Abstract

Comment on: Lee J, et al. Mol Cell 2012; 45:836-43.

At some point during early biotic evolution, regulatory systems developed to control the production of RNAs that are used for protein synthesis. This was a winning strategy for life as we know it, since organisms from bacteria to man have robust control mechanisms to limit the production of rRNA, ribosomal protein mRNA and tRNA when nutritional or environmental conditions are no longer suitable for cell growth. The teleological argument supporting this biological imperative is based in part on the high energetic cost of ribosome and tRNA synthesis, which accounts for > 80% of gene transcription in growing cell populations.1

In eukaryotes, the rapamycin-sensitive TOR signaling pathway plays a major role in regulating growth-related processes, including ribosome and tRNA synthesis.2 How this control is achieved is a subject of considerable importance, because the deregulation of both TOR signaling and ribosome synthesis is a frequent occurrence in cancer.3,4 However, the molecules downstream of TOR that mediate transcriptional control of cell growth have been difficult to identify. One reason may have to do with the action of other signaling pathways obscuring the biological readout when TOR signaling is perturbed. Another reason may be the distribution of the effects of TOR signaling among multiple targets in the transcription machinery. These issues tend to be less confounding for TOR regulation of tRNA gene transcription by RNA polymerase (pol) III.

The pol III system is relatively simple, comprising minimally two general transcription factors (GTFs, a total of nine polypeptides) and the polymerase. Pol III transcription, especially of tRNA genes, is very active and, in yeast, is under negative regulatory control by a single conserved transcriptional repressor, Maf1.5 Although, not essential for yeast cell viability, Maf1 is essential for repression of pol III transcription under all tested conditions of nutrient limitation, environmental and cellular stress and generates an all-or-none response with acute treatments.5 Maf1 is a terminal target of the signaling pathways that regulate pol III transcription: its function is negatively regulated by PKA and the TORC1-regulated kinase Sch9, which phosphorylate overlapping sites, and it interacts with the polymerase and one of the GTFs (Brf1) to inhibit transcription. Having such regulatory power invested in a single protein seems like a poor strategy for biological control. However, studies suggest that dephosphorylation of Maf1 is not sufficient to enable Maf1-dependent repression.6,7 Recently, the pursuit of this observation has led to the identification of conserved kinases of the LAMMER/Cdc-like and GSK3 families (Kns1 and Mck1, respectively) as downstream effectors of TOR signaling. Both kinases are required for efficient repression of ribosome and tRNA synthesis under various stress conditions.8

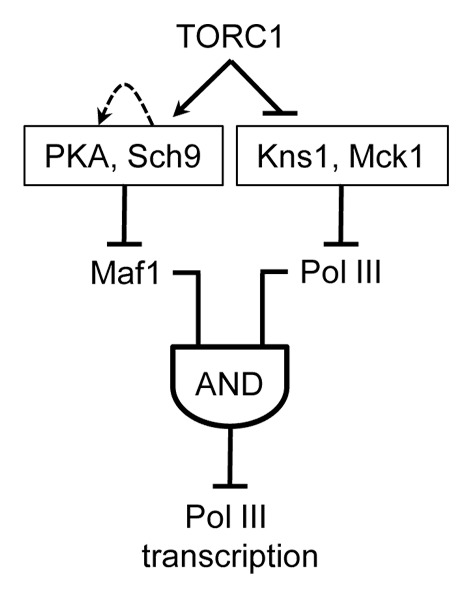

The new work reveals that RNA polymerase III itself is a target of the TOR pathway. Under repressing conditions (including rapamycin treatment), Kns1 phosphorylation of Rpc53, a TFIIF-like subunit of pol III, at a single site primes further phosphorylation by Mck1 at adjacent sites. Mutagenesis of these sites demonstrates their importance for transcriptional repression, but only in the context of a hypomorphic allele of another polymerase subunit, Rpc11. The requirement of Rpc11 for facilitated reintiation by pol III and the inability of Maf1 to inhibit this mode of transcription in vitro suggested a mechanistic model for how changes in pol III function may lead to Maf1-dependent repression.8 Further studies are needed to test this model and to explore other aspects of pol III regulation that emerge from the work. Among these, additional targets of Kns1 and/or Mck1 in the pol III machinery are suggested by the enhanced attenuation of repression seen in the kns1Δ mck1Δ strain compared with the single gene-deletion strains. While a complete picture is still lacking, the new findings reveal a branched network structure downstream of TORC1 that is similar to AND-gated feedforward loops (Fig. 1). This network architecture minimizes the likelihood of inappropriate changes in transcription due to stochastic fluctuations.

Figure 1. Network architecture model for TOR complex 1 regulation of tRNA gene transcription. The data suggest that signaling kinases downstream of TORC1 function in separate branched pathways to control the repressing function of Maf1 and the ability of pol III to be repressed by Maf1.8 Robust repression of tRNA gene transcription requires both branches and is represented by an AND-gated feedforward loop.

Inhibition of TORC1 was found to increase the expression, hyperphosphorylation and nuclear abundance of Kns1. Moreover, artificially increasing the amount of Kns1 was sufficient to cause hyperphosphorylation of Rpc53.8 It remains to be determined, however, whether TORC1 control of Kns1 involves transcriptional and/or post-transcription mechanisms. Interestingly, studies on the insulin-regulated homolog of Kns1 in the mouse, Clk2, have shown that the abundance of the protein is positively regulated by autophosphorylation following Akt phosphorylation of its activation loop.9

The discovery of two protein kinases not previously implicated in responses downstream of TORC1 raises many new questions. Beyond the regulation of pol III transcription, it will be interesting to know the identity of the transcriptional regulators that mediate the effects of Kns1 and Mck1 on ribosome synthesis and whether the function of these kinases is important for other TOR-regulated processes.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/cc/article/21257

References

- 1.Warner JR. Trends Biochem Sci. 1999;24:437–40. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(99)01460-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wullschleger S, et al. Cell. 2006;124:471–84. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zoncu R, et al. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2011;12:21–35. doi: 10.1038/nrm3025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.White RJ. RNA polymerases I and III, non-coding RNAs and cancer. Trends Genet. 2008;24:622–9. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2008.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Upadhya R, et al. Mol Cell. 2002;10:1489–94. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(02)00787-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moir RD, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:15044–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607129103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huber A, et al. Genes Dev. 2009;23:1929–43. doi: 10.1101/gad.532109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee J, et al. Mol Cell. 2012;45:836–43. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rodgers JT, et al. Cell Metab. 2010;11:23–34. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]