Abstract

Background

Resistance to chemotherapy is a major limitation in the treatment of head and neck squamous cell carcinomas (HNSCCs), accounting for high mortality rates in patients. Here, we investigated the role of replication protein A (RPA) in cisplatin and etoposide resistance.

Methods

We used 6 parental HNSCC cell lines. We also generated 1 cisplatin-resistant progeny subline from a parental cisplatin-sensitive cell line, to examine cisplatin resistance and sensitivity with respect to RPA2 hyperphosphorylation and cell-cycle response.

Results

Cisplatin-resistant HNSCC cell levels of hyperphosphorylated RPA2 in response to cisplatin were 80% to 90% greater compared with cisplatin-sensitive cell lines. RPA2 hyperphosphorylation could be induced in the cisplatin-resistant HNSCC subline. The absence of RPA2 hyperphosphorylation correlated with a defect in cell-cycle progression and cell survival.

Conclusion

Loss of RPA2 hyperphosphorylation occurs in HNSCC cells and may be a marker of cellular sensitivities to cisplatin and etoposide in HNSCC.

Keywords: replication protein A (RPA), phosphorylation, cisplatin, etoposide, cell cycle

The DNA crosslinking agent cisplatin is an extensively used chemotherapeutic in the treatment of head and neck cancer.1 In addition, etoposide, a topoisomerase II inhibitor, has shown to be effective in recurrent and metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC).2 However, resistance and consequent failure of chemotherapy is a complex problem that is a major limitation of cisplatin- and etoposide-based therapies. Therefore, understanding the molecular mechanisms of chemotherapy resistance caused by these drugs will be important in the development of more efficacious therapies.

Etoposide and cisplatin act on DNA with distinctly different mechanisms, although the final outcome of both treatments induces DNA lesions that block replication and stall replication forks. Activated by etoposide- and cisplatin-induced replication stress, the phosphoinositide 3-kinase–related protein kinase, ataxia–telangiectasia mutated and RAD3-related (ATR), initiates a signal transduction cascade that regulates replication and cell-cycle transitions.3 To ensure genomic integrity, ATR suppresses replication and prevents entry into mitosis in the presence of DNA damage.4,5 In addition, ATR functions at the site of the DNA lesion or stalled replication fork by stabilizing the fork and promoting fork recovery.6,7 One ATR substrate that may be involved in maintaining fork integrity is replication protein A (RPA).

Originally identified as a single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) binding protein required for DNA replication, RPA is now known to be essential for most aspects of DNA metabolism, including initiating DNA damage checkpoint signaling and repair of DNA damage.8–12 RPA mutations in yeast suppress double-stranded DNA break–induced G2/M arrest, and heterozygous RPA mutations in mice lead to gross chromosomal rearrangements and cancer.13,14 In humans, loss of the chromosomal region containing RPA70 has been associated with numerous types of cancer, including head and neck and oral squamous cell carcinoma cancers.15,16

After DNA damage, including cisplatin- and etoposide-induced damage, RPA is hyperphosphorylated on the N-terminus of RPA2.17–19 Differences in the phosphorylation status of RPA2 have been shown to modulate RPA function in DNA replication, DNA repair, and cell-cycle control.20,21 For example, RPA2 is phosphorylated at serine (Ser)23 and Ser29 during the course of the cell cycle in the G1/S transition, G2, and mitosis. 22 Upon DNA damage, RPA2 becomes hyperphosphorylated at potentially 9 sites, including Ser4, Ser8, Ser11, Ser12, Ser13, threonine (Thr)21, Ser23, Ser29, and Ser33.23 Phosphorylation of Ser4 and Ser8 is considered to be a marker for the hyperphosphorylated form of RPA2, given that separation by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) revealed that phosphorylation of these 2 sites is observed only in the band of slowest motility among a set of at least 4 characterized phosphorylative forms of RPA2. This suggests that the phosphorylation of Ser4 and Ser8 acts as a sensitive and specific reporter of DNA damage induced by genotoxic agents.24–26 Hyperphosphorylation of RPA2 likely plays a role in regulating the interaction of RPA with DNA and with other proteins involved in DNA replication and repair. For example, equilibrium DNA binding studies have shown that unphosphorylated RPA and hyperphosphorylated RPA show no difference in ssDNA binding activity for pyrimidine-rich ssDNA; however, RPA hyperphosphorylation results in a decreased affinity for purine-rich ssDNA and duplex substrates.27 Hyperphosphorylated RPA shows a decreased interaction with p53, DNA polymerase alpha, DNA-dependent protein kinase (DNA-PK), and ataxia-telangiectasia mutated kinase (ATM), but displays unchanged interactions with XPA and Rad52.27–29 In ultraviolet light–irradiated cells, hyperphosphorylation of RPA2 is associated with the cessation of cell-cycle progression and a decrease in replication activity.20,30 This is supported by the observation that a transiently expressed RPA2 hyperphosphorylation mimetic does not associate with replication foci but supports RPA association with damage repair foci in vivo.21 Combined, these data suggest that RPA2 hyperphosphorylation negatively regulates replication, thereby allowing DNA repair to occur.18

Here, we investigated the role of RPA in mediating survival to cisplatin and etoposide. We compared the cellular response to hyperphosphorylate RPA2 in HNSCC cell lines with distinct differences in cisplatin sensitivity. We were also able to correlate hyperphosphorylation of RPA2 with cisplatin and etoposide sensitivities, suggesting the hyperphosphorylation of RPA2 is predictive of cell survival after cisplatin and etoposide treatment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Lines

All cells were maintained at 37°C and 5% CO2 in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Hyclone, Logan, UT), 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 µg/mL streptomycin. The oral squamous cell carcinoma cell lines established at the University of Michigan—UMSCC-10B, UMSCC-17B, UMSCC-23, UMSCC-38, UMSCC-74B, and UMSCC-8131—were generously provided by Dr. Thomas Carey (University of Michigan). The cisplatin-resistant UMSCC-74B200 cell line was created by the selection of UMSCC-74B cells that survived successive rounds (60 µM, 100 µM, and 200 µM) of 3-hour cisplatin (Acros Organics, Morris Plains, NJ) exposures. The time between exposures was approximately 6 weeks.

Cisplatin–DNA Adduct Formation

In all, 4.5 × 106 cells of each UMSCC-38 and UMSCC-74B cell line were left untreated or treated with 20 µM cisplatin for 3 hours and incubated in fresh medium for an additional 24 hours. DNA was isolated using Trizol (Invitrogen) in accord with the manufacturer’s instructions. Samples were dissolved in an equal volume of 5% nitric acid and 30% H2O2, and were heated in a microwave for 20 seconds. After cooling, the solution was diluted with 4.2 mL reagent-grade water and analyzed for platinum content on a Platform XS inductively coupled plasma–mass spectrometer (ICP-MS; GV Instruments, Manchester, UK).

Cisplatin Cytotoxicity Assay

ID50 (ie, the infectious dose to 50% of exposed individuals) cisplatin concentrations in UMSCC-38 and UMSCC-74B cells in response to cisplatin treatment were determined by using the Vybrant Cell Metabolic Assay Kit (Invitrogen). This assay is based on the reduction of permeable C12-resazurin to the fluorescent resorufin by the mitochondria of viable cells. The staining procedure was performed in accord with the manufacturer’s protocol. Cells were incubated with 10 µmol C12-resazurin in PBS at 37°C for 15 minutes. Adherent cells were trypsinized, combined with the nonadherent cells, and were collected by centrifugation. Pellets were resuspended in PBS, and were analyzed by a fluorescent-activated cell sorting flow cytometer (FACSArray; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA); data were quantified with the BD FACSArray System software.

Immunoblotting

To prepare cell lysates, cultured cells were washed in PBS and were resuspended for 10 minutes on ice in cell lysis buffer (0.5% Triton X-100, 50 mM Tris-HCl, [pH 7.5], 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% Nonidet P-40, 10 mM NaF, 10 mM β-glycerophosphate, 1 mM Na3VO4, and protease inhibitors). Cell lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes. Membranes were immunoblotted using the following primary antibodies: RPA2, PS4/S8–RPA2 (Bethyl Laboratories, Montgomery, TX), and Actin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). Secondary antibodies were Alexa Fluor 680–conjugated anti-rabbit (Invitrogen), DyLight 800-conjugated anti-mouse (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), or horseradish peroxidase–conjugated antibodies (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ). Blots were visualized using infrared fluorescence (LICOR, Lincoln, NE) or chemiluminescence.

Flow Cytometry Analyses

To analyze the incorporation of the thymidine analogue bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) into newly synthesized DNA, cells were pulse labeled with 10 mM BrdU for 1 hour, and were further processed as previously described.32 Ten thousand cells per sample were analyzed on a FACSArray cytometer (BD Biosciences). Cell doublets and clusters were gated from the analysis using doublet discrimination (forward scatter pulse height × pulse width). For analyses of cell-cycle progression, cells were treated with etoposide (Sigma) or cisplatin, and were fixed in 70% ethanol overnight; treated cells were then washed and subsequently incubated in 50 µg/mL propidium iodide (PI) and 100 µg/mL RNase A for 30 minutes. Data were quantified using ModFitLT (Verity Software House, Topsham, ME), and were visualized using WinList (Verity Software House).

Clonogenic Assay

The effects of cisplatin and etoposide on the survival and proliferation of UMSCC-38, UMSCC-74B, and UMSCC-74B200 cells were determined by clonogenic assay. Cells were seeded into 6-well plates at a density of 200 cells per well. After 24 hours, cells were exposed to different concentrations of both drugs (0, 1.25, 2.5, 5, 10, 20 µM) for 2 hours (etoposide) and 3 hours (cisplatin) followed by incubation for another 9 days. Cells were then fixed in 1% glutaraldehyde for 30 minutes, stained with 5% crystal violet, and colonies of >50 cells were counted.

RESULTS

RPA2 Is Hyperphosphorylated after Cisplatin Exposure in Cisplatin-Resistant HNSCC Cells

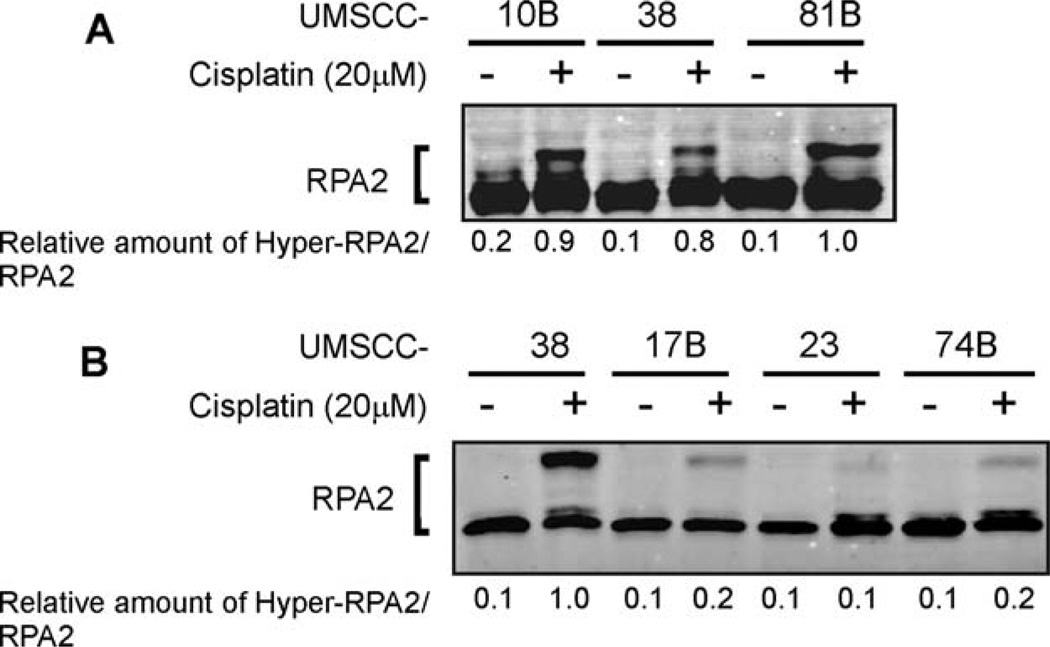

Three squamous cell carcinoma cell lines previously shown to be sensitive (UMSCC-17B, −23, and −74B) and three shown to be resistant (UMSCC-38, −10B, and −81A) to cisplatin were tested for their ability to hyperphosphorylate RPA2 after cisplatin treatment.33,34 The 3 cisplatin-resistant cell lines generated comparable levels of RPA2 hyperphosphorylation (Figure 1A). The UMSCC-38 cisplatin-resistant cell line was then used to compare RPA2 phosphorylation with the 3 cisplatin-sensitive cell lines. After cisplatin treatment, RPA2 phosphorylation in the cisplatin-sensitive UMSCC-17B, −23, and −74B cells was considerably less (23%, 7%, and 16%, respectively) compared with UMSCC-38 cells (Figure 1B). The decreased amount of RPA2 phosphorylation in the UMSCC-17B, −23, and −74B cells correlated with a hypersensitivity to cisplatin compared with UMSCC-38, −10B, and −81A cells. Based on previously published results UMSCC-38, −10B, and −81A cells have an ID50 of 60.0, 23.7, and 17.3 µM compared with 4.0, 3.2, and 4.8 µM for UMSCC-17B, −23, and −74B cells, respectively.33,34

FIGURE 1.

RPA2 phosphorylation in response to cisplatin treatment. (A) The cisplatin-resistant HNSCC cell lines UMSCC-10B, −38, and −81 were exposed to 20 µM cisplatin for 3 hours, and were cultured for an additional 24 hours in fresh medium. Protein lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE, were blotted onto PVDF membranes, and were immunoblotted with RPA2 antibodies. The phosphorylated and unphosphorylated RPA2 levels were quantitated with NIH image software. The numbers represent the relative amounts of phosphorylated RPA2 to RPA2, normalized to the sample with the highest amount of phosphorylated RPA2. (B) The cisplatin-sensitive HNSCC cell lines UMSCC-17B, −23, and −74B and the cisplatin-resistant HNSCC cell line UMSCC-38 were treated and analyzed as described in A. Note the differences in the migration pattern between UMSCC-38 cells in A and B are caused by differences in the separation time during electrophoresis and the amount of total loaded protein. Abbreviations: RPA, replication protein A; HNSCC, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma; UMSCC, squamous cell carcinoma cell lines established at the University of Michigan; SDS-PAGE, sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis; PVDF, polyvinylidene difluoride; NIH, National Institutes of Health.

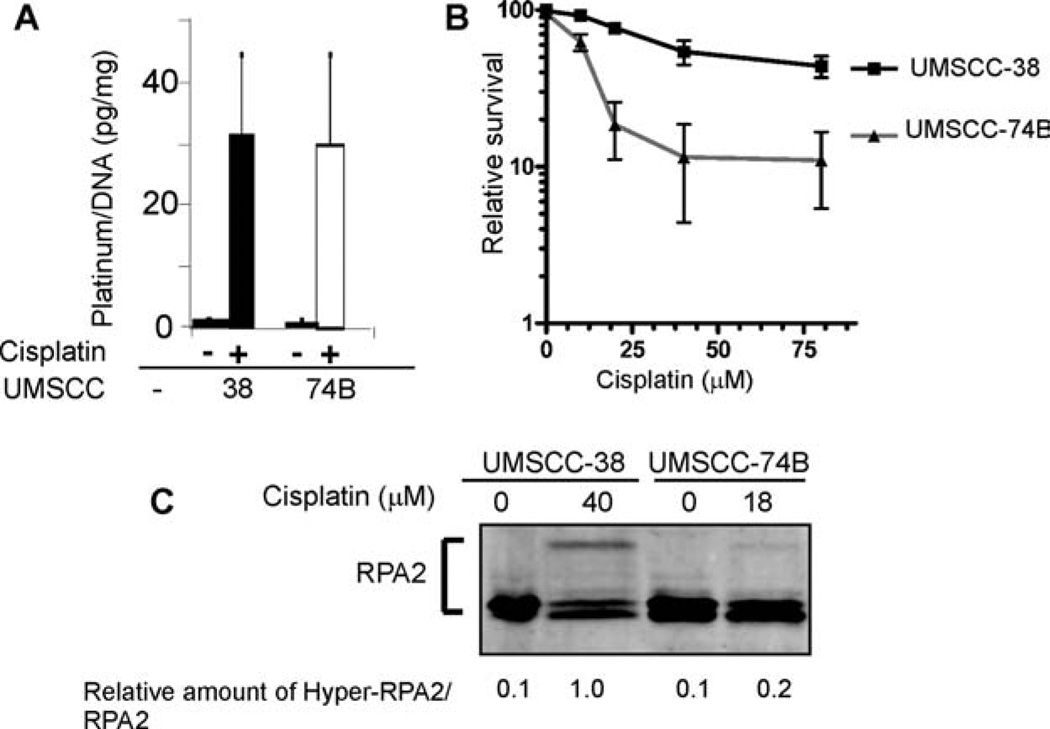

We chose UMSCC-38 cells as a representative for the cisplatin-resistant cell lines and UMSCC-74B cells as a representative for the cisplatin-sensitive cell lines for further analyses. Differences in cisplatin–DNA adduct formation have been previously observed in cells that display varying cisplatin sensitivities.35 To verify that the observed differences in the hyperphosphorylation of RPA2 in response to cisplatin exposure were not caused by differences in cisplatin–DNA adduct formation, we assessed DNA platinum content in UMSCC-38 and UMSCC-74B cells by ICP-MS. No differences in platinum content were observed between the 2 cell lines (Figure 2A). To determine whether hyperphosphorylation of RPA2 in UMSCC-74 cells was inhibited as the result of a lethal dose of cisplatin, we treated both cell lines with equitoxic cisplatin concentrations based on their respective ID50 values (Figure 2B). The level of hyperphosphorylation of RPA2 was strongly reduced in UMSCC-74B cells treated with 18 µM cisplatin compared with the level of hyperphosphorylation in UMSCC-38 cells treated with 40 µM cisplatin, indicating the loss of RPA2 phosphorylation did not stem from a toxic dose of cisplatin (Figure 2C). Taken together, these data indicate that the observed differences in the hyperphosphorylation of RPA2 between cisplatin-resistant and -sensitive UMSCC cell lines in response to cisplatin exposure are not caused by differences in the amount of DNA-adduct formation or relative cellular toxicity, and are consistent with differences in the DNA damage response to cisplatin. We chose 20 µM as the cisplatin concentration for all subsequent experiments, given that this is the approximate ID50 of UMSCC-74B cells.

FIGURE 2.

Comparison of cisplatin adduct formation and cell viability as a function of hyperphosphorylation of RPA2 in HNSCC cells. (A) Detection of cisplatin adducts in genomic DNA of UMSCC-38 and UMSCC-74B cells after treatment with 20 µM cisplatin for 3 hours. DNA samples were isolated, and samples were analyzed for platinum content by ICP-MS. (B) Survival of UMSCC-38 and UMSCC-74B cells as measured by resazurin reduction after treatment with a range of concentrations of cisplatin (10–80 µM). Relative survival for each cell line ± SD was normalized to the value of that cell line without treatment. (C) Hyperphosphorylation of RPA2 in HNSCC cell lines after cisplatin treatment, using equitoxic doses as calculated in B. The numbers are relative amounts of phosphorylated RPA2 normalized to the amount of phosphorylated RPA2 of the cisplatin-treated UMSCC-38 samples. Abbreviations: RPA, replication protein A; HNSCC, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma; UMSCC, squamous cell carcinoma cell lines established at the University of Michigan; ICP-MS, inductively coupled plasma–mass spectrometer.

Hyperphosphorylation of RPA2 in Response to Etoposide Treatment Is Sustained in Cisplatin-Resistant UMSCC-38 Cells

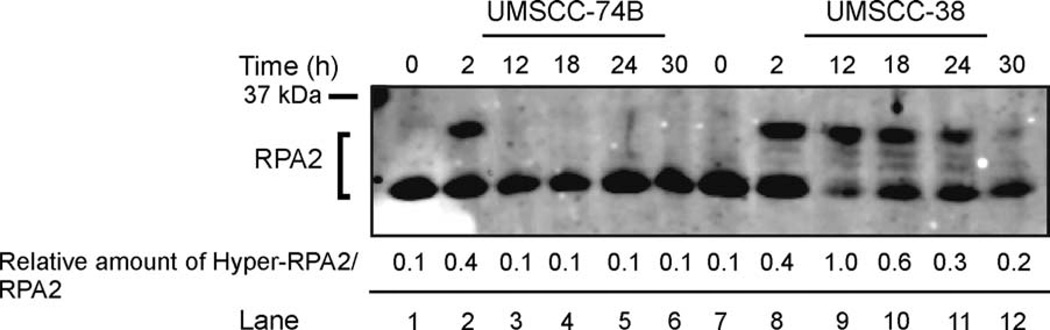

The use of the topoisomerase II inhibitor etoposide has been suggested as salvage therapy in advanced HNSCC if first-line chemotherapeutics fail.2 Based on the observation that RPA2 is hyperphosphorylated in the presence of etoposide,36 and that the cisplatin-resistant UMSCC-38 cells showed increased hyperphosphorylation of RPA2 in the presence of cisplatin over the cisplatin-sensitive UMSCC-74B cells, we next tested etoposide-induced hyperphosphorylation of RPA2 in both cell lines (see Figure 3). Cisplatin-sensitive UMSCC-74B cells and UMSCC-38 cells hyperphosphorylated RPA2 immediately after a 2-hour exposure to etoposide, with only a 2% difference in phosphorylation levels, indicating activation of the DNA damage response in both cell lines (Figure 3, lane 2). This is consistent with sequence analysis data that identify non-mutated RPA2 sequences in both cell lines (data not shown). However, whereas UMSCC-38 cells showed sustained hyperphosphorylation of RPA2 up to 24 hours after recovery from etoposide treatment, RPA2 phosphorylation levels in the UMSCC-74B cells decreased to 3% at 12 hours after recovery (Figure 3, lanes 3 and 9–11). The ability of RPA2 to be markedly phosphorylated in both cisplatin-resistant and cisplatin-sensitive cell lines after etoposide treatment suggests that the DNA damage response pathways are activated; however, the UMSCC-74B cells are not as capable of sustaining a DNA damage response.

FIGURE 3.

Comparison of hyperphosphorylation of RPA2 in response to etoposide treatment in cisplatin-resistant and cisplatin-sensitive HNSCC cell lines. Cells were harvested after treatment of etoposide at 0 hours (lanes 1 and 7); 2 hours (lanes 2 and 8); or at 12,18, 24, and 30 hours’ recovery after a 2-hour exposure to etoposide (lane pairs 3 and 9, 4 and 10, 5 and 11, and 6 and 12, respectively). Cell lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with RPA2 antibodies. The numbers are relative amounts of phosphorylated RPA2 normalized to the amount of phosphorylated RPA2 of the UMSCC-38 sample at 12 hours. Abbreviations: RPA, replication protein A; HNSCC, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma; UMSCC, squamous cell carcinoma cell lines established at the University of Michigan; SDS-PAGE, sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis.

Hyperphosphorylation of RPA2 Is Critical to S-Phase Progression after Exposure to Cisplatin and Etoposide

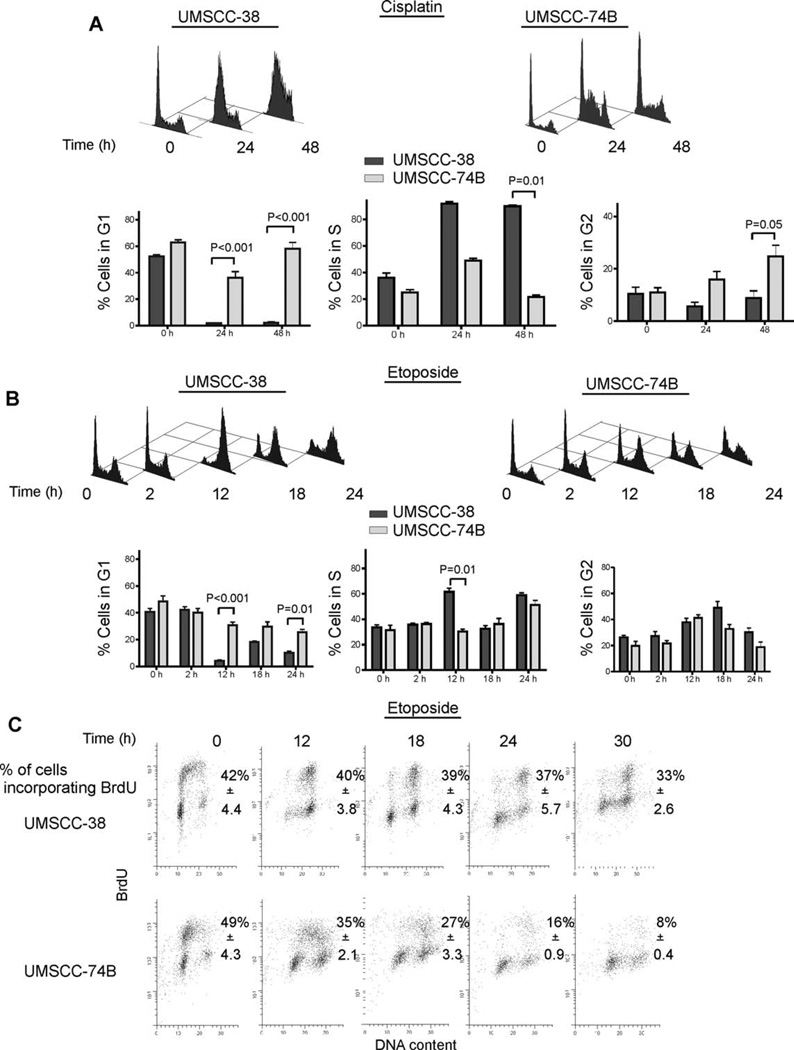

ATR-deficient cells fail to continue DNA synthesis after treatment with cisplatin or mitomycin C, entering S-phase stasis.37 To test whether phosphorylation of RPA2 would be required to overcome cisplatin- and etoposide-induced replication block we treated cells with cisplatin and etoposide and analyzed cell-cycle progression. Cell-cycle analyses of UMSCC-38 and UMSCC-74B cells revealed that after cisplatin exposure, the vast majority of cisplatin-resistant UMSCC-38 cells started accumulating in early S phase and progressed to late S phase 24 and 48 hours, respectively, after cisplatin treatment (Figure 4A). In contrast, a subpopulation of cisplatin-sensitive UMSCC-74B cells initially accumulated in early S phase 24 hours after cisplatin exposure, but appeared to either continue to progress through the cell cycle unimpeded or were unable to continue DNA replication and essentially halted cell-cycle progression (Figure 4A).

FIGURE 4.

Cell-cycle analysis of cisplatin- and etoposide-treated HNSCC cell lines. (A) Flow cytometry analysis of UMSCC-38 and UMSCC-74B cells at 0, 24, and 48 hours after treatment with 20 µM cisplatin for 3 hours. Representative flow cytometry images are shown for A and B. Fixed cells were stained with PI and the percentages of cells in G1, G2, and S phases were calculated for A and B. Error bars indicate SEs (n = 3). p values were calculated using an unpaired, 2-tailed t test. (B) Analysis of UMSCC-38 and UMSCC-74B cells at 0, 2, 12, 18, and 24 hours after treatment with 20 µM etoposide for 2 hours. (C) A measurement of BrdU incorporation in UMSCC-38 and UMSCC-74B cells at 0, 12, 18, 24, and 30 hours after treatment with 20 µM etoposide for 2 hours. The percentage of BrdU incorporated cells is listed. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments for the PI staining and 2 independent experiments for the BrdU incorporation ± SD. Abbreviations: HNSCC, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma; UMSCC, squamous cell carcinoma cell lines established at the University of Michigan; PI, propidium iodide; BrdU, bromodeoxyuridine.

After etoposide exposure, UMSCC-38 cells showed an increased late S phase and G2/M accumulation at 12 hours of recovery, with progression through G2/M phase and an increased accumulation in G1 at 18 hours. In contrast, UMSCC-74B cells exposed to etoposide did not accumulate in late S and G2 phase and appeared to stop cycling all together (Figure 4B). To identify whether both cell lines were continuing to replicate through etoposide-induced DNA damage, we analyzed the incorporation of BrdU into newly synthesized DNA (Figure 4C). The UMSCC-38 cells showed both increased numbers of cells at the G2/M border and high amounts of BrdU incorporation in late S phase 12 hours after etoposide treatment. At 18 hours, UMSCC-38 cells continued to replicate and actively cycled through mitosis to G1 (Figure 4C). Interestingly, BrdU incorporation in UMSCC-74B cells rapidly decayed between 12 and 30 hours, indicating UMSCC-74B cells did not continue to progress through the cell cycle but instead arrested in G1, S, and G2 phases of the cell cycle. Taken together, our results provide evidence that hyperphosphorylation of RPA2 is associated with the cellular ability to continue progression of the cell cycle in the presence of cisplatin- and etoposide-induced DNA damage.

UMSCC-74B Cells Selected for Resistance to Cisplatin Show Increased RPA2 Hyperpho-sphorylation and Are Cross-Resistant to Etoposide

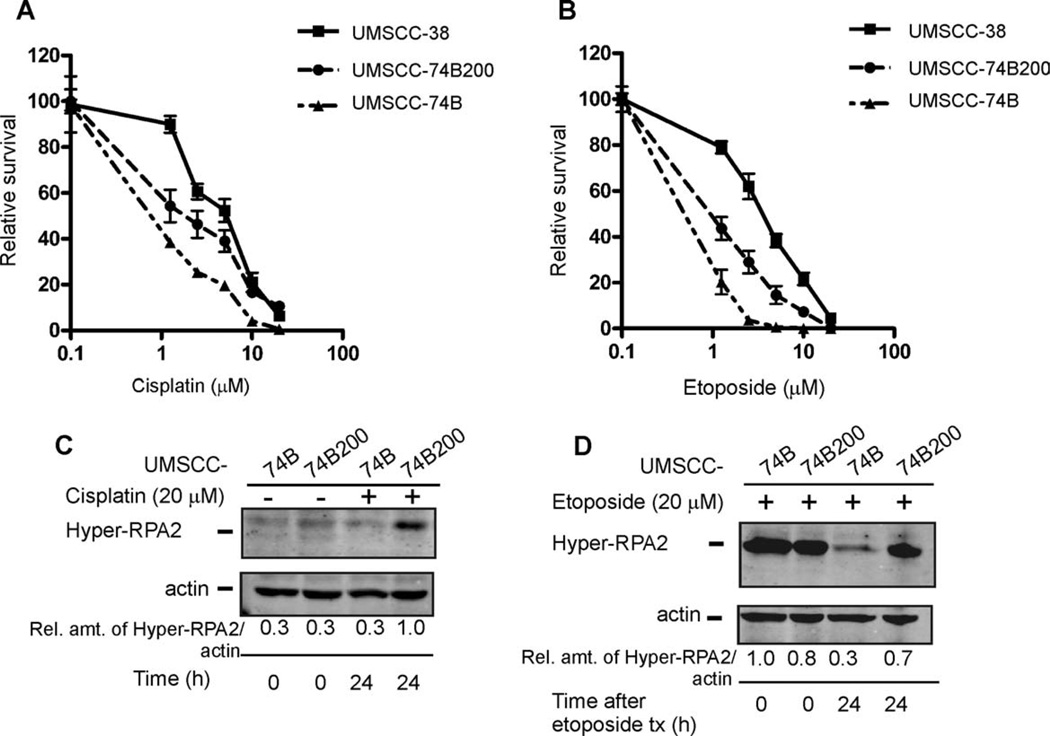

Our data indicated a positive correlation between the ability to efficiently hyperphosphorylate RPA2 and cellular sensitivity to both cisplatin and etoposide in HNSCC. To further validate this hypothesis, we exposed cisplatin-sensitive UMSCC-74B cells to gradually increasing concentrations of cisplatin. Cells that survived the drug treatments over an 18-week period were propagated to form the UMSCC-74B200 subline. We then used the clonogenic survival assay to test sensitivities of the UMSCC-74B200 subline, the respective parent cell line, UMSCC-74B, and the cisplatin-resistant UMSCC-38 cell line to cisplatin and etoposide. UMSCC-74B200 cells displayed increased cisplatin and etoposide resistance compared with the original UMSCC-74 cells. The UMSCC-74B200 subline presented an intermediate resistance to cisplatin and etoposide exposure compared with that of the cisplatin-resistant UMSCC-38 cell line (Figures 5A and 5B). We tested whether the increased drug resistance of the UMSCC-74B200 cells correlated with an enhanced ability to hyperphosphorylate RPA2. After cisplatin treatment, there was a nearly 60% increase in RPA2 phosphorylation levels in UMSCC-74B200 cells compared with that of UMSCC-74B cells (Figure 5C; compare lanes 3 and 4). The UMSCC-74B200 cells were also able to sustain 60% higher levels of hyperphosphorylated RPA2 compared with UMSCC-74B cells at 24 hours after etoposide exposure (Figure 5D). Taken together, these results are indicative of a strong correlation between the ability to efficiently hyperphosphorylate and to sustain hyperphosphorylation of RPA2 in response to cisplatin and etoposide exposure and the cellular sensitivity to the respective drugs.

FIGURE 5.

Comparison of clonogenic survival and the hyperphosphorylation response of RPA2 in cisplatin-resistant and cisplatin-sensitive cell lines. (A and B) Clonal survival of cisplatin (A) and etoposide (B) treated UMSCC-74B, UMSCC-74B200, and UMSCC-38 cells. The cloning efficiency of untreated cells (control) was set at 100%, and the cloning efficiency of treated cells was expressed as a fraction of the control value. Values are from 1 representative experiment performed in triplicate, and the mean value was used for statistical analyses. (C) Western blot of hyperphosphorylation of RPA2 at 0 and 24 hours after a 3-hour treatment of 20 µM cisplatin. The numbers for C and D represent the relative amounts of phosphorylated RPA2 to Actin normalized to the sample with the highest amount of phosphorylated RPA2. (D) Western blot of hyperphosphorylation of RPA2 at 0 and 24 hours after a 2-hour treatment of 20 µM etoposide. Abbreviations: RPA, replication protein A; UMSCC, squamous cell carcinoma cell lines established at the University of Michigan.

DISCUSSION

The preservation of genomic integrity requires specific cellular mechanisms, termed checkpoints, which can detect and trigger the repair of DNA damage. These checkpoints result in the activation of multiple signaling pathways before continuing to the next phase of the cell cycle, and many components of these pathways are considered to be tumor suppressors. Cancer cells are known to have higher levels of replicative stress than those of adjacent normal cells.38,39 This is thought to be explained by the fact that rapidly dividing cells generate replication stress, which leads to checkpoint activation and cell-cycle arrest. To maintain rapid cell turnover, cancer cells are under selective pressure to inactivate checkpoint mechanisms.40 Although RPA functions in checkpoint signaling, RPA expression cannot be disrupted through inactivating mutations because of its fundamental role in DNA replication. An advantageous alternative to selection for RPA mutations would be to alter RPA function by suppressing phosphorylation of RPA2 in cancer cells. We have identified cancer cell lines that have suppressed the DNA damage response and do not phosphorylate RPA2. We find that the ability to hyperphosphorylate RPA2 in response to cisplatin and etoposide exposure correlates with sensitivity to cisplatin and etoposide. Hyperphosphorylation of RPA2 in cisplatin-resistant HNSCC cells after etoposide exposure was paralleled by the ability to progress through S phase, whereas cisplatin-sensitive HNSCC cells unable to phosphorylate RPA2 failed to complete DNA replication. Our data are consistent with previously published data that used U2OS cells expressing a phosphomutant form of RPA2. These cells accumulated in S phase, whereas cells expressing wild-type RPA2 continued to cycle into the G2 phase after camptothecin exposure.41 Our data are also consistent with a recent analysis of an ATR mutant, which was reported to impede progression through S phase with consequent survival defects in response to cisplatin treatment.37

Possible mechanisms of cisplatin resistance vary by cell type and are not completely understood.42 In vitro studies have suggested that decreased uptake, increased efflux of cisplatin, and inactivation of cisplatin play a role, although there is no clear consensus if any has clinical relevance. However, it is clear that DNA damage response and DNA repair pathways have an important role in both acquired and intrinsic resistance to this chemotherapeutic. 43,44 We find that gradually increasing concentrations of cisplatin selected for cells with increased cisplatin resistance, etoposide resistance and RPA hyperphosphorylation. The resistance to cisplatin may be explained by an enhanced DNA damage response. This is consistent with the observation that the UMSCC cells that survive cisplatin selection are those with increased hyperphosphorylation of RPA2.

Cisplatin induces DNA damage through adduct formation on DNA, whereas the topoisomerase II inhibitor etoposide traps topoisomerase II in a complex with cleaved DNA.45 Although DNA-damaging chemotherapeutics cause DNA damage in distinct ways, 1 common factor downstream of the damaging events is the generation of ssDNA, created either by the damage itself or during repair activity. RPA is recruited to stretches of ssDNA after damage and hyperphosphorylated at the RPA2 subunit, which is believed to be critical for its role in DNA-damage–dependent signaling. Increased chromatin association of hyperphosphorylated RPA after etoposide and cisplatin treatment supports a functional role for hyperphosphorylation of RPA2.5,25 Previously published data showed that when the N-terminus of RPA2 was mutated by introducing negatively charged amino acids designed to mimic phosphorylated residues, the mutations promoted an interaction between RPA2 and the basic cleft present in the N-terminus of RPA1.46,47 Many important checkpoint proteins bind to the N-terminus of RPA1, including Rad17, Rad9, ATRIP, and MRE11.48–51 By altering the proteins that bind to the N-terminus of RPA1, RPA2 hyperphosphorylation could enhance the assembly and disassembly of protein complexes at the site of cisplatin and etoposide DNA lesions.

It is well accepted that cancers that become refractory to aggressive cisplatin-based chemotherapy will likely become unresponsive to many other chemotherapeutics that induce DNA damage, including etoposide.52,53 Hyperphosphorylation of RPA2 occurs in response to a variety of DNA-damaging agents,18,54 which makes it an ideal candidate to identify cross-resistances in response to DNA-damaging agents. There is a critical need for identification of markers that can predict patient response to cisplatin- and etoposide-based chemotherapies. The ability to predict which patients with HNSCC will respond to chemotherapy and which will experience treatment failure would have great clinical value. Based on the availability of phospho-antibodies to detect hyperphosphorylated RPA2 and our observation that hyperphosphorylation of RPA2 is a marker for increased cellular resistance to both cisplatin and etoposide in cell lines derived from HNSCC, we suggest RPA2 hyperphosphorylation may serve as a valuable tool to screen for cisplatin and etoposide sensitivities in patients with HNSCC. We are currently investigating this possibility. In addition, this marker may also serve as a novel target to overcome resistance because inhibition of RPA2 hyperphosphorylation could increase the efficacy of current chemotherapeutic drugs.

Acknowledgments

Contract grant sponsor: Division of Research Resources, National Institutes of Health; Contract grant number: P20-RR-018759; Contract grant sponsor: Department of Human and Health Services of Nebraska.

REFERENCES

- 1.Murdoch D. Standard, and novel cytotoxic and molecular-targeted, therapies for HNSCC: an evidence-based review. Curr Opin Oncol. 2007;19:216–221. doi: 10.1097/01.cco.0000264952.98166.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gedlicka C, Kornfehl J, Turhani D, Burian M, Formanek M. Salvage therapy with oral etoposide in recurrent and/or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Cancer Invest. 2006;24:242–245. doi: 10.1080/07357900600633734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shechter D, Costanzo V, Gautier J. Regulation of DNA replication by ATR: signaling in response to DNA intermediates. DNA Repair (Amst) 2004;3:901–908. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2004.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nghiem P, Park PK, Kim Y, Vaziri C, Schreiber SL. ATR inhibition selectively sensitizes G1 checkpoint-deficient cells to lethal premature chromatin condensation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:9092–9097. doi: 10.1073/pnas.161281798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Costanzo V, Shechter D, Lupardus PJ, Cimprich KA, Gottesman M, Gautier J. An ATR- and Cdc7-dependent DNA damage checkpoint that inhibits initiation of DNA replication. Mol Cell. 2003;11:203–213. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00799-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dimitrova DS, Gilbert DM. Temporally coordinated assembly and disassembly of replication factories in the absence of DNA synthesis. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:686–694. doi: 10.1038/35036309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lopes M, Cotta-Ramusino C, Pellicioli A, et al. The DNA replication checkpoint response stabilizes stalled replication forks. Nature. 2001;412:557–561. doi: 10.1038/35087613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ramilo C, Gu L, Guo S, et al. Partial reconstitution of human DNA mismatch repair in vitro: characterization of the role of human replication protein A. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:2037–2046. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.7.2037-2046.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Park MS, Ludwig DL, Stigger E, Lee SH. Physical interaction between human RAD52 and RPA is required for homologous recombination in mammalian cells. J. Biol Chem. 1996;271:18996–19000. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.31.18996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Golub EI, Gupta RC, Haaf T, Wold MS, Radding CM. Interaction of human rad51 recombination protein with single- stranded DNA binding protein, RPA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:5388–5393. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.23.5388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Perrault R, Cheong N, Wang H, Wang H, Iliakis G. RPA facilitates rejoining of DNA double-strand breaks in an in vitro assay utilizing genomic DNA as substrate. Int J Radiat Biol. 2001;77:593–607. doi: 10.1080/09553000110036773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aboussekhra A, Biggerstaff M, Shivji MK, et al. Mammalian DNA nucleotide excision repair reconstituted with purified protein components. Cell. 1995;80:859–868. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90289-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee SE, Moore JK, Holmes A, Umezu K, Kolodner RD, Haber JE. Saccharomyces Ku70, mre11/rad50 and RPA proteins regulate adaptation to G2/M arrest after DNA damage. Cell. 1998;94:399–409. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81482-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang Y, Putnam CD, Kane MF, et al. Mutation in Rpa1 results in defective DNA double-strand break repair, chromosomal instability and cancer in mice. Nat Genet. 2005;37:750–755. doi: 10.1038/ng1587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gollin SM. Chromosomal alterations in squamous cell carcinomas of the head and neck: window to the biology of disease. Head Neck. 2001;23:238–253. doi: 10.1002/1097-0347(200103)23:3<238::aid-hed1025>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Califano J, Westra WH, Meininger G, Corio R, Koch WM, Sidransky D. Genetic progression and clonal relationship of recurrent premalignant head and neck lesions. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:347–352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gatti L, Supino R, Perego P, et al. Apoptosis and growth arrest induced by platinum compounds in U2-OS cells reflect a specific DNA damage recognition associated with a different p53-mediated response. Cell Death Differ. 2002;9:1352–1359. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Binz SK, Sheehan AM, Wold MS. Replication protein A phosphorylation and the cellular response to DNA damage. DNA Repair (Amst) 2004;3:1015–1024. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2004.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rossi R, Lidonnici MR, Soza S, Biamonti G, Montecucco A. The dispersal of replication proteins after etoposide treatment requires the cooperation of Nbs1 with the ataxia telangiectasia Rad3-related/Chk1 pathway. Cancer Res. 2006;66:1675–1683. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Olson E, Nievera CJ, Klimovich V, Fanning E, Wu X. RPA2 is a direct downstream target for ATR to regulate the S-phase checkpoint. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:39517–39533. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605121200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vassin VM, Wold MS, Borowiec JA. Replication protein A (RPA) phosphorylation prevents RPA association with replication centers. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:1930–1943. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.5.1930-1943.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Din S, Brill SJ, Fairman MP, Stillman B. Cell-cycle-regulated phosphorylation of DNA replication factor A from human and yeast cells. Genes Dev. 1990;4:968–977. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.6.968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zernik-Kobak M, Vasunia K, Connelly M, Anderson CW, Dixon K. Sites of UV-induced phosphorylation of the p34 subunit of replication protein A from HeLa cells. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:23896–23904. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.38.23896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oakley GG, Loberg LI, Yao J, et al. UV-induced hyperphosphorylation of replication protein A depends on DNA replication and expression of ATM protein. Mol Biol Cell. 2001;12:1199–1213. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.5.1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cruet-Hennequart S, Glynn MT, Murillo LS, Coyne S, Carty MP. Enhanced DNA-PK-mediated RPA2 hyperphosphorylation in DNA polymerase eta-deficient human cells treated with cisplatin and oxaliplatin. DNA Repair (Amst) 2008;7:582–596. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2007.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu X, Yang Z, Liu Y, Zou Y. Preferential localization of hyperphosphorylated replication protein A to double-strand break repair and checkpoint complexes upon DNA damage. Biochem J. 2005;391:473–480. doi: 10.1042/BJ20050379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Patrick SM, Oakley GG, Dixon K, Turchi JJ. DNA damage induced hyperphosphorylation of replication protein A. 2. Characterization of DNA binding activity, protein interactions, and activity in DNA replication and repair. Biochemistry. 2005;44:8438–8448. doi: 10.1021/bi048057b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oakley GG, Patrick SM, Yao J, Carty MP, Turchi JJ, Dixon K. RPA phosphorylation in mitosis alters DNA binding and protein–protein interactions. Biochemistry. 2003;42:3255–3264. doi: 10.1021/bi026377u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abramova NA, Russell J, Botchan M, Li R. Interaction between replication protein A and p53 is disrupted after UV damage in a DNA repair-dependent manner. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:7186–7191. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.14.7186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carty MP, Zernik-Kobak M, McGrath S, Dixon K. UV light-induced DNA synthesis arrest in HeLa cells is associated with changes in phosphorylation of human single-stranded DNA-binding protein. EMBO J. 1994;13:2114–2123. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06487.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krause CJ, Carey TE, Ott RW, Hurbis C, McClatchey KD, Regezi JA. Human squamous cell carcinoma. Establishment and characterization of new permanent cell lines. Arch Otolaryngol. 1981;107:703–710. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1981.00790470051012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cruet-Hennequart S, Coyne S, Glynn MT, Oakley GG, Carty MP. UV-induced RPA phosphorylation is increased in the absence of DNA polymerase eta and requires DNA-PK. DNA Repair (Amst) 2006;5:491–504. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2006.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bradford CR, Zhu S, Ogawa H, et al. p53 mutation correlates with cisplatin sensitivity in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma lines. Head Neck. 2003;25:654–661. doi: 10.1002/hed.10274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Akervall J, Guo X, Qian CN, et al. Genetic and expression profiles of squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck correlate with cisplatin sensitivity and resistance in cell lines and patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:8204–8213. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang Z, Faustino PJ, Andrews PA, et al. Decreased cisplatin/DNA adduct formation is associated with cisplatin resistance in human head and neck cancer cell lines. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2000;46:255–262. doi: 10.1007/s002800000167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shao RG, Cao CX, Zhang H, Kohn KW, Wold MS, Pommier Y. Replication-mediated DNA damage by camptothecin induces phosphorylation of RPA by DNA-dependent protein kinase and dissociates RPA:DNA-PK complexes. EMBO J. 1999;18:1397–1406. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.5.1397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wilsker D, Bunz F. Loss of ataxia telangiectasia mutated- and Rad3-related function potentiates the effects of chemotherapeutic drugs on cancer cell survival. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6:1406–1413. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bartkova J, Horejsi Z, Koed K, et al. DNA damage response as a candidate anti-cancer barrier in early human tumorigenesis. Nature. 2005;434:864–870. doi: 10.1038/nature03482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gorgoulis VG, Vassiliou LV, Karakaidos P, et al. Activation of the DNA damage checkpoint and genomic instability in human precancerous lesions. Nature. 2005;434:907–913. doi: 10.1038/nature03485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cahill DP, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, Lengauer C. Genetic instability and darwinian selection in tumours. Trends Cell Biol. 1999;9:M57–M60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Anantha RW, Vassin VM, Borowiec JA. Sequential and synergistic modification of human RPA stimulates chromosomal DNA repair. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:35910–35923. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704645200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Plooy AC, van Dijk M, Lohman PH. Induction and repair of DNA cross-links in Chinese hamster ovary cells treated with various platinum coordination compounds in relation to platinum binding to DNA, cytotoxicity, mutagenicity, and antitumor activity. Cancer Res. 1984;44:2043–2051. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zamble DB, Lippard SJ. Cisplatin and DNA repair in cancer chemotherapy. Trends Biochem Sci. 1995;20:435–439. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)89095-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Martin LP, Hamilton TC, Schilder RJ. Platinum resistance: the role of DNA repair pathways. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:1291–1295. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-2238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Baldwin EL, Osheroff N. Etoposide, topoisomerase II and cancer. Curr Med Chem Anticancer Agents. 2005;5:363–372. doi: 10.2174/1568011054222364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Binz SK, Lao Y, Lowry DF, Wold MS. The phosphorylation domain of the 32-kDa subunit of replication protein A (RPA) modulates RPA-DNA interactions. Evidence for an intersubunit interaction. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:35584–35591. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305388200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bochkareva E, Kaustov L, Ayed A, et al. Single-stranded DNA mimicry in the p53 transactivation domain interaction with replication protein A. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:15412–15417. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504614102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zou L, Liu D, Elledge SJ. Replication protein A-mediated recruitment and activation of Rad17 complexes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:13827–13832. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2336100100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ball HL, Ehrhardt MR, Mordes DA, Glick GG, Chazin WJ, Cortez D. Function of a conserved checkpoint recruitment domain in ATRIP proteins. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:3367–3377. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02238-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xu X, Vaithiyalingam S, Glick GG, Mordes DA, Chazin WJ, Cortez D. The basic cleft of RPA70N binds multiple checkpoint proteins, including RAD9, to regulate ATR signaling. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:7345–7353. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01079-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Majka J, Binz SK, Wold MS, Burgers PM. Replication protein A directs loading of the DNA damage checkpoint clamp to 5′-DNA junctions. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:27855–27861. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605176200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shellard SA, Hosking LK, Hill BT. Characterisation of the unusual expression of cross resistance to cisplatin in a series of etoposide-selected resistant sublines of the SuSa testicular teratoma cell line. Biochem Pharmacol. 1994;47:775–779. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(94)90476-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hamaguchi K, Godwin AK, Yakushiji M, O’Dwyer PJ, Ozols RF, Hamilton TC. Cross-resistance to diverse drugs is associated with primary cisplatin resistance in ovarian cancer cell lines. Cancer Res. 1993;53:5225–5232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liu VF, Weaver DT. The ionizing radiation-induced replication protein A phosphorylation response differs between ataxia telangiectasia and normal human cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:7222–7231. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.12.7222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]