Abstract

Although many proteins have been shown to affect the transition of primordial follicles to the primary stage, factors regulating the formation of primordial follicles remains sketchy at best. Differentiation of somatic cells into early granulosa cells during ovarian morphogenesis is the hallmark of primordial follicle formation; hence, critical changes are expected in protein expression. We wanted to identify proteins, the expression of which would correlate with the formation of primordial follicles as a first step to determine their biological function in folliculogenesis. Proteins were extracted from embryonic (E15) and 8-day old (P8) hamster ovaries and fractionated by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis. Gels were stained with Proteosilver, and images of protein profiles corresponding to E15 and P8 ovaries were overlayed to identify protein spots showing altered expression. Some of the protein spots were extracted from SyproRuby-stained preparative gels, digested with trypsin, and analyzed by mass spectrometry. Both E15 and P8 ovaries had high molecular weight proteins at acidic, basic, and neutral ranges; however, we focused on small molecular weight proteins at 4-7 pH range. Many of those spots might represent post-translational modification. Mass spectrometric analysis revealed the identity of these proteins. The formation of primordial follicles on P8 correlated with many differentially and newly expressed proteins. Whereas Ebp1 expression was downregulated in ovarian somatic cells, Sfrs3 expression was specifically upregulated in newly formed granulosa cells of primordial follicles on P8. The results show for the first time that the morphogenesis of primordial follicles in the hamster coincides with altered and novel expression of proteins involved in cell proliferation, transcriptional regulation and metabolism. Therefore, formation of primordial follicles is an active process requiring differentiation of somatic cells into early granulosa cells and their interaction with the oocytes.

Keywords: primordial follicle, proteomics, hamster, ovary

Introduction

The formation of primordial follicles requires the interaction of the oocytes with surrounding somatic cells, which differentiate into early granulosa cells (Byskov, 1986,Pepling, 2006). This event constitutes the critical first step in folliculogenesis and affects fertility (Skinner, 2005,van den Hurk and Zhao, 2005). However, the mechanism controlling this process remains obscure. Evidence indicates that certain hormones and growth factors may facilitate primordial follicle formation. FSH (Roy and Albee, 2000) (FSH), growth differentiation factor-9 (GDF9) (Dong, Albertini, Nishimori et al., 1996,Wang and Roy, 2006), bone morphogenetic protein (BMP15) (Hashimoto, Moore and Shimasaki, 2005) have been found to affect follicle formation, including primordial follicles. Estrogen plays a critical role in primordial follicle formation (Wang and Roy, 2007) though the mechanism(s) of its action remains undefined. A physiological concentration of estradiol-17b (E2) facilitates whereas higher doses compromise the formation and development of primordial follicles (Wang and Roy, 2007). Moreover, blocking the action of endogenous E2 causes a decline in follicle formation (Wang and Roy, 2007). Using cDNA array of fetal human ovaries, Fowler et al(Fowler, Flannigan, Mathers et al., 2009) have documented changes in gene expression during early folliculogenesis. However, changes in the gene expression during the precise period of primordial follicle formation remain undetermined. Further, whether all transcripts undergo translation during primordial folliculogenesis remains unknown, and there are inconsistencies in upregulated or downregulated transcriptome in rat versus human ovaries during the formation of primordial follicles (Fowler et al., 2009,Kezele, Ague, Nilsson et al., 2004). Because proteins carry biological functions, we focus on the expression of proteins during the critical period of primordial follicle formation to understand the mechanism regulates this process. The objective of the present study was to use proteomics approach to identify proteins, the expression of which would correlate with the formation of primordial follicles. We used hamsters because primordial follicles formed on 8th day of postnatal life, thus providing the opportunity to obtain ovaries completely devoid of primordial follicles and ovaries with the first cohort of primordial follicles (Lyall, Zilberstein, Gazit et al., 1989,Roy and Albee, 2000,Wang and Roy, 2007). We presumed that these two widely separated time points in ovary morphogenesis would allow us to identify novel proteins expressed in ovarian cells when the oocytes and pregranulosa cells assembled to form the primordial follicles.

Materials and methods

Chemicals and Animals

The rabbit polyclonal antibody to Ebp1 was purchased from Lifespan Biosciences (Seattle, WA), isoelectrophoresis gel strips and chemical were from GE Healthcare (Piscataway, NJ), PCR chemicals were from Roche Molecular Biochemicals (Indianapolis, IN), Pharmacia Biotech Boehringer (Piscataway, NJ), and Invitrogen. Quantitative PCR primers and probes were synthesized in the Eppley DNA synthesis Core Facility (University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE). Second antibodies for Western blotting chemiluminescence were from Jackson Immunoresearch, Inc. (West Grove, PA); ECL advance Western blotting detection kit was from GE Healthcare (Buckinghamshire, UK); Optitran nitrocellulose transfer membrane was from Schleicher & Schuell Bioscience (Dassel, Germany); the RNeasy mini kit was from Qiagen Inc. (Valencia, CA). All other molecular-grade chemicals were purchased from Sigma Chemical Company, Fisher Scientific Corporation (Pittsburgh, PA), or United States Biochemical (Cleveland, OH).

Golden hamsters (90-100g) were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Charles River, MA) and maintained in a climate controlled room with 14 h light and 10 h dark with free access to food and water. The use of hamsters for this study was according to the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and the U.S. Department of Agriculture guidelines, and was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Females with at least three consecutive estrous cycles were mated with males in the evening of proestrus, and the presence of sperm in the vagina the next morning was considered the first day of pregnancy. Hamster gestation lasts for 16 days, and pups are born on the 16th day of gestation, which was considered the first day of postnatal life (P1).

Preparation of ovarian samples for 2-dimensional (2D) gel electrophoresis

Ovaries were collected from 15-day old (E15) fetuses when ovaries contained undifferentiated somatic cells and oocytes in the oocyte clusters, and from 8-day (P8) old hamsters when ovaries contained the first cohort of primordial follicles, but no other stage of follicles (Roy and Albee, 2000). Ovaries were either homogenized by Omni 2000 homogenizer or sonified in 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.4 containing 100 mM NaCl, 1mM EDTA, 1mM EGTA, 1mM NaF, 20 mM Na4P2O7, 1% Triton X-100, 10% glycerol, 0.1% SDS and 0.5% deoxycholate, 0.1ml/ml of a protease inhibitor cocktail and 200 mM Naorthovanadate on ice. The homogenate was centrifuged and the supernatant was used for protein estimation by BCA method (Pierce, Rockford, IL).

Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis

Protein samples were processed and cleaned using 2-D electrophoresis kit (GE Healthcare) according to the manufacturer instructions. Proteins were subjected to isolectric focusing (IEF) using immobiline dry strip gels with a non-linear immobilized pH gradient (NL-IPG) of pH 3-10 or pH 4-7 (GE healthcare). Gels were loaded with 60 μg protein for analytical gels or 900 μg protein for preparative gels by rehydrating the gels for 20hr in IPG buffer containing 100 μl Destreak, 10mM DTT and sample protein. Focusing was done in the IPGphor 3 (GE healthcare) isolectric focusing apparatus as instructed by the manufacturer. Immediately following the IEF, focused strips were equilibrated for 15 mins in reducing SDS-equilibration buffer (6 M urea, 75 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.8, 29.3% glycerol, 2% SDS, 0.002% bromophenol blue and 100 μg dithiotheritol (DTT) per 10 ml), and 15 mins in alkylating SDS-equilibration buffer (6M urea, 75mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.8, 29.3% glycerol, 2% SDS, 0.002% bromophenol blue and 250 μg iodoacetamide (IAA) per 10 ml).

Second dimension gel electrophoresis was performed in a 20 cm 12% polyacrylamide gel. Equilibrated IEF strips were placed on top of the resolving gels and proteins were fractionated at 25 mAmp per gel. Analytical gels were stained with ProteoSilver stain (Sigma Chemical Company, St. Louis, MO), whereas preparative gels were stained with SyproRuby (Sigma) as per manufacturer's instructions.

In gel digest

Proteins of interest were excised from the gel using sterile glass capillaries, excess liquid was removed, and gel pieces were destained using 100 μl of 50% acetonitrile (ACN) and 25 mM ammonium bicarbonate (ABC). Gel pieces were shaken at room temperature for 10 minutes, and the liquid removed. The destaining steps were repeated again, then 100 μl ACN was added. Samples were incubated for 3-5 minutes at room temperature, all excess liquid was removed, and samples were dried in a biosafety cabinet for 10 minutes. One hundred microliters fresh reducing agent (1.5 mg DTT per ml 25 mM ABC) was added and samples were incubated for 30 min at 37°C. The supernatant was removed, and 100 μl fresh alkylating agent (10 mg IAA per ml 25 mM ABC) was added and samples were incubated for 30 minutes at room temperature in the dark. After removing the liquid, samples were washed with 100 μl 50 mM ABC and then with 100 μl 50% ACN in 25 mM ABC. The samples were washed with 100 μl 100% ACN and dried for 5-10 min in a biosafety cabinet. Proteins were digested with 15 μl of trypsin (25 ng/μl) at room temperature for 15 min. Excess liquid was removed, 25 mM ABC was added, and samples were kept overnight at 37°C in an air incubator. Peptides were extracted with 1 μl of 10% formic acid with shaking at room temperature for 10 minutes. The liquid was transferred to a fresh 1.5 ml tube and placed on ice (extract #1). The gel pieces were reextracted with 60% ACN/0.1% formic acid with shaking for 10 min at room temperature, the supernatant was added to extract #1 and samples were concentrated using a speedvac to 10 μl. Samples were brought up to 10 μl using 0.1% formic acid if necessary.

LC/MS/MS analysis

Extracted peptides were analyzed via LC/MS/MS on an Agilent ion trap (model 6340) Mass spectrometer with an HPLC-chip interface at the laboratory of Dr. Nichole Reisdorph at the NJH Mass Spectrometry Facility (University of Colorado Medical Center, Denver, CO). All HPLC components were Agilent 1100. Buffer A of the nanopump was comprised of 0.1% formic acid in HPLC grade water, and buffer B was 90% acetonitrile, 10% HPLC water, and 0.1% formic acid. The loading pump utilized 3% acetonitrile, 97% HPLC grade water and 0.1% formic acid. A so-called “short” HPLC chip (Agilent) was used which consisted of a 40 nL enrichment column and a 75 μm × 50 mm analytical column combined on a single chip. Parameters for the ion trap were as follows: Voltage was set at 1750, drying gas 3.5 L/min, temperature 350°C, m/z 300-1800, and the instrument was operated in ultrascan mode for both MS and MS/MS. For MS/MS, m/z was 300-2200, and 4 precursors were selected per MS scan. Active exclusion was used after precursors were selected 3 times and exclusion was released after 30 seconds.

Data analysis

Raw data were extracted and searched using the Spectrum Mill search engine (Rev A.03.03. SR3, Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA). “Peak picking” was performed within SpectrumMill with the following parameters: during extraction the following parameters were applied: signal-to-noise was set at 25:1, a maximum charge state of 4 was allowed (z=4) and the program was directed to attempt to “find” a precursor charge state.

The information obtained from the Mass Spectrometry was then used for searching the mouse proteome database. Standards are run at the beginning of each day and at the end of a set of analyses for quality control purposes. During searching the following parameters were applied: Rodent database Swissprot version 11.1, modifications: carbamidomethylation as a fixed modification (cystienes searched with expected carbamidomethylation) and oxidized methionine as a variable modification (methionines may or may not be oxidized) enzyme = trypsin, maximum of 2 missed cleavages (trypsin sites that may not have been cleaved) precursor mass tolerance +/- 2.5 Daltons, product mass tolerance +/- 0.7 Daltons and maximum ambiguous precursor charge = 4.

Data were evaluated, and protein identifications were considered significant if the following confidence thresholds were met: minimum of 2 peptides per protein, protein score > 11, individual peptide scores > 7, and Scored Percent Intensity (SPI) of at least 70%. The SPI provided an indication of the percent of the total ion intensity that matches the peptide's MS/MS spectrum. Results were validated by Spectrum Mill's default validation parameters for both proteins and peptides. Manual inspection of spectra was further done to validate the match of the spectrum to the predicted peptide fragmentation pattern, hence increasing confidence in the identification. Identified proteins were further analyzed by the Integrated Pathway Analysis (IPA) software to determine their putative role in four important parameters, such as cell signaling, growth and proliferation, apoptosis/survival, and cell cycle, which were expected to be involved in primordial follicle morphogenesis.

2D gel electrophoresis was repeated three times with samples from different hamsters at indicated developmental ages for reproducibility and authenticity of protein change. Protein spots were pooled, extracted, digested and analyzed as described earlier to get three separate values. This was done to verify the reproducibility. The data were analyzed by 1-way ANOVA with Tukey's test. The level of significance was at 5%.

Biological verification of Mass-Spectrometry data

After analyzing the potential role of identified proteins in various cell functions by IPA software and also by database searches, we selected two candidate proteins for biological analysis based on their roles in cell proliferation, growth factor signaling, estrogen regulation and transcriptional control. Another important reason for selection was that reagents for biological analysis were readily available for these two proteins. Our primary goal was to verify the MS data. For this purpose, ovaries were collected from E15 and P8 hamsters, and were processed for immunofluorescence or immunoblot analysis of one upregulated and one downregulated proteins. Immunofluoresence localization was done essentially as described previously (Roy and Kole, 1995,Wang and Roy, 2010) using 6 μm thick frozen sections and a rabbit polyclonal antibody to Ebp1 (proliferation associated 2 G4; Pa2G4, ID#P50580) or a mouse monoclonal antibody to Sfrs3 (previously SRp20, ID#P84104). Images were captured in a Leica DM research microscope (North-Central Instruments, Inc, Annapolis, MN) equipped with a Qimaging Retiga digital camera (Surrey, Canada) using the Openlab software (Perkin-Elmer, Waltham, MA). The exposure time of the camera was set for subtracting background fluorescence that was present in sections incubated with the non-immune IgG of the host species. Ebp1 or Sfrs3 specific fluorescence was merged with nuclear DAPI (4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) signal to determine the cellular site of protein expression. We also used a rabbit polyclonal MVH (mouse vasa homologue) antibody along with Sfrs3 antibody to detect the oocytes because MVH was expressed only in the oocyte cytoplasm and the expression increased with oocyte growth (Wang and Roy, 2010). The same approach could not be used for Ebp1 because of the incompatibility of the antibodies. The nuclear signal was blue, and MVH signal was red in sections stained for Sfrs3 (green), whereas the nuclear signal was red in sections stained for Ebp1 (green). The gray-scale images for Ebp1 or Sfrs3 were quantified using the NIH Image J software and the data were presented as mean density per pixel. Approximately 20-30 oocytes, somatic cells or granulosa cells per ovary were quantified. The mean reflected an average density for each cell category for each ovary. Data from three ovaries were statistically analyzed using one-way ANOVA with Tukey's post-hoc test (InStat software, GraphPad, CA). The level of significance was 5% (P<0.05).

Immunoblot detection of ovarian Ebp1 and Sfrs3 was done as described previously (Roy and Kole, 1995,Wang and Roy, 2009,Yang, Wang, Shen et al., 2004). Briefly, ovaries from E15 or P8 were sonified in lysis buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 100 mM NaCl, 1mM EDTA, 1mM EGTA, 1mM NaF, 20 mM Na4P2O7, 200 mM Na-Na3VO4, 1% Triton X-100, 10% glycerol, 0.1% SDS and 0.5% deoxycholate) containing a protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma) and PMSF on ice. After measuring the protein concentration in 14,000 g supernatants by Micro BCA™ protein assay Kit (Pierce), 20 μg protein was fractionated in a SDS-polyacrylamide gel, electrotransferred to an Optitran nitrocellulose membrane (Schleicher and Schuell, Midwest Scientific, St. Louis, MO), and probed with the anti-Ebp1, anti-Sfrs3 or anti-tubulin antibody and an appropriate second antibody-HRP conjugate (Jackson Immunoresearch, West Grove, PA). The chemiluminescence signal was developed using the Advance Western blot detection kit (GE Healthcare), and recorded by a UVP gel documentation system (UVP, Upland, CA). The data were normalized with tubulin and presented as a ratio. Each group had at least two replicates of samples collected from different animals.

Results

Two-dimensional protein expression profiles of E15 and P8 ovaries, and Mass spectrometric analysis of selected protein spots

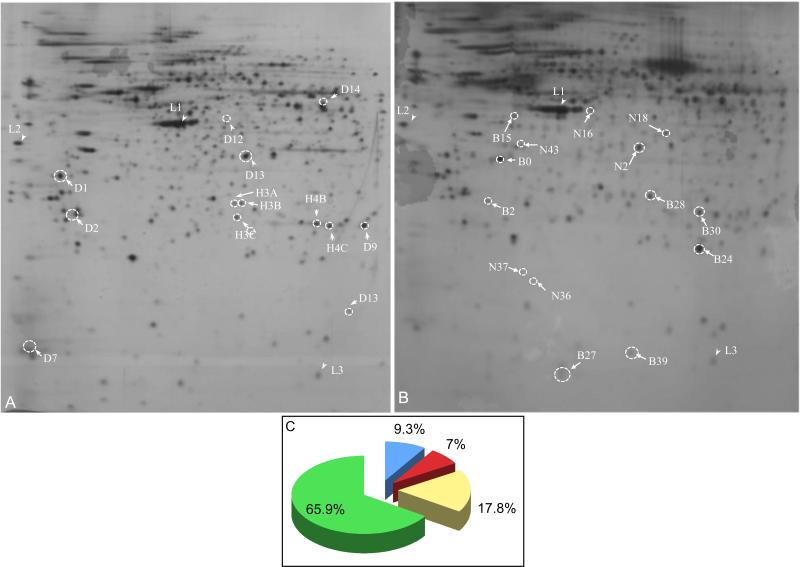

Silver stained gels revealed 603 protein spots in E15 (Fig. 1A), and 487 spots in P8 ovary samples (Fig. 1B). Only specific protein spots were indicated on digitized gray-scale images to maintain the clarity. The relatively dark background of silver stained gels masked faint protein spots; hence, dotted white circles mark their areas. Many proteins were differentially expressed between E15 and P8 ovaries. Compared to E15 ovaries, 32 protein spots were found to be upregulated (prefix B), 42 protein spots were newly (prefix N) expressed and 81 protein spots were downregulated (prefix D) in P8 ovaries. Nine protein spots, which remained unchanged (prefix H), were used as spatial reference points for in silico analysis. Spots L1 through L3 were used as internal markers for alignment, but were not analyzed. Further analysis indicated that 9.3% protein spots were new, whereas 7% protein spots were upregulated and 17.8% protein spots were downregulated in P8 ovaries compared to E15 ovaries (Fig. 1C). 65.9% protein spots remained unchanged irrespective of ovarian developmental (Fig. 1C).

Fig1.

Images of silver-stained analytical 2D protein gels from (A) E15 and (B) P8 ovaries. The prefix D indicates downregulated protein spots, prefix B indicates upregulated protein spots, prefix N indicates newly appeared protein spots, and prefix H indicates unchanged protein spots. Broken white circles highlight the area of the protein spots, some of which are intense while other are faint. These gel images were used as templates to retrieve protein spots from SyproRuby stained preparative gels. (C) The percentage of protein spots in various categories. L, landmarks used for gel alignment.

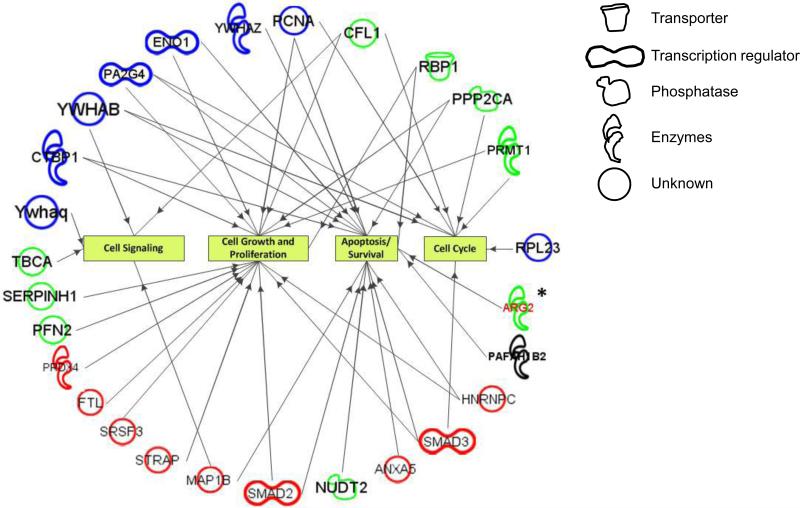

For the sake of brevity, only selected protein spots were analyzed by ion trap mass spectrometry. The results of mass spectrometric analysis and protein ID# were presented in Tables 1-2. Based on the signal intensity, some of the selected spots were identified with high confidence to contain more than one protein. Proteome database revealed that identified proteins belonged to signal transduction, cell growth and proliferation, cell cycle and apoptosis/survival (Fig. 2); however, no specific role could be determined for some proteins. Further, some of the proteins were also involved in transcriptional regulation of gene expression. The characteristics of some of the identified proteins could be determined from the mouse proteome database (Fig. 2).

Table 1.

Proteins, which are newly expressed or downregulated in P8 ovaries compared to E15 ovaries. Only selected spots with their corresponding ID# are furnished. Some protein spots could potentially contain more than one protein as determined by the MS analysis with confidence.

| Spot ID | Protein name | ID# |

|---|---|---|

| N (New) 2 | 60S acidic ribosomal protein P0 | P14869 |

| N 2 | L-lactate dehydrogenase B chain | P42123 |

| N 2 | Transaldolase | Q9EQS0 |

| N 16 | Creatine kinase B type | QO4447 |

| N16 | Eukaryotic initiation factor 4A-II | P10630 |

| N16 | Interleukin enhancer binding factor 2 | QPCXY6 |

| N16 | Protein arginine N-methyltransferase | Q9JIF0 |

| N 16 | Eukaryotic translation initiation factor- subunit 3,4 | Q9Z1D1 |

| N16 | Serpin H1 precursor | P19324 |

| N 18 | Arginase 2 Mitochondrial precursor | O08701 |

| N18 | Uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase | P70697 |

| N 37 | Hippocalcin like protein 1 | P62748 |

| N37 | Thioredoxin domain containing protein 12 precursor | Q9CQU0 |

| N 37 | Bis(5'-nucleosyl)-tetraphosphatase [asymmetrical] | P56380 |

| N 37 | 7,8-dihydro-8-oxoguanine triphosphatase | P53369 |

| N 38 | Tubulin specific chaperone A | P48428 |

| N 38 | Retinol binding protein 1- cellular | Q00915 |

| N 39 | Profilin 2 | Q9JJV2 |

| N 40 | Cofilin 1 | P18760 |

| N 43 | Ubiquitin | P62989 |

| N 43 | Serine-threonine protein phosphatase 2A subunit α | P63330 |

| D (Down) 1 | PCNA | P17918 |

| D 2 | 14-3-3 protein beta/alpha (YwhaB) | P35213 |

| D 2 | 14-3-3 protein zeta/delta (YwhaZ) | p63101 |

| D 2 | 14-3-3 protein theta (Ywhaq) | P68254 |

| D 2 | Proteasome subunit α | Q9Z2U1 |

| D 7 | Myosin light chain peptide | Q64119 |

| D 7 | 60S ribosomal protein L23 (RPL23) | P62830 |

| D 9 | Triphosphate isomerase | P17751 |

| D 9 | Platelet activating factor acetylhydrolase | Q35263 |

| D12 | SH3-containing GRB2 like protein | Q62419 |

| D 13 | Deoxyuridine 5’-triphosphate nucleotidohydralase | P70583 |

| D 13 | Sperm equatorial protein segment 1 | A0JPP4 |

| D 14 | Alpha enolase (ENO 1) | P17182 |

| D 14 | Proliferation associated protein 2G4 (Pa2G4, Ebp1) | P50580 |

| D 14 | C-terminal binding protein 1 (CtBP1) | O88712 |

Table 2.

Proteins, which are upregulated or remain unaltered in P8 ovaries compared to E15 ovaries. Only selected spots with their corresponding ID# are furnished. Some protein spots could potentially contain more than one protein as determined by the MS analysis with confidence.

| Spot ID | Protein name | ID# |

|---|---|---|

| B (Up) 1 | Annexin A5 | P48036 |

| B 2 | Ubiquitin carboxyl terminal hydroxylase enzyme –L3 / L4 | Q9JKB1 |

| B 5 | Smad2 | Q62432 |

| B 5 | Smad3 | Q8BUN5 |

| B 15 | hnRNP C1/C2 | Q9Z204 |

| B 15 | Serine-threonine kinase receptor-associated protein | Q9Z1Z2 |

| B 15 | BTB/POZ domain-containing protein KCTD12 | Q6WVG3 |

| B 24 | Serine/ arginine splicing factor- srp20 | P84104 |

| B 24 | Ferritin light chain 2/ 1 | P49945 |

| B 26 | Cytochrome C oxidase 5B- Mitochondrial precursor | P12075 |

| B 27 | Microtubule associated protein 1B | P15205 |

| B 28 | ER protein ERp29 precursor | P52555 |

| B 28 | Guanidinoacetate-N-methyltransferase | P10868 |

| B 28 | Peroxiredoxin-4 | O08807 |

| B 43 | Enolase Uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase | P70697 |

| B 43 | Arginase-2-mitochondrial precursor | O08691 |

| H (Unchanged) 3A | Peroxiredoxin 6 | Q35244 |

| H3B | Platelet activating factor acetylhydrolase | 035264 |

| H3C | Proteasome activator complex subunit 1 | P97371 |

| H4B | Proteasome subunit beta | P97371 |

| H4C | Glutathione S transferase | P48774 |

Fig. 2.

Integrated Pathways Analysis of proteins upregulated, downregulated or newly expressed in P8 hamster ovaries with respect to E15 ovaries. The analysis was done using protein ID# presented in Tables 1 and 2. The figure indicates the potential functions of identified proteins, including two candidate proteins selected for biological evaluation. Blue represents downregulated proteins, red represents up regulated protein, and green represents newly expressed proteins while black represents unchanged proteins. The structural symbols reflect their potential characteristics.

Validation of two candidate proteins involved in growth factor signaling, cell proliferation and transcriptional regulation

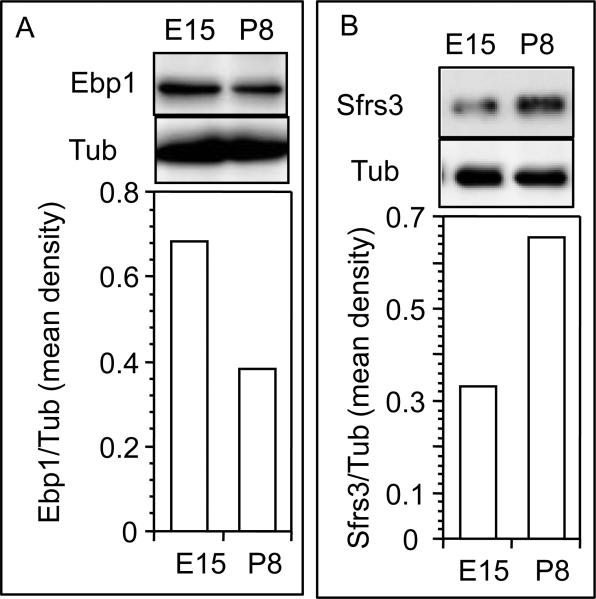

The Mass-spectrometry data for the downregulated Ebp1 and upregulated Sfrs3 in P8 ovaries were verified by immunoblotting and immunofluorescence analysis. Although Ebp1 expression was mostly localized in the nucleus, low intensity immunosignal was visible in the cytoplasmic portion of somatic cells (Fig. 3A). Whether the discrete punctate immunosignal in the nucleus of the oocytes and somatic cells reflected chromosomal association (Fig. 3A) needed to be verified in future studies. In E15 ovaries, the oocytes in the clusters (OC) expressed modest levels of EBP1 compared to the surrounding somatic cells (Figs. 3A and E). The intensity of EBP1 immunosignal, in general, decreased considerably primarily in the somatic cells by P8 (Figs. 3B and E). Further, the punctate nuclear localization also diminished considerably (Fig. 3B). Consistent with its transcription regulatory role in cells, Sfrs3 expression was restricted in the nuclei of all cells (Figs. 3C and D). Relatively low expression of Sfrs3 protein was visible in the nuclei of the oocytes in the clusters (OC) as well as of the somatic cells surrounding the oocyte clusters (Figs. 2C and F). A few somatic cells had more intense immunosignal than the other (Fig. 3C). Sfrs3 immunosignal increased markedly on P8 both in the oocytes (O) and in early granulosa cells (GC) of primordial follicles (S0), but the expression levels remained unchanged in the somatic cells (S) located elsewhere (Figs. 3D and F). Very few oocytes in E15 ovaries expressed modest level of MVH (Fig. 3C); however, MVH expression increased markedly in the oocytes of P8 ovaries (Fig. 3D), suggesting that MVH expression in the hamster oocytes reflected oocyte maturation in parallel with follicular development (Wang and Roy, 2010). Western blot analysis confirmed the immunofluorescence findings for both Ebp1 and Sfrs3 (Figs. 4A and B).

Fig. 3.

Immunofluorescence localization of (A and B) Ebp1, and (C and D) Sfrs3 in (A and C) E15 and (B and D) P8 hamster ovaries. For A and B, green color represents Ebp1 while red color indicates nuclear staining. Note punctate nuclear staining. For C and D, green color represents Sfrs3, red color represents MVH and blue color represents nuclei. Bar graphs showing mean fluorescence density per pixel for (E) Ebp1 and (F) Sfrs3. Statistical analysis was done between oocytes or somatic cells and granulosa cells. Bars with a different letter are significantly different from each other. GC, granulosa cells, OC, oocyte clusters, S, somatic cells, O, oocytes. Bar = 10 μm.

Fig 4.

Representative Western blot images of (A) Ebp1, and (B) Sfrs3 protein expression in E15 and P8 hamster ovaries. Tubulin (Tub) levels were determined to verify the specificity and protein loading. The mean signal intensity from two replicates is presented in corresponding bar graphs.

Discussion

The study shows for the first time that primordial follicular morphogenesis corresponds to unique changes in ovarian proteome levels. The results show that 2D gel electrophoresis combined with state-of-the art Mass spectrometry and bioinformatics is capable of identifying proteins potentially affecting the formation of primordial follicles. Proteomics approach has its advantage because it identifies proteins and assures the presence of cognate mRNA in the tissue. The differential levels of many proteins at the time of primordial follicle formation suggest the possibility that the oocyte-somatic cells communication and differentiation of somatic cells into early granulosa cells may be directly or indirectly regulated by at least some of the proteins. Some of the proteins may reflect the functions of differentiated cells. This contention is further supported by the putative cellular functions of some of these proteins as revealed by the pathway analysis. The present proteome data cannot be directly compared to the DNA microarray data for postnatal rat (Kezele et al., 2004) and fetal human (Fowler et al., 2009) ovaries before and after the formation of primordial follicles because (1) microarray does not reveal all the gene transcripts, (2) it is unclear whether all mRNA are transcribed into proteins, and (3) the number of proteins in the mouse proteome database is less than the number of genes present on a microarray slide. Further, whereas some upregulated genes have been identified in P4 rat and fetal human ovaries containing primordial follicles (Fowler et al., 2009,Kezele et al., 2004), significant dissimilarities exist. Nevertheless, increased CYP19 activity and mRNA level in P8 hamster ovary (Wang and Roy, 2007) corroborate increased levels of CYP19 transcript in P4 rat (Kezele et al., 2004) and fetal human (Fowler et al., 2009) ovaries containing primordial follicles. Besides, upregulation of genes regulating redox mechanism, glucose metabolism and cell-to cell communication in the rat ovary containing primordial follicles (Kezele et al., 2004) corroborate well with the proteome data for P8 hamster ovaries. The increase in peroxiredoxin-4 and thioredoxin in P8 hamster ovaries correlates well with 8.66-fold increase in glutathione peroxidase gene in P4 rat ovary during primordial to primary follicle transition (Kezele et al., 2004) suggesting the involvement of redox mechanism during follicular morphogenesis. In contrast to the P4 rat ovary, retinol-binding protein-1 increases in P8 hamster ovaries. Retinol-binding protein has been suggested to play an important role in testis-morphogenesis in the rat (Zheng, Bucco, Schmitt et al., 1996).

The down regulation of proteins with the formation of primordial follicles suggests that these proteins belong to undifferentiated cells in the E15 ovary. Some of the proteins may suppress gene transcription related to cell proliferation and/or differentiation; hence, their expression must be downregulated by P8 to allow somatic cell proliferation and differentiation to occur. One such protein is the C-terminal binding protein 1 (CtBP1). Decrease in CtBP1 has also been reported for the rat ovary containing primordial follicle (Kezele et al., 2004). CtBP1 is a transcriptional co-repressor (Hildebrand and Soriano, 2002) and has been shown to affect developmental pathways regulated by Wnt and BMP (Brannon, Brown, Bates et al., 1999,Izutsu, Kurokawa, Imai et al., 2001) and also cell-to-cell adhesion and apoptosis (Grooteclaes, Deveraux, Hildebrand et al., 2003,Grooteclaes and Frisch, 2000). Cell-to-cell adhesion is a critical requirement for the granulosa cells and oocyte assembly (Wang and Roy, 2010). Similarly, apoptosis is an important process for organ morphogenesis, and apoptosis of the oocytes in the oocyte-nest is a prerequisite for oocyte and granulosa cell assembly (Pepling, 2006). CtBP1 knockout in mouse fibroblasts upregulates proapoptotic genes (Zhang, Yoshimatsu, Hildebrand et al., 2003).

New proteins on P8 reflect the functions of differentiated phenotype of ovarian somatic cells, including newly formed granulosa cells. For example, profilin, a non-muscle actin binding protein (Stossel, Chaponnier, Ezzell et al., 1985), plays an important regulatory role in EGF-receptor mediated activation of Phospholipase C-γ1, which produces Inositol-tris phosphate (IP3) and diaceylglycerol (DAG) (Goldschmidt-Clermont, Kim, Machesky et al., 1991). Both IP3 and DAG are important signaling molecules in ovarian cells. Lower expression of profilin in the drosophila ovary has been suggested to lead female sterility (Cooley, Verheyen and Ayers, 1992). The expression of profilin may also suggest active cytoskeleton remodeling during follicular morphogenesis. The appearance of ubiquitin strongly correlates with increased cellular activities. Similarly, downregulation of 14-3-3 in P8 ovaries correlates with increased cell proliferation characteristics of a developing organ. 14-3-3 family of proteins serve a variety of functions in cells (van Hemert, Steensma and van Heusden, 2001). 14-3-3σ inhibits cdk2 activity (Laronga, Yang, Neal et al., 2000) and high level is associated with arrests in G1/S and G2/M transition (Hermeking, Lengauer, Polyak et al., 1997). The decrease in PCNA levels in P8 versus E15 ovaries may be due to its varied expression in proliferating cells. Because the threshold of PCNA levels necessary for cells to enter the ‘S’ phase is not known, the finding does not rule out cell proliferation in P8 ovaries. In fact, our preliminary study suggests considerable BrdU incorporation in 8-day cultured hamster ovaries (unpublished observation). Future studies on temporal incorporation of BrdU in ovarian somatic cells in vitro will provide information about cell proliferation. The upregulation of annexin V, a marker for apoptosis (Gerber, Bohne, Rasch et al., 2000), in P8 ovaries may suggest the oocyte loss associated with primordial follicle assembly (Pepling, 2006). Similarly, the upregulation of microtubule associated protein indicates possible cytoskeletal remodeling, which is essential for ovarian morphogenesis with relation to primordial follicle formation. Upregulation of Smad2 and Smad3, which are transcriptional regulators of genes involved in cell differentiation and organogenesis (Wrana, 2000) in P8 ovaries suggests that TGFB family of ligands regulate postnatal ovary development in the hamster. Ovarian somatic cells expressing TGFB2 have been shown to be differentiated into pregranulosa cells of primordial follicles (Roy and Hughes, 1994). DNA microarray analysis of P4 rat ovary containing primordial follicles confirms an increase in Smad2 gene transcript (Kezele et al., 2004). Similarly, upregulation of serine-threonine kinase receptor-associated protein and the appearance of serine-threonine protein phosphatase 2a in P8 suggest increased receptor activities linked to cell proliferation and differentiation (Massagué and Weis-Garcia, 1996). Studies are in progress to determine the temporal expression and regulation thereof of specific proteins with relation to primordial follicle formation.

The unique expression of Ebp1 and Sfrs3 with respect to primordial follicle formation suggests that these proteins may play an important role in somatic cell-oocyte communication leading to the formation of early granulosa cells. Ebp1 is a member of the Pa2G4 family of proliferation-regulated protein and it binds with ErbB3 (Yoo, Wang, Rishi et al., 2000). Ebp1 acts as a transcriptional repressor of E2f1 (Lessor, Yoo, Xia et al., 2000), and it complexes with Rb, Sin3A (Zhang, Akinmade and Hamburger, 2005) and histone deacetylase 2 (HDAC2) on E2f1 regulated promoters (Zhang et al., 2005). Ebp1 phosphorylation and its binding to E2f depend upon ErbB3 activation by heregulin (Zhang and Hamburger, 2004). The nuclear location of Ebp1 in ovarian cells corroborates previous findings that overexpression of Ebp1 in human fibroblast cells inhibits cell proliferation and the effect is associated with the nuclear location of Ebp1 (Squatrito, Mancino, Donzelli et al., 2004). The p48 isoform of Ebp1, which is present in the hamster ovary, resides in the cell cytoplasm as well as in the nucleus (Okada, Jang and Ye, 2007). Ebp1 has been shown to participate in cell survival by complexing with active nuclear Akt (Ahn, Liu, Liu et al., 2006). Therefore, it is logical to postulate that the decreased level but not a complete absence of Ebp1, in somatic cells by P8 is necessary for somatic cell proliferation as well as cell survival. Interestingly, deletion of Ebp1 gene in mice resulted in a significant decrease in body size; however, the gene deletion is associated with an overall decrease in IGF-1 and increase in cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors 2A transcripts (Zhang, Lu, Zhou et al., 2008). Further, although Ebp1-/- females are fertile, they produce significantly small litters (Zhang et al., 2008). The decline in Ebp1 protein on P8 may occur due to ubiquitination, which fits well with the appearance of ubiquitin on P8. In a preliminary study, siRNA knockdown of Ebp1 in vitro seems to block oocyte-nest breakdown and primordial follicle formation (data not shown). Future studies will offer more specific information.

In contrast to Ebp1, increased expression of Sfrs3 (a serine-arginine splicing factor-3; previously SRp20) (Ayane, Preuss, Kohler et al., 1991), in the oocytes and granulosa cells of primordial follicles on P8 suggests strongly that this protein may play an important role in oocyte-somatic cell communication that involves cellular differentiation into granulosa cells and assembly with the oocytes. RNA-binding proteins, such as Sfrs3, play an important role in RNA processing and development (Bandziulis, Swanson and Dreyfuss, 1989). Sfrs3 affects alternate splicing; hence, plays an important role in transcript regulation (Jia, Li, McCoy et al., 2010,Jumaa, Guenet and Nielsen, 1997), but it also regulates transcription and protein translation (Jia et al., 2010). Cre-lox-mediated deletion of Sfrs3 in mice leads to a complete failure of blastocyst formation (Jumaa, Wei and Nielsen, 1999). High expression of Sfrs3 is reported in various highly proliferative cancer cells (Jia et al., 2010). Therefore, it is logical to speculate that increased expression of Sfrs3 in the granulosa cells and the enclosed oocyte of primordial follicles on P8 may reflect active transcription and translation of many genes, which are expected to occur during primordial follicle morphogenesis. Future studies will reveal the specific role of Sfrs3 in primordial follicle formation.

In summary, the study provides the first evidence of a differential expression of ovarian proteins with respect to primordial follicle formation. The unique expression pattern of Ebp1 and Sfrs3 highlights important cellular changes, which are expected during such a major morphogenetic process. Studies are in progress to understand the specific role of these two candidate proteins and their regulation thereof in somatic cell differentiation and primordial folliculogenesis.

Expression of novel proteins coincides with primordial follicle formation

The expression of Ebp1, a growth factor signaling regulator decreases

The expression of Sfrs3, a transcriptional regulator increases

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a Grant (R01-HD38468) from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, NIH to S. K. Roy. The authors would like to thank the National Jewish Health Mass spectrometry facility for analysis of the samples, and department of Bioinformatics for Integrated Pathway Analysis of identified proteins. Funding for the ion trap mass spectrometer was provided by NCRR S10RR023703.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ahn JY, Liu X, Liu Z, Pereira L, Cheng D, Peng J, Wade PA, Hamburger AW, Ye K. Nuclear Akt associates with PKC-phosphorylated Ebp1, preventing DNA fragmentation by inhibition of caspase-activated DNase. EMBO J. 2006;25:2083–95. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ayane M, Preuss U, Kohler G, Nielsen PJ. A differentially expressed murine RNA encoding a protein with similarities to two types of nucleic acid binding motifs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:1273–8. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.6.1273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bandziulis RJ, Swanson MS, Dreyfuss G. RNA-binding proteins as developmental regulators. Genes Dev. 1989;3:431–7. doi: 10.1101/gad.3.4.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brannon M, Brown JD, Bates R, Kimelman D, Moon RT. XCtBP is a XTcf-3 co-repressor with roles throughout Xenopus development. Development. 1999;126:3159–70. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.14.3159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Byskov AG. Differentiation of mammalian embryonic gonad. Physiol Rev. 1986;66:71–117. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1986.66.1.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cooley L, Verheyen E, Ayers K. chickadee encodes a profilin required for intercellular cytoplasm transport during Drosophila oogenesis. Cell. 1992;69:173–84. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90128-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dong J, Albertini DF, Nishimori K, Kumar TR, Lu N, Matzuk MM. Growth differentiation factor-9 is required during early ovarian folliculogenesis. Nature. 1996;383:531–535. doi: 10.1038/383531a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fowler PA, Flannigan S, Mathers A, Gillanders K, Lea RG, Wood MJ, Maheshwari A, Bhattacharya S, Collie-Duguid ES, Baker PJ, Monteiro A, O'Shaughnessy PJ. Gene expression analysis of human fetal ovarian primordial follicle formation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:1427–35. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-2619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gerber A, Bohne M, Rasch J, Struy H, Ansorge S, Gollnick H. Investigation of annexin V binding to lymphocytes after extracorporeal photoimmunotherapy as an early marker of apoptosis. Dermatology. 2000;201:111–7. doi: 10.1159/000018472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goldschmidt-Clermont PJ, Kim JW, Machesky LM, Rhee SG, Pollard TD. Regulation of phospholipase C -gamma 1 by profilin and tyrosine phosphorylation. Science. 1991;251:1231–1233. doi: 10.1126/science.1848725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grooteclaes M, Deveraux Q, Hildebrand J, Zhang Q, Goodman RH, Frisch SM. C-terminal-binding protein corepresses epithelial and proapoptotic gene expression programs. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100:4568–73. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0830998100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grooteclaes ML, Frisch SM. Evidence for a function of CtBP in epithelial gene regulation and anoikis. Oncogene. 2000;19:3823–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hashimoto O, Moore KR, Shimasaki S. Posttranslational processing of mouse and human BMP-15: Potential implication in the determination of ovulation quota. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:5426–5431. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409533102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hermeking H, Lengauer C, Polyak K, He TC, Zhang L, Thiagalingam S, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. 14-3-3 sigma is a p53-regulated inhibitor of G2/M progression. Mol Cell. 1997;1:3–11. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hildebrand JD, Soriano P. Overlapping and unique roles for C-terminal binding protein 1 (CtBP1) and CtBP2 during mouse development. Molecular and cellular biology. 2002;22:5296–307. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.15.5296-5307.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Izutsu K, Kurokawa M, Imai Y, Maki K, Mitani K, Hirai H. The corepressor CtBP interacts with Evi-1 to repress transforming growth factor beta signaling. Blood. 2001;97:2815–22. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.9.2815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jia R, Li C, McCoy JP, Deng CX, Zheng ZM. SRp20 is a proto-oncogene critical for cell proliferation and tumor induction and maintenance. Int J Biol Sci. 2010;6:806–26. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.6.806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jumaa H, Guenet JL, Nielsen PJ. Regulated expression and RNA processing of transcripts from the Srp20 splicing factor gene during the cell cycle. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:3116–24. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.6.3116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jumaa H, Wei G, Nielsen PJ. Blastocyst formation is blocked in mouse embryos lacking the splicing factor SRp20. Curr Biol. 1999;9:899–902. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80394-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kezele PR, Ague JM, Nilsson E, Skinner MK. Alterations in the Ovarian Transcriptome During Primordial Follicle Assembly and Development. Biol Reprod. 2004;72:241–255. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.104.032060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Laronga C, Yang HY, Neal C, Lee MH. Association of the cyclin-dependent kinases and 14-3-3 sigma negatively regulates cell cycle progression. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:23106–12. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M905616199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lessor TJ, Yoo JY, Xia X, Woodford N, Hamburger AW. Ectopic expression of the ErbB-3 binding protein ebp1 inhibits growth and induces differentiation of human breast cancer cell lines. J Cell Physiol. 2000;183:321–9. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(200006)183:3<321::AID-JCP4>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lyall RM, Zilberstein A, Gazit A, Gilon C, Levitzki A, Schlessinger J. Tyrphostins inhibit epidermal growth factor (EGF)-receptor tyrosine kinase activity in living cells and EGF-stimulated cell proliferation. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:14503–14509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Massagué J, Weis-Garcia F. Serine/threonine kinase receptors: Mediators of transforming growth factor beta family signals. Cancer Surv. 1996;27:41–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Okada M, Jang SW, Ye K. Ebp1 association with nucleophosmin/B23 is essential for regulating cell proliferation and suppressing apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:36744–54. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706169200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pepling ME. From primordial germ cell to primordial follicle: mammalian female germ cell development. Genesis. 2006;44:622–32. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roy SK, Albee L. Requirement for follicle-stimulating hormone action in the formation of primordial follicles during perinatal ovarian development in the hamster. Endocrinology. 2000;141:4449–4456. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.12.7805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roy SK, Hughes J. Ontogeny of granulosa cells in the ovary: Lineage-specific expression of transforming growth factor β2 and transforming growth factor β1. Biol.Reprod. 1994;51:821–830. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod51.5.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roy SK, Kole AR. Transforming growth factor- receptor type II expression in the hamster ovary:Cellular site(s), biochemical properties, and hormonal regulation. Endocrinology. 1995;136:4610–4620. doi: 10.1210/endo.136.10.7664681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Skinner MK. Regulation of primordial follicle assembly and development. Hum Reprod Update. 2005;11:461–71. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmi020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Squatrito M, Mancino M, Donzelli M, Areces LB, Draetta GF. EBP1 is a nucleolar growth-regulating protein that is part of pre-ribosomal ribonucleoprotein complexes. Oncogene. 2004;23:4454–65. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stossel TP, Chaponnier C, Ezzell RM, Hartwig JH, Janmey PA, Kwiatkowski DJ, Lind SE, Smith DB, Southwick FS, Yin HL, et al. Nonmuscle actin-binding proteins. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1985;1:353–402. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.01.110185.002033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van den Hurk R, Zhao J. Formation of mammalian oocytes and their growth, differentiation and maturation within ovarian follicles. Theriogenology. 2005;63:1717–51. doi: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2004.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van Hemert MJ, Steensma HY, van Heusden GP. 14-3-3 proteins: key regulators of cell division, signalling and apoptosis. Bioessays. 2001;23:936–46. doi: 10.1002/bies.1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang C, Roy SK. Expression of growth differentiation factor 9 in the oocytes is essential for the development of primordial follicles in the hamster ovary. Endocrinology. 2006;147:1725–34. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang C, Roy SK. Development of Primordial Follicles in the Hamster: Role of Estradiol-17{beta} Endocrinology. 2007;148:1707–16. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang C, Roy SK. Expression of bone morphogenetic protein receptor (BMPR) during perinatal ovary development and primordial follicle formation in the hamster: possible regulation by FSH. Endocrinology. 2009;150:1886–96. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang C, Roy SK. Expression of E-cadherin and N-cadherin in perinatal hamster ovary: possible involvement in primordial follicle formation and regulation by follicle-stimulating hormone. Endocrinology. 2010;151:2319–30. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-1489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wrana JL. Regulation of Smad activity. Cell. 2000;100:189–192. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81556-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang P, Wang J, Shen Y, Roy SK. Developmental expression of estrogen receptor (ER) alpha and ERbeta in the hamster ovary: regulation by follicle-stimulating hormone. Endocrinology. 2004;145:5757–66. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-0779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yoo JY, Wang XW, Rishi AK, Lessor T, Xia XM, Gustafson TA, Hamburger AW. Interaction of the PA2G4 (EBP1) protein with ErbB-3 and regulation of this binding by heregulin. Br J Cancer. 2000;82:683–90. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.1999.0981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang Q, Yoshimatsu Y, Hildebrand J, Frisch SM, Goodman RH. Homeodomain interacting protein kinase 2 promotes apoptosis by downregulating the transcriptional corepressor CtBP. Cell. 2003;115:177–86. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00802-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang Y, Akinmade D, Hamburger AW. The ErbB3 binding protein Ebp1 interacts with Sin3A to repress E2F1 and AR-mediated transcription. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:6024–33. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang Y, Hamburger AW. Heregulin regulates the ability of the ErbB3-binding protein Ebp1 to bind E2F promoter elements and repress E2F-mediated transcription. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:26126–33. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M314305200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang Y, Lu Y, Zhou H, Lee M, Liu Z, Hassel BA, Hamburger AW. Alterations in cell growth and signaling in ErbB3 binding protein-1 (Ebp1) deficient mice. BMC Cell Biol. 2008;9:69. doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-9-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zheng WL, Bucco RA, Schmitt MC, Wardlaw SA, Ong DE. Localization of cellular retinoic acid-binding protein (CRABP) II and CRABP in developing rat testis. Endocrinology. 1996;137:5028–35. doi: 10.1210/endo.137.11.8895377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]