Abstract

Purpose

To examine the association between waist circumference (WC) and body mass index (BMI) on disability among older adults from Latin America and the Caribbean.

Methods

Cross-sectional, multicenter city study of 5,786 subjects aged 65 years and older from the Health, Well-Being and Aging in Latin America and the Caribbean Study (SABE) (1999-2000). Sociodemographic variables, smoking status, medical conditions, BMI, WC, and activities of daily living (ADL) were obtained.

Results

Prevalence of high WC (>88 cm) in women ranged from 48.5% (Havana) to 72.7% (Mexico City), while among men (>102 cm) it ranged from 12.5% (Bridgetown) to 32.5% (Santiago). The associations between WC and ADL disability were “J” shaped, with higher risks of ADL disability observed above 110 cm for women in Bridgetown, Santiago, Havana, and Montevideo. The association in Sao Paulo is plateau with higher risk above 100 cm, and the association in Mexico City is closer to linear. Among men the associations were “U” (Bridgetown, Sao Paulo, and Havana), “J” shaped (Montevideo), plateau (Santiago), and closer to linear in Mexico City (Figure 3). When WC and BMI were analyzed together, we found that participants from Sao Paolo, Santiago, Havana, and Montevideo in the overweight or obese category with high WC were significantly more likely to report ADL disability after adjusting for all covariates.

Conclusion

The findings of this study suggests that both general and abdominal adiposity are associated with disability and support the use of WC in addition to BMI to assess risk of disability in older adults.

Keywords: Obesity, body mass index, waist circumference, disability, older adults, Latin America, the Caribbean

1. Introduction

The proportion of older adults has been growing dramatically in the Latin American and Caribbean (LAC) countries during the few decades, and this region now has one of the most rapidly aging populations in the developing nations (Filozof et al., 2001; Santos et al., 2004). The percentage of individuals 65 years and over in the region is projected to increase from 13.9% in 2020 to 25.6% in 2040 (Kinsell k & He W, 2009). The increase in the prevalence of obesity in this aging population is a public health concern, not only in these developing countries but also in developed countries (Filozof et al., 2001). The prevalence of obesity in LAC countries when assessed by body mass index (BMI), calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared, ranges from 13.3% to 37.6% (Al Snih et al., 2010). The rise of this trend towards obesity is expected to cause a subsequent increase in many chronic diseases, which in turn would result in an increase in disability rates (Guallar-Castillon et al., 2007; Uauy, Albala, & Kain, 2001).

Several studies have shown that body composition changes with aging, as evidenced by an increase in fat mass and a decrease in muscle mass (Villareal et al., 2005; Zamboni et al., 2005); and that aging is associated with fat redistribution, indicated by an increase in visceral fat and a decrease in subcutaneous fat in the abdomen, thighs and calves (Zamboni et al., 2005). BMI has often been criticized as an inadequate measure of obesity among older adults due to these age-related changes in body composition (Villareal et al., 2005; Zamboni et al., 2005). Waist circumference (WC), a measure of visceral fatness, has been recommended as a better predictor of obesity in older adults (Chen & Guo, 2008; Guallar-Castillon et al., 2007; Visscher et al., 2001).

Several studies have compared the individual and combined effect of BMI and WC on health outcomes in older adults (Angleman et al., 2006; Guallar-Castillon et al., 2007; Jacobs et al., 2010; Janssen et al., 2005). Findings from the Cardiovascular Health Study showed that WC was a positive predictor of mortality independent of BMI (Janssen et al., 2005). Similarly, Jacobs et al., using the Cancer Prevention Study II Nutrition Cohort, found that within all categories of BMI, higher WC was positively associated with mortality (Jacobs et al., 2010). Barcelo et al. reported that WC was more clearly associated than BMI with prevalence of diabetes (Barcelo et al., 2007). Cross-sectional and longitudinal studies have shown that WC is a better predictor of disability than BMI. For example, in a prospective cohort study of elderly Spanish individuals, WC was a better 2-year predictor of disability, independent of BMI (Guallar-Castillon et al., 2007). Angleman et al. found that WC was the best predictor of disability outcomes compared with BMI, weight, hip circumference and waist-hip ratio (Angleman et al., 2006).

Current guidelines with respect to obesity recommend measuring WC in persons with a BMI between 25 and 35 kg/m2 using the cutoff points of 102 cm in men and 88 cm in women to define abdominal obesity and identify persons at risk for disease (National Heart, 2002). Little is known about the association between high WC and disability among older adults in Latin America and the Caribbean. The objectives of this study are to investigate the association between high waist circumference and disability, and the association of the combined effect of BMI and WC on disability among older adults from six Latin American cities participating in the Health, Well-Being and Aging in Latin America and the Caribbean (SABE) study.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Sample

We examined data from the Health, Well-Being and Aging in Latin America and the Caribbean Study (SABE) (Albala et al., 2005). The SABE study is a cross-sectional representative survey of non-institutionalized older adults living in Buenos Aires (Argentina), Bridgetown (Barbados), Sao Paulo (Brazil), Santiago (Chile), Havana (Cuba), Mexico City (Mexico) and Montevideo (Uruguay) (Palloni et al., 2002; Peláez M, 2003). Participants were selected based on a multistage cluster sampling design. In each city, the primary sampling unit (PSU) was a cluster of independent households within predetermined geographic areas. In all countries, except Barbados and Brazil, the sample was chosen in three selection stages. In Barbados and Brazil, two selection stages were used. Each sample consisted of between 1,500 and 2,000 individuals aged 60 and older and their spouses. In total, 10,970 elderly men and women were interviewed during 1999-2000. The objective of SABE was to produce databases to evaluate demographic, socioeconomic and health variables related to the emerging older population. Participants from Argentina were not included in our analyses since anthropometric measures (BMI and WC) were not collected. The response rate for the countries varied from 65.3% in Montevideo to 95.3% in Havana, and the percentage of interviews completed by a proxy varied from 1.4% in Montevideo to 13.1% in Sao Paulo (Palloni et al., 2002).

We analyzed data from the SABE study for six countries and for subjects 65 years and older (N = 5,786). We included participants with complete measures of disability, BMI, WC, and relevant covariates. From the 7,371 interviewed 1,585 participants were excluded: 1,236 had missing information on BMI or a BMI <18.5 kg/m2, 68 had missing data on WC or WC <50 cm or WC >140 cm, and 281 had missing information on covariates. The 1,585 participants excluded were older, more likely to be female or unmarried, current smokers, subjects who had had a stroke or had ADL disability.

The final number of samples included in the analyses was 994 (Bridgetown), 1,285 (Sao Paulo), 844 (Santiago), 1,073 (Havana), 675 (Mexico City) and 915 (Montevideo), for a total of 5,786 participants (Women=3,648 and Men=2,138).

2.2. Measurements

2.2.1. Disability

Disability was assessed using the Katz Activities of Daily Living (ADL) scale (Katz et al., 1963). Interviewers asked if participants experienced difficulty or needed assistance performing the following activities: walking across a small room, bathing, dressing, eating, getting in and out of the bed, and using the toilet. ADL limitations were dichotomized as having difficulty or no difficulty in performing one or more of the six activities.

2.2.2. Body Mass Index (BMI)

BMI was computed by dividing weight in kilograms by height in meters squared (kg/m2). BMI was grouped according to the following standards of the National Institute of Health (NIH) (National Heart, 2002): (<18.5 = underweight, 18.5–24.9 = normal weight, 25.0–29.9 = overweight, 30.0–34.9 = obesity category I, 35.0–39.9 = obesity category II, and ≥40.0 = extreme obesity). For the analyses, a BMI of 18.5 to 24.9 kg/m2 (normal weight) was used as the reference category.

2.2.3. Waist circumference (WC)

WC was measured at the level of the umbilicus (i.e., belly button) with the subject standing and wearing no more than one layer of outer clothing, using a non-stretchable measuring tape and recorded in centimeters to the nearest millimeter. WC was dichotomized according to NIH recommendations (men, low WC ≤102 cm and high WC >102 cm; women, low ≤88 cm and high WC >88 cm) (National Heart, 2002).

2.2.4. Covariates

Sociodemographic variables included age (continuous), gender, years of formal education (continuous) and marital status (married = 1, not married/widowed/separated = 0). Smoking status was assessed by asking whether participants were current smokers, former smokers or never smokers. The presence of medical conditions was assessed by asking if participants had ever been told by a doctor or nurse that they had arthritis, diabetes, heart attack, hypertension, stroke or cancer.

2.2.5. Statistical Analysis

Participant characteristics were stratified by country and gender, and examined using descriptive statistics. Univariate comparisons based on continuous variables were conducted with one-way analysis of variance and comparisons involving categorical variables with chi-square tests. Participants were grouped into six categories according to BMI and WC (low or high). Normal BMI (18.5 to <25 kg/m2 and low WC (≤102 cm in men and ≤88 cm in women) or high WC (≥102 cm in men and ≥88 cm in women); overweight (BMI of 25 to <30 kg/m2) and low or high WC; and obesity (BMI ≥30 kg/m2) and low or high WC.

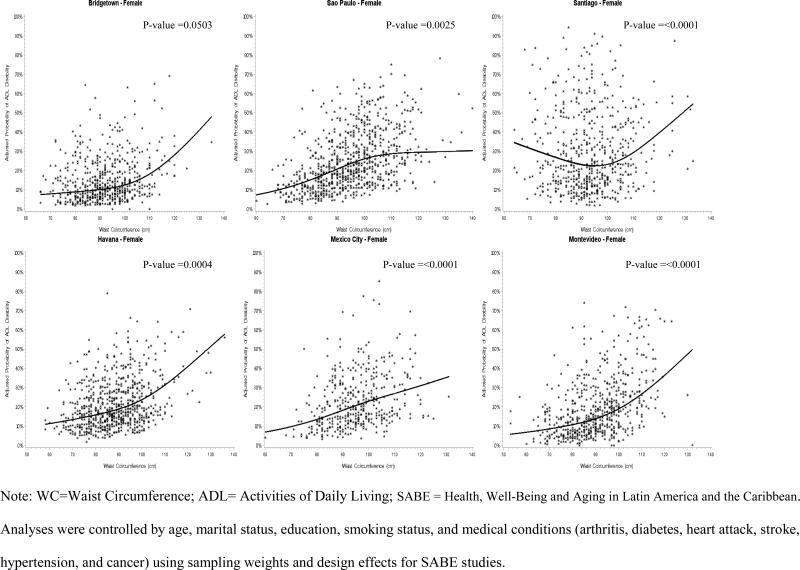

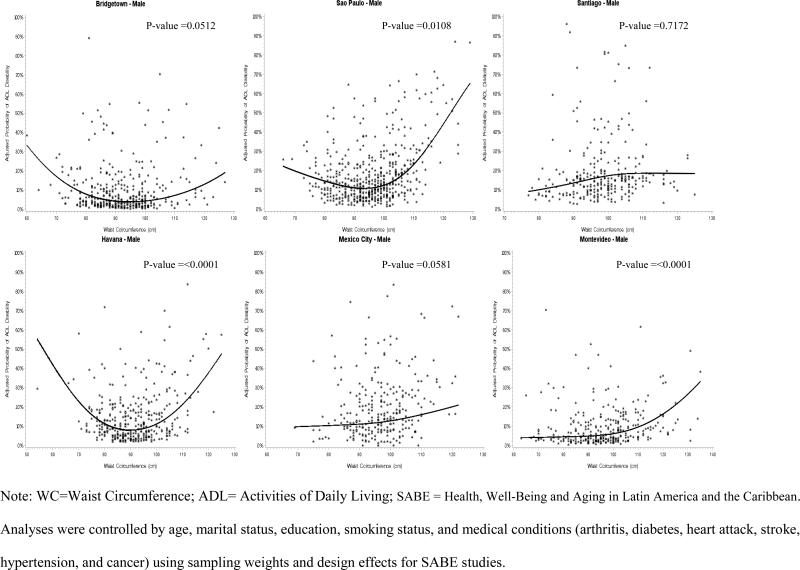

We examined the association between WC and ADL disability after controlling for all covariates by weighted logistic regression models with restricted cubic splines using three knots (Figure 2 and 3) (Marsh, 1986; Marsh & Cormier, 2001). This method is more flexible in estimating nonlinear association between WC and ADL disability (Marsh, 1986; Marsh & Cormier, 2001). The log likelihood ratio test was used to examine whether each cubic spline significantly predict ADL disability by country and gender.

Figure 2.

Adjusted probability of ADL disability as a function of WC for older women living in Latin American and the Caribbean (N =3648).

Figure 3.

Adjusted probability of ADL disability as a function of WC for older men living in Latin American and the Caribbean (N =2138).

Weighted logistic regression analysis was used to investigate the association between BMI and WC with ADL disability for each country. Two models were performed. Model 1 included BMI + WC, age and gender; and Model 2 included marital status, education, smoking status and medical conditions along with variables included in Model 1. Interaction effect analyses between BMI and WC, and BMI, WC, and gender were performed All analyses were performed using the SAS for Windows 9.2 survey procedures (PROC SURVEYFREQ, PROC SURVEYLOGIST) (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) to account for design effects and sampling weight in the SABE Study.

3. Results

Table 1 presents the descriptive characteristics for older women by WC (low ≤ 88 and high > 88 cm) for each city. The prevalence of high WC ranged from 48.5% (Havana) to 72.7% (Mexico City). Women with high WC were younger than those with low WC across all cities. Women from Mexico City and Montevideo who had high WC were significantly more likely to have lower level of education, and those from Havana and Montevideo were significantly more likely to be married when compared with those with low WC. The prevalence of ADL disability among those with high WC ranged from 15.7% (Bridgetown) to 28.3% (Santiago). The mean of BMI ranged from 28.9 kg/m2 (Havana) to 31.2 kg/m2 (Bridgetown and Montevideo), and the mean of WC ranged from 97.9 cm (Havana) to 101.6 cm (Sao Paulo) among those with high WC. Obesity (BMI ≥30 kg/m2) was prevalent among all women with high WC. Arthritis, diabetes, and hypertension were significantly more likely to be reported among those with high WC when compared with those with low WC.

Table 1.

Descriptive characteristics for older female living in Latin America and the Caribbean by waist circumference (WC) (N =3648)

| Variables | Bridgetown N= 601 n (%) | Sao Paulo N=768 n (%) | Santiago N=563 n (%) | Havana N=718 n (%) | Mexico City N=411 n (%) | Montevideo N=587 n (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | High | Low | High | Low | High | Low | High | Low | High | Low | High | |

| Total | 222 (37.0) | 379 (63.0)* | 253 (34.8) | 515 (65.2) | 186 (35.7) | 377 (64.3) | 369 (51.5) | 348 (48.5) | 109 (27.3) | 302 (72.7) | 258 (41.6) | 329 (58.4) |

| Age (years), Mean (SE) | 76.0 (0.5) | 74.1 (0.3)† | 72.3 (0.5) | 72.8 (0.4) | 74.2 (0.5) | 73.8 (0.5) | 75.8 (0.5) | 73.3 (0.4)* | 73.5 (0.7) | 73.2 (0.4) | 74.5 (0.5) | 72.5 (0.3)† |

| Education (years), Mean (SE) | 5.1 (0.2) | 5.2 (0.2) | 3.0 (0.3) | 2.5 (0.2) | 6.3 (0.6) | 5.4 (0.6) | 6.2 (0.2) | 6.5 (0.2) | 4.6 (0.4) | 3.5 (0.2)‡ | 6.1 (0.3) | 5.7 (0.3)* |

| Married marital status (married) | 55 (24.6) | 86 (22.6) | 91 (42.8) | 164 (33.7) | 44 (38.0) | 101 (37.8) | 41 (11.1) | 66 (19.5)† | 37 (34.2) | 102 (34.0) | 66 (25.8) | 119 (35.7)‡ |

| Smoking status | † | |||||||||||

| Never | 202 (91.0) | 346 (91.3) | 192 (74.1) | 384 (72.0) | 121 (64.9) | 248 (66.2) | 252 (66.7) | 238 (67.7) | 83 (75.4) | 244 (80.7) | 202 (79.8) | 250 (76.7) |

| Former | 20 (9.0) | 29 (7.6) | 30 (11.5) | 96 (20.1) | 43 (26.0) | 108 (28.0) | 49 (14.2) | 61 (18.0) | 17 (16.0) | 43 (14.3) | 29 (11.8) | 57 (16.7) |

| Current | 0 (0.0) | 4 (1.1) | 31 (14.3) | 35 (7.9) | 22 (9.1) | 21 (5.8) | 68 (19.1) | 50 (14.3) | 9 (8.6) | 15 (5.0) | 27 (8.5) | 22 (6.6) |

| BMI (kg/m2), Mean (SE) | 24.1 (0.3) | 31.2 (0.4)* | 23.4 (0.1) | 29.7 (0.3)* | 24.5 (0.4)* | 30.5 (0.4) | 23.2 (0.2) | 28.9 (0.4)* | 23.6 (0.2) | 29.9 (0.2)* | 28.8 (0.4) | 31.2 (0.4)* |

| BMI (kg/m2) category | * | * | * | * | * | † | ||||||

| 18.5 - <25 | 146 (66.1) | 40 (10.7) | 3 (3.2) | 50 (9.9) | 99 (51.4) | 26 (6.4) | 257 (71.4) | 48 (12.8) | 73 (67.9) | 28 (9.5) | 80 (28.4) | 49 (15.2) |

| 25- <30 | 58 (25.9) | 143 (37.8) | 79 (51.9) | 230 (42.8) | 78 (43.9) | 159 (42.2) | 98 (25.3) | 176 (49.6) | 36 (32.1) | 128 (42.7) | 83 (33.5) | 99 (28.5) |

| ≥30 | 18 (8.0) | 196 (51.5) | 53 (44.9) | 235 (47.3) | 9 (4.7) | 192 (51.4) | 14 (3.2) | 125 (37.6) | 0 (0.0) | 146 (47.8) | 95 (38.0) | 181 (56.3) |

| WC (cm), Mean (SE) | 81.3 (0.3) | 98.7 (0.4)* | 80.8 (0.4) | 101.6 (0.6)* | 81.4 (0.5)* | 99.5 (1.0) | 79.2 (0.3) | 97.9 (0.4)* | 82.0 (0.5) | 100.0 (0.5)* | 78.9 (0.5) | 99.5 (0.5)* |

| Any ADL limitation | 31 (14.2) | 59 (15.7) | 41 (14.2) | 143 (25.1)† | 53 (26.2) | 121 (28.3) | 72 (18.2) | 81 (23.6) | 17 (17.1) | 73 (25.5) | 39 (14.7) | 72 (24.1)‡ |

| Medical conditions | ||||||||||||

| Arthritis | 113 (51.1) | 248 (65.5)† | 92 (37.0) | 253 (48.7)† | 70 (37.2) | 173 (47.1)‡ | 230 (60.5) | 258 (73.1)† | 39 (36.7) | 98 (32.3) | 126 (52.1) | 196 (59.7)‡ |

| Diabetes | 36 (16.3) | 104 (27.5)† | 30 (11.8) | 116 (23.1)† | 18 (8.8) | 60 (16.9)‡ | 56 (16.5) | 92 (25.8)‡ | 20 (17.5) | 65 (21.1) | 26 (11.4) | 58 (18.3)‡ |

| Hypertension | 109 (48.8) | 225 (59.3)‡ | 124 (46.8) | 339 (65.8)† | 97 (46.3) | 225 (59.8)† | 153 (42.4) | 196 (55.8)† | 51 (46.8) | 168 (55.6) | 101 (39.7) | 186 (56.9)† |

| Stroke | 9 (4.2) | 23 (6.1) | 8 (3.2) | 32 (5.8) | 11 (6.0) | 23 (6.5) | 32 (8.9) | 35 (9.9) | 7 (6.5) | 19 (6.7) | 11 (4.4) | 6 (1.7) |

| Heart attack | 22 (9.9) | 53 (13.9) | 45 (15.4) | 128 (24.3)‡ | 68 (37.5) | 139 (35.6) | 89 (23.4) | 118 (34.6)† | 12 (11.5) | 36 (12.0) | 66 (28.7) | 73 (22.1) |

| Cancer | 5 (2.1) | 15 (3.9) | 9 (2.4) | 21 (4.0) | 10 (6.3) | 17 (4.4) | 18 (5.1) | 6 (1.7)‡ | 3 (2.8) | 5 (1.5) | 17 (6.8) | 19 (6.3) |

Note: Low WC ≤ 88 cm and High WC > 88 cm. Means and Percents were obtained after adjusting for sampling weights and design effects used in SABE study

P-value <0.0001

p-value < 0.001

p-value < 0.01

P-values denote differences between subjects with low and high waist circumference for each SABE study

ADL = Activities of Daily Living; SABE = Health, Well-Being and Aging in Latin America and the Caribbean; BMI = Body Mass Index

Table 2 presents the descriptive characteristics for older men by WC (low ≤ 102 and high > 102 cm) for each city. The prevalence of high WC ranged from 12.5% (Bridgetown) to 32.5% (Santiago). The prevalence of ADL disability among those with high WC ranged from 14.3% (Bridgetown) to 27.3% (Santiago). The mean of BMI ranged from 27.2 kg/m2 (Montevideo) to 31.4 kg/m2 (Bridgetown), and the mean of WC ranged from 101.6 cm (Sao Paulo) to 112.7 cm (Montevideo) among those with high WC. Obesity (BMI ≥30 kg/m2) was prevalent among all men with high WC. Men from Sao Paulo with high WC were significantly more likely to report diabetes, and men in Santiago and Havana were significantly more likely to report hypertension when compared with those with low WC.

Table 2.

Descriptive characteristics for older male living in Latin America and the Caribbean by waist circumference (WC) (N=2138)

| Variables | Bridgetown N= 393 n (%) | Sao Paulo N=517 n (%) | Santiago N=281 n (%) | Havana N=355 n (%) | Mexico City N=264 n (%) | Montevideo N=328 n (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | High | Low | High | Low | High | Low | High | Low | High | Low | High | |

| Total | 343 (87.5) | 50 (12.5)* | 382 (75.0) | 135 (25.0)* | 192 (67.5) | 89 (32.5)* | 302 (84.8) | 53 (15.2)* | 197 (74.2) | 67 (25.8)* | 242 (73.4) | 86 (26.6)* |

| Age (years), Mean (SE) | 74.1 (0.4) | 73.0 (0.8) | 72.5 (0.5) | 72.0 (0.9) | 73.3 (0.7) | 72.4 (0.6) | 73.8 (0.4) | 72.4 (0.8) | 72.5 (0.4) | 72.6 (0.7) | 72.5 (0.4) | 72.9 (0.7) |

| Education (years), Mean (SE) | 5.1 (0.2) | 6.7 (0.6) | 3.5 (0.3) | 3.8 (0.5) | 7.3 (0.9) | 6.1 (0.7) | 7.2 (0.3) | 7.4 (0.5) | 5.4 (0.4) | 4.8 (0.7) | 6.4 (0.3) | 5.8 (0.2) |

| Married marital status (married) | 183 (52.8) | 28 (56.2) | 288 (80.5) | 97 (74.9) | 131 (75.5) | 61 (77.0) | 179 (59.2) | 37 (72.8) | 143 (73.8) | 46 (71.6) | 171 (71.0) | 57 (68.8) |

| Smoking status | ‡ | |||||||||||

| Never | 149 (43.6) | 20 (40.4) | 104 (24.7) | 38 (29.0) | 73 (37.6) | 38 (40.8) | 79 (24.9) | 16 (31.9) | 56 (26.8) | 21 (30.1) | 65 (25.5) | 18 (22.4) |

| Former | 146 (42.4) | 26 (51.7) | 205 (53.4) | 86 (61.3) | 85 (42.3) | 46 (49.0) | 101 (36.0) | 20 (40.2) | 78 (39.5) | 30 (44.8) | 129 (51.5) | 53 (57.4) |

| Current | 48 (14.0) | 4 (7.9) | 73 (21.9) | 11 (9.7) | 34 (20.1) | 5 (10.3) | 122 (39.1) | 17 (27.9) | 63 (33.7) | 16 (25.1) | 48 (22.0) | 15 (19.9) |

| BMI (kg/m2), Mean (SE) | 25.0 (0.3) | 31.4 (0.9)* | 24.2 (0.2) | 29.4 (0.3)* | 25.4 (0.3)* | 30.7 (0.5) | 23.1 (0.2) | 28.8 (0.5)* | 25.2 (0.2) | 30.9 (0.2)* | 25.8 (0.3) | 27.2 (0.6) |

| BMI (kg/m2) category | * | * | * | * | * | † | ||||||

| 18.5 - <25 | 205 (60.3) | 1 (2.2) | 214 (49.9) | 3 (3.2) | 75 (35.9) | 2 (2.8) | 215 (71.5) | 2 (6.0) | 79 (38.3) | 1 (1.5) | 100 (41.0) | 32 (33.5) |

| 25- <30 | 112 (32.0) | 24 (47.1) | 160 (47.4) | 79 (51.9) | 106 (55.1) | 34 (34.2) | 78 (25.6) | 33 (61.1) | 105 (55.0) | 25 (37.5) | 98 (42.4) | 26 (29.2) |

| ≥30 | 26 (7.7) | 25 (50.7) | 8 (2.7) | 53 (45.0) | 11 (9.0) | 53 (63.0) | 9 (2.9) | 18 (32.8) | 13 (6.7) | 41 (61.0) | 44 (16.6) | 28 (37.3) |

| WC (cm), Mean (SE) | 89.3 (0.4) | 110.8 (1.0)* | 91.9 (0.5) | 101.6 (0.6)* | 93.9 (0.5) | 108.8 (0.7)* | 88.1 (0.5) | 108.5 (0.8)* | 93.1 (0.5) | 108.5(0.7)* | 90.1 (0.6) | 112.7 (1.1)* |

| Any ADL limitation | 30 (8.9) | 7 (14.3) | 61 (12.16) | 40 (22.2) | 33 (14.0) | 18 (27.3) | 38 (11.9) | 14 (26.3) | 38 (18.4) | 14 (20.5) | 17 (7.0) | 15 (15.2) |

| Medical conditions | ||||||||||||

| Arthritis | 118 (34.5) | 20 (40.2) | 78 (21.4) | 44 (29.2) | 24 (10.3) | 19 (23.1) | 126 (40.0) | 25 (48.1) | 30 (15.2) | 12 (17.3) | 78 (33.3) | 30 (34.3) |

| Diabetes | 50 (14.5) | 13 (25.9)‡ | 53 (15.0) | 38 (30.7)† | 25 (11.6) | 12 (11.3) | 23 (7.0) | 8 (13.3) | 48 (23.8) | 16 (24.8) | 26 (10.9) | 14 (20.6) |

| Hypertension | 132 (38.3) | 26 (51.0) | 168 (47.1) | 76 (57.7) | 77 (35.3) | 57 (66.3)‡ | 100 (33.2) | 23 (43.3)† | 63 (32.3) | 22 (35.6) | 86 (33.8) | 42 (47.5) |

| Stroke | 15 (4.6) | 8 (15.7)† | 35 (9.1) | 8 (3.6) | 13 (4.8) | 4 (8.5) | 34 (10.9) | 5 (7.9) | 12 (6.1) | 3 (4.7) | 10 (4.7) | 1 (0.7) |

| Heart attack | 43 (12.4) | 11 (21.5) | 82 (19.0) | 36 (8.6) | 58 (28.8) | 29 (34.7) | 56 (20.5) | 16 (32.4) | 22 (10.9) | 6 (10.0) | 68 (27.9) | 25 (28.1) |

| Cancer | 8 (2.2) | 3 (6.2) | 12 (3.6) | 4 (3.4) | 9 (2.63) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (2.2) | 2 (2.9) | 4 (2.0) | 1 (10) | 14 (5.8) | 3 (3.4) |

Note: Low WC ≤ 88 cm and High WC > 88 cm. Means and Percents were obtained after adjusting for sampling weights and design effects used in SABE study

P-value <0.0001

p-value < 0.001

p-value < 0.01

ADL = Activities of Daily Living; SABE = Health, Well-Being and Aging in Latin America and the Caribbean; BMI = Body Mass Index

P-values denote differences between subjects with low and high waist circumference for each SABE study

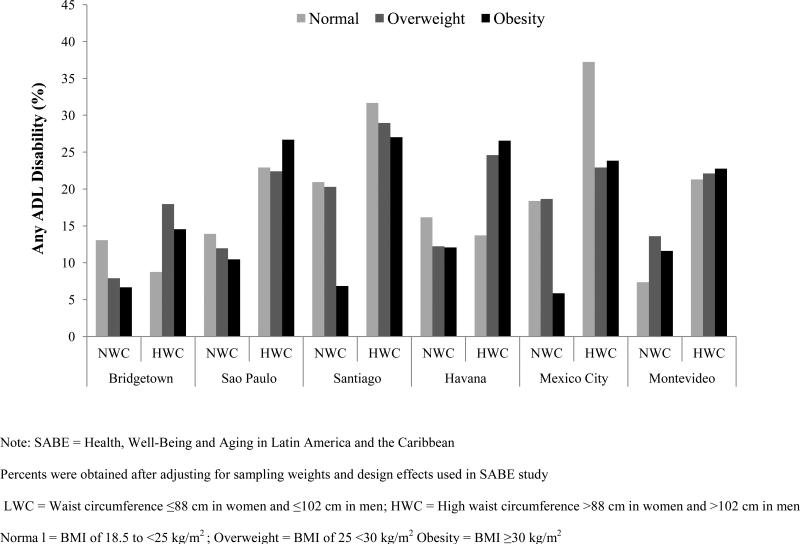

The percent of participants with ADL disability by WC (low or high) and BMI categories after adjusting for sampling weights and design effects for each city is shown in Figure 1. Percent of ADL disability among those with high WC and normal weight ranged from 8.7% (Bridgetown) to 37.2% (Mexico City). Percent of ADL disability among those with high WC and overweight ranged from 17.9% (Bridgetown) to 28.9% (Santiago). Percent of ADL disability among those with high WC and obesity ranged from 14.5% (Bridgetown) to 27.0% (Santiago).

Figure 1.

Percentage of persons with ADL disability by BMI and WC among older adults living in Latin American and the Caribbean (N = 5786).

Figure 2 shows the adjusted probability of ADL disability as a function of WC. The associations between WC and ADL disability were “J” shaped, with higher risks of ADL disability observed above 110 cm for women from Bridgetown, Santiago, Havana, and Montevideo. The association for Sao Paulo is plateau with higher risk above 100 cm while the association for Mexico City is closer to linear. Among men the associations between WC and ADL disability were “U” (Bridgetown, Sao Paulo, and Havana), “J” shaped (Montevideo), plateau (Santiago), and closer to linear in Mexico City (Figure 3). All the associations were significant (p-value < 0.05) except for men from Santiago.

Table 3 presents the odds ratio for ADL disability as a function of WC and BMI category. Overweight or obese participants with high WC from Sao Paulo, Santiago, Havana, and Montevideo were significantly more likely to report ADL disability after adjusting for age and gender (Model 1). When education, marital status, smoking status, and medical conditions were added to Model 1, the association remained statistically significant except for Santiago (Model 2). No significant association was found between high WC and BMI category among participants from Bridgetown and Mexico City. No significant interaction effects were found between BMI and WC, and between BMI, WC, and gender.

Table 3.

Odds ratio of ADL disability as a function of BMI and WC for older adults living in Latin American and the Caribbean (N = 5796).

| Variables | Bridgetown N = 994 OR (95 % CI) a | Sao Paulo N = 1285 OR (95 % CI) a | Santiago N = 844 OR (95 % CI) a | Havana N = 1073 OR (95 % CI) a | Mexico City N = 675 OR (95 % CI) a | Montevideo N = 915 OR (95 % CI) a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | ||||||

| LWC + Normal BMI | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| LWC + Overweight | 0.74 (0.38-1.45) | 1.01 (0.57-1.78) | 1.22 (0.77-1.96) | 0.81 (0.47-1.38) | 1.18 (0.62-2.26) | 1.18 (0.62-2.26) |

| LWC + Obesity | 0.60 (0.16-2.20) | 0.87 (0.11-6.96) | 0.44 (0.07-2.73) | 0.77 (0.26-2.27) | 0.30 (0.04-2.37) | 0.30 (0.37-2.37) |

| HWC + Normal BMI | 0.57 (0.19-1.73) | 1.84 (0.83-4.06) | 1.66 (0.45-6.14) | 0.86 (0.37-1.99) | 2.13 (0.81-5.57) | 2.13 (0.81-5.57) |

| HWC + Overweight | 1.46 (0.83-2.56) | 1.78 (1.14-2.79) | 1.55 (0.83-2.87) | 1.74 (1.04-2.91) | 1.35 (0.74-2.46) | 1.35 (0.74-2.46) |

| HWC + Obesity | 1.43 (0.81-2.54) | 2.45 (1.56-3.86) | 1.68 (1.01-2.80) | 2.15 (1.27-3.65) | 1.62 (0.89-2.97) | 1.62 (0.89-2.97) |

| Model 2 | ||||||

| LWC + Normal BMI | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| LWC + Overweight | 0.80 (0.41-1.57) | 0.97 (0.54-1.76) | 1.26 (0.72-2.20) | 0.79 (0.45-1.37) | 1.24 (0.63-2.45) | 1.24 (0.63-2.45) |

| LWC + Obesity | 0.65 (0.17-2.43) | 0.66 (0.07-6.09) | 0.38 (0.05-2.61) | 0.84 (0.30-2.35) | 0.20 (0.04-1.05) | 0.20 (0.04-1.05) |

| HWC + Normal BMI | 0.59 (0.18-1.84) | 2.01 (0.89-4.53) | 1.41 (0.32-6.20) | 0.74 (0.31-1.76) | 1.99 (0.74-5.36) | 1.99 (0.74-5.36) |

| HWC + Overweight | 1.26 (0.70-2.28) | 1.67 (1.04-2.68) | 1.12 (0.56-2.24) | 1.58 (0.93-2.68) | 1.41 (0.73-2.70) | 1.41 (0.73-2.70) |

| HWC + Obesity | 1.21 (0.67-2.21) | 1.98 (1.21-3.24) | 1.38 (0.76-2.52) | 1.95 (1.15-3.31) | 1.52 (0.81-2.86) | 1.52 (0.81-2.86) |

Odds ratio and 95% CI were obtained after adjusting for sampling weights and design effects used in SABE study

Model 1: Controlled for age and gender

Model 2: Controlled for age, gender, marital status, education, smoking status, and medical conditions (arthritis, diabetes, heart attack, stroke, hypertension, and cancer)

ADL =Activities of daily living; SABE = Health, Well-Being and Aging in Latin America and the Caribbean; BMI = Body mass index; WC = Waist circumference; CI = Confidence Interval

LWC = Low waist circumference ≤88 cm in women and ≤102 cm in men

HWC = High waist circumference >88 cm in women and >102 cm in men

Normal BMI = 18.5 to <25 kg/m2

Overweight = BMI of 25 <30 kg/m2

Obesity = BMI ≥30 kg/m2

4. Discussion

This study examined the prevalence of high WC (> 88 cm in women and > 102 cm in men) and the combined effect of BMI and WC on ADL disability among older adults from six Latin American and Caribbean cities. The highest prevalence of high WC was found in Mexico City for women and Santiago for men. The highest prevalence of ADL disability among those with high WC was seen in men and women from Santiago. The association between WC and ADL disability were mostly “J” shaped among women and “U” or “J” shaped among men. When examining the combined effect of BMI and WC on ADL disability, we found that overweight or obese participants with high WC from Sao Paulo, Santiago, Havana, and Montevideo were significantly more likely to report ADL disability.

These findings are consistent with previous research showing that high WC is significantly associated with disability among older adults (Chen & Guo, 2008; Guallar-Castillon et al., 2007; Janssen et al., 2005). Data from a cross-sectional study of elderly Hispanics in Massachusetts demonstrated a relationship between greater WC and higher frequency of ADL limitations (Chen & Guo, 2008). Guallar-Castillion et al. found an association between WC and self-reported disability, independent of BMI, among people aged 60 years and over in a longitudinal study in Spain (Guallar-Castillon et al., 2007).

The increase of obesity in older adults is a public health concern in the region of Latin America and the Caribbean because this trend may lead to a subsequent increase in many chronic diseases, which, in turn, would result in a dramatic increase in functional disabilities (Guallar-Castillon et al., 2007; Uauy et al., 2001). As people grow old, muscle mass and strength decrease, and body fat increases (National Heart, 2002). Moreover, obesity including overweight is likely to cause pain on weight-bearing, limiting older people's ability to exercise continually, and regularly (Houston et al., 2009). Also, metabolic abnormalities in obesity lead to higher rate of cardiovascular disease (CVD), diabetes, and arthritis, all associated with higher risk of disability (Houston et al., 2009).

BMI has usually been the measurement indicator when examining the relationship between obesity and disability. However, WC alone or combined with BMI should be considered as another predictor of disability in the older adult population. A high WC is one of the primary risk factors for Type 2 diabetes, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and CVD particularly in overweight and obese people (National Heart, 2002; Kuczmarski et al., 1997; Chan et al., 1994; Zhu et al., 2004). WC is the measurement of sagittal abdominal diameter, which offers higher precision and better correlation with CVD risk factors and comorbidities, independently of BMI (National Heart, 2002; Turcato et al., 2000). WC and BMI as a combined obesity marker for the older population could offer a measurement for use in research and clinical settings, linking obesity to disability and other health outcomes.

Our study has some limitations. First, this research could not investigate the causal relationship between high WC and ADL disability due to the cross-sectional research design. Second, since disability and medical conditions were self-reported; matters of recall bias may be an issue, particularly for older adult participants. However, other investigators have found good agreement between self-reported medical events and comorbid diseases or conditions (Haapanen et al., 1997; Simpson et al., 2004). Fourth, exclusion of participants with missing information could underestimate the effect of WC on disability. Despite these limitations, this study has several strengths. First, the survey data in six capital cities was from a large well-defined organized sample. Survey measurements were consistent across all cities, allowing for direct comparisons. Although different groups of interviewers implemented this survey, all had consistent and uniform training in data collection and measurement procedures in each city for assessment of BMI, WC, and disability. Second, this research was generalizable to all older adults in the cities of origin in Latin America and the Caribbean because most of the older adults in these areas live in urban settings (Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean, 2004).

5. Conclusions

We found a “J” or “U” shaped association between WC and ADL disability; and that overweight and obese participants with high WC have significant odds of ADL disability. The findings of this study suggests that both general and abdominal adiposity are associated with disability and support the use of WC in addition to BMI to assess risk of disability in older adults.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This study is supported by grants R03-AG029959, R01-AG010939, R24 HD065702, and by the UTMB Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center Grant # P30 AG024832 from the National Institute of Health/National Institute of Aging, U.S. Dr. Al Snih was supported by a research career development award (K12HD052023: Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women's Health Program–BIRCWH) from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development; the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; and the Office of the Director, National Institutes of Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the author(s) and does not necessarily represent the official views of these Institutes or the National Institutes of Health. The funding agencies did not influence the design, analysis or interpretation of study results.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Al Snih. S., Graham JE, Kuo YF, Goodwin JS, Markides KS, Ottenbacher KJ. Obesity and disability: relation among older adults living in Latin America and the Caribbean. Am.J.Epidemiol. 2010;171:1282–1288. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albala C, Lebrao ML, Leon Diaz EM, Ham-Chande R, Hennis AJ, Palloni A, et al. [The Health, Well-Being, and Aging (“SABE”) survey: methodology applied and profile of the study population]. Rev.Panam.Salud Publica. 2005;17:307–322. doi: 10.1590/s1020-49892005000500003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angleman SB, Harris TB, Melzer D. The role of waist circumference in predicting disability in periretirement age adults. Int.J.Obes. 2006;30:364–373. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan JM, Rimm EB, Colditz GA, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC. Obesity, fat distribution, and weight gain as risk factors for clinical diabetes in men. Diabetes Care. 1994;17:961–969. doi: 10.2337/diacare.17.9.961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Guo X. Obesity and functional disability in elderly Americans. J.Am.Geriatr.Soc. 2008;56:689–694. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01624.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean . Population, Ageing and Development San Juan. United Nations; Puerto Rico: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Filozof C, Gonzalez C, Sereday M, Mazza C, Braguinsky J. Obesity prevalence and trends in Latin-American countries. Obes.Rev. 2001;2:99–106. doi: 10.1046/j.1467-789x.2001.00029.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guallar-Castillon P, Sagardui-Villamor J, Banegas JR, Graciani A, Fornes NS, Lopez GE, et al. Waist circumference as a predictor of disability among older adults. Obesity. 2007;15:233–244. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haapanen N, Miilunpalo S, Pasanen M, Oja P, Vuori I. Agreement between questionnaire data and medical records of chronic diseases in middle-aged and elderly Finnish men and women. Am.J.Epidemiol. 1997;145:762–769. doi: 10.1093/aje/145.8.762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houston DK, Ding J, Nicklas BJ, Harris TB, Lee JS, Nevitt MC, et al. Overweight and obesity over the adult life course and incident mobility limitation in older adults: the health, aging and body composition study. Am.J Epidemiol. 2009;169:927–936. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs EJ, Newton CC, Wang Y, Patel AV, McCullough ML, Campbell PT, et al. Waist circumference and all-cause mortality in a large US cohort. Arch.Intern.Med. 2010;170:1293–1301. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen I, Katzmarzyk PT, Ross R. Body mass index is inversely related to mortality in older people after adjustment for waist circumference. J.Am.Geriatr.Soc. 2005;53:2112–2118. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00505.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz s, Ford AB, Moscowitz RW, Jackson BA, Jaffe NM. The index of ADL: a standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function. JAMA. 1963;21:941–949. doi: 10.1001/jama.1963.03060120024016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinsell k, He W. An aging world: 2008, International Population Report (Rep. No. P95/09-1) Washington DC: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kuczmarski RJ, Carroll MD, Flegal KM, Troiano RP. Varying body mass index cutoff points to describe overweight prevalence among U.S. adults: NHANES III (1988 to 1994). Obes.Res. 1997;5:542–548. doi: 10.1002/j.1550-8528.1997.tb00575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh L. Estimating the number and location of knots in spline regression. J Appl Bus Res. 1986:60–70. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh L, Cormier D. Spline regression models. Sage; Thousand Oaks (CA): 2001. [Google Scholar]

- National Heart, Lung, Blood Insitute Clinical guidlines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults: Evidence Report. (Rep. No. 02-4084). 2002.

- Palloni A, Pinto-Aguirre G, Pelaez M. Demographic and health conditions of ageing in Latin America and the Caribbean. Int.J.Epidemiol. 2002;31:762–771. doi: 10.1093/ije/31.4.762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peláez M, Palloni A, Albala C, Alfonso JC, Ham-Chande R, Hennis A, Lebrao ML, Leon-Diaz E, Pantelides A, Pratts O. Survey of Aging Health and Wellbeing 2000. Pan American Health Organization (PAHO/WHO); 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson CF, Boyd CM, Carlson MC, Griswold ME, Guralnik JM, Fried LP. Agreement between self-report of disease diagnoses and medical record validation in disabled older women: factors that modify agreement. J.Am.Geriatr.Soc. 2004;52:123–127. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52021.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turcato E, Bosello O, Di F,V, Harris TB, Zoico E, Bissoli L, et al. Waist circumference and abdominal sagittal diameter as surrogates of body fat distribution in the elderly: their relation with cardiovascular risk factors. Int.J Obes.Relat Metab Disord. 2000;24:1005–1010. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uauy R, Albala C, Kain J. Obesity trends in Latin America: transiting from under- to overweight. J.Nutr. 2001;131:893S–899S. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.3.893S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations . World population ageing, 1950-2050. United Nations; New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Villareal DT, Apovian CM, Kushner RF, Klein S. Obesity in older adults: Technical review and position statement of the American Society for Nutrition and NAASO, The Obesity Society. Obesity Research. 2005;13:1849–1863. doi: 10.1038/oby.2005.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visscher TL, Seidell JC, Molarius A, van der KD, Hofman A, Witteman JC. A comparison of body mass index, waist-hip ratio and waist circumference as predictors of all-cause mortality among the elderly: the Rotterdam study. Int.J.Obes.Relat Metab Disord. 2001;25:1730–1735. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamboni M, Mazzali G, Zoico E, Harris TB, Meigs JB, Di F,V, et al. Health consequences of obesity in the elderly: a review of four unresolved questions. Int.J.Obes. 2005;29:1011–1029. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu S, Heshka S, Wang Z, Shen W, Allison DB, Ross R, et al. Combination of BMI and Waist Circumference for Identifying Cardiovascular Risk Factors in Whites. Obes.Res. 2004;12:633–645. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]