Abstract

Objective

To examine the effectiveness of current community-based participatory research (CBPR) clinical trials involving racial and ethnic minorities.

Data Source

All published peer-reviewed CBPR intervention articles in PubMed and CINAHL databases from January 2003 to May 2010.

Study Design

We performed a systematic literature review.

Data Collection/Extraction Methods

Data were extracted on each study's characteristics, community involvement in research, subject recruitment and retention, and intervention effects.

Principle Findings

We found 19 articles meeting inclusion criteria. Of these, 14 were published from 2007 to 2010. Articles described some measures of community participation in research with great variability. Although CBPR trials examined a wide range of behavioral and clinical outcomes, such trials had very high success rates in recruiting and retaining minority participants and achieving significant intervention effects.

Conclusions

Significant publication gaps remain between CBPR and other interventional research methods. CBPR may be effective in increasing participation of racial and ethnic minority subjects in research and may be a powerful tool in testing the generalizability of effective interventions among these populations. CBPR holds promise as an approach that may contribute greatly to the study of health care delivery to disadvantaged populations.

Keywords: Community-based participatory research, clinical trials, systematic review, racial and ethnic minorities

The value of fostering community engagement in health disparities research has long been apparent (Kindon, Pain, and Kesby 2007; Minkler and Wallerstein 2008). Engaging community members in interventional studies and projects is an attractive approach through which researchers may more effectively increase racial and ethnic minority participation in trials, theoretically improving measurement of health disparities and yielding more valuable research data (Minkler and Wallerstein 2008). Community-based participatory research (CBPR) is an approach to research that takes community involvement beyond the subject participant level. Studies employing CBPR engage community members not as subjects, but rather as partners, involving the community in every stage of research, ideally from identifying the study question at hand, to developing an intervention, recruiting participants, collecting data, interpreting research findings, delivering interventions, and disseminating results (Israel et al. 2005).

Community-based participatory research theory suggests that engaging community members as collaborators in health disparities research is powerful on multiple levels. Developing a research project from the bottom-up (starting with community members to identify salient issues important to a particular population) rather than the traditional top-down approach (where researchers identify an agenda that may not be reflective of a community's needs) would inherently appear to improve a population's participation and enthusiasm for an intervention. Since CBPR researchers approach community members as partners, not subjects, one would expect that the community's engagement and retention would be maximized, as the community would be invested in the intervention and outcomes. One could therefore argue that CBPR could be a powerful tool for researchers to improve measurement of health disparities and to analyze health care delivery to particular communities, as well as for policy makers interested in legislating effective and meaningful change for these communities.

Though appealing on many levels, CBPR is often a challenging investment for researchers. Often, the level of time commitment required is substantial, given the time needed for researchers to build and sustain community partnerships (Kindon, Pain, and Kesby 2007; Minkler and Wallerstein 2008). Furthermore, few studies have been identified that successfully combine the approach of community collaboration with rigorous research methods. In 2004, the Agency of Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) published a review of the CBPR literature spanning the years 1975–2003, which revealed that while many studies employed the methods of CBPR, few combined this collaborative approach with rigorous methods of scientific inquiry such as randomized-controlled designs (Viswanathan et al. 2004). The report provided guidelines for researchers on how to increase the scientific rigor of studies employing CBPR. Since the AHRQ report was released, however, there has been no further examination of the quality, scientific rigor, and effectiveness of published CBPR studies. To address this knowledge gap, we performed a systematic review of published articles from 2003 to 2010 that employed CBPR methodology in clinical trials. Our study aims to establish the rigor and effectiveness of current CBPR clinical trials and thereby describe the current state of CBPR in the clinical trial literature. By examining the CBPR trials published during this time period and the effectiveness of interventions, we hope to assess whether this method of research holds promise as a meaningful method of investigation for health services research.

Methods

Overview

Recognizing that the body of CBPR literature is far more extensive than the studies indexed on Index Medicus (Wallerstein et al. 2008) and in keeping with the AHRQ systematic review method, we chose to review only those articles indexed in databases of peer-reviewed literature, which represent the journals with reliable peer-reviewed processes and are the most reliably accessible methods of study retrieval for researchers and policy makers. We therefore performed a systematic review of PubMed and CINAHL databases from 2003 to 2010 to find all English-language clinical trials in English-speaking North America that employed CBPR. We defined our limit starting in 2003 given the AHRQ review of the CBPR literature up until that year. This study was approved by the Humans Subjects Committee of Partners Health Care.

In efforts to specifically address the conclusions learned from the AHRQ report, we chose to include only clinical trials, or research studies in which an intervention was compared to usual care or another intervention, in our systematic review. We chose to focus our review on interventional studies so as to highlight how a CBPR approach might improve the validity of interventional studies with diverse populations, as clinical trials are currently a prominent focus of clinical research. It is of utmost importance to note, however, that a vital portion of the CBPR literature involves research that would not be categorized as interventional trials. Although there is much to learn from noninterventional studies, we hope that analysis of interventional trials in this article will better allow for comparison of how CBPR can improve on the existing clinical trial model.

Search Strategy

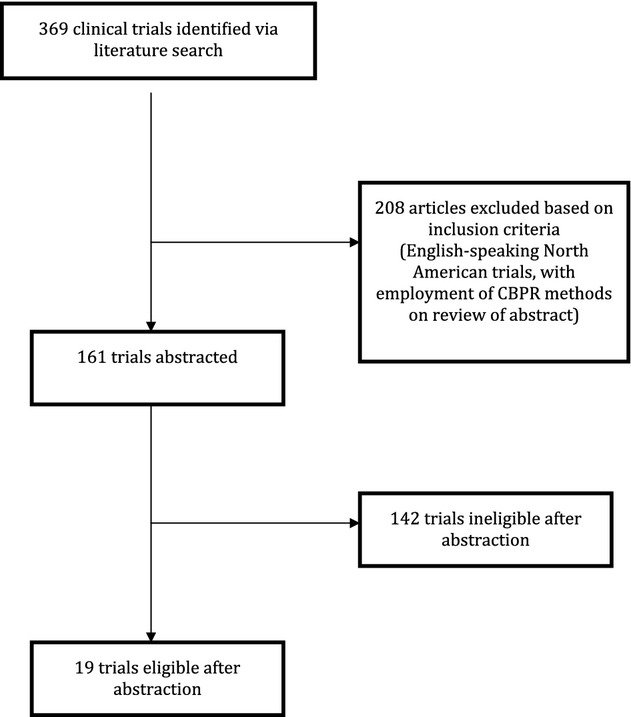

The year 2009 marked the inception of the Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) “Community-based participatory research” in literature search databases. With the guidance of experienced research librarians, we identified relevant clinical trials using a combination of the formal MeSH “community-based participatory research,” the MeSH “cooperative behavior” which was utilized prior to the introduction of CBPR as a MeSH heading from 1997 to 2008, the MeSH “community-institutional relations,” and informal search terms, including “participatory research,” “community-based participatory action,” and “clinical trials.” Our search identified 369 abstracts for review. One of the authors (D. D.) thereafter assessed the appropriateness of the studies for review. Articles were excluded initially if they were conducted outside of the United States or Canada or were not clinical trials. After this initial review, 161 articles remained for data abstraction. This process was similar to that employed in the AHRQ systematic review (Viswanathan et al. 2004). Figure illustrates the detailed search strategy employed for this review.

Figure 1.

Flow Diagram Detailing Study Selection

Data Abstraction

Four reviewers independently conducted a systematic review of the CBPR studies using the PRISMA approach as a guideline for data abstraction and assessment (Moher et al. 2009). After consensus was obtained on the abstraction tool, all four reviewers used a small sample of studies (three articles) and tested reviewer agreement (kappa = 0.87). From each article, eligibility was first identified based on the following criteria: (1) employment of CBPR methodology; (2) whether the article was a clinical trial; (3) whether the study reported clinical results. These criteria led to the final inclusion of only 19 of the 161 articles for further extraction. From these 19 articles, the following data were extracted: (1) clinical trial design (controlled versus noncontrolled, randomized versus nonrandomized, and level of randomization); (2) rigor of the CBPR method (including whether descriptions of community partner involvement were cited in recruitment of subjects, development of interventions, delivery of interventions, and interpretation of research findings); (3) racial and ethnic composition of participants, as well as subject recruitment and retention; and (4) intervention effects.

Analysis

We present data from all included studies regarding methodology of CBPR, recruitment and retention of research participants, and presentation of clinical results. Although the studies were too heterogeneous to perform a meta-analysis, aggregate frequencies, means, and proportions of data are identified as appropriate.

Results

Article Characteristics

Our systematic review covered 19 peer-reviewed articles of which 13 were randomized-control trials (Table 1). Of the 19 studies, 18 reported the numbers of individual participants. Of these, 17 studies (representing 18,818 participants) reported the racial and ethnic composition of participants. Six studies had samples that were >50 percent Latino, six studies recruited participant pools that were >50 percent non-Hispanic black, one study reported a subject population that was 100 percent Asian, and the remainder had a majority of non-Hispanic white study participants (Table 1). The majority of the trials (68 percent) were randomized-control trials, and of these studies, 23 percent were randomized at the level of the individual, with the remaining 77 percent employing cluster randomization. Of the six nonrandomized trials, 50 percent had a control group, with the remaining trials comparing measures preintervention and postintervention in a given cohort.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Articles Included in Analysis (N = 19)

| Primary Author, Year of Article | Type of Clinical Trial | Type of Randomization | Area of Focus | Number of Participants Eligible for Study | Number of Participants Enrolled | Number of Participants Retained | Percent Retained | Ethnic Composition of Participants (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Balcazar et al. (2009) | Randomized control | Individual participant | Participant behavior | 98 | 98 | 98 | 100 | Latino (100) |

| Balcazar et al. (2010) | Randomized control | Individual participant | Participant behavior | 568 | 328 | 284 | 87 | Latino (100) |

| Blumenthal et al. (2010) | Randomized control | Cluster randomization by site of recruitment (church, community center, or clinic) | Clinical | 645 | 369 | 259 | 70 | Non-Hispanic black (100) |

| Estabrooks et al. (2008) | Nonrandomized | NA | Participant behavior | 4,609 | 1,190 | 1,045 | 88 | Non-Hispanic white (95) |

| Latino (1) | ||||||||

| Native American (1) | ||||||||

| Not cited (3) | ||||||||

| Feinberg et al. (2007) | Randomized control | Cluster randomization by community | Other | 157 | 53 | 29 | 55 | Not cited |

| Froelicher et al. (2010) | Randomized control | Cluster randomization by groups | Participant behavior | 191 | 60 | 22 | 37 | Non-Hispanic black (100) |

| Horowitz et al. (2009) | Randomized control, delayed intervention | Individual participant | Other | 249 | 99 | Not reported | NA | Latino (89) |

| Non-Hispanic black (9) | ||||||||

| Asian (1) | ||||||||

| Native American (1) | ||||||||

| Kim et al. (2008) | Nonrandomized, concurrent control | NA | Participant behavior | Not reported | 73 | 61 | 84 | Non-Hispanic black (100) |

| Leeman-Castillo et al. (2010) | Nonrandomized | NA | Participant behavior | 333 | 299 | 245 | 82 | Latino (100) |

| Levine et al. (2003) | Randomized control | Cluster randomization by census blocks | Health care delivery | 817 | 789 | 471 | 60 | Non-Hispanic black (100) |

| Linnan et al. (2005) | Nonrandomized | NA | Other | Not reported | 162 | 83 | 51 | Non-Hispanic black (68.5) |

| Non-Hispanic white (31.5) | ||||||||

| Mikami, Boucher, and Humphreys (2005) | Randomized control | Cluster randomization by classroom | Other | Not reported | 24 classrooms (individuals not reported) | Not reported | NA | Not reported |

| Nguyen et al. (2006) | Nonrandomized, cross-sectional, with control community | NA | Health care delivery | Not reported | 1,566, 2009 (at each cross-sectional survey) | NA | NA | Asian (100) |

| Parikh et al. (2010) | Randomized control with delayed intervention | Cluster randomization by recruitment site | Participant behavior | 103 | 99 | 72 | 73 | Latino (89) |

| Non-Hispanic black (9) | ||||||||

| Not reported (2) | ||||||||

| Redmond et al. (2009) | Randomized control | Cluster randomization by community | Participant behavior | 13,257 | 11,931 | 9,438 | 79 | Non-Hispanic white (83) |

| Non-Hispanic black (3) | ||||||||

| Latino (5) | ||||||||

| Not reported (9) | ||||||||

| Reed and Kidd (2004) | Randomized control | Cluster randomization by school | Participant behavior | Not reported | 1,138 | 373 | 33 | Non-Hispanic white (98) |

| Not reported (2) | ||||||||

| Riggs, Nakawatase, and Pentz (2008) | Randomized control | Cluster randomization by community | Other | 431 | 431 | 154 | 36 | Not reported (100) |

| Siegel et al. (2010) | Randomized control | Cluster randomization by school | Participant behavior | Not reported | 413 | 125 | 30 | Latino (48.4 control, 60.8 intervention) |

| Non-Hispanic white (27 control, 19.8 intervention) | ||||||||

| Non-Hispanic black (9.7 control, 4.1 intervention) | ||||||||

| Not reported (17.8 control, 15.5 intervention) | ||||||||

| Two Feathers et al. (2005) | Nonrandomized | NA | Participant behavior | 300 | 151 | 111 | 74 | Non-Hispanic black (64) |

| Latino (36) |

Rigor of CBPR Approach

Table 2 presents the level of involvement of community partners in each interventional trial, among the studies reporting the degree to which community members participated. The majority of studies reported community involvement in identifying study questions (63 percent), recruitment of subjects (84 percent), development of the intervention (74 percent), delivery of the intervention (84 percent), data collection (68 percent), or the formation of a community advisory committee (63 percent). However, very few of the studies cited involvement of the community in the interpretation of either quantitative or qualitative research findings (21 and 37 percent, respectively) or in efforts to disseminate trial findings (47 percent) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Description of Community Partners' Involvement in Clinical Trials (N = 19)

| Primary Author | Identifying Study Questions | Recruitment of Subjects | Development of Intervention | Delivery of Intervention | Data Collection | Quantitative Interpretation of Findings | Qualitative Interpretation of Findings | Dissemination Efforts | Presence of Advisory Committee |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Balcazar (2009) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| Balcazar (2010) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No |

| Blumenthal | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Estabrooks | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes |

| Feinberg | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Froelicher | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | No |

| Horowitz | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes |

| Kim | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| Leeman-Castillo | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No |

| Levine | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Linnan | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Mikami | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Nguyen | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Parikh | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Redmond | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes |

| Reed | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes |

| Riggs | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Siegel | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes |

| Two Feathers | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes |

Presentation of Results

For each of the 19 reviewed articles, we describe the presentation of their clinical results in Table 3. The majority of reviewed trials (14/19) examined behavioral outcomes (such as daily salt intake or level of physical activity), either alone (5/19), in combination with clinical outcomes (such as body mass index or blood pressure) (7/19), or in combination with process measures (such as recruitment of participants) (2/19). The majority of the trials (17/19) included a control group, and of these, 10 studies (59 percent) described baseline differences between control and intervention participants. Of the 17 articles examining either a concurrent or historical control group, 13 reported a significant difference in outcomes among the intervention group when compared with controls; however, four of these studies did not adjust for baseline differences between groups in the analyses (Table 3). Overall, the majority of studies we reviewed (89 percent) demonstrated a statistically positive effect of their interventions.

Table 3.

Presentation of Results in CBPR Clinical Trials (N = 19)

| Primary Author | Significant Differences between Control and Study Group Noted? | Significant Baseline Differences Adjusted for in Results | Type(s) of Outcomes under Study | Baseline Measures Reported | Outcome Measures Reported | Primary Outcomes of Study | Study Successful in Achieving Primary Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Balcazar (2009) | Yes | Yes | Clinical behavioral | Yes | Yes | No difference in waist circumference or BMI; significant differences among perceived benefits and salt, cholesterol, and fat intake | Yes |

| Balcazar (2010) | Yes | Yes | Clinical behavioral | Yes | Yes | Significant improvement in diastolic BP, weight control practices, salt, cholesterol, and fat intake | Yes |

| Blumenthal | Yes | No | Clinical knowledge, behavioral | Yes | Yes | Significant increase in colorectal cancer knowledge, increase in colorectal cancer screening rates within 6 months of intervention | Yes |

| Estabrooks | No | NA | Behavioral | Yes | Yes | Inactive or insufficiently active participants at baseline experienced significant increases in both moderate and vigorous physical activity | Yes |

| Feinberg | No | NA | Process | Yes | Yes | Coalition functioning in a youth recruitment intervention | Yes |

| Froelicher | Yes | No | Behavioral | Yes | Yes | No statistically significant differences in smoking between control group and interventional group | No |

| Horowitz | NA | NA | Process (recruitment) | Yes | Yes | Recruitment of minority populations | Yes |

| Kim | Yes | Yes | Clinical behavioral | Yes | Yes | Anthropometrics (BMI, waist: hip ratio) and health behaviors | Yes; reduced weight, reduced hip and weight girth, and increased physical activity compared with control |

| Leeman-Castillo | NA | NA | Behavioral | Yes | Yes | Nutritional intake by guidelines, physical activity by guidelines, smoking cessation | Yes; improved fruit and vegetable intake, increased levels of physical activity |

| Levine | No | NA | Clinical | Yes | Yes | Mean systolic and diastolic blood pressure | No; both groups exhibited increased BP control, no difference between more versus less intensive care |

| Linnan | NA | NA | Process (communication regarding health messages) | No | Yes | Discussion/communication of health behaviors | Yes; high levels of self-reported discussions of health behaviors, and high recall of discussions after 12 months |

| Mikami | No | NA | Report of peer relations | Yes | Yes | Ratings of peer relationships | Yes; intervention group had improved peer relationships over time |

| Nguyen | No | NA | Behavioral process (capacity building infrastructure) | Yes | Yes | Pap test outcomes | Yes |

| Parikh | Yes | No | Clinical behavioral | Yes | Yes | Weight loss | Yes; significant weight loss noted in intervention group |

| Redmond | No | No | Behavioral attitudes | No | Yes | Youth, parent and family relationship (general child management, parent–child effective quality, parent–child activities) | Yes; general child management, parent–child activities, and skill outcomes improved in intervention group |

| Reed | Yes | No | Behavioral attitudes | No | No | Farm safety attitudes | Yes; positive changes in farm safety attitudes and discussions related to injury prevention, and improved safety behavior |

| Riggs | Yes | No | Behavioral process (community organization empowerment) | Yes | Yes | Quality of strategic plans; committee functioning; prevention plan activities | Yes; increased quality of strategic plans; higher committee functioning; increased prevention plan activities |

| Siegel | Yes | Yes | Clinical behavioral | Yes | Yes | BMI, waist: hip ratio, minutes of physical activity, fruit and vegetable intake | Yes; reduction in BMI |

| Two Feathers | Yes | Yes | Clinical behavioral other | Yes | Yes | Change in Hg A1C, weight, BMI, BP | Yes |

Discussion

In our comprehensive systematic review of all North American CBPR clinical trials published since 2003, we found 19 articles reporting clinical trial results. To our knowledge, this study is the first detailed examination of the progress CBPR has made in publishing interventional research and provides a benchmark for the effectiveness of utilizing CBPR in clinical trials. Despite the paucity of published clinical trials utilizing CBPR, particularly in the examination of health care oriented interventions, the results of our review suggest that the state of the published CBPR clinical trial literature has actually grown significantly since the findings of the 2004 AHRQ report (Viswanathan et al. 2004). Viswanathan et al. identified 30 interventional studies in a 28-year period, whereas our findings reveal 19 clinical trials published recently in just 7 years, a fourth of the time period investigated for the AHRQ report. We also found that these peer-reviewed articles describe some measures of community participation in research in fair detail, but that other parts of CBPR methodology, most notably involvement in interpretation of research findings and dissemination efforts, are poorly described. Lastly we found that although CBPR trials examined a wide range of behavioral, process-related, and clinical outcomes, such trials had very high success rates in recruiting and retaining minority participants and achieving significant intervention effects.

Prior examination of the state of CBPR has suggested that published interventional studies are relatively few, and when published, frequently do not report final analytic results. In their examination of 60 CBPR articles published from 1975 to 2003, the AHRQ group found that 30 of the studies did not report an intervention (Viswanathan et al. 2004). Of the remaining 30 studies, only 12 (20 percent) evaluated an intervention and the remaining 18 had not completed or fully evaluated an intervention. Further, they found that CBPR was frequently published in special issues related to CBPR. For example, of the 12 CBPR articles that evaluated an intervention, three (25 percent) were published in the same special issue (Viswanathan et al. 2004). Similarly, we found 19 published interventional studies utilizing CBPR from 2003 to 2010. There may, however, be positive trends both in the number of journals publishing CBPR research and in the number of CBPR interventions being published. The 19 studies in our review were published in 13 different journals. Of the 19 trials identified, the majority (68 percent) were randomized trials utilizing control groups and therefore may be considered to have a strong evidence base in their findings. We also found that 14 (74 percent) of the articles in our review were published since 2007, representing a stark contrast to the low number (5) of CBPR interventional studies published in the 3-year period from 2003 to 2006. Furthermore, in 2007, a peer-reviewed journal specifically dedicated to CBPR, the journal Progress in Community Health Partnerships, was released. This journal may become a forum for more CBPR interventional research to be published in peer-reviewed literature moving forward.

The degree to which community participation in research is the key factor separating CBPR from other research paradigms is thought to be a critical component of improving both the measurement and the elimination of health disparities. We found that the community involvement described in recently published CBPR trials is variable (Horowitz, Robinson, and Seifer 2009). In our review, community partners were most frequently described as being involved in participant recruitment and in the development and delivery of the intervention. However, community partners were only described as participating in the interpretation of quantitative research findings 21 percent of the time and in dissemination efforts in 47 percent of the studies. Our findings are supported by prior evaluations that demonstrate community involvement in intervention development in over 90 percent of CBPR trials, though CBPR articles rarely, if ever, mention involvement of community partners in interpretation of research findings, the manuscript preparation process, or other dissemination efforts (Viswanathan et al. 2004). One possible explanation for this variability may be that researchers have yet to identify the best strategies for community inclusion in analysis. This may be in part due to differences in research knowledge and in part due to differences in interest. In addition, both community and academic research partners may feel far less comfortable with the process and time required to teach community partners analytic and manuscript writing skills. It is reasonable to assume that community partners may prefer to limit involvement to their particular strengths, such as community recruitment and intervention delivery. Our findings underscore the need to further emphasize the importance of knowledge sharing activities in CBPR partnerships in an effort to increase research literacy among community partners.

Many authors have suggested that the role community partners and liaisons play in recruitment may significantly improve the effectiveness and retention of minority participation in research. For example, in a recent systematic review, Yancey et al. examined the relative effectiveness of strategies for recruiting racial and ethnic minorities and concluded that among factors most associated with success, active involvement of existing community stakeholders was critical (Yancey, Ortega, and Kumanyika 2006). In another study, researchers found that among veterans, most minorities recruited for focus groups were recruited with the help of community-based liaisons (Dhanani et al. 2002). Our finding that the majority of participants in 13 (68 percent) of the published CBPR interventional trials were racial and ethnic minorities supports the assertion that CBPR may be particularly effective in the recruitment of minorities in clinical research. For those articles that reported retention (16/19 trials), retention was notably favorable (average retention rate 65 percent), indicating that CBPR may be effective not only for recruitment of participants but also for retention. Furthermore, the success rate of the interventions reported in our review was extremely high (89 percent); while this finding is likely influenced by a significant bias toward publication of positive results and must be interpreted with caution (Emerson et al. 2010), our review suggests that CBPR may also be effective in improving behavioral- and health-related outcomes among largely minority populations. Lastly, most (15/19) of the clinical trials identified in our review were designed for addressing clinical or behavioral outcomes among minority communities. The goal of these studies was to identify methods through which clinicians and researchers can improve the health behaviors and outcomes of disadvantaged communities, thereby addressing the disparities in health outcomes that currently exist. Given the effectiveness of CBPR in improving outcomes from behaviorally targeted interventions, our findings suggest that CBPR is underutilized in interventions aimed at health care improvement (e.g., improving blood pressure or cancer screening rates) and that future research investigating health services interventions may benefit from the CBPR paradigm.

This review is subject to several limitations. Chiefly, our examination of the state of CBPR was limited only to examining clinical trials. We chose to limit our assessment to clinical trials because prior research has documented that CBPR publications are historically lacking in this methodology. We aimed to go beyond heralding the potential of CBPR by more concretely examining the scientific rigor and effectiveness of the research. Second, we chose to limit our analysis to an examination of only those CBPR clinical trials published in peer-reviewed literature and indexed in Index Medicus. We acknowledge that this renders our analysis subject to publication bias in the literature; a recent article in Archives of Internal Medicine highlights that positive-outcome studies are more likely to be published in peer-reviewed journals than equally methodologically sound null studies (Emerson et al. 2010). However, in keeping with the PRISMA approach for reporting systematic reviews (Moher et al. 2009), we chose to limit our initial search strategy to only those studies published in peer-reviewed literature and indexed in Index Medicus, which we acknowledge as the most reliable and most easily accessible database utilized by researchers and policy makers. We nevertheless advocate that continued research focused on the critical analysis of all study designs employed with the CBPR methodology in both the published and nonpublished literature is needed to fully explore the unique contributions of the CBPR model to interventional research, as recently reinforced by two of the field's leading researchers (Wallerstein and Duran 2010). Since one limitation of systematic reviews is that they are cross-sectional in nature, it is possible that our search did not yield eligible articles published from 2003 to 2010 that had not been indexed at the time of our search. In addition, there remain the possibilities that a significant publication lag in CBPR exists when compared with other research paradigms, and that much of the CBPR interventional research conducted in recent years has not yet been submitted or completed the peer-review process. Our finding of a significantly increasing trend in the rate of CBPR clinical trials published over the past few years may suggest such a lag exists and is supported by a prior review that demonstrated that 67 percent of published CBPR interventional trials were either in progress or the intervention had not fully been evaluated (Viswanathan et al. 2004). Furthermore, our review was limited to studies published in English and conducted in North America; we anticipate that the state of CBPR conducted outside of the North America and its effectiveness in recruiting minority subjects may differ. Lastly, the studies included in our analyses employed a wide variety of intervention strategies and examined a myriad of clinical and behavioral outcomes, precluding our ability to conduct a more detailed meta-analysis examining the effectiveness of CBPR interventions. As a result, we remain unable to compare outcomes of CBPR studies to other interventional research strategies.

Limitations aside, our study highlights that CBPR excels in two areas: (1) recruitment and retention of racial and ethnic minority participants, a population that has traditionally been difficult to engage in clinical trials, and (2) effectiveness of interventions geared toward these communities. We therefore theorize that CBPR can be an incredibly rich and effective approach to the research of health care delivery, resource allocation, and health care utilization. A recently published study of the use of patient navigators for promotion of colorectal cancer screening among patients at community health centers, for example, revealed a statistically significant increase in colon cancer screening rate with the use of patient navigators, compared with the population of patients who received routine colon cancer screening recommendations alone without the aid of a patient navigator (Lasser et al. 2009, 2011). Lessons learned from such a study can be used by policy makers to help fund patient navigators in community health care center settings, increase cancer screening rates, and thereby improve long-term outcomes in this population. Our results suggest that CBPR is a promising tool that may contribute to interventional studies and analyses and therefore could play a role in facilitating research's impact on health care policy and resource allocation.

Conclusion

We found that the state of CBPR interventional research is rapidly evolving with a significant increase in both the number of journals publishing CBPR and the number of interventional studies published. However, there remains a relative lack of published peer-reviewed CBPR interventional studies and a significant gap in publication between CBPR and other interventional research methods. Our findings demonstrate that CBPR is particularly effective in increasing participation of racial and ethnic minority subjects in research and may be a powerful tool to improve both the measurement of health disparities and in testing the generalizability of effective interventions among populations traditionally under-represented in clinical trials. For these reasons, CBPR is a promising research approach that may be useful in analyses of health care delivery for disadvantaged patients.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article:

Appendix SA1: Author Matrix.

Please note: Wiley-Blackwell is not responsible for the content or functionality of any supporting materials supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the corresponding author for the article.

References

- Balcazar HG, Byrd TL, Ortiz M, Tondapu SR, Chavez M. “A Randomized Community Intervention to Improve Hypertension Control among Mexican Americans: Using the Promotoras de Salud Community Outreach Model”. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2009;20((4)):1079–94. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balcazar H, De Heer H, Rosenthal L, Aguirre M, Flores L, Puentes FA, Cardenas VM, Duarte MO, Ortiz M, Schulz LO. “A Promotores de Salud Intervention to Reduce Cardiovascular Disease Risk in a High-Risk Hispanic Border Population”. Preventing Chronic Disease. 2010;7((2)):1–10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumenthal DS, Smith SA, Majett CD, Alema-Mensah E. “A Trial of 3 Interventions to Promote Colorectal Cancer Screening in African Americans”. Cancer. 2010;116((4)):922–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhanani S, Damron-Rodriguez J, Leung M, Villa V, Washington DL, Makinodan T, Harada N. “Community-Based Strategies for Focus Group Recruitment of Minority Veterans”. Military Medicine. 2002;167((6)):501–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emerson GB, Warme WJ, Wolf FM, Heckman JD, Brand RA, Leopold SS. “Testing for the Presence of Positive-Outcome Bias in Peer Review: A Randomized Controlled Trial”. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2010;170((21)):1934–9. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estabrooks PA, Bradshaw M, Dzewaltowski DA, Smith-Ray RL. “Determining the Impact of Walk Kansas: Applying a Team-Building Approach to Community Physical Activity Promotion”. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2008;36((1)):1–12. doi: 10.1007/s12160-008-9040-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg ME, Chilenski SM, Greenberg MT, Spoth RL, Redmond C. “Community and Team Member Factors That Influence the Operations Phase of Local Prevention Teams: The PROSPER Project”. Prevention Science. 2007;8((3)):214–26. doi: 10.1007/s11121-007-0069-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Froelicher ES, Doolan D, Yerger VB, McGruder CO, Malone RE. “Combining Community Participatory Research with a Randomized Clinical Trial: The Protecting the Hood Against Tobacco (PHAT) Smoking Cessation Study”. Heart and Lung. 2010;39((1)):50–63. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2009.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz CR, Robinson M, Seifer S. “Community-Based Participatory Research from the Margin to the Mainstream: Are Researchers Prepared?”. Circulation. 2009;119((19)):2633–42. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.729863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz CR, Brenner BL, Lachapelle S, Amara DA, Arniella G. “Effective Recruitment of Minority Populations through Community-Led Strategies”. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2009;37(6 suppl 1):S195–200. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel B, Eng E, Schulz A, Parker E. Methods in Community-Based Participatory Research for Health. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kim KH, Linnan L, Campbell MK, Brooks C, Koenig HG, Wiesen C. “The WORD (Wholeness, Oneness, Righteousness, Deliverance): A Faith-Based Weight-Loss Program Utilizing a Community-Based Participatory Research Approach”. Health Education & Behavior. 2008;35((5)):634–50. doi: 10.1177/1090198106291985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kindon S, Pain R, Kesby M. Participatory Action Research Approaches and Methods: Connecting People, Participation and Place. New York: Routledge Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Lasser KE, Murillo J, Medlin E, Lisboa S, Valley-Shah L, Fletcher RH, Emmons KM, Ayanian JZ. “A Multilevel Intervention to Promote Colorectal Cancer Screening among Community Health Center Patients: Results of a Pilot Study”. BMC Family Practice. 2009;10:37–43. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-10-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasser KE, Murillo J, Lisboa S, Casimir AN, Valley-Shah L, Emmons KM, Fletcher RH, Ayanian JZ. “Patient Navigation to Promote Colorectal Cancer Screening among Ethnically Diverse, Low-Income Patients: A Randomized-Controlled Trial”. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2011;171((10)):906–12. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leeman-Castillo B, Beaty B, Raghunath S, Steiner J, Bull S. “LUCHAR: Using Computer Technology to Battle Heart Disease among Latinos”. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100((2)):272–5. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.162115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine DM, Bone LR, Hill MN, Stallings R, Gelber AC, Barker A, Harris EC, Zeger SL, Felix-Aaron KL, Clark JM. “The Effectiveness of a Community/Academic Health Center Partnership in Decreasing the Level of Blood Pressure in an Urban African-American Population”. Ethnicity and Disease. 2003;13((3)):354–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linnan LA, Ferguson YO, Wasilewski Y, Lee AM, Yang J, Solomon F, Katz M. “Using Community-Based Participatory Research Methods to Reach Women with Health Messages: Results from the North Carolina BEAUTY and Health Pilot Project”. Health Promotion Practice. 2005;6((2)):164–73. doi: 10.1177/1524839903259497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikami AY, Boucher MA, Humphreys K. “Prevention of Peer Rejection through a Classroom-Level Intervention in Middle School”. Journal of Primary Prevention. 2005;26((1)):5–23. doi: 10.1007/s10935-004-0988-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minkler M, Wallerstein N. Community-Based Participatory Research for Health: from Process to Outcomes. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group “Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement”. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2009;151((4)):264–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen TT, McPhee SJ, Bui-Tong N, Luong TN, Ha-Iaconis T, Nguyen T, Wong C, Lai KQ, Lam H. “Community-Based Participatory Research Increases Cervical Cancer Screening among Vietnamese-Americans”. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2006;17(2 suppl):31–54. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2006.0091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parikh P, Simon EP, Fei K, Looker H, Goytia C, Horowitz CR. “Results of a Pilot Diabetes Prevention Intervention in East Harlem, New York City: Project HEED”. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100(suppl 1):S232–9. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.170910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redmond C, Spoth RL, Shin C, Schainker LM, Greenberg MT, Feinberg M. “Long-Term Protective Factor Outcomes of Evidence-Based Interventions Implemented by Community Teams through a Community-University Partnership”. Journal of Primary Prevention. 2009;30((5)):513–30. doi: 10.1007/s10935-009-0189-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed DB, Kidd PS. “Collaboration between Nurses and Agricultural Teachers to Prevent Adolescent Agricultural Injuries: The Agricultural Disability Awareness and Risk Education Model”. Public Health Nursing. 2004;21((4)):323–30. doi: 10.1111/j.0737-1209.2004.21405.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riggs NR, Nakawatase M, Pentz MA. “Promoting Community Coalition Functioning: Effects of Project STEP”. Prevention Science. 2008;9((2)):63–72. doi: 10.1007/s11121-008-0088-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel JM, Prelip ML, Erausquin JT, Kim SA. “A Worksite Obesity Intervention: Results from a Group-Randomized Trial”. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100((2)):327–33. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.154153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Two Feathers J, Kieffer EC, Palmisano G, Anderson M, Sinco B, Janz N, Heisler M, Spencer M, Guzman R, Thompson J, Wisdom K, James SA. “Racial and Ethnic Approaches to Community Health (REACH) Detroit Partnership: Improving Diabetes-Related Outcomes among African American and Latino Adults”. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95((9)):1552–60. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.066134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viswanathan M, Ammerman A, Eng E, Gartlehner G, Lohr KN, Griffith D, Rhodes S, Samuel-Hodge C, Maty S, Lux L, Webb L, Sutton SF, Swinson T, Jackman A, Whitener L. Community-Based Participatory Research: Assessing the Evidence. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2004. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No. 99. AHRQ Publication 04-E022-2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein N, Duran B. “Community-Based Participatory Research Contributions to Intervention Research: The Intersection of Science and Practice to Improve Health Equity”. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;1((100)):S40–6. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.184036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein N, Oetzel J, Duran B, Tafoya G, Belone L, Rae R. “What Predicts Outcomes in CBPR? In: Minkler M, Wallerstein N, editors. Community-Based Participatory Research for Health: from Process to Outcomes. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2008. pp. 371–92. [Google Scholar]

- Yancey AK, Ortega AN, Kumanyika SK. “Effective Recruitment and Retention of Minority Research Participants”. Annual Review of Public Health. 2006;27:1–28. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.27.021405.102113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.