Abstract

Objective

To raise family physicians’ awareness of autonomic dysreflexia (AD) in patients with spinal cord injury (SCI) and to provide some suggestions for intervention.

Sources of information

MEDLINE was searched from 1970 to July 2011 using the terms autonomic dysreflexia and spinal cord injury with family medicine or primary care. Other relevant guidelines and resources were reviewed and used.

Main message

Family physicians often lack confidence in treating patients with SCI, see them as complex and time-consuming, and feel undertrained to meet their needs. Family physicians provide a vital component of the health care of such patients, and understanding of the unique medical conditions related to SCI is important. Autonomic dysreflexia is an important, common, and potentially serious condition with which many family physicians are unfamiliar. This article will review the signs and symptoms of AD and offer some acute management options and preventive strategies for family physicians.

Conclusion

Family physicians should be aware of which patients with SCI are susceptible to AD and monitor those affected by it. Outlined is an approach to acute management. Family physicians play a pivotal role in prevention of AD through education (of the patient and other health care providers) and incorporation of strategies such as appropriate bladder, bowel, and skin care practices and warnings and management plans in the medical chart.

Case description

You are about to see Mr A., a quadriplegic patient with a spinal cord injury (SCI) at C7 that occurred 10 years ago. When you enter the room, he is semi-reclined on the examination table in obvious distress. His face is red with beads of sweat on the forehead, and he is short of breath. You recognize he is unwell, and the nurse tells you his blood pressure (BP) is 150/80 mm Hg and his heart rate (HR) is 60 beats per minute. A scan of his chart reveals his BP is normally around 100/60 mm Hg and his HR is normally 76 beats per minute. His feet and legs are cold, pale, and have goose bumps.

Most family physicians report they lack information about SCI management and feel uncomfortable treating such patients.1–8 It is not a common medical condition in family practice, and the conditions associated with SCI are viewed as complex and time-consuming. There is generally little undergraduate or postgraduate training on SCI.1,3,4,6,8,9 The literature reveals that patients with SCI visit their family physicians frequently and that the family physician plays a crucial role in their health care.3 Some knowledge of common conditions affecting individuals with SCI is essential for family physicians.1,6,7

Autonomic dysreflexia (AD) is one such condition, and many physicians outside the rehabilitation or neurologic specialities have never heard of it.10 Autonomic dysreflexia is a serious medical condition that affects many patients with SCI.5,11 It is a medical emergency requiring a high index of suspicion, quick assessment, and immediate treatment to prevent complications such as seizure, stroke, cardiac complications, or death.5 Autonomic dysreflexia is also considered a substantial impediment to quality of life by many patients with SCI.12 This article aims to raise awareness of the condition and provide some realistic management techniques for family physicians.

Sources of information

MEDLINE was searched from 1970 to July 2011 using the terms autonomic dysreflexia and spinal cord injury with family medicine or primary care. Other relevant guidelines and resources were reviewed and used.

Main message

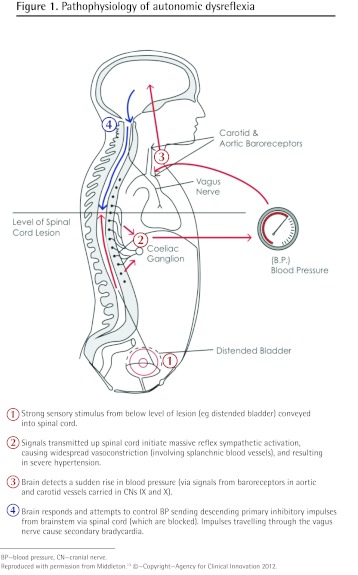

Pathophysiology of AD

Autonomic dysreflexia can occur in patients with SCI at the T6 level or higher (major splanchnic outflow T6 to L2)11,13; it has been reported in lesions as low as T10.14 It has been described as occurring in both complete (no motor or sensory function preserved in S4 to S5 segments) and incomplete (some degree of sensory or motor sparing of S4 to S5 as well as below the neurologic level) spinal cord lesions, but seems to be less severe in incomplete lesions.11 Autonomic dysreflexia is triggered by a noxious stimulus below the level of the lesion, which then activates unopposed sympathetic activity.5,10,14 Bladder and bowel irritation are the most common causes of AD (Box 1).5,10,13 The noxious stimulus is carried by intact sensory nerves below the level of the lesion to the spinal cord and activates sympathetic nerves, causing massive vasoconstriction and increased BP.6,13 The increased BP is sensed by baroreceptors in the carotid and aortic arch and activates parasympathetic nerves above the lesion to counter the sympathetic response. Unfortunately this does not relieve the vasoconstriction, as the SCI impedes this (Figure 1).13 The unique symptoms of AD are believed to be due to sympathetic input below the level of the SCI and to parasympathetic input above the injury (Box 2). It is important to note that after SCI, resting BP is often lower than normal—in the range of 90 to 110/60 mm Hg. Autonomic dysreflexia can occur with an increase in BP of as little as 20 mm Hg.5,11,13,14

Box 1. Common causes of AD.

Bladder

Bowel

Skin

Other

|

AD—autonomic dysreflexia.

Figure 1.

Pathophysiology of autonomic dysreflexia

BP—blood pressure, CN—cranial nerve.

Reproduced with permission from Middleton.13 ©—Copyright—Agency for Clinical Innovation 2012.

Box 2. Signs and symptoms of AD in patients with SCIs.

AD might involve all or some of the following:

|

AD—autonomic dysreflexia, BP—blood pressure, HR—heart rate, SCI—spinal cord injury.

SCI patients often have low resting BP of 90 to 110/60 mm Hg.

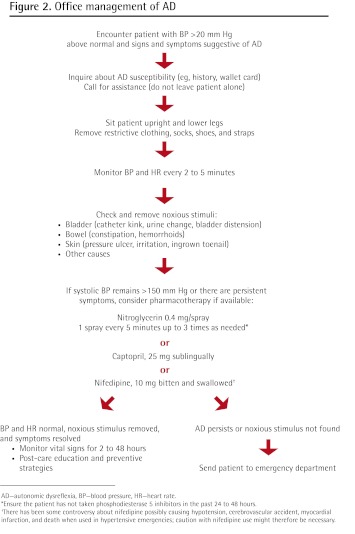

Office management of AD

Once recognized, there are a number of steps (Figure 2) that might be undertaken to resolve the condition within the family physician’s office.

Figure 2.

Office management of AD

AD—autonomic dysreflexia, BP—blood pressure, HR—heart rate.

*Ensure the patient has not taken phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitors in the past 24 to 48 hours.

†There has been some controversy about nifedipine possibly causing hypotension, cerebrovascular accident, myocardial infarction, and death when used in hypertensive emergencies; caution with nifedipine use might therefore be necessary.

Seek assistance and do not leave the patient alone.13

Ask the patient or attendant if the patient has ever had AD, what he or she thinks the trigger might be, and if he or she has an AD wallet card or MedicAlert bracelet.13

Sit the patient upright and lower the legs to reduce BP.10,13

Check for noxious stimuli, beginning with the bladder first (most common cause of AD).6,10,13

Determine the patient’s bladder care procedure (eg, intermittent catheterization, suprapubic catheter, indwelling catheter). If there is a catheter, check for obvious irritation, kinking, sediment, or cloudiness of urine (indications of urinary tract infection) and the amount of liquid in the catheter relative to intake (might give indication of retention and bladder distension).

Ask about the patient’s bowel habits and if there has been a recent change (especially indications of constipation) to determine if bowel distension is a source of the symptoms.

Check other areas such as the skin for any pressure areas, ulcers, or irritated areas (such as an ingrown toenail).

Remove the noxious stimuli if possible. Often AD can be resolved if the noxious stimulus is relieved.

Pharmacologic measures to control BP are not generally recommended early in the process but might be used to reduce symptoms and avoid complications. If the elevation in systolic BP persists or is greater than 150 to 170 mm Hg after trying to remove the noxious stimuli, BP should be pharmacologically lowered.10 Antihypertensive medications with rapid onset and a short half-life are recommended. Sublingual nitroglycerin (0.4 mg per spray) would be a realistic choice, as many family physicians have this in an emergency kit in the office. One spray might be used every 5 to 10 minutes up to 3 times as needed.13 Ensure that the patient has not taken a phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitor (sildenafil, tadalafil, or vardenafil) within 24 to 48 hours.5,13,15,16 Other antihypertensive medications that might be used are captopril, 25 mg sublingually, and nifedipine, 10 mg bitten and swallowed, both of which are safe to use if the patient is taking phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitors concomitantly. (There has been some controversy over nifedipine possibly causing hypotension, cerebrovascular accident, myocardial infarction, and death when used in hypertensive emergencies, resulting in some recommending caution in its use. There is a risk of hypotension occurring after an episode of AD for which any type of pharmacotherapy has been used; therefore, it is important to monitor the patient.)5,16,17 These medications might be added to an office emergency box or prescribed for patients with SCI for emergency use. If a noxious stimulus cannot be found and the BP cannot be controlled, then the patient should be sent to the emergency department owing to the potentially dangerous outcomes.10,16 It should be noted that important steps (eg, inserting a urinary catheter, manual evacuation of suspected fecal impaction) often referred to in the comprehensive treatment of AD (Box 3) have been omitted to provide realistic management options in the typical family physician’s office.

Box 3. Further resources.

The following resources describe the complete management of AD:

To obtain an AD wallet card, visit the following websites:

|

AD—autonomic dysreflexia.

A special population worth noting is women with SCI who are susceptible to AD during pregnancy. Hypertensive disorders in pregnancy are not uncommon in the general population. It is important to recognize that the cause of hypertension in a woman with SCI might be AD. Autonomic dysreflexia can occur at any time in pregnancy, but labour and delivery is the most risky period.16 The signs and symptoms of AD are the same during pregnancy but could still be difficult to distinguish from other causes of elevated BP (eg, preeclampsia).16 Involvement of an obstetrician and complete awareness of AD by the obstetrical team is recommended.

Post-care and prevention

After an episode of AD, BP should be monitored for 2 to 48 hours depending on the acuity of the episode (patient should be monitored for both recurrent AD and hypotension). This might be done at home (depending on the severity of the episode) by the patient or an assistant, and the patient should be instructed to seek medical care if there is an increase in BP. Patients who experience or are susceptible to AD should be instructed in management techniques and should have some supplies at home if needed (properly sized BP cuff, catheter supplies, nitroglycerin spray, sublingual captopril). If the patient does not have an AD wallet card (Box 3) or MedicAlert bracelet, he or she should be encouraged to get one. It is important that a visible note is put in the patient’s chart to notify others that the patient suffers from AD, and to clarify the symptoms and management plan. Many health care professionals (family physicians, nurse practitioners, and emergency department and hospital staff) who might need to treat AD acutely are unfamiliar with it; this might be more problematic in certain settings (eg, rural areas). It is important that patients and primary health care providers advocate for the health of patients with SCI and provide the appropriate information to other health care providers in each setting.16 Prevention of AD is one of the best management techniques. Educating patients, caregivers, and health professionals in addition to establishment of appropriate bladder, bowel, and skin care practices is essential.10,15,16

Case resolution

Mr A. tells you he suffers from AD and has an AD wallet card that gives you instructions on how to manage it. You are able to sit him up with his legs dangling. Your careful assessment of Mr A. reveals that his catheter tubing had become kinked during his transfer to the examination table. After unkinking the tube, regular monitoring of his BP and HR show that they return to his normal resting levels and his symptoms subside.

Conclusion

Autonomic dysreflexia is a common and potentially serious medical condition affecting many individuals with SCI that can be prevented. Family physicians need to be aware of the condition and there are some simple strategies to avert dangerous outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Dr Milligan receives funding via a grant from the Ontario Neurotrauma Foundation.

KEY POINTS

Although family physicians are the primary source of health care for patients with spinal cord injury, they feel unprepared to meet the medical needs of these patients. Primary health care providers should be able to recognize autonomic dysreflexia (AD), a common and serious condition arising in patients with spinal cord injury. This article provides an overview of AD and some practical strategies for acutely managing it. Autonomic dysreflexia can normally be resolved if the noxious stimulus producing it is removed. The patient should be monitored for 2 to 48 hours depending on the acuity of the episode. The patient should carry an AD wallet card or MedicAlert bracelet, and a visible note should be made in the patient’s chart to clarify symptoms and the management plan.

Footnotes

This article has been peer reviewed.

This article is eligible for Mainpro-M1 credits. To earn credits, go to www.cfp.ca and click on the Mainpro link.

La traduction en français de cet article se trouve à www.cfp.ca dans la table des matières du numéro d’août 2012 à la page e427.

Competing interests

None declared

Contributors

Dr Milligan is the lead author, which involved preparing the case, conducting the literature review, and writing most of the manuscript. Drs Lee and McMillan were instrumental in the literature review and the writing and editing of the manuscript. Ms Klassen participated in the literature review and in the writing and editing process.

References

- 1.Ontario Neurotrama Foundation Primary healthcare delivery. Where should we go from here? NeuroMatters. 2010. pp. 6–7. Available from: www.onf.org/newsletter/NeuroMattersIssue10Final(2).pdf. Accessed 2012 Jul 9.

- 2.McColl MA, Forster D, Shortt SE, Hunter D, Dorland J, Godwin M, et al. Physician experiences providing primary care to people with disabilities. Healthc Policy. 2008;4(1):e129–47. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Donnelly C, McColl MA, Charlifue S, Glass C, O’Brien P, Savic G, et al. Utilization, access and satisfaction with primary care among people with spinal cord injuries: a comparison of three countries. Spinal Cord. 2007;45(1):25–36. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101933. Epub 2006 May 30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bowers B, Esmond S, Lutz B, Jacobson N. Improving primary care for persons with disabilities: the nature of expertise. Disabil Soc. 2003;18(4):443–55. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blackmer J. Rehabilitation medicine: 1. Autonomic dysreflexia. CMAJ. 2003;169(9):931–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Middleton J, Leong G, Mann L. Management of spinal cord injury in general practice—part 1. Aust Fam Physician. 2008;37(4):229–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mann L, Middleton JW, Leong G. Fitting disability into practice—focus on spinal cord injury. Aust Fam Physician. 2007;36(12):1039–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morrison EH, George V, Mosqueda L. Primary care for adults with physical disabilities: perceptions from consumer and provider focus groups. Fam Med. 2008;40(9):645–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marks MB, Teasell R. More than ramps: accessible health care for people with disabilities. CMAJ. 2006;175(4):329, 331. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.060763. Eng. (Fr). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krassioukov A, Warburton DE, Teasell R, Eng JJ, Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation Evidence Research Team A systemic review of the management of autonomic dysreflexia after spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90(4):682–95. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2008.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Karlsson AK. Autonomic dysreflexia. Spinal Cord. 1999;37(6):383–91. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3100867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anderson KD. Targeting recovery: priorities of the spinal cord-injured population. J Neurotrauma. 2004;21(10):1371–83. doi: 10.1089/neu.2004.21.1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Middleton J. Treatment of autonomic dysreflexia for adults & adolescents with spinal cord injuries. A medical emergency targeting health professionals. Chatswood, NSW: NSW State Spinal Cord Injury Service; 2010. Available from: www.aci.health.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0007/155149/Auto_Dysreflexia_Fact_sheet.pdf. Accessed 2012 Jun 19. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moeller BA, Jr, Scheinberg D. Autonomic dysreflexia in injuries below the sixth thoracic segment [letter] JAMA. 1973;224(9):1295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rabchevsky AG, Kitzman PH. Latest approaches for the treatment of spasticity and autonomic dysreflexia in chronic spinal cord injury. Neurotherapeutics. 2011;8(2):274–82. doi: 10.1007/s13311-011-0025-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Paralyzed Veterans of America . Acute management of autonomic dysreflexia: individuals with spinal cord injury presenting to health-care facilities. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: Paralyzed Veterans of America; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grossman E, Messerli FH, Grodzicki T, Kowey P. Should a moratorium be placed on sublingual nifedipine capsules given for hypertensive emergencies and pseudo-emergencies? JAMA. 1996;276(16):1328–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]