Abstract

For many years after its discovery, hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) was viewed as a toxic molecule to human tissues; however, in light of recent findings, it is being recognized as an ubiquitous endogenous molecule of life as its biological role has been better elucidated. Indeed, increasing evidence suggests that H2O2 may act as a second messenger with a pro-survival role in several physiological processes. In addition, our group has recently demonstrated neuroprotective effects of H2O2 on in vitro and in vivo ischaemic models through a catalase (CAT) enzyme-mediated mechanism. Therefore, the present review summarizes experimental data supporting a neuroprotective potential of H2O2 in ischaemic stroke that has been principally achieved by means of pharmacological and genetic strategies that modify either the activity or the expression of the superoxide dismutase (SOD), glutathione peroxidase (GPx) and CAT enzymes, which are key regulators of H2O2 metabolism. It also critically discusses a translational impact concerning the role played by H2O2 in ischaemic stroke. Based on these data, we hope that further research will be done in order to better understand the mechanisms underlying H2O2 functions and to promote successful H2O2 signalling based therapy in ischaemic stroke.

Keywords: brain ischaemia, hydrogen peroxide, neuroprotection, catalase, electrophysiology

Nomenclature

The drug/molecular target nomenclature used in this review conforms to the British Journal of Pharmacology's Guide to Receptors and Channels (Alexander et al., 2011), where applicable.

Historical notes

The history of H2O2 began in 1818 when it was discovered by Thénard who named it eau oxygénée (Thénard, 1818). Since the mid-1800s, H2O2 has been marketed for a wide variety of uses, including non-polluting bleaching, oxidizing agent, disinfectant in food processing and even fuel for rockets. The presence of H2O2 in living systems was identified in 1856 (Schoenbein, 1856). However, it was only in 1894 that 100% pure H2O2 was first extracted from H2O by Wolffenstein through vacuum distillation (Wolffenstein, 1894). In 1888, the first medical use of H2O2 was described by Love as efficacious in treating numerous diseases, including scarlet fever, diphtheria, nasal catarrh, acute coryza, whooping cough, asthma hay fever and tonsillitis (Love, 1888). Similarly, Oliver and collaborators reported that intravenous injection of H2O2 was efficacious in treating influenza pneumonia in the epidemic following World War I (Oliver et al., 1920). Despite its beneficial effects, in the 1940s medical interest in further research on H2O2 was slowed down by the emerging development of new prescription medicines. In the early 1960s, Urschel, and later Finney and co-workers, conducted several studies on myocardial ischaemia demonstrating a rescue afforded by H2O2, thereby suggesting an important protective action of H2O2 against ischaemia-reperfusion (IR) injury (Finney et al., 1967; Urschel, 1967). Notably, Farr is generally considered to be the pioneer of ‘oxidative therapy’ by proposing intravenous infusion of H2O2 to treat a wide variety of diseases (Farr, 1988). Later, Willhelm promoted the therapeutic use of H2O2 to treat cancer, skin diseases, polio and bacteria-related mental illness. He defined H2O2 as ‘God's given immune system’ (Willhelm, 1989; Green, 1998). Another player in the H2O2 story was Grotz, who obtained pain relief by testing H2O2 on himself to treat his arthritis pain (Green, 1998).

Metabolism of H2O2

H2O2 is mainly generated as a by-product of aerobic metabolism in the mitochondria (Fridovich, 1995), where formation of the superoxide anion (·O2−) results from partial reduction of molecular oxygen (O2) in the electron transport chain. A smaller amount of ·O2− is also produced by enzymatic activities including NOS, xanthine oxidase, NADPH oxidase, dehydrogenases and peroxidases (Boveris and Chance, 1973; Rhee, 2006; Bao et al., 2009; Finkel, 2011). In addition, enzymes such as superoxide dismutase (SOD), in its three isoforms (cytosolic, extracellular Cu,Zn-SOD, and mitochondrial Mg-SOD), are also responsible for H2O2 production from ·O2− (Graham et al., 1978; Fridovich, 1995). The dismutation reaction catalyzed by SOD is as follows: 2·O2−+ 2H+→ H2O2+ O2. H2O2 is also generated as a direct by-product of MAO enzyme activity. In fact, the oxidative deamination reaction catalyzed by MAO requires O2 to degradate bioamines and produces H2O2, the corresponding aldehyde and ammonia according to the overall equation: R-CH2-NH2+ O2+ H2O → H2O2+ R-CHO + NH3, where R stands for alkyl group (Tipton, 1968; Tipton et al., 2004). Moreover, H2O2 generation can be the result of p66Shc enzyme activity (Giorgio et al., 2007). H2O2 is subsequently converted to H2O by scavenger enzymes such as cytosolic and mitochondrial glutathione peroxidase (GPx) which catalyzes the reaction: H2O2+ 2GSH → 2H2O + GSSG, or decomposed in peroxisomes to H2O and O2 by catalase (CAT) according to the equation: 2H2O2→ 2H2O + O2; the latter has been observed to be more effective than GPx in detoxifying neurons from H2O2 (Halliwell, 1999; Dringen et al., 2005). A smaller contribution to regulate H2O2 levels also comes from thioredoxins as well as peroxiredoxins (Prx) (Rhee, 2006; Mishina et al., 2011). H2O2 metabolism is highly dynamic: its intracellular concentration reflects the balance between processes of generation and removal (Halliwell, 1999). Actually, there are no certain measurements of either intracellular or extracellular H2O2 concentration. Many attempts to address this point have failed due to high cellular peroxidase-mediated depletion and technical limitations of H2O2-sensitive fluorescent dyes (Rice, 2011). However, in vivo microdialysis has been used to try to determine the extracellular production of H2O2 in the brain during IR. A fourfold rise in H2O2 from basal levels has been detected in dialysates from the rat anterior lateral striatum during reperfusion after 30 min of global forebrain ischaemia (approximately 100 µM at the peak during reperfusion phase) (Hyslop et al., 1995). Similarly, fluorometry of 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescin oxidation coupled with in vivo microdialysis have been applied in the gerbil hippocampal CA1 region in order to monitor changes in H2O2 concentration during IR. A marked and rapid increase in H2O2 level was recorded in the reperfusion phase, although to a lesser degree (range 1–3 µM), which continued to increase in dialysates until 30 min of reperfusion after transient ischaemia (5 min) (Lei et al., 1998). By means of mathematical models, upper limits (100 nM to 1 µM) have been recently estimated to be 10 to 100-fold lower than exogenously applied concentrations (Antunes and Cadenas, 2000), indicating a signalling action of H2O2 at 15–150 µM without any oxidative damage (Rice, 2011). Noteworthy, concentrations of H2O2 that can be reached in rat vascular smooth muscle cells exposed to IR insult are likely to be higher than 1 mM (Sundaresan et al., 1995). In spite of this, we are still searching for effective tools to detect the real concentration of H2O2 in both the intracellular and extracellular compartments of the brain. Of note, 1–3 mM H2O2 has been used for investigations of synaptic function and intracellular Ca2+ changes in the hippocampus (Pellmar, 1987; Nisticòet al., 2008; Gerich et al., 2009). These exogenous concentrations appear to have pathophysiological relevance. Conversely, the other important question related to the toxicity of relatively high extracellular concentrations of H2O2 has not really been solved yet. In fact, it has been reported that hippocampal neurons from primary culture tolerate 300 µM H2O2 for at least 30 min (Miller et al., 2005). However, it has to be considered that the concentration of H2O2 that reaches the intracellular milieu could be significantly lower than that superfused on tissue. Firstly, H2O2 transport might be limited by lipid membrane composition and diffusion rate (Antunes and Cadenas, 2000); secondly, it might be differently transported by aquaporins and other channels (Bienert et al., 2007). Therefore, the high concentrations used in in vitro experiments may not reflect the content reached in the intracellular compartment that could be markedly lower.

H2O2: a paradox player

Emerging role of H2O2 in the physiological control of cell functioning

H2O2 is often considered a toxic molecule for a wide range of living systems. It has also been reported to be implicated in severe pathological conditions such as cancer, ischaemia and neurodegenerative diseases (Halliwell and Gutteridge, 1999; Halliwell et al., 2000). However, robust evidence has led to re-evaluation of its role as an important regulatory signal in a variety of biological processes (Sundaresan et al., 1995; Sen and Packer, 1996; Rhee, 2006; Stone and Yang, 2006; D'Autréaux and Toledano, 2007; Miller et al., 2007; Veal et al., 2007; Gerich et al., 2009; Groeger et al., 2009; Rice, 2011), thus suggesting that the deleterious role of this oxidant has been overestimated. In particular, H2O2 can modulate synaptic transmission (Pellmar, 1987; Katsuki et al., 1997; Chen et al., 2001; Avshalumov et al., 2003; 2008) and plasticity in the rodent brain (Colton et al., 1989; Auerbach and Segal, 1997; Klann and Thiels, 1999; Kamsler and Segal, 2003). H2O2 is also implicated in intracellular Ca2+ signalling and organelle function modulation in rat hippocampus (Gerich et al., 2009). Additional evidence has indicated a dynamic modulation exerted by H2O2 in the nigrostriatal dopaminergic (DAergic) system. In fact, it inhibits substantia nigra DAergic neurons and striatal DA release by activating ATP-sensitive K+ channels (KATP) (Chen et al., 2001; Avshalumov et al., 2003; 2005; 2008). Of note, H2O2 may also act as an excitatory agent on non-DAergic neurons by inducing transient receptor potential (TRP) channel (subgroup melastatin type TRPM2) activation (Rice, 2011).

Mechanisms, targets and outcomes of H2O2 signalling: concentration as a determining factor

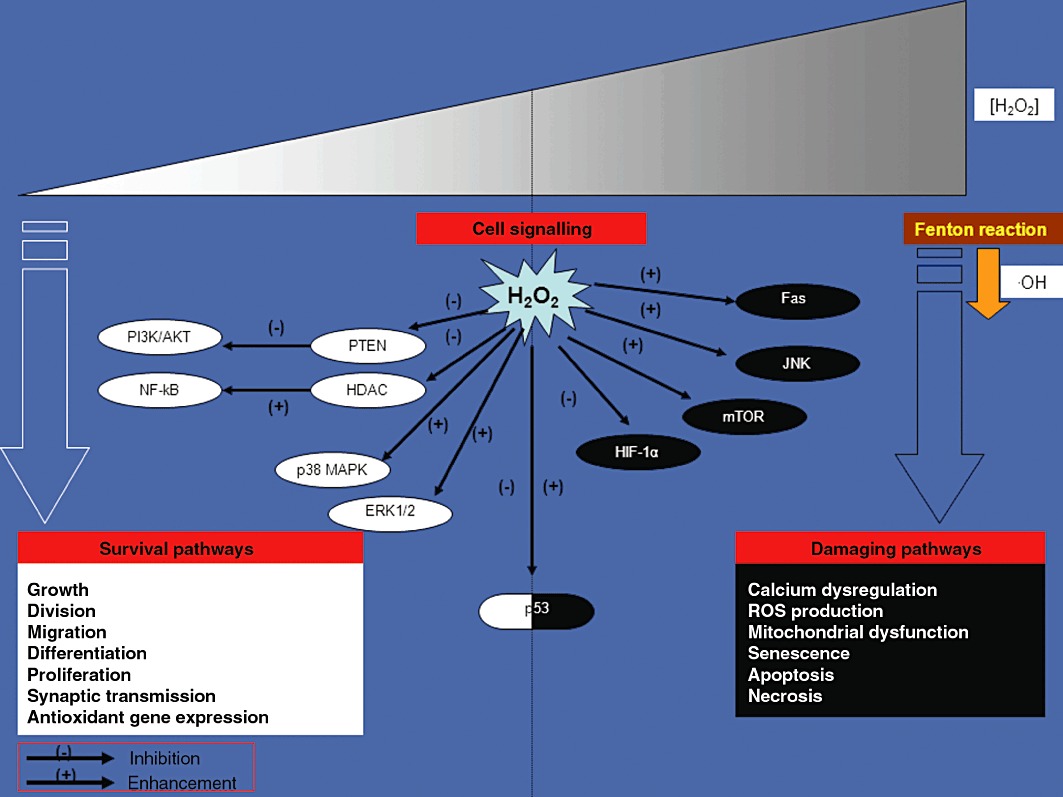

H2O2 is a chemical messenger able to spread locally in and out of the cell. It passes across cell membranes through specific aquaporin 3 channels or freely, like other diffusible messengers (such as NO, carbon monoxide and hydrogen sulphide) (Bienert et al., 2006; 2007; Miller et al., 2010). In chemical terms, H2O2 is poorly reactive and is more stable than other reactive oxygen species (ROS) because it is not itself a free radical. Therefore, it is able to survive long enough to act distant from its place of generation. It is widely accepted that low levels of H2O2 target sulfhydryl groups of protein cysteine residues by oxidizing them and consequently, affecting the activity of key signal transduction kinases and phosphatases, thus representing the ‘signalling face’ of H2O2 (Rhee et al., 2000; Giorgio et al., 2007) (Figure 1). In fact, H2O2 may affect cell-signalling survival pathways by reversibly inhibiting many proteins (i.e. phosphatases). Phosphatases are potent negative regulators of the survival pathways that transduce their signal through phosphorylation of key proteins (Groeger et al., 2009). For instance, H2O2 promotes the cell survival signalling cascade [e.g. phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/AKT] by inactivating Tyr and Ser/Thr phosphatases (e.g. PTEN, FAK, SHP2, CDC25, PTP1B) (Giorgio et al., 2007). On the other hand, H2O2 is also responsible for the activation of MAPKs (e.g. ERK1/2, p38 MAPK) and for the modulation of transcription factors involved in cellular response to stress stimuli such as hypoxia and oxidative stress (Giorgio et al., 2007; Oliveira-Marques et al., 2009). Under hypoxia, H2O2 may affect the activity of the transcription factor hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1α by inhibiting HIF-1α DNA-binding activity and accumulation (Groeger et al., 2009). The regulatory role played by H2O2 on the nuclear factor (NF)-κB pathway is still controversial: among the described actions, an important one is the increase of DNA-binding activity of NF-κB through the H2O2-induced inactivation of the enzyme histone deacetylase which is implicated in chromatin remodelling (Groeger et al., 2009; Oliveira-Marques et al., 2009). Recently, it has also been demonstrated that H2O2 is also implicated in several growth factor-triggered signals (Stone and Yang, 2006; Valko et al., 2007). Further evidence has shown that H2O2 stimulates the renal epithelial Na+ channel through a PI3K pathway, thus suggesting its involvement in systemic blood pressure homeostasis (Ma, 2011). Notably, cell damage, death (either by necrosis or apoptosis) and senescence appear to be induced only by high levels of H2O2 (Giorgio et al., 2007; Oliveira-Marques et al., 2009). H2O2 may induce apoptosis in neuronal cells by inhibiting the mammalian target of rapamycin signalling (Chen et al., 2010). In endothelial cells, an excess of H2O2 activates Fas and JNK pathways in apoptosis (Cai, 2005). H2O2 oxidizes, in a manner to cause cytotoxic damage to biological macromolecules (such as lipids, proteins and DNA), only if converted to the highly reactive hydroxyl radical (•OH) (Winterbourn, 2008; Oliveira-Marques et al., 2009). The latter is generated via Fenton reaction by H2O2 interaction with free transition metals (mostly reduced Fe2+ and Cu+ ions) (Halliwell, 1992; Cohen, 1994). In its dual role as an indispensable signal molecule and a potential threat for biological components, H2O2 plays the double-faced role of ‘Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde’ (Gough and Cotter, 2011). Indeed, a real H2O2 paradox exists: on one hand, in low amounts H2O2 has a physiological role in the homeostatic maintenance of normal cell functioning; on the other hand, high amounts of H2O2 can be harmful for cells (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The H2O2 paradox in the regulation of cell signalling transduction cascade. The H2O2 biological functions depend on the concentration of H2O2 within the cell. At low concentrations, H2O2 acts as a messenger in a great variety of biological processes contributing to cell survival. In high concentrations, H2O2 can cause deleterious effects, mainly via •OH-derived radicals, by inducing a severe oxidative stress and cell death. Accordingly, a crucial target of H2O2 double-faced action is represented by the tumour suppressor protein p53 which can be either activated by low levels of H2O2, thus triggering an antioxidant response (anti-apoptotic programme), or inhibited by high levels of H2O2 leading to programmed cell death (pro-apoptotic programme) respectively.

H2O2 sensing during ischaemic injury: implications for neuroprotection

In order to maintain H2O2 physiological signalling function, both intracellular and extracellular concentrations of H2O2 need to be constantly maintained at a level below toxicity threshold via an accurate and complex metabolic regulation (Halliwell, 1999; Góth, 2006). In mammalian cells, redox sensor function has been suggested for Prx-1, thiol peroxidases and thiolate-dependent phosphatases, which may affect H2O2 signalling fluxes (Stone and Yang, 2006; D'Autréaux and Toledano, 2007). More importantly, specific responses to H2O2-induced oxidative stress are regulated in eukaryotic cells by acetylation or deacetylation of transcription factors of the class O forkhead box family, which could lead to either cell death or a quiescent cellular state (Brunet et al., 2004; van der Horst et al., 2004). Moreover, low levels of H2O2 stimulate p53 tumour suppressor-mediated antioxidant response by activating antioxidant genes (e.g. GPx, SOD, sestrins), while high levels of it induce p53-dependent apoptosis (Veal et al., 2007). The peroxisome proliferator-activated receptorγ (PPARγ) coactivator1α (PGC1α) also establishes a crucial link between mitochondrial production of ROS and anti-ROS programmes by regulating H2O2-inducible antioxidant enzymes (SOD, CAT, GPx) (St-Pierre et al., 2006; D'Autréaux and Toledano, 2007). Strong evidence now suggests PPARγ agonists as new therapeutic targets for the treatment of IR injury (Giaginis et al., 2008; Kaundal and Sharma, 2010); similarly, PGC1α could be a candidate for drug action as well. Interestingly, a dramatic accumulation of ROS has been reported as an additional side effect of IR (Flamm et al., 1978; Traystman et al., 1991). Indeed, ROS, including H2O2, are considered prime mediators of neuronal injury. During an IR episode, the oxidative stress either could result from increased ROS production or decreased activity of cellular defence systems (White et al., 2000; Valko et al., 2007). On the other hand, with regard to the ischaemia, experimental evidence also suggests that H2O2 elimination by CAT may provide an alternative source for O2, causing neuroprotection in hypoxic conditions (Topper et al., 1996; Auerbach and Segal, 1997; Klann and Thiels, 1999).

Effects of H2O2 on rodent in vitro and in vivo models of brain ischaemia

Valid experimental approaches are required for the development of a successful therapy for ischaemic stroke. Although models of brain ischaemia have been the main source of a plethora of information on stroke, these models often fail to mimic the complex scenario of stroke as observed clinically. Such limitations should be carefully considered when designing experiments to ensure translation of preclinical data to the clinic (Lipsanen and Jolkkonen, 2011). In our studies, we chose three different widely accepted experimental models of brain ischaemia: hypoxia and oxygen/glucose deprivation (OGD) as in vitro brain ischaemia models, and middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAo) as in vivo brain ischaemia model (Lipton, 1999). In hypoxia and OGD in vitro models, ischaemic stroke was mimicked by applying oxygen-deprived and oxygen/glucose-deprived artificial cerebral spinal fluid (ACSF) media, respectively, over a brain slice and gassing it with nitrogen (95% N2 to 5% CO2). At the end of the insult, the slice was again perfused with normal oxygenated (95% O2 to 5% CO2) ACSF medium. Both models allowed us to rapidly screen bath-applied compounds by determining their effect as well as their mechanism of action against the acute damage during eletrophysiological recording. Among the in vivo models currently used in stroke research, the transient focal ischaemia model (whole animal) represented by MCAo has been extensively used (Durukan and Tatlisumak, 2009). MCAo requires microsurgery to perform the filamentous intraluminal occlusion of the middle cerebral artery. This technique presents several advantages: it models focal infarction in a large vascular territory of the brain, where it is possible to distinguish core and penumbra regions; it is relatively less invasive because it does not require craniotomy; and it allows investigations after reperfusion.

Substantia nigra

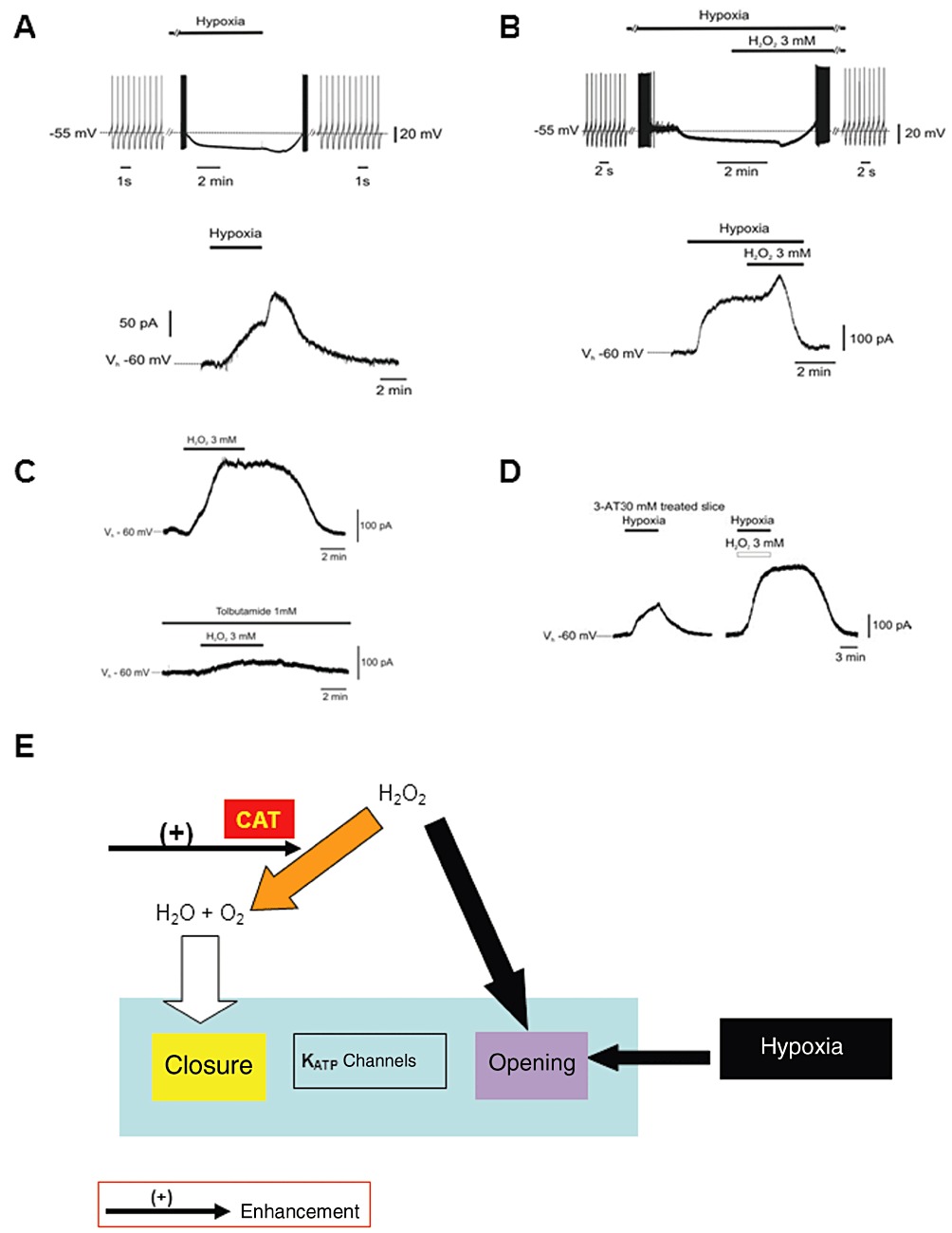

DAergic neurons of the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNc) are highly sensitive to metabolic stress. Very likely, as a safety mechanism to preserve energy consumption, these neurons typically respond to energy deprivation with membrane hyperpolarization, mainly through opening of KATP channels (Mercuri et al., 1994). After a prolonged hypoxia, this early hyperpolarization is followed by a profound and irreversible depolarization, due to opening of cationic conductance and failure of Na+/K+-ATPase pump (Mercuri et al., 1994; Lees and Leong, 1995). Moreover, previous observations have shown that H2O2 may act as a supplementary source of O2 in an isolated neonatal rat spinal cord preparation in vitro (Walton and Fulton, 1983) and a recovery of the synaptic function by H2O2 during hypoxic insult in rat hippocampal slices (Fowler, 1997). In the past years, we have used both electrophysiological and morphological techniques to investigate a possible protective role of H2O2 in DAergic neurons of the rat SNc exposed to hypoxic insult (Geracitano et al., 2005). Notably, H2O2 reversed membrane hyperpolarization and blocked spontaneous firing associated with oxygen-deprivation in DAergic neurons (Figure 2A,B). In contrast, in normoxic conditions, H2O2 (3 mM) blocked the spontaneous activity of the DAergic cells by inducing a KATP channels-dependent outward current that was sensitive to tolbutamide (1 mM) (a non-selective blocker of KATP channels) (Figure 2C). Of note, H2O2 decreased the hypoxia-mediated outward current in a concentration-dependent manner. Conversely, H2O2 did not counteract membrane hyperpolarization associated with hypoglycaemia. The superfusion of H2O2 (3 mM) during prolonged hypoxia (40 min) rescued most of the DAergic neurons from irreversible firing inhibition. Noteworthy, in the presence of 3-amino-1,2,4-triazole (3-AT, 30 mM), a specific inhibitor of CAT activity (Appleman et al., 1956; Margoliash and Novogrodsky, 1958), H2O2 was unable to decrease hypoxia-mediated outward current and thus restore the spontaneous firing rate (Figure 2D). The protective effects of H2O2 have been confirmed by inhibition of the hypoxia-induced release of cytochrome c, a well-known early indicator of apoptotic pathway activation (Fujimura et al., 2000; Sims and Anderson, 2002). These findings suggest a protective action of H2O2 in hypoxic DAergic neurons by serving as a supplementary source of O2, through its degradation by CAT and thus, interfering with KATP channels opening consequent to O2 deprivation (Figure 2E). On the other hand, under normoxic conditions, H2O2 (3 mM) induced by itself a tolbutamide-sensitive outward current in DAergic neurons. This outward response is due to the opening of KATP channels by a direct action of H2O2 on the channels (Avshalumov et al., 2005) (Figure 2E).

Figure 2.

Electrophysiological effects of H2O2 on SNc DAergic neurons. (A) Hypoxia caused firing discharge inhibition in current-clamp sharp electrode intracellular recordings (n= 11) (upper trace), and an outward current followed by a transient post-hypoxic outward current in voltage-clamp (Vholding=−60 mV) intracellular recordings (n= 8) (lower trace). (B) During hypoxia, after H2O2 (3 mM) perfusion, a transient hyperpolarization followed by complete firing recovery was observed (n= 6) (upper trace); the hypoxia-induced outward current was reverted by H2O2 (n= 6) (lower trace). (C) In normoxia, H2O2 (3 mM) induced a reversible outward current (n= 4) (upper trace); the KATP channel antagonist tolbutamide (1 mM) inhibited such current (lower trace). (D) Hypoxia induced outward current in the presence of CAT inhibitor 3-AT (30 mM); in the same neuron, such current is increased, not prevented in the presence of H2O2 (n= 8) in whole-cell patch-clamp voltage-clamp recordings (P < 0.01). Data in the graphs are expressed as means ± SEM. Bars indicate the exposure time to compounds and OGD [A–D modified from Geracitano et al. (2005); copyright J Physiol, used with permission]. (E) Hypothesized mechanism of neuroprotection afforded by H2O2 against hypoxic insult in SNc DAergic neurons. In normoxic conditions, H2O2, causes direct KATP channel opening (we believe that this is a generic cellular defensive response to insults). Also, hypoxia induces KATP channel opening in DAergic cells. However, H2O2 exerts neuroprotection by serving as an alternative source of O2 through the enhancement of its degradation via the CAT enzyme-mediated pathway. Thus, it counteracts the KATP channels opening.

Hippocampus

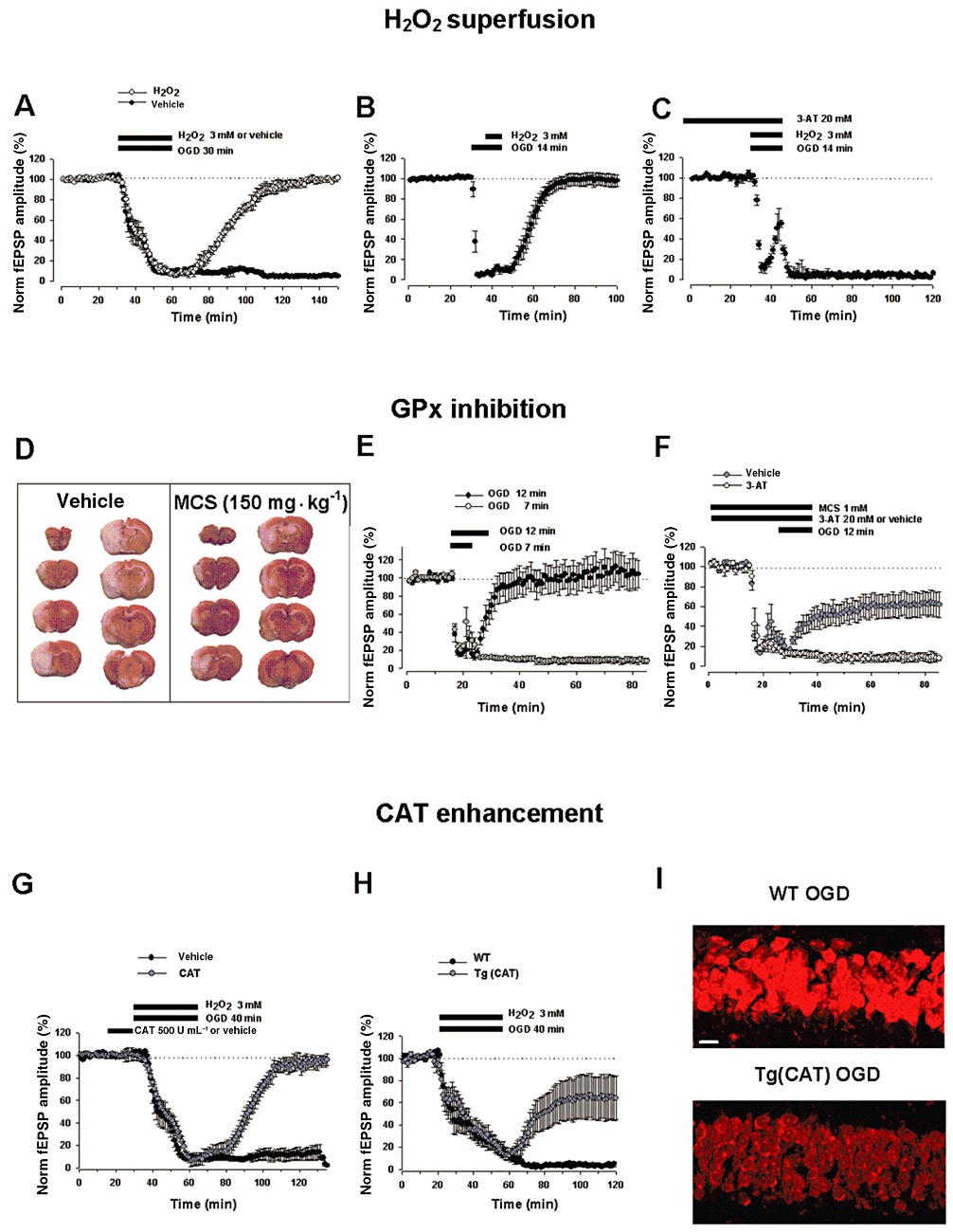

The CA1 hippocampal pyramidal neurons are known to be very vulnerable to IR insult (Kirino, 1982; Pulsinelli et al., 1982; Smith et al., 1984). Recently, we have evaluated the neuroprotective role of exogenous H2O2 and of the modification in its endogenous levels by the pharmacological modulation of H2O2 producing (Cu,Zn-SOD) and degrading enzymes (CAT and GPx) against in vitro OGD damage in hippocampal slices. Similar to what has been observed in a previous report (Fowler, 1997), we found that the irreversible depression of fEPSPs caused by in vitro OGD was abolished when slices were treated with H2O2 (3 mM, 30 min) during OGD exposure (30 min) in CA1 region (Nisticòet al., 2008) (Figure 3A). Importantly, the neuroprotective effects of H2O2 were still maintained even when applied 7 min after the ischaemic conditions had already been imposed (Figure 3B). Again, the rescuing action of H2O2 (3 mM) was mediated by the CAT-induced formation of O2. In fact, a pretreatment of the slices with the CAT inhibitor (3-AT, 20 mM) blocked this protective effect (Figure 3C). Moreover, we have shown that an increase of the endogenous levels of H2O2, due to a combined bath-application of mercaptosuccinate (MCS, 1 mM) (a potent and specific inhibitor of selenium-dependent GPx) (Chaudiere et al., 1984), and Cu,Zn-SOD (120 U·mL−1), which augments H2O2 production, limited the OGD-induced irreversible depression of fEPSPs. These results were in line with previous observation of neuroprotection afforded by H2O2 against hypoxic insult on DAergic cells (Geracitano et al., 2005) and propose novel therapeutic strategies based on increasing the endogenous tissue levels of H2O2 in the ischaemic brain.

Figure 3.

Protective effects of H2O2 superfusion and pharmacological modulation of enzymatic pathways leading to H2O2 production and degradation. (A) In hippocampal slices, H2O2 (3 mM) exogenously bath-applied during OGD (30 min) exposure-induced irreversible loss of fEPSPs (black circles, n= 6) caused a complete recovery of synaptic function (white circles, n= 6, P < 0.0001) in extracellular recordings. (B) Ability of H2O2 to rescue synaptic transmission even when applied 7 min after OGD had started (black circles, n= 6, P < 0.0001). (C) CAT enzyme is involved in H2O2-mediated neuroprotection: the CAT inhibitor 3-AT (20 mM) prevented H2O2-induced recovery of fEPSPs (black circles, n= 6, P < 0.0001) [A–C modified from Nisticòet al. (2008); copyright BJP, used with permission]. (D) Representative brain coronal sections (2 mm thick), stained with 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC), showing the infarct area (unstained) in rats treated with the GPx inhibitor MCS (150 mg·kg−1) or vehicle (PBS, 1 mL·kg−1), i.p., 15 min before transient (2 h) MCAo followed by 22 h reperfusion. Compared with vehicle-treated animals, systemic administration of MCS significantly decreases brain infarct damage produced by transient MCAo in penumbral areas (n= 4–6 rats per experimental group, P < 0.05). (E) At the cortico-striatal synaptic transmission, exposure to OGD (7 min) (white circles, n= 4) caused a reversible fEPSPs depression, whereas OGD (12 min) caused an irreversible loss of the fEPSPs in extracellular recordings (black circles, n= 11). (F) Treatment with MCS (1 mM) 15 min before and during OGD protected synaptic responses from fEPSPs loss (grey circles, n= 11, P < 0.05). Administration of 3-AT (20 mM, white circles, n= 5) reversed the neuroprotection by MCS indicating a CAT-mediated effect [D–F modified from Amantea et al. (2009); copyright Int Rev Neurobiol, used with permission]. (G) Pretreatment with CAT (500 U·mL−1, 15 min) in the presence of OGD (40 min) plus H2O2 (3 mM) (grey circles, n= 6) induced a complete recovery of fEPSPs against the irreversible loss caused by OGD (40 min) alone (black circles, n= 6, P < 0.005). (H) CAT overexpression in the transgenic mice Tg (CAT) (grey circles, n= 13) in the presence of H2O2 (3 mM) induced a partial recovery of synaptic response from OGD (40 min) which was significantly different compared with WT mice (black circles, n= 10, P < 0.05). (I) The figure shows ·O2− radical formation decrease measured in the CA1 hippocampal region by using fluorescent probe DHE after 1 h of superfusion, in OGD (40 min) exposed-Tg(CAT) slices (lower) as compared with WT group (upper) (n= 3 mice per experimental group, P < 0.05). Scale bar: 25 µm [G–I modified from Armogida et al. (2011); copyright IJIP, used with permission]. In all graphs, data are expressed as means ± SEM; bars indicate the exposure time to compounds and OGD.

Striatum

Little information is as yet available as to whether H2O2 may contribute to neuroprotection in in vivo brain ischaemia because its systemic infusion induces gas embolism which can cause additional occlusions of the vessels. As a matter of fact, there is O2 formation in the vessels due to the ubiquitous localization of the CAT enzyme (Watt et al., 2004; French et al., 2010). As it was not feasible to inject H2O2 intravenously, our aim was to examine the effect of increasing the endogenous levels of H2O2 in an in vivo model of brain ischaemia. This increase has been accomplished through inhibition of GPx by systemic intraperitoneal administration of MCS. We observed that MCS (1.5–150 mg·kg−1) dose dependently decreased brain infarct damage produced by transient (2 h) MCAo in rat (Amantea et al., 2009) (Figure 3D). Interestingly, neuroprotection was observed when MCS was administered 15 min before the ischaemic insult, and no protection was detected when the drug was injected 1 h before MCAo or upon reperfusion. Such results were in accordance with another study showing a prolongation of survival time of rats following 20 min brain ischaemia when pretreated with buthionine sulfoximine (BSO), a drug that is a glutathione depletor (Vanella et al., 1993). BSO could act by decreasing the activity of GPx and thus augmenting the endogenous level of H2O2. Consistent with these findings, superfusion of striatal slices with MCS (1 mM) limited the irreversible cortico-striatal field potential depression caused by OGD (12 min) (Figure 3E,F). Once again, the protective effect of MCS superfusion was lost by concomitant bath-application of 3-AT (20 mM), confirming the involvement of CAT in mediating the functional rescue at the synaptic level (Figure 3F). Thus, MCS resulted in neuroprotection both on in vivo and in vitro ischaemic conditions, through a mechanism which, by blocking GPx, very likely increases endogenous levels of H2O2 and its consequent conversion to O2 and H2O by CAT.

Can the pharmacological modulation of enzymatic pathways leading to an enhanced H2O2 conversion to O2 and H2O be therapeutic?

The therapeutic potential of modulating the enzymatic pathways leading to H2O2 production and its conversion to O2 and H2O (SOD, GPx, CAT) has been previously investigated via either transgenic or pharmacological intervention tools in both in vitro and in vivo ischaemic models. The modification of H2O2 signalling might have a key aspect in the expression of neuronal damage during an episode of IR.

Targeting SOD enzyme

Transgenic mice overexpressing Cu,Zn-SOD enzyme are more resistant to focal brain ischaemia (Yang et al., 1994). However, neither selective deletion nor overexpression of Cu,Zn-SOD affect the outcome of permanent focal brain ischaemia (Chan et al., 1993; Fujimura et al., 2001). On the contrary, Mn-SOD selective deletion worsens the outcome of both transient and permanent MCAo (Murakami et al., 1998; Kim et al., 2002). From these studies it appears that there is the need of a ROS productive reperfusion phase for SOD enzymes to change the fate of the ischaemic tissue (Warner et al., 2004). To our knowledge, no published study has evaluated yet the long-term effects of SOD overexpression on IR outcome and the stability of the achieved protection (Warner et al., 2004). It is known that mice overexpressing Cu,Zn-SOD extracellularly show an increased tolerance to both focal and global brain ischaemia (Sheng et al., 1999a; 2000), whereas extracellular Cu,Zn-SOD knockout mice show greater damage (Sheng et al., 1999b). In agreement with the data obtained in transgenic animals, it has been shown that polyethylene glycol-conjugated SOD has a potential therapeutic effect in ischaemia (Liu et al., 1989). Moreover, nonpeptidyl SOD-mimetics have proven effective in hypoxia–ischaemia injury in immature rats (Shimizu et al., 2003). However, the short half-life, the reduced capability to penetrate the blood–brain barrier and the antigenicity of SOD have limited its pharmacological use.

Targeting GPx enzyme

Also, mice overexpressing GPx are more resistant to ischaemic insult (Weisbrot-Lefkowitz et al., 1998; Furling et al., 2000; Ishibashi et al., 2002). An increased infarct size has been observed in GPx knockout mice (Crack et al., 2001), more likely due to excessive H2O2 accumulation in the brain during reperfusion, whereas the cerebroventricular infusion of exogenous GPx was not able to improve the outcome of global IR (Yano et al., 1998). On the other hand, the non-selective GPx mimetic ebselen has protective effects in several ischaemia models (Warner et al., 2004).

Targeting CAT enzyme

Interestingly, the manipulation of CAT, the other crucial enzyme involved in H2O2 degradation, has given more homogeneous results against the ischaemic insult. In fact, CAT overexpression in the heart of transgenic mice has been shown to provide myocardial protection against IR injury (Mele et al., 2006). Additional strategies based on exogenously administered CAT enzyme (Forsman et al., 1988; Castillo et al., 1990) or on CAT overexpression by viral vector have been used to examine its protective role in IR injury both in in vitro and in vivo systems (Wang et al., 2003; Gu et al., 2004; Gáspár et al., 2009; Kim et al., 2009; Zemlyak et al., 2009; Ushitora et al., 2010; Chen and Tang, 2011). Of note, systemic infusion of CAT failed to improve neurological deficits after complete ischaemia (Forsman et al., 1988), but resulted in a decrease of myocardial injury following coronary ischaemia (Gardner et al., 1983). In the light of our recent findings demonstrating a CAT-mediated neuroprotective effect of H2O2 in oxygen-deprived brain slices of the substantia nigra, hippocampus, striatum and in an in vivo model of transient focal brain ischaemia (Geracitano et al., 2005; Nisticòet al., 2008; Amantea et al., 2009), we have also investigated whether either the exogenous administration or the overexpression of CAT is protective in in vitro and in vivo brain ischaemic models (Armogida et al., 2011). Along with previous studies, our findings indicate that hippocampal synaptic transmission was restored only when CAT (500 U·mL−1, 15 min) was bath-applied before a relative long period of OGD (40 min, that in control condition kills the neurons) in combination with H2O2 (3 mM) (Figure 3G). The CAT-induced neuroprotection was also confirmed in a transgenic mouse overexpressing the enzyme CAT [Tg(CAT)]. In fact, an increased resistance of hippocampal slices against OGD compared with wild-type (WT) animals was observed in the presence of H2O2 (Figure 3H). Furthermore, Tg(CAT) mice showed a decreased infarct size after MCAo compared with WT mice. By using DHE detection, we also observed lower levels of ROS likely reflecting increased ROS metabolism in the Tg(CAT) compared with WT mice 1 h after OGD (40 min) condition (Figure 3I). Interestingly, CAT pretreatment blunted the damaging effect of H2O2 in normoxic conditions. In fact, it decreased fEPSPs depression evoked by repeated applications of H2O2. Notably, a lower sensitivity to H2O2-mediated field depression, very likely due to a better functioning of CAT, was indicated by the rightward shift of the H2O2-induced concentration-response curve in Tg(CAT) compared with WT mice.

Targeting SOD and CAT enzymes simultaneously

Conjugation with macromolecules such as liposome-entrapped SOD and CAT (Yusa et al., 1984), polyethylene glycol derivatives (Liu et al., 1989; Armstead et al., 1992; Yabe et al., 1999) or synthetic SOD–CAT mimetics (such as salen–manganese complexes and manganese porphyrins) exhibiting both SOD and CAT activities (Baker et al., 1998; Doctrow et al., 2002; Zhou et al., 2007; Zhou and Baudry, 2009) has been carried out to facilitate antioxidant compounds delivery to the brain tissue and to increase enzymatic bioavailability and half-life. Either exogenous SOD or CAT delivered into living cells through transduction-mediated cell-penetrating peptide PEP-1 fusion proteins protected myocardium from IR damage in rats. Furthermore, the combined transduction of PEP-1-SOD1 and PEP-1-CAT enhanced their protective effect (Huang et al., 2011). Interestingly, targeted cell-penetrating CAT derivative with enhanced peroxisome targeting efficiency (CAT-SKL) delivery also protected neonatal rat myocytes from IR injury (Undyala et al., 2011). Moreover, the administration of SOD/CAT mimetics before ischaemia has been reported to be neuroprotective in animal model of brain ischaemia (Sharma and Gupta, 2007).

H2O2 as a preconditioning factor in neuroprotection

Another important aspect to consider is the implication of H2O2 in the ischaemic preconditioning (IPC) phenomenon by which a brief sub-lethal ischaemic episode induces tolerance against subsequent prolonged ischaemia that usually induces lethal damage. Cardioprotective (Yaguchi et al., 2003) and neuroprotective effects of H2O2 have been observed in several in vitro models of IPC (Furuichi et al., 2005; Xiao-Qing et al., 2005). In fact, it has been demonstrated that the generation of H2O2 during brief OGD (10 min) induces IPC in rat primary cultured cortex neurons (Furuichi et al., 2005). In addition, H2O2, at low concentration (10 µM), can protect PC12 cell line against DA-induced apoptosis most likely by restoring mitochondrial function (Xiao-Qing et al., 2005). Accordingly, in a study conducted by Simerabet et al. (2008), the stereotactic in situ infusion of H2O2 (2 mM) decreased rat cerebral infarct size (cortical area) 24 h after MCAo (1 h), suggesting an involvement of H2O2 during the induction phase of IPC (Simerabet et al., 2008). Moreover, in another study carried out by Chang et al. (2008), exogenous low concentration of H2O2 (15 µM) may contribute to IPC against OGD (24 h) in rat primary neurons by increasing HIF-1α protein expression.

Conclusions and future directions

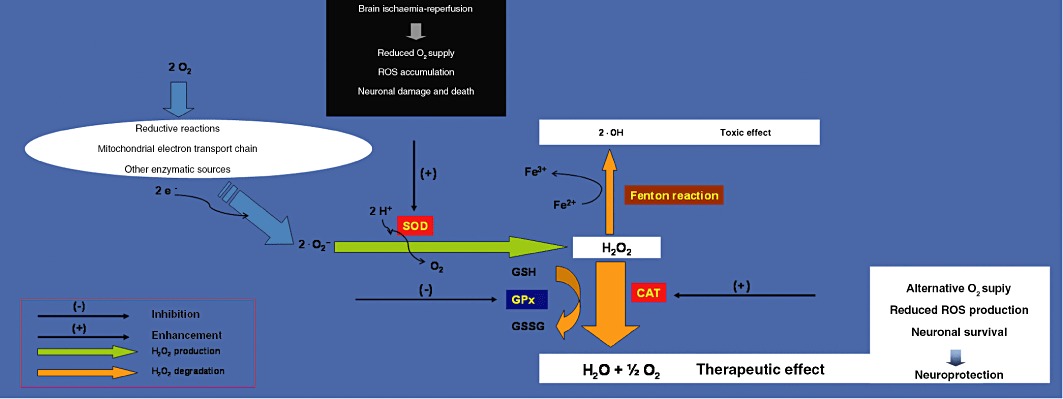

At present, ischaemic stroke is the second-leading cause of death worldwide and represents a serious unmet medical need. Although therapeutic interventions such as thrombolytic therapy with recombinant tissue plasminogen activator have been shown to be effective (Wechsler, 2011), a ‘neuroprotective strategy’, preventing or lessening the damaging components of the ischaemic cascade, has not been unequivocally demonstrated in clinical trials (Fisher, 2011). Failure of such programmes could be attributable to both insufficient preclinical models and clinical designs (Fisher, 2011; Macrae, 2011). The data discussed in the present review suggest exploiting possible neuroprotective strategies based on targeting H2O2 metabolism in stroke. In spite of the fact that no clinical studies have been conducted evaluating the therapeutic usage of drugs targeting H2O2 metabolism in stroke, the experimental observations obtained so far by our and other groups support the idea that H2O2 might represent an attractive target for the development of novel therapies to diminish the burden of brain ischaemia. Thus, according to our hypothesis, neuroprotection in ischaemia could be principally obtained by two mechanisms when the H2O2 metabolism is pharmacologically manipulated to boost CAT pathway: (i) one mechanism produces a supplementary source of O2 to partially compensate for the lack of O2 that occurs in the ischaemic cerebral tissue (this role could be more prominent in the ischaemic phase); and (ii) the other is characterized by enhanced CAT which detoxifies more easily brain tissue from ROS, thus decreasing the accumulation of H2O2 and the radical •OH derived from H2O2 excess (this role could be more prominent during the reperfusion phase when there is an increased generation of ROS) (Figure 4). Therefore, pharmacological agents effective in the treatment of brain ischaemia should obtain an increase in the level of H2O2 by blocking GPx preferably associated to an increased enzymatic activity of SOD and CAT. Indeed, in the study conducted by Avshalumov et al. (2004), either GPx or CAT inhibition enhanced H2O2 toxicity in rat hippocampal slices, confirming the importance of the integrity of glial antioxidant network and supporting further CAT pathway enhancement rather than GPx inhibition in the prevention of pathophysiological consequences.

Figure 4.

Working model of proposed enzymatic targets of H2O2 metabolism for the treatment of brain ischaemia. A therapeutic effect against brain ischaemia could be achieved by the pharmacological modulation of H2O2 producing (SOD) and degrading enzymes (CAT and GPx). In in vitro and in vivo brain ischaemia models, neuroprotection is afforded via CAT pathway activation mainly through two mechanisms: supplementary production of O2 to compensate for the lack of O2 and detoxification from H2O2 derived •OH radical associated-oxidative stress.

In addition, of paramount importance for the therapeutic potential of such treatment is the decrease of the damaging effects of H2O2 in normoxic conditions (e.g. by using potent antioxidant agents) and the rapid boost of H2O2 enzymatic degradation to O2 through the CAT pathway (e.g. by using efficient SOD-CAT mimetics). We believe that the therapeutic potential of drugs targeting H2O2 metabolism needs to be explored in depth at a preclinical level in order to transform their theoretical use in brain ischaemia in a true clinical application. A future challenge in the hands of neuroscientists is to validate an H2O2 signalling-mediated pharmacological treatment of stroke.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr Maria Lo Ponte for her linguistic revision of the manuscript. We also wish to thank the Reviews Editor, Dr Mike Curtis, and the anonymous co-Editor and reviewers for their perceptive and helpful comments.

Glossary

- 3-AT

3-amino-1,2,4-triazole

- ACSF

artificial cerebral spinal fluid

- BSO

buthionine sulfoximine

- CAT

catalase

- DA

dopamine

- DHE

dihydroethidium

- fEPSP

field excitatory postsynaptic potential

- GPx

glutathione peroxidase

- HIF

hypoxia-inducible factor

- IPC

ischaemic preconditioning

- IR

ischaemia-reperfusion

- KATP

ATP-sensitive K+ channel

- MCAo

middle cerebral artery occlusion

- MCS

mercaptosuccinate

- mTOR

mammalian target of rapamycin

- NF

nuclear factor

- NOS

nitric oxide synthase

- O2

molecular oxygen

- ·O2−

superoxide anion

- OGD

oxygen/glucose-deprivation

- •OH

hydroxyl radical

- PGC1α

PPARγ coactivator1α

- PI3K

phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase

- PPARγ

peroxisome proliferator-activated receptorγ

- Prx

peroxiredoxin

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- SNc

substantia nigra pars compacta

- SOD

superoxide dismutase

- TDP

thiolate-dependent phosphatase

- Tg(CAT)

transgenic mouse over-expressing catalase

- TRP

transient receptor potential

- WT

wild-type

Conflict of interest

The authors state no conflict of interest with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article.

References

- Alexander SPH, Mathie A, Peters JA. Guide to Receptors and Channels (GRAC), 5th Edition. Br J Pharmacol. 2011;164(Suppl. 1):S1–S324. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01649_1.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amantea D, Marrone MC, Nisticò R, Federici M, Bagetta G, Bernardi G, et al. Oxidative stress in stroke pathophysiology validation of hydrogen peroxide metabolism as a pharmacological target to afford neuroprotection. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2009;85:363–374. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7742(09)85025-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antunes F, Cadenas E. Estimation of H2O2 gradients across biomembranes. FEBS Lett. 2000;475:121–126. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01638-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appleman D, Heim WG, Pyfrom HT. Effects of 3-amino-1, 2, 4-triazole (AT) on catalase and other compounds. Am J Physiol. 1956;186:19–23. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1956.186.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armogida M, Spalloni A, Amantea D, Nutini M, Petrelli F, Longone P, et al. On the protective role of catalase against cerebral ischemia in vitro and in vivo. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2011;24:735–747. doi: 10.1177/039463201102400320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstead WM, Mirro R, Thelin OP, Shibata M, Zuckerman SL, Shanklin DR, et al. Polyethylene glycol superoxide dismutase and catalase attenuate increased blood-brain barrier permeability after ischemia in piglets. Stroke. 1992;23:755–762. doi: 10.1161/01.str.23.5.755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auerbach JM, Segal M. Peroxide modulation of slow onset potentiation in rat hippocampus. J Neurosci. 1997;17:8695–8701. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-22-08695.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avshalumov MV, Chen BT, Marshall SP, Peña DM, Rice ME. Glutamate-dependent inhibition of dopamine release in striatum is mediated by a new diffusible messenger, H2O2. J Neurosci. 2003;23:2744–2750. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-07-02744.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avshalumov MV, MacGregor DG, Sehgal LM, Rice ME. The glial antioxidant network and neuronal ascorbate: protective yet permissive for H(2)O(2) signaling. Neuron Glia Biol. 2004;1:365–376. doi: 10.1017/S1740925X05000311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avshalumov MV, Chen BT, Kóos T, Tepper JM, Rice ME. Endogenous hydrogen peroxide regulates the excitability of midbrain dopamine neurons via ATP-sensitive potassium channels. J Neurosci. 2005;25:4222–4231. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4701-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avshalumov MV, Patel JC, Rice ME. AMPA receptor dependent H2O2 generation in striatal medium spiny neurons, but not dopamine axons: one source of a retrograde signal that can inhibit dopamine release. J Neurophysiol. 2008;100:1590–1601. doi: 10.1152/jn.90548.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker K, Bucay-Marcus C, Huffman C, Kruk H, Malfroy B, Doctrow SR. Synthetic combined superoxide dismutase/catalase mimetics are protective as a delayed treatment in a rat stroke model: a key role for reactive oxygen species in ischemic brain injury. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1998;284:215–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao L, Avshalumov MV, Patel JC, Lee CR, Miller EW, Chang CJ, et al. Mitochondria are the source of hydrogen peroxide for dynamic brain-cell signaling. J Neurosci. 2009;29:9002–9010. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1706-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bienert GP, Schjoerring JK, Jahn TP. Membrane transport of hydrogen peroxide. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1758:994–1003. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2006.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bienert GP, Møller AL, Kristiansen KA, Schulz A, Møller IM, Schjoerring JK, et al. Specific aquaporins facilitate the diffusion of hydrogen peroxide across membranes. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:1183–1192. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603761200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boveris A, Chance B. The mitochondrial generation of hydrogen peroxide. General properties and effect of hyperbaric oxygen. Biochem J. 1973;134:707–716. doi: 10.1042/bj1340707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunet A, Sweeney LB, Sturgill JF, Chua KF, Greer PL, Lin Y, et al. Stress-dependent regulation of FOXO transcription factors by the SIRT1 deacetylase. Science. 2004;303:2011–2015. doi: 10.1126/science.1094637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai H. Hydrogen peroxide regulation of endothelial function: origins, mechanisms, and consequences. Cardiovasc Res. 2005;68:26–36. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castillo M, Toledo-Pereyra LH, Shapiro E, Guerra E, Prough D, Frantzi P. Protective effect of allopurinol, catalase, or superoxide dismutase in ischemic rat liver. Transplant Proc. 1990;22:490–491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan PH, Kamii H, Yang GY, Gafni J, Epstein CJ, Carlson E, et al. Brain infarction is not reduced in SOD-1 transgenic mice after a permanent focal cerebral ischemia. Neuroreport. 1993;5:293–296. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199312000-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang S, Jiang X, Zhao C, Lee C, Ferriero DM. Exogenous low dose hydrogen peroxide increases hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha protein expression and induces preconditioning protection against ischemia in primary cortical neurons. Neurosci Lett. 2008;441:134–138. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudiere J, Wilhelmsen EC, Tappel AL. Mechanism of selenium-glutathione peroxidase and its inhibition by mercaptocarboxylic acids and other mercaptans. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:1043–1050. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen B, Tang L. Protective effects of catalase on retinal ischemia/reperfusion injury in rats. Exp Eye Res. 2011;93:599–606. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2011.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen BT, Avshalumov MV, Rice ME. H2O2 is a novel, endogenous modulator of synaptic dopamine release. J Neurophysiol. 2001;85:2468–2476. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.85.6.2468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Xu B, Liu L, Luo Y, Yin J, Zhou H, et al. Hydrogen peroxide inhibits mTOR signaling by activation of AMPKalpha leading to apoptosis of neuronal cells. Lab Invest. 2010;90:762–773. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2010.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen G. Enzymatic/nonenzymatic sources of oxyradicals and regulation of antioxidant defenses. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1994;738:8–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1994.tb21784.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colton CA, Fagni L, Gilbert D. The action of hydrogen peroxide on paired pulse and long-term potentiation in the hippocampus. Free Radic Biol Med. 1989;7:3–8. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(89)90093-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crack PJ, Taylor JM, Flentjar NJ, de Haan J, Hertzog P, Iannello RC, et al. Increased infarct size and exacerbated apoptosis in the glutathione peroxidase-1 (Gpx-1) knockout mouse brain in response to ischemia/reperfusion injury. J Neurochem. 2001;78:1389–1399. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00535.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Autréaux B, Toledano MB. ROS as signalling molecules: mechanisms that generate specificity in ROS homeostasis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:813–824. doi: 10.1038/nrm2256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doctrow SR, Huffman K, Marcus CB, Tocco G, Malfroy E, Adinolfi CA, et al. Salen-manganese complexes as catalytic scavengers of hydrogen peroxide and cytoprotective agents: structure-activity relationship studies. J Med Chem. 2002;45:4549–4558. doi: 10.1021/jm020207y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dringen R, Pawlowski PG, Hirrlinger J. Peroxide detoxification by brain cells. J Neurosci Res. 2005;79:157–165. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durukan A, Tatlisumak T. Ischemic stroke in mice and rats. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;573:95–114. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-247-6_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farr CH. Physiological and biochemical responses to intravenous hydrogen peroxide in man. J Adv Med. 1988;l:113–l29. [Google Scholar]

- Finkel T. Signal transduction by reactive oxygen species. J Cell Biol. 2011;194:7–15. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201102095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finney JW, Urschel HC, Balla GA, Race GJ, Jay BE, Pingree HP, et al. Protection of the ischemic heart with DMSO alone or DMSO with hydrogen peroxide. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1967;141:231–241. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1967.tb34884.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher M. New approaches to neuroprotective drug development. Stroke. 2011;42:S24–S27. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.592394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flamm ES, Demopoulus HB, Seligman ML, Poser RG, Ranoshoff J. Free radicals in cerebral ischemia. Stroke. 1978;9:445–447. doi: 10.1161/01.str.9.5.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsman M, Fleischer JE, Milde JH, Stehen PA, Michenfelder JD. Superoxide dismutase and catalase failed to improve neurologic outcome after complete cerebral ischemia in the dog. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1988;32:152–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.1988.tb02705.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler JC. Hydrogen peroxide opposes the hypoxic depression of evoked synaptic transmission in rat hippocampal slices. Brain Res. 1997;766:255–258. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)00699-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French LK, Horowitz BZ, McKeown NJ. Hydrogen peroxide ingestion associated with portal venous gas and treatment with hyperbaric oxygen: a case series and review of the literature. Clin Toxicol. 2010;48:533–538. doi: 10.3109/15563650.2010.492526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fridovich I. Superoxide radical and superoxide dismutases. Annu Rev Biochem. 1995;64:97–112. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.64.070195.000525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimura M, Morita-Fujimura Y, Noshita N, Sugawara T, Kawase M, Chan PH. The cytosolic antioxidant copper/zinc-superoxide dismutase prevents the early release of mitochondrial cytochrome c in ischemic brain after transient focal cerebral ischemia in mice. J Neurosci. 2000;20:2817–2824. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-08-02817.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimura M, Morita-Fujimura Y, Copin J, Yoshimoto T, Chan PH. Reduction of copper,zinc-superoxide dismutase in knockout mice does not affect edema or infarction volumes and the early release of mitochondrial cytochrome c after permanent focal cerebral ischemia. Brain Res. 2001;889:208–213. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)03134-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furling D, Ghribi O, Lahsaini A, Mirault ME, Massicotte G. Impairment of synaptic transmission by transient hypoxia in hippocampal slices: improved recovery in glutathione peroxidase transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:4351–4356. doi: 10.1073/pnas.060574597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furuichi T, Liu W, Shi H, Miyake M, Liu KJ. Generation of hydrogen peroxide during brief oxygen-glucose deprivation induces preconditioning neuronal protection in primary cultured neurons. J Neurosci Res. 2005;79:816–824. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner TJ, Stewart JR, Casale AS, Downey JM, Chambers DE. Reduction of myocardial ischemic injury with oxygen-derived free radical scavengers. Surgery. 1983;94:423–427. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gáspár T, Domoki F, Lenti L, Institoris A, Snipes JA, Bari F, et al. Neuroprotective effect of adenoviral catalase gene transfer in cortical neuronal cultures. Brain Res. 2009;1270:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geracitano R, Tozzi A, Berretta N, Florenzano F, Guatteo E, Viscomi MT, et al. Protective role of hydrogen peroxide in oxygen-deprived dopaminergic neurones of the rat substantia nigra. J Physiol. 2005;568:97–110. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.092510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerich FJ, Funke F, Hildebrandt B, Fasshauer M, Müller M. H2O2-mediated modulation of cytosolic signaling and organelle function in rat hippocampus. Pflugers Arch. 2009;458:937–952. doi: 10.1007/s00424-009-0672-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giaginis C, Tsourouflis G, Theocharis S. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma (PPAR-gamma) ligands: novel pharmacological agents in the treatment of ischemia reperfusion injury. Curr Mol Med. 2008;8:562–579. doi: 10.2174/156652408785748022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giorgio M, Trinei M, Migliaccio E, Pelicci PG. Hydrogen peroxide: a metabolic by-product or a common mediator of ageing signals? Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:722–728. doi: 10.1038/nrm2240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Góth L. [The hydrogen peroxide paradox] Orv Hetil. 2006;147:887–893. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gough DR, Cotter TG. Hydrogen peroxide: a Jekyll and Hyde signalling molecule. Cell Death Dis. 2011;2:e213. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2011.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham DG, Tiffany SM, Bell WR, Jr, Gutknecht WF. Autoxidation versus covalent binding of quinones as the mechanism of toxicity of dopamine, 6-hydroxydopamine, and related compounds toward C1300 neuroblastoma cells in vitro. Mol Pharmacol. 1978;14:644–653. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green S. Oxygenation therapy: unproven treatments for cancer and AIDS. Sci Rev Altern Med. 1998;2:6–13. Available at: http://www.quackwatch.org/01QuackeryRelatedTopics/Cancer/oxygen.html (accessed 27 July 2011) [Google Scholar]

- Groeger G, Quiney C, Cotter TG. Hydrogen peroxide as a cell-survival signaling molecule. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2009;11:2655–2671. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu W, Zhao H, Yenari MA, Sapolsky RM, Steinberg GK. Catalase over-expression protects striatal neurons from transient focal cerebral ischemia. Neuroreport. 2004;15:413–416. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200403010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halliwell B. Reactive oxygen species and the central nervous system. J Neurochem. 1992;59:1609–1623. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1992.tb10990.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halliwell B. Antioxidant defence mechanisms: from the beginning to the end (of the beginning) Free Radic Res. 1999;31:261–272. doi: 10.1080/10715769900300841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halliwell B, Gutteridge JMC. Free radicals, other reactive species and disease. In: Halliwell B, Gutteridge JMC, editors. Free Radicals in Biology and Medicine. Oxford: Clarendon Press; 1999. pp. 617–783. [Google Scholar]

- Halliwell B, Clement MV, Long LH. Hydrogen peroxide in the human body. FEBS Lett. 2000;486:10–13. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)02197-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Horst A, Tertoolen LG, de Vries-Smits LM, Frye RA, Medema RH, Burgering BM. FOXO4 is acetylated upon peroxide stress and deacetylated by the longevity protein hSir2(SIRT1) J Biol Chem. 2004;279:28873–28879. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401138200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang GQ, Wang JN, Tang JM, Zhang L, Zheng F, Yang JY, et al. The combined transduction of copper, zinc-superoxide dismutase and catalase mediated by cell-penetrating peptide, PEP-1, to protect myocardium from ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Transl Med. 2011;9:73. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-9-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyslop PA, Zhang Z, Pearson DV, Phebus LA. Measurement of striatal H2O2 by microdialysis following global forebrain ischemia and reperfusion in the rat: correlation with the cytotoxic potential of H2O2 in vitro. Brain Res. 1995;671:181–186. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)01291-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishibashi N, Prokopenko O, Weisbrot-Lefkowitz M, Reuhl KR, Mirochnitchenko O. Glutathione peroxidase inhibits cell death and glial activation following experimental stroke. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2002;109:34–44. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(02)00459-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamsler A, Segal M. Hydrogen peroxide modulation of synaptic plasticity. J Neurosci. 2003;23:269–276. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-01-00269.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katsuki H, Nakanishi C, Saito H, Matsuki N. Biphasic effect of hydrogen peroxide on field potentials in rat hippocampal slices. Eur J Pharmacol. 1997;337:213–218. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(97)01323-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaundal RK, Sharma SS. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma agonists as neuroprotective agents. Drug News Perspect. 2010;23:241–256. doi: 10.1358/dnp.2010.23.4.1437710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim DW, Jeong HJ, Kang HW, Shin MJ, Sohn EJ, Kim MJ, et al. Transduced human PEP-1-catalase fusion protein attenuates ischemic neuronal damage. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;47:941–952. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.06.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim GW, Kondo T, Noshita N, Chan PH. Manganese superoxide dismutase deficiency exacerbates cerebral infarction after focal cerebral ischemia/reperfusion in mice: implications for the production and role of superoxide radicals. Stroke. 2002;33:809–815. doi: 10.1161/hs0302.103745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirino T. Delayed neuronal death in the gerbil hippocampus following ischemia. Brain Res. 1982;239:57–69. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(82)90833-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klann E, Thiels E. Modulation of protein kinases and proteinc phosphatases by reactive oxygen species: implications for hippocampal synaptic plasticity. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 1999;23:359–376. doi: 10.1016/s0278-5846(99)00002-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lees GJ, Leong W. The sodium-potassium ATPase inhibitor ouabain is neurotoxic in the rat substantia nigra and striatum. Neurosci Lett. 1995;188:113–116. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(95)11413-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei B, Adachi N, Arai T. Measurement of the extracellular H2O2 in the brain by microdialysis. Brain Res Brain Res Protoc. 1998;3:33–36. doi: 10.1016/s1385-299x(98)00018-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipsanen A, Jolkkonen J. Experimental approaches to study functional recovery following cerebral ischemia. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2011;68:3007–3017. doi: 10.1007/s00018-011-0733-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipton P. Ischemic cell death in brain neurons. Physiol Rev. 1999;79:1431–1568. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.4.1431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu TH, Beckman JS, Freeman BA, Hogan EL, Hsu CY. Polyethylene glycol-conjugated superoxide dismutase and catalase reduce ischemic brain injury. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1989;256:H589–H593. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1989.256.2.H589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Love IN. Peroxide of Hydrogen as a remedial agent. JAMA. 1888;10:262–265. [Google Scholar]

- Ma HP. Hydrogen peroxide stimulates the epithelial sodium channel through a phosphatidylinositide 3-kinase-dependent pathway. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:32444–32453. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.254102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macrae I. Preclinical stroke research – advantages and disadvantages of the most common rodent models of focal ischaemia. Br J Pharmacol. 2011;164:1062–1078. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01398.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margoliash E, Novogrodsky A. A study of the inhibition of catalase by 3-amino-1:2:4:-triazole. Biochem J. 1958;68:468–475. doi: 10.1042/bj0680468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mele J, Van Remmen H, Vijg J, Richardson A. Characterization of transgenic mice that overexpress both copper zinc superoxide dismutase and catalase. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2006;8:628–638. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercuri NB, Bonci A, Calabresi P, Stratta F, Bernardi G. Responses of rat mesencephalic dopaminergic neurons to a prolonged period of oxygen deprivation. Neuroscience. 1994;63:757–764. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)90520-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller EW, Albers AE, Pralle A, Isacoff EY, Chang CJ. Boronate-based fluorescent probes for imaging cellular hydrogen peroxide. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:16652–16659. doi: 10.1021/ja054474f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller EW, Tulyathan O, Isacoff EY, Chang CJ. Molecular imaging of hydrogen peroxide produced for cell signaling. Nat Chem Biol. 2007;3:263–267. doi: 10.1038/nchembio871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller EW, Dickinson BC, Chang CJ. Aquaporin-3 mediates hydrogen peroxide uptake to regulate downstream intracellular signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:15681–15686. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005776107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishina NM, Tyurin-Kuzmin PA, Markvicheva KN, Vorotnikov AV, Tkachuk VA, Laketa V, et al. Does cellular hydrogen peroxide diffuse or act locally? Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011;14:1–7. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami K, Kondo T, Kawasr M, Li Y, Sato S, Chen SF, et al. Mitochondrial susceptibility to oxidative stress exacerbates cerebral infarction that follows permanent focal cerebral ischemia in mutant mice with manganese superoxide dismutase deficiency. J Neurosci. 1998;18:205–213. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-01-00205.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nisticò R, Piccirilli S, Cucchiaroni ML, Armogida M, Guatteo E, Giampà C, et al. Neuroprotective effect of hydrogen peroxide on an in vitro model of brain ischaemia. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;153:1022–1029. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira-Marques V, Marinho HS, Cyrne L, Antunes F. Role of hydrogen peroxide in NF-kappaB activation: from inducer to modulator. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2009;11:2223–2243. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver TH, Cantab BC, Murphy DV. Influenzal pneumonia: the intravenous injection of hydrogen peroxide. Lancet. 1920;1:432–433. [Google Scholar]

- Pellmar TC. Peroxide alters neuronal excitability in the CA1 region of guinea-pig hippocampus in vitro. Neuroscience. 1987;23:447–456. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(87)90068-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulsinelli WA, Brierley JB, Plum F. Temporal profile of neuronal damage in a model of transient forebrain ischemia. Ann Neurol. 1982;11:491–498. doi: 10.1002/ana.410110509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhee SG. H2O2, a necessary evil for cell signaling. Science. 2006;312:1882–1883. doi: 10.1126/science.1130481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhee SG, Bae YS, Lee SR, Kwon J. Hydrogen peroxide: a key messenger that modulates protein phosphorylation through cysteine oxidation. Sci STKE. 2000;2000:pe1. doi: 10.1126/stke.2000.53.pe1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice ME. H2O2: a dynamic neuromodulator. Neuroscientist. 2011;17:389–406. doi: 10.1177/1073858411404531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenbein CF. On ozone and oronic actions in mushrooms. Phil Mag. 1856;11:137–141. [Google Scholar]

- Sen CK, Packer L. Antioxidant and redox regulation of gene transcription. FASEB J. 1996;10:709–720. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.10.7.8635688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma SS, Gupta S. Neuroprotective effect of MnTMPyP, a superoxide dismutase/catalase mimetic in global cerebral ischemia is mediated through reduction of oxidative stress and DNA fragmentation. Eur J Pharmacol. 2007;561:72–79. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.12.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng H, Bart RD, Oury TD, Pearlstein RD, Crapo JD, Warner DS. Mice overexpressing extracellular superoxide dismutase have increased resistance to focal cerebral ischemia. Neuroscience. 1999a;88:185–191. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00208-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng H, Brody T, Pearlstein RD, Crapo J, Warner DS. Extracellular superoxide dismutase deficient mice have decreased resistance to focal cerebral ischemia. Neurosci Lett. 1999b;267:13–17. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(99)00316-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng H, Kudo M, Mackensen GB, Pearlstein RD, Crapo JD, Warner DS. Mice overexpressing extracellular superoxide dismutase have increased tolerance to global cerebral ischemia. Exp Neurol. 2000;163:392–398. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2000.7363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu K, Rajapakse N, Horiguchi T, Payne RM, Busija DW. Protective effect of a new nonpeptidyl mimetic of SOD, M40401, against focal cerebral ischemia in the rat. Brain Res. 2003;963:8–14. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)03796-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simerabet M, Robin E, Aristi I, Adamczyk S, Tavernier B, Vallet B, et al. Preconditioning by an in situ administration of hydrogen peroxide: involvement of reactive oxygen species and mitochondrial ATP-dependent potassium channel in a cerebral ischemia-reperfusion model. Brain Res. 2008;1240:177–184. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.08.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sims NR, Anderson MF. Mitochondrial contributions to tissue damage in stroke. Neurochem Int. 2002;40:511–526. doi: 10.1016/s0197-0186(01)00122-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith ML, Auer RN, Siesjö BK. The density and distribution of ischemic brain injury in the rat following 2-10 min of forebrain ischemia. Acta Neuropathol. 1984;64:319–332. doi: 10.1007/BF00690397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone JR, Yang S. Hydrogen peroxide: a signaling messenger. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2006;8:243–270. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St-Pierre J, Drori S, Uldry M, Selvaggi JM, Rhee J, Jäger S, et al. Suppression of reactive oxygen species and neurodegeneration by the PGC-1 transcriptional coactivators. Cell. 2006;127:397–408. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundaresan M, Yu ZX, Ferrans VJ, Irani K, Finkel T. Requirement for generation of H2O2 for platelet-derived growth factor signal transduction. Science. 1995;270:296–299. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5234.296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thénard LJ. Observations sur des nouvelles combinaisons entre l'oxigène et divers acides. Ann Phys. 1818;8:306–312. [Google Scholar]

- Tipton KF. The reaction pathway of pig brain mitochondrial monoamine oxidase. Eur J Biochem. 1968;5:316–320. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1968.tb00372.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tipton KF, Boyce S, O'Sullivan J, Davey GP, Healy J. Monoamine oxidases: certainties and uncertainties. Curr Med Chem. 2004;11:1965–1982. doi: 10.2174/0929867043364810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Topper JN, Cai J, Falb D, Gimbrone MA., Jr Identification of vascular endothelial genes differentially responsive to fluid mechanical stimuli: cyclooxygenase-2, manganese superoxide dismutase, and endothelial cell nitric oxide synthase are selectively up-regulated by steady laminar shear stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:10417–10422. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.19.10417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traystman RJ, Kirsch JR, Koehler RC. Oxygen radical mechanisms of brain injury following ischemia and reperfusion. J Appl Physiol. 1991;71:1185–1195. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1991.71.4.1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Undyala V, Terlecky SR, Vander Heide RS. Targeted intracellular catalase delivery protects neonatal rat myocytes from hypoxia-reoxygenation and ischemia-reperfusion injury. Cardiovasc Pathol. 2011;20:272–280. doi: 10.1016/j.carpath.2010.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urschel HC., Jr Progress in cardiovascular surgery. Cardiovascular effects of hydrogen peroxide: current status. Dis Chest. 1967;51:180–192. doi: 10.1378/chest.51.2.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ushitora M, Sakurai F, Yamaguchi T, Nakamura S, Kondoh M, Yagi K, et al. Prevention of hepatic ischemia-reperfusion injury by pre-administration of catalase-expressing adenovirus vectors. J Control Release. 2010;142:431–437. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2009.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valko M, Leibfritz D, Moncol J, Cronin MT, Mazur M, Telser J. Free radicals and antioxidants in normal physiological functions and human disease. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2007;39:44–84. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanella A, Di Giacomo C, Sorrenti V, Russo A, Castorina C, Campisi A, et al. Free radical scavenger depletion in post-ischemic reperfusion brain damage. Neurochem Res. 1993;18:1337–1340. doi: 10.1007/BF00975056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veal EA, Day AM, Morgan BA. Hydrogen peroxide sensing and signaling. Mol Cell. 2007;26:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walton K, Fulton B. Hydrogen peroxide as a source of molecular oxygen for in vitro mammalian CNS preparations. Brain Res. 1983;278:387–393. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(83)90280-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Cheng E, Brooke S, Chang P, Sapolsky R. Over-expression of antioxidant enzymes protects cultured hippocampal and cortical neurons from necrotic insults. J Neurochem. 2003;87:1527–1534. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.02123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner DS, Sheng H, Batinić-Haberle I. Oxidants, antioxidants and the ischemic brain. J Exp Biol. 2004;207:3221–3231. doi: 10.1242/jeb.01022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watt BE, Proudfoot AT, Vale JA. Hydrogen peroxide poisoning. Toxicol Rev. 2004;23:51–57. doi: 10.2165/00139709-200423010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler LR. Intravenous thrombolytic therapy for acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2138–2146. doi: 10.1056/NEJMct1007370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisbrot-Lefkowitz M, Reuhl K, Perry B, Chan PH, Inouye M, Mirochnitchenko O. Overexpression of human glutathione peroxidase protects transgenic mice against focal cerebral ischemia/reperfusion damage. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1998;53:333–338. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(97)00313-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White BC, Sullivan JM, DeGracia DJ, O'Neil BJ, Neumar RW, Grossman LI, et al. Brain ischemia and reperfusion: molecular mechanisms of neuronal injury. J Neurol Sci. 2000;179:1–33. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(00)00386-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willhelm SF. Personal Communication from Fr. Richard Willhelm. Naples, FL: Enlightened Catholic Health Organization (ECHO); 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Winterbourn CC. Reconciling the chemistry and biology of reactive oxygen species. Nat Chem Biol. 2008;4:278–286. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolffenstein R. Concentration und Destillation von Wasserstoffsuperoxyd. Ber Dtsch Chem Ges. 1894;27:3307–3312. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao-Qing T, Jun-Li Z, Yu C, Jian-Qiang F, Pei-Xi C. Hydrogen peroxide preconditioning protects PC12 cells against apoptosis induced by dopamine. Life Sci. 2005;78:61–66. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2005.04.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yabe Y, Nishikawa M, Tamada A, Takakura Y, Hashida M. Targeted delivery and improved therapeutic potential of catalase by chemical modification: combination with superoxide dismutase derivatives. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;289:1176–1184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaguchi Y, Satoh H, Wakahara N, Katoh H, Uehara A, Terada H, et al. Protective effects of hydrogen peroxide against ischemia/ reperfusion injury in perfused rat hearts. Circ J. 2003;67:253–258. doi: 10.1253/circj.67.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang G, Chan PH, Chen J, Carlson E, Chen SF, Weinstein P, et al. Human copper-zinc superoxide dismutase transgenic mice are highly resistant to reperfusion injury after focal cerebral ischemia. Stroke. 1994;25:165–170. doi: 10.1161/01.str.25.1.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yano T, Ushijima K, Terasaki H. Failure of glutathione peroxidase to reduce transient ischemic injury in the rat hippocampal CA1 subfield. Resuscitation. 1998;39:91–98. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9572(98)00115-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yusa T, Crapo JD, Freeman BA. Liposome-mediated augmentation of brain SOD and catalase inhibits CNS O2 toxicity. J Appl Physiol. 1984;57:1674–1681. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1984.57.6.1674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zemlyak I, Brooke SM, Singh MH, Sapolsky RM. Effects of overexpression of antioxidants on the release of cytochrome c and apoptosis-inducing factor in the model of ischemia. Neurosci Lett. 2009;453:182–185. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2009.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou M, Baudry M. EUK-207, a superoxide dismutase/catalase mimetic, is neuroprotective against oxygen/glucose deprivation-induced neuronal death in cultured hippocampal slices. Brain Res. 2009;1247:28–37. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou M, Dominguez R, Baudry M. Superoxide dismutase/catalase mimetics but not MAP kinase inhibitors are neuroprotective against oxygen/glucose deprivation-induced neuronal death in hippocampus. J Neurochem. 2007;103:2212–2223. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04906.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]