Summary

Infection by HIV starts when the virus attaches to a susceptible cell. For viral replication to continue, the viral envelope must fuse with a cellular membrane, thereby delivering the viral core to the cytoplasm, where the RNA genome is reverse-transcribed. The key players in this entry by fusion are the envelope glycoprotein, on the viral side, and CD4 and a co-receptor, CCR5 or CXCR4, on the cellular side. Here, the interplay of these molecules is reviewed from cell-biological, structural, mechanistic, and modeling-based perspectives. Hypotheses are evaluated regarding the cellular compartment for entry, the transfer of virus through direct cell-to-cell contact, the sequence of molecular events, and the number of molecules involved on each side of the virus-cell divide. An emerging theme is the heterogeneity among the entry mediators on both sides, a diversity that affects the efficacy of entry inhibitors, be they small-molecule ligands, peptides, or neutralizing antibodies. These insights inform rational strategies for therapy as well as vaccination.

Cellular entry of HIV and its inhibition

Like all other viruses, the human immunodeficiency virus, HIV, must enter a susceptible cell in order to replicate. Blocking its replication is of immense medical interest: every year 2-3 million people become HIV-infected. Transmission is usually sexual: virus in semen or mucosal fluids encounters susceptible cells to enter, such as T lymphocytes and dendritic cells, within the genital epithelia or through rifts in the mucosal lining. Once the virus has entered a cell, replication can progress to the production of progeny virus. If replication starts cascading from local lymphoid tissue to regional lymph nodes, and further to the gut-associated lymphoid tissue and blood, systemic infection of the host will ensue (Haase, 2010).

Specific entry inhibitors are sometimes used together with other drugs to curb viral loads in HIV-infected patients. Neutralizing antibodies also block entry and can prevent transmission, but no vaccine candidate has yet induced high levels of such antibodies capable of neutralizing multiple strains of the virus. Possible interim substitutes are entry inhibitors applied mucosally: they prevent infection in animal models and are considered for human use (Klasse et al., 2008). Entry is thus at the forefront of strategies to treat and prevent HIV infection.

At the cell-biological and bio-physical levels, knowledge is evolving of where, how, and with what number of participating molecules the virus enters. The realization that the molecular mediators are heterogeneous in many regards, both on the viral and the cellular side, is crucial to understanding HIV entry and how to thwart it.

The participants and the process

As an enveloped virus, HIV must fuse the phospholipid bilayer surrounding it with a host cell membrane in order to deliver the viral core and genome to the cytoplasmic compartment (Grove and Marsh, 2011)). The envelope glycoprotein (Env) of HIV mediates this entry by fusion. It is produced as a precursor, gp160, which is cleaved by a furin-like protease in the trans-Golgi network. This cleavage into an outer subunit, gp120, and a transmembrane moiety, gp41, is necessary but not sufficient to render Env fusogenic. After proteolysis, gp120 and gp41 remain coupled, but then as non-covalent hetero-dimers. Trimers of such hetero-dimers are incorporated when virus particles, or virions, assemble and bud from the infected cell in a process driven by the viral Gag protein. These trimers are meta-stable and require further stimuli to mediate entry.

When a virion encounters a cell, it can infect only if it finds the requisite receptors: gp120 has a high-affinity binding site for the T-lymphocyte receptor CD4 (Sattentau and Weiss, 1988). The binding of gp120 to CD4 triggers conformational changes in Env that enable interactions with a co-receptor, a member of the seven-transmembrane chemokine-receptor family, usually CCR5 (R5 virus) or CXCR4 (X4 virus) (Alkhatib et al., 1996). This interaction in turn elicits more drastic changes in Env, releasing the fusogenic potential of gp41 (Figure 1).

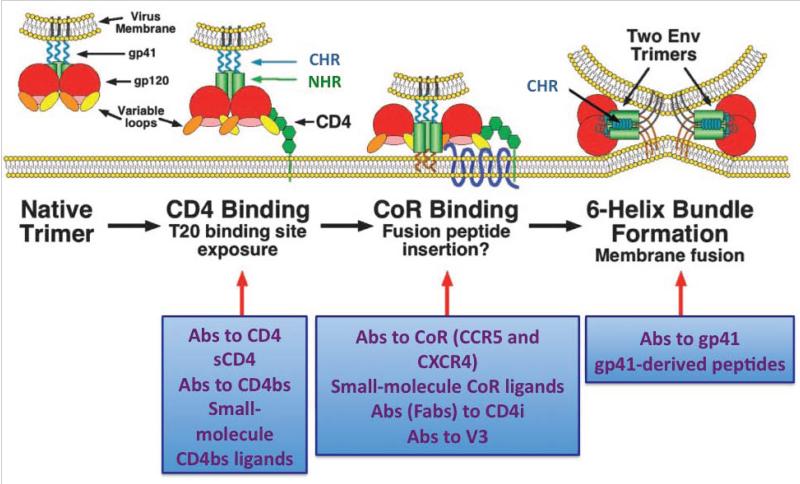

Figure 1. HIV enters susceptible cells through membrane fusion mediated by the viral Env protein.

Top. Env mediates fusion

A schematic of an Env trimer, anchored in the viral membrane, is shown in the first image to the left, and then a sequence of events is illustrated, from left to right, from receptor interactions to fusion of the viral envelope with the cell membrane. The second image of the trimer shows the binding of gp120 to the first domain of the CD4 receptor: NHR and CHR in gp41 become extended and the co-receptor-binding site is induced. In the third image, Env makes contact with a co-receptor, CCR5 or CXCR4. The bending of the hinge between domains 2 and 3 in CD4 and the interaction with the co-receptors pull the trimer to the target cell membrane. The co-receptor interaction also triggers the insertion of the gp41 “fusion peptide” (FP) into the cell membrane. Finally, in the fourth image, fusion has occurred, gp41 has refolded into a six-helix bundle, composed of the three copies of CHR slotting into the grooves of the trimer of NHRs. A number of principally different inhibitors of entry are listed in the boxes below the images of the steps they block. Amended and reproduced with permission from (Moore and Doms, 2003).

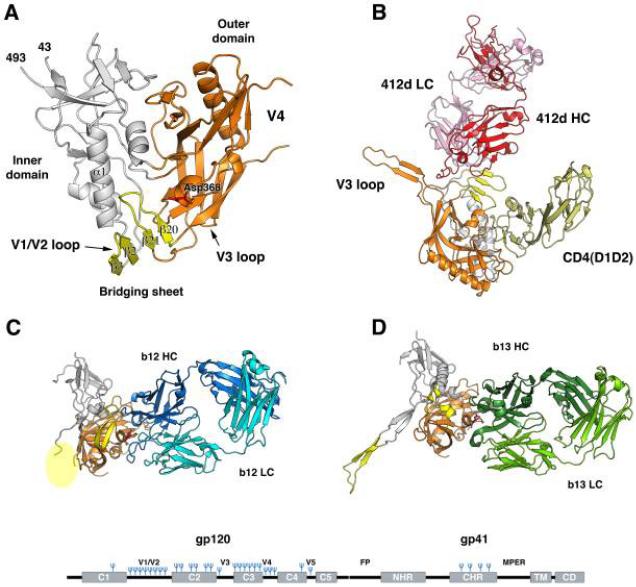

Bottom. The three-dimensional structure of gp120, the receptor-binding subunit of Env

Four different structures of gp120 are shown: gp120 consists of an inner domain (grey), an outer domain (orange), and a bridging sheet. (A) The tertiary structure of the core of a gp120 monomer was first obtained after several modifications: truncation of variable loops V1V2 and V3 as well as the N- and C-terminal segments, enzymatic trimming of glycans, and conformational stabilization by the binding of CD4 and a Fab to a CD4- induced epitope (these constituents of the complex are not shown). The bridging sheet is formed by the V1V2 stem and the hairpin of the β20-β21strands. Asp368 (red) contacts Arg59 in CD4. (B) Gp120 including V3 is complexed with CD4 (the D1D2 domains, pale yellow) and a Fab to a bridging-sheet epitope (412d light chain, LC, in pink, heavy chain, HC, in red). (C) Gp120 is bound by the neutralizing antibody b12 (HC in dark blue; LC in cyan), directed to the CD4-binding site. (D) gp120 is bound by the antibody b13 (HC in dark green; LC in light green); although b13, like b12, is directed to the CD4- binding site, it does not neutralize because its epitope is poorly antigenic on the trimeric form of Env, where the b12 epitope is well recognized. At the bottom of the figure is a schematic of the polypeptide chain of the Env precursor: the N-terminal subunit, gp120, contains five regions that are relatively conserved among viral strains (C1-C5). These form α helices and β strands in the folded protein. Gp120 is cleaved from gp41 at the C-terminal end of C5. Intercalated between the conserved regions of gp120 are variable regions, labeled V1V2-V5. In the more conserved gp41, the fusion peptide (FP), the N- and C-terminal helical regions (NHR and CHR), the membranee-proximal external region (MPER), the transmembrane segment (TM), and the cytoplasmic domain (CD) are marked. Glycans are shown as blue forks. Reproduced with permission from (Pejchal and Wilson, 2010); see references therein.

In addition to the specific receptors, miscellaneous cell-surface molecules provide ancillary attachment for the virus: heparan-sulfate moieties interact with positively charged side chains of Env; DC-SIGN and other lectins on dendritic cells anchor the virus via glycans on Env (Geijtenbeek et al., 2000); and cellular passenger proteins in the viral envelope contribute by attaching to their physiological ligands on the cells. For example, ICAM-1 on virions binds to LFA-1 on lymphocytes. Neutralizing antibodies prevent entry by interfering with specific receptor interactions or with later steps. Whether interference with CD4 binding blocks attachment of the virions to target cells depends on the prevalence of the ancillary attachment molecules (Klasse and Sattentau, 2002; Ugolini et al., 1997).

Env has evolved a panoply of defenses against neutralizing antibodies. Half the mass of gp120 consists of complex or high-mannose glycans forming a dense shield. Amino-acid changes in its hyper-variable regions, notably in V1V2 and V3, sometimes affecting glycosylation sites, continually effect escape from neutralization (Hartley et al., 2005; Pejchal and Wilson, 2010). The three-dimensional structure of monomeric gp120 illustrates how the conserved receptor-binding sites are largely secluded from antibody binding (Figure 1B). Gp120 has two domains, one oriented towards the center of the trimer, the other towards the periphery. The highly glycosylated outer domain is a double β barrel; the inner domain has a 3-helix 4-strand bundle and a 7-strand β-sandwich. A sub-domain connects the two domains. CD4 inserts itself between the domains, inducing a bridging-sheet in the connecting sub-domain, near the base of V3.

The native structure of gp41 is unknown, but its functional motifs are well studied. The N-terminal 20 residues of gp41, often called the “fusion peptide” or FP (although it is C-terminally continuous with the rest of gp41), encompass a conserved motif of hydrophobic and glycine residues (Figure 1). C-terminal to the fusion peptide are two regions prone to helicize: the N-terminal and C-terminal heptad repeats (NHR and CHR). Between these is a disulfide-bridged loop, docking into gp120. The NHR transiently exposes neutralization epitopes during the entry process (Gustchina et al., 2010; Sabin et al., 2010). C-terminally of the CHR lies the membrane-proximal external region (MPER), also harboring neutralization epitopes. Both the MPER and the transmembrane domain that it borders on are crucial to fusion (Munoz-Barroso et al., 1999). Finally, the long cytoplasmic tail contains no less than ten potential trafficking signals; it modulates the conformation of external Env and its fusogenicity (Bhakta et al., 2011).

The cytoplasmic tail juxtaposes the matrix protein, which forms a shell underneath the envelope after cleavage of the Gag precursor. Virions only become fusion-competent as they mature by cleaving and rearranging Gag. This control over fusion by Gag is relieved by a deletion of the C-terminal 28 of the 152 tail residues (Jiang and Aiken, 2006). A point mutation in the matrix protein even disrupts the non-covalent association of gp120 with gp41, thereby preventing viral fusion (Davis et al., 2006). This effect also depends on the intact tail, further underlining the intricacy of the chain of gp41 interactions from virus interior to exterior.

Our best knowledge of the structure of the entire Env trimers on virions comes from cryo-electron-tomographic comparisons of unliganded Env trimers with those bound by the Fab b12 (directed to the CD4-binding site) or by a soluble form of CD4 and the Fab 17b (directed to the CD4-induced co-receptor-binding site). The partially known structures of the constituents of these Env trimers and complexes were superimposed on three-dimensional models of the whole trimers (Liu et al., 2008). The unliganded and b12-complexed Env-trimer conformations were similar. Contrasting with these, the complex including CD4 and 17b differed dramatically: the trimer was more open, the average mass displaced upwards; the stalk at the center of the complex was more exposed, possibly representing an extended gp41; the V3 region was reoriented from the edge of the apex to point directly towards a presumptive target-cell surface; the V1V2 region and the CD4-binding site were rotated outwards. In addition, the hinge between domains 2 and 3 in CD4 was bent. Corresponding quaternary changes in trimers docking onto membrane-anchored CD4 would draw the viral envelope towards the cell membrane.

The CD4-induced projection of V3 towards the target-cell surface fits well with structural knowledge of gp120-coreceptor interactions. The N terminus of CCR5 reaches to the bridging sheet and the base of V3, its tip juxtaposing the second extracellular loop of the co-receptor (Huang et al., 2005). Thereby the gp120 cap loosens its hold on the meta-stable gp41 subunit, triggering further fusogenic alterations (Melikyan, 2008; Platt et al., 2007). Small-molecule co-receptor ligands block this triggering. Viral resistance to such inhibitors thus develops in the context of taut mechanistic linkages. Resistance is achieved by shifting the balance between Env interactions from the second extracellular loop of CCR5 to its N terminus. Mutations mainly in V3, but also in the fusion peptide of gp41, confer such resistance (Anastassopoulou et al., 2009; Berro et al., 2009). These dominant modes of viral escape illustrate the intricate functional connections in the Env-receptor complexes that culminate in fusion.

Fusion as an end result is thermodynamically favored, but the barriers are high. Like other fusogenic viral proteins, gp41 acts in two decisive steps, cast and fold: first, the fusion peptide darts out, its insertion into the target-cell membrane possibly disrupting the lamellar organization of the phospholipids. Second, gp41 provides the requisite energy for fusion by ultimately refolding into a six-helix bundle.

The casting out of the fusion peptide creates a pre-bundle intermediate that is sensitive to NHR- and CHR-peptide inhibitors, and during which the disulfide loop in gp41 weakens its contacts with gp120, while the MPER epitopes lose exposure. The transitions of the pre-bundle intermediate are functionally consequential, first inducing hemifusion and then opening small pores. These pores are reversible and their expansion might require the participation of several Env trimer-receptor complexes, specifically involving the MPER region (Munoz-Barroso et al., 1999) (Figure 2A). A circular agglomeration of Env-receptor complexes could be spatially favored by the ultimate refolding (Melikyan, 2008).

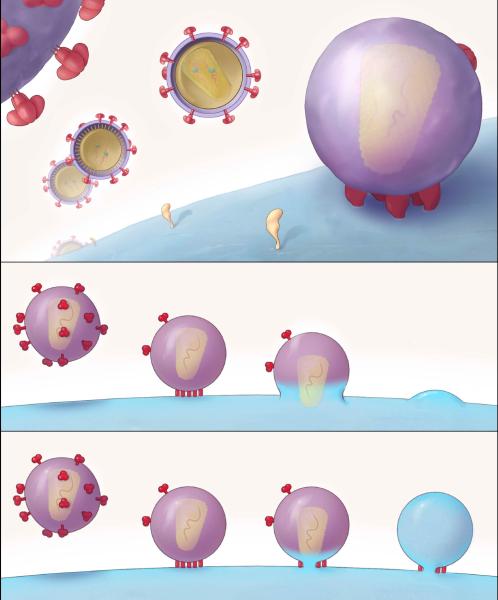

Figure 2.

A. (Top) HIV virus particles (virions) are shown at different distances (they are all around 120 nm in diameter). The intersection in the middle shows the phospholipid bilayer of the viral envelope, surrounding a conical core. The viral envelope is studded with mushroom-like Env-protein trimers; the trimeric quaternary structure of Env is better discernable on the enlarged part of a virion in the upper left-hand corner. A cell surface is represented to the lower right, with some sparse receptors in yellow.

(Middle) The virion docks onto the target cell and an entry claw forms by the lateral gathering of five Env trimers and a complement of receptors into a patch. When the juxtaposed areas of envelope and cell membrane have fused, the core passes into the cytoplasm. Fusion was thought to occur at the cell surface, with the plasma membrane, but cumulative evidence points to the endosome as the site of productive entry.

(Bottom) A small fusion pore opens the communication between virion interior and cytoplasm. Expansion of the pore possibly involves more of the neighboring trimer-receptor rods in the entry claw. Reproduced from (Sougrat et al., 2007).

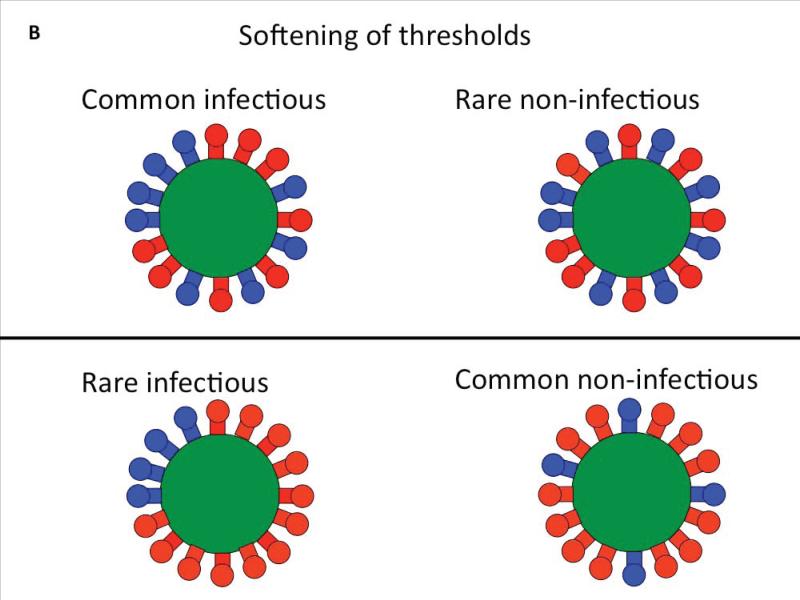

B. A virion is postulated to be infectious only if it has more Env trimers than a certain threshold value. Heterogeneous distribution of Env trimers over the virion surface can soften such thresholds. Here the virions have 16 trimers each. Some are functional (blue; eight in top row; four in bottom row). If four contiguous trimers are needed for infection, most virions in the top row will be infectious, but few in the bottom row. In some studies virion infectivity has been postulated to be all-or-nothing, but the cartoon illustrates the possibility that a virion with more than a bare minimum number of trimers could have a greater propensity to infect than one that is just on the cusp of the threshold. Furthermore, different constellations of a minimum number of trimers might confer different propensities to infect. Whereas some virions are completely non-infectious, the infectious ones might not be equal but could display a spectrum of infectious propensity.

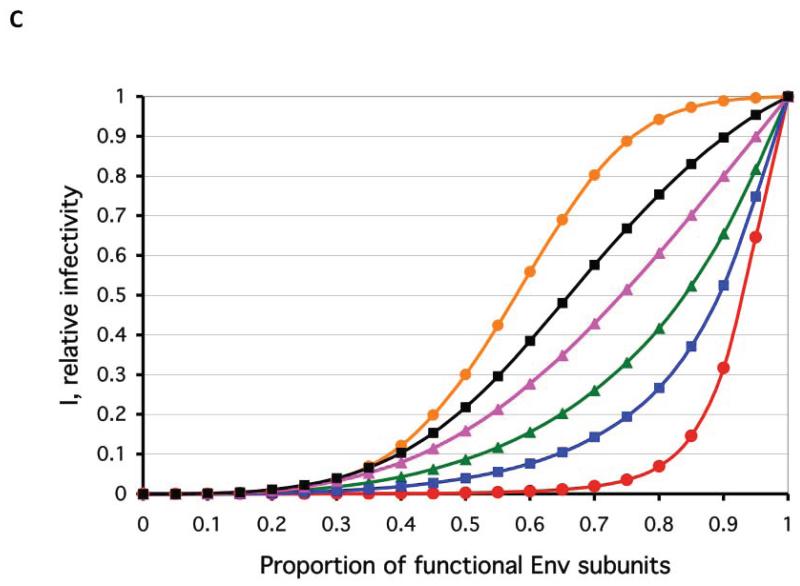

C. The number of Env trimers per virion required for viral entry has been investigated by mixing defective and functional Env and by mathematically modeling the infectivity of the resulting virus. The relative infectivity (y axis) of such phenotypically mixed virus is a function of the proportion of functional Env protomers (x axis). A total of 9 potentially functional trimers per virion are postulated. The different curves represent degrees of blurring of the thresholds of absolute minimum numbers of functional trimers required for infectivity (as in B): high thresholds, around a minimum of 8 trimers, are shown in hard (red circles), intermediate (blue squares), and soft (green triangles) forms; low thresholds, around a minimum of 2 trimers, are also shown in hard (orange circles), intermediate (black squares), and soft (magenta triangles) forms. All the functions for these curves incorporate the premise that only trimers with three active protomers are fusogenic: thus at the level of the trimer the minimum or threshold for fusogenicity is three functional protomers. In general, threshold height at the trimer and virion levels compensate each other, so that theoretically distinct models become empirically indistinguishable. B and C are reproduced from (Klasse, 2007), where mathematical equations are given.

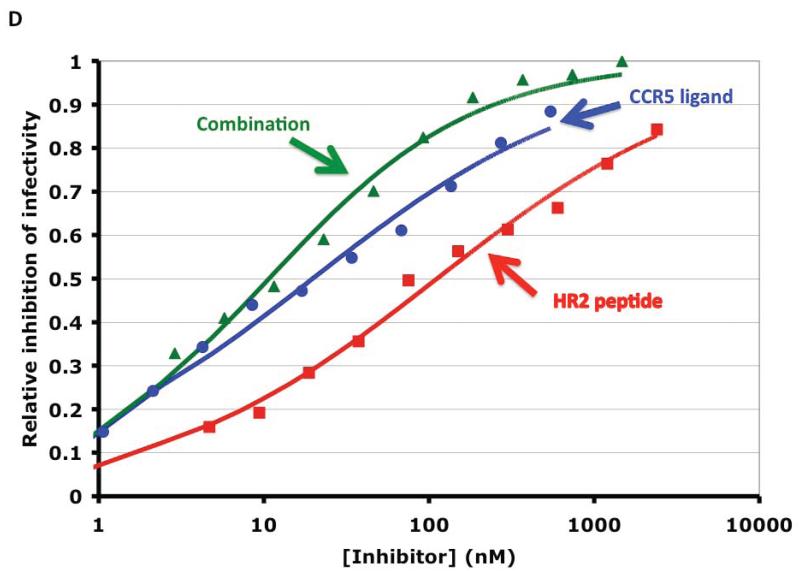

D. Inhibition of CCR5-dependent HIV infection by a small-molecule CCR5 ligand (Vicriviroc, blue circles), a gp41-HR2-derived peptide (T-20, red squares), and their combination (green triangles). The synergy index calculated by non-linear regression was on average 0.22 (<1 indicates synergy) and the fold increase in apparent cooperativity or slope coefficient was 1.5. The synergy observed could be attributed partly to a prolongation of the HR2-peptide-sensitive intermediate by the CCR5 ligand, partly to heterogeneity in the target molecules on both sides. Reproduced from (Ketas et al., 2012).

From which compartment does the virus enter cells?

Unlike, for example, influenza virus, HIV does not depend on the low pH of the endosome to trigger its fusion machinery (Maddon et al., 1988; McClure et al., 1988). Furthermore, the receptors and co-receptors that instead elicit fusion are present on the cell surface. This raises the question whether HIV enters the cell there. A clear answer requires a semantic note: entry is here defined as passage of the viral core into the cytoplasm; this is called productive entry if progeny virus results. When endocytosis of an enveloped virus does not lead to fusion with a vesicular membrane, i.e. not to entry, it can result in lysosomal degradation of the virus; or else in recirculation of intact virus to the surface, or as a special case thereof, transcytosis: vesicular traversal of an epithelial monolayer by the virion. These latter fates are not the focus here. They are only relevant in so far as they pertain to the main questions: Does productive entry result from, or even require, endocytosis, and if so of what type?

For quite some time the cell surface was considered the obligate, or at least preferential, site of entry. But the evidence was ambiguous. Electron micrographs of virions fusing at the cell surface might not represent complete fusion, let alone productive entry, by infectious virus (Grewe et al., 1990; Stein et al., 1987). Blocking the constitutive endocytosis of CD4 by deletions in its cytoplasmic tail does not reduce infection (Maddon et al., 1988; Pelchen-Matthews et al., 1995), but might still allow endocytosis of virions capping such mutated receptors. Furthermore, early studies attributed monocyte infection to receptor-mediated endocytosis (Pauza and Price, 1988), and also showed HIV virions fusing from within endosomes (Grewe et al., 1990). As a complication, endocytosis of HIV is largely conducive to lysosomal degradation and therefore unproductive (Marechal et al., 1998; Schaeffer et al., 2004). Recently, however, precise methods of tracking individual virions, of distinguishing lipid and content mixing, and of interfering with the function of components of the endocytic machinery (small-molecule inhibitors of dynamin and of the terminal domain of clathrin) have given evidence that, in HeLa- and T-cell lines, complete fusion and productive entry depend on endocytosis (Dale et al., 2011; de la Vega et al., 2011; Miyauchi et al., 2009; von Kleist et al., 2011). Previously, the clathrin-mediated pathway was strongly implicated in productive entry into HeLa cells: interfering with caveolin (not expressed in lymphocytes) had no effect on infection, whereas the clathrin-specific dominant-negative form of Eps15 (epidermal-growth-factor-receptor substrate 15, involved in adaptor-protein-2 recruitment and coated-pit assembly) reduced infection by up to 95% (Daecke et al., 2005). Moreover, HIV enters macrophages through a different type of endocytosis: macropinocytosis or a dynamin-dependent variant thereof (Carter et al., 2011; Marechal et al., 2001). Collectively, current evidence thus supports HIV entry by different endocytic routes depending on the cell type. Future research might explain in molecular terms why the endosomal sub-localization of the entry complex permits progress from hemifusion to pore formation, whereas at the cell surface the process is arrested at hemifusion.

Are cells or virions the mediators of transmission?

An HIV-infected cell can establish a contact zone with a target cell: such virological synapses are the subject of intense research; but that topic concerns viral egress, as much as it does entry, and has been reviewed elsewhere (Feldmann and Schwartz, 2010; Piguet and Sattentau, 2004). In general, transmission of infection across the virological synapse involves viral budding and Env-mediated virion fusion. It remains unknown whether mucosal transmission is mediated preferentially by virions or cell-to-cell transfer. Nor is the role of dendritic cells in that process ascertained. Still, R5- and X4-HIV-infected dendritic cells form immunological synapses with T cells. And these structures can be usurped by the virus for efficient transfer to the T cells, the concomitant activation of which specifically favors their infection by R5 rather than X4 virus (Yamamoto et al., 2009). The R5 selectivity agrees with the dominance of that tropism among transmitted strains of the virus, a pattern that could, however, have multiple causes (Grivel et al., 2011).

The virological synapse also highlights the interplay between Gag and the cytoplasmic tail of Env: when free virions infect, their cores might have matured long before target cells are encountered. In contrast, the shorter time lapse from viral budding to fusion via the synapse makes maturation and internalization overlap. Nevertheless, fusion must await Gag cleavage: inhibitors of the viral protease block fusion after internalization (Dale et al., 2011).

Synaptic transfer raises questions about the accessibility of neutralization epitopes and binding sites for entry inhibitors (Dale et al., 2011). So does the endocytic entry route itself, which apparently is integral to infection via the synapse. In spite of the potential barriers, similar potencies of entry blockers have been observed for free-virion- and cell-to-cell-mediated infection (Martin et al., 2010), with the intriguing exception of ligands for the CD4-binding site and some other epitopes on gp120 (Abela et al., 2012). Hence the synapse must be permeable to inhibitors, and sufficient fluid-phase concentrations of ligands for transiently exposed sites must prevail as endocytic vesicles pinch off. But what could cause the relative resistance against inhibitors of CD4 binding, specifically when they act on the viral side? The explanation, with potential implications for viral escape from neutralization and for vaccine development, will require improved quantitative and qualitative understanding of entry in the different modes of transmission.

How many protein molecules participate?

Stoichiometry deals with the relative quantities of chemical reactants or constituents; molecularity denotes the absolute number of participants in a chemical reaction. The corresponding variables would feature in a full account of the mechanics of HIV entry: How many protomeric subunits in the trimer are necessary for its function? How many Env trimers contribute, and how many CD4 and co-receptor molecules do they contact? Is there an absolute minimum as well as a higher optimum number? These questions are not as arcane as they may sound: the answers could determine the outcome of entry inhibition in therapy or through vaccine-induced antibodies (Klasse and Moore, 1996).

The minimal requirements of numbers of protein units required may be regarded as thresholds, one at the functional level of the trimer and one at that of the virion. To determine such threshold values, a set of studies used phenotypic mixing of functional and non-functional Env. Infectivity data for varied proportions of these forms of Env were interpreted by mathematical modeling. The conclusion was that a single trimer is sufficient to mediate the entry of one virion, but that all three protomers must be active for the trimer to function (Yang et al., 2005). With other mutants, defective in receptor binding or fusion, it was concluded that two of the protomers per trimer confer function to the trimer but that, again, a single trimer confers infectivity (Yang et al., 2006). Further mathematical modeling of mixed-phenotype data from the same and other studies has made different assumptions and given different conclusions: 5-8 trimers per virion (~60% of total) have been estimated to participate in effective entry. That estimate is uncertain, because the total number of functional trimers per virion is unknown, and the effects at the level of the trimer and of the virion are compensatory, (Klasse, 2007; Magnus and Regoes, 2012; Magnus et al., 2009).

Several factors can soften the appearance of thresholds for quantitative Env requirements in entry: the number of trimers per virion and their distribution on the virion surface vary, making the population of virions heterogeneous; and whereas each infection of a cell is a quantal, all-or-nothing event, the infectivity of a virion could span a wide spectrum of propensities. Furthermore, each mathematical model could have different virological interpretations. For example, the model for virions that only have one trimer, which is exactly what they need for infectivity, is mathematically identical to a multi-trimer model in which every trimer contributes equally and incrementally to the infectivity. There might be both a minimum required for strong infectivity and incremental contributions by spare trimers. The resulting thresholds will then soften and fit the infectivity data better. But it will also be harder to differentiate a high from a low threshold empirically (Figure 2C). Similar principles apply at the level of the individual trimer: the strict model for a requirement of two functional protomers per trimer, which has been fitted with vastly different assumptions at the virion level (Magnus and Regoes, 2012; Yang et al., 2006), means that a third functional protomer adds nothing to the function of the trimer. A perhaps more realistic model allows both a minimum requirement of two protomers and an increment in function by the third (Klasse, 2007).

On other theoretical grounds, invoking the requirements for expanding the fusion pore (Melikyan, 2008), and the energy to compensate for the entropically unfavorable receptor binding (Kwong et al., 2002), it has also been argued that several Env trimers would be required to mediate entry.

Some of these theoretical interpretations are corroborated by electron tomography showing the architectures of Env trimers on virions interacting with CD4-positive target cells: the contact regions regularly displayed five to seven rods. These entry claws formed only on permissive target cells and were blocked by entry inhibitors (Figure 2A) (Sougrat et al., 2007). Possibly, virions clawing thus to the cell surface get internalized and later fuse with endosomal membranes.

Molecular heterogeneity on both sides?

On the viral side, diversity occurs on many levels, from the number and distribution of trimers on the virion to mutants, post-translational modifications, and conformational variants of the individual Env molecules. Much evidence, including the difficulties of crystallizing monomeric gp120 and Env trimers, points to an unusual conformational flexibility of Env (Kwong et al., 2002; Pejchal and Wilson, 2010). Unliganded trimers are not conformationally identical (Liu et al., 2008). Env on virions is partly defective and not even exclusively trimeric (Leaman et al., 2010; Moore et al., 2006; Poignard et al., 2003) (Figure 2B). More relevant to entry, the functional, trimeric subset of Env can be diverse too: because of the high error rate of the reverse transcriptase, even Env produced by one cell infected by one virion will be genetically diverse; some mutations will affect glycosylation sites; irregular glycan addition and processing will add to this heterogeneity.

On the cellular side, CD4 molecules are less heterogeneous than the co-receptors. Dualtropic (R5X4) virus can use either CCR5 or CXCR4 and possibly a mixture in an entry complex. CCR5 has four tyrosine residues in its N-terminal extracellular segment, and they can be sulfated in different permutations with varying enhancing effects on entry (Farzan et al., 1999; Seibert et al., 2002). CXCR4 has shown heterogeneity in the degree of binding of antibodies (Baribaud et al., 2001). Different antibodies to CCR5 also have distinct binding maxima on target cell lines, and they differentially inhibit wild-type and mutant viruses that have escaped the action of small-molecule ligands for CCR5 (Berro et al., 2011; Lee et al., 1999). The best explanation is that different subpopulations of co-receptors on the cell surface have distinct antigenicities (capacity to be recognized by antibody) and interact differently with Env. Indeed, small-molecule ligands appear to have distinct affinities for subpopulations of CCR5 that are used differentially by wild-type and escape mutants of the virus (Anastassopoulou et al., 2009).

Hence wide-ranging data support heterogeneity among the key molecules on both the viral and the cellular side. The upshot could be an even greater combined heterogeneity in the viral-cellular interface. Such extensive heterogeneity could explain the low slope coefficients of entry-inhibition curves and how combinations among small-molecule inhibitors and antibodies, with targets on either side, give rise to apparent positive cooperativity and synergy (Ketas et al., 2012) (Figure 2D). Averaging the inhibition curves for heterogeneous targets of one inhibitor reduces the slope coefficient and thus simulates negative cooperativity. Conversely, when different inhibitors are combined, their respective inhibitory strengths and weaknesses compensate each other, and the net slope rises: the higher the inhibition level the greater the synergy appears to be. Thus linked synergistic and cooperative phenomena could arise from target heterogeneity even in the absence of the classical mechanism of mutually enhanced binding. These effects provide a rationale for aiming at multiple specificities, not only in therapy with entry inhibitors, but also in vaccination with Env: combinations of entry inhibitors increase potency as well as efficacy and might pre-empt viral escape.

Conclusion

The viral mediator of HIV entry, the Env protein, is an elusive target that has evolved strong defenses against immune attack by antibodies. Yet its conserved interaction with cellular receptors leaves some vulnerability at the level of the functional trimer. At other levels there might be further obstacles to intervention: HIV entry is pH-independent, but much new evidence favors an obligatory role for endocytosis to allow for complete fusion and delivery of the viral core and genome to the cytoplasm of the target cell. The number of molecules involved in entry will affect the sensitivity to inhibition: the lower the minimum in proportion to the total number of Env trimers and receptors the greater will be the required occupancies by inhibitors, including neutralizing antibodies. Heterogeneity among the viral and cellular proteins that mediate entry complicates the interpretations of dose-effect curves and emphasizes the need for combining inhibitors.

Acknowledgment

The author’s work in this area is supported by NIH grants AI36082, AI41420, and by the IAVI Neutralizing Antibody Consortium. Comments on the manuscript by Mark Marsh, Gregory Melikyan, and John P. Moore, and permission from Ian Wilson, Robert Pejchal, Sriram Subramaniam, and journals to reproduce figures, are greatly appreciated.

References

- Abela IA, Berlinger L, Schanz M, Reynell L, Gunthard HF, Rusert P, Trkola A. Cell-Cell Transmission Enables HIV-1 to Evade Inhibition by Potent CD4bs Directed Antibodies. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002634. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alkhatib G, Combadiere C, Broder CC, Feng Y, Kennedy PE, Murphy PM, Berger EA. CC CKR5: a RANTES, MIP-1alpha, MIP-1beta receptor as a fusion cofactor for macrophage-tropic HIV-1. Science. 1996;272:1955–1958. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5270.1955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anastassopoulou CG, Ketas TJ, Klasse PJ, Moore JP. Resistance to CCR5 inhibitors caused by sequence changes in the fusion peptide of HIV-1 gp41. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:5318–5323. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811713106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baribaud F, Edwards TG, Sharron M, Brelot A, Heveker N, Price K, Mortari F, Alizon M, Tsang M, Doms RW. Antigenically distinct conformations of CXCR4. J Virol. 2001;75:8957–8967. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.19.8957-8967.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berro R, Klasse PJ, Lascano D, Flegler A, Nagashima KA, Sanders RW, Sakmar TP, Hope TJ, Moore JP. Multiple CCR5 conformations on the cell surface are used differentially by human immunodeficiency viruses resistant or sensitive to CCR5 inhibitors. J Virol. 2011;85:8227–8240. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00767-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berro R, Sanders RW, Lu M, Klasse PJ, Moore JP. Two HIV-1 variants resistant to small molecule CCR5 inhibitors differ in how they use CCR5 for entry. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:E1000548. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhakta SJ, Shang L, Prince JL, Claiborne DT, Hunter E. Mutagenesis of tyrosine and di-leucine motifs in the HIV-1 envelope cytoplasmic domain results in a loss of Env-mediated fusion and infectivity. Retrovirology. 2011;8:37. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-8-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter GC, Bernstone L, Baskaran D, James W. HIV-1 infects macrophages by exploiting an endocytic route dependent on dynamin, Rac1 and Pak1. Virology. 2011;409:234–250. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daecke J, Fackler OT, Dittmar MT, Krausslich HG. Involvement of clathrin-mediated endocytosis in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 entry. J Virol. 2005;79:1581–1594. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.3.1581-1594.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale BM, McNerney GP, Thompson DL, Hubner W, de Los Reyes K, Chuang FY, Huser T, Chen BK. Cell-to-cell transfer of HIV-1 via virological synapses leads to endosomal virion maturation that activates viral membrane fusion. Cell Host Microbe. 2011;10:551–562. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2011.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis MR, Jiang J, Zhou J, Freed EO, Aiken C. A mutation in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag protein destabilizes the interaction of the envelope protein subunits gp120 and gp41. J Virol. 2006;80:2405–2417. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.5.2405-2417.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Vega M, Marin M, Kondo N, Miyauchi K, Kim Y, Epand RF, Epand RM, Melikyan GB. Inhibition of HIV-1 endocytosis allows lipid mixing at the plasma membrane, but not complete fusion. Retrovirology. 2011;8:99. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-8-99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farzan M, Mirzabekov T, Kolchinsky P, Wyatt R, Cayabyab M, Gerard NP, Gerard C, Sodroski J, Choe H. Tyrosine sulfation of the amino terminus of CCR5 facilitates HIV-1 entry. Cell. 1999;96:667–676. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80577-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldmann J, Schwartz O. HIV-1 Virological Synapse: Live Imaging of Transmission. Viruses. 2010;2:1666–1680. doi: 10.3390/v2081666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geijtenbeek TB, Torensma R, van Vliet SJ, van Duijnhoven GC, Adema GJ, van Kooyk Y, Figdor CG. Identification of DC-SIGN, a novel dendritic cell-specific ICAM-3 receptor that supports primary immune responses. Cell. 2000;100:575–585. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80693-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grewe C, Beck A, Gelderblom HR. HIV: early virus-cell interactions. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1990;3:965–974. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grivel JC, Shattock RJ, Margolis LB. Selective transmission of R5 HIV-1 variants: where is the gatekeeper? J Transl Med. 2011;9(Suppl 1):S6. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-9-S1-S6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grove J, Marsh M. The cell biology of receptor-mediated virus entry. J Cell Biol. 2011;195:1071–1082. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201108131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustchina E, Li M, Louis JM, Anderson DE, Lloyd J, Frisch C, Bewley CA, Gustchina A, Wlodawer A, Clore GM. Structural basis of HIV-1 neutralization by affinity matured Fabs directed against the internal trimeric coiled-coil of gp41. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1001182. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haase AT. Targeting early infection to prevent HIV-1 mucosal transmission. Nature. 2010;464:217–223. doi: 10.1038/nature08757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartley O, Klasse PJ, Sattentau QJ, Moore JP. V3: HIV’s switch-hitter. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2005;21:171–189. doi: 10.1089/aid.2005.21.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang CC, Tang M, Zhang MY, Majeed S, Montabana E, Stanfield RL, Dimitrov DS, Korber B, Sodroski J, Wilson IA, et al. Structure of a V3-containing HIV-1 gp120 core. Science. 2005;310:1025–1028. doi: 10.1126/science.1118398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang J, Aiken C. Maturation of the viral core enhances the fusion of HIV-1 particles with primary human T cells and monocyte-derived macrophages. Virology. 2006;346:460–468. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ketas TJ, Holuigue S, Matthews K, Moore JP, Klasse PJ. Env-glycoprotein heterogeneity as a source of apparent synergy and enhanced cooperativity in inhibition of HIV-1 infection by neutralizing antibodies and entry inhibitors. Virology. 2012;422:22–36. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2011.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klasse PJ. Modeling how many envelope glycoprotein trimers per virion participate in human immunodeficiency virus infectivity and its neutralization by antibody. Virology. 2007;369:245–262. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2007.06.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klasse PJ, Moore JP. Quantitative model of antibody- and soluble CD4-mediated neutralization of primary isolates and T-cell line-adapted strains of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 1996;70:3668–3677. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.6.3668-3677.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klasse PJ, Sattentau QJ. Occupancy and mechanism in antibody-mediated neutralization of animal viruses. J Gen Virol. 2002;83:2091–2108. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-83-9-2091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klasse PJ, Shattock R, Moore JP. Antiretroviral drug-based microbicides to prevent HIV-1 sexual transmission. Annu Rev Med. 2008;59:455–471. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.59.061206.112737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwong PD, Doyle ML, Casper DJ, Cicala C, Leavitt SA, Majeed S, Steenbeke TD, Venturi M, Chaiken I, Fung M, et al. HIV-1 evades antibody-mediated neutralization through conformational masking of receptor-binding sites. Nature. 2002;420:678–682. doi: 10.1038/nature01188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leaman DP, Kinkead H, Zwick MB. In-solution virus capture assay helps deconstruct heterogeneous antibody recognition of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 2010;84:3382–3395. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02363-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee B, Sharron M, Blanpain C, Doranz BJ, Vakili J, Setoh P, Berg E, Liu G, Guy HR, Durell SR, et al. Epitope mapping of CCR5 reveals multiple conformational states and distinct but overlapping structures involved in chemokine and coreceptor function. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:9617–9626. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.14.9617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Bartesaghi A, Borgnia MJ, Sapiro G, Subramaniam S. Molecular architecture of native HIV-1 gp120 trimers. Nature. 2008;455:109–113. doi: 10.1038/nature07159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maddon PJ, McDougal JS, Clapham PR, Dalgleish AG, Jamal S, Weiss RA, Axel R. HIV infection does not require endocytosis of its receptor, CD4. Cell. 1988;54:865–874. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(88)91241-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnus C, Regoes RR. Analysis of the subunit stoichiometries in viral entry. PLoS One. 2012;7:e33441. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnus C, Rusert P, Bonhoeffer S, Trkola A, Regoes RR. Estimating the stoichiometry of human immunodeficiency virus entry. J Virol. 2009;83:1523–1531. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01764-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marechal V, Clavel F, Heard JM, Schwartz O. Cytosolic Gag p24 as an index of productive entry of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 1998;72:2208–2212. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.3.2208-2212.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marechal V, Prevost MC, Petit C, Perret E, Heard JM, Schwartz O. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 entry into macrophages mediated by macropinocytosis. J Virol. 2001;75:11166–11177. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.22.11166-11177.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin N, Welsch S, Jolly C, Briggs JA, Vaux D, Sattentau QJ. Virological synapse-mediated spread of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 between T cells is sensitive to entry inhibition. J Virol. 2010;84:3516–3527. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02651-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClure MO, Marsh M, Weiss RA. Human immunodeficiency virus infection of CD4-bearing cells occurs by a pH-independent mechanism. EMBO J. 1988;7:513–518. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb02839.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melikyan GB. Common principles and intermediates of viral protein-mediated fusion: the HIV-1 paradigm. Retrovirology. 2008;5:111. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-5-111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyauchi K, Kim Y, Latinovic O, Morozov V, Melikyan GB. HIV enters cells via endocytosis and dynamin-dependent fusion with endosomes. Cell. 2009;137:433–444. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore JP, Doms RW. The entry of entry inhibitors: a fusion of science and medicine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:10598–10602. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1932511100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore PL, Crooks ET, Porter L, Zhu P, Cayanan CS, Grise H, Corcoran P, Zwick MB, Franti M, Morris L, et al. Nature of nonfunctional envelope proteins on the surface of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 2006;80:2515–2528. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.5.2515-2528.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munoz-Barroso I, Salzwedel K, Hunter E, Blumenthal R. Role of the membrane-proximal domain in the initial stages of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope glycoprotein-mediated membrane fusion. J Virol. 1999;73:6089–6092. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.7.6089-6092.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauza CD, Price TM. Human immunodeficiency virus infection of T cells and monocytes proceeds via receptor-mediated endocytosis. J Cell Biol. 1988;107:959–968. doi: 10.1083/jcb.107.3.959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pejchal R, Wilson IA. Structure-based vaccine design in HIV: blind men and the elephant? Curr Pharm Des. 2010;16:3744–3753. doi: 10.2174/138161210794079173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelchen-Matthews A, Clapham P, Marsh M. Role of CD4 endocytosis in human immunodeficiency virus infection. J Virol. 1995;69:8164–8168. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.12.8164-8168.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piguet V, Sattentau Q. Dangerous liaisons at the virological synapse. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:605–610. doi: 10.1172/JCI22812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platt EJ, Durnin JP, Shinde U, Kabat D. An allosteric rheostat in HIV-1 gp120 reduces CCR5 stoichiometry required for membrane fusion and overcomes diverse entry limitations. J Mol Biol. 2007;374:64–79. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poignard P, Moulard M, Golez E, Vivona V, Franti M, Venturini S, Wang M, Parren PW, Burton DR. Heterogeneity of envelope molecules expressed on primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 particles as probed by the binding of neutralizing and nonneutralizing antibodies. J Virol. 2003;77:353–365. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.1.353-365.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabin C, Corti D, Buzon V, Seaman MS, Lutje Hulsik D, Hinz A, Vanzetta F, Agatic G, Silacci C, Mainetti L, et al. Crystal structure and size-dependent neutralization properties of HK20, a human monoclonal antibody binding to the highly conserved heptad repeat 1 of gp41. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1001195. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sattentau QJ, Weiss RA. The CD4 antigen: physiological ligand and HIV receptor. Cell. 1988;52:631–633. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90397-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaeffer E, Soros VB, Greene WC. Compensatory link between fusion and endocytosis of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in human CD4 T lymphocytes. J Virol. 2004;78:1375–1383. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.3.1375-1383.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seibert C, Cadene M, Sanfiz A, Chait BT, Sakmar TP. Tyrosine sulfation of CCR5 N-terminal peptide by tyrosylprotein sulfotransferases 1 and 2 follows a discrete pattern and temporal sequence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:11031–11036. doi: 10.1073/pnas.172380899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sougrat R, Bartesaghi A, Lifson JD, Bennett AE, Bess JW, Zabransky DJ, Subramaniam S. Electron tomography of the contact between T cells and SIV/HIV-1: implications for viral entry. PLoS Pathog. 2007;3:e63. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein BS, Gowda SD, Lifson JD, Penhallow RC, Bensch KG, Engleman EG. pH-independent HIV entry into CD4-positive T cells via virus envelope fusion to the plasma membrane. Cell. 1987;49:659–668. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90542-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ugolini S, Mondor I, Parren PW, Burton DR, Tilley SA, Klasse PJ, Sattentau QJ. Inhibition of virus attachment to CD4+ target cells is a major mechanism of T cell line-adapted HIV-1 neutralization. J Exp Med. 1997;186:1287–1298. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.8.1287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Kleist L, Stahlschmidt W, Bulut H, Gromova K, Puchkov D, Robertson MJ, MacGregor KA, Tomilin N, Pechstein A, Chau N, et al. Role of the clathrin terminal domain in regulating coated pit dynamics revealed by small molecule inhibition. Cell. 2011;146:471–484. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto T, Tsunetsugu-Yokota Y, Mitsuki YY, Mizukoshi F, Tsuchiya T, Terahara K, Inagaki Y, Yamamoto N, Kobayashi K, Inoue J. Selective transmission of R5 HIV-1 over X4 HIV-1 at the dendritic cell-T cell infectious synapse is determined by the T cell activation state. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000279. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X, Kurteva S, Ren X, Lee S, Sodroski J. Stoichiometry of envelope glycoprotein trimers in the entry of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 2005;79:12132–12147. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.19.12132-12147.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X, Kurteva S, Ren X, Lee S, Sodroski J. Subunit stoichiometry of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope glycoprotein trimers during virus entry into host cells. J Virol. 2006;80:4388–4395. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.9.4388-4395.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]