Abstract

Myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) is a clonal hematopoietic stem cell disorder of elderly people. Cardiac dysfunction is a marker of grim prognosis in MDS. We evaluated cardiac dysfunction of MDS patients with or without transfusion dependency by tissue doppler echocardiography. We found the average values of ventricular end-systolic and end-diastolic volumes in transfusion dependency MDS group higher than others. These results were strongly correlated to hemoglobin levels. Tissue Doppler Echocardiography should be routinely performed in MDS patients to detect preclinical cardiac alterations and prevent more heart insults in this group of chronic anemic aged patients.

Keywords: Myelodysplastic syndrome, Comorbidity, Cardiac dysfunction

To the Editor

Myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) is a clonal hematopoietic stem cell disorder and anemia with transfusion dependency is detected in up to 60% of patients [1]. Early recognition of patients at risk of heart failure is difficult because global ventricular function and exercise capacity in chronically transfused patients may remain normal until late in the disease [2].

We evaluated three groups of MDS patients: cases with transfusion dependency (T-MDS), patients without transfusion dependency (NT-MDS) and age-matched controls. Transfusion dependency was considered as reported by Malcovati et al. [3]. Echo-Doppler, tissue velocity imaging and strain measures were obtained using General Electric-Healthcare (GE, Vivid-7) system with a matrix probe M3S.

Parametric data were analyzed by “one-way” analyzes of variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni’s Multiple Comparison as a post-test. Non-parametric data were analyzed by Kruskal-Wallis. The studies of correlation was assessed by Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r).

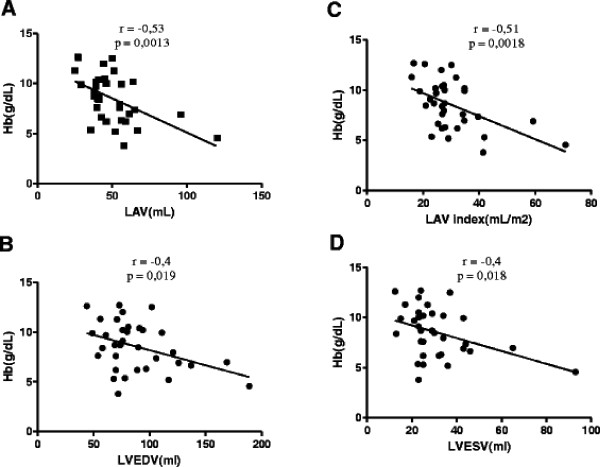

The three groups were composed of 13 T-MDS, 21 NT-MDS and 14 controls. There were no significant differences between groups. See Table 1. Table 2 presents the echocardiographic parameters. The average values of ventricular end-systolic and end-diastolic volumes in T-MDS group were significantly higher than NT-MDS and controls (p <0.05 and p <0.04 respectively). The left atrial volume indexed (LAV index) was significantly larger in patients of T-MDS group than NT-MDS and controls (35.9 ± 15 mL/m2, 26.6 ± 5,2 mL/m2, 22.8 ± 8 mL/m2 respectively) (p <0.004.). A strong correlation between hemoglobin levels and LVEDV (left ventricular end-diastolic volume), LVESV (left ventricular end-systolic volume), LAV (left atrial volume) and LAV index was observed, with r values of −0.4, -0.4, -0.53 and 0.51 respectively (p <0.02, p <0.02, p <0.002 and p <0.002 respectively). See Figure 1. Otherwise, we found no correlation between ferritin levels and echocardiographic parameters.

Table 1.

Patients were diagnosed and classified according to WHO, IPSS and WPSS criteria

| Patient | WHO | IPSS | Serum Ferritin | Transfusion therapy | Transfusional dependent | WPSS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1 |

RA |

NA |

288,8 |

No transfusion therapy |

NO |

NA |

|

2 |

RAEB 2 |

INT 1 |

94,7 |

No transfusion therapy |

NO |

HIGH |

|

3 |

RCMD |

INT 1 |

416,5 |

14 RCC |

NO |

LOW |

|

4 |

RARS |

INT 1 |

1.994,0 |

69 RCC |

Yes |

LOW |

|

5 |

RA |

NA |

826,0 |

No transfusion therapy |

NO |

NA |

|

6 |

RA |

LOW |

22,4 |

No transfusion therapy |

NO |

LOW |

|

7 |

MDS-T |

NA |

3.484,0 |

42 RCC |

Yes |

NA |

|

8 |

RARS |

NA |

1.399,0 |

64 RCC |

Yes |

NA |

|

9 |

RCMD |

NA |

7.107,0 |

81 RCC |

Yes |

NA |

|

10 |

RARS |

LOW |

1.587,0 |

20 RCC |

Yes |

LOW |

|

11 |

RARS |

INT 1 |

132,0 |

04 RCC |

NO |

INT |

|

12 |

RARS |

LOW |

1.937,8 |

82 RCC |

Yes |

LOW |

|

13 |

RARS |

NA |

541,0 |

No transfusion therapy |

NO |

NA |

|

14 |

RA |

LOW |

307,0 |

No transfusion therapy |

NO |

VERY LOW |

|

15 |

RCMD |

INT 1 |

5.113,1 |

96 RCC |

Yes |

INT |

|

16 |

RCMD |

LOW |

38,0 |

No transfusion therapy |

NO |

LOW |

|

17 |

RCMD |

NA |

98,0 |

03 RCC |

NO |

NA |

|

18 |

RARS |

LOW |

318,0 |

No transfusion therapy |

NO |

VERY LOW |

|

19 |

RCMD |

LOW |

87,0 |

No transfusion therapy |

NO |

LOW |

|

20 |

RCMD |

NA |

765,0 |

38 RCC |

Yes |

NA |

|

21 |

RCMD |

INT 1 |

780,0 |

17 RCC |

Yes |

HIGH |

|

22 |

RARS |

LOW |

356,2 |

No transfusion therapy |

NO |

VERY LOW |

|

23 |

RCMD |

INT 1 |

298,4 |

No transfusion therapy |

NO |

LOW |

|

24 |

RCMD |

INT 1 |

2.160,0 |

24 RCC |

Yes |

HIGH |

|

25 |

RA |

LOW |

86,4 |

No transfusion therapy |

NO |

VERY LOW |

|

26 |

RCMD |

NA |

276,0 |

No transfusion therapy |

NO |

NA |

|

27 |

RCMD |

NA |

1.922,3 |

24 RCC |

Yes |

NA |

|

28 |

RAEB 2 |

INT 2 |

1.022,0 |

42 RCC |

Yes |

VERY HIGH |

|

29 |

RARS |

NA |

321,0 |

No transfusion therapy |

NO |

NA |

|

30 |

RCMD |

NA |

223,0 |

12 RCC |

Yes |

NA |

|

31 |

RAEB 1 |

INT 1 |

229,0 |

03 RCC |

NO |

VERY LOW |

|

32 |

RCMD |

INT 1 |

132,4 |

No transfusion therapy |

NO |

INT |

|

33 |

RCMD |

NA |

556,0 |

04 RCC |

NO |

NA |

| 34 | RCMD | NA | 850,0 | 10 RCC | NO | NA |

Legend. MDS unclassifiable; RA, refractory anemia; RAEB, RA with excess of blasts; RARS, RA with ringed sideroblasts; RCMD, refractory cytopenia with multilineage dysplasia; t-MDS, therapy-related MDS; WHO, World Health Organization. red cell concentrate – RCC. NA -Not applicable, due to cytogenetics by G-banding without metaphases).

Table 2.

Echocardiographic parameters of patients and controls

| Controls(14) | NT-MDS(21) | T-MDS(13) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Baseline demographics and characteristics |

|

|

|

|

|

Age (year) |

72.4 ± 8 (58–84) |

70.3 ± 14 (47–88) |

65.2 ± 20 (27–90) |

NS |

|

Gender (m/f) |

(6/8) |

(7/14) |

(6/7) |

|

|

Body weigth (kg) |

66.0 ± 11.9 (46 – 83) |

63.7 ± 10.1 (43.6 – 91.3) |

64.9 ± 10.1 (49.3 – 90) |

NS |

|

Height (m) |

1.59 ± 0.09 (1.45 – 1.75) |

1.57 ± 0.07 (1.46 – 1.72) |

1.59 ± 0.08 (1.45 – 1.70) |

NS |

|

BSA (m2) |

1.68 ± 0.16 (1.42 – 1.98) |

1.64 ± 0.15 (1.33 – 2.01) |

1.67 ± 0.15 (1.4 – 2.01) |

NS |

|

BMI (kg/m2) |

26.2 ± 5.7 (19.1 – 36.9) |

25.8 ± 2.9 (20.5 – 32.3) |

25.5 ± 3.7 (21.4 – 32.7) |

NS |

|

HR (bpm) |

75.8 ± 5.4 (66–83) |

77.6 ± 1.4 (66–88) |

78.4 ± 2.2(65–90) |

NS |

|

SBP (mmHg) |

|

139.2 ± 19 (110–180) |

121.8 ± 16 (100–150) |

<0.02 |

|

DBP (mmHg) |

|

77.9 ± 12 (60–108) |

70 ± 9.6 (60–90) |

NS |

|

Hb (g/dL) |

|

9.85 ± 1.8 (6.6 - 12.7) |

6.5 ± 1.7 (3.8 - 9.9) |

<0.001 |

|

Ferritin (ng/mL) |

|

298.8 ± 234 (22.4 a 850) |

2269 ± 1931 (223 a 7101) |

<0.001 |

|

Chamber quantification and ejection fraction of patients and controls |

|

|

|

|

|

LVDD (mm) |

46.0 ± 4.7 (40–57) |

48.5 ± 3.9 (41–56) |

49.3 ± 6.6 (40–64) |

NS |

|

LVSD (mm) |

26.9 ± 4.9 (19–39) |

27.7 ± 3.7 (22–37) |

29.5 ± 6.8 (23–50) |

NS |

|

IVS (mm) |

8.9 ± 2.3 (6–16) |

8.5 ± 0.9 (7–11) |

8.9 ± 1.4 (7–12) |

NS |

|

LVPW (mm) |

8.5 ± 1.7 (6–13) |

8.4 ± 0.7 (7–10) |

8.8 ± 1.4 (7–12) |

NS |

|

MASS (g) |

165.9 ± 61,0 (79–326) |

173.8 ± 34.1 (116–249) |

165.9 ± 61.0 (90–321) |

NS |

|

MASS index (g/m2) |

101.3 ± 37 (55.6 - 185) |

106 ± 18 (73–140.7) |

110 ± 37.1 (56.2 - 198) |

NS |

|

EF%TEI |

71.8 ± 7.6 (58.2 - 89) |

71.9 ± 6.5 (58.8 - 80.1) |

69.8 ± 9.3 (43.6 - 83.9) |

NS |

|

FS (%) |

41.4 ± 6.8 (31.2 - 58) |

41.6 ± 5.7 (31–48.7) |

39.4 ± 7.2 (22–53) |

NS |

|

LA (mm) |

32 ± 4.2 (27–44) |

33.4 ± 4.2 (28–43) |

36.5 ± 4.9 (31–46) |

<0.04* |

|

EF%SIM |

67.7 ± 7.3 (50.1 - 81.3) |

66.2 ± 4.8 (55.2 - 76.1) |

64.7 ± 5.4 (50.7 - 70.8) |

NS |

|

LVEDV (ml) |

65.5 ± 18 (37–105) |

85.1 ± 29.9 (44–169) |

92.8 ± 36.1 (49–189) |

<0.05* |

|

LVESV (ml) |

20.5 ± 6.2 (10–28) |

28.7 ± 11.9 (12.5 - 65) |

33.8 ± 19.7 (15–93) |

<0.04* |

|

LAV (ml) |

39.1 ± 14.5 (17–69) |

43.5 ± 10.3 (25–64) |

59.8 ± 24.8 (29–120) |

<0.006** |

|

LAV index (mL/m2) |

22.8 ± 8 (10.5 - 39.6) |

26.5 ± 5.2 (15.9 - 34.8) |

35.9 ± 15 (18.8 - 70.9) |

<0.004** |

|

Doppler parameters (transmitral and myocardial tissue) and strain of patients and controls | ||||

|

Evel(cm/s) |

77.2 ± 13.2 (55.4 - 105) |

89.6 ± 20 (63–128) |

96.6 ± 14.2 (68.5 - 116) |

<0.02* |

|

Avel(cm/s) |

94.3 ± 18 (68.6 - 137.3) |

100.2 ± 19 (68.5 - 131) |

100.6 ± 27 (52.8 - 145) |

NS |

|

E/A |

0.83 ± 0.2 (0.6 - 1.2) |

0.9 ± 0.2 (0.6 - 1.4) |

1.0 ± 0.26 (0.64 - 1,6) |

NS |

|

Em(cm/s) |

8.6 ± 3.2 (4.1 - 14) |

9.3 ± 2.4 (5.4 - 14) |

10.4 ± 2.5 (7.5 a 14.8) |

NS |

|

E/Em |

10 ± 3.4 (5.3 - 16.2) |

10.3 ± 3,9 (5.6 - 20) |

9.7 ± 2.9 (5.9 - 14.4) |

NS |

|

LV-Sm(cm/s) |

6.5 ± 1.3 (5.1 - 9.5) |

7.9 ± 1.3 (5.5 - 10.8) |

7.8 ± 1.3 (6–10,3) |

<0.02* |

|

RV-Sm(cm/s) |

10.1 ± 0.7 (9.1 - 11) |

11.4 ± 3.3 (7.6 - 19) |

12.3 ± 1,5 (9.8 - 14,7) |

NS |

|

TAPSE(mm) |

24.9 ± 4.2 (20–33) |

28.2 ± 5.3 (21–39) |

28.9 ± 5 (22–40) |

NS |

|

VD basal(mm) |

30.1 ± 6.4 (22–48) |

31.7 ± 4 (24–41) |

31.5 ± 4 (23–39) |

NS |

| ST2DL (%) | −19.9 ± 2.7 (−24 to −13) | −20.7 ± 2.5 (−25 to −16,8) | −20.9 ± 1.4 (−23 to - 18,6) | NS |

Legend. NT-MDS: non-transfused patients; T-MDS: transfused patients; LVDD: left ventricular diastolic diameter; LVSD: left ventricular systolic diameter; IVS: inter-ventricular septum; LVPW: left ventricular posterior wall; MASS: left ventricular mass; EF%TEI: ejection fraction Teicholz; FS: fractional shortening; LA: left atrial diameter; EF%SIM: ejection fraction Simpson; LVEDV: left ventricular end-diastolic volume; LVESV: left ventricular end-systolic volume; LAV: left atrial volume.

Figure 1.

Linear correlation between left cardiac volumes and values of hemoglobin. A.LAV: left atrial volume.B.LVEDV: left ventricular end-diastolic volume;C.LAV index : left atrial volume index.D.LVESV: left ventricular end-systolic volume.

The reduction of blood viscosity in severe anemia increases blood return [4] and ventricular preload which lead to atrial and ventricular enlargement observed in T-MDS patients. Confirming this hypothesis, these results are correlated to hemoglobin levels.

The T-MDS group showed no clinical sign of cardiac dysfunction. Otherwise, cardiac alterations were detected by tissue-doppler echocardiography, a relative fast and cheap bedside method to evaluate heart function. Echocardiography should be routinely performed in MDS patients to detect preclinical cardiac alterations and prevent more heart insults in these group of chronic anemic aged patients.

Abbreviation

NT-MDS, Non-transfused patients; T-MDS, Transfused patients; LVDD, Left ventricular diastolic diameter; LVSD, Left ventricular systolic diameter; IVS, Inter-ventricular septum; LVPW, Left ventricular posterior wall; LVEDV, Left ventricular end-diastolic volume; LVESV, Left ventricular end-systolic volume; LAV, Left atrial volume; RCC, Red cell concentrate; VD, Ventricular dysfunction.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

CCMC was the principal investigator and takes primary responsibility for the paper. CBGG provide technical support. MRAM participated in the statistical analysis. JCS performed the laboratory work for this study and edited the manuscript. SMMM provided critical revision. RFP coordinated the research and wrote the paper.

Contributor Information

Cláudio César Monteiro de Castro, Email: claudio.cezar@yahoo.com.br.

Carlos Bellini Gondim Gomes, Email: carlosbellini@hotmail.com.

Manoel Ricardo Alves Martins, Email: mramartins@gmail.com.

Juliana Cordeiro de Sousa, Email: cordeiro.juliana@gmail.com.

Silvia MM Magalhaes, Email: silviamm@ufc.br.

Ronald F Pinheiro, Email: ronaldpinheiro@pq.cnpq.br.

Acknowledgements

Support by CAPES CNPq and FUNCAP.

References

- Cazzola M, Della Porta MG, Travaglino E, Malcovati L. Classification and prognostic evaluation of myelodysplastic syndromes. Semin Oncol. 2011;38(Suppl 5):627–634. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2011.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naqvi K, Garcia-Manero G, Sardesai S, Oh J, Vigil CE, Pierce S, Lei X, Shan J, Kantarjian HM, Suarez-Almazor ME. Association of comorbidities with overall survival in myelodysplastic syndrome: development of a prognostic model. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2240–2246. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.31.3353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malcovati L, Porta MG, Pascutto C, Invernizzi R, Boni M, Travaglino E, Passamonti F, Arcaini L, Maffioli M, Bernasconi P, Lazzarino. Prognostic factors and life expectancy in myelodysplastic syndromes classified according to WHO criteria: a basis for clinical decision making. J Clin Oncol. 2005;20(Suppl 30):7594–7603. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.7038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmer R. Anemia and aging: an overview of clinical, diagnostic and biological issues. Blood Rev. 2001;15:9–18. doi: 10.1054/blre.2001.0146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]