Abstract

The Respimat® Soft Mist™ Inhaler (SMI) (Boehringer Ingelheim International GmbH, Ingelheim, Germany) was developed in response to the need for a pocket-sized device that can generate a single-breath, inhalable aerosol from a drug solution using a patient-independent, reproducible, and environmentally friendly energy supply. This paper describes the design and evolution of this innovative device from a laboratory concept model and the challenges that were overcome during its development and scaleup to mass production. A key technical breakthrough was the uniblock, a component combining filters and nozzles and made of silicon and glass, through which drug solution is forced using mechanical power. This allows two converging jets of solution to collide at a controlled angle, generating a fine aerosol of inhalable droplets. The mechanical energy comes from a spring which is tensioned by twisting the base of the device before use. Additional features of the Respimat® SMI include a dose indicator and a lockout mechanism to avoid the problems of tailing-off of dose size seen with pressurized metered dose inhalers. The Respimat® SMI aerosol cloud has a unique range of technical properties. The high fine particle fraction allied with the low velocity and long generation time of the aerosol translate into a higher fraction of the emitted dose being deposited in the lungs compared with aerosols from pressurized metered dose inhalers and dry powder inhalers. These advantages are realized in clinical trials in adults and children with obstructive lung diseases, which have shown that the efficacy and safety of a pressurized metered dose inhaler formulation of a combination bronchodilator can be matched by a Respimat® SMI formulation containing only one half or one quarter of the dose delivered by a pressurized metered dose inhaler. Patient satisfaction with the Respimat® SMI is high, and the long duration of the spray is of potential benefit to patients who have difficulty in coordinating inhalation with drug release.

Keywords: aerosol, deposition, drug delivery, inhaler device, Respimat®

Introduction

Inhalation of drugs provides direct delivery to treat local pulmonary diseases, and offers a noninvasive route for administering drugs systemically. For treatment of asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease by inhalation, this allows a lower dose to be administered compared with the oral route, and side effects are consequently minimized. Additionally, inhaled drug delivery results in an onset of action that is more rapid than is possible following oral administration. To ensure that the drug reaches the lungs efficiently, it must be administered as either a solid or liquid aerosol, with a size range of 1 to 5 μm.1 To be therapeutically useful, a portable aerosol generating device, easily and correctly operated by the patient, is preferred.

Until the 1990s, the most commonly used and commercialized device for inhaled drug administration was the pressurized metered dose inhaler. Although it was considered to be the gold standard, some shortcomings were readily evident.2–5 For example, the velocity of the aerosol particles generated by the pressurized metered dose inhaler is in the range of 25 km/hour which, combined with their initial droplet size, confers a Stokes number that causes a large percentage of the metered dose to deposit in the oropharyngeal region, and fail to reach the lungs. Clinically, this manifests as an unpleasant taste, and the irritation is made worse by any unevaporated propellant that deposits on the back of the throat. In addition, some patients, particularly children and the elderly, are unable to coordinate release of the aerosol with their inhalation maneuver, which is crucial for achieving optimal deposition of drug in the lungs. One approach taken to circumvent these deficiencies was to affix a spacer device to the pressurized metered dose inhaler, but this transforms the inhaler into a more bulky device that is more difficult to transport and use discreetly.

At the end of the last century, the pharmaceutical industry was faced with the task of phasing out chlorofluorocarbon propellants, which were vital auxiliary ingredients for the formulation of a drug in a pressurized metered dose inhaler. Chlorofluorocarbons provided the energy for generating inhalable drug particles, but they were also associated with depletion of atmospheric ozone.6 The most obvious approach was to replace the chlorofluorocarbon propellants with hydrofluoroalkanes, so that the patient can continue to use a pressurized metered dose inhaler without having to learn the handling of a new device.

Alternatives to pressurized metered dose inhalers

To develop an alternative device that required neither chlorofluorocarbons nor hydrofluoroalkanes, a different energy source had to be identified to replace the propellant. One approach known at this time was the dry powder inhaler, which uses the pressure-volume work generated by the inspiration of the patient to obtain inhalable drug particles. Because dry powder inhalers are inherently breath-actuated they require no coordination between dose release and inhalation. Several dry powder inhalers had already been introduced before the chlorofluorocarbon phaseout, including multidose (eg, Diskus® [GlaxoSmithKline, Middlesex, UK], Turbuhaler® [Astra Zeneca, Södertälje, Sweden]) and single-dose designs (eg, the HandiHaler® [Boehringer Ingelheim, Ingelheim, Germany]). In most cases, micronized drug particles (size range 1–5 μm) are mixed with a larger particle size carrier, such as lactose. The dry powder inhalers are designed in such a way that the drug/carrier mixture is partly deagglomerated into inhalable drug particles by the inspiratory airflow of the patient. The extent of device emptying and deagglomeration, which determines the fine particle dose of drug emitted from the dry powder inhaler, depends strongly on the inspiratory airflow and absolute lung capacity, both of which differ from patient to patient. Patient variability in inspiratory flow and volume causes the portion of the dose that is inhaled (referred to as the nominal dose) to vary considerably and be relatively low in some cases.7 Importantly, some powder formulations of inhaled drugs are extremely moisture-sensitive; adsorption of moisture can significantly increase drug-carrier adhesion, so decreasing the generation of inhalable drug particles, because a large fraction of the drug remains bound to the carrier and deposits in the oropharynx.8,9 In order to overcome the coordination problems associated with pressurized metered dose inhalers and utilize a patient-independent and reproducible energy supply in a platform that is insensitive to environmental moisture, a third approach was investigated, specifically, the feasibility of generating a single-breath, inhalable aerosol from a drug solution. There are several technically feasible methods for producing a pocket-sized device capable of aerosolizing a drug solution to produce a transient mist that could contain a full dose.

Three of the known methods were piezoelectric vibration,10 extrusion through micron-sized holes,11 and an electrohydrodynamic effect,12 but each required either electrical energy from a battery, or the transformation of mechanical energy into droplet-generating energy in a sufficiently efficient manner. In the case of the Respimat® Soft Mist™ Inhaler (SMI), the technical breakthrough was based on the approach of forcing drug solution through a two-channel nozzle using mechanical power.13 During this process, the solution is accelerated and split into two converging jets which collide at a carefully controlled angle, causing the drug solution to disintegrate into inhalable droplets. This patented procedure for aerosolizing a liquid requires only a small amount of mechanical energy, which is easily generated by the twisting action of a patient’s hand. This approach avoids many issues associated with the reliability and replacement of batteries and the cost and fragility of sophisticated electronic circuitry.

Design and development of the Respimat® SMI

Concept and development up to Phase II

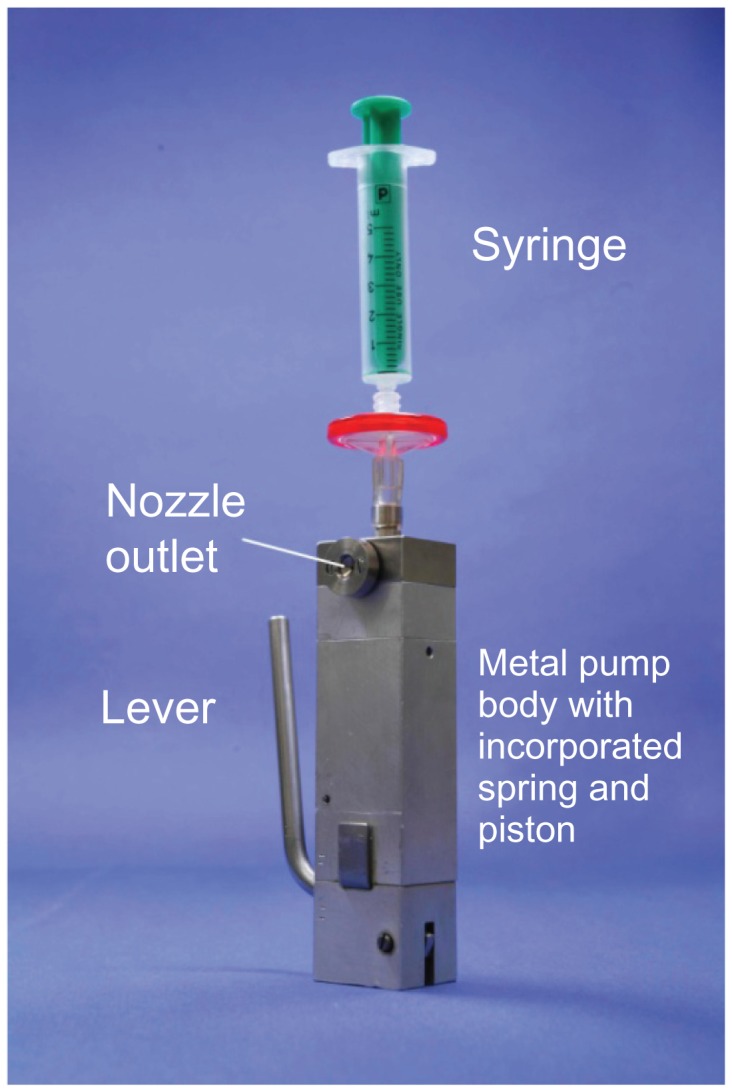

The single inhalation, aqueous spray concept was initially demonstrated in a laboratory model, which consisted of a metal pump body and a syringe serving as a solution reservoir (Figure 1). The device was operated by means of a lever which simultaneously compressed the spring and withdrew a 15.0 μL metered volume of drug solution from the reservoir. Pressing a trigger button released the spring which acted on the piston, forcing the metered volume through the micro-channels (5 × 8 μm2) to form liquid jets that impact 25 μm from the nozzle outlet to produce what has become known as a “soft mist” aerosol.

Figure 1.

Laboratory model used to demonstrate correct functioning of the concept for Respimat® Soft Mist™ Inhaler.

Note: Figure copyright © Boehringer Ingelheim Pharma GmbH Co KG. Reproduced with permission.

A feasibility study using an aqueous drug solution of a β2-agonist showed that the droplet size distribution of the aerosol was in the range suitable for inhalation; the majority of the particle mass was in the size range 1–5 μm. The product of the metered volume and drug concentration defined the metered dose, and 15.0 μL of formulation could be sprayed in approximately 1.2 seconds.

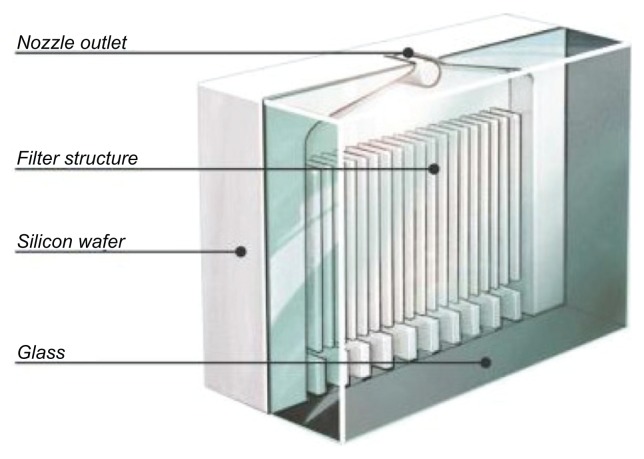

In this first model, the nozzle openings were 3–5 μm holes pierced into a stainless steel disc by a needle; but a nozzle design with higher reproducibility was needed. This was achieved by developing a “uniblock,” consisting of a silicon-glass material with dimensions of 2.5 × 2 × 1.1 mm3. By use of photolithographic and dry etching techniques adapted from the microelectronics industry, mass production of uniblocks, each comprising filter structures, inlet and outlet channels, and exit nozzles (Figure 2), was possible. Internal uniblock features are etched into the surface of the silicon substrate before the silicone is sandwiched between glass plates to create the flow path for the metered volume of drug solution. Currently, the accuracy of the photolithographic exposure process is better than 0.1 μm over a single uniblock. Anodic bonding between the silicon and glass is performed under high temperature and a strong electrical field, to ensure a leak-proof chemical bond is created with well-defined microfluidic channels and without the need for any adhesive.

Figure 2.

Schematic drawing of the uniblock.

Note: Reprinted from International Journal of Pharmaceutics, Vol 283, Issue 1–2, R Dalby, M Spallek, T Voshaar, A review of the development of Respimat® Soft Mist™ Inhaler, Pages 1–9, Copyright 2004, with permission from Elsevier.

Further development of the first laboratory model resulted in replacement of metal parts with components made from polymers whenever possible, and refinements to replace machined components with ones that could be molded and were suitable for mass production. This posed a special challenge, because the polymer parts had to withstand high mechanical stress, including static forces of 45 N over the lifetime of the device from the tension in the spring, and a transient pressure of about 25 MN/m2 during spraying. In addition, the torque required for cocking the spring was reduced to approximately 40 cNm, so that the energy needed to generate the aerosol could be easily produced by a typical user’s hand action. Drug solution within the Respimat® SMI is stored in a cartridge consisting of an aluminum cylinder containing a double-walled, plastic, collapsible bag, which contracts as the solution is withdrawn (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Cartridge of placebo solution and a cross-section of the double-walled bag used to contain the solution within the cartridge.

The initially sterile drug solution may be formulated with either ethanol, which acts both as a solvent and preservative, or water with added preservatives (typically benzalkonium chloride). Either strategy maintains the microbial stability of the solution after initial puncture of the cartridge when the device is first used by the patient. Patient use of the Respimat® SMI does not result in microbiological contamination of the unaerosolized inhalation solution in the cartridge.14

The design and ease-of-use refinements described above resulted in the Respimat® SMI version IV (Figure 4), which was tested in device handling studies and used in Phase II and Phase III clinical trials.

Figure 4.

Prototype IV of the Respimat® Soft Mist™ Inhaler used in clinical trials.

Note: Figure copyright © Boehringer Ingelheim Pharma GmbH Co KG. Reproduced with permission.

Production of the marketed version of Respimat® SMI

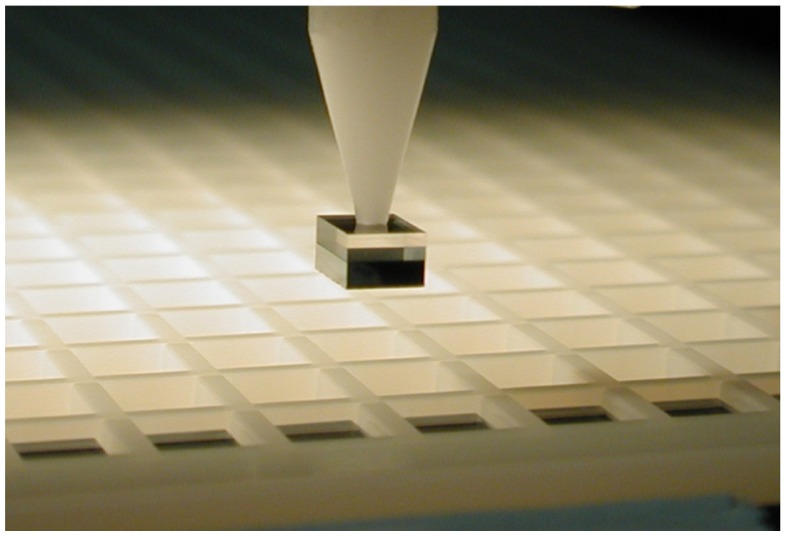

For Phase III clinical trials and to investigate the reliability of the Respimat® SMI, several thousand devices were needed before final molds and production tools were available, so some plastic parts, the drug solution cartridge, and uniblocks were not made using commercial scale processes, and units were assembled by hand. Later, uniblock production leveraged microchip industry technology to make 2000 individual uniblocks from a single 6-inch silicon wafer. After the wafer is etched with the channel structure and bonded to a glass plate for creating and sealing the channels, individual uniblocks are cut by a circular saw with a thin diamond blade. In the commercial production process, precision holding, cutting, and transport of individual uniblocks is achieved by fixing the wafers to polymer foil, then cutting through the wafer and one third of the foil thickness to leave all 2000 nozzles precisely separated from each other on the foil.

A vacuum gripper takes uniblocks from the foil and a high-resolution camera checks their structural integrity before each is placed into a magazine (Figure 5) for transfer to the device assembly line. Molding tools for producing the plastic parts used in the Respimat® SMI and the cartridge were scaled up by increasing the number of cavities in the production molds. Scaleup of cartridge production was technically demanding because temperature and pressure played key roles in forming the container out of a double polymer tube by means of a coextrusion process. The tubes are extruded and inflated in molds under moderate heat, forming the container geometry at several stations simultaneously.

Figure 5.

Magnified view of the “pick and place” process used to put the uniblocks into a magazine for transfer to the assembly line.

During scaleup, it was imperative to retain the design and materials used during Phase III clinical trials whenever possible, to minimize the workload associated with demonstrating that the new component did not alter device performance. However, when changes proved necessary, such as a modified mouthpiece in commercial units of the Respimat® SMI (Figure 6), or the need to attach caps over the mouthpiece more securely to avoid accidental loss, comprehensive validation studies were conducted to demonstrate that these design changes did not alter performance.

Figure 6.

Comparison of the mouthpiece and cap of the Phase II (left) and marketing versions of the Respimat® Soft Mist™ Inhaler (right).

Note: Figure copyright © Boehringer Ingelheim Pharma GmbH Co KG. Reproduced with permission.

Because off-the-shelf assembly and filling lines did not exist for this novel technology platform, customized machines were conceived and constructed for automatically assembling all parts of the Respimat® SMI (Figure 7). Inline quality checks, many using automated vision systems and statistical process control, were incorporated after almost every stage of assembly. With minimal operator intervention, the continuous production process is highly automated and maintains a consistently high quality level and low rejection rate. In retrospect, design of the assembly line was as demanding as design of the device itself, a fact that should not be overlooked by developers of novel inhalation devices.

Figure 7.

Part of the production line for the automatic assembly of the Respimat® Soft Mist™ Inhaler.

Note: Figure copyright © Boehringer Ingelheim Pharma GmbH Co KG. Reproduced with permission.

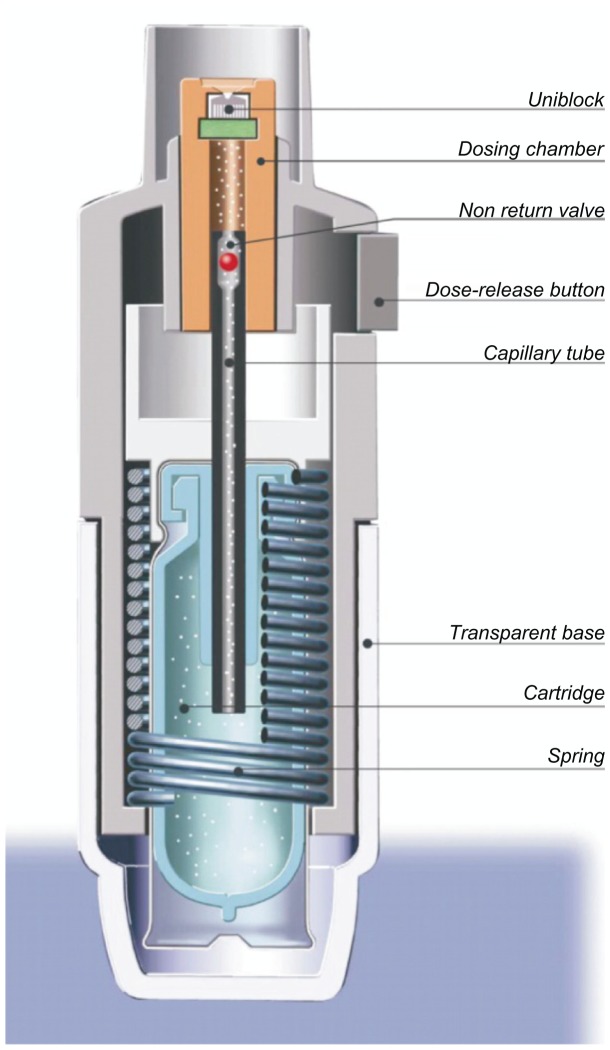

Operating the Respimat® SMI

Ease of operation and an intuitive design that encourages correct use are necessary features of any drug delivery device that requires manipulation by the patient before inhaling medication. The principal parts of the Respimat® SMI are shown in Figure 8. To use the device, the patient removes the transparent base, inserts the cartridge containing the drug solution, and replaces the base. When a cartridge is inserted for the first time, the device has to be primed to expel air from the drug solution flow path. After this one-time setup, the cartridge is permanently connected by a capillary tube containing a nonreturn valve to the fixed-volume dosing chamber, and the device is ready for routine use. To load a dose, the patient simply turns the base of the device half a turn (180°) until it clicks. The helical cam gear transforms the rotation into a linear movement, which tightens the spring and moves the capillary with the nonreturn valve to a defined lower position. During this movement, the drug solution is drawn through the capillary tube into the dosing chamber, as shown in Figure 8. When the patient presses the dose-release button to actuate the device, the mechanical power stored in the spring pushes the capillary with the now closed nonreturn valve to the upper position. This operation drives the metered volume of drug solution (15 μL) through the twin nozzles of the uniblock, so that two fine jets of liquid converge at a carefully controlled angle. Impact of the two jets generates a slow-moving aerosol cloud from which the term “soft mist” is derived.

Figure 8.

Schematic drawing of the key elements of the Respimat® Soft Mist™ Inhaler.

Note: Reprinted from International Journal of Pharmaceutics, Vol 283, Issue 1–2, R Dalby, M Spallek, T Voshaar, A review of the development of Respimat® Soft Mist™ Inhaler, Pages 1–9, Copyright 2004, with permission from Elsevier.

The commercial device is designed to deliver a monthly supply of drug, and can be configured to deliver 60 or 120 metered actuations, depending on the daily dosing frequency. The device has a dose indicator to show patients approximately how many doses remain and to remind the patient to refill the prescription in good time. The dose indicator enters the red zone a week before the last dose is due to be inhaled (assuming the patient is fully adherent to the prescribed dosing schedule). A locking mechanism automatically prevents the use of the device after the specified number of actuations have been delivered. This ensures that there is no detectable “tailoff,” which is a common problem with pressurized metered dose inhalers and results in emitted doses becoming ever smaller as the canister nears exhaustion. In addition to incorporation of a hinged cap, additional modifications were made to the Respimat® SMI in advance of its launch, to address learning from device handling studies and regulatory assessments. These included a company internal color-coding to identify the specific drug class contained in the device (eg, color-code for Berodual® Respimat®: grey, green, green) and a transparent base to allow easy identification of the drug inside. An illustration of the marketed Respimat® SMI, which is similar in size and weight to pressurized metered dose inhalers and dry powder inhalers such as the Turbuhaler and Diskus, is shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

The marketed version of the Respimat® Soft Mist™ Inhaler compared with the Diskus® and Turbuhaler®.

Abbreviation: SMI, Soft Mist™ Inhaler.

Note: Figure copyright © Boehringer Ingelheim Pharma GmbH Co KG. Reproduced with permission.

Technical performance data for Respimat® SMI

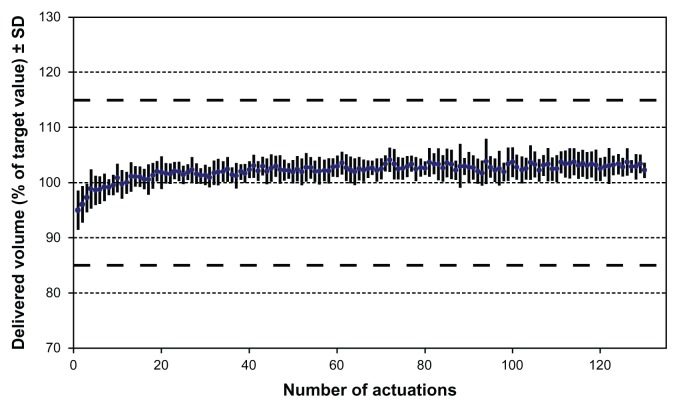

The objective of inhalation therapy is delivery of a full dose of medication to a patient’s lungs each time they use a device. Several in vitro parameters are used to qualify the performance of a device, demonstrate reproducible performance, and to compare the performance of different devices. Stringent requirements associated with delivered dose reproducibility must be met to obtain device approval by regulatory authorities (especially the US Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency). Because the drug in the Respimat® SMI is formulated as a solution, the uniformity of the delivered dose can be calculated from the weight loss after each actuation, the density of the drug solution, and the concentration of the dissolved drug. An example of typical dose reproducibility is shown in Figure 10.15

Figure 10.

Spray volume uniformity for an aqueous solution over 120 actuations delivered via the Respimat® Soft Mist™ Inhaler.

Notes: Data shown are mean of ten devices from three batches;16 range of target volume/weight according to Food and Drug administration guidance: nasal spray and inhalation solution. Reprinted from International Journal of Pharmaceutics, Vol 283, Issue 1–2, R Dalby, M Spallek, T Voshaar, A review of the development of Respimat® Soft Mist™ Inhaler, Pages 1–9, Copyright 2004, with permission from Elsevier.

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation.

Because the Respimat® SMI has a lockout mechanism that is activated when the rated number of actuations have been delivered, the volume of each dose delivered by the device is consistent throughout the label claim number of actuations, and no “tailoff ” is observed. In general, it is easier to achieve dose-to-dose reproducibility by delivering a small volume of a drug solution from a reservoir than a small quantity of suspension or powder.

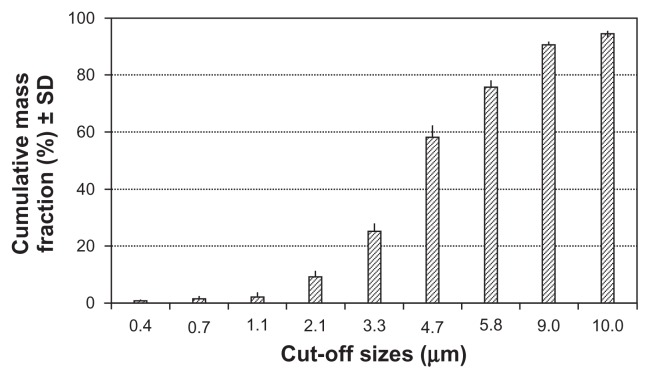

Three physical parameters that are particularly relevant when considering the effectiveness of drug delivery from the Respimat® SMI are particle size (droplet size), aerosol speed at the point of droplet generation, and duration of cloud extrusion. The Respimat® SMI was designed to aerosolize most of the metered volume in the form of droplets with a diameter of >1 μm (to avoid loss of small droplets during the subsequent exhalation) and <5.8 μm (to facilitate efficient lung deposition).1 A well-established parameter for quantifying the particle size of a pharmaceutical aerosol is the fine particle fraction, which expresses (as a percentage) the proportion of drug mass in aerosolized particles that is carried by particles with an aerodynamic diameter ≤5.8 μm. The fine particle fraction for the Respimat® SMI is approximately 75% with most formulations, which is nearly double the value reported for aerosols generated by pressurized metered dose inhalers and dry powder inhalers.16,17 A typical particle size distribution is shown in Figure 11.15

Figure 11.

Typical aerodynamic particle size distribution for the aerosol generated by the Respimat® Soft Mist™ Inhaler, using an aqueous drug solution and an Andersen Cascade Impactor (Lab Automate Technologies, Milburn, NJ), at relative humidity of >90%. Data are mean cumulative mass fractions (%) and standard deviation.14

Note: Reprinted from International Journal of Pharmaceutics, Vol 283, Issue 1–2, R Dalby, M Spallek, T Voshaar, A review of the development of Respimat® Soft Mist™ Inhaler, Pages 1–9, Copyright 2004, with permission from Elsevier.

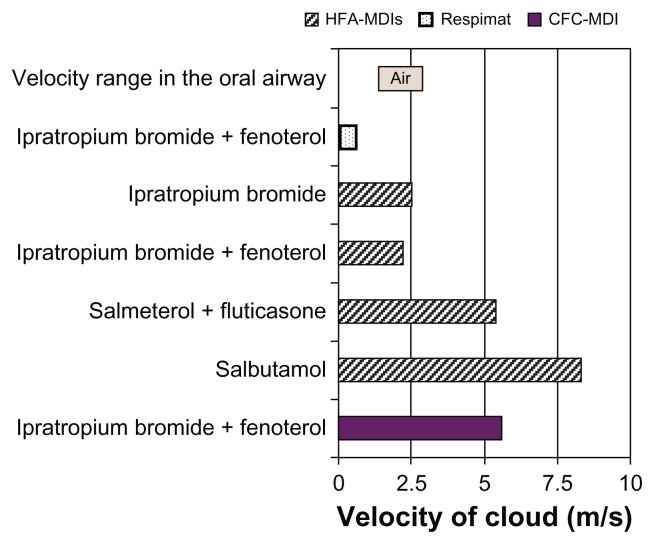

A second parameter that influences where drug is deposited is the velocity of the particle during inhalation; if the velocity is too high, this promotes particle impaction in the throat at the expense of drug reaching the lungs. Measurements based on video recording have shown that the soft mist emerges from the uniblock at a velocity of 0.8 m/sec, which is approximately 3–10 times slower than the speed of release of an aerosol cloud from a pressurized metered dose inhaler (Figure 12).18 The velocity of the aerosol cloud generated from the Respimat ® SMI is in the lower range of the inspiratory airflow of a patient,19 which is a design element expected to increase lung deposition and reduce oropharyngeal deposition.

Figure 12.

Mean aerosol spray velocities of selected respiratory medications delivered via chlorofluorocarbon-pressurized metered dose inhalers, hydrofluoroalkane-pressurized metered dose inhalers, or the Respimat® Soft Mist™ Inhaler,18 and velocity range in the oral airway.19

Abbreviations: CFC, chlorofluorocarbon; HFA, hydrofluoroalkane; MDI, metered dose inhaler.

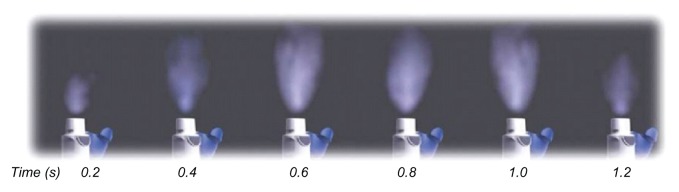

The spray duration of the Respimat® SMI (approximately 1.2 seconds; Figure 13) is considerably longer than for pressurized metered dose inhalers (typically 0.15–0.36 seconds according to Hochrainer et al18). The long spray duration of the soft mist allows the patient a better chance of coordinating the inhalation maneuver with the drug release.

Figure 13.

Photographs, taken at intervals of 0.2 sec, showing generation of mist from the Respimat® Soft Mist™ Inhaler.

Note: Reprinted from International Journal of Pharmaceutics, Vol 283, Issue 1–2, R Dalby, M Spallek, T Voshaar, A review of the development of Respimat® Soft Mist™ Inhaler, Pages 1–9, Copyright 2004, with permission from Elsevier.

Clinical performance data for Respimat® SMI

Phase I clinical data

Improvement of the in vitro performance of the aerosol from the Respimat® SMI compared with that from a pressurized metered dose inhaler with respect to particle size distribution, particle velocity, and spray duration was expected to have a beneficial impact on the proportion of an emitted drug dose that reaches the lung. This was investigated by using gamma scintigraphy to detect and quantify the amount of different radiolabeled formulations in the body after inhalation.

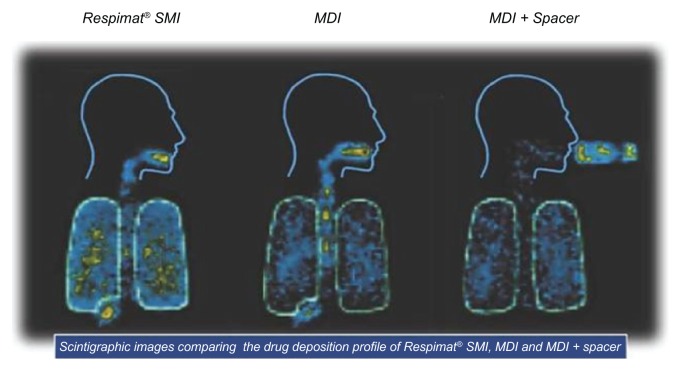

Newman et al investigated lung and oropharyngeal deposition of flunisolide administered to twelve healthy volunteers via the Respimat® SMI, a pressurized metered dose inhaler, and a pressurized metered dose inhaler plus an Inhacort® spacer (Boehringer Ingelheim, Ingelheim, Germany).20 Mean whole lung deposition of flunisolide from the Respimat® SMI (39.7%) was significantly higher than from the pressurized metered dose inhaler (15.3%) or pressurized metered dose inhaler plus spacer (28.0%). Typical scans of the distribution of radiolabeled aerosol from each device are shown in Figure 14.

Figure 14.

Scintigraphic scans from one individual showing the deposition of radiolabeled (99mTc) aerosol in the lungs immediately after administration of a single dose of 250 μg flunisolide delivered via the Respimat® SMI, pressurized metered dose inhaler, or pressurized metered dose inhaler plus spacer, on each of three study days.

Abbreviations: SMI, Soft Mist™ Inhaler; MDI, pressurized metered dose inhaler.

Note: Reprinted from International Journal of Pharmaceutics, Vol 283, Issue 1–2, R Dalby, M Spallek, T Voshaar, A review of the development of Respimat® Soft Mist™ Inhaler, Pages 1–9, Copyright 2004, with permission from Elsevier.

In a subsequent study, also in twelve healthy volunteers, similar results were reported for lung deposition of the bronchodilator, fenoterol. A detailed analysis of the deposited amount of fenoterol in different regions of the body and on the surface of the device is given in Table 1.21 Mean oropharyngeal deposition of fenoterol was significantly lower via the Respimat ® SMI than via the pressurized metered dose inhaler (37.1% versus 71.7% of metered dose, respectively). The use of a spacer also considerably reduced oropharyngeal deposition, but in this configuration most of the drug remained on the internal surface of the spacer. In another similar study, the dose deposited in the lungs of patients with asthma was significantly higher when inhaled from the Respimat® SMI than from a pressurized metered dose inhaler or Turbuhaler.22

Table 1.

Deposition of fenoterol in lung and oropharynx after delivery from three different inhaler devices in healthy volunteers21

| Amount of fenoterol (as % of metered dose) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| Respimat® SMI | pMDI | pMDI plus spacer | |

| Whole lung | 39.2 (12.7) | 11.0 (4.9) | 9.9 (3.4) |

| Central zone | 11.0 (3.7) | 3.1 (1.1) | 2.5 (0.9) |

| Intermediate zone | 14.1 (4.9) | 3.7 (1.8) | 3.6 (1.2) |

| Peripheral zone | 14.1 (4.8) | 4.2 (2.1) | 3.8 (1.5) |

| Oropharynx | 37.1 (10.4) | 71.7 (7.4) | 3.6 (2.4) |

| Delivery device | 21.9 (6.1) | 16.7 (5.4) | 86.2 (5.2) |

| Exhaled air | 1.9 (1.7) | 0.6 (0.4) | 0.4 (0.3) |

Abbreviations: pMDI, pressurized metered dose inhaler; SMI, Soft Mist™ Inhaler.

From this type of experiment, it can be seen that the dose reaching the lung of a patient is approximately doubled by using the Respimat® SMI compared with other inhalers (when the same metered dose of the drug is delivered from each device). This suggests that smaller nominal doses could be used with the Respimat® SMI to obtain the same pharmacodynamic effect, so potentially reducing side effects. This concept has been tested in a number of clinical trials.

Phase II/II clinical data

The Respimat® SMI is being primarily developed for the inhaled delivery of a range of drugs for the treatment of asthma and/or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The first drug to be clinically developed in the device was the fixed combination of fenoterol hydrobromide + ipratropium bromide (F/I) (Berodual® Respimat®). F/I is indicated for the symptomatic treatment of airways narrowing in patients with asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The improved delivery was demonstrated in a study of adults with asthma which used forced expiratory volume in one second as a pharmacodynamic parameter, and included comparative pharmacokinetic measurements based on plasma concentration and urinary excretion.23 It was shown that F/I doses of 25/10 μg delivered by the Respimat® SMI have nearly the same pharmacodynamic effect as a F/I dose of 100/40 μg administered by pressurized metered dose inhaler. Furthermore, there was a two-fold greater systemic availability of both drugs following inhalation via the Respimat® SMI compared with the pressurized metered dose inhaler.

The concept was further substantiated in two Phase III trials in asthma patients, one in adults and one in children.24,25 These studies found that F/I doses of 25/10 μg and 50/20 μg administered via the Respimat® SMI produced bronchodilator responses comparable with those achieved with 100/40 μg via a pressurized metered dose inhaler. Hence, the Respimat® SMI enables a two-fold to four-fold reduction of the daily dosage of F/I without loss of therapeutic efficacy and with a similar safety profile. A third study in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease also showed that, by using the Respimat® SMI, the daily nominal dose of F/I can be reduced by 50% while offering similar efficacy and safety.26

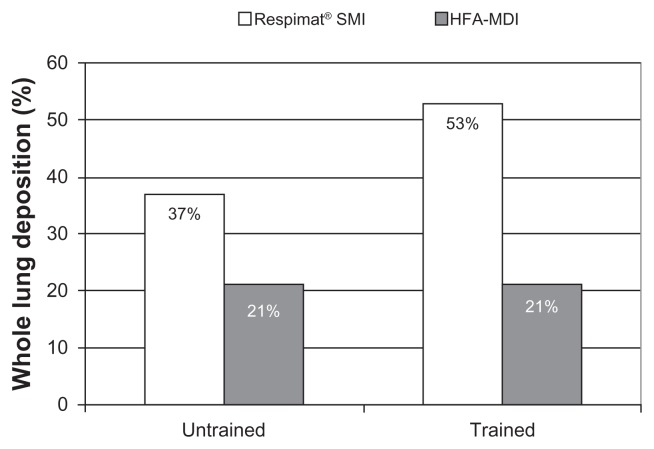

The Respimat® SMI was also tested in a clinical trial of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease who had difficulty in coordinating inhaler actuation with inspiration. 27 This trial also addressed whether training the patient in how to use the Respimat® SMI and a hydrofluoroalkane-pressurized metered dose inhaler improved lung deposition. As depicted in Figure 15, lung deposition in this specific patient population was doubled by using the Respimat® SMI rather than a hydrofluoroalkane-pressurized metered dose inhaler. The study also showed that deposition was improved for the Respimat® SMI after training, whereas no improvement was observed for the hydrofluoroalkane-metered dose inhaler.

Figure 15.

Lung deposition from the Respimat® SMI and hydrofluoroalkane-pressurized metered dose inhaler in 13 patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease before and after inhaler training. Data are mean proportion (as %) of the delivered dose deposited in the lung.27

Abbreviations: HFA, hydrofluoroalkane; SMI, Soft Mist™ Inhaler; MDI, pressurized metered dose inhaler.

Patient preference and satisfaction with Respimat® SMI

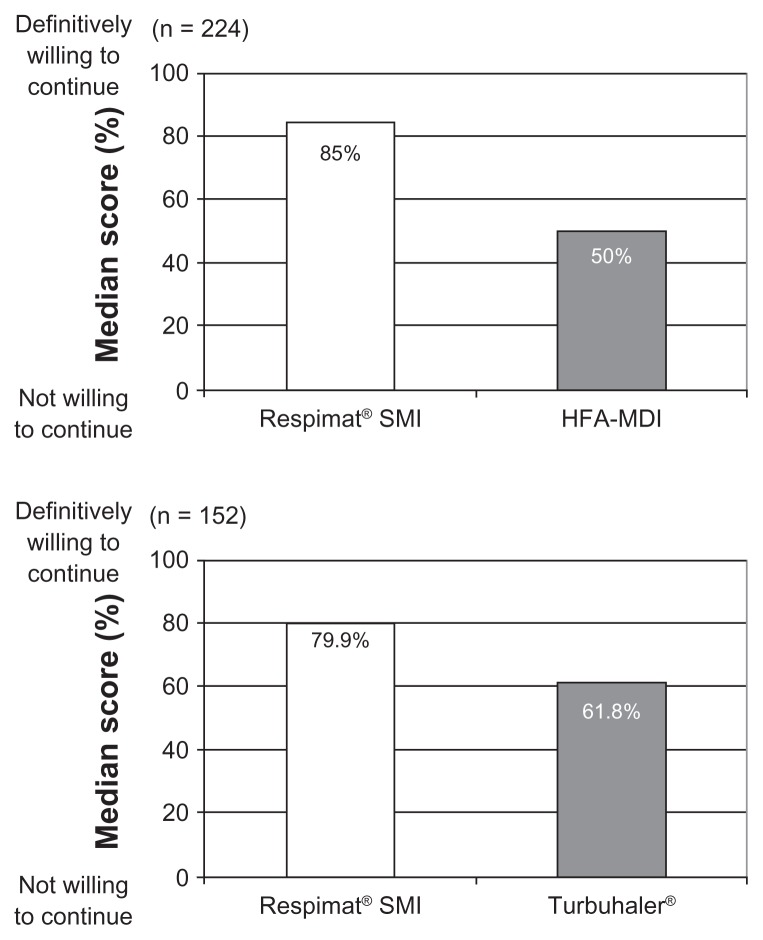

The physician’s choice of inhaler for a particular patient is likely to be based on many variables, including those that may be important determinants of adherence to therapy. These include the drug products, clinical benefit, economics, ease of use, dosing schedule, portability, taste, adverse effects, and sociocultural factors, such as belief, knowledge, and education. A review of the literature on inhaler device preference and satisfaction showed that most patient questionnaires were developed without input either from patients or from personnel with experience of psychometric testing, and that only two were developed by health outcomes specialists and tested for validity.28 One of these instruments was the Patient Satisfaction and Preference Questionnaire, which is a practical, validated, reliable, and responsive instrument for testing satisfaction with, preference for, and willingness to continue using an inhaler device.29 The Patient Satisfaction and Preference Questionnaire was used in a study that compared patient preference for the Respimat® SMI and a pressurized metered dose inhaler,30 in which 224 patients with asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or both, inhaled the same drug (F/I) from each device; the patients had also used pressurized metered dose inhalers before. This study demonstrated that the majority of patients preferred the Respimat® SMI to pressurized metered dose inhaler, found the Respimat® SMI easy to assemble, and were willing to continue using it. The willingness of patients to continue using the device was significantly higher for the Respimat® SMI than for the pressurized metered dose inhaler,30 and a similar result was reported in another study that compared the Respimat® SMI with the Turbuhaler in patients with asthma (Figure 16).31

Figure 16.

Willingness-to-continue scores in patients with asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (or both) who inhaled drug from the Respimat® SMI and either the hydrofluoroalkane-pressurized metered dose inhaler or Turbuhaler® in two separate trials.30,31

Abbreviations: HFA, hydrofluoroalkane; SMI, Soft Mist™ Inhaler; MDI, pressurized metered dose inhaler.

Conclusion

For the inhaled administration of drugs, there are effectively three commercialized single-breath inhaler platforms available, each based on a unique technical approach. Dry powder inhalers are “passive” inhalers which use the energy associated with the inspiratory airflow of the patient to aerosolize a premeasured amount of micronized drug. In addition, there are two “active” inhaler platforms; one which utilizes a propellant (the pressurized metered dose inhaler), and one which operates on mechanical energy, as realized in the development of the Respimat® SMI. The Respimat® SMI has the benefit of not requiring a propellant, so reducing environmental concerns, and generates an inhalable aerosol cloud with arguably superior properties to those of the pressurized metered dose inhaler and dry powder inhaler platforms.

The properties of the aerosol cloud generated by the Respimat® SMI in terms of droplet size distribution, aerosol velocity, and aerosol generation time results in higher drug deposition in the lung compared with aerosols produced by dry powder inhalers or pressurized metered dose inhalers. Clinical studies support this finding by demonstrating that a considerably smaller dose of a combination bronchodilator, compared with delivery via a pressurized metered dose inhaler, results in the same level of efficacy and safety. However, the metered volume of 15 μL limits the dose delivery capacity of the marketed design to drugs with adequate solubility with respect to the required dose. The limitations of the dose delivery capacity could be overcome by increasing the volume or number of puffs administered, but this would have to be balanced against the risk of reduced patient compliance. Handling studies have shown that patients are comfortable with using the Respimat® SMI, and prefer the device and the soft mist it delivers to other inhaler platforms. Production of all the device components and the automatic assembly of the Respimat® SMI is scaled up so that a reliable market supply is ensured. Therefore, the Respimat® SMI is an innovative development in pulmonary drug delivery and can be expected to serve as a base technology for the delivery of more drugs in the future.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Ms Marion Frank for helpful discussions and Dr Herbert Wachtel for support in preparing the figures.

Footnotes

Disclosure

RD is a paid consultant to Boehringer Ingelheim.

References

- 1.Smith G, Hiller C, Mazumder R, Bone R. Aerodynamic size distribution of cromolyn sodium at ambient and airway humidity. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1980;121:513–517. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1980.121.3.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Köhler D, Fleischer W, Matthys H. New method for easy labeling of beta-2-agonists in the metered dose inhaler with technetium 99 m. Respiration. 1988;53:65–73. doi: 10.1159/000195399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Newman SP, Pavia D, Clarke SW. How should a pressurized beta-adrenergic bronchodilator be inhaled? Eur J Respir Dis. 1981;62:3–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crompton EK. Problems patients have using pressurized aerosol inhalers. Eur J Respir Dis Suppl. 1982;119:101–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pedersen S, Ostergaard PA. Nasal inhalation as a cause of inefficient pulmonal aerosol inhalation technique in children. Allergy. 1983;38:191–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.1983.tb01605.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Handbook for the Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer. 7th ed. 2006. [Accessed May 2, 2011]. Available from: http://ozone.unep.org/Publications/MP_Handbook/index.shtml.

- 7.Meakin BJ, Ganderton D, Panza I, Ventura P. The effect of flow rate on drug delivery from the Pulvinal, a high-resistance dry powder inhaler. J Aerosol Med. 1988;11:143–152. doi: 10.1089/jam.1998.11.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ganderton D. General factors influencing drug delivery to the lung. Respir Med. 1997;91(Suppl A):13–16. doi: 10.1016/s0954-6111(97)90099-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ganderton D. Targeted delivery of inhaled drugs: Current challenges and future goals. J Aerosol Med. 1999;12(Suppl 1):3–8. doi: 10.1089/jam.1999.12.suppl_1.s-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Young LR, Chambers I, Narayan S, Wu C. The aerodose multidose inhaler device design and delivery characteristics. In: Dalby RN, Byron PR, Farr SJ, editors. Respiratory Drug Delivery VI. Buffalo Grove, IL: Interpharm Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schuster J, Rubsamen R, Lloyd P, Lloyd J. The AERx aerosol delivery system. Pharm Res. 1997;14:354–357. doi: 10.1023/a:1012058323754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zimlich WC, Ding JY, Busick DR, et al. The development of a novel electrohydrodynamic pulmonary drug delivery device. In: Dalby RN, Byron PR, Farr SJ, Peart J, editors. Respiratory Drug Delivery VII. Raleigh, NC: Seratec Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zierenberg B. Optimizing the in vitro performance of Respimat®. J Aerosol Med. 1999;12:19–24. doi: 10.1089/jam.1999.12.suppl_1.s-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schmelzer C, Bagel C. Microbiological integrity of Respimat® soft mist inhaler (SMI) cartridges after use in COPD patients. J Aerosol Med. 2001;14:385P1–385P3. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dalby R, Spallek M, Voshaar T. A review of the development of Respimat ® Soft Mist™ Inhaler. Int J Pharm. 2004;283:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2004.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Van Noord JA, Smeets JJ, Creemers JP, Greefhorst LP, Dewberry H, Cornelissen PJ. Delivery of fenoterol via Respimat®, a novel soft mist inhaler. Respiration. 2000;67:672–678. doi: 10.1159/000056298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Steed KP, Freund B, Towse L, Newman SP. High lung deposition of fenoterol from BINEB, a novel multiple dose nebuliser device [Abstract] Eur Respir J. 1995;8(Suppl 19):204. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hochrainer D, Hölz H, Kreher C, Scaffidi L, Spallek M, Wachtel H. Comparison of the aerosol velocity and spray duration of Respimat® Soft Mist™ Inhaler and pressurized metered dose inhalers. J Aerosol Med. 2005;18:273–282. doi: 10.1089/jam.2005.18.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang Z, Kleinstreuer C, Kim CS. Micro-particle transport and deposition in a human oral airway model. J Aerosol Sci. 2002;33:1635–1652. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Newman SP, Steed KP, Reader SJ, Hooper G, Zierenberg B. Efficient delivery to the lungs of flunisolide aerosol from a new portable handheld multidose nebulizer. J Pharm Sci. 1996;85:960–964. doi: 10.1021/js950522q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Newman SP, Brown J, Steed KP, Reader SJ, Kladders H. Lung deposition of fenoterol and flunisolide delivered using a novel device for inhaled medicines. Chest. 1998;113:957–963. doi: 10.1378/chest.113.4.957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pitcairn G, Reader S, Pavia D, Newman S. Deposition of corticosteroid aerosol in the human lung by Respimat® Soft Mist™ Inhaler compared to deposition by metered dose inhaler or by Turbuhaler® dry powder inhaler. J Aerosol Med. 2005;18:264–272. doi: 10.1089/jam.2005.18.264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goldberg J, Freund E, Beckers B, Hinzmann R. Improved delivery of fenoterol plus ipratropium bromide using Respimat® compared with a conventional metered dose inhaler. Eur Respir J. 2001;17:225–232. doi: 10.1183/09031936.01.17202250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vincken W, Bantje T, Middle MV, Gerken F, Moonen D. Long-term efficacy and safety of ipratropium bromide plus fenoterol via Respimat® Soft Mist Inhaler (SMI) versus a pressurised metered-dose inhaler in asthma. Clin Drug Invest. 2004;24:17–28. doi: 10.2165/00044011-200424010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Von Berg A, Jeena PM, Soemantri PA, et al. Efficacy and safety of ipratropium bromide plus fenoterol inhaled via Respimat® Soft Mist Inhaler vs a conventional metered dose inhaler plus spacer in children with asthma. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2004;37:264–272. doi: 10.1002/ppul.10428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kilfeather SA, Ponitz HH, Beck E, et al. Improved delivery of ipratropium bromide/fenoterol from Respimat® Soft Mist Inhaler in patients with COPD. Respir Med. 2004;98:387–397. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2003.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brand P, Hederer B, Austen G, Dewberry H, Meyer T. Higher lung deposition with Respimat® Soft Mist Inhaler than HFA-MDI in COPD patients with poor technique. Int J COPD. 2008;3:1–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Anderson P. Patient preference for and satisfaction with inhaler devices. Eur Respir Rev. 2005;14:109–116. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kozma CM, Slaton TL, Monz BU, Hodder R, Reese PR. Development and validation of a patient satisfaction and preference questionnaire for inhalation devices. Treat Respir Med. 2005;4:41–52. doi: 10.2165/00151829-200504010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schürmann W, Schmidtmann S, Moroni P, Massey D, Qidan M. Respimat® Soft Mist Inhaler versus hydrofluoroalkane metered dose inhaler: Patient preference and satisfaction. Treat Respir Med. 2005;4:53–61. doi: 10.2165/00151829-200504010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hodder R, Reese PR, Slaton T. Asthma patients prefer Respimat® Soft Mist™ Inhaler to Turbuhaler®. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2009;4:225–232. doi: 10.2147/copd.s3452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]