Implicated in many neuropathologies, TDP-43 autoregulates its expression via a negative feedback loop. Baralle and colleagues now elucidate the interesting mechanism underlying this autoregulation. TDP-43 binding to its pre-mRNA 3′ UTR blocks recognition of the main pA site and also causes Pol II pausing downstream from its binding site, leading to excision of the main pA site via splicing of a 3′ UTR intron. This dual attack rapidly reduces levels of correctly processed TDP-43 mRNA.

Keywords: ALS, FTD, TDP-43, autoregulation, mRNA splicing, polyadenylation

Abstract

TDP-43 is a critical RNA-binding factor associated with pre-mRNA splicing in mammals. Its expression is tightly autoregulated, with loss of this regulation implicated in human neuropathology. We demonstrate that TDP-43 overexpression in humans and mice activates a 3′ untranslated region (UTR) intron, resulting in excision of the proximal polyA site (PAS) pA1. This activates a cryptic PAS that prevents TDP-43 expression through a nuclear retention mechanism. Superimposed on this process, overexpression of TDP-43 blocks recognition of pA1 by competing with CstF-64 for PAS binding. Overall, we uncover complex interplay between transcription, splicing, and 3′ end processing to effect autoregulation of TDP-43.

Genes that encode RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) such as PTB, hnRNP L, and SRSF1 are autoregulated to maintain a constant level of mRNA (Buratti and Baralle 2011). This autoregulatory process may be achieved in part by selective alternative splicing events that trigger nonsense-mediated decay (NMD)-mediated RNA degradation (Lejeune and Maquat 2005). The general term RUST (regulated unproductive splicing and translation) has been proposed to describe this category of gene regulation (Lareau et al. 2007a).

However, recently, several studies have highlighted the presence of ultraconserved sequences within selected introns of genes encoding many hnRNP family members. These conserved sequences point to additional autoregulatory mechanisms (Lareau et al. 2007b; Ni et al. 2007; Saltzman et al. 2008). Previously, we reported that the nuclear hnRNP protein TDP-43 maintains its protein levels by binding to and regulating the levels of its own mRNA (Ayala et al. 2011). In particular, we identified a TDP-43-binding region (TDPBR) (Fig. 1A) in the highly conserved 3′ untranslated region (UTR) of TDP-43 mRNA and showed that this element is critical for TDP-43 proteostasis. Steady-state analysis of TDP-43 mRNA showed that two different mRNAs of 4.2 kb and 2.8 kb are present in the cell in a ratio of ∼1:3 (Ayala et al. 2011). These mRNA isoforms differ in the length of their 3′ UTR, with the 2.8-kb mRNA using a proximal polyA site (PAS; pA1) and 4.2-kb mRNA using a distal PAS (pA4). Other putative PAS usage was not detected (Fig. 1A). A minor variant TDP-43 1.9-kb mRNA was also observed (V2 in Ayala et al. 2011; isoform 3 in Polymenidou et al. 2011). This mRNA is formed by two alternative splicing events in the 3′ UTR that remove both the TDP-43 stop codon and the pA1 PAS. Even though this variant mRNA undergoes NMD, it is not involved in TDP-43 autoregulation (Ayala et al. 2011) in spite of contrary suggestions (Polymenidou et al. 2011). In particular, V2 mRNA levels do not change following TDP-43 overexpression and hence cannot play a significant role in TDP-43 autoregulation. Furthermore, suppression of NMD by translation inhibition (cycloheximide [CHX] treatment) or Upf1 mRNA knockdown failed to increase V2 mRNA amounts to levels detectable by Northern blot analysis (Ayala et al. 2011). Although a possible role for V2 mRNA in TDP-43 autoregulation in other conditions/tissues is not ruled out, this study presents a distinct and unanticipated molecular mechanism for TDP-43 autoregulation. This involves complex interplay between transcription elongation, splicing, and 3′ end cleavage and polyadenylation.

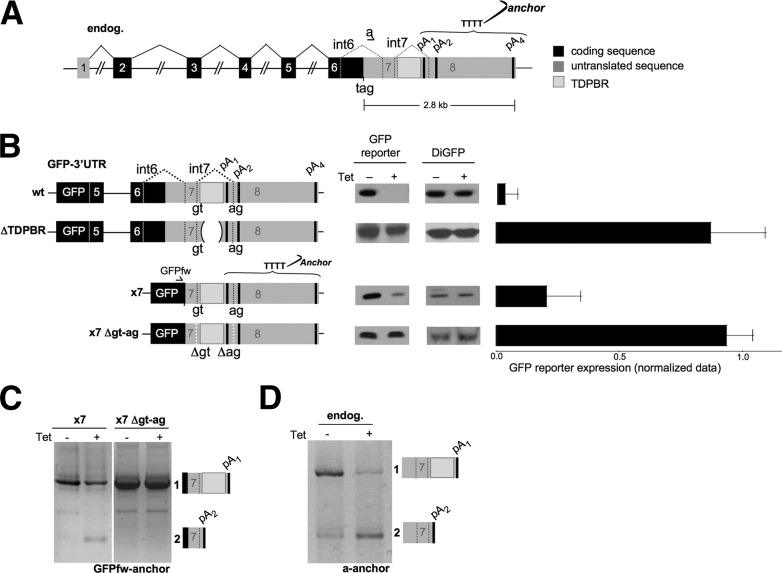

Figure 1.

Cis-acting elements and molecular events in TDP-43 autoregulation. (A) Schematic diagram of TDP-43 illustrating locations of the stop codon (tag), PASs (pA1–4), the TDPBR, and splicing events (in coding sequences, filled lines; in 3′ UTR, dotted lines). Coding regions (black boxes), untranslated sequences (gray boxes), and introns (connecting black lines) are indicated. RT–PCR primers are indicated. (B, left) Schematic representation of the GFP-3′UTR reporters are shown. (Middle) Western blots of GFP reporter protein in normal (−Tet) and TDP-43 overexpression conditions (+Tet) are shown. (Right) The bar chart shows densitometric quantification of protein expression, normalized against DiGFP expression. Mean values are plotted; error bars indicate the SD from at least three independent experiments. (C) 3′ RACE analysis (−Tet and +Tet) for x7 (left) and x7 Δgt-ag (right) reporters using the specific GFPfw and anchor primers (see A). (Right) The schematic representation denotes amplified mRNA isoforms (bands 1 and 2) confirmed by sequence analysis. (D) 3′ RACE analysis of endogenous TDP-43 (−Tet and +Tet). The forward primer annealed to intron 6 (a), while the anchor was used as the reverse primer (see A). (Right) Amplified mRNA isoforms are indicated.

Results and Discussion

Cis-acting elements and molecular events in TDP-43 autoregulation

To identify essential RNA sequences involved in TDP-43 autoregulation, we used a previously described hybrid construct containing a GFP reporter gene fused to the 3′ region of TDP-43 (GFP-3′UTR), shown to reproduce the autoregulation observed for endogenous TDP-43. Mutations were engineered into the TDP-43 3′ UTR in this construct, and the resulting constructs were transfected into HEK-293 cells also carrying an integrated tetracycline-inducible TDP-43 cDNA (Fig. 1B; Ayala et al. 2011).

We initially confirmed the importance of the previously identified 3′ UTR TDPBR. The construct GFP-3′UTR ΔTDPBR carries a 615-nucleotide (nt) deletion that removes the entire TDPBR, leaving only short intron 7 segments that retain the 5′ and 3′ splice sites. Comparison of the protein expression of the wild-type GFP-3′UTR construct with GFP-3′UTR ΔTDPBR confirmed the importance of TDPBR for autoregulation. Thus, no GFP down-regulation occurs with the ΔTDPBR transgene following tetracycline induction of TDP-43 expression (Fig. 1B). In these experiments, GFP protein production was normalized by cotransfection with a plasmid expressing DiGFP (Fig. 1B, DiGFP lanes). A series of further deletions (data not shown) revealed that the minimal sequences needed to preserve TDP-43 autoregulation were retained in the construct named x7 (Fig. 1B), which contains only the TDP-43 3′ UTR sequence including intron 7 and the intronic pA1. Interestingly, point mutation of intron 7 5′ and 3′ splice sites in x7 causes a loss of TDP-43 autoregulation (see below).

TDP-43 autoregulation of wild-type GFP-3′UTR has previously been investigated by Northern blot analysis. However, no new mRNA species were detected following TDP-43 overexpression (Ayala et al. 2011). Suspecting that increased TDP-43 cellular levels may result in the generation of unstable TDP-43 transcripts, we analyzed GFP-TDP-43 transcripts by 3′ RACE analysis using primers specific for the GFP reporter sequence (Fig. 1C). As shown for the x7 (−Tet) lane, a single product was obtained (band 1) containing a TDP-43 3′ UTR sequence ending at pA1. Upon induction (+Tet), the x7 band 1 diminished and a new product appeared (band 2), which, based on sequencing, derives from the TDP-43 3′ UTR ending at a cryptic PAS, pA2. Quantification of this PAS switch was shown to be reproducibly fivefold (Supplemental Fig. 1). The formation of band 2 is caused by the activation of intron 7 splicing, which in turn eliminates PAS pA1 as well as the entire TDPBR. These results suggest that splicing of intron 7 is a critical event for TDP-43 autoregulation. To test this possibility, we mutated the splice sites flanking intron 7 to obtain the construct x7Δgt-ag (Fig. 1B). Following transfection of x7Δgt-ag into the HEK-293 cell line with or without Tet activation of TDP-43 expression, we observed that the lack of intron 7 splice sites prevents the autoregulation seen with x7 (Fig. 1B). Thus, only band 1 is detectible in both −Tet and +Tet lanes (Fig. 1C, right panel). Overall, these initial results suggest that TDP-43 overexpression may act to enhance intron 7 splicing, thereby preventing recognition of the intronic pA1 PAS and in turn causing a switch in PAS usage to pA2.

Switch in splicing patterns and PAS usage on the endogenous gene following TDP-43 overexpression

We next tested whether the above GFP-3′UTR construct autoregulation by TDP-43 overexpression mirrors regulation of endogenous TDP-43. 3′ RACE analysis of the endogenous TDP-43 transcripts showed that TDP-43 overexpression switches the profile from an intron 7–containing RNA that uses pA1 (band 1) to the smaller band 2 product that lacks intron 7 and so uses the pA2 PAS. In effect, endogenous TDP-43 and x7 reporter constructs reproducibly give similar PAS switching when TDP-43 is overexpressed (Supplemental Fig. 1). It should be emphasized that for endogenous TDP-43, only two mRNAs are readily detectible by Northern blotting. The larger 4.2-kb mRNA retains introns 6 and 7 and uses the pA4 PAS, while the smaller 2.8-kb mRNA uses the intron 7 pA1 PAS (Ayala et al. 2011). Transcripts containing just intron 6 (i.e., band 2 with intron 7 spliced) are only detected at a low level by 3′ RACE and, in this case, use the pA2 PAS. Finally, transcripts containing only intron 7 (with intron 6 spliced) are undetectable even by RT–PCR (data not shown).

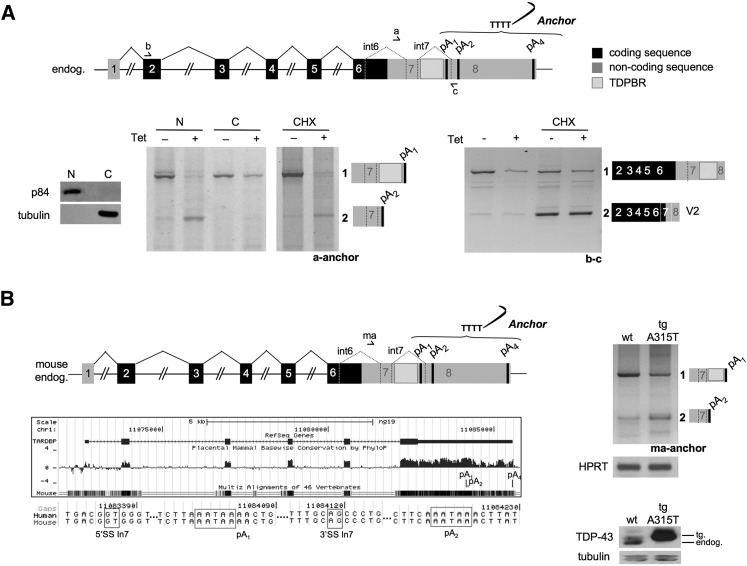

Our analysis of TDP-43 transcripts as above (Fig. 1) used total cellular RNA. However, we wished to test whether specific TDP-43 transcripts display a nuclear retention pattern. We therefore performed 3′ RACE on endogenous TDP-43 mRNA using separate nuclear and cytoplasmic RNA fractions isolated from cells with or without Tet induction of TDP-43 expression (Fig. 2A). While band 1 was detectable in both nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions, the autoregulation-associated band 2 was predominantly nuclear and therefore not available for translation (Fig. 2A, left panel, cf. the intensity of band 2 between the −Tet and +Tet conditions). These results neatly explain the rapid disappearance of the endogenous protein. This nuclear retention result provides the first indication that this form of TDP-43 autoregulation is different from NMD-associated autoregulation as shown for the minor V2 TDP-43 mRNA isoform (described above). In particular, we also show that translation inhibition by CHX treatment (Fig. 2A, CHX panel, primers a and anchor) does not affect the levels of the band 2 RNA that uses pA2. Finally, to prove that NMD was efficiently blocked in this experiment, we performed a PCR analysis on the same samples using primers that detected the V2 form in which both introns 6 and 7 are spliced (Fig. 2A, right panel, primers b and c). In this experiment, it is clear that the V2 mRNA undergoes NMD, as V2 levels increase upon CHX treatment. Importantly, V2 mRNA levels are unchanged following Tet induction of TDP-43. We conclude that V2 mRNA is not involved in TDP-43 autoregulation, as its expression does not change in response to the TDP-43 overexpression even when the NMD mechanism is blocked by CHX treatment or following Upf1 knockdown (Ayala et al. 2011). Finally, with regard to the endogenous TDP-43, we note that use of the pA4 site followed a nuclear versus cytoplasmic bias similar to that observed above for pA2. However, with this PAS, no RT–PCR product was detected (Fig. 2) because of the excessive distance between this site and the forward primer. A nuclear retention bias for mRNA using pA4, however, was shown by RT-qPCR analysis using primers that span the pA4 region (Supplemental Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Endogenous TDP-43 in mice and humans; mRNA intron 7 splicing, PAS usage, and mRNAs nuclear retention. (A) Schematic representation of human TDP-43. Arrows show the positions of the primers used. 3′ RACE analysis of endogenous TDP-43 before (−Tet) and following (+Tet) TDP-43 transgene induction performed on nuclear (N) and cytoplasmic (C) RNA fractions or following CHX treatment. The forward primer was annealed to intron 6 (a), while the anchor was used as the reverse primer. (Right) The same samples were checked for the amplification of the endogenous variant V2 mRNA using primers b and c as indicated. All PCR products were sequenced to establish their identity. Distribution of p84 and tubulin was analyzed by Western blotting. (B, left) Schematic diagram of mouse TDP-43 showing sequence conservation between humans and mice and detailed alignment of the sequence corresponding to intron 7 splice sites and the various PAS. (Right) 3′ RACE analysis of endogenous murine TDP-43 from control (wild-type [wt]) and transgenic tg A315T mouse brains. The forward primer is annealed on intron 6 (named ma), while the anchor was used as the reverse primer. A representation of amplified mRNA isoforms (bands 1 and 2) is also shown as confirmed by sequencing. HPRT mRNA amplification was used as a control. (Bottom right) Endogenous and transgenic tg A315T protein expression was measured by Western blotting using anti-TDP-43, with anti-tubulin as control.

Intron 7 splicing and PAS usage in a murine TDP-43 overexpression model

To validate the results obtained in our HEK-293 cell line, we took advantage of a murine TDP-43 transgenic mouse model that overexpresses a mutant form (TDP-43A315T) of the protein (Wegorzewska et al. 2009). TDP-43 autoregulation was shown to occur in this transgenic mouse, as overexpression of the human transgene down-regulates the endogenous mouse TDP-43 protein (Wegorzewska et al. 2009). Strikingly, murine TDP-43 conserves a gene structure over the 3′ UTR closely similar to its human counterpart, including intron 7-containing pA1 as well as the close downstream pA2 PAS (Fig. 2B). We therefore performed 3′ RACE analysis on murine TDP-43 and observed identical autoregulation of PAS choice between the human and mouse systems, as predicted from the close homology between their 3′ UTR sequences (Fig. 2B, left panels). In particular, intron 7 3′ RACE analysis of endogenous brain TDP-43 transcripts from control (wild-type) and transgenic TDP-43A315T (tg A315T) mice using a specific intron 6 forward primer (ma) was performed together with HPRT as a housekeeping gene control. Analysis of control littermates was compared with the transgenic line that overexpresses TDP-43 and showed an effect that closely resembled the pA1-to-pA2 switch observed in the human HEK-293 cell lines, including the processing of intron 7 in a significant amount of total transcript (Fig. 2B, top right panels). Taken together, these results show that the autoregulatory process that mediates PAS switching in human TDP-43 is conserved in mice.

RNA polymerase II (Pol II) density through the TDPBR in the TDP-43 gene 3′ UTR

We sought to better understand how TDP-43 overexpression acts to promote intron 7 splicing, resulting in the formation of a nuclear-retained transcript that uses pA2. It is well established that RNA processing, both splicing and cleavage/polyadenylation, occurs cotranscriptionally and that transcription kinetics can directly affect RNA processing specificity (Kornblihtt 2007; Moore and Proudfoot 2009). We therefore considered the possibility that TDP-43 levels might directly or indirectly affect TDP-43 transcription. The profile of nascent RNA and Pol II density over TDP-43 was therefore assessed under both normal conditions and following Tet-induced TDP-43 transgene overexpression.

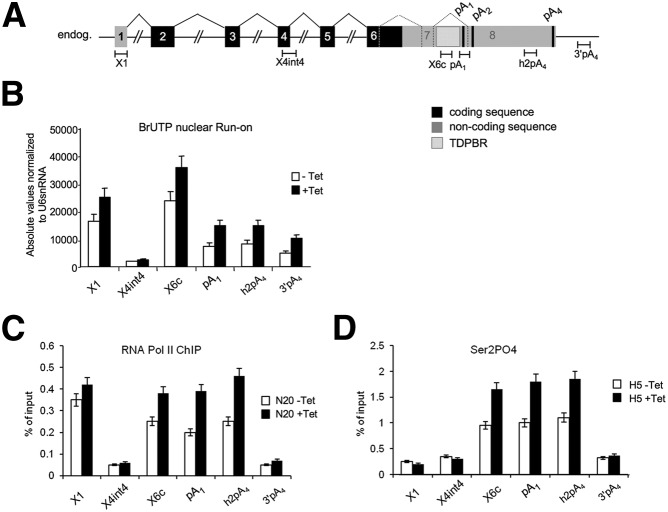

As a first approach, Br-UTP run-on assays were performed across TDP-43 from the promoter to 500 nt beyond the 3′ UTR using different probes (Fig. 3A). This technique allows detection of nascent transcription by the isolation and RT–PCR analysis of BrU-labeled RNA synthesized during the run-on reaction. Figure 3B shows a high run-on signal over the promoter region (X1) that then drops to lower levels in the gene body (X4int4), indicative of promoter-proximal pausing as generally observed for protein-coding genes (Guenther et al. 2007). Strikingly higher run-on signals were again observed over the TDPBR (X6c signal) and, to a lesser extent, in the downstream regions of the gene (pA1, h2pA4, and 3′pA4 signal). Overexpression of TDP-43 accentuated this asymmetric nascent RNA profile with even higher levels of nascent RNA detectible over the TDPBR. This correlates with the capacity of TDP-43 to bind the TDPBR as previously shown (Ayala et al. 2011) and confirmed the more recent cross-linking immunoprecipitation (CLIP) studies (Polymenidou et al. 2011; Tollervey et al. 2011). Furthermore, these results suggest that overexpression of TDP-43 causes additional Pol II stalling that could induce the more efficient recognition and splicing of intron 7 (Kornblihtt 2007), with the consequent removal of the pA1. Our results also show that TDP-43 overexpression promotes an increase in nascent RNA over the region downstream from pA1 and beyond pA4. This increased level of TDP-43 nascent RNA may reflect transcripts that fail to complete RNA maturation steps. This could further contribute to transcript degradation and hence to the autoregulation mechanism. To confirm that higher nascent RNA levels over the TDPBR are due to Pol II stalling, we next carried out chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) analysis using an antibody against the N terminus of the largest Pol II subunit (N20) (Fig. 3C) and the H5 antibody that specifically recognizes Pol II C-terminal domain (CTD) repeats phosphorylated at Ser 2 (Fig. 3D). The profiles obtained for these experiments were similar to the BrUTP run-on analysis, confirming that TDP-43 overexpression promotes an elongation/termination defect as indicated by increased Pol II signals extending from the TDPBR to 3′ of pA4.

Figure 3.

Pol II stalling on the TDPBR sequence. (A) Schematic diagram of TDP-43 showing positions of ChIP probes used. (B) BrU nuclear run-on assay measuring nascent transcription in different regions of endogenous TDP-43 under normal conditions (−Tet) and following TDP-43 overexpression (+Tet). (C,D) ChIP analysis using N20 Pol II and H5 Pol II CTDser2P antibodies probing the same regions of TDP-43.

TDP-43 overexpression blocks recognition of pA1 by CstF-64

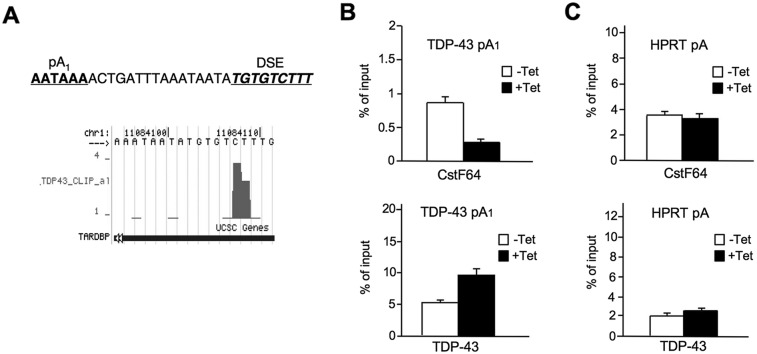

We also considered the possibility that TDP-43 overexpression might directly affect TDP-43 PAS selection and, in particular, could act by blocking pA1 usage. This would in turn promote intron 7 splicing. In particular, the GU-rich RNA recognition specificity for TDP-43 (Buratti and Baralle 2001) is remarkably similar to the binding specificity of the key cleavage polyA factor CstF-64, which is represented by GU3–5-U2–4 (Takagaki and Manley 1997). Indeed, the pA1-surrounding sequence possesses a clear GU-rich downstream sequence element (DSE) that is known to provide for efficient CstF-64 recruitment. Furthermore, CLIP analysis of TDP-43 to the TDPBR shows that binding extends through to pA1, with a peak of interaction lying directly over the PAS DSE (Fig. 4A). We therefore performed RNA immunoprecipitation (RIP) analysis using TDP-43- and CstF-64-specific antibodies with or without TDP-43 overexpression. The selected RNA was subjected to quantitative RT–PCR (RT-qPCR) with primers directly encompassing pA1. As a control, the major PAS of HPRT1 (HPRT pA) that has no well-defined DSEs in its sequence was similarly tested using specific primers with the same RNA samples. For endogenous TDP-43, CstF-64 antibody yielded a clear RIP signal for pA1 under normal conditions that was reduced fourfold following TDP-43 overexpression (Fig. 4B, top graph). In a reciprocal manner, TDP-43 antibody immunoprecipitated twofold more pA1 RNA when overexpressed (Fig. 4B, bottom graph). In contrast, control probes against HPRT1 pA showed little TDP-43 RIP signal whether induced or not, while CstF-64 signal remained unchanged between induced and uninduced samples (Fig. 4C, top and bottom graphs). Taken together, these results establish that TDP-43 overexpression specifically outcompetes CstF-64 binding to the pA1 DSE during TDP-43 transcription.

Figure 4.

Competition between TDP-43 and CstF-64 across the pA1 site. (A) Nucleotide sequence of TDP-43 pA1 DSE (top) and a hit frequency plot of TDP-43 CLIP data (bottom) (from the University of California at Santa Cruz Genome Browser). (B) RIP analysis of TDP-43 and CstF-64 proteins on endogenous TDP-43 across pA1 under normal (−Tet) and TDP-43 overexpression (+Tet) conditions. (C) RIP for TDP-43 and CstF-64 proteins across the HPRT PAS used as control.

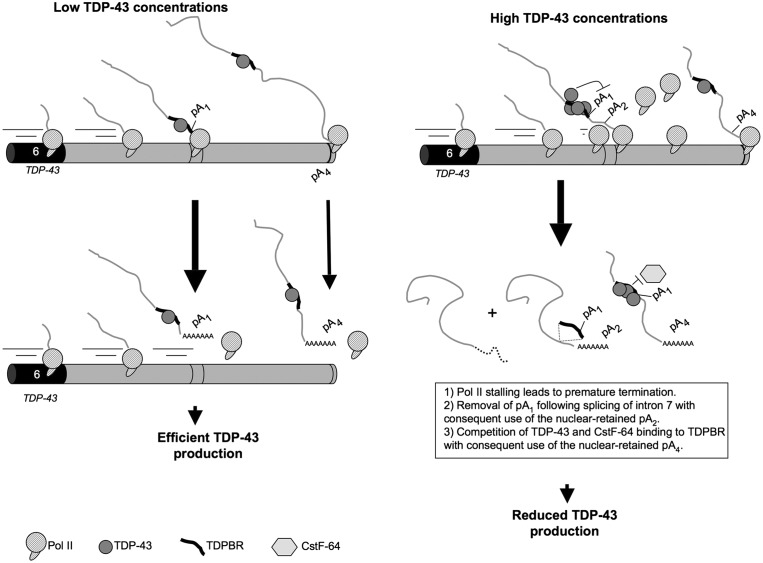

The interconnections between alternative splicing and polyadenylation represent an important level of regulation (Lutz and Moreira 2011; Proudfoot 2011). In recent years, the splicing process has been shown to affect polyadenylation through the recognition of a gene's terminal intron 3′ splice site (Dye and Proudfoot 1999), “licensing” release of polyadenylated mRNA from Pol II (Rigo and Martinson 2009), and protecting pre-mRNAs from premature cleavage and polyadenylation through the U1snRNP molecule pathway (Kaida et al. 2010). The autoregulation process for TDP-43 expression defined in this study shows some parallels with regulated PAS selection for immunoglobulin heavy chain (IgH) mRNA (Takagaki and Manley 1998) and the the HuR protein (Dai et al. 2012). However, there are fundamental differences between TDP-43 autoregulation and these genes. In neither the IgH nor HuR system is the splicing process coupled closely to CstF-64 competition. Our data point to a combined mechanism of TDP-43 autoregulation where each component of the coupled transcription RNA processing mechanism, transcriptional stalling, consequent splicing activation, and CstF64 displacement, plays a combined role in modulating PAS selection. We therefore propose a novel autoregulation model for TDP-43 (Fig. 5). In this model, increased nuclear levels of TDP-43 result in increased TDPBR occupancy. The higher density of TDP-43 in this region, which also extends into the DSE of pA1, elicits a “slowdown” of Pol II over intron 7 coinciding with both the pA1 PAS and intron 7 3′ splice site. Since Pol II pausing is known to favor recognition of suboptimal splice sites by the spliceosomal complex (Kornblihtt 2007), removal of intron 7 including pA1 is enhanced, thus enforcing pA2 selection. In addition, TDP-43 binding to intron 7 may facilitate its removal by favoring a particular conformation of the intronic sequence and/or by recruiting other splicing factors to this region. Pre-mRNA molecules that do not undergo intron 7 splicing continue their synthesis toward the pA4 PAS or beyond. However, in this situation, the processing at pA1 is hampered by TDP-43 binding that reduces CstF-64 interaction with its target sequence in the pA1 site. As both pA2 and the distal PAS (pA4) are significantly retained in the nucleus and rapidly degraded, it follows that a reduction of TDP-43 protein levels in the cell will occur.

Figure 5.

Model of TDP-43 autoregulatory mechanism. Under normal conditions, Pol II synthesizes the nascent TDP-43 mRNA from TDP-43, generating two main TDP-43 mRNA isoforms using either pA1 or pA4, which results in efficient TDP-43 protein expression. When the levels of nuclear TDP-43 rise, there is an increase in the binding of TDP-43 to the TDPBR. This promotes a dual effect: increased intron 7 splicing with the physical removal of the pA1 signal, and direct competition with the cleavage polyA factor Cstf-64 over pA1. Moreover, Pol II stalling may lead to premature termination of transcription and rapid degradation.

In conclusion, TDP-43 autoregulation represents an alternative to regulatory mechanisms based on classical NMD pathways. This may explain some of the processes that lead to TDP-43 aggregation and consequent neuronal death in neurodegenerative diseases. Since aberrant TDP-43 levels result in cytoplasmic/nuclear aggregation, this may act as a TDP-43 “sink” that promotes the setup of a vicious cycle of ever-increasing TDP-43 production that in the long run will be harmful to cellular metabolism. Indeed, there is already evidence that deregulation of TDP-43 protein levels occurs in patient samples. Thus, several studies report an increase of TDP-43 mRNA levels in the brains of patients affected by various forms of frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD) (Mishra et al. 2007; Chen-Plotkin et al. 2008; Kabashi et al. 2008; Weihl et al. 2008). Moreover, we know from several recent animal models and adeno-associated virus (AAV) overexpression systems that raising TDP-43 concentrations can lead to neurodegeneration (Tatom et al. 2009; Barmada et al. 2010; Li et al. 2010; Liachko et al. 2010; Wils et al. 2010; Xu et al. 2010; Wegorzewska and Baloh 2011). We predict that a deeper understanding of the mechanisms that control production of TDP-43 within the cell may lead to the development of improved therapeutic approaches for these pathologies.

Materials and methods

Cell lines, nuclear/cytoplasmic fractionation, and an A315T murine model

The 293 TDP-43 wild-type-inducible cell line has been previously described (Ayala et al. 2011). Cells were cotransfected with 3 μg of GFP-3′UTR construct variants and 0.5 μg of pEGFP-C2 (Invitrogen) or DiGFP (generously donated by Dr. Christian Beetz) using the calcium phosphate method. Nuclear/cytoplasmic fractionation and RNA extraction were performed as previously described (Ayala et al. 2008). For the experiments performed on mouse brains, 2-mo-old mouse C57 wild-type littermates and transgenic TDP-43A315T were used.

Plasmid construction, 3′ RACE and RT–PCR analysis, and immunoblotting

The GFP-3′UTR wild-type and Δ669 recombinant constructs have been previously described (Ayala et al. 2011). GFP-3′UTR construct variants were made by PCR amplification using PfuI polymerase followed by DpnI digestion using appropriate primers (sequences are available on request). Total RNA was reverse-transcribed using an oligonucleotide (dT)20 V anchor. Protein detection was carried out with standard Western blotting techniques. The antibodies used are listed in the Supplemental Material.

Br-UTP nuclear run-on analysis and ChIP and RIP analysis

The Br-UTP nuclear run-on assay was carried out as described previously (Skourti-Stathaki et al. 2011) on uninduced and induced 293 cell lines. cDNA was synthesized using 10 μL of eluted RNA and 125 ng of random hexamers with SuperScript III RT (Invitrogen). qRT–PCR was performed as for RIP-ChIP analysis. The data were normalized to U6 snRNA. ChIP analysis was performed as previously described (Skourti-Stathaki et al. 2011) using qRT–PCR analysis of selected DNA fractions. cDNA of eluted RNA was prepared using random hexamers, and qRT–PCR was performed as above (primer sequences available on request). Immunoprecipitation levels were calculated as percentage of input using the formula (IP × Bgr/Input) × 100. The antibodies used are listed in the Supplemental Material.

TDP-43 CstF-64 competition and statistical analysis

RNA fractions isolated from cells with or without TDP-43 overexpression were immunoprecipitated using TDP-43- or CstF-64-specific antibodies. As control, the major PAS of the HPRT gene was similarly tested using specific primers with the same RNA samples (sequence available on request). Significant differences (P < 0.05) in GFP protein expression values were determined using ANOVA with a Newman-Keuls post-test.

Acknowledgments

We thank Patrizia Longone and Michele Nutini (Fondazione Santa Lucia, Rome) for their gift of A315T mouse brains, Jernej Ule for the TDP-43 CLIP files, and Somdutta Dhir for bioinformatics analyses. This work was supported by AriSLA. A.D. is supported by an EMBO long-term fellowship. A.D. and N.J.P. are supported by a Programme Grant from the Wellcome Trust.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available for this article.

Article is online at http://www.genesdev.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gad.194829.112.

References

- Ayala YM, Zago P, D'Ambrogio A, Xu YF, Petrucelli L, Buratti E, Baralle FE 2008. Structural determinants of the cellular localization and shuttling of TDP-43. J Cell Sci 121: 3778–3785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayala YM, De Conti L, Avendano-Vazquez SE, Dhir A, Romano M, D'Ambrogio A, Tollervey J, Ule J, Baralle M, Buratti E, et al. 2011. TDP-43 regulates its mRNA levels through a negative feedback loop. EMBO J 30: 277–288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barmada SJ, Skibinski G, Korb E, Rao EJ, Wu JY, Finkbeiner S 2010. Cytoplasmic mislocalization of TDP-43 is toxic to neurons and enhanced by a mutation associated with familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurosci 30: 639–649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buratti E, Baralle FE 2001. Characterization and functional implications of the RNA binding properties of nuclear factor TDP-43, a novel splicing regulator of CFTR exon 9. J Biol Chem 276: 36337–36343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buratti E, Baralle FE 2011. TDP-43: New aspects of autoregulation mechanisms in RNA binding proteins and their connection with human disease. FEBS J 278: 3530–3538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen-Plotkin AS, Geser F, Plotkin JB, Clark CM, Kwong LK, Yuan W, Grossman M, Van Deerlin VM, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM 2008. Variations in the progranulin gene affect global gene expression in frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Hum Mol Genet 17: 1349–1362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai W, Zhang G, Makeyev EV 2012. RNA-binding protein HuR autoregulates its expression by promoting alternative polyadenylation site usage. Nucleic Acids Res 40: 787–800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dye MJ, Proudfoot NJ 1999. Terminal exon definition occurs cotranscriptionally and promotes termination of RNA polymerase II. Mol Cell 3: 371–378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guenther MG, Levine SS, Boyer LA, Jaenisch R, Young RA 2007. A chromatin landmark and transcription initiation at most promoters in human cells. Cell 130: 77–88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabashi E, Valdmanis PN, Dion P, Spiegelman D, McConkey BJ, Vande Velde C, Bouchard JP, Lacomblez L, Pochigaeva K, Salachas F, et al. 2008. TARDBP mutations in individuals with sporadic and familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nat Genet 40: 572–574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaida D, Berg MG, Younis I, Kasim M, Singh LN, Wan L, Dreyfuss G 2010. U1 snRNP protects pre-mRNAs from premature cleavage and polyadenylation. Nature 468: 664–668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornblihtt AR 2007. Coupling transcription and alternative splicing. Adv Exp Med Biol 623: 175–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lareau LF, Brooks AN, Soergel DA, Meng Q, Brenner SE 2007a. The coupling of alternative splicing and nonsense-mediated mRNA decay. Adv Exp Med Biol 623: 190–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lareau LF, Inada M, Green RE, Wengrod JC, Brenner SE 2007b. Unproductive splicing of SR genes associated with highly conserved and ultraconserved DNA elements. Nature 446: 926–929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lejeune F, Maquat LE 2005. Mechanistic links between nonsense-mediated mRNA decay and pre-mRNA splicing in mammalian cells. Curr Opin Cell Biol 17: 309–315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Ray P, Rao EJ, Shi C, Guo W, Chen X, Woodruff EA III, Fushimi K, Wu JY 2010. A Drosophila model for TDP-43 proteinopathy. Proc Natl Acad Sci 107: 3169–3174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liachko NF, Guthrie CR, Kraemer BC 2010. Phosphorylation promotes neurotoxicity in a Caenorhabditis elegans model of TDP-43 proteinopathy. J Neurosci 30: 16208–16219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutz CS, Moreira A 2011. Alternative mRNA polyadenylation in eukaryotes: An effective regulator of gene expression. WIREs RNA 2: 22–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra M, Paunesku T, Woloschak GE, Siddique T, Zhu LJ, Lin S, Greco K, Bigio EH 2007. Gene expression analysis of frontotemporal lobar degeneration of the motor neuron disease type with ubiquitinated inclusions. Acta Neuropathol 114: 81–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore MJ, Proudfoot NJ 2009. Pre-mRNA processing reaches back to transcription and ahead to translation. Cell 136: 688–700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni JZ, Grate L, Donohue JP, Preston C, Nobida N, O'Brien G, Shiue L, Clark TA, Blume JE, Ares M Jr 2007. Ultraconserved elements are associated with homeostatic control of splicing regulators by alternative splicing and nonsense-mediated decay. Genes Dev 21: 708–718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polymenidou M, Lagier-Tourenne C, Hutt KR, Huelga SC, Moran J, Liang TY, Ling SC, Sun E, Wancewicz E, Mazur C, et al. 2011. Long pre-mRNA depletion and RNA missplicing contribute to neuronal vulnerability from loss of TDP-43. Nat Neurosci 14: 459–468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proudfoot NJ 2011. Ending the message: Poly(A) signals then and now. Genes Dev 25: 1770–1782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigo F, Martinson HG 2009. Polyadenylation releases mRNA from RNA polymerase II in a process that is licensed by splicing. RNA 15: 823–836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saltzman AL, Kim YK, Pan Q, Fagnani MM, Maquat LE, Blencowe BJ 2008. Regulation of multiple core spliceosomal proteins by alternative splicing-coupled nonsense-mediated mRNA decay. Mol Cell Biol 28: 4320–4330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skourti-Stathaki K, Proudfoot NJ, Gromak N 2011. Human senataxin resolves RNA/DNA hybrids formed at transcriptional pause sites to promote Xrn2-dependent termination. Mol Cell 42: 794–805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takagaki Y, Manley JL 1997. RNA recognition by the human polyadenylation factor CstF. Mol Cell Biol 17: 3907–3914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takagaki Y, Manley JL 1998. Levels of polyadenylation factor CstF-64 control IgM heavy chain mRNA accumulation and other events associated with B cell differentiation. Mol Cell 2: 761–771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatom JB, Wang DB, Dayton RD, Skalli O, Hutton ML, Dickson DW, Klein RL 2009. Mimicking aspects of frontotemporal lobar degeneration and Lou Gehrig's disease in rats via TDP-43 overexpression. Mol Ther 17: 607–613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tollervey JR, Curk T, Rogelj B, Briese M, Cereda M, Kayikci M, Konig J, Hortobagyi T, Nishimura AL, Zupunski V, et al. 2011. Characterizing the RNA targets and position-dependent splicing regulation by TDP-43. Nat Neurosci 14: 452–458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wegorzewska I, Baloh RH 2011. TDP-43-based animal models of neurodegeneration: New insights into ALS pathology and pathophysiology. Neurodegener Dis 8: 262–274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wegorzewska I, Bell S, Cairns NJ, Miller TM, Baloh RH 2009. TDP-43 mutant transgenic mice develop features of ALS and frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci 106: 18809–18814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weihl CC, Temiz P, Miller SE, Watts G, Smith C, Forman M, Hanson PI, Kimonis V, Pestronk A 2008. TDP-43 accumulation in inclusion body myopathy muscle suggests a common pathogenic mechanism with frontotemporal dementia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatr 79: 1186–1189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wils H, Kleinberger G, Janssens J, Pereson S, Joris G, Cuijt I, Smits V, Ceuterick-de Groote C, Van Broeckhoven C, Kumar-Singh S 2010. TDP-43 transgenic mice develop spastic paralysis and neuronal inclusions characteristic of ALS and frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci 107: 3858–3863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu YF, Gendron TF, Zhang YJ, Lin WL, D'Alton S, Sheng H, Casey MC, Tong J, Knight J, Yu X, et al. 2010. Wild-type human TDP-43 expression causes TDP-43 phosphorylation, mitochondrial aggregation, motor deficits, and early mortality in transgenic mice. J Neurosci 30: 10851–10859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]