Abstract

The aim of this study was to explore whether single-wall carbon nanotubes (SWCNTs) can be used as artery tissue-engineering materials by promoting vascular adventitial fibroblasts (VAFs) to transform into myofibroblasts (MFs) and to find the signal pathway involved in this process. VAFs were primary cultured and incubated with various doses of SWCNTs suspension (0, 0.8, 3.2, 12.5, 50, and 200 μg/mL). In the present study, we used three methods (MTT, WST-1, and WST-8) at the same time to detect the cell viability and immunofluorescence probe technology to investigate the effects of oxidative injury after VAFs incubated with SWCNTs. Immunocytochemical staining was used to detect SM22-α expression to confirm whether VAFs transformed into MFs. The protein levels were detected by western blotting. The results of immunocytochemical staining showed that SM22-α was expressed after incubation with 50 μg/mL SWCNTs for 96 hours, but with oxidative damage. The mRNA and protein levels of SM22-α, C-Jun N-terminal kinase, TGF-β1, and TGF-β receptor II in VAFs increased with the dose of SWCNTs. The expression of the p-Smad2/3 protein was upregulated while the Smad7 protein was significantly down-regulated. Smad4 was translocated to the nucleus to regulate SM22-α gene expression. In conclusion, SWCNTs promoted VAFs to transform into MFs with SM22-α expression by the C-Jun N-terminal kinase/Smads signal pathway at the early stage (48 hours) but weakened quickly. SWCNTs also promoted the transformation by the TGF-βl/Smads signal pathway at the advanced stage in a persistent manner. These results indicate that SWCNTs can possibly be used as artery tissue-engineering materials.

Keywords: SWCNTs, VAFs, SM22-α, signal pathway, tissue-engineering materials

Introduction

Nanotechnology is the understanding and control of matter at dimensions of roughly 1 to 100 nanometers, where unique phenomena enable novel applications. The application of nanotechnology in medicine has potential in a range of treatments, including gene therapy,1 drug delivery,2 and medical devices.3 However, turning the early promise into readily available medical treatments is a lengthy process, involving the development of the products efficacy, safety, stability, manufacture, and regulation. The tissue-engineering nanomaterials, which are produced from traditional tissue-engineering materials by nanotechnology, have special biological properties and have attracted much interest. In recent years, studies on the application of nanomaterials4–12 in tissue engineering fields have been of great interest. The applications of nanophase ceramics, carbon nanotubes (CNTs), carbon nanowires, and nano metallic materials in bone and cartilage tissue engineering; titanium nanomaterials,4 poly-DL-lactide nanomaterials,5–8 and carbon nanofibers9,10 in artery tissue engineering; organic frameworks,11 nanofibrous scaffolds, and CNTs/fibers in neural tissue engineering;12 and nanostructured polymers in bladder tissue engineering have already been reported. These reports indicate that nanomaterials, especially CNTs, have potential in further applications.

The simplest type of CNT is the single-walled CNT (SWCNT) which can be thought of as a single sheet of graphite rolled up to form a seamless cylinder. The theoretical volume for discrete SWCNT has been estimated as 1300 m2/g. The large surface area provides the membrane basal body with its mechanical strength and three-dimensional structure. These properties make SWCNTs useful as artery tissue-engineering materials for neointima formation and vascular remodeling to cure thrombus. Vascular adventitial fibroblasts (VAFs) play an important role in the process of neointima formation and vascular remodeling. As the major cell type in the vascular adventitia, VAF is not a passive bystander but an active participant in response to diverse stimulations. The transition of VAFs into myofibroblasts (MFs) can traverse the ruptured media and participate in neointimal formation. Similar previous reports showed that CNTs could promote fibroblast to MF transformation.13,14 We hypothesized that SWCNTs could be used as artery tissue-engineering materials for promoting VAFs to transform into MFs on the basis of our previous work. Analyses of time-response and concentration-response effects of SWCNTs on VAFs were used to check the hypothesis and elucidate the mechanism using in vitro models.

SM22-α is a marker of cell differentiation. VAFs only exist in normal vascular adventitia. After vascular adventitial damage, VAFs differentiate into MFs, which is identified by SM22-α in the cytoplasm. Newly differentiated MFs then migrate to the endomembrane and proliferate to become cell components of the new endomembrane. The formation of MFs is closely related with numerous growth factors and cytokines, but TGF-β1 has the strongest relationship to the formation of MFs. Therefore, we hypothesized that the expression of SM22-α is regulated by the TGF-β1 signal transduction system and Smad family.

The purpose of this study was to investigate the signaling pathway involved in SWCNT-mediated transformation of VAFs and explore the molecular mechanism. We observed VAFs differentiation and morphological changes, and analyzed the effects by monitoring the expression levels of extracellular matrix proteins and other proteins that are involved in MFs differentiation, which will provide new targets for investigation to assess the bioavailability of SWCNTs in artery tissue engineering.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

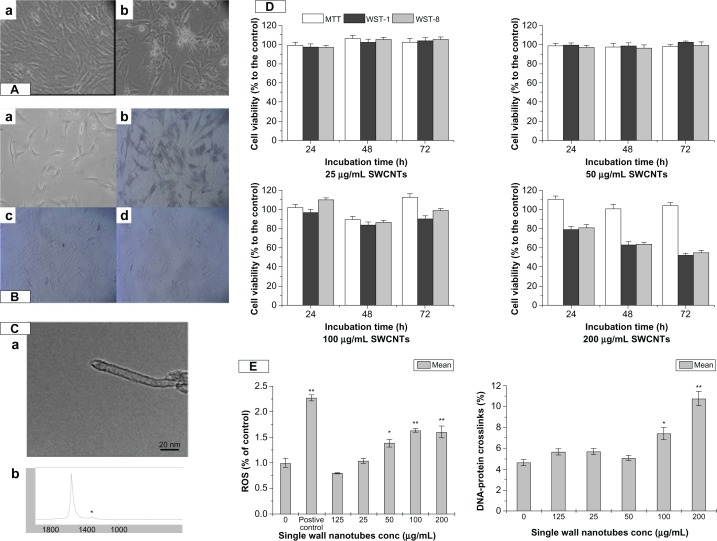

VAFs were cultured in fibroblast medium (Cell-ling, Heidelberg, Germany) consisting of M199 supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 4 mM glutamine, 100 U/mL penicillin and 0.1 mg/mL streptomycin and incubated at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. Figure 1 shows the original VAFs, as well as morphological (Figure 1A) and immunological (Figure 1B) identification.

Figure 1.

The characteristic of SWCNT and its cytotoxicity to VAFs. (A) Primary culture of rat VAFs. Morphological identification: (a) 1 day; (b) 5 days. (B) Immunological identification: (a) blank control; (b) vimentin (+); (c) desmin (−); (d) VIII F(−). (C) Particle characterization: (a) TEM of SWCNTs; (b) Raman spectra of SWCNTs. (D) Cell viability of cells incubation with SWCNTs (25, 50, 100, and 200 μg/mL) for 24, 48, and 72 hours using MTT, WST-1, and WST-8. Values are the means ± SEM of three experiments. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01 versus M199-exposed control cells. (E) Oxidative damage including DNA-protein crosslink level and ROS production of cells after incubation with SWCNTs (0, 12.5, 25, 50, 100, and 200 μg/mL) for 72 hours.

Notes: Values are the means ± SEM of three experiments. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01 versus M199-exposed control cells.

Abbreviations: VAF, vascular adventitial fibroblast; TEM, transmission electron microscopy; SWCNTs, single-wall carbon nanotubes; SEM, standard error of the mean; ROS, reactive oxygen species; MTT, 3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide; WST-1, (2-(4-Iodophenyl)-3-(4-nitrophenyl)-5-(2,4-disulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium sodium salt; WST-8, 2-(2-methoxy-4-NOxphenyl)-3-(4-NOxphenyl)-5-(2,4-methylbenzene)-2H-tetrazolim monosodium salt.

SWCNTs characteristics

SWCNTs were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO). We used a single tube with a 0.8–1.2 nm diameter and several microns in length, which was determined by TEM (JEM-2010FEF; JEOL, Tokyo, Japan) (Figure 1C[a]), and the Raman spectrum of the functional groups (RM200; Renishaw, Wotton-under-Edge, UK) is shown in Figure 1C[b]. The chemical components were 93.64% C, 1.64% O, 1.60% Ca, 0.98% Fe, 0.62% Co, 0.50% Cr, 0.41% Si, 0.37% S, and 0.25% Cl.

Dispersion of SWCNTs

To disperse SWCNTs in the culture medium, a stock concentration of 2000 μg/mL SWCNTs was prepared in the appropriate culture medium by vortexing the suspension three times for 5 seconds followed by sonication for 1 minute in an ultrasonic bath (KQ2200DE; Shumei, Jiangsu, China). This procedure was repeated three times. Working concentrations of 200 μg/mL were then prepared by dilution in culture medium.15

Cell viability assay

Nanomaterials, having a small size but large surface area, are able to absorb MTT, which can result in incorrect results. As such, we needed more than one method to detect their cell viability. MTT, WST-1, and WST-8 assays were used in our study to confirm the effect of SWCNTs on cell viability. Briefly, 5 × 103 VAFs were seeded into each well of a 96-well plate and grown overnight. Cells were treated in triplicate with the particle suspensions in concentrations of 25 μg/mL, 50 μg/mL, 100 μg/mL, 200 μg/mL, and control in complete culture medium for 24–72 hours. We then discarded the SWCNTs and washed the cells with culture medium. Then, 10 μL of MTT, WST-1, and WST-8 solution were respectively added into 100 μL of complete culture medium, which was added into each well and incubated for 4 hours at 37°C and 5% CO2. Mitochondrial dehydrogenases of viable cells reduce the yellowish water-soluble WST-1 and WST-8.

KCl-SDS assay

The KCl-SDS assay was based on methodology previously described,16 which was slightly modified in order to detect SWCNT-induced DNA–protein crosslinks (DPCs). Briefly, cells were trypsinized, resuspended, and lysed with 0.5 mL of 2% SDS solution with gentle vortexing. The lysate solution was heated to 65°C, and kept at this temperature for 10 minutes. Then, 0.1 mL of 10 mMTris–HCl (pH 7.4) containing 2.5 M KCl was added. Samples were kept on ice for 5 minutes, and then centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 5 minutes. The supernatants containing the unbound fraction of DNA were collected into differently labeled tubes. Pellets (containing DPC) were washed with PBS, heated at 65°C for 10 minutes, chilled on ice for 5 minutes, and centrifuged, as described above. Subsequent supernatants following each wash were added with unbound fractions of DNA. The final pellet was resuspended in 1 mL proteinase K solution (0.2 mg/mL soluble in a wash buffer) and digested for 3 hours at 50°C. The resultant mixture was centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 10 minutes, and the supernatant was collected. Supernatants containing DNA were stained via the fluorescent dye, Hoechst 33258, for 30 minutes in the dark. Fluorescence was measured using a fluorescence multi-well plate reader (VarioskanFlash; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) at 350/450 nm. Sample DNA contents were quantified relative to a corresponding DNA standard curve generated from calf thymus DNA. The DPC coefficient was measured as a ratio of the percentage of the DNA involved in DPC over the percentage of the DNA involved in DPC plus the unbound fraction of DNA.

Determination of reactive oxygen species (ROS) production

ROS production was evaluated on a fluorescence multi-well plate reader with an oxidation-sensitive fluorescent dye, DCFH-DA, as previously described.17,18 Briefly, 1 × 106 cells were suspended in phosphate-buffered solution (PBS) and incubated with 10 μM DCF-DA at 37°C for 30 minutes following incubation with a different dose of SWCNTs for 72 hours. The hydrolysis of DCF-DA into dichlorodihydro fluorescein via nonspecific cellular esterases, and subsequent oxidation via peroxides, produced the fluorescence signal. Fluorescence was recorded and monitored at 488 nm (excitation)/525 nm (emission) on a fluorescence multi-well plate reader (VarioskanFlash). Data were expressed as the fluorescence of the sample relative to the control. Fluorescence images were examined via fluorescence microscopy (Leica Microsystems GmbH, Wetzlar, Germany) at 100× magnification.

Immunocytochemical staining

Immunocytochemical staining was performed on rat adventitial fibroblasts after SWCNT exposure. Samples were fixed in methanol for 20 minutes, PBS-washed, and permeated with 0.2% Triton X-100 for 5 minutes at room temperature. Then, samples were incubated with 1% normal bovine serum in PBS for 1 hour. Samples were then incubated with primary antibodies, rabbit anti-SM22-α IgG (1:2000), PBS-washed, and incubated with FITC-conjugated sheep anti-rabbit-antibodies (1:160). DNA was counter stained with 4,6-diamidino-phenylindole (0.4 μg/mL). Samples were mounted on N-propyl/gallate/glycerol and examined under a fluorescence microscope (Leica Microsystems). All reagents and antibodies were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

Western blotting

Total and nuclear protein extracts were prepared in lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 2 mM PMSF, 10 ng/mL leupeptin, and 10 μg/mL aprotinin). Protein extracts (40 μg) were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred onto a polyvinylidenedifluoride membrane (PALL, Port Washington, NY). Membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat milk (Sigma-Aldrich), washed and probed with the following primary antibodies: rabbit anti-rat SM22-α, TGF-β1, pSmad2/3, Smad7 and Smad4 (1:500, Santa Cruz, CA) and β-actin (1:1000; Proteintech Group, Chicago, IL). After washing, membranes were incubated with a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1:10,000; Sigma-Aldrich) for 2 hours. Then, membranes were washed and developed using an enhanced chemiluminescence kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Tiangen Biotech, Beijing, China). Western blot assays were repeated at least three times.

Cell ultrastructure changes assessment by TEM

After incubation with 100 μg/mL SWCNTs for 24 hours and 48 hours, cells were observed by TEM. Briefly, VAFs were plated in complete medium (M199) overnight with and without 100 μg/mL SWCNTs. After 12 and 20 hours of incubation at 37°C with 5% CO2, cells were detached from the plates with trypsin and pelleted by centrifugation for 6 minutes at 500 g. The supernatant was removed and cell pellets were fixed for 2 hours at 4°C in a mixture of 2% paraformaldehyde and 2% glutaraldehyde in 0.05 M cacodylate buffer (pH 7.3), postfixed in 1% osmium tetroxide for 1 hour at room temperature, dehydrated in ethanol, and embedded in Epon-Araldite. Thin sections were counter stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate for observation. Each experiment was repeated at least three times.

Statistical evaluation

t-Tests were conducted to analyze the experimental data using Origin 8.0 statistical software (OriginLab, Northampton, MA).

Results

Effect of SWCNTs on cell viability

The MTT, WST-1, and WST-8 assays demonstrated no significant concentration-dependent decrease in VAFs viability following incubation with SWCNTs suspension (25, 50, 100, and 200 μg/mL) for 24, 48, and 72 hours, respectively, as in Figure 1D. Compared to low-dose groups, at the concentration of 200 μg/mL SWCNTs incubation for the same time, the cell viability decreased but was not significantly different (P > 0.05).

Oxidative damage

To investigate the DNA-protein damage, a KCl-sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) assay was performed. As in Figure 1E, after incubation with different concentrations of SWCNTs for 72 hours, compared to the control, the increase of the DPCs was not significantly different at the SWCNTs concentrations of 12.5, 25, and 50 μg/mL (P > 0.05) and the increase of DPCs was significantly different at the SWCNTs concentration of 100 μg/mL and 200 μg/mL (P < 0.05 and P < 0.01), which indicated that SWCNTs could lead to VAFs DPCs.

Compared to the control group, ROS generation of the 50 μg/mL group was significantly different (P < 0.05), as the concentration of SWCNTs increased to 100 μg/mL and 200 μg/mL, the ROS generation increased (P < 0.01).

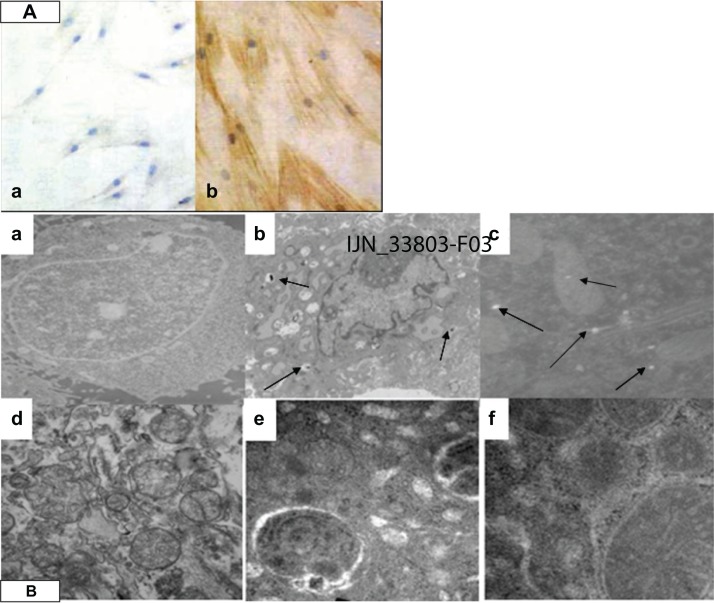

Immunostaining assays

Figure 2A[a] shows normal cells that were visualized by phase contrast microscopy and appeared spread and flat. SM22-α showed a negative distribution. However, cells incubated with 50 μg/mL of SWCNTs for 96 hours showed positive SM22-α protein expression (Figure 2A[b]).

Figure 2.

The immunocytochemical staining and cell ultrastructure changes assessment by TEM. (A) SWCNTs promoted VAFs transformed into MFs and immunohistochemistry of the SM22-α related antigen. VAFs culture with SWCNT-free medium (a); VAFs transformed into MFs after incubation with 50 μg/mL SWCNTs for 96 hours, MFs depicted by brown staining (b). (B) Ultrastructure of rat VAFs observed by TEM: (a) typical normal cell (12,000×); (b and c) cell incubation with SWCNTs (50 μg/mL; 20 hours, 12,000×): observed shrinkage of the nucleus membrane and swelling of mitochondria; (d) typical normal cell (70,000×); (e and f) cells incubation with SWCNTs (70,000×): observed swelling of mitochondria with cristae decreasing or even disappearing, some mitochondrial transformation into little vacuoles; swelling of endoplasmic reticulum with ribosome (fine black particles) threshing; (e) observed phagocytosis phenomenon (70,000×).

Note: The arrows are SWCNT particles that entered into cells.

Abbreviations: VAF, vascular adventitial fibroblast; TEM, transmission electron microscopy; SWCNTs, single-wall carbon nanotubes; MF, myofibroblast.

Effects of SWCNTs on cell ultrastructure

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) revealed the cellular localization of SWCNTs, as shown in Figures 1C and 2B(a)–(d). The cell membranes of normal cells exhibited regular contours and a distinct contrast against a moderately stained cytoplasm. In contrast, cells incubated with SWCNTs showed ruffles on their cell membranes, and the cell shape appeared rounded compared with that of normal cells. As shown in Figure 2B[b], aggregated SWCNTs were observed within the cells. After incubation with 100 μg/mL of SWCNTs for 24 and 48 hours, swelling of the nuclear membrane and mitochondrial damage occurred (Figure 2B[c]) with vacuolar cellular appearance (Figure 2B[f]).

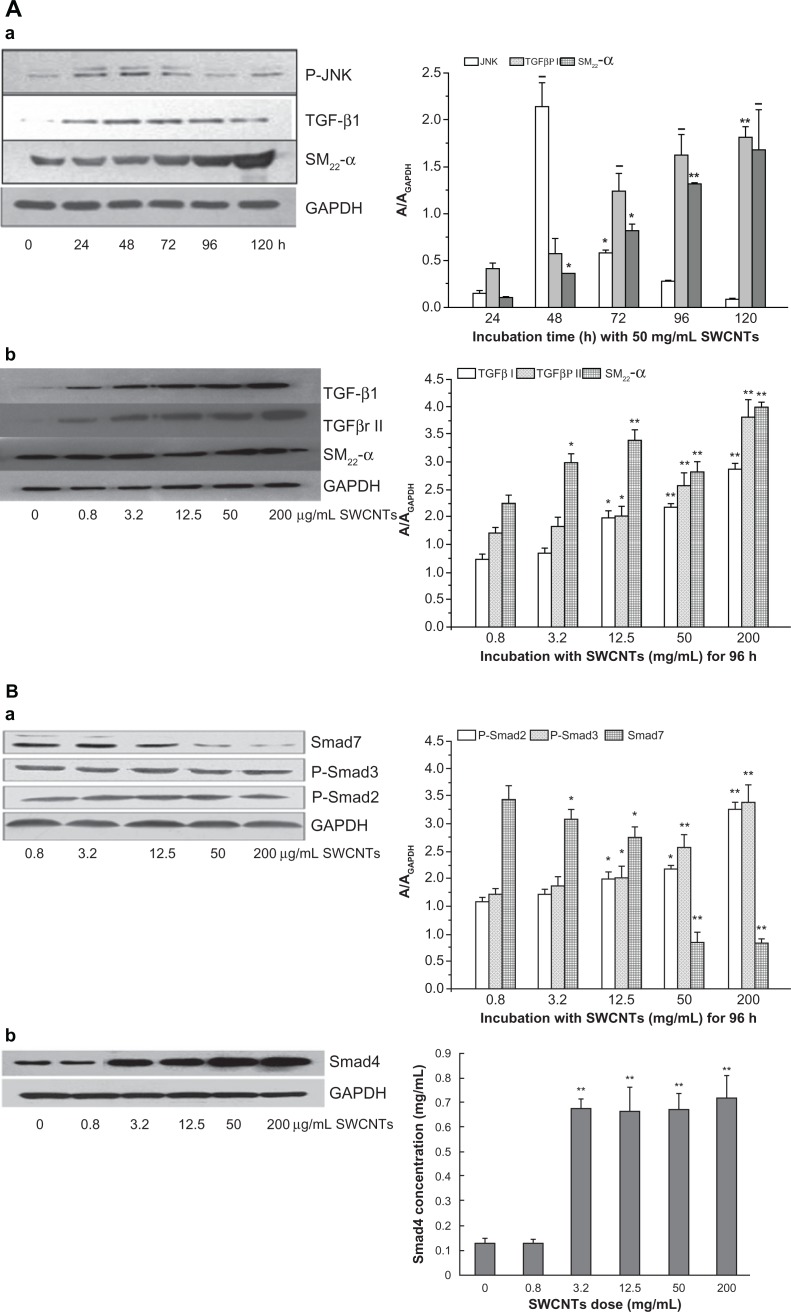

C-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK)/TGFβ1-Smads signal pathway

To approach the molecular mechanism of VAF transformation into MFs promoted by SWCNTs, we measured the relative signal pathway involved in SM22-α expression by Western blotting as shown in Figure 3. Incubated with 50 μg/mL of SWCNTs for 48 hours, the protein of JNK was expressed at high level (P < 0.01) compared to 24 hours but weakened quickly. Under incubation with the same dose of SWCNTs for 72 to 120 hours, the TGF-β1 protein was up-expressed (P < 0.01) (Figure 3A[a]). Under incubation with different doses of SWCNTs for 96 hours, the protein levels of TGFβ1, TGFβRII, and SM22-α were all obviously increasing with the SWCNTs dose (Figure 3A[b]). Compared to the control group, p-Smad2 and p-Smad3 protein levels were both significantly increased after incubation with greater than 12.5 μg/mL SWCNTs for 96 hours, while Smad7 decreased from 3.2 in 200 μg/mL of SWCNTs (P < 0.05 and P < 0.01) (Figure 3B[a]) and Smad4 translocated to the nucleus to induce SM22-α gene transcription (Figure 3B[b]).

Figure 3.

The signal pathway of SM22-α protein expression. (A) Effects of SWCNT incubation with VAFs on JNK, TGF-β1, TGF-β receptor II, and SM22-α protein expression as determined by western blotting. (a) Protein levels of JNK, TGF-β1, and SM22-α after cells incubation with 50 μg/mL SWCNTs for different times. (b) Protein levels of TGF-β1, TGF-β receptor II, and SM22-α after cells incubation with various concentrations of SWCNTs for 96 hours. Protein levels were measured as described in the Materials and methods section. Control cells were cultured in SWCNT-free medium. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01). (B) Effects of SWCNT incubation with VAFs on pSmad2/3, Smad7, and Smad4 protein expression as determined by western blotting. (a) Protein levels of pSmad2/3, Smad7 after cells incubated with various concentrations of SWCNTs for 96 hours. (b) Protein levels of Smad4 translocated into nucleus after cell incubation with different dose of SWCNTs for 96 hours.

Notes: Protein levels were measured as described in the Materials and methods section. Control cells were cultured in SWCNT-free medium. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM of three independent experiments (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01).

Abbreviations: SWCNTs, single-wall carbon nanotubes; VAF, vascular adventitial fibroblast; JNK, C-Jun N-terminal kinases; SEM, standard error of the mean.

Discussion

SM22-α is a marker gene of MFs, which encodes a 22 kDa contraction-associated protein. The SM22-α gene is characterized by a simple structure and restricted expression in differentiated MFs. Thus, SM22-α has been widely used to study the regulatory mechanisms of MF-specific gene expression. Our immunocytochemical study showed that SM22-α was expressed after incubation with SWCNTs, which indicated that VAFs transformed into MFs.

We used a cell viability assay to assess SWCNTs’ biosafety as artery engineering materials. The results showed that SWCNTs had no effect onVAFs at low doses (less than 100 μg/mL), but at the concentration of 200 μg/mL, there was some loss of cell viability. The present result correlates well with the observation of increased ROS generation. Previous reports using various nanomaterials differing in size reflected that SWCNTs can induce significant ROS generation and influence cell viability. Further, loss of cell viability was shown to be due to apoptosis and necrosis by MWCNTs; however, the precise mechanism has yet to be worked out.13,14 SWCNTs have been reported to interact with various dyes commonly used to assess cytotoxicity, such as Coomassie blue and Alamar blue.13,14 On the other hand, some studies reported that SWCNTs appeared to interact with some tetrazolium salts such as MTT, but not with water-soluble tetrazolium salts such as WST-8, XTT, or INT. Other authors reported that the binding of MTT-formazan to CNT material was found to be negligible and not to influence the results.19 Thus, we used three methods at the same time to confirm cell viability. The results of the three methods all showed that there is no obvious cytotoxicity for doses of SWCNTs less than 100 μg/mL.

Following 72 hours of cell incubation with SWCNTs, ROS generation was significantly increased, even at a concentration of 50 μg/mL. Furthermore, with increasing concentrations of SWCNTs, ROS generation also increased. Meanwhile, a cellular response to oxidative stress was triggered. JNKs, also referred to as stress-activated kinases (SAPKs), constitute a subfamily of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) superfamily. Oxidative damage induced by a variety of extracellular stimuli (such as stress) is mediated by JNK. Seventy-two hours after incubation with 100 μg/mL of SWCNTs, the number of DPCs significantly increased, binding to the results of JNK high expression at 48 hours after incubation with 50 μg/mL of SWCNTs, indicating that the JNK signal pathway is involved in oxidative damage and the increase in ROS-induced DNA damage.

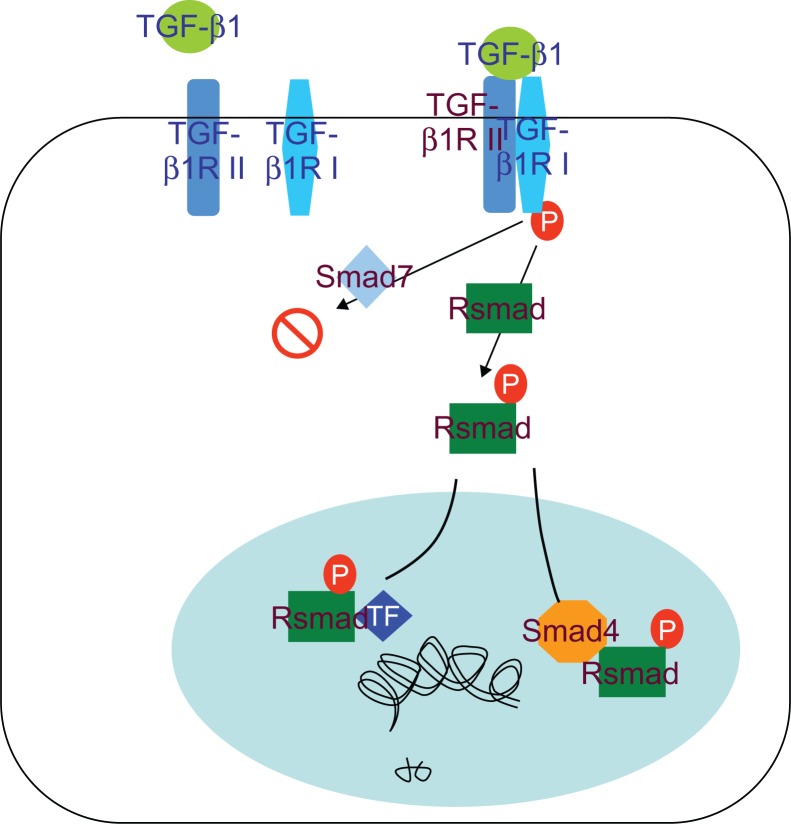

Our results indicated that TGF-β1 is a multifunctional cytokine, which plays an important role in reparation of tissue damage by enhancing extracellular matrix production and fibroblast proliferation. The TGF-β receptor signaling system is important for regulating differentiation. TGF-β is upregulated by Smad family proteins and the canonical TGF-β signaling pathway involves TGF-β type II/I receptor-mediated phosphorylation of Smad2/3 that dimerizes with Smad4 and translocates to the nucleus to induce SM22-α gene transcription (Figure 4). Abnormalities of TGF-β and/or TGF-β receptor expression and mutation of the related genes have been reported in humans and animals. These changes were considered to interrupt TGF-β signaling to the nucleus, resulting in uncontrolled proliferation of the involved cells. Smad2 and Smad3 are important proteins that are involved in TGF-β expression by positive regulation after their phosphorylation. Upon phosphorylation, Smad4 translocates to the nucleus to transcribe the SM22-α gene, but Smad7 inhibits TGF-β gene expression. Here, we investigated the role of the TGF-β receptor and its downstream Smad signaling components that regulate SM22-α expression in response to SWCNT induction of VAF differentiation into MFs. In support of other studies of the brain20,21 and lung endothelial cells,22,23 activation of the TGF-β receptor pathway was confirmed in our study that showed activation of the canonical Smad signaling pathway by an increase in Smad2/3 phosphorylation and decreased Smad7 levels. Our results showed that JNK was highly expressed instantly at an earlier stage (incubation with SWCNTs for 48 hours) but TGF-β1 expressed in both time-dependent and concentration-dependent manners which indicated that TGF-β1/Smads was the main signal pathway to modulate differentiation of VAFs into MFs induced by SWCNTs.

Figure 4.

TGF-β/Smad signal pathway.

All the results showed that SWCNTs can be used securely for artery tissue engineering at low doses of less than 50 μg/mL.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by The National Natural Science Foundation of China (No 20907075) and The National “973” plan of China (No 2010CB933904).

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Wu Y, Phillips JA, Liu H, Yang R, Tan W. Carbon nanotubes protect DNA strands during cellular delivery. ACS Nano. 2008;2(10):2023–2028. doi: 10.1021/nn800325a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang X, Meng L, Lu Q, Fei Z, Dyson PJ. Targeted delivery and controlled release of doxorubicin to cancer cells using modified single wall carbon nanotubes. Biomaterials. 2009;30(30):6041–6047. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bussy C, Cambedouzou J, Lanone S, et al. Carbon nanotubes in macrophages: imaging and chemical analysis by X-ray fluorescence microscopy. Nano Lett. 2008;8(9):2659–2663. doi: 10.1021/nl800914m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Choudhary S, Quin MB, Sanders MA, Johnson ET, Schmidt-Dannert C. Engineered protein nano-compartments for targeted enzyme localization. PLoS One. 2012;7(3):e33342. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miller DC, Thapa A, Haberstroh KM, Webster TJ. Endothelial and vascular smooth muscle cell function on poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) with nano-structured surface features. Biomaterials. 2004;25(1):53–61. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(03)00471-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miller DC, Haberstroh KM, Webster TJ. Mechanism(s) of increased vascular cell adhesion on nanostructured poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) films. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2005;73(4):476–484. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miller DC, Haberstroh KM, Webster TJ. PLGA nanometer surface features manipulate fibronectin interactions for improved vascular cell adhesion. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2007;81(3):678–684. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee SJ, Yoo JJ, Lim GJ, Atala A, Stitzel J. In vitro evaluation of electrospun nanofiber scaffolds for vascular graft application. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2007;83(4):999–1008. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xu CY, Inai R, Kotaki M, Ramakrishna S. Aligned biodegradable nanofibrous structure: a potential scaffold for blood vessel engineering. Biomaterials. 2004;25(5):877–886. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(03)00593-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Genové E, Shen C, Zhang S, Semino CE. The effect of functionalized self-assembling peptide scaffolds on human aortic endothelial cell function. Biomaterials. 2005;26(16):3341–3345. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ehrlich H, Koutsoukos PG, Demadis KD, Pokrovsky OS. Principles of demineralization: modern strategies for the isolation of organic frameworks. Part I. Common definitions and history. Micron. 2008;39(8):1062–1091. doi: 10.1016/j.micron.2008.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harrington DA, Cheng EY, Guler MO, et al. Branched peptide-amphiphiles as self-assembling coatings for tissue engineering scaffolds. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2006;78(1):157–167. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.He X, Young SH, Schwegler-Berry D, Chisholm WP, Fernback JE, Ma Q. Multiwalled carbon nanotubes induce a fibrogenic response by stimulating reactive oxygen species production, activating NF-κB signaling, and promoting fibroblast-to-myofibroblast transformation. Chem Res Toxicol. 2011;24(12):2237–2248. doi: 10.1021/tx200351d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang Y, Mu Q, Zhou H, et al. Binding of carbon nanotube to BMP receptor 2 enhances cell differentiation and inhibits apoptosis via regulating bHLH transcription factors. Cell Death Dis. 2012;3:e308. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2012.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Herzog E, Byrne HJ, Davoren M, Casey A, Duschl A, Oostingh GJ. Dispersion medium modulates oxidative stress response of human lung epithelial cells upon exposure to carbon nanomaterial samples. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2009;236(3):276–281. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2009.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu Y, Li CM, Lu Z, Ding S, Yang X, Mo J. Studies on formation and repair of formaldehyde-damaged DNA by detection of DNA-protein crosslinks and DNA breaks. Front Biosci. 2006;11:991–997. doi: 10.2741/1856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hsin YH, Chen CF, Huang S, Shih TS, Lai PS, Chueh PJ. The apoptotic effect of nanosilver is mediated by a ROS-and JNK-dependent mechanism involving the mitochondrial pathway in NIH3T3 cells. Toxicology Lett. 2008;179(3):130–139. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2008.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang Z, Zhang Y, Yang Y, et al. Pharmacological and toxicological target organelles and safe use of single-walled carbon nanotubes as drug carriers in treating Alzheimer disease. Nanomedicine. 2010;6(3):427–441. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wick P, Manser P, Limbach LK, et al. The degree and kind of agglomeration affect carbon nanotube cytotoxicity. Toxicology Lett. 2007;168(2):121–131. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2006.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lu W, Tan YZ, Hu KL, Jiang XG. Cationic albumin conjugated pegylated nanoparticle with its transcytosis ability and little toxicity against blood-brain barrier. Int J Pharm. 2005;295(1–2):247–260. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2005.01.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tin-Tin-Win-Shwe, Yamamoto S, Ahmed S, et al. Brain cytokine and chemokine mRNA expression in mice induced by intranasal instillation with ultrafine carbon black. Toxicology Lett. 2006;163(2):153–160. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2005.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rotoli BM, Bussolati O, Bianchi MG, et al. Non-functionalized multi-walled carbon nanotubes alter the paracellular permeability of human airway epithelial cells. Toxicology Lett. 2008;178(2):95–102. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2008.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alazzam A, Mfoumou E, Stiharu I, et al. Identification of deregulated genes by single wall carbon-nanotubes in human normal bronchial epithelial cells. Nanomedicine. 2010;6(4):563–569. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2009.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]