Abstract

A large number of hypothetical genes potentially encoding small proteins of unknown function are annotated in the Brucella abortus genome. Individual deletion of 30 of these genes identified four mutants, in BAB1_0355, BAB2_0726, BAB2_0470, and BAB2_0450 that were highly attenuated for infection. BAB2_0726, an YbgT-family protein located at the 3′ end of the cydAB genes encoding cytochrome bd ubiquinal oxidase, was designated cydX. A B. abortus cydX mutant lacked cytochrome bd oxidase activity, as shown by increased sensitivity to H2O2, decreased acid tolerance and increased resistance to killing by respiratory inhibitors. The C terminus, but not the N terminus, of CydX was located in the periplasm, suggesting that CydX is an integral cytoplasmic membrane protein. Phenotypic analysis of the cydX mutant, therefore, suggested that CydX is required for full function of cytochrome bd oxidase, possibly via regulation of its assembly or activity.

Keywords: cytochrome oxidase, terminal electron acceptor, mutant screen, peptide

Introduction

Genes encoding small proteins are not well-characterized in the genomes of bacteria. An examination of the sequenced genomes shows that these small genes are not consistently annotated across related genomes, which raises the question of whether they encode functional genes. Further, the small size of the coding genes reduces the probability of identifying their functions in transposon mutagenesis screens. In bacteria, relatively few small proteins have been characterized. These include the toxin peptides of toxin/antitoxin systems, which insert into membranes and cause damage (Gerdes et al., 1986), and peptides that functions as “connectors” of two-component signal transduction systems (Eguchi et al., 2011). Recent studies in Escherichia coli and Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium have identified several small proteins whose expression had previously been overlooked in proteomic and genomic studies (Alix and Blanc-Potard, 2009; Hemm et al., 2010). One of these proteins, MgtR, modulates degradation of MgtC, a cytoplasmic protein involved in replication of S. typhimurium within host cells, by the FtsH protease, suggesting a role for MgtR in adaptation to the host environment (Alix and Blanc-Potard, 2008). A second peptide found to target the activity of FtsH protease, SpoVM, has been identified in Bacillus subtilis (Cutting et al., 1997). In Agrobacterium tumefaciens, a close phylogenetic relative of the Brucella species, a small protein VirE1 has been shown to serve as a secretion chaperone for the Type IV-exported single-strand binding protein VirE2 (Deng et al., 1999). Given their potential role in virulence-associated functions, we determined the role in intracellular survival of 30 genes with the potential to encode proteins of <15 kDa in the intracellular pathogen Brucella abortus. One of the proteins identified in this screen, BAB2_0726, was encoded in the 3′ region of cydAB, encoding cytochrome bd oxidase. This terminal oxidase of the respiratory chain is expressed by B. suis inside macrophages, the preferred intracellular niche in vivo (Loisel-Meyer et al., 2005), and contributes to intracellular replication of B. abortus, B. suis, and B. melitensis (Endley et al., 2001; Loisel-Meyer et al., 2005; Wu et al., 2006). We, therefore, focused our efforts on the contribution of BAB2_0726 to the function of cytochrome bd oxidase.

Materials and methods

Bacterial strains, media, and culture conditions

Escherichia coli TOP10 cells were used for all cloning steps and transformation of PCR products cloned into the pCR2.1 TOPO vector (Invitrogen). All E. coli strains were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth. Antibiotics carbenicillin (Carb) 100 μg/ml, kanamycin (Kan), 100 μg/ml or chloramphenicol (Cm), 30 μg/ml were used as appropriate. Brucella abortus biovar 1 strain 2308, a virulent strain originally isolated from cattle, was used for generation of mutants. Bacterial inocula used for infection of mice were cultured on tryptic soy agar (TSA) plus 5% defibrinated sheep blood. The antibiotics Carb 100 μg/ml, Kan, 50 μg/ml; Cm, 15 μg/ml were added as needed. All work with live B. abortus was performed at biosafety level 3. Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this work.

| Strain or plasmid | Description | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| PLASMIDS | ||

| pCR2.1 | PCR TOPO cloning vector | Invitrogen |

| pUC4Kixx | 1.3 Kb Kan cassette as SmaI fragment, AmpR, KanR | Pharmarcia |

| pBBR1MCS4 | Broad-host range vector confers AmpR | Kovach et al., 1995 |

| pFlagTEM1 | Cloning vector to express flagged TEM1 (FT) fusion under control of trc promoter, CmR | Raffatellu et al., 2005 |

| pCydX/FT | Expresses CydX::FT from trc promoter, CmR | This study |

| pFT/CydX | Expresses FT::CydX from trc promoter, CmR | This study |

| pGST/FT | Expresses GST::FT from trc promoter, CmR | Raffatellu et al., 2005 |

| pFT/GST | Expresses FT::GST fromtrc promoter, CmR | de Jong et al., 2008 |

| pGroEL/dsRed | Expresses DsRed from Brucella GroEL promoter, CmR | This study |

| pGroEL/CydX | Expresses CydX from Brucella GroEL promoter, CmR | This study |

| pGroEL/CydB | Expresses CydB from Brucella GroEL promoter, CmR | This study |

| pGroEL/CydBX | Expresses CydBX from Brucella GroEL promoter, CmR | This study |

| pBBR1Flag | Cloning vector to express flagged fusion under Brucella constitutive promoter, CmR | This study |

| pCydX/Flag | Expresses CydX::Flag from Brucella constitutive promoter, CmR | This study |

| BRUCELLA | ||

| B. abortus 2308 | Wild type | |

| ADH3 | ΔvirB2 (non polar) in B. abortus 2308 | den Hartigh et al., 2004 |

| BA41 | ΔvirB1::Tn5 in B. abortus 2308 | Hong et al., 2000 |

| BA582 | ΔcydB::Tn5 in B. abortus 2308 | Endley et al., 2001 |

| ΔBAB1_0061::Kan in B. abortus 2308 | This study | |

| ΔBAB1_0355::Kan in B. abortus 2308 | This study | |

| ΔBAB1_0513::Kan in B. abortus 2308 | This study | |

| ΔBAB1_0581::Kan in B. abortus 2308 | This study | |

| ΔBAB1_0626::Kan in B. abortus 2308 | This study | |

| ΔBAB1_0743::Kan in B. abortus 2308 | This study | |

| ΔBAB1_0992::Kan in B. abortus 2308 | This study | |

| ΔBAB1_1106::Kan in B. abortus 2308 | This study | |

| ΔBAB1_1194::Kan in B. abortus 2308 | This study | |

| ΔBAB1_1204::Kan in B. abortus 2308 | This study | |

| ΔBAB1_1262::Kan in B. abortus 2308 | This study | |

| ΔBAB1_1390::Kan in B. abortus 2308 | This study | |

| ΔBAB1_1392::Kan in B. abortus 2308 | This study | |

| ΔBAB1_1743::Kan in B. abortus 2308 | This study | |

| ΔBAB1_1748::Kan in B. abortus 2308 | This study | |

| ΔBAB1_1939::Kan in B. abortus 2308 | This study | |

| ΔBAB1_2041::Kan in B. abortus 2308 | This study | |

| ΔBAB2_0160::Kan in B. abortus 2308 | This study | |

| ΔBAB2_0170::Kan in B. abortus 2308 | This study | |

| ΔBAB2_0862::Kan in B. abortus 2308 | This study | |

| ΔBAB2_0761::Kan in B. abortus 2308 | This study | |

| ΔBAB2_0726::Kan in B. abortus 2308 (ΔcydX::Kan) | This study | |

| ΔBAB2_0470::Kan in B. abortus 2308 | This study | |

| ΔBAB2_0450::Kan in B. abortus 2308 | This study | |

| ΔBAB2_0415::Kan in B. abortus 2308 | This study | |

| ΔBAB2_0400::Kan in B. abortus 2308 | This study | |

| ΔBAB2_0232::Kan in B. abortus 2308 | This study | |

| ΔBAB2_1072::Kan in B. abortus 2308 | This study | |

| ΔBAB2_1087::Kan in B. abortus 2308 | This study | |

| ΔBAB2_1036::Kan in B. abortus 2308 | This study | |

| B. abortus 2308 with pCydX/Flag | This study | |

| B. abortus 2308 with pBBR1MCS4 | This study | |

| B. abortus 2308 with pFlagTEM1 | de Jong et al., 2008 | |

| B. abortus 2308 with pCydX/FT | This study | |

| B. abortus 2308 with pFT/CydX | This study | |

| B. abortus 2308 with pGST/FT | This study | |

| B. abortus 2308 with pFT/GST | de Jong et al., 2008 | |

| ΔcydX::Kan with pGroEL/dsRed | This study | |

| ΔcydX::Kan with pGroEL/CydX | This study | |

| ΔcydX::Kan with pCydX/Flag | This study | |

| BA582 with pGroEL/CydX | This study | |

| BA582 with pGroEL/CydB | This study | |

| BA582 with pGroEL/CydBX | This study | |

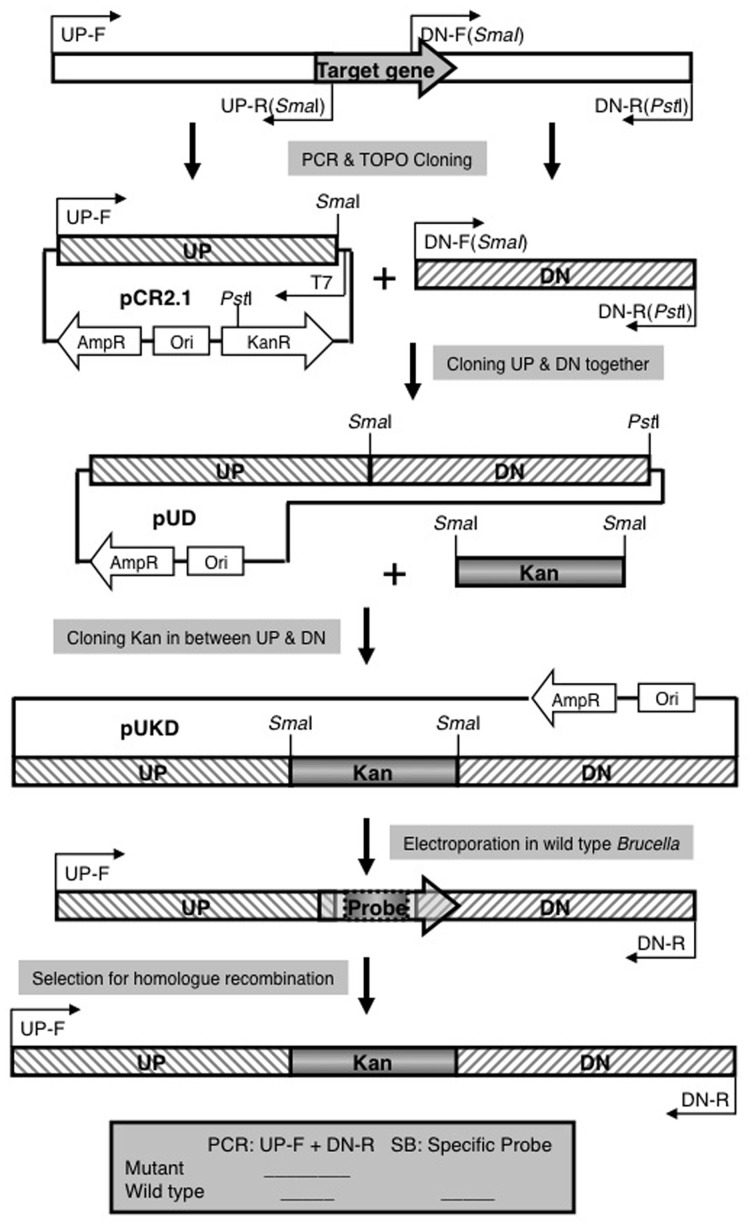

Allelic exchange mutagenesis

A previously reported three-step cloning strategy (Sun et al., 2005) was used to construct mutants for small open reading frames (Figure A1). Briefly, an upstream fragment (with a SmaI site in reverse primer) and a downstream fragment (with a SmaI site in forward primer and a PstI site in reverse primer), both measuring about 600–1200 bp, were amplified and cloned in pCR2.1. The orientation of the upstream fragment was determined by PCR using one primer specific for the insert and one primer specific for the vector (for example T7 promoter primer) to identify a clone with the SmaI site located at the f1 origin end of the multiple cloning site in TOPO cloning vector pCR2.1. The SmaI/PstI digested downstream fragment was then cloned next to the upstream fragment by using ampicillin for selection marker since the SmaI/PstI double digestion of vector cleaves a 1.2 Kb fragment from pCR2.1 backbone including part of kanamycin resistance gene. A 1.3 Kb SmaI fragment of pUC4KIXX (Pharmacia) containing the Tn5 kanamycin resistance gene was then cloned into the SmaI site to generate a construct for the allelic exchange of candidate gene with a deleted copy replaced by a kanamycin resistance gene. These plasmids were introduced into B. abortus 2308 by electroporation. Recombinants were screened for kanamycin resistance and carbenicillin sensitivity. Deletion of target genes was confirmed by PCR or/and southern blot.

RNA preparation and RT-PCR

B. abortus strains were grown for 48 h in tryptic soy broth (TSB) in parafilm-sealed tubes with minimal headspace to limit oxygen availability. The cells were harvested by centrifugation at 5000 × g. Total RNA was isolated using the Aurum Mini Kit (Bio-rad). RNA samples were digested with RNase-free DNase I (Invitrogen) and quantified using a NanoDrop spectrophometer (Thermo Scientific) at 260/280 nm. Reverse transcription was carried out using a standard protocol and MMLV Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen). Primer pairs used to amplify cydA (247 bp), cydB (243 bp), and cydX (204 bp) are listed in Table A1. PCR primers (2 μM) and cDNAs were added in PCR SuperMix (Invitrogen), and heated to 95°C for 5 min. Reactions omitting the reverse transcriptase served as negative controls. The PCR cycle consisted of 94°C for 10 s (denaturation), 52–55°C for 30 s (annealing), and 72°C for 10 s (extension), and this was repeated 30 times. PCR products were visualized after agarose gel (1.4%) electrophoresis and SYBR staining (Invitrogen).

Macrophage killing assay

The mouse macrophage-like cell line J774A.1, obtained from ATCC, was cultured in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium (DMEM; Gibco, Rockville, MD) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, 1% non-essential amino acids, and 1 mM Glutamine (DMEMsup). For macrophage killing assays, 24-well microtiter dishes were seeded with macrophages at a concentration of 1–2 × 105 cells/well in 0.5 ml of DMEMsup and incubated over night at 37°C in 5% CO2. Inocula were prepared by growth with shaking in TSB for 24 h, then subsequent dilution in DMEMsup to a concentration of 4 × 107 colony-forming units (CFU)/ml. Approximately 2 × 107 bacteria in 0.5 ml of DMEMsup, containing single or a 1:1 mixture of wild type and mutant, were added to each well of macrophages. Microtiter dishes were centrifuged at 250 × g for 5 min at room temperature in order to synchronize infection. Cells were incubated for 20 min at 37°C in 5% CO2, free bacteria were removed by three washes with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). DMEMsup plus 50 μg gentamicin per ml was added to the wells, and the cells were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2. After 1 h, the DMEMsup plus 50 μg/ml gentamicin was replaced with medium containing 25 μg/ml gentamicin. Wells were sampled at 48 h after infection by aspirating the medium, lysing the macrophages with 0.5 ml of 0.5% Tween-20 and rinsing each well with 0.5 ml of PBS. Viable bacteria were quantified by dilution in sterile PBS and plating on TSA or/and TSA + Kan. Competitive Index, which were adjusted by inocula CFU, were calculated as Mutant CFU/WT CFU per well.

Competitive infection in mice

Female BALB/c ByJ mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) and used at an age of 6–10 weeks. For mixed infection experiments, groups of 2–5 mice were inoculated intraperitoneally with 0.5 ml of PBS containing 2 × 105 CFU of a 1:1 mixture of B. abortus wild type and the isogenic mutant. Infected mice were held in microisolator cages in a Biosafety Level 3 facility. At four weeks post-infection, mice were euthanized by CO2 asphyxiation and the spleens were collected aseptically at necropsy. Spleens were homogenized in 3 ml of PBS and serial dilutions of the homogenate plated on TSA and TSA containing kanamycin, for enumeration of mutant and wild type CFU. Competitive Index was calculated as Mutant CFU/WT CFU recovered from the spleen divided by Mutant CFU/WT CFU in the inoculum. Animal experiments were approved by the UC Davis Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Assay for loss of stationary phase viability

B. abortus cells, freshly re-suspended from TSA plates, were washed once with PBS and diluted into 5 ml TSB or modified minimal E-medium (Kulakov et al., 1997) pH 7.0 with starting OD600 = 0.01. Bacteria were grown in a shaking incubator at optimal condition of 200 rpm, 37°C, and 5% CO2. At time points up to seven days bacterial CFU were enumerated by serial dilution and plating on TSA. Loss of viability during stationary phase was defined as a reduction in bacterial numbers after 72 h incubation. Experiments were repeated at least three times and produced similar results. Results of a representative experiment are shown.

Acid tolerance test

After 24 h of growth in E-medium pH 7.0, bacteria were washed once with PBS and re-suspended in the same volume of E-medium adjusted to pH 7.0, or to pH 5.0 or 3.5 with 1 M Citric Acid. After 5 h incubation, CFU were determined by serial diluting and plating on TSA. Acid tolerance was measured by comparing growth at pH 3.5 or 5.0 to growth at pH 7.0. Experiments were repeated at least three times and produced similar results, and representative results are shown.

Sensitivity to nickel sulfate and sodium azide

To test Brucella sensitivity to heavy metal and respiratory chain inhibitor, a previously described method was used with modification (Endley et al., 2001). Log phase bacteria, obtained after 24 h growth in E-medium pH 7.0, were serially diluted and plated on TSA or TSA supplemented with 0.15 mM NiSO4 and 0.15 mM NaN3. CFU were counted after five days' incubation. Experiments were repeated at least three times, with similar results. Data from a representative experiment are shown.

Measurement of hydrogen peroxide sensitivity

To measure hydrogen peroxide sensitivity, a previously described method was used (Elzer et al., 1994). Briefly, bacteria lawns from exponential growth phase were made by plating 100 μl Brucella growing in E-medium pH 7.0 on TSA plates. A small sterile disk of Whatman paper containing 5 μl 30% H2O2 was placed in the middle of each lawn. After five days' incubation, the zone of bacterial clearance was measured. Experiments were repeated at least three times with triplicate plates. Results from a single representative experiment are shown.

Complementation of the cydX mutant

In order to restore a functional copy of cydX in the mutant, a previously described groEL promoter (Gor and Mayfield, 1992; Lin et al., 1992) corresponding to Brucella abortus 2308 chromosome II DNA coordinates 184149–184551 with engineered restriction enzyme sites was amplified using primers GroEL-P-F and GroEL-P-R and cloned into the pCR2.1 TOPO cloning vector. The insert was excised using SphI and NdeI and ligated into broad host range cloning vector pFlagTEM1 (GeneBank accession number EU44730) (Raffatellu et al., 2005; Sun et al., 2007) to replace lacIq and the trc promoter. cydX, cydB, and cydBX were amplified from Brucella abortus 2308 genomic DNA, respectively, cloned into TOPO vector and then introduced just downstream of the groEL promoter using NdeI and PstI, to generate plasmids pGroEL/CydX, pGroEL/CydB, and pGroEL/CydBX. To show functionality of the GroEL promoter in B. abortus, a DsRed gene, encoding a red fluorescent protein (Shaner et al., 2004), was also cloned in the same way to generate pGroEL/dsRed. In order to monitor CydX expression, a plasmid with a 3×FLAG tag fused at the C terminus of CydX was constructed so that CydX expression as a tagged protein could be conveniently detected by using anti-FLAG monoclonal antibody (Sigma). Briefly, to ensure 3×FLAG—tagged protein expression in Brucella, a promoter demonstrated previously to be constitutively active under in vitro growth conditions (Eskra et al., 2001), corresponding to B. abortus 2308 chromosome II DNA coordinates 1045014 and 1045238 was amplified with primers Promoter-F and Promoter-R. The 226 bp amplicon flanked by KpnI-HpaI and NdeI-SalI was cloned into pCR2.1 TOPO vector and the orientation was chosen in such a way that double digestion with SalI/SacI did not excise the insert. 3×FLAG with two stop codons, amplified from pSUB11 (Uzzau et al., 2001) using primer pair of Flag-F and Flag-R, digested with SalI and SacI, was then ligated with constitutive promoter PBMEII0192 in pCR2.1 TOPO vector. The 270 bp of “PBMEII0192-NdeI-SalI-3×FLAG,” digested as KpnI/SacI fragment, was inserted into the same sites of pBBR1MCS (Elzer et al., 1994) to give rise to pBBR1Flag. Plasmid pCydX/Flag was made by cloning cydX, which was amplified from the B. abortus genome, TOPO-cloned into pCR2.1, and excised as NdeI/XhoI fragment, into NdeI/SalI sites of pFlag (XhoI and SalI sites are compatible). All constructs were confirmed by DNA sequencing to ensure correct insertion and/or in frame expression of fusion proteins. All primers were used in this work are listed in Table A1.

Determining CydX localization and orientation using β-lactamase as a reporter

pFlagTEM1 (Raffatellu et al., 2005; Sun et al., 2007) was used to express β-lactamase fusions to CydX. To express 3×FLAG-tagged β-lactamase as an fusion to the C-terminus of CydX (CydX::TEM1) cydX from B. abortus 2308 was amplified without STOP codon, inserted into pCR2.1 and excised as an NdeI and SalI fragment. This fragment was then cloned into plasmid pFlagTEM1 using NdeI and XhoI. Similarly, to fuse 3×FLAG-tagged β-lactamase to the N terminus of CydX, cydX was amplified and cloned into pFlagTEM1 using XbaI and PstI to express TEM1::CydX. Other fusions were made in the same way or have been already described (Table 1). All constructs were sequenced to ensure in frame expression as Flag tagged TEM-1 fusion proteins.

Fresh bacteria growing on plates were resuspended in TSB. Serial dilutions were made after OD600 was measured. 10 μl of bacteria containing about 103 CFU were spotted on TSA in 96-well plates with 100 μg/ml Carb, or 1 mM IPTG plus 15 μg/ml Cm, or IPTG plus Carb which concentrations range from 0 to 1 mg/ml. Plates were checked after five days' incubation to determine bacterial viability. Survival was scored as the maximum antibiotic concentration permitting growth of B. abortus.

SDS-page and western blotting

To measure expression of 3×FLAG-tagged or/and β-lactamase fusion proteins, B. abortus was cultured in TSB at 37°C with shaking at 200 rpm. After 18 h the OD600 of the cultures ranged from 1.2 to 1.5 and bacteria were pelleted and resuspended in 1X Laemmli sample buffer, heated at 100°C for 5 min, and the total protein equivalent to 1 × 108 CFU loaded per well was then electrophoresed on a 12–15% polyacrylamide gel and transferred to nitrocellulose membrane. Membranes were blocked in 2% non-fat skim milk in PBS for an hour and then probed with Anti-FLAG Monoclonal antibody (1:5000, Sigma) or anti-β-lactamase monoclonal antibody (1:5000, QED Bioscience Inc.). Primary antibody binding was detected using a goat-anti-mouse antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (HRP). HRP activity was detected with a chemiluminescent substrate (NEN). A previously described polyclonal antibody against the B. abortus protein Bcsp31 was used as a loading control (Sun et al., 2005).

Results and discussion

Targeted mutagenesis of small hypothetical ORFs

Using the published genome sequences of B. abortus 2308, B. suis 1330, and B. melitensis 16 M, we identified ORFs with the potential to encode proteins smaller than 15 kDa. Thirty of these ORFS were selected for mutagenesis based on having no predicted function and lack of annotation in the genome of A. tumefaciens C58. Some of these proteins were assigned families of conserved proteins such as clusters of orthologous genes (COG) with only general functional predictions or families containing conserved domains of unknown function (DUF). Precise deletions of each ORF were constructed and marked with a kanamycin resistance gene (Tables 1, 2). Mutations were confirmed by PCR, and/or by Southern blot using probes specific to the deleted gene. For 30 genes we could confirm inactivation (See Figure A1 for details of the mutagenesis procedure).

Table 2.

Small ORFs (<15 kDa) with no assigned function, which are highly conserved in Brucella species.

| B. abortus 2308 ORFa | B. suis 1330 ORFa | B. melitensis 16M ORFa | Annotationb | In vitro CIc | In vivo CId |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BAB2_0068e | BRA0069 | BMEII0025 | Type IV secretion system protein virB1 | 0.0023 | 0.0001 |

| BAB1_0061 | BR0064 | BMEI1881 | hypothetical protein | 0.7493 | 1.2039 |

| BAB1_0355 | BR0325 | BMEI1597 | COG1380 LrgA family protein [general function prediction only] | 1.3655 | 0.0153 |

| BAB1_0513 | BR0488 | BMEI1447 | hypothetical protein | 5.6537 | 1.0448 |

| BAB1_0581 | BR0557 | BMEI1376 | COG3654; prophage maintenance system killer protein [general function prediction only] | 1.8387 | 0.5577 |

| BAB1_0626 | BR0602 | BMEI1339 | hypothetical protein | 3.6877 | N |

| BAB1_0743 | BR0725 | BMEI1227 | hypothetical protein [possible relationship to acetyltransferases] | 0.6340 | 0.6160 |

| BAB1_0992 | BR0973 | BMEI1005 | hypothetical protein | 1.1191 | 0.4853 |

| BAB1_1106 | BR1083 | BMEI0899 | COG3617; prophage antirepressor [possible function in transcription] | 1.2815 | 0.6963 |

| BAB1_1194 | BR1173 | BMEI0813 | hypothetical protein | 1.2322 | 0.3799 |

| BAB1_1204 | BR1181 | BMEI0806 | hypothetical protein | 1.3258 | 0.4248 |

| BAB1_1262 | BR1241 | BMEI0751 | hypothetical protein | N | 1.5608 |

| BAB1_1390 | BR1370 | BMEI0633 | COG0239; possible integral membrane protein | N | 1.8630 |

| BAB1_1392 | BR1372 | BMEI0631 | COG3467; predicted flavin nucleotide binding protein [general function prediction only] | N | 1.4038 |

| BAB1_1743 | BR1730 | BMEI0308 | hypothetical protein | 0.6744 | N |

| BAB1_1748 | BR1736 | BMEI0304 | COG1607, Acyl-CoA hydrolase [Lipid metabolism] | N | 1.3140 |

| BAB1_1939 | BR1938 | BMEI0127 | hypothetical protein | 0.4634 | 0.4569 |

| BAB1_2041 | BR2041 | BMEI0030 | DUF188 superfamily | 2.6421 | 0.5280 |

| BAB2_0160 | BRA0162 | BMEII1078 | COG4893; uncharacterized protein conserved in bacteria | 0.6152 | 1.1670 |

| BAB2_0170 | BRA0175 | BMEII1067 | DUF465 superfamily; putative cytosolic protein | 0.2584 | N |

| BAB2_0761 | BRA0476 | BMEII0789 | hypothetical protein | 0.5177 | N |

| BAB2_0726 | BRA0512 | BMEII0758 | Pfam01873; YbgT-like protein | 0.0079 | 0.0001 |

| BAB2_0470 | BRA0769 | BMEII0522 | Pfam05635; family of hypothetical proteins | 0.0002 | 0.0025 |

| BAB2_0450 | BRA0787 | BMEII0503 | hypothetical protein | 0.0435 | 0.0180 |

| BAB2_0415 | BRA0819 | BMEII0468 | hypothetical protein | 1.0595 | 1.2254 |

| BAB2_0400 | BRA0836 | BMEII0454 | hypothetical protein | 1.0501 | 1.8400 |

| BAB2_0232 | BRA1000 | BMEII0296 | hypothetical protein | N | 0.9205 |

| BAB2_1072 | BRA1113 | BMEII0186 | pemK family protein [possible regulator] | 5.1792 | 0.5605 |

| BAB2_1087 | BRA1130 | BMEII0169 | Hypothetical protein [flagellar locus] | N | 1.0841 |

| BAB2_1136 | BRA1177 | BMEII0118 | DUF1634 superfamily | 0.2300 | 0.4828 |

ORF number from NCBI.

Followed B. suis 1330 assignment.

Competitive index (CI): Calculated as Mean Mutants/WT from at least three experiments. N: Not tested.

Competitive index (CI): Calculated as Mean Mutants/WT in spleen of 2–5 mice. N: Not tested.

A previously characterized virB1 mutant (BA41) serves as attenuation phenotype control.

Mutants BAB2_0726, BAB2_0470, and BAB2_0450 are highly attenuated both in cultured macrophages in vitro and in a mouse model in vivo.

In order to determine whether any of the genes inactivated in the collection of mutants were required for intracellular survival we tested the ability of 30 mutants to survive and replicate for 48 h within cells of the macrophage-like line J774. All the mutants had similar growth rates as wild type B. abortus when growing in TSB (data not shown). Three mutants, BAB2_0726, BAB2_0470, and BAB2_0450 exhibited marked intracellular growth defects in a competitive infection against wild type in J774 macrophage-like cells (Table 2). Macrophage infection experiments were repeated with individual mutants (non-competitive infection) and exhibited the same attenuation phenotype as in mixed infection. After 48 h infection, the intracellular CFU of mutants BAB2_0726, BAB2_0470, and BAB2_0450 was decreased 2–3 orders of magnitude compared with wild type although they were less attenuated than ADH3 (virB2), a mutant defective in the type IV secretion system (den Hartigh et al., 2004) (Table 2).

We also investigated the role of these small hypothetical genes in persistent infection in a mouse model. To minimize the variation caused by different inoculum doses, we conducted competitive infection experiments, in which we inoculated mice IP with a 1:1 mixture of each mutant with wild type B. abortus 2308. Four weeks after inoculation, bacterial load in spleens were determined by differential plating on TSA with or without kanamycin and the competitive index was calculated as CFU of mutants/CFU of wild type and corrected for mutant/wild type ratio in each inoculum. Most of the mutants were recovered in a number similar to the wild type from the spleen of infected mice, suggesting that these mutants have equal ability to persist for up to four weeks. However, three mutants were attenuated compared with wild type, having competitive indices ranging from 0.018 to 0.001. Consistent with the attenuation phenotype observed in cultured mouse macrophages in vitro, mutants BAB2_0726, BAB2_0470, and BAB2_0450 were highly attenuated in vivo (Table 2). A fourth mutant, BAB1_0355, was found to be attenuated in the in vivo competitive infection assay, but not in J774 cells (Table 2). BAB1_0355 is related to LrgA of Staphylococcus aureus, which encodes a regulator of murein hydrolase (Groicher et al., 2000). BAB2_0450 is upstream of a predicted carbonic anhydrase, which has been characterized as a target for anti-Brucella drugs (Joseph et al., 2010), so its function may be related to that of the carbonic anhydrase, or its deletion may have a polar effect on carbonic anyhdrase expression. BAB2_0470 belongs to a family of proteins designated “S23 ribosomal proteins” which share similarity to proteins of unknown function encoded by an intervening sequence in the 23S ribosomal genes of Leptospira and Coxiella burnetii (Ralph and McClelland, 1993; Afseth et al., 1995).

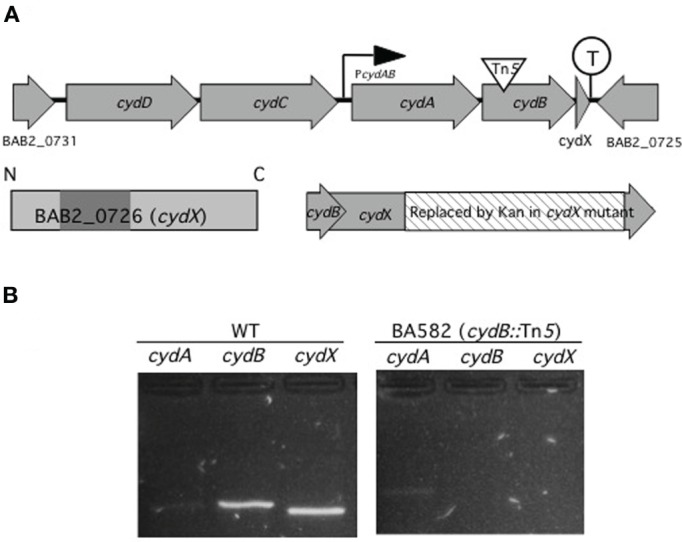

BAB2_0726 is located in the 3′ end of cyd operon and the phenotype of a deletion mutant is similar to that of cydB mutants

The in vitro and in vivo attenuation phenotypes of mutants BAB2_0726, BAB2_0470, and BAB2_0450 raised the question of how these small hypothetical proteins could contribute to Brucella virulence. While analysis of BAB2_0470 and BAB2_0450 did not reveal any clues to their function, by looking the gene organization of BAB2_0726 in Brucella abortus 2308 genome we found that BAB2_0726 is located at the 3′ end of the cydAB operon, a gene cluster encoding subunits of a high affinity terminal oxidase of the oxygen respiratory chain (Endley et al., 2001) (Figure 1A). This gene organization pattern is well conserved in all sequenced Brucella genomes. The localization of a small peptide downstream of cydB was also reported in Escherichia coli, where it has been designated orfC or ybgT (Muller and Webster, 1997; Hemm et al., 2010). This finding led us to designate BAB2_0726 as cydX, since cydC (BAB2_0729) and cydD (BAB2_0730) immediately upstream of cydA were already assigned in E. coli to genes encoding a bacterial glutathione transporter (Pittman et al., 2005).

Figure 1.

cydA, cydB, and cydX are organized and transcribed as a gene cluster. (A) Genetic map of the cyd locus in B. abortus 2308 chromosome II. cydA and cydB encode two proteins with similarity to subunit I and II of cytochrome bd-1 terminal oxidase in E. coli. Upstream of cydA and cydB are two predicted ABC transporter genes with similarity to E. colicydD and cydC. Overlapping 23 bp with cydB, cydX encodes a 64 aa protein with one predicted transmembrane domain (shaded), spanning residues 17–35. While no promoter is predicted in front of cydD there is a promoter (PcydAB), possibly driving transcription of cydA, cydB, and cydX. A transcriptional terminator (circled T) is located between cydX and its adjacent open reading frame BAB2_0725. In BA582 (cydB::Tn5) a transposon is inserted in cydB (triangle) while in cydX::Kan part of cydX (hatched) is replaced by a kanamycin resistance determinant without disrupting cydB. (B) Analysis of the cyd gene cluster by RT-PCR. PCR products for the indicated primers with wild type (WT) or cydB::Tn5 mutant (BA582) as a template are shown. The sizes of the predicted amplicons for cydA, cydB, and cydX are 247 bp, 243 bp, and 204 bp, respectively. Control reactions in which reverse transcriptase were omitted had no amplification product (not shown).

Since based on in silico analysis, cydA, cydB, and cydX are predicted to be transcribed together from a promoter upstream of cydA, we determined whether insertional activation of cydB would be polar on cydX expression (Figure 1B). To this end, RT-PCR was performed to assay expression of cydA, cydB, and cydX in B. abortus 2308 (WT) or an isogenic Tn5 insertion in cydB (Endley et al., 2001). While a faint product for cydA was observed in both WT and the cydB mutant, neither cydB nor cydX amplification products were found in the cydB mutant, suggesting a polar effect of the cydB mutation on cydX expression. These results suggested that cydX is transcribed together with the cytochrome bd oxidase subunits encoded by cydA and cydB.

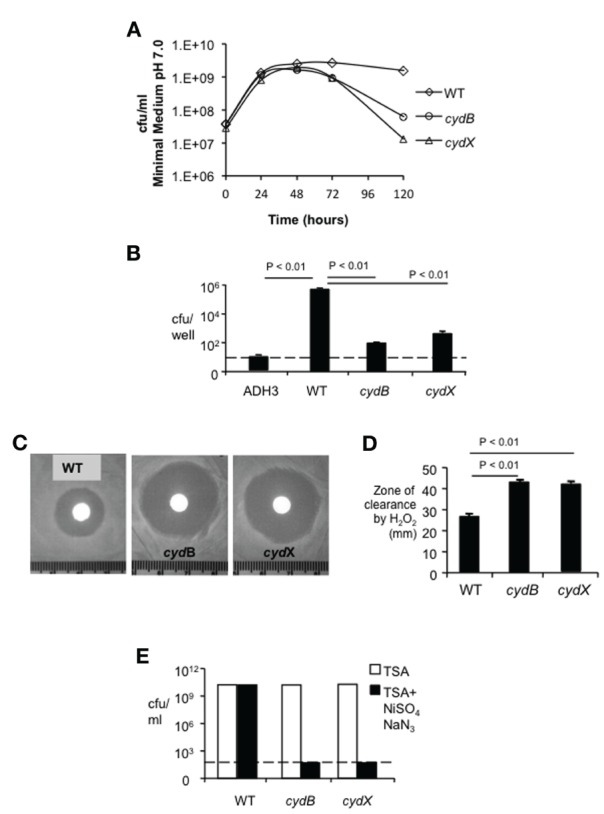

To determine whether CydX is functionally related to cytochrome bd oxidase, we determined whether deletion of cydX affects stationary phase viability, a phenotype that is defective in a B. abortus cydB mutant (Endley et al., 2001). As shown in Figure 2A, when grown in minimum medium with starting OD600 = 0.05 all Brucella strains replicated equally until they reached stationary phase (48–72 h). However, similar to the cydB mutant BA582, the viability of the mutant deleted for cydX declined rapidly as the incubation time progressed, while wild type B. abortus survived for up to five days. Similar results were observed when the mutants were grown in rich medium (TSB) (data not shown). Our finding that deletion of cydX impaired intracellular growth (Table 2) and led to loss of viability in stationary phase (Figure 2A) prompted us to determine whether this mutant shared other defects associated with inactivation of cytochrome bd oxidase (Endley et al., 2001). Similar to a cydB mutant, the B. abortus mutant lacking cydX exhibited significantly (P < 0.01) increased sensitivity to hydrogen peroxide compared with wild type B. abortus (Figures 2C,D).

Figure 2.

Characterization of the cydX mutant. (A) Loss of viability in stationary phase. Growth kinetics of B. abortus in modified E medium pH 7.0 was monitored by CFU counting at each indicated time point. Each data point represents results of a single assay that was repeated twice. (B) Intracellular survival of the cydX mutant in J774 macrophages. Strain ADH3 (virB2) served as an attenuated control. Data are represented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of triplicate samples from one assay that was repeated twice with the same result. Significance of differences was analyzed by One-Way analysis of variance (ANOVA), with a P value of less than 0.05 considered as significant. The dotted line indicates the limit of detection. (C and D) Sensitivity to hydrogen peroxide. Log-phase bacteria were plated on TSA and oxidative killing was determined by measuring the diameter of clear zone surrounding a paper disk soaked with 5 μl of 30% hydrogen peroxide. Large zones of bacterial growth inhibition were observed in both cydX and cydB mutants (Typical photographs were shown). Data in (D) are represented as means of a single assay with five samples ± SD, that was repeated once with the same result. Significance of differences was analyzed by One-Way ANOVA, with P values for pairwise comparisons with P < 0.05 indicated. (E) Sensitivity to sodium azide plus nickel sulfate. Log-phase bacteria growing TSA or TSA supplemented with 0.15 mM NiSO4 and 0.15 mM NaN3 were serially diluted and were plated on TSA for enumeration of surviving bacteria. Survival of treatment with sodium azide plus nickel sulfate was calculated as the ratio of CFU on TSA + NiSO4 /NaN3 to CFU on TSA. While these ratios were approximately 1 for wild type B. abortus, neither cydX mutant nor the cydB mutant survived in the presence of these chemicals. A dotted line indicates the limit of detection of this assay.

Disruption of cytochrome bd oxidase increases sensitivity to the respiratory chain inhibitor sodium azide and the uncoupling agent nickel in both Brucella and E. coli (Wall et al., 1992; Edwards et al., 2000; Endley et al., 2001). Similarly to the B. abortus cydB mutant, the mutant lacking cydX was highly sensitive to the combination of sodium azide plus nickel sulfate, compared to wild type B. abortus (Figure 2E). The data suggested that the small protein CydX is required for the function of cytochrome bd oxidase in B. abortus.

Complementation of the cydX mutant leads to partial restoration of cyd phenotypes and improves intracellular growth in mouse macrophages.

To confirm that the phenotypes of the cydX::Kan mutant result from deletion of cydX, we conducted complementation experiments to satisfy the molecular Koch's postulates (Falkow, 1988). To this end, constructs encoding either CydX or CydX::3 ×-FLAG were generated. The groEL promoter, known to be induced during growth in macrophages (Lin and Ficht, 1995), was used to drive cydX expression. As a control for the expression of cydX, we expressed the gene encoding the fluorescent protein DsRed from the same promoter and confirmed fluorescence of the recombinant strain (not shown). Immunoblot analysis of Brucella expressing CydX::FLAG with anti-Flag antibody revealed a major band of 10 kDa, a size matching the predicted size of CydX (8 kDa) and 3×FLAG (2 kDa), indicating that CydX is indeed expressed as protein in Brucella (not shown). Both the cydX mutant and BA582 (cydB::Tn5) were transformed with constructs expressing cydX, cydB, or cydBX to determine whether the phenotypes associated with cytochrome bd oxidase deficiency could be complemented (Figure 3). Complementation of both cydB and cydX mutants with their respective genes restored stationary phase viability (Figure 3A), and complementation of this phenotype in the cydX mutant was unaffected by addition of the 3X-FLAG tag to the C terminus of CydX. As expected, the construct expressing DsRed failed to complement the cydX mutant since it expressed an irrelevant control protein.

Figure 3.

Complementation of cydX mutation. Plasmid-encoded copies of cydB or cydBX, cydXor cydX-FLAG were introduced into cydX and cydB mutants. A plasmid expressing DsRed served as a negative control. (A) Restoration of stationary phase viability was determined as decribed in Figure 2. (B) Sensitivity to 3% Hydrogen peroxide was assayed as described in Figure 2. Significance of differences was analyzed by One-Way ANOVA, with P values for pairwise comparisons with P < 0.05 indicated. (C) Sensitivity to sodium azide plus nickel sulfate was assayed as described in Figure 2. (D) Sensitivity to acid pH. Viability of cultures incubated for 5 h in E-medium adjusted to pH 7.0 or pH 3.5 was assayed as described in the Materials and Methods. Each data point represents results of a single assay that was repeated twice. (E) Survival in J774 mouse macrophages. J774 cells were infected with cydX or cydB mutants containing indicated plasmids. Cells were lysed at 24 and 48 h post-infection. Bacterial CFU were determined by serial dilution and plating on TSA. Data represent the mean of triplicate samples ±SD from a single experiment of three replicates with similar results. Significance of differences was analyzed by One-Way ANOVA, with P values for pairwise comparisons with P < 0.05 indicated. Dotted lines indicate the limit of detection.

Complementation of hydrogen peroxide sensitivity in the cydX mutant was also observed with constructs expressing CydX or CydX::Flag, as evidenced by the reduced zone of clearance around filter disks containing hydrogen peroxide (Figure 3B). Introduction of a construct encoding cydBX into the cydB mutant (BA582) resulted in greater resistance to H2O2 compared to introduction of a construct encoding cydB only (Figure 3B). This result suggested that the Tn5 insertion in cydB in BA582 could have a polar effect on expression of cydX.

A second phenotype of the cydX mutant, lack of growth in the presence of nickel and azide, was also complemented to the wild type level by introduction of an intact copy of cydX or cydX::3x-Flag, similar to what was observed for complementation of the cydB mutant (Figure 3C).

Two cydX mutant phenotypes, sensitivity to acidic conditions and intracellular survival in J774 macrophages, were only partially complemented by introduction of constructs expressing CydX or CydX::FLAG (Figures 3D,E). In the experiment shown in Figure 3E, there were no remarkable differences between CydX mutant transformed with pGroEL/dsRed, pGroEL/CydX, or pCydX/Flag at 24 h post-infection. However, at 48 h post-infection, the CFU recovered for mutants complemented with CydX or CydX::Flag were markedly higher than that of mutant transformed with pGroEL/dsRed (control). Complementation of the cydX mutant with constructs expressing CydX or CydX::FLAG resulted in partial restoration of intracellular survival, with a net increase in bacterial numbers between 24 and 48 h. In contrast, the cydX mutant complemented with the DsRed-expressing construct failed to replicate during this time and actually decreased in numbers. Based on this observation we concluded that the intracellular growth defect of cydX mutant with impaired cytochrome bd oxidase activity could be partially rescued by providing wild type CydX or CydX::FLAG in trans. Interestingly, expression of cydX together with cydB increased survival of the cydB mutant more then complementation with cydB alone (Figure 3E). However, expression of cydX alone in the same copy number did not completely restore intracellular replication of the cydX mutant.

It was of interest that while some phenotypes of the cydX mutant, such as sensitivity to H2O2 or nickel sulfate/sodium azide, could be complemented to the level of the wild type, survival of pH 3.5 or intracellular replication of the cydX mutant were restored to a lesser degree. It is possible that these two former phenotypes require only some degree of cytochrome bd oxidase activity, whereas intracellular growth and acid resistance represent stress conditions that may require either precise regulation of cydABX expression or specific ratios of CydX to CydA and CydB. Since CydX is predicted to be an integral cytoplasmic protein (see below), it is conceivable that free CydX that is not associated with a cytochrome bd oxidase complex might insert into the cytoplasmic membrane and destabilize other cell envelope functions that are essential for resistance to acidic pH and intracellular replication. Our finding that expression of cydX in a cydB mutant lacking cytochrome bd oxidase actually decreased stationary survival (Figure 3A) is consistent with this interpretation.

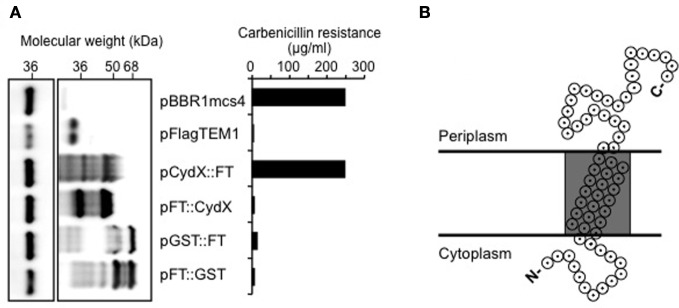

The C terminus of CydX is located in the periplasm

CydX is predicted to have a single transmembrane domain of 15–17 residues. Since components of cytochrome bd oxidase in E. coli are located at the cytoplasmic membrane (Miller and Gennis, 1983; Green et al., 1984; Miller et al., 1988) we hypothesized that CydX could mediate its function by colocalizing with CydAB at the cytoplasmic membrane, where it might serve to tether the enzymatic components of the oxidase. To test this hypothesis, we performed membrane fractionation of B. abortus, which failed to yield a cytoplasmic membrane fraction of sufficient purity to give conclusive results (data not shown). As a second approach we constructed N- and C-terminal fusions of CydX to TEM-1 β-lactamase (Zhang et al., 2004) to determine the topology of CydX in the cytoplasmic membrane. To this end, we designed two constructs by cloning cydX in front or behind TEM-1 β-lactamase (Datta and Kontomichalou, 1965) with a 3×FLAG epitope replacing the TEM-1 signal sequence. Both constructs of pCydX/FT (FT stands for 3×FLAG::TEM1) and pFT/CydX were DNA sequenced to ensure in-frame expression of Cyd::FT or FT::CydX fusions. Since β-lactamase only confers resistance to β-lactam antibiotics if it localizes to the periplasm, we could conclude based on ampicillin resistance of each recombinant strain whether the TEM-1 domain was localized in the periplasm. As a control for a resident cytosolic protein we constructed a Glutathione S-transferase (GST) β-lactamase fusions. The GST constructs and pFlagTEM1, which is the empty vector to make CydX β-lactamase fusions, were used as negative controls. As a positive control we used pBBR1MCS4, which encodes β-lactam resistance. Expression of CydX::FT allowed Brucella to survive a concentration of up to 250 μg/ml, of carbenicillin, a maximal concentration similar to that of positive control pBBR1MCS4, whereas the other strains tested were sensitive to 20 μg/ml of carbenicillin (Figure 4A). This result indicated that the β-lactamase moiety of CydX::FT was located in the periplasm, while in FT::CydX, TEM-1 was retained in the cytoplasm. To exclude the possibility that the carbenicillin sensitivity was due to low or absent expression of β-lactamase fusions in those strains, we performed immunoblot analysis of bacterial lysates using a monoclonal antibody specific to TEM-1 β-lactamase (QED Bioscience Inc.). High levels of β-lactamase fusion protein expression were detected in all but the pBBR1MCS4 transformed Brucella, which could be attributed to the lower expression from a normal promoter, compared to the IPTG inducible trc promoter in the other constructs, since the TEM-1 constructs share identical sequences to the bla gene in pBBR1MCS4 (Figure 4A). Based on our current understanding about cytochrome bd oxidase in other organisms we predict that Brucella CydX is inserted in cytoplasmic membrane, with its N terminus at the cytosolic face and C terminus in the periplasm, as depicted in Figure 4B.

Figure 4.

The C-terminus of CydX is located in the periplasm of B. abortus. (A) Western Blot showing expression levels of β-lactamase fusions to CydX and Glutathione-S-transferase (GST; a cytoplasmic control). Blots were probed with a monoclonal antibody against TEM-1 β-lactamase (right blot). As a loading control, the B. abortus protein Bcsp31 detected using a polyclonal antibody (shown on the left) [Sun et al. (2005)]. (B) Maximum concentration of carbenicillin allowing growth of B. abortus expressing each β-lactamase fusion protein. Plasmid pBBR1mcs4 is a positive control that expresses β-lactamase resistance. pFlagTEM1 is the plasmid carrying TEM-1 β-lactamase lacking its N-terminal sequence and was used for generating N- and C-terminal fusions to CydX and GST. (C) Proposed topological model for CydX in Brucella based on current understanding of cytochrome bd quinol oxidase in E. coli and predicted single transmembrane domain (shaded area) in CydX protein sequence.

In conclusion, we have identified a small protein, CydX (BAB2_0726) that is co-regulated with CydAB, and is required for full function of cytochrome bd oxidase in B. abortus. This terminal oxidase is used by Brucella spp. to survive inside eukaryotic cells, where it contributes to intracellular replication (Endley et al., 2001; Loisel-Meyer et al., 2005; Wu et al., 2006). Interestingly, in contrast to B. abortus, in which cydB mutants were highly attenuated, B. suis cydB mutants were hypervirulent, suggesting different use of terminal oxidases in these two species (Jimenez de Bagues et al., 2007). Additional evidence for CydX expression during in vitro growth of B. abortus was recently provided by a proteomic study (Lamontagne et al., 2010). The requirement of CydX for cytochrome bd oxidase function may be shared with other bacteria expressing cytochrome bd oxidase, such as E. coli and S. Typhimurium, since a small protein YbgT was identified downstream of the cydB gene in these two organisms (Alix and Blanc-Potard, 2009; Hemm et al., 2010). In E. coli, cytochrome bd-I oxidase was shown to assemble into large respiratory domains in the cytoplasmic membrane (Lenn et al., 2008), so the insertion of CydX into the cytoplasmic membrane suggests that it might play a role in organizing these complexes at the cytosolic face of the cytoplasmic membrane or might be required for their terminal oxidase activity. Further experimentation will be needed to determine the precise mechanism by which CydX contributes to cytochrome bd oxidase function.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by PHS grant AI050553 to Renée M. Tsolis.

Appendix

Figure A1.

Strategy for Allelic Exchange Mutagenesis. See Materials and Methods for explanation.

Table A1.

Primers used in this work.

| Primer | Sequence* | Description |

|---|---|---|

| GBRORF0459 DN-F | TCCCCCGGGAAAATAATTGACCATGGCΔ | ΔBAB1_0061 |

| GBRORF0459 DN-R | AACTGCAGGGGCAGGCCCGCCGCCT | |

| GBRORF0459 UP-F | GTGCACCGCATTTATTGCGT | |

| GBRORF0459 UP-R | TCCCCCGGGTTGCAGATCAAAGAGCG | |

| GBRORF0206 DN-F | TCCCCCGGGAGCCTGCGTTATGCTGCCCGG | ΔBAB1_0355 |

| GBRORF0206 DN-R | AAACTGCAGCACCACGAAAATGGCCGTG | |

| GBRORF0206 UP-F | GCAGGCGCTCAAAATAATGTG | |

| GBRORF0206 UP-R | TCCCCCGGGCTTTGCGGGGGGCGTTCA | |

| GBRORF0049 DN-F | TCCCCCGGGATAGGTGTGCGCCCCGC | ΔBAB1_0513 |

| GBRORF0049 DN-R | AACTGCAGAAGTCGAATCCGCCCTC | |

| GBRORF0049 UP-F | CCGGCCTTCATGAGCCGGAT | |

| GBRORF0049 UP-R | TCCCCCGGGTCGTTTTGCGGGCCAAC | |

| GBRORF2128 DN-F | TCCCCCGGGCCGTTGTTATAAACGACGAC | ΔBAB1_0581 |

| GBRORF2128 DN-R | AAACTGCAGAGCTTTTACCAAAGAACAGG | |

| GBRORF2128 UP-F | GGCTCATACCCGCCAAATGCA | |

| GBRORF2128 UP-R | TCCCCCGGGTTCAGCCGTTCCAGCACTT | |

| GBRORF2083 DN-F | TCCCCCGGGAGAAGAAACTGTTGTT | ΔBAB1_0626 |

| GBRORF2083 DN-R | AAACTGCAGGTCCTTGTCGTCTTCAACA | |

| GBRORF2083 UP-F | CTGCTCAGATCGCCGGATGGC | |

| GBRORF2083 UP-R | TCCCCCGGGATTTATTGGCTGTCATATTGTT | |

| GBRORF1960 DN-F | TCCCCCGGGACGACCTGCTTTCGCAGAT | ΔBAB1_0743 |

| GBRORF1960 DN-R | AAACTGCAGCCCGTATGTAACAATGAG | |

| GBRORF1960 UP-F | CCTATGCAGCTTCCACCATTG | |

| GBRORF1960 UP-R | TCCCCCGGGTAAGTTTGTGTGCTCATTC | |

| GBRORF1747 DN-F | TCCCCCGGGCTATCCCGCGACGAGCG | ΔBAB1_0960 |

| GBRORF1747 DN-R | AAACTGCAGAAGCTGATCTTCATCGAT | |

| GBRORF1747 UP-F | GATAGTGCCAGGATAAGGAAA | |

| GBRORF1747 UP-R | TCCCCCGGGATGGAAAACTTCATCATT | |

| GBRORF1716 DN-F | TCCCCCGGGTCAAGAAATTCAACCTT | ΔBAB1_0992 |

| GBRORF1716 DN-R | AACTGCAGATCGCCTGATGGCAATC | |

| GBRORF1716 UP-F | TCCGATTGGGCGTAGCTTAC | |

| GBRORF1716 UP-R | TCCCCCGGGTACTGGCGCTGGCGTCT | |

| GBRORF1608 DN-F | TCCCCCGGGACGCTCATCACCTTGACGGA | ΔBAB1_1106 |

| GBRORF1608 DN-R | AAACTGCAGCCCTCCCGCCCCTCACGT | |

| GBRORF1608 UP-F | GGCGAGAGGGATGAAGATCGA | |

| GBRORF1608 UP-R | TCCCCCGGGTCCATGAAGTTGAAGATTT | |

| GBRORF1520 DN-F | TCCCCCGGGCGATTCCATTAAAACAG | ΔBAB1_1194 |

| GBRORF1520 DN-R | AACTGCAGAATCATGGCTCTAAATC | |

| GBRORF1520 UP-F | CCTTGGCATGGCGCTGCGTC | |

| GBRORF1520 UP-R | TCCCCCGGGCCTGTCCTTCGCTCGGG | |

| GBRORF1512 DN-F | TCCCCCGGGCGTTGCCGTCGGCCATAG | ΔBAB1_1204 |

| GBRORF1512 DN-R | AACTGCAGCCTGCGGTCCATTCGTA | |

| GBRORF1512 UP-F | GTTGTGCTACTTCATTTACG | |

| GBRORF1512 UP-R | TCCCCCGGGTCGCCGCACCGCCTG | |

| GBRORF1452 DN-F | TCCCCCGGGCGACGACGAAGAGGAAGAG | ΔBAB1_1262 |

| GBRORF1452 DN-R | AAACTGCAGACGCCTTCGTTCATCT | |

| GBRORF1452 UP-F | CAGTGCAGGAACCTTATTGCG | |

| GBRORF1452 UP-R | TCCCCCGGGACTCGGATGTGCTTCAATAGC | |

| GBRORF1325 DN-F | TCCCCCGGGTTTGCCGCATGGCTCGACGC | ΔBAB1_1390 |

| GBRORF1325 DN-R | AAACTGCAGCGACGGAGTGGCGGCTCT | |

| GBRORF1325 UP-F | GGCCAGATAGCCCGGAACGA | |

| GBRORF1325 UP-R | TCCCCCGGGACCCACATAACATCTAAAGGA | |

| GBRORF1323 DN-F | TCCCCCGGGCATCAGGCGGAGTGACC | ΔBAB1_1392 |

| GBRORF1323 DN-R | AAACTGCAGGACGTCGGCCTCCATTCTC | |

| GBRORF1323 UP-F | GCTTGTGACGCTGGAGGAAAA | |

| GBRORF1323 UP-R | TCCCCCGGGTCCGACATTTCCGTTATCAAC | |

| GBRORF0969 DN-F | ACCCCGGGCTTTCACCTGCACGAAG | ΔBAB1_1743 |

| GBRORF0969 DN-R | ACCTGCAGACCTATGGCGTGGATTCG | |

| GBRORF0969 UP-F | ACGCGCGATGGCTCAATGC | |

| GBRORF0969 UP-R | ACCCCGGGCAGGATTTTGGTCAC | |

| GBRORF0964 DN-F | TCCCCCGGGTATCCCCATCGAGCTTGCC | ΔBAB1_1748 |

| GBRORF0964 DN-R | AAACTGCAGGATCGCCCGAATGCGATT | |

| GBRORF0964 UP-F | CCGACACCCAGATTCATGCGC | |

| GBRORF0964 UP-R | TCCCCCGGGTTCTTGAAAACGTCTTTCATG | |

| GBRORF0765 DN-F | TCCCCCGGGTTGATGTCCTTCAATTC | ΔBAB1_1939 |

| GBRORF0765 DN-R | AACTGCAGGATGCGCCAGACGAA | |

| GBRORF0765 UP-F | ACGGCGCATGCTTCTTGTCG | |

| GBRORF0765 UP-R | TCCCCCGGGGGGCTGGTTCGGACAAT | |

| GBRORF0663 DN-F | TCCCCCGGGCAATACGTTCCGGCGAAG | ΔBAB1_2041 |

| GBRORF0663 DN-R | AACTGCAGGTGTCGAGAAGCTCAAG | |

| GBRORF0663 UP-F | CCTGCATCTGCAAAGGCC | |

| GBRORF0663 UP-R | TCCCCCGGGTGGTTGATGCCATCATT | |

| GBRORFA0247 DN-F | TCCCCCGGGTGTGCGCGGCCAAGATAA | ΔBAB2_0160 |

| GBRORFA0247 DN-R | AAACTGCAGCCCTGCAAAATTTCCTGT | |

| GBRORFA0247 UP-F | CCATGGGTATGATGATGCTGC | |

| GBRORFA0247 UP-R | TCCCCCGGGTTTCCCGCAAGCTGCAAGC | |

| GBRORFA0258 DN-F | TCCCCCGGGCGCTTGCCGCCGCCTGATT | ΔBAB2_0170 |

| GBRORFA0258 DN-R | AAACTGCAGATTGGTGAGGGGGCGAAA | |

| GBRORFA0258 UP-F | CCGCTTCGTCGAACAGGCAAC | |

| GBRORFA0258 UP-R | TCCCCCGGGGCGTATTCGACATTCTAC | |

| GBRORFA1086 DN-F | TCCCCCGGGCTTTCCATCGCCTGAAACTGT | ΔBAB2_0232 |

| GBRORFA1086 DN-R | AAACTGCAGGGGAAATGTAGGAGGTAG | |

| GBRORFA1086 UP-F | GAAGAAGGCCTTATCTGATCA | |

| GBRORFA1086 UP-R | TCCCCCGGGCCGCCCCCTCTTCACCATGA | |

| GBRORFA0924 DN-F | TCCCCCGGGTGGAACACTCTCCCTGC | ΔBAB2_0400 |

| GBRORFA0924 DN-R | AACTGCAGTCCTTTGCTGCCTTTGT | |

| GBRORFA0924 UP-F | GCGTATCAGCCATGCAGGCG | |

| GBRORFA0924 UP-R | TCCCCCGGGTAAGACGTAGGTTAGGC | |

| GBRORFA0907 DN-F | TCCCCCGGGCAGCAATGGTTCGACGAAAG | ΔBAB2_0415 |

| GBRORFA0907 DN-R | AAACTGCAGACAAATGCACCGAGGAT | |

| GBRORFA0907 UP-F | GCGGATCGGCGAGACTTTTCC | |

| GBRORFA0907 UP-R | TCCCCCGGGCAGTTCCATGACCCGTTCT | |

| GBRORFA0873 DN-F | TCCCCCGGGCGCTTCCCGCCTACTACTGA | ΔBAB2_0450 |

| GBRORFA0873 DN-R | AAACTGCAGCCATAATGTCCGCAAAC | |

| GBRORFA0873 UP-F | GGTTTTGCAGTGGCTTCCAG | |

| GBRORFA0873 UP-R | TCCCCCGGGGGCAGCAAACTGGACATT | |

| GBRORFA0854 DN-F | TCCCCCGGGCTTCTCATCCGCAAGCTA | ΔBAB2_0470 |

| GBRORFA0854 DN-R | AAACTGCAGATAGCGCGGCTTGTGCAC | |

| GBRORFA0854 UP-F | CATGTTCAAGCGCACGATCCG | |

| GBRORFA0854 UP-R | TCCCCCGGGATATGAATTGATTGACATCAC | |

| GBRORFA0598 DN-F | TCCCCCGGGCAACAAGCACCACTGAAATG | ΔBAB2_0726 |

| GBRORFA0598 DN-R | AAACTGCAGATATGGCCCGGCGCGGCAT | |

| GBRORFA0598 UP-F | CGGCGGCTTCGTGCCGGCGC | |

| GBRORFA0598 UP-R | TCCCCCGGGTTGCTCTCATCCTCGATCA | |

| GBRORFA0563 DN-F | TCCCCCGGGCCTATGCAGAAGCCCTG | ΔBAB2_0761 |

| GBRORFA0563 DN-R | AACTGCAGAAGAGAATATGGCCGTC | |

| GBRORFA0563 UP-F | CGCTTTTTCCCGGCAGCATG | |

| GBRORFA0563 UP-R | TCCCCCGGGTTCGGTTTCAGTTTCTC | |

| GBRORFA0429 DN-F | TCCCCCGGGCTGAAGCAGAACTCAAGAAAGTT | ΔBAB2_0862 |

| GBRORFA0429 DN-R | AAACTGCAGTTTAATGAGATATTTC | |

| GBRORFA0429 UP-F | CAATGCAGGCGCAATTGCAAC | |

| GBRORFA0429 UP-R | TCCCCCGGGAAGAGAGCCTTAATCATTTCC | |

| GBRORFA1199 DN-F | TCCCCCGGGTTCCCGTTTCTGCGACG | ΔBAB2_1072 |

| GBRORFA1199 DN-R | AAACTGCAGATAACGGCATCAGCACCG | |

| GBRORFA1199 UP-F | GGGCACTTCTTCTGCCACGT | |

| GBRORFA1199 UP-R | TCCCCCGGGATAGTTTCGGCTTCGAT | |

| GBRORFA0014 DN-F | TCCCCCGGGATGAGTCGCAAAAGCGGAG | ΔBAB2_1087 |

| GBRORFA0014 DN-R | AAACTGCAGGGTTGCCGGCGCCTCTG | |

| GBRORFA0014 UP-F | GGCCGCCGTGCTGGCGTTTTG | |

| GBRORFA0014 UP-R | TCCCCCGGGCGTGTTCCAGCCTGCGTCAT | |

| GBRORFA0062 DN-F | TCCCCCGGGTAGGCTTATCCAGGCTGTA | ΔBAB2_1136 |

| GBRORFA0062 DN-R | AAACTGCAGGCCTATGGTCTCTTCCCGG | |

| GBRORFA0062 UP-F | CCGCTTCTCACATCCATTTTC | |

| GBRORFA0062 UP-R | TCCCCCGGGCGATGCTGTTATCTTCGAT | |

| GroEL-P-F | AGCATGCCGTTCGGGCGATGGAAACAGGCGTG | Promoter PGroEL |

| GroEL-P-R | ACATATGGTATAACCCTTGGTGTTATAGACG | |

| dTomato-F | ACATATGGTGAGCAAGGGCGAGGAGGTC | pGroEL/dsRed |

| dTomato-R | ACCCGGGATGCATTACTTGTACAGCTCGTCCATGCCGTAC | |

| A0598-Flag-F | ACATATGAGAGCAACCACGCTTAC | pGroEL/CydX |

| A0598 -PstI | ACTGCAGTCAGTGGTGCTTGTTGCCTTC | |

| CydB-F-NdeI | ACATATGATACTCAGCGATTTGTTGGACTATC | pGroEL/CydB |

| CydB-R-PstI | ACTGCAGTCAGTAAGCGTGGTTGCTCTCATCCTC | |

| CydB-F-NdeI | ACATATGATACTCAGCGATTTGTTGGACTATC | pGroEL/CydBX |

| A0598 -PstI | ACTGCAGTCAGTGGTGCTTGTTGCCTTC | |

| A0598-Flag-F | ACATATGAGAGCAACCACGCTTAC | pCydX/FT |

| A0598-Flag-R | AGTCGACGTGGTGCTTGTTGCCTTC | |

| A0598 -XbaI | ATCTAGAAGAGCAACCACGCTTACTGATTG | pFT/CydX |

| A0598 -PstI | ACTGCAGTCAGTGGTGCTTGTTGCCTTC | |

| Promoter-F | TTAGGGTACCGTTAACGCTCCCCGAAAACGGC | Promoter PBMEII0192 |

| Promoter-R | AGTCGACATATGTGATTTCCGGC | |

| Flag-F | ACATATGAGCCTAGTCGACTACAAAGACCATGAC | pBBR1Flag |

| Flag-R | AGAGCTCCTGCAGTTACTATTTATCGTCGTCATC | |

| A0598-Flag-F | ACATATGAGAGCAACCACGCTTAC | pCydX/Flag |

| A0598 -PstI | ACTGCAGTCAGTGGTGCTTGTTGCCTTC |

Engineered restriction sites underlined.

References

- Afseth G., Mo Y. Y., Mallavia L. P. (1995). Characterization of the 23S and 5S rRNA genes of Coxiella burnetii and identification of an intervening sequence within the 23S rRNA gene. J. Bacteriol. 177, 2946–2949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alix E., Blanc-Potard A. B. (2009). Hydrophobic peptides: novel regulators within bacterial membrane. Mol. Microbiol. 72, 5–11 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06626.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alix E., Blanc-Potard A. B. (2008). Peptide-assisted degradation of the Salmonella MgtC virulence factor. EMBO J. 27, 546–557 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutting S., Anderson M., Lysenko E., Page A., Tomoyasu T., Tatematsu K., Tatsuta T., Kroos L., Ogura T. (1997). SpoVM, a small protein essential to development in Bacillus subtilis, interacts with the ATP-dependent protease FtsH. J. Bacteriol. 179, 5534–5542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datta N., Kontomichalou P. (1965). Penicillinase synthesis controlled by infectious R factors in Enterobacteriaceae. Nature 208, 239–241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng W., Chen L., Peng W. T., Liang X., Sekiguchi S., Gordon M. P., Comai L., Nester E. W. (1999). VirE1 is a specific molecular chaperone for the exported single-stranded-DNA-binding protein VirE2 in Agrobacterium. Mol. Microbiol. 31, 1795–1807 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01316.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards S. E., Loder C. S., Wu G., Corker H., Bainbridge B. W., Hill S., Poole R. K. (2000). Mutation of cytochrome bd quinol oxidase results in reduced stationary phase survival, iron deprivation, metal toxicity and oxidative stress in Azotobacter vinelandii. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 185, 71–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eguchi Y., Ishii E., Hata K., Utsumi R. (2011). Regulation of acid resistance by connectors of two-component signal transduction systems in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 193, 1222–1228 10.1128/JB.01124-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elzer P. H., Phillips R. W., Kovach M. E., Peterson K. M., Roop R. M., 2nd. (1994). Characterization and genetic complementation of a Brucella abortus high-temperature-requirement A (htrA) deletion mutant. Infect. Immun. 62, 4135–4139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endley S., McMurray D., Ficht T. A. (2001). Interruption of the cydB locus in Brucella abortus attenuates intracellular survival and virulence in the mouse model of infection. J. Bacteriol. 183, 2454–2462 10.1128/JB.183.8.2454-2462.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eskra L., Canavessi A., Carey M., Splitter G. (2001). Brucella abortus genes identified following constitutive growth and macrophage infection. Infect. Immun. 69, 7736–7742 10.1128/IAI.69.12.7736-7742.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falkow S. (1988). Molecular Koch's postulates applied to microbial pathogenicity. Rev. Infect. Dis. 10(Suppl. 2), S274–S276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerdes K., Bech F. W., Jorgensen S. T., Lobner-Olesen A., Rasmussen P. B., Atlung T., Boe L., Karlstrom O., Molin S., von Meyenburg K. (1986). Mechanism of postsegregational killing by the hok gene product of the parB system of plasmid R1 and its homology with the relF gene product of the E. coli relB operon. EMBO J. 5, 2023–2029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gor D., Mayfield J. E. (1992). Cloning and nucleotide sequence of the Brucella abortus groE operon. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1130, 120–122 10.1016/0167-4781(92)90476-G [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green G. N., Kranz R. G., Lorence R. M., Gennis R. B. (1984). Identification of subunit I as the cytochrome b558 component of the cytochrome d terminal oxidase complex of Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 259, 7994–7997 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groicher K. H., Firek B. A., Fujimoto D. F., Bayles K. W. (2000). The Staphylococcus aureus lrgAB operon modulates murein hydrolase activity and penicillin tolerance. J. Bacteriol. 182, 1794–1801 10.1128/JB.182.7.1794-1801.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- den Hartigh A. B., Sun Y. H., Sondervan D., Heuvelmans N., Reinders M. O., Ficht T. A., Tsolis R. M. (2004). Differential requirements for VirB1 and VirB2 during Brucella abortus infection. Infect. Immun. 72, 5143–5149 10.1128/IAI.72.9.5143-5149.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemm M. R., Paul B. J., Miranda-Rios J., Zhang A., Soltanzad N., Storz G. (2010). Small stress response proteins in Escherichia coli: proteins missed by classical proteomic studies. J. Bacteriol. 192, 46–58 10.1128/JB.00872-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong P. C., Tsolis R. M., Ficht T. A. (2000). Identification of genes required for chronic persistence of Brucella abortus in mice. Infect. Immun. 68, 4102–4107 10.1128/IAI.68.7.4102-4107.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez de Bagues M. P., Loisel-Meyer S., Liautard J. P., Jubier-Maurin V. (2007). Different roles of the two high-oxygen-affinity terminal oxidases of Brucella suis: Cytochrome c oxidase, but not ubiquinol oxidase, is required for persistence in mice. Infect. Immun. 75, 531–535 10.1128/IAI.01185-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jong M. F., Sun Y. H., den Hartigh A. B., van Dijl J. M., Tsolis R. M. (2008). Identification of VceA and VceC, two members of the VjbR regulon that are translocated into macrophages by the Brucella type IV secretion system. Mol. Microbiol. 70, 1378–1396 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06487.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph P., Turtaut F., Ouahrani-Bettache S., Montero J. L., Nishimori I., Minakuchi T., Vullo D., Scozzafava A., Kohler S., Winum J. Y., Supuran C. T. (2010). Cloning, characterization, and inhibition studies of a beta-carbonic anhydrase from Brucella suis. J. Med. Chem. 53, 2277–2285 10.1021/jm901855h [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovach M. E., Elzer P. H., Hill D. S., Robertson G. T., Farris M. A., Roop R. M., 2nd, Peterson K. M. (1995). Four new derivatives of the broad-host-range cloning vector pBBR1MCS, carrying different antibiotic-resistance cassettes. Gene 166, 175–176 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00584-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulakov Y. K., Guigue-Talet P. G., Ramuz M. R., O'Callaghan D. (1997). Response of Brucella suis 1330 and B. canis RM6/66 to growth at acid pH and induction of an adaptive acid tolerance response. Res. Microbiol. 148, 145–151 10.1016/S0923-2508(97)87645-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamontagne J., Beland M., Forest A., Cote-Martin A., Nassif N., Tomaki F., Moriyon I., Moreno E., Paramithiotis E. (2010). Proteomics-based confirmation of protein expression and correction of annotation errors in the Brucella abortus genome. BMC Genomics 11, 300 10.1186/1471-2164-11-300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenn T., Leake M. C., Mullineaux C. W. (2008). Clustering and dynamics of cytochrome bd-I complexes in the Escherichia coli plasma membrane in vivo. Mol. Microbiol. 70, 1397–1407 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06486.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin J., Adams L. G., Ficht T. A. (1992). Characterization of the heat shock response in Brucella abortus and isolation of the genes encoding the GroE heat shock proteins. Infect. Immun. 60, 2425–2431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin J., Ficht T. A. (1995). Protein synthesis in Brucella abortus induced during macrophage infection. Infect. Immun. 63, 1409–1414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loisel-Meyer S., Jimenez de Bagues M. P., Kohler S., Liautard J. P., Jubier-Maurin V. (2005). Differential use of the two high-oxygen-affinity terminal oxidases of Brucella suis for in vitro and intramacrophagic multiplication. Infect. Immun. 73, 7768–7771 10.1128/IAI.73.11.7768-7771.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller M. J., Gennis R. B. (1983). The purification and characterization of the cytochrome d terminal oxidase complex of the Escherichia coli aerobic respiratory chain. J. Biol. Chem. 258, 9159–9165 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller M. J., Hermodson M., Gennis R. B. (1988). The active form of the cytochrome d terminal oxidase complex of Escherichia coli is a heterodimer containing one copy of each of the two subunits. J. Biol. Chem. 263, 5235–5240 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller M. M., Webster R. E. (1997). Characterization of the tol-pal and cyd region of Escherichia coli K-12: transcript analysis and identification of two new proteins encoded by the cyd operon. J. Bacteriol. 179, 2077–2080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pittman M. S., Robinson H. C., Poole R. K. (2005). A bacterial glutathione transporter (Escherichia coli CydDC) exports reductant to the periplasm. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 32254–32261 10.1074/jbc.M503075200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raffatellu M., Sun Y. H., Wilson R. P., Tran Q. T., Chessa D., Andrews-Polymenis H. L., Lawhon S. D., Figueiredo J. F., Tsolis R. M., Adams L. G., Baumler A. J. (2005). Host restriction of Salmonella enterica serotype Typhi is not caused by functional alteration of SipA, SopB, or SopD. Infect. Immun. 73, 7817–7826 10.1128/IAI.73.12.7817-7826.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ralph D., McClelland M. (1993). Intervening sequence with conserved open reading frame in eubacterial 23S rRNA genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 90, 6864–6868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaner N. C., Campbell R. E., Steinbach P. A., Giepmans B. N., Palmer A. E., Tsien R. Y. (2004). Improved monomeric red, orange and yellow fluorescent proteins derived from Discosoma sp. red fluorescent protein. Nat. Biotechnol. 22, 1567–1572 10.1038/nbt1037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y. H., Rolan H. G., den Hartigh A. B., Sondervan D., Tsolis R. M. (2005). Brucella abortus virB12 is expressed during infection but is not an essential component of the type IV secretion system. Infect. Immun. 73, 6048–6054 10.1128/IAI.73.9.6048-6054.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y. H., Rolan H. G., Tsolis R. M. (2007). Injection of flagellin into the host cell cytosol by Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 33897–33901 10.1074/jbc.C700181200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uzzau S., Figueroa-Bossi N., Rubino S., Bossi L. (2001). Epitope tagging of chromosomal genes in Salmonella. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 15264–15269 10.1073/pnas.261348198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wall D., Delaney J. M., Fayet O., Lipinska B., Yamamoto T., Georgopoulos C. (1992). arc-dependent thermal regulation and extragenic suppression of the Escherichia coli cytochrome d operon. J. Bacteriol. 174, 6554–6562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Q., Pei J., Turse C., Ficht T. A. (2006). Mariner mutagenesis of Brucella melitensis reveals genes with previously uncharacterized roles in virulence and survival. BMC Microbiol. 6, 102 10.1186/1471-2180-6-102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J., Barquera B., Gennis R. B. (2004). Gene fusions with beta-lactamase show that subunit I of the cytochrome bd quinol oxidase from E. coli has nine transmembrane helices with the O2 reactive site near the periplasmic surface. FEBS Lett. 561, 58–62 10.1016/S0014-5793(04)00125-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]