Abstract

Despite dramatic increases in glucose influx during the transition from fasting to fed states, plasma glucose concentration remains tightly controlled. This constancy is in large part due to the capacity of skeletal muscle to absorb excess glucose and store it as glycogen. The magnitude of this capacity is controlled by insulin by way of regulated insertion of glucose transporters into the muscle cell membrane. Here, we examine the mechanism by which muscle cells are able to tolerate large flux increases across their transporters without significantly changing their own metabolite pools. MCA was used to probe data sets that measured the effects of changing plasma glucose and/or insulin concentrations on the rates of glycogen synthesis and the concentrations of metabolites, particularly glucose-6-phosphate. We find that homeostasis is achieved by insulin-dependent phosphorylation changes in GSase sensitivity to the upstream metabolite glucose-6-phosphate. The centrality of GSase to homeostasis resolves the paradox of its sensitivity to allosteric and covalent regulation despite its minimal role in flux control. The importance of this role for enzymatic phosphorylation to diabetes pathology is discussed, and its general applicability is suggested.

Metabolic control analysis (MCA) has revolutionized our understanding of flux control through theoretical and experimental studies (1–4). One of its key precepts is the flux control coefficient, a quantitative characterization of the influence of any enzyme over the flux of a metabolic pathway. As MCA has matured, it has expanded into associated areas. One of particular interest has been the mechanism of metabolite control, in which the central question is how metabolite homeostasis, the constancy of metabolite concentrations, is maintained during changes in flux (5–9). One well known example of such metabolite homeostasis comes from the study of fluxes through the energetic pathway of glucose oxidation. There, the flux can change by more than an order of magnitude whereas metabolites remain constant within small experimental error (10, 11). Although theoretical analyses of such homeostatic phenomena have been available since the first description of MCA, physical exploration of this important physiological area has been scarce due to experimental limitations. The primary hurdle has been the difficulties in simultaneously obtaining in vivo values of metabolite concentrations and of fluxes through the pathway.

These limitations have been somewhat eased by the development of in vivo NMR methods. Valuable information about energetics has been obtained by 31P NMR of high-energy metabolites (e.g., ATP, PO4, and creatine phosphate) and about metabolic regulation from phosphorylated pathway intermediates such as glucose-6-phosphate (G6P) (12). In complementary experiments, the weak natural abundance (1.1%) of the 13C isotope allows direct 13C NMR of labeled 13C substrates to measure flux, by following the time course of label flow into metabolic pools (13). Comprehensive applications, in a series of studies, of 31P and 13C NMR to one pathway, together with the evaluation of enzyme parameters required by MCA have enabled us to obtain a combined understanding of flux control and homeostasis. These results are presented in this article for a particular pathway, that of glycogen synthesis in the rat gastrocnemius muscle. Because enzymatic phosphorylation and allostery have dominant roles in the control of this pathway, this 2-fold experimental approach has revealed conclusions of considerable generality about the functions served in vivo by enzymatic phosphorylation.

The analysis of control and regulation of metabolism in terms of supply and demand blocks by Hofmeyr and Cornish-Bowden (5, 6) is relevant here because the question about the homeostasis of G6P can be framed in terms of the supply of, and demand for, this metabolite. They define the degree of homeostasis of G6P that can be expected given the direct kinetic effects of G6P on both blocks through substrate, product and effector interactions when an external stimulus changes flux in one of the blocks. Thus, allostery helps to achieve metabolite homeostasis but is limited by the cooperativity of the allosteric response.

In theory, better homeostasis of metabolites could be obtained if flux changes were brought about by stimuli acting at more than one point. Thus, Kacser and Acerenza (14) suggested that fluxes could be increased while maintaining intermediate constancy by simultaneously increasing the activity of enzymes immediately both up and downstream from each metabolite in exact proportion. They posited that, without such alterations, intermediate metabolite concentrations would change and could perturb linked pathways. Because multiple enzymes must be altered simultaneously to fulfill this postulate of homeostasis, gene regulation was suggested as a useful mechanism because shared promoters can link the concentrations of different proteins and changes can be of any duration. However, transcription and translation can take minutes or even hours to exert their full effect. Whereas many examples are known where chronic changes in metabolic state are accompanied by coordinate changes of all of the enzymes in the pathway by relatively similar amounts (15), an organism depending solely on genetic regulation to respond to metabolic changes, which can change on the seconds time scale or even faster, would find itself perpetually behind the times. To respond more effectively, it would need more dynamic systems.

It has been proposed that selected multisite posttranslational modulation, in particular enzymatic phosphorylation, could substitute for the cumbersome genetic changes in enzymatic concentrations (4, 7, 16). Such multisite modulation could retain regulation of metabolites during large-scale changes in enzymatic concentration by changing the activity of selected enzymes. These multisite control points would change activity to exercise metabolite control. In a specific example, glycogen synthase (GSase), an allosteric and reversibly phosphorylated enzyme that was once thought of as flux controlling, has been proposed to regulate metabolite concentration (16).

To test the hypothesis that modulation by both allosteric and phosphorylation mechanisms might serve this homeostatic role, we extended the earlier studies of the role of muscle GSase in flux control and G6P homeostasis (16, 17). This enzyme has at least 12 phosphorylation sites and is sensitive to some half dozen allosteric effectors, most notably the upstream metabolite G6P (18). Additionally, it was long thought of as the rate-limiting enzyme in glycogen synthesis (18). However, the flux control of this pathway in mammalian muscle [whose derangement in non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus (NIDDM) seems to be one of the major causes of pathology] has been shown to reside predominantly in the glucose transporter (GT) (Fig. 1) (16, 17, 19–22). Furthermore, 3-fold pharmacological activation of muscle GSase activity has no effect on insulin-stimulated muscle glycogen synthesis (23). Similarly, in rat hepatocytes, control of glycogen synthesis is shown to reside in the hexokinase (HK) IV, or glucokinase, (24) as opposed to GSase. These findings highlighted the question of why, given its small role in flux control in both tissues, GSase velocity needs so much regulation. Using new results generated from in vivo NMR measurements in our laboratory, as well as older data from Rossetti and Hu (25), we now show that the purpose of the regulation of GSase by phosphorylation and by allostery is to maintain steady concentrations of pathway intermediates despite huge changes in pathway flux.

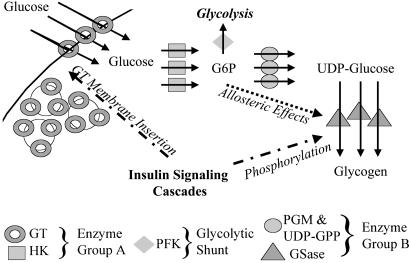

Fig. 1.

Muscle glycogen synthesis pathway. GT, divided between an active membrane fraction and an inactive vesicle fraction, moves plasma glucose into the cytoplasm where it is phosphorylated by HK into G6P. Isomerized G6P can serve as the substrate for phosphofructo-kinase (PFK), the entry point into glycolysis. However, under conditions favoring glycogen synthesis, a majority of G6P is converted by phosphoglucomutase (PGM) and UDP-glucose pyrophosphorylase (UDP-GPP) into UDP-glucose. UDP-glucose is the substrate for GSase, which is ultimately responsible for making glycogen. The pathway is regulated by downstream insulin-induced effects in at least two locations. First, insulin is the primary determinant of the distribution of GT between membrane and vesicles. Second, insulin affects GSase velocity and allosteric responsiveness by way of phosphorylation. Additionally, G6P can induce its own consumption by allosterically stimulating GSase. The lower section of the diagram indicates the distribution of the glycogen synthetic enzymes into subsystems A and B.

Methods

Metabolic Control Analysis. The control of an enzyme E over pathway flux can be expressed as a flux control coefficient  , which is defined as the fractional change in pathway flux (J) over the fractional change in enzyme activity:

, which is defined as the fractional change in pathway flux (J) over the fractional change in enzyme activity:

|

[1] |

The elasticity of an enzyme with respect to a given metabolite  is expressed as the fractional change in the activity of that enzyme (E) for a given fractional change in metabolite concentration (M).

is expressed as the fractional change in the activity of that enzyme (E) for a given fractional change in metabolite concentration (M).

|

[2] |

The connection between elasticities and the flux control coefficients is given by the connectivity relationship (1, 2):

|

[3] |

This equation states that, for any metabolite M, the product of the flux control coefficients of the n enzymes with their elasticities with respect to M sums to zero. As a result, where only the two enzymes producing and consuming M respond to it, there is a tendency for the enzyme with a low value of its elasticity compared with the other to have a high control coefficient and vice versa. This condition applies in the supply–demand analysis below.

Whereas the above terms and relationships were initially defined for single enzymes, they have been shown to be equally valid for groups of contiguous steps in a pathway, provided certain conditions are met (26). The most extreme case of this simplification, in which long pathways can be considered as two subsystems separated by a common metabolite, is called “top down” analysis (27). In the pathway from glucose to glycogen, provided the branch flux to glycolysis is relatively small as it is in resting muscle, the two subsystems can be defined as (i) the GT/HK subsystem, which generates G6P from blood glucose, and (ii) the GSase subsystem, which converts G6P into glycogen (Fig. 1).

Supply–Demand Analysis. In a supply–demand system such as the one treated here, as stated above, the distribution of flux control depends on the ratio of the supply and demand elasticities to G6P: the lower the ratio the more control shifts to the supply. On the other hand, the degree of homeostatic maintenance of this linking metabolite, when either the supply or the demand block is activated, depends on the G6P concentration control coefficients of the two blocks, which are inversely proportional to the sum of the supply and demand elasticities (4–6). Hence, the greater this sum, the smaller the impact of activation on G6P concentration, and the better the homeostasis. If one reaction block controls the flux, then the maintenance of homeostasis of the linking metabolite becomes the function of the other reaction block. If all of the flux control is, say, in the supply (which implies that the demand elasticity >> supply elasticity), then, in this instance, homeostasis depends only on the demand elasticity (6).

General Proportionality Analysis. A proportional activation term (π) quantitatively compares the effect of some external factor (X) on the activities of subsystems A and B (8). The most general expression of π is in terms of the relative elasticities of A and B to X:

|

[4] |

Qualitatively, Eq. 4 indicates that if X acts primarily through subsystem B then  values will be >1, and if it acts through subsystem A then

values will be >1, and if it acts through subsystem A then  values will be <1.

values will be <1.  values of unity indicate equivalent action of X on both A and B. Negative values, which would indicate that X stimulates one subsystem while suppressing the other, were not considered here although they may be applicable to other pathways.

values of unity indicate equivalent action of X on both A and B. Negative values, which would indicate that X stimulates one subsystem while suppressing the other, were not considered here although they may be applicable to other pathways.

The response of the system to a change in X will contain contributions from the direct changes in activity of blocks A and B induced by X and from the changes in activity of the blocks caused by the consequential changes in the linking metabolite M between the blocks. Korzeniewski et al. (8) showed that, by taking these components of the response into account, Eq. 4 could be transformed into:

|

[5] |

The term (∂ln M/∂ln J), which appears in the numerator and denominator, can be obtained as the slope of a graph of ln M vs. ln J for various values of X, and is also known as  , the coresponse coefficient of M and J to X (28), or τ (8). Rewriting Eq. 5 in terms of τ gives:

, the coresponse coefficient of M and J to X (28), or τ (8). Rewriting Eq. 5 in terms of τ gives:

|

[6] |

This form provides boundary conditions for the description of  . Substituting

. Substituting  into Eq. 6 shows

into Eq. 6 shows  is then zero, so from the definition of

is then zero, so from the definition of  , the effector must actualize its effects on flux entirely by way of subsystem A so that any changes in subsystem B are the result of feed-forward stimulation by way of the connecting metabolite (in this case G6P). Similarly, if τ approaches

, the effector must actualize its effects on flux entirely by way of subsystem A so that any changes in subsystem B are the result of feed-forward stimulation by way of the connecting metabolite (in this case G6P). Similarly, if τ approaches  , then

, then  goes toward infinity and the effector operates in the opposite manner: A is “pulled” along by a drop in M (in this case G6P). Finally, if M is unchanged when J is stimulated, then τ = 0,

goes toward infinity and the effector operates in the opposite manner: A is “pulled” along by a drop in M (in this case G6P). Finally, if M is unchanged when J is stimulated, then τ = 0,  = 1, the two subsystems have been activated an equal amount with respect to X, and the metabolite is not playing a direct role in activating either subsystem. In this last case, the teleologically inclined might state that X is modulating both A and B for the purpose of maintaining steady levels of the metabolite despite flux changes.

= 1, the two subsystems have been activated an equal amount with respect to X, and the metabolite is not playing a direct role in activating either subsystem. In this last case, the teleologically inclined might state that X is modulating both A and B for the purpose of maintaining steady levels of the metabolite despite flux changes.

Proportional Activation Analysis of Glycogen Synthesis. To solve Eq. 5, it is necessary to possess values for the change in pathway flux and metabolite concentration, and for the elasticities of subsystems A and B with respect to M under varying conditions of the external parameter X. Given our interest in the role of insulin signaling in maintaining homeostasis, we have selected insulin as the external (X) parameter. Under conditions of elevated insulin (infused at 10 milliunits/kg per min), the elasticities of GT/HK ( ) and GSase (

) and GSase ( ) with respect to G6P have been derived by Chase et al. (22), who determined the GT/HK elasticity for a range of glycolytic fluxes. Because Eq. 4 is based on a linear pathway and because glycolytic shunting from the glycogen synthetic pathway is low during high fluxes, we used the elasticity value of -0.185, determined for the lowest glycolytic flux. This value is consistent with NMR measurements of this flux by Jucker et al. (20). The in vitro elasticity of GSase was reported as 0.79. However, this value was a misprint (D.R., unpublished results), and we are using the corrected value of 0.97. These values result in reciprocal elasticities (that is, potential limiting values of τ for

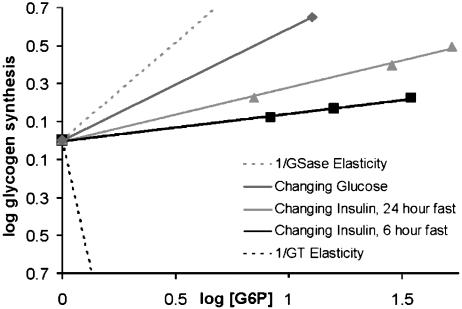

) with respect to G6P have been derived by Chase et al. (22), who determined the GT/HK elasticity for a range of glycolytic fluxes. Because Eq. 4 is based on a linear pathway and because glycolytic shunting from the glycogen synthetic pathway is low during high fluxes, we used the elasticity value of -0.185, determined for the lowest glycolytic flux. This value is consistent with NMR measurements of this flux by Jucker et al. (20). The in vitro elasticity of GSase was reported as 0.79. However, this value was a misprint (D.R., unpublished results), and we are using the corrected value of 0.97. These values result in reciprocal elasticities (that is, potential limiting values of τ for  = infinity and 0, respectively) of -5.41 for the GT/HK subsystem and 1.03 for GSase subsystem. These latter values appear as the reference limiting slopes shown in Fig. 3. The in vivo elasticity of GSase under the conditions of low glycolytic flux was reported to be 1.9, resulting in a reciprocal elasticity of 0.53. We performed the proportionality analysis by using both the in vitro and in vivo elasticity and discuss the impact of the differences on the calculated results later in the text.

= infinity and 0, respectively) of -5.41 for the GT/HK subsystem and 1.03 for GSase subsystem. These latter values appear as the reference limiting slopes shown in Fig. 3. The in vivo elasticity of GSase under the conditions of low glycolytic flux was reported to be 1.9, resulting in a reciprocal elasticity of 0.53. We performed the proportionality analysis by using both the in vitro and in vivo elasticity and discuss the impact of the differences on the calculated results later in the text.

Fig. 3.

GSase and glucose transport coresponsivity. The coresponse coefficients (τ values) for the conditions of constant insulin with increasing glucose [values from Chase et al. (22)] and constant glucose with increasing insulin [values from Rossetti and Hu (25)] are given by the slopes of the lines on this plot. The dotted lines plot the extreme τ values of  and

and  . The observed τ value for changing glucose [Chase et al. (22)], equaling

. The observed τ value for changing glucose [Chase et al. (22)], equaling  (see Methods), is the alternative reference value for calculating the

(see Methods), is the alternative reference value for calculating the  values for insulin. Its closeness to the extreme condition of

values for insulin. Its closeness to the extreme condition of  is additional support for the hypothesis that glucose affects flux primarily by way of GT/HK and thus results in poor G6P homeostasis. The τ values for changing insulin are much closer to a null value, indicating distributed control and comparatively good G6P homeostasis. The flux and concentration values from the different experiments have been normalized relative to unit flux and G6P concentrations in the controls.

is additional support for the hypothesis that glucose affects flux primarily by way of GT/HK and thus results in poor G6P homeostasis. The τ values for changing insulin are much closer to a null value, indicating distributed control and comparatively good G6P homeostasis. The flux and concentration values from the different experiments have been normalized relative to unit flux and G6P concentrations in the controls.

The value of τ was calculated from the slope of the plots of log Vglycogen synthesis vs. log [G6P] (Fig. 3) by using data obtained by Rossetti and Hu (25), and Chase et al. (22) over a range of insulin levels with a constant level of glucose (Fig. 2 A and B). In both cases, the animals had been fasted before the experiment to simulate the conditions of the transition from fasting to fed states.

Fig. 2.

Insulin effects on GSase and [G6P], adapted from Rossetti and Hu (25) describing the changes in [G6P] (♦) and glycogen synthetic rate ( ) at constant plasma glucose whereas plasma insulin was elevated from 350 to 2,700 (A) or from 250 to 2,400 (B) pmol in rats that had been fasted for 6 h (A) or 24 h (B). Although [G6P] increases <1.7-fold (A)or <3-fold (B), glycogen synthesis increases >30-fold (A) or >50-fold (B). Note different scales.

) at constant plasma glucose whereas plasma insulin was elevated from 350 to 2,700 (A) or from 250 to 2,400 (B) pmol in rats that had been fasted for 6 h (A) or 24 h (B). Although [G6P] increases <1.7-fold (A)or <3-fold (B), glycogen synthesis increases >30-fold (A) or >50-fold (B). Note different scales.

Results

X = Insulin: Calculation of Proportional Activation Using in Vitro and in Vivo Elasticities. In the experiments by Rossetti and Hu (25), fasted animals were exposed to stepwise increases in plasma insulin with constant plasma glucose. Both [G6P] and the glycogen synthesis rate rose with higher insulin (see Fig. 2 A and B). However, whereas the [G6P] rise over the full range of insulin levels ranged from ≈1.6- to 3-fold, the increase in glycogen synthesis rate was a much greater ≈35- to 50-fold. Because the [G6P] changes were very small relative to those in glycogen synthesis, the τ values were small (0.15 and 0.28 for the 6- and 24-h fasted rats, respectively), and the π values, 0.83 and 0.69 (using in vitro elasticities) and 0.7 and 0.44 (using in vivo elasticities), were in the range where it must be concluded there is a significant activation of the GSase subsystem in addition to that of the GT/HK subsystem (Fig. 3). That is, insulin must act on the subsystems both up and downstream of G6P (GT/HK and GSase) directly and to moderately comparable degrees, rather than exclusively through feed-back or feed-forward systems that make use of changes in G6P concentration. Qualitatively, this result means that insulin is able to effect flux changes with minimal perturbation of G6P homeostasis.

Effect of Phosphorylation State on the Elasticity of Glycogen Synthase. A limitation of using the Chase et al. (22) elasticity results is that they were measured for one value of insulin whereas the data used to calculate τ were obtained over the full range of physiological through supraphysiological insulin concentrations. Examination of Fig. 3 shows that the value of τ is low (and, within accuracy, constant) throughout the range examined, which means that, provided the elasticities of the system do not change greatly with insulin, the conclusion of a proportional activation near unity is valid throughout the range of insulin-stimulated GSase activation. To assess whether there could be large changes in the elasticity of GSase, we analyzed the in vitro results of GSase velocity vs. G6P as a function of the degree of GSase phosphorylation as plotted by Roach and Larner (29). These measurements were performed under similar conditions, designed to mimic the in vivo milieu, as the in vitro measurements of the Chase et al. (22) study. The elasticities calculated from the %I (where I is the active G6P-independent form) range induced by physiological levels of insulin levels (<≈40%I) were 1.2 (≈10%I) and 0.84 (≈20%I), both comparable to the Chase et al. (22) value of 0.97 measured at ≈40%I. At ≈60%I, GSase elasticity dropped to 0.20, suggesting that, at supraphysiologic levels of insulin, GSase may be even less sensitive to G6P than our model suggests and that our prediction is a minimum estimate of the amount of proportional activation seen between GSase and GT. Homeostasis may depend even less on feed-forward activation of GSase than our conservative interpretation indicates.

Discussion

Our results, in conjunction with the previous control analysis presented by Chase et al. (22), have implications specifically for the glycogen synthesis pathway and for metabolic control in general. The conditions of high glucose and variable insulin that we examined grossly reflect the two-step transition from the fasting to the fed state in mammals. In the fasting state, both blood glucose and plasma insulin are low, reflecting the decreased environmental availability of glucose and the attendant lack of need for insulin control. With feeding, there is a rapid rise in plasma glucose that initially outpaces the ability of the pancreas to release insulin. Several minutes after the onset of feeding, the pancreas begins to release insulin in substantial quantities into the bloodstream, resulting in a fall of plasma glucose concentration to close to pre-meal values. For example, in the case of healthy human subjects given a large mixed meal, plasma glucose rises from 5.4 to 7.3 mmol in the first 30 min after a meal, followed by a rapid fall to 6.4 mmol at 75 min and a progressive decrease to pre-meal levels at 240 min (30, 31). During the high insulin phase, there is a large increase in muscle glycogen synthesis (30, 31) as observed in studies under controlled high insulin conditions such as the Chase et al. (22) and Rosetti and Hu (25) articles used in the present analysis. The increase in glycogen synthesis removes excess glucose from the blood and plays a key role in maintaining plasma glucose homeostasis. In type 2 diabetes, where insulin-stimulated muscle glycogen synthesis is reduced as much as 2-fold (31, 32), plasma glucose levels are as high as 10 mM even 240 min after a meal (31). Despite the manyfold increase in glycogen synthesis, there are only small insulin-stimulated changes in G6P (e.g., refs. 12, 19, 20, 22, 25, 33, and 34). Looking at these dual requirements of the muscle glycogen synthesis pathway, to maintain plasma glucose and cellular G6P homeostasis together, we propose below a model for how the kinetic properties of the enzymes of the muscle glycogen synthesis system, and the alterations in their activity with insulin signaling, meet these simultaneous demands.

Role of Insulin-Stimulated Proportional Activation in Maintaining Plasma Glucose and Muscle G6P Homeostasis During the Steady State Absorption Period. Release of insulin by the pancreas during glucose absorption leads to the coordinate activation of glucose transport, HK, and GSase by way of insulin-signaling pathways. However, given that glucose transport has the dominant flux control coefficient and the elasticity of GSase is high even at low phosphorylation levels, it is not necessary to activate GSase to have the glycogen synthesis rate increase sufficiently to match glucose absorption into the blood. The importance of the coordinate activation in maintaining both plasma glucose and G6P homeostasis may be appreciated by examining the consequences of no activation of GSase.

At a given insulin level, glucose concentration can only increase muscle glycogen synthesis linearly, due to the kinetic properties of glucose transport and HK (17). Because the rate of glucose influx from the digestive system can be high and last for several hours, plasma glucose concentrations would not activate muscle glycogen synthesis sufficiently to reach a steady state until glucose rises to many times fasting levels. G6P levels would rise proportionately to glucose, leading to severe alterations in cellular homeostasis and possibly of transport control due to feedback inhibition on HK. This phenomenon is evidenced by the extraordinarily high plasma glucose concentrations achieved after a meal by insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus patients, who cannot produce insulin.

Insulin stimulation of the GT/HK and GSase portions of the muscle glycogen synthesis pathway therefore is necessary to deal with substantial sustained glucose influx while maintaining plasma glucose and cellular G6P homeostasis. As insulin concentration rises, glycogen synthesis may increase >30-fold, an order of magnitude different from when synthesis is stimulated by glucose alone. However, the concentration of G6P rises <2-fold across this range, and plasma glucose concentration is maintained at only 20% above pre-meal levels. From the axiom of Kacser and Acarenza: for metabolite concentration to be maintained despite such a precipitous rise in flux, the enzymes both upstream and downstream of the metabolite must increase their activity in parallel.

It should be noted that we did not observe a value of  of 1.0, but a slightly lower value suggesting somewhat imperfect proportional activation. If we make the coresponse coefficient τ the subject of Eq. 6, for a value of

of 1.0, but a slightly lower value suggesting somewhat imperfect proportional activation. If we make the coresponse coefficient τ the subject of Eq. 6, for a value of  of 0.7, it can be seen that the larger the value of the elasticity of GSase to G6P,

of 0.7, it can be seen that the larger the value of the elasticity of GSase to G6P,  , the closer τ will approach zero. In other words, the cooperative response of GSase to its effector G6P is still making some contribution to the homeostasis of G6P levels whereas, had

, the closer τ will approach zero. In other words, the cooperative response of GSase to its effector G6P is still making some contribution to the homeostasis of G6P levels whereas, had  been unity, the value of this elasticity would be irrelevant.

been unity, the value of this elasticity would be irrelevant.

The Roles of Insulin-Induced Phosphorylation and Allostery in the Proportional Activation of GSase. Insulin has been shown to increase GT activity by moving storage vesicles to the plasma membrane. However, were this the only way for it to increase glycogen synthesis, then G6P concentration would have to be considerably higher and the π value would approach zero. Because the π value approaches unity, insulin signaling must directly stimulate an increase in GSase activity to match the increase in GT flux. It is well established that insulin, through signaling pathways not yet fully defined, also leads to a rapid (minutes) change in the phosphorylation state of GSase, which alters its kinetics (35). Based on the in vitro studies of Chase et al. (22), as well as earlier studies of Roach and Larner (29), the change in phosphorylation state is sufficient to explain most of the increase in activity with insulin stimulation and, as the present analysis shows, leads to a π value close to unity. However, the in vivo elasticity measured by Chase et al. (22) is higher than the in vitro value, suggesting the possibility of additional mechanisms for activating GSase. These mechanisms may include a dual role of G6P as a substrate of the block and as an allosteric effector of GSase. Although the latter term is likely to be dominant because elasticities of cooperative effects are larger than simple substrate elasticities, the response of GSase will have a component due to an increase of UDP-glucose, which is hidden within the GSase block of enzymes and metabolites considered in the control analysis, but which will be correlated with the G6P level. Because the in vivo levels are well below the GSase Km, if the concentration of UDP-glucose increased proportionately with [G6P], it would explain the higher in vivo elasticity without the need to postulate an additional mechanism of GSase activation.

Relevance to Human Insulin-Stimulated Glucose Metabolism and Diabetes. Whereas this study evaluated data from rodents, we have some reason to believe that it may be applicable to human subjects as well. Specifically, even under experimentally induced conditions of hyperglycemia and hyperinsulinemia, healthy human subjects never displayed a >2-fold increase in [G6P] (12, 33, 34, 36, 37), suggesting the importance of G6P homeostasis in human skeletal muscle. Given the delicacy of the system's homeostatic balance, it is surprising that it does not seem to be substantially disrupted in patients with non-insulin-dependent diabetes (NIDDM) or genetic, obesity, and lipid-induced insulin resistance (IR) (12, 33, 34, 37). This finding has implications for our understanding of diabetes pathology and pharmacology. Specifically, because NIDDM and IR patients are able to maintain G6P homeostasis, both subsystems of the glycogen synthetic pathway must be adequately functioning and responsive (although down-regulated). Thus, defects in glycogen synthesis seem to be the result of balanced, if insufficient, signaling on the part of insulin rather than isolated defects in particular pathway enzymes. This conclusion is consistent with the finding of impaired signaling protein activity in both insulin-resistant syndromes and in lipid-induced IR (for a review, see ref. 38). This result suggests that investigations of diabetes pathology and pharmacologic interventions be focused on upstream insulin signaling. Furthermore, it suggests that pharmacological approaches that modulate isolated enzymes not only may fail to address the underlying pathophysiology, but also may worsen conditions by unlinking GSase and GT/HK and disrupting previously good homeostasis. However, it should be noted that, whereas healthy individuals maintained good homeostasis, a small fraction of IR subjects displayed deviations that were lost when averaged with their peers (D. L. Rothman, personal communication). Thus, whereas interventions aimed at particular enzymes may not be effective for addressing most patients, certain individual can be selected who are likely to benefit from such treatments.

Phosphorylation as a General Homeostatic Mechanism. Presently, changes in gene expression during changes of state are intensely studied in organisms ranging from bacteria to humans. Many of the gene products have been shown to be kinases and to change degrees of phosphorylation. In the absence of another function for enzymatic phosphorylation, it is assumed that flux is being controlled. The present results, showing that phosphorylation of GSase serves to maintain homeostasis, not to control flux, challenge the universality of that assumption and offer an alternate function. To the extent that biochemical mechanisms are postulated on the assumption that kinase activity controls flux, caution must be exercised in view of the present results. An equivalent point has been made by Hofmeyr and Cornish-Bowden (5, 6) with respect to the greater importance of the cooperativity of allosteric enzymes in metabolite homeostasis than in flux control.

Given the success of the glycogen synthetic pathway at coordinating internal and external homeostasis, it seems likely that there are analogous arrangements in other pathways, at least in storage pathways that concentrate flux control on the supply side to coordinate storage with nutrient availability. [Such organization seems less likely in biosynthetic pathways that tend to locate flux control in the final steps to coordinate control with demand (5).] Specifically, we predict the following as a general mechanism for the linkage of internal and external homeostasis at a variety of time scales, particularly for supply-controlled pathways. Rapid and small-scale flux changes will be controlled by a subsystem that acts by mass action and thus responds primarily to changes in the external milieu. The activity of its paired subsystems will be coordinated by allosteric modulation, at the expense of perfectly maintained internal homeostasis. Larger-scale flux changes operating on a more intermediate time scale will involve an external detector/effector (e.g., pancreas/insulin) that stimulates both up- and downstream subsystems, thereby maintaining excellent internal and external homeostasis despite increased flux. However, as it relies on an external detector, it is necessarily slower and requires a more complex mechanism to stimulate the two subsystems equivalently. In the example discussed above, this stimulation is achieved through phosphorylation. Other mechanisms could realize the same end, but there is every reason to expect that phosphorylation will serve other pathways similarly although, for operations of a much longer time scale, there remains the well described method of altering gene expression. Although this is an excellent way to pair multiple subsystems, it is necessarily the slowest and most coarse homeostatic and flux-modulating mechanism.

As dynamic in vivo measurements become increasingly available from multicellular organisms that must manage homeostasis in different compartments, we anticipate an increased interest in understanding how pathways are able to meet the duel requirements of changing flux while maintaining homeostasis. The complex phosphorylation states and allosteric sensitivity of GSase, engineered to serve metabolite homeostasis rather than flux control, provides one well understood example of the realization of those goals.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grant DK27121 and Medical Scientist Training Program Training Grant GM07205 (to J.R.A.S.).

Abbreviations: G6P, glucose-6-phosphate; GSase, glycogen synthase; HK, hexokinase; MCA, metabolic control analysis; GT, glucose transporter; %I, the active G6P-independent form.

References

- 1.Kacser, H. & Burns, J. A. (1973) Symp. Soc. Exp. Biol. 27, 65-104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kacser, H., Burns, J. A. & Fell, D. A. (1985) Biochem. Soc. Trans. 23, 341-366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heinrich, R. & Rapoport, T. A. (1974) Eur. J. Biochem. 42, 89-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fell, D. A. (1997) Understanding the Control of Metabolism (Portland Press, London).

- 5.Hofmeyr, J. H. & Cornish-Bowden, A. (1991) Eur. J. Biochem. 200, 223-236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hofmeyr, J. H. & Cornish-Bowden, A. (2000) FEBS Lett. 476, 47-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fell, D. A. & Thomas, S. (1995) Biochem. J. 311, 35-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Korzeniewski, B., Harper, M. E. & Brand, M. D. (1995) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1229, 315-322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thomas, S. & Fell, D. A. (1996) J. Theor. Biol. 182, 285-298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hochachka, P. W. (1994) Muscles as Molecular and Metabolic Machines (CRC, Boca Raton, FL).

- 11.Thomas, S. & Fell, D. A. (1998) Adv. Enzyme Regul. 38, 65-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rothman, D. L., Shulman, R. G. & Shulman G. I. (1992) J. Clin. Invest. 89, 1069-1072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shulman R. G. & Rothman D. L. (2001) Annu. Rev. Physiol. 63, 15-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kacser, H. & Acerenza, L. (1993) Eur. J. Biochem. 216, 361-367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fell, D. A. (2000) Adv. Enzyme Regul. 40, 35-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shulman R. G. & Rothman D. L. (1996) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93, 7491-7495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shulman, R. G., Bloch, G. & Rothman, D. L. (1995) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92, 8535-8542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roach, P. J. (2002) Curr. Mol. Med. 2, 101-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jucker, B. M., Rennings, A. J., Cline, G. W. & Shulman, G. I. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 10464-10473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jucker, B. M., Rennings, A. J., Cline, G. W., Peterson, K. F. & Shulman, G. I. (1997) Am. J. Physiol. 272, E139-E148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cline, G. W., Petersen, K. F., Krssak, M., Shen, J., Hundal, R. S., Trajanoski, Z., Inzucchi, S., Dresner, A., Rothman, D. L. & Shulman, G. I. (1999) N. Engl. J. Med. 341, 240-246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chase, J. R., Rothman, D. L. & Shulman, R. G. (2001) Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 280, E598-E607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cline, G. W., Johnson, K., Regittnig, W., Perret, P., Tozzo, E., Xiao, L., Damico, C. & Shulman, G. I. (2002) Diabetes 51, 2903-2910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Agius, L., Peak, M., Newgard, C. B., Gomez–Foix, A. M. & Guinovart, J. J. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 30479-30486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rossetti, L. & Hu, M. (1993) J. Clin. Invest. 92, 2963-2974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fell, D. A. & Sauro, H. M. (1985) Eur. J. Biochem. 148, 555-561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brown, G. C., Hafner, R. P. & Brand, M. D. (1990) Eur. J. Biochem. 188, 321-325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hofmeyr, J. H. & Cornish-Bowden, A. (1996) J. Theor. Biol. 182, 371-380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roach, P. J. & Larner, J. (1976) J. Biol. Chem. 251, 1920-1926. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Taylor, R., Price, T. B., Katz, L. D., Shulman, R. G. & Shulman, G. I. (1993) Am. J. Physiol. 265, E224-E229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carey, P. E., Halliday, J., Snaar, J. E. M., Morris, P. G. & Taylor, R. (2003) 284, E688-E694. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Shulman, G. I., Rothman, D. L., Jue, T., Stein, P., DeFronzo, R. A. & Shulman, R. G. (1990) N. Engl. J. Med. 322, 223-228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rothman, D. L., Magnusson, I., Cline, G., Gerard, D., Kahn, C. R., Shulman, R. G. & Shulman. G. I. (1995) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92, 983-987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Perseghin, G., Price, T. B., Petersen, K. F., Roden, M., Cline, G. W., Gerow, K., Rothman, D. L. & Shulman, G. I. (1996) N. Engl. J. Med. 335, 1357-1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lawrence, J. C. & Roach, P. J. (1997) Diabetes 46, 541-547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roden, M., Price, T. B., Perseghin, G., Petersen, K. F., Rothman, D. L., Cline, G. W. & Shulman, G. I. (1996) J. Clin. Invest. 97, 2859-2865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Petersen, K. F., Hendler, R., Price, T., Perseghin, G., Rothman, D. L., Held, N., Amatruda, J. M. & Shulman, G. I. (1998) Diabetes 47, 381-386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Petersen, K. F. & Shulman, G. I. (2002) Am. J. Cardiol. 90, 11G-18G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]