Abstract

The sympathoadrenal system is the main source of catecholamines (CAs) in adipose tissues and therefore plays the key role in the regulation of adipose tissue metabolism. We recently reported existence of an alternative CA-producing system directly in adipose tissue cells, and here we investigated effect of various stressors—physical (cold) and emotional stress (immobilization) on dynamics of this system. Acute or chronic cold exposure increased intracellular norepinephrine (NE) and epinephrine (EPI) concentration in isolated rat mesenteric adipocytes. Gene expression of CA biosynthetic enzymes did not change in adipocytes but was increased in stromal vascular fraction (SVF) after 28 day cold. Exposure of rats to a single IMO stress caused increases in NE and EPI levels, and also gene expression of CA biosynthetic enzymes in adipocytes. In SVF changes were similar but more pronounced. Animals adapted to a long-term cold exposure (28 days, 4°C) did not show those responses found after a single IMO stress either in adipocytes or SVF. Our data indicate that gene machinery accommodated in adipocytes, which is able to synthesize NE and EPI de novo, is significantly activated by stress. Cold-adapted animals keep their adaptation even after an exposure to a novel stressor. These findings suggest the functionality of CAs produced endogenously in adipocytes. Taken together, the newly discovered CA synthesizing system in adipocytes is activated in stress situations and might significantly contribute to regulation of lipolysis and other metabolic or thermogenetic processes.

Keywords: Mesenteric adipocytes, Stromal vascular fraction, Catecholamine production, Immobilization, Cold, Novel stressors

Introduction

Stress represents an important factor in activation of the sympathoadrenal and brain catecholaminergic systems in mammals (Kvetnansky et al. 2009). Various stressors stimulate release of epinephrine (EPI) and norepinephrine (NE), biosynthesis of catecholamines (CAs), gene expression, activities, and proteins of CA biosynthetic enzymes, as well as CA transporters (Sabban and Kvetnansky 2001; Sabban et al. 2006; Sabban 2007; Kvetnansky et al. 2009; Tillinger et al. 2010). Some stressors are associated with preferential activation of the adrenal medulla and release of EPI (emotional stressors, e.g., restraint), while other stressors stimulate sympathetic neurons on periphery or in the brain to release NE (physical stressors, e.g., cold) (Kvetnansky et al. 1998, 2002; Goldstein and Kopin 2008).

Adipose tissues contain a rich sympathetic innervation, which is also activated by various stressors like in other tissues (Slavin and Ballard 1978; Bartness and Bamshad 1998; Bartness and Song 2007; Bartness et al. 2010; Bartolomucci et al. 2009; Brito et al. 2008; Giordano et al. 2005; Lafontan and Lagin 2009). Adipose tissues contain mainly NE and only trace amounts of EPI (only brown adipose tissue contains higher amount of EPI (Sudo 1985, 1987; Pendleton et al. 1978; Hökfelt 1951). Stress-induced increase in CA levels stimulates fat cell β1, β2, β3 and α2-adrenergic receptors, which activate or inhibit lipolysis (Berlan and Lafontan 1982; Lafontan and Berlan 1995; Lafontan and Langin 2009; Bartness et al. 2010; Giordano et al. 2005). CAs are considered the major regulators of lipolysis (Lafontan and Langin 2009; Bartness et al. 2010; Giordano et al. 2005) and affect also differentiation and proliferation of adipocytes (Bowers et al. 2004; Zhu et al. 2003). The function of the sympathetic nervous system in control of lipolysis has been recently reviewed (Lafontan and Langin 2009; Bartness et al. 2010).

Biosynthesis of CAs is essentially catalyzed by four enzymes: tyrosine hydroxylase (TH), l-aromatic amino acid decarboxylase, dopamine-β-hydroxylase (DBH), and phenylethanolamine N-methyltransferase (PNMT) (Kvetnansky et al. 2009). There were some indications that adipose tissue may contain specific cells that could express genes of CA biosynthetic enzymes. PNMT mRNA and immunoreactive protein were found in the adipose tissue in neuron-like cells of PNMT-overexpressing transgenic mice but not in wild types (Bottner et al. 2001). We have recently found that genes of the CA biosynthetic enzymes (TH, DBH, PNMT) are present and differently expressed in all five studied adipose tissue depots (mesenteric, inguinal, retroperitoneal, epididymal, brown-interscapular) (Vargovic et al. 2011).

Adipose tissues represent a very heterogeneous structure and besides adipocytes contain a lot of various cells, e.g., preadipocytes, pericytes, progenitor cells, neuronal cells, T- and B-cells, macrophages, etc., which are collectively known as stromal vascular fraction (SVF) (Lin et al. 2008; Schaffler and Buchler 2007; Astori et al. 2007). It has been shown that some of these cells are able to synthesize CA to boost up the thermogenic process (Flierl et al. 2008; Nguyen et al. 2011). We have recently found that adipocytes express the genetic machinery, which enable de novo production of CA in these cells (Vargovic et al. 2011).

The question arose, why adipose tissues need an additional CA production system directly in non-neuronal fat cells besides the rich sympathetic supply. What is the function of CA synthesized in adipocytes? Is this CA system activated during stress? Since stress activates sympathetic system in adipose tissues, we wanted to know whether CAs and the whole genetic machinery of their production would be activated in adipocytes isolated from mesenteric adipose tissue of stressed rats. Importantly, the stress response in this particular fat depot was associated with stress-induced NPY-related angiogenic and adipogenic program providing a direct link between stress, obesity, and metabolic disease (Kuo et al. 2007).

Our previous results have shown that exposure of rats to long-term cold (4°C) leads to an adaptation of sympathoadrenal system (SAS) at the level of the adrenal medulla, sympathetic ganglia, plasma CAs. In cold-adapted animals (28–42 days), the short-term cold-induced increase in TH activity and mRNA levels, returned to control levels (Kvetnansky et al. 1971a, 2002). Exposure of “cold-adapted rats” to another (novel) stressor, e.g., immobilization (IMO), lead in the adrenomedullary and plasma CAs systems to exaggerated responses compared to animals kept all the time at room temperature (Kvetnansky et al. 2002; Dronjak et al. 2002).

Thus, the aim of this study was to investigate effect of different stressors (emotional—IMO, physical—cold, novel, or their combination) on CA production in adipocytes and SVF isolated from mesenteric adipose tissue of rats during stress exposure. The finding of stress-induced increase in CA production in adipocytes would suggest an involvement of this newly discovered CA system in the regulation of stress response.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Male Sprague–Dawley rats, 4-month-old (300–350 g, Charles River, Suzfeld, Germany) were used in experiments of this study. Animals were housed 2–4 per cage in a controlled environment (23 ± 1°C, 12 h light–dark cycle, lights on at 6 AM). Food and water were available ad libitum. All the animal experiments were approved by the Ethical Committee of the Institute of Experimental Endocrinology, Slovak Academy of Sciences in Bratislava (protocol number RO-2804/07-221/3).

Stress Procedures

Immobilization (IMO)

Immobilization of rats was used as an intensive emotional stressor and performed as previously described (Kvetnansky and Mikulaj 1970). For a single IMO (1 × IMO), rats were immobilized once for 10, 30, 60, 120 min, respectively. We also included interval of 3 h rest period after 2 h of IMO. The IMO was performed at the same time of the day between 8 AM and noon. Rats were killed by decapitation immediately after removal from their home cages (control group) or after the particular IMO interval.

Cold Exposure

Animals were housed two per cage in a controlled environment (23 ± 1°C, 12 h light–dark cycle, lights on at 6 AM) 1 week before the beginning of experiments. Groups of cold-exposed rats were transferred to cold chamber (4 ± 1°C, 12 h light–dark cycle, lights on at 6 AM) for 3 h, 7 days, or 28 days of continual cold exposure. These experimental groups were killed by decapitation directly in cold chamber at the same day as the control group housed at 23°C.

Immobilization of Cold-Adapted Rats

The aim of this experiment was to investigate responses of cold-adapted animals to a single IMO (COLD-IMO) and to compare to animals, which were kept at room temperature (RT-IMO). Rats were housed two per cage in a controlled environment (23 ± 1°C) 1 week before the beginning of experiments. Group of cold-exposed rats was transferred to cold chamber (4 ± 1°C) for 28 days. Then, animals exposed to 28 day cold (adapted), as well as animals held at room temperature (control) were exposed to a single IMO for various intervals (30, 120 min, and 120 min + rest for 3 or 24 h). Cold-adapted rats were immobilized and decapitated in the cold chamber. All groups were killed at the same day.

Separation of Adipose Tissue Cells

Mesenteric adipose tissue (200–300 mg) was used immediately after extirpation for separation of adipocytes and SVF as described previously (Tchoukalova et al. 2008; Vargovic et al. 2011). After collagenase I (Sigma, USA) in concentration 1 mg/ml digestion (30 min, 37°C, with constant gentle agitation), floating fraction of adipocytes was subsequently washed four times by 1.5 ml Medium 199 (Gibco, Invitrogen, USA) containing 0.5% BSA and 3 mM CaCl2 (medium + BSA + CaCl2). Each washing step was followed by centrifugation pelleting the cells separated from the floating cell layer by washing and filtering. Floating cell suspension was filtered through 210 μm nylon mesh filter (Small Parts, USA) to remove any remaining cell clumps potentially harboring non-adipocyte cells. Fraction of centrifugation pelleted cells separated from adipocytes was considered to be stromal fraction.

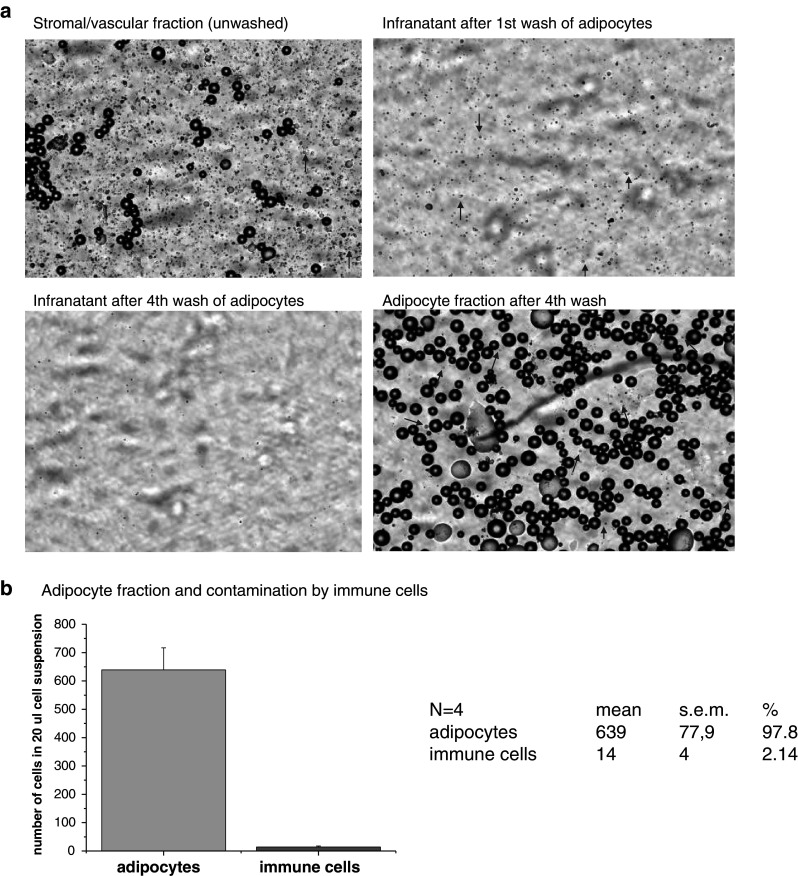

The purity of adipocyte preparation was monitored by automated histomorphological analysis with Nexelcom, cellometer T4 plus (Nexcelom Bioscience, LLC). In principle, the separation method is based on the ability of lipid laden adipocytes to float. Therefore, we have analyzed the suspension of non-floating cells before and after each washing step. We have shown that washing steps 3 and 4 were not any more effective in extracting non-adipose cells from the floating adipocyte fraction (Fig. 1a). The subsequent analysis of purified adipocyte fraction revealed that it contains approximately 2% of cells which could with their size (9–12 μm) correspond to immune cells (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1.

a Results of the automated histomorphological analysis using the Nexelcom, cellometer T4 plus (Nexcelom Bioscience, LLC.) This innovative imaging and fluorescence technology allowed to view cell morphology in real time, for visual confirmation after cell counting. Analyses of SVF, washed-out cell population in first and fourth wash as well as that of purified adipocyte fraction is shown. Arrows indicate the presence of macrophage-like cells (9–12 μm). b Statistical evaluation of adipocyte purity (97.8%) and potentially contaminating macrophage-like cells (2.14%)

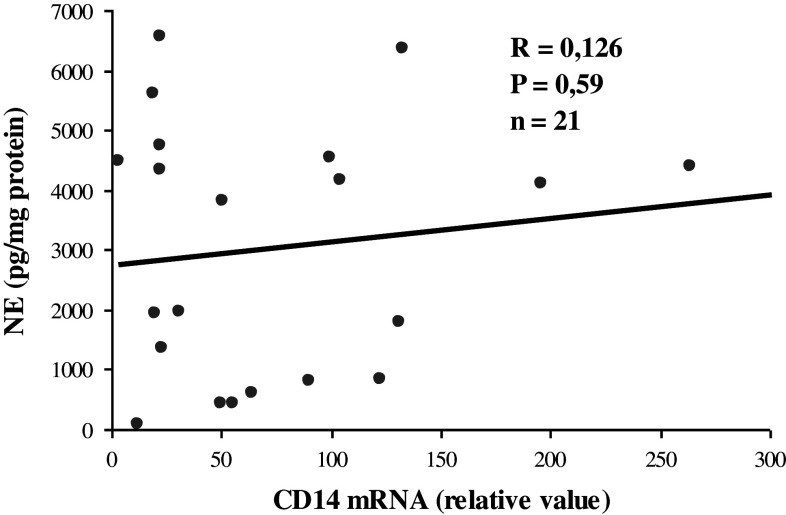

Recently, it has been reported that alternatively activated macrophages in adipose tissue could produce CAs to induce thermogenic gene expression in brown adipose tissue and lipolysis in white adipose tissue (Flierl et al. 2008; Nguyen et al. 2011). Since macrophages are able to synthesize CAs, histomorphometrical analysis was complemented by the measurement of a monocyte differentiation antigen CD14 mRNA as macrophages marker, in adipocyte fraction. The data showed that a small CD14 mRNA present in adipocyte fraction correlates neither with TH mRNA (R = 0.031, p = 0.87, n = 27) and PNMT mRNA (R = 0.044, p = 0.83, n = 27) nor with levels of NE (R = 0.126, p = 0.59, n = 21, (Fig. 2), and EPI (R = 0.035, p = 0.67, n = 18) concentrations irrespective of the stress conditions. This suggests that CD14 positive macrophages do not contribute to the stress-induced rise of CA levels or to increase in expression of CA-producing enzymes in the mesenteric adipocytes.

Fig. 2.

Correlation of CD14 mRNA with norepinephrine (NE) levels in mesenteric adipocyte fraction of control and stressed rats. Relative value −2ΔΔCT × 109

Catecholamine Determination

All CA were measured using 2-CAT or 3-CAT Research RIA kits (Labor Diagnostica Nord, Nordhorn, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Values were normalized to 1 mg of protein in homogenate determined by BCA Protein Assay (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL) modified for samples with high content of lipids according to Morton and Evans (1992).

Total RNA Isolation

Total RNA from isolated adipocytes and SVF was isolated by TRI Reagent (MRC Ltd., USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The purity and integrity of isolated RNAs was checked on GeneQuant Pro spectrophotometer (Amersham Biosciences, USA). Reverse transcription was performed using 1.5 μg of total RNAs and Ready-To-Go You-Prime First-Strand Beads (Amersham) with random hexamer primers pd(N6) (Amersham) according to manufacturer’s protocol.

Relative Quantification of mRNA Levels by Real Time RT-PCR

The PCR amplification and detection was carried out on the ABI Prism 7900HT Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems, Inc., Foster City, CA, USA). TH and PNMT were amplified using specific TaqMan probes (Applied Biosystems) (Rn00562500_m1 for TH, Rn01495588_m1 for PNMT) and Maxima Probe/ROX qPCR Master Mix according to manufacturer’s condition in 20 μl of total reaction. GAPDH was amplified by SYBR Green mastermix (ThermoFischer Scientific) using specific primers (5 pmol of primers per 20 μl of total reaction). The sequences of the primers were as follows: GAPDH forward, 5′-AGATCCACAACGGATACATT-3′, GAPDH reverse, 5′-TCCCTCAAGATTGTCAGCAA-3′. Each cycle consisted of 15 s at 95°C, 30 s at 60°C, and 30 s at 72°C for 40 cycles after the initial activating step for 2 min at 50°C and denaturing step for 10 min at 95°C. To exclude the presence of non-specific products, a routine melting curve analysis was performed after finishing the amplification. This was done by high resolution data collection during an incremental temperature increase from 60 to 95°C. Data were analyzed with SDS software version 2.3 (Applied Biosystems) and inspected to determine artifacts (loading errors, threshold errors, etc.). Baseline levels for each gene were computed automatically. Count numbers were exported to an Excel spreadsheet and analyzed according to the ΔΔCT method described by Livak and Schmittgen (2001). To find the most appropriate internal control, we tested several housekeeping genes. We have chosen GAPDH as housekeeping gene, since it did not show significant changes during IMO or cold stress. We tested several other housekeeping genes [β-actin, 18S rRNA, β2-microglobulin, TATA-binding protein (TBP)] but all of them showed significant changes in adipocytes as well as in SVF of rats exposed to cold or IMO stress (unpublished data).

Western Blot Analysis

Samples of adipocytes isolated from mesenteric adipose tissue were sonicated in 0.6 ml of 20 mM Tris pH 7.0, 5 mM PMSF (Pefabloc SC + Compete, Roche Diagnostic), stored in ice for 1 h and centrifuged for 15 min (16,100×g, 4°C). Western blotting was performed as described previously (Laukova et al. 2010). The following primary antibodies were used: monoclonal anti-TH (1:3,000; MAB5280, Chemicon International, Temecula, CA) and polyclonal anti-PNMT (1:200, CA-401 bMTrab, Protos Biotech Corp., NY). Membranes were incubated with corresponding horseradish peroxidase-linked secondary antibodies (TH with anti-mouse Ab diluted 1:5000; PNMT with anti-rabbit Ab diluted 1:5000). The signals were detected using Femto Supersignal reagent (Pierce, Rockford, IL) and visualized by exposure to Amersham Hyperfilm (Amersham Biosciences).

Statistical Evaluation

Normal distribution of the data set was tested, and nonparametric tests used when appropriate. Statistical differences among groups were determined by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by the Fisher’s protected least significant difference test (cold and IMO time courses) or by unpaired T test (comparison of the two groups within a single time point) [SigmaStat, version 3.1, Systat Software, Inc., USA]. P < 0.05 was considered to be significant. Results are presented as mean ± SEM and each value represents 4–10 rats. Values of *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, defined the statistical significance versus control groups and values of + p<0.05, ++ p < 0.01, versus groups of the same stress interval.

Results

Effect of IMO Stress on CAs and Gene Expression of CA Biosynthetic Enzymes in Isolated Adipocytes and SVF

To investigate the specific cells producing endogenous CAs in mesenteric adipose tissue of rats stressed by IMO, we analyzed NE and EPI concentration, gene expression of TH and PNMT in freshly isolated adipocytes and SVF.

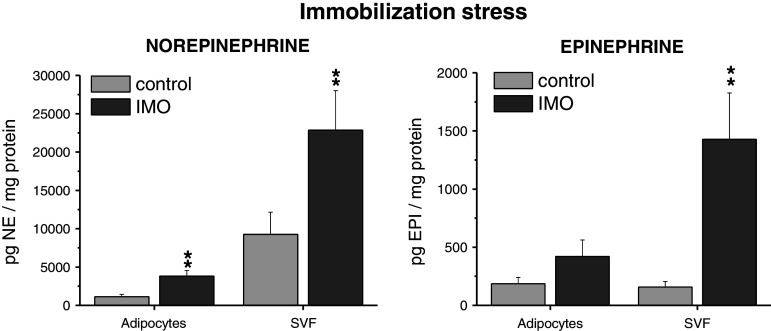

Norepinephrine concentration was significantly increased both in adipocytes and SVF of rats exposed to a single IMO for 2 h (Fig. 3). The NE level in adipocytes was several times lower than in SVF. Adipocyte concentration of EPI was several times lower than that of NE but was similar when compared to EPI in SVF. Adipocyte EPI showed only tendency to increase, however, in SVF, IMO stress produced a highly significant increase in EPI concentration (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Effect of a single immobilization for 30 min on norepinephrine and epinephrine concentration in isolated adipocytes and stromal vascular fraction (SVF) of mesenteric adipose tissue in rats. Values are displayed as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance **p < 0.01 versus control group

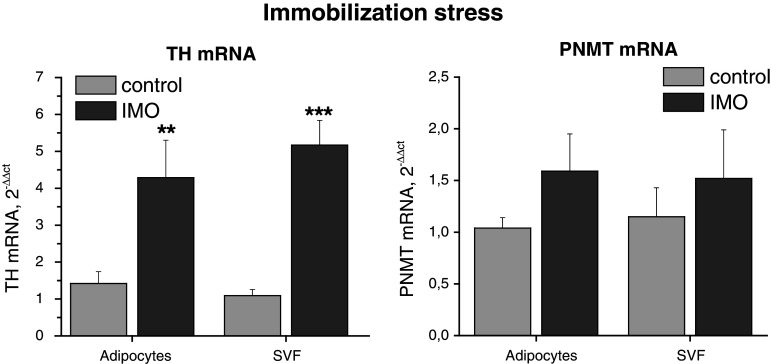

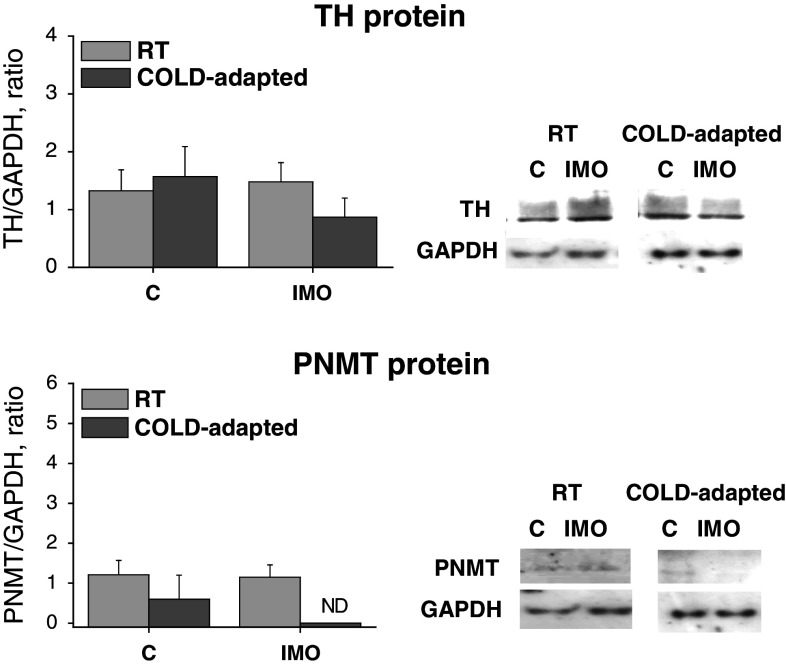

Tyrosine hydroxylase mRNA levels were significantly elevated both in adipocytes an SVF of rats exposed to a single IMO stress (Fig. 4) but a maximum response was in adipocytes induced after 10 min and in SVS only after 120 min of IMO (Fig. 8). PNMT mRNA levels were not significantly affected by a single IMO (Fig. 4). Protein levels of TH and PNMT in adipocytes and SVF were not affected by a single IMO stress because a short time of stress exposure (Fig. 9).

Fig. 4.

Effect of a single immobilization (10 min) on tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) and phenylethanolamine N-methyltransferase (PNMT) gene expression in isolated adipocytes and stromal vascular fraction (SVF) of mesenteric adipose tissue in rats. Results are normalized relatively to the housekeeper GAPDH. Values are displayed as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

Fig. 8.

Effect of exposure to various intervals of a single immobilization of rats at room temperature (RT-IMO) and those exposed prior single immobilization to cold (4°C) for 28 days (COLD-IMO), on gene expression of TH and PNMT in adipocytes and stromal vascular fraction (SVF) isolated from mesenteric adipose tissue. Results are normalized relatively to the housekeeper GAPDH. Values are displayed as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 versus appropriate control groups, + p < 0.05 versus RT-IMO group

Fig. 9.

Effect of exposure of rats to a single immobilization (30 min) at room temperature (RT) and those exposed prior immobilization to cold (4°C) for 28 days (COLD-adapted), on tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) and phenylethanolamine N-methyltransferase (PNMT) protein levels in adipocytes isolated from the mesenteric adipose tissue. Results are normalized relatively to the housekeeper GAPDH. Enclosed are typical results of a gel electrophoresis. Values are displayed as mean ± SEM. ND not detectable

Effect of Cold (4°C) Exposure on CAs and Gene Expression of CA Biosynthetic Enzymes in Isolated Adipocytes

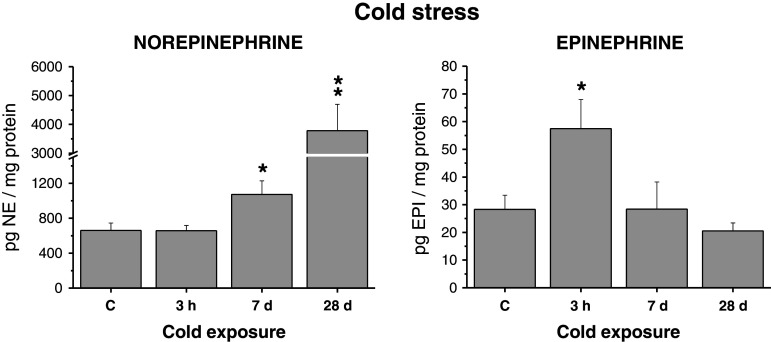

Adipocyte NE concentration was not affected by the first day of cold exposure (for 3 h), however, long-term cold exposure for 7–28 days produced a significant elevation of NE levels (Fig. 5). EPI concentration was slightly increased in animals acutely exposed to cold for the first day. On the other hand, long-term cold exposure completely abolished this increase (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Effect of acute cold (first day for 3 h) and chronic cold exposure (4°C) on endogenous catecholamine levels in adipocytes isolated from mesenteric adipose tissue in rats. Values are displayed as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 versus control group

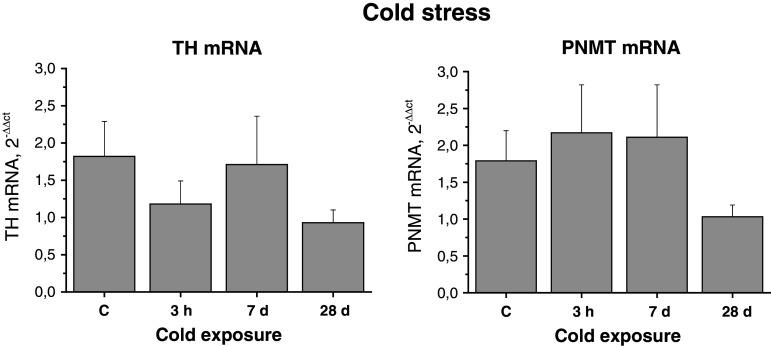

Tyrosine hydroxylase mRNA and PNMT mRNA levels did not show any significant changes in the adipocytes after acute or prolonged cold. Twenty eight-day cold exposure produced even a nonsignificant reduction of expression of these genes in adipocytes (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Effect of acute cold (first day for 3 h) and chronic cold exposure (4°C) on gene expression of TH and PNMT in adipocytes isolated from mesenteric adipose tissue in rats. Results are normalized relatively to the housekeeper GAPDH. Values are displayed as mean ± SEM

Effect of a Single IMO of Rats Exposed Prior IMO to Long-Term Cold (4°C for 28 days) on CAs and CA Biosynthetic Enzymes in Isolated Adipocytes and SVF

We investigated whether changes in adipocytes and SVF, induced by a single IMO at room temperature, would be affected by prior long-term cold exposure.

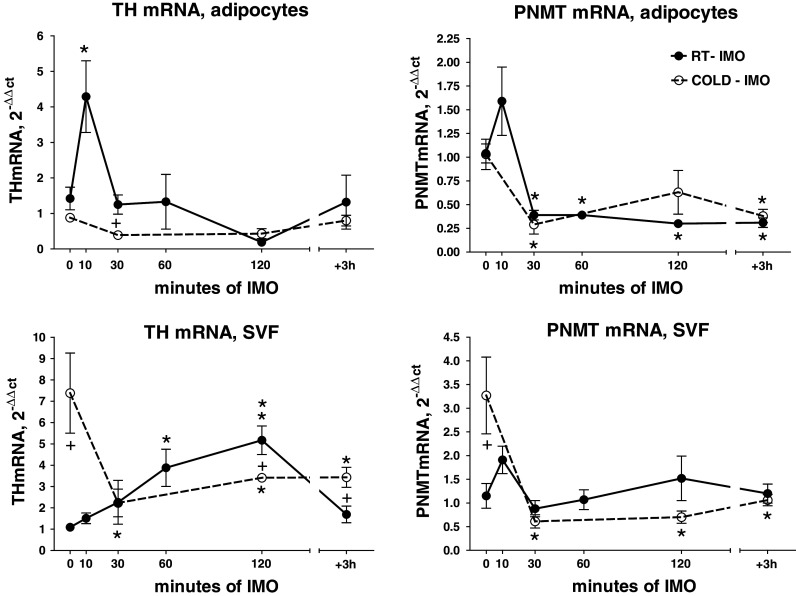

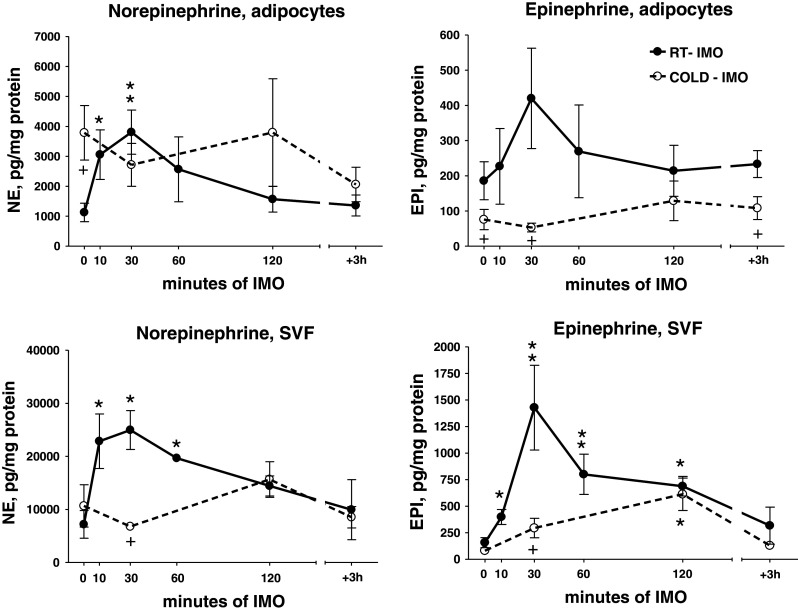

Norepinephrine concentration in various intervals of the first IMO of rats, which were accommodated at room temperature (RT-IMO) showed a significant increase especially in shorter IMO intervals, both in isolated adipocytes and SVF (Fig. 7). Adipocyte NE concentration was about 10 times lower compared to SVF. NE baseline in adipocytes of cold-adapted animals (COLD-IMO) was significantly elevated compared to absolute control group, however, exposure of such cold-adapted animals to intervals of a single IMO, completely abolished the effect of IMO. The IMO-induced NE increase in RT-IMO rats was also abolished in SVF of COLD-IMO groups (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Effect of exposure to various intervals of a single immobilization of rats at room temperature (RT-IMO) and those exposed prior immobilization to cold (4°C) for 28 days (COLD-IMO), on norepinephrine and epinephrine concentration in isolated adipocytes and stromal vascular fraction (SVF) from mesenteric adipose tissue. Values are displayed as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 versus appropriate control group, + p < 0.05 versus RT-IMO group

EPI concentration showed also increase during various intervals of the single IMO, especially in SVF of RT-IMO group. Nevertheless, EPI level was reduced in cold-adapted animals—COLD-IMO (Fig. 7).

Tyrosine hydroxylase mRNA level showed a significant rise in adipocytes and SVF in RT-IMO groups. Cold-adapted animals (COLD-IMO) did not show these IMO-induced changes (Fig. 8). Prior to IMO, cold-adapted rats had significantly higher expression of TH in SVF. However, a marked decrease was found during the first 30 min of IMO in cold-adapted group, as compared to animals housed at room temperature.

PNMT mRNA levels showed a tendency to be reduced especially in adipocytes. PNMT mRNA levels in SVF of cold-adapted control group were several fold increased, while single IMO significantly reduced them (Fig. 8).

TH and PNMT protein levels in adipocytes were not affected by a single IMO for 2 h (Fig. 9). In cold-adapted animals (COLD), the baseline was not different from absolute control group, and IMO produced a reduction of PNMT protein to not detectable (ND) values (Fig. 9). The low levels of these proteins in COLD-adapted group were most probably a consequence of adaptation of this system to chronic cold exposure.

Discussion

The first demonstration of the presence of endogenous CA biosynthetic system in adipocytes isolated from rat mesenteric adipose tissue was recently published (Vargovic et al. 2011). We found that gene expression and proteins of enzymes synthesizing CAs in adipose tissues are distributed independently on sympathetic neurons. In our previous work (Vargovic et al. 2011), we clearly demonstrated that the competitive antagonist of TH (alpha-methyl-p-tyrosine) largely reduced the levels of CAs in isolated adipocytes. These data confirmed that isolated adipocytes are able to synthesize CAs (Vargovic et al. 2011). We found that the concentration of CAs in adipocytes is relatively low; however, if we consider the total amount of adipose tissues, the whole content of CAs produced in adipocytes is quite high and is comparable to CA production in the adrenal medulla. Nevertheless, the physiological function of these endogenously produced CAs in adipocytes has not been appointed yet.

It is important to point out that isolated adipocytes used in our experiments were of high purity as described in details in the methods.

Is the endogenous CA-producing system in adipocytes affected by stress? Stress highly stimulates activity of the peripheral SAS and catecholaminergic systems in the brain (for review, see Kvetnansky et al. 2009). This activation is connected with increased release of CAs (Kvetnansky et al. 1978, 1979) from storages in various tissues (adrenal medulla, ganglionic sympathetic neurons, heart, brain, etc.) (Kvetnansky et al. 2009, 1971a, 1995, 1977; Sabban et al. 2006), elevated plasma levels of EPI and NE (Kvetnansky et al. 1978, 1979), increased turnover and spillover of CAs (Kvetnansky et al. 1971) and gene expression of enzymes involved in CA synthesis and degradation (Kvetnansky et al. 2004; Sabban and Kvetnansky 2001; Sabban et al. 2006; Kvetnansky et al. 2009), as well as CA transporters (Tillinger et al. 2010).

Adipose tissues have a rich sympathetic innervation (Bartness and Song 2007; Bartness et al. 2010; Bartolomucci et al. 82009; Brito et al. 2008; Giordano et al. 2005; Lafontan and Lagin 2009), from which NE is released in stress situations and regulates metabolic processes, e.g., lipolysis (Lafontan and Berlan 1995; Lafontan and Langin 2009; Bartness et al. 2010; Giordano et al. 2005). Is stress a factor, which could stimulate production and release of endogenous CAs in adipocytes, as in sympathetic neurons?

We investigated two different kinds of stressors: IMO stress, which represents mainly emotional stimulus and stimulates mainly EPI release from the adrenal medulla and cold stress, which is mainly a physical stimulus and almost exclusively activates release of NE from the sympathetic nerve endings (Kvetnansky et al. 1998; Goldstein and Kopin 2008). The data presented in this article clearly demonstrate that NE but also EPI levels, and components of the CA biosynthetic apparatus, are significantly activated in adipocytes isolated from stressed rats.

Besides IMO stress and cold stress, we also studied CAs in adipocytes and SVF isolated from animals exposed to cold (4°C) for 28 days and then exposed to various time intervals of a single IMO. The reason to use such animals was based on our previous data showing that animals adapted to one stressor respond by an exaggerated reaction to a second (novel) stressor (Kvetnansky et al. 2002; Dronjak et al. 2002). For example, TH mRNA levels in the adrenal medulla of rats exposed to 28 day cold are reduced almost to control values. These cold-adapted animals, however, respond to a second stressor (single IMO) by exaggerated levels of TH mRNA (Kvetnansky et al. 2002).

In this study, we have shown reduced EPI levels (Fig. 5) as well as levels of TH mRNA and PNMT mRNA (Fig. 6) in adipocytes isolated from rats exposed to long-term cold. In opposite, adipocyte NE levels have shown a significant increase in rats exposed to 28 day cold, compared to absolute control and group exposed to 3 h cold (Fig. 5). These findings suggest an increase in NE biosynthesis and storage in adipocytes of cold-adapted animals even if TH gene expression is not changed, most probably by a feed-back effect (Fig. 6).

IMO stress by itself increased parameters of CA system in adipocytes of rats accommodated to room temperature. After exposure of cold-adapted rats to various intervals of a single IMO as a new stressor, we have found an adaptation and unchanged responses in adipocyte NE and EPI levels as well as TH and PNMT mRNA levels compared to control values. This finding is completely different from that found in the adrenal medulla, where exaggerated response was detected (Kvetnansky et al. 2002). It is evident that CA biosynthesis in adipocytes is differently regulated in animals adapted to cold. The adaptation status is evidently strongly fixed, so adipocyte CA system does not respond to another stressor. Thus, in adipocytes the process of adaptation to cold is transferred also to response to novel stressor. This fact might reflect a new homeostasis due to adaptive mechanism at the central regulation and/or modification or accumulation of transcription factors in adipocytes. It has been shown that several transcription factors are involved in the regulation of CA biosynthetic enzyme gene expression during stress (Kvetnansky et al. 2009). Thus, any of promoter elements and/or transcription factors may be permanently changed in long-term cold-exposed rats and be responsible for the unchanged responses to novel stressors.

Similar finding was seen in the adrenal medulla of cold-adapted rats—TH activity and TH mRNA levels were not changed when compared to control animals. However, after exposure of cold-adapted rats to novel stressors (IMO, insulin-induced hypoglycemia, 2-deoxy-d-glucose-induced glucoprivation) these parameters showed exaggerated values (Kvetnansky et al. 2002).

Rats exposed to long-term cold showed an increase in adrenal medullary CA levels (Kvetnansky et al. 1971a). In isolated adipocytes, we have found a huge increase of NE but not EPI concentration in cold-adapted animals (28 days). Plasma NE levels were significantly elevated during the first cold exposure and a further massive increase of NE levels was seen in rats after 28 day cold exposure (around 3 times) (Dronjak et al. 2002). Plasma EPI levels, however, were not significantly changed either in first or long-term cold exposure (Dronjak et al. 2002). Thus, these data demonstrate high activation of norepinephrinergic system in long-term cold-exposed rats, with increased NE levels not only in sympathetically innervated tissues and in plasma, but also in rat adipocytes (Fig. 5). Cold-adapted rats besides the increased NE baseline also demonstrated an exaggerated NE response to a novel stressor, single IMO. The NE levels were increased two–three fold compared to IMO rats kept at room temperature (Dronjak et al. 2002). Plasma EPI levels showed also exaggerated response to this novel stressor (Dronjak et al. 2002).

Thus, stress produces huge increases in circulating CAs. Could these CAs be taken up into the adipocytes? Are isolated adipocytes able to take up CAs added to the incubation medium? There are some literary data showing that adipose tissue and human adipocytes are able to uptake and degrade CA, so it could play a role in clearance of peripheral CAs (Pizzinat et al. 1999). In our experiments, we have not detected mRNA for the specific transporter for NE (NET) in adipocytes, however, the unspecific extra-neuronal monoamine transporter (EMT) mRNA was present, but not regulated by stress. This transporter is involved in the degradation process of CA, which are in adipocytes oxidized by MAO to form deaminated products (Pizzinat et al. 1999). This would enable us to speculate that unspecific CA uptake might exist but is unlikely to be regulated in response to stress.

To determine whether isolated adipocytes actually are able to take up CAs, we incubated adipocytes in the presence of CAs, in two different concentrations: (i) similar to those found in the plasma of resting rats (200 pg of NE/ml of incubation medium; 100 pg of EPI/ml) or (ii) highly stressed rats (2,000 pg of NE/ml of incubation medium; 3,000 pg of EPI/ml). Incubation of adipocytes with low-basal NE concentration but also with high stress-like NE levels did not significantly affect intracellular NE content (not shown). Incubation with high stress-like level of EPI produced a small increase of intracellular EPI levels in adipocytes (approx. twofold) suggesting a possible small stress-induced uptake of EPI (not shown). However, the comparison of EPI concentrations in adipocytes and plasma in basal-unstressed situation, indicates that low-basal plasma levels of EPI (55 pg/ml) could hardly be the source of CAs in adipocytes where higher concentration of EPI was found (EPI—190 pg/mg prot.) unless an active transport and storage mechanisms exist within the adipose tissue. It has to be pointed out, that IMO stress, already 10 min after initiation, increases plasma EPI levels by about 50 times, while the EPI concentration in adipocytes is not changed at all (Fig. 7). Such a kinetic disparity between the circulating and adipose tissue CA levels has been found throughout the stress periods. So, the finding of the adipocyte specific EPI levels could hardly be explained by an active uptake from circulation. Thus, our data indicate that EPI levels in adipocytes are not likely to be contaminated by EPI uptake from circulation.

However, it could not be excluded that the six-fold increase in circulating NE levels contributes to the 2.5-fold increase in adipocyte NE concentration. An argument against this notion could come from the finding that adipocytes do not contain NE transporter (NET), and that there is virtually no NE uptake during in vitro incubation of adipocytes with the high stress-like levels of NE (2,000 pg/ml) (not shown). Thus, these data suggest that the stress-induced increase in adipocyte NE concentration is induced by the endogenous CA production in adipocytes.

Proteins of TH and PNMT were not changed after exposure to single IMO because of too short influence of stress stimulation (Fig. 9). Long-term cold exposure brings an adaptation of the gene expression and protein levels of CA biosynthetic enzymes, which remains at baseline levels after 28 day cold exposure (Fig. 9). However, our unpublished data have shown that repeated IMO stress elevates both TH and PNMT gene expression and protein in isolated adipocytes (Vargovic et al. unpublished data).

Our previous work has shown that longer time intervals are necessary for a stress-induced increase in TH protein levels or TH activity. A single IMO stress has not changed TH protein levels or TH activity even in the adrenal medulla (Nankova et al. 1994). This suggests that the basal TH protein level is still sufficient for CA production. After repeated IMO stress, the increase in both, TH and PNMT proteins occurs together with the rise in mRNA levels in isolated adipocytes in similar manner as in the adrenal medulla.

Moreover, discrepancy between TH mRNA and protein level might appear also due to different stability, transcription rate, post-transcriptional modifications by RNA interference or epigenetic regulation of TH and PNMT expression in adipocytes during various time intervals of stress exposure, similarly as described in other cells and tissues (Lenartowski and Goc 2011; Nakashima et al. 2007; Panayotacopoulou et al. 2005).

Besides adipocytes, we also isolated and analyzed SVF of mesenteric adipose tissue. SVF is a heterogeneous cell population derived from the adipose tissue and contains, e.g., endothelial cells, mast cells, fibroblastic pre-adipocytes, including macrophages and neuronal cells, which are a source of CA production in adipose tissue (Flierl et al. 2008; Nguyen et al. 2011). CA concentration is significantly higher in SVF when compared to adipocytes. Under stress conditions, SVF from mesenteric adipose tissue shows marked changes in CA levels and gene expression of CA-producing enzymes. In SVF of cold-adapted animals, the elevated NE and EPI levels observed in IMO animals at room temperature, were reduced except EPI levels during 120 min of IMO (Fig. 7). TH and PNMT mRNA levels were highly increased in cold-adapted animals; however, they were quickly reduced after the subsequent IMO exposure (Fig. 8). It suggests that chronic cold exposure activated CA-producing apparatus in SVF, while in adipocytes chronic cold had no effect on CA-producing enzymes. It might be explained by the presence of some sympathetic neurons expressing CA-producing apparatus in SVF. Thus, response of the CA system in SVF of cold-adapted rats is also reduced in response to IMO, as a new stressor.

As we already mentioned, SVF contains preadipocytes, fibroblasts, vascular smooth muscle cells, endothelial cells, resident monocytes, macrophages, and T lymphocytes (Weisberg et al. 2003; Xu et al. 2003; Caspar-Bauguil et al. 2005). The term SVF corresponds best to adipose tissue derived stroma cells and describes cells obtained immediately after collagenase digestion. However, the critical point is the absence of a detailed molecular and cellular characterization of cellular subpopulations within the adipose stroma. There is still a lack of information concerning the full characterization of the cell subpopulations constituting the SVF (Flierl et al. 2008; Eto et al. 2009; Yu et al. 2010; Nguyen et al. 2011). Therefore, we were unable to perform more detailed measurement of CA content in separate cell subpopulations. We hope for a shift in the knowledge as well as for technical advances, which would enable this kind of assessment in the near future.

Increased CA levels produced directly in adipocytes might be responsible for the increased mobilization of energetic substrates, which are necessary for maintaining of the stress situations. It is very probable that these endogenous CAs participate in processes of lipolysis, synthesis of cytokines, adipokines, etc. Mesenteric adipose tissue is very susceptible to changes in SAS activity due to high expression of adrenergic receptors (mainly β3 subtype) what results in high basal or stress-induced lipolysis. These processes are efficiently regulated by CAs localized in sympathetic innervation of the adipose tissue. Therefore, it is most probable that CAs produced in adipocytes would be specifically responsible for some other processes, e.g., for a direct action, such as binding in the nucleus of the adipocyte, etc.

Specific role of endogenous CAs was described in several types of immune cells (Flierl et al. 2008; Nguyen et al. 2011). CAs produced and secreted from macrophages and other phagocytes are able to activate neighboring cells via adrenergic receptors in an autocrine/paracrine manner (Spengler et al. 1994; Engler et al. 2005; Nguyen et al. 2011). Preliminary evidence suggests existence of adrenergic receptor-independent intracellular effects of CAs (Flierl et al. 2008; Buu 1993). Thus, intracellular endogenous CAs synthesized in adipocytes could be transported to the nucleus, interact with nuclear receptors and influence transcription processes via an interaction with nuclear factors, e.g., with NFκB (Bergquist et al. 2000). This process can be significantly potentiated by stress and could represent one of the functions of CAs produced in adipocytes.

An additional pathway of CAs, endogenously produced in adipocytes, could be mediated by adrenergic receptors localized in the cell nucleus. Several studies showed that β2-AR are localized not only in the membrane and cytoplasm, but also in the nucleus of various cell types (Laukova et al. 2012; Lencesova et al. 2010; Qu et al. 2008). It is suggested that some of β2-AR synthesized in the cytoplasm are trafficked onto the membrane to mediate adrenergic response, whereas other β2-AR are translocated into the nucleus to regulate gene expression (Guo and Li 2007).

Taken together, our data have demonstrated that various stressors are able to stimulate levels and production of CAs in isolated adipocytes. Long-term cold-adapted animals have shown an adaptive response even after exposure to novel stressors.

All presented data dealing with the effect of different stressors (IMO, cold, novel stressors) on endogenous CA system in adipocytes are the original data since no relevant references were found in the available literature.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Slovak Research and Development Agency (No. APVV-0088-10 and 0148–06); TRANSMED 2, ITMS: 26240120030; VEGA Grants (2/0188/09 and 2/0036/11) and EFSD New Horizonts Grant.

References

- Astori G, Vignati F, Bardelli S, Tubio M, Gola M, Albertini V, Bambi F, Scali G, Castelli D, Rasini V, Soldati GT, Moccetti T (2007) “In vitro” and multicolor phenotypic characterization of cell subpopulations identified in fresh human adipose tissue stromal vascular fraction and in the derived mesenchymal stem cells. J Transl Med 5:55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartness TJ, Bamshad M (1998) Innervation of mammalian white adipose tissue: implications for the regulation of total body fat. Am J Physiol 275:R1399–R1411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartness TJ, Song CK (2007) Sympathetic and sensory innervation of white adipose tissue. J Lipid Res 48:1655–1672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartness TJ, Shrestha YB, Vaughan CH, Schwartz GJ, Song CK (2010) Sensory and sympathetic nervous system control of white adipose tissue lipolysis. Mol Cell Endocrinol 318:34–43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartolomucci A, Cabassi A, Govoni P, Ceresini G, Cero C, Berra D, Dadomo H, Franceschini P, Dell′Omo G, Parmigiani S, Palanza P (2009) Metabolic consequences and vulnerability to diet-induced obesity in male mice under chronic social stress. PLoS ONE 4:e4331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergquist J, Ohlsson B, Tarkowski A (2000) Nuclear factor-kappa B is involved in the catecholaminergic suppression of immunocompetent cells. Ann N Y Acad Sci 917:281–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berlan M, Lafontan M (1982) The alpha 2-adrenergic receptor on human fat cells: comparative study of alpha 2-adrenergic radioligand binding and biological response. J Physiol (Paris) 78:279–287 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bottner A, Haidan A, Eisenhofer G, Kristensen K, Castle AL, Scherbaum WA, Schneider H, Chrousos GP, Bornstein SR (2001) Increased body fat mass and suppression of circulating leptin levels in response to hypersecretion of epinephrine in phenylethanolamine-N-methyltransferase (PNMT)-overexpressing mice. Endocrinology 141:4239–4246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowers RR, Festuccia WT, Song CK, Shi H, Migliorini RH, Bartness TJ (2004) Sympathetic innervation of white adipose tissue and its regulation of fat cell number. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 286:R1167–R1175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brito NA, Brito MN, Bartness TJ (2008) Differential sympathetic drive to adipose tissues after food deprivation, cold exposure or glucoprivation. Am J Physiol Regul Interg Comp Physiol 294:R1445–R1452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buu NT (1993) Uptake of 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium and dopamine in the mouse brain cell nuclei. J Neurochem 61:1557–1560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspar-Bauguil S, Cousin B, Galinier A, Segafredo C, Nibbelink M, Andre M, Casteilla L, Penicaud L (2005) Adipose tissues as an ancestral immune organ: site-specific change in obesity. FEBS Lett 579:3487–3492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dronjak S, Ondriska M, Svetlovska D, Jezova D, Kvetnansky R (2002) Effects of novel stressors on plasma catecholamine levels in rats exposed to long-term cold. In: McCarty R, Aguilera G, Sabban EL, Kvetnansky R (eds) Stress neural, endocrine and molecular studies. Taylor and Francis, London/New York, pp 83–89 [Google Scholar]

- Engler KL, Rudd ML, Ryan JJ, Stewart JK, Fischer-Stenger K (2005) Autocrine actions of macrophage-derived catecholamines on interleukin-1 beta. J Neuroimmunol 160:87–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eto H, Suga H, Matsumoto D, Inoue K, Aoi N, Kato H, Araki J, Yoshimura K (2009) Characterization of structure and cellular components of aspirated and excised adipose tissue. Plast Reconstr Surg 124(4):1087–1097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flierl MA, Rittirsch D, Huber-Lang M, Sarma JV, Ward PA (2008) Catecholamines-crafty weapons in the inflammatory arsenal of immune/inflammatory cells or opening Pandora’s box? Mol Med 14:195–204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giordano A, Frontini A, Murano I, Tonello C, Marino MA, Carruba MO, Nisoli E, Cinti S (2005) Regional-dependent increase of sympathetic innervation in rat white adipose tissue during prolonged fasting. J Histochem Cytochem 53:679–687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein DS, Kopin IJ (2008) Adrenomedullary, adrenocortical, and sympathoneural responses to stressors: a meta-analysis. Endocr Regul 42:111–119 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo NN, Li BM (2007) Cellular and subcellular distributions of β1- and β2-adrenoceptors in the CA1 and CA3 regions of the rat hippocampus. Neuroscience 146:298–305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hökfelt B (1951) Noradrenaline and adrenaline in mammalian tissues. Acta Physiol Scand 25(92):134 Suppl 92 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo LE, Kitlinska JB, Tilan JU, Li L, Baker SB, Johnson MD, Lee EW, Burnett MS, Fricke ST, Kvetnansky R, Herzog H, Zukowska Z (2007) Neuropeptide Y acts directly in the periphery on fat tissue and mediates stress-induced obesity and metabolic syndrome. Nat Med 13(7):803–811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kvetnansky R, Mikulaj L (1970) Adrenal and urinary catecholamines in rats during adaptation to repeated immobilization stress. Endocrinology 87:738–743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kvetnansky R, Weise VK, Gewirtz GP, Kopin IJ (1971a) Synthesis of adrenal catecholamines in rats during and after immobilization stress. Endocrinology 89:46–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kvetnansky R, Gewirtz GP, Weise VK, Kopin IJ (1971b) Catecholamine-synthesizing enzymes in the rat adrenal gland during exposure to cold. Am J Physiol 220:928–931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kvetnansky R, Palkovits M, Mitro A, Torda T, Mikulaj L (1977) Catecholamines in individual hypothalamic nuclei of acutely and repeatedly stressed rats. Neuroendocrinology 23:257–267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kvetnansky R, Sun CL, Lake CR, Thoa N, Torda T, Kopin IJ (1978) Effect of handling and forced immobilization on rat plasma levels of epinephrine, norepinephrine, and dopamine-beta-hydroxylase. Endocrinology 103:1868–1874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kvetnansky R, Weise VK, Thoa NB, Kopin IJ (1979) Effects of chronic guanethidine treatment and adrenal medullectomy on plasma levels of catecholamines and corticosterone in forcibly immobilized rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 209:287–291 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kvetnansky R, Pacak K, Fukuhara K, Viskupic E, Hiremagalur B, Nankova B, Goldstein DS, Sabban EL, Kopin IJ (1995) Sympathoadrenal system in stress. Interaction with the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical system. Ann N Y Acad Sci 771:131–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kvetnansky R, Pacak K, Sabban EL, Kopin IJ, Goldstein DS (1998) Stressor specificity of peripheral catecholaminergic activation. Adv Pharmacol 42:556–560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kvetnansky R, Jelokova J, Rusnak M, Dronjak S, Serova L, Nankova B, Sabban EL (2002) Novel stressors exaggerate tyrosine hydroxylase gene expression in the adrenal medulla of rats exposed to long-term cold stress. In: McCarty R, Aguilera G, Sabban EL, Kvetnansky R (eds) Stress neural, endocrine and molecular studies. Taylor and Francis, London/New York, pp 121–128 [Google Scholar]

- Kvetnansky R, Micutkova L, Rychkova N, Kubovcakova L, Mravec B, Filipenko M, Sabban EL, Krizanova O (2004) Quantitative evaluation of catecholamine enzymes gene expression in adrenal medulla and sympathetic ganglia of stressed rats. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1018:356–369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kvetnansky R, Sabban EL, Palkovits M (2009) Catecholaminergic systems in stress: structural and molecular genetic approaches. Physiol Rev 89:535–606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lafontan M, Berlan M (1995) Fat cell alpha2-adrenoceptors: the regulation of fat cell function and lipolysis. Endocr Rev 16:716–738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lafontan M, Langin D (2009) Lipolysis and lipid mobilization in human adipose tissue. Prog Lipid Res 48:275–297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laukova M, Vargovic P, Krizanova O, Kvetnansky R (2010) Repeated stress down-regulates beta 2- and alpha 2C-adrenergic receptors and up-regulates gene expression of IL-6 in the rat spleen. Cell Mol Neurobiol 30:1077–1087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laukova M, Vargovic P, Csaderova L, Chovanova L, Vlcek M, Imrich R, Krizanova O, Kvetnansky R (2012) Acute stress differently modulates beta 1, beta 2 and beta 3 adrenoceptors in T cells, but not in B cells, from the rat spleen. Neuroimmunomodulation 19:69–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenartowski R, Goc A (2011) Epigenetic, transcriptional and posttranscriptional regulation of the tyrosine hydroxylase gene. Int J Dev Neurosci 29(8):873–883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lencesova L, Sirova M, Csaderova L, Laukova M, Sulova Z, Kvetnansky R, Krizanova O (2010) Changes and role of adrenoceptors in PC12 cells after phenylephrine administration and apoptosis induction. Neurochem Int 57:884–892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin G, Garcia M, Ning H, Banie L, Guo Y-L, Lue TF, Lin C-S (2008) Defining stem and progenitor cells within adipose tissue. Stem Cells Dev 17:1053–1064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD (2001) Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 25:402–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morton RE, Evans TA (1992) Modification of the bicinchoninic acid protein assay to eliminate lipid interference in determining lipoprotein protein content. Anal Biochem 204:332–334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakashima A, Hayashi N, Kanek YS, Mori K, Sabban EL, Nagatsu T, Ota A (2007) RNAi of 14-3-3eta protein increases intracellular stability of tyrosine hydroxylase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 363(3):817–821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nankova B, Kvetnansky R, McMahon A, Viskupic E, Hiremagalu B, Frankle G, Fukuhara K, Kopin IJ, Sabban EL (1994) Induction of tyrosine hydroxylase gene expression by a nonneuronal nonpituitary-mediated mechanism in immobilization stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 91(13):5937–5941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen KD, Qiu Y, Cui X, Goh YPS, Mwangi J, David T, Mukundan L, Brombacher F, Locksley RM, Chawla A (2011) Alternatively activated macrophages produce catecholamines to sustain adaptive thermogenesis. Nature 480:104–109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panayotacopoulou MT, Malidelis Y, van Heerikhuize J, Unmehopa U, Swaab D (2005) Individual differences in the expression of tyrosine hydroxylase mRNA in neurosecretory neurons of the human paraventricular and supraoptic nuclei: positive correlation with vasopressin mRNA. Neuroendocrilogy 81(5):329–338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pendleton RG, Gessner G, Sawyer J (1978) Studies on the distribution of phenylethanolamine N-methyltransferase and epinephrine in the rat. Res Commun Chem Pathol Pharmacol 21:315–325 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pizzinat N, Marti L, Remaury A, Leger F, Langin D, Lafontan M, Carpéné C, Parini A (1999) High expression of monoamine oxidases in human white adipose tissue: evidence for their involvement in noradrenaline clearance. Biochem Pharmacol 58(11):1735–1742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu LL, Guo NN, Li BM (2008) Beta1- and beta2-adrenoceptors in basolateral nucleus of amygdala and their roles in consolidation of fear memory in rats. Hippocampus 18:1131–1139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabban EL (2007) Catecholamines in stress: molecular mechanisms of gene expression. Endocr Regul 41:61–73 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabban EL, Kvetnansky R (2001) Stress-triggered activation of gene expression in catecholaminergic systems: dynamics of transcriptional events. Trends Neurosci 24:91–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabban EL, Liu X, Serova L, Gueorguiev V, Kvetnansky R (2006) Stress triggered changes in gene expression in adrenal medulla: transcriptional responses to acute and chronic stress. Cell Mol Neurobiol 26:845–856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaffler A, Buchler C (2007) Coincise review: adipose tissue-derived stromal cells-basic and clinical implications for novel cell-based therapies. Stem Cells 25:818–827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slavin BG, Ballard KW (1978) Morphological studies on the adrenergic innervation of white adipose tissue. Anat Rec 191:377–389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spengler RN, Chensue SW, Giacherio DA, Blenk N, Kunkel SL (1994) Endogenous norepinephrine regulates tumor necrosis factor-alpha production from macrophages in vitro. J Immunol 152:3024–3031 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudo A (1985) Accumulation of adrenaline in sympathetic nerve endings in various organs of the rat exposed to swimming stress. Jpn J Pharmacol 38:367–374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudo A (1987) Adrenaline in various organs of the rat: its origin, location and diurnal fluctuacion. Life Sci 41:2477–2484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tchoukalova YD, Koutsari K, Karpyak MV, Votruba SV, Wendland E, Jensen MD (2008) Subcutaneous adipocyte size and body fat distribution. Am J Clin Nutr 87:56–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tillinger A, Sollas A, Serova LI, Kvetnansky R, Sabban EL (2010) Vesicular monoamine transporters (VMATs) in adrenal chromaffin cells: stress-triggered induction of VMAT2 and expression in epinephrine synthesizing cells. Cell Mol Neurobiol 30:1459–1465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vargovic P, Ukropec J, Laukova M, Cleary S, Manz B, Pacak K, Kvetnansky R (2011) Adipocytes as a new source of catecholamine production. FEBS Lett 585:2279–2284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisberg SP, McCann D, Desai M, Rosenbaum M, Leibel RL, Ferrante AW Jr (2003) Obesity is associated with macrophage accumulation in adipose tissue. J Clin Invest 112:1796–1808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu H, Barnes GT, Yang Q, Tan G, Yang D, Chou CJ, Sole J, Nichols A, Ross JS, Tartaglia LA, Chen H (2003) Chronic inflammation in fat plays a crucial role in the development of obesity-related insulin resistance. J Clin Invest 112:1821–1830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu G, Wu X, Dietrich MA, Polk P, Scott LK, Ptitsyn AA, Gimble JM (2010) Yield and characterization of subcutaneous human adipose-derived stem cells by flow cytometric and adipogenic mRNA analyzes. Cytotherapy 12(4):538–546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu XH, He QL, Lin ZH (2003) Effect of catecholamines on human preadipocyte proliferation and differentiation. Zhongua Xing Wai Ke Za Zhi 19:282–284 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]