Abstract

Nuclear pore complexes (NPCs) facilitate selective transport of macromolecules across the nuclear envelope in interphase eukaryotic cells. NPCs are composed of roughly 30 different proteins (nucleoporins) of which about one third are characterized by the presence of phenylalanine-glycine (FG) repeat domains that allow the association of soluble nuclear transport receptors with the NPC. Two types of FG (FG/FxFG and FG/GLFG) domains are found in nucleoporins and Nup98 is the sole vertebrate nucleoporin harboring the GLFG-type repeats. By immuno-electron microscopy using isolated nuclei from Xenopus oocytes we show here the localization of distinct domains of Nup98. We examined the localization of the C- and N-terminal domain of Nup98 by immunogold-labeling using domain-specific antibodies against Nup98 and by expressing epitope tagged versions of Nup98. Our studies revealed that anchorage of Nup98 to NPCs through its C-terminal autoproteolytic domain occurs in the center of the NPC, whereas its N-terminal GLFG domain is more flexible and is detected at multiple locations within the NPC. Additionally, we have confirmed the central localization of Nup98 within the NPC using super resolution structured illumination fluorescence microscopy (SIM) to position Nup98 domains relative to markers of cytoplasmic filaments and the nuclear basket. Our data support the notion that Nup98 is a major determinant of the permeability barrier of NPCs.

Keywords: nuclear pore complex, nucleoporin, Nup98, FG repeats, permeability barrier, electron microscopy, SIM

Introduction

Nuclear pore complexes (NPCs) are the most distinctive structural components of the nuclear envelope (NE) and they mediate bidirectional macromolecular transport between the cytoplasm and the nucleus of interphase eukaryotic cells. Small molecules and ions can traverse the NPC by diffusion, whereas macromolecular trafficking of proteins and RNPs occurs in a signal- and receptor-dependent manner (reviewed in (Fried and Kutay, 2003; Walde and Kehlenbach, 2011)). The 3-D architecture of the NPC has been studied extensively in various species by means of electron microscopy (EM) and more recently by cryo-electron tomography, resulting in today's consensus model of the NPC (reviewed in (Lim et al., 2008); (Beck et al., 2007; Fiserova et al., 2009; Frenkiel-Krispin et al., 2009)). Accordingly, the NPC consists of an eightfold symmetric central framework, composed of a spoke complex that is joined to cytoplasmic and nuclear ring moieties. Eight filaments emanate from the cytoplasmic ring, whereas the nuclear ring is capped by the nuclear basket, an assembly of eight filaments that join to form the distal ring. The central framework embraces a central pore of about 45 nm in diameter in the plane of the NE that mediates both diffusion of small molecules (Feldherr and Akin, 1997; Keminer et al., 1999; Mohr et al., 2009) and the signal-dependent nuclear transport of large molecules between the nucleus and the cytoplasm. More recent studies indicate that in contrast to this very simplistic view distinct transport routes may exist for different cargo within the central pore (Fiserova et al., 2010; Naim et al., 2007; Terry and Wente, 2007).

NPCs are large multiprotein complexes that are composed of ~30 distinct subunits know as nucleoporins or Nups, which are typically organized in repetitively arranged subcomplexes to form the NPC (reviewed in (D'Angelo and Hetzer, 2008; Lim and Fahrenkrog, 2006; Lim et al., 2008; Walde and Kehlenbach, 2011)). In the plane of the NE, NPCs exhibit eightfold rotational symmetry and nucleoporins therefore are present in copy numbers of eight per NPC or multiple thereof, with a total of about 600 individual protein molecules forming the giant ~100 MDa vertebrate NPC. Moreover, nucleoporins are typically multi-domain proteins with certain structural domain motifs such as coiled-coils and ß-propellers being repeated employed (Schwartz, 2005). Phenylalanine-glycine (FG)-repeat domains, which are found in about one third of the nucleoporins, are implicated in the interaction of nuclear transport receptors with the NPC and are natively unfolded and highly flexible domains (Bayliss et al., 2000; Denning et al., 2003). Due to their unstructured character individual FG-repeat domains exhibit a large range of spatial distribution within the NPC as revealed by immnuo-EM localization of the repeat domains of distinct vertebrate nucleoporins, such as Nup153, Nup214 and Nup62 (Fahrenkrog and Aebi, 2003; Fahrenkrog et al., 2002; Paulillo et al., 2005; Schwarz-Herion et al., 2007). Moreover, the location of FG-domains in the NPC can be influenced by the transport state of the NPC as well as by chemical effectors, such as Ca2+ ions or ATP (Paulillo et al., 2006; Paulillo et al., 2005).

Nup98 is a mobile, FG-repeat harboring nucleoporin with a multitude of roles in nucleocytoplasmic transport including RNA export and protein import (Blevins et al., 2003; Fontoura et al., 2000; Powers et al., 1995; Powers et al., 1997; Radu et al., 1995; Zolotukhin and Felber, 1999). Nup98 is dynamically associated with the NPC and its mobility within the nucleus is coupled to ongoing a transcription (Griffis et al., 2002; Griffis et al., 2004). Nup98 was recently identified as co-factor of the nuclear protein export factor CRM1 (Oka et al., 2010). In addition to nucleocytoplasmic transport, Nup98 is also involved in the regulation of gene expression of many developmental genes (Capelson et al., 2010; Kalverda et al., 2010). During mitosis Nup98 regulates mitotic spindle assembly through direct association with microtubules and the depolymerizing kinesin MCAK (Cross and Powers, 2011) and also influences the timing of mitotic exit by preventing securin degradation by the anaphase promoting complex (Jeganathan et al., 2005).

Based upon its amino acid sequence Nup98 is comprised of two major domains: an N-terminal FG/GLFG repeat domain and a C-terminal autoproteolytic domain (Rosenblum and Blobel, 1999). The binding site for nucleoporin Rae1/Gle2 forms a distinct region within the repeat domain, known as GLEBS domain (Pritchard et al., 1999). The localization of Nup98 within the NPC has varied with results from different groups. Initially Nup98 was mapped to the nuclear basket of the NPC (Frosst et al., 2002; Radu et al., 1995), while subsequently it was found to reside on both faces of the NPC and to participate in two distinct nucleoporin subcomplexes (Griffis et al., 2003). These studies were carried out in mammalian cell lines and mostly employed antibodies that recognized by the antibodies the C-terminal domain of Nup98, although Griffis et al. also observed a similar localization pattern using N-terminally tagged GFP-Nup98 and anti-GFP antibodies. In this study, we have further evaluated the localization of Nup98 in the NPC of Xenopus oocyte nuclei using immuno-EM and super resolution structured illumination microscopy (SIM) combined with either domain-specific antibodies or the expression of epitope-tagged of Nup98 to map its domain topology within the 3-D structure of the NPC. We show here that Nup98 is anchored to the center of the NPC by its C-terminal domain, while the FG-repeat domain of Nup98 appears flexible, locating to both sides of the NPC.

Material and Methods

Antibodies

The following antibodies were used in this study: a rabbit polyclonal anti-xNup98 peptide3 (Powers et al., 1995) against the C terminus of Xenopus Nup98 (residues 843-855; QGAQFVDRPESG); a rat monoclonal anti-Nup98 antibody against the N terminus of human Nup98 (residues 1-466; clone 2H10, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO; (Fukuhara et al., 2005)); a mouse monoclonal anti-myc antibody (clone 9E10, supernatant of hybridoma cell line).

For immunofluorescence, the following antibodies were used: rabbit anti-huNup98 C-terminal domain, residues 506-863 (Griffis et al., 2002); rat monoclonal anti-huNup98 GLFG domain (Fukuhara et al, 2005; Sigma); rabbit anti-huNup153 Zn Finger domain, (gift from Katie Ullman); mouse monoclonal SA1 anti-Nup153 C-terminal domain (gift from Brian Burke); rabbit anti-Nup358 IR domain (gift from Mary Dasso); mouse monoclonal 414 (Abcam, Cambridge, MA); Alexa-labeled secondary antibodies (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA).

DNA constructs

pcDNA3-myc-Nup98 was generated by digestion of pCS2-MT-Nup98 with BamHI and XhoI. This excises Nup98 along with 6 copies of the myc epitope derived from pCS-MT. The Nup98 fragment was then ligated into pcDNA3.0 (Invitrogen, Corporation, Carlsbad, CA). pEGFP-Nup358 was a kind gift of Dr. Joachim Köser (Biozentrum, University of Basel, Switzerland).

Western blotting

For HeLa protein extracts, approximately 1×106 cells were resuspended in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, containing protease inhibitor cocktail tablets from Roche) and then cleared by centrifugation. After protein quantification, 20 μg of protein were mixed with Laemmli loading buffer for gel electrophoresis. For Xenopus protein extracts, 15 nuclei isolated from oocytes were resuspended in 60μl of low salt buffer followed by addition of 30 μl of 3X Laemmli loading buffer. For gel electrophoresis, 20 μl of Xenopus extract were loaded. Proteins were separated on 7% SDS-PAGE before being transferred to PVDF membrane which was subsequently blocked with 5% non-fat milk. For immuno-blotting the following primary antibodies were used: anti-GLFG Nup98 (clone 2H10, 1/2000) and anti-C Nup98 (1/1000). All secondary antibodies were alkaline phosphatase-coupled anti-IgG antibodies (1/20.000; Sigma). All dilutions were carried out in 5% non-fat milk. Blots were developed using CDP-Star (Applied Biosystems).

Immuno-EM of isolated nuclei from Xenopus oocytes

Mature (stage 6) oocytes were surgically removed from female Xenopus laevis, and their nuclei were isolated as described (Fahrenkrog et al., 2002). Colloidal gold particles, ~8-nm in diameter, were prepared by reduction of tetrachloroauric acid with sodium citrate in the presence of tannic acid and antibodies were conjugated to colloidal gold particles as described (Slot and Geuze, 1985). Isolated nuclei were labeled as described previously (Fahrenkrog et al., 2002). Thin sections were cut on a Reichert Ultracut microtome (Reichert-Jung Optische Werke, Vienna, Austria) using a diamond knife (Diatome, Biel, Switzerland). The sections were collected on parlodion coated copper grids and stained with 6% uranyl acetate for 1 h followed by 2% lead citrate for 2 min. Electron micrographs were recorded with a Philips CM-100 transmission electron microscope (FEI Company, Hillsboro, OR) operated at an acceleration voltage of 80 kV equipped with a CCD camera.

Microinjection and immuno-EM of tagged human Nup98 in Xenopus nuclei

For microinjection of myc-Nup98 into nuclei, freshly isolated oocytes from Xenopus laevis were prepared and processed for microinjection as described (Fahrenkrog et al., 2002). 5 ng per microliter of pcDNA-myc-Nup98 was injected into each oocyte nucleus. The localization of the fusion proteins within the NPC were determined by using a monoclonal anti-myc directly conjugated to 8-nm colloidal gold.

Immunofluorescence

For immunofluorescence staining, HeLa cells were grown on glass #1.5 coverslips in DMEM with 10% FBS, 1% Glutamax (Invitrogen) and 1% each penicillin/streptomycin. Cells were simultaneously fixed and permeabilized with 2% formaldehyde (Ted Pella Inc, Redding, CA), 0.2% Triton-X100 in PBS for 15 minutes at RT. Cells were blocked for 30 minutes at RT in 5% BSA, 5% normal goat serum, 0.02% Triton-X100 in PBS and then incubated for 1 hr in primary antibody diluted in block solution. After washing, cells were incubated for 1 hr with the appropriate Alexa fluor-labeled secondary antibody diluted in block solution. Cells were then washed, stained with Hoechst and mounted with Vectashield (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). For transfection of GFP-Nup358 1.5 μg of plasmid was used per well of 6 well culture dishes. Cells were transfected with HeLa-Monster (Mirus Bio, Madison, WI) 48 hr before fixation and staining.

Microscopy and Image analysis

Fluorescence microscopy was carried out using a Nikon N-SIM microscopy system on an Eclipse Ti inverted microscope run with Nikon Elements software (Nikon Instruments Inc., Melville, NY). The samples were imaged with a 100x 1.49 NA objective and an iXon DU897 EM-CCD camera (Andor Technology PLC, Northern Ireland). Widefield images were acquired with a Hg lamp and the appropriate filters: 480/30 ex 535/40 em (Alexa488 and GFP) or 540/25 ex 692/68 em (Alexa555). Widefield images were deconvolved with Huygens software (Scientific Volume Imaging, Netherlands). SIM images were acquired with laser excitation and emission filters 488 nm ex 520/40 em (Alexa488 and GFP) and 561 nm ex and 640/40 em (Alexa 555). Images were acquired in 3D SIM mode (for each SIM image 15 images with 5 different phases of 3 different angular orientations of illumination were collected) and z-stacks were collected for each image. SIM images were processed with the Nikon Elements software. The reconstruction parameters were optimized to be: Structured illumination contrast = 1.5; Apodization Filter = 1.0; Width of 3D-SIM filter = 0.18. SIM images of 5-10 cells were acquired for each condition.

Images were analyzed in ImageJ (NIH, Bethesda, MD). Lines with a width of 3 pixels were drawn perpendicular to and intersecting the nuclear envelope at a point where both labels were present. The fluorescence intensity along the lines was recorded in each channel. Multiple line scans were assessed for each condition. In each case, a representative line scan is shown. For some antibody pairs, not every NPC showed separation of labels, but, when separated the relative position was never observed to be opposite of that illustrated.

Results

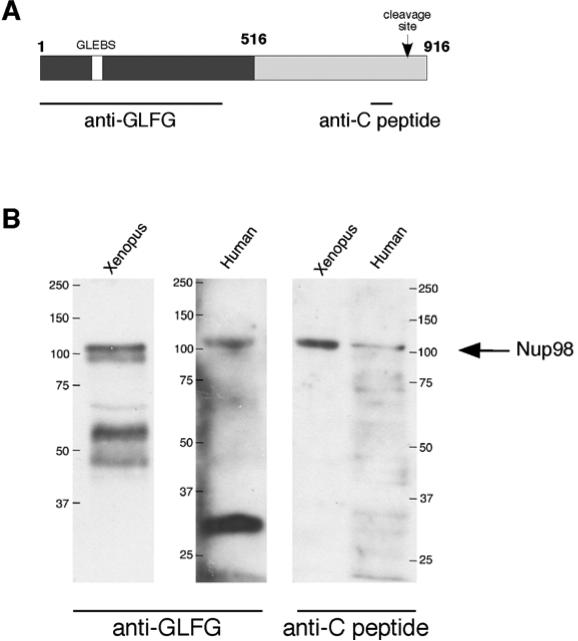

Characterization of domain-specific antibodies to Nup98

In order to gain a better understanding of the topology and domain accessibilty of Nup98 within the 3-D architecture of the NPC a panel of domain-specific antibodies against either Xenopus or human Nup98 were tested (Fig. 1A). These included a monoclonal antibody that recognizes the GLFG repeat doamin and a polyclonal anti-peptide antibody raised to a sequence very close to the C-terminus of processed Nup98. To characterize the specificity of theses antibodies and their suitability for immuno-EM, they were first tested by immunoblot analysis in HeLa whole cell and Xenopus nuclear extracts, respectively. Each antibody selectively recognized Nup98 in HeLa and Xenopus extracts (Fig. 1B). The anti-GLFG antibody recognizes a protein of ~60 kDa, possibly a breakdown product, in Xenopus but not in HeLa, whereas this antibody recognizes an additional protein of ~30 kDa in HeLa, but not in Xenopus. The anti-C peptide antibody recognizes exclusively Nup98 in Xenopus, while it shows some reactivity with a number of other human proteins. Together, these tests revealed that while some cross-reactivity of the GLFG antibody cannot be ruled out, the reactivity of the anti-C peptide antibody clearly reflects exclusively Nup98 in Xenopus oocyte nuclei.

Figure 1.

Domain-specific antibodies against Nup98. (A) A schematic presentation of human Nup98 is illustrated. A commercially available rat monoclonal antibody, which was raised against the GLFG domain (residues 1-466) of human Nup98 was used and a rabbit polyclonal antibody raised against a peptide within the C-terminal domain of Xenopus Nup98. Dark grey, FG/GLFG domain; light grey, C-terminal auteoproteolytic domain. GLEBS, residues 181-224. Cleavage site, between residues 863 and 864. (B) The anti-GLFG and the anti-C peptide antibodies detect a protein of about 110 kDa in both Xenopus and HeLa extracts. The positions of the markers in kilodalton are indicated.

Nup98 is anchored in the centre of the nuclear pore complex

To determine the localization of the two domains of Nup98 within the 3-D architecture of the NPC, we next used the domain-specific antibodies against Nup98 for immuno-EM. To do so, we isolated intact nuclei from Xenopus oocytes and incubated them with the respective antibody that has been directly coupled to 8-nm colloidal gold. During isolation and antibody incubation the nuclei remain intact, and the nuclear face of the NPCs appears as accessible as the cytoplasmic face (Fahrenkrog et al., 2002; Lussi et al., 2011; Paulillo et al., 2006; Paulillo et al., 2005). After incubation at room temperature, the labeled nuclei were prepared and embedded for thin-section EM (see Material and Methods). We first mapped the epitope that is recognized by the antibody directed against the C-terminal peptide of Nup98 (anti-C peptide). As shown in Fig. 2A, this anti-Nup98-C antibody recognized an epitope very central in the NPC. Quantification of the gold particle distribution (Fig. 2B) with respect to the central plane of the NPC indicated that about 72% of the gold particles were found at distances between -10 and +10 nm with a peak at 2.9 (±5.9) nm. Together with the corresponding average radial distances of 5.1 (±5.4) nm this corresponds to a localization in the center of the NPC.

Figure 2.

Localization of the C-terminal domain of Nup98 in isolated Xenopus nuclei. (A) Intact isolated nuclei were pre-immuno-labeled with the anti-C peptide antibody conjugated directly to 8-nm colloidal gold and prepared for EM by Epon embedding and thin-sectioning. A gallery of selected examples of gold-labeled NPCs in cross sections is shown. c, cytoplasm; n, nucleus. Scale bar, 100 nm. (B) Quantitative analysis of the gold particles associated with the NPCs after labeling with the anti-C antibody. Sixty-three gold particles were scored.

The GLFG-repeat domain of Nup98 is flexible

Next we wanted to resolve the location of the N-terminal GLFG-repeat domain of Nup98. As before, isolated intact Xenopus nuclei were incubated with the repeat domain antibody (anti-GLFG) directly conjugated to 8-nm colloidal gold. The epitope recognized by the antibody was analyzed by thin section immuno-EM. As shown in Fig. 3A, the anti-GLFG antibody detected epitopes on both the cytoplasmic and the nuclear face of the NPC. Quantification of the labeling pattern (Fig. 3B) relative to the central plane of the NPC revealed that about 70% of the particles were found on the cytoplasmic side at a mean distance of 16.0 (±11.9) nm, whereas ~30% of the gold particles were detected on the nuclear face of the NPC at distances ranging up to -100 nm. With corresponding mean radial distances of 10.0 (±7.5) nm on the cytoplasmic face of the NPC, this labeling pattern is consistent with a location near the cytoplasmic entry side of the central pore and within the nuclear basket region.

Figure 3.

Immuno-localization of the GLFG domain of Nup98. (A) A gallery of selected examples of NPCs in cross sections labeled with the anti-GLFG antibody directly conjugated to 8-nm colloidal gold in isolated, intact Xenopus nuclei is shown. c, cytoplasm; n, nucleus. Scale bar, 100 nm. (B) Quantitative analysis of the gold particle distribution in NPCs labeled with the anti-GLFG antibody conjugated to 8-nm colloidal gold. One hundred twenty five gold particles were scored. (C)Immuno-localization of N-terminally myc-tagged Nup98 expressed in Xenopus oocytes with a monoclonal anti-myc antibody directly conjugated to 8-nm gold. The antibody recognized epitopes on both faces of the NPC. Selected examples of labeled NPCs in cross sections are shown. c, cytoplasm; n, nucleus. Scale bar, 100 nm. (D) Quantitation of the gold particle distribution associated with the NPC in Xenopus nuclei that have incorporated myc-Nup98 after labeling with an anti-myc antibody. One hundred one gold particles were scored.

To confirm the multiple locations of the GLFG domain of Nup98 within the NPC obtained with the anti-GLFG monoclonal antibody, we expressed N-terminal myc-tagged human Nup98 in Xenopus oocyte nuclei. For this purpose, we microinjected the corresponding plasmids in Xenopus oocyte nuclei and the presence of the cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter allowed expression of myc-Nup98 in the oocytes. The location of the expressed protein was determined by using a monoclonal antibody against the myc-tag (see Material and Methods) directly conjugated to 8-nm colloidal gold.

Fig. 3C and D document that the Nup98 myc-tagged N terminus is found on both the cytoplasmic and the nuclear face of the NPC. As seen with the anti-GLFG antibody, ~70% of the gold particles were found at an average distance of 17.1 (±11.6) nm from the central plane of the NE with corresponding radial distances of 9.8 (±8.4) nm, whereas the remaining ~30% of the gold particles were found on the nuclear side in the area of the nuclear basket. Together our immuno-EM data suggest that Nup98 is anchored within the center of the NPC by its C-terminal domain, whereas its N-terminal GLFG domain exhibits structural flexibility and mobility and can localize to both faces of the NPC.

SIM confirms the central position of Nup98 within the NPC

The recent development of super-resolution microscopy techniques has enabled visualization of structures at a resolution not previously achievable by light microscopy. SIM resolves objects beyond the diffraction limit of the light microscope by imaging the sample illuminated with a very fine pattern in several orientations and phases (Gustafsson et al., 2000; Gustafsson et al., 2008; Heintzmann and Cremer, 1998). High-resolution information is encoded in these images and can be recovered though post-acquisition processing. SIM effectively doubles the resolution of the microscope.

With a potential increase in resolution to 100 nm, the relative positioning of epitopes to cytoplasmic, central, or nucleoplasmic domains along the ~200 nm cytoplasmic-tonucleoplasmic axis of the NPC should now be feasible. We therefore employed SIM to confirm the localization of Nup98 by comparison to nucleoporins well established to associate at the cytoplasmic filaments (Nup358/RanBP2) or nuclear basket (Nup153) of the NPC. To visualize Nup98 in these studies, we used the rat anti-GLFG antibody together with our well-characterized antibody raised against the full Nup98 C-terminal domain (AA506-863; Griffis et al, 2002). Two different reagents were used to image each of the reference nucleoporins, Nup153 and Nup358 (Figure 4A) in combination with the Nup98 antibodies. GFP-Nup358 was shown to functionally complement siRNA-mediated depletion of Nup358, demonstrating proper association of this tagged protein with the NPC (Walde et al., 2011). Each of the antibodies has been previously used in fluorescence and/or electron microscopy to localize the target protein (Arnaoutov et al., 2005; Fahrenkrog et al., 2002; Pante et al., 1994).

Figure 4.

Relative localization of Nup98 within the NPC by SIM. (A) Cartoon depicting domain organization of the nucleoporins used, along with position of epitopes for each antibody. Nup98: blue box within the Nup98 FG/GLFG domain is the binding site for Rae1/Gle2. Red line denotes autoproteolytic site. Nup358: RBD represents Ran binding domains.(B) Comparison of widefield, deconvolved widefield, and SIM images. Nup98 anti-GLFG is shown in red, Nup153 anti-ZnF in green. Scale bar, 5μm. Inset scale bar, 1 μm. (C) Regions of stained nuclear envelopes with dotted line indicating the position of the linescan, displayed to the right of each image. Each panel depicts one pair of fluorescent labels as indicated in the corresponding color on the image. The linescans show the normalized intensity of each channel as a function of distance along the line. The direction of all linescans is cytoplasm to nucleoplasm. In panels a though d, the position of the Nup98 peak was used to align graphs. In panels e-g, graphs were aligned to the position of the 414 peak. Line Scale bar, 1 μm.

Initially, we compared a nucleus stained for Nup98 (anti-GLFG-) and Nup153 (anti-ZnF) imaged by widefield, by widefield followed by deconvolution, or by SIM (Figure 4B). In the widefield image Nup98 and Nup153 appear co-localized and there is significant out of focus background fluorescence. Deconvolution leads to a striking reduction in background fluorescence. SIM yields a similar reduction in background fluorescence, accompanied by an increase in resolution that enables the separation of the signals from the two nucleoporins (Figure 4B, compare magnified panels to the right).

When Nup98 localization was compared to the cytoplasmic filament nucleoporin Nup358, the two were clearly distinguishable and, using either combination of reagents Nup98 was found internally relative to Nup358 (Figure 4C, panels a and b). Similarly, Nup98 was external to the nuclear basket nucleoporin, Nup153 (Figure 4C, panels c and d). These results in position Nup98 between Nup358 and Nup153 in the central region of the NPC, in agreement with the immuno-EM results. For comparison, and to further establish the ability of SIM to resolve the center from the peripheral regions of the NPC, we assessed the relative localization of Nup62, the primary target of the pore-specific monoclonal 414. Nup62 has been shown to associate with the central region of the NPC by immuno-EM (Schwarz-Herion et al., 2007). The 414 signal, although slightly broader in linescans, was resolvable from both Nup358 and Nup153, confirming the central position of Nup62 (Figure 4C, panels e-g). It should be noted that resolution of the central core from the peripheral structures of the pore is near the limit of resolution of this technique. Not every NPC around the periphery of the NE is oriented exactly parallel to the imaging plane; this leads to an apparent shortening of the distance along the C-to-N axis in the imaging plane and results in signals that can not be separated in some NPCs. In contrast, when Nup358 and Nup153 are co-visualized, the greater distance that separates these nucleoporins (~200 nm) is easily resolved regardless of slight variation in the NPC orientation; consequently, Nup358 and Nup153 are clearly distinct in every NPC (Figure 4C, panel h).

Discussion

Previous immuno-EM studies to determine nucleoporin localization within the 3-D architecture of the NPC have frequently utilized antibodies with uncharacterized epitopes, single antibodies or nucleoporins with a tag on one end, which were detected by tag-specific antibodies. Nucleoporins, however, are typically large, multi-domain proteins with a complex domain topology and an astonishing high degree of structural flexibility, especially in case of the FG-repeat nucleoporins. Combinations of domain-specific antibodies against nucleoporins have in the past successfully resolved discrepancies regarding the localization of a number of vertebrate nucleoporins, such as Tpr (Frosst et al., 2002), Nup153 (Fahrenkrog and Aebi, 2003; Fahrenkrog et al., 2002), Nup214 (Paulillo et al., 2005), and the Nup62 complex (Schwarz-Herion et al., 2007). With the present study we have now defined the localization and topology within the NPC of the only vertebrate GLFG nucleoporin, Nup98.

SIM microscopy has increased the resolution of fluorescence light microscopy to an extent that major domains within the NPC structure could potentially be distinguished. Here we have shown that SIM can indeed be used to differentiate the cytoplasmic filaments, central core, and nuclear basket of the NPC. Antibodies to both the N- and C-terminal domains were used to distinguish Nup98 from a nucleoporin on either the cytoplasmic or nuclear face of the NPC, thus positioning Nup98 in the central structure of the pore. As detected by the monoclonal 414, Nup62 was similarly separable from Nup358 and Nup153, confirming its central position and further validating the Nup98 results.

By employing domain-specific antibodies against Nup98 we show here that this nucleoporin contains a stationary anchoring domain and a rather flexible FG domain, similar to other FG nucleoporins, such as Nup153, Nup214 and Nup62 (Fahrenkrog and Aebi, 2003; Fahrenkrog et al., 2002; Paulillo et al., 2005; Schwarz-Herion et al., 2007). Nup98 is anchored in the midplane of the NE by its C-terminal autoproteolytic domain (Fig. 2 A and B). This is consistent with biochemical data that demonstrated that the C-terminal domain of Nup98 interacts with Nup96 within the Nup107-160 complex (Hodel et al., 2002; Vasu et al., 2001), a major building block of the NPC critical for NPC assembly (Harel et al., 2003; Walther et al., 2003). Nup98 and Nup96 arise from a common precursor protein separated by autoproteolytic cleavage (Fontoura et al., 1999). However, even after cleavage the N-terminal domain of Nup96 binds the autoproteolytic domain of Nup98 (Hodel et al., 2002). Nup98 can also be expressed independently of Nup96, from a differently spliced mRNA. This form also undergoes autoproteolytic cleavage to release a ~50 amino acid peptide from the C-terminus. Nup98 proteins generated by these two mechanisms are identical in sequence and are thus expected to exhibit the same interactions with the NPC. In addition to Nup96, the autoproteolytic domain of Nup98 also binds the N-terminal domain of Nup88 (Griffis et al., 2003; Yoshida et al., 2011). Nup88 has recently been shown to reside on both sides of the NPC (Lussi et al., 2011). Taken together, these interactions suggest that Nup98 in its central position is somewhat sandwiched between different nucleoporins, probably bridging distinct NPC subcomplexes.

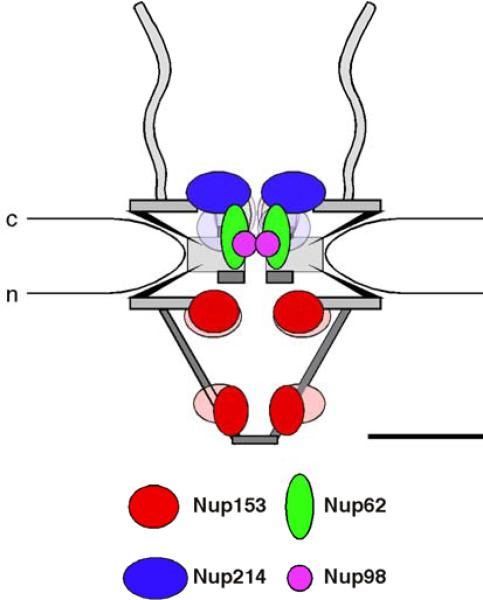

Compared to other FG nucleoporins Nup98 shows the most central anchoring, especially when compared to Nup153 and Nup214, but also with respect to the Nup62 complex (Fig. 5 and Table 1). Differences in anchoring sites around the central region of the NPC are particular interesting with respect to the still critically discussed question of the selective barrier of the NPC.Nup98 is the sole vertebrate GLFG nucleoporin and we show here that the GLFG domain of Nup98 is flexible and exhibits multiple locations within the NPC (Fig. 3). In this respect it is similar to the FxFG repeat domains of Nup153, Nup214 and Nup62 (Fahrenkrog et al., 2002; Paulillo et al., 2005; Schwarz-Herion et al., 2007). However, the range of especially the radial distribution of the GLFG domain of Nup98 is much more limited as compared to the FxFG domains of Nup153 and Nup214. Interestingly, Nup145N, the yeast homologues of Nup98, has recently been shown to adopt a collapsed coil configuration, although its FG region is containing a high content of charged amino acids, which would predict a more extended configuration for this domain (Yamada et al., 2010). The Nup98 GLFG domain may similarly adopt such as collapsed coil configuration, which would explain its limited radial distribution as compared to the FxFG domains of Nup153 and Nup214.

Figure 5.

Schematic representation of the anchoring sites of FG nucleoporins within the 3-D architecture by elliptic location clouds. Nup153 is anchored near the nuclear ring moiety by its N-terminal domain and near the distal ring of the nuclear basket by its zinc-finger domain (Fahrenkrog et al., 2002), while Nup214 is anchored near the cytoplasmic ring moiety by its N-terminal and central domain (Paulillo et al., 2005). Nup62 (Schwarz-Herion et al., 2007) and Nup98 are anchored in the center of the NPC with Nup98 being slightly more central than Nup62. The positions of their respective FG domains are indicated by clouds in the according lighter clours. c, cytoplasm; n, nucleus. Scale bar: 50 nm.

Table 1.

Relative position of anchoring sites for FG nucleoporins within the NPC.

| Vertical | Radial | |

|---|---|---|

| Nup153 N terminus | -26.6 nm (± 9.2 nm) | 18.3 nm (±10.8 nm) |

| Nup153 zinc-finger | -68 nm (±10.8 nm) | 11.1 nm (±7.4 nm) |

| Nup214 | 26 nm (± 9 nm) | 16 nm (± 14 nm) |

| Nup62 | 5.4 nm (± 14.1 nm) | 9.4 nm (±6 nm) |

| Nup98 | 2.9 nm (5.9 nm) | 5.1 nm (+5.4 nm) |

Negative vertical distances correspond to locations on the nuclear side of the NPC, positive vertical distances to locations on the cytoplasmic face. Errors are standard deviations.

FG domains are strongly linked to nucleocytoplasmic transport by providing interaction sites for receptors ferrying cargo through the NPC, while at the same time restricting diffusion of non-specific proteins. A functional difference between F×FG and GLFG domains has long been speculated, and among yeast nucleoporins GLFG repeat domains appear to be more cohesive in nature than FxFG domains (Patel et al., 2007). Several observations implicate Nup98 as constituent of the permeability barrier of the NPC. Nup98 is the first nucleoporin released from the NPC at the start of mitotic breakdown and release may facilitate free exchange of macromolecules between nucleus and cytoplasm (Dultz et al., 2008; Laurell et al., 2011). Further support comes from the observation that the GLFG repeats of Nup98 hinder the diffusion of BSA somewhat more efficiently than do the FxFG repeats of Nup153, whereas both repeat domains allow passage of importin ß at similar rates (Kowalczyk et al., 2011). Moreover, Nup98 is rapidly targeted by polioviruses, and Nup98 degradation coincides with an increase in the permeability barrier of the NPCs (Park et al., 2008). Similarly, nuclei lacking Nup98 allow the influx of 70 kDa dextran which is typically excluded from nuclei with an intact permeability barrier (Laurell et al., 2011). Therefore, Nup98 appears to contribute significantly to the barrier properties of NPCs, a conclusion supported by our immuno-EM data documenting the anchorage of the GLFG domain of Nup98 directly at the center of the NPC.

Acknowledgements

B.F. is very grateful to Ueli Aebi for his faith and continuous support in all the years at the MIH, for being a great scientific advisor, the many creative discussions and for his friendship. The authors thank Ursula Sauder and Vesna Oliveri for expert technical assistance, and acknowledge Nikon Instruments, Inc. (Melville, NY) for providing the Ti-E N-SIM Structured Illumination Super Resolution Microscope System as part of our Partner in Research agreement. This worked was supported by research grants to B.F. from the Swiss National Science Foundation and the FNRS Belgium, by the M.E. Müller Foundation and the Kanton Basel Stadt, by the Microcopy Core of the Emory Neuroscience NINDS Core Facilities grant, P30NS055077, and by National Institutes of Health, RO1 GM-059975 to M.A.P.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Arnaoutov A, Azuma Y, Ribbeck K, Joseph J, Boyarchuk Y, Karpova T, McNally J, Dasso M. Crm1 is a mitotic effector of Ran-GTP in somatic cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:626–632. doi: 10.1038/ncb1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayliss R, Littlewood T, Stewart M. Structural basis for the interaction between FxFG nucleoporin repeats and importin-beta in nuclear trafficking. Cell. 2000;102:99–108. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00014-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck M, Lucic V, Forster F, Baumeister W, Medalia O. Snapshots of nuclear pore complexes in action captured by cryo-electron tomography. Nature. 2007;449:611–615. doi: 10.1038/nature06170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blevins MB, Smith AM, Phillips EM, Powers MA. Complex formation among the RNA export proteins Nup98, Rae1/Gle2, and TAP. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:20979–20988. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302061200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capelson M, Liang Y, Schulte R, Mair W, Wagner U, Hetzer MW. Chromatin-bound nuclear pore components regulate gene expression in higher eukaryotes. Cell. 2010;140:372–383. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.12.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross MK, Powers MA. Nup98 regulates bipolar spindle assembly through association with microtubules and opposition of MCAK. Mol Biol Cell. 2011;22:661–672. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-06-0478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Angelo MA, Hetzer MW. Structure, dynamics and function of nuclear pore complexes. Trends Cell Biol. 2008;18:456–466. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2008.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denning DP, Patel SS, Uversky V, Fink AL, Rexach M. Disorder in the nuclear pore complex: the FG repeat regions of nucleoporins are natively unfolded. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:2450–2455. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0437902100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dultz E, Zanin E, Wurzenberger C, Braun M, Rabut G, Sironi L, Ellenberg J. Systematic kinetic analysis of mitotic dis- and reassembly of the nuclear pore in living cells. J Cell Biol. 2008;180:857–865. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200707026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahrenkrog B, Aebi U. The nuclear pore complex: nucleocytoplasmic transport and beyond. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:757–766. doi: 10.1038/nrm1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahrenkrog B, Maco B, Fager AM, Koser J, Sauder U, Ullman KS, Aebi U. Domain-specific antibodies reveal multiple-site topology of Nup153 within the nuclear pore complex. J Struct Biol. 2002;140:254–267. doi: 10.1016/s1047-8477(02)00524-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldherr CM, Akin D. The location of the transport gate in the nuclear pore complex. J Cell Sci. 1997;110(Pt 24):3065–3070. doi: 10.1242/jcs.110.24.3065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiserova J, Kiseleva E, Goldberg MW. Nuclear envelope and nuclear pore complex structure and organization in tobacco BY-2 cells. Plant J. 2009;59:243–255. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.03865.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiserova J, Richards SA, Wente SR, Goldberg MW. Facilitated transport and diffusion take distinct spatial routes through the nuclear pore complex. J Cell Sci. 2010;123:2773–2780. doi: 10.1242/jcs.070730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontoura BM, Blobel G, Matunis MJ. A conserved biogenesis pathway for nucleoporins: proteolytic processing of a 186-kilodalton precursor generates Nup98 and the novel nucleoporin, Nup96. J Cell Biol. 1999;144:1097–1112. doi: 10.1083/jcb.144.6.1097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontoura BM, Blobel G, Yaseen NR. The nucleoporin Nup98 is a site for GDP/GTP exchange on ran and termination of karyopherin beta 2-mediated nuclear import. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:31289–31296. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004651200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frenkiel-Krispin D, Maco B, Aebi U, Medalia O. Structural analysis of a metazoan nuclear pore complex reveals a fused concentric ring architecture. J Mol Biol. 2009;395:578–586. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fried H, Kutay U. Nucleocytoplasmic transport: taking an inventory. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2003;60:1659–1688. doi: 10.1007/s00018-003-3070-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frosst P, Guan T, Subauste C, Hahn K, Gerace L. Tpr is localized within the nuclear basket of the pore complex and has a role in nuclear protein export. J Cell Biol. 2002;156:617–630. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200106046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuhara T, Ozaki T, Shikata K, Katahira J, Yoneda Y, Ogino K, Tachibana T. Specific monoclonal antibody against the nuclear pore complex protein, nup98. Hybridoma (Larchmt) 2005;24:244–247. doi: 10.1089/hyb.2005.24.244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffis ER, Xu S, Powers MA. Nup98 localizes to both nuclear and cytoplasmic sides of the nuclear pore and binds to two distinct nucleoporin subcomplexes. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14:600–610. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-09-0582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffis ER, Altan N, Lippincott-Schwartz J, Powers MA. Nup98 is a mobile nucleoporin with transcription-dependent dynamics. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:1282–1297. doi: 10.1091/mbc.01-11-0538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffis ER, Craige B, Dimaano C, Ullman KS, Powers MA. Distinct functional domains within nucleoporins Nup153 and Nup98 mediate transcription-dependent mobility. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:1991–2002. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-10-0743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafsson MG, Agard DA, Sedat JW. Doubling the lateral resolution of wide-field fluorescence microscopy using structured illumination. Proc SPIE. 2000;3919:141–150. [Google Scholar]

- Gustafsson MG, Shao L, Carlton PM, Wang CJ, Golubovskaya IN, et al. Three-dimensional resolution doubling in wide-field fluorescence microscopy by structured illumination. Biophys J. 2008;94:4957–4970. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.120345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harel A, Orjalo AV, Vincent T, Lachish-Zalait A, Vasu S, Shah S, Zimmerman E, Elbaum M, Forbes DJ. Removal of a single pore subcomplex results in vertebrate nuclei devoid of nuclear pores. Mol Cell. 2003;11:853–864. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00116-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heintzmann R, Cremer C. Laterally modulated excitation microscopy: improvement of resolution by using a diffraction grating. Proc SPIE. 1998;3568:185–195. [Google Scholar]

- Hodel AE, Hodel MR, Griffis ER, Hennig KA, Ratner GA, Xu S, Powers MA. The three-dimensional structure of the autoproteolytic, nuclear pore-targeting domain of the human nucleoporin Nup98. Mol Cell. 2002;10:347–358. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00589-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeganathan KB, Malureanu L, van Deursen JM. The Rae1-Nup98 complex prevents aneuploidy by inhibiting securin degradation. Nature. 2005;438:1036–1039. doi: 10.1038/nature04221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalverda B, Pickersgill H, Shloma VV, Fornerod M. Nucleoporins directly stimulate expression of developmental and cell-cycle genes inside the nucleoplasm. Cell. 2010;140:360–371. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keminer O, Siebrasse JP, Zerf K, Peters R. Optical recording of signal-mediated protein transport through single nuclear pore complexes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:11842–11847. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.21.11842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowalczyk SW, Kapinos L, Blosser TR, Magalhaes T, van Nies P, Lim RY, Dekker C. Single-molecule transport across an individual biomimetic nuclear pore complex. Nat Nanotechnol. 2011;6:433–438. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2011.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurell E, Beck K, Krupina K, Theerthagiri G, Bodenmiller B, Horvath P, Aebersold R, Antonin W, Kutay U. Phosphorylation of Nup98 by multiple kinases is crucial for NPC disassembly during mitotic entry. Cell. 2011;144:539–550. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim RY, Fahrenkrog B. The nuclear pore complex up close. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2006;18:342–347. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2006.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim RY, Aebi U, Fahrenkrog B. Towards reconciling structure and function in the nuclear pore complex. Histochem Cell Biol. 2008;129:105–116. doi: 10.1007/s00418-007-0371-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lussi YC, Hugi I, Laurell E, Kutay U, Fahrenkrog B. The nucleoporin Nup88 is interacting with nuclear lamin A. Mol Biol Cell. 2011;22:1080–1090. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-05-0463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohr D, Frey S, Fischer T, Guttler T, Gorlich D. Characterisation of the passive permeability barrier of nuclear pore complexes. Embo J. 2009;28:2541–2553. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naim B, Brumfeld V, Kapon R, Kiss V, Nevo R, Reich Z. Passive and facilitated transport in nuclear pore complexes is largely uncoupled. J Biol Chem. 2007;2820:3881–3888. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608329200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oka M, Asally M, Yasuda Y, Ogawa Y, Tachibana T, Yoneda Y. The mobile FG nucleoporin Nup98 is a cofactor for Crm1-dependent protein export. Mol Biol Cell. 2010;21:1885–1896. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E09-12-1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pante N, Bastos R, McMorrow I, Burke B, Aebi U. Interactions and three-dimensional localization of a group of nuclear pore complex proteins. J Cell Biol. 1994;126:603–617. doi: 10.1083/jcb.126.3.603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park N, Katikaneni P, Skern T, Gustin KE. Differential targeting of nuclear pore complex proteins in poliovirus-infected cells. J Virol. 2008;82:1647–1655. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01670-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel SS, Belmont BJ, Sante JM, Rexach MF. Natively unfolded nucleoporins gate protein diffusion across the nuclear pore complex. Cell. 2007;129:83–96. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulillo SM, Powers MA, Ullman KS, Fahrenkrog B. Changes in nucleoporin domain topology in response to chemical effectors. J Mol Biol. 2006;363:39–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulillo SM, Phillips EM, Koser J, Sauder U, Ullman KS, Powers MA, Fahrenkrog B. Nucleoporin domain topology is linked to the transport status of the nuclear pore complex. J Mol Biol. 2005;351:784–798. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.06.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers MA, Macaulay C, Masiarz FR, Forbes DJ. Reconstituted nuclei depleted of a vertebrate GLFG nuclear pore protein, p97, import but are defective in nuclear growth and replication. J Cell Biol. 1995;128:721–736. doi: 10.1083/jcb.128.5.721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers MA, Forbes DJ, Dahlberg JE, Lund E. The vertebrate GLFG nucleoporin, Nup98, is an essential component of multiple RNA export pathways. J Cell Biol. 1997;136:241–250. doi: 10.1083/jcb.136.2.241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard CE, Fornerod M, Kasper LH, van Deursen JM. RAE1 is a shuttling mRNA export factor that binds to a GLEBS-like NUP98 motif at the nuclear pore complex through multiple domains. J Cell Biol. 1999;145:237–254. doi: 10.1083/jcb.145.2.237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radu A, Moore MS, Blobel G. The peptide repeat domain of nucleoporin Nup98 functions as a docking site in transport across the nuclear pore complex. Cell. 1995;81:215–222. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90331-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenblum JS, Blobel G. Autoproteolysis in nucleoporin biogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:11370–11375. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.20.11370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz TU. Modularity within the architecture of the nuclear pore complex. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2005;15:221–226. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2005.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz-Herion K, Maco B, Sauder U, Fahrenkrog B. Domain Topology of the p62 Complex Within the 3-D Architecture of the Nuclear Pore Complex. J Mol Biol. 2007;370:796–806. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slot JW, Geuze HJ. A new method of preparing gold probes for multiple-labeling cytochemistry. Eur J Cell Biol. 1985;38:87–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terry LJ, Wente SR. Nuclear mRNA export requires specific FG nucleoporins for translocation through the nuclear pore complex. J Cell Biol. 2007;178:1121–1132. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200704174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasu S, Shah S, Orjalo A, Park M, Fischer WH, Forbes DJ. Novel vertebrate nucleoporins Nup133 and Nup160 play a role in mRNA export. J Cell Biol. 2001;155:339–354. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200108007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walde S, Kehlenbach RH. The Part and the Whole: functions of nucleoporins in nucleocytoplasmic transport. Trends Cell Biol. 2011;20:461–469. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walde S, Thakar K, Hutten S, Spillner C, Nath A, Rothbauer U, Wiemann S, Kehlenbach RH. The nucleoporin Nup358/RanBP2 promotes nuclear import in a cargo- and transport receptor-specific manner. Traffic. 2011 doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2011.01302.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walther TC, Alves A, Pickersgill H, Loiodice I, Hetzer M, Galy V, Hulsmann BB, Kocher T, Wilm M, Allen T, Mattaj IW, Doye V. The conserved Nup107-160 complex is critical for nuclear pore complex assembly. Cell. 2003;113:195–206. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00235-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada J, Phillips JL, Patel S, Goldfien G, Calestagne-Morelli A, Huang H, Reza R, Acheson J, Krishnan VV, Newsam S, Gopinathan A, Lau EY, Colvin ME, Uversky VN, Rexach MF. A bimodal distribution of two distinct categories of intrinsically disordered structures with separate functions in FG nucleoporins. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2010;9:2205–2224. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M000035-MCP201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida K, Seo HS, Debler EW, Blobel G, Hoelz A. Structural and functional analysis of an essential nucleoporin heterotrimer on the cytoplasmic face of the nuclear pore complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:16571–16576. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1112846108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zolotukhin AS, Felber BK. Nucleoporins nup98 and nup214 participate in nuclear export of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Rev. J Virol. 1999;73:120–127. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.1.120-127.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]