Abstract

Objectives

To examine the benefits, limitations and ethical issues associated with conducting participatory research on tobacco use using youth to research other youth.

Study design

Community-based participatory research.

Methods

Research on tobacco use was conducted with students in the K’àlemì Dene School and Kaw Tay Whee School in the Northwest Territories, Canada, using PhotoVoice. The Grade 9–12 students acted as researchers. Researcher reflections and observations were assessed using “member checking,” whereby students, teachers and community partners could agree or disagree with the researcher's interpretation. The students and teachers were further asked informally to share their own reflections and observations on this process.

Results and conclusions

Using youth to research other youth within a participatory research framework had many benefits for the quality of the research, the youth researchers and the community. The research was perceived by the researchers and participants to be more valid and credible. The approach was more appropriate for the students, and the youth researchers gained valuable research experience and a sense of ownership of both the research process and results. Viewing smoking through their children's eyes was seen by the community to be a powerful and effective means of creating awareness of the community environment. Limitations of the approach were residual response bias of participants, the short period of time to conduct the research and failure to fully explore student motivations to smoke or not to smoke. Ethical considerations included conducting research with minors, difficulties in obtaining written parental consent, decisions on cameras (disposable versus digital) and representation of all participants in the final research product.

Keywords: youth, participatory research, northern Canada, Aboriginal, First Nations, PhotoVoice, tobacco

The need to give youth a “voice” in the issues affecting their lives has received increasing recognition since the adoption of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child in 1989 (1). However, the degree of participation that should be afforded to youth in discussing, understanding, communicating or making decisions about these issues remains contentious. Although the historic viewpoint that “matters affecting children should be left to the grown-ups” is changing, many still feel that youth should be passive rather than active participants in addressing these issues (2).

There are various ways that youth participation can be realized. Hart's “ladder of participation” for youth (2) [adapted from that originally developed by Arnstein (3) for adult participation] purports that there are 8 escalating degrees of participation, ranging from non-participation (manipulation, decoration and tokenism) to true participation (from provision of information to youth initiated shared decisions with adults). Variations of this model involve 5 steps ranging from listening to youth to involving them in decision making (4).

Involving youth directly in research on relevant issues is a major means of promoting “real” participation. Participatory research approaches have been advocated as the most appropriate means of engaging youth in a process of analysis and reflection that can lead to the ability to participate in decision making (2,5). This type of research further allows for youth agency or youth as social actors (6). Engaging youth as researchers in community-based participatory research studies has been shown to have benefits for the youth, their communities and the quality of the research (7–9).

Participatory research is often accomplished using visual methods, such as PhotoVoice. PhotoVoice is a potentially powerful research method where individuals are given an opportunity to take photographs, discuss them individually and/or collectively and use them to create opportunities for personal and/or community change (10). Developed by Wang and Burris (11,12), the method was designed for use with individuals and groups who are traditionally disenfranchised and without a voice and is, therefore, particularly appropriate for youth (7). PhotoVoice has been successfully employed with a wide range of people, communities, issues and geographic settings, including northern Aboriginal populations (13–15) and youth (8,16–21). However, only a few PhotoVoice projects have involved youth directly as researchers (22–24).

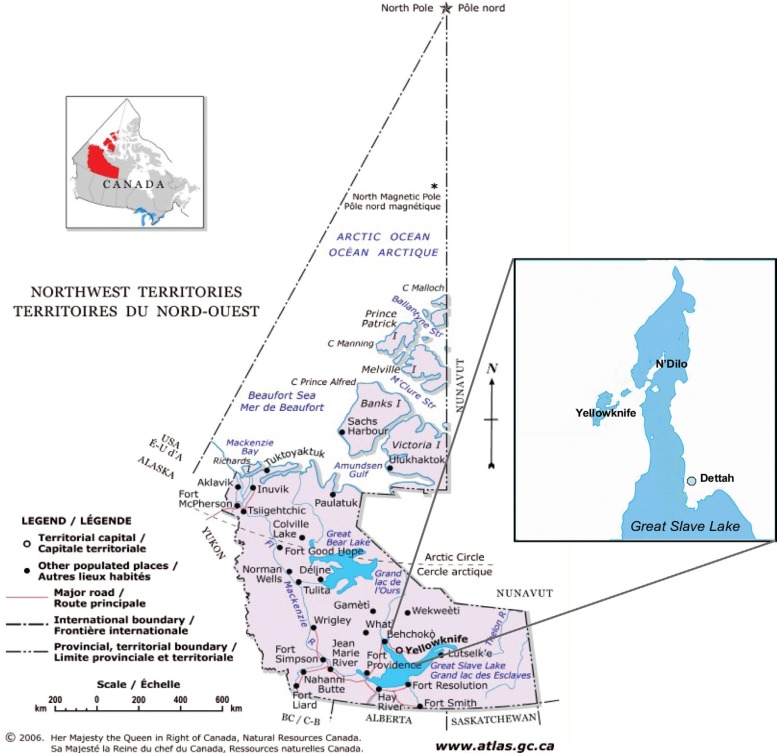

A community-based participatory research project on tobacco use was conducted using PhotoVoice with the students of the K’àlemì Dene School and Kaw Tay Whee School in the Yellowknives Dene First Nation communities of Ndilo and Dettah in the Northwest Territories, Canada (Fig. 1). The K’àlemì Dene School is a community centered school that honours and celebrates the traditions, language and culture of the Dene people. Founded in 1998 as a Kindergarten to Grade 3 school for approximately 15 students, the K’àlemì Dene School now offers education from Kindergarten to Grade 12 to 115 students. The school moved to a newly erected building in the fall of 2009 and proudly graduated its first group of students in June 2010.

Fig. 1.

Location of the study communities in the Northwest Territories (Reproduced with the permission of Natural Resources Canada 2012, courtesy of the Atlas of Canada).

Previous research in these communities (25) had shown that while 94% of people surveyed knew that smoking was bad for their health, 56% currently smoked (n = 50). Most alarming to the community was the finding that 11% of smokers had started at 10 years old or younger and 71% had started between 11 and 18 years of age. Youth smoking was thus recognized by the community as an important health issue requiring further research, driving the development of this study. Smoking is generally a problem for Aboriginal Canadians, with the rate of smoking among First Nations people (59%) still approximately 3 times the rate for the general Canadian population (26). The rate among Aboriginal boys (47%) and girls (61%) aged 15–17 years is also much higher than the national rate for this age group (20%) (27). Young adults (aged 18–29 years) have the highest proportion of daily smokers (54%). Smoking rates amongst Aboriginal youth tend to be higher in more remote communities (up to 82% for those aged 15–19 years) (28). In the Northwest Territories, Aboriginal youth aged 10–14 years are 5 times more likely to be current smokers than non-Aboriginal youth (although this proportion declined to 17% in 2006 from 29% in 1982) (29).

The purpose of this manuscript is to examine the benefits and limitations of conducting community-based participatory research on tobacco use using youth to research other youth in a northern Canadian First Nations community. Ethical issues that arose during the course of the research are also discussed. It is a reflection on the process used for a research project designed to better understand: (a) what youth know and understand about tobacco use; (b) how they view tobacco use in their community; and (c) what influences their decisions to start smoking or not to start smoking. The results for this research will be reported elsewhere.

Methods

Although this article is an examination of the process used in a research study, the methods used to conduct the research are described here to provide overall context for the results and discussion and to illustrate the participatory nature of the research. The qualitative process used for reflection on and assessment of this particular participatory method is also provided.

Data collection

The research was conducted from January to March 2009. It was designated part of the health curriculum at the K’àlemì Dene School. Ten students in the Grade 9–12 cohort were trained as researchers and conducted interviews with students in Grades 2–12 at the K’álemi Dene School and students in Grades 2–6 at the neighbouring Kaw Tay Whee School (Fig. 1). Ethical permission to conduct the research was obtained through the Health Research Ethics Board (Panel B) of the University of Alberta. In addition, a Northwest Territories (NWT) Scientific Research Licence was obtained through the Aurora Research Institute.

Research training was done by members of the research team (including academic, community and government members) and school staff (teacher and principal). Information was provided on the research process, from concept through to analysis and interpretation. This included the fundamentals of research ethics, creating interview questions, conducting interviews (including providing information to participants and obtaining consent) and using the digital recording equipment. The class collectively developed the script for the initial interview on smoking knowledge and behaviours and the briefing for the PhotoVoice method. The high school students then conducted “practice” interviews with the researchers and teachers to make all participants more comfortable with the process and equipment.

At the start of the interview, the student researchers described the project for the participants and informed them that the interviews would be audio recorded, how their confidentiality would be maintained and how the information would be used. Even though parental/guardian permission was obtained, further oral assent to participate in the research was sought from the students. The interview questions, as developed by the youth researchers, are shown in Table I.

Table I.

Interview questions designed by youth researchers

| Do you smoke? | |

|---|---|

No

|

Yes

|

A total of 48 students ranging in age from 7 to 19 years were interviewed. Most of the students were Dene, although a few students were of other ethnicity. The students all spoke English: although Dogrib is taught in the school, few if any of the students are fluent in this language. All students attending school during the 2 days in which interviews were conducted and who assented to being part of the project participated in the research.

At the end of the interview, participants were briefed on the PhotoVoice method and provided with disposable cameras. They were given the general assignment to take pictures of tobacco use in their community. The PhotoVoice briefing involved ensuring that ethical issues related to the use of PhotoVoice were addressed (30) and was based on the following instructions to the researchers about advising the participants of specific considerations:

Ask people's permission before you take their picture. Make sure you know their name in case we need to ask them later if we can use the picture in a presentation or report.

Do not put yourself and anyone else in danger to take a picture. For example, do not stand on a wobbly chair to take a picture.

Do not take pictures that might embarrass someone or make them feel bad.

Of the 48 cameras distributed, 33 were returned for processing and 27 follow-up interviews were conducted. The student researchers again collectively decided on the semistructured guide for the PhotoVoice interviews (Table II). Some very innovative questions for coaxing shyer younger students to discuss their pictures were developed by the student researchers, including “What title would you put on this picture?” and “Can you give me 2 words to describe this picture?”

Table II.

PhotoVoice interview questions designed by youth researchers

|

Data analysis and dissemination

The pictures and accompanying words were assembled and presented back to the student researchers for discussion and analysis. Relevant themes were determined through iterative discussions between the students, teachers and researchers on the meaning and relevance of the photographs. It was collectively decided to assemble a book to showcase the student pictures and words.

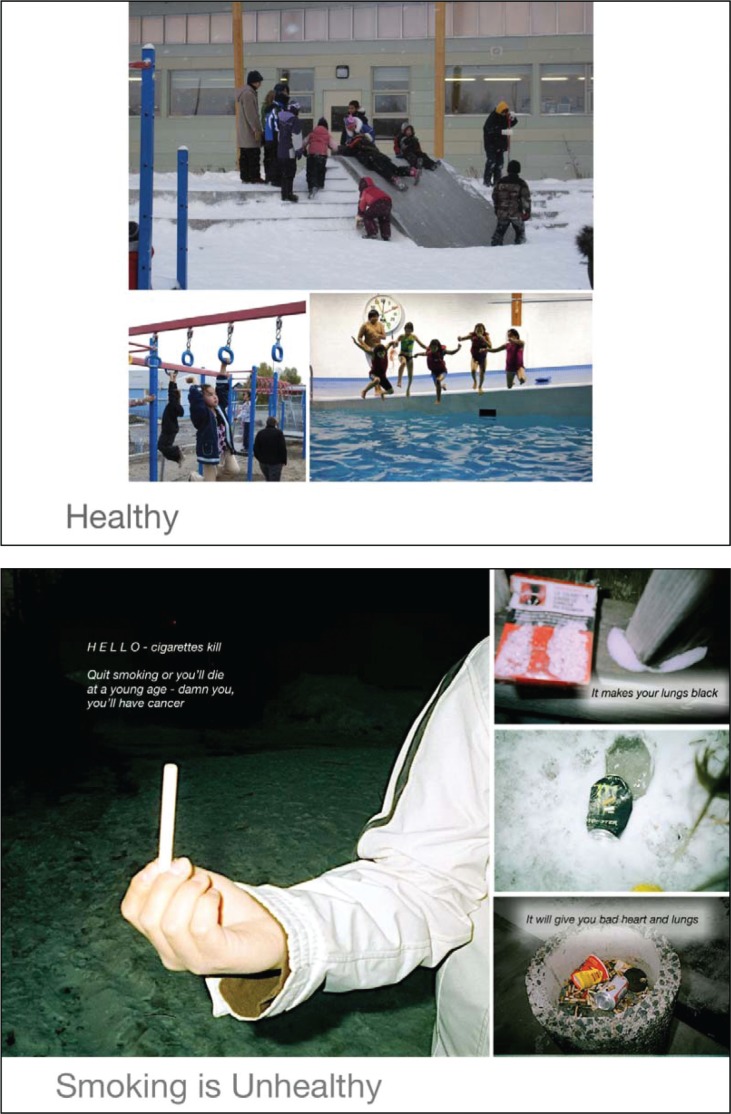

One student precociously pointed out that all of the pictures involved negative aspects of each theme and that perhaps the final portrayal of the results should pair the “negative” photos with “positive” depictions related to that theme. For example, pictures for the theme “Smoking is Unhealthy” were paired with pictures on “Healthy” activities (Fig. 2). Based on their experiences and understanding (both as members of an Aboriginal community and as youth), the students also decided that 2 further themes were needed for the book: one showing the traditional use of tobacco and one on why students choose to smoke or not to smoke. The additional pictures required for the positive portrayals and for the new themes were either taken by the student researchers or obtained from school photograph galleries. All decisions on the photographs to be used in the book were made jointly between the academic researcher and the student researchers.

Fig. 2.

An example of the pairing of a “negative” theme and “positive” theme in the results booklet “Youth Voices on Tobacco”.

The final book of pictures with selected accompanying words was produced as an iBook™ on an Apple™ computer. The book was entitled Youth Voices on Tobacco. A student researcher worked with the academic researcher to select the pictures for the book and decide how these should be portrayed. At least 1 picture from every student who participated in the PhotoVoice project was included. Written permission was obtained from the individuals shown in the pictures. The book was distributed to all students of the K’àlemì Dene School and the Kaw Tay Whee School. Books were also distributed to every family in the communities of Ndilo and Dettah through a regular band council mail out.

Evaluation

The methods used for research evaluation must be appropriate to the research paradigm (31). Traditional quantitative conceptualizations of evaluation are generally acknowledged to be unsuitable for the assessment of qualitative research (32). Instead, qualitative evaluations are more aptly based on established qualitative methods such as reflection, observation and interpretation of meaning. Within a participatory research process, this type of evaluation must be both an individual and cooperative undertaking: while the assessment may be subject to analysis and interpretation by the researcher, it must also remain true to the information provided by and understanding of the other research participants (33).

The assessment of the benefits and limitations of conducting community-based participatory research using youth as researchers was based on this type of qualitative evaluation approach. The researcher's reflections on the process were based on observations of the student researchers, student participants, teachers and community members. These observations were evaluated using “member checking,” whereby students, teachers and community partners were given the opportunity to agree or disagree with the researcher's interpretation through informal one-on-one and class discussions. Member checking is an established means of assessing credibility in qualitative research. It is considered analogous to an evaluation of internal validity in quantitative assessment, only instead of seeking to establish confidence in the “truth” of the findings, the intent is to focus on the degree to which findings “make sense” (34). The student researchers and teachers were further asked to informally share their own reflections and observations on this process, thus making the assessment process reciprocal and dialogic.

In this assessment, comparisons are inevitably made against assumptions of an alternative process (i.e. if the academic researchers had planned and conducted the research without student involvement). Although it is obviously impossible to know definitively “what would have happened if …”, it is possible to use experiential knowledge to make reasonable assumptions about the potential outcomes under this alternate scenario. These assumptions were generally shared by the research participants in discussions about benefits and limitations of this process, adding legitimacy to the comparisons and conclusions.

Results

Benefits of approach

Using youth to research other youth within a participatory research framework had many benefits for the quality of the research, the youth researchers and the community. From a research perspective, more valid and credible results were obtained. Students were obviously more comfortable talking with older, familiar students instead of adult “outsider” researchers, and were consequently more candid about talking about smoking behaviours without the anticipated disapproval of an authority figure. Although this result is obviously very difficult to prove empirically (particularly in a qualitative study), it is substantiated by comments made by the student researchers and through observations made by the academic researchers in reviewing the audio transcripts.

The research design and implementation benefited greatly from the collective approach between research team members and youth researchers. As a result of the overall participatory process, one of the community research team members even quit smoking to act as a role model for the project. The research instruments designed by the youth researchers provided unique interview approaches and questions that were better suited to both the age and cognitive processing of the participants.

The final book on Youth Voices on Tobacco was significantly enhanced by the youth researchers’ ideas and the additional photographs they provided. Students, teachers and community partners commented that pairing the negative pictures with positive depictions of “how things should be” greatly increased the impact of the book by providing a constructive and optimistic perspective on each theme. Psychological theories of knowledge, attitudes and behaviours support the concept that the favourability of messages, as determined through past experiences and worldviews, may affect the type and tendency of cognitive processing used to determine thoughts and actions (35,36). Negative messages that elicit unfavourable thinking, while sometimes necessary to increase knowledge and consideration of tobacco issues, may actually decrease persuasion to change smoking behaviours or community conditions, even if the message is understood (37). Coupling of negative and positive messages thus provides both information and affective cues that are more likely to result in desired attitude and/or behaviour changes related to smoking. In addition, a book based on youth-generated pictures with obvious youth input was of more compelling interest for the community. Many people commented that viewing the stories created by their youth and situated in their own environment resulted in a very relevant and powerful message.

Everyone involved described the research as a positive experience. It has led to pursuing options for additional collaborative research in this area, using a new cohort of students as researchers. Additionally, as a result of the youth researchers interacting within their community, it has raised awareness of tobacco use and helped both the youth researchers and the community to consider possible steps towards changing to healthier lifestyle choices.

Youth researchers benefited from exposure to the research process and the wonders of exploration and learning. They developed research skills and leadership abilities, which empowered several of them in terms of their future success – 3 of the 4 student researchers who graduated that year returned to work with the school the next year as teacher aides. As true participants in the research, the students exhibited a definite sense of ownership of both the research process and the final research product. These qualities have the potential for encouraging sustained interest in contributing to changes in community tobacco use – individual skill building, participation and empowerment were shown to facilitate active youth involvement in a long-term, tobacco-related community change in another study (38). Finally, there was evidence from the class discussions of the pictures and words that participation in this research encouraged student critical appraisal of an apparent shared cognitive dissonance (39) between smoking knowledge and smoking behaviours (while all students knew and understood the health implications of smoking, the majority of the Grade 9–12 cohort participating as youth researchers smoked). This is the first step in evoking personal self-examination of motivations and awareness of individual power to make positive health choices, which may in turn lead to changed behaviours and community action.

For the community, viewing smoking through their children's eyes was stated by many to be a much more powerful and potentially influential message than a report generated by outside researchers. The photographs and words produced by the youth are known to have garnered community interest. These visual messages will hopefully result in raised awareness of the community conditions that are contributing to the high prevalence of smoking amongst youth, as has been demonstrated in other youth PhotoVoice projects (8). In general, it was found that smoking was ubiquitous in the community and that most students had family members and friends who smoked. The long standing cycle of addiction related to smoking is very strong in many northern communities: if youth see everyone around them smoking, they are more likely to view smoking as a normal behaviour. This research project and the resulting book of photographs is the first step in prompting community recognition that a prevalent smoking environment will only lead to the negative outcome of more and younger new smokers (40).

Limitations of approach

Despite the fact that having youth researchers undoubtedly increased the accuracy of the results, there was still an obvious response bias in the research, with many students providing the “correct” response that they do not smoke regardless of their actual behaviour. While only 6 of the participants indicated they currently smoke in the interviews, at least 9 of 12 students in the Grade 9–12 cohort were later observed to be regular smokers. This discrepancy may be related to the desire to provide the researchers with the “acceptable” answer that would meet with the approval of the teachers.

To accommodate school scheduling, only a short period of time was available for the research. The research training and initial interviews were conducted in 2 days. Students were given 1–2 days to take pictures, thereby limiting opportunities and possible creativity. The younger participants tended to take pictures that were “convenient”; it was amusing to see swarms of children taking pictures of cigarette butts on the ground in the area around the school on the day the cameras were distributed. This is consistent with behaviours of young participants in other PhotoVoice projects (8,17,19). Time restrictions also limited relationship building with the youth researchers and the academic research team, which would have led to more open and honest opportunities to discuss some complex and sensitive issues in more depth. Based on their experiences with a related youth PhotoVoice project on childhood obesity, Findholt et al. (8) recommend a thorough project orientation that goes beyond a discussion of cameras and photographic ethics and helps youth to understand how community context can affect health. This type of discussion might have been useful in this study to further explore the interpretation of the pictures and the possibilities for community action.

Even though the research was deemed a “success” by everyone, it did fail to completely address the research study objective related to student decision making on smoking or not smoking. This objective had arisen from a comment made by a Yellowknife teacher on “how does it go from being ‘gross and yucky’ to students in Grade 4, to having students in Grade 5 smoking in the schoolyard?” While it had been thought this theme might arise naturally in the choice of pictures taken by the participants, it was not directly apparent in the original set of pictures. Although the youth researchers decided to explore this theme specifically for the book with additional pictures, it still proved difficult to fully understand motivations for smoking and not smoking. In hindsight, participants should have been provided with more specific instructions to take pictures related to this theme.

Ethical challenges and considerations

Research involving children and youth raises specific ethical issues, primarily related to concerns regarding competence, autonomy and vulnerability. Parental consent is thus required (41). Although the school had obtained blanket parental consent for school activities (allowing all students to participate in the research), specific consent was required to use the research results. Obtaining written consent is problematic in many northern Aboriginal communities as it “may be seen as contrary to respecting Aboriginal approaches to research initiatives” (42, p. 21). Determining who is responsible for granting consent for minors is also difficult in communities where current guardianship is often not formally recognized. Information sheets and consent forms were sent home with all student participants, and written consent was obtained from approximately one-third of the parents/guardians. The teacher then phoned all other parents/guardians to explain the study and obtain verbal consent for the remaining students. Verbal assent was also obtained from each student participant prior to conducting the interviews, as the researchers strongly believed that this was necessary to respect the rights of the individual.

An additional ethical consideration involved the types of cameras used in the research. It had originally been planned to use digital cameras that could be deployed successively amongst the students. However, at the request of the teacher, disposable cameras were used instead. The teacher made the very compelling case that the research should foster feelings of success in the students; if a valuable camera was lost or stolen, requiring an investigation and possible blame, success could be quickly compromised and the positive experience of the research negated.

A final ethical concern involved representation. It was considered very important that all participants should be able to “see” themselves in the final research product. Care was thus taken that at least 1 photograph from each participant was included in the final book Youth Voices on Tobacco.

Discussion and Conclusions

Using youth to research youth proved to be a successful strategy for exploring youth knowledge of the health concerns related to smoking and the role of tobacco use in their community. Perhaps more importantly, the research proved valuable in providing the community with a lens through which to view how youth see smoking in their environment. Unfortunately, the traditional use of tobacco for spiritual purposes has been radically changed to the modern addiction to tobacco, which has caused negative health issues for many youth and community members (43). This research methodology was thus an effective way to reach the community, have them reflect on the changes in tobacco use and promote awareness of the need for environmental change, while simultaneously engendering development of youth research skills and abilities (8).

The research approach was also important in promoting the view of “youth as resources” as opposed to the commonly portrayed image of “youth as problems” (44). This asset-based perspective has to be strengthened as a methodology to work with youth if any changes are to continue. If the adult expectations of youth (which are inevitably reflected in youth behaviours) can be changed, youth may come to believe in themselves as agents of change rather than troublemakers (43). However, realizing this vision will require a commitment to creating openings, opportunities and obligations for continued youth participation in the issues that affect their lives (4). It must also be accompanied by a continued focus on enabling youth action through involvement in decisions and policy making (45). Having youth actively involved in research that affects their lives and opens their eyes to tobacco-related health issues provides them with potential opportunities to pursue real community change. As the future generation, they are also the carriers of the traditions and culture and need to bring forth healthy attitudes towards tobacco's spiritual purposes, not its negative effects related to addictions and adverse health outcomes (43).

Finally, this approach successfully met the specific requirements of community-based participatory research (46). Co-learning and reciprocal transfer of expertise was achieved by all research partners. The youth researchers learned research skills, while the research team partners learned valuable lessons on structuring research and dissemination products that were more appropriate, effective and powerful for the student participants and community. Shared decision-making was an integral part of the research, ranging from initial decisions on the research concept and design to the final decisions on dissemination. This led to mutual ownership of the processes and products of the research enterprise. Based on this research, youth assuming a partnership role in research activities presents fruitful ground for continued advances in making positive health changes in northern Aboriginal communities.

Acknowledgements

Funding for this research was provided by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research through the Institute for Aboriginal Peoples’ Health. The research team for this project included Alice Abel (Director of Community Services, Yellowknives Dene First Nation), Miriam Wideman (Health Promotion Specialist, Government of the Northwest Territories), Aggie Brockman (Consultant, Yellowknife) and Louise Beaulieu (Community Fieldworker, Yellowknives Dene First Nation). This research could not have been completed without the wonderful teachers at the K’àlemì Dene School (Eileen Erasmus, David Ryan, Angela Gallant and Kevin Laframboise) and, of course, the youth researchers (Shalbe Betsina, Bobbie-Jo Black, Emily Black, Justina Black, Jeremy-Joe Franki, Ernest Franki-Sangris, Kelsey Martin, Christal Sangris, Kirsten Sangris and Kyra Sangris).

Conflict of interest and funding

The authors have not received any personal funding or benefits from industry or elsewhere to conduct this research.

References

- 1.United Nations. Geneva: United Nations Human Rights, Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights; 1989. United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. [cited 2011 June 2]. Available from: http://www2.ohchr.org/english/law/pdf/crc.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hart R. Florence: UNICEF International Child Development Centre; 1992. Children's participation: from tokenism to citizenship. [cited 2011 June 2]. Available from: http://www.unicef-irc.org/publications/pdf/childrens_participation.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arnstein S. A ladder of citizen participation. J Am I Planners. 1969;35:216–24. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shier H. Pathways to participation: openings, opportunities and obligations. Child Soc. 2001;15:107–17. [Google Scholar]

- 5.MacDonald JA, Gagnon AJ, Mitchell C, Di Meglio G, Rennick JE, Cox J. Include them and they will tell you: learnings from a participatory process with youth. Qual Health Res. 2011;21:1127–35. doi: 10.1177/1049732311405799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mason J, Hood S. Exploring issues of children as actors in social research. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2011;33:490–5. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang CC. Youth participation in photovoice as a strategy for community change. J Commun Prac. 2006;14:147–61. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Findholt NE, Michael YL, Davis MM. Photovoice engages rural youth in childhood obesity prevention. Public Health Nurs. 2010;28:186–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.2010.00895.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheney KE. Children as ethnographers: reflections on the importance of participatory research in assessing orphans’ needs. Childhood. 2011;18:166–79. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Linnan LA, Lopez M, Moore DS, Daniel M, McAlister E, Wang C. Power of Photovoice: Voices of the ‘voice-less’ in the aftermath of Hurricane Floyd. Abstract #27096. Atlanta: The 129th Annual Meeting of the American Public Health Association; 2001. [cited 2011 June 2]. Available from: http://apha.confex.com/apha/129am/techprogram/paper_27096.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang C, Burris MA. Empowerment through Photo Novella: portraits of participation. Health Educ Q. 1994;21:171–86. doi: 10.1177/109019819402100204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang CC, Burris MA. Photovoice: concept, methodology, and use for participatory needs assessment. Health Educ Behav. 1997;24:369–87. doi: 10.1177/109019819702400309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moffitt P, Vollman AR. Photovoice: picturing the health of aboriginal women in a remote northern community. Can J Nurs Res. 2004;36:189–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Castleden H, Garvin T. Huu-ay-aht First Nation. Modifying Photovoice for community-based participatory Indigenous research. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66:1393–405. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Healey GK, Magner KM, Ritter R, Kamookak R, Aningmiuq A, Issaluk B, et al. Community perspectives on the impact of climate change on health in Nunavut, Canada. Arctic. 2011;64:89–97. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang CC, Morrel-Samuels S, Hutchison PM, Bell L, Pestronk RM. Flint photovoice: Community building among youths, adults, and policymakers. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:911–3. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.6.911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Strack RW, Magill C, McDonagh K. Engaging youth through photovoice. Health Promot Pract. 2004;5:49–58. doi: 10.1177/1524839903258015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilson N, Dasho S, Martin AC, Wallerstein N, Wang CC, Minkler M. Engaging young adolescents in social action through photovoice: the Youth Empowerment Strategies (YES!) Project. J Early Adolesc. 2007;27:241–61. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vaughn LM, Rojas-Guyler L, Howell B. “Picturing’’ health: a photovoice pilot of Latina girls’ perceptions of health. Fam Commun Health. 2008;31:305–16. doi: 10.1097/01.FCH.0000336093.39066.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gant LM, Shimshock K, Allen-Meares P, Smith L, Miller P, Hollingsworth LA, et al. Effects of photovoice: civic engagement among older youth in urban communities. J Commun Prac. 2009;17:358–76. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Woodgate RL, Leach J. Youth's perspectives on the determinants of health. Qual Health Res. 2010;20:1173–82. doi: 10.1177/1049732310370213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Foster-Fishman PG, Law KM, Lichty LF, Aoun C. Youth ReACT for social change: a method for youth participatory action research. Am J Commun Psychol. 2010;46:67–83. doi: 10.1007/s10464-010-9316-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Green E, Kloos B. Facilitating youth participation in a context of forced migration: a Photovoice project in northern Uganda. J Refug Stud. 2009;22:461–82. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wilson N, Minkler M, Dasho S, Carillo R, Wallerstien N, Garcia D. Training students as facilitators in the Youth Empowerment Strategies (YES!) project. J Commun Prac. 2006;14:201–17. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jardine CG, Furgal C. Ottawa: Health Canada Health Policy Research Program; 2006. Factors affecting the communication and understanding of known and potential/theoretical risks to health in northern Aboriginal communities; p. 178. + App. [Google Scholar]

- 26.First Nations Information Governance Centre. Ottawa: First Nations Information Governance Centre; 2005. First Nations Regional Longitudinal Health Survey (RHS) 2002/03. [cited 2011 June 2]. Available from: http://www.rhs-ers.ca/sites/default/files/ENpdf/RHS_2002/rhs2002-03-technical_report.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Health Canada. Ottawa: Health Canada; 2004. Canadian Tobacco Use Monitoring Survey (CTUMS) 2004. [cited 2011 June 2]. Available from: http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/hc-ps/tobac-tabac/research-recherche/stat/ctums-esutc_2004-eng.php. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Retnakaran R, Hanley AJG, Connelly PW, Harris SB, Zinman B. Cigarette smoking and cardiovascular risk factors among Aboriginal Canadian youths. CMAJ. 2005;173:885–9. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.045159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Government of the Northwest Territories Health and Social Services. Yellowknife: Government of the Northwest Territories Health and Social Services; 2009. Youth smoking in the NWT: a descriptive summary of smoking behaviour among Grades 5 to 9 students. [cited 2011 June 2]. Available from: http://www.hlthss.gov.nt.ca/pdf/reports/tobacco/2009/english/youth_smoking_in_the_nwt.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang CC, Redwood-Jones Y. Photovoice ethics: perspectives from flint photovoice. Health Educ Behav. 2001;28:560–72. doi: 10.1177/109019810102800504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Horsburgh D. Evaluation of qualitative research. J Clin Nurs. 2003;12:307–12. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2702.2003.00683.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guba EG, Lincoln YS. Fourth generation evaluation. Newbury Park: Sage; 1989. p. 294. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Daly K. Re-placing theory in ethnography: a postmodern view. Qual Inq. 1997;3:343–65. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic inquiry. Newbury Park: Sage; 1985. p. 419. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eagly A, Chaiken S. The psychology of attitudes. Orlando: Harcourt Brace-Jovanovich, Inc; 1993. p. 794. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Greenwald AG. Cognitive learning, cognitive response to persuasion, and attitude change. In: Greenwald AG, Brock TC, Ostrom TM, editors. Psychological foundations of attitudes. San Diego: Academic Press; 1968. pp. 147–70. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Petty RE, Cacioppo JT, Goldman R. Personal involvement as a determinant of argument-based persuasion. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1981;41:847–55. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ross L. Sustaining youth participation in a long-term tobacco control initiative: consideration of a social justice perspective. Youth Soc. 2011;43:681–704. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Festinger L. A theory of cognitive dissonance. Evanston: Row, Peterson; 1957. p. 293. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Varcoe C, Bottorff JL, Carey J, Sullivan D, Williams W. Wisdom and influence of elders: possibilities for health promotion and decreasing tobacco exposure in First Nations communities. Can J Public Health. 2010;101:154–8. doi: 10.1007/BF03404363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Morrow V, Richards M. The ethics of social research with children: an overview. Child Soc. 1996;10:90–105. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Canadian Institutes of Health Research. CIHR guidelines for health research involving Aboriginal people. Ottawa: Canadian Institutes of Health Research; 2007. p. 44. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Godel J. Use and misuse of tobacco among Aboriginal peoples – Update 2006. Paediatr Child Health. 2006;11:681–5. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Checkoway BN, Gutierrez LM. Youth participation and community change: an introduction. J Commun Prac. 2006;14:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Suleiman AB, Soleimanpour S, London J. Youth action for health through youth-led research. J Commun Prac. 2006;14:125–45. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Viswanathan M, Ammerman A, Eng E, Gartlehner G, Lohr KN, Griffith D. AHRQ Publication No. 04-E022-2. Rockville: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, US Department of Health and Human Services; 2004. Community-based participatory research: assessing the evidence; p. 109. +App. [Google Scholar]