concentrations of AREG exosomes with or without pretreatment with an AREG neutralizing monoclonal antibody, 6R1C2.4 (20 μg/mL). Data represent the mean +/− SD. p < 0.0001 (*).

We next compared the invasive potential of AREG exosomes to recombinant ligands. By ELISA, the concentration of AREG exosomes was 20 ng/mL (Experimental Procedures). At this concentration of exosomal AREG and recombinant ligands, AREG exosomes increased the number of invading LM2-4175 cells five-fold more than recombinant ligands (Figure 2C). In a dose-response experiment, 100 ng/mL recombinant AREG did not achieve the invasive effect of 20 ng/ml AREG exosomes (Figures S2B and 2C). In a separate experiment, AREG exosomes enhanced wound healing compared to serum-free control or recombinant AREG (Figure S2C). Combined, these results demonstrate AREG exosomes impart greater recipient cell invasiveness compared to parental MDCK exosomes, exosomes containing other EGFR ligands or recombinant EGFR ligands.

To address how much of the effect of AREG exosomes is due to AREG itself, recombinant AREG or AREG exosomes were treated with or without AREG neutralizing antibody for one hr prior to incubation with LM2-4175 cells. Regardless of exosome concentration, AREG neutralizing antibody reduced the number of invasive cells by approximately 50% (Figure 2D). Since all known biological effects of AREG are mediated by binding to EGFR, our results suggest the invasive effect of AREG exosomes is due, at least in part, to exosomal AREG activation of recipient cell EGFR. A similar effect was found when recipient LM2-4175 cells were treated for one hr prior to AREG exosome incubation with an EGFR neutralizing monoclonal antibody (mAb 528) (not shown), which also decreases exosomal internalization (see below).

Exosomal AREG stability and packaging

To begin addressing why AREG exosomes impart enhanced invasiveness compared to TGFα or HB-EGF exosomes, we tested the stability of exosomal EGFR ligands. The levels of membrane-bound ligands were determined by ELISA in the presence or absence of the metalloprotease inhibitor galardin at one and 24 hrs [20]. There is little difference in the percent of exosomal AREG at one or 24 hrs compared to TGFα or HB-EGF (Table S1), suggesting AREG exhibits greater membrane stability in exosomes than TGFα or HB-EGF, likely due to its resistance to membrane cleavage despite the presence of mature, active ADAM-10 and ADAM-17 in exosomes (Figure 1A and [6]).

We utilized quantitative confocal microscopy to determine how many molecules of AREG are present in a single exosome. Fluorescent intensity of individual exosomes purified from MDCK cells stably expressing EGFP-tagged AREG (AREG-EGFP exosomes) was correlated to the number of AREG-EGFP molecules by comparison to known concentrations of purified EGFP protein. A histogram of the AREG-EGFP molecules per exosome shows an average of 24 AREG-EGFP molecules (24.0 ± 7.6) present in an individual exosome (Figure 3A). We speculate that both the relative membrane stability and compact packaging within exosomes contribute to the enhanced invasive effect of AREG exosomes.

Figure 3.

Compact packaging and rapid internalization of AREG exosomes. (A) Exosomes were isolated from conditioned medium of MDCK cells stably expressing EGFP-tagged AREG. The number of GFP molecules per exosome was determined as described in Experimental Procedures. Each exosome contains approximately 24 AREG molecules. (B) DiD-stained exosomes were purified from wild-type AREG-expressing MDCK cells and incubated with LM2-4175 cells for the indicated times. Flow cytometric analysis was performed as described in Experimental Procedures. Data represent the mean +/− SD. p < 0.005 (**). (C) Exosomes from non-tagged AREG-expressing MDCK cells were incubated with the fluorescent membrane stain DiD. LM2-4175 recipient cells were incubated with DiD-labeled AREG exosomes for the indicated times and uptake visualized by confocal microscopy. Scale bars represent 5 μm. (D) Exosomes from C-terminally EGFP-tagged AREG-expressing MDCK cells were purified and incubated with LM2-4175 cells for 30 min and internalization monitored by GFP fluorescence using confocal microscopy. Two xz planes are shown: apical surface (upper) and mid-cell (lower). Scale bars represent 5 μm. (E) LM2-4175 cells were pretreated in the presence (EGFR mAb) or absence (CTL) of 20 μg/mL EGFR mAb 528 for one hr and then incubated with DiD-stained AREG exosomes for 10 min. Flow cytometric analysis was performed as described in Experimental Procedures. Data represent the mean +/− SD. p<0.0001 (*).

AREG exosomes are rapidly internalized

To begin characterizing the interaction of exosomes with recipient cells, we tested whether LM2-4175 cells internalize AREG exosomes. LM2-4175 cells were incubated for one-60 min with AREG exosomes stained with DiD, a fluorescent, lipophilic, membrane diffuse dye. By flow cytometry, we determined the initial recipient cell mean DiD fluorescent intensity. Cells were then incubated with Sudan Black to quench surface-bound DiD, and flow cytometry was repeated to quantitate the percent of cells with internalized DiD-stained exosomes. The majority of cells internalized exosomes by 10 min, indicating rapid uptake (Figure 3D). At this time point, recipient cell pretreatment with the EGFR mAb 528 resulted in a 50% decrease in percent quenched total DiD mean intensity (Figure 3E), suggesting AREG exosome internalization is mediated, at least in part, by recipient cell EGFR.

To substantiate exosome internalization by recipient cells, DiD-stained AREG exosomes or AREG-EGFP exosomes were co-incubated with LM2-4175 cells for 30 min, PM stained with concanavalin A (ConA) and internalization viewed by confocal microscopy. The results suggest AREG exosomes are internalized as indicated by the intracellular punctate, vesicle-like structures in the xy (Figure 3C and D) and xz (Figure 3D, Movies S1 and S2) planes. Thus, visualization of exosomal membranes and epitope-tagged AREG demonstrates internalization of AREG exosomes.

Mutant KRAS status correlates with exosomal AREG levels and invasive potential

Exosomes are detected in the serum of cancer patients [5, 10]; however, it is unknown whether differences in the composition and behavior of exosomes exist between normal and transformed cells. To test this, we examined the composition of exosomes from a colorectal cancer cell line, DLD-1, containing one wild-type and one mutant activated KRAS allele and its isogenic derivatives in which the mutant allele (DKs-8) or wild-type allele (DKO-1) was eliminated by homologous recombination [21]. In contrast to their transformed counterparts, DKs-8 cells do not grow in soft agar or form tumors in nude mice. The EGFR ligand composition of DLD-1 cell exosomes was examined by FAVS; 42% stained individually for TGFα, 58.5% for HB-EGF, 84.3% for AREG, whereas 28.5% of exosomes contained all three ligands (Table S2). These results suggest there are different exosome populations in these cells containing varying amounts of EGFR ligands.

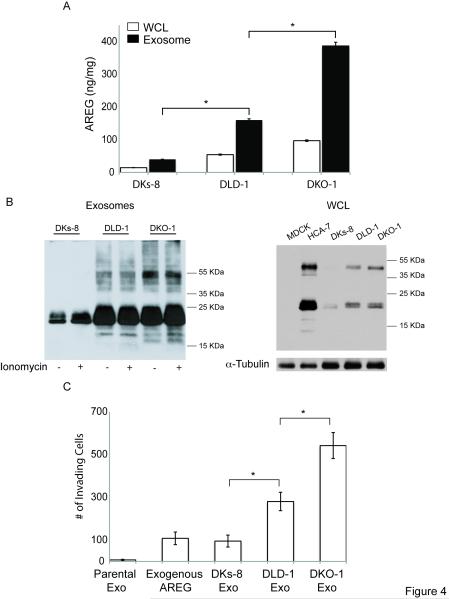

We next determined how much AREG was in exosomes and WCL from DLD-1, DKO-1 and DKs-8 cells. Figure 4A shows a higher concentration of AREG in exosomes compared to WCL in DLD-1 cells and its isogenic variants. Furthermore, there is an enrichment of AREG in the exosomes of cells with a mutant KRAS allele (DLD-1 and DKO-1). AREG immunoblotting of exosomes and WCL (Figures 4B and S4) correlated with the AREG ELISA results (Figure 4A). The slower migrating bands above the 55 KDa AREG isoform in DKO-1 and DLD-1 exosomes may represent a post-translational modification (Figure 4B), but future studies are needed to substantiate this possibility.

Figure 4.

Mutant KRAS colon cancer cells have higher exosomal AREG protein levels, and mutant KRAS exosomes increase invasiveness of recipient cells. (A) Whole cell lysates (WCL) or exosomes were isolated from the indicated cell lines, and the concentration of AREG was determined by ELISA. Data represent the mean +/− SD. (B) AREG Western blots of exosomes or WCL. (C) LM2-4175 cells were pretreated with or without 20 μg/mL of AREG neutralizing antibody, and the previously described invasion assay was performed. Data represent the mean +/− SD. p < 0.001 (*)

We next addressed whether the KRAS mutant allele status of donor cell lines correlates with exosome-induced invasiveness of recipient cells. Figure 4C shows a correlation between levels of exosomal AREG and ability to enhance invasion of recipient cells. Together, these data show AREG is enriched in exosomes from mutant KRAS cells, and these exosomes increase recipient cancer cell invasion, supporting previous reports implicating a possible tumor suppressor role for wild-type KRAS [22, 23].

In summary, we show multiple cell lines produce exosomes containing EGFR ligands displayed in a signaling-competent orientation. AREG exosomes enhance invasion of recipient cells compared to TGFα and HB-EGF exosomes and equivalent amounts of recombinant AREG. A single exosome contains an average of 24 membrane-stable AREG molecules, and AREG exosomes are rapidly internalized by recipient cells, which is, at least in part, dependent on AREG-EGFR binding. We postulate exosomes are multivalent EGFR ligand signaling platforms, whereby exosomal packaging acts to concentrate AREG in a manner allowing aggregation and oligomerization of recipient cell EGFR during ligand engagement. We propose ExTRAcrine (Exosomal Targeted Receptor Activation) as a new mode of EGFR ligand signaling that may act in local or distant environments (see below). In addition, we show isogenically matched non-transformed and transformed cells differ in the composition and behavior of their exosomes; mutant KRAS status correlates with increased exosomal AREG levels and invasiveness of recipient cells.

These results raise intriguing possibilities about the role(s) of exosomes in cancer. Cancer cell exosomes may act locally and contribute to the well-recognized, but poorly understood, cancer field effect [24, 25]. In addition, exosomes secreted by tumor cells may enter the bloodstream and deposit in distant sites, providing a hospitable environment (“priming the metastatic niche”) for circulating EGFR-overexpressing tumor cells to lodge [26, 27]. Future studies will test these and other possibilities, including additional biological effects of exosomes and the attendant signaling cascades they initiate.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Reagents and Antibodies

All cell culture reagents were from HyClone (Logan, UT) unless otherwise stated. Fluorescent probes, including propidium iodide (PI), 1,1′-dioctadecyl-3,3,3′,3′-tetramethyl-indodi-carbocyanineperchlorate (DiD) and all secondary antibodies used in FAVS, were purchased from Invitrogen-Molecular Probes (Carlsbad, CA). The AREG ectodomain antibody 6R1C2.4 [28, 29] was obtained from Bristol Myers Squib (Seattle, WA). The TGFα antibody was made in collaboration with Covance (Princeton, NJ), and the TGFα ectodomain antibody was made in collaboration with East Acres Biologicals (Southbridge, MA) [30, 31]. The mouse HB–EGF antibody (MAB259) was purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). Dr. Hideo Masui (Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center) generously provided the EGFR mouse monoclonal antibody 528. The human AREG-, TGFα- and HB-EGF-specific sandwich ELISA kits were purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). Polyclonal antibodies to ADAM-10 and ADAM-17 were purchased from Chemicon. Mouse monoclonal antibodies to hsp70, lamin a/c and CD9, rabbit polyclonal antibody to PARP and goat polyclonal antibody to calreticulin were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). The rabbit polyclonal antibody to VDAC was purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, MA). The mouse monoclonal antibodies to Tsg101 and flotillin-1 were obtained from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA). All other chemicals and antibodies were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO).

Isolation of Exosomes

Native and elicited exosome pellets were pooled and subjected to sucrose gradient fractionation or differential centrifugation as described in Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Electron Microscopy

Biochemical Analysis

For immunoblotting, SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions was used for all blots except for AREG blots, which were separated under non-reducing conditions. Standard conditions were used to electrotransfer samples to Immunobilon nitrocellulose or PVDF membranes, and blots were blocked with non-fat milk or BSA in TBS-T according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Blots were probed with the indicated antibodies.

Fluorescence-activated Vesicle Sorting (FAVS)

FAVS analysis was performed as previously described [8, 32]. For a more detailed description, see Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Invasion Assay

LM2-4175 cells were cultured in complete DMEM supplemented with 10% bovine growth serum to 70% confluence, washed three times with PBS and then maintained overnight in serum-free DMEM. Invasion was assessed by a modified Boyden chamber assay and a modified wound-healing assay (detailed in Supplemental Experimental Procedures).

Confocal Microscopy

Quantitative Assay of EGFP Molecules

For quantification of the number of AREG-EGFP molecules per exosome, four μl of a purified exosome suspension was sandwiched between a glass slide and a poly-L-lysine-coated 22-mm square cover slip. The poly-L-lysine coating was used to immobilize the exosomes. For further details on image capture and processing, see Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Statistics

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by NCI CA46413, GI Special Program of Research Excellence P50 95103 to RJC, GM72048 to DWP, R01 DK075555 to MJT and NCI 1R25 CA92043 to MDB. Flow cytometry experiments were performed in the Vanderbilt University Flow Cytometry Shared Resource. The Vanderbilt University Flow Cytometry Shared Resource is supported by the Vanderbilt Ingram Cancer Center (P30 CA68485) and the Vanderbilt Digestive Disease Research Center (DK058404). We acknowledge Melissa Chambers for technical assistance, as well as Melanie Ohi and the Vanderbilt University Center for Structural Biology for use of the TEM.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Singh AB, Harris RC. Autocrine, paracrine and juxtacrine signaling by EGFR ligands. Cell Signal. 2005;17:1183–1193. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2005.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chung E, Graves-Deal R, Franklin JL, Coffey RJ. Differential effects of amphiregulin and TGF-alpha on the morphology of MDCK cells. Exp Cell Res. 2005;309:149–160. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2005.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harris RC, Chung E, Coffey RJ. EGF receptor ligands. Exp Cell Res. 2003;284:2–13. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4827(02)00105-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schneider MR, Wolf E. The epidermal growth factor receptor ligands at a glance. J Cell Physiol. 2009;218:460–466. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schorey JS, Bhatnagar S. Exosome function: from tumor immunology to pathogen biology. Traffic. 2008;9:871–881. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2008.00734.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stoeck A, Keller S, Riedle S, Sanderson MP, Runz S, Le Naour F, Gutwein P, Ludwig A, Rubinstein E, Altevogt P. A role for exosomes in the constitutive and stimulus-induced ectodomain cleavage of L1 and CD44. Biochem J. 2006;393:609–618. doi: 10.1042/BJ20051013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thery C, Regnault A, Garin J, Wolfers J, Zitvogel L, Ricciardi-Castagnoli P, Raposo G, Amigorena S. Molecular characterization of dendritic cell-derived exosomes. Selective accumulation of the heat shock protein hsc73. J Cell Biol. 1999;147:599–610. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.3.599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cao Z, Li C, Higginbotham JN, Franklin JL, Tabb DL, Graves-Deal R, Hill S, Cheek K, Jerome WG, Lapierre LA, et al. Use of fluorescence-activated vesicle sorting for isolation of Naked2-associated, basolaterally targeted exocytic vesicles for proteomics analysis. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2008;7:1651–1667. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M700155-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cho JA, Lee YS, Kim SH, Ko JK, Kim CW. MHC independent anti-tumor immune responses induced by Hsp70-enriched exosomes generate tumor regression in murine models. Cancer Lett. 2009;275:256–265. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Niel G, Porto-Carreiro I, Simoes S, Raposo G. Exosomes: a common pathway for a specialized function. J Biochem. 2006;140:13–21. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvj128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhan R, Leng X, Liu X, Wang X, Gong J, Yan L, Wang L, Wang Y, Qian LJ. Heat shock protein 70 is secreted from endothelial cells by a non-classical pathway involving exosomes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;387:229–233. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.06.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thery C, Boussac M, Veron P, Ricciardi-Castagnoli P, Raposo G, Garin J, Amigorena S. Proteomic analysis of dendritic cell-derived exosomes: a secreted subcellular compartment distinct from apoptotic vesicles. J Immunol. 2001;166:7309–7318. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.12.7309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thery C, Zitvogel L, Amigorena S. Exosomes: composition, biogenesis and function. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:569–579. doi: 10.1038/nri855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Gassart A, Geminard C, Fevrier B, Raposo G, Vidal M. Lipid raft-associated protein sorting in exosomes. Blood. 2003;102:4336–4344. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-03-0871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chairoungdua A, Smith DL, Pochard P, Hull M, Caplan MJ. Exosome release of beta-catenin: a novel mechanism that antagonizes Wnt signaling. J Cell Biol. 2010;190:1079–1091. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201002049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Trajkovic K, Hsu C, Chiantia S, Rajendran L, Wenzel D, Wieland F, Schwille P, Brugger B, Simons M. Ceramide triggers budding of exosome vesicles into multivesicular endosomes. Science. 2008;319:1244–1247. doi: 10.1126/science.1153124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cocucci E, Racchetti G, Meldolesi J. Shedding microvesicles: artefacts no more. Trends Cell Biol. 2009;19:43–51. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dempsey PJ, Coffey RJ. Basolateral targeting and efficient consumption of transforming growth factor-alpha when expressed in Madin-Darby canine kidney cells. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:16878–16889. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Minn AJ, Gupta GP, Siegel PM, Bos PD, Shu W, Giri DD, Viale A, Olshen AB, Gerald WL, Massague J. Genes that mediate breast cancer metastasis to lung. Nature. 2005;436:518–524. doi: 10.1038/nature03799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Agren MS, Mirastschijski U, Karlsmark T, Saarialho-Kere UK. Topical synthetic inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinases delays epidermal regeneration of human wounds. Exp Dermatol. 2001;10:337–348. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0625.2001.100506.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shirasawa S, Furuse M, Yokoyama N, Sasazuki T. Altered growth of human colon cancer cell lines disrupted at activated Kiras. Science. 1993;260:85–88. doi: 10.1126/science.8465203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Diaz R, Lue J, Mathews J, Yoon A, Ahn D, Garcia-Espana A, Leonardi P, Vargas MP, Pellicer A. Inhibition of Ras oncogenic activity by Ras protooncogenes. Int J Cancer. 2005;113:241–248. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang Z, Wang Y, Vikis HG, Johnson L, Liu G, Li J, Anderson MW, Sills RC, Hong HL, Devereux TR, et al. Wildtype Kras2 can inhibit lung carcinogenesis in mice. Nat Genet. 2001;29:25–33. doi: 10.1038/ng721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chai H, Brown RE. Field effect in cancer-an update. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 2009;39:331–337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Slaughter DP, Southwick HW, Smejkal W. Field cancerization in oral stratified squamous epithelium; clinical implications of multicentric origin. Cancer. 1953;6:963–968. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(195309)6:5<963::aid-cncr2820060515>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baker CH, Kedar D, McCarty MF, Tsan R, Weber KL, Bucana CD, Fidler IJ. Blockade of epidermal growth factor receptor signaling on tumor cells and tumor-associated endothelial cells for therapy of human carcinomas. Am J Pathol. 2002;161:929–938. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64253-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hendrix A, Westbroek W, Bracke M, De Wever O. An Ex(o)citing Machinery for Invasive Tumor Growth. Cancer Res. 2010;70:9533–9537. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-3248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Piepkorn M, Underwood RA, Henneman C, Smith LT. Expression of amphiregulin is regulated in cultured human keratinocytes and in developing fetal skin. J Invest Dermatol. 1995;105:802–809. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12326567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thorne BA, Plowman GD. The heparin-binding domain of amphiregulin necessitates the precursor pro-region for growth factor secretion. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:1635–1646. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.3.1635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Halter SA, Dempsey P, Matsui Y, Stokes MK, Graves-Deal R, Hogan BL, Coffey RJ. Distinctive patterns of hyperplasia in transgenic mice with mouse mammary tumor virus transforming growth factor-alpha. Characterization of mammary gland and skin proliferations. Am J Pathol. 1992;140:1131–1146. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ju WD, Velu TJ, Vass WC, Papageorge AG, Lowy DR. Tumorigenic transformation of NIH 3T3 cells by the autocrine synthesis of transforming growth factor alpha. New Biol. 1991;3:380–388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McConnell RE, Higginbotham JN, Shifrin DA, Jr., Tabb DL, Coffey RJ, Tyska MJ. The enterocyte microvillus is a vesicle-generating organelle. J Cell Biol. 2009;185:1285–1298. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200902147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.