Abstract

This review discusses atrial fibrillation according to the guidelines of Brazilian Society of Cardiac Arrhythmias and the Brazilian Cardiogeriatrics Guidelines. We stress the thromboembolic burden of atrial fibrillation and discuss how to prevent it as well as the best way to conduct cases of atrial fibrillatios in the elderly, reverting the arrhythmia to sinus rhythm, or the option of heart rate control. The new methods to treat atrial fibrillation, such as radiofrequency ablation, new oral direct thrombin inhibitors and Xa factor inhibitors, as well as new antiarrhythmic drugs, are depicted.

Keywords: Atrial fibrillation, Heart failure, Thrombo-embolism, Treatment, Prevention

1. Atrial fibrillation

Atrial fibrillation (AF) was known long before it was characterized in animals by William Harvey in 1628 in the De Motu Cordis text.[1] Arrhythmia was undervalued until approximately 30 years ago; and currently it is a major predictor of cardiovascular events, especially in the elderly. AF-related phenotypes are being detected today.[2]

Presently, several misinterpretations involve arrhythmia, especially in the elderly, such as: (1) AF is a benign arrhythmia; (2) Chemical reversion is less risky than electrical reversion; (3) Anticoagulation in the elderly is of high risk, so one should prefer antiplatelet agents; and (4) Sinus rhythm reversion eliminates anticoagulation maintenance.

These inaccurate statements increase morbidity and mortality associated with arrhythmia and lead to what we call omission iatrogeny. From the electrophysiological point of view, AF is characterized by the loss of electrical atrial homogeneity due to isolated or associated autonomic, metabolic, structural, inflammatory, or ischemic defects

AF is the most prevalent chronic arrhythmia in patients above 65 years old (5.9% of the population), and its prevalence from 50 years old on, doubles every 10 years,[3] being more common in male. In the ATRIA study, the prevalence was 0.1%, in females below 55 years of age, while in those above 85 years old, it was 9.1%; for males, figures were 0.2% and 11.0%, respectively.[4] The Western study has identified factors related to AF. First, it has identified patient's age and then hypertension, diabetes, heart failure and valve disease.[5] In the Asian population, the described factors were: age above 80 years, history of heart disease, diminished glomerular filtration rate and hypercholesterolemia.[6]

International guidelines[7] have classified AF as: (1) AF detected for the first time (symptomatic or not, self-limited, or of unknown duration, or when the presence of previous episodes is unknown, being paroxysmal or persistent); (2) paroxysmal is characterized by recurrent episodes and spontaneous reversion; (3) persistent or lasting more than seven days and needing chemical or electrical cardioversion to re-establish the sinus rhythm; and (4) permanent or lasting more than one year, and refractory to cardioversion.

The classification is only used in situations where there is no reversible AF cause, such as acute myocardial infarction, pulmonary embolism, hyperthyroidism, alcoholism, etc.[8],[9]

AF is generally associated to structural heart disease, however, it may occur in patients without detectable heart disease called isolated AF. The term should not be applied to the elderly because co-morbidities are common at this age and may contribute to arrhythmia chronicity.[10]

Historically, the first arrhythmia cause was identified as rheumatic valve disease, however with population aging and decreasing prevalence of rheumatic fever, non-valvar causes or other valve diseases have become predominant, such as myocardial infarction, pericarditis, pulmonary embolism, chronic obstructive lung disease, hypertension, heart failure (HF), chronic coronary disease, sinus node disease, ventricular hypertrophy, atrial dilatation, non-rheumatic valvulopathies and aging itself. Currently, HF is the number one cause of AF in the elderly, diagnosed in 4% of patients in functional class I,[11] and in 10% of patients in class II–III.[12]

HF evolves with structural and functional alterations which trigger and maintain AF. Atrial muscle fiber stretching is associated with a shorter refractory period and slower electrical conduction, which favor AF maintenance. Neuro- humoral alterations, such as an increase in catecholamines and renin-angiotensin system activation, also predispose to arrhythmia; on the other hand, structural and functional alterations induced by AF worsen HF.

Non-cardiovascular causes may be related to AF episodes, especially in the elderly: hyperthyroidism, dehydration, electrolytic disorders, acute alcoholism, hypoxia, diabetes, postoperative period of non-cardiac surgery and stress. With regard to patients with hyperthyroidism, it is worth stressing the high prevalence of associated AF in the elderly (10% to 30%). AF risk is increased five-fold with subclinical hyperthyroidism, which may be the one and only manifestation of the disease. In general, rhythm returns to normal with hormonal disorder reversion.[13],[14]

The major predictive factor for AF in the elderly is the left atrium size, according to the AFFIRM study (Framingham Heart Study and Cardiovascular Health Study).[15]

According to Braunwald, AF is, together with HF, the current cardiovascular pandemy.[16] This is due to longer patients' survival, especially with regard to coronary disease.

Natural AF progression starts with self- limited episodes, symptomatic or not, which increase in frequency and duration. Then, AF becomes permanent, raising the discussion of what should be done next: either maintain the rhythm with ventricular rate control and anticoagulation, or revert to sinus rhythm. The presence of cardiovascular disease with increased left atrium size is usually seen from onset of the condition. Arrhythmia chronicity causes atrial remodeling expressed through electrical, contractile and structural alterations. The decrease of the refractory period of the atrial muscle with repeated AF episodes turns them into longer- lasting episodes. Structural and contractile remodeling is represented by muscle fibers hypertrophy, normal fibers superimposed onto ill fibers and interstitial fibrosis, all leading to functional loss. The consequences of such changes are AF complications, such as intra-atrial thrombosis and possibly systemic, or pulmonary embolism. Another consequence seen at AF onset is the loss of atrial contraction, which in patients with left ventricular hypertrophy, may evolve to acute lung edema, especially in acute AF forms with high ventricular rate. Atrial systole is responsible for 25% of cardiac output in normal hearts and up to 50% in patients with ventricular dysfunction, especially in restrictive and hypertrophic cardiopathies[17],[18] In addition to these complications, chronic AF with a high ventricular rate evolves with ventricular dilatation and HF, called tachycardiomiopathy.

AF patient mortality is twice those in sinus rhythm. Regardless of the underlying disease,[19] AF is a negative prognostic marker. In the SOLVD study,[20] AF patients had 34% mortality as compared to 24% in the ones with sinus rhythm. In the Framingham study[21] the risk of stroke in AF patients was five times greater. In patients between 50 and 59 years old, the stroke chance was of 1.5% per year, and from 80 to 89 years old 23.5% per year.

According to the SPAF study,[22] the thromboembolic risks are related to systolic blood pressure above 160 mmHg, age > 75 years, recent HF, previous thrombo-embolic event, left atrial diameter > 2.5 cm/m2 and systolic shortening fraction < 25%. It also considered the presence of spontaneous atrial contrast or intra-atrial clot, confirmed by trans-esophageal echocardiogram.[23]

The risk for thromboembolic events is evaluated through the CHADS 2 score,[24] or more recently CHA2 DS2-VASc (Table 1).[25] The risk varies from 0% for those without any of the factors to 15.2% for those with maximum score (9 points).

Table 1. CHA2 DS2-VASc score and stroke rate.

| Risk factors for stroke and thrombo-embolism in non-valvular AF | |

| Major risk factors | |

| Previous stroke, TIA, systemic embolism, or age > 75 years | |

| Clinically relevant non-major factors | |

| Heart failure, or moderate to severe LV systolic dysfunction (e.g., LVEF < 40%) hypertension, diabetes mellitus, female sex, age 65–74 years, vascular disease. | |

| Risk factor based approach expressed as a point based scoring system, with the acronym CHA2DS2-VASc (maximum score is 9 since age may contribute 0, 1 or 2 points | |

| Risk factor | Score |

| Congestive heart failure/LV dysfunction | 1 |

| Hypertension | 1 |

| Age > 75 | 2 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1 |

| Stroke, TIA, Thrombo-embolism | 2 |

| Vascular disease | 1 |

| Age 65–74 yaers | 1 |

| Female sex | 1 |

| Maximum score | 9 |

LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction; TIA: transient ischemic attack.

Realization that between 65–74 years of age is worth one point, and an age above 75 years is worth two points, places this isolated factor as a risk for thromboembolic complications.

According to these criteria, patients with zero points do not need anticoagulation or anti-thrombotic drugs; patients with 1 point receive aspirin or warfarin; and patients with 2 or more points should receive warfarin with controlled dosage according to an International Normalized Ratio (INR) of between 2 and 3. Patients who cannot take warfarin should receive double anti-thrombotic therapy with aspirin and clopidogel, which in the ACTIVE A study has better protected patients than aspirin alone[26],[27] The recommended aspirin dose is controversial and studies have administered it between 81 mg and 325 mg per day.

AF is also related to cognitive disorders and vascular dementia. In the Rotterdam Study,[28] the risk of dementia was twice as high for fibrillating elderly. Elderly people with AF had memory and dementia disorders unrelated to stroke.[29],[30] This is probably due to cardioembolic events and low cardiac output.

AF in the elderly may be asymptomatic as a casual finding in routine clinical evaluation or electrocardiogram (ECG). In symptomatic patients, arrhythmic palpitation is a frequent complaint and may occur with syncope, angina, acute lung edema and/or systemic embolim. In general, cerebral or pulmonary and even symptomatic patients during AF episodes, do not notice their arrhythmia in more than half of the episodes during Holter analysis,[31],[32] thus making it difficult to clinically evaluate the presence and frequency of AF episodes. Asymptomatic arrhythmia does not mean lower risk of thromboembolic episodes and, very often, arrhythmia is diagnosed during or after stroke or transient ischemic attack. Symptomatic paroxistic AF patients present also transient asymptomatic arrhythmia episodes leading to the discussion if anti-arrhythmic drugs used to prevent recurrence actually turn the episodes into asymptomatic.[33] Asymptomatic episodes bring to the discussion of the need for anticoagulation in patients with acute AF reverted to sinus rhythm and for how long this should be maintained.

Final arrhythmia diagnosis is achieved with ECG, as described in the first AF characterization via ECG made by Eintowen in 1906.

2. Atrial flutter

Described in the early 20th Century, atrial flutter, in general, is symptomatic with palpitation. Atrial flutter is less tolerated than AF, frequently causing angina pectoris, HF and hypotension, depending on ventricular rate and function. The risks of thromboembolic events during atrial flutter have not been well studied, but should not be overlooked.[34]

3. AF prevention

Considering the high AF morbidity and mortality, arrhythmia should be prevented. The disease most often associated to AF is hypertension, followed by HF and coronary disease.[35] Measures to prevent or treat such diseases prevent their evolution to AF. Another well-individualized factor is obesity. Obese people have increased left atrium size, especially when associated with any of the above-described diseases.[36] Weight loss is followed by left atrium size decrease.[37] Frequently we do not find a cause for AF, but lately genotypes predisposing to arrhythmia have been described.[38]–[40]

4. Treatment

AF treatment has three objectives: (1) relieve symptoms; (2) prevent HF; and (3) prevent thromboembolism. The methods of treatments are: (1) sinus rhythm reversion through chemical or electrical cardioversion; (2) prevention of recurrences; and (3) in cases of sinus rhythm re-establishment failure, the control of ventricular response associated to chronic anticoagulation must be applied. It is important to stress that the most effective AF therapy, definitively proven by controlled and statistically adequate studies, is anticoagulation to prevent thromboembolism, before or after cardioversion and for patients elected for ventricular response control.

If for any reason patients cannot receive anticoagulants, antiplatelet agents are the alternative. Oral antiplatelet and anticoagulant drugs with adjusted dosage, as compared to placebo, have their efficacy proven to prevent AF embolic events in several meta-analysis trials since the 1980's. The risk reduction for primary prevention was 2.7% per year and for secondary prevention 8.4% per year.[41],[42] The AFFIRM study teaches us that anticoagulation withdrawal in rhythm control trial arms has increased the incidence of thromoboembolic accidents, even in asymptomatic patients in sinus rhythm.[43],[44] Thromboembolic risk is the same for paroxysmal, persistent or permanent AF,[45] therefore AF patients should be anticoagulated in all situations.

When using warfarin, patients must be closely followed due to hemorrhagic complications which to be prevented, require sequential control of prothrombin activity and INR. Regular dietary habits are recommended due to the interaction of warfarin with dark green leafed vegetables. The interacttion of warfarin with other drugs may also be considered and evaluated, as well as different individual responses to anticoagulation treatment related to P450 cytochrome activity. INR should be maintained between the 2 and 3 interval, where the most protective benefits against thromboembolism and lowest hemorrhagic risk are found.[46]

Acording to Go et al.[47] using CHADS 2 risk stratification score, the stroke risk level per 100 person/years is lower using warfarin (Table 2).

Table 2. Chads 2 score stroke risk per 100 person years/on or off warfarin.[47].

| 0 Points: | 0.25 on warfarin; 0.49 no |

| 1 Point: | 0.72 on warfarin; 1.52 no |

| 2 Points: | 1.27 on warfarin; 2.50 no |

| 3 Points: | 2.20 on warfarin; 5.27 no |

| 4 Points: | 2.35 on warfarin; 6.02 no |

| 5–6 Points: | 4.60 on warfarin; 6.88 no |

The ATRIA study and the Euro Heart Survey have reported variables to characterize hemorrhagic risk in patients under warfarin as anemia, renal disease, age > 75 years, previous bleeding, hypertension (Table 3).[48],[49]

Table 3. Hemorrhagic risk is evaluated by the HAS-BLED score.[48].

| Letter | Clinical characteristic | Points awarded |

| H | Hypertension | 1 |

| A | Abnormal renal and liverfunction (1 point each) | 1 |

| S | Stroke | 1 |

| B | Bleeding | 1 |

| L | Labile INRs | 1 |

| E | Elderly (age > 65 years) | 1 |

| D | Drugs or alcohol (1 point each) | 1 |

Maximum score is 9. Hypertension is defined as systolic blood pressure ≥ 160 mmHg. Abnormal kidney function is defined as the presence of chronic dialysis or renal transplantation or serum creatinine ≥ 200 mmol/L. Abnormal liver function is defined as chronic hepatic disease (e.g., cirrhosis) or biochemical evidence of significant hepatic derangement (e.g., bilirubin, 2 × upper limit of normal, in association with aspartate aminotransferase/alanine aminotransferase/alkaline phosphatase, 3 × upper limit normal, etc.). Bleeding refers to previous bleeding history and/or predisposition to bleeding, e.g., bleeding diathesis, anemia, etc. Labile INRs refers to unstable/high INRs or poor time in therapeutic range (e.g., 60%). Drugs/alcohol use refers to concomitant use of drugs, such as antiplatelet agents, non-steroidal anti- inflammatory drugs, or alcohol abuse, etc. INR: ¼ international normalized ratio.

New oral drug therapies, such as direct thrombin inhibitors, dabigatran, and Xa factor inhibitors, such as apixaban, would have, as an advantage, a lower risk profile with no need for periodic control as in the case with warfarin use.[50],[51]

In spite of evidence and recommendations for their use, anticoagulants are underutilized especially in the elderly above 80 years of age and in patients with malignant solid tumors.[52]

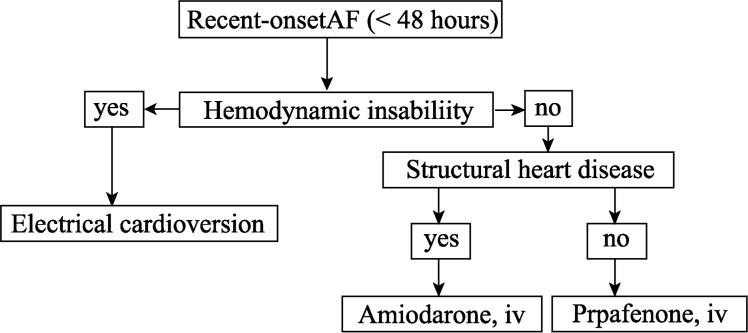

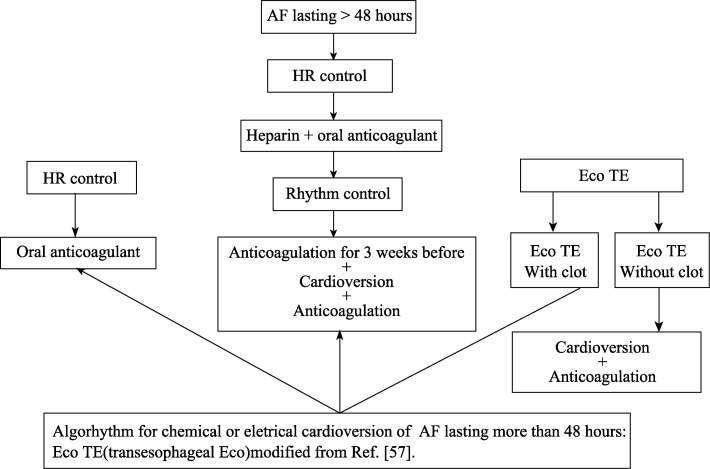

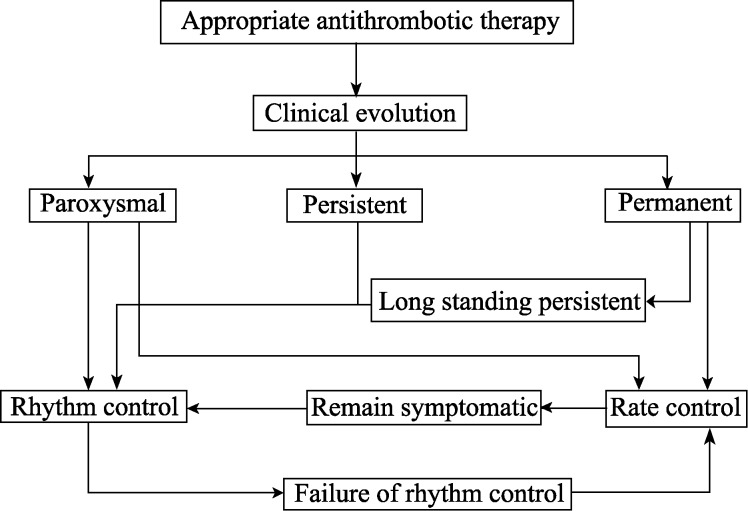

The decision for cardioversion to sinus rhythm, or just controlling ventricular response, should be individually established, taking into account the clinical presentation (paroxystic permanent or persistent), the presence of symptoms, cardioversion risks and the probability of success of maintaining the sinus rhythm after cardioversion, and the willingness of patients to be treated. One should stress that age is not one isolated factor for electric cardioversion failure (Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1. Choice of rate or rhythm control strategies.

Direct current conversion and pharmacological cardioversion of recent- onset Atral Fibrilation in patients considered for pharmacological cardioversion

Figure 2. Decision for cardioversion to sinus rhythm.

AF: Atrial fibrillation; HR: heart rate.

The expectation with cardioversion, in addition to avoiding the use of anticoagulants, was that reversion to sinus rhythm would be advantageous; decreasing symptoms and increasing exercise capacity, decreasing thromboembolic risk and possibly decreasing mortality.[53] Controlled studies have not shown advantages of any approach, at least with regard to survival.[54] The reference study reaching this conclusion was the AFFIRM study,[55] which included more than 4000 patients. However, a most recent analysis of this study has shown that patients in sinus rhythm in any of the arms had better survival rate, indicating that AF is a mortality risk marker. Antiarrhythmic drugs and digitalis increased the risk of death.[56]

Reversion to sinus rhythm may be achieved with drugs or electrical cardioversion. In cases of AF lasting less than 48 hours, previous anticoagulation is not needed, however, when AF lasts longer, or its duration is unknown, patients should be previously anticoagulated for at least 30 days. Chemical reversion may be achieved with intravenous amiodarone, intravenous or oral propafenone. Propafenone should not be used in patients with ventricular disease (Figure 2 ).

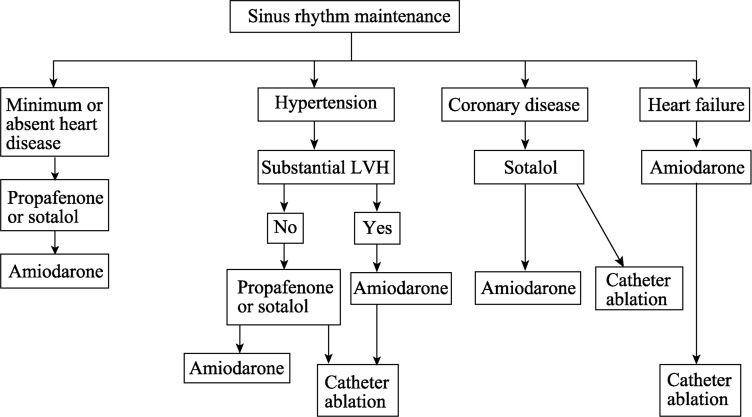

It is clear today that anticoagulants should be maintained even after reversion to sinus rhythm (Figure 3).[57]

Figure 3. Using of antiarrhythmic drugs after reverse to sinus rhythm.

LVH: Left ventricular hypertrophy.

After reversion to sinus rhythm, its maintenance requires the use of antiarrhythmic drugs, (Figure 3). The drugs of choice are those of the IC group (propafenone) and III group (amiodarone, sotalol) from the Vaughn-Williams classification. For patients with structurally normal hearts, propafenone or sotalol is indicated; and for those with systolic dysfunction or ventricular hypertrophy, amiodarone is indicated. One should note that, dronedarone use has been based on studies with approximately 6300 patients.[58] Dronedarone is an antiarrhythmic similar to amiodarone but lacks an iodine moiety. Two studies (EURIDIS and ADONIS)[59],[60] have observed that dronedarone does not improve the results of electrical cardioversion in AF patients and dronedarone is less effective than amiodarone for sinus rhythm reversion. The ATHENA study,[61] including 4,624 older people receiving dronedarone or placebo, has observed longer survival and lower number of hospitalizations in patients receiving the drug. The results suggest antiarrhrythmic drugs may decrease mortality and morbidity in patients with non-permanent AF. On the other hand, the Pallas study, including just permanent AF patients, was interrupted in phase 3 due to the increased number of cardiovascular complications in the dronedarone arm.[62]

According to recent guidelines updates, dronedarone is indicated to decrease hospitalization in paroxysmal AF patients, or after electrical cardioversion (indication II evidence level B). The drug should not be used in patients with HF class IV, if there has been heart decompensation in the last 30 days, or when the ejection fraction is lower than 35%.

In addition to drugs, other triggering factors for arrhythmia, such as alcohol, stress, thyroid diseases, etc., should also be ruled out.

Non-antiarrhythmic drugs, such as angiotensin II converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, aldosterone inhibitors, statins and polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) of the Omega 3 group, may contribute to the maintenance of the sinus rhythm through different mechanisms, but they lack adequate and consistent studies for their application in all patients.[63]

For patients where the option was not to use cardioversion, or when it fails, heart rate is controlled to prevent tachycardiamiopathy. Drugs to be used should be those with specific actions on the atrioventricular node, such as betablockers, calcium channel blockers (verapamil or diltiazem), digoxin or amiodarone. Heart rate control aims at maintaining ventricular rate at rest between 60 to 80 beats per minute and between 90 and 115 beats at moderate exercise.[64]

In the elderly with persistent AF heart rate, control is recommended if patients are asymptomatic (recommendation class I evidence level A of European Guidelines (Figure 4).[65] In situations refractory to heart rate control, atrio ventricular node modification by radiofrequency is indicated.

Figure 4. Choice of antiarrhythmic drug to maintain sinusal rhythm after AF cardioversion.[70].

For patients with Wolf-Parkinson-White (WPW) syndrome developing AF, drugs with more specific action on the anomalous pathway should be used (amiodarone, propafenone or procainamide), however, the first option should be anomalous pathway ablation. For acute AF and WPW patients, the first option is electrical cardioversion, which is safer than drugs.

In 1998, Haissaguerre proposed for the first time the catheter ablation of AF.[66] Since that date, studies have enhanced the technique and tried to compare it to the use of antiarrhythmic drugs. Noheria et al.[67] have published a meta-analysis showing better results with ablation with regard to survival and arrhythmia recurrence. Currently, the ablation is made by electrical insulation of the opening of pulmonary veins in the left atrium eliminating the primary arrhythmia maintenance circuit.

Recent studies have shown that radiofrequency ablation is more effective in maintaining sinus rhythm after drug failure in adults without significant structural heart disease and patients suffering of paroxysmal or permanent non- valvar AF.[68] Thus far, ablation should be reserved for selected groups of patients and be more restricted in the elderly due to the risk of procedure complications. Studies have included paroxystic, symptomatic AF patients with little or no structural heart alteration.

Based on presented information, the Brazilian Society of Cardiac Arrhythmias (SOBRAC) guidelines[69] and recent considerations of European and American guidelines, we have the following approaches for the elderly in AF or flutter.

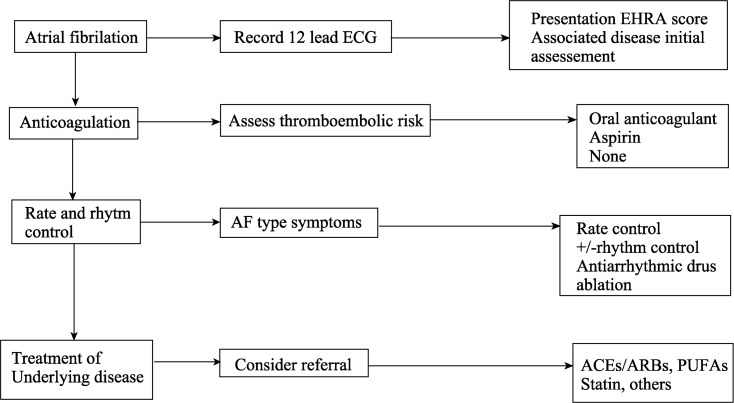

According to the Brazilian Cardiogeriatrics Guidelines,[70] recommendations for treating AF are as follows, (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Sequence of treatment of AF.

ACE: angiotensin converting enzyme; AF: atrial fibrillation; ARB: Angiotensin receptor blocker; ECG: electrocardiogram; PUFA: polyunsaturated fatty acids.[65]

4.1. Anti-thrombotic therapy in AF patients

Class I: (1) anti-thrombotic therapy (INR between 2.0 and 3.0) for undefined time, except if there are contraindications; (2) oral anticoagulant for secondary prevention (acute encephalic accident, transitory ischemic attack, previous systemic embolization) in patients with rheumatic mitral stenosis or metal valvar prosthesis (INR > 2.5), (Evidence Level A); (3) oral anticoagulants for patients with two or more of the following risk factors: age ≥ 75 years, HAS, HF, LV ejection fraction = 35% and Diabetes Melitus, (Evidence Level A); (4) acetylsalicylic acid 81mg to 325 mg to replace oral anticoagulants when they are contraindicated (Evidence Level A); and (5) heparin, preferably of low molecular weight, temporarily used during oral anticoagulation withdrawal periods, such as due to surgical procedures (Evidence Level C).

4.2. Thromboembolism prevention in patients scheduled for electrical cardioversion

Class I: (1) Oral anticoagulation (INR between 2.0 and 3.0) for three weeks before electrical or pharmacological cardioversion in all patients with AF lasting ≥ 48 hours, or when duration is unknown, (Evidence Level B). Patients with metal valvar prosthesis should maintain INR > 2.5. (2) Fractionated heparin administration (unless contraindicated) with initial bolus injection followed by continuous infusion with adjusted dose to prolong activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT) 1.5 to 2 times the control value in AF lasting 48 hours needing immediate cardioversion due to hemodynamic instability. There are still insufficient data to recommend low molecular weight heparin (Evidence Level C).

Class IIA: (1) Trans-esophageal ECG to identify atrial and atrial appendix clots as an alternative to anticoagulation before AF cardioversion (Evidence Level B). (2) If no clots are identified, start fractionated heparin administration with initial bolus injection followed by continuous infusion with adjusted dose to prolong APTT 1.5 to 2 times the control value maintained until oral coagulation with INR higher than 2 is achieved (Evidence Level B). There are still insufficient data to recommend low molecular weight heparin (Evidence Level C). (3) Patients with clots identified by transesophageal echocardiogram should have oral anticoagulation (INR between 2 and 3) three weeks before. (4) Anticoagulation in atrial flutter patients submitted to cardioversion using the same protocol used for AF.

4.3. Anti arrhythmic drugs for pharmacological cardioversion of AF

Class I: (1) Oral or intravenous propafenone for pharmacological AF reversion, in the absence of structural heart disease (Evidence Level A). This drug should be avoided in patients aged above 80 years old. (2) Intravenous amiodarone for pharmacological AF reversion in the presence of moderate or severe ventricular dysfunction (Evidence Level A).

Class II A: (1) Intravenous amiodarone for pharmacological AF reversion in the absence of moderate or severe ventricular dysfunction (Evidence Level A). (2) Single oral 600 mg dose of propafenone for pharmacological paroxysmal or permanent AF reversion outside the hospital, provided the treatment has already been shown to be effective and safe during hospital stay, in patients without sinus node or atrioventricular dysfunction, branch blockade, QT interval prolongation, Brugada syndrome, or structural heart disease. Before starting the antiarrhythmic medication, beta-blocker or non-dihydropiridinic calcium channel blockers should be administered to prevent fast atrial conduction if atrial flutter occurs (Evidence Level C).

Class III: (1) digoxin and sotalol for pharmacological AF reversion (Evidence Level A); (2) Quinidine started outside the hospital for AF pharmacological reversion (Evidence Level B).

5. Electrical cardioversion

Class I: (1) AF with fast ventricular rate without immediate response to pharmacological measures, or followed by myocardial ischemia, hypotension, angina, or HF (Evidence Level C). (2) AF associated to ventricular pre-excitation with very fast tachycardia or hemodynamic instability (Evidence Level B). (3) Very symptomatic AF even without hemodynamic instability. In cases of early AF recurrence, cardioversion should be repeated after the administration of antiarrhythmic drugs (Evidence Level C).

CLASS III: (1) Frequent repetition of electrical cardioversion in patients with relatively short sinus rhythm periods due to AF recurrence, in spite of prophylactic therapy with antiarrhythmic drugs; (2) electrical cardioversion in patients with digitalic intoxication or hypo-potassemia (Evidence Level C).

5.1. Improved electrical cardioversion effectiveness with antiarrhythmic drugs

CLASS II A: (1) Pretreatment with amiodarone, propafenone or sotalol to increase electrical CV success aiming at preventing AF recurrence (Evidence Level C); (2) Prophylactic antiarrhythmic medication before repeating electrical CV in patients with AF recurrence (Evidence Level C).

5.2. Maintenance of sinus rhythm

Class I: (1) Antiarrhythmic drugs to maintain sinus rhythm should not be used in AF patients without risk factors for recurrence and whose triggering factor has been corrected (Evidence Level C); (2) Potentially removable AF causes should be identified and treated before starting the antiarrhythmic treatment (Evidence Level C).

Class II A: (1) Pharmacological therapy to maintain sinus rhythm and prevent tachycardiomiopathy (Evidence Level C); (2) Antiarrhythmic therapy to treat infrequent and well tolerated AF recurrences (Evidence Level C); (3) Outpatient antiarrhythmic therapy for AF patients without heart disease and with good tolerance to the drug used (Evidence Level C); (4) Outpatient propafenone for idiopathic paroxysmal AF patients without heart disease and in sinus rhythm at beginning of treatment (Evidence Level B); (5) Outpatient sotalol in patients with mild or no heart disease, when in sinus rhythm and at risk of paroxysmal AF, if corrected QT interval is lower than 460 ms, plasma electrolytes are normal and in the absence of risk factors for pro-arrhythmic effects (Evidence Level C); and (6) Catheter ablation as alternative to pharmacological therapy to prevent AF recurrences, in symptomatic patients with little or no left atrial overload (Evidence Level C).

5.3. Heart rate control in AF

Class I: (1) Betablockers or non-dihydropiridinic calcium channel blockers (veparamil and diltiazem) in individualized doses for patients without significant structural heart disease, with persistent or permanent AF (Evidence Level B); (2) In the absence of pre-excitation, intravenous administration of betablocker (esmolol, metropolol or propranolol) or non- dihydropiridinic calcium channel blockers (verapamil and diltiazem) to decrease ventricular response in acute AF, with special attention to patients with hypotension or HF (Evidence Level B); (3) Intravenous administration of digitalis or amiodarone to control HR in patients with AF and HF, in the absence of pre-excitation (Evidence Level B); (4) In patients with effort-related AF symptoms, treatment efficacy should be tested during exercises, adjusting drugs in a sufficient dose to maintain HR in physiological levels (Evidence Level C); (5) Digoxin to control heart rate at rest in AF patients with ventricular dysfunction and in sedentary individuals (Evidence Level C).

Class II A: (1) Combination of digoxin and betablockers or non-dihydropiridinic calcium channel blockers to control heart rate at rest and during exercise in AF patients. Drug choice should be individualized and controlled to prevent bradycardia (Evidence Level B). (2) Heart rate control with AV node ablation with implant of permanent pacemaker when pharmacological therapy is not sufficient or is associated to side effects, or in the presence or suspicion of tachycardiamiopathy (Evidence Level B). (3) Intravenous amiodarone to control heart rate in AF patients when other drugs fail or are contraindicated (Evidence Level C).

Class III: (1) Digitalic drugs used as isolated agents to control ventricular response in paroxysmal AF patients (Evidence Level B); (2) Catheter ablation of atrioventricular node without previous drug treatment to control heart rate in AF patients (Evidence Level C); (3) Non-dihydropiridinic calcium channel blockers for patients with decompensated HF (Evidence Level C); and (4) Administration of digitalic or non-dihydropiridinic calcium channel blockers for patients with AF and pre-excitation syndrome (Evidence Level C).

References

- 1.Flegel KM. From delirium cordis to atrial fibrillation: historical development of a disease concept. Ann Intern Med. 1995;122:867–873. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-122-11-199506010-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sabeh MK, MacRae CA. The genetics of atrial fibrillation. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2010;25:186–191. doi: 10.1097/HCO.0b013e3283385734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Falk RH. Atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1067–1078. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200104053441407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Go AS, Hylek EM, Phillips KA, et al. Prevalence of diagnosed atrial fibrillation in Adults. JAMA. 2001;285:2370–2375. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.18.2370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benjamin EJ, Levy D, Vaziri SM, et al. Independent risk factors for atrial fibrillation in a population-based cohort. The Framingham Heart Study. JAMA. 1994;271:840–844. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iguchi Y, Kimura K, Shibazaki K, et al. Annual incidence of atrial fibrillation and related factors in adults. Am J Cardiol. 2010;106:1129–1133. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fuster V, Rydén LE, Cannon DS, et al. ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Atrial Fibrillation. A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 2001 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Atrial Fibrillation) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:854–906. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Diretriz de Fibrilação Atrial da Sociedade Brasileira de Cardiologia. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2003;81(Supl VI):S1–S24. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fuster A, Rydén LE, Asinger RW, et al. ACC/AHA/ESC Guidelines for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;38:1266. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01587-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parkash R, Verma A, Tang ASL. Persistent atrial fibrillation: current approach and controversies. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2010;25:1–7. doi: 10.1097/HCO.0b013e3283336d52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.The SOLVD investigators. Effect of Enalapril on mortality and the development of heart failure in asymptomatic patients with reduced left ventricular ejection fractions. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:685–691. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199209033271003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carson PE, Johnson GR, Dunkman WB, et al. The influence of atrial fibrillation on prognosis in mild to moderate heart failure. The V-heft Studies. The V-heft VA Cooperative Studies Group. Circulation. 1993;87(6 Suppl):VI102–VI110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cobler JL, Williams ME, Greenland P. Thyrotoxicosis in institutionalized elderly Patients with Atrial Fibrillation. Arch Intern Med. 1984;144:1758–1760. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Auer J, Scheibner P, Mische T, et al. Subclinical hyperthyroidism as a risk factor for atrial fibrillation. Am Heart J. 2001;142:838–842. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2001.119370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Furberg CD, Psaty BM, Manolio TA, et al. Prevalence of atrial fibrillation in elderly subjects: The Cardiovascular health study. Am J Cardiol. 1994;74:236–241. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(94)90363-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Braunwald E. Shattuck lecture: Cardiovascular medicine at the turn of the millennium: triumphs, concerns, and opportunities. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1360–1369. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199711063371906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leonard JJ, Shaver J, Thompson M. Left atrial transport function. Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc. 1981;92:133–141. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rahimtoola SH, Ehsani A, Sinno MZ, et al. Left atrial transport function in myocardial infarction. Importance of its booster pump function. Am J Med. 1975;59:686–694. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(75)90229-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Benjamin EJ, Wolf PA, D'Agostino RB, et al. Impact of atrial fibrillation on the risk of death: The framingham heart study. Circulation. 1998;98:946–952. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.10.946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.The solvd investigators studies of left ventricular disfunction effect of enalapril on mortality and the development of heart failure in assymptomatic patientes with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:685–691. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199209033271003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wolf PA, Abbot RD, Kannel WB. Atrial fibrillation as an independent risk factor for stoke. The framingham study. Stroke. 1991;22:983–988. doi: 10.1161/01.str.22.8.983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Predictors of thromboembolism in atrial fibrillation: I. Clinical features of patients at risk. The stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation investigators. Ann Intern Med. 1992;116:1–5. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-116-1-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stollberger C, Chnupa P, Kronik G, et al. Transesophageal echocardiography to asses embolic risk in patients with atrial fibrillation. Ann Intern Med. 1998;128:630–638. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-128-8-199804150-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gage BF, Waterman AD, Shannon W, et al. Validation of clinical classification schemes for predicting stroke: results from the national registry of atrial fibrillation. JAMA. 2001;285:2864–2870. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.22.2864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lip GY, Nieuwlaat R, Pisters R, et al. Refining clinical risk stratification for predicting stroke and thromboembolism in atrial fibrillation using a novel risk factor-based approach: the euro heart survey on atrial fibrillation. Chest. 2010;137:263–272. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.ACTIVE investigators Effect of clopidogrel added to aspirin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Eng J Med. 2009;360:2066–2078. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0901301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Healey J, Hart RG, Pogue J, et al. Risks and benefits of oral anticoagulation compared with clopidogrel plus aspirin in patients with atrial fibrillation according to stroke risk. Stroke. 2008;39:1482–1486. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.500199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ott A, Breteler MM, De Bruyne MC, et al. Atrial fibrillation and dementia in a population based study: The rotterdam study. Stroke. 1997;28:316–321. doi: 10.1161/01.str.28.2.316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Knecht S, Oelschlager C, Duning T, et al. Atrial fibrillation in stroke free patients is associated with memory impairment and hippocampal atrophy. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:2125–2132. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miyasaka Y, Barnes ME, Petersen RC, et al. Risk of dementia in stroke-free patients diagnosed with atrial fibrillation: data from a community-based cohort. Eur Heart J. 2007;28:1962–1967. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Israel CW, Gronefeld G, Ehrlich JR, et al. Long-term risk of recurrent atrial fibrillation as documented by an implantable monitoring device: Implications for optimal patient care. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:47–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Patten M, Maas R, Bauer P, et al. Suppression of paroxysmal atrial tachyarrhythmias—Results of the SOPAT trial. Eur Heart J. 2004;25:1395–1404. doi: 10.1016/j.ehj.2004.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Page RL, Tilsch TW, Conolly SJ, et al. Asymptomatic or “Silent”atrial fibrillation. frequency in untreated patients and patients receiving azimilide. Circulation. 2003;107:1041–1045. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000051455.44919.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lanzarotti CJ, Olshansky B. Thromboembolism in chronis atrial flutter: Is the risk underestimated. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;30:1506–1511. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(97)00326-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lloyd-Jones DM, Wang TJ, Leip EP, et al. Lifetime risk for development of atrial fibrillation: The Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2004;110:1042–1046. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000140263.20897.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thomas WJ, Helen P, Daniel L, et al. Obesity and the risk of new-onset atrial fibrillation. JAMA. 2004;292:2471–2477. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.20.2471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Alaud-din A, Meterissian S, Lisbona R, et al. Assessment of cardiac function in patients who were morbidly obese. Surgery. 1990;108:809–818. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brugada R, Tapscott T, Czernuszewicz GZ, et al. Identification of a genetic locus for familial atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:905–911. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199703273361302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen YH, Xu SJ, Bendahhou S, et al. KCNQ1 gain-of- function mutation in familial atrial fibrillation. Science. 2003;299:251–254. doi: 10.1126/science.1077771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lai LP, Su MJ, Yeh HM, et al. Association of the human mink gene 38G allele with atrial fibrillation: evidence of possible genetic control on the pathogenesis of atrial fibrillation. Am Heart J. 2002;144:485–490. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2002.123573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hart RG, Benavente O, McBride R, et al. Antithrombotic therapy to prevent stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 1999;131:492–501. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-131-7-199910050-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hart RG, Pearce LA, Aguilar MI. Meta-analysis: antithrombotic therapy to prevent stroke in patients who have nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:857–867. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-12-200706190-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Corley SD, Epstein AE, DiMarco JP, et al. Relationships between sinus rhythm, treatment, and survival in the AFFIRM study. Circulation. 2004;109:1509–1513. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000121736.16643.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hohnloser SH, Pajitnev D, Pogue J, et al. Incidence of stroke in paroxysmal versus sustained atrial fibrillation in patients taking oral anticoagulation or combined antiplatelet therapy: an ACTIVE W Substudy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:2156–2161. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.07.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Albers GW, Dalen JE, Laupacis A, et al. Antithrmbotic therapy in atrial fibrillation. Chest. 2001;119(Suppl 1):194S. doi: 10.1378/chest.119.1_suppl.194s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hylek EM, Skates SJ, Sheehan MA, et al. An analysis of the lowest effective intensity of prophylactic anticoagulation for patients with non-rheumatic atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:540–546. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199608223350802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Go AS, Hylek EM, Chang Y, et al. Anticoagulation therapy for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation: How well do randomized trials translate into clinical practice? JAMA. 2003;290:2685–2692. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.20.2685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pisters R, Lane DA, Nieuwelaat R, et al. A novel user- friendly score (HAS-BLED) to assess one-year risk of major bleeding in atrial fibrillation patients: the Euro Heart Survey. Chest. 2010;138:1093–1100. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-0134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fang MC, Go AS, Chang Y, et al. A new risk scheme to predict warfarin-associated hemorrhage: The ATRIA (Anticoagulation and Risk Factors in Atrial Fibrillation) Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:395–401. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.03.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Armaganijan L, Eikelboom J, Healey JS, et al. New pharmacotherapy for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation. Adv Ther. 2009;26:1058–1071. doi: 10.1007/s12325-009-0084-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wann S, Curtis AB, Ellenbogen KA, et al. Recommendation for emerging antithrombotic agents 2011 focused update recommendation comments. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:1330–1337. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Marcucci M, Iorio A, Nobili A, et al. Factors affecting adherence to guidelines for antithrombotic therapy in elderly patients with atrial fibrillation admitted to internal medicine wards. Eur J Inten Med. 2010;21:516–523. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2010.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Saxonhouse SJ, Curtis AB. Risks and benefits of rate control versus maintenance of sinus rhythm. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91:27D–32D. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(02)03376-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Denus S, Sanoski CA, Carlsson J, et al. Rate vs rhythm control in patients with atrial fibrillation: A meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:258–262. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.3.258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wyse DG, Waldo AL, Dimarco JP, et al. A comparison of rate control and rhythm control in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Eng J Med. 2002;347:1825–1833. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.The AFFIRM investigators Relationships between sinus rhythm, treatment, and survival in the atrial fibrillation follow-up investigation of rhythm management (AFFIRM) study. Circulation. 2004;109:1509–1513. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000121736.16643.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zimerman LI, Fenelon G, Martinelli Filho M, et al. Sociedade brasileira de cardiologia. diretrizes brasileiras de fibrilação atrial. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2009;92(6 Supl. 1):S1–S39. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Duray GZ, Ehrlich JR, Hohnloser SH. Dronedarone: A novel antiarrhythmic agent for the treatment of atrial fibrillation. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2010;25:53–58. doi: 10.1097/HCO.0b013e32833354e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Singh BN, Connolly SJ, Crijns HJ, et al. Dronedarone for maintenance of sinus rhythm in atrial fibrillation or flutter. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:987–999. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa054686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Touboul P, Brugada J, Capucci A, et al. Dronedarone for prevention of atrial fibrillation: A dose-ranging study. Eur Heart J. 2003;24:1481–1487. doi: 10.1016/s0195-668x(03)00321-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hohnloser SH, Crijns HJ, van Eickels M, et al. Effect of dronedarone on cardiovascular events in atrial fibrillation. N Eng J Med. 2009;360:668–678. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0803778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wood S. Dronedarone trial suspended due to CV events in permanent atrial fibrillation Sanofi provides Multaq phase III B PALLAS trial uptodate (press release) http://www.theheart.org/article/1251405.do (accessed on July 7, 201)

- 63.Savelieva I, Kakouros N, Kourliouros A, et al. Upstream therapies for management of atrial fibrillation: Review of clinical evidence and implications for European Society of Cardiology Guidelines. Part I: Primary prevention. Europace. 2011;13:308–328. doi: 10.1093/europace/eur002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fuster V, Ryden LE, Cannom DS, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA/ HRS Focused Update incorporated into the ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 Guidelines for Management of Patients With Atrial Fibrillation (Updating the 2006 Guideline) A Report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2011;123:E269–E367. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e318214876d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Camm JA, Kirchhof P, Lip GYH, et al. Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation the task force for the management of atrial fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Europace. 2010;12:1360–1420. doi: 10.1093/europace/euq350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Haissaguerre M, Jais P, Shah DC, et al. Spontaneous initiation of atrial fibrillation by ectopic beats originating from the pulmonary veins. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:659–666. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199809033391003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Noheria A, Kumar A, Wylie JV, Jr, et al. Catheter ablation vs antiarrhythmic drug therapy for atrial fibrillation: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:581–586. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.6.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pinter A, Dorian P. New Approaches to Atrial Fibrillation Management: Treat the Patient, not the ECG. Cardiovasc Ther. 2010;5:302–310. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-5922.2010.00135.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zimerman LI., Fenelon G, Filho MM, et al. Diretrizes brasileiras de fibrilação atrial. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2009;92(6 Supl 1):S1–S39. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gravina CF, Rosa RF, Franken RA, et al. Sociedade brasileira de cardiologia. II diretrizes brasileiras em cardiogeriatria. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2010;95(3 Supl. 2):S1–S112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]