Abstract

The prevalence of fluoroquinolone (FQ)-resistant Campylobacter has become a concern for public health. To facilitate the control of FQ-resistant (FQR) Campylobacter, it is necessary to understand the impact of FQR on the fitness of Campylobacter in its natural hosts as understanding fitness will help to determine and predict the persistence of FQR Campylobacter. Previously it was shown that acquisition of resistance to FQ antimicrobials enhanced the in vivo fitness of FQR Campylobacter. In this study, we confirmed the role of the Thr-86-Ile mutation in GyrA in modulating Campylobacter fitness by reverting the mutation to the wild-type (WT) allele, which resulted in the loss of the fitness advantage. Additionally, we determined if the resistance-conferring GyrA mutations alter the enzymatic function of the DNA gyrase. Recombinant WT gyrase and mutant gyrases with three different types of mutations (Thr-86-Ile, Thr-86-Lys, and Asp-90-Asn), which are associated with FQR in Campylobacter, were generated in E. coli and compared for their supercoiling activities using an in vitro assay. The mutant gyrase with the Thr-86-Ile change showed a greatly reduced supercoiling activity compared with the WT gyrase, while other mutant gyrases did not show an altered supercoiling. Furthermore, we measured DNA supercoiling within Campylobacter cells using a reporter plasmid. Consistent with the results from the in vitro supercoiling assay, the FQR mutant carrying the Thr-86-Ile change in GyrA showed much less DNA supercoiling than the WT strain and the mutant strains carrying other mutations. Together, these results indicate that the Thr-86-Ile mutation, which is predominant in clinical FQR Campylobacter, modulates DNA supercoiling homeostasis in FQR Campylobacter.

Keywords: Campylobacter, fluoroquinolone resistance, GyrA mutation, DNA supercoiling, fitness

Introduction

Campylobacter jejuni, a Gram-negative microaerophilic bacterium, has emerged as a leading bacterial cause of foodborne gastroenteritis in the United States and other developed countries (Slutsker et al., 1998). Antibiotic treatment using fluoroquinolone (FQ) or erythromycin is recommended when the infection by Campylobacter is severe or occurs in immunocompromised patients (Engberg et al., 2001; Oldfield Iii and Wallace, 2001). However, Campylobacter is increasingly resistant to FQ antimicrobials, which has become a major concern for public health (Engberg et al., 2001; White et al., 2002; Gupta et al., 2004). As a zoonotic pathogen, C. jejuni is highly prevalent in food producing animals and poultry, and is exposed to antibiotics used in agricultural settings. There has been a concern on the use of FQ antimicrobials in poultry production since the use selectively enriches FQ-resistant (FQR) Campylobacter that can be transmitted to humans via the food chain (Luangtongkum et al., 2009). This concern led to the withdrawal of FQ antimicrobials from poultry production in the U.S. in 2005. Despite the ban, FQR Campylobacter continues to persist on poultry farms (Price et al., 2005, 2007; Luangtongkum et al., 2009), suggesting that FQR Campylobacter does not show a fitness cost in the absence of antibiotic selection pressure.

In Gram-negative bacteria, DNA gyrase, a type II topoisomerase, is the primary target of FQ antibiotics (Hooper, 2001). Once inside bacterial cells, FQ antimicrobials form stable complex with the target enzymes and trap the enzymes on DNA, resulting in double-stranded breaks in DNA, and bacterial death (Willmott et al., 1994; Shea and Hiasa, 1999; Drlica and Malik, 2003). Bacterial DNA gyrase is essential for bacterial viability. It catalyzes ATP-dependent negative supercoiling of DNA and is involved in DNA replication, recombination, and transcription (Champoux, 2001). The enzyme consists of two subunits (subunits A and B) that combine into an A2B2 complex to form a functional enzyme. The two subunits are encoded by gyrA and gyrB, respectively. In Campylobacter, the resistance to FQ antimicrobials is mediated by point mutations in the quinolone resistance-determining region (QRDR) of gyrA in conjunction with the function of the multidrug efflux pump CmeABC (Bachoual et al., 2001; Engberg et al., 2001; Luo et al., 2003; Ge et al., 2005). No mutations in gyrB have been implicated in FQR in Campylobacter (Bachoual et al., 2001; Payot et al., 2002; Piddock et al., 2003). Specific mutations at positions Thr-86, Asp-90, and Ala-70 in GyrA have been linked to FQR in C. jejuni (Wang et al., 1993; Engberg et al., 2001; Luo et al., 2003). The Thr-86-Ile change (mediated by the C257T mutation in the gyrA gene) is the most commonly observed mutation in FQR Campylobacter isolates and confers high-level (ciprofloxacin minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) ≥ 16 μg/ml) resistance to FQ, whereas the Thr-86-Lys and Asp-90-Asn mutations are less common and are associated with intermediate-level FQR (Gootz and Martin, 1991; Wang et al., 1993; Ruiz et al., 1998; Luo et al., 2003).

Resistance-conferring mutations in target genes are often associated with changes in physiological processes, which may result in reduced growth rate and fitness in the absence of antibiotic selection (Andersson and Levin, 1999; Levin et al., 2000; Andersson, 2003; Kugelberg et al., 2005). However, bacteria can develop compensatory mutations to ameliorate the fitness cost associated with antimicrobial resistance (Bjorkman et al., 1998; Bjorkholm et al., 2001; Nagaev et al., 2001; Normark and Normark, 2002; Andersson, 2003). In some cases, antibiotic-resistant mutants show little or no fitness cost even without compensatory mutations (Sander et al., 2002). Previously Luo et al. (2005) showed that FQR Campylobacter carrying the Thr-86-Ile substitution in GyrA subunit was able to outcompete the FQ-susceptible (FQS) strains in the absence of antibiotic usage, suggesting that acquisition of FQR enhances the in vivo fitness of FQR Campylobacter.

DNA supercoiling modulates gene expression and affects bacterial adaptive responses to environmental challenges (Tse-Dinh et al., 1997; Lopez-Garcia, 1999; Prakash et al., 2009). Alteration in DNA supercoiling status may conceivably affect the physiology and fitness of bacterial organisms. Previous work conducted in Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas revealed that antibiotic resistance-conferring mutations in GyrA reduced the supercoiling activity of the enzyme in these organisms (Barnard and Maxwell, 2001; Kugelberg et al., 2005). However, it is unknown if the GyrA mutations conferring FQR in Campylobacter influences the function of GyrA and modulate the DNA supercoiling status within the bacterial cells. In this study, we confirmed the specific role of the Thr-86-Ile mutation in GyrA in influencing Campylobacter fitness in chickens by reverting the mutation to a wild-type (WT) allele. We then evaluated the effects of three different types of GyrA mutations [C257T (Thr-86-Ile), C257A (Thr-86-Lys), and G268A (Asp-90-Asn)] on DNA supercoiling using in vitro and in vivo (within Campylobacter cells) assays. Our results showed that the Thr-86-Ile change in GyrA was directly linked to the fitness change in Campylobacter and greatly reduced the supercoiling activity of GyrA, while other mutations, although reduced the susceptibility of Campylobacter to ciprofloxacin, did not affect the supercoiling activity of DNA gyrase. Together, these results provide new insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying the fitness of the FQR Campylobacter.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial strains and growth conditions

The FQS strains and FQR mutant strains (carrying different point mutations in gyrA) used in this study are listed in Table 1. The strains were routinely grown in Mueller–Hinton (MH) broth (Difco) or agar at 42°C under microaerobic conditions (10% CO2, 5% O2, and 85% N2). Campylobacter-specific growth supplements and selective agents (Oxoid) were added to media when needed to recover Campylobacter from chicken feces. MH media were supplemented with kananmycin (50 μg/ml) or chloramphenicol (4 μg/ml) as needed. E. coli cells were grown at 37°C with shaking at 200 r.p.m. in LB medium which was supplemented with ampicillin (100 μg/ml) or kanamycin (30 μg/ml).

Table 1.

Bacterial strains used in this study.

| Strains | aa mutation in GyrA | nt mutation in gyrA | Description | Source or reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FQS strains | 62301S2 | None | None | Wild-type; isolated from chicken | Luo et al. (2005) |

| 62301R33S | None | None | 62301R33 derivative; 257T in gyrA was reverted to wild-type 257C; Cj1028c: Cmr | This study | |

| NCTC 11168 | None | None | Wild-type; isolated from human | Parkhill et al. (2000a) | |

| 11168 (S) | None | None | NCTC 11168 derivative; Cj1028c: Cmr | This study | |

| FQR strains | 62301R33 | Thr-86-Ile | C257T | Isolated from chicken | Luo et al. (2005) |

| 52901-II 1 | Thr-86-Lys | C257A | Isolated from chicken | Luo et al. (2005) | |

| 62301R37 | Asp-90-Asn | G268A | Isolated from chicken | Luo et al. (2005) | |

| 62301R33R | Thr-86-Ile | C257T | 62301R33 derivative; Cj1028c: Cmr | This study | |

| 11168CT | Thr-86-Ile | C257T | NCTC 11168 derivative; C257T mutation in gyrA | Yan et al. (2006) | |

| 11168 (R) | Thr-86-Ile | C257T | NCTC 11168 derivative; Cj1028c: Cmr and C257T mutation in gyrA | This study |

Reversion of the gyrA mutation (Thr-86-Ile)

To formally define the role of the C257T mutation in influencing Campylobacter fitness, the specific mutation (C257T) in gyrA of isolates 62301R33 was reverted to WT sequence by using a method reported by Ge et al. (2005). Cj1028c and gyrA are tandemly positioned on the chromosome of C. jejuni. An 850-bp fragment containing the 3′ region of Cj1028c, the intergenic region, and the gyrA sequence up to the mutation site was amplified by PCR using C. jejuni 62301R33 as a template and gyrA1028F and gyrA257WR (corresponding to the WT gyrA sequence) as primers (Table 2) and then cloned into a pGEMT-Easy (Promega). The construct was linearized using EcoRV, which cuts once within the cloned cj1028c sequence, ligated with a blunt-ended Cmr cassette, and electroporated into E. coli JM109. Recombinant plasmids were purified from E. coli JM109 and used to transform the parent strains C. jejuni 62301R33 by electroporation. Transformants were selected on MH agar containing chloramphenicol 10 mg/l and analyzed by PCR and DNA sequencing, confirming the insertion of the cat cassette into Cj1028c and the simultaneous replacement of the mutant gyrA with the WT allele. This revertant was named 62301R33S. To make an isogenic pair for the revertant for in vivo competition, the cat gene was also inserted into Cj1028c of isolate 62301R33 without changing the C257T mutation in gyrA. Primers gyrA1028F and gyrA257m(T) were used for this purpose (Table 2). The obtained construct was named 62301R33R. The ciprofloxacin MIC in the revertant 62301R33S was restored to the WT level (0.125 μg/ml), while 62301R33R with the cat gene inserted into Cj1028c retained the ciprofloxacin MIC at 32 μg/ml. Using the same strategy, a point mutation (C257T) in gyrA was introduced into FQS NCTC 11168. The generated FQR mutant strain and its isogenic FQS strain, both of which contained a Cmr insertion in cj1028c, were named 11168 (R) and 11168 (S), respectively (Table 1).

Table 2.

Key PCR primers used in this study.

| Primer name | Sequence (5′–3′) | Target gene/cluster |

|---|---|---|

| gyrA1028F | TGCTCTGCTTTTGTGAATTA | Cj1028c and gyrA (ACA, Thr-86) |

| gyrA257WR | AAACTGCTGTATCTCCATGT | |

| gyrA1028F | TGCTCTGCTTTTGTGAATTA | Cj1028c and gyrA (ATA, Ile-86) |

| gyrA257m (T) | AAACTGCTATATCTCCATGT | |

| gyrA-F-2 | ACATGCATGCGAGAATATTTTTAGCAA | Whole ORF of gyrA |

| gyrA-R | ACGCGTCGACTTATTGCAAATCTAAACC | |

| gyrB-F-J2 | ACATGCATGCCAAGAAAATTACGGTGCG | Whole ORF of gyrB |

| gyrB-R-J | ACGCGTCGACTTACACATCCAAATGCTT | |

| topA-F | GCTGCTTTAAATCCGGACTT | Whole ORF of topA |

| topA-R | CAGCTTCGCAAACATACTCA | |

| cj1686c-F1 | AAGCCAAAGATGCCAAAGAA | topA |

| cj1686c-R1 | TGCGTGGTAAGGTGTTTTCA |

To measure the motility of these constructs, they were grown overnight on fresh MH plates and then were collected from MH plates using MH broth. The optical density at 600 nm (OD600) was adjusted to 0.3. Approximately 1 μl of this suspension was then stabbed into a MH motility plate (MH broth + 0.4% Bacto Agar). Following microaerobic growth at 42°C for approximately 30 h, the radius of growth halo was measured for each strain. The results showed that these FQS and FQR strains were equally motile as determined by the motility assay (data not shown).

In vivo colonization and pairwise competition

The chicken experiments were performed using pairwise competition as described previously (Luo et al., 2005). Three groups (10–11 birds/group) of Campylobacter-free chickens were inoculated with approximately 107 CFU (per bird) of 62301R33S, 62301R33R, or a mixture (approximately 1:1) of the two strains via oral gavage. During the entire experiment, antibiotic-free feed and water were given to the chickens. Thus, antibiotic selection pressure was not involved in the competition. After inoculation, cloacal swabs were collected from the chickens at days 3, 6, and 9 for culturing Campylobacter. Each fecal suspension was serially diluted in MH broth and plated simultaneously onto two different types of culture media: conventional Campylobacter selective plates for recovering the total Campylobacter colonies and the selective MH plates supplemented with 4 μg/ml ciprofloxacin for recovering FQR Campylobacter colonies. To confirm the results from the differential plating, 10–15 Campylobacter colonies were selected randomly for each group from the conventional selective plates (no ciprofloxacin) at each sampling time and tested for ciprofloxacin MICs with E-test strips (AB Biodisk, Solna, Sweden). In the second chicken experiment, the same pairwise experiment was performed using the isogenic pair of 11168(S) and 11168(R). In both experiments, the detection limit of the plating methods was 100 CFU/g of feces. The statistic analyses that were used to determined the significance of differences in the level of colonization between the two groups were performed as described in a previous publication (Han et al., 2008).

All animals were handled in strict accordance with the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health. The animal use protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Iowa State University (A3236-01). All efforts were made to minimize suffering of animals.

Production and purification of GyrA and GyrB

Full-length histidine (His)-tagged recombinant gyrases including WT GyrA, three mutant GyrAs, and GyrB were produced in E. coli by using the pQE-30 vector of the QIAexpress expression system (Qiagen), which allows the tagging of a recombinant protein with 6× His at the N-terminus. The complete coding sequences of gyrA in strains 62301S2 (no mutation in GyrA), 62301R33 (with the Thr-86-Ile change in GyrA), 52901-II2 (with the Thr-86-Lys change in GyrA), and 62301R37 (with the Asp-90-Asn change in GyrA) were amplified using primers gyrA-F-2 and gyrA-R. The complete coding sequence of gyrB in strain 62301S2 was amplified using primers gyrB-F-J2 and gyrB-R-J. A restriction site (underlined in the primer sequences) was attached to the 5′ end of each primer to facilitate the directional cloning of the amplified PCR product into the pQE-30 vector. The amplified PCR product was digested with SphI and SalI, and then ligated into the pQE-30 vector, which was previously digested with the same enzymes. Each plasmid in the E. coli clone expressing a recombinant peptide was sequenced, revealing no undesired mutations in the coding sequence. These N-terminal His-tagged recombinant GyrA and GyrB proteins were expressed and purified to near-homogeneity under native conditions by following the procedure supplied with the pQE-30 vector. Then these proteins were analyzed by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). To remove imidazole, the purified proteins were washed extensively with 10 mM Tris–HCl using Centricon YM-50 (Millipore).

In vitro supercoiling assay

DNA supercoiling activity was assayed by monitoring the conversion of relaxed pBR322 to its supercoiled form. WT or mutant GyrA was mixed with WT GyrB in a ratio of 1:1. Each supercoiling reaction contained 500 ng of relaxed pBR322 DNA (TopoGEN, Inc.) and 300 μM gyrases in 1× assay buffer (TopoGEN, Inc.). The reaction mixtures were incubated at 37°C for 1 h. Assays were terminated by the addition of 0.2 volume of the stop buffer (TopoGEN) and 1 volume of chloroform–isoamyl alcohol (24:1). The reactions were analyzed on 1.0% agarose gels. The gels were stained with ethidium bromide for 30 min and then destained in 1× TAE buffer for 1 h.

MEC determinations

To determine the susceptibility of various gyrases to the inhibitory effect of ciprofloxacin, the in vitro supercoiling assay using recombinant gyrases was also performed with added ciprofloxacin as descried previously (Martin, 1991). Ciprofloxacin was added into each reaction prior to the addition of DNA gyrases. The minimum effective concentration (MEC) was defined as the lowest concentration of ciprofloxacin that shows an observable inhibition on supercoiling of the plasmid DNA.

Examination of in vivo supercoiling

To determine if the mutations in GyrA changed the DNA supercoiling in Campylobacter cells, the shuttle plasmid pRY107 was used as a reporter to monitor the relative difference in the levels of DNA supercoiling between the FQS and FQR strains. pRY107, which carries a kanamycin resistance marker (Yao et al., 1993), was transferred into 62301S2, 62301R33, 52901-II2, 62301R37, 11168, and 1168CT by conjugation. Plasmid DNA was then isolated using QIAGEN Plasmid Midi kit (Qiagen Inc.) and analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis in the absence or presence of chloroquine diphosphate salt, as described previously (Mizushima et al., 1997; Kugelberg et al., 2005). Agarose gels (1%) were run for 20 h at 2 V/cm in 1× TAE buffer containing 20 μg/ml of chloroquine and were washed for 4 h in distilled water before staining with ethidium bromide. The topoisomers of the plasmid DNA from each strain were visualized using a digital imaging system (Alpha Innotech). The relative amounts of supercoiled vs. relaxed DNA in each sample reflecting the level of DNA supercoiling in each strain were determined by densitometry scanning and were used to indicate the difference in DNA supercoiling between the FQS and FQR strains.

Sequence determination of topA

The entire topA gene from C. jejuni 62301S2 and 62301R33 were amplified by PCR with the forward primer topA-F and reverse primer topA-R. The forward primer is 286 bp upstream of the AUG start codon, and the reverse primer extends 239 bp beyond the UAG stop codon of topA. The PCR was performed in a volume of 50 μl containing 100 μM each deoxynucleoside triphosphate (dNTP), 200 nM primers, 2.5 mM MgSO4, 100 ng of Campylobacter genomic DNA, and 5 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Promega). The cycling conditions consisted of an initial polymerase activation step at 94°C for 5 min, followed by 35 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 3 min, with a final extension at 72°C for 10 min. The amplified PCR products were purified with the QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen) and subsequently sequenced.

Real-time quantitative RT-PCR

The transcription of topA in 62301S2 and 62301R33 was compared by qRT-PCR. The primers used for qRT-PCR are listed in Table 2 and the method was performed as described in a previous work (Lin et al., 2005).

Antibiotic susceptibility test

The MIC of ciprofloxacin was determined by using E-test strips (AB Biodisk, Solna, Sweden) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The detection limit of the E-test for ciprofloxacin was 32 μg/ml.

Results

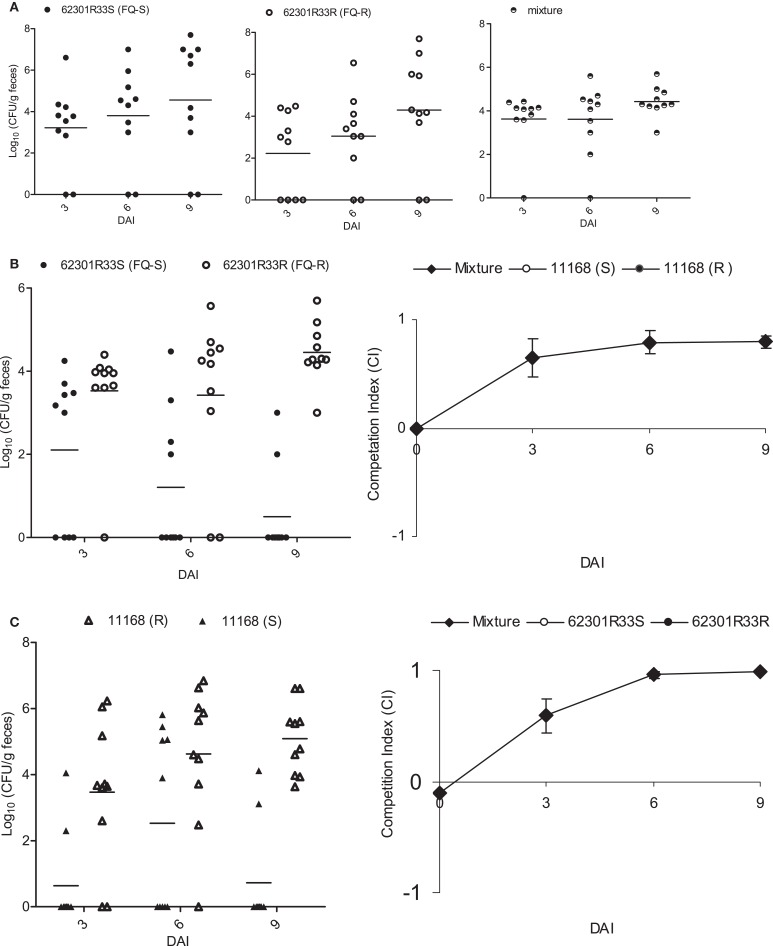

Direct role of the Thr-86-Ile change in the enhanced fitness

A previous study by Luo et al. (2005) showed that FQR Campylobacter carrying the Thr-86-Ile substitution GyrA outcompeted its isogenic FQS strains in chickens, suggesting that acquisition of FQR enhances the in vivo fitness of FQR Campylobacter. The previous work was done using FQR mutants generated from antibiotic selection or natural transformation. To further confirm the link of this specific mutation with the enhanced fitness, we reverted the mutation back to the WT allele and conducted pairwise competition in chickens using 62301R33S and 62301R33R (Table 1). After inoculation with either of the two isolates or mixed populations, all of the groups of birds were colonized by Campylobacter at similar levels (Figure 1A). When separately inoculated into chickens, the two strains showed no significant differences (P > 0.05) in the level of colonization (the number of Campylobacter shed in feces; Figure 1A). Differential plating by using ciprofloxacin-containing plates showed that the group inoculated with the FQS revertant alone shed homogeneous FQS Campylobacter, whereas the group inoculated with FQR strain shed homogeneous FQR Campylobacter during the entire course of the experiment. However, in the group inoculated with mixtures of the two strains, the FQS revertant strain was outcompeted by its parent FQR Campylobacter (P < 0.05; Figure 1B). E-test of Campylobacter colonies (10∼15 colonies per group per time point) randomly selected from non-antibiotic plates confirmed the results of differential plating. This result clearly indicates that once the C257T mutation in gyrA is reverted, Campylobacter loses its fitness advantage in chickens, confirming the previous results using clonally related and isogenic strains (Luo et al., 2005). To further show the specific effect of the C257T mutation on fitness, we introduced this mutation into a different strain background (NCTC 11168) and conducted chicken competition using the isogenic pair of constructs. As shown in Figure 1C, 11168(S) was outcompeted by 11168(R) (P < 0.05), indicating the mutation had the same impact on fitness in a C. jejuni strain different from the previously tested ones. These new findings plus our previously published studies (Luo et al., 2005) convincingly showed that the C257T mutation in gyrA is directly responsible for the enhanced fitness of Campylobacter in chickens.

Figure 1.

Pairwise competitions between FQS and FQR strains in chickens using isogenic pairs of 62301R33S/62301R33R (A,B) and 11168(S)/11168(R) (C). (A) The colonization level of total Campylobacter in three groups of chickens that were inoculated with 62301R33S (solid circle), 62301R33R (open circle), or 1:1 mixture of the two stains. (B) Differential enumeration of FQS (solid circle) and FQR (open circle) Campylobacter in the group inoculated with a mixture of 62301R33S and 62301R33R. (C) A second chicken experiment shows the competition between FQS (solid triangle) and FQR (open triangle) Campylobacter in a different strain background. The chickens were inoculated with a 1:1 mixture of 11168(S) and 11168(R). In all panels, each symbol represents the colonization level of a single chicken and the median level of each group is indicated by a horizontal bar. The detection limit of the plating method was about 100 CFU/g of feces and a negative sample was arbitrarily assigned a value of zero. DAI, days after inoculation.

No compensatory mutations in topA

Campylobacter jejuni has only two types of topoisomerases, type I (TopA) and type II (gyrase). The gyrase introduces negative supercoiling to DNA, while TopA relaxes DNA to prevent excessive supercoiling. Thus, the two enzymes are the key proteins modulating the level of DNA supercoiling in Campylobacter. To determine if there were any mutations in TopA that might potentially offset the impact of the Thr-86-Ile mutation in GyrA, we sequenced topA and compared its transcription between isogenic strains. The whole ORF of topA was PCR amplified from 62301R33 and sequenced, which showed that the topA sequence was identical to that in 62301S2. In addition, the expression level of topA was not different in 62301R33 and 62301S2 as determined by qRT-PCR (data not shown). These results suggest that the Thr-86-Ile mutation in GyrA was not accompanied by changes in topA sequence or expression.

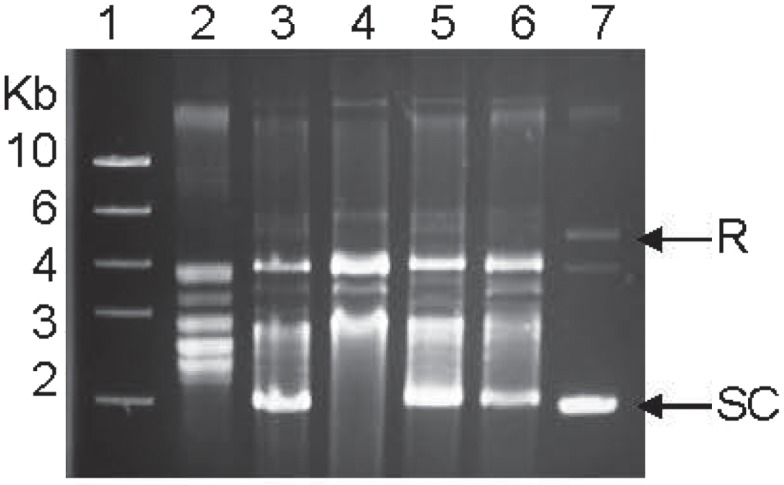

Effect of GyrA mutations on in vitro supercoiling

To determine the impact of the resistance-conferring mutations on the enzymatic activities of GyrA, we produced the recombinant forms of various gyrases. As estimated by SDS-PAGE, the recombinant GyrA and GyrB were 97 and 87 kDa, respectively, comparable with the calculated molecular masses of the two proteins. The recombinant GyrA carrying a Thr-86-Ile, Thr-86-Lys, or Asp-90-Asn mutation migrated at a position similar to the recombinant GyrA of the WT strain on SDS-PAGE (data not shown), indicating that the point mutations did not affect the migration of GyrA on SDS-PAGE. The supercoiling activity of the recombinant DNA gyrases from the WT and mutant strains was analyzed by an in vitro assay. Both GyrA and GyrB are required for producing negative supercoiling and no detectable supercoiling activity was observed when only one subunit (either GyrA or GyrB) was used in the assay (data not shown). The recombinant GyrA from mutant strains carrying the Thr-86-Lys or Asp-90-Asn mutation exhibited a supercoiling activity similar to that of the recombinant GyrA from the WT strain, whereas the negative supercoiling activity of the GyrA from the mutant strain carrying the Thr-86-Ile change was substantially reduced compared with the GyrA from the WT strain (Figure 2). In fact, the most supercoiled band was absent with this mutant GyrA (Figure 2). The results were consistently shown in multiple experiments with different concentrations of gyrases (up to 1200 nM; data not shown) and indicate that the Thr-86-Ile mutation, but not other mutations, alters the negative supercoiling activity of GyrA.

Figure 2.

Supercoiling activities of the recombinant WT gyrase and the three recombinant mutant gyrases measured by an in vitro assay. Lane 1, DNA ladder; Lane 2, relaxed pBR322 (control); Lane 3, WT GyrA + GyrB; Lane 4, mutant GyrA (Thr-86-Ile) + GryB; Lane 5, mutant GyrA (Thr-86-Lys) + GryB; Lane 6, mutant GyrA (Asp-90-Asn) + GryB; and Lane 7, supercoiled pBR322 (control). SC indicates supercoiled DNA and R represents relaxed DNA.

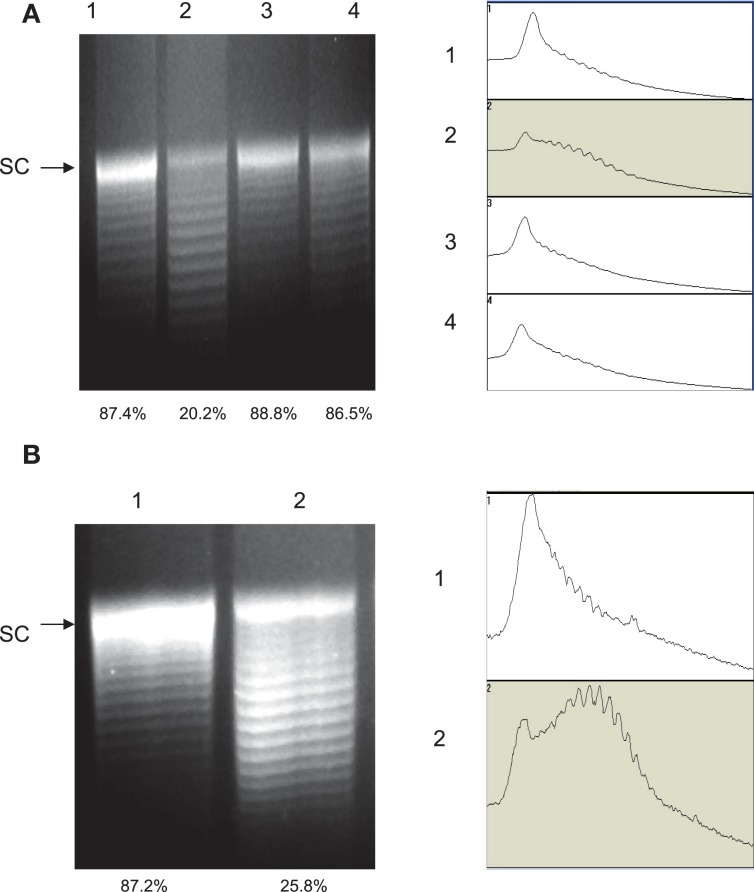

Effect of the GyrA mutations on in vivo supercoiling

The recombinant GyrA carrying the Thr-86-Ile mutation showed reduced supercoiling activity in vitro, but it is important to determine if the same mutation also affects DNA supercoiling in vivo (in Campylobacter cells). For this purpose, we used pRY107, a shuttle plasmid, as a reporter plasmid to monitor the relative levels of DNA supercoiling in the FQS and FQR strains. Plasmid pRY107 was transferred into 62301S2 (WT strain), 62301R33 (carrying the Thr-86-Ile mutation in GyrA), 52901-II2 (carrying the Thr-86-Lys mutation in GyrA), and 62301R37 (carrying the Asp-90-Asn mutation), which were clonally related and all derived from strain S3B (Luo et al., 2005). Plasmid DNA was re-isolated from these constructs and analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis in the presence of chloroquine. Under the condition utilized in this study (20 μg/ml chloroquine), negatively supercoiled forms of pRY107 migrated slower than relaxed topoisomers. This pattern of migration was confirmed by using commercially available plasmid pBR322 (supercoiled and relaxed; data not shown). Compared to the pRY107 from 62301S2, the plasmid topoisomers from 62301R33 harboring the Thr-86-Ile mutation in GyrA shifted to lower positions, indicating less supercoiling (Figure 3A). As determined by densitometrical analysis, the percentage of the most supercoiled DNA in the total population of the plasmid topoisomers extracted from 62301S2 and 62301R33 was 87.4 and 20.2%, respectively. The plasmids from 52901-II2 and 62301R37 showed topoisomer distribution patterns similar to that of 62301S2 (Figure 3A). These results indicate that the GyrA mutant with the Thr-86-Ile mutation reduced DNA supercoiling in Campylobacter cells, while the mutants with the Thr-86-Lys or Asp-90-Asn changes in GyrA did not alter DNA supercoiling. To further confirm the impact of the Thr-86-Ile change on DNA supercoiling, we introduced pRY107 to a different strain background, NCTC 11168 and 11168CT. The only known difference between this pair of isolates is the C257T mutation in gyrA (Table 1). Similar to the result from 62301R33, the plasmid topoisomers from 11168CT shifted to lower positions compared with NCTC 11168 (Figure 3B), indicating reduced negative supercoiling. The in vivo supercoiling results were consistent with the findings from the in vitro supercoiling assay and demonstrated that the Thr-86-Ile mutation in GyrA reduced DNA supercoiling in Campylobacter.

Figure 3.

Agarose gel electrophoresis analysis of plasmid topoisomers extracted from different strain background. The plasmid DNA was run on a 1.0% agarose gel containing 20 μg/ml chloroquine. (A) Plasmid pRY107 isolated from strain S3B derivatives. Lane 1, pRY107 from 62301S; Lane 2, pRY107 from 62301R (carrying the Thr-86-Ile mutation in GyrA); Lane 3, pRY107 from 52901-II2 (carrying the Thr-86-Lys mutation in GyrA); and Lane 4, pRY107 from 62301R37 (carrying the Asp-90-Asn mutation in GyrA). (B) Plasmid pRY107 isolated from strain 11168 and its derivatives. Lane 1, pRY107 from NCTC 11168; and Lane 2, pRY107 from 11168CT (carrying the Thr-86-Ile mutation in GyrA). The results of densitometric scanning are shown to the right of each gel image. The numbers on the left of the densitometric scanning correspond to the lane numbers of the gel image. The number below each lane indicates the percentage of the most supercoiled DNA in the total population of plasmid topoisomers as measured by densitometry.

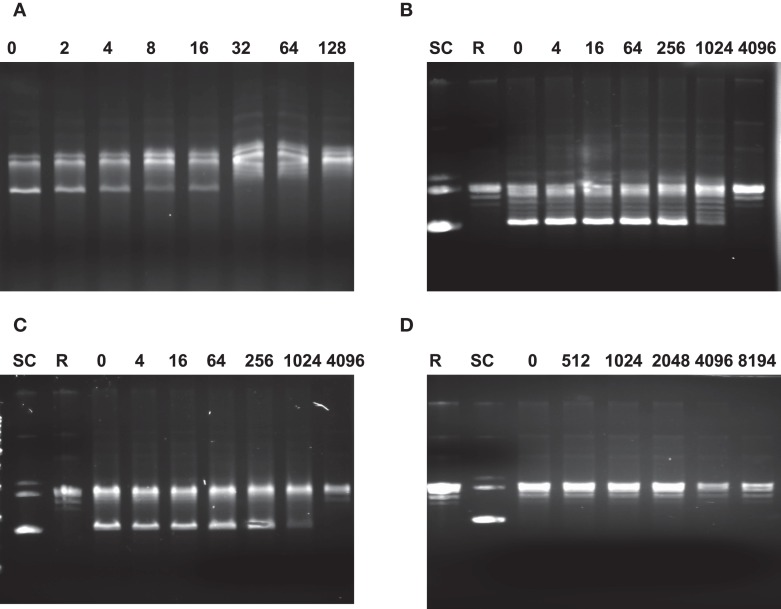

GyrA mutations reduce the susceptibility to ciprofloxacin

The GyrA mutations confer resistance to FQ antimicrobials and it is likely that the resistance is due to the reduced susceptibility of the mutant gyrases to the antibiotics. This possibility was determined using the in vitro supercoiling assay. As shown in Figure 4, the MEC of ciprofloxacin to the recombinant WT GyrA is 32, while the MEC of the two recombinant mutant gyrases carrying the Thr-86-Lys or Asp-90-Asn mutations were 1024, indicating that the two mutations significantly reduced the susceptibility of GyrA to the inhibition by ciprofloxacin. With the mutant GyrA carrying the Thr-86-Ile change, the inhibitory effect of ciprofloxacin was not measurable because the mutation itself abolished the ability of the enzyme to form the supercoiled band in the in vitro assay (Figure 4). These findings suggest that the resistance-conferring mutations in GyrA desensitize the inhibitory effect of ciprofloxacin and provide a molecular basis for the reduced susceptibility of FQR mutants to ciprofloxacin.

Figure 4.

Agarose gel electrophoresis showing the inhibition of DNA gyrase supercoiling activities by ciprofloxacin. In each reaction, the relaxed pBR322 was incubated with different enzymes in the presence of various concentration of ciprofloxacin. (A) Reactions with recombinant GyrA from the WT strain and GyrB; (B) reactions with mutant GyrA (Thr-86-Lys) and GyrB; (C) reactions with mutant GyrA (Asp-90-Asn) and GyrB; and (D) reactions with mutant GyrA (Thr-86-Ile) + GyrB. The numbers on top of each panel are the concentrations of ciprofloxacin (μg/ml) used in the reaction. SC indicates supercoiled DNA and R represents relaxed DNA (TopoGen). In each lane, the most supercoiled band migrates faster than the other topoisomers.

Discussion

Several reports have documented the variable fitness changes associated with topoisomerase mutations in bacteria (Bagel et al., 1999; Gillespie et al., 2002; Giraud et al., 2003; Ince and Hooper, 2003; Kugelberg et al., 2005). In S. typhimurium, the FQR mutants selected by in vitro plating were highly resistant to FQs, but grew significantly slow in culture media, and failed to colonize chickens (Giraud et al., 2003). On the contrary, the in vivo selected FQR Salmonella isolates exhibited intermediate susceptibility to FQs, had normal growth in liquid medium, and were able to colonize chickens as efficiently as or lower than that of the WT strains (Giraud et al., 2003; Zhang et al., 2006). In the case with FQR E. coli, single mutations in DNA gyrase or topoisomerase IV conferred a low-level resistance to FQs and did not incur a significant fitness cost, while accumulation of multiple mutations in the enzymes resulted in a high-level resistance and a significant fitness disadvantage (Bagel et al., 1999; Komp Lindgren et al., 2005; Morgan-Linnell and Zechiedrich, 2007). A recent study using isogenic constructs further demonstrated the variable effects of single and multiple GyrA mutation on the fitness of E. coli (Marcusson et al., 2009). Thus, depending on the types of mutations, bacterial organisms, and the environment in which fitness is measured, FQR-conferring GyrA mutations either have no effects on bacterial fitness or incur a fitness cost.

In contrast to the findings in other bacteria, Luo et al. (2005) using clonally related isolates and isogenic transformants showed that FQR Campylobacter outcompeted FQS strains in chickens in the absence of FQ antimicrobials and the enhanced fitness was linked to the single point mutation (Thr-86-Ile) in gyrA, which confers on Campylobacter a high-level resistance to FQ antimicrobials. To exclude the possible involvement of compensatory mutation and further confirm the specific role of this resistance-conferring mutation in the enhanced fitness, we constructed a revertant of FQR Campylobacter, in which the C257T change was reverted. The in vivo results showed that once the Thr-86-Ile mutation in GyrA of 62301R33 was reverted, Campylobacter lost its fitness advantage in chickens (Figure 1), confirming the specific effect of the point mutation on Campylobacter fitness. In addition, introducing the Thr-86-Ile mutation into the GyrA of C. jejuni NCTC11168, which is a different strain and divergent from the S3B derivatives used in the previous work (Luo et al., 2005), also enhanced its fitness in chickens. These new results along with the previous findings conclusively establish that the Thr-86-Ile mutation in GyrA modulates fitness of C. jejuni in chickens.

Previously it was shown in other bacteria that antibiotic resistance-conferring mutations in GyrA affected the supercoiling activity of GyrA (Barnard and Maxwell, 2001; Kugelberg et al., 2005). For example, Barnard and Maxwell (2001) showed that FQR E. coli mutant carrying a single (Ala87) or double mutations (Ala83 Ala87) in GyrA exhibited reduced supercoiling compared to that of the WT strain. In Pseudomonas aeruginosa, it was also shown that FQR GyrA Ile83 mutant and Tyr87 mutant had decreased supercoiling, which was associated with reduced growth rate (Kugelberg et al., 2005). In this study, we demonstrated that in Campylobacter the recombinant GyrA with the Thr-86-Ile change showed a greatly reduced supercoiling activity compared with that of the WT enzyme (Figure 2). The mutation also reduced DNA supercoiling in Campylobacter cells (Figure 3). The results from the in vitro and in vivo supercoiling assays are consistent and indicate that acquisition of the Thr-86-Ile mutation in GyrA impacts DNA supercoiling homeostasis within Campylobacter. In contrast, the supercoiling activity of the mutant gyrases harboring the Thr-86-Lys or the Asp-90-Asn mutation was comparable to that of the WT gyrase (Figure 2), suggesting that these two types of mutations do not affect the physiological function of the enzyme.

Interestingly, the Thr-86-Ile and Thr-86-Lys mutations occurred at the same place, but had a different impact on the enzyme function. This is probably due to the fact that Thr and Lys are both hydrophilic amino acids, while Ile is a hydrophobic residue. Thus the Thr-86-Ile change would conceivably more disruptive than the Thr-86-Lys mutation to the function of GyrA. In Campylobacter GyrA, Thr-86 is equivalent to Ser-83 in E. coli GyrA (Wang et al., 1993). It has been known that Ser-83 is located in the QRDR and Ser-83 is involved in the interaction of gyrase–quinolone–DNA complex (Barnard and Maxwell, 2001). Thus changes in the QRDR of GyrA in Campylobacter likely prevent FQ binding, producing resistance to FQ antimicrobials. Indeed, we demonstrated that the mutant gyrases carrying the Thr-86-Lys or the Asp-90-Asn mutation had significantly higher MECs of ciprofloxacin than the WT GyrA (Figure 4.), indicating that the mutant gyrases are more resistant to the inhibition by ciprofloxacin. Interestingly, the MECs of ciprofloxacin with the enzymes were significantly (at least 250 times) higher than the MICs of ciprofloxacin in these strains. This finding was consistent with the results from other studies (Gootz and Martin, 1991; Martinez et al., 2006) in which MECs and MICs were found to differ by one or two orders of magnitude. Due to the lack of supercoiling activity in the absence of ciprofloxacin, the MEC of the mutant gyrase with the Thr-86-Ile mutation was not measurable using the in vitro supercoiling assay (Figure 4). However, the MEC of this mutant gyrase is expected to be much higher than those of the other two mutant gyrase as the mutation Thr-86-Ile produces a higher level of FQR than the other types of mutations. These findings provide a molecular explanation for the resistance FQ antimicrobials in Campylobacter.

In Campylobacter, the genes encoding topoisomerase IV (parC/parE) are absent (Parkhill et al., 2000b), and the supercoiling homeostasis is controlled by topoisomerase I (TopA) and topoisomerase II (GyrA and GyrB). Our previous study has shown that the FQR isolates had no compensatory mutations in GyrA and GyrB (Luo et al., 2005). Since topoisomerase I, encoded by topA, is involved in the relaxation of DNA supercoiling and also plays an important role in maintaining the topological state of DNA, it is necessary to determine if there are any compensatory mutations in topA and whether the expression of the topA is changed in FQR Campylobacter. Our results showed that the coding sequence of topA was identical between strains 62301S2 and 62301R33 and there was no difference in the expression of topA between these two strains, which excluded the possibility that mutations or altered expression of topA contributed to the fitness change in FQR Campylobacter.

In conclusion, the present study shows that the Thr-86-Ile mutation in GyrA is directly linked to the enhanced fitness of FQR Campylobacter and no compensatory mutations in topA are associated with this fitness change. The Thr-86-Ile mutation, not other types of mutations, reduces the supercoiling activity of GyrA and modulates DNA supercoiling homeostasis in Campylobacter. Given that DNA supercoiling is important for gene expression in bacteria (Dorman and Corcoran, 2009; Booker et al., 2010), it is tempting to speculate that the altered DNA supercoiling might be linked to the fitness change in FQR Campylobacter. This possibility awaits further investigation in future studies. Findings from this study provide new insights into the molecular mechanisms associated with the enhanced fitness in FQR Campylobacter, which continue to persist in the absence of antibiotic selection pressure.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This study is supported by grant 2007-35201-18278 from the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture and grant RO1DK063008 from the National Institute of Health.

References

- Andersson D. I. (2003). Persistence of antibiotic resistant bacteria. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 6, 452–456 10.1016/j.mib.2003.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson D. I., Levin B. R. (1999). The biological cost of antibiotic resistance. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2, 489–493 10.1016/S1369-5274(99)80003-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachoual R., Ouabdesselam S., Mory F., Lascols C., Soussy C. J., Tankovic J. (2001). Single or double mutational alterations of gyrA associated with fluoro-quinolone resistance in Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli. Microb. Drug Resist. 7, 257–261 10.1089/10766290152652800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagel S., Hullen V., Wiedemann B., Heisig P. (1999). Impact of gyrA and parC mutations on quinolone resistance, doubling time, and supercoiling degree of Escherichia coli. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43, 868–875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnard F. M., Maxwell A. (2001). Interaction between DNA gyrase and quinolones: effects of alanine mutations at GyrA subunit residues Ser83 and Asp87. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45, 1994–2000 10.1128/AAC.45.7.1994-2000.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjorkholm B., Sjolund M., Falk P. G., Berg O. G., Engstrand L., Andersson D. I. (2001). Mutation frequency and biological cost of antibiotic resistance in Helicobacter pylori. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 14607–14612 10.1073/pnas.241517298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjorkman J., Hughes D., Andersson D. I. (1998). Virulence of antibiotic-resistant Salmonella typhimurium. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 3949–3953 10.1073/pnas.95.7.3949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booker B. M., Deng S., Higgins N. P. (2010). DNA topology of highly transcribed operons in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Mol. Microbiol. 78, 1348–1364 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07394.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champoux J. J. (2001). DNA topoisomerases: structure, function, and mechanism. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 70, 369–413 10.1146/annurev.biochem.70.1.369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorman C. J., Corcoran C. P. (2009). Bacterial DNA topology and infectious disease. Nucleic Acids Res. 37, 672–678 10.1093/nar/gkn996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drlica K., Malik M. (2003). Fluoroquinolones: action and resistance. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 3, 249–282 10.2174/1568026033452537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engberg J., Aarestrup F. M., Taylor D. E., Gerner-Smidt P., Nachamkin I. (2001). Quinolone and macrolide resistance in Campylobacter jejuni and C. coli: resistance mechanisms and trends in human isolates. Emerging Infect. Dis. 7, 24–34 10.3201/eid0701.010104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge B., Mcdermott P. F., White D. G., Meng J. (2005). Role of efflux pumps and topoisomerase mutations in fluoroquinolone resistance in Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49, 3347–3354 10.1128/AAC.49.8.3347-3354.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie S. H., Voelker L. L., Dickens A. (2002). Evolutionary barriers to quinolone resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Microb. Drug Resist. 8, 79–84 10.1089/107662902760190617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giraud E., Cloeckaert A., Baucheron S., Mouline C., Chaslus-Dancla E. (2003). Fitness cost of fluoroquinolone resistancein Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. J. Med. Microbiol. 52, 697–703 10.1099/jmm.0.05178-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gootz T. D., Martin B. A. (1991). Characterization of high-level quinolone resistance in Campylobacter jejuni. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 35, 840–845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta A., Nelson J. M., Barrett T. J., Tauxe R. V., Rossiter S. P., Friedman C. R., Joyce K. W., Smith K. E., Jones T. F., Hawkins M. A., Shiferaw B., Beebe J. L., Vugia D. J., Rabatsky-Ehr T., Benson J. A., Root T. P., Angulo F. J. (2004). Antimicrobial resistance among Campylobacter strains, United States, 1997-2001. Emerging Infect. Dis. 10, 1102–1109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han J., Sahin O., Barton Y. W., Zhang Q. (2008). Key role of Mfd in the development of fluoroquinolone resistance in Campylobacter jejuni. PLoS Pathog. 4, e1000083. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooper D. C. (2001). Emerging mechanisms of fluoroquinolone resistance. Emerging Infect. Dis. 7, 337–341 10.3201/eid0702.010239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ince D., Hooper D. C. (2003). Quinolone resistance due to reduced target enzyme expression. J. Bacteriol. 185, 6883–6892 10.1128/JB.185.23.6883-6892.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komp Lindgren P., Marcusson L. L., Sandvang D., Frimodt-Moller N., Hughes D. (2005). Biological cost of single and multiple norfloxacin resistance mutations in Escherichia coli implicated in urinary tract infections. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49, 2343–2351 10.1128/AAC.49.6.2343-2351.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kugelberg E., Lofmark S., Wretlind B., Andersson D. I. (2005). Reduction of the fitness burden of quinolone resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 55, 22–30 10.1093/jac/dkh505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin B. R., Perrot V., Walker N. (2000). Compensatory mutations, antibiotic resistance and the population genetics of adaptive evolution in bacteria. Genetics 154, 985–997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin J., Cagliero C., Guo B., Barton Y.-W., Maurel M.-C., Payot S., Zhang Q. (2005). Bile salts modulate expression of the CmeABC multidrug efflux pump in Campylobacter jejuni. J. Bacteriol. 187, 7417–7424 10.1128/JB.187.23.7881-7889.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Garcia P. (1999). DNA supercoiling and temperature adaptation: a clue to early diversification of life? J. Mol. Evol. 49, 439–452 10.1007/PL00006567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luangtongkum T., Jeon B., Han J., Plummer P., Logue C. M., Zhang Q. (2009). Antibiotic resistance in Campylobacter: emergence, transmission and persistence. Future Microbiol. 4, 189–200 10.2217/17460913.4.2.189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo N., Pereira S., Sahin O., Lin J., Huang S., Michel L., Zhang Q. (2005). Enhanced in vivo fitness of fluoroquinolone-resistant Campylobacter jejuni in the absence of antibiotic selection pressure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 541–546 10.1073/pnas.0502440102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo N., Sahin O., Lin J., Michel L. O., Zhang Q. (2003). In vivo selection of Campylobacter isolates with high levels of fluoroquinolone resistance associated with gyrA mutations and the function of the CmeABC efflux pump. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47, 390–394 10.1128/AAC.47.1.390-394.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcusson L. L., Frimodt-Moller N., Hughes D. (2009). Interplay in the selection of fluoroquinolone resistance and bacterial fitness. PLoS Pathog. 5, e1000541. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin T. D. G. A. B. A. (1991). Characterization of high-level quinolone resistance in Campylobacter jejuni. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 35, 840–845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez M., Mcdermott P., Walker R. (2006). Pharmacology of the fluoroquinolones: a perspective for the use in domestic animals. Vet. J. 172, 10–28 10.1016/j.tvjl.2005.07.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizushima T., Kataoka K., Ogata Y., Inoue R., Sekimizu K. (1997). Increase in negative supercoiling of plasmid DNA in Escherichia coli exposed to cold shock. Mol. Microbiol. 23, 381–386 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.2181582.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan-Linnell S. K., Zechiedrich L. (2007). Contributions of the combined effects of topoisomerase mutations toward fluoroquinolone resistance in Escherichia coli. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51, 4205–4208 10.1128/AAC.00647-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagaev I., Bjorkman J., Andersson D. I., Hughes D. (2001). Biological cost and compensatory evolution in fusidic acid-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Mol. Microbiol. 40, 433–439 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02389.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Normark B. H., Normark S. (2002). Evolution and spread of antibiotic resistance. J. Intern. Med. 252, 91–106 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2002.01026.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldfield Iii E. C., Wallace M. R. (2001). The role of antibiotics in the treatment of infectious diarrhea. Gastroenterol. Clin. North Am. 30, 817–835 10.1016/S0889-8553(05)70212-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkhill J., Wren B. W., Mungall K., Ketley J. M., Churcher C., Basham D., Chillingworth T., Davies R. M., Feltwell T., Holroyd S., Jagels K., Karlyshev A. V., Moule S., Pallen M. J., Penn C. W., Quail M. A., Rajandream M. A., Rutherford K. M., Van Vliet A. H., Whitehead S., Barrell B. G. (2000a). The genome sequence of the food-borne pathogen Campylobacter jejuni reveals hypervariable sequences. Nature 403, 665–668 10.1038/35001088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkhill J., Wren B. W., Mungall K., Ketley J. M., Churcher C., Basham D., Chillingworth T., Davies R. M., Feltwell T., Holroyd S., Jagels K., Karlyshev A. V., Moule S., Pallen M. J., Penn C. W., Quail M. A., Rajandream M. A., Rutherford K. M., Van Vliet A. H. M., Whitehead S., Barrell B. G. (2000b). The genome sequence of the food-borne pathogen Campylobacter jejuni reveals hypervariable sequences. Nature 403, 665–668 10.1038/35001088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payot S., Cloeckaert A., Chaslus-Dancla E. (2002). Selection and characterization of fluoroquinolone-resistant mutants of Campylobacter jejuni using enrofloxacin. Microb. Drug Resist. 8, 335–343 10.1089/10766290260469606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piddock L. J., Ricci V., Pumbwe L., Everett M. J., Griggs D. J. (2003). Fluoroquinolone resistance in Campylobacter species from man and animals: detection of mutations in topoisomerase genes. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 51, 19–26 10.1093/jac/dkg033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prakash J. S., Sinetova M., Zorina A., Kupriyanova E., Suzuki I., Murata N., Los D. A. (2009). DNA supercoiling regulates the stress-inducible expression of genes in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis. Mol. Biosyst. 5, 1904–1912 10.1039/b903022k [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price L. B., Johnson E., Vailes R., Silbergeld E. (2005). Fluoroquinolone-resistant Campylobacter isolates from conventional and antibiotic-free chicken products. Environ. Health Perspect. 113, 557–560 10.1289/ehp.7647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price L. B., Lackey L. G., Vailes R., Silbergeld E. (2007). The persistence of fluoroquinolone-resistant Campylobacter in poultry production. Environ. Health Perspect. 115, 1035–1039 10.1289/ehp.10050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz J., Goni P., Marco F., Gallardo F., Mirelis B., Jimenez De Anta T., Vila J. (1998). Increased resistance to quinolones in Campylobacter jejuni: a genetic analysis of gyrA gene mutations in quinolone-resistant clinical isolates. Microbiol. Immunol. 42, 223–226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sander P., Springer B., Prammananan T., Sturmfels A., Kappler M., Pletschette M., Bottger E. C. (2002). Fitness cost of chromosomal drug resistance-conferring mutations. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46, 1204–1211 10.1128/AAC.46.5.1204-1211.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shea M. E., Hiasa H. (1999). Interactions between DNA helicases and frozen topoisomerase IV-quinolone-DNA ternary complexes. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 22747–22754 10.1074/jbc.274.32.22747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slutsker L., Altekruse S. F., Swerdlow D. L. (1998). Foodborne diseases. Emerging pathogens and trends. Infect. Dis. Clin. North Am. 12, 199–216 10.1016/S0891-5520(05)70418-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tse-Dinh Y. C., Qi H., Menzel R. (1997). DNA supercoiling and bacterial adaptation: thermotolerance and thermoresistance. Trends Microbiol. 5, 323–326 10.1016/S0966-842X(97)01080-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Huang W. M., Taylor D. E. (1993). Cloning and nucleotide sequence of the Campylobacter jejuni gyrA gene and characterization of quinolone resistance mutations. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 37, 457–463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White D. G., Zhao S., Simjee S., Wagner D. D., Mcdermott P. F. (2002). Antimicrobial resistance of foodborne pathogens. Microbes Infect. 4, 405–412 10.1016/S1286-4579(02)01554-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willmott C. J. R., Critchlow S. E., Eperon I. C., Maxwell A. (1994). The complex of DNA gyrase and quinolone drugs with DNA forms a barrier to transcription by RNA polymerase. J. Mol. Biol. 242, 351–363 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan M., Sahin O., Lin J., Zhang Q. (2006). Role of the CmeABC efflux pump in the emergence of fluoroquinolone-resistant Campylobacter under selection pressure. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 58, 1154–1159 10.1093/jac/dkl266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao R., Alm R. A., Trust T. J., Guerry P. (1993). Construction of new Campylobacter cloning vectors and a new mutational cat cassette. Gene 130, 127–130 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90355-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q., Sahin O., Mcdermott P. F., Payot S. (2006). Fitness of antimicrobial-resistant Campylobacter and Salmonella. Microbes Infect. 8, 1972–1978 10.1016/j.micinf.2005.11.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]