Abstract

During early embryonic development, the retinoic acid signaling pathway coordinates with other signaling pathways to regulate body axis patterning and organogenesis. The production of retinoic acid requires two enzymatic reactions, the first of which is the oxidization of vitamin A (all-trans-retinol) to all-trans-retinal, mediated in part by the short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase. Through DNA microarrays, we have identified a gene in Xenopus laevis, which shares a high sequence similarity to human short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase member 3. We therefore annotated the gene Xenopus short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase 3 (dhrs3). Expression of dhrs3 was detected by whole mount in situ hybridization in the dorsal blastopore lip and axial mesoderm region in gastrula embryos. During neurulation, dhrs3 transcripts were found in the notochord and neural ectoderm. Strong expression of dhrs3 was mainly detected in the brain, spinal cord, and pronephros region in tailbud and tadpole stages. Temporal expression tested by RT-PCR indicated that dhrs3 was activated at the onset of gastrulation, and remained highly expressed at later stages of embryonic development. The distinct and highly regulated spatial and temporal expression of dhrs3 highlights the complexity of retinoic acid regulation.

Keywords: dhrs3, Retinoic Acid, Xenopus

Early embryonic development is regulated by coordination of multiple signaling pathways that include Wnt, TGF-β, FGF, as well as retinoic acid (RA) signaling. Among them, the retinoic acid (RA) and RA metabolites play essential roles for germ layer differentiation and the body axis formation (Chen et al., 2001; Hollemann et al., 1998; Sirbu and Duester, 2006; Strate et al., 2009; Vermot and Pourquie, 2005). In addition, the RA signaling pathway has been implicated in organogenesis of the heart (Mic et al., 2002; Niederreither et al., 2001; Ryckebusch et al., 2008), lung (Chen et al., 2007; Esteban-Pretel et al., 2009), kidney (Cartry et al., 2006; Wingert et al., 2007) and pancreas (Chen et al., 2004). Deficiencies in the metabolism of retinoids lead to severe defects of vertebrate embryonic development (Abu-Abed et al., 2001; Mendelsohn et al., 1994; Sandell et al., 2007). RA is synthesized from Vitamin A (all-trans-retinol) via two enzymatic steps. In the first step, all-trans-retinol is oxidized to all-trans-retinal either by the short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase (SDR) or medium-chain dehydrogenase/reductase (MDR). The second step is to convert all-trans-retinal to RA catalyzed by the retinaldehyde dehydrogenases that include RALDH1, RALDH2, and RALDH3. Retinoic acid directly regulates transcription via interaction with the heterodimer of retinoic acid receptor (RAR) and retinoid receptor (RXR) (Gronemeyer et al., 2004). In this study, we identified a new member of short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase in Xenopus laevis and investigated its spatial and temporal expression during the embryonic development.

Results and Discussion

In an attempt to study genome-wide regional gene expression during embryogenesis of Xenopus laevis, we have investigated the spatial differences in gene expression in early gastrula embryos (Stage 10) by using DNA microarray. A number of novel genes have been identified (Tanegashima et al., 2008; Zhao et al., 2008) including one gene showing distinct dorsal expression at the onset of gastrulation, which encodes a protein with a sequence similar to the human short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase. This gene was therefore designated Xenopus short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase 3 (dhrs3). The full cDNA sequence has been deposited to GeneBank, and the accession numbers is FJ607948 (Fig. 1A).

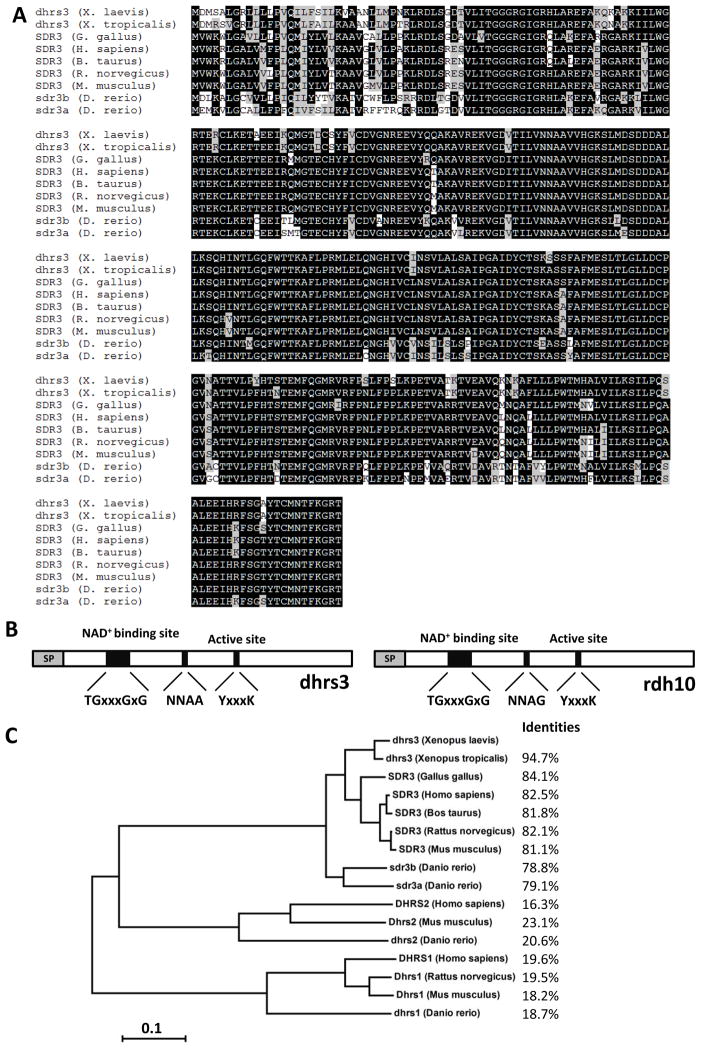

Fig. 1.

Characterization of the Xenopus dhrs3 gene. (A) Protein sequence comparisons. Alignment of dhrs3 from Xenopus laevis, Xenopus tropicalis, chicken, human, cow, rat, mouse and zebrafish, respectiely. Identical amino acids are shaded in black and similar amino acids are shaded in grey. (B) Schematic drawing of the protein structure of dhrs3 and Xenopus rdh10. The conserved sequences, TGxxxGxG for the co-factor binding, NNAA and YxxxK for the active catalytic site, are indicated and the x represents any amino acid residue. SP, signal peptide. (C) Dendrogram tree of the dhrs1, 2 and 3 families. The identity of amino acid sequences between dhrs3 and its orthologs in other species is indicated as percentage.

dhrs3 encodes an open reading frame of 302 amino acids, with a predicated co-factor binding site (TGxxxGxG) and catalytic sites (YxxxK) (Fig. 1B), both of which are characteristic of the short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase family (Persson et al., 2003). When compared with Xenopus retinol dehydrogenase 10 (rdh10), another member of short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase family, their functional domains were similar except rdh10 carries a co-factor binding site NNAG, instead of NNAA as found in dhrs3. Similar to rdh10, Xenopus dhrs3 have a signal peptide at the amino terminus, as predicted by SignalP3.0 (Bendtsen et al., 2004) and Signal-3L (Shen and Chou, 2007). We created a phylogenetic tree showing the evolutionary relationship between dhrs3 and its orthologs in other vertebrates (Fig. 1C). The dhrs3 protein is 94.7% identical to its ortholog in Xenopus tropicalis (NM_001008431), 84.1% to chicken (XM_417636), 82.5% to human (BC002730), 81.8% to cow (NP_776605.2), 82.1% to rat (EF125189), 81.1% to mouse (NM_011303), 78.8% to zebrafish sdr3b (BC083252), and 79.1% to zebrafish sdr3a (BC078383) respectively. The high identity of amino acid sequences among short-chain dehydrogenase/reductases 3 from different species suggests an evolutionarily conserved role for dhrs3 in the embryonic development. We have also compared the sequence similarities between Xenopus dhrs3 with dhrs1 and dhrs2 from other species. Their evolutionary relationship was showed in figure 1C.

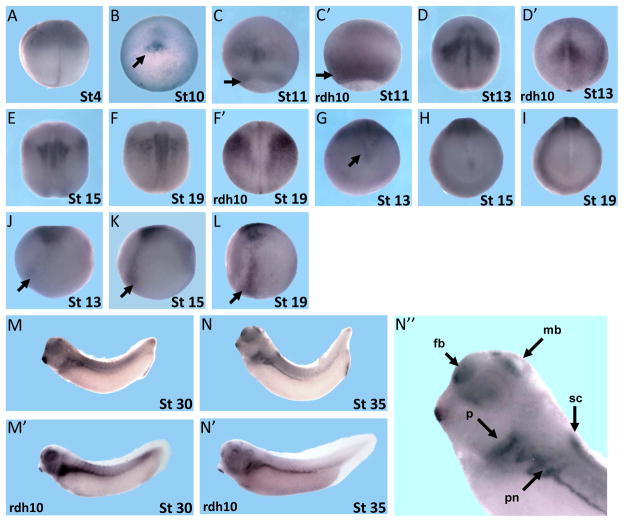

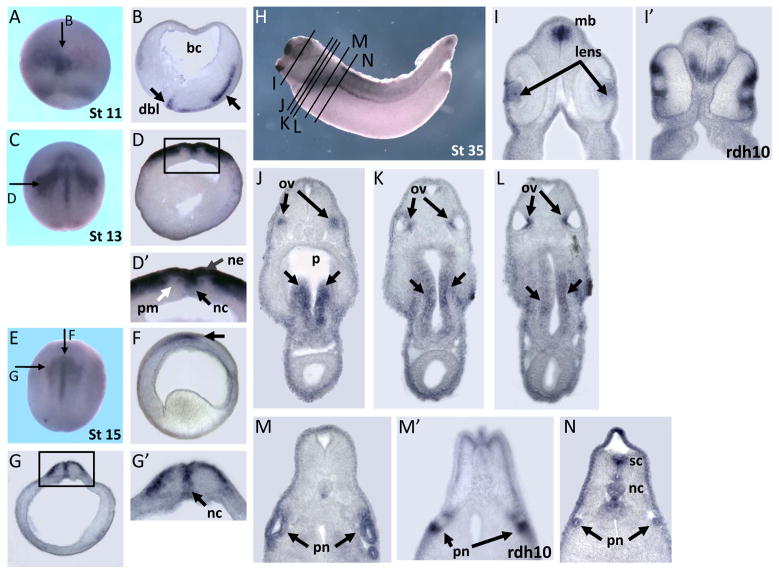

The spatial expression pattern of dhrs3 was examined by whole-mount in situ hybridization. While signals were observed at the animal pole, no obvious expression was detected in the vegetal hemisphere before midblastula transition (Fig. 2A). At the onset of gastrulation (stage 10), dhrs3 expression became intensified in the dorsal blastopore lip (Fig. 2B) and continued to expand in the prospective neural plate. With advancing gastrulation, dhrs3 expression was detected at the dorsal midline, appearing in two bilateral domains on the dorsal side, which progressively decreased anteriorly (Fig. 2C, 3A). Sections from stage 11 embryos confirmed that the expression of dhrs3 was localized in the dorsal blastopore lip and axial mesoderm (Fig. 3B). In addition, the dhrs3 signals formed a circumblastoporal ring (Fig. 2C, arrow), which is reminiscent of Xcyp26a expression pattern (Hollemann et al., 1998). This expression pattern was similar to that of rdh10, which was also found surrounding the yolk plug (Fig. 2C′, arrow).

Fig. 2.

Spatial expression pattern of dhrs3. Whole mount in situ hybridization was employed to examine the spatial expression of dhrs3 at different developmental stages as indicated. (A) Lateral view of a four-cell stage embryo. (B–F′) Dorsal view of early stage embryos. dhrs3 transcripts were localized in the dorsal blastopore lip and the ridge of neural fold. The expression of rdh10 in stage 11, 13 and 19 were showed in C′, D′ and F′ for comparison. (G–I) Frontal view of stage 13, 15, 19 embryos, which showed that dhrs3 expression was absent in the head, but present in the posterior edge of the up-folding neural tube. (J–L) Lateral view of stage 13, 15, 19 embryos, showing dhrs3 expression in ventral bilateral regions (arrow). (M–N′) Lateral views of tailbud and tadpole stage embryos, showing the expression pattern of dhrs3 and rdh10. The anterior region of a stage 35 embryo showing dhrs3 expression was magnified in (N″). dhrs3 expression was detected in the forebrain, midbrain, pharynx, spinal cord and pronephros (arrow). In lateral views (J–N″), anterior is to the left. Abbreviation: fb, forebrain; mb, midbrain; p, pharynx; sc, spinal cord; pn, pronephros.

Fig. 3.

Transverse and longitudinal sections of embryos showing dhrs3 expression. (A,B) Stage 11 embryo (A) was sectioned showing the expression domain in dorsal blastopore lip and axial mesoderm (B). (C–D′) Transverse section from a stage 13 embryo (C), indicating the expression in notochord and neuroectoderm. The higher magnification of framed region (D) is shown in (D′). (E–G′) Longitudinal and transverse sections from a stage 15 embryo (E) indicated dhrs3 was expressed in notochord and neuroectoderm. (H–N) Transverse sections of a stage 35 embryo (H), illustrating the expression in the midbrain, lens, otic vesicles, ventral pharynx, gut, pronephros, dorsal spinal cord and notochord. Expression pattern of rdh10 was showed in I′ and M′. Abbreviation: bc, blastocoel; bpl, blastopore lip; ne, neuroepithelium; pm, paraxial mesoderm; nc, notochord; mb, midbrain; ov, otic vesicle; p, pharynx; pn, pronephros; sc, spinal cord.

In early neurula stages, signals were observed in the notochord, neural ectoderm, and paraxial mesoderm (Fig. 2D, 3C–F). With the progression of neurulation, the bilateral expression domains of dhrs3 in the neural plate gradually converged towards the midline, forming two signal strips extending posteriorly, corresponding to the dorsal ridge of the in-folding neural tube (Fig. 2D, E, F). Further, V-shape domain at the inner perimeter of the frontal neural groove also stains for dhrs3 (Fig. 2G, arrow). The anterior edge of neural plate, however, was devoid of discernible expression (Fig. 2G–I). rdh10, on the other hand, was not expressed in the dorsal midline (Fig. 2D′). A dorsal-to-ventral strip of dhrs3 signals was found in the paraxial mesoderm and dorsal notochord (Fig. 2E, F, J–L). dhrs3 is also expressed in the dorsal notochord (Fig. 3D and D′).

In tailbud and tadpole stages, dhrs3 was expressed in the head region that covered prosencephalon, mesencephalon, lens, and otic vesicle (Fig. 2M, N, 3I, J–L). The expression in otic vesicles was not visible from the exterior, but embryo sections showed that dhrs3 was expressed in the internal region of otic vesicles (Fig. 3J–L, upper arrow). dhrs3 was expressed in primary lens fibers and the lens epithelium (Fig. 3I). Interestingly, dhrs3 positive cells were only observed in the roof plate and the adjacent region of the mesencephalic ventricle (Fig. 3I). The expression of dhrs3 in the roof plate overlapped with that of rdh10. Abundant transcripts of rdh10 were also localized in the floor plate (Fig. 3I′), where dhrs3 was not expressed. Retinoic acid signalling in the neural tube was tightly regulated so that it is mostly localized in the interneuron region (Maden, 2006). The distinct expression of dhrs3 and rdh10 suggests that these two genes played a role in such regulation by adjusting the local level of retinoic acid. The expression of dhrs3 in spinal cord appeared only in a more posterior region, but not in the region immediately adjacent to the hindbrain (Fig. 2N″, 3H). Besides the central nervous system, distinct expression domains were also observed in the pronephros including pronephric tubule and pronephric duct (Fig. 2N). These expression domains were confirmed by embryo section (Fig. 3M). The expression in pronephros regions overlap strongly with that of rdh10 (Fig. 2M–N′, Fig. 3M, M′). dhrs3 expression was detected in the ventral but not dorsal pharynx (Fig. 3J), and expression was also detected in the following gut region, mainly in the medial part (Fig. 3K, L, middle arrow).

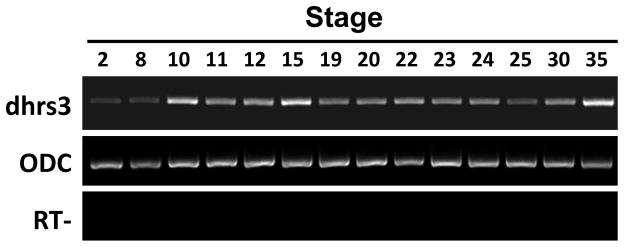

We examined the temporal expression pattern of dhrs3 by RT-PCR, using primers covering the 3′ UTR region of dhrs3. The results showed that dhrs3 is a maternal factor and is weakly expressed before gastrulation. dhrs3 was up-regulated from stage 10. Peak expression of dhrs3 was observed in stage 15, which was followed by a decline from stage 19 to stage 25, and an increase after stage 30 (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Temporal expression of dhrs3. dhrs3 expression in embryos of different developmental stages was examined by RT-PCR. A housekeeping gene ornithine decarboxylase (ODC) was used as the internal standard control. RT−, without reverse transcriptase.

Taken together, we have identified dhrs3 in Xenopus laevis and we illustrate the developmental expression pattern of this gene in Xenopus embryos. We suggest that dhrs3 is involved in RA metabolism, as some evidence indicates that human Dhrs3 is involved in RA synthesis (Haeseleer et al., 1998). We have also compared and contrasted the expression patterns of dhrs3 and rdh10 (Strate et al., 2009). dhrs3 was expressed in the dorsal midline in early neurula stage, where rdh10 was absent (Fig. 2D, D′). dhrs3 was expressed in the dorsal neural fold region in late neurula stages, and rdh10 was expressed in the bilateral region outside of dorsal neural fold (Fig. 2F, F′). dhrs3 was only expressed in the roof plate in midbrain in tailbud stage, while rdh10 was also expressed in the floor plate, and the adjacent region in ventral neural tube (Fig. 3I, I′). On the other hand, both dhrs3 and rdh10 expression can be found in the circumblastoporal ring in early gastrulation (Fig. 2C, C′) and the pronephros region in tailbud stages (Fig. 2N, N′, 3M, M′). These observations highlight the complexity of retinoic acid regulation. In order to fully elucidate the function of dhrs3, we attempt to carry out an enzymatic analysis to determine the substrate and co-factor specificities of the protein. The functional role of this enzyme in embryonic development will also be studied by gene knock-down and over-expression experiments. The action of dhrs3 on midbrain development was particularly interesting since it was localized only in the roof plate, while rdh10 was also localized in the floor plate. The relationship between these two enzymes should provide valuable information to the action of retinoid signaling on midbrain development. Further investigation of dhrs3 function during embryonic development will expand our understanding of the retinoic acid signaling pathway and shed light on the mechanism by which retinoic acid regulates embryonic development.

Materials and methods

Phylogenetic analysis

BLAST searches were performed on the NCBI website, using the blastx program with the non-redundant protein sequence database. Protein sequence alignment was done with BioEdit (http://www.mbio.ncsu.edu/BioEdit/bioedit.html). The dendrogram was constructed by using MEGA 4.0.2 (http://www.megasoftware.net) with the neighbor-joining method and p-distance model.

Whole-mount in situ hybridization and vibratome sectioning

Whole-mount in situ hybridization was performed according to the standard protocol (Harland, 1991) except that BMP purple was used for developing signals. Vibratome sections were prepared as described elsewhere (Hollemann et al., 1996). Briefly, after whole-mount in situ hybridization the embryos were embedded in gloop solution (5 g/L gelatin, 380 g/L chick egg albumin and 200 g/L sucrose in 0.1 M phosphate buffer, pH 7.4) mixed with 1/10 volume 25 % (v/v) glutaraldehyde, and sectioned at a thickness of 50 μm.

RNA extraction and RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from staged Xenopus embryos using Trizol (Invitrogen), precipitated with isopropanol, and purified with RNeasy (Qiagen) after DNase I treatment. cDNA was synthesized by using Hexamer random oligonucleotides (Roche) and Superscript III (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer’s instruction. The primer for dhrs3 was designed by Primer 3. ODC was employed as loading control. The primer sequences are listed as below.

dhrs3 Fw: TTCCTCAATCAGCACTTGAA

dhrs3 Re: AGGATGAATGACCTGGAAGA

ODC Fw: CAGCTAGCTGTGGTGTGG

ODC Re: CAACATGGAAACTCACACC

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank WONG Chi Bun Thomas for technical advices on sectioning. This work was supported by the one-line budget of Department of Anatomy, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong to H.Z., and the Intramural Research Program of National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health, USA to I.D

References

- Abu-Abed S, Dolle P, Metzger D, Beckett B, Chambon P, Petkovich M. The retinoic acid-metabolizing enzyme, CYP26A1, is essential for normal hindbrain patterning, vertebral identity, and development of posterior structures. Genes Dev. 2001;15:226–40. doi: 10.1101/gad.855001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bendtsen JD, Nielsen H, von Heijne G, Brunak S. Improved prediction of signal peptides: SignalP 3.0. J Mol Biol. 2004;340:783–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartry J, Nichane M, Ribes V, Colas A, Riou JF, Pieler T, Dolle P, Bellefroid EJ, Umbhauer M. Retinoic acid signalling is required for specification of pronephric cell fate. Dev Biol. 2006;299:35–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.06.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen F, Desai TJ, Qian J, Niederreither K, Lu J, Cardoso WV. Inhibition of Tgf beta signaling by endogenous retinoic acid is essential for primary lung bud induction. Development. 2007;134:2969–79. doi: 10.1242/dev.006221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Pan FC, Brandes N, Afelik S, Solter M, Pieler T. Retinoic acid signaling is essential for pancreas development and promotes endocrine at the expense of exocrine cell differentiation in Xenopus. Dev Biol. 2004;271:144–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Pollet N, Niehrs C, Pieler T. Increased XRALDH2 activity has a posteriorizing effect on the central nervous system of Xenopus embryos. Mech Dev. 2001;101:91–103. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(00)00558-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esteban-Pretel G, Marin MP, Renau-Piqueras J, Barber T, Timoneda J. Vitamin A deficiency alters rat lung alveolar basement membrane Reversibility by retinoic acid. J Nutr Biochem. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2008.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gronemeyer H, Gustafsson JA, Laudet V. Principles for modulation of the nuclear receptor superfamily. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2004;3:950–64. doi: 10.1038/nrd1551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haeseleer F, Huang J, Lebioda L, Saari JC, Palczewski K. Molecular characterization of a novel short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase that reduces all-trans-retinal. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:21790–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.34.21790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollemann T, Chen Y, Grunz H, Pieler T. Regionalized metabolic activity establishes boundaries of retinoic acid signalling. EMBO J. 1998;17:7361–72. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.24.7361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollemann T, Schuh R, Pieler T, Stick R. Xenopus Xsal-1, a vertebrate homolog of the region specific homeotic gene spalt of Drosophila. Mech Dev. 1996;55:19–32. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(95)00485-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maden M. Retinoids and spinal cord development. J Neurobiol. 2006;66:726–38. doi: 10.1002/neu.20248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendelsohn C, Lohnes D, Decimo D, Lufkin T, LeMeur M, Chambon P, Mark M. Function of the retinoic acid receptors (RARs) during development (II). Multiple abnormalities at various stages of organogenesis in RAR double mutants. Development. 1994;120:2749–71. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.10.2749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mic FA, Haselbeck RJ, Cuenca AE, Duester G. Novel retinoic acid generating activities in the neural tube and heart identified by conditional rescue of Raldh2 null mutant mice. Development. 2002;129:2271–82. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.9.2271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niederreither K, Vermot J, Messaddeq N, Schuhbaur B, Chambon P, Dolle P. Embryonic retinoic acid synthesis is essential for heart morphogenesis in the mouse. Development. 2001;128:1019–31. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.7.1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryckebusch L, Wang Z, Bertrand N, Lin SC, Chi X, Schwartz R, Zaffran S, Niederreither K. Retinoic acid deficiency alters second heart field formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:2913–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712344105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandell LL, Sanderson BW, Moiseyev G, Johnson T, Mushegian A, Young K, Rey JP, Ma JX, Staehling-Hampton K, Trainor PA. RDH10 is essential for synthesis of embryonic retinoic acid and is required for limb, craniofacial, and organ development. Genes Dev. 2007;21:1113–24. doi: 10.1101/gad.1533407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen HB, Chou KC. Signal-3L: A 3-layer approach for predicting signal peptides. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;363:297–303. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.08.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirbu IO, Duester G. Retinoic-acid signalling in node ectoderm and posterior neural plate directs left-right patterning of somitic mesoderm. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:271–7. doi: 10.1038/ncb1374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strate I, Min TH, Iliev D, Pera EM. Retinol dehydrogenase 10 is a feedback regulator of retinoic acid signalling during axis formation and patterning of the central nervous system. Development. 2009;136:461–72. doi: 10.1242/dev.024901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanegashima K, Zhao H, Dawid IB. WGEF activates Rho in the Wnt-PCP pathway and controls convergent extension in Xenopus gastrulation. EMBO J. 2008;27:606–17. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermot J, Pourquie O. Retinoic acid coordinates somitogenesis and left-right patterning in vertebrate embryos. Nature. 2005;435:215–20. doi: 10.1038/nature03488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wingert RA, Selleck R, Yu J, Song HD, Chen Z, Song A, Zhou Y, Thisse B, Thisse C, McMahon AP, Davidson AJ. The cdx genes and retinoic acid control the positioning and segmentation of the zebrafish pronephros. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:1922–38. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao H, Tanegashima K, Ro H, Dawid IB. Lrig3 regulates neural crest formation in Xenopus by modulating Fgf and Wnt signaling pathways. Development. 2008;135:1283–93. doi: 10.1242/dev.015073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.