Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Growing numbers of critically ill patients require prolonged mechanical ventilation and experience difficulty with weaning. Specialized centres may facilitate weaning through focused interprofessional expertise with an emphasis on rehabilitation.

OBJECTIVE:

To characterize the population of a specialized prolonged-ventilation weaning centre (PWC) in Ontario, and to report weaning, mobility, discharge and survival outcomes.

METHODS:

Data from consecutively admitted patients were retrospectively extracted from electronic and paper medical records by research staff and verified by the primary investigator.

RESULTS:

From January 2004 to March 2011, 144 patients were admitted: 115 (80%) required ventilator weaning, and 29 (20%) required tracheostomy weaning or noninvasive ventilation. Intensive care unit length of stay before admission was a median 51 days (interquartile range [IQR] 35 to 86 days). Of the patients admitted for ventilator weaning, 76 of 115 (66% [95% CI 55% to 75%]) achieved a 24 h tracheostomy mask trial in a median of 15 days (IQR eight to 25 days). Weaning success, defined as no further ventilation for seven consecutive days, was achieved by 61 patients (53% [95% CI 44% to 62%]) in a median duration of 62 days (IQR 46 to 95 days) of ventilation, and 14 days (IQR nine to 29 days) after PWC admission. Seventeen patients died during admission. Of the 91 patients discharged from the PWC for one year, 43 (47.3% [95% CI 37.3% to 57.4%]) survived; of the 78 discharged for two years, 27 (34.6% [95% CI 25.0% to 45.7%]) were alive; of the 53 discharged for three years, 19 (35.9% [95% CI 24.3% to 49.3%]) were alive; and seven of 22 (31.8% [95% CI 16.4% to 52.7%]) survived to five years.

CONCLUSIONS:

Weaning success was moderate despite a prolonged intensive care unit stay before admission, but was comparable with studies reporting weaning outcomes from centres in other countries. Few patients survived to five years.

Keywords: Critical care; Long-term mechanical ventilation; Mechanical ventilator weaning; Prolonged mechanical ventilation; Respiration, artificial

Abstract

HISTORIQUE :

Un nombre croissant de patients gravement malades a besoin de ventilation mécanique prolongée et éprouve des problèmes de sevrage. Les centres spécialisés peuvent faciliter le sevrage par des compétences interdisciplinaires ciblées axées sur la réadaptation.

OBJECTIF :

Caractériser la population d’un centre spécialisé de sevrage de la ventilation prolongée (CSVP) en Ontario, et rendre compte des résultats sur le plan du sevrage, de la mobilité, du congé et de la survie.

MÉTHODOLOGIE :

Le personnel de recherche a procédé à l’extraction rétrospective de données provenant de patients hospitalisés consécutifs à partir de leur dossier médical électronique et papier. L’investigateur principal a vérifié ces données.

RÉSULTATS :

De janvier 2004 à mars 2011, 144 patients ont été admis : 115 (80 %) avaient besoin d’un sevrage de la ventilation et 29 (20 %), d’un sevrage de la trachéotomie ou d’une ventilation non effractive. La durée du séjour à l’unité de soins intensifs avant l’admission correspondait à une médiane de 51 jours (plage interquartile [PIQ] de 35 à 86 jours). Parmi les 115 patients admis pour le sevrage de la ventilation, 76 (66 %[95 % IC 55 % à 75 %]) sont parvenus à un essai de masque de trachéotomie pendant 24 heures en une période médiane de 15 jours (PIQ de huit à 25 jours). La réussite du sevrage, définie par l’absence de ventilation pendant sept jours consécutifs, s’est observée auprès de 61 patients (53 % [95 % IC 44 % à 62 %]) pendant une durée moyenne de 62 jours (PIQ de 46 à 95 jours), 14 jours (PIQ de neuf à 29 jours) après l’admission au CSVP. Dix-sept patients sont décédés pendant l’admission. Des 91 patients ayant obtenu leur congé du CSVP pendant un an, 43 (47,3 % [95 % IC 37,3 % à 57,4 %]) ont survécu. Des 78 ayant obtenu leur congé pendant deux ans, 27 (34,6 % [95 % IC 25,0 % à 45,7 %]) étaient encore vivants. Des 53 ayant obtenu leur congé pendant trois ans, 19 (35,9 % [95 % IC 24,3 % à 49,3 %]) étaient encore vivants. Sept des 22 patients (31,8 % [95 % IC 16,4 % à 52,7 %]) avaient survécu au bout de cinq ans.

CONCLUSIONS :

La réussite du sevrage était modérée malgré un séjour prolongé à l’unité de soins intensifs avant l’admission, mais comparable aux études rendant compte des résultats du sevrage dans des centres d’autres pays. Peu de patients ont survécu cinq ans.

Patients with chronic lung and cardiac disease, ventilatory failure due to degenerative muscular disease and acute respiratory failure associated with critical illness may require mechanical ventilation for weeks or longer, and present greater difficulties in weaning from ventilator support (1). Approximately 5% to 10% of critically ill, ventilated adults will receive prolonged mechanical ventilation (PMV), defined as invasive ventilation >6 h/day for ≥21 days (2–4). Mortality increases as the duration of ventilation extends (5) and extubation is delayed (6). Various international studies describe organizational models and outcomes for patients experiencing PMV (7–9), although these models differ in organizational structure and among the health care systems in which they function.

Specialized weaning facilities are one organizational model proposed to facilitate efficacious weaning to decrease intensive care unit (ICU) costs, reduce long-term ventilator dependency, increase survival and improve health-related quality of life (1,8). Potential benefits to patients and the health care system are the result of a shift in focus from acute to rehabilitative care, dedicated inter-professional specialized expertise, different environmental design features, and more cost-effective and appropriate nurse-to-patient ratios. In 2004, Toronto East General Hospital (TEGH), located in Toronto, Ontario, opened a four-bed prolonged-ventilation weaning centre (PWC) later designated in 2007 as the Provincial Centre of Weaning Excellence, and expanded to eight beds by the Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care as part of the Critical Care Transformation Strategy (10). The objective of the present study was to characterize the population of this Canadian provincial specialized weaning centre, and to report weaning and mobility outcomes. A secondary objective was to determine patient survival up to five years after discharge from the PWC.

METHODS

Study design, setting and population

The present retrospective observational study included all patients admitted to and discharged from the PWC from its inception in January 2004, to March 2011. The PWC accepts referrals from any ICU in Ontario, but mostly from the Greater Toronto Area and Southern Ontario. Admission eligibility includes medically stable adult patients ventilated for ≥21 days in an ICU, and considered to be ‘weanable’ within 90 days by both the referring and accepting clinical teams. Medical stability is defined as no clinically significant hypotension, no requirement for vasopressors or inotropes, no recent onset complex arrhythmias or acute coronary syndrome, stable renal function and acid-base balance (no requirement for renal replacement therapy) and, if applicable, infective processes (sepsis, ventilator associated pneumonia) treated and controlled. Applicants must have acceptable oxygenation on either assist control or pressure support ventilation with a positive end expiratory pressure ≤8 cmH2O and a fraction of inspired oxygen <0.5. Additionally, the patient must be able to participate in care decisions; have a tracheostomy in situ; have adequate nutritional support established; and advanced care planning including advanced directives discussed and documented in the medical record. The PWC program does not accept patients with clearly irreversible disease such as high spinal cord injury, progressive neuromuscular disease or advanced dementia. During the study period, the PWC also accepted some referrals for patients no longer ventilated but requiring tracheostomy weaning or stabilization on noninvasive ventilation (NIV).

The interprofessional PWC program comprises individualized weaning and mobilization treatment plans: communication and swallowing, occupational therapy, dietetic, psychiatric and social work assessment; and, if required, palliative, pain and wound care consultation. Generally, the registered nurse-to-patient ratio is 1:2 but may vary depending on patient care needs. Registered respiratory therapist (RT) presence in the PWC is now 24 h, although during the period from 2004 to 2009, RT presence ended at 23:00. A full-time physiotherapist is assigned to the PWC patients. Four respirologists work a four-week rotating roster that provides seven days/week coverage. Weaning comprises pressure support (PS) reduction by 2 cmH2O/day until PS of 8 cmH2O is tolerated. Patients then commence daily tracheostomy mask (TM) trials that progressively extend in duration, with periods of nonfatiguing ventilatory support between trials. Patients are discharged from the PWC program when successfully weaned and decannulated if able. Policy dictates that patients who do not wean from ventilation within 90 days should be repatriated to the referring institution, although this does not always occur within this time frame. Patients who experience acute deterioration requiring ICU-level care are also transferred, either to the ICU at TEGH or the referring institution.

Data collection

Before data collection, the study was approved by the Research Ethics Board of TEGH who, due to the observational nature of the study, waived the need for informed consent. Data collection elements were selected from those previously published in a multicentre study of ventilator-dependent patients admitted to long-term acute care hospitals in the United States (US) (11). The multicentre study coordinating site was contacted via e-mail and received copies of case report forms and data definitions. Items were modified and added based on feedback from the interprofessional team leaders as well as a review of other relevant published literature. Data on consecutively admitted patients were extracted from the electronic and paper medical record by research staff and verified by the primary investigator (LR). The following baseline demographics were recorded: premorbid functional status (Zubrod score); duration of mechanical ventilation and ICU stay before admission; timing of tracheostomy, pre-existing comorbid conditions; events leading to ventilator dependence; vital signs and worst (furthest from normal) laboratory values during the first 24 h of admission to the PWC; procedures and complications experienced during PWC stay; as well as weaning, mobility, and discharge outcomes and functional status on discharge (Zubrod score). Weaning success was defined as no further requirement for positive pressure ventilation (invasive or noninvasive) for seven consecutive days. Tracheostomy tube decannulation was not a prerequisite for weaning success. The Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II score (12) was calculated using variables measured in the first 24 h of PWC admission and the age-adjusted Charlson comorbidity index (13). Vital status following PWC discharge was determined by reviewing medical records of subsequent admissions and outpatient appointments at the hospital, contacting family doctors and undertaking patient recruitment methods (letter and telephone contact) for a separate study of health-related quality of life for PWC survivors.

Statistical methods

Continuous variables (age, number of premorbid conditions, APACHE II and Charlson scores) were summarized using means and SDs, or medians and interquartile ranges (IQR) depending on the data distribution, while categorical variables (indications for PMV, premorbid locations, weaning outcomes and discharge destinations) were summarized using proportions and their 95% CIs and compared using χ2 or Fisher exact tests depending on cell size. Data distribution of continuous variables was checked using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. The median time-to-PWC discharge were calculated using time-to-event methods (survival analysis), which accounts for censoring due to death for patients experiencing infectious complications versus no infectious complications. No assumptions were made regarding missing data. All analyses were performed using SPSS version 18.0 (IBM Corporation, USA).

RESULTS

In the seven-year, three-month study period, 144 patients were admitted: 115 (79.9% [95% CI 73.3% to 86.4%]) required ventilator weaning, 18 (12.5% [95% CI 7.1% to 17.9%]) for tracheostomy weaning, nine (6.3% [95% CI 2.3% to 10.2%]) for NIV weaning following PMV and two (1.4% [0% to 3.3%]) patients required stabilization on NIV without previous invasive ventilation. Most patients (n=84, 58.3%, [95% CI 50.3% to 66.4%]) were referred from ICUs in other hospitals and the remainder from the hospital’s own ICU. Patients requiring tracheostomy and NIV weaning were admitted to the PWC due to the inability of other medical units to provide these interventions. Patient demographic characteristics for the 115 patients admitted for ventilator weaning are shown in Table 1. The median ICU length of stay (LOS) before PWC admission was 56 days (IQR 39 to 90 days). The median time from intubation to tracheostomy (recorded for 103 patients) was 17 days (IQR 10 to 24 days). Medical diagnoses and surgical procedures resulting in PMV are shown in Table 2. The majority of patients experienced at least one episode of ventilator-associated pneumonia before PWC admission that contributed to PMV.

TABLE 1.

Demographic characteristics

| Characteristic | Ventilator weaning (n=115) |

|---|---|

| Age, years, median (IQR) | 70 (59–77) |

| Male sex | 58 (50.4) |

| ICU admission category* | |

| Medical | 72 (62.6) |

| Surgical (elective) | 32 (27.8) |

| Surgical (emergency) | 7 (6.1) |

| Trauma | 4 (3.5) |

| Primary reason for PMV | |

| Respiratory† | 75 (65.2) |

| Nonrespiratory‡ | 40 (34.8) |

| Premorbid location | |

| Home | 109 (94.8) |

| Assisted living | 1 (0.9) |

| Nursing home | 4 (3.5) |

| Rehabilitation | 1 (0.9) |

| Premorbid conditions, median (IQR) | 3 (2–4) |

| Hypertension | 51 (44.3) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 51 (44.3) |

| Coronary artery disease | 34 (29.6) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 32 (27.8) |

| Atrial arrhythmias | 32 (27.8) |

| Duration of ICU admission§, days, median (IQR) | 56 (39–90) |

| Duration of invasive ventilation§, days, median (IQR) | 55 (37–89) |

| Intubation to tracheostomy§, days, median (IQR) | 17 (10–24) |

| APACHE II score¶, mean ± SD | 11±4.1 |

| Age-adjusted Charlson comorbidity index, mean ± SD | 4±2.7 |

Data presented as n (%) unless otherwise indicated.

Admission category before prolonged-ventilation weaning centre admission;

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbation (30 infective and 11 noninfective), pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome, status asthmaticus;

Neuromuscular disease, sepsis, diaphragm paralysis, congestive heart failure, botulism paralysis, central hypoventilation syndrome, gastrointestinal surgery, Still’s disease, obstructive sleep apnea, thymus resection, kyphoscoliosis;

Before prolonged-ventilation weaning centre (PWC) admission;

Calculated from variables recorded in the first 24 h of PWC admission. APACHE Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II; ICU Intensive care unit; IQR Interquartile range

TABLE 2.

Medical diagnoses and surgical procedures resulting in prolonged mechanical ventilation (PMV)

| Ventilator weaning (n=115) | |

|---|---|

| Surgical procedure contributed to PMV | 41 (35.7) |

| Gastrointestinal surgery, non-neoplasm | 13 (11.3) |

| Lung resection, for neoplasm | 6 (5.2) |

| Orthopedic surgery | 6 (5.2) |

| Abdominal aortic aneurysm | 4 (3.5) |

| Gastrointestinal surgery, for neoplasm | 5 (4.3) |

| Peripheral artery bypass graft | 2 (1.7) |

| Coronary artery bypass grafting | 3 (2.6) |

| Lung resection, non-neoplasm | – |

| Craniotomy | 2 (1.7) |

| Other* | 1 (0.9) |

| Medical diagnoses | |

| Ventilator-associated pneumonia | 62 (53.9) |

| COPD (without pneumonia) | 31 (27.0) |

| Sepsis | 27 (23.5) |

| Neuromuscular disease | 20 (17.4) |

| Community acquired pneumonia | 17 (14.8) |

| Acute myocardial infarction | 13 (11.3) |

| Acute respiratory distress syndrome | 13 (11.3) |

| Congestive heart failure | 8 (7.0) |

| Diaphragm paralysis | 6 (5.2) |

| Cardiac arrest | 6 (5.2) |

| Pulmonary embolism | 6 (5.2) |

| New CVA/ICH | 3 (2.6) |

| Restrictive lung disease | 2 (1.7) |

| Traumatic brain injury | 1 (0.9) |

| Obstructive sleep apnea | 1 (0.9) |

| Other† | 14 (12.2) |

Data presented as n (%).

Resection of metastatic thymoma nodules;

Includes pneumothorax, hemothorax, neurological infection, chest trauma, metabolic coma, airway obstruction, bronchiolitis obliterans, endocarditis, polyneuropathy, empyema, paralysis associated with botulism, persistent bilateral pleural effusions, Still’s disease and smoke inhalation. AAA Abdominal aortic aneurysm; COPD Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CVA Cerebral vascular accident; ICH Intracranial hemorrhage

The median duration of the first TM trial tolerated in the PWC was 2.5 h (IQR 1.0 h to 8.6 h); 85 patients (73.9% [95% CI 65.9% to 81.9%]) achieved a 12 h TM trial and 76 (66.1% [95% CI 55.4% to 74.7%]) achieved a 24 h TM trial in a median duration of eight days (IQR one to 15 days) and 15 (IQR eight to 25 days), respectively. Fifteen patients did not achieve weaning success despite achieving a 24 h TM. Ventilator weaning success was achieved for 61 patients (53.0% [95% CI 43.9% to 62.2%]) in a median total duration of ventilation of 62 days (IQR 46 to 95 days); 14 days (IQR nine to 29 days) after PWC admission. Other weaning outcomes are shown in Table 3. No difference in weaning outcomes was noted for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and non-COPD patients (all P values >0.05). Unassisted dangling at the bedside was achieved by 46 patients (40.0% [95% CI 31.1% to 49.0%]) during PWC admission in a median of eight days (IQR four to 14 days). Fifteen patients never achieved unassisted dangling, 28 patients achieved before PWC admission (not reported for 26 patients). Assisted weight bearing was achieved by 39 patients (33.9% [95% CI 25.3% to 42.6%]) in a median 10 days (IQR four to 22 days) and assisted walking by 41 (35.7% [95% CI 26.9% to 44.4%]) patients in 14 days (IQR six to 30 days). Assisted weight bearing and assisted walking were not achieved by 20 and 21 patients, respectively (25 and 19 patients achieved assisted weight bearing before PWC admission; not reported 31 and 34 patients, respectively). Patients who achieved assisted weight bearing before PWC discharge were more likely to be alive one year later (P=0.02).

TABLE 3.

Weaning outcomes

| Patient | Ventilation weaning (n=115) | COPD (n=41) | Non-COPD (n=74) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Weaned and decannulated | 49 (42.6) | 16 (39.0) | 33 (44.6) |

| Tracheostomy retained | 12 (10.4) | 2 (4.9) | 10 (13.5) |

| Noninvasive ventilation (part time) | 6 (5.2) | – | 6 (8.1) |

| Ventilator dependent (full time) | 29 (25.2) | 10 (24.4) | 19 (25.7) |

| Ventilator dependent (part time) | 4 (3.5) | 2 (4.9) | 2 (2.7) |

| Dead | 15 (13.0) | 11 (26.8) | 4 (5.4) |

Data presented as n (%). COPD Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

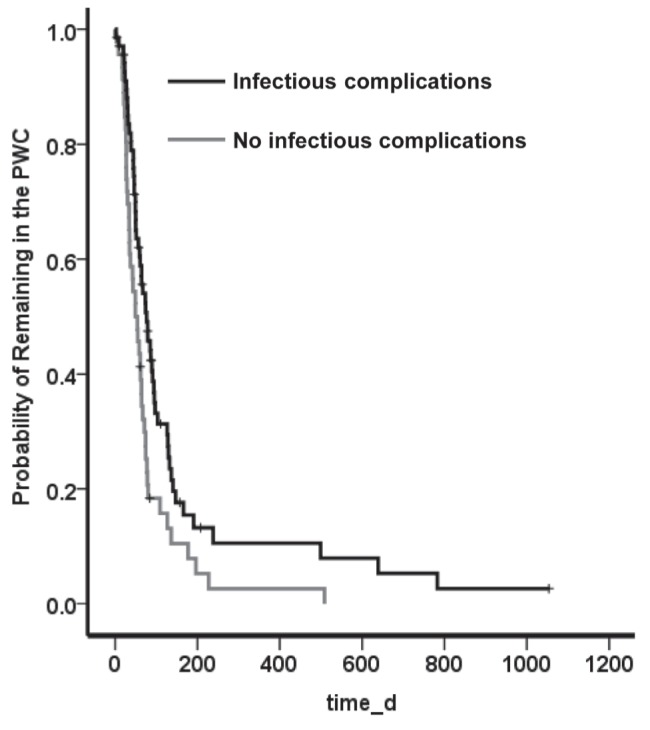

The Kaplan Meier-estimated PWC median LOS for patients admitted for ventilator weaning was 64 days (IQR 35 to 109 days). Infection-related complications including ventilator-assisted pneumonia, urinary tract infection, sepsis, Clostridium difficile infection and infected percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy site were experienced by 69 patients (60.0% [95% CI 50.9% to 68.5%]) and resulted in prolonged median PWC LOS: 76 days (IQR 45 to 132 days) versus 49 days (IQR 27 to 77 days) (P=0.007) (Figure 1). Discharge destinations are reported in Table 4. Due to the time-limited nature of the weaning program and repatriation agreements, the most frequent discharge destination for patients admitted for ventilator weaning was to the referring ICU (six weaned and 25 ventilator-dependent patients). Reasonable functional status on PWC discharge (Zubrod scores 0 to 2) was noted for 33 of 115 patients (28.7% [95% CI 21.2% to 37.6%]). Of the 91 patients discharged from the PWC for one year, 43 (47.3% [95% CI 37.3% to 57.4%]) survived; of the 78 discharged for two years, 27 (34.6% [25.0% to 45.7%]) were alive; of the 53 discharged for three years, 19 (35.9% [95% CI 24.3% to 49.3%]) were alive; seven of 22 (31.8% [95% CI 16.4% to 52.7%]) survived to five years. Vital status for 20 (22.0%), 21 (26.9%), 16 (30.2%) and eight (36.4%) for one-, two-, three- and five-year survival, respectively, was not determined.

Figure 1).

Prolonged-ventilation Weaning Centre (PWC, Toronto, Ontario) length of stay. d Days

TABLE 4.

Discharge outcomes

| Patients discharged alive | Invasive ventilation (n=100) |

|---|---|

| Acute care hospital: intensive care unit | 31 (27.0) |

| Acute care hospital: step-down unit/floor | 29 (25.2) |

| Rehabilitation | 21 (18.3) |

| Home/assisted living | 15 (13.0) |

| Long-term ventilation institution | 3 (2.6) |

| Nursing home | 1 (0.9) |

Data presented as n (%)

DISCUSSION

A key finding from our study was that the weaning success rate for patients admitted and discharged alive from the specialized PWC was moderate, despite a prolonged ICU stay before admission, but comparable with studies reporting weaning outcomes from specialized weaning centres in other countries (8,14,15). These patients required a substantial length of time to wean (median 68 days) suggesting appropriate referral decisions were made. Our study is also unique in that we documented the achievement of important weaning and mobility milestones. Patients were admitted with limited ability to tolerate spontaneous breathing; however, 75% of those that achieved a 24 h TM trial did so within one month. Ability to weight bear with assistance was also achieved by most patients within this time frame.

The protracted duration of ICU stay before PWC admission reflects both a delay in referrals from ICUs and the length of time to complete patient acceptance and transfer arrangements. The median duration of ICU stay before admission to a weaning centre reported in other studies published in the past decade ranges from 19 days (16) to 29 days (17). In the US, The Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services Diagnosis Related Group (DRG) funding arrangements for patients receiving >21 days of ventilation and the proliferation of long-term acute care hospitals (18) means these patients are usually transferred out of the ICU after three weeks of ventilation. No such financial incentives currently exist in Canada; rather, referral to the PWC is reliant on ICU clinicians identifying appropriate patients in a timely manner.

Another important finding was that 13% of patients admitted for ventilator weaning died in the PWC and 61% of patients who survived had poor functional status on PWC discharge despite functioning independently at home before ICU admission. Fifty per cent of our patients survived to one year, but only 26% were alive at five years. Inpatient mortality rates for individuals experiencing PMV vary from 5% (19) to 50% (20) due to differences in admission policies, patient characteristics and processes such as end-of-life decision making. Few studies report survival rates to five years. An understanding of the likelihood of unfavourable outcomes may assist patients, families and clinicians when faced with decisions regarding continuation of weaning, escalation or withdrawal of support, and end-of-life care (2).

Currently, there is no evidence that confirms the superiority of specialized weaning centres over ICUs for outcomes such as weaning success or improved functional status. It is unclear whether similar outcomes would have been achieved if these patients remained within the ICU setting. Some aspects of the comprehensive rehabilitative focus offered by specialized weaning centres may now be found in ICUs that promote early physical and occupational therapy (21), structured weaning processes (22), and optimal communication with patients and families (23). However, potential cost savings to the health care system do exist. In 2005, the Ontario Case Costing Initiative data indicated the average per diem cost for an ICU bed ranges from $2,024 to $3,745 (24), whereas the average daily direct cost for the PWC program has been estimated to be approximately $1,200, although neither account for costs associated with services provided by physicians.

Two other findings from the present study raise concern. First, patients experienced high rates of infectious complications resulting in increased PWC LOS. Although the rate of infectious complications is comparable with those reported in a multicentre study of PMV patients from the US (8), this finding indicates the need for practice improvements focused on infection prevention strategies. Second, 34% of patients were transferred back to the referring ICU due to a lack of a suitable alternative discharge placement. This finding emphasizes the unavailability and/or difficulty of accessing long-term ventilator placements in a timely manner in Ontario. The psychological impact to both patients and families of readmission to the ICU has not been measured but can be presumed to be extremely negative. Moreover, this presents substantial burden and costs to limited critical care resources, which could be avoided with improved access to long-term ventilation beds.

Our study is limited in that it represents data from a single centre and, thus, cannot be generalized to other patients undergoing PMV. Several single-centre studies from the US, Europe, United Kingdom and Asia (25) have described patient characteristics and outcomes for this patient population. However, our report is the first to describe data from a specialized weaning centre in Canada that includes weaning and mobility milestones as well as vital status follow-up for five years. Due to substantial international differences in organizational models of care for PMV patients, it is important to add data describing the Canadian context. The retrospective nature of data collection meant that some data, particularly those relating to mobility outcomes, was unobtainable due to lack of documentation or missing health records. Our data on long-term survival needs to be viewed cautiously due to the 23% loss to follow-up. Furthermore, additional data on outcomes for patients transferred back to the acute care sector would have further expanded our understanding of the trajectory of care for these patients.

CONCLUSIONS

Despite a prolonged ICU LOS before referral, weaning outcomes were similar to those previously reported in other countries and organizational care models. The potential for ventilator dependency, poor functional status or death, within a reasonably short time frame, must be considered by clinicians, patients and family members during discussions regarding care options.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Keti Dzamova, Mika Nonoyama and Shaghayegh Rezaie for their assistance with data collection and entry.

Footnotes

FUNDING: This study was funded by the Toronto East General Hospital Community Based Research Fund.

REFERENCES

- 1.Scheinhorn D, Chao DC, Stearn-Hassenpflug M, Gracey D. Post-ICU weaning from mechanical ventilation: The role of long-term facilities. Chest. 2001;120:482–4. doi: 10.1378/chest.120.6_suppl.482s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.MacIntyre NR, Epstein SK, Carson S, Scheinhorn D, Christopher K, Muldoon S. Management of patients requiring prolonged mechanical ventilation: Report of a NAMDRC consensus conference. Chest. 2005;128:3937–54. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.6.3937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Engoren M, Arslanian-Engoren C, Fenn-Buderer N. Hospital and long-term outcome after tracheostomy for respiratory failure. Chest. 2004;125:220–7. doi: 10.1378/chest.125.1.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lone N, Walsh T. Prolonged mechanical ventilation in critically ill patients: Epidemiology, outcomes and modelling the potential cost consequences of establishing a regional weaning unit. Crit Care. 2011;15:R102. doi: 10.1186/cc10117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Esteban A, Anzueto A, Frutos F, et al. Characteristics and outcomes in adult patients receiving mechanical ventilation: A 28-day international study. JAMA. 2002;28:345–55. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.3.345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coplin W, Pierson D, Cooley K, Newell D, Rubenfeld G. Implications of extubation delay in brain-injured patients meeting standard weaning criteria. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161:1530–6. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.5.9905102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bigatello LM, Stelfox HT, Berra L, Schmidt U, Gettings EM. Outcome of patients undergoing prolonged mechanical ventilation after critical illness. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:2491–7. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000287589.16724.B2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scheinhorn DJ, Stearn-Hassenpflug M, Votto JJ, et al. Post-ICU mechanical ventilation at 23 long-term care hospitals: A multicenter outcomes study. Chest. 2007;131:85–93. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clini E, Siddu P, Trianni L, Graziosi R, Crisafulli E, Nobile M. Activity and analysis of costs in a dedicated weaning centre. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis. 2008;69:55–8. doi: 10.4081/monaldi.2008.396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Critical Care Secretariat . About the critical care secretariat. Toronto: Ministry of Health and Long Term Care; 2006. < www.health.gov.on.ca/english/providers/program/critical_care/cct_strategy.html.> (Accessed April 12, 2011). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scheinhorn DJ, Hassenpflug MS, Votto JJ, et al. Ventilator-dependent survivors of catastrophic illness transferred to 23 long-term care hospitals for weaning from prolonged mechanical ventilation. Chest. 2007;131:76–84. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Knaus WA, Draper EA, Wagner DP, Zimmerman JE. An evaluation of outcome from intensive care in major medical centres. Ann Int Med. 1986;104:410–8. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-104-3-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Charlson M, Pompei P, Ales K, MacKenzie C. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: Devlopment and validation. J Chron Dis. 1987;40:373–83. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang P-H, Hung J-Y, Yang C-J, et al. Successful weaning predictors in a respiratory care center in Taiwan. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2008;24:85–91. doi: 10.1016/S1607-551X(08)70102-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schonhofer B, Berndt C, Achtzehn U, et al. Weaning from mechanical ventilation. A survey of the situation in pneumologic respiratory facilities in Germany. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2008;133:700–4. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1067309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aboussouan L, Lattin C, Vijay V. Determinants of time-to-weaning in a specialized respiratory care unit. Chest. 2005;128:3117–26. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.5.3117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cohen J, Starobin D, Papirov G, et al. Initial experience with a mechanical ventilator weaning unit. IMAJ. 2005;7:166–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kahn J, Benson N, Appleby D, Carson S, Iwashyna T. Long-term acute care hospital utilization after critical illness. JAMA. 2010;303:2253–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Quinnell T, Pilsworth S, Shneerson J, Smith I. Prolonged invasive ventilation following acute ventilatory failure in COPD: Weaning results, survival, and the role of noninvasive ventilation. Chest. 2006;129:133–9. doi: 10.1378/chest.129.1.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carson S, Bach P, Brzozowski L, Leff A. Outcomes after long-term acute care. An analysis of 133 mechanically ventilated patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159:1568–73. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.5.9809002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schweickert W, Pohlman M, Pohlman A, et al. Early physical and occupational therapy in mechanically ventilated, critically ill patients: A randomized controlled trial. Lancet. 2009;373:1874–82. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60658-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blackwood B, Alderdice F, Burns K, Cardwell C, Lavery G, O’Halloran P. Protocolized versus non-protocolized weaning for reducing the duration of mechanical ventilation in critically ill adult patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;5:CD006904. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006904.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scheunemann L, McDevitt M, Carson S, Hanson L. Randomized, controlled trials of interventions to improve communication in intensive care: A systematic review. Chest. 2011;139:543–54. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-0595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.MOHLTC . Chronic ventilation strategy taskforce: Final report. Toronto: MOHLTC; 2006. < www.health.gov.on.ca/english/providers/program/critical_care/cct_reports.html> (Accessed April 23, 2011). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rose L, MacKenzie L, Tessolini J, Fraser I. Systematic evaluation of outcomes for patients requiring prolonged mechanical ventilation. Intensive Care Med. 2009;35:S186. [Google Scholar]