Abstract

Purpose

Fracture of femur is a painful bone injury, worsened by any movement. This prospective study was performed to compare the analgesic effects of femoral nerve block (FNB) with intravenous (IV) fentanyl prior to positioning patients with fractured femur for spinal block.

Patients and methods

Sixty-four ASA I–III patients aged 18–80 years undergoing surgery for femur fracture were randomized into two groups. Fifteen minutes before spinal block, the FNB group received nerve stimulator-assisted FNB with a mixture of 20 mL bupivacaine 0.5% and 10 mL normal saline 0.9%, and the fentanyl group received two doses of IV fentanyl 0.5 μg/kg with a five-minute interval between doses. Numeric rating pain scores were compared. During positioning, fentanyl in 0.5 μg/kg increments was given every five minutes until pain scores were ≤4.

Results

There were no statistically significant differences between the groups according to pain scores, need for additional fentanyl, and satisfaction with positioning before spinal block.

Conclusion

We were unable to demonstrate a benefit of FNB over IV fentanyl for patient positioning before spinal block. However, FNB can provide postoperative pain relief, whereas side effects of fentanyl must be considered, and analgesic dosing should be titrated based on pain scores. A multimodal approach (FNB + IV fentanyl) may be a possible option.

Keywords: femoral nerve block, bupivacaine, fentanyl, pain on positioning

Introduction

Fracture of femur is a particularly painful bone injury because the periosteum has the lowest pain threshold of the deep somatic structures.1 Surgical repair most commonly involves either internal fixation of the fracture or replacement of the femoral head with arthroplasty.2,3 At our institution, spinal block was used more frequently than general anesthesia (GA) for femoral fracture surgery. However, any movement of the patient leads to severe pain. Providing adequate pain relief not only increases comfort in these patients, but has also been shown to improve positioning for spinal block. Analgesics or femoral nerve block (FNB) are often used to help the patient tolerate positioning. There are few data4,5 to establish a benefit of one form of anesthetic over another in this situation. This prospective study was performed to compare the analgesic effects of FNB with intravenous (IV) fentanyl prior to positioning for spinal block in patients with fractured femur.

Material and methods

After obtaining institutional approval and written informed consent, we recruited 64 patients with fractured femur between December 2006 and May 2008 for this prospective, randomized, controlled trial. Inclusion criteria were age 18–80 years, ASA physical status I–III, bodyweight >50 kg, and being scheduled for surgery under spinal block. Exclusion criteria were multiple fractures, peripheral neuropathy, bleeding disorders, mental disorders, communication failure, allergy to local anesthetics, and use of analgesics for premedication. However, light premedication such as oral benzodiazepines (midazolam or diazepam) could be given. The patients were allocated by computer-generated random numbers into two groups of 32 patients each: an FNB group and a fentanyl group. The random allocation sequence was concealed in opaque, sealed envelopes until a group was assigned.

On arrival in the induction area, all patients were monitored with electrocardiography, pulse oximeter, and non-invasive blood pressure measurement. An infusion of lactated Ringer’s solution was given and all patients were supplied with oxygen (6 L/min) via a face mask. Patients in the FNB group received FNB guided by a peripheral nerve stimulator (Stimuplex; B Braun, Melsungen, AG). FNB was performed by one of two anesthesiologists (AI or MR). An insulated 50 mm 22 G needle was introduced 1 cm lateral to the femoral artery and just below the inguinal ligament. When a current 0.2–0.4 mA elicited a quadriceps contraction, 30 mL of bupivacaine 0.3% (a mixture of 20 mL of bupivacaine 0.5% and 10 mL of normal saline 0.9%) was injected incrementally after a negative aspiration test. Patients in the fentanyl group received two doses of IV fentanyl 0.5 μg/kg with a five-minute interval between doses. Pain scores were assessed at 15 minutes after intervention with FNB or IV fentanyl. The patient was then turned into the lateral position with the fracture site up. If any patient in either group reported pain scores >4 during positioning, IV fentanyl 0.5 μg/kg was given every five minutes until the pain score decreased to ≤4. Thereafter a spinal block was performed by the resident under supervision by one of two anesthesiologists (AI or MR) in either the midline or paramedian approach at the L2/3 or L3/4 level, and 2.0–4.0 mL of isobaric bupivacaine 0.5% was injected according to the anesthesiologist’s decision. Pain scores 15 minutes after analgesia and during positioning were recorded. A numeric rating pain scale (0 = no pain, 10 = maximal pain) was used. Additional fentanyl requirement during positioning and satisfaction with patient position maintained for spinal block (yes = satisfactory, no = not satisfactory) were also recorded. All patients were aware of their treatment group allocation. The rationale for lack of blinding is that we considered placebo injection unacceptable. Assessors of pain were blinded to the patients’ allocated tretment group, and remained outside the operating room during administration of FNB or fentanyl. Thereafter, they came into the operating room to assess the pain score.

Statistical analysis

The sample size required for this study was estimated from our findings in 10 pilot patients. Our pilot study had demonstrated that patients given FNB had lower pain scores (mean = 2) during positioning. Based on α = 0.05, β = 0.20 and a mean difference of 2.2 in pain score, with an estimated standard deviation of 3.46, a sample size of 32 per group was required for one-tailed testing. Data were analyzed using an SPSS 13.0 software package. Parametric variables were described as mean ± SD; qualitative variables were described as number (percentage) and as median and range. Student’s t-test, Chi-square test or Fisher exact test, or Mann-Whitney U test was used as appropriate to compare the two groups. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

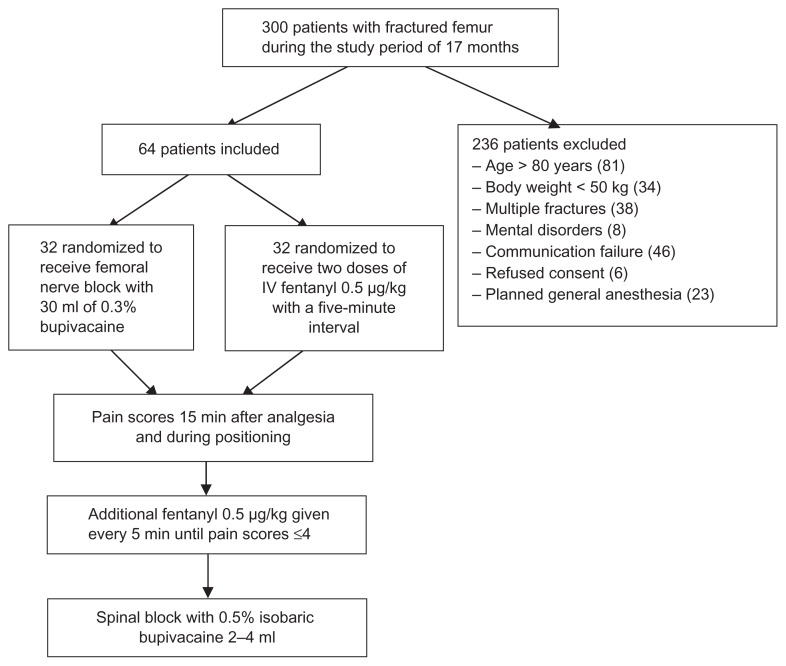

During the study period there were about 300 patients presenting for surgical repair of femoral fracture but only 64 patients were included in this study. Many patients were excluded for reasons given in the exclusion criteria (Figure 1). Demographics according to ASA physical status, age, sex, and weight were not significantly different between the treatment groups (Table 1). Time from trauma to surgery was significantly longer in the fentanyl group compared with that in the FNB group (P = 0.03). Fracture sites mostly involved the proximal femur. The majority of patients in the FNB group had femoral neck fractures whereas the fentanyl group mostly had intertrochanteric fractures (P = 0.04). The operations were mainly hemiarthroplasty in both groups. Pain scores 15 minutes after intervention and during positioning were not significantly different between the groups (Table 2). Additional fentanyl requirement and satisfaction with patient position were not significantly different between the treatment groups. Time to perform spinal block was 7.0 ± 4.2 and 6.6 ± 4.3 minutes in the FNB and fentanyl groups, respectively (P = 0.74).

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram.

Table 1.

Demographic data

| Group FNB (N = 32) | Group fentanyl (N = 32) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 65.1 ± 17.5 | 68.2 ± 12.4 | 0.42 |

| Sex (male/female) | 11/20 | 12/20 | 0.86 |

| Weight (kilograms) | 58.2 ± 9.1 | 57.6 ± 10.0 | 0.81 |

| ASA physical status I/II/III | 8/20/4 | 4/23/5 | 0.43 |

| Time from trauma to surgery (days) | 8.0 ± 7.0 | 15.6 ± 18.4 | 0.03* |

| Fracture site | 0.04* | ||

| Neck | 18 | 15 | |

| Intertrochanteric | 8 | 13 | |

| Shaft | 6 | 1 | |

| Distal part of femur | 0 | 3 | |

| Type of surgery | 0.44 | ||

| Hemiarthroplasty | 14 | 15 | |

| Dynamic hip screw | 9 | 12 | |

| Others (K-nail, etc) | 9 | 5 |

Data are expressed as mean ± SD or median (IQR) or number.

P-value < 0.05.

Table 2.

Pain scores, additional fentanyl, and satisfaction of patient position

| FNB group (n = 32) | Fentanyl group (n = 32) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pain scores 15 min after analgesia | 2.7 ± 2.6 | 3.3 ± 2.7 | 0.37 |

| Pain scores during positioning | 6.1 ± 2.6 | 5.9 ± 3.4 | 0.80 |

| Additional fentanyl requirement | 19.5 ± 16.4 | 17.1 ± 18.4 | 0.59 |

| Satisfaction of patient position | 0.49 | ||

| N o | 4 | 6 | |

| Yes | 28 | 26 |

Data are expressed as mean ±SD or median (IQR) or number.

Abbreviation: FNB, femoral nerve block.

No adverse systemic toxicity of bupivacaine, such as seizure, arrhythmia, or cardiovascular collapse was noted in the FNB group. Neither vascular puncture nor paresthesia occurred. No complications, such as hematoma, infection, or persistent paresthesia were observed within 24 hours after the operation. No patient in either group had hypoventilation (ventilatory rate <10/min) or oxygen saturation <95%.

Discussion

This prospective, randomized study shows that two doses of IV fentanyl 0.5 μg/kg with a five-minute interval between doses and FNB using 0.3% bupivacaine 30 mL can provide similar pain relief prior to positioning patients with fractured femur for spinal block. In both groups, pain scores 15 minutes after analgesia and during positioning from the supine to lateral position were not significantly different. All patients in both groups needed similar additional fentanyl to relieve pain during positioning. In this study, two doses of fentanyl 0.5 μg/kg were given with a five-minute interval between doses because most patients were elderly and likely to have had comorbid conditions. Titration of the dose of fentanyl may reduce any serious side effects, such as hypoventilation or apnea.

Over the past few years, the numbers of elderly patients who have multiple comorbidities presenting with fractured femur have been increasing. As a result, surgical repair which requires anesthesia has also increased. Urwin et al3 reported that there were marginal advantages for regional anesthesia (RA) compared with GA in terms of one-month mortality and deep vein thrombosis. Sorenson et al6 reported that the risk of deep vein thrombosis was greater for patients receiving GA. A Cochrane review2 stated that RA was associated with a decreased mortality at one month, even though this decrease was of borderline statistical significance. Furthermore, time to ambulation may be quicker in patients receiving RA.7 A national survey in the UK8 reported that the preferred anesthetic technique was RA, especially spinal block. However, the choice of anesthetic technique depends on the anesthesiologist’s preference and experience. At our institution, spinal block was used more frequently than GA for surgical repair of fractured femur. The subsequent problem concerned was pain on positioning for spinal block.

When considering the technique used to aid positioning patients for spinal block, Sandby-Thomas et al8 reported that the most frequently used agents were midazolam, ketamine, and propofol. Alternative agents were fentanyl, remifentanil, morphine, nitrous oxide, and sevoflurane, whereas nerve blocks were used infrequently. Schiferer et al9 demonstrated that FNB provided analgesia after femoral trauma which was adequate for patient transport. Other studies have described the successful use of FNB as analgesia in the emergency department.10,11 Parker et al reported that nerve blocks reduced pain score and analgesic requirements.12 However, few studies have investigated FNB to facilitate positioning during conduct of regional anesthesia. Gosavi et al assessed pain during change of position from supine to sitting after FNB with lidocaine; VAS scores were 2.7 ± 1.1.13 Sia et al4 compared IV fentanyl with FNB using lidocaine. VAS values during placement in the sitting position were lower in the FNB group (0.5 ± 0.5 versus 3.3 ± 1.4 for FNB and IV fentanyl, respectively). Mosaffa et al5 compared IV fentanyl with fascia iliaca block using lidocaine. VAS values during placement in the lateral decubitus position were lower in the fascia iliaca block group [0.5 (0–1) versus 4 (2–6) for fascia iliaca block and IV fentanyl, respectively]. In our study, we could not demonstrate any statistically difference in pain scores during change from a supine to a lateral position. Both FNB and fentanyl groups needed a similar dosage of additional fentanyl for better pain relief. Reasons for not finding any difference may be as follows:

First, a 15-minute interval before positioning may not be enough to reach the peak analgesic effect of bupivacaine. In our study, we chose this time interval for the following reasons. The time to onset of action of bupivacaine is about 15 minutes and the duration of action is about 400–450 minutes.14 Haddad et al11 also demonstrated that the analgesic benefit of FNB in extracapsular femoral neck fractures occurred at 15 minutes. For fentanyl, peak plasma concentrations occur within six to seven minutes following IV administration and the duration of action is about 30 minutes.15,16 Another reason for choosing the time frame of 15 minutes is the possible delays and backlog of cases that could occur and affect surgeons’ operating schedules if the time interval was longer. Moreover, anesthetic techniques using FNB plus spinal anesthesia are time-consuming. The real issue here is perhaps some pressure from surgeons concerning delays to surgery. However, to maximize the analgesic effect of bupivacaine, a time interval longer than 15 minutes may be chosen. Studies using nerve stimulation for three-in-one blocks with 20 mL of bupivacaine 0.5% have reported sensory onset times of 27 ± 7 minutes,17 32 ± 10 minutes,18 and 27 ± 16 minutes.19 Another method to shorten the onset time is to use lidocaine instead of bupivacaine. Sia et al4 have shown that a five-minute interval was adequate to establish the analgesic effect produced by FNB using 1.5% lidocaine. Gosavi et al13 used the mixture of 10 mL of 2% lidocaine, 1 mL of sodium bicarbonate and 4 mL of normal saline for FNB. The onset time was 5 ± 0.54 minutes.

Second, femoral fracture is very variable in its presentation because of the large large amount of bone involved. The neck of femur is most frequently fractured because it is the narrowest and weakest part of the bone.20 The quality of the analgesia depends on the fracture site; excellent relief can be obtained for midshaft fractures, good relief for lower third fractures, and partial relief for upper third fractures.21 Rosenberg et al22 stated that a lumbar plexus block or combination of femoral, lateral femoral cutaneous, and obturator nerve blocks can be useful for surgery on the proximal femur and the femoral neck. In addition, Chudinov et al23 mentioned that surgery at the proximal femur requires a motor and sensory block of the lumbar and sacral plexuses because the nerves involved are the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve of the thigh (L2/L3) laterally, the femoral nerve (L2–L4) anteriorly, the obturator (L2–L4) and genitofemoral (L1/L2) medially, and the sciatic nerve (L4–S3) posteriorly. In our study, the fracture sites were mostly at the neck of femur. FNB for fracture of the femoral neck would be unlikely to be effective, considering the innervation of this area of the bone. Our study design could have been improved has it included patients with only one type of femoral fracture or if the different types of fracture site were analysed separately rather than being grouped together.

Third, our method for assessment of analgesia was a numeric pain rating score, with use of additional analgesia as required. The numeric rating pain scale was used because it was easier for elderly patients. To clarify the results further, a comparison of change in pain scores may have been useful, but we did not record baseline pain scores in this study. We believe that pain scores on movement of a fractured leg at baseline should ideally be compared with pain scores during positioning. However, for ethical reasons, we decided not to measure baseline pain scores on movement and consider that baseline pain scores at rest would not be comparable with pain scores during positioning. Assessment of the quality of sensory block in addition to the numeric rating pain scores is now needed to determine the effectiveness of FNB in this situation. Even after a good nerve stimulation muscular response, a block deficit is possible. Therefore, sensory assessment of blockade should be performed along the femoral nerve distribution. To avoid painful stimuli and possible further displacement of fractures, motor block is no need to evaluate. Two published studies reported that the quality of the sensory block 30–60 minutes after the injection of bupivacaine was 21 ± 15%18 and 27 ± 14%19 of initial values.

Finally, the delay between trauma and surgery may have had an unpredictable effect on pain in these patients. Orosz et al24 reported that surgery performed within 24 hours of admission decreased the duration of severe or very severe preoperative pain. Nevertheless, early surgery may mean insufficient time is available for optimization of treatment for comorbid conditions.25 In our study, the time from trauma to surgery was long in both groups and particularly so in the fentanyl group, and this would have influenced our results. Reasons for delay until surgery include waiting for test results, medical stabilization, timely consultation, and availability of the surgeon or operating room. Future research should include time from trauma to surgery in the study design and patients should be randomized and stratified equally in each treatment group.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we were unable to demonstrate any difference in an analgesic benefit between FNB and IV fentanyl for patient positioning before spinal block. Further studies are required before definite conclusions can be reached. However, use of FNB can provide postoperative pain relief for patients with fractured femur. In addition, the utility of a multimodal approach (FNB + IV fentanyl) may be a possible option for pain relief during positioning. With regard to opioids, potential side effects must be considered and analgesic dosing should be titrated based on pain scores.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The author reports no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Duc TA. Postoperative pain control. In: Conroy JM, Dorman BH, editors. Anesthesia for Orthopedic Surgery. New York, NY: Raven Press; 1994. pp. 355–365. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parker MJ, Handoll HHG, Griffiths R. Anaesthesia for hip fracture surgery in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;4:CD000521. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000521.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Urwin SC, Parker MJ, Griffiths R. General versus regional anesthesia for hip fracture surgery: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. Br J Anaesth. 2000;84:450–455. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bja.a013468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sia S, Pelusio F, Barbagli R, Rivituso C. Analgesia before performing a spinal block in the sitting position in patients with femoral shaft fracture: a comparison between femoral nerve block and intravenous fentanyl. Anesth Analg. 2004;99:1221–1224. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000134812.00471.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mosaffa F, Esmaelijah A, Khoshnevis H. Analgesia before performing a spinal block in the lateral decubitus position in patients with femoral neck fracture: a comparison between fascia iliaca block and IV fentanyl (Abstract) Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2005;30(Suppl 1):61. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sorenson RM, Pace NL. Anesthetic techniques during surgical repair of femoral neck fractures. A meta-analysis. Anesthesiology. 1992;77:1095–1104. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199212000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stanley I. The anaesthetic management of upper femoral fracture. Curr Anaesth Crit Care. 2005;16:23–33. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sandby-Thomas M, Sullivan G, Hall JE. A national survey into the peri-operative anesthetic management of patients presenting for surgical correction of a fractured neck of femur. Anaesthesia. 2008;63:250–258. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2007.05328.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schiferer A, Gore C, Gorove L, et al. A randomized controlled trial of femoral nerve blockade administered preclinically for pain relief in femoral trauma. Anesth Analg. 2007;105:1852–1854. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000287676.39323.9e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fletcher AK, Rigby AS, Heyes FLP. Three-in-one femoral nerve blockade as analgesia for fractured neck of femur in the emergency department: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2003;41:227–233. doi: 10.1067/mem.2003.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haddad FS, Williams RL. Femoral nerve block in extracapsular femoral neck fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1995;77:922–923. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parker MJ, Griffiths R, Appadu BN. Nerve blocks (subcostal, lateral cutaneous, femoral, triple, psoas) for hip fractures. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;1:CD001159. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gosavi CP, Chaudhari LS, Poddar R. Use of femoral nerve block to help positioning during conduct of regional anesthesia (Abstract) [Accessed December 29, 2008]. Available from: http://www.bhj.org/journal/2001_4304_oct/org_531.htm.

- 14.Lou L, Sabar R, Kaye AD. Local anesthetics. In: Raj PP, editor. Textbook of Regional Anesthesia. New York, NY: Churchill Livingstone; 2002. p. 205. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hata TM, Moyers JR. Preoperative evaluation and management. In: Barash PG, Cullen BF, Stoelting RK, editors. Clinical Anesthesia. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006. pp. 492–493. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Benzon HT, Knight AE. Acute situations: Trauma. In: Raj PP, editor. Textbook of Regional Anesthesia. New York, NY: Churchill Livingstone; 2002. p. 508. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Urbanek B, Duma A, Kimberger O, et al. Onset time, quality of blockade, and duration of three-in-one blocks with levobupivacaine and bupivacaine. Anesth Analg. 2003;97:888–892. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000072705.86142.5D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marhofer P, Oismuller C, Faryniak B, Sitzwohl C, Mayer N, Kapral S. Three-in-one blocks with ropivacaine: evaluation of sensory onset time and quality of sensory block. Anesth Analg. 2000;90:125–128. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200001000-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marhofer P, Schriigendorfer K, Koinig H, Kapral S, Weinstabl C, Mayer N. Ultrasonographic guidance improves sensory block and onset time of three-in-one blocks. Anesth Analg. 1997;85:854–857. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199710000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moore KL, Dalley AF. Clinically Oriented Anatomy. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006. p. 566. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hartrick CT. Trauma. In: Raj PP, editor. Textbook of Regional Anesthesia. New York, NY: Churchill Livingstone; 2002. p. 897. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosenberg AD, Albert DB, Bernstein RL. Regional anesthesia for orthopedic trauma. Problem in Anesthesia. 1994;8:426. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chudinov A, Berkenstadt H, Salai M, Cahana A, Perel A. Continuous psoas compartment block for anesthesia and perioperative analgesia in patients with hip fractures. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 1999;24:563–568. doi: 10.1016/s1098-7339(99)90050-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Orosz GM, Magaziner J, Hannan EL, et al. Association of timing of surgery for hip fracture and patient outcomes. JAMA. 2004;291:1738–1743. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.14.1738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sutcliffe AJ. Anaesthesia for fractured neck of femur. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2006;7:75–77. [Google Scholar]