Abstract

Context:

The need to include evidence-based practice (EBP) concepts in entry-level athletic training education is evident as the profession transitions toward using evidence to inform clinical decision making.

Objective:

To evaluate athletic training educators' experience with implementation of EBP concepts in Commission on Accreditation of Athletic Training Education (CAATE)-accredited entry-level athletic training education programs in reference to educational barriers and strategies for overcoming these barriers.

Design:

Qualitative interviews of emergent design with grounded theory.

Setting:

Undergraduate CAATE-accredited athletic training education programs.

Patients or Other Participants:

Eleven educators (3 men, 8 women). The average number of years teaching was 14.73 ± 7.06.

Data Collection and Analysis:

Interviews were conducted to evaluate perceived barriers and strategies for overcoming these barriers to implementation of evidence-based concepts in the curriculum. Interviews were explored qualitatively through open and axial coding. Established themes and categories were triangulated and member checked to determine trustworthiness.

Results:

Educators identified 3 categories of need for EBP instruction: respect for the athletic training profession, use of EBP as part of the decision-making toolbox, and third-party reimbursement. Barriers to incorporating EBP concepts included time, role strain, knowledge, and the gap between clinical and educational practices. Suggested strategies for surmounting barriers included identifying a starting point for inclusion and approaching inclusion from a faculty perspective.

Conclusions:

Educators must transition toward instruction of EBP, regardless of barriers present in their academic programs, in order to maintain progress with other health professions' clinical practices and educational standards. Because today's students are tomorrow's clinicians, we need to include EBP concepts in entry-level education to promote critical thinking, inspire potential research interest, and further develop the available body of knowledge in our growing clinical practice.

Keywords: athletic trainers, competencies, pedagogy

Key Points.

For athletic trainers, evidence-based practice encourages critical thinking, spurs interest in research, and advances the body of knowledge.

To adequately prepare athletic trainers for the health care environment, athletic training educators must include evidence-based concepts in their entry-level curricula.

The health professions have demonstrated a commitment to evidence-based practice (EBP) because it encompasses a combination of patient values and clinical expertise with research evidence.1–3 In athletic training, this commitment has been noted in recent years through the efforts of the National Athletic Trainers' Association (NATA) toward continuing-education opportunities involving EBP,4 grant funding for EBP-related research, and formatting of position statements to match the Cochrane evidence-based grading scale.2 These emphases are essential; however, we should also emulate the EBP frontrunners, medicine5–7 and nursing,1,8–10 in designing educational curricula to include evidence-based concepts in order to prepare students to act as evidence-based practitioners.

The importance of EBP to athletic trainers is multifaceted.2,11 Specific areas of EBP emphasis include efforts to improve patient care,11 support for state athletic training licensure, third-party reimbursement,4 access to current evidence-based information via available technology and resources, dissemination of knowledge,12 and the ability to demonstrate cost-effective care.2 Although each of the aforementioned areas is very important to the advancement of athletic training, entry-level programs and continuing-education opportunities must promote these areas to better prepare athletic trainers to provide effective patient care and further the profession.

Preparation of entry-level clinicians to use EBP should include integration of the 5-step process into didactic and clinical education. Nursing1,13 and physical therapy14–16 curricula have begun the transition toward this inclusion via educational competencies. These competencies focus primarily on developing skills in the 5 areas of EBP: defining a clinical question, conducting a targeted literature search, critically analyzing the literature, applying clinical expertise and evidence, and evaluating the overall process.16 The 4th edition of the NATA Educational Competencies17 required clinical skill development, critical thinking, and research as components of entry-level education curricula. These competencies help develop the athletic training student, but they do not specifically address EBP. The 5th edition of the NATA Educational Competencies was released in February 2011 and includes an EBP focus18; therefore, education in these concepts is an immediate need. The newly formulated alliance among the NATA, the Commission on Accreditation of Athletic Training Education (CAATE), and the Board of Certification to collaborate on issues facing athletic training19,20 will provide essential support for evidence-based athletic training. The NATA's Executive Committee on Education21 will strongly rely on the cohesive efforts of the alliance to promote and support this initiative as it is developed.

Although other health professions have embraced EBP, many barriers to its inclusion in the clinical22,23 and didactic6,24–27 realms have been documented. These barriers result from insufficient time,22–25 knowledge,6,22,26 access to research materials,25,27 confidence in EBP skills,23 and institutional or employer support,22,24,25 among other factors. The shared didactic and clinical instruction requirements of athletic training education create an environment conducive to these barriers. However, no researchers have targeted the athletic training population, clinical or didactic, regarding barriers to EBP. We need to identify the potential issues educators may face when trying to implement these concepts, whether they serve as instructors or clinicians, in order to develop strategies to overcome these obstacles.

The purpose of our study was to evaluate select entry-level undergraduate athletic training educators' experiences with and implementation of EBP concepts in athletic training education programs (ATEPs). The focus of the investigation was to identify the perceived educational barriers and strategies for overcoming these barriers.

METHODS

Participants

Eleven educators (3 men, 8 women) currently instructing in CAATE-accredited undergraduate entry-level ATEPs were interviewed regarding their experience with the EBP process, barriers to implementation of associated concepts, and strategies for overcoming these barriers. Six of the participants held terminal degrees. Six were program directors, 3 were clinical coordinators, 1 was an instructor and assistant athletic trainer, and 1 was an instructor. On average, they had taught for 14.73 ± 7.06 years (Table 1).

Table 1.

Participants' Demographic Information

| Pseudonym Participant | Sex | Years of Teaching Experience | Role in the Athletic Training Education Program |

| Conners | M | 18 | Clinical coordinator |

| Dr Ellisa | F | 9 | Clinical coordinator |

| Dr Frissel | F | 18 | Program director |

| Dr Front | F | 26 | Program director |

| House | F | 23 | Program director |

| Dr Lowder | F | 11 | Clinical coordinator |

| Mendelsen | M | 10 | Program director |

| Dr Mensou | F | 20 | Program director |

| Miser | F | 10 | Instructor, assistant athletic trainer |

| Dr. Stevens | M | 23 | Program director |

| Westin | F | 2 | Instructor |

a “Dr” indicates the possession of a terminal degree.

Educators were interviewed by one researcher via telephone during the spring and fall 2008 academic semesters. The purposeful sampling method included snowball or chain sampling in combination with critical case sampling. Snowball sampling involves recognizing people believed to have the most knowledge about the topic to be studied (in this case, use of EBP), gaining their views and beliefs about the topic, and asking that they provide the names of others they believe to have knowledge and experience in the topic of EBP.28 We purposefully selected the first 2 participants because we knew they were teaching EBP, and we believed that they would complete the study in its entirety, which the participants confirmed. We contacted additional participants after their names were provided by other athletic training educators involved with the study. Educators known to provide instruction solely at the master's level were excluded from participation. Saturation of data regarding barriers occurred during the ninth interview; however, because additional research questions were asked in the interview protocol, we conducted 2 more interviews to confirm saturation of all areas of inquiry. Along with colleagues' recommendations, we used critical case sampling to ensure that participants met 2 experience-related criteria to improve the generalizability of the results: current involvement (within the past 12 months) with an undergraduate ATEP and use of evidence-based concepts within their instructional methods. We confirmed the use of evidence-based concepts with each participant via e-mail invitation and a yes answer to the following question: “Do you currently include EBP in athletic training courses?” The small purposeful sample was targeted to attain the richest information possible about the topic of teaching EBP.28

Design

The qualitative design best suited for this study was that of emergent design combined with modified grounded theory.28,29 Flexibility to develop the qualitative inquiry as the interviews transpired was provided through the emergent design structure.28 Openness to fully examining all areas to which the data and questions led during the interviews was permitted with this design; all conversation was encouraged, regardless of deviation from the initial questioning protocol. Meaning, structure, and experiences related to the topic of EBP implementation were identified during theory evaluation and explanation.28,30

We created a semistructured interview containing open-ended questions to learn about the experiences of athletic training educators regarding EBP concepts (Table 2). As described in emergent design,28 the researcher encouraged participants to elaborate, define, and clarify answers during the interview while retaining the flexibility to deviate from the set questions. Interviews were tape recorded and transcribed for analysis. The study was approved by the university's human subjects committee as an exempt project. To maintain confidentiality, all participants' names are pseudonyms.

Table 2.

Protocol for Interview Questions

|

Abbreviations: ATEP, athletic training education program; EBP, evidence-based practice.

Modified grounded theory allows for interview analysis via identification of themes, patterns, and categories through open coding, with subsequent comparisons within and between categories through axial coding.28 We initially identified patterns while conducting interviews, and these patterns provided the basis for theme development during coding. The primary researcher confirmed, expanded, and subcategorized the data until data categories were saturated or exhausted.28,30 These coding methods allowed the confirmation of emerging theories and patterns, thus establishing the meaning and structure of participants' experiences regarding EBP.28,30

Trustworthiness of the data was established via triangulation, peer review, and participant checking.28,30 Multianalyst triangulation28 occurred via evaluation of data by members of the research team who analyzed transcriptions and discussed emergent themes. An athletic training educator with knowledge of qualitative research conducted the peer review28 by examining identified themes for consistency and significance. Lastly, participant checking30 took place through review of transcript coding results by select participants for their agreement with identified themes and patterns.

RESULTS

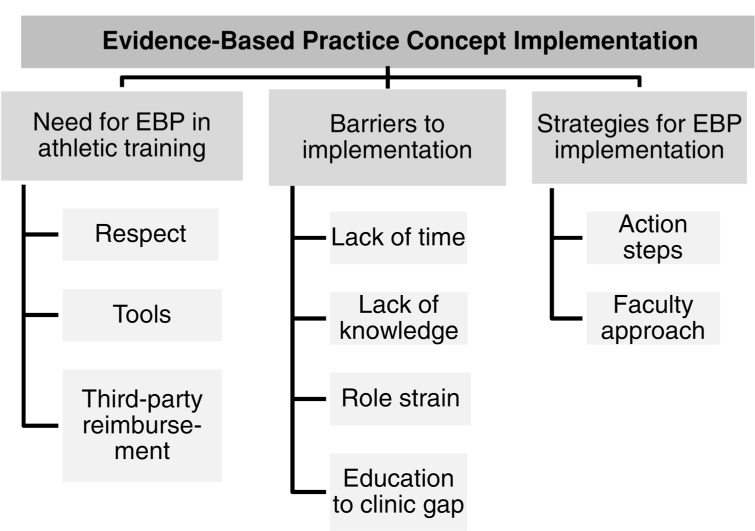

Our evaluation of transcribed data revealed 3 primary themes related to the need for EBP in athletic training, perceived barriers to implementation in CAATE-accredited undergraduate programs, and strategies for overcoming these barriers. Subthemes within each primary theme were identified to further illustrate the perceptions of these educators. The conceptual framework of themes is shown in the Figure.

Figure.

Conceptual framework of overarching theme (implementation of the evidence-based practice concept) and associated sub-themes. Abbreviation: EBP, evidence-based practice.

Need for EBP in Athletic Training

During the interviews, it became evident that educators thought that EBP should be included in athletic training. The discussion of this theme began with educators detailing why they thought undergraduate education should introduce these concepts:

You are doing your students a tremendous disservice if they don't hear these terms and understand that this (EBP) is out there . . . because I think this is not a fad. I think that this is an actual appropriate transit of trying to look at where the best way to go for this is. So for other programs, I think you just get it in, you've got to start somewhere.—Dr Stevens

Further discussion focused on the subthemes of desired respect for the athletic training profession, use of EBP as a decision-making tool, and justification for third-party reimbursement.

Respect.

Educators indicated that increasing respect for the profession is based on the ability to justify our practice decisions, particularly in comparison with other health professionals.

Well, I think it [EBP] drives health care. If athletic trainers want to be considered part of the health care team, then we need to adopt those principles in our everyday work. It's the thing that gets you recognition now in terms of credibility in health care.—House

I really want to see athletic training go far, I want it to be respected as an allied health profession, to the extent that physical therapist or occupational therapist is respected and especially with the debates going on about our profession. I think evidence-based medicine is going to really help to identify who we are and signify our importance—why we're needed, why we should be kept around.—Westin

Tools.

Educators articulated their perceptions of how EBP can be used as a tool in clinical decision making and allowing students to ask “why?” in a structured and purposeful manner.

It's [EBP] another tool, another piece to our knowledge, so that we can make a better decision about what to do or what not to do. It is a tool to help you be more effective. That's kind of how I use it.—Dr Lowder

So we try to get students to understand that it's not just this esoteric concept coming down from above, it's really something that you use every day, so why wouldn't you do it in management of your patients?—House

Personally, I'd like to see it [EBP] just as another tool in the toolbox that clinicians use, or educators use, in the classroom; you know, a great way to get it across is to question why. If a student asks a question, instead of answering them with what you know, tell them to go look.—Westin

Third-Party Reimbursement.

Support for gaining third-party reimbursement was one of the greatest needs expressed by educators. Miser and House discussed the link between evidence and use of effective treatment practices:

I think [it's] probably showing treatment efficacies of patient care. I guess, bottom line, why would you do something that doesn't work? Why would you buy something that didn't work? It's going to keep people safe first, it's going to keep our bottom line down if we are doing more efficient treatment. I just think in general it's going to look better for us [athletic trainers], and I think we will be the better for it.—Miser

Because one of the big drivers in health care of EBP is insurance companies. Because they're tired of paying for stuff that doesn't work. . . . Maybe in the fee-for-service world, maybe we're probably seeing more there. You're not going to see it in athletic training because why wouldn't I do a contrast bath when I'm going to follow it up with three other things?—House

Other educators spoke of concern reflecting both respect and reimbursement and how they must progress together.

Even with third-party reimbursement, evidence is really going to play a role. The only way to prove who we [athletic trainers] are and what we do is by evidence, and without the evidence, we're not going to go anywhere.—Westin

Dr Frissel discussed how other health professions are accountable to outside sources to justify their clinical practices.

I think physical therapists do it all the time. . . . They have to answer to somebody. They have to answer to the public. They have to answer to insurance companies. They have to answer to physicians. Because that patient is supposed to get better in eight periods that you see them by whatever means, range of motion, pain, inflammation, gait patterns, whatever it may be, and if they don't, you have someone to answer to. But we [athletic trainers] don't. We are not held accountable to outside stakeholders.—Dr Frissel

Although the need for EBP in athletic training was seen as a mechanism for gaining respect, establishing clinical tools for maximizing patient care, and justifying treatment practices in support of third-party reimbursement, participants also described obstacles that hinder full implementation.

Perceived Barriers to Implementation

The perceived barriers to EBP implementation conveyed by educators established the second theme of this study. Sub-themes within this topic included time available, knowledge, role strain, and gaps between the clinical and educational realms. Educators also discussed the courses in which they have chosen to implement EBP concepts (Table 3).

Table 3.

Undergraduate Athletic Training Courses Taught by Participants That Incorporated Evidence-Based Practice Concepts

| Frequency | |

| Therapeutic modalities | 6 |

| Evaluation (upper or lower extremity) | 5 |

| Therapeutic rehabilitation | 2 |

| Practicum | 2 |

| General medicine | 2 |

| Research design | 1 |

| Professional development | 1 |

| Organization and administration | 1 |

| Independent evidence-based practice course | 1 |

Lack of Time.

Instructors described a general lack of time available to include EBP in the classroom setting in light of existing course content and manners of implementation:

[An article gave] some examples of some things to do in classes, which was a little overwhelming, in my opinion. I can't implement all that in my class, it's just too much. Again, you've got to keep a balance between making sure that the students know how to do the evals and know the basics.—Dr Ellis

The only barrier I see is if there is any need for greater emphasis than we are currently doing [in our courses]. For example, in the research class, to do what I know could be done better, and really discuss EBP to the depth I need, I would have to change the course entirely, and this is the only research class they really get. So I am forced to put a lot of things in, in a very short period of time.—Dr Front

I think the other barrier for me was just figuring out where to put it in class. I had my own little evidence-based medicine PowerPoint, and I never found time, so I just inserted right into the other PowerPoint, because otherwise I would have blown it off.—Dr Ellis

Further illustrating the theme of lack of time, participants discussed the time necessary to gain EBP knowledge, particularly when balancing the other roles required of their positions:

[It's difficult] to find the time to understand not only the concepts, like specificity and sensitivity, likelihood ratios, what the evidence-based medicine and the five steps of it are, and understand what it is and what it isn't. So a lot of it was just time to have to read all of the information and digest it.—Dr Ellis

I think time becomes a barrier. Even though we are Division III, we're quite stressful with sports [and teaching]. I think that time is, because it does take time to develop the student, to teach them these five steps, to make sure they are doing them adequately.—Dr Frissel

Lack of Knowledge.

The second significant barrier to the implementation of EBP is evident in the educators' perceived lack of knowledge related to EBP. Instructors expressed concern about whether other educators truly know what EBP is, how to attain knowledge, barriers to mastering knowledge, and ultimately how to convey EBP knowledge to students. An initial category within the knowledge theme addressed the misconceptions of what EBP is and what it is not:

I think there is a lot of misconception out there on what it is. You have [to] ask a clinical question, and you have to figure out how to answer it. I think the biggest misconception I had about EBP in the beginning, before I read very much, was that if you research the topic and read up on it, that was EBP. And really that's not truly EBP. This is just reading up on the literature.—Dr Ellis

Additional emphasis was placed on identifying beneficial sources for obtaining evidence-based knowledge:

The other thing that we found is that there are some online modules which teach evidence-based [practice] a little bit, but you know it all depends on what the module teaches. You know some of them just teach the concept of it. There is one out at BU [Boston University] that teaches actual— you write a clinical question and it evaluates your clinical question for you, which is really good. But you know that is only one of the five steps. And it's hard to teach all that in a 45-minute session at the convention, in a lecture format.— Dr Ellis

Elaborating further on how to become comfortable with this knowledge for student interaction also elicited the importance of continuing to include EBP concepts in coursework:

For me, the biggest barrier was learning all the information and being comfortable talking about it to the students. This was not taught in my undergrad. This was not taught in my grad program, so I am kind of learning as I go. Some of the barriers were just being afraid to talk about it to the students, because I would get confused and then I would not look like I know what I'm talking about. But what I found was the more I talk about it, the better obviously I get at it.—Dr Ellis

Lastly, within this subtheme, educators emphasized the need for faculty to understand their knowledge shortcomings, while identifying the difficulty that can be associated with student mastery of evidence-based concepts.

I think if you don't know the literature, that could also be it [a barrier]. I mean, if you don't keep up with what's out there, I think that could be very threatening. Because a student is going to be inquisitive, and I think that self-efficacy is very important in that as well. If the faculty member doesn't want to be challenged, in a positive way challenged, or can have the confidence to say, “You know, I don't know that. I've got to take it to the next step, too, and I will get back to you on that”—I think young faculty members struggle with that, those of us that have been here for a while probably have a little easier time doing that.—Dr Mensou

I think it is hard to get kids into the literature. I think it is critical that we do. You know, in younger [students], when they are just trying to learn the parts, they are more worried about the “how-to” instead of the science behind it. Sometimes cramming the science down their throat makes them not like it.—Dr Mensou

The other barrier is student understanding, and it's really not their fault. It's the concept, it's hard to grasp for some of them. Even after I've explained it and they have seen it and we've talked about it, they still don't quite get it. Maybe they understand it, but they don't get it.—Dr Ellis

Role Strain.

Additional barriers to evidence-based concept implementation were manifested in the role strain described by educators. Many educators wear multiple hats in their academic positions, leading to difficulty in devoting appropriate time to such concepts.

I have to keep my assignments to a minimum because if I give too many assignments, I'll get bogged down and can't focus on my research. So if you are at a teaching institution, where that is valued . . . and you don't have any research responsibilities, then you could do a lot of things with the students and spend more time doing assignments.—Dr Ellis

I think that the typical things, time constraints, volume of patient loads . . . are holding true that athletic training as a profession is just as it is with the other allied health professions. I think that folks in our profession that know how to do it [EBP], search it.—Dr Front

A lot of faculty don't incorporate it because it's easier to just use the prefabricated PowerPoints that come with the book, because that is more time efficient. And when you are being pulled clinically, and pulled academically, and pulled administratively, sometimes you have just go to get it done, and you know, I think those issues might also impact the depth that it [EBP] is used.—Dr Mensou

Education to Clinic Gap.

The final category of the barriers theme that emerged was the perceived gap between what is taught in the classroom and what is being performed in athletic training facilities. Educators portrayed this gap as a barrier necessitating compromise and understanding from academic and clinical supervisors:

I think sometimes we get results, especially in academics, and we get a little overzealous and say, “Well, of course this is best. Why aren't we doing it in the athletic training room?” I think as educators we have to do a better job of not only educating our students but educating the clinical instructors.—Mendelsen

As an educator in a program, I can start at the ground level and get those people, the clinical instructors that I am working with, and encourage them to use it [EBP] more. And if I do that by giving the students assignments, where they are utilizing it in the clinical [setting] with their ACIs and CIs [clinical instructors], then maybe they'll start to use it more, you know, the clinical instructors themselves.—Dr Lowder

If I'm doing a literature review for a modalities class, I should be sharing that with our CIs [clinical instructors] as well as our students, in trying to make our clinical educators better in understanding . . . why they do what they do. —Mendelsen

Educators also explained that clinicians should be open to new information, particularly when interacting with students:

The clinical part and the research have to come together [in educating students]. And sometimes the clinical part has to take down some of their old thoughts and come to a new way of thinking and saying, “This really is better.” And we really need to do this regardless of how comfortable we feel with it.—Mendelsen

I think we all need to be current, too. Along with our assessment skills and rehab skills, etc, I think we all need to be responsible as clinicians for being current. I think that individual responsibility is probably the biggest inhibitor [to use of EBP].—Miser

Strategies for EBP Implementation

Educators echoed a common theme of recommended strategies for programmatic implementation of EBP concepts. These strategies included identifying a starting point for the individual educator and program while establishing a foundational approach from the entire ATEP faculty.

Action Steps.

Although educators agreed that a starting point must be established for EBP inclusion, they described vastly different starting points. For example, Mendelsen recommended that the process begin with the individual educator through conversations related to concept implementation:

[Start with] discussion with other educators as well as clinicians. . . . As instructors, we have to keep learning through discussion, and part of that has to be discussion with other educators as well as clinicians [on how to start]. I would encourage them to begin the research process on their own. And looking at what is the best practice and how do they go about implementing that, . . . if they are not looking at any literature or attending workshops on EBP on a certain topic that they are instructing or something, I would encourage them to start it as soon as possible.—Mendelsen

In contrast, Dr Front noted that programs may not choose to implement EBP concepts until required to do so by CAATE or the Board of Certification (BOC):

So to get them [ATEPs] to put it [EBP] in, I think it would have to be presented in such a way (1) that it was required and (2) that if they don't, their [students] can't sit for the BOC exam.—Dr Front

Additionally, providing programming with the methods and skills needed to move toward inclusion of these concepts was emphasized:

What folks pay for when they come to [continuing] education is basically, “What can I walk out of here and dump in my program ASAP?” We've got to give people things that they can use. It's a gratification, just like [it is for] our students.—Dr Front

We sat down for our Approved Clinical Instructor training, we sat down as a group, as this was really emerging in the discussions in athletic training, and said, “Okay, what can we do in our program to make this more visible to our students and more evident versus us just talking about it or saying, ‘Oh yeah, I'm going to do that,’ from a clinician standpoint?” And we just kind of all decided to take our own direction based on our course content with that, and so I think there has been much more delving into the research, addressing it from a clinical standpoint. . . . I think it has been both formal and informal in many ways, but I think formalized through an ACI [Approved Clinical Instructor] meeting and through our specific courses that we are teaching.—Miser

They [instructors] should read the orange Sackett book before they even start. They should read that little orange book before they even begin, because that was one of the mistakes that I made was that I didn't read that book, and I had a real misconception about what it was. . . . Advise them to read the book first and then sit down, develop a sequence, and work backwards.—Dr Ellis

We, they, are not [implementing EBP] because they don't know it. I think we need to hold more workshops for people to first understand what it is, because I don't think I can do it unless I understand it. I think you first need progressive workshops. (1) What is evidence-based practice? Understanding it, and maybe giving us assignments to do it, just like you do a student, and let us walk through the process as a student would. (2) And then let's talk about now integrating into your teaching. I am a believer that unless you have done it, and can understand it, . . . it's hard to teach it if you haven't done it or understand it. And a lot of people think they are already doing it.—Dr Mensou

Faculty Approach.

Educators also provided examples of how faculty in their own programs approached implementation of evidence-based concepts in curricula:

We did a week-long course and hammered a lot of implications of where evidence is and what does it mean, really defining it. But then [the course instructor] harped on, “How are we pumping into our education system and why? And are we making it a practice that is useful for our students so that it is benefiting the profession?”—Conners

What are your goals? What do you want your students to know? If we want them to know this [EBP concept], what do they need to know first? What do they need to know second, and don't give them too much information because you know every program is different, I am sure. You can't overwhelm them.—Dr Ellis

The program director [said] that this [EBP] was something we should be doing and that there is evidence to help support what we are doing in a clinical setting. We really started using that more in class. Then we tried to get people to use it more in the clinic. And I was both: I was in the athletic training room, and I was also in the teaching. So I really learned from some of those colleagues, that this is very important and why. So we would have a discussion, we would have like little brown bag lunches where we were talking about, “Is this really effective for this type of an injury?” It was kind of our EBP moment when we talked. It was like a little half-hour discussion we would have with clinical and faculty staff together.—Dr Lowder

We've recently been talking, the program and myself [clinical coordinator], about how we can implement it more in the clinical setting. What we'd like to do is implement an assignment where they're using it with an example patient, . . . how are they using it [EBP], and actually force them to use EBP while they are working on a treatment for their patient.—Dr Lowder

Considering the framework of identified themes, it is evident that EBP is considered a significant component in the advancement of athletic training. Our results suggest that the athletic training profession has identifiable needs for and barriers to incorporating EBP into the curricula. Additionally, evaluating individual educational settings, including current structure, knowledge, and time components, could help us surmount these barriers.

DISCUSSION

Preparing athletic training students to use EBP as professionals appears to be valued by these entry-level educators. Broadening this perceived need for implementation of evidence-based concepts may benefit the development of EBP concepts in other ATEPs, but the associated barriers must be recognized, and the strategies to overcome these barriers must be cultivated as well.

Need for EBP in Athletic Training

The athletic training profession is facing important issues with regard to establishing third-party reimbursement4 and gaining respect as clinicians and health care providers. Each of these issues has a strong link to enhanced training in EBP.4 Evidence that demonstrates the effectiveness of clinical interventions delivered by athletic trainers should provide support for obtaining third-party reimbursement.4 Accountability for this evidence has been limited in athletic training, whereas other professions, such as physical therapy,14 have moved toward significant implementation via educational reform, clinical application, and continuing education. As educators, we must introduce athletic training students to evidence-based concepts11 in order to prepare them to play an active role in future reimbursement discussions. If our students do not learn EBP while preparing at the entry level, when and where will they learn it? If we rely on NATA postprofessional programs for implementation, then we will be communicating with only a small percentage of the profession. All educators should provide students with the tools to use EBP in order to make sound clinical decisions, interpret the clinical significance of research, and foster an inquisitive nature for new research.4,11 However, we must begin this process early in the education of our athletic training students.

Strategies to Overcome Barriers to EBP Implementation

Health professionals are acutely aware of the barriers to fostering an evidence-based approach to education and clinical practice.22,23,31–33 Entities responsible for guiding the educational preparation and professional development of athletic trainers, such as the NATA and the Executive Council on Education, should work toward establishing EBP as a necessary component of athletic training preparation and provide strategies for the successful incorporation of these topics. In this section, we provide strategies for overcoming the barriers perceived by the educators in this study.

Time and Role Strain.

Study participants identified time available and the resultant role strain as major barriers to the implementation of EBP concepts. Specifically, educators thought that there was not enough time in courses that are already filled with necessary competencies to add EBP material, nor did they have enough personal time to investigate and master EBP content. As the new field of competencies is introduced to ATEPs, we should examine our current competencies not only for their overall worth but also for potential integration with other competencies to best address EBP concepts. If a competency includes a set of skills or knowledge that is not supported in literature, the inclusion of that competency should be evaluated. As educational items are assessed and potentially removed, small portions of courses could become available for implementation of EBP items.

Athletic training educators face many challenges as they try to fulfill their roles in teaching, administration, service, research,34 and clinical responsibilities. These roles take time, and for some educators, taking additional time to acquire new knowledge and learn new teaching strategies is unrealistic. In order to combat these barriers, administrative support (in both collegiate institutions and national organizations), facilitation of concept mastery through workshops and tutorials, and establishment of a culture that is receptive32 to the changing paradigm of athletic training education will help to decrease the time and role restraints on educators.

Lack of Knowledge.

Ensuring that current educators have the skills to incorporate EBP concepts into classroom teaching is a barrier for ATEPs. An ideal mechanism for learning about EBP is through a full-staff approach. Educators should display a commitment to the evidence-based process as more than just using research but rather as combining research with consideration for patients' values.9 This mindset can be achieved through faculty development opportunities.27 Institutions may elect to send faculty off-campus for skill development sessions, or they may invite outside experts to campus for training sessions.9 Regardless of the route chosen, it is important to create a core faculty who possess the interest, skills, and authority to maintain an evidence-based curriculum.9 From this foundation, educators can create a thematic approach to the curriculum, presenting EBP as a common thread throughout the program.35

Additionally, development opportunities must be made available in appropriate formats27 to encourage educators to expand areas of knowledge in which they are lacking. The influential bodies of athletic training, including the NATA and the Executive Committee for Education, are actively working to provide EBP resources in the near future. Possible formats for such materials include Internet-based tutorials and more publications on evidence-related topics. Initially, these modes of instruction should focus on foundational concepts of EBP, including the formation of a clinical question and search for relevant literature.35 As knowledge increases, more application-based concepts of diagnostic probabilities and clinical significance should be addressed.35 Given the EBP-specific content in the current edition of the Educational Competencies,18 continuing education modules on EBP should contain similar, high-quality content that can be easily understood in a timely manner. Once educators have mastered the content, effective ways to teach these concepts to students can be evaluated.

Athletic training educators and researchers11,36 have recommended that evidence-based concepts become a component of entry-level student knowledge.20 For example, Casa36 recommended that educators approach “every course . . . with honest assessments of the actual evidence to support the topics being covered. . . . [These concepts can be] embedded within assessment, rehabilitation, modalities, administration, counseling, etc.” Implementation of student activities and assignments that engage learners to search, retrieve, appraise, present, and critically analyze35,37 will allow students to gain an understanding of EBP. Furthermore, students should be encouraged to develop an inquiry-based mindset so that in the future they can contribute to the scientific nature of athletic training practice through research and publication.38

Education to Clinic Gap.

Educators spoke of the gap between the didactic and clinical realms of a student's educational experience as a barrier to the implementation of EBP. These thoughts mirror recent publications4,39 in which the balance between scholarly and clinical activity is addressed. Although it is of particular importance in advancing evidence in athletic training, scholarly activity must be conducted and presented in a manner that is usable and logical to clinicians. For example, scholars can focus more on outcomes-based research involving randomized control trials that are linked to the questions of clinicians. Additionally, educators can present information to clinicians in a manner that demonstrates the value of clinical knowledge while providing education outside the typical classroom setting to further incorporate Approved Clinical Instructors into the educational process of EBP. In exchange, clinicians should be open to furthering their knowledge through evidence supporting their practice decisions.12

Although evidence for the traditional athletic training clinical setting with regard to treatment effects is limited, what is available to clinicians may not be applicable to the patients they care for and the treatment plans they administer. To solidify this connection within the athletic training profession, journals should begin to include levels of evidence for articles and clinical “bottom lines,” and textbooks can expand on recent trends to include sensitivity, specificity, and likelihood ratios. Clinicians can then begin to combine their clinical expertise with the available evidence to maximize clinical outcomes. Keeping in mind these suggested strategies for closing the education to clinic gap, we should note that evidence supporting the clinical usefulness of special tests or treatment possibilities, for example, is not always available.36 And although this barrier was not specifically identified by our participants, it warrants further consideration.

Limitations

The participants in this study represent a purposeful, non-randomized sample of athletic training educators who may not represent the full population of instructors using EBP. The perception-oriented nature of the data could also be a limitation, because we assumed that all participants were truthful in their responses. The responses to this inquiry were variable in content, but they are valuable in helping us understand EBP through educators' eyes as we progress toward concept implementation. Other educators should review their own program content, assess relevant barriers, and design a plan for overcoming these barriers for the betterment of their students and the profession.

CONCLUSIONS

Athletic training education must include EBP concepts to prepare our clinicians for the current and future health care environment and the envisioned culture of EBP20 that is already evident in other health professions. Curricular modifications that effectively integrate EBP concepts can begin with assessments of current educational design. Educators should review program content and competency distribution, assess relevant barriers, and design plans for overcoming these barriers to improve themselves as educators, their students, and the future practice of athletic training. Today's students are tomorrow's clinicians; therefore, we need to include EBP concepts in entry-level education to promote critical thinking, inspire research interest, and further develop the available body of knowledge in our growing clinical practice.

Acknowledgments

The Mid-Atlantic Athletic Trainers' Association provided financial support for this study. We thank James Onate, PhD, ATC; Shana Pribesh, PhD; and Dorice Hankemeier, PhD, ATC, for their support.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kring DL. Clinical nurse specialist practice domains and evidence-based practice competencies: a matrix of influence. Clin Nurse Spec. 2008;22(4):179–183. doi: 10.1097/01.NUR.0000311706.38404.cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kronenfeld M, Stephenson PL, Nail-Chiwetalu B. Review for librarians of evidence-based practice in nursing and the allied health professions in the United States. J Med Libr Assoc. 2007;95(4):394–407. doi: 10.3163/1536-5050.95.4.394. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sackett DL, Rosenberg WM, Gray JA, Haynes RB, Richardson WS. Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn' t. BMJ. 1996;312(7023):71–72. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7023.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hertel J. Research training for clinicians: the crucial link between evidence-based practice and third-party reimbursement. J Athl Train. 2005;40(2):69–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Straus SE, Green ML, Bell DS. Evaluating the teaching of evidence based medicine: conceptual framework. BMJ. 2004;329(7473):1029–1032. doi: 10.1136/bmj.329.7473.1029. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Petrisor BA, Bhandari M. Principles of teaching evidence-based medicine. Injury. 2006;37(4):335–339. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2006.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wanvarie S, Sathapatayavongs B, Sirinavin S, Ingsathit A, Ungkanont A, Sirinan C. Evidence-based medicine in clinical curriculum. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2006;35(9):615–618. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burman ME, Hart AM, Brown J, Sherard P. Use of oral examinations to teach concepts of evidence-based practice to nurse practitioner students. J Nurs Educ. 2007;46(5):238–242. doi: 10.3928/01484834-20070501-09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ciliska D. Educating for evidence-based practice. J Prof Nurs. 2005;21(6):345–350. doi: 10.1016/j.profnurs.2005.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jack BA, Roberts KA, Wilson RW. Developing the skills to implement evidence based practice: a joint initiative between education and clinical practice. Nurse Educ Pract. 2003;3(2):112–118. doi: 10.1016/S1471-5953(02)00108-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Steves R, Hootman JM. Evidence-based medicine: what is it and how does it apply to athletic training? J Athl Train. 2004;39(1):83–87. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Denegar CR, Hertel J. Editorial: clinical education reform and evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. J Athl Train. 2002;37(2):127–128. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stevens KR. ACE Star Model of EBP: Knowledge Transformation. San Antonio, TX: The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio; 2004. Academic Center for Evidence-Based Practice. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gwyer J. Teaching evidence-based practice. J Phys Ther Educ. 2004;18(3):1–57. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Portney L. Evidence-based practice and clinical decision making: it's not just the research course anymore. J Phys Ther Educ. 2004;18(3):46–51. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Slavin M. Teaching evidence-based practice in physical therapy: critical competencies and necessary conditions. J Phys Ther Educ. 2004;18(3):4–11. [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Athletic Trainers' Association. Athletic Training Educational Competencies. 4th ed. Dallas, TX: National Athletic Trainers' Association; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Athletic Trainers' Association. Athletic Training Educational Competencies. 5th ed. Dallas, TX: National Athletic Trainers' Association; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hunt V. Strategic alliance signed. NATA News. July 2009:20. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sauers EL. Establishing an evidence-based practice culture: our patients deserve it. Athl Train Sports Health Care. 2009;1(6):244–247. [Google Scholar]

- 21.National Athletic Trainers' Association. Executive Committee for Education purpose statement. http://www.nata.org/access-read/public/executive-committee-education-ecc. Accessed March 6, 2011.

- 22.Brown CE, Wickline MA, Ecoff L, Glaser D. Nursing practice, knowledge, attitudes and perceived barriers to evidence-based practice at an academic medical center. J Adv Nurs. 2009;65(2):371–381. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04878.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jette DU, Bacon K, Batty C. Evidence-based practice: beliefs, attitudes, knowledge, and behaviors of physical therapists. Phys Ther. 2003;83(9):786–805. et al. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bhandari M, Montori V, Devereaux PJ, Dosanjh S, Sprague S, Guyatt GH. Challenges to the practice of evidence-based medicine during residents' surgical training: a qualitative study using grounded theory. Acad Med. 2003;78(11):1183–1190. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200311000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Melnyk BM, Fineout-Overholt E, Feinstein NF, Sadler LS, Green-Hernandez C. Nurse practitioner educators' perceived knowledge, beliefs, and teaching strategies regarding evidence-based practice: implications for accelerating the integration of evidence-based practice into graduate programs. J Prof Nurs. 2008;24(1):7–13. doi: 10.1016/j.profnurs.2007.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yousefi-Nooraie R, Rashidian A, Keating JL, Schonstein E. Teaching evidence-based practice: the teachers consider the content. J Eval Clin Pract. 2007;13(4):569–575. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2007.00885.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ciliska D. Evidence-based nursing: how far have we come? What's next? Evid Based Nurs. 2006;9(2):38–40. doi: 10.1136/ebn.9.2.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Patton MQ. Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pitney WA, Parker J. Qualitative inquiry in athletic training: principles, possibilities, and promises. J Athl Train. 2001;36(2):185–189. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pitney WA, Parker J. Qualitative Research in Physical Activity and the Health Professions. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maher CG, Sherrington C, Elkins M, Herbert RD, Moseley AM. Challenges for evidence-based physical therapy: accessing and interpreting high-quality evidence on therapy. Phys Ther. 2004;84(7):644–654. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gerrish K, Clayton J. Promoting evidence-based practice: an organizational approach. J Nurs Manag. 2004;12(2):114–123. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2004.00454.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Granger BB. Practical steps for evidence-based practice: putting one foot in front of the other. AACN Adv Crit Care. 2008;19(3):314–324. doi: 10.1097/01.AACN.0000330383.87507.d1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Perrin DH. Athletic training: from physical education to allied health. Quest. 2007;59(1):111–123. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Manspeaker SA, Van Lunen B. Implementation of evidence-based practice concepts in undergraduate athletic training education: experiences of select educators. Athl Train Educ J. 2010;5(2):51–60. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-46.5.514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Casa DJ. Question everything: the value of integrating research into an athletic training education. J Athl Train. 2005;40(3):138. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Burns HK, Foley SM. Building a foundation for an evidence-based approach to practice: teaching basic concepts to undergraduate freshman students. J Prof Nurs. 2005;21(6):351–357. doi: 10.1016/j.profnurs.2005.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Turocy P. Overview of athletic training education research publications. J Athl Train. 2002;27(suppl 4):S162–S167. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sauers EL. Clinical questions in sport rehabilitation: integrating the best available evidence. J Sport Rehabil. 2008;17(3):215–219. [Google Scholar]