Abstract

In humans, fetal ethanol exposure is highly predictive of adolescent ethanol use and abuse. Prior work in our labs indicated that fetal ethanol exposure results in stimulus-induced chemosensory plasticity in the taste and olfactory systems of adolescent rats. In particular, we found that increased ethanol acceptability could be attributed, in part, to an attenuated aversion to ethanol’s aversive odor and quinine-like bitter taste quality. Here, we asked whether fetal ethanol exposure also alters the oral trigeminal response of adolescent rats to ethanol. We focused on two excitatory ligand-gated ion channels, TrpV1 and TrpA1, which are expressed in oral trigeminal neurons and mediate the aversive orosensory response to many chemical irritants. To target TrpV1, we used capsaicin, and to target TrpA1, we used allyl isothiocyanate (or mustard oil). We assessed the aversive oral effects of ethanol, together with capsaicin and mustard oil, by measuring short-term licking responses to a range of concentrations of each chemical. Experimental rats were exposed in utero by administering ethanol to dams through a liquid diet. Control rats had ad libitum access to an iso-caloric iso-nutritive liquid diet. We found that fetal ethanol exposure attenuated the oral aversiveness of ethanol and capsaicin, but not mustard oil, in adolescent rats. Moreover, the increased acceptability of ethanol was directly related to the reduced aversiveness of the TrpV1-mediated orosensory input. We propose that fetal ethanol exposure increases ethanol avidity not only by making ethanol smell and taste better, but also by attenuating ethanol’s capsaicin-like burning sensations.

Keywords: ethanol, fetal exposure, rats, oral irritation, plasticity, TrpV1, TrpA1

Introduction

Fetal ethanol exposure is highly predictive of adolescent ethanol use and abuse in humans.1 Animal studies indicate that this effect is mediated in part by an experience-induced change in chemosensory responsiveness to ethanol. For instance, we reported that fetal ethanol exposure increases the acceptability of ethanol to adolescent rats.2,3 We were able to attribute 51.3% of the increase in ethanol acceptability to an exposure-induced reduction in its aversive taste and odor. Here, we asked whether fetal ethanol exposure also reduces the aversive burning sensations that ethanol produces in the oral cavity.4 Ethanol is thought to produce these sensations by diffusing into the oral epithelium and stimulating the distal dendritic portions (free nerve endings) of trigeminal sensory neurons in the lingual nerve.5–7 It activates the free nerve endings by interacting with the transient receptor-potential vanilloid receptor-1 (TrpV1)8,9 but not TrpA1.10

There are several ways that the developing trigeminal system of embryonic rats could encounter maternally ingested ethanol. Because maternally ingested ethanol contaminates the fetal blood,11 it would effectively bathe the developing trigeminal system. In addition, because ingested ethanol contaminates the amniotic fluid,12 rat embryos would encounter ethanol as they swallowed amniotic fluid.13 This direct orosensory exposure to ethanol would be most significant during the final four days of pregnancy, when the developing trigeminal sensory fibers have fully penetrated the lingual epithelium.14

We asked whether fetal ethanol exposure enhances ethanol acceptability by attenuating the aversive trigeminal oral stimulation that it produces. To examine the specific contribution of trigeminal stimulation, independent of ethanol, we tested selective ligands of the TrpV1 (capsaicin)8 or TrpA1 (allyl-isothiocyanate or mustard oil)15,16 channels. Although there are reports of mustard oil activating TrpV1,17 – 19 the relevance of these observations to ingestive behavior is unclear given that genetic ablation of TrpV1 has no impact on the oral acceptability of mustard oil during one-hour intake tests in mice.18

Although some trigeminal C-fibers express TrpV1 alone, most co-express TrpV1 and TrpA1.20,21 In support of this observation, human and rat studies have demonstrated that desensitizing the behavioral or physiological responses to capsaicin generalizes to mustard oil and vice versa.22,23 Furthermore, many mouse trigeminal neurons respond to both capsaicin and mustard oil.24 On the basis of this prior body of work, we hypothesized that fetal ethanol exposure should increase the orosensory acceptability of capsaicin and mustard oil (surrogates for oral irritation), and that these effects should contribute to enhanced ethanol acceptance.

Methods

Experimental treatment of pregnant dams

On gestational day 5 (G5), female Long-Evans rats (Harlan–Sprague Dawley, Indianapolis, IN, USA) were divided into blocks of two weight-matched dams, and randomly assigned to either the ethanol or control group. Following established protocols, ethanol dams were administered an ad libitum liquid diet (L10251; Research Diets, New Brunswick, NJ, USA) that provided them with 35% of their daily calories coming from ethanol during G11 – G20.2,3,18 Dams were weaned onto the diet from G6 to G10. Peak blood alcohol levels reached approximately 150 mg/dL.2,25 This approach yields a relatively consistent level of exposure, and should simulate moderate ethanol intake during the development of the trigeminal sensory system; the trigeminal fibers actually penetrate the lingual epithelium on G18.14 Dams in the control group were provided ad libitum access to an iso-nutritive liquid diet supplemented with maltose/dextrin, which provided equivalent caloric content as the ethanol diet (L10252; Research Diets). In this study, we limited our control treatment to ad libitum fed dams, as previous work has shown no difference in the olfactory, orosensory or ethanol intake responses of progeny derived from pair-fed and free-choice access animals (e.g. refs.2,3). Rat pups were weaned on postnatal day (P) 21 and transported on P24 from SUNY Upstate to Barnard College for later behavioral testing. Protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees at both institutions.

Test animals

We ran a total of 24 rats from the ethanol-exposed group and 24 from the control group through short-term lick tests. In all cases, we used balanced sex ratios. All rats were initially subjected to lick testing as adolescents, and a subset of rats (n = 12/maternal diet treatment) were tested a second time as adults. Adolescent rats were tested because this is the earliest age readily amenable to lickometer testing and because fetal ethanol exposure has consistently been shown to enhance ethanol intake in adolescent rats.26,27 The rats were retested as adults to determine whether any effect of maternal diet treatment persisted into adulthood.

Chemical stimuli

We examined licking responses to a range of concentrations of ethanol (0.5, 3, 6, 9 and 18% v/v), capsaicin (0.1, 0.3, 1, 3 and 10 µmol/L) and mustard oil (0.1, 0.3, 1, 3 and 10 mmol/L). Although the ethanol and mustard oil could be dissolved in deionized water, the capsaicin could not. Thus, we dissolved the capsaicin in pure dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO), and then diluted it with deionized water to create a stock solution of 10 µmol/L capsaicin in 0.1% DMSO. This stock solution was subsequently diluted with a 0.1% DMSO solution to the concentrations indicated above. The ‘water’ stimulus in the capsaicin tests also contained 0.1% DMSO. All chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO, USA).

Assessment of orosensory response

To assess orosensory responsiveness, we measured lick responses during repeated 10-s trials.3,28 We used a computer-controlled gustometer that presented individual chemical stimuli according to a predetermined schedule, and recorded licking responses (Davis MS160; DiLog Instruments, Tallahassee, FL, USA). To motivate rats to lick from the sipper tube during the training and test sessions, they were water-deprived for 22.5 h before training. After each session, rats were returned to their home cage, given one hour of ad libitum access to water, and water-deprived for another 22.5 h (assuming testing or training occurred on the following day).

Each adolescent rat was subjected to three days of training in the gustometer, starting on P27; the adult rats were subjected to an additional three days of training, starting on P86. Each training session lasted 30 min. On training day 1, the rat was permitted to drink water freely from a single stationary spout for 30 min. On training days 2 and 3, the rats received more limited access to the sipper tubes – that is, the shutter was opened, and a trial lasting 10 s was initiated once the rat took its first lick. At the end of a trial, the shutter was closed for 7.5 s (during which time a different sipper tube containing water was positioned in the center of the slot) and then reopened, enabling the rat to initiate another trial of the same duration. In this manner, the rat could initiate up to 102 trials during a 30-min test session.

Once training was complete, the rats were subjected to three consecutive days of testing, starting on P31–32 for adolescents and P90 for adults. During each 30-min test session, a rat was offered six sipper tubes, each separately. One sipper tube contained water and the other sipper tubes contained different concentrations of a chemical stimulus (e.g. ethanol; see above for details). For each chemical stimulus, the order of presentation of the water and five stimulus concentrations was randomized without replacement in blocks so that every concentration and water was presented once before the initiation of a second block. For all rats, ethanol was tested on day 1, capsaicin on day 2 and mustard oil on day 3. For testing, we used the same water-deprivation and testing procedures as described above for training days 2 and 3.

Data analysis

We converted all licking responses to a lick ratio (i.e. the mean number of licks/trial for each taste stimulus concentration divided by the mean number of licks/trial for water alone). Use of this ratio enabled us to control for individual differences in local lick rate and motivational state.

For each chemical and age group, we examined the effect of maternal diet treatment (a between factor) and concentration (a within factor) on the lick ratio, using a mixed-model analysis of variance (ANOVA; α level = 0.05). We pooled data across gender because two-way ANOVAs revealed no main effect of gender or interaction of gender × concentration on lick ratios for each of the chemical stimuli, irrespective of maternal diet treatment (all cases, P > 0.05). To examine significant main effects or interactions between maternal diet treatment and concentration, we ran unpaired t-tests at selected concentrations across maternal diet treatments.

Results

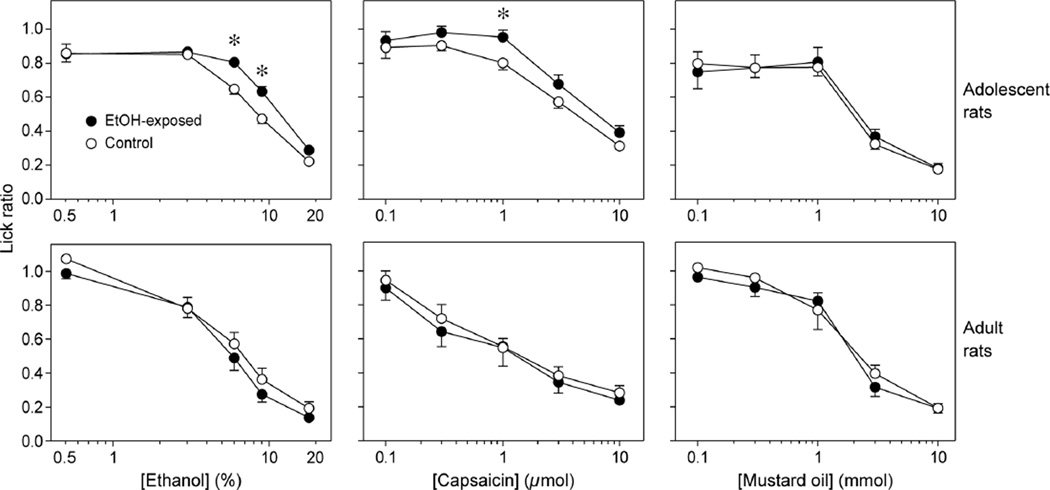

The adolescent rats exhibited robust effects of maternal diet on lick ratios (Figure 1, top row of panels). In keeping with our prior ethanol observations,3 the main effects of maternal diet (F1,184 = 14.5; P < 0.0002) and concentration (F4,184 = 131.6; P < 0.0001), and the interaction of maternal diet × concentration (F4,184 = 3.1; P < 0.02) were all significant. The interaction reflected a significantly higher lick ratio at the 6% and 9% concentrations of ethanol for ethanol-exposed rats (both t-values > 3.9, df = 46, P < 0.0003). Likewise, for capsaicin, the main effects of maternal diet (F1,184 = 5.9; P < 0.02) and concentration (F4,184 = 82.3; P < 0.0001) were significant, but the interaction of maternal diet × concentration (F4,184 = 0.5; P > 0.7) was not. The lick ratio was significantly higher at the 1 µmol/L concentration of capsaicin for ethanol-exposed rats (t = 2.6, df = 46, P < 0.012). In contrast, for mustard oil, the main effect of concentration (F4,184 = 77.3; P < 0.0001) was significant, but the main effect of maternal diet (F1,184 = 0.1; P > 0.7) and the interaction of maternal diet × concentration (F4,184 = 0.6; P > 0.6) were not significant.

Figure 1.

Oral acceptability of a range of concentrations of ethanol, capsaicin and mustard oil to ethanol-exposed and control rats. We show results from both adolescent (top row of panels) and adult (bottom row of panels) rats. We represent oral acceptability as lick ratios (mean ± SEM). A lick ratio of 1.0 occurs when licks to the taste stimulus equaled licks to water. Lick ratios less than 1.0 indicate that the chemical stimulus inhibited licking. We compared the lick ratios across maternal diet treatment at selected concentrations with unpaired t-tests; we indicate significant differences with an asterisk (see text for details)

The effects of maternal diet on the orosensory acceptability of ethanol and capsaicin did not persist into adulthood (Figure 1, bottom row of panels). For the adult rats, there was a significant main effect of concentration on the lick ratios for ethanol, capsaicin and mustard oil (in all cases, P < 0.0001), but there was no significant main effect of maternal diet (in all cases, P > 0.2) or interaction of maternal diet × concentration (in all cases, P > 0.4). Thus, although ethanol, capsaicin and mustard oil all elicited concentration-dependent decreases in lick ratio in the adult rats, the fetal exposure effects noted in adolescence had ameliorated by adulthood.

Using a previously established approach,2,3 we asked whether the reduced aversion to oral irritation (represented by capsaicin) contributed directly to the reduced aversion to ethanol in adolescent rats. To this end, we focused on the lick values that fell along the dynamic range of the prenatal effect (i.e. 3% and 6% ethanol, and 1, 3 and 10 µmol/L capsaicin). Of note, 3% and 6% ethanol captured the range of ethanol concentrations that are most preferred by adolescent rats with fetal ethanol exposure.29 Using these values, we constructed two univariate composite stimulus response indexes that represented each rat’s licking response to ethanol and capsaicin, respectively. For each chemical stimulus, we performed a multivariate regression analysis with the stimulus-induced lick response measures as the dependent variables and maternal treatment as the independent variable. This approach provided estimates of the coefficients for each concentration of chemical stimulus in the separate regression analyses. The composite index value for each animal was the linear summation of the constant from the appropriate regression analysis and the respective lick ratio value at each of the relevant concentrations (i.e. 3% and 6% for ethanol, and 1, 3 and 10 µmol/L for capsaicin) of stimulus multiplied by the appropriate estimated coefficient.

To estimate the ability of the capsaicin response index to predict changes in the ethanol response index, we performed an analysis of co-variance. In this analysis, the slope, β, was the coefficient of X in the regression of Y (the ethanol responses of the two maternal treatment groups) on X (the capsaicin behavioral responses of the same animals). The results demonstrated a significant slope (F1,46 = 4.98; P = 0.03) in which the estimate of β was 0.459 (Figure 2a). Thus, a linear predictive relationship exists between the effect of fetal ethanol exposure on the responsiveness to oral irritation (as assessed with capsaicin) and ethanol.

Figure 2.

Demonstration that attenuated licking response of adolescent rats to 3% and 6% ethanol can be attributed to the increased acceptability of the capsaicin-like oral irritation that it produces. (a) Estimated slope of the predictive relationship between the rats’ orosensory response index to capsaicin (a surrogate for ethanol’s oral irritation) and the same rats’ response index to ethanol. The slope is shown relative to the mean (±2-dimensional standard errors) location of each maternal treatment group. (b) Full height of the column represents the net difference in the ethanol response index between ethanol-exposed and control animals. The lower section of the column (solid black) represents the amount of the difference attributable to TrpV1-mediated oral irritation by ethanol. We show mean ± SEM

To determine whether the effect of fetal ethanol exposure on ethanol acceptance was attributable (at least in part) to a change in responsiveness to the TrpV1-mediated ethanol effects, we could not rely on the predictive relationship illustrated in Figure 2a. Rather, we had to incorporate the difference in the capsaicin orosensory response index between the ethanol-exposed and control rats (i.e. strength of the maternal treatment effect). To this end, we multiplied the slope of the predictive relationship in Figure 2a times the difference in the capsaicin orosensory response index between ethanol-exposed and control rats. This revealed that a significant proportion of the net differential response to ethanol was attributable to an effect of fetal ethanol exposure on the TrpV1-mediated ethanol effects (two-tailed: t46 = 3.52, P = 0.001).

The full height of the column in Figure 2b indicates the total estimated effect of fetal ethanol exposure on the ethanol response index of control versus ethanol-exposed rats (i.e. mean ± SEM: 0.286 ± 0.07). This is the net total effect of maternal ethanol exposure on ethanol orosensory acceptability. The filled portion of the column shows the product value from the analysis described above. To calculate the filled portion of the bar, we multiplied the difference in capsaicin response indices between control (μX1 = 0.557) and ethanol-exposed (μX2 = 0.424) rats times the slope (β = 0.459) of the predictive relationship, yielding 0.06. This value represents the partial effect of prenatal exposure on the net ethanol acceptability that is attributable to a decreased aversion to the TrpV1-mediated response. The ratio of these two estimates indicates that ~21% of the total effect of fetal ethanol exposure on ethanol acceptability was mediated by a reduced aversion to the TrpV1-mediated component of the sensory response.

Discussion

Oral chemosensation is known to play a central role in controlling ethanol intake.30 Accordingly, we hypothesized that the effects of fetal ethanol exposure on ethanol intake are mediated, in part, by changes in the quality components of ethanol. In a prior study,3 we demonstrated that a reduced aversion to the bitter taste and odor qualities of ethanol could account for 51% of the effect of fetal ethanol exposure on oral acceptability of ethanol (29% bitter taste and 22% olfaction) in adolescent rats. Here, we report that a reduced aversion to TrpV1-mediated input from ethanol accounted for an additional 21% of the fetal exposure effect on ethanol acceptability. These findings indicate that fetal ethanol exposure not only makes ethanol smell and taste better, but it also attenuates its capsaicin-like burning sensations. The fact that we cannot explain 28% of the fetal exposure effect on ethanol acceptability indicates that we have not yet captured the totality of the component sensory qualities of ethanol.

We predicted that fetal ethanol exposure would increase the orosensory acceptability of ethanol, capsaicin and mustard oil. We based this prediction on the observations (a) that most chemically responsive C-fibers in the oral cavity co-express TrpV1 and TrpA120,21 and respond to both capsaicin and mustard oil;24 and (b) that behavioral and physiological responses to capsaicin generalize to mustard oil and vice versa.22,23 However, our results contradicted this prediction, and instead indicate the effect of fetal ethanol exposure was not mediated by generalized desensitization of the C-fibers expressing TrpV1 and TrpA1. We propose, instead, that the presence of ethanol in the blood and/or oral cavity during embryonic development caused a selective down-regulation in expression of the TrpV1 receptors in the oral trigeminal C-fibers through adolescence. In support of this proposition, there is evidence that TrpV1 expression in oral trigeminal fibers is subject to modulation.31 – 33 Given that the exposure-induced change in capsaicin responsiveness failed to persist into adulthood, it follows that the effect on fetal ethanol exposure on TrpV1 expression is transient.

Irrespective of the underlying mechanisms, our findings provide further evidence for epigenetic chemosensory processes by which maternal patterns of drug use can be transferred to offspring. It is important to note that such findings have broad implications for the relationship between maternal drug use, early development and postnatal vulnerability for developing patterns of use and abuse.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by NIH-NIAAA grants AA014871 and AA017823.

Footnotes

Author contributions: JIG and SLY designed the study, analyzed and interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript. LY conducted the feeding paradigm and made editorial comments on the manuscript. YMS ran the behavioral experiments and contributed to the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baer JS, Sampson PD, Barr HM, Connor PD, Streissguth AP. A 21-year longitudinal analysis of the effects of prenatal alcohol exposure on young adult drinking. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:377–385. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.4.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Youngentob SL, Kent PF, Sheehe PR, Molina JC, Spear NE, Youngentob LM. Experience-induced fetal plasticity: the effect of gestational ethanol exposure on the behavioral and neurophysiologic olfactory response to ethanol odor in early postnatal and adult rats. Behav Neuorsci. 2007;121:1293–1305. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.121.6.1293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Youngentob SL, Glendinning JI. Fetal ethanol exposure increases ethanol intake by making it smell and taste better. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:5359–5364. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809804106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Green BG. The sensitivity of the tongue to ethanol. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1987;510:315–317. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hellekant G. The effect of ethyl alcohol on non-gustatory receptors of the tongue of the cat. Acta Physiol Scand. 1965;65:243–250. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1965.tb04267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simon SA, Sostman AL. Electrophysiological responses to nonelectrolytes in lingual nerve of rat and in lingual epithelia of dog. Arch Oral Biol. 1991;36:805–813. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(91)90030-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Danilova V, Hellekant G. Oral sensation of ethanol in a primate model III: responses in the lingual branch of the trigeminal nerve of Macaca mulatta. Alcohol. 2002;26:3–16. doi: 10.1016/s0741-8329(01)00178-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Trevisani M, Smart D, Gunthorpe MJ, Tognetto M, Barbieri M, Campi B, Amadesi S, Gray J, Jerman JC, Brough SJ, Owen D, Smith GD, Randall AD, Harrison S, Bianchi A, Davis JB, Geppetti P. Ethanol elicits and potentiates nociceptor responses via the vanilloid receptor-1. Nature. 2002;5:546–551. doi: 10.1038/nn0602-852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blednov YA, Harris RA. Deletion of vanilloid receptor (TRPV1) in mice alters behavioral effects of ethanol. Neuropharmacol. 2009;56:814–820. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2009.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bang S, Kim KY, Yoo S, Kim YG, Hwang SW. Transient receptor potential A1 mediates acetaldehyde-evoked pain sensation. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;26:2516–2523. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05882.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Szeto HH. Maternal-fetal pharmacokinetics and fetal dose response relationships. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1989;562:42–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1989.tb21006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abel EL. Fetal Alcohol Syndrome and Fetal Alcohol Effects. New York: Plenum Press; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Molina JC, Chotro MG. Association between chemosensory stimuli and cesarean delivery in rat fetuses: neonatal presentation of similar stimuli increases motor activity. Behav Neural Biol. 1991;55:42–60. doi: 10.1016/0163-1047(91)80126-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dillon TE, Saldanha J, Giger R, Verhaagen J, Rochlin MW. Sema3A regulates the timing of target contact by cranial sensory axons. J Comp Neurol. 2004;470:13–24. doi: 10.1002/cne.11029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jordt S-E, Bautista DM, Chuang H, McKenny DD, Zygmunt PM, Högestätt ED, Meng ID, Julius D. Mustard oils and cannabinoids excite sensory nerve fibres through the TRP channel ANKTM1. Nature. 2004;427:260–265. doi: 10.1038/nature02282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bautista DM, Jordt S-E, Nikai T, Tsuruda PR, Read AJ, Poblete J, Yamoah EN, Basbaum AI, Julius D. TRPA1 mediates the inflammatory actions of environmental irritants and proalgesic agents. Cell. 2006;124:1269–1282. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ohta T, Imagawa T, Ito S. Novel agonistic action of mustard oil on recombinant and endogenous porcine transient receptor potential V1 (pTRPV1) channels. Biochem Pharmacol. 2007;73:1646–1656. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2007.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Everaerts W, Gees M, Alpizar YA, Farre R, Leten C, Apetrei A, Dewachter I, van Leuven F, Vennekens R, De Ridder D, Nilius B. The capsaicin receptor TRPV1 is a crucial mediator of the noxious effects of mustard oil. Curr Biol. 2011;21:316–321. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mori N, Kawabata F, Matsumura S, Hosokawa H, Kobayashi S, Inoue K, Fushiki T. Intragastric administration of allyl isothiocyanate increases carbohydrate oxidation via TRPV1 but not TRPA1 in mice. Am J Physiol. 2011;300:R1494–R1505. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00645.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kobayashi K, Fukuoka T, Obata K, Yamanaka H, Dai Y, Tokunaga A, Noguchi K. Distinct expression of TRPM8, TRPA1, and TRPV1 mRNAs in rat primary afferent neurons with A/C-fibers and colocalization with Trk receptors. J Comp Neurol. 2005;493:596–606. doi: 10.1002/cne.20794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bautista DM, Movahed P, Hinman A, Axelsson HE, Sterner O, Högestätt ED, Julius D, Jordt S-E, Zygmunt PM. Pungent products from garlic activate the sensory ion channel TRPA1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:12248–12252. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505356102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Simons CT, Carstens MIEC. Oral irritation by mustard oil: self-desensitization and cross-desensitization with capsaicin. Chem Senses. 2003;28:459–465. doi: 10.1093/chemse/28.6.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Andrade EL, Ferreira J, André E, Calixto JB. Contractile mechanisms coupled to TRPA1 receptor activation in rat urinary bladder. Biochem Pharmacol. 2006;72:104–114. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2006.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Talavera K, Gees M, Karashima Y, Meseguer VM, Vanoirbeek JAJ, Damann N, Everaerts W, Benoit M, Janssens A, Vennekens R, Viana F, Nemery B, Nilius B, Voets T. Nicotine activates the chemosensory cation channel TRPA1. Nature. 2009;12:1293–1300. doi: 10.1038/nn.2379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miller MW. Effects of Alcohol and Opiates. New York: Wiley-Liss; 1992. Development of the Central Nervous System. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spear NE, Molina JC. Fetal or infantile exposure to ethanol promotes ethanol ingestion in adolescence and adulthood. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005;29:909–929. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000171046.78556.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Molina JC, Spear NE, Spear LP, Mennella JA, Lewis MJ. Alcohol and development: beyond fetal alcohol syndrome. Dev Psychobiol. 2007;49:227–242. doi: 10.1002/dev.20224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Glendinning JI, Gresack J, Spector AC. A high-throughput screening procedure for identifying mice with aberrant taste and oromotor function. Chem Senses. 2002;27:461–474. doi: 10.1093/chemse/27.5.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chotro MG, Arias C. Prenatal exposure to ethanol increases ethanol consumption: a conditioned response? Alcohol. 2003;30:19–28. doi: 10.1016/s0741-8329(03)00037-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bachmanov AA, Kiefer SW, Molina JC, Tordoff MG, Duffy VB, Bartoshuk LM, Mennella JA. Chemosensory factors influencing alcohol perception, preferences, and consumption. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2003;27:220–231. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000051021.99641.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Szallasi A, Cortright DN, Blum CA, Eid SR. The vanilloid receptor TRPV1: 10 years from channel cloning to antagonist proof-of-concept. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2007;6:357–372. doi: 10.1038/nrd2280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chung M-K, Lee J, Duraes G, Ro JY. Lipopolysaccharide-induced pulpitis up-regulates TRPV1 in trigeminal ganglia. J Dent Res. 2011;90:1103–1107. doi: 10.1177/0022034511413284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhu W, Oxford GS. Differential gene expression of neonatal and adult DRG neurons correlates with the differential sensitization of TRPV1 responses to nerve growth factor. Neurosci Lett. 2011;500:192–196. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2011.06.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]