Abstract

Objectives

Describe the development and refinement of a scheme, Detail of Essential Elements and Participants in Shared Decision Making (DEEP-SDM), for coding Shared Decision Making (SDM) while reporting on the characteristics of decisions in a sample of patients with metastatic breast cancer.

Methods

The Evidence-Based Patient Choice instrument was modified to reflect Makoul and Clayman’s Integrative Model of SDM. Coding was conducted on video recordings of 20 women at the first visit with their medical oncologists after suspicion of disease progression. Noldus Observer XT v.8, a video coding software platform, was used for coding.

Results

The sample contained 80 decisions (range: 1-11), divided into 150 decision making segments. Most decisions were physician-led, although patients and physicians initiated similar numbers of decision-making conversations.

Conclusion

DEEP-SDM facilitates content analysis of encounters between women with metastatic breast cancer and their medical oncologists. Despite the fractured nature of decision making, it is possible to identify decision points and to code each of the Essential Elements of Shared Decision Making. Further work should include application of DEEP-SDM to non-cancer encounters. Practice Implications: A better understanding of how decisions unfold in the medical encounter can help inform the relationship of SDM to patient-reported outcomes.

1. Introduction

In recent years, shared decision making (SDM), has become an ideal for medical practice and patient involvement.1-9 In general, SDM embraces the idea that medical or health-related decisions should be made with the input of both healthcare providers and patients, particularly in cases with no clinically superior option.10-13 At root, SDM is based on the premise that patients should be involved to the extent that they wish, and their values and preferences are crucial to deciding the “right” course of action. While the concept of SDM has become more clearly defined14, the best way to measure SDM in actual clinical encounters remains uncertain.

A recent review of SDM research detailed existing instruments to measure both process and outcomes of shared decision making.15 Several measures of SDM use audio recordings, including OPTION16 and the Informed Decision Making coding system17,18. Other systems, such as the Decision Analysis System for Oncology19, utilize transcripts. There have been some efforts to compare systems to one another,20,21 although no single system has emerged as a “gold standard.”15 Standard coding of SDM would facilitate comparison and generalizability in evaluating the process of decision making as well as determining effective components of decision making for improving health-related outcomes.

The measures that have been published up to this time have numerous limitations. First, most of these systems focus solely on provider behavior, and do not integrate the patient’s activity into the coding scheme. This is problematic conceptually, as SDM requires some level of patient participation. That is, it is not sufficient to know only that certain topics have been mentioned by physicians. It is clearly possible to include both physician and patient discourse: In their 1995 article on health promotion in primary care, Makoul, Arntson & Schofield reported discussion captured on video – whether initiated by physicians or patients – of medication instructions, benefits, risks, and side-effects, as well as patient perspectives about the medication and ability to follow the treatment plan.22 As reported by Scholl et al.,15 only one system for measuring SDM (the dyadic version of OPTION) 23 codes for both patient and healthcare provider behavior.

Further, most coding systems do not distinguish between discussions of benefits and discussions of risks. Although benefits and risks can be seen as two sides of the same coin, it is important to distinguish how these potential effects are presented to patients. Third, decision making in actual conversations is messy and complicated. To this point, coding systems have not coded for the sequence of decision making events, the duration of decision discussions, or dealt with the interconnected nature of many decisions. For example, OPTION codes from the basis of an “index problem,” potentially losing rich information about the entirety of decision making in a visit. Additional limitations are inherent in systems that code from transcripts, including the loss of paralinguistic cues (e.g., tone and inflection), gestures, and the additional time, expense, and potential for error involved in the transcription process.24 Importantly, one of the major limitations of shared decision making coding schemes has been that, particularly in general internal medicine visits, some items (e.g., assessment of patient understanding,16-18 patient role in decision making)17,18 occur so rarely in the datasets used and have such low kappa values for inter-rater reliability, that it becomes difficult to accurately ascertain the ability of the coding scheme to evaluate such items.16-18,25

As an exploratory study with a small sample size, this research was not strictly hypothesis-driven. However, we did hope to improve upon other coding systems by: 1) capturing more granularity, such as separating out statements of benefits from statements of risk); 2) concentrating on the contribution of each participant, e.g., noting who initiated segments; and 3) describing the temporal features of decision making.

Accordingly, we chose to focus our data collection on visits in which patient-preference sensitive decisions were likely to occur. Building on previous conceptual work,14 and using the Evidence-Based Patient Choice Instrument 26 as a starting point, we developed a coding scheme (Detail of Essential Elements and Participants in Shared Decision Making (DEEP-SDM)), intended to capture the Essential Elements of Shared Decision Making and applied it to two types of cancer consultations: women with newly diagnosed non-metastatic breast cancer and women with a suspected progression of metastatic breast cancer. Although DEEP-SDM is not intended to be applicable solely to oncology, these contexts were chosen because women with early stage breast cancer may have a variety of decisions to make about treatment, while decisions for women with metastatic disease focus more on symptom management and quality-of-life. The aims of this manuscript are to describe the development and refinement of the coding scheme in both samples of cancer patients while reporting on the characteristics of the decisions in the sample of patients with metastatic breast cancer.

2. Methods

2.1. Data Collection and Subject Recruitment

Both samples of video recordings were the result of recruitment efforts at a single large multispecialty academic institution. In the case of the patients recorded at the time of their first surgical consultation (n=9), potential participants were identified by clinic staff prior to check-in and handed a flyer describing the study. If a patient was interested in participating, she would tell the receptionist, who would introduce a research assistant. The research assistant would conduct the informed consent process. For patients with metastatic breast cancer, potential participants were told about the study by their medical oncologist. If the patient agreed to the study, the medical oncologist would conduct the informed consent process.

2.2. Revision of Evidence-Based Patient Choice Instrument

The previously published Evidence-Based Patient Choice Instrument originally coded items relevant to each option for a decision. For the most part, we maintained that structure, while adding in some new components. In prior work we delineated “Essential Elements of Shared Decision Making,” 14 and wanted DEEP-SDM to accurately code for these elements. [Insert Table 1 about here] In addition, we felt it necessary to include a way to code nested or intertwined decisions. For example, when discussing lumpectomy with radiation compared to mastectomy for breast cancer patients, the risks of lumpectomy and the risks of radiation should be discussed, however, it is also important that the patient understand that these represent a combined treatment option. That is, she will not be offered lumpectomy without radiation. As such, for particular options or decisions, we added in an item related to discussion of specific relationships or procedures. Further, for each decision, we modified the scheme to include the rationale for the option as well as the definition of the option. Third, we added a previously described code of “degree of decision sharing,” which ranges from 1 (doctor alone) to 9 (patient alone) for each decision.14 Two coders independently applied this coding scheme to a sample of 9 video-recorded breast cancer visits using paper forms. Where there were discrepancies, the coders met, with a third researcher if necessary, to come to consensus and modify the codebook accordingly.

Table 1. Essential elements of shared decision making and their definitions.

| Definitions in coding scheme | |

|---|---|

| Rationale for option | Reference made to a rationale for treatment or a reason why the patient should pursue the discussed treatment option. |

| Definition of option | Physician provides a description of the treatment option or procedure |

| Process or procedure | The provider gives a description of the procedure by which this treatment option is delivered. |

| Risks/cons | Mention of possible risks, side-effects, or decreased quality of life associated with the discussed treatment option. |

| Benefits/pros | Discussion of or reference to possible benefits or increased quality of life associated with treatment option. |

| Patient self-efficacy | Reference to or mention of patient perceived self- efficacy or ability [to adhere to the decision], by either the provider or the patient. |

| Patient preferences and values | Provider mentions his or her own preferences/values briefly OR makes it clear that he or she would/would not consider this to be a good option. |

| Patient outcome expectations | Reference made to patient outcome expectations or concerns, by patient or provider |

| Patient understanding confirmed | Reference made to patient’s understanding, or it is clear that the patient’s understanding is sufficient based on her comments. |

| Plan for follow-up | Reference to a plan for follow-up regarding the discussed treatment option. Further information needed to reach a decision. May include making other decisions, waiting on the results of other tests, scheduling consultations with other providers, etc. |

In the next phase of the research, the paper coding scheme was converted to an electronic one for use with Noldus Observer XT (version 8). This software is designed for the coding of behavior directly from video. By using a computer-based coding system, we were able to more easily identify, quantify, and describe decision making segments. Such a system allows for coding of duration of decision making segments as well as sequence The second dataset used for testing the coding system consisted of 20 video recordings of women with metastatic breast cancer discussing treatment options with their medical oncologists (n=2) upon suspicion of disease progression. Because the types of decisions to be made differed from those for women with early-stage breast cancer, one research assistant (MMH) previewed a random sample of about half the videos. She modified and added details and clarifications to the codebook, changing examples within definitions to be more inclusive of the metastatic cancer context.

Next, two research assistants coded videos independently. As in the prior dataset, the coders came together in a consensus process in order to agree on a final version of the coding for each video. When discrepancies arose, they referred to the codebook again. Often, this was enough to result in agreement. If necessary, the principal investigator would meet with the coders to resolve discrepancies.

2.2. Additions to the coding scheme

Options were sorted into a priori categories of primary treatment, symptom management, and behavioral/quality of life. However, upon further review a new category of “theoretical future option” was included. This category was used when a hypothetical scenario that ended in various options was brought up. This category is reflective of the nature of metastatic cancer treatment, where even if a patient is in remission, the cancer is likely to come back, and thus patients want to know what the treatment plan would be in the future. Also, doctors and patients sometimes discuss the idea that someday the treatment will probably stop working, and what different options might be presented (such as continuing chemotherapy treatment or pursuing palliative care).

Research assistants also coded for who started discussions and who led discussions. A person was said to start a discussion if they were the first person to initiate the topic, even if the discussion was primarily led by another person. For example, a patient might ask about side effects of a medication, but the doctor may play the primary role in leading that discussion. The software allows one to select the initiator of an action or behavior, which allowed us to code for who started the discussion segment. At the end of every decision, a numeric value ranging from 1 to 9 was assigned to represent the “degree of decision sharing.” On this scale, 1 represents a physician-led decision, 5 is a shared decision, and 9 represents a patient-led decision. In the case where a decision was deferred, for example, if lab results were needed or further discussion was warranted, a degree of decision sharing was not coded.

3. Results

Based on patient self-report, both patient populations were primarily white (89% of those recorded at surgical consultation), although the sample of women with metastatic disease was somewhat more diverse, with 15 White, 3 black, 1 Asian, and 1 mixed race. Both samples were relatively young for breast cancer populations, with a mean age of 49 years for surgical patients and 51 years for those with metastatic disease. Of the 20 visits after progression of metastatic cancer was suspected, 6 had a support person (e.g., spouse, daughter) during the visit. Two physicians were in the study, Physician A saw 13 patients, and Physician B saw 7.

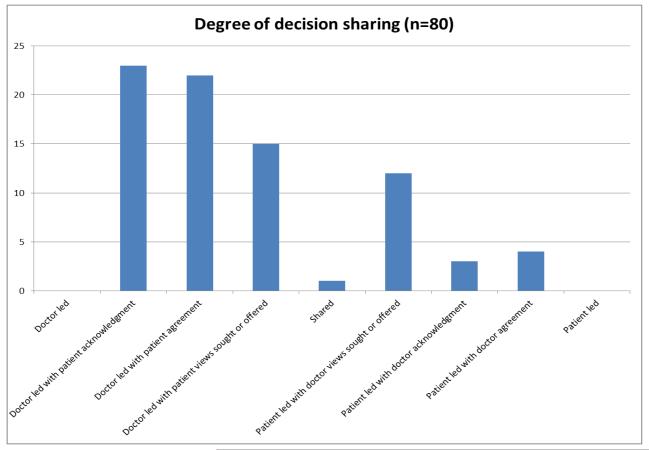

As the refined coding system emerged from the recordings that were coded using the Noldus software, we will report on these findings. Among the 20 visits, there were 80 decisions. While four were deferred past the visit, the degree of decision sharing ranged from “doctor led with patient acknowledgement” to “patient led with doctor acknowledgement.” [Insert Figure 1 about here] None of the decisions were completely doctor led or completely patient led. Most decisions (n=60) tended towards the doctor-led side of the spectrum, although 19 decisions were on the patient led side of the spectrum, and one was “shared.” The most common decision type was “doctor led with patient acknowledgement.”

Figure 1

Within these decisions, 171 options were discussed. The largest group was about primary treatment options (n=90), while 45 options were about symptom management. The remainder were about quality-of-life or behavioral options (n=28) or the previously described category of “theoretical future options” (n=8).

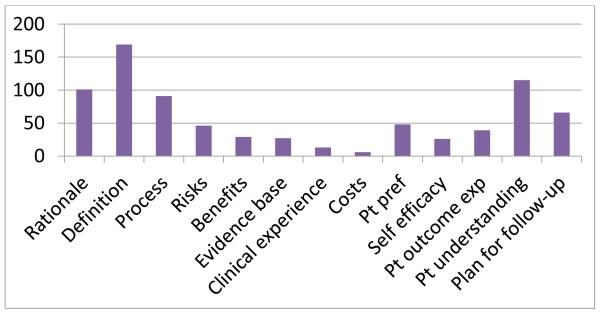

Of particular interest was whether the elements of shared decision making could be coded and their relative frequency. As seen in Figure 2, items related to explaining the options’ definition, process, or rationale were relatively frequent. Similar to other studies, risks and benefits are not commonly discussed. However, unlike many previous studies of SDM, patient understanding seems to appear more frequently.

Figure 2. Elements of SDM present (n=84 decisions, 171 options).

3.1. Anatomy of decisions

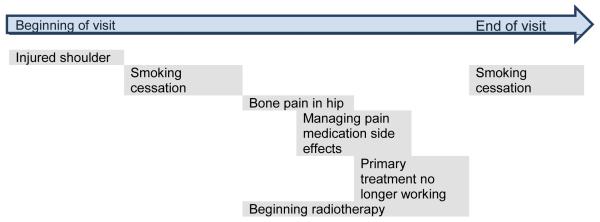

Decisions were often made in a non-linear manner. For example, it was not unusual for someone to initiate a discussion, for the topic to be covered for some short period of time, and then have the decision resumed later, after other subjects had been discussed. Thus, we coded conversation segments where particular decisions were discussed.

As the “anatomy of decisions” diagram illustrates, it is not uncommon for several options to be discussed over the course of a given visit. There were 4 decisions on average in the 20 visits in this sample (range: 1-11), composed of 158 decision making segments (mean=7.9 segments per visit, range 1-19). The amount of time spent in decision making ranged from 102 seconds to 1643 seconds (mean 603 seconds per visit).

Figure 3 shows a simplified example from the dataset. This patient was faced with decisions about her primary treatment, symptom management, and quality of life. Some topics have temporal overlap, while one, smoking cessation, is discussed and then revisited at the end. At the outset of the visit, the patient complains of pain from an injured shoulder. When the physician asks about other concerns, the patient expresses interest in smoking cessation and reports bone pain from the cancer. The doctor explains that the bone pain may be related to the shoulder, and that both could be treated with radiotherapy. Pain medication is discussed in order to enhance the patient’s quality-of-life, although she expresses concerns about side effects. Returning to the discussion of radiotherapy, the physician explains that the primary systemic treatment is no longer working, and that a different approach may be needed. After further discussion of potential systemic treatments, the conversation returns to smoking cessation.

Figure 3. Anatomy of a visit with multiple decisions.

3.2. Initiation and duration of decision making segments

The person who initiated the discussion was not always the person who made the decision. In fact, patients started discussion segments (74 times) slightly more often than physicians (67 times), yet doctors were more likely to hold more influence over decisions, as described above. Rarely did support persons (n=8 segments) or an additional clinician (n=1 segment) begin decision making segments.

3.3. Possible role of support partners

The limited data available suggest that support partners may have an important role in ensuring that the patient’s voice is heard in decisions that are patient preference sensitive. Of the 20 visits in this sample, 6 included a family member or other support person. There may be a trend toward greater discussion of patient preferences (6/6 compared to 8/14) and self-efficacy (5/6 compared to 7/14) in visits with a support person.

4. Discussion and Conclusion

4.1. Discussion

The aims of this manuscript were to describe the development and refinement of a new coding system using samples of cancer patients while reporting on the characteristics of the decisions in the sample of women with metastatic breast cancer. Through this process, we have demonstrated a coding system with great potential that ameliorates or eliminates problems associated with other coding schemes, while highlighting some of the conceptual difficulties with coding decisions in the patient-provider context.

DEEP-SDM advances the field by drawing from strong conceptual work that illustrates a consensus within the field of what items comprise shared decision making. We have shown that the Elements of Shared Decision Making, including discussion of patient self-efficacy, can be coded, and seem to occur more frequently in the case of metastatic breast cancer than similar items have been reported previously.17,18,27 This is not surprising, as many coding systems have been developed and applied in primary care rather than in cancer. However, even a small sample such as ours can have adequate numbers and types of decisions for coding if the context is chosen carefully, i.e., many patient preference sensitive decisions can be anticipated. Further, coding can include all parties to the conversation, whose contributions may be important and are often overlooked in studies of patient-provider communication and shared decision making.28,29

Four important pieces emerged from this project. First, we provide a detailed picture of decision making in actual clinical practice. Decisions are often fragmented and intertwined with one another. To clinicians, this may not seem surprising, yet in efforts to quantify and examine decision making, coding systems have not dealt with this reality. The medical encounter has long been divided into sections according to the physician’s goals, 30,31 generally following the pattern of question asking, physical examination, and finally, explanations of the physician’s diagnoses or plans. Although this structure is familiar to many, much of the decision making seems to happen in the physician’s head, with the “decision” appearing at the end. This structure explains the fractured nature of decision making in medical encounters detailed here.

Second, no coding of which we are aware has reported on the duration of decision making within a sample of visits. Due to the disconnected nature of decision making segments, it is not surprising that this has not been achieved earlier. However, it is vital that we understand not just what happens during decision making, but the depth of the discussion. This coding system advances the field by bringing an increased level of detail to analysis of SDM. As physicians in the United States and several other countries are under increasing time pressure, a better understanding of the details and time needed to achieve a shared decision making process is essential. Although these data comprise too small of a sample to make definitive statements about the length of time devoted to decision making, coders were able to readily distinguish segments with decision elements from those without.

Third, our coders found that single item “degree of decision sharing” was intuitive and required little discussion or clarification. Further research should examine the extent to which this item correlates with more detailed analysis. The item may prove useful when detailed coding cannot be conducted. For example, a more in-depth analysis would determine whether patients explicitly sought out doctors’ views in order to make their decision.

Finally, we have provided more evidence for the feasibility of including and characterizing the roles of family members or companions in the medical visit. Prior research has indicated that companions or support persons may play important roles in patient participation and in medical decision making.28,29,32-37 Given the frequency with which companions appear in medical settings, it is vital that researchers include their contributions to communication processes.

There are several limitations to this study. First, this was a single-site study at a large academic medical center. The types of decisions and types of patients seen cannot be construed as generalizable to all women with metastatic breast cancer. In addition, our system was developed through a process of consensus, and as such, reliability data cannot be derived or reported here. However, the coders reported little need to come to consensus on several items, including the beginning and ending of decision making segments as well as on the degree of decision sharing. We believe that due to the extensive process of discussion and resolution, the codebook is now detailed enough to allow for coding on larger datasets with appropriate reliability statistics. Strengths of the study include the use of two clinical samples for the development of the coding scheme, its grounding in an integrative model of SDM, and the detail allowing for the approached to be replicated in other contexts and by other researchers.

4.2. Conclusion

We recognize that not all decision making takes place in or relevant to a single medical encounter, as has been discussed by others previously.38,39 In this sample, however, fewer than 5% of decisions were deferred beyond the time of the medical visit. In addition, the limitations involved in capturing a piece of the decision making process does not negate the necessity of more completely understanding the medical context. Despite the fact that our study was completed in a cancer setting, this coding system could be applied to chronic disease decisions in many clinical situations. Studies that record patients’ medical visits longitudinally should be able to further expand upon our knowledge of decision making over time among the same participants.

4.3. Practice Implications

DEEP-SDM, which allows for in-depth analysis of the contributions of each participant, captures all decision making in an encounter, and reflects an integrative model of shared decision making, is poised to meaningfully inform the processes of decision making and the relationship of SDM to patient-reported outcomes.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Jennifer Webb for her help in data collection.

Funding: NIH R03CA123202, K12HD055884, The Arthur Vining Davis Foundations

Role of funding

Financial support for the data used in this project was provided by the National Institutes of Health (R03CA123202, PI: Clayman) and the Arthur Vining Davis Foundations (PI: Makoul). Dr. Clayman was supported, in part, during development of the coding scheme on a training grant (K12HD055884)

The sponsors had no role in the study design, or in the collection, analysis, interpretation of the data.

The funders also had no role in the writing or in the decision to submit for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Contributor Information

Gregory Makoul, Center for Innovation, Saint Francis Care, Hartford, CT, USA; Department of Medicine, University of Connecticut School of Medicine, Farmington, CT, USA.

Maya M. Harper, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Chicago, Chicago, USA

Danielle G. Koby, Hartford Hospital, Hartford, CT, USA

Adam R. Williams, Division of General Internal Medicine, Northwestern University, Chicago, USA

REFERENCES

- 1.Satterfield JM, Spring B, Brownson RC, Mullen EJ, Newhouse RP, Walker BB, et al. Toward a transdisciplinary model of evidence-based practice. Milbank Q. 2009;87(2):368–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2009.00561.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krumholz HM. Informed consent to promote patient-centered care. J Am Med Assoc. 2010;303(12):1190–1. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levetown M. Communicating with children and families: from everyday interactions to skill in conveying distressing information. Pediatrics. 2008;121(5):e1441–60. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Committee on Bioethics AAoP Informed consent, parental permission, and assent in pediatric practice. Pediatrics. 1995;95(2):314–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stacey D, Murray MA, Legare F, Sandy D, Menard P, O’Connor A. Decision coaching to support shared decision making: a framework, evidence, and implications for nursing practice, education, and policy. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2008;5(1):25–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-6787.2007.00108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guadagnoli E, Ward P. Patient participation in decision-making. Soc Sci Med. 1998;47(3):329–39. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00059-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Woolf SH. Shared decision-making: the case for letting patients decide which choice is best. J Fam Pract. 1997;45(3):205–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karlawish JH. Shared decision making in critical care: a clinical reality and an ethical necessity. Am J Crit Care. 1996;5(6):391–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coulter A. Assembling the evidence: patient-focused outcomes research. Health Libr.Rev. 1994;11(4):263–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2532.1994.1140263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elwyn G, Edwards A, Mowle S, Wensing M, Wilkinson C, Kinnersley P, et al. Measuring the involvement of patients in shared decision-making: a systematic review of instruments. Patient Educ Couns. 2001;43(1):5–22. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(00)00149-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elwyn G, Edwards A, Kinnersley P, Grol R. Shared decision making and the concept of equipoise: the competences of involving patients in healthcare choices. Br.J Gen.Pract. 2000;50(460):892–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T. Decision-making in the physician-patient encounter: revisiting the shared treatment decision-making model. Soc Sci Med. 1999;49(5):651–61. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00145-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Charles C, Whelan T, Gafni A. What do we mean by partnership in making decisions about treatment? Brit Med J. 1999;319(7212):780–2. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7212.780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Makoul G, Clayman ML. An integrative model of shared decision making in medical encounters. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;60(3):301–12. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2005.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scholl I, Koelewijn-van Loon M, Sepucha K, Elwyn G, Legare F, Harter M, et al. Measurement of shared decision making - a review of instruments. Z Evid Fortbild Qual Gesundhwes. 2011;105(4):313–24. doi: 10.1016/j.zefq.2011.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elwyn G, Edwards A, Wensing M, Hood K, Atwell C, Grol R. Shared decision making: developing the OPTION scale for measuring patient involvement. Quality and Safety in Health Care. 2003;12(2):93–9. doi: 10.1136/qhc.12.2.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Braddock CH, 3rd, Edwards KA, Hasenberg NM, Laidley TL, Levinson W. Informed decision making in outpatient practice: time to get back to basics. J Am Med Assoc. 1999;282(24):2313–20. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.24.2313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Braddock CH, III, Fihn SD, Levinson W, Jonsen AR, Pearlman RA. How doctors and patients discuss routine clinical decisions. Informed decision making in the outpatient setting. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12(6):339–45. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1997.00057.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Singh S, Butow P, Charles M, Tattersall MH. Shared decision making in oncology: assessing oncologist behaviour in consultations in which adjuvant therapy is considered after primary surgical treatment. Health Expect. 2010;13(3):244–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2009.00587.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Butow P, Juraskova I, Chang S, Lopez AL, Brown R, Bernhard J. Shared decision making coding systems: how do they compare in the oncology context? Patient Educ Couns. 2010;78(2):261–8. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brown RF, Butow PN, Juraskova I, Ribi K, Gerber D, Bernhard J, et al. Sharing decisions in breast cancer care: Development of the Decision Analysis System for Oncology (DAS-O) to identify shared decision making during treatment consultations. Health Expect. 2011;14(1):29–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2010.00613.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Makoul G, Arntson P, Schofield T. Health promotion in primary care: physician-patient communication and decision making about prescription medications. Soc Sci Med. 1995;41:1241–54. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(95)00061-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Melbourne E, Sinclair K, Durand MA, Legare F, Elwyn G. Developing a dyadic OPTION scale to measure perceptions of shared decision making. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;78(2):177–83. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clayman ML, Webb J, Zick A, Cameron KA, Rintamaki LS, Makoul G. Video review: an alternative to coding transcripts of focus groups. Communication Methods and Measures. 2009;3(4):216–22. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ling BS, Trauth JM, Fine MJ, Mor MK, Resnick A, Braddock CH, et al. Informed decision-making and colorectal cancer screening: is it occurring in primary care? Med Care. 2008;46(9 Suppl 1):S23–9. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31817dc496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ford S, Schofield T, Hope T. Observing decision-making in the general practice consultation: who makes which decisions? Health Expect. 2006;9(2):130–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2006.00382.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gattellari M, Voigt KJ, Butow PN, Tattersall MH. When the treatment goal is not cure: are cancer patients equipped to make informed decisions? J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(2):503–13. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.2.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wolff JL, Roter DL. Hidden in plain sight: medical visit companions as a resource for vulnerable older adults. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(13):1409–15. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.13.1409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wolff JL, Roter DL. Family presence in routine medical visits: a meta-analytical review. Soc Sci Med. 2011;72(6):823–31. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Makoul G. The SEGUE Framework for teaching and assessing communication skills. Patient Educ Couns. 2001;45(1):23–34. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(01)00136-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lichstein PR. The Medical Interview. In: Walker HK, Hall WD, Hurst JW, editors. Clinical Methods: The History, Physical, and Laboratory Examinations. 3rd edition. Butterworths; Boston: 1990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wolff JL, Boyd CM, Gitlin LN, Bruce ML, Roter DL. Going it together: persistence of older adults’ accompaniment to physician visits by a family companion. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(1):106–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03770.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wolff JL, Roter DL. Older Adults’ Mental Health Function and Patient-Centered Care: Does the Presence of a Family Companion Help or Hinder Communication? J Gen Intern Med. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1957-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wolff JL, Roter DL. Family caregivers, patients, and physicians. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(6):487. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1314-0. author reply 88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Clayman ML, Roter D, Wissow LS, Bandeen-Roche K. Autonomy-related behaviors of patient companions and their effect on decision-making activity in geriatric primary care visits. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60(7):1583–91. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ishikawa H, Hashimoto H, Roter DL, Yamazaki Y, Takayama T, Yano E. Patient contribution to the medical dialogue and perceived patient-centeredness. An observational study in Japanese geriatric consultations. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(10):906–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0200.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ishikawa H, Roter DL, Yamazaki Y, Takayama T. Physician-elderly patient-companion communication and roles of companions in Japanese geriatric encounters. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60(10):2307–20. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.08.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rapley T. Distributed decision making: the anatomy of decisions-in-action. Sociol Health Illn. 2008;30(3):429–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2007.01064.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Montori VM, Gafni A, Charles C. A shared treatment decision-making approach between patients with chronic conditions and their clinicians: the case of diabetes. Health Expect. 2006;9(1):25–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2006.00359.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]