Abstract

Huntington’s disease (HD) is a devastating autosomal-dominant neurodegenerative disorder initiated by an abnormally expanded polyglutamine in the huntingtin protein. Determining the contribution of specific factors to the pathogenesis of HD should provide rational targets for therapeutic intervention. One suggested contributor is the type 2 transglutaminase (TG2), a multifunctional calcium dependent enzyme. A role for TG2 in HD has been suggested because a polypeptide-bound glutamine is a rate-limiting factor for a TG2-catalyzed reaction, and TG2 can cross-link mutant huntingtin in vitro. Further, TG2 is up regulated in brain areas affected in HD. The objective of this study was to further examine the contribution of TG2 as a potential modifier of HD pathogenesis and its validity as a therapeutic target in HD. In particular our goal was to determine whether an increase in TG2 level, as documented in human HD brains, modulates the well-characterized phenotype of the R6/2 HD mouse model. To accomplish this objective a genetic cross was performed between R6/2 mice and an established transgenic mouse line that constitutively expresses human TG2 (hTG2) under control of the prion promoter. Constitutive expression of hTG2 did not affect the onset and progression of the behavioral and neuropathological HD phenotype of R6/2 mice. We found no alterations in body weight changes, rotarod performances, grip strength, overall activity, and no significant effect on the neuropathological features of R6/2 mice. Overall the results of this study suggest that an increase in hTG2 expression does not significantly modify the pathology of HD.

Keywords: Huntington’s disease, transglutaminase, mouse model, phenotype, modifiers, aggregates

Introduction

Huntington’s disease (HD) is a devastating autosomal-dominant neurodegenerative disorder caused by an abnormal and unstable CAG expansion within the sequence of the gene encoding for huntingtin, a large phylogenetically conserved protein (The Huntington’s Disease Collaborating Group, 1993). The clinical presentation of HD includes progressive involuntary movements, psychiatric disorders, and dementia (Roos, 2010). Currently there is no effective treatment to slow the progression or to delay the onset of HD, and treatments only ameliorate the symptoms associated with this invariably lethal disease. Although the huntingtin protein is expressed ubiquitously by neurons, the clinical symptoms are paralleled by a relatively selective pattern of neurodegeneration, with striatal medium spiny GABAergic projection neurons (MSNs) exhibiting early degeneration and atrophy (Vonsattel et al., 1985). Degenerative changes in the cortex also occur in the early phases of HD and careful neuropathologic examinations of advanced HD specimens reveal evidence of neurodegeneration in many brain regions (Rosas et al., 2004; Rosas et al., 2003; Rosas et al., 2010; Rosas et al., 2002). Further, an important neuropathological hallmark of HD is the presence of intranuclear and cytoplasmic aggregates that consist primarily of the mutant huntingtin protein (Davies et al., 1997; DiFiglia et al., 1997). The underlying cause of the relatively selective neurodegeneration in HD is not clear, although the expanded polyglutamine domain in huntingtin is thought to confer a toxic gain of function on the protein (Fischbeck, 2001). The detrimental effects of the mutant huntingtin have been associated with potential proximate pathogenic mechanisms including abnormal transcriptional activity (Luthi-Carter et al., 2000), impaired axonal transport (DiFiglia et al., 1995; Trushina et al., 2004), N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor-mediated excitotoxicity (Tallaksen-Greene et al., 2010; Young et al., 1988), impaired vesicle trafficking (Kegel et al., 2000), and mitochondrial dysfunction (Beal, 1994; Beal, 1996; Choo et al., 2004; Gu et al., 1996; Panov et al., 1999). Thus, the etiology of HD likely involves a complex interplay between multiple mechanisms, and determining the contribution of specific factors to the pathogenesis of HD should provide rational targets for therapeutic intervention.

Green suggested that an increase in the number of glutamine residues beyond a certain threshold may result in a protein becoming a transglutaminase (TG) substrate (Green, 1993). Indeed, one suggested contributor to the dysfunction and loss of neurons in HD is the type 2 TG (TG2, also called tissue transglutaminase, tTG), a multifunctional calcium dependent enzyme and member of the transglutaminase family (Iismaa et al., 2009; Lesort et al., 2000a; Lorand and Graham, 2003). TG2 is the primary transglutaminase expressed in the brain, where it is predominantly expressed in neurons (Lesort et al., 1999). TG2 can catalyze the acyl transfer reaction between the γ-carboxamide group of a polypeptide-bound glutamine and the ε-amino group of a polypeptide bound lysine residue to form an Nε-(γ-glutamyl)lysine isopeptide bond, which results in both intra and intermolecular cross-links (Greenberg et al., 1991; Lorand and Conrad, 1984; Lorand and Graham, 2003). TG2 can also catalyze the formation of covalent (γ-glutamyl)polyamine bond between a polyamine and a glutamine residue, or the deamination of glutamine residues in protein substrates (Greenberg et al., 1991). TG2 also functions as a signal transducing G protein, as TG2 hydrolyzes GTP and mediates intracellular signaling (Zhang et al., 1998; Zhang et al., 1999). A role for TG2 in HD has been suggested because a polypeptide-bound glutamine is the primary determining factor for a TG2-catalyzed reaction, and TG2 can cross-link mutant huntingtin in vitro (Kahlem et al., 1998a). Further, TG2 is up regulated in brain areas affected in HD (Lesort et al., 1999), and levels of its cross-linked product Nε-(γ-glutamyl)-l-lysine are increased several fold in HD brains and cerebrospinal fluid (Jeitner et al., 2001). Furthermore, the genetic ablation of TG2 delayed disease progression in HD mouse models (Mastroberardino et al., 2002). Initially it was proposed that the formation of insoluble protein aggregates accounts for the toxic action of TG2 (Gentile et al., 1998), while other studies have proposed a role for TG2 in the formation of autophagosomes (Rossin et al., 2011), mitochondrial dysfunction (Kim et al., 2005; Lesort et al., 2000b), and more recently in the transcriptional dysregulation associated with HD (McConoughey et al., 2010).

The objective of this study was to further examine the contribution of TG2 as a potential modifier of HD pathogenesis and its validity as a therapeutic target in HD. In particular our goal was to determine whether an increase in TG2 level, as documented in human HD brains, modulates the well-characterized phenotype of the R6/2 HD mouse model (Ferrante et al., 2000; Hockly et al., 2003; Mangiarini et al., 1996). To accomplish this objective a genetic cross was performed between R6/2 mice and an established transgenic mouse line that constitutively expresses human TG2 (hTG2) primarily in neurons (Tucholski et al., 2006). The effects of hTG2 expression on a number of behavioral phenotypes and neuropathological features of R6/2 mice were examined. The results reveal that an increase in hTG2 does not significantly modify the onset nor the progression of the behavioral phenotype and neuropathological features of the R6/2 mice.

Material and methods

Materials

The bicinchoninic acid assay (BCA) and the peroxidase substrate chemiluminescence (ECL) kits were obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Rockford, IL, USA); the Vectastain Elite kit was obtained from the Vector Laboratories (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). All other chemicals were purchased from Sigma (St Louis, MO, USA). Antibodies against the following proteins were obtained from the indicated sources: NeuN, Chemicon International (Temecula, CA, USA); GFAP, α-tubulin protein, and actin protein, Sigma (St Louis, MO, USA); N-terminal of huntingtin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA); peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG, peroxidase-conjugated-goat anti-rabbit IgG, and peroxidase-conjugated-donkey anti-rat IgG were purchased from Jackson ImmunoReseach Laboratories Inc. (West Grove, PA, USA). The rat TGMO1 and TGMO2 antibodies against TG2 were generously provided by Dr. Gail Johnson (University of Rochester).

Experimental animals

Mice overexpressing human TG2 in the C57Bl/6 genetic background were characterized previously (Tucholski et al., 2006). In Brief, the hTG2 transgene was driven by the murine prion promoter (MoPrP) from the MoPrP.XhoI expression transgenic vector, hTG2 transgenic mice were generated by pronuclear microinjection of fertilized C57BL/6 oocytes with NotI-linearized DNA transgenic construct that contained cDNA for hTG2 (Tucholski et al., 2006). Expression analysis revealed that hTG2 mRNA and protein are predominantly produced and expressed in mouse brain (Tucholski et al., 2006). hTG2 transgenic mice are born at the expected Mendelian frequency, and do not show spontaneous pathology or obvious phenotype. hTG2 mice present a normal appearing brain and no discernible differences in the cerebrovasculature of hTG2 mice were detected when compared with wild type mice (Filiano et al., 2008; Filiano et al., 2010; Tucholski et al., 2006).

The R6/2 mouse model of HD was originally developed by Dr. G. Bates’s laboratory, and has been extensively characterized (Hockly et al., 2003; Mangiarini et al., 1996). The R6/2 mouse model offers robust behavioral and neuropathological outcome measures (Mangiarini et al., 1996). R6/2 mice were initially developed in a mixed genetic background and were subsequently backcrossed to C57Bl/6 mice to place the R6/2 transgene on an isogenic C57Bl/6 background (Morton et al., 2009). Because expanded CAG repeats are inherently unstable and the CAG repeat number has a tendency to increase upon transmission, backcrossing the R6/2 mice has resulted in an elongation in the CAG repeat size in the transgene to ~270 CAG repeats in the R6/2 line used in this study (Morton et al., 2009). This R6/2 variant (R6/2B) exhibits pathological features more similar to HD, and may be a more faithful model of HD than the parent R6/2 line (Morton et al., 2009). The R6/2B line on the C57Bl/6 genetic background was generously provided by Dr. G. Bates and was obtained from a colony maintained by the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA). The line was maintained on this background in our vivarium. To examine the effect of increasing neuronal hTG2 on the R6/2 phenotype, female hTG2 mice were crossed with male R6/2 mice to produce littermate experimental mice that are either wild type (WT:WT), carry only the R6/2 transgene (R6/2:WT), carry only the hTG2 transgene (WT:hTG2), or carry both transgenes (R6/2:hTG2). Experimental mice were weaned at 3 weeks of age. Mice were housed in groups of five per cage, at an ambient temperature of 23°C with a 12 h light-dark cycle, and no specific environmental enrichment was added in the cages. All animals had unlimited access to water and mouse chow, and starting at ~10-12 weeks of age powdered chow was mixed with water and mash food was placed in the bottom of the cages. All mice were cared for according to the principles and guidelines of the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. The experimental procedures strictly followed protocols approved by the University of Alabama at Birmingham Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Mouse genotyping and CAG repeat size

Prior to weaning R6/2 mice were identified by PCR of tail-tip DNA as described previously (Mangiarini et al., 1996), and the genotype status of the hTG2 mice was determined according to a protocol previously described (Tucholski et al., 2006). Expanded CAG repeats are inherently unstable and variation in their lengths may significantly affect the onset and progression of the disease phenotype (Morton et al., 2009). To control for this potential heterogeneity, CAG repeat numbers in the R6/2 transgene were measured by Laragen (Los Angeles, CA) in randomly selected R6/2:WT and R6/2:hTG2 experimental mice.

Body weight analysis

To determine whether overexpression of hTG2 affects the onset and extent of weight loss, starting at 5 weeks of age mice of the different genotypes were weighted at the nearest 0.01 gr. Mice were weighed during the hours of 8-11 AM to reduce variation caused by daily eating and drinking patterns.

Behavioral analysis

Male R6/2 and wild type littermate mice that carry or not the hTG2 transgene were aged and underwent prospective serial behavioral evaluations using standardized approaches to therapeutic trials in HD mice and a series of well-established quantitative tests. Mice of the different genotypes were assessed at 50, 75, 100, and 125 days of age.

Rotarod Performance

Motor coordination was assessed using an Ugo Basile 7650 accelerating Rotarod (Comerio VA, Italy). For testing, mice were placed on the rod with an accelerating rotating speed from 4 to 40 rpm, and mice were allowed to run on the rod for a maximal period of 10 minutes. Rotarod tests were performed in two phases: training and testing. During the training phase (first day) mice were subjected to three trials with a period of rest of 30 minutes between each trial. During this training phase mice were allowed to become accustomed to the rod. Subsequently, for the next five days, mice were tested with one trial per day (trials 4 to 8).

Grip strength

Grip strength analysis was performed to assess the muscular strength or motor impersistence. The muscular strength of forelimbs and four limbs muscular strength of mice from the different genotype groups was analyzed using grip strength meter as described previously (Perry et al., 2010). In brief, the maximum force (gram) pulled by the mouse forelimbs and four limbs were recorded by a strength meter, each mouse performs three consecutive tests as low scores may be due to the mouse failing to grip the strength meter effectively, or prematurely releasing we used the highest of the three scores for analysis (Hockly et al., 2003).

Cage activity

The spontaneous horizontal and rearing locomotor activities and rhythm activities of the mice was assessed by an infrared beam activity monitor. One mouse was placed in each standard (29 cm L × 19 cm W × 13 cm H) micro-isolator cage with enough food and water for one week. A total of eight beams spanned the width of each cage. Six lower beams, evenly spaced (4.5 cm apart, 2.5 cm from cage floor), would be broken by mice normally walking the length of the cage, and two upper beams located near the cage ends (1.8 cm from each cage wall and 7.0 cm above cage floor) could only be broken by rearing or climbing upside-down on the cage rack and could not be broken by mice feeding or drinking. Mice were assessed at 50, 75, 100, and 125 days of age, the apparatus simultaneously and continuously monitored beam breaks. Data was recorded by an IBM personal computer programmed to store data at 2 minutes intervals for each of the beams. Data from the first three days and nights were not used for the statistical analyses as mice need to acclimate to their cage environment. Data is expressed as the average of upper or bottom beams broken over a 24 h period (spontaneous activity and rearing locomotor activity), or over 12 h dark and 12 h light periods (rhythm activity) measured.

Brain harvesting and storage

Mice were deeply anesthetized and sacrificed following the University of Alabama at Birmingham Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved protocol. Brains were extracted immediately after decapitation and placed in 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde in 0.1M phosphate buffer (PB), pH 7.4, for 48 h at 4°C. Brains were then cryoprotected in 30% (w/v) Sucrose in 0.1M PB for an additional 48 h at 4°C. The brain was serially sectioned at 40 μm coronally from approximately Bregma +1.5 mm to Bregma −2.5 mm, throughout the entire striatum. Sections were collected and stored at −20°C in PB containing ethylene glycol.

Immunohistochemistry

Free floating sections were washed in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and then quenched with 0.3% (v/v) H202 in water for 30 min at 23°C. Sections were then washed with PBS and blocked with 6% (v/v) normal donkey serum (NDS) and 0.3% (v/v) Triton X-100 in PBS for 1 h at 23°C. Sections were incubated with the N-terminal huntingtin protein antibody at a dilution of 1:1,000 dilution with 6% (v/v) NDS and 0.3% (v/v) Triton X-100 in PBS for 24 h at 23°C. Sections were washed with PBS and incubated with a biotinylated donkey anti-goat secondary antibody with 6% (v/v) NDS and 0.3% (v/v) Triton X-100 in PBS for 2 h at 23°C. To estimate neuronal number, adjacent sections were stained with the primary specific neuronal nuclei antibody (NeuN) at a dilution of 1:2,000 using normal goat serum (NGS) as blocking solution and a biotinylated goat anti-mouse secondary antibody (Vector Laboratories). Sections were then washed with PBS and incubated with ExtrAvadin-Peroxidase (Sigma) with 6% (v/v) NDS and 0.3% (v/v) Triton X-100 in PBS for 2 h at 23°C. Detection of immunoreactivity was performed using the Vectastain Elite kit, and diaminobenzidine substrate was used as the chromogen according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Sections were mounted on gelatin-coated slides, air dried and cleared in xylene. Coverslips were affixed with DPX mounting medium.

Stereology

For stereological analysis, the experimenter was blinded to the identity of each sample. Unbiased stereological counts of striatal neurons were obtained from the striatum using the StereoInvestigator software (MicroBrightField, Colchester, VT). The optical fractionator method was used to generate an estimate of neuronal number of NeuN-immunoreactive cells counted in an unbiased selection of serial sections in a defined volume of the striatum. Striatal borders were delineated by reference to a mouse brain atlas, and defined to encompass both the dorsal and ventral striatum. Striatal volume was reconstructed by the StereoInvestigator software using the Cavalieri principle. Serially cut coronal tissue sections (every eighth section for a total of 12 sections) were analyzed throughout the entire striatum of animals in each cohort. The number of neurons (on NeuN-stained sections) and huntingtin protein aggregates (on huntingtin protein-stained sections) within the entire striatum were quantified using the optical fractionator method with dissectors placed randomly according to a 500 μm × 500 μm grid, resulting in 10-12 dissectors per section in the striatum. Dissectors were 5625 μm2 for neuron counting and 1600 μm2 for counting of huntingtin protein aggregates, which resulted in an average of 15 objects per dissector.

Western blot and immunoblotting

Tissues from the different brain regions and liver were homogenized in lysis buffer [50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5% NonidetP-40, 0.1mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride and a 10 μg/ml concentration of each of aprotinin, leupeptine and pepstatin] with a glass/Teflon Dounce homogenizer, prior to being sonicated on ice and spun at 2,000 g for 10 min at 4°C. Protein concentration of the supernatant was determined using the BCA method, and cellular lysates were diluted to a final concentration of 1 mg/ml in 2X reducing stop buffer [0.25 M Tris-HCl (pH7.5), 2% SDS, 25 mM dithiothreitol, 5 mM EGTA, 5 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol and 0.01% bromophenol blue as tracking dye] and incubated in a boiling water bath for 5 min. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE on 10% gel then transferred to nitrocellulose. Membranes were probed with the indicated primary antibodies followed by incubation with horse-radish peroxidase conjugated secondary antibodies according to standard protocols. Blots were developed using peroxidase substrate chemiluminescence.

RNA analyses

A syber green based method of determining the mRNA levels of R6/2 transgene levels was developed by exploiting differences between the sequence of R6/2 mRNA and the endogenous mouse Hdh mRNA. The primers GGC CGC TCA GGT TCT GCT TTT AC and GCT CAG CAC CGG GGC AAT G were used. Validation of assay included: 1) the lack of PCR product in no reverse transcriptase controls, 2) the lack of PCR signal from cDNA made from wild type striatal RNA samples from mice that lack the R6/2 transgene, 3) verification that only a single PCR product resulted by both agarose electropheresis and the use of a melting temperature dissociation curve and 4) a determination of range of dilutions of striatal R6/2 cDNAs that provides linear readings for R6/2 transgene levels by the assay. RNA was extracted from snap frozen striata and cortex of 6 double transgenic, 5 R6/2 single transgenic, 6 tTG single transgenic and 7 wild type mice by homogenization in Trizol reagent and preparation of total RNA by the manufacturer’s instructions (Invitrogen) cDNA was made from 200 ng of total RNA from each mouse with the AppliedBiosystems High Capacity Reverse Transcription Kit. Each cDNA was used at a 1:10 dilution and triplicates of each sample were analyzed by QRTPCR using the SYBR@ green master mix (Appliedbiosystems) and each sample was compared to the mouse beta actin QRTPCR control (Appliedbiosystems) as an internal loading control.

Statistical analyses

All behavioral studies were performed blind to the hTG2 genotype. Comparisons between groups were performed using one-way and two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with post-hoc comparisons made using the Bonferroni honestly significant difference test when P<0.05. For pairwise comparisons Student’s t-tests were performed. All immunohistochemistry and stereology studies were performed blind to genotype. Comparisons of groups were performed on stereology data and NII striatal density using two tailed Student’s t-tests with confidence intervals of 95%.

Results

Expression of the R6/2 transgene is not altered in the double transgenic mice

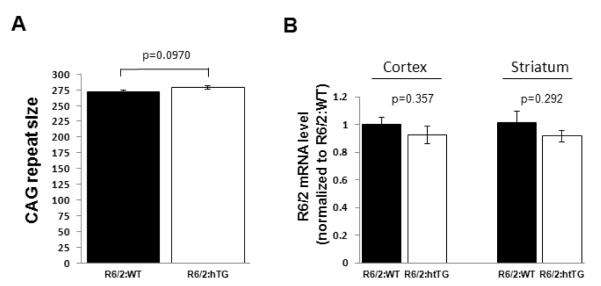

The R6/2 mouse model of HD has been widely used in the HD field, as it presents an early-onset and robust phenotype providing clear outcome measures for preclinical studies (Davies et al., 1997; Hockly et al., 2003; Mangiarini et al., 1996). hTG2 mice constitutively express human transglutaminase 2 under the control of the prion promoter, and have been described previously (Tucholski et al., 2006). These mice express hTG2 primarily in CNS neurons, and do not present spontaneous pathology or overt phenotype (Tucholski et al., 2006). The hTG2 mouse model was developed to explore the role of TG2 in the nervous system and its contribution to neuropathological processes, and was used to demonstrate that hTG2 overexpression facilitates the kainic acid-mediated hippocampal neuronal damage (Tucholski et al., 2006). In the present study we used these mouse lines to examine whether an increase in TG2 expression modulates the disease progression of the R6/2 mouse model of HD. Male R6/2 mice were bred with females hTG2 mice to generate experimental mice of four different genotypes (R6/2:WT; WT:hTG2; double transgenic R6/2:hTG2, and wild-type littermate). Both the R6/2 and hTG2 mouse lines are on the C57BL/6 background, limiting the interaction of confounding behavioral traits attributable to allele difference in the inbred strain’s genome when crossing the mice. The CAG repeat sizes of the R6/2 transgene were measured in 16 and 15 randomly selected R6/2:WT and R6/2:hTG2 experimental mice, respectively, and were not significantly different between the two experimental groups (CAG repeat sizes: 271±3 for R6/2:WT mice, and 279±3 for R6/2:hTG2 mice; pairwise comparison, P=0.097) (Figure 1A). Using quantitative real time PCR we show that the presence of the hTG2 transgene did not significantly affect expression levels of the R6/2 transgene (Figure 1B) in either the cortex (pairwise comparison, p=0.36) or the striatum (pairwise comparison, p=0.29) (Figure 1B).

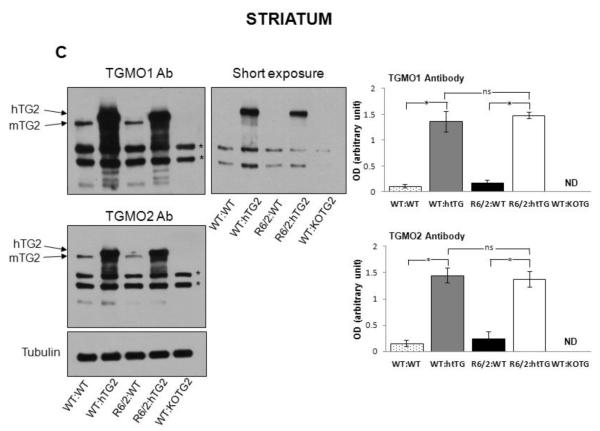

Figure 1. CAG repeat size, transgene levels and TG2 expression.

(A) CAG repeat sizes in the R6/2 transgene were not significantly different (P=0.097) between R6/2 mice that do not express hTG2 (R6/2:WT; n=16) or express the hTG2 transgene (R6/2:hTG2; n=15). Data are presented as mean ± SEM. (B) Expression levels of the R6/2 mRNA in the cortex and striatum of R6/2:WT (n=5) and R6/2:hTG2 (n=6) mice was determined using quantitative real time PCR. No significant difference was detected between the different groups, cortex (pairwise comparison, P=0.36) and striatum (pairwise comparison, P=0.29). Data are presented as mean ± SEM. (C-D) Representation immunoblots with the TGMO1 or TGMO2 antibodies from a typical experiment and quantitative analysis demonstrating that there was no significant effect of the R6/2 transgene on the robust expression of the hTG2 transgene in the striatum (C) and in the cortex (D) of R6/2:hTG2 mice when compared to WT:hTG2 mice. There was also no significant effect of the R6/2 transgene on the expression of endogenous mTG2 in the striatum (C) and cortex (D) of R6/2:WT mice when compared to WT:WT mice. Tubulin immunoreactivity demonstrated that similar amount of proteins from the different cell homogenates were loaded into the different lanes of the gels and was used to normalized hTG2 and mTG2 immunoreactivities. Tissues from TG2 knockout mice (WT:KOTG2) were used to demonstrate the specificity of the antibodies against human TG2 (hTG2) and murine TG2 (mTG2). In (C) and (D) * denotes non-specific reactivity of the TGMO1 and TGMO2 antibodies, and 20 μg of total protein from the striatum or the cortex were loaded in each lane. Data are presented as mean ± SEM from 3 independent experiments. ND: not detected. (E) Endogenous mTG2 expression was robust in the liver of mice from the different groups, but as expected not detected in liver from TG2 knockout mice (WT:KOTG2). 10 μg of total liver protein were loaded in each lane. hTG2 was not detected in the liver samples, and hTG2 transgene expression was essentially limited to CNS neurons. Arrow indicates where hTG2 transgene product should be identified.

The R6/2 transgene does not alter expression of hTG2 in the double transgenic mice

Transcriptional dysregulation is potentially an important underlying mechanism in HD pathogenesis, and has been well described in both HD patient brains and R6/2 mouse model (Luthi-Carter et al., 2002a; Luthi-Carter et al., 2002b; Olson et al., 1995); therefore it was important to determine whether expression of the hTG2 transgene is altered in the double transgenic mice. The expression of TG2 in the striatum, cortex and liver of ~18 weeks of age mice was examined for all four different genotypes. Western blotting was performed using the TGMO1 and TGMO2 antibodies that recognize both human TG2 (~80 kDa) and mouse TG2 (~77 kDa). Tissues from TG2 knockout mice (WT:KOTG2) were used to demonstrate the specificity of the TGMO1 and TGMO2 antibodies against human TG2 (hTG2) and murine TG2 (mTG2). Representative immunoblots are presented in figure 1C-E. Quantitative analyses of three independent experiments show, as expected, that in both the striatum (Figure 1C) and cortex (Figure 1D) the expression levels of the TG2 protein were robustly increased in WT:hTG2 and R6/2:hTG2 mice when compared to WT:WT and R6/2:WT mice, respectively. These findings are in line with the initial characterization of the hTG2 mice revealing that the protein was active, and in vitro TG activity measured in the brains from hTG2 mice was significantly higher when compared to the TG activity measured in the brains from wild type mice (Tucholski et al., 2006). Further analyses of our immunoblotting results revealed no significant difference in the level of hTG2 between the double transgenic mice R6/2:hTG2 and WT:hTG2 mice, providing evidence that the R6/2 transgene did not affect the expression level of hTG2 (R6/2:hTG2 versus WT:hTG2, pairwise comparisons, striatum: TGMO1, p=0.67; TGMO2, p=0.38; cortex: TGMO1 P=0.96, TGMO2 p=0.54) (Figure 1C,D). Immunoblots of liver lysates from mice of all four genotypes revealed a strong immunoreactive band corresponding to the endogenous murine TG2, while the hTG2 transgene was below threshold of detection (Figure 1E). These observations are consistent with previous findings reporting a robust expression of endogenous TG2 in murine hepatocytes, and with the initial characterization of hTG2 mice revealing that expression of the hTG2 transgene is essentially restricted to CNS neurons (Tucholski et al., 2006). Additionally previous immunocytochemical characterization of hTG2 subcellular distribution in mice overexpressing hTG2 revealed that the enzyme was essentially excluded from the nucleus (Filiano et al., 2010).

Constitutive expression of hTG2 does not delay onset or ameliorate weight loss of R6/2 mice

Weight loss is a characteristic symptom in HD patients (Marder et al., 2009), and progressive loss of body weight is a consistent and robust feature of the R6/2 mouse model (Mangiarini et al., 1996; Perry et al., 2010). Starting at 38 days of age, males of all four genotypes were weighed repeatedly until R6/2 mice have lost ~20% of their maximum body weight. R6/2 body weight reached a maximum at ~85 days of age and then, as expected, progressively declined when compared with wild type mice (F(1,656)=1298, p<0.0001) (Figure 2). Constitutive expression of hTG2 did not significantly affect the rate of weight gain of wild type mice (F(1,410)=0.31, p=0.58). Overexpression of hTG2 did not affect the rate of the R6/2 weight loss, and both the double transgenic mice and R6/2 mice lose ~20% of their maximal weight at similar age (F(1,506)=0.95, p=0.33) (Figure 2). Thus, constitutive expression of hTG2 does not alter the onset and extent of weight loss in the R6/2 mice.

Figure 2. Constitutive expression of hTG2 does not alter the onset or extent of body weight loss in R6/2 mice.

Body weights of male WT:WT; WT:hTG2; R6/2:WT and R6/2:hTG2 mice. Weight loss of R6/2 mice is not altered by the constitutive expression of hTG2. Data are presented as mean ± SEM.

Next we examined whether the constitutive expression of hTG2 modulates physiological features that are altered in R6/2 mice, such as skeletal muscles, body temperature and blood glucose. There was also no obvious effect of the hTG2 genotype on the overall atrophy of skeletal muscles observed in the R6/2 mice, and further hTG2 did not affect the reduced body temperature (WT:WT=37.0±0.2; R6/2:WT=36.1±0.2; R6/2:hTG2=36.4±0.2 C°, pairwise comparison R6/2:WT versus R6/2:hTG2, p=0.81), or the elevated blood glucose of R6/2 mice (WT:WT=106±6; R6/2:WT=456±32; R6/2:hTG2=474±47 mg/dl, pairwise comparison R6/2:WT versus R6/2:hTG2, p=0.73) measured between 130 and 157 days of age.

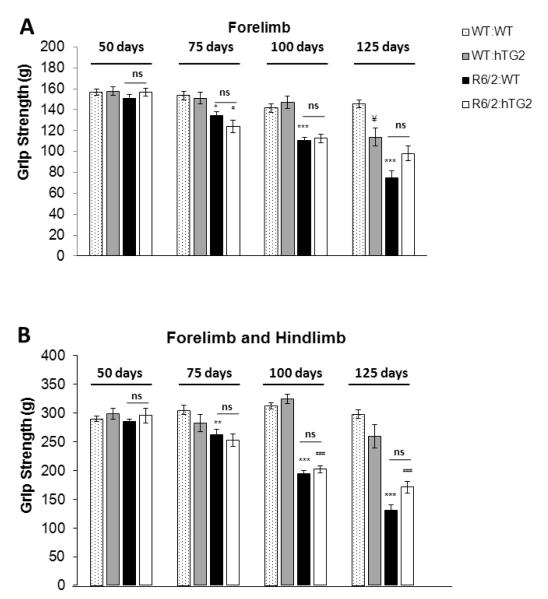

Constitutive expression of hTG2 does not modify the behavioral phenotype of R6/2 mice

The progressive behavioral phenotype of the R6/2 mouse model has been extensively characterized with a panel of standardized quantitative tests (Hockly et al., 2003). Using these outcome measures, we examined the effect of hTG2 expression on the onset and progression of the R6/2 behavioral phenotype. To avoid potential confounding behavioral traits attributable to gender differences only males were used for behavioral characterization. Mice of the different genotypes were aged and underwent serial behavioral evaluations at 50, 75, 100, and 125 days of age.

Rotarod performance is an indication of balance and motor coordination, and has been shown to decline with respect to age in R6/2 mice (Hockly et al., 2003; Perry et al., 2010). Motor performances of R6/2:WT; WT:hTG2; double transgenic R6/2:hTG2, and wild-type littermate were assessed using an accelerating rotarod (4-40 rpm) as described previously (Perry et al., 2010). At 50 days of age, there was a significant effect of the number of trials on rotarod performance of mice of the four genotypic groups, and all mice were able to remain on the rod for longer periods with successive trials suggesting that all mice were able to learn the task (Figure 3). There was no difference between double transgenic and R6/2 rotarod performance at any trial, while as expected there was a significant difference in rotarod performance between R6/2 mice and wild type mice over time (F(31,1864)=6.66, p<0.0001) and with respect to genotype (F(3,1864)=259.9, p<0.0001) (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Constitutive expression of hTG2 does not alter the rotarod performance of R6/2 mice.

Motor coordination was assessed with an accelerating rotarod (4 to 40 rpm), and rotarod tests were performed in two phases: training and testing. On the first day mice were subjected to three trials (trials 1 to 3) during this training phase mice were allowed to become accustomed to the rod. Subsequently and for the next five days, mice were tested with one trial per day (trials 4 to 8). (A) Times before fall from rotarod at accelerating speeds of WT:WT (n=19 to 22); WT:hTG2 (n=6 to 14); R6/2:WT (n=21 to 32), and R6/2:hTG2 (n=9 to 18) male mice were monitored at 50, 75, 100 and 125 days of age. Data are presented as mean ± SEM, WT:WT versus R6/2:WT, # p<0.05; WT:WT versus WT:hTG2, * p<0.05.

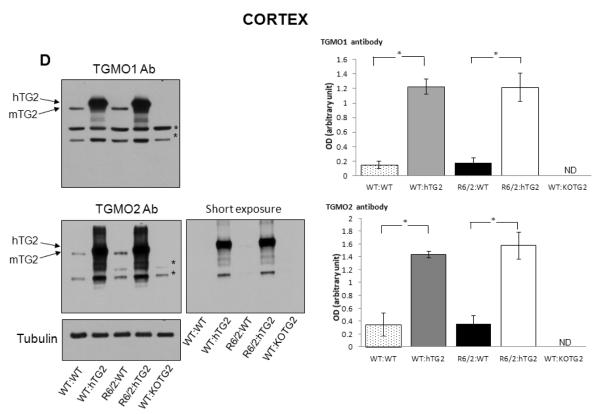

Next, we examined the effects of hTG2 expression on the muscular strength of R6/2 mice. Forelimb and hindlimb grip strengths were assessed at 50, 75, 100, and 125 days of age (Figure 4). Consistent with previous studies, the overall forelimb only and combined (forelimb + hindlimb) grip strength performances of the R6/2 mice were significantly lower than wild type mice (forelimb, F(1,187)=123.4, p<0.0001; combined, F(1,187)=237.4, p<0.0001), and worsened over time (forelimb, F(3,187)=45.1, p<0.0001; combined, F(3,187)=38.2, p<0.0001). The forelimb and combined grip strengths of WT:hTG2 mice and WT:WT mice were not significantly different (forelimb, F(1,131)=2.5, p=0.12; combined, F(1,131)=0.9, p=0.34) (Figure 4 A-B). Constitutive expression of hTG2 did not significantly alter the age-dependent weakening grip strengths of R6/2 mice, and at the different time points analyzed, double transgenic performed similarly when compared to the R6/2 mice (forelimb, F(1,133)=1.8, p=0.19; combined, F(1,133)=2.9, p=0.1) (Figure 4 A-B).

Figure 4. Constitutive expression of hTG2 does not alter the weakening grip strength of R6/2 mice.

Forelimb (A) and combined (forelimb + hindlimb) (B) muscular strengths of WT:WT (n=20 to 29), WT:hTG2 (n=7 to 14), R6/2:WT (n=20 to 31), and R6/2:hTG2 (n=7 to 15) mice at 50, 75, 100, and 125 days of age. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. WT:WT versus R6/2:WT, *p<0.05; WT:hTG2 versus R6/2:hTG2, # p<0.05.

R6/2 mice have a propensity to become inactive with age (Hockly et al., 2003; Mangiarini et al., 1996; Perry et al., 2010). Using a cage activity monitoring system we determined whether overexpression of hTG2 alters the progressive decline in the spontaneous locomotor and rhythms activities of the R6/2 mice. R6/2:WT, WT:hTG2, double transgenic R6/2:hTG2 and wild type littermate mice were individually acclimated for 3 days in activity monitoring micro isolator cages prior to continuously monitoring of horizontal and vertical beam breaks. Data is presented as the average of lower (horizontal activity) or upper (rearing) beams broken over a 24 hour period (Figure 5A-F). Consistent with previous studies it was found that the overall horizontal and rearing activities of R6/2 mice were significantly altered when compared to wild type mice (horizontal activity, F(1,130)=33.55, p<0.0001; rearing activity F(1,130)=29.3, p<0.0001) and both horizontal and rearing activities deteriorated in an age-dependent manner (horizontal activity F(3,130)=8.05, p<0.0001; rearing activity F(3,130)=5.22, p=0.002) (Figure 5A,D). Further analysis revealed that the altered horizontal activity of the R6/2 mice was essentially due to a deterioration of the nocturnal horizontal activity (nocturnal horizontal activity F(3,60)=24.8, p<0.0001; diurnal horizontal activity F(3,60)=1.53, p=0.22), while the overall decreased rearing activity of R6/2 mice resulted from both a significantly impaired nocturnal (F(3,60)=17.9, p<0.0001) and diurnal (F(3,60)=4.1, p=0.01) activities (Figure 5). Next, it was determined that at the different time points hTG2 expression has no significant effect on the spontaneous motor activity of wild type mice (horizontal F(1,95)=0.06, p=0.81 and rearing F(1,95)=0.40, p=0.53) (Figure 5A,D). Further, there was no overall effect of hTG2 on the spontaneous and rhythm activities of the R6/2 mice, as at all-time points examined R6/2:WT mice and R6/2:hTG2 mice presented similar horizontal (F(1,80)=2.7, p=0.1) and rearing (F(1,80)=0.001, p=0.98) activities (Figure 5A,D). In summary, constitutive expression of hTG2 did not affect the declining spontaneous horizontal and rearing activities of R6/2 mice.

Figure 5. Effects of hTG2 expression on spontaneous locomotor activities and activity rhythms of R6/2 mice.

Home cages activities of 50, 75, 100, and 125 days old WT:WT (n=17 to 25); WT:hTG2 (n=6 to 9); R6/2:WT (n=6 to 22) and R6/2:hTG2 (n=3 to 7) male mice was monitored over a 24 hours period following a 3 days acclimation period. Results are presented as an average of lower beams broken (horizontal activity; A-C) and upper beams broken (rearing activity; D-F) over a 24 hours light and dark period (A, D); a 12 hours light period (B, E); and a 12 hours dark period (C, F). Over time there was no significant effect of the hTG2 genotype on the progressive decline in horizontal activity and rearing activity of R6/2 mice. All data are presented as mean ± SEM. WT:WT versus R6/2:WT, *p<0.05; WT:hTG2 versus R6/2:hTG2, # p<0.05.

Constitutive expression of hTG2 does not modify the neuropathological phenotype of R6/2 mice

In secondary outcome measures the effect of hTG2 expression on the neuropathological features of R6/2 mice was examined. Unbiased stereological analysis of brains collected from 5 WT:WT (131.2 ± 1.1 days of age); 3 WT:hTG2 (126.3 ± 1.3 days of age); 5 R6/2:WT (129.8 ± 1.5 days of age); and 5 R6/2:hTG2 (128.6 ± 1.3 days of age) was performed to examine the effect of hTG2 overexpression on the striatal volume, neuronal number and htt aggregates of R6/2 mice. The volume of wild type mouse striatum was not significantly affected by the hTG2 genotype (WT:WT: 8.01± 0.2×109 μm3; WT:hTG2: 7.93±0.19×109 μm3; pairwise comparison p=0.791) (Figure 6C). The total number of NeuN positive neurons within the striatum was not significantly different between wild type mice and wild type mice constitutively expressing hTG2 (WT:WT: 5.93±0.38×105; WT:hTG2: 6.14±0.22×105; pairwise comparison, p=0.71) (Figure 6B). The striatal volume of R6/2 mice (R6/2:WT: 7.06±0.24×109 μm3) was significantly lower compared to wild type mice (pairwise comparison, p=0.016), with no significant difference in the number of striatal NeuN positive neurons between the two groups (R6/2:WT 5.35±0.4×105; pairwise comparison, p=0.33) (Figure 6B,C). There was no significant effect of the hTG2 genotype on the volume of the R6/2 mouse striatum (R6/2:hTG2 6.90±0.29×109 μm3; pairwise comparison p=0.98), and the total number of striatal NeuN positive neurons was not significantly different between R6/2:WT and R6/2:hTG2 mice (R6/2:hTG2 6.26±0.44×105; pairwise comparison p=0.17) (Figure 6B,C). Thus, there was no significant effect of hTG2 overexpression on the striatal volume and neuronal number of R6/2 mice.

Figure 6. Effects of hTG2 expression on the neuropathological phenotype of R6/2 mice.

(A) Representative photomicrographs of NeuN immunostaining within the striatum of WT:WT; WT:hTG2; R6/2:WT and R6/2:hTG2 mice. Scale bar equals 100 μm. Unbiased stereology analysis examining (B) the total number of striatal NeuN positive stained cells and (C) striatal volume of 18 to19 weeks old WT:WT (n=5); WT:hTG2 (n=3); R6/2:WT (n=5) and R6/2:hTG2 (n=5) mice. There was no significant different on the total number of NeuN positive neurons (P=0.17) and the striatal volume (P=0.98) between R6/2:WT and R6/2:hTG2 mice.

Next, coronal sections of whole brain were immunostained for huntingtin immunoreactivity in order to quantitatively examine the density of huntingtin protein aggregates within the striatum of R6/2:WT and R6/2:hTG2 mouse brains. Representative photomicrographs showing the presence of huntingtin aggregates in the striatum of R6/2:WT and R6/2:hTG2 mice are presented in figure 7A. Huntingtin immunoreactive aggregates were observed throughout the striatum of R6/2 mice, and as expected were not detected in WT:WT and WT:hTG2 mouse brains (figure 7A). Quantitative analysis of htt aggregates (diameter>0.5μm) revealed no significant difference in the number of striatal NIIs and cytoplasmic htt aggregates between R6/2:WT (223.5±16 aggregates/μm3; n=5) and R6/2:hTG2 (200.9±27 aggregates/μm3; n=5) mice (pairwise comparison p=0.59), and no obvious difference in the striatal distribution of htt aggregates between the two groups (Figure 7B).

Figure 7. Effects of hTG2 expression on huntingtin protein aggregates.

(A) Representative photomicrographs of huntingtin protein immunostaining within the striatum of WT:WT, WT:hTG2, R6/2:WT and R6/2:hTG2 mice. Scale bar equals 10 μm. (B) Unbiased stereology analysis examining the number and density of huntingtin aggregates within the striatum of R6/2:WT (n=5) and R6/2:hTG2 (n=5) mice. The hTG2 genotype did not significantly affect the density of htt aggregates in the striatum of R6/2 mice (P=0.59). Data are presented as mean ± SEM.

Discussion

Previous studies have shown that huntingtin is an in vitro substrate of TG2, and overexpression of TG2 in cell-based models of HD modulates the polyglutamine-mediated toxicity and the formation of huntingtin aggregates (Cooper et al., 1997; Kahlem et al., 1998a; Kahlem et al., 1998b; Kahlem et al., 1996; Lesort et al., 2000a). Further, TG2 levels and activity are significantly increased in the brains of HD patients (Lesort et al., 1999). Thus, we assessed whether the constitutive expression of hTG2 would affect the well-characterized motor phenotype and neuropathological changes associated with the R6/2 HD mouse model (Hockly et al., 2003; Mangiarini et al., 1996; Perry et al., 2010). Indeed, if TG2 is a significant modifier of the disease we would predict that increasing TG2 levels in R6/2 mouse brains could significantly modulate the phenotype and disease progression of this HD mouse model. Constitutive expression of hTG2 in approximately 8-to 10-fold of the endogenous TG2 levels failed to significantly affect the behavioral and neurological features of R6/2 mice. A robust increase in hTG2 did not significantly influence the body weight decrease, declining rotarod performance, declining grip strength, or reduced overall activity of R6/2 mice. In addition, increasing TG2 did not have any effect on the neuropathological features examined, as we found no significant difference in striatal volumes, neuronal counts, or striatal aggregate densities between R6/2:WT and R6/2:hTG2 mice. Altogether, we provide evidence that an increase in TG2 in HD brain does not significantly modify the disease onset and progression of the R6/2 mice.

Supporting the hypothesis that increasing in the number of glutamine residues may result in a protein becoming a TG substrate, proteins with expanded polyglutamine stretches are cross-linked by TG2 in vitro and increasing the length of the polyglutamine stretches increases their ability to be modified by TG2 (Cooper et al., 1997; Kahlem et al., 1998a; Kahlem et al., 1998b; Kahlem et al., 1996; Lesort et al., 2000a). These initial observations and the identification of huntingtin inclusions in HD brains have led to the hypothesis that TG2 may promote HD pathogenesis by facilitating the formation of these aggregates. However, subsequent studies provided evidence that TG2 was dispensable for the formation of polyglutamine aggregates (Chun et al., 2001), and in fact there is evidence to suggest that TG2 negatively regulates the formation of huntingtin aggregates (Bailey and Johnson, 2005; Lai et al., 2004). In support of these findings, we provide evidence that the density and distribution of huntingtin aggregates in R6/2 mouse brains is not significantly affected by a robust increase in hTG2 level. Thus, altogether these results indicate that TG2 does not facilitate the formation of insoluble huntingtin aggregates.

In this study we report that hTG2 did not significantly affect the HD phenotype when overexpressed in R6/2 mice; however, we know from previous studies that brain hTG2 is capable of functional activity against various acute insults. For instance the hTG2 mice used in the present study have been shown to be more susceptible to the kainate-induced seizure and hippocampal neuronal cell death when compared to wild-type mice (Tucholski et al., 2006). Thus, TG2 plays an active role in excitatory amino acid-induced neuronal cell death (Tucholski et al., 2006). In contrast, exogenous expression of hTG2 in mouse neurons resulted in significantly smaller infarct volumes after middle cerebral artery ligation, suggesting that hTG2 was protective (Filiano et al., 2010). Interestingly, our data reveals that a robust expression of hTG2 does not significantly affect the HD phenotype, indicating that the effects of hTG2 on cell death processes are determined by context and in the case of HD the stress-induced by the chronic expression of mutant huntingtin protein results either in compensatory mechanisms that provide tolerance against hTG2 activation or fails to activate hTG2. As indicated above, previously TG2 is a highly regulated enzyme that catalyzes the calcium-dependent peptide crosslinking, deamination, or polyamination reactions at glutamate residues within specific protein substrates (Lesort et al., 2000a). In addition to these calcium-dependent functions, TG2 possesses the ability to bind and hydrolyze GTP and significantly the binding of GTP to TG2 inhibits the transamidating activity of the enzyme (Zhang et al., 1998). Thus, under physiological conditions with relatively low levels of calcium and high GTP concentration, the transamidating activity of TG2 is kept very low within neurons. Indeed, this tight regulation of the enzyme activity would explain why the mouse can tolerate the long term exogenous expression of hTG2 and the normalcy of hTG2 mice as no overt spontaneous phenotype was detected in hTG2 mice. (Tucholski et al., 2006) However, in conditions that are favorable for an activation of TG2 such as an increase in intracellular calcium concentration and a decrease in GTP level the transamidating activity of the enzyme is no longer inhibited and therefore TG2 can modify protein substrates (Tucholski et al., 2006). Though an increase in transglutaminase activity has been reported in the cortex and striatum of postmortem HD brains when compared to controls, in this study transglutaminase activity was measured in vitro and in the presence of high calcium concentration, and thus may not reflect the actual level of the enzyme activity in vivo considering that brain TG2 activity is tightly regulated (Lesort et al., 1999). However, a more compelling argument for an increased transglutaminase activity in HD results from the several fold increased in the transglutaminase-mediated products Nε-(γ-glutamyl)-l-lysine and γ-glutamylamines in HD brains and in the CSF from HD patients when compared to control individuals (Jeitner et al., 2012; Jeitner et al., 2001; Jeitner et al., 2008). These findings provide indirect evidence to suggest that TGs are activated in HD brains, and indeed conditions favoring the activity of the enzyme are enhanced in HD brains. These conditions include a decreased GTP concentration linked to mitochondrial dysfunction, a deregulation of the cellular calcium homeostasis due to enhanced NMDA receptor activation, enhanced IP3 receptor activity and impaired mitochondrial calcium buffering capacity (Bezprozvanny and Hayden, 2004; Cepeda et al., 2001; Fan and Raymond, 2007; Perry et al., 2010; Perry et al., 1982). In contrast to human HD brains, a significant decrease in Nε-(γ-glutamyl)-l-lysine was detected in R6/2 mouse brains when compared to wild type mice, a difference that may result from the degree of sequestered protein bound in insoluble mutant huntingtin aggregates, as Nε-(γ-glutamyl)-l-lysine isopeptide bond histologic immunoreactivity was markedly increased in R6/2 mouse brains (Dedeoglu et al., 2002).

To further evaluate the contribution of TG2 in the progression of HD, several studies have assessed the possibility that TG inhibition may be a beneficial pharmacological intervention as part of a therapeutic strategy for the treatment of HD. For instance, treatment with cystamine, which is rapidly reduced in vivo to cysteamine, a competitive inhibitor of TG2 (Jeitner et al., 2005), is beneficial to the R6/2 and YAC128 mouse model of HD (Bailey and Johnson, 2006; Karpuj et al., 2002; Van Raamsdonk et al., 2005). However, it is unclear to what extent the therapeutic benefits of cystamine can be attributed to TG2 inhibition, as beneficial effects of cystamine were detected in HD mice that are knockout for TG2 (Bailey and Johnson, 2006), cystamine inhibits caspase and increases the levels of glutathione (Lesort et al., 2003). Further, using HPLC with coulometric detection neither cystamine nor cysteamine can be detected in the brains of cystamine-treated HD mice (Pinto et al., 2005), while only minute amounts of cysteamine can be detected using HPLC coupled to fluorescence detection (Bousquet et al., 2010). Indeed, a more compelling argument for a role of TG2 in HD disease has emerged from studies exploiting TG2 knock-out mice to show that a complete knock out of TG2 in R6/1 and R6/2 mouse models of HD, delayed the onset of motor dysfunction and prolonged survival (Bailey and Johnson, 2005; Mastroberardino et al., 2002). These results suggest that TG2 may actually modify some aspects of the R6/2 HD phenotype and to a certain extent are in contrast with our findings, as we find no effect of a robust increase in TG2 expression on the motor phenotypes and survival of R6/2 mice. However, a possibility is that the endogenous level of TG2 is sufficient to confer the maximal effect of TG2 in HD brains and that providing more had no additional effect. Supporting this view, knocking out TG2 in the R6/2 mouse model resulted in an increased number of aggregates compared to controls R6/2 mice (Bailey and Johnson, 2005), whereas in the present study a robust increase in hTG2 did not significantly affect the number of striatal NIIs and cytoplasmic htt aggregates. Our findings that a large exogenous expression of hTG2 did not affect the phenotype of R6/2 mice would suggest that HD mouse brains can support or adapt to a chronic elevation and activation of TG2, or alternatively that the conditions are not optimal for TG2 to be activated in R6/2 mouse brains.

Research highlights.

-

➢

Mouse line expressing human TG2 (hTG2) does not present any spontaneous phenotype.

-

➢

Constitutive expression of hTG2 in the brains of HD mice does not result in discernible change in progression of the disease phenotype and behavioral deficits in R6/2 mice.

-

➢

Constitutive expression of hTG2 does not affect the neuropathological phenotype of R6/2 mice.

-

➢

Overexpression of hTG2 did not significantly modulate the number of striatal huntingtin inclusions.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Gail V. W. Johnson (Rochester University) for generously providing the transglutaminase antibodies, for helpful discussion and reviewing an initial version of this manuscript. We would like to thank Dr. Gillian Bates, Dr. David Howland and Dr. Douglas Macdonald for facilitating this study and helpful discussions. Appreciation is expressed to Dr. Buffie Clodfelder-Miller and members of Lesort laboratory for expert technical assistance. This work was partially supported by the National Institute of Health [NS071168 to M.L., NS062216 to P.D.]; and the UAB Neuroscience Core Facilities [PO3 NS47466, NS 57098].

Abbreviations

- HD

Huntington’s disease

- htt

huntingtin

- polyQ

polyglutamine

- TG2

tissue transglutaminase

- WT

wild type

- MSN

medium spiny neuron

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest statement: None to declare.

References

- Bailey CD, Johnson GV. Tissue transglutaminase contributes to disease progression in the R6/2 Huntington’s disease mouse model via aggregate-independent mechanisms. J Neurochem. 2005;92:83–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02839.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey CD, Johnson GV. The protective effects of cystamine in the R6/2 Huntington’s disease mouse involve mechanisms other than the inhibition of tissue transglutaminase. Neurobiol Aging. 2006;27:871–879. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beal MF. Huntington’s disease, energy, and excitotoxicity. Neurobiol Aging. 1994;15:275–276. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(94)90132-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beal MF. Mitochondria, free radicals, and neurodegeneration. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1996;6:661–666. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(96)80100-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezprozvanny I, Hayden MR. Deranged neuronal calcium signaling and Huntington disease. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2004;322:1310–1317. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bousquet M, Gibrat C, Ouellet M, Rouillard C, Calon F, Cicchetti F. Cystamine metabolism and brain transport properties: clinical implications for neurodegenerative diseases. J Neurochem. 2010;114:1651–1658. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06874.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cepeda C, Ariano MA, Calvert CR, Flores-Hernandez J, Chandler SH, Leavitt BR, Hayden MR, Levine MS. NMDA receptor function in mouse models of Huntington disease. Journal of neuroscience research. 2001;66:525–539. doi: 10.1002/jnr.1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choo YS, Johnson GV, MacDonald M, Detloff PJ, Lesort M. Mutant huntingtin directly increases susceptibility of mitochondria to the calcium-induced permeability transition and cytochrome c release. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13:1407–1420. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chun W, Lesort M, Tucholski J, Ross CA, Johnson GV. Tissue transglutaminase does not contribute to the formation of mutant huntingtin aggregates. J Cell Biol. 2001;153:25–34. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.1.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper AJ, Sheu KF, Burke JR, Onodera O, Strittmatter WJ, Roses AD, Blass JP. Polyglutamine domains are substrates of tissue transglutaminase: does transglutaminase play a role in expanded CAG/poly-Q neurodegenerative diseases? J Neurochem. 1997;69:431–434. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.69010431.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies SW, Turmaine M, Cozens BA, DiFiglia M, Sharp AH, Ross CA, Scherzinger E, Wanker EE, Mangiarini L, Bates GP. Formation of neuronal intranuclear inclusions underlies the neurological dysfunction in mice transgenic for the HD mutation. Cell. 1997;90:537–548. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80513-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dedeoglu A, Kubilus JK, Jeitner TM, Matson SA, Bogdanov M, Kowall NW, Matson WR, Cooper AJ, Ratan RR, Beal MF, Hersch SM, Ferrante RJ. Therapeutic effects of cystamine in a murine model of Huntington’s disease. J Neurosci. 2002;22:8942–8950. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-20-08942.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiFiglia M, Sapp E, Chase K, Schwarz C, Meloni A, Young C, Martin E, Vonsattel JP, Carraway R, Reeves SA, et al. Huntingtin is a cytoplasmic protein associated with vesicles in human and rat brain neurons. Neuron. 1995;14:1075–1081. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90346-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiFiglia M, Sapp E, Chase KO, Davies SW, Bates GP, Vonsattel JP, Aronin N. Aggregation of huntingtin in neuronal intranuclear inclusions and dystrophic neurites in brain. Science. 1997;277:1990–1993. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5334.1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan MM, Raymond LA. N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor function and excitotoxicity in Huntington’s disease. Prog Neurobiol. 2007;81:272–293. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2006.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrante RJ, Andreassen OA, Jenkins BG, Dedeoglu A, Kuemmerle S, Kubilus JK, Kaddurah-Daouk R, Hersch SM, Beal MF. Neuroprotective effects of creatine in a transgenic mouse model of Huntington’s disease. J Neurosci. 2000;20:4389–4397. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-12-04389.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filiano AJ, Bailey CD, Tucholski J, Gundemir S, Johnson GV. Transglutaminase 2 protects against ischemic insult, interacts with HIF1beta, and attenuates HIF1 signaling. Faseb J. 2008;22:2662–2675. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-097709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filiano AJ, Tucholski J, Dolan PJ, Colak G, Johnson GV. Transglutaminase 2 protects against ischemic stroke. Neurobiol Dis. 2010;39:334–343. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2010.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischbeck KH. Polyglutamine expansion neurodegenerative disease. Brain research bulletin. 2001;56:161–163. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(01)00577-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentile V, Sepe C, Calvani M, Melone MA, Cotrufo R, Cooper AJ, Blass JP, Peluso G. Tissue transglutaminase-catalyzed formation of high-molecular-weight aggregates in vitro is favored with long polyglutamine domains: a possible mechanism contributing to CAG-triplet diseases. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1998;352:314–321. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1998.0592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green H. Human genetic diseases due to codon reiteration: relationship to an evolutionary mechanism. Cell. 1993;74:955–956. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90718-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg CS, Birckbichler PJ, Rice RH. Transglutaminases: multifunctional cross-linking enzymes that stabilize tissues. Faseb J. 1991;5:3071–3077. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.5.15.1683845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu M, Gash MT, Mann VM, Javoy-Agid F, Cooper JM, Schapira AH. Mitochondrial defect in Huntington’s disease caudate nucleus. Ann Neurol. 1996;39:385–389. doi: 10.1002/ana.410390317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hockly E, Woodman B, Mahal A, Lewis CM, Bates G. Standardization and statistical approaches to therapeutic trials in the R6/2 mouse. Brain research bulletin. 2003;61:469–479. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(03)00185-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iismaa SE, Mearns BM, Lorand L, Graham RM. Transglutaminases and disease: lessons from genetically engineered mouse models and inherited disorders. Physiological reviews. 2009;89:991–1023. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00044.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeitner TM, Battaile K, Cooper AJ. gamma-Glutamylamines and neurodegenerative diseases. Amino acids. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s00726-011-1209-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeitner TM, Bogdanov MB, Matson WR, Daikhin Y, Yudkoff M, Folk JE, Steinman L, Browne SE, Beal MF, Blass JP, Cooper AJ. N(epsilon)-(gamma-L-glutamyl)-l-lysine (GGEL) is increased in cerebrospinal fluid of patients with Huntington’s disease. J Neurochem. 2001;79:1109–1112. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00673.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeitner TM, Delikatny EJ, Ahlqvist J, Capper H, Cooper AJ. Mechanism for the inhibition of transglutaminase 2 by cystamine. Biochem Pharmacol. 2005;69:961–970. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2004.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeitner TM, Matson WR, Folk JE, Blass JP, Cooper AJ. Increased levels of gamma-glutamylamines in Huntington disease CSF. J Neurochem. 2008;106:37–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05350.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahlem P, Green H, Djian P. Transglutaminase action imitates Huntington’s disease: selective polymerization of Huntingtin containing expanded polyglutamine. Mol Cell. 1998a;1:595–601. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80059-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahlem P, Green H, Djian P. Transglutaminase as the agent of neurodegenerative diseases due to polyglutamine expansion. Pathol Biol (Paris) 1998b;46:681–682. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahlem P, Terre C, Green H, Djian P. Peptides containing glutamine repeats as substrates for transglutaminase-catalyzed cross-linking: relevance to diseases of the nervous system. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:14580–14585. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.25.14580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karpuj MV, Becher MW, Springer JE, Chabas D, Youssef S, Pedotti R, Mitchell D, Steinman L. Prolonged survival and decreased abnormal movements in transgenic model of Huntington disease, with administration of the transglutaminase inhibitor cystamine. Nat Med. 2002;8:143–149. doi: 10.1038/nm0202-143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kegel KB, Kim M, Sapp E, McIntyre C, Castano JG, Aronin N, DiFiglia M. Huntingtin expression stimulates endosomal-lysosomal activity, endosome tubulation, and autophagy. J Neurosci. 2000;20:7268–7278. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-19-07268.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SY, Marekov L, Bubber P, Browne SE, Stavrovskaya I, Lee J, Steinert PM, Blass JP, Beal MF, Gibson GE, Cooper AJ. Mitochondrial aconitase is a transglutaminase 2 substrate: transglutamination is a probable mechanism contributing to high-molecular-weight aggregates of aconitase and loss of aconitase activity in Huntington disease brain. Neurochemical research. 2005;30:1245–1255. doi: 10.1007/s11064-005-8796-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai TS, Tucker T, Burke JR, Strittmatter WJ, Greenberg CS. Effect of tissue transglutaminase on the solubility of proteins containing expanded polyglutamine repeats. J Neurochem. 2004;88:1253–1260. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.02249.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesort M, Chun W, Johnson GV, Ferrante RJ. Tissue transglutaminase is increased in Huntington’s disease brain. J Neurochem. 1999;73:2018–2027. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesort M, Lee M, Tucholski J, Johnson GV. Cystamine inhibits caspase activity. Implications for the treatment of polyglutamine disorders. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:3825–3830. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205812200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesort M, Tucholski J, Miller ML, Johnson GV. Tissue transglutaminase: a possible role in neurodegenerative diseases. Prog Neurobiol. 2000a;61:439–463. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(99)00052-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesort M, Tucholski J, Zhang J, Johnson GV. Impaired mitochondrial function results in increased tissue transglutaminase activity in situ. J Neurochem. 2000b;75:1951–1961. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0751951.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorand L, Conrad SM. Transglutaminases. Molecular and cellular biochemistry. 1984;58:9–35. doi: 10.1007/BF00240602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorand L, Graham RM. Transglutaminases: crosslinking enzymes with pleiotropic functions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:140–156. doi: 10.1038/nrm1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthi-Carter R, Hanson SA, Strand AD, Bergstrom DA, Chun W, Peters NL, Woods AM, Chan EY, Kooperberg C, Krainc D, Young AB, Tapscott SJ, Olson JM. Dysregulation of gene expression in the R6/2 model of polyglutamine disease: parallel changes in muscle and brain. Hum Mol Genet. 2002a;11:1911–1926. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.17.1911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthi-Carter R, Strand A, Peters NL, Solano SM, Hollingsworth ZR, Menon AS, Frey AS, Spektor BS, Penney EB, Schilling G, Ross CA, Borchelt DR, Tapscott SJ, Young AB, Cha JH, Olson JM. Decreased expression of striatal signaling genes in a mouse model of Huntington’s disease. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9:1259–1271. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.9.1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthi-Carter R, Strand AD, Hanson SA, Kooperberg C, Schilling G, La Spada AR, Merry DE, Young AB, Ross CA, Borchelt DR, Olson JM. Polyglutamine and transcription: gene expression changes shared by DRPLA and Huntington’s disease mouse models reveal context-independent effects. Hum Mol Genet. 2002b;11:1927–1937. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.17.1927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangiarini L, Sathasivam K, Seller M, Cozens B, Harper A, Hetherington C, Lawton M, Trottier Y, Lehrach H, Davies SW, Bates GP. Exon 1 of the HD gene with an expanded CAG repeat is sufficient to cause a progressive neurological phenotype in transgenic mice. Cell. 1996;87:493–506. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81369-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marder K, Zhao H, Eberly S, Tanner CM, Oakes D, Shoulson I, Huntington G. Dietary intake in adults at risk for Huntington disease: analysis of PHAROS research participants. Neurology. 2009;73:385–392. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181b04aa2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mastroberardino PG, Iannicola C, Nardacci R, Bernassola F, De Laurenzi V, Melino G, Moreno S, Pavone F, Oliverio S, Fesus L, Piacentini M. Tissue’ transglutaminase ablation reduces neuronal death and prolongs survival in a mouse model of Huntington’s disease. Cell Death Differ. 2002;9:873–880. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McConoughey SJ, Basso M, Niatsetskaya ZV, Sleiman SF, Smirnova NA, Langley BC, Mahishi L, Cooper AJ, Antonyak MA, Cerione RA, Li B, Starkov A, Chaturvedi RK, Beal MF, Coppola G, Geschwind DH, Ryu H, Xia L, Iismaa SE, Pallos J, Pasternack R, Hils M, Fan J, Raymond LA, Marsh JL, Thompson LM, Ratan RR. Inhibition of transglutaminase 2 mitigates transcriptional dysregulation in models of Huntington disease. EMBO molecular medicine. 2010;2:349–370. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201000084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morton AJ, Glynn D, Leavens W, Zheng Z, Faull RL, Skepper JN, Wight JM. Paradoxical delay in the onset of disease caused by super-long CAG repeat expansions in R6/2 mice. Neurobiol Dis. 2009;33:331–341. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2008.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson MS, Williford HN, Blessing DL, Wilson GD, Halpin G. A test to estimate VO2max in females using aerobic dance, heart rate, BMI, and age. The Journal of sports medicine and physical fitness. 1995;35:159–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panov A, Obertone T, Bennett-Desmelik J, Greenamyre JT. Ca(2+)-dependent permeability transition and complex I activity in lymphoblast mitochondria from normal individuals and patients with Huntington’s or Alzheimer’s disease. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1999;893:365–368. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb07856.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry GM, Tallaksen-Greene S, Kumar A, Heng MY, Kneynsberg A, van Groen T, Detloff PJ, Albin RL, Lesort M. Mitochondrial calcium uptake capacity as a therapeutic target in the R6/2 mouse model of Huntington’s disease. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19:3354–3371. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry TL, Wright JM, Hansen S, Thomas SM, Allan BM, Baird PA, Diewold PA. A double-blind clinical trial of isoniazid in Huntington disease. Neurology. 1982;32:354–358. doi: 10.1212/wnl.32.4.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto JT, Van Raamsdonk JM, Leavitt BR, Hayden MR, Jeitner TM, Thaler HT, Krasnikov BF, Cooper AJ. Treatment of YAC128 mice and their wild-type littermates with cystamine does not lead to its accumulation in plasma or brain: implications for the treatment of Huntington disease. J Neurochem. 2005;94:1087–1101. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03255.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roos RA. Huntington’s disease: a clinical review. Orphanet journal of rare diseases. 2010;5:40. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-5-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosas HD, Feigin AS, Hersch SM. Using advances in neuroimaging to detect, understand, and monitor disease progression in Huntington’s disease. NeuroRx: the journal of the American Society for Experimental NeuroTherapeutics. 2004;1:263–272. doi: 10.1602/neurorx.1.2.263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosas HD, Koroshetz WJ, Chen YI, Skeuse C, Vangel M, Cudkowicz ME, Caplan K, Marek K, Seidman LJ, Makris N, Jenkins BG, Goldstein JM. Evidence for more widespread cerebral pathology in early HD: an MRI-based morphometric analysis. Neurology. 2003;60:1615–1620. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000065888.88988.6e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosas HD, Lee SY, Bender AC, Zaleta AK, Vangel M, Yu P, Fischl B, Pappu V, Onorato C, Cha JH, Salat DH, Hersch SM. Altered white matter microstructure in the corpus callosum in Huntington’s disease: implications for cortical “disconnection. NeuroImage. 2010;49:2995–3004. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosas HD, Liu AK, Hersch S, Glessner M, Ferrante RJ, Salat DH, van der Kouwe A, Jenkins BG, Dale AM, Fischl B. Regional and progressive thinning of the cortical ribbon in Huntington’s disease. Neurology. 2002;58:695–701. doi: 10.1212/wnl.58.5.695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossin F, D’Eletto M, Macdonald D, Farrace MG, Piacentini M. TG2 transamidating activity acts as a reostat controlling the interplay between apoptosis and autophagy. Amino acids. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s00726-011-0899-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tallaksen-Greene SJ, Janiszewska A, Benton K, Ruprecht L, Albin RL. Lack of efficacy of NMDA receptor-NR2B selective antagonists in the R6/2 model of Huntington disease. Experimental neurology. 2010;225:402–407. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2010.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Huntington’s Disease Collaborative Research Group. The Huntington’s Disease Collaborative Research Group A novel gene containing a trinucleotide repeat that is expanded and unstable on Huntington’s disease chromosomes. Cell. 1993;72:971–983. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90585-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trushina E, Dyer RB, Badger JD, 2nd, Ure D, Eide L, Tran DD, Vrieze BT, Legendre-Guillemin V, McPherson PS, Mandavilli BS, Van Houten B, Zeitlin S, McNiven M, Aebersold R, Hayden M, Parisi JE, Seeberg E, Dragatsis I, Doyle K, Bender A, Chacko C, McMurray CT. Mutant huntingtin impairs axonal trafficking in mammalian neurons in vivo and in vitro. Molecular and cellular biology. 2004;24:8195–8209. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.18.8195-8209.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucholski J, Roth KA, Johnson GV. Tissue transglutaminase overexpression in the brain potentiates calcium-induced hippocampal damage. J Neurochem. 2006;97:582–594. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03780.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Raamsdonk JM, Pearson J, Bailey CD, Rogers DA, Johnson GV, Hayden MR, Leavitt BR. Cystamine treatment is neuroprotective in the YAC128 mouse model of Huntington disease. J Neurochem. 2005;95:210–220. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vonsattel JP, Myers RH, Stevens TJ, Ferrante RJ, Bird ED, Richardson EP., Jr. Neuropathological classification of Huntington’s disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1985;44:559–577. doi: 10.1097/00005072-198511000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young AB, Greenamyre JT, Hollingsworth Z, Albin R, D’Amato C, Shoulson I, Penney JB. NMDA receptor losses in putamen from patients with Huntington’s disease. Science. 1988;241:981–983. doi: 10.1126/science.2841762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Lesort M, Guttmann RP, Johnson GV. Modulation of the in situ activity of tissue transglutaminase by calcium and GTP. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:2288–2295. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.4.2288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Tucholski J, Lesort M, Jope RS, Johnson GV. Novel bimodal effects of the G-protein tissue transglutaminase on adrenoreceptor signalling. The Biochemical journal. 1999;343(Pt 3):541–549. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]