Abstract

Diacylglycerol (DAG) is an important signaling phospholipid in animals, specifically binding to the C1 domain of proteins such as protein kinase C. In most plant species, however, DAG is present at low abundance, and no interacting proteins have yet been identified. As a result, it has been proposed that the signaling function of DAG has been discarded by plants during their evolution. In this mini-review, we summarize the accumulating experimental evidence which supports that notion that changes in DAG content in response to particular cues are a feature of plant cells. This behavior suggests that DAG does indeed act as a signaling molecule during plant development and in response to certain environmental stimuli.

Keywords: phospholipids, diacylglycerol, DAG, signalling, C1 domain

Introduction

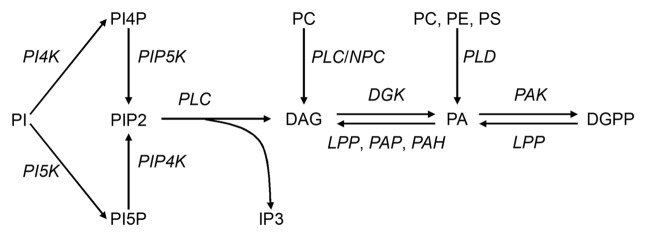

The cytoplasmic membrane comprises a phospholipid bilayer. In addition to their role as major structural components of the membrane, phospholipid molecules also act as secondary messengers since the discovery of the phosphoinositide/phospholipase C (PI/PLC) pathway.1 In this pathway, phosphoinositide is metabolized to phosphatidylinositol 4,5-biphosphate (PIP2) by two catalytic steps, and PIP2 is converted to inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate (IP3) and diacylglycerol (DAG) by PLC. DAG can also be formed from the hydrolysis of glycerophospholipid (mainly phosphatidylcholine, PC), through the action of phospholipase C (PC/PLC) (also known as non-specific PC, or NPC). DAG is later phosphorylated by diacylglycerol kinase (DGK) to form phosphatidic acid (PA), a molecule which can also be produced by PLD via the hydrolysis of structural phospholipids such as PC. PA can be converted to DAG by lipid phosphate phosphatase (LPP), phosphatidic acid phosphatase (PAP) and PA hydrolase (PAH), and specifically in plants to DAG pyrophosphate (DGPP) by PA kinase (PAK). DGPP can be converted to PA by LPPs such as diacylglycerol pyrophosphate phosphatase. The pathway involving these molecules is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. A simplified representation of phospholipid metabolism. PI, phosphoinositide; PI4P, phosphoinositide 4-phosphate; PI5P, phosphoinositide 5-phosphate; PIP2, phosphoinositide 4,5-biphosphate; DAG, diacylglycerol; IP3, inositide 1,4,5-triphosphate; PA, phosphatidic acid; DGPP, diacylglycerol pyrophosphate; PC, phosphatidylcholine; PE, phosphatidylethanolamine; PS, phosphatidylserine; PI4K, phosphoinositide 4-kinase; PI5K, phosphoinositide 5-kinase; PIP4K, phosphoinositide phosphate 4-kinase; PIP5K, phosphoinositide phosphate 5-kinase; PLC, phospholipase C; NPC, non-specific phospholipase C; PLD, phospholipase D; DGK, diacylglycerol kinase; PAK, phosphatidic acid kinase; LPP, lipid phosphate phosphatase; PAP, phosphatidic acid phosphatase; PAH, PA hydrolase.

Certain phospholipids, in particular PA and IP3, play important modulating roles in plants. PA is a key lipid signaling molecule, and its involvement in the stress response, in metabolism and in development has been recently reviewed.2 IP3 participates in the response to various abiotic stresses, gravitropism, phototropism and auxin transport.3-5 Besides these two ones, other phospholipids have been also increasingly concerned about, and their roles are found to be fantastic.

DAG is Prevalently Believed to be Out of Plant Phospholipid Signaling

The mechanics of phospholipids in signaling machinery in animals are reasonably well understood. In animal cells, IP3 binds to its receptor ligand-gated calcium channel, which triggers the release of Ca2+ from the intracellular Ca2+ reservoir to the cytoplasm.3 However, no functional plant receptor of IP3 has yet been identified, and no homologs of the animal receptor genes are present in the genomes of either Arabidopsis thaliana, rice or poplar, or in any of the publicly accessible plant EST libraries.6 As both the green alga Chlamydomonas sp and the ciliate Paramecium sp do possess such a receptor, the indication is that the IP3 receptor has been discarded during plant evolution.7 Nevertheless, IP3 accumulates in plant cells following their exposure to environmental stimuli, and its accumulation has been correlated with the mobilization of intracellular calcium.3,8,9 Perhaps, therefore, IP3 receptors differing from ligand-gated calcium channels have evolved in plants.

DAG binds specifically to its target C1 domain, a small (~50 residue) cysteine-rich structural unit originally described as a protein kinase C (PKC) lipid-binding module.10 In animal cells, DAG recruits the C1 domain-containing PKCs and PKDs onto the cytoplasmic membrane, and activates PKC via its phosphorylation; phosphorylated PKC activates PKD and triggers certain downstream signaling pathways.10 In an effort to isolate plant PKC homologs, the PKC inhibitor 1-(5-isoquinolinylsulfonyl)-2-methylpiperazine (H-7) was shown to inhibit light-stimulated stomatal opening, as well as enhancing dark-induced stomatal closure in Commelina communis; at the same time, treatment with both DAG analogs and the synthetic diacylglycerols 1,2-dihexanoylglycerol and 1,2-dioctanoylglycerol had the opposite effect on stomatal closure, thereby providing some experimental evidence for the existence of PKC in plants.11 When a Brassica campestris enzyme exhibiting the properties of a conventional mammalian PKC was activated by DAG or its analog phorbol ester and other cofactors, it was able to in vitro phosphorylate the PKC-specific substrate a-peptide.12,13 Furthermore, a potato kinase having properties similar to conventional PKC isoenzymes was restricted by the presence of PKC inhibitors in its function during pathogenesis, and the PKC activator 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol 13-acetate promoted this effect.13 Meanwhile the maize protein ZmcPKC70 proved able to bind phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate and to possess some of the properties of a conventional PKC.14 However, subsequent studies have shown that the genomes of plants, including lower plants, lack PKC encoding gene, and the effect of these PKC-specific inhibitors is most likely achieved through their interaction with protein kinases such as calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase, calcineurin B-like proteins and AGC kinases.15

As DAG is a precursor for glycolipids, storage lipids and the major structural phospholipids, which together account for about 90% of all plant lipids, it is not considered to be a plausible membrane-localized secondary messenger.15 The reason that the DAG content of plant cells is relatively low is that PLC-generated DAG is rapidly phosphorylated to PA by DGK. Thus PA (rather than DAG) has typically been implicated as a major plant secondary messenger.16-18 Thus, these findings bring about an opinion that DAG is possibly not a signaling messenger in plants.

Increasing Evidence for DAG Acting as a Signaling Molecule in Plants

The DAG content of the plant cell is low, but its presence is necessary for certain developmental processes and the response to particular environmental stimuli. DAG accumulates strongly in the apical domain of the plasma membrane at the tip of elongating tobacco pollen tube. This accumulation is abolished by treatment with U-73122, a specific inhibitor of PLC, with the result that pollen tube elongation is inhibited. The inference from this observation is that DAG probably acts as a signaling molecule in the regulation of pollen tube tip growth.19 DAG also accumulates via the PC/PLC (NPC) pathway under stressful conditions. In A. thaliana plants subjected to salinity stress, the activity of NPC was increased, promoting the production of DAG by 4-fold.20 Phosphate starvation of A. thaliana upregulates AtNPC4 and AtNPC5, which is for the accumulation of DAG and the supply of inorganic phosphate;21,22 Later during phosphate starvation, the PC content is transiently increased, before its rapid decrease which coincides with an increase in DAG content, indicating most of the newly synthesized DAG is derived via the PC/PLC pathway.23 In tobacco cell cultures, treatment with brassinolide raises the DAG content within 15 min through the elevation of PC/PLC activity in a concentration-dependent manner; at the same time the size of the PA pool is not significantly increased.24 The DAG content of Dunaliella salina cells is rather high in comparison with most animal tissues, particularly in the chloroplast and plasma membrane. When confronted with osmotic shock, the plasma membrane DAG content increases markedly to a level sufficient to consider DAG to be a genuine potential secondary messenger in PLC-mediated signal transduction.25

DAG is rapidly converted to PA in plant cells, but some reports have suggested that the decrease in DAG content is not accompanied by any increase in that of PA. In parsley and tobacco cell suspensions elicited by fungal glycoprotein or Phytophthora cryptogea cryptogein, the DAG pool declines within 15 min and PC/PLC activity is also reduced, while the content of PA rises slightly from a low background level.26,27 This observation has been taken to indicate that the decrease in DAG content is largely the result of the downregulation of the PC/PLC pathway rather than to its conversion to PA. In AlCl3 treated tobacco BY-2 cells, the activity of PC/PLC is restricted, with the result that their DAG content is rapidly and greatly reduced, while at the same time there is no observable effect on the activity of any of the enzymes involved in the catalysis of DAG to PA and other products, and the contents of these products are also not altered.28 Elongating tobacco pollen tubes incubated in vitro in the presence of various concentrations of AlCl3 suffer a growth restriction, and their DAG content is also significantly reduced in a concentration-dependent fashion. The exogenous supply of DAG can relieve this growth restriction, but the supply of exogenous PA has a much smaller effect.28 Along with the observations of Helling et al.,19 this result demonstrates that DAG itself most likely serves as a signaling molecule.

Environmental stress can induce the transcription of a number of genes encoding enzymes involved in the catalysis from PA to DAG in some plant species. The A. thaliana gene AtLPP1 encodes a lipid phosphate phosphatase which catalyzes the conversion of DGPP to PA, and then of PA to DAG. Its transcription can be rapidly (though transiently) induced by γ or UV-B irradiation, and can also be elicited by the presence of harpin, a molecule associated with oxidative stress.29 Transcript of the two Vigna unguiculata phosphatidic acid phosphatase genes VuPAPα and VuPAPβ accumulates in the leaf in response either to the progressive dehydration of the whole plant or the rapid desiccation of detached tissue, and the expression of VuPAPβ can also be induced by the supply of abscisic acid.30 Because the increases in PA and DGPP levels in response to stress are transient, PAK and PAP appear to be important attenuators for the regulation of PA signaling events.16,31 For example, AtLPP2 functions as a negative regulator of PA-mediated ABA signaling during germination.32 However, apart from the attenuating effect of PAP, there is the intriguing possibility that DAG acts antagonistically to PA.

The role of DAG as a secondary messenger is achieved through its binding to target proteins, except for DGK functioning in conversion DAG to PA. Although higher plants lack genes encoding PKCs, they do possess genes encoding a variety of C1 domain containing proteins. The A. thaliana genome, for example, includes 164 such genes (www.arabidopsis.org), while 22 are known in the rice genome genome (rice.plantbiology.msu.edu). This indicates that although it has been assumed by default that PKCs are the sole target of DAG, it is possible that other proteins—possibly even some lacking kinase activity—could represent the prime DAG targets in the plant cells. A number of proteins unrelated to PKC are capable of high affinity binding with the DAG analog phorbol ester, which suggests a measure of complexity in the signaling pathways activated by DAG.33 The bread wheat gene TaCHP, for example, which confers an enhanced level of both salinity and drought tolerance,34 encodes a protein carrying three C1 domains. Its gene product has transactivation activity but no PKC activity.35

A body of experimental evidence supports the idea that DAG does indeed function as a signaling molecule in plants, although convincing proof of this idea is not yet forthcoming. At the same time, DAG represents a major component of the structure and dynamics of plant membranes, and any excessive accumulation can induce the formation of unstable and asymmetric regions, which are required for membrane fusion and ðssion.36,37 Membrane fusion is involved in a range of physiological processes, the most notable of which is cell division. Thus the supply of exogenous DAG or its endogenous PLC-induced production promotes membrane fusion,38,39 and in this way regulates pollen tube growth via the acceleration of cell division.19,28

Conclusions and Perspectives

The question as to whether or not DAG serves as a signaling molecule in plants remains unresolved. The DAG content of plant cells is typically low, and no target plant protein participating in signal transduction has yet been identified. However, DAG content is known to fluctuate in response to a variety of developmental and environmental cues. Therefore, it would be academically significant to decode its acting mechanisms, and a critical requirement in establishing DAG's role as a signaling molecule is to identify its binding target(s). Besides, the plant/animal kingdom divergence with respect to the DAG-mediated phospholipids signaling pathway remains an intriguing puzzle.

Acknowledgments

This research was financially supported by the Natural Science Foundation of China (31171175), the National Basic Research 973 Program of China (2009CB118300 and 2012CB114200), the Major Program of the Natural Science Foundation of China (31030053), and the National Transgenic Project (2009ZX08009-082B and 2008ZX08002-002).

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/psb/article/19644

References

- 1.Munnik T, Irvine RF, Musgrave A. Phospholipid signalling in plants. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1389:222–72. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2760(97)00158-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Testerink C, Munnik T. Molecular, cellular, and physiological responses to phosphatidic acid formation in plants. J Exp Bot. 2011;62:2349–61. doi: 10.1093/jxb/err079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Im YJ, Phillippy BQ, Perera IY. InsP3 in Plant Cells. In Munnik T. Lipid Signaling in Plants, Plant Cell Monographs 16. Springer, Verlag Berlin Heidelberg. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Salinas-Mondragon RE, Kajla JD, Perera IY, Brown CS, Sederoff HW. Role of inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate signalling in gravitropic and phototropic gene expression. Plant Cell Environ. 2010;33:2041–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2010.02204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang J, Vanneste S, Brewer PB, Michniewicz M, Grones P, Kleine-Vehn J, et al. Inositol trisphosphate-induced Ca2+ signaling modulates auxin transport and PIN polarity. Dev Cell. 2011;20:855–66. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krinke O, Novotń Z, Valentová O, Martinec J. Inositol trisphosphate receptor in higher plants: is it real? J Exp Bot. 2007;58:361–76. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erl220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wheeler GL, Brownlee C. Ca2+ signalling in plants and green algae--changing channels. Trends Plant Sci. 2008;13:506–14. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2008.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DeWald DB, Torabinejad J, Jones CA, Shope JC, Cangelosi AR, Thompson JE, et al. Rapid accumulation of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate and inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate correlates with calcium mobilization in salt-stressed arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2001;126:759–69. doi: 10.1104/pp.126.2.759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Williams ME, Torabinejad J, Cohick E, Parker K, Drake EJ, Thompson JE, et al. Mutations in the Arabidopsis phosphoinositide phosphatase gene SAC9 lead to overaccumulation of PtdIns(4,5)P2 and constitutive expression of the stress-response pathway. Plant Physiol. 2005;138:686–700. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.061317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Colón-González F, Kazanietz MG. C1 domains exposed: from diacylglycerol binding to protein-protein interactions. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1761:827–37. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2006.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee Y, Assmann SM. Diacylglycerols induce both ion pumping in patch-clamped guard-cell protoplasts and opening of intact stomata. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:2127–31. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.6.2127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nanmori T, Taguchi W, Kinugasa M, Oji Y, Sahara S, Fukami Y, et al. Purification and characterization of protein kinase C from a higher plant, Brassica campestris L. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;203:311–8. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.2183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Subramaniam R, Després C, Brisson N. A functional homolog of mammalian protein kinase C participates in the elicitor-induced defense response in potato. Plant Cell. 1997;9:653–64. doi: 10.1105/tpc.9.4.653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chandok MR, Sopory SK. ZmcPKC70, a protein kinase C-type enzyme from maize. Biochemical characterization, regulation by phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate and its possible involvement in nitrate reductase gene expression. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:19235–42. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.30.19235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Munnik T, Testerink C. Plant phospholipid signaling: “in a nutshell”. J Lipid Res. 2009;50(Suppl):S260–5. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R800098-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Testerink C, Munnik T. Phosphatidic acid: a multifunctional stress signaling lipid in plants. Trends Plant Sci. 2005;10:368–75. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang X, Devaiah SP, Zhang W, Welti R. Signaling functions of phosphatidic acid. Prog Lipid Res. 2006;45:250–78. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2006.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Munnik T. Phosphatidic acid: an emerging plant lipid second messenger. Trends Plant Sci. 2001;6:227–33. doi: 10.1016/S1360-1385(01)01918-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Helling D, Possart A, Cottier S, Klahre U, Kost B. Pollen tube tip growth depends on plasma membrane polarization mediated by tobacco PLC3 activity and endocytic membrane recycling. Plant Cell. 2006;18:3519–34. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.047373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kocourková D, Krcková Z, Pejchar P, Veselková Š, Valentová O, Wimalasekera R, et al. The phosphatidylcholine-hydrolysing phospholipase C NPC4 plays a role in response of Arabidopsis roots to salt stress. J Exp Bot. 2011;62:3753–63. doi: 10.1093/jxb/err039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nakamura Y, Awai K, Masuda T, Yoshioka Y, Takamiya K, Ohta H. A novel phosphatidylcholine-hydrolyzing phospholipase C induced by phosphate starvation in Arabidopsis. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:7469–76. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408799200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gaude N, Nakamura Y, Scheible WR, Ohta H, Dörmann P. Phospholipase C5 (NPC5) is involved in galactolipid accumulation during phosphate limitation in leaves of Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2008;56:28–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03582.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jouhet J, Maréchal E, Bligny R, Joyard J, Block MA. Transient increase of phosphatidylcholine in plant cells in response to phosphate deprivation. FEBS Lett. 2003;544:63–8. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(03)00477-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wimalasekera R, Pejchar P, Holk A, Martinec J, Scherer GFE. Plant phosphatidylcholine-hydrolyzing phospholipases C NPC3 and NPC4 with roles in root development and brassinolide signaling in Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol Plant. 2010;3:610–25. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssq005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ha KS, Thompson GA., Jr Diacylglycerol Metabolism in the Green Alga Dunaliella salina under Osmotic Stress : Possible Role of Diacylglycerols in Phospholipase C-Mediated Signal Transduction. Plant Physiol. 1991;97:921–7. doi: 10.1104/pp.97.3.921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scherer GFE, Paul RU, Holk A, Martinec J. Down-regulation by elicitors of phosphatidylcholine-hydrolyzing phospholipase C and up-regulation of phospholipase A in plant cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;293:766–70. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(02)00292-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scherer GFE, Paul UR, Holk A. Phospholipase A2 in auxin elicitor signal transduction in cultured parsley cells (Petroselium crispum L.) Plant Growth Regul. 2000;32:123–8. doi: 10.1023/A:1010741209192. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pejchar P, Potocký M, Novotń Z, Veselková Š, Kocourková D, Valentová O, et al. Aluminium ions inhibit the formation of diacylglycerol generated by phosphatidylcholine-hydrolysing phospholipase C in tobacco cells. New Phytol. 2010;188:150–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03349.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pierrugues O, Brutesco C, Oshiro J, Gouy M, Deveaux Y, Carman GM, et al. Lipid phosphate phosphatases in Arabidopsis. Regulation of the AtLPP1 gene in response to stress. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:20300–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009726200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.França MGC, Matos AR, D’arcy-Lameta A, Passaquet C, Lichtlé C, Zuily-Fodil Y, et al. Cloning and characterization of drought-stimulated phosphatidic acid phosphatase genes from Vigna unguiculata. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2008;46:1093–100. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nakamura Y, Ohta H. Phosphatidic acid phosphatases in seed plants. In Munnik T. Lipid Signaling in Plants, Plant Cell Monographs 16. Springer, Verlag Berlin Heidelberg. 2010; 131-141. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Katagiri T, Ishiyama K, Kato T, Tabata S, Kobayashi M, Shinozaki K. An important role of phosphatidic acid in ABA signaling during germination in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2005;43:107–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02431.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kazanietz MG. Novel “nonkinase” phorbol ester receptors: the C1 domain connection. Mol Pharmacol. 2002;61:759–67. doi: 10.1124/mol.61.4.759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li C, Lv J, Zhao X, Ai X, Zhu X, Wang M, et al. TaCHP: a wheat zinc finger protein gene down-regulated by abscisic acid and salinity stress plays a positive role in stress tolerance. Plant Physiol. 2010;154:211–21. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.161182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhao X, Wang M, Quan T, Xia G. The role of TaCHP in salt stress responsive pathways. Plant Signal Behav. 2012;7:71–4. doi: 10.4161/psb.7.1.18547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carrasco S, Mérida I. Diacylglycerol, when simplicity becomes complex. Trends Biochem Sci. 2007;32:27–36. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2006.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Haucke V, Di Paolo G. Lipids and lipid modifications in the regulation of membrane traffic. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2007;19:426–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2007.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goñi FM, Alonso A. Structure and functional properties of diacylglycerols in membranes. Prog Lipid Res. 1999;38:1–48. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7827(98)00021-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gómez-Ferńndez JC, Corbalán-García S. Diacylglycerols, multivalent membrane modulators. Chem Phys Lipids. 2007;148:1–25. doi: 10.1016/j.chemphyslip.2007.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]