Abstract

Some bacterial toxins and viruses have evolved the capacity to bind mammalian glycosphingolipids to gain access to the cell interior, where they can co-opt the endogenous mechanisms of cellular trafficking and protein translocation machinery to cause toxicity. Cholera toxin (CT) is one of the best-studied examples, and is the virulence factor responsible for massive secretory diarrhea seen in cholera. CT enters host cells by binding to monosialotetrahexosylganglioside (GM1 gangliosides) at the plasma membrane where it is transported retrograde through the trans-Golgi network (TGN) into the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). In the ER, a portion of CT, the CT-A1 polypeptide, is unfolded and then “retro-translocated” to the cytosol by hijacking components of the ER associated degradation pathway (ERAD) for misfolded proteins. CT-A1 rapidly refolds in the cytosol, thus avoiding degradation by the proteasome and inducing toxicity. Here, we highlight recent advances in our understanding of how the bacterial AB5 toxins induce disease. We highlight the molecular mechanisms by which these toxins use glycosphingolipid to traffic within cells, with special attention to how the cell senses and sorts the lipid receptors. We also discuss several new studies that address the mechanisms of toxin unfolding in the ER and the mechanisms of CT A1-chain retro-translocation to the cytosol.

Keywords: cholera toxin, membrane trafficking, retro-translocation, ERAD

Introduction

Bacterial toxins must access their cytosolic targets by translocating across a cell membrane (Inoue et al., 2011). This is no small feat, as the toxins are secreted as fully folded water-soluble proteins that undergo a series of structural changes allowing them to integrate into lipid membranes and inject the enzymatic domain in unfolded conformations across a cellular membrane to the cytosol. Once in the cytosol, this domain refolds into a functional enzyme that attacks specific cellular systems.

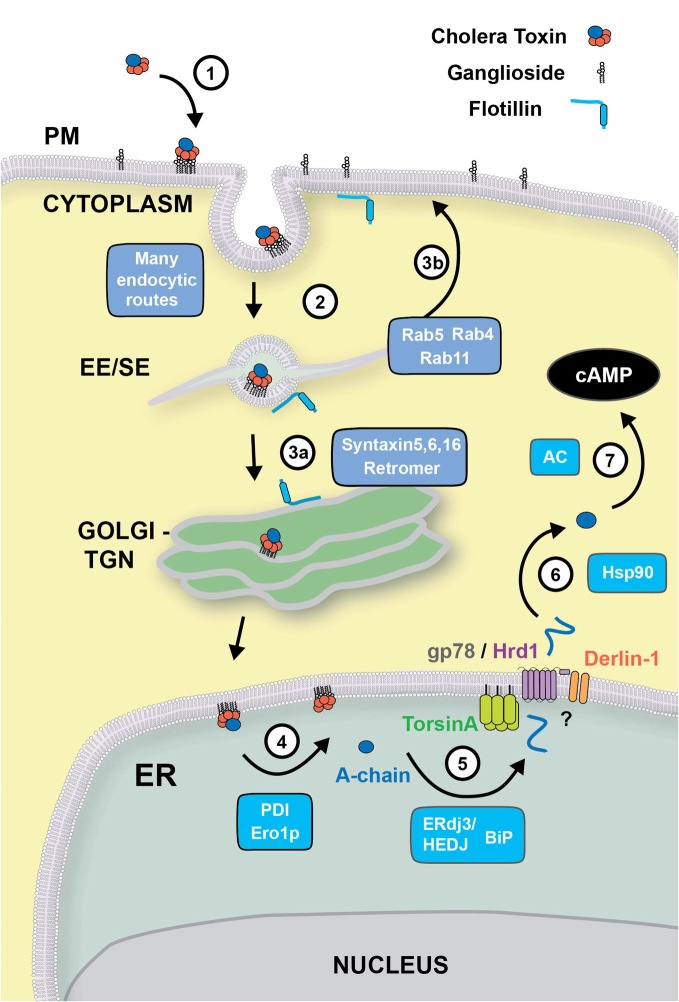

Cholera toxin (CT) typifies the AB5-subunit toxins. It is secreted by the Vibrio cholerae in the intestinal lumen. The toxin enters the cytosol of polarized epithelial cells lining the intestinal lumen by binding to the ganglioside GM1 via its B-subunit. GM1 follows a lipid-based sorting pathway to move the toxin retrograde through the trans-Golgi network (TGN) into the ER. In the ER, the enzymatically active portion of the A-subunit, termed the A1-chain, co-opts the machinery located in the ER lumen to manage terminally misfolded proteins in the secretory pathway (termed the ER associated degradation pathway or ERAD), which unfolds and retro-translocates the A1-chain to the cytosol. Unlike most retro-translocation substrates, the A1-chain escapes degradation by the proteasome and rapidly refolds in the cytosol to act as an ADP-ribosyltransferase. Toxicity is caused by ADP-ribosylation of the heterotrimeric G protein, Gsα that leads to constant activation of adenylyl cyclase and strong increases in cAMP intracellular levels. In intestinal cells, the rapid production of cAMP leads to intestinal chloride secretion, which causes a massive loss of water resulting in the rice-water secretory diarrhea that typifies cholera. This review will summarize current ideas and new findings for how glycosphingolipid-binding toxins gain access to the ER and the mechanisms involved in their retro-translocation into the cytosol (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Retrograde trafficking and retro-translocation of AB5 toxins in host cells. (1) AB5 toxins such as CT and ST, bind to glycosphingolipids located on the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane. (2) In the case of CT, the binding to the ganglioside GM1 effectively clusters the lipid on the cell surface, where endocytosis can occur by clathrin-dependent, or–independent routes. This is known to involve flotillin proteins that can sense membrane microdomains. All internalization pathways converge into the early/sorting endosome compartment (EE/SE), where sorting occurs to the TGN (aided by SNARE proteins Syntaxin 5, Syntaxin 6, Syntaxin 16, and the retromer complex) (3a), to the recycling endosome (via Rab4, Rab5 and Rab11) (3b), or to late endosomes (not shown). (4) From the Golgi, CT is transported to the ER where the A-subunit is dissociated from the B-chain with the aid of PDI and Ero1p. (5) The A-chain is then unfolded by the ERdj3/HEDJ complex along with BiP, where it is translocated across the ER membrane into the cytosol with the aid of TorsinA, gp78/Hrd1 and Derlin-1. (6) Once in the cytosol, the A-chain rapidly refolds in an Hsp90-dependent manner where its catalytic activity stimulates adenylate cyclase (AC) resulting in an intracellular increase of cAMP (7).

Membrane trafficking of toxins and their lipid receptors

After binding to the ganglioside GM1 located on the outer leaflet of the cell membrane, CT travels through a complex endocytic pathway involving retrograde membrane traffic through the Golgi complex to the ER (Step 1) (Chinnapen et al., 2007). Other toxins, such as Shiga toxins (STx), Escherichia coli heat labile toxins and tetanus toxins and some viruses (SV40, polyomavirus) also use glycosphingolipids (gangliosides and globosides) as receptors to enter the cell and cause disease (Spooner et al., 2006). Exactly how the cell senses these lipids to sort them to different intracellular pathways is still unclear. Our knowledge of the endocytic and intracellular pathways co-opted by toxins and their lipid receptors has so far relied on microscopy observations of the bulk flow of fluorescently or radioactively labeled toxins and their lipid receptors or lipid analogues or lipid-specific antibodies. The lack of data tracking individual toxin or lipid molecules as they move within the cell, as well as the promiscuity of endocytic and intracellular pathways co-opted by them, has significantly hindered our ability to dissect the actual itinerary followed by these molecules from the cell surface to their sites of action.

The internalization of globotriaosylceramide (GB3) and GM1 glycosphingolipids, assessed using toxin or antibody markers, appears to be via clathrin-independent pathways, mainly through caveolae (Crespo et al., 2008), but clathrin-dependent pathways have also been reported (Step 2) (Torgersen et al., 2001). The glycosphingolipids seem to be required for the maintenance of caveolae domains (Singh et al., 2010). Gangliosides are well known to establish dynamic physicochemical interactions with cholesterol and other sphingolipids to form membrane nanodomains (Simons and Gerl, 2010; Sonnino and Prinetti, 2010). Exactly how the cell senses and sorts these domains into defined endocytic routes is still unknown. Recent studies have shown that STx, CT and SV40 virus can bind and crosslink glycosphingolipids to trigger membrane deformations (“tubules”) of both artificial membrane models and the plasma membrane of intact cells (Romer et al., 2007; Ewers et al., 2010; Romer et al., 2010). These tubular invaginations may favor toxin and virus internalization, although the capacity of these structures in driving toxin or virus entry is not yet defined. Tubular invaginations have been previously observed in the absence of ganglioside crosslinking, suggesting that other mechanisms of membrane deformation must exist as well (Massol et al., 2005; Boucrot et al., 2010). Although the mechanism for inducing membrane tubulation by the toxins and viruses is not clear, it appears that crosslinking of long chain gangliosides with the proper molecular spacing is required to induce membrane curvature (Ewers et al., 2010). Fission of tubules requires actin polymerization and dynamin function. Similarly to GB3 that binds STx, GM1 lipids containing long saturated acyl chains favor SV40 internalization and infection. Studies of internalization of GPI-anchored proteins, which also favor partitioning in lipid-microdomains or rafts, show that the molecular structures of the lipid chains affect the way they are internalized and trafficked in the cells (Bhagatji et al., 2009). The emerging theme from these studies is that clustering of gangliosides into lipid microdomains at the cell surface can initiate membrane budding events.

Although the preferential route of entry for these toxins and viruses is still quite controversial, it is likely that the actual entry mechanism has little impact in the intracellular sorting required to transport them to their final destinations. This is due to the convergence at the level of the early endosome of cargo derived from clathrin-dependent and clathrin-independent endocytic vesicles (Jovic et al., 2010). After internalization, ganglioside-antibody complexes are transported to the early endosome and later on accumulate transiently in Rab11-positive recycling endosomes en route to the plasma membrane (Step 3b) (Iglesias-Bartolome et al., 2006, 2009). A small fraction of ganglioside-antibody complexes is eventually transported to the Golgi complex and the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) (Step 3a) or to lysosomes.

Though the exact molecular requirements and intracellular location for sorting of the glycosphingolipids remain to be elucidated, it is likely that a key-sorting event takes place at the level of the early endosome. The early endosome exhibits a complex morphology with very thin (∼60 nm) tubular structures emanating from a main vesicular body thought to be functionally important, and many membrane traffic regulators (notably Rab5, Rab4, and their effectors) act on this organelle. Proteins and lipids targeted for recycling are driven into the tubular domains and eventually arrive back at the cell surface, while dissociated ligands remain in the vesicular region that matures into a late endosome/lysosome. Whereas the “geometry-based” model of lipid sorting proposed by Maxfield and McGraw (2004) explains several aspects of protein and ligand sorting at the early endosome, lipid sorting is likely more complex. Recent biophysical studies in model systems and live-cell imaging of lipid analogues have shown that lipid sorting likely depends on the coupling between membrane composition and high curvature of the tubular carriers (Andes-Koback and Keating, 2011); and that this is amplified in the presence of lipid-clustering proteins such as CT (Tian and Baumgart, 2009; Tian et al., 2009). Some toxins and viruses bound to gangliosides are further delivered to the Golgi and then to the ER but the mechanisms of sorting into the retrograde pathways remain unclear. Several protein complexes have been identified to be required for retrograde transport of STx, CT, and Ricin from the early endosome to the TGN/ER e.g., SNARE proteins (Syntaxins 5, 6, and 16) (Amessou et al., 2007; Ganley et al., 2008) and the retromer complex (Popoff et al., 2007, 2009). If, or how, these proteins interact with lipids to regulate sorting between intracellular trafficking pathways remains unknown. The lipid-raft associated protein Flotillin, implicated for clathrin-independent endocytic uptake of CT, has also been shown to be involved in the sorting of CT from the early endosome to the TGN (Glebov et al., 2006; Frick et al., 2007) and the ER (Saslowsky et al., 2010). The retrograde pathway to the ER may also involve a sorting step linking the early endosome to the ER without intersecting the TGN (Saslowsky et al., 2010). Another level of potential regulation of ganglioside and toxin sorting stems from the discovery of enzymes involved in ganglioside remodeling (Daniotti and Iglesias-Bartolome, 2011). Future studies will be needed to clarify the nature of lipid sorting at endosomes and the Golgi complex and the precise role of lipid remodeling in this process.

Mechanism of retro-translocation of toxins

Upon entering the ER, most AB5 bacterial toxins, including CT, undergo dissociation of their enzymatic moieties from their receptor binding subunits. The disulfide bonds that connect the A1 with the A2 polypeptide of CT are reduced in the ER followed by chaperone-mediated unfolding of the A1-chain. These two processing steps are required for the eventual retro-translocation of CT-A1 to the cytosol. The molecular details of these processes remain still unclear, but we favor the following model of CT-A1 dissociation. First, the ER lumenal chaperone protein disulfide isomerase (PDI) binds in its reduced state to a hydrophobic region at the C-terminus of CT-A1 chain allowing for unfolding and dissociation from the B-subunit (Step 4) (Tsai et al., 2001; Tsai and Rapoport, 2002). It is possible that PDI assists predominantly in the dissociation reaction and the CT-A1 subunit unfolds spontaneously (Pande et al., 2007; Massey et al., 2009; Banerjee et al., 2010; Taylor et al., 2011). A similar mechanism of toxin dissociation seems to operate for the AB toxin ricin and STx (Lord et al., 2003; Spooner et al., 2004; Fagerquist and Sultan, 2010).

Several other ER chaperones and components have been described to be of importance for CT retro-translocation to the cytosol (Step 5). The Hsp70 chaperone BiP (heavy chain binding protein) allows for proper folding of nascent peptide chains in the secretory pathway and also regulates the retro-translocation of several ERAD substrates (Nishikawa et al., 2005). In vitro studies suggest that BiP plays a role in maintaining the A1-chain in a soluble, export-competent state required for the retro-translocation reaction (Winkeler et al., 2003), and intoxication by CT may actually up-regulate expression of BiP (Dixit et al., 2008). There is also evidence that the unfolded form of CT-A1 interacts with the ER luminal chaperone Hsp40, ERdj3/HEDJ, in order to mask solvent-exposed hydrophobic residues during retro-translocation (Massey et al., 2011). Interestingly, ERdj3 was shown to directly interact with BiP in the ER (Shen and Hendershot, 2005), suggesting an ERdj3/BiP complex may be involved in stabilizing the unfolded CT-A1 and later targeting it to the retro-translocation channels. ERdj3/HEDJ and BiP have also been shown to interact with the A-subunit of STx and to be important in retro-translocation of the STx enzymatic A-subunit (Yu and Haslam, 2005; Falguieres and Johannes, 2006). In the case of ricin, the ER degradation enhancing alpha-mannosidase I-like protein (EDEM) was reported to facilitate its targeting to the retro-translocons (Slominska-Wojewodzka et al., 2006).

Once unfolded, the CT-A1 chain is presumably targeted to the ER membrane for retro-translocation through a protein-conducting channel. The molecular identity of this channel remains unknown. There is some evidence that the CT-A1 chain may retro-translocate through the Sec61 complex as also proposed for ricin (Rapak et al., 1997) and STx (Yu and Haslam, 2005), but whether, and how, this may occur remains unclear (Wiertz et al., 1996; Pilon et al., 1997; Matlack et al., 1998; Schmitz et al., 2000). Other potential candidates for the retro-translocation channel have emerged, with greatest evidence for a protein complex centered on the E3 ubiquitin ligases HRD1 and gp78 (Bernardi et al., 2010). Other proteins of this complex and adaptor proteins include UBE2G2, SEL1L, AUP1, OS-9, XTP3-B, and Derlins (Smith et al., 2011). Not all may be required for every reaction. Different toxins may utilize different components (Carvalho et al., 2010). In the case of CT, there is there is good evidence that the Hrd1/gp78 complex is required (Bernardi et al., 2010; Carvalho et al., 2010) but conflicting evidence for the dependence on Derlin (Bernardi et al., 2008; Dixit et al., 2008; Saslowsky et al., 2010).

The driving force behind CT retro-translocation and the identities of the cytosolic components in the retro-translocation process also remains to be determined (Step 6). We believe the cytosolic AAA-ATPase p97 that pulls many ERAD substrates from the ER membrane does not play a role in retro-translocation of the CT A1-chain (Kothe et al., 2005). It is possible that an ER luminal AAA-ATPase, TorsinA (Nery et al., 2011), may be involved, but exactly how TorsinA affects CT retro-translocation is not solved. Most studies show that ubiquitination of the toxins is not involved driving retro-translocation (Rodighiero et al., 2002; Li et al., 2010; Wernick et al., 2010).

It is now clear that once in the cytosol, the CT-A1 refolds into a stable conformation that is resistant to proteasomal degradation (Rodighiero et al., 2002). There is evidence this requires cytosolic chaperones. Refolding of the A1-chain in the cytosol depends in part on the small GTPase ADP-ribosylation factor 6 (ARF6), a cytosolic eukaryotic protein that can also enhance the enzymatic activity of CT-A1 (Teter et al., 2006; Pande et al., 2007; Ampapathi et al., 2008), and the cytosolic chaperone Hsp90 that may act to protect the A1-chain from degradation (Taylor et al., 2010) to induce toxicity (Step 7). Refolding of ricin in the cytosol is helped in part by the chaperone Hsc70 and Hsp90 (Spooner et al., 2008).

Summary

While many aspects of lipid-dependent trafficking and retro-translocation of the AB5 toxins remain to be discovered, the recent work in this field has established the outlines of how the toxins co-opt the host cell to enter the cytosol and cause disease. These topics address important aspects of cell biology and toxin action, with broad impact on our understanding of host-pathogen interactions in general.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Amessou M., Fradagrada A., Falguieres T., Lord J. M., Smith D. C., Roberts L. M., Lamaze C., Johannes L. (2007). Syntaxin 16 and syntaxin 5 are required for efficient retrograde transport of several exogenous and endogenous cargo proteins. J. Cell Sci. 120, 1457–1468 10.1242/jcs.03436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ampapathi R. S., Creath A. L., Lou D. I., Craft J. W. Jr., Blanke S. R., Legge G. B. (2008). Order-disorder-order transitions mediate the activation of cholera toxin. J. Mol. Biol. 377, 748–760 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.12.075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andes-Koback M., Keating C. D. (2011). Complete budding and asymmetric division of primitive model cells to produce daughter vesicles with different interior and membrane compositions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 9545–9555 10.1021/ja202406v [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee T., Pande A., Jobling M. G., Taylor M., Massey S., Holmes R. K., Tatulian S. A., Teter K. (2010). Contribution of subdomain structure to the thermal stability of the cholera toxin A1 subunit. Biochemistry 49, 8839–8846 10.1021/bi101201c [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernardi K. M., Forster M. L., Lencer W. I., Tsai B. (2008). Derlin-1 facilitates the retro-translocation of cholera toxin. Mol. Biol. Cell 19, 877–884 10.1091/mbc.E07-08-0755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernardi K. M., Williams J. M., Kikkert M., van Voorden S., Wiertz E. J., Ye Y., Tsai B. (2010). The E3 ubiquitin ligases Hrd1 and gp78 bind to and promote cholera toxin retro-translocation. Mol. Biol. Cell 21, 140–151 10.1091/mbc.E09-07-0586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhagatji P., Leventis R., Comeau J., Refaei M., Silvius J. R. (2009). Steric and not structure-specific factors dictate the endocytic mechanism of glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored proteins. J. Cell Biol. 186, 615–628 10.1083/jcb.200903102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boucrot E., Saffarian S., Zhang R., Kirchhausen T. (2010). Roles of AP-2 in clathrin-mediated endocytosis. PLoS One 5:e10597 10.1371/journal.pone.0010597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho P., Stanley A. M., Rapoport T. A. (2010). Retrotranslocation of a misfolded luminal ER protein by the ubiquitin-ligase Hrd1p. Cell 143, 579–591 10.1016/j.cell.2010.10.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinnapen D. J., Chinnapen H., Saslowsky D., Lencer W. I. (2007). Rafting with cholera toxin: endocytosis and trafficking from plasma membrane to ER. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 266, 129–137 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2006.00545.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crespo P. M., von Muhlinen N., Iglesias-Bartolome R., Daniotti J. L. (2008). Complex gangliosides are apically sorted in polarized MDCK cells and internalized by clathrin-independent endocytosis. FEBS J. 275, 6043–6056 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06732.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniotti J. L., Iglesias-Bartolome R. (2011). Metabolic pathways and intracellular trafficking of gangliosides. IUBMB Life 63, 513–520 10.1002/iub.477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixit G., Mikoryak C., Hayslett T., Bhat A., Draper R. K. (2008). Cholera toxin up-regulates endoplasmic reticulum proteins that correlate with sensitivity to the toxin. Exp. Biol. Med. (Maywood) 233, 163–175 10.3181/0705-RM-132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewers H., Romer W., Smith A. E., Bacia K., Dmitrieff S., Chai W., Mancini R., Kartenbeck J., Chambon V., Berland L., Oppenheim A., Schwarzmann G., Feizi T., Schwille P., Sens P., Helenius A., Johannes L. (2010). GM1 structure determines SV40-induced membrane invagination and infection. Nat. Cell Biol. 12, 11–18 (Suppl. 11–12). 10.1038/ncb1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagerquist C. K., Sultan O. (2010). Top-down proteomic identification of furin-cleaved alpha-subunit of Shiga toxin 2 from Escherichia coli O157:H7 using MALDI-TOF-TOF-MS/MS. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2010, 123460 10.1039/c0an00909a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falguieres T., Johannes L. (2006). Shiga toxin B-subunit binds to the chaperone BiP and the nucleolar protein B23. Biol. Cell 98, 125–134 10.1042/BC20050001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frick C. G., Richtsfeld M., Sahani N. D., Kaneki M., Blobner M., Martyn J. A. (2007). Long-term effects of botulinum toxin on neuromuscular function. Anesthesiology 106, 1139–1146 10.1097/01.anes.0000267597.65120.16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganley I. G., Espinosa E., Pfeffer S. R. (2008). A syntaxin 10-SNARE complex distinguishes two distinct transport routes from endosomes to the trans-Golgi in human cells. J. Cell Biol. 180, 159–172 10.1083/jcb.200707136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glebov O. O., Bright N. A., Nichols B. J. (2006). Flotillin-1 defines a clathrin-independent endocytic pathway in mammalian cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 8, 46–54 10.1038/ncb1342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iglesias-Bartolome R., Crespo P. M., Gomez G. A., Daniotti J. L. (2006). The antibody to GD3 ganglioside, R24, is rapidly endocytosed and recycled to the plasma membrane via the endocytic recycling compartment. Inhibitory effect of brefeldin A and monensin. FEBS J. 273, 1744–1758 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2006.05194.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iglesias-Bartolome R., Trenchi A., Comin R., Moyano A. L., Nores G. A., Daniotti J. L. (2009). Differential endocytic trafficking of neuropathy-associated antibodies to GM1 ganglioside and cholera toxin in epithelial and neural cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1788, 2526–2540 10.1016/j.bbamem.2009.09.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue T., Moore P., Tsai B. (2011). How viruses and toxins disassemble to enter host cells. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 65, 287–305 10.1146/annurev-micro-090110-102855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jovic M., Sharma M., Rahajeng J., Caplan S. (2010). The early endosome: a busy sorting station for proteins at the crossroads. Histol. Histopathol. 25, 99–112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kothe M., Ye Y., Wagner J. S., De Luca H. E., Kern E., Rapoport T. A., Lencer W. I. (2005). Role of p97 AAA-ATPase in the retrotranslocation of the cholera toxin A1 chain, a non-ubiquitinated substrate. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 28127–28132 10.1074/jbc.M503138200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S., Spooner R. A., Allen S. C., Guise C. P., Ladds G., Schnoder T., Schmitt M. J., Lord J. M., Roberts L. M. (2010). Folding-competent and folding-defective forms of ricin A chain have different fates after retrotranslocation from the endoplasmic reticulum. Mol. Biol. Cell 21, 2543–2554 10.1091/mbc.E09-08-0743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord M. J., Jolliffe N. A., Marsden C. J., Pateman C. S., Smith D. C., Spooner R. A., Watson P. D., Roberts L. M. (2003). Ricin. Mechanisms of cytotoxicity. Toxicol. Rev 22, 53–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey S., Banerjee T., Pande A. H., Taylor M., Tatulian S. A., Teter K. (2009). Stabilization of the tertiary structure of the cholera toxin A1 subunit inhibits toxin dislocation and cellular intoxication. J. Mol. Biol. 393, 1083–1096 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.09.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey S., Burress H., Taylor M., Nemec K. N., Ray S., Haslam D. B., Teter K. (2011). Structural and functional interactions between the cholera toxin A1 subunit and ERdj3/HEDJ, a chaperone of the endoplasmic reticulum. Infect. Immun. 79, 4739–4747 10.1128/IAI.05503-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massol R. H., Larsen J. E., Kirchhausen T. (2005). Possible role of deep tubular invaginations of the plasma membrane in MHC-I trafficking. Exp. Cell Res. 306, 142–149 10.1016/j.yexcr.2005.01.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matlack K. E., Mothes W., Rapoport T. A. (1998). Protein translocation: tunnel vision. Cell 92, 381–390 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80930-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxfield F. R., McGraw T. E. (2004). Endocytic recycling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 4, 121–132 10.1038/nrm1315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nery F. C., Armata I. A., Farley J. E., Cho J. A., Yaqub U., Chen P., Da Hora C. C., Wang Q., Tagaya M., Klein C., Tannous B., Caldwell K. A., Caldwell G. A., Lencer W. I., Ye Y., Breakefield X. O. (2011). TorsinA participates in endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation. Nat. Commun. 2, 393 10.1038/ncomms1383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishikawa S., Brodsky J. L., Nakatsukasa K. (2005). Roles of molecular chaperones in endoplasmic reticulum (ER) quality control and ER-associated degradation (ERAD). J. Biochem. 137, 551–555 10.1093/jb/mvi068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pande A. H., Scaglione P., Taylor M., Nemec K. N., Tuthill S., Moe D., Holmes R. K., Tatulian S. A., Teter K. (2007). Conformational instability of the cholera toxin A1 polypeptide. J. Mol. Biol. 374, 1114–1128 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.10.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilon M., Schekman R., Romisch K. (1997). Sec61p mediates export of a misfolded secretory protein from the nedoplasmic reticulum to the cytososl for degradation. EMBO J. 16, 4540–4548 10.1093/emboj/16.15.4540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popoff V., Mardones G. A., Bai S. K., Chambon V., Tenza D., Burgos P. V., Shi A., Benaroch P., Urbe S., Lamaze C., Grant B. D., Raposo G., Johannes L. (2009). Analysis of articulation between clathrin and retromer in retrograde sorting on early endosomes. Traffic 10, 1868–1880 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2009.00993.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popoff V., Mardones G. A., Tenza D., Rojas R., Lamaze C., Bonifacino J. S., Raposo G., Johannes L. (2007). The retromer complex and clathrin define an early endosomal retrograde exit site. J. Cell Sci. 120, 2022–2031 10.1242/jcs.003020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapak A., Falnes P. Ø., Olsnes S. (1997). Retrograde transport of mutant ricin to the endoplasmic reticulum with subsequent translocation to the cytosol. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 3783–3788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodighiero C., Tsai B., Rapoport T. A., Lencer W. I. (2002). Role of ubiquitination in retro-translocation of cholera toxin and escape of cytosolic degradation. EMBO Rep. 3, 1222–1227 10.1093/embo-reports/kvf239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romer W., Berland L., Chambon V., Gaus K., Windschiegl B., Tenza D., Aly M. R., Fraisier V., Florent J. C., Perrais D., Lamaze C., Raposo G., Steinem C., Sens P., Bassereau P., Johannes L. (2007). Shiga toxin induces tubular membrane invaginations for its uptake into cells. Nature 450, 670–675 10.1038/nature05996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romer W., Pontani L. L., Sorre B., Rentero C., Berland L., Chambon V., Lamaze C., Bassereau P., Sykes C., Gaus K., Johannes L. (2010). Actin dynamics drive membrane reorganization and scission in clathrin-independent endocytosis. Cell 140, 540–553 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saslowsky D. E., Cho J. A., Chinnapen H., Massol R. H., Chinnapen D. J., Wagner J. S., De Luca H. E., Kam W., Paw B. H., Lencer W. I. (2010). Intoxication of zebrafish and mammalian cells by cholera toxin depends on the flotillin/reggie proteins but not Derlin-1 or -2. J. Clin. Invest. 120, 4399–4409 10.1172/JCI42958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz A., Herrgen H., Winkeler A., Herzog V. (2000). Cholera toxin is exported from microsomes by the sec61p complex. J. Cell Biol. 148, 1203–1212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Y., Hendershot L. M. (2005). ERdj3, a stress-inducible endoplasmic reticulum DnaJ homologue, serves as a cofactor for BiP's interactions with unfolded substrates. Mol. Biol. Cell 16, 40–50 10.1091/mbc.E04-05-0434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons K., Gerl M. J. (2010). Revitalizing membrane rafts: new tools and insights. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 11, 688–699 10.1038/nrm2977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh R. D., Marks D. L., Holicky E. L., Wheatley C. L., Kaptzan T., Sato S. B., Kobayashi T., Ling K., Pagano R. E. (2010). Gangliosides and beta1-integrin are required for caveolae and membrane domains. Traffic 11, 348–360 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2009.01022.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slominska-Wojewodzka M., Gregers T. F., Walchli S., Sandvig K. (2006). EDEM is involved in retrotranslocation of ricin from the endoplasmic reticulum to the cytosol. Mol. Biol. Cell 17, 1664–1675 10.1091/mbc.E05-10-0961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith M. H., Ploegh H. L., Weissman J. S. (2011). Road to ruin: targeting proteins for degradation in the endoplasmic reticulum. Science 334, 1086–1090 10.1126/science.1209235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonnino S., Prinetti A. (2010). Gangliosides as regulators of cell membrane organization and functions. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 688, 165–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spooner R. A., Hart P. J., Cook J. P., Pietroni P., Rogon C., Hohfeld J., Roberts L. M., Lord J. M. (2008). Cytosolic chaperones influence the fate of a toxin dislocated from the endoplasmic reticulum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 17408–17413 10.1073/pnas.0809013105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spooner R. A., Smith D. C., Easton A. J., Roberts L. M., Lord J. M. (2006). Retrograde transport pathways utilised by viruses and protein toxins. Virol. J. 3, 26 10.1186/1743-422X-3-26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spooner R. A., Watson P. D., Marsden C. J., Smith D. C., Moore K. A., Cook J. P., Lord J. M., Roberts L. M. (2004). Protein disulphide-isomerase reduces ricin to its A and B chains in the endoplasmic reticulum. Biochem. J. 383, 285–293 10.1042/BJ20040742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor M., Banerjee T., Ray S., Tatulian S. A., Teter K. (2011). Protein-disulfide isomerase displaces the cholera toxin A1 subunit from the holotoxin without unfolding the A1 subunit. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 22090–22100 10.1074/jbc.M111.237966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor M., Navarro-Garcia F., Huerta J., Burress H., Massey S., Ireton K., Teter K. (2010). Hsp90 is required for transfer of the cholera toxin A1 subunit from the endoplasmic reticulum to the cytosol. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 31261–31267 10.1074/jbc.M110.148981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teter K., Jobling M. G., Sentz D., Holmes R. K. (2006). The cholera toxin A1(3) subdomain is essential for interaction with ADP-ribosylation factor 6 and full toxic activity but is not required for translocation from the endoplasmic reticulum to the cytosol. Infect. Immun. 74, 2259–2267 10.1128/IAI.74.4.2259-2267.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian A., Baumgart T. (2009). Sorting of lipids and proteins in membrane curvature gradients. Biophys. J. 96, 2676–2688 10.1016/j.bpj.2008.11.067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian A., Capraro B. R., Esposito C., Baumgart T. (2009). Bending stiffness depends on curvature of ternary lipid mixture tubular membranes. Biophys. J. 97, 1636–1646 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.07.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torgersen M. L., Skretting G., van Deurs B., Sandvig K. (2001). Internalization of cholera toxin by different endocytic mechanisms. J. Cell Sci. 114, 3737–3747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai B., Rapoport T. (2002). Unfolded cholera toxin is transferred to the ER membrane and released from protein disulfide isomerase upon oxidation by Ero1. J. Cell Biol. 159, 207–215 10.1083/jcb.200207120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai B., Rodighiero C., Lencer W. I., Rapoport T. (2001). Protein disulfide isomerase acts as a redox-dependent chaperone to unfold cholera toxin. Cell 104, 937–948 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00289-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wernick N. L., de Luca H., Kam W. R., Lencer W. I. (2010). N-terminal extension of the cholera toxin A1-chain causes rapid degradation after retrotranslocation from endoplasmic reticulum to cytosol. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 6145–6152 10.1074/jbc.M109.062067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiertz E. J., Tortorella D., Bogyo M., Yu J., Mothes W., Jones T. R., Rapoport T. A., Ploegh H. L. (1996). Sec61-mediated transfer of a membrane protein from the endoplasmic reticulum to the proteasome for destruction. Nature 384, 432–438 10.1038/384432a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkeler A., Godderz D., Herzog V., Schmitz A. (2003). BiP-dependent export of cholera toxin from endoplasmic reticulum-derived microsomes. FEBS Lett. 554, 439–442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu M., Haslam D. B. (2005). Shiga toxin is transported from the endoplasmic reticulum following interaction with the luminal chaperone HEDJ/ERdj3. Infect. Immun. 73, 2524–2532 10.1128/IAI.73.4.2524-2532.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]