Abstract

The intramacrophage protozoan parasites of Leishmania genus have developed sophisticated ways to subvert the innate immune response permitting their infection and propagation within the macrophages of the mammalian host. Several Leishmania virulence factors have been identified and found to be of importance for the development of leishmaniasis. However, recent findings are now further reinforcing the critical role played by the zinc-metalloprotease GP63 as a virulence factor that greatly influence host cell signaling mechanisms and related functions. GP63 has been found to be involved not only in the cleavage and degradation of various kinases and transcription factors, but also to be the major molecule modulating host negative regulatory mechanisms involving for instance protein tyrosine phosphatases (PTPs). Those latter being well recognized for their pivotal role in the regulation of a great number of signaling pathways. In this review article, we are providing a complete overview about the role of Leishmania GP63 in the mechanisms underlying the subversion of macrophage signaling and functions.

Keywords: Leishmania, GP63, macrophage, signaling, host-pathogen interaction, innate immunity

Introduction

Parasites have always showed the greatest ingenuity when it is time to infect their host, to survive and propagate, and the parasite Leishmania is clearly champion in this matter. Actually, it is known that Leishmania can utilize various surface proteins, recognized as potential virulence factors [e.g., glycosilinositolphospholipids (GIPLs), lipophosphoglycan (LPG), cysteine protease, GP63], to thwart the host macrophage defense system and therefore, permitting its survival and progression within the harsh environment of the phagolysosome (Chang and McGwire, 2002). Interestingly, one of them, the metalloprotease GP63, is more and more seen as a critical one (Chaudhuri et al., 1989; Joshi et al., 2002; Yao et al., 2003).

GP63 was first discovered in 1980s, being described as a major surface antigen expressed on Leishmania promastigotes from various species (Fong and Chang, 1982; Bouvier et al., 1985; Etges et al., 1985; Chang et al., 1986). Due to its glycosylation state, this Leishmania surface protein (60–66 kDa), also showing capacity to bind to concanavalin A, was named GP63 (Bouvier et al., 1985; Chang et al., 1986; McGwire and Chang, 1996). Initially, GP63 was described to have protease activity, so named major surface protease (MSP), and later on, specified as a zinc-metalloprotease (Etges et al., 1986; Chaudhuri and Chang, 1988; Bouvier et al., 1989; Chaudhuri et al., 1989). Because of this property, GP63 was then name leishmanolysin by the IUBMB (International Union of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology) Enzyme Nomenclature. This metalloprotease is present not only in different species of Leishmania, but also in various Trypanosoma species (sps) and Trichomonas vaginalis (Etges et al., 1985; Bordier et al., 1986; Ma et al., 2011a,b).

In the following sections of this review, we will report in details what is GP63 and how this Leishmania virulence factor influences the host innate immune system at cellular and molecular levels concurring to its establishment, survival, and propagation within mammalian macrophages.

Genomic organization, expression, and structure

Genome sequence study of L. major showed that genes encoding GP63 (msp) are organized in a tandem array (four copies) on the chromosome 10, a single msp on the chromosome 28 and another related gene on the chromosome 31 (Ivens et al., 2005). Similar organization of msp was found in L. infantum and L. braziliensis genome which consist in 5 and 33 genes, respectively, in the chromosome 10, as well as 3 and 6 msp-like in the chromosome 28 and/or 31 (Peacock et al., 2007). Previous studies using Southern blots also demonstrated the tandem pattern of msp, however, there are some contradiction in the numbers of copies/parasite with the genome sequence results. Nevertheless, those studies demonstrated that expression of msp products varies with growth phase and life cycle form of Leishmania. Accordingly with mRNA expression during growth phase, L. chagasi msp (>18 copies) were found to be organized in three classes mspL, S, and C. mspS has 5 alleles mspS-1 to -5 and their products are mainly expressed in stationary phase. On the other hand, products of mspL-1 to -12 are expressed in the logarithmic phase. Finally, a constitutively expressed mspC RNA seems to generate a GP63 transmembrane form (Roberts et al., 1993).

Differential expression of msp products is also demonstrated during Leishmania life cycle. For instance, L. mexicana msp genes (10 copies) were separated in clusters C1, C2, and C3. Products from all msp clusters are found in promastigotes, however, amastigotes only expresses GP63 from C1 msp cluster (Medina-Acosta et al., 1989). Additionally, GP63 from L. major msp genes 1–5 are expressed only in promastigotes, gene 6 in both promastigote and amastigote, and gene 7 solely in amastigote stage or in late promastigote stationary phase (Kelly et al., 2001). These great numbers of GP63 genes generate abundant proteins that can vary among species and life forms of Leishmania leading to different biological effect, as we will discuss later on.

GP63 protein synthesis is processed via endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and secretory pathway by vesicles trafficking (Ellis et al., 2002; McGwire et al., 2002; Yao et al., 2002). It can be found intracellularly in ER (∼1.5%), but in great proportion expressed on parasite surface (∼75%), and the rest is released under secreted form or membrane cleaved (Weise et al., 2000; Ellis et al., 2002; McGwire et al., 2002). Secreted GP63 can have different ranges of molecular weight because of their glycosylated states important for the secretion being independent of glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchor (Ellis et al., 2002) and whether they are bearing a GPI anchor. Release of GPI-anchored GP63 is independent on glycosylation, but dependent on auto-proteolysis, as the presence of a zinc chelator, 1,10-phenanthroline or mutation of zinc-binding motif did altered GPI-anchored GP63 secretion (McGwire et al., 2002).

During the biosynthesis GP63 has a pro-peptide with a cysteine residue that inactivates the zinc protease activity. This pro-peptide is removed during the protein maturation process. The expression of GP63 on Leishmania surface and its secretion was studied in many aspects relating with its role on the invertebrate and vertebrate host of Leishmania. In the following section of this review, we will now discuss GP63 impact on its host macrophage functions.

Impact of Leishmania GP63 on macrophage signaling and innate immune response

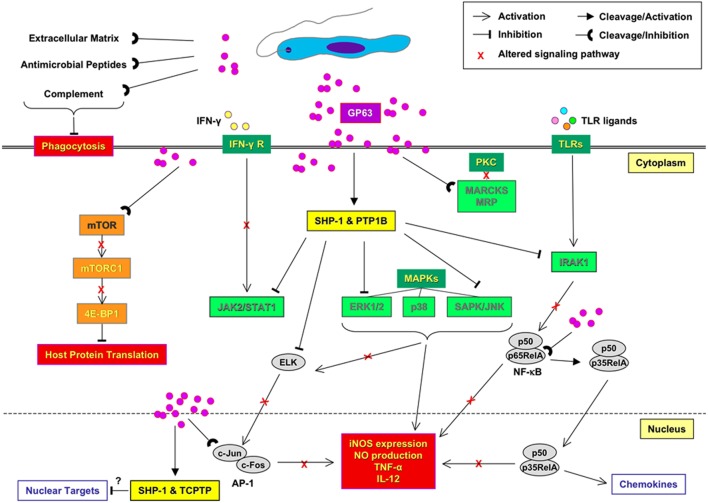

See Figure 1 for schematic representation.

Figure 1.

Impact of Leishmania GP63 on macrophage signaling and innate immune response. Before parasite entries into the host macrophage, GP63 provides parasite resistance to the complement-mediated lysis and facilitate promastigote engulfment by macrophages. Within the host macrophage, GP63 is responsible for the activation of protein tyrosine phosphatases (PTPs; SHP-1, PTP1B, and TCPTP) that lead to the alteration of JAK, MAP, and IRAK-1 kinase pathways. GP63 is also able to down regulate host macrophage protein synthesis by altering mTORC1-dependent signaling. In the nucleus, inactivation of transcription factors, such as AP-1 and NF-κB, involve specific cleavage and degradation of subunits by GP63. Altogether, this signaling inactivation mediated by GP63 inhibits important antimicrobial, thus favoring the survival and propagation of the parasite.

Proteolytic actions of GP63

Upon their transmission to the host, Leishmania parasites are in close contact with its innate immune system. However, Leishmania evolved many mechanisms to escape from innate inflammatory and microbicidal functions of macrophages, and this by altering for instance several key signaling pathways (Olivier et al., 2005). How GP63 is related with the modulation of these events is still under intense investigation.

In this regard, an important finding was that once L. mexicana promastigotes are in contact with the extracellular matrix of subcutaneous tissue, GP63 could degrade extracellular components favoring its rapid migration on matrigel in vitro (McGwire et al., 2003). In addition, this GP63-mediated protein degradation has been also suggested as a key factor concurring to upregulate phosphatase activity in Leishmania-infected macrophages (see below for further discussion), and might also mediate the resistance of Leishmania to antimicrobial peptide.

Accordingly antimicrobial peptides are short cationic peptide able to kill a wide range of microorganism including Leishmania (Mangoni et al., 2005). One proposed mechanism whereby Leishmania can escape the action of those peptides is the GP63-mediated degradation of those latter, as L. major GP63−/− mutants were found to be more susceptible to antimicrobial action (Kulkarni et al., 2006). Recently, host cell nucleosome histones involved in gene transcription where found to have some anti-leishmania property. In fact, Wang et al. (2011) showed that human histones H2A and H2B were able to kill different Leishmania species and to decrease their infectivity. And here again, L. amazonensis promastigotes deficient in GP63 were more susceptible to H2B, while L. major and L. mexicana LPG-knockdown were more resistant (Wang et al., 2011), therefore, further supporting the importance of GP63 to protect Leishmania against adverse conditions. Interestingly, histones are present in the neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs), as well as in many others antimicrobial components including myeloperoxidase, elastase, and defensin (Papayannopoulos and Zychlinsky, 2009). NETs have been implicated in killing of L. amazonensis (Guimaraes-Costa et al., 2009) and L. donovani LPG−/− (Gabriel et al., 2010) promastigotes by neutrophils. However, L. donovani-induced NET formation was shown not to be dependent on GP63 nor LPG expression (Gabriel et al., 2010). In this line of thought, antimicrobial peptides and histones are important for antimicrobial defense of the host that can be avoided by Leishmania expressing GP63.

Resistance to complement-mediated lysis

Complement cascade can be activated by three pathways culminating in the cleavage of C3–C3b. C3b binds to the target serving as opsonin or to help activating other complement pathway components. Microbes opsonized with C3b and C3bi are recognized by complement receptor (CR) 1 (CD35) and CR3 (Cd11/CD18), respectively, consequently being phagocytized and killed by phagocytes (Tosi, 2005). Therefore, complement-mediated lysis of microbes is crucial in innate immunity. Importantly, Leishmania sps. have evolved mechanisms to avoid this complement-mediated killing fashion. Early studies demonstrated an interaction between GP63 and C3, suggesting that GP63 is the acceptor site for C3 deposition (Russell and Wilhelm, 1986; Russell, 1987). Later on, it has been demonstrated that purified GP63 can cleave C3 to its breakdown products C3b (117 kDa), C3bi (68 kDa), and to possibly generate others related catabolites (C3c, C3d, C3e ∼29, and 43 kDa) (Chaudhuri and Chang, 1988). The role of GP63 to cleave C3 was strengthened by using Leishmania overexpressing GP63 or GP63 mutant lacking activity. Leishmania overexpressing proteolytically active GP63 was able to increase the conversion of C3b into C3bi and to reduce the fixation of terminal complement components to Leishmania, consequently increasing their resistance to complement-mediated lysis comparatively to parasite overexpressing inactive GP63 (Brittingham et al., 1995). The resistance to complement-mediated lysis was confirmed with L. major knockout (KO) to msp gene1–6 (expressing GP63 from msp gene 7 on late stationary phase) (Joshi et al., 1998) or 1–7 (Joshi et al., 2002) as well as with antisense-down regulated GP63 in L. amazonensis (Thiakaki et al., 2006); all these Leishmania showed increased sensitivity to complement killing. Additionally, L. amazonensis expressing less GP63 and L. major GP63 KO were found to develop a delayed cutaneous lesion formation in BALB/c mice. However, GP63 (msp gene 1) added-back L. major mutant only partially restored the resistance to complement and lesion size, even with equivalent expression of surface GP63. The latter finding could be explained by a reduced proteolytic activity of the restored GP63 or a defect in its released, which has been tested in detail. Collectively, those studies have however, permitted to firmly establish the protective role of GP63 against complement-mediated lysis of Leishmania parasite.

Promotion of amastigote intra-macrophage survival

Once the promastigote is internalized by phagocytosis, it transforms into a non-flagellated amastigote form, able to survive, and multiply within macrophage phagolysosome. Although the expression (0.1% in amastigote vs. 1% in promastigote), the posttranslational modifications, and the localization (membrane-bound, soluble in cytosol, concentrated in the flagella pocket) differs between both Leishmania life stages, GP63 has been identified in amastigotes of all Leishmania species studied so far (Medina-Acosta et al., 1989; Frommel et al., 1990; Schneider et al., 1992; Ilg et al., 1993; Hsiao et al., 2008). The role of GP63 in amastigotes is still subject to discussion but several evidences support its role in survival of parasite inside the macrophage. Chaudhuri et al. (1989) showed that proteins entrapped in liposomes are protected from phagolysosomal degradation when coated with purified L. mexicana GP63. This protection is lost when GP63 enzymatic activity is annihilated by heat denaturation (Chaudhuri et al., 1989). Another study compared the survival of virulent and attenuated variants of L. mexicana amazonensis inside macrophages phagolysosomes. The low survival rate of the attenuated variants was associated with 20–50-fold reduction in the GP63 surface expression (Seay et al., 1996). In the same idea, Chen et al. (2000) demonstrated that a low GP63 expression induced by specific antisense RNAs in L. amazonensis promastigotes leads to a lower intracellular survival rate (Chen et al., 2000), further confirming that GP63 could play a key role in protecting the intracellular amastigotes in the host macrophages.

Alteration of host macrophage signaling by GP63

The balance between phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of Serine/Threonine/Tyrosine residues on structural and regulatory proteins by kinases and phosphatases respectively, is critical to control intracellular mechanisms in eukaryotic cells. Consequently, Leishmania parasites are particularly effective to hijack host macrophage signaling and antimicrobial functions by exploiting the role of phosphatases as a negative regulator of these pathways (Olivier et al., 2005). GP63 has been directly involved in several of these parasite escaping mechanisms.

Marcks protein and GP63

One of the first molecules involved in signaling and been affected by GP63 is the myristoylated alanine-rich C kinase substrate (MARCKS) and the MARCKS related proteins (MRP), which are protein kinase C (PKC) substrates in diverse cell types, including macrophages (Aderem, 1992; Blackshear, 1993). Expression of MARCKS and MRP is strongly up-regulated in murine macrophages stimulated with bacterial lipopolysaccharide and cytokines (Li and Aderem, 1992; Corradin et al., 1999a). Interestingly, Corradin et al. (1999a) showed that L. major-infected macrophages were showing a significant MRP depletion (Corradin et al., 1999a), which latter can be inhibited in presence of GP63 inhibitors, or when the GP63 potential cleavage site in MRP is mutated, therefore confirming that GP63 is responsible for the hydrolysis of MRP, a major PKC substrate in macrophages (Corradin et al., 1999b). This finding is quite interesting as PKC—a critical serine/threonine kinase involved in signal transduction associated with cell proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis—is known to be greatly affected in Leishmania-infected macrophages and to be responsible for the inhibition of antimicrobial agents such as radical oxygens (Olivier et al., 1992a,b) also known to be caused by abnormal calcium-dependent signaling occurring upon Leishmania infection (Eilam et al., 1985; Olivier et al., 1992a). However, several studies highlighted a reduced PKC activity in macrophages infected with L. donovani promastigotes (McNeely and Turco, 1987; Descoteaux et al., 1992; Olivier et al., 1992b) and to be correlated with LPG inhibitory capacity (Descoteaux et al., 1992). Interestingly, amastigotes—which naturally lack LPG—were still able to inhibit PKC activity when used to infect human monocytes (Olivier et al., 1992b), indicating the possibility that amastigote GP63-dependent alternative mechanisms could be involved, but this still needs to be further investigated, as well as the impact of amastigote cysteine proteases of various Leishmania sps.

GP63-mediated PTP activation and impact on JAK/STAT signaling pathway

Of utmost interest, it is the discovery that the JAK1/2/STAT1α pathway—a major player in IFN-γ signaling pathway—responsible for the production of several toxic antimicrobial agents such as nitric oxide, was greatly altered in Leishmania-infected cells. And the fact that in the last decades or so, Leishmania-induced activation of the protein tyrosine phosphatase (PTP) SHP-1 was found critical in that negative regulation. Several groups reported that SHP-1 is involved in the inhibition of JAK/STAT pathways IFN-γ stimulation (Nandan and Reiner, 1995; Blanchette et al., 1999; Forget et al., 2006). In-depth in vivo studies using SHP-1-deficient mice (viable motheaten still have some SHP-1 activity) confirmed that SHP-1 is important for L. major survival and progression within footpad of its mammalian host by dampening NO dependent and independent microbicidal mechanisms (Forget et al., 2001, 2005b). However, others (Spath et al., 2008) claim that SHP-1 was not involved, having solely observed an initial significant reduction of lesion on the rump followed by a normal progression of the lesion development few weeks later. This discrepancy could be accounted to several factors such as site of infection, mice microbiota (that could have influence SHP-1 expression), germ-free animal facility, as well as, and importantly, age at which mice where used. Nevertheless, since then other PTPs have been found to be induced upon Leishmania infections, and to be involved in the progression of leishmaniasis.

In regards to the role of GP63 in the activation of this negative regulation of host signaling, it is only recently that Gomez et al. (2009) highlighted that the parasite metalloprotease was a critical player in PTP activation. Using L. major wild-type, GP63−/− and GP63 rescued strains, it has been demonstrated that GP63 is responsible for the activation upon cleavage at the C′ terminal portion of the PTPs- of SHP-1, PTP1B and TCPTP. It was showed that GP63 directly interacts with those cytoplasmic PTPs upon its entrance via lipid raft microdomains (Gomez et al., 2009). Whereas the used of TCPTP−/− mice is not possible—as they are viable only for short time after birth—for infectious challenge, PTP1B−/− mice infected with L. major showed a delay in the onset and progression of footpad inflammation and reduced parasite burden in the early stages of the disease compared to wild-type mice. This latter observation being another demonstration that PTPs have to some extend a role to play in the strategy used by Leishmania parasite to subvert host innate immune response favoring its survival and progression. What this study also revealed is that several PTPs being modulated by Leishmania could be necessary to have a full infectious impact on the host. In fact, it will be interesting in a near future to test whether a triple knock-out of those main PTPs identified to be modulated by Leishmania infection, could confer a robust protection for the host. This is quite realistic, as those three PTPs (e.g., SHP-1, PTP1B, SHP-1) have been demonstrated to be critical in the control of JAK/STAT pathways in regards to IFN-γ signaling (Simoncic et al., 2002; ten Hoeve et al., 2002).

As another consequence of the GP63-mediated activation of PTPs, it has been demonstrated that Leishmania-infected cells where refractory to LPS stimulation due to the inactivation of toll like receptor (TLR) signaling. More precisely, Abu-Dayyeh et al. (2008) found that upon Leishmania infection, SHP-1 rapidly binds to one of the central kinases of TLR pathway, the IRAK-1, completely inactivating its kinase activity and any further LPS-mediated activation, as well as macrophage functions. Explaining in part, the negative regulatory mechanisms that concur to tame-down several LPS-induced macrophage functions (TNF-α, NO, IL-12) upon Leishmania infection reported by several groups (review in Abu-Dayyeh et al., 2008).

PTPs and MAP kinase (MAPK) family

The three major MAPK (Mitogen Activated Protein Kinases) studied are ERK1/2, p38 and SAPK/JNK (Stress Activated Protein Kinase/C-Jun Kinase). Their activation requires dual phosphorylation of serine/threonine and tyrosine residues, and therefore their deactivation occurs through the action of PTPs, serine/threonine phosphatases (STPs), or dual specificity phosphatases (DSPs). Inhibition of MAPK following Leishmania infection and involving PTPs has been reported by different groups using L. amazonensis or L. donovani (Martiny et al., 1999; Nandan et al., 1999; Forget et al., 2006). In all studies, it was suggested that PTPs are responsible for ERK1/2 dephosphorylation. Later on, SHP-1 has been shown to be involved in ERK1/2 and the SAPK/JNK dephosphorylation (Forget et al., 2006; Blanchette et al., 2009). Whereas GP63 has not been proved to impact directly on MAPK inactivation, GP63-mediated SHP-1 activation is more than likely to be involved. However, we have indication that JNK kinase is cleaved by GP63 (Contreras and Olivier, unpublished data) and it could, therefore, have an impact on that branch of MAPK signaling. In fact as we recently revealed (see below in details), the downstream signaling target of JNK, namely c-Jun, is also degraded by GP63 (Contreras et al., 2010).

Concerning the implications of the other phosphatases (STPs and DSPs) mentioned earlier, they have been found to negatively regulate MAPK signaling during Leishmania infection (Al-Mutairi et al., 2010; Kar et al., 2010; Srivastava et al., 2011). For instance STP PP2 and DSP MKP1 were found to regulate p38 activity, whereas MKP3 preferentially controls ERK1/2 (Kar et al., 2010). However, a role of GP63 in their activation process has not been studied.

GP63 and mTOR-dependent signaling

In regards to signaling molecules targeted by Leishmania GP63, a recent study by Jaramillo et al. (2011) revealed that L. major can also promote its survival by down regulating host macrophage protein synthesis under CAP-dependent translational events. This down regulation was found to be cause by the GP63-mediated alteration of mTORC1-dependent signaling which is pivotal for the regulation of this translational system. Importantly, GP63 deficient L. major promastigotes were not perturbing mTOR integrity and therefore not affecting translation initiation. This recent study highlighted a brand new subversion mechanism of Leishmania toward host macrophage functions, as to show how this parasite can also modify cytokine profiles favoring or at least taming down the development of an efficient anti-Leishmania adaptive immune response (Jaramillo et al., 2011).

Influence of GP63 on macrophage transcription factors

There is several transcription factors involved in the regulation of macrophage-specific gene expression such as NF-κB, STAT1, and AP-1. Whereas NF-κB family intervenes in gene expression involved in a wide range of macrophage functions, the STAT family members are known for their central role in cytokine-mediated signaling, such as in IFN-γ-induced iNOS expression. Of interest, several studies showed that Leishmania infection alters STAT1α signaling (Ray et al., 2000; Rosas et al., 2003; Forget et al., 2005a). However, this alteration does not solely result from the PTP-mediated inhibition of JAK2 and MAPK kinases up-stream of the biochemical cascade, but also involved the rapid degradation of STAT1α by nuclear proteasome machinery under PKC-α regulation (Forget et al., 2005a). Unpublished observations from our laboratory suggest that GP63 could be involved, however at that time we were not suspecting that Leishmania GP63 was capable to reach macrophage nuclear compartment.

In regard to the more pleiotropic transcription factor NF-κB, Gregory et al. (2008) reported that various Leishmania sps. infecting macrophage were effective to induce the specific cleavage of the NF-κB p65RelA subunit in the cytoplasm, releasing a p35RelA that migrates to the nucleus where it binds DNA as a heterodimer with NF-κB p50. This cleavage was shown to be GP63-dependent (Gregory et al., 2008) and to be critical for the induction of selected chemokines by Leishmania-infected macrophages. Importantly, modulation of other NF-κB family members upon infection of human phagocytes by Leishmania have been reported and also found to influence host cell cytokine production (Guizani-Tabbane et al., 2004). In addition to GP63, the cysteine peptidases of L. mexicana amastigotes were found to act more drastically on NF-κB by almost completely degrading this latter and therefore concurring to strongly shutdown LPS-induced IL-12 production by macrophages (Cameron et al., 2004).

In addition to the transcription factors NF-κB and STAT1α, it has been reported by several laboratories that AP-1, also critical in IFN-γ-induced NO production, was strongly affected by Leishmania infection (review in Olivier et al., 2005). Per se, AP-1 is formed by homodimers of Jun family members (c-Jun, JunB, and Jun D), or heterodimers of Jun and Fos family members (c-Fos, Fos B, Fra 1, and Fra 2) (Karin et al., 1997). As mentioned above, previous studies have reported that Leishmania infection concurs to inactivate the AP-1 transcription factor. For instance, it has been proposed that ceramide augmentation—measured in cells infected with L. donovani promastigotes—is responsible for macrophage PKC and ERK1/2 signaling alteration leading to AP-1 inactivation (Ghosh et al., 2001, 2002). In the same vein, other studies have also shown that Leishmania alters signal transduction upstream of c-Fos and c-Jun by inhibiting ERK, JNK, and p38 MAP Kinases, resulting in a reduction of AP-1 nuclear translocation (Nandan et al., 1999; Prive and Descoteaux, 2000). However, by looking more closely at AP-1 nuclear integrity during Leishmania infection, we have investigated how GP63 contributes to AP-1 inactivation and the degradation of its various subunits forming this transcription factors. Of utmost interest, we found that GP63 after rapidly reaching macrophage cytoplasm via lipid raft microdomains—as during the process leading to PTP activation earlier—and independently of parasite internalization, it is able to reach the nuclear compartment where it degrades and cleaves c-Jun and other AP-1 subunits and therefore drastically affect the integrity of the transcription factor AP-1 during the early moment of Leishmania infection (Contreras et al., 2010). As AP-1 is a critical transcription factor involved in the regulation of innate inflammatory response, we sincerely believe that its rapid inactivation, concurrently with the modification of NF-κB behavior, must favor the parasite to survive by sufficiently taming down the initial macrophage inflammatory and anti-microbial responses—and potentially of other phagocytic cells—that are not fully inhibited, as some chemokines are known to be secreted during the early moments of infection leading to the recruitment of phagocytic cells to the site of infection. Thus at the view of these evidences, it is clear that the Leishmania metalloprotease GP63 is strongly influencing the transcription factors of the host cells as another way whereby it can influence the macrophage functions to survive and progress.

Influence of Leishmania GP63 on other immune cells

Although macrophages are the primary host cells harboring amastigotes following initial infection, other cells of the innate immune system are known to be involved in the establishment of the infection by the parasite Leishmania, and their functions could be also influenced by GP63. For instance, Lieke et al. (2008) showed that proliferation, receptor expression and IFN-γ released by natural killer (NK) cells are affected by L. major GP63, which could have an important impact by inhibiting the Th1 immune response, crucial to control the parasite infection (Lieke et al., 2008). Importantly, NK cells have been shown to be affected by secreted GP63, as this cell type is not phagocytic and never been reported to be infected per se. On the other hand, certain cell types known to be non-phagocytic can become infected by Leishmania. Accordingly, fibroblasts, which are abundant in the immediate environment where promastigotes are usually inoculated—as well as part of cells forming lymph nodes—have been reported in mouse infection to internalize parasites (Bogdan et al., 2000). Their limited capacity to eliminate parasites due to a low NO production imply that these cells could act as a reservoir for long term infection. In support of this, we found that Leishmania-infected fibroblasts are greatly affected at the signaling level (Halle et al., 2009). In fact we showed that in those cells, L. major parasite, via its GP63, modifies several host signaling proteins involved in rearrangement of the actin cytoskeleton and in MAPK-signaling pathway, such as the phosphorylated adaptor protein p130Cas, the PTP-PEST, cortactin, the T Cell-protein tyrosine phosphatase TC-PTP, caspase-3, and p38 via the p38 regulator TAB1. These results confirm the key role of GP63 in a number of host cell molecular events, other than in macrophage, which could contribute to Leishmania survival and progression within its mammalian host.

Finally, there has been growing evidence for the potential role of neutrophils during the early stages of Leishmania infection. This cell type is known to be rapidly recruited to infection sites—as well as monocytes and macrophages—and to favor the presentation of internalized parasites to macrophages that are the final cellular host of Leishmania. Interestingly, it has been shown in a previous study, that neutrophils incubation with L. major GP63 inhibits both their chemotaxis and oxidative burst in a dose–dependent manner; which inhibitory effect was completely abolished by heat inactivation (Sorensen et al., 1994). In addition, it is well known that phagocytosis is one of the best characterized killing mechanisms in neutrophils. Importantly, it has been reported in the last 10 years that neutrophils are very effective to kill microbes using NETs, which is composed of released chromatin and specific granule proteins in response to various stimuli, and found to kill various microorganisms (Brinkmann et al., 2004). Recently, Gabriel et al. (2010) demonstrated that L. donovani promastigotes induce the rapid release of NETs from human neutrophils concurring to the capture of Leishmania by these structures. Interestingly, this was not causing the death of the parasite that could escape thereafter. Using Leishmania deficient for GP63, they found that the parasite metalloprotease, was not involved neither in the induction of NETs by Leishmania, nor in the parasite resistance to their microbicidal activity (Gabriel et al., 2010). This finding is refreshing as it reveals that GP63 does not only have a systemic impact on cellular and functional target of the host cell, but that can be selective in its action.

Concluding remark

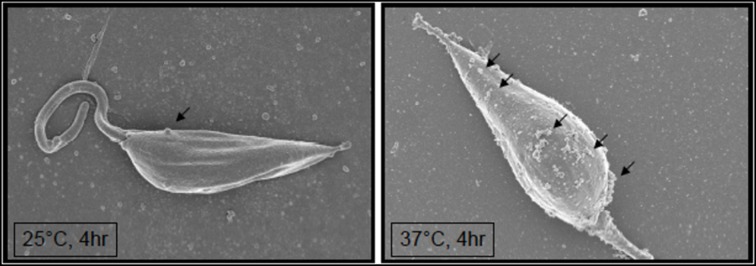

At the view of the findings reported above, it is quite clear that Leishmania GP63 is a very powerful protease that can rapidly act on a wide range of host cell substrates involved in cell signaling pathways and their regulation. Impact of GP63 on antimicrobial and inflammatory functions of macrophage has been extensively documented, further reinforcing its pivotal role as an important virulence factors contributing to its survival during the initial stage of the infection. The full profile of host proteins affected by GP63 is still unraveled and it will be important in a near future to identify them as to potentially develop new therapies to control Leishmania infection. Another important avenue to follow is to better understand the mechanisms whereby Leishmania GP63 enters the cytoplasmic and the nuclear compartment of infected cells. One of the mechanisms that have been proposed comes from our demonstration (Gomez et al., 2009; Gomez and Olivier, 2010) that GP63 was found to co-localize with macrophage lipid rafts during Leishmania infection, and that this GP63 entrance and co-localization was abrogated by the depletion of lipid raft cholesterol using β-cyclodextrin. This blockage of GP63 entrance was also reflected by absence of cleavage and of PTPs activation (SHP-1 and PTP1B). Interestingly, that perturbation of lipid raft integrity did not impair TCPTP cleavage, thus indicating an alternative mechanism of GP63 internalization (Gomez et al., 2009). In this regard, we suspect that GPI-anchored GP63 is favored to enter via lipid raft microdomains, whereas GP63 that is not GPI-anchored (as three different forms of GP63 can be found in the parasite) enter through a yet unidentified mechanism to reach nuclear compartment to cleave and activate TCPTP. Recently, Silverman et al. (2010) proposed that excreted vesicules from L. donovani, the exosomes, could fuse with macrophage once in the phagolysosomal compartment to release its content into the cytoplasm of the infected cells (Silverman et al., 2010). In support of this, Hassani et al. (2011) showed that L. mexicana exoproteomes—also containing exosome having budded from the parasite surface upon temperature shift (see Figure 2)—contain GPI-anchored GP63 (Hassani et al., 2011). Therefore, the rapid movement of GP63 within macrophage cytoplasm could come from exosome fusion with the macrophage plasma membrane and represent another route for GP63 entry within the host macrophage environment.

Figure 2.

Temperature shift (25–37°C) induces formation of exosomes at the surface of Leishmania mexicana promastigotes. (Arrows point at emerging exosomes). Hassani and Olivier (unpublished).

Collectively, the Leishmania metalloprotease GP63 is still just revealing its importance as a critical virulence factor, and future research will be warranted to be pursued in order to fully appreciate its impact on host cell functions, as a better knowledge of its mode of action could lead to the development of new therapeutic and even new prophylactic (Olivier and Hassani, 2010) to reduce its infectivity and capacity to invade mammalian macrophages.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Research performed in Dr. Martin Olivier is supported by grants from the Canadian Institute for Health Research (CIHR) and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC). Martin Olivier is member of the FQRNT Centre for Host-Parasite Interaction (CHPI).

References

- Abu-Dayyeh I., Shio M. T., Sato S., Akira S., Cousineau B., Olivier M. (2008). Leishmania-induced IRAK-1 inactivation is mediated by SHP-1 interacting with an evolutionarily conserved KTIM motif. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2:e305 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aderem A. (1992). The MARCKS brothers: a family of protein kinase C substrates. Cell 71, 713–716 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90546-O [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Mutairi M. S., Cadalbert L. C., McGachy H. A., Shweash M., Schroeder J., Kurnik M., Sloss C. M., Bryant C. E., Alexander J., Plevin R. (2010). MAP kinase phosphatase-2 plays a critical role in response to infection by Leishmania mexicana. PLoS Pathog. 6:e1001192 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackshear P. J. (1993). The MARCKS family of cellular protein kinase C substrates. J. Biol. Chem. 268, 1501–1504 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchette J., Abu-Dayyeh I., Hassani K., Whitcombe L., Olivier M. (2009). Regulation of macrophage nitric oxide production by the protein tyrosine phosphatase Src homology 2 domain phosphotyrosine phosphatase 1 (SHP-1). Immunology 127, 123–133 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2008.02929.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchette J., Racette N., Faure R., Siminovitch K. A., Olivier M. (1999). Leishmania-induced increases in activation of macrophage SHP-1 tyrosine phosphatase are associated with impaired IFN-gamma-triggered JAK2 activation. Eur. J. Immunol. 29, 3737–3744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogdan C., Donhauser N., Doring R., Rollinghoff M., Diefenbach A., Rittig M. G. (2000). Fibroblasts as host cells in latent leishmaniosis. J. Exp. Med. 191, 2121–2130 10.1084/jem.191.12.2121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bordier C., Etges R. J., Ward J., Turner M. J., Cardoso de Almeida M. L. (1986). Leishmania and Trypanosoma surface glycoproteins have a common glycophospholipid membrane anchor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 83, 5988–5991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouvier J., Bordier C., Vogel H., Reichelt R., Etges R. (1989). Characterization of the promastigote surface protease of Leishmania as a membrane-bound zinc endopeptidase. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 37, 235–245 10.1016/0166-6851(89)90155-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouvier J., Etges R. J., Bordier C. (1985). Identification and purification of membrane and soluble forms of the major surface protein of Leishmania promastigotes. J. Biol. Chem. 260, 15504–15509 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinkmann V., Reichard U., Goosmann C., Fauler B., Uhlemann Y., Weiss D. S., Weinrauch Y., Zychlinsky A. (2004). Neutrophil extracellular traps kill bacteria. Science 303, 1532–1535 10.1007/978-1-61779-527-5_7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brittingham A., Morrison C. J., McMaster W. R., McGwire B. S., Chang K. P., Mosser D. M. (1995). Role of the Leishmania surface protease GP63 in complement fixation, cell adhesion, and resistance to complement-mediated lysis. J. Immunol. 155, 3102–3111 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron P., McGachy A., Anderson M., Paul A., Coombs G. H., Mottram J. C., Alexander J., Plevin R. (2004). Inhibition of lipopolysaccharide-induced macrophage IL-12 production by Leishmania mexicana amastigotes: the role of cysteine peptidases and the NF-kappaB signaling pathway. J. Immunol. 173, 3297–3304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang C. S., Inserra T. J., Kink J. A., Fong D., Chang K. P. (1986). Expression and size heterogeneity of a 63 kilodalton membrane glycoprotein during growth and transformation of Leishmania mexicana amazonensis. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 18, 197–210 10.1016/0166-6851(86)90038-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang K. P., McGwire B. S. (2002). Molecular determinants and regulation of Leishmania virulence. Kinetoplastid Biol. Dis. 1, 1 10.1186/1475-9292-1-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhuri G., Chang K. P. (1988). Acid protease activity of a major surface membrane glycoprotein (GP63) from Leishmania mexicana promastigotes. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 27, 43–52 10.1016/0166-6851(88)90023-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhuri G., Chaudhuri M., Pan A., Chang K. P. (1989). Surface acid proteinase (GP63) of Leishmania mexicana. A metalloenzyme capable of protecting liposome-encapsulated proteins from phagolysosomal degradation by macrophages. J. Biol. Chem. 264, 7483–7489 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen D. Q., Kolli B. K., Yadava N., Lu H. G., Gilman-Sachs A., Peterson D. A., Chang K. P. (2000). Episomal expression of specific sense and antisense mRNAs in Leishmania amazonensis: modulation of GP63 level in promastigotes and their infection of macrophages in vitro. Infect. Immun. 68, 80–86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contreras I., Gómez M. A., Nguyen O., Shio M. T., McMaster R. W., Olivier M. (2010). Leishmania-induced inactivation of the macrophage transcription factor AP-1 is mediated by the parasite metalloprotease GP63. PLoS Pathog. 6:e1001148 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corradin S., Mauel J., Ransijn A., Sturzinger C., Vergeres G. (1999a). Down-regulation of MARCKS-related protein (MRP) in macrophages infected with Leishmania. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 16782–16787 10.1074/jbc.274.24.16782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corradin S., Ransijn A., Corradin G., Roggero M. A., Schmitz A. A., Schneider P., Mauel J., Vergeres G. (1999b). MARCKS-related protein (MRP) is a substrate for the Leishmania major surface protease leishmanolysin (GP63). J. Biol. Chem. 274, 25411–25418 10.1074/jbc.274.36.25411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Descoteaux A., Matlashewski G., Turco S. J. (1992). Inhibition of macrophage protein kinase C-mediated protein phosphorylation by Leishmania donovani lipophosphoglycan. J. Immunol. 149, 3008–3015 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eilam Y., El-on J., Spira D. T. (1985). Leishmania major: excreted factor, calcium ions, and the survival of amastigotes. Exp. Parasitol. 59, 161–168 10.1016/0014-4894(85)90068-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis M., Sharma D. K., Hilley J. D., Coombs G. H., Mottram J. C. (2002). Processing and trafficking of Leishmania mexicana GP63. Analysis using GP18 mutants deficient in glycosylphosphatidylinositol protein anchoring. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 27968–27974 10.1074/jbc.M202047200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etges R., Bouvier J., Bordier C. (1986). The major surface protein of Leishmania promastigotes is a protease. J. Biol. Chem. 261, 9098–9101 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etges R. J., Bouvier J., Hoffman R., Bordier C. (1985). Evidence that the major surface proteins of three Leishmania species are structurally related. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 14, 141–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fong D., Chang K. P. (1982). Surface antigenic change during differentiation of a parasitic protozoan, Leishmania mexicana: identification by monoclonal antibodies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 79, 7366–7370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forget G., Gregory D. J., Olivier M. (2005a). Proteasome-mediated degradation of STAT1alpha following infection of macrophages with Leishmania donovani. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 30542–30549 10.1074/jbc.M414126200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forget G., Gregory D. J., Whitcombe L. A., Olivier M. (2006). Role of host protein tyrosine phosphatase SHP-1 in Leishmania donovani-induced inhibition of nitric oxide production. Infect. Immun. 74, 6272–6279 10.1128/IAI.00853-05 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forget G., Matte C., Siminovitch K. A., Rivest S., Pouliot P., Olivier M. (2005b). Regulation of the Leishmania-induced innate inflammatory response by the protein tyrosine phosphatase SHP-1. Eur. J. Immunol. 35, 1906–1917 10.1002/eji.200526037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forget G., Siminovitch K. A., Brochu S., Rivest S., Radzioch D., Olivier M. (2001). Role of host phosphotyrosine phosphatase SHP-1 in the development of murine leishmaniasis. Eur. J. Immunol. 31, 3185–3196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frommel T. O., Button L. L., Fujikura Y., McMaster W. R. (1990). The major surface glycoprotein (GP63) is present in both life stages of Leishmania. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 38, 25–32 10.1016/0166-6851(90)90201-V [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabriel C., McMaster W. R., Girard D., Descoteaux A. (2010). Leishmania donovani promastigotes evade the antimicrobial activity of neutrophil extracellular traps. J. Immunol. 185, 4319–4327 10.4049/jimmunol.1000893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh S., Bhattacharyya S., Das S., Raha S., Maulik N., Das D. K., Roy S., Majumdar S. (2001). Generation of ceramide in murine macrophages infected with Leishmania donovani alters macrophage signaling events and aids intracellular parasitic survival. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 223, 47–60 10.1023/A:1017996609928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh S., Bhattacharyya S., Sirkar M., Sa G. S., Das T., Majumdar D., Roy S., Majumdar S. (2002). Leishmania donovani suppresses activated protein 1 and NF-kappaB activation in host macrophages via ceramide generation: involvement of extracellular signal-regulated kinase. Infect. Immun. 70, 6828–6838 10.1128/IAI.70.12.6828-6838.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez M. A., Contreras I., Halle M., Tremblay M. L., McMaster R. W., Olivier M. (2009). Leishmania GP63 alters host signaling through cleavage-activated protein tyrosine phosphatases. Sci. Signal. 2, ra58 10.1126/scisignal.2000213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez M. A., Olivier M. (2010). Proteases and phosphatases during Leishmania-macrophage interaction: paving the road for pathogenesis. Virulence 1, 314–318 10.4161/viru.1.4.12194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory D. J., Godbout M., Contreras I., Forget G., Olivier M. (2008). A novel form of NF-kappaB is induced by Leishmania infection: involvement in macrophage gene expression. Eur. J. Immunol. 38, 1071–1081 10.1002/eji.200737586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guimaraes-Costa A. B., Nascimento M. T., Froment G. S., Soares R. P., Morgado F. N., Conceicao-Silva F., Saraiva E. M. (2009). Leishmania amazonensis promastigotes induce and are killed by neutrophil extracellular traps. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 6748–6753 10.1073/pnas.0900226106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guizani-Tabbane L., Ben-Aissa K., Belghith M., Sassi A., Dellagi K. (2004). Leishmania major amastigotes induce p50/c-Rel NF-kappa B transcription factor in human macrophages: involvement in cytokine synthesis. Infect. Immun. 72, 2582–2589 10.1128/IAI.72.5.2582-2589.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halle M., Gomez M. A., Stuible M., Shimizu H., McMaster W. R., Olivier M., Tremblay M. L. (2009). The Leishmania surface protease GP63 cleaves multiple intracellular proteins and actively participates in p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase inactivation. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 6893–6908 10.1074/jbc.M805861200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassani K., Antoniak E., Jardim A., Olivier M. (2011). Temperature-induced protein secretion by Leishmania mexicana modulates macrophage signalling and function. PLoS ONE 6:e18724 10.1371/journal.pone.0018724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao C. H., Yao C., Storlie P., Donelson J. E., Wilson M. E. (2008). The major surface protease (MSP or GP63) in the intracellular amastigote stage of Leishmania chagasi. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 157, 148–159 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2007.10.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilg T., Harbecke D., Overath P. (1993). The lysosomal GP63-related protein in Leishmania mexicana amastigotes is a soluble metalloproteinase with an acidic pH optimum. FEBS Lett. 327, 103–107 10.1016/0014-5793(93)81049-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivens A. C., Peacock C. S., Worthey E. A., Murphy L., Aggarwal G., Berriman M., Sisk E., Rajandream M. A., Adlem E., Aert R., Anupama A., Apostolou Z., Attipoe P., Bason N., Bauser C., Beck A., Beverley S. M., Bianchettin G., Borzym K., Bothe G., Bruschi C. V., Collins M., Cadag E., Ciarloni L., Clayton C., Coulson R. M., Cronin A., Cruz A. K., Davies R. M., De Gaudenzi J., Dobson D. E., Duesterhoeft A., Fazelina G., Fosker N., Frasch A. C., Fraser A., Fuchs M., Gabel C., Goble A., Goffeau A., Harris D., Hertz-Fowler C., Hilbert H., Horn D., Huang Y., Klages S., Knights A., Kube M., Larke N., Litvin L., Lord A., Louie T., Marra M., Masuy D., Matthews K., Michaeli S., Mottram J. C., Muller-Auer S., Munden H., Nelson S., Norbertczak H., Oliver K., O'Neil S., Pentony M., Pohl T. M., Price C., Purnelle B., Quail M. A., Rabbinowitsch E., Reinhardt R., Rieger M., Rinta J., Robben J., Robertson L., Ruiz J. C., Rutter S., Saunders D., Schafer M., Schein J., Schwartz D. C., Seeger K., Seyler A., Sharp S., Shin H., Sivam D., Squares R., Squares S., Tosato V., Vogt C., Volckaert G., Wambutt R., Warren T., Wedler H., Woodward J., Zhou S., Zimmermann W., Smith D. F., Blackwell J. M., Stuart K. D., Barrell B., Myler P. J. (2005). The genome of the kinetoplastid parasite, Leishmania major. Science 309, 436–442 10.1126/science.1112680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaramillo M., Gomez M. A., Larsson O., Shio M. T., Topisirovic I., Contreras I., Luxenburg R., Rosenfeld A., Colina R., McMaster R. W., Olivier M., Costa-Mattioli M., Sonenberg N. (2011). Leishmania repression of host translation through mTOR cleavage is required for parasite survival and infection. Cell Host Microbe 9, 331–341 10.1016/j.chom.2011.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi P. B., Kelly B. L., Kamhawi S., Sacks D. L., McMaster W. R. (2002). Targeted gene deletion in Leishmania major identifies leishmanolysin (GP63) as a virulence factor. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 120, 33–40 10.1016/S0166-6851(01)00432-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi P. B., Sacks D. L., Modi G., McMaster W. R. (1998). Targeted gene deletion of Leishmania major genes encoding developmental stage-specific leishmanolysin (GP63). Mol. Microbiol. 27, 519–530 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00689.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kar S., Ukil A., Sharma G., Das P. K. (2010). MAPK-directed phosphatases preferentially regulate pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines in experimental visceral leishmaniasis: involvement of distinct protein kinase C isoforms. J. Leukoc. Biol. 88, 9–20 10.1189/jlb.0909644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karin M., Liu Z., Zandi E. (1997). AP-1 function and regulation. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 9, 240–246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly B. L., Nelson T. N., McMaster W. R. (2001). Stage-specific expression in Leishmania conferred by 3' untranslated regions of L. major leishmanolysin genes (GP63). Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 116, 101–104 10.1016/S0166-6851(01)00307-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni M. M., McMaster W. R., Kamysz E., Kamysz W., Engman D. M., McGwire B. S. (2006). The major surface-metalloprotease of the parasitic protozoan, Leishmania, protects against antimicrobial peptide-induced apoptotic killing. Mol. Microbiol. 62, 1484–1497 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05459.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Aderem A. (1992). MacMARCKS, a novel member of the MARCKS family of protein kinase C substrates. Cell 70, 791–801 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90312-Z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieke T., Nylen S., Eidsmo L., McMaster W. R., Mohammadi A. M., Khamesipour A., Berg L., Akuffo H. (2008). Leishmania surface protein GP63 binds directly to human natural killer cells and inhibits proliferation. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 153, 221–230 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2008.03687.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma L., Chen K., Meng Q., Liu Q., Tang P., Hu S., Yu J. (2011a). An evolutionary analysis of trypanosomatid GP63 proteases. Parasitol. Res. 109, 1075–1078 10.1007/s00436-011-2348-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma L., Meng Q., Cheng W., Sung Y., Tang P., Hu S., Yu J. (2011b). Involvement of the GP63 protease in infection of Trichomonas vaginalis. Parasitol. Res. 109, 71–79 10.1007/s00436-010-2222-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangoni M. L., Saugar J. M., Dellisanti M., Barra D., Simmaco M., Rivas L. (2005). Temporins, small antimicrobial peptides with leishmanicidal activity. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 984–990 10.1074/jbc.M410795200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martiny A., Meyer-Fernandes J. R., De Souza W., Vannier-Santos M. A. (1999). Altered tyrosine phosphorylation of ERK1 MAP kinase and other macrophage molecules caused by Leishmania amastigotes. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 102, 1–12 10.1016/S0166-6851(99)00067-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGwire B. S., Chang K. P. (1996). Posttranslational regulation of a Leishmania HEXXH metalloprotease (GP63). The effects of site-specific mutagenesis of catalytic, zinc binding, N-glycosylation, and glycosyl phosphatidylinositol addition sites on N-terminal end cleavage, intracellular stability, and extracellular exit. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 7903–7909 10.1074/jbc.271.14.7903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGwire B. S., Chang K. P., Engman D. M. (2003). Migration through the extracellular matrix by the parasitic protozoan Leishmania is enhanced by surface metalloprotease GP63. Infect. Immun. 71, 1008–1010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGwire B. S., O'Connell W. A., Chang K. P., Engman D. M. (2002). Extracellular release of the glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-linked Leishmania surface metalloprotease, GP63, is independent of GPI phospholipolysis: implications for parasite virulence. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 8802–8809 10.1074/jbc.M109072200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeely T. B., Turco S. J. (1987). Inhibition of protein kinase C activity by the Leishmania donovani lipophosphoglycan. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 148, 653–657 10.1016/0006-291X(87)90926-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medina-Acosta E., Karess R. E., Schwartz H., Russell D. G. (1989). The promastigote surface protease (GP63) of Leishmania is expressed but differentially processed and localized in the amastigote stage. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 37, 263–273 10.1016/0166-6851(89)90158-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nandan D., Lo R., Reiner N. E. (1999). Activation of phosphotyrosine phosphatase activity attenuates mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling and inhibits c-FOS and nitric oxide synthase expression in macrophages infected with Leishmania donovani. Infect. Immun. 67, 4055–4063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nandan D., Reiner N. E. (1995). Attenuation of gamma interferon-induced tyrosine phosphorylation in mononuclear phagocytes infected with Leishmania donovani: selective inhibition of signaling through Janus kinases and Stat1. Infect. Immun. 63, 4495–4500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivier M., Baimbridge K. G., Reiner N. E. (1992a). Stimulus-response coupling in monocytes infected with Leishmania. Attenuation of calcium transients is related to defective agonist-induced accumulation of inositol phosphates. J. Immunol. 148, 1188–1196 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivier M., Brownsey R. W., Reiner N. E. (1992b). Defective stimulus-response coupling in human monocytes infected with Leishmania donovani is associated with altered activation and translocation of protein kinase C. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 89, 7481–7485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivier M., Gregory D. J., Forget G. (2005). Subversion mechanisms by which Leishmania parasites can escape the host immune response: a signaling point of view. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 18, 293–305 10.1128/CMR.18.2.293-305.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivier M., Hassani K. (2010). Protease inhibitors as prophylaxis against leishmaniasis: new hope from the major surface protease GP63. Future Med. Chem. 2, 539–542 10.4155/fmc.10.17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papayannopoulos V., Zychlinsky A. (2009). NETs: a new strategy for using old weapons. Trends Immunol. 30, 513–521 10.1016/j.it.2009.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peacock C. S., Seeger K., Harris D., Murphy L., Ruiz J. C., Quail M. A., Peters N., Adlem E., Tivey A., Aslett M., Kerhornou A., Ivens A., Fraser A., Rajandream M. A., Carver T., Norbertczak H., Chillingworth T., Hance Z., Jagels K., Moule S., Ormond D., Rutter S., Squares R., Whitehead S., Rabbinowitsch E., Arrowsmith C., White B., Thurston S., Bringaud F., Baldauf S. L., Faulconbridge A., Jeffares D., Depledge D. P., Oyola S. O., Hilley J. D., Brito L. O., Tosi L. R., Barrell B., Cruz A. K., Mottram J. C., Smith D. F., Berriman M. (2007). Comparative genomic analysis of three Leishmania species that cause diverse human disease. Nat. Genet. 39, 839–847 10.1038/ng2053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prive C., Descoteaux A. (2000). Leishmania donovani promastigotes evade the activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases p38, c-Jun N-terminal kinase, and extracellular signal-regulated kinase-1/2 during infection of naive macrophages. Eur. J. Immunol. 30, 2235–2244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray M., Gam A. A., Boykins R. A., Kenney R. T. (2000). Inhibition of interferon-gamma signaling by Leishmania donovani. J. Infect. Dis. 181, 1121–1128 10.1086/315330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts S. C., Swihart K. G., Agey M. W., Ramamoorthy R., Wilson M. E., Donelson J. E. (1993). Sequence diversity and organization of the msp gene family encoding GP63 of Leishmania chagasi. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 62, 157–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosas L. E., Keiser T., Pyles R., Durbin J., Satoskar A. R. (2003). Development of protective immunity against cutaneous leishmaniasis is dependent on STAT1-mediated IFN signaling pathway. Eur. J. Immunol. 33, 1799–1805 10.1002/eji.200323163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell D. G. (1987). The macrophage-attachment glycoprotein GP63 is the predominant C3-acceptor site on Leishmania mexicana promastigotes. Eur. J. Biochem. 164, 213–221 10.1016/0166-6851(89)90158-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell D. G., Wilhelm H. (1986). The involvement of the major surface glycoprotein (GP63) of Leishmania promastigotes in attachment to macrophages. J. Immunol. 136, 2613–2620 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider P., Rosat J. P., Bouvier J., Louis J., Bordier C. (1992). Leishmania major: differential regulation of the surface metalloprotease in amastigote and promastigote stages. Exp. Parasitol. 75, 196–206 10.1016/0014-4894(92)90179-E [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seay M. B., Heard P. L., Chaudhuri G. (1996). Surface Zn-proteinase as a molecule for defense of Leishmania mexicana amazonensis promastigotes against cytolysis inside macrophage phagolysosomes. Infect. Immun. 64, 5129–5137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman J. M., Clos J., De'Oliveira C. C., Shirvani O., Fang Y., Wang C., Foster L. J., Reiner N. E. (2010). An exosome-based secretion pathway is responsible for protein export from Leishmania and communication with macrophages. J. Cell Sci. 123, 842–852 10.1242/jcs.056465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simoncic P. D., Lee-Loy A., Barber D. L., Tremblay M. L., McGlade C. J. (2002). The T cell protein tyrosine phosphatase is a negative regulator of janus family kinases 1 and 3. Curr. Biol. 12, 446–453 10.1016/S0960-9822(02)00697-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen A. L., Hey A. S., Kharazmi A. (1994). Leishmania major surface protease Gp63 interferes with the function of human monocytes and neutrophils in vitro. APMIS 102, 265–271 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spath G. F., McDowell M. A., Beverley S. M. (2008). Leishmania major intracellular survival is not altered in SHP-1 deficient mev or CD45−/− mice. Exp. Parasitol. 120, 275–279 10.1016/j.exppara.2008.07.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava N., Sudan R., Saha B. (2011). CD40-modulated dual-specificity phosphatases MAPK phosphatase (MKP)-1 and MKP-3 reciprocally regulate Leishmania major infection. J. Immunol. 186, 5863–5872 10.4049/jimmunol.1003957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ten Hoeve J., de Jesus Ibarra-Sanchez M., Fu Y., Zhu W., Tremblay M., David M., Shuai K. (2002). Identification of a nuclear Stat1 protein tyrosine phosphatase. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22, 5662–5668 10.1128/MCB.22.16.5662-5668.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiakaki M., Kolli B., Chang K. P., Soteriadou K. (2006). Down-regulation of GP63 level in Leishmania amazonensis promastigotes reduces their infectivity in BALB/c mice. Microbes Infect. 8, 1455–1463 10.1016/j.micinf.2006.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tosi M. F. (2005). Innate immune responses to infection. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 116, 241–249 quiz 250. 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.05.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Chen Y., Xin L., Beverley S. M., Carlsen E. D., Popov V., Chang K. P., Wang M., Soong L. (2011). Differential microbicidal effects of human histone proteins H2A and H2B on Leishmania promastigotes and amastigotes. Infect. Immun. 79, 1124–1133 10.1128/IAI.00658-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weise F., Stierhof Y. D., Kuhn C., Wiese M., Overath P. (2000). Distribution of GPI-anchored proteins in the protozoan parasite Leishmania, based on an improved ultrastructural description using high-pressure frozen cells. J. Cell Sci. 113 (Pt 24), 4587–4603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao C., Donelson J. E., Wilson M. E. (2003). The major surface protease (MSP or GP63) of Leishmania sp. Biosynthesis, regulation of expression, and function. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 132, 1–16 10.1016/S0166-6851(03)00211-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao C., Leidal K. G., Brittingham A., Tarr D. E., Donelson J. E., Wilson M. E. (2002). Biosynthesis of the major surface protease GP63 of Leishmania chagasi. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 121, 119–128 10.1016/S0166-6851(02)00030-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]