SUMMARY

Many critical protein kinases rely on the Hsp90 chaperone machinery for stability and function. After initially forming a ternary complex with kinase client and the co-chaperone p50Cdc37, Hsp90 proceeds through a cycle of conformational changes facilitated by ATP binding and hydrolysis. Progression through the chaperone cycle requires release of p50Cdc37 and recruitment of the ATPase activating co-chaperone AHA1, but the molecular regulation of this complex process at the cellular level is poorly understood. We demonstrate that a series of tyrosine phosphorylation events, involving both p50Cdc37 and Hsp90, are minimally sufficient to provide directionality to the chaperone cycle. p50Cdc37 phosphorylation on Y4 and Y298 disrupts client-p50Cdc37 association, while Hsp90 phosphorylation on Y197 dissociates p50Cdc37 from Hsp90. Hsp90 phosphorylation on Y313 promotes recruitment of AHA1 which stimulates Hsp90 ATPase activity, furthering the chaperoning process. Finally, at completion of the chaperone cycle, Hsp90 Y627 phosphorylation induces dissociation of the client and remaining co-chaperones.

INTRODUCTION

The molecular chaperone Hsp90 regulates the stability and function of a host of cellular signaling proteins (‘clients’), many of which are protein kinases. The Hsp90-dependent chaperone cycle requires sequential association and dissociation of various co-chaperones in concert with ATP binding and hydrolysis in order to productively chaperone and release the client (Taipale et al., 2010). In the absence of co-chaperones, Hsp90 conformational dynamics in solution are stochastically determined and thermally driven, and do not support a productive chaperone cycle (Ratzke et al., 2011). How co-chaperones regulate the directionality of this complex molecular machine in the cellular milieu remains obscure. Hsp90 initially forms a ternary complex with client kinase and p50Cdc37. Phosphorylation of p50Cdc37 on S13, mediated by casein kinase 2 (CK2), has been proposed to promote the formation of stable complexes with various client kinases including Raf-1, Cdk4, and Src (Miyata and Nishida, 2004; Shao et al., 2003b). However, dephosphorylation of S13 by the phosphatase (and Hsp90 co-chaperone) PP5 was shown recently not to perturb client kinase association with p50Cdc37 (Vaughan et al., 2008), suggesting that additional events likely participate in regulating disassembly of the p50Cdc37-kinase complex in cells.

After initially mediating association of client kinase and Hsp90, p50Cdc37 must dissociate for the chaperone cycle to proceed, because it inhibits Hsp90 ATPase activity (Siligardi et al., 2002). In contrast, association of the co-chaperone AHA1 stimulates the inherently low ATPase activity of Hsp90, thus helping to productively drive the chaperone cycle (Panaretou et al., 2002). Although p50Cdc37 and AHA1 likely do not bind simultaneously to Hsp90 (Harst et al., 2005), cellular regulation of their sequential association and disassociation is poorly understood.

In higher eukaryotes, p50Cdc37 and Hsp90 are phosphorylated on tyrosine residues (Gilmore et al., 1982). However, the functional significance of p50Cdc37 tyrosine phosphorylation has remained unexplored, while that of Hsp90 has only recently begun to be elucidated (Mollapour and Neckers, 2011). Here, we present data showing that human p50Cdc37 tyrosine phosphorylation promotes p50Cdc37 dissociation from client kinase proteins. Further, phosphorylation of specific tyrosine residues in Hsp90 is minimally sufficient to modulate association and dissociation of p50Cdc37 and AHA1, and thus significantly influences Hsp90 ATPase activity and the directionality of the Hsp90 chaperone cycle.

RESULTS

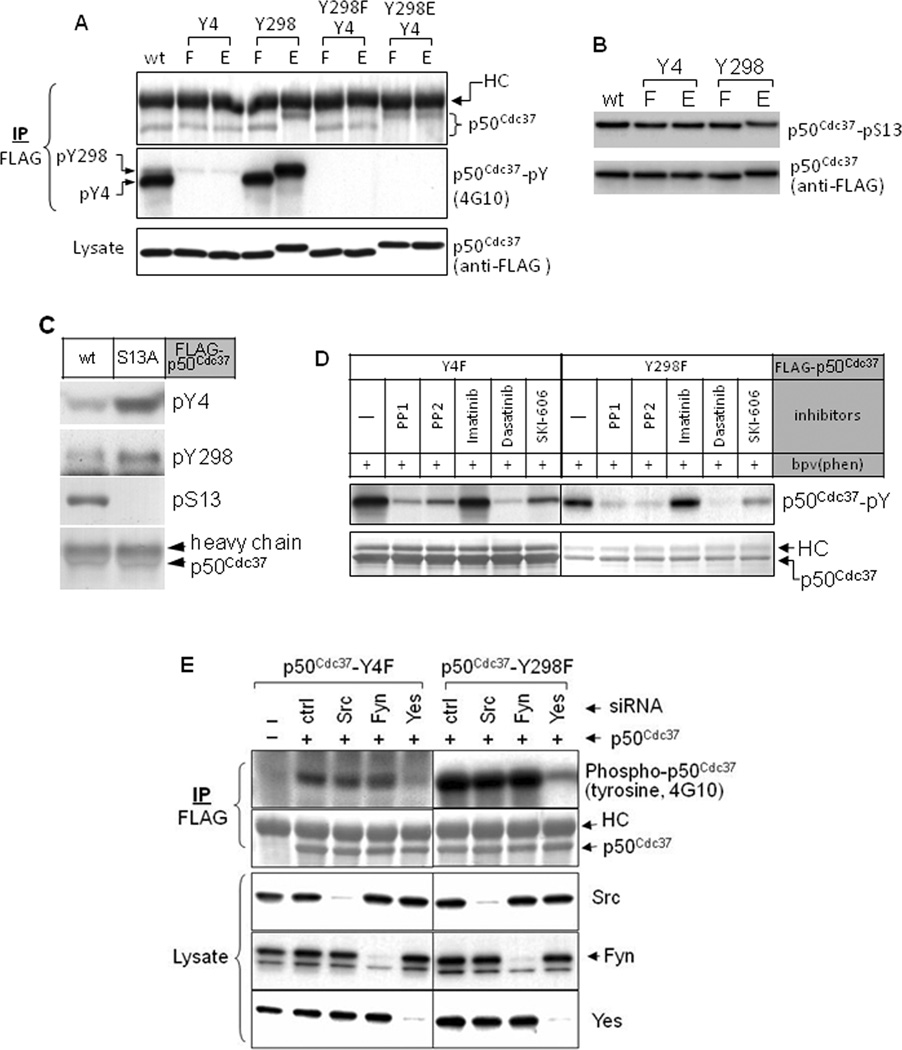

p50Cdc37 is tyrosine phosphorylated on Y4 and Y298

p50Cdc37 is reported to be phosphorylated on Y298, although the functional significance of this modification is not described (Rush et al., 2005). Further, mutation of the conserved tyrosine residue Y4 disrupts p50Cdc37 interaction with heme-regulated eIF2α kinase in reticulocyte lysate (Shao et al., 2003a). We examined p50Cdc37 tyrosine phosphorylation status in COS7 cells. Using anti-phospho-tyrosine antibody, we could not detect phosphorylation of p50Cdc37 immunoprecipitated from untreated cells. However, p50Cdc37 isolated from cells treated briefly with the cell permeable phosphatase inhibitor bpv(phen) was phosphorylated on tyrosine to high levels (Fig. 1A). Phosphorylated p50Cdc37 was resolved into two bands by electrophoresis, a weak upper band and a more intense lower band. Mutation of the Y4 residue abolished the strong lower band, while mutation of Y298 abolished the weak upper band. Importantly, p50Cdc37 harboring Y298E phosphomimetic mutation migrated similarly to p50Cdc37 phosphorylated on Y298, suggesting an influence of negative charge at this location on p50Cdc37 electrophoretic mobility. Tyrosine phosphorylation was not observed when both Y4 and Y298 were mutated, confirming that these are the only p50Cdc37 phosphotyrosine residues.

Figure 1.

p50Cdc37 in cells is tyrosine phosphorylated. A. Tyrosine phosphorylation of cellular p50Cdc37 occurs only on amino acids Y4 and Y298. COS7 cells were transfected with indicated FLAG-tagged p50Cdc37 constructs. Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were treated with 100 µM bpv(phen) for 30 min (to inhibit tyrosine phosphatases), lysed with 1% SDS buffer, and boiled for 5 min. p50Cdc37 proteins were precipitated with anti-FLAG antibody, and tyrosine phosphorylation was detected by blotting with antibody 4G10. Protein loading was monitored with anti-FLAG antibody. Note that p50Cdc37-Y298E and p50Cdc37-phosphoY298 have a similar mobility. B. p50Cdc37 tyrosine phosphorylation status does not affect p50Cdc37 serine phosphorylation. Indicated p50Cdc37 proteins were expressed in COS7 cells and immunoprecipitated as described above andS13 phosphorylation was detected. C. p50Cdc37 serine phosphorylation status affects p50Cdc37 tyrosine phosphorylation. Indicated p50Cdc37 proteins were expressed in COS7 cells and assessed as described above. Phosphorylation of Y4 and Y298 was assessed using site-specific anti-phospho-tyrosine antibodies (see Fig. S1 for antibody validation). D. p50Cdc37 tyrosine phosphorylation is reduced by Src family kinase inhibition. 293H cells were transfected with indicated p50Cdc37 plasmids. Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were pretreated with indicated kinase inhibitors for 2 hours, and then with bpv(phen) for 20 min. Sample preparation and analysis were as described above. E. Yes kinase is responsible for p50Cdc37 tyrosine phosphorylation. 293H cells were co-transfected with siRNA specific for the indicated Src family kinases and p50Cdc37-Y4F or p50Cdc37-Y298F. Two days after transfection, cells were lysed and samples were prepared and analyzed as above (see also Fig. S1).

p50Cdc37 is also phosphorylated on serine 13 (Shao et al., 2003b). Neither Y4 nor Y298 mutation affected p50Cdc37 S13 phosphorylation (Fig. 1B). In contrast, tyrosine phosphorylation on both Y4 and Y298 was more robust for p50Cdc37-S13A, suggesting that dephosphorylation of p50Cdc37 S13 may be a prerequisite for optimal tyrosine phosphorylation to occur (Fig. 1C).

p50Cdc37 tyrosine phosphorylation is mediated by Yes

To identify the tyrosine kinase(s) responsible for p50Cdc37 phosphorylation, we treated 293H cells expressing p50Cdc37 mutated at either Y4 or Y298 with several kinase inhibitors. Phosphorylation of both p50Cdc37-Y4F (indicating Y298 phosphorylation) and p50Cdc37-Y298F (indicating Y4 phosphorylation) was dramatically decreased by the kinase inhibitors PP1, PP2, dasatinib, and SKI-606, all of which inhibit Src family and Abl kinases (Fig. 1D). However, p50Cdc37 tyrosine phosphorylation was not affected by imatinib, which preferentially inhibits Abl. These results suggested that one or more Src family kinases mediate p50Cdc37 tyrosine phosphorylation.

We used siRNA silencing to identify the Src family kinase(s) mediating p50Cdc37 tyrosine phosphorylation. Src, Fyn, and Yes are ubiquitously expressed in different cell types (Thomas and Brugge, 1997), and are thus likely candidates for this activity. While silencing of Src and Fyn were without effect, silencing of Yes resulted in dramatically reduced p50Cdc37 tyrosine phosphorylation (Fig. 1D). Y4 and Y298 phosphorylation were equally reduced upon Yes knock-down, confirming Yes as the predominant tyrosine kinase responsible for phosphorylating p50Cdc37.

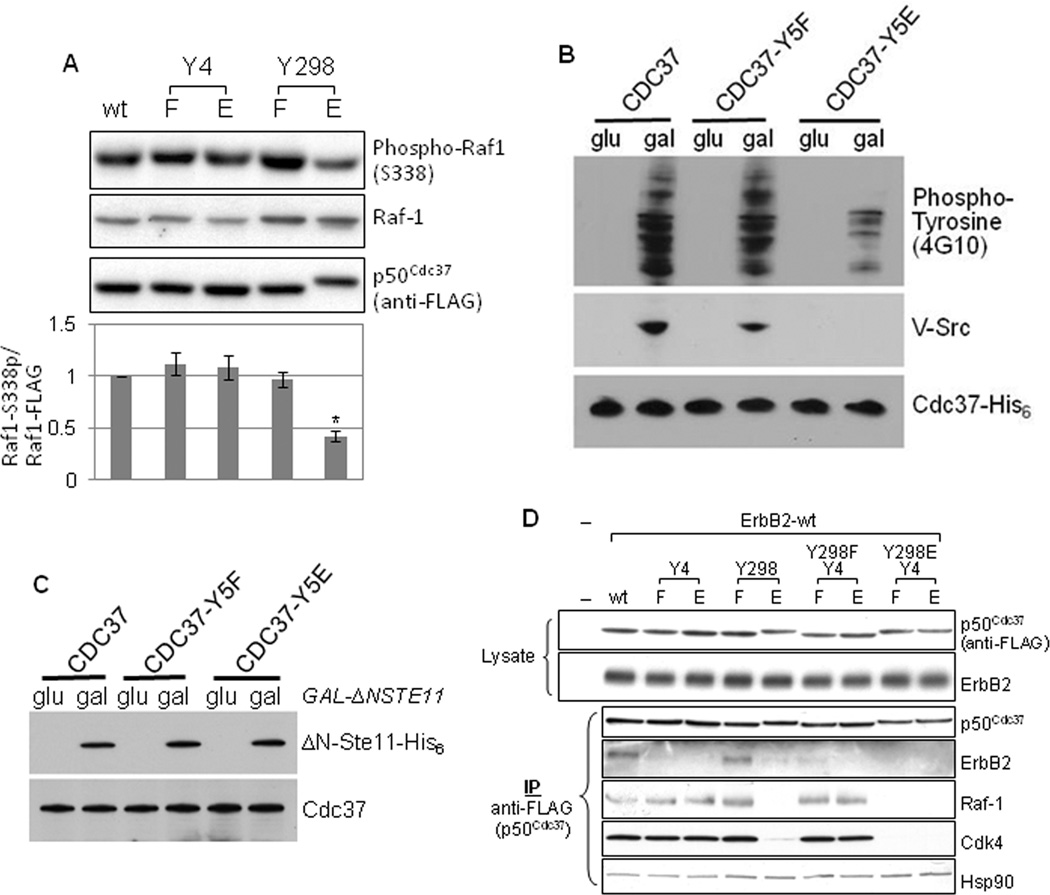

p50Cdc37 chaperone function is compromised by mutation of tyrosine phosphorylation sites

p50Cdc37 is required for optimal kinase activity in eukaryotes. To investigate the physiologic implications of p50Cdc37 tyrosine phosphorylation, we examined whether mutation of Y4 or Y298 affects its chaperone function. First, we co-expressed wild-type or mutant p50Cdc37 together with the FLAG-tagged catalytic domain of Raf-1 kinase in COS7 cells, and we assessed Raf-1 kinase activity by monitoring phosphorylation of the Raf-1 residue S338 as an indicator of Raf-1 activation. Importantly, stable expression of exogenous Raf-1 catalytic domain in COS7 cells requires excess p50Cdc37, and is thus only detectable when exogenous p50Cdc37 is also present (Fig. S1A). We found that, when co-expressed with the p50Cdc37 phosphomimetic mutant Y4E or the p50Cdc37 non-phosphomimetic mutants Y4F and Y298F, Raf-1 catalytic domain activity was equivalent to that seen with co-expressed wild-type p50Cdc37 (Fig. 2A). However, when co-expressed with the phosphomimetic mutant p50Cdc37-Y298E, Raf-1 catalytic domain activity was significantly reduced (Fig. 2A), indicating Y298 phosphorylation status (but not Y4 phosphorylation status) is a key determinant regulating p50Cdc37-dependent Raf-1 activation. Importantly, upon Yes knockdown, Raf-1 catalytic domain activity was also significantly impaired, even in the presence of excess p50Cdc37 (Fig. S1B)

Figure 2.

Mutation of Y298 and Y4 affects p50Cdc37 chaperone function. A. Phosphomimetic mutation of Y298, but not of Y4, compromises p50Cdc37-dependent activation of Raf-1. COS7 cells were co-transfected with indicated p50Cdc37 plasmids and a plasmid expressing FLAG-tagged Raf-1 catalytic domain. Raf-1 catalytic domain activity was assessed by detecting S338 phosphorylation. The signal obtained with phospho-S338 antibody was normalized to the corresponding Raf-1 catalytic fragment protein expression level. Please see Experimental Procedures for quantitation method. B. Y5E-mutated yeast Cdc37 cannot chaperone v-Src (Y5 in yeast Cdc37 is equivalent to Y4 in human p50Cdc37). Appreciable levels of v-Src and tyrosine phosphorylated yeast proteins are detectable in both wild type Cdc37-expressing yeast and in yeast expressing Cdc37-Y5F, but not in cells expressing Cdc37-Y5E. C. Y5 mutation in yeast Cdc37 permits normal chaperoning of the Raf-1 homolog Ste11ΔN in yeast. The expression of Ste11ΔN was induced by galactose in yeast expressing wild-type Cdc37, Cdc37-Y5F, or Cdc37-Y5E. Cdc37 and Ste11ΔN protein levels were visualized by western blotting. D. Client kinase binding to p50Cdc37 is uniformly affected by the phosphorylation status of Y298. COS7 cells were transfected with wild-type ErbB2 and indicated p50Cdc37 plasmids. Association of the exogenously expressed kinase ErbB2, as well as endogenous kinases Raf-1 and Cdk4, with p50Cdc37 proteins was assessed as described (see also Fig. S2).

Unlike Y298, Y4 is conserved in yeast Cdc37 (Y5 in yeast Cdc37 is equivalent to Y4 in human p50Cdc37). Thus, the functional implications of Y4 phosphorylation were investigated by examining the ability of Cdc37 Y5 mutants to productively chaperone v-Src in yeast. We observed significant Src-mediated tyrosine phosphorylation of cellular proteins in yeast expressing wild-type Cdc37 or Cdc37-Y5F, but markedly decreased tyrosine phosphorylation was seen in yeast expressing Cdc37-Y5E (Fig. 2B). v-Src protein level was also dramatically reduced in these cells. These effects cannot be ascribed to reduced expression of Cdc37-Y5E, as both mutant and wild-type proteins were expressed at comparable levels. The data indicate that both protein expression and kinase activity of v-Src were compromised in the presence of the phosphomimetic mutant Cdc37-Y5E.

Y5 mutation did not compromise the ability of Cdc37 to stabilize the active form of the Raf-1 homolog Ste11, which is Cdc37-dependent (Abbas-Terki et al., 2000) (ΔN-Ste11, Fig. 2C). These data are in agreement with our earlier observation that p50Cdc37 Y4 mutation had no effect on the kinase activity of exogenously expressed Raf-1 catalytic fragment in COS7 cells. Further, they emphasize that the chaperone activity of Cdc37-Y5E is not generally compromised, and they suggest that phosphorylation of Y4 and Y298 may differentially affect the ability of p50Cdc37 to chaperone individual kinases.

To explore this possibility further, we examined the impact of these mutations on p50Cdc37 association with several client kinases in mammalian cells. We found that neither Y4 nor Y298 mutation affected p50Cdc37 association with Hsp90 in COS7 cells (Fig. 2D). However, association of client kinases was substantially affected. The Y298F mutant associated with client kinases with similar efficiency as wild type p50Cdc37, while the Y298E mutant lost association with all kinases examined, including ErbB2, Cdk4, and Raf-1 (Fig. 2D). The impact of Y4 mutation was more variable. While Y4 mutation did not affect p50Cdc37 association with Cdk4 or Raf-1, interaction with ErbB2 was abolished (Fig. 2D).

We also examined whether v-Src association with p50Cdc37 Y4 mutants in mammalian cells was compromised. Using v-Src transformed NIH-3T3 cells, we indeed observed a negative impact of Y4 mutation on p50Cdc37 association with v-Src (Fig. S2). In contrast, but in agreement with the data obtained in COS7 cells, Y4 mutation did not affect p50Cdc37 association with endogenous Raf-1 in these cells. Further, p50Cdc37 Y298F mutation affected neither v-Src nor Raf-1 association, while p50Cdc37 Y298E mutation strongly reduced interaction with both kinases. Taken together, these data suggest that phosphomimetic mutation of Y298 in the C-terminal domain uniformly disrupts p50Cdc37 association with client kinases, while mutation of the p50Cdc37 N-domain residue Y4 has a more limited impact, in this study affecting only ErbB2 and v-Src interaction. Of note, the association profile of mutant p50Cdc37 correlates with the aforementioned impact of these proteins on kinase activity.

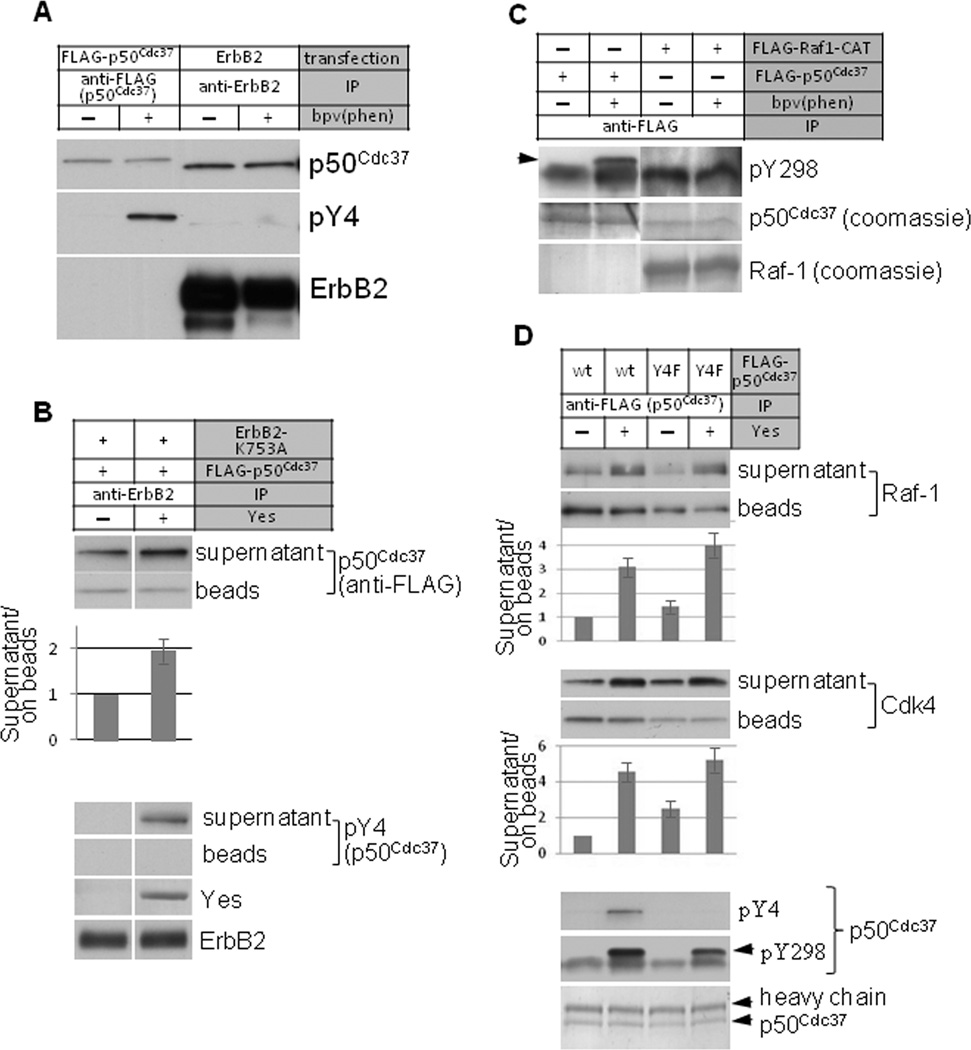

Tyrosine phosphorylation of p50Cdc37 disrupts the kinase-chaperone complex

Since phosphomimetic mutation of Y4 and Y298 dissociated p50Cdc37 and kinase proteins, the p50Cdc37 that is in complex with kinase clients is predicted to be unphosphorylated or hypophosphorylated compared to the total cellular pool of p50Cdc37. To test this hypothesis, we used an antibody raised specifically to phosphorylated Y4 to examine the Y4 phosphorylation status of p50Cdc37 that was co-precipitated with ErbB2 (Fig. 3A). No phosphorylation on Y4 was detected in FLAG-p50Cdc37 isolated from cells not treated with the phosphatase inhibitor bpv(phen), which is consistent with our earlier observations. Brief treatment with bpv(phen) prior to lysis significantly increased Y4 phosphorylation of the total p50Cdc37 pool precipitated with anti-FLAG antibody, but not in p50Cdc37 that was co-immunoprecipitated with antibody to ErbB2.

Figure 3.

Tyrosine phosphorylation of p50Cdc37 in vitro disrupts the kinase-chaperone complex. A. ErbB2-associated p50Cdc37 is hypo-phosphorylated on Y4. ErbB2 or FLAG-tagged p50Cdc37 were immunoprecipitated from transfected COS7 cells treated with or w/o bpv(phen) for 30 minutes. p50Cdc37 Y4 phosphorylation was detected with phospho-specific antibody. B. Yes kinase-mediated tyrosine phosphorylation of p50Cdc37 promotes its dissociation from ErbB2. Kinase-deficient ErbB2-K753 was co-expressed with FLAG-p50Cdc37 in COS7 cells. ErbB2 was immunoprecipitated with antibody-bound beads. ErbB2 beads were extensively washed and subjected to in vitro phosphorylation using purified Yes kinase. Supernatant was collected, beads were washed again, and remaining bound proteins were eluted with SDS sample buffer. p50Cdc37 protein was detected in both supernatant and ErbB2 bead fractions by western blotting. The ratio of p50Cdc37 in the supernatant to that remaining associated with ErbB2 beads, in the presence and absence of Yes kinase, was quantified and graphed. Yes-mediated phosphorylation of p50Cdc37-Y4 was visualized using anti-pY4 antibody. Y4 phosphorylation was only observed on the fraction of p50Cdc37 released into the supernatant, and was not detected on the fraction of p50Cdc37 that remained associated with ErbB2 beads. C. Raf-1-associated p50Cdc37 is hypophosphorylated on Y298. FLAG-tagged Raf-1 or FLAG-tagged p50Cdc37 were immunoprecipitated from transfected COS7 cells treated with or w/o bpv(phen) for 30 minutes. p50Cdc37 phosphorylation on Y298 was detected with phospho-specific antibody. D. Yes kinase promotes dissociation of Raf-1 and Cdk4 from p50Cdc37. FLAG-p50Cdc37 was expressed in COS7 cells and immunoprecipitated as above. In vitro phosphorylation was performed with Yes kinase. Raf-1 and Cdk4 proteins released into the supernatant or retained on the anti-FLAG (p50Cdc37) beads were detected by western blotting. Phosphorylation of p50Cdc37 on Y4 and Y298 was detected with specific antibodies. The ratios of Raf-1 and Cdk4 released into the supernatant and remaining on the anti-FLAG (p50Cdc37) beads in the presence and absence of Yes kinase were quantified and graphed (see also Fig. S3). Please see Experimental Procedures for quantitation method.

Next, we examined whether in vitro Y4 phosphorylation of p50Cdc37 would disrupt a pre-formed complex with ErbB2. Since ErbB2 itself is a tyrosine kinase, we used a kinase-deficient mutant (ErbB2-K753A) to eliminate any potential interference in vitro from intrinsic ErbB2 kinase activity. We immunoprecipitated the p50Cdc37-ErbB2 complex with an ErbB2-specific antibody, and we incubated the immune complex with purified Yes kinase. Yes significantly increased the release of p50Cdc37 from ErbB2 immune complexes into the soluble phase of the kinase assay (Fig. 3B, anti-FLAG western blot and graphical display). We confirmed that the p50Cdc37 released from ErbB2 immune complexes was phosphorylated on Y4. Importantly, Y4 phosphorylation was not evident in the p50Cdc37 fraction remaining in ErbB2 immune complexes.

Mutation experiments suggested that p50Cdc37 phosphorylation on Y298 would dissociate it from the client kinase Raf-1 (Fig. 2D and Fig. S2). Using a second phospho-specific antibody, we compared Y298 phosphorylation of p50Cdc37 in complex with Raf-1 to that of the total p50Cdc37 fraction. Similar to Y4 phosphorylation, brief treatment with bpv(phen) prior to lysis increased Y298 phosphorylation of the total p50Cdc37 pool, but failed to increase Y298 phosphorylation in the p50Cdc37 fraction in complex with Raf-1 (Fig. 3C; arrow identifies pY298, lower band is non-specific). Taken together, these data indicate that p50Cdc37 is hypo-phosphorylated on both Y4 and Y298 when associated with client kinases.

Finally, we confirmed in vitro the disruptive effects of Y298 phosphorylation on association of p50Cdc37 with client kinases. We expressed FLAG-tagged wild-type or Y4F mutant p50Cdc37 in COS7 cells and we immunoprecipitated p50Cdc37 with anti-FLAG antibody. Endogenous Raf-1 and Cdk4 proteins were co-precipitated. These complexes were incubated with Yes as above. Release of Raf-1 and Cdk4 into the soluble fraction was detected by western blot (also displayed graphically as a ratio with kinase protein remaining on beads). We found that release of both kinases from immune complexes of either wild type or Y4F p50Cdc37 was substantially increased in the presence of Yes, while bead-bound p50Cdc37 was phosphorylated in vitro on Y4 and Y298 (Fig. 3D, arrow identifies pY298, lower band is non-specific). Substituting p50Cdc37-Y298F for wild type p50Cdc37, eliminating ATP from the assay buffer, or including the Src family kinase inhibitor dasatinib in the assay buffer all resulted in comparable and significant reduction of Yes-mediated release of both Raf-1 and Cdk4 from p50Cdc37 immune complexes (Fig. S3). These data confirm that p50Cdc37 phosphorylation on Y298 disrupts association with client kinases.

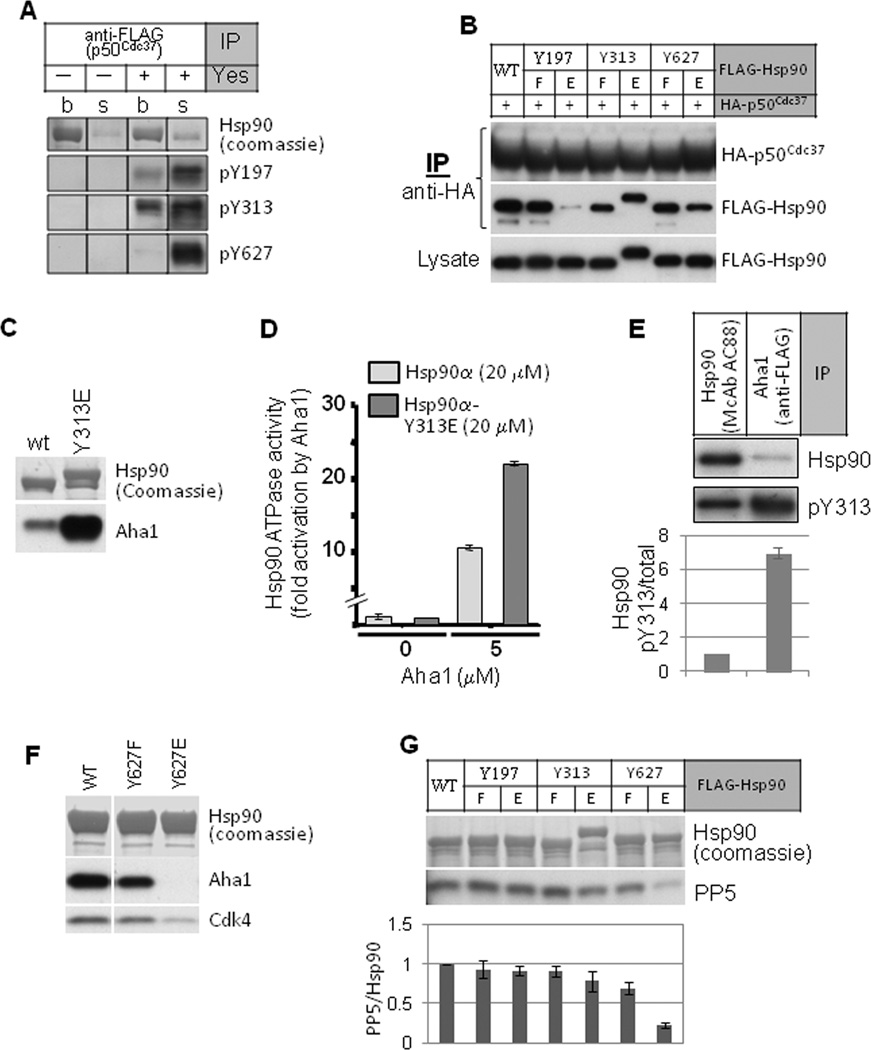

Hsp90 tyrosine phosphorylation disrupts the Hsp90-p50Cdc37 complex and promotes AHA1 recruitment

p50Cdc37 tyrosine phosphorylation disrupts its association with kinase clients but does not affect its association with Hsp90 (Fig. 2D and Fig. S2). Since p50Cdc37 S13 phosphorylation status likewise has minimal impact on association with Hsp90 (Miyata and Nishida, 2004), we used a series of Hsp90 point mutants and several site-specific Hsp90 phospho-antibodies to query the importance of Hsp90 tyrosine phosphorylation in these events. First, we compared the phosphorylation status of 3 previously identified Hsp90 phospho-tyrosine residues (www.phosphosite.org) in the (endogenous) Hsp90 fraction either remaining in p50Cdc37 immune complexes or released into the supernatant fraction following in vitro incubation of the immune complexes with active Yes kinase (Fig. 4A). In the absence of Yes, Hsp90 complexed with p50Cdc37 was not phosphorylated on either Y197, Y313, or Y627, and very little Hsp90 was spontaneously released from p50Cdc37 immune complexes during the course of the experiment. In the presence of Yes, however, more Hsp90 was released into the supernatant and the Hsp90 in this fraction was strongly phosphorylated on these residues. These results raised the possibility that Hsp90 phosphorylation on one or more of these tyrosine residues may promote dissociation of p50Cdc37.

Figure 4.

Hsp90 tyrosine phosphorylation regulates the association and dissociation of co-chaperones. A. FLAG-tagged p50Cdc37 was expressed in COS7 cells and immunoprecipitated. In vitro kinase assay with Yes kinase was as described. Endogenous Hsp90 phosphorylation on tyrosine residues was detected with site-specific antibodies (see Fig. S4 for antibody validation). “s” indicates Hsp90 released into the kinase assay buffer; “b” indicates Hsp90 remaining bound to p50Cdc37 immune complexes. B. Phosphomimetic mutation of Hsp90-Y197 disrupts p50Cdc37 association. HA-tagged p50Cdc37 was expressed in 293A cells together with indicated FLAG-tagged Hsp90 proteins, and p50Cdc37 was immunoprecipitated with anti-HA beads. Association of Hsp90 was detected with anti-FLAG antibody. C. Phosphomimetic mutation of Hsp90-Y313 promotes AHA1 association. FLAG-tagged Hsp90 was precipitated from transfected COS7 cells. Association of AHA1 was detected by western blot. D. AHA1 protein stimulates ATPase activity of Hsp90-Y313E to a greater extent than that of wild type Hsp90. The ATPase activity of purified Hsp90 proteins (20 µM) was determined in the presence or absence of AHA1 (5 µM). E. AHA1-associated Hsp90 is hyper-phosphorylated on Y313. FLAG-tagged AHA1 was expressed in 293A cells and immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG antibody. Associated Hsp90 was examined for phosphorylation on Y313 using antibody recognizing pY313, and the signal was compared with Y313 phosphorylation of total Hsp90 immunoprecipitated from 293A cells. The pY313 signal intensity was normalized to the total Hsp90 signal intensity and graphically displayed. F. Phosphomimetic mutation of Hsp90-Y627 dissociates AHA1 and client kinase (Cdk4) from Hsp90. Indicated FLAG-tagged Hsp90 proteins were transiently expressed in 293A cells and immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG. Association of endogenous AHA1 and Cdk4 was examined by western blot. G. Phosphomimetic mutation of Hsp90-Y627 disrupts PP5 association. Indicated FLAG-tagged Hsp90 proteins were expressed in 293A cells and immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG beads. Association of the co-chaperone phosphatase PP5 was visualized with specific antibody. Loading equivalence was confirmed by Coomassie stain of immunoprecipitated Hsp90 proteins (see also Fig. S4). Please see Experimental Procedures for quantitation method.

To explore this possibility, we made point mutations of each residue. We found that the phosphomimetic mutation Y197E dramatically diminished Hsp90 association with p50Cdc37 (Fig. 4B). These results, together with the data from the in vitro kinase assay, suggest that Y197 phosphorylation promotes dissociation of Hsp90 from p50Cdc37. A corollary of this hypothesis suggests that constitutive phosphorylation of Y197 would block initiation of the kinase-chaperone cycle by interfering with p50Cdc37-Hsp90 association. To investigate this hypothesis in an intact cell system, we studied Y197 phosphorylation and Hsp90-p50Cdc37 association in resting and activated human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs). Resting PBMCs (G0 phase) activated by phobol myristate acetate and ionomycin enter into G1 and proceed to DNA synthesis and cell division, a process that depends on Hsp90 function (Schnaider et al., 2000). We immunoprecipitated Hsp90 from resting PBMCs and found that it was strongly phosphorylated on Y197 and contained little co-precipitated p50Cdc37 or (client kinase) Cdk4 (Fig. S4A). In contrast, 24 h after activation of PBMCs, Hsp90 was no longer detectably phosphorylated on Y197 while significantly more p50Cdc37 and Cdk4 were co-precipitated with Hsp90. These data support the possibility that Hsp90 Y197 phosphorylation status may regulate both initiation and progression of the kinase-chaperone cycle.

After client loading, recruitment of the ATPase stimulatory co-chaperone AHA1 is necessary to efficiently drive the chaperone cycle to completion (Taipale et al., 2010). The phosphomimetic mutation Y313E significantly increased Hsp90 association with AHA1 (Fig. 4C), suggesting that Y313 phosphorylation serves to recruit AHA1 to the Hsp90 complex. Consistent with this hypothesis, the affinity of purified AHA1 protein for purified Hsp90-Y313E was increased 3.5-fold compared to its affinity for wild type Hsp90 (3.7 +/− 0.5 µM vs 13 +/− 2.2 µM). Consistent with these findings, purified AHA1 more potently stimulated the ATPase activity of Hsp90-Y313E compared to wild type Hsp90 (Fig. 4D). Finally, we compared the Y313 phosphorylation level of the total cellular pool of Hsp90 (immunoprecipitated with the pan Hsp90-specific antibody AC88) to that of the Hsp90 fraction found in FLAG-AHA1 immune complexes (Fig. 4E). Hsp90 in complex with AHA1 was phosphorylated on Y313 to a level nearly 7 times that of the total cellular Hsp90 fraction. Since the cellular concentration of AHA1 in mammalian cells is less than 1 % that of Hsp90 (Koulov et al., 2010), a regulatable mechanism to efficiently promote association of these two proteins would be advantageous. Our data are consistent with the hypothesis that Hsp90 Y313 phosphorylation provides a cellular mechanism to stimulate formation of Hsp90-AHA1 ATPase-active chaperone complexes.

For the chaperone cycle to reach completion, the client and any remaining co-chaperones must dissociate from Hsp90. We explored whether Hsp90 tyrosine phosphorylation might contribute to this process. We noted that Hsp90 Y627 was strongly phosphorylated by Yes in vitro, but only in the fraction of Hsp90 not associated with p50Cdc37 (Fig. 4A). This residue has been suggested to be part of a flexible loop in the Hsp90 C-domain that forms a hydrophobic motif mediating client protein binding (Fang et al., 2006; Sgobba et al., 2008; Shiau et al., 2006). We determined whether Y627 phosphorylation favored release of client and co-chaperones. We found that interaction of AHA1, the client Cdk4, and PP5 with Hsp90-Y627E was markedly reduced compared to wild type Hsp90 (Fig. 4F, G).

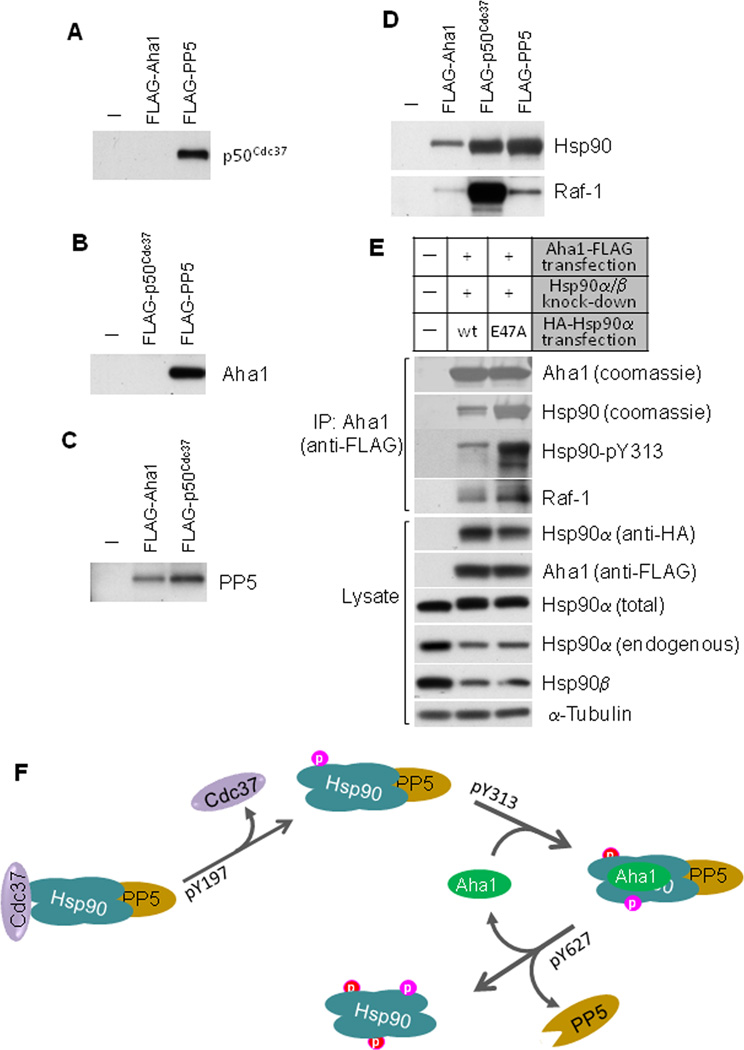

Can these tyrosine phosphorylation events be placed in an ordered sequence?

The Hsp90 chaperone cycle requires an ordered sequence of transient association and dissociation of both client proteins and co-chaperones. After determining the impact on this process of distinct p50Cdc37 and Hsp90 phosphorylation events, we investigated whether these phosphorylations can occur in an appropriate sequential order. This possibility was initially suggested when we noticed markedly reduced Y313 phosphorylation of the Hsp90-Y627E mutant (Fig. S4B), consistent with the lack of AHA1 binding to Hsp90-Y627E. We examined whether certain co-chaperones can co-exist with Hsp90 in the same complex. We found that p50Cdc37 and AHA1 were mutually excluded from complexes containing the other co-chaperone (Fig. 5A, B), although both proteins bound to Hsp90 (Fig. 5D). Since p50Cdc37 forms the initial complex with client kinases and Hsp90 prior to AHA1 binding and activation of Hsp90 ATPase activity, these data support a model in which p50Cdc37 dissociates from Hsp90 prior to association of AHA1 (Harst et al., 2005). Thus, Hsp90 phosphorylation on Y313 should occur preferentially after Y197 phosphorylation, based on the impact of these phosphorylation events on co-chaperone binding (see Fig. 4). In fact, Y313 phosphorylation intensity of Hsp90-Y197E is 2-fold that of wild type Hsp90 (Fig. S4C).

Figure 5.

AHA1 and p50Cdc37 bind to Hsp90 simultaneously with PP5, but they each exist in separate complexes with Hsp90. A. p50Cdc37 co-exists with PP5 but not with AHA1 in Hsp90 complexes. FLAG-tagged AHA1 and PP5 were expressed in 293A cells and immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG beads. Association of p50Cdc37 was examined with anti-p50Cdc37 antibody. B. AHA1 co-exists with PP5 but not with p50Cdc37 in Hsp90 complexes. FLAG-tagged p50Cdc37 and PP5 were expressed in 293A cells and immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG beads. Association of AHA1 was examined with anti-AHA1 antibody. C. PP5 co-exists with AHA1 and p50Cdc37 on Hsp90. FLAG-tagged p50Cdc37 and AHA1 were expressed in 293A cells and immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG beads. Association of PP5 was examined with anti- PP5 antibody. D. Association of Hsp90 and Raf-1 with p50Cdc37, AHA1 and PP5. FLAG-tagged p50Cdc37, PP5, and AHA1 were expressed in 293A cells and immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG beads. Association of Hsp90 and Raf-1 were examined with specific antibodies. E. AHA1-Hsp90-client kinase complexes are enriched with Hsp90 mutants that cannot hydrolyze ATP. After silencing endogenous Hsp90 (α and β) with siRNA, we expressed either HA-tagged wild type Hsp90α or the ATPase-deficient mutant Hsp90α-E47A and FLAG-tagged AHA1. Transfected Hsp90α is not affected by the siRNA used to knock down endogenous Hsp90 because it is targeted to a 3’-UTR in Hsp90 mRNA and the Hsp90α cDNA used for transfection lacks the 3’-UTR. After anti-FLAG immunoprecipitation, we blotted for endogenous Raf-1 and Hsp90-pY313. AHA1-associated Hsp90 was detected by Coomassie staining. Total Hsp90α (transfected and endogenous) was detected with antibody SPA-835 (Enzo Life Sciences), while endogenous Hsp90α was detected with SPS-771 (Enzo Life Sciences) which recognizes an epitope in the Hsp90 N-terminus and shows substantially reduced recognition of N-terminally tagged Hsp90 (data not shown). F. Summary of the model proposing the sequential tyrosine phosphorylation of p50Cdc37 and Hsp90.

Both p50Cdc37 and AHA1, as well as Hsp90 and client protein, were present in PP5 immune complexes and PP5 was present in both AHA1 and p50Cdc37 immune complexes (Fig. 5A-D), indicating that PP5 can remain associated with Hsp90 throughout the chaperone cycle, until it dissociates upon Hsp90 Y627 phosphorylation (Fig. 4G). The generally disruptive effects of Y627 phosphorylation on Hsp90 association with co-chaperones and client are consistent with the hypothesis that this modification occurs at completion of the chaperone cycle.

Abundance of the client kinase Raf-1 in p50Cdc37 immune complexes is likely a reflection of the fact that this co-chaperone binds to Raf-1 by itself and in complex with Hsp90 (Fig. 5D). Raf-1 was present to a lower extent in AHA1 immune complexes consistent with the fact that AHA1 stimulates Hsp90 ATPase activity and rapidly drives the chaperone cycle to its completion, with concomitant maturation and dissociation of the client protein (Fig. 5D). Indeed, Raf-1 (and Hsp90) association with the AHA1-containing chaperone complex was noticeably increased when endogenous Hsp90 was knocked down and replaced by exogenously delivered (siRNA-insensitive, see figure legend) Hsp90 harboring a point mutation making it incapable of hydrolyzing ATP (E47A mutation, Fig. 5E). In this case, Raf-1 is predicted to remain trapped in AHA1-bound chaperone complexes that are unable to proceed to completion. Taken together, these data support a sequential ordering of p50Cdc37 and Hsp90 tyrosine phosphorylation events that are minimally sufficient to support a unidirectional chaperone cycle (Fig. 5F).

DISCUSSION

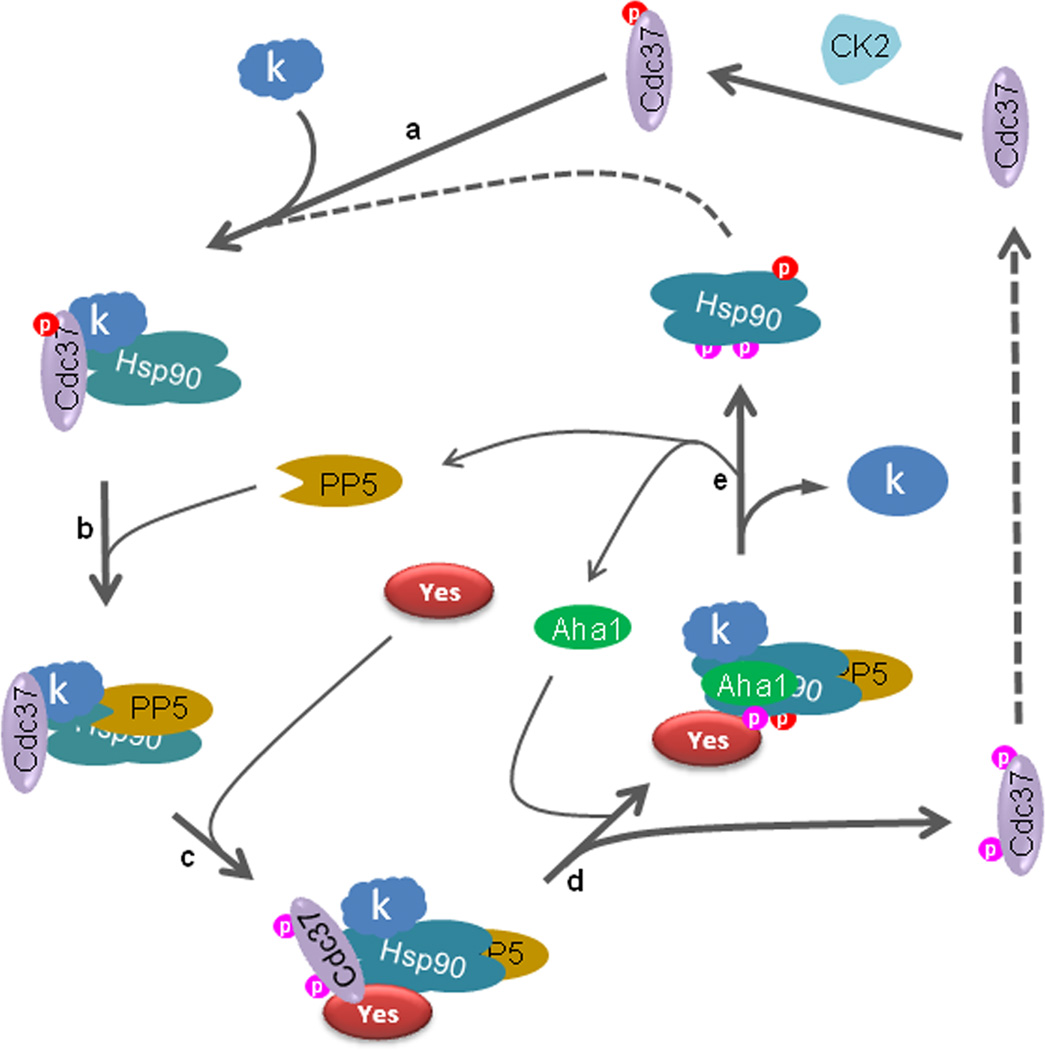

By recruiting kinase clients to the Hsp90 chaperone machine, p50Cdc37 plays an important role in the maturation of numerous protein kinases. Productive chaperoning of kinase clients requires the regulated association and dissociation of p50Cdc37 from both the client kinase and Hsp90. Association of client kinase has been suggested to require p50Cdc37 S13 phosphorylation, mediated by CK2 (Miyata and Nishida, 2004; Vaughan et al., 2008). S13 phosphorylation is also detected on uncomplexed p50Cdc37, and its dephosphorylation did not disrupt pre-assembled chaperone-kinase complexes (Vaughan et al., 2008), suggesting that additional regulatory events participate in disassembly of p50Cdc37-kinase and p50Cdc37-Hsp90 complexes in metazoans. Our current data support a model in which p50Cdc37 S13 phosphorylation and tyrosine phosphorylation together modulate this process. In this model, p50Cdc37 phosphorylation on S13 favors formation of an initial ternary complex with kinase client and Hsp90. Binding of PP5 to this complex promotes p50Cdc37 S13 dephosphorylation and favors tyrosine phosphorylation which triggers release of kinase client from p50Cdc37 (Fig. 6). It should be noted that p50Cdc37 is not tyrosine phosphorylated in yeast (data not shown). Thus, this post-translational modification is likely an adaptation of metazoans that permits additional fine tuning of p50Cdc37 activity in order to cope with an expanded kinase repertoire.

Figure 6.

A series of phosphorylation events drive the Hsp90 and p50Cdc37-mediated chaperone cycle for client kinases. Hsp90 and p50Cdc37, which is phosphorylated on S13 by CK2, bind to a client kinase (‘k’) (a). PP5 dephosphorytes p50Cdc37 on S13 (b), priming the complex for access by Yes kinase (c). Yes phosphorylates p50Cdc37 on Y298, weakening the interaction between p50Cdc37 and the client kinase (some client kinases are also released upon Y4 phosphorylation). Phosphorylation of Hsp90 on Y197 promotes dissociation of p50Cdc37 from the chaperone complex, while Hsp90 phosphorylation on Y313 induces conformational change favoring recruitment of AHA1 (d). AHA1 stimulates Hsp90 ATPase activity, driving maturation of the client kinase. Finally, Hsp90 phosphorylation on Y627 leads to dissociation of AHA1, PP5, and client kinase (e). The Hsp90 tyrosine phosphorylation events shown can be mediated by Yes (as shown by our in vitro experiments), but it is not the sole kinase capable of doing so, since Yes knockdown fails to completely abolish phosphorylation of these Hsp90 residues (data not shown). Tyrosine phosphorylated Hsp90 and p50Cdc37 are dephosphorylated by as yet unidentified phosphatase(s) allowing them to re-enter the chaperone cycle (see also Fig. S5).

Human p50Cdc37 consists of three domains, with the conserved N-terminal domain involved in interaction with kinase client, and the middle domain involved in interaction with Hsp90. No function has been ascribed to the C-terminal domain (Shao et al., 2003a). In reticulocyte lysate, p50Cdc37 consisting of only N-terminal and middle domains formed a stable complex with Hsp90 and the client heme-regulated eIF2α kinase (Shao et al., 2003a). However, we found that transfected p50Cdc37 protein lacking the C-terminal domain failed to form a stable complex with client kinases, even though truncated protein containing the middle domain bound Hsp90 as well as full length p50Cdc37 (Fig. S5A). This indicates that the p50Cdc37 C-terminal domain is necessary to stably associate with client kinases in intact cells. These discrepant findings are not likely due differences in p50Cdc37 S13 phosphorylation, since comparable levels of S13 phosphorylation are detected in vivo and in vitro (Fig. S5B). However, p50Cdc37 tyrosine phosphorylation is not seen in reticulocyte lysate (Fig. S5B).

The dynamic nature of p50Cdc37 tyrosine phosphorylation is consistent with a regulatory function for this post-translational modification. Using site-specific phospho-antibodies, we characterized two tyrosine phosphorylation sites in human p50Cdc37, one in the N-terminal domain (Y4) and the other in the C-terminal domain (Y298). Y4 phosphorylation only affected p50Cdc37 interaction with the two relatively unstable kinases examined in this study (ErbB2 and v-Src), and the equivalent Y5 mutation in yeast Cdc37 affected productive chaperoning of v-Src in yeast (but not that of the Raf-1 homolog Ste11). Since Y4F (as well as Y4A and W7A, not shown) did not support p50Cdc37 complex formation with either v-Src or ErbB2 as efficiently as did wild type, it is likely that this N-terminal motif participates in chaperoning a subset of unstable kinase clients. In contrast, Y298 phosphorylation uniformly disrupted p50Cdc37 association with all four kinases that we evaluated (ErbB2, v-Src, Cdk4, and Raf-1), suggesting a general role for C-terminal domain tyrosine phosphorylation in regulating p50Cdc37 function.

Although p50Cdc37 tyrosine phosphorylation promotes dissociation of client kinases, this modification does not perturb association with Hsp90. In order to effectively chaperone its clients, Hsp90 must proceed through a series of conformational changes coupled to ATP hydrolysis. This requires the carefully orchestrated association/dissociation of a number of co-chaperones. Since p50Cdc37 binding to Hsp90 restrains these conformational changes at an early point in the chaperone cycle and inhibits Hsp90 ATPase activity, p50Cdc37 must dissociate from Hsp90 for the chaperone process to continue. By mutating a number of Hsp90 phosphotyrosine residues that were previously identified by mass spectrometry (www.phosphosite.org), we found that the phosphomimetic mutation Y197E uniquely disrupted association of Hsp90 with p50Cdc37. We also showed that Hsp90 Y197 phosphorylation status and association with p50Cdc37/client kinase was inversely related in PBMCs, and we confirmed that in vitro phosphorylation of this residue dissociated Hsp90 and p50Cdc37. In the crystal structure of the Hsp90 N-terminal domain complexed with p50Cdc37, Y197 does not directly interact with p50Cdc37. Consequently, phosphorylation of this residue likely affects the Hsp90-p50Cdc37 complex by inducing a conformational change in Hsp90.

The co-chaperone AHA1 facilitates the Hsp90 conformational cycle and strongly activates Hsp90 ATPase activity (Panaretou et al., 2002). We showed that Hsp90 in complex with AHA1 was phosphorylated to high levels on Y313, and that phosphomimetic mutation of Y313 resulted in a dramatic increase in AHA1 association. AHA1 affinity for Hsp90-Y313E was increased 3.5-fold compared to wild type, and AHA1 stimulation of Hsp90-Y313E ATPase activity was significantly greater compared to wild type Hsp90. We propose that Hsp90 Y313 phosphorylation provides an environmentally responsive regulatable mechanism to recruit AHA1 to Hsp90, thereby stimulating Hsp90 ATPase activity and driving the chaperone cycle forward. In the crystal structure of the Hsp90 middle domain complexed with AHA1, Y313 is not directly involved in the interaction of the two proteins; rather, it is on the opposite side of the binding interface (Meyer et al., 2004). Therefore, Y313 phosphorylation likely promotes AHA1 association indirectly by affecting Hsp90 conformation.

Recently, Hsp90 in solution was shown to fluctuate stochastically between thermally determined conformational states, while ATP bound to both open and closed conformations and was unable to direct a productive conformational cycle (Ratzke et al., 2011). These data emphasize the importance of co-chaperones for maintaining proper Hsp90 function in cells. Although additional Hsp90 phosphorylation sites and other Hsp90 phosphorylating kinases have been identified, the phosphorylation events described herein provide a minimally sufficient biochemical basis to achieve co-chaperone-dependent unidirectional flow of the Hsp90-kinase chaperone cycle in higher eukaryotes (see Fig. 6), and they emphasize the importance and complexity of post-translational mechanisms for optimal function of the Hsp90 machine.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cells, Plasmids, and Antibodies

COS7 and v-Src-NIH3T3 cells were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). 293H and 293A cells were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). All cells were grown in DMEM plus 10% fetal bovine serum. FLAG-tagged p50Cdc37 in pcDNA3 vector was a kind gift from Dr. Y. Minami (University of Tokyo). Plasmids expressing truncated p50Cdc37 proteins have been described previously (Shao et al., 2003a). Point mutations were made using the QuikChange site directed mutagenesis method. To construct the yeast CDC37 expression plasmid, CDC37 promoter (855bp upstream of the start codon) and the terminator (498bp downstream of the stop codon) were cloned into HindIII/XhoIKpnI/EcoRI sites YCplac111. CDC37His6 (tagged at the C-domain) and mutated forms CDC37His6-Y5F and CDC37His6-Y5E were cloned into the XhoI/KpnI of the above plasmid. These constructs were transformed into cdc37 deletion strain XX201 containing wild-type Cdc37-GFP from YCplac33. Transformants were finally grown on solid media containing 5-fluoroorotic acid (5-FOA), in order to lose the YCplac33. ΔN-Ste11 was provided by Dr. J. Johnson (University of Idaho).

ErbB2, Raf-1, and Cdk4 antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Fyn and Yes antibodies were from BD Bioscience (San Jose, CA). Cdc37 antibody was from Thermo Scientific (Fremont, CA). Anti-phospho-tyrosine antibody 4G10 was from Upstate Biotechnology (Lake Placid, NY). Anti-pS13-Cdc37 antibody was described previously (Miyata and Nishida, 2007). Site-specific phosphotyrosine antibodies to p50Cdc37 and Hsp90 used in this study were developed in collaboration with Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA). These antibodies were validated for specificity by western blotting of specific phosphosite mutant proteins (see Figs. S1 & S4).

Immunoprecipitation and Western Blotting

Cells were transfected with Lipofectamine 2000. Twenty-four hours after transfection, (48 hours for siRNA), cells were washed with PBS and lysed. For co-immunoprecipitation, cells were lysed with Hepes buffer containing 10 mM Na2MoO4, 30 mM NaF, 2 mM β-glycerol phosphate, 2 mM sodium vanadate, 100 µM bpv(phen), and Complete protease inhibitors (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN). For p50Cdc37 tyrosine phosphorylation, cells were lysed with 1% SDS buffer, boiled for 5 min, and then diluted to 0.1% SDS. M2 anti-FLAG antibody-linked beads were used to immunoprecipitate p50Cdc37 proteins. Proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred onto PVDF membrane. Membranes were probed with indicated antibodies. For quantitation, films with appropriate exposure were scanned by densitometry, band densities were obtained using NIH Image software, and standard deviations were calculated in Excel. Where graphical quantification of band densities is shown, experiments were repeated twice.

In Vitro Kinase Assay

ErbB2-K753A was expressed in COS7 cells and immunoprecipitated with mouse anti-ErbB2 antibodies (Ab-3 and Ab-5, EMD Biosciences, San Diego, CA) pre-bound to protein G-agarose beads (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The beads were washed 3 times with lysis buffer (20 mM Hepes, pH7.2, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.1% Nonidet P40, 10 mM Na2MoO4, Complete protease inhibitors and PhosSTOP phosphatase inhibitors [Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN]), and then once with MOPS buffer (8 mM MOPS, pH7.0, 100 mM NaCl, 0.2 mM EDTA, 10 mM Na2MoO4). The beads were resuspended in 50 µl buffer containing 10 ng purified Yes kinase protein (Millipore, Billerica, MA) according manufacturer’s protocol, and incubated at 30 °C for 1 hour with stirring. After incubation, beads were spun down and supernatant was transferred to a new tube and mixed with 5x SDS-sample buffer. Beads were washed twice with lysis buffer, resuspended in SDS-sample buffer, and heated at 100 °C for 5 minutes to elute remaining proteins. Eluate and supernatant were examined by western blot as described.

Isolation of Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells and Lymphocyte Activation

Buffy coats were provided anonymously as a by-product of whole blood donations from paid healthy volunteer donors through a National Institutes of Health Institutional Review Board–approved protocol, and they were processed to obtain the mononuclear cell fraction. Mononuclear cells were pelleted and frozen immediately to obtain the resting cell population, or activated by incubating overnight at 37° C in medium containing phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) (1 ng/ml) and ionomycin (1 µg/ml).

v-Src Activity in Yeast

XX201 yeast strain expressing Cdc37-His6 or various cdc37 mutant (Y5F or Y5E) alleles were transformed with YpRS316v-SRC (Nathan and Lindquist, 1995). v-SRC is under control of the GAL1 promoter. Its activity was analyzed as described previously (Panaretou et al., 2002), with the exception that yeast cells were grown on 2% glucose in order to repress the GAL1 promoter. v-Src protein levels were detected with EC10 mouse antibody (Millipore, Billerica, MA) , and v-Src activity was assessed by blotting yeast lysates with 4G10 mouse anti-phosphotyrosine antibody (Millipore). Cdc37-His6 was detected with Tetra-His monoclonal antibody (Qiagen, Valencia, CA).

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

Tyrosine phosphorylation of p50Cdc37 promotes its dissociation from client kinase

Hsp90 Y197 phosphorylation causes p50Cdc37 dissociation from the chaperone complex

Hsp90 Y313 phosphorylation enhances binding to ATPase activating co-chaperone AHA1

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We are grateful to Dr Susan Leitman and the Department of Transfusion Medicine, Clinical Center, National Institutes of Health, for their help in obtaining and processing peripheral blood leukocytes from healthy donors.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Abbas-Terki T, Donze O, Picard D. The molecular chaperone Cdc37 is required for Ste11 function and pheromone-induced cell cycle arrest. FEBS Lett. 2000;467:111–116. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01134-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang L, Ricketson D, Getubig L, Darimont B. Unliganded and hormone-bound glucocorticoid receptors interact with distinct hydrophobic sites in the Hsp90 C-terminal domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:18487–18492. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609163103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore TD, Radke K, Martin GS. Tyrosine phosphorylation of a 50K cellular polypeptide associated with the Rous sarcoma virus transforming protein pp60src. Mol Cell Biol. 1982;2:199–206. doi: 10.1128/mcb.2.2.199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harst A, Lin H, Obermann WM. Aha1 competes with Hop, p50 and p23 for binding to the molecular chaperone Hsp90 and contributes to kinase and hormone receptor activation. Biochem J. 2005;387:789–796. doi: 10.1042/BJ20041283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koulov AV, Lapointe P, Lu B, Razvi A, Coppinger J, Dong MQ, Matteson J, Laister R, Arrowsmith C, Yates JR, 3rd, et al. Biological and structural basis for Aha1 regulation of Hsp90 ATPase activity in maintaining proteostasis in the human disease cystic fibrosis. Mol Biol Cell. 2010;21:871–884. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E09-12-1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer P, Prodromou C, Liao C, Hu B, Mark Roe S, Vaughan CK, Vlasic I, Panaretou B, Piper PW, Pearl LH. Structural basis for recruitment of the ATPase activator Aha1 to the Hsp90 chaperone machinery. Embo J. 2004;23:511–519. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyata Y, Nishida E. CK2 controls multiple protein kinases by phosphorylating a kinase-targeting molecular chaperone, Cdc37. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:4065–4074. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.9.4065-4074.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyata Y, Nishida E. Analysis of the CK2-dependent phosphorylation of serine 13 in Cdc37 using a phospho-specific antibody and phospho-affinity gel electrophoresis. Febs J. 2007;274:5690–5703. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.06090.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mollapour M, Neckers L. Post-translational modifications of Hsp90 and their contributions to chaperone regulation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2011.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nathan DF, Lindquist S. Mutational analysis of Hsp90 function: interactions with a steroid receptor and a protein kinase. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:3917–3925. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.7.3917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panaretou B, Siligardi G, Meyer P, Maloney A, Sullivan JK, Singh S, Millson SH, Clarke PA, Naaby-Hansen S, Stein R, et al. Activation of the ATPase activity of hsp90 by the stress-regulated cochaperone aha1. Mol Cell. 2002;10:1307–1318. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00785-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratzke C, Berkemeier F, Hugel T. Heat shock protein 90's mechanochemical cycle is dominated by thermal fluctuations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1107930108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rush J, Moritz A, Lee KA, Guo A, Goss VL, Spek EJ, Zhang H, Zha XM, Polakiewicz RD, Comb MJ. Immunoaffinity profiling of tyrosine phosphorylation in cancer cells. Nature biotechnology. 2005;23:94–101. doi: 10.1038/nbt1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnaider T, Somogyi J, Csermely P, Szamel M. The Hsp90-specific inhibitor geldanamycin selectively disrupts kinase-mediated signaling events of T-lymphocyte activation. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2000;5:52–61. doi: 10.1043/1355-8145(2000)005<0052:THSIGS>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sgobba M, Degliesposti G, Ferrari AM, Rastelli G. Structural models and binding site prediction of the C-terminal domain of human Hsp90: a new target for anticancer drugs. Chem Biol Drug Des. 2008;71:420–433. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2008.00650.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao J, Irwin A, Hartson SD, Matts RL. Functional dissection of cdc37: characterization of domain structure and amino acid residues critical for protein kinase binding. Biochemistry. 2003a;42:12577–12588. doi: 10.1021/bi035138j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao J, Prince T, Hartson SD, Matts RL. Phosphorylation of serine 13 is required for the proper function of the Hsp90 co-chaperone, Cdc37. J Biol Chem. 2003b;278:38117–38120. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C300330200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiau AK, Harris SF, Southworth DR, Agard DA. Structural Analysis of E. coli hsp90 reveals dramatic nucleotide-dependent conformational rearrangements. Cell. 2006;127:329–340. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siligardi G, Panaretou B, Meyer P, Singh S, Woolfson DN, Piper PW, Pearl LH, Prodromou C. Regulation of Hsp90 ATPase activity by the co-chaperone Cdc37p/p50cdc37. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:20151–20159. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201287200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taipale M, Jarosz DF, Lindquist S. HSP90 at the hub of protein homeostasis: emerging mechanistic insights. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11:515–528. doi: 10.1038/nrm2918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas SM, Brugge JS. Cellular functions regulated by Src family kinases. Annual review of cell and developmental biology. 1997;13:513–609. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.13.1.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan CK, Mollapour M, Smith JR, Truman A, Hu B, Good VM, Panaretou B, Neckers L, Clarke PA, Workman P, et al. Hsp90-dependent activation of protein kinases is regulated by chaperone-targeted dephosphorylation of Cdc37. Mol Cell. 2008;31:886–895. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.