Abstract

Background

Transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) is an important regulator of cell migration and plays a role in the scarring response in injured brain. It is also reported that 5-lipoxygenase (5-LOX) and its products, cysteinyl leukotrienes (CysLTs, namely LTC4, LTD4 and LTE4), as well as cysteinyl leukotriene receptor 1 (CysLT1R) are closely associated with astrocyte proliferation and glial scar formation after brain injury. However, how these molecules act on astrocyte migration, an initial step of the scarring response, is unknown. To clarify this, we determined the roles of 5-LOX and CysLT1R in TGF-β1-induced astrocyte migration.

Methods

In primary cultures of rat astrocytes, the effects of TGF-β1 and CysLT receptor agonists on migration and proliferation were assayed, and the expression of 5-LOX, CysLT receptors and TGF-β1 was detected. 5-LOX activation was analyzed by measuring its products (CysLTs) and applying its inhibitor. The role of CysLT1R was investigated by applying CysLT receptor antagonists and CysLT1R knockdown by small interfering RNA (siRNA). TGF-β1 release was assayed as well.

Results

TGF-β1-induced astrocyte migration was potentiated by LTD4, but attenuated by the 5-LOX inhibitor zileuton and the CysLT1R antagonist montelukast. The non-selective agonist LTD4 at 0.1 to 10 nM also induced a mild migration; however, the selective agonist N-methyl-LTC4 and the selective antagonist Bay cysLT2 for CysLT2R had no effects. Moreover, CysLT1R siRNA inhibited TGF-β1- and LTD4-induced astrocyte migration by down-regulating the expression of this receptor. However, TGF-β1 and LTD4 at various concentrations did not affect astrocyte proliferation 24 h after exposure. On the other hand, TGF-β1 increased 5-LOX expression and the production of CysLTs, and up-regulated CysLT1R (not CysLT2R), while LTD4 and N-methyl-LTC4 did not affect TGF-β1 expression and release.

Conclusions

TGF-β1-induced astrocyte migration is, at least in part, mediated by enhanced endogenous CysLTs through activating CysLT1R. These findings indicate that the interaction between the cytokine TGF-β1 and the pro-inflammatory mediators CysLTs in the regulation of astrocyte function is relevant to glial scar formation.

Keywords: Transforming growth factor-β1, Cysteinyl leukotriene, Cysteinyl leukotriene receptor, 5-lipoxygenase, Astrocyte, migration, Glial scar

Background

Glial scar formation is a critical event in repair responses after injury of the central nervous system (CNS) [1,2]. The glial scar is a complex of cellular components and mainly consists of reactive astrocytes (undergoing proliferation and morphological changes). Following focal CNS injury, reactive astrocytes migrate towards the lesion and then organize into a densely packed glial scar [1,2]. As the key step of glial scar formation, astrocyte migration is regulated by various factors [3-5], among which transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) is known as an important regulator [5,6].

TGF-β, a family of multifunctional cytokines, regulates a broad diversity of physiological and pathological processes, including wound healing, inflammation, cell proliferation, differentiation, migration and extracellular matrix synthesis [7-10]. TGF-β1 is an important mediator in the pathogenesis of several disorders in the CNS, such as in the organization of a glial scar in response to injury and in several neurodegenerative disorders [7,11,12]. After CNS injury, elevated TGF-β levels in astrocytes have been shown to induce astrocytic scar formation [13], and are also associated with ischemic brain injury [14,15].

On the other hand, cysteinyl leukotrienes (CysLTs, namely LTC4, LTD4, and LTE4), the 5-lipoxygenase (5-LOX, EC 1.13.11.34) metabolites of arachidonic acid [16], are bioactive lipid mediators that modulate immune and inflammatory responses [16-19] through activating their receptors, CysLT1R and CysLT2R [17,20,21]. In the rat brain, 5-LOX is activated and the production of CysLTs is enhanced after focal cerebral ischemia, resulting in neuronal injury and astrocyte proliferation (astrocytosis). This post-ischemic astrocytosis is associated with up-regulated CysLT1R and CysLT2R [22-26]. The CysLT1R antagonist pranlukast attenuates post-ischemic astrocytosis and glial scar formation in the chronic phases of focal cerebral ischemia in mice and rats [25,27,28]. This effect suggests that CysLT1R mediates CysLT-induced astrocytosis and glial scar formation in response to in vivo ischemic injury. In primary astrocyte cultures, CysLTs are released after oxygen-glucose deprivation-induced ischemic injury, and the resultant activation of CysLT1R mediates astrocyte proliferation [29,30]. These findings imply that the endogenously released CysLTs might play an autocrine role in the induction of astrocytosis and resultant glial scar formation through activating CysLT1R.

However, whether CysLT1R mediates astrocyte migration in the process of glial scar formation needs investigation. In the periphery, CysLT1R mediates migration in many types of cells, such as monocytes [31], dendritic cells [32], monocyte-derived dendritic cells [33], vascular smooth muscle cells [34], intestinal epithelial cells [35] and endothelial cells [31,34-36]. Therefore, CysLT1R may also be an inducer of astrocyte migration, but many other factors have been reported to be potent inducers, such as TGF-β1 [37,38]. Thus, there may be interactions between CysLT1R and other regulators (for example, TGF-β1). TGF-β1 up-regulates CysLT1R expression and increases the production of CysLTs in several cell types such as hepatic stellate cells [39] and bronchial smooth muscle cells [37]. Based on these findings, it is possible that the regulatory role of TGF-β1 in astrocyte migration may be mediated by enhanced production of CysLTs via CysLT1R activation. To clarify this possibility, in the present study, we investigated the interactions between TGF-β1 and 5-LOX/CysLT1R in astrocyte migration.

Methods

Primary cultures of rat astrocytes

Primary astrocytes were isolated from the cerebral cortex of newborn Sprague–Dawley rats within 24 h as described previously [30,40]. In brief, the cortices were digested with 0.25% trypsin and plated into poly-L-lysine-coated flasks. Cells were cultured in high-glucose DMEM (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 2 mM glutamine, 100 units/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 95% air/5% CO2. After incubation for 11 to 14 days, the confluent cultures were shaken overnight at 260 rpm at 37°C, and the adherent cells were trypsinized and re-seeded in the growth medium. More than 95% of the cells were astrocytes as confirmed by immunofluorescence staining for glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP).

All animal experiments were carried out in accordance with the National Institutes of Heath Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. We made every effort to minimize the number of animals used and their suffering. The experimental protocols were approved by the Ethics Committee of Laboratory Animal Care and Welfare, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University.

Cell migration (wound healing) assay

Astrocytes were grown to confluence in 24-well plates and starved in serum-free DMEM for 24 h. The monolayer cells were manually scratched with a 20-μl pipette tip to create an extended and definite scratch in the center of the dish with a bright and clear field. The detached cells were removed by washing with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). DMEM containing 1% FBS with or without TGF-β1 (PeproTech Inc, Rocky Hill, NJ, USA) was added to each dish. In some experiments, 1 ng/ml TGF-β1 was added to each dish for 30 minutes before treatment with LTD4 (Sigma-Aldrich Co., St Louis, MO, USA) or N-methyl LTC4 (NMLTC4, a metabolically stable LTC4 mimetic; Cayman Chemical Co., Ann Arbor, MI, USA). Cells were pretreated with the following inhibitor and antagonists: zileuton (0.01 to 5 μM, a 5-LOX inhibitor; Gaomeng Pharmaceutical Co., Beijing, China), montelukast (0.01 to 5 μM, a selective CysLT1R antagonist; Merck & Co., Inc., Whitehouse Station, NJ, USA), and Bay cysLT2 (0.01 to 5 μM, a selective CysLT2R antagonist; a kind gift from Dr. T. Jon Seiders of Amira Pharmaceuticals, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) for 30 minutes, and then incubated with TGF-β1 for 24 h. Images of migratory cells from the scratch boundary were acquired at 0 and 24 h under a light microscope with a digital camera.

To continuously monitor migration time-course in live astrocytes, astrocytes were plated in 35-mm dishes and grown to confluence, and then the cells were scratched and treated with LTD4 or/and TGF-β1 as described above. The movements of live astrocytes was traced under an inverse videomicroscope (Olympus IX81, Olympus Corp., Tokyo, Japan), and the wound was photographed at 0, 6, 12, 18 and 24 h.

The wounded areas were analyzed with ImageTool 2.0 software (University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio, TX, USA). The wound healing effect is determined as the initial scratch area (0 h) after wounding minus the scratch area after treatment for 24 h, or 6, 12, 18 and 24 h (live astrocytes), and reported as percentages of control values. Moreover, some astrocyte samples seeded on coverslips were visualized by GFAP immunofluorescence staining 24 h after scratching as the typical images.

Cell proliferation assay

To measure astrocyte proliferation, carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE) green fluorescent dye (Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, CA, USA) dilution assay was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions and the reported method [41-43]. Briefly, astrocytes were grown to confluence in six-well plates and starved in serum-free DMEM for 24 h, then the cells were washed twice with PBS and incubated in 5 μM CFSE in PBS for 15 minutes at 37°C, and subsequently washed twice with PBS. Then DMEM containing 1% FBS with or without TGF-β1 or LTD4 was added to each plate. In some experiments, 1 ng/ml TGF-β1 was added to each plate for 30 minutes before treatment with LTD4. The cells were harvested at 24 h, and subjected to fluorescence activated cell sorting using the FC500MCL flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter, Inc., Brea, CA, USA). Proliferation was measured by loss of CFSE dye.

CysLT1 receptor knockdown by small interfering RNA (siRNA)

RNA duplexes of 21 nucleotides specific for rat CysLT1R sequences were chemically synthesized, together with a non-silencing negative control siRNA. The CysLT1R siRNA sense sequence was: 5′-CAG CCU UCC AAG UAU ACA UTT-3′ and anti-sense: 5′-AUG UAU ACU UGG AAG GCU GTT-3′; the non-silencing control siRNA sense: 5′-UUC UCC GAA CGU GUC ACG UTT-3′ and anti-sense: 5′-ACG UGA CAC GUU CGG AGA ATT-3′ (GenePharma Co., Shanghai, China). Transfection of siRNA duplexes was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, astrocytes were seeded on the day before transfection using an appropriate medium with 10% FBS without antibiotics. They were transiently transfected with CysLT1R siRNA or negative control siRNA (100 nM) for 6 h using Lipofectamine™ 2000 (Invitrogen, USA). After the transfected cells were incubated for 48 h, they were treated with LTD4 or TGF-β1 for cell migration assay.

Reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)

At the end of the experiments, total RNA was extracted from the cultured astrocytes using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The cDNA synthesis and PCR reactions were performed as reported previously [29,30]. The PCR primers were: 5-LOX forward 5′-AAA GAA CTG GAA ACA GCT CAG AAA-3′ and reverse 5′-AAC TGG TGT GTA CAG GGG TCA GTT-3′; CysLT1R, forward 5′- ATG TTC ACA AAG GCA AGT GG −3′ and reverse 5′-TGC ATC CTA AGG ACA GAG TCA −3′; CysLT2R, forward 5′- ACC CCT TCC AGA TGC TCC A −3′ and reverse 5′- CGT GCT TTG AAA TTC TCT CCA −3′; β-actin, forward 5′-AAC CCT AAG GCC AACCGT GAA-3′ and reverse 5′-TCA TGA GGT AGT CTG TCA GGT C-3′; TGF-β1, forward 5′- GAC CGC AAC AAC GCA ATC TA −3′ and reverse 5′- AGG TGT TGA GCC CTT TCC AG −3′.

For cDNA synthesis, 2 μg total RNA was mixed with 1 mM deoxynucleotide triphosphate, 0.2 μg random primer, 20 U RNasin and 200 U M-MuLV reverse transcriptase in 20 μl reverse reaction buffer. The mixture was incubated at 42°C for 60 minutes, and then heated at 72°C for 10 minutes to inactivate the reverse transcriptase.

PCR was performed on an Eppendorf Master Cycler (Eppendorf Scientific, Inc., Westbury, NY, USA) as follows: 1 μl cDNA mixture was reacted in 20 μl reaction buffer containing 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM deoxynucleotide triphosphate, 20 pM primer and 1 U Taq DNA polymerase. The reaction mixtures were initially heated at 94°C for 2 minutes, then at 94°C for 60 sec, 56°C for 60 sec, and 72°C for 60 sec for 35 cycles and finally stopped at 72°C for 10 minutes. With the exception of TGF-β1, the reaction mixtures were initially heated at 94°C for 2 minutes, then at 94°C for 30 sec, 54°C for 30 sec, and 72°C for 60 sec for 28 cycles and finally stopped at 72°C for 10 minutes. PCR products of 20 μl were separated by 2% agarose gel electrophoresis and visualized by ethidium bromide staining. The density of each band was measured by a UVP gel analysis system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). The results are expressed as the ratios to β-actin.

Western blotting analysis

Astrocytes were washed twice with ice-cold PBS and then lysed for 30 minutes on ice in Cell and Tissue Protein Extraction Solution (Kangcheng Biotechnology Inc., Shanghai, China). The homogenate was centrifuged at 12,000 g for 30 minutes at 4°C, and the supernatant was used. The protein samples (100 μg) were separated by 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gels and then transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Invitrogen). The membranes were blocked by 10% fat-free milk, and sequentially incubated with the following antibodies: rabbit polyclonal antibody against CysLT1R (1:200) [44], CysLT2R (1:200) [26,45] or 5-LOX (1:300, (Chemicon International Inc. Temecula, CA, USA) and mouse monoclonal antibody against glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) (1:5,000, Kangcheng Biotechnology Inc., Shanghai, China) at 4°C overnight. After repeated wash, the membranes were incubated with anti-rabbit IRDye700DX®-conjugated antibody or anti-mouse IRDye800DX®-conjugated antibody (1:5,000, Rockland Immunochemicals, Inc., Gilbertsville, PA, USA). The immunoblot was analyzed by the Odyssey Fluorescence Scanner (LI-COR Bioscience, Inc., Lincoln, NE, USA). The protein bands were quantified using BIORAD Quantity One software (Bio-Rad, USA). The results are expressed as the ratios to GAPDH.

Immunofluorescence staining

Astrocytes seeded on coverslips were fixed in cold methanol for 5 minutes, and incubated in 10% normal goat serum for 2 h to block non-specific binding of IgG. Then the cells were reacted with a mouse monoclonal antibody against GFAP (1:500, Millipore Corp., Bedford, MA, USA) and a rabbit polyclonal antibody against CysLT1R (1:200, Chemicon, USA) at 4°C overnight. After washing in PBS, astrocytes were incubated with FITC-conjugated goat anti-mouse or Cy3-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody (1:200, Millipore, USA) for 2 h at room temperature. Finally, the stained cells were observed under a fluorescence microscope (Olympus BX51, Olympus Corp., Tokyo, Japan). Control coverslips were treated with normal goat serum instead of the primary antibody, and did not show positive immunostaining (data not shown).

5-LOX immunocytochemistry

Astrocytes cultured on coverslips were fixed in cold methanol (−20°C) for 5 minutes and incubated for 30 minutes in PBS containing 3% H2O2 to eliminate endogenous peroxidase activity. Then, cells were incubated for 2 h in PBS containing 10% normal goat serum and incubated at 4°C overnight with rabbit polyclonal antibody against 5-LOX (1:200, Chemicon, USA) as the primary antibody. After three washes with PBS, cells were incubated for 2 h with biotin-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG antiserum (1:200) as a second antibody, followed by incubation with avidin-biotin-HRP complex. Finally, the cells were visualized with 0.01% 3, 3′-diaminobenzidine and 0.005% H2O2 in 50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.6. Control coverslips were treated with normal goat serum instead of the primary antibody and they did not show positive immunostaining (data not shown). Then, the cells were examined under the Olympus microscope.

Measurement of extracellular cysteinyl leukotrienes and TGF-β1

According to the reported method [29,30], astrocytes were seeded into six-well culture plates at 5 × 105 cells/well in 2 ml standard culture medium for 24 h. After culture in DMEM without serum for another 24 h, astrocytes were cultured in DMEM with 1% FBS and stimulated with TGF-β1 (10 ng/mL), various concentrations of LTD4 or NMLTC4, or vehicle for the designated times. Then, cell-free supernatants were stored at −80°C. The CysLTs (LTC4, LTD4 and LTE4) in astrocyte supernatants were assayed using a commercial CysLT ELISA kit (Cayman Chemical Co., Ann Arbor, MI, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and calculated as pg/mg protein. The TGF-β1 in the supernatants was assayed using a commercial TGF-β1 ELISA kit (Wuhan Boster Biological Technology Co., Ltd., Wuhan, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and calculated as pg/ml.

Statistical analysis

Data are reported as mean ± S.E.M. Student’s t-test and one-way analysis of variance were used to determine the statistical significance of differences between groups. A value of P <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

TGF-β1- and LTD4-induced astrocyte migration

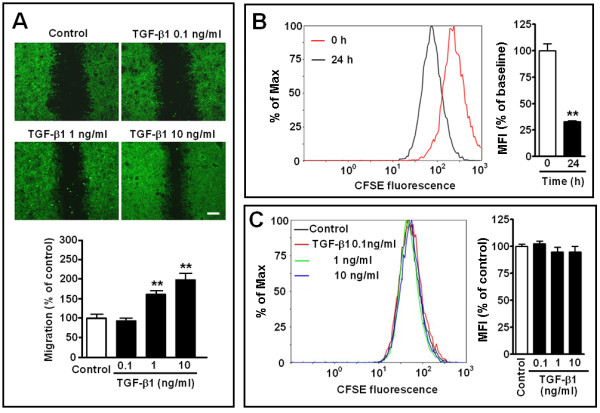

First, we confirmed the effect of TGF-β1 on astrocyte migration. TGF-β1 (1 and 10 ng/ml for 24 h) significantly accelerated the migration of astrocytes from the wound edge into the central area in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 1A). To distinguish the effects on migration and proliferation, we determined whether TGF-β1 affects astrocyte proliferation. The results of CFSE fluorescence intensity showed that astrocyte proliferation did not differ from control level 24 h after exposure to TGF-β1 (0.1, 1 and 10 ng/ml) (Figure 1C) although the assay confirmed astrocyte proliferation at 24 h compared with 0 h (baseline) (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Effect of TGF-β1 on astrocyte migration and proliferation. (A) Photomicrographs showing migration after treatment with TGF-β1 (0.1 to 10 ng/ml) for 24 h. Scale bar, 400 μm. (B, C) Fluorescence intensity was determined by fluorescence activated cell sorting after CFSE labeling at 0 (baseline) and 24 h. Mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) at 24 h reduced compared with baseline (B), but did not change 24 h after treatment with TGF-β1 (0.1, 1 and 10 ng/ml, C). Data are reported as mean ± S.E.M.; n = 8 (A), 3 (B) or 9 (C); **P <0.01 compared with control.

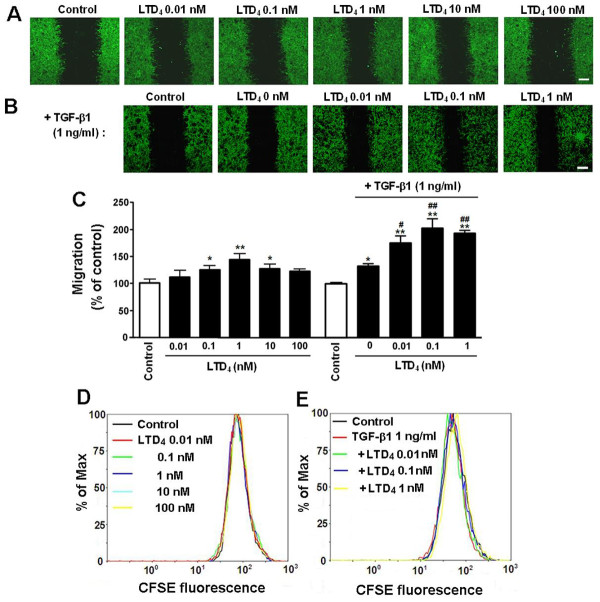

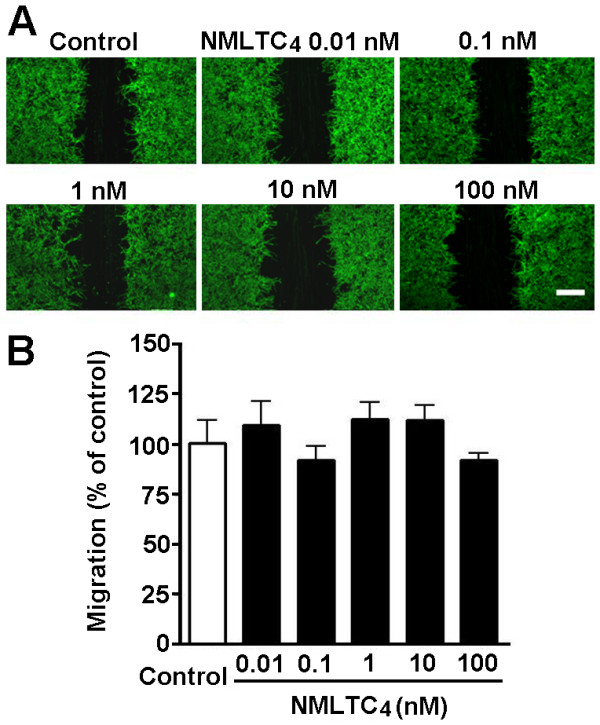

Next, we determined whether the non-selective agonist LTD4 and the CysLT2R agonist NMLTC4[46] induce astrocyte migration, and LTD4 potentiates the TGF-β1 effect. The results showed that LTD4 significantly stimulated the migration of astrocytes at 0.1 to 10 nM but not at 0.01 and 100 nM; the maximum migration (141.7 ± 5.0%) was induced by 1 nM LTD4 (Figure 2A, C). LTD4 (0.01 to 1 nM) also potentiated the effect of the lower concentration of TGF-β1 (1 ng/ml); the migration rates after treatment with 1 ng/ml TGF-β1 were increased from 110.3 ± 5.4% to 175.3 ± 4.8% with 0.01 nM, from 123.5 ± 4.0% to 203.5 ± 5.3% with 0.1 nM, and from 141.7 ± 5.0% to 193.8 ± 2.9% with 1 nM LTD4 (Figure 2B, C). LTD4 (0.01 to 100 nM) alone (Figure 2D) or combined with TGF-β1 1 ng/ml (Figure 2E) did not affect astrocyte proliferation at 24 h. However, NMLTC4 (0.01 to 100 nM for 24 h) did not have any significant effect on astrocyte migration (Figure 3). In addition, to confirm the migration and determine its temporal property, we continuously monitored migration of live astrocytes during 24 h after exposure to LTD4 or/and TGF-β1. We found that TGF-β1 (1 and 10 ng/ml) and LTD4 (1 nM) gradually accelerated migration during 24 h in a concentration-dependent manner. When TGF-β1 (1 ng/ml) combined with LTD4 (0.1 nM), the effect at 24 h was more potent than that of TGF-β1 or LTD4 alone (Figure 4).

Figure 2.

Effect of LTD4on astrocyte migration and TGF-β1-induced migration and proliferation. (A, B), Photomicrographs showing astrocyte migration 24 h after treatment with LTD4 (0.01 to 100 nmol/L) in the absence (A) or presence of TGF-β1 (1 ng/ml, B). Scale bars, 400 μm. (C) Data are reported as mean ± S.E.M.; n = 8; *P <0.05 and **P <0.01 compared with control, #P <0.05 and ##P <0.01 compared with TGF-β1 alone (LTD4 0). (D, E) MFI at 24 h was no significant change 24 h after treatment with LTD4 (0.01 to 100 nM, D) alone or combined with TGF-β1 1 ng/ml (E) (n = 9 for each group, P >0.05).

Figure 3.

Effect of NMLTC4on astrocyte migration. (A) Photomicrographs showing astrocyte migration 24 h after treatment with NMLTC4 (0.01 to 100 nmol/L). (B) Data are reported as mean ± S.E.M.; n = 8. Scale bar, 400 μm.

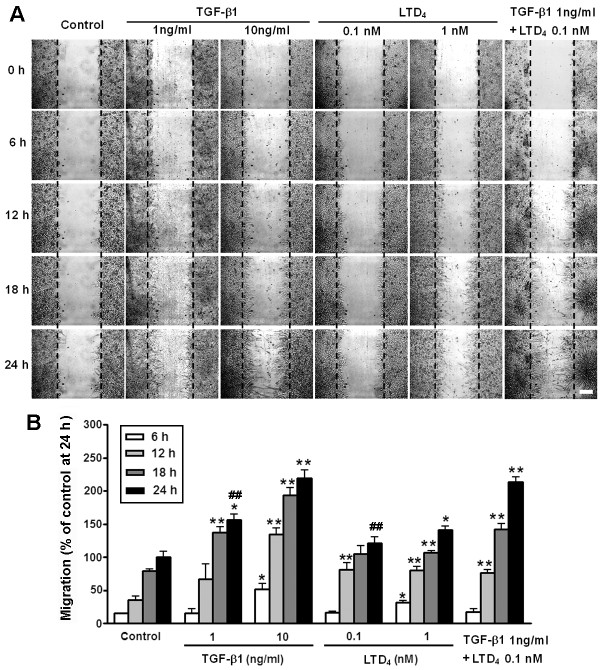

Figure 4.

Time-dependent migration of live astrocytes after exposure to TGF-β1 and LTD4. Live astrocytes were continuously monitored under a videomicroscope after exposure to TGF-β1 or/and LTD4. (A) Representative images showing astrocyte migration traced by videomicroscopy at 6, 12, 18 and 24 h after scratching. Scale bar, 200 μm. (B) TGF-β1 and LTD4 concentration- and time-dependently accelerated migration. When TGF-β1 (1 ng/ml) combined with LTD4 (0.1 nM), the effect at 24 h was more potent than that of TGF-β1 or LTD4 alone. Data are reported as mean ± S.E.M.; n = 3; *P <0.05 and **P <0.01 compared with corresponding time-points of the control; ##P <0.01 compared with TGF-β1 + LTD4 at 24 h.

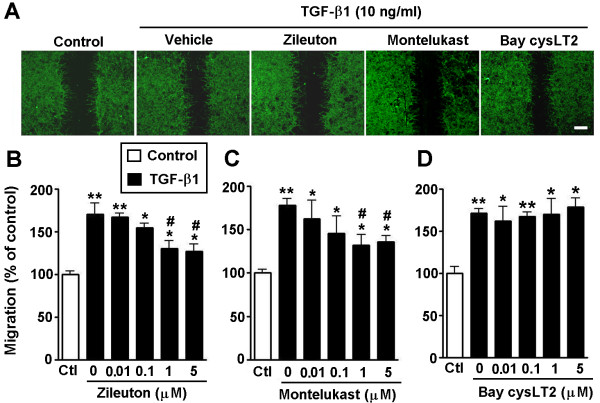

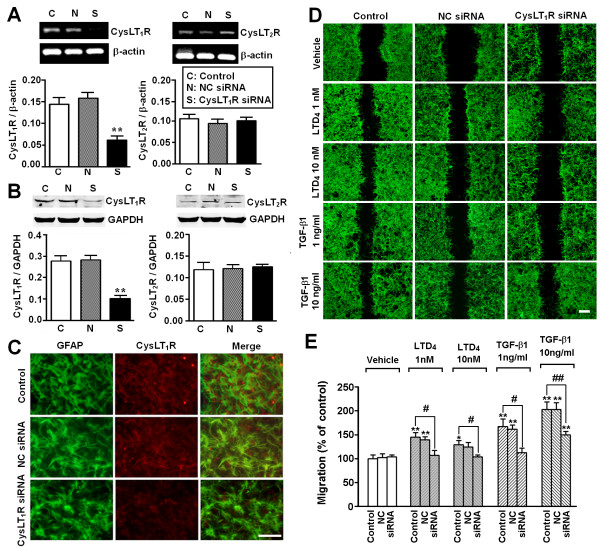

To confirm the roles of endogenous CysLTs and CysLT1R in TGF-β1-induced migration, we examined the effects of the 5-LOX inhibitor zileuton, the CysLT1R antagonist montelukast, and the CysLT2R antagonist Bay cysLT2 as well as CysLT1R siRNA. We found that the effect of 10 ng/ml TGF-β1 was attenuated by zileuton (1 and 5 μM, Figure 5A, B) and montelukast (1 and 5 μM, Figure 5A, C), but not by Bay cysLT2 (0.01 to 5 μM, Figure 5A, D). These results indicated that endogenously released CysLTs might activate CysLT1R, but not CysLT2R, to induce astrocyte migration and potentiate TGF-β1-induced migration. The involvement of CysLT1R was further confirmed by RNA silencing by transient transfection of CysLT1R siRNA into astrocytes. The siRNA (100 nM) significantly reduced the expression of CysLT1R mRNA (Figure 6A) and protein (Figure 6B, C), but the non-silencing negative control siRNA had no effect. CysLT1R siRNA significantly attenuated the effects of LTD4 (1 and 10 nM) and TGF-β1 (1 and 10 ng/ml) on astrocyte migration (Figure 6D, E). These results suggest that CysLT1R may be associated with LTD4- and TGF-β1-induced astrocyte migration.

Figure 5.

Effects of a 5-LOX inhibitor and CysLT receptor antagonists on TGF-β1-induced migration in astrocytes. (A) Photomicrographs showing TGF-β1 (10 ng/ml)-induced astrocyte migration 24 h after treatment with the 5-LOX inhibitor zileuton, the CysLT1R antagonist montelukast and the CysLT2R antagonist Bay cysLT2 (1 μM). Scale bar, 400 μm. (B-D) TGF-β1-induced migration inhibited by 0.01 to 5 μM zileuton (B) and montelukast (C), but not Bay cysLT2 (D). Data are reported as mean ± S.E.M.; n = 8; *P <0.05 and **P <0.01 compared with control; #P <0.05 compared with TGF-β1 alone.

Figure 6.

Effect of CysLT1R siRNA on LTD4- and TGF-β1-induced migration in astrocytes. (A, B) RT-PCR and Western blotting results showing inhibition of CysLT1R, but not CysLT2R, mRNA (A) and protein expression (B) by CysLT1R siRNA but not by negative control (NC) siRNA. (C) Double immunofluorescence staining showing inhibition of CysLT1R protein expression by CysLT1R siRNA in GFAP-positive astrocytes. (D) Photomicrographs showing that the astrocyte migration induced by LTD4 (1 and 10 nM) and TGF-β1 (1 and 10 ng/ml) was inhibited by CysLT1R siRNA (siRNA) but not by NC siRNA. (E) CysLT1R siRNA inhibited migration induced by LTD4 and TGF-β1. Data are reported as mean ± S.E.M.; n = 4 (A and B) or 8 (E); *P <0.05 and **P <0.01 compared with control; #P <0.05 and ##P <0.01 compared with LTD4 or TGF-β1 alone. Scale bar, 200 μm (C) or 400 μm (D).

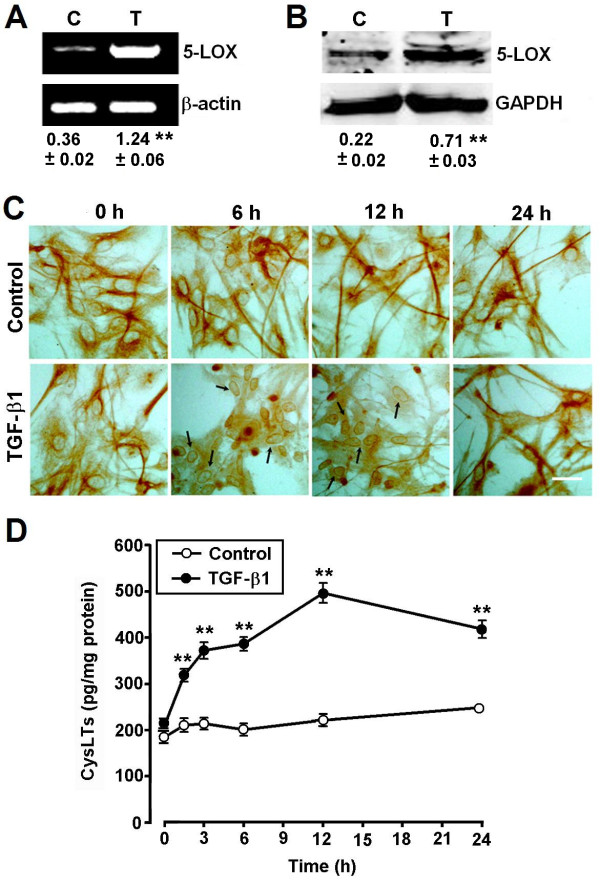

TGF-β1-Induced Activation of 5-LOX in astrocytes

To investigate the role of endogenous CysLTs, the 5-LOX metabolites, in TGF-β1-induced astrocyte migration, we determined 5-LOX expression in astrocytes. We found that TGF-β1 10 ng/ml significantly increased 5-LOX mRNA (Figure 7A) and protein expression (Figure 7B) 24 h after exposure. Immunocytochemical results showed that 5-LOX was translocated from the cytosol to the nuclear envelope 6 and 12 h after exposure to 10 ng/ml TGF-β1, and then recovered at 24 h (Figure 7C). We further determined the changes in enzymatic activity of 5-LOX by measuring its metabolites, CysLTs, in the culture medium. The levels of CysLTs increased from 1.5 h, peaked at 12 h, and were sustained over 24 h after exposure to 10 ng/ml TGF-β1 (Figure 7D). These findings revealed the involvement of 5-LOX and its metabolite CysLTs in the responses to TGF-β1.

Figure 7.

TGF-β1 induces 5-LOX expression and translocation, and increases the production of CysLTs in astrocytes. (A, B) RT-PCR and Western blotting results showing that 5-LOX mRNA (A) and protein expression (B) were increased in astrocytes after exposure to 10 ng/ml TGF-β1 for 24 h. Results are expressed as the ratios to β-actin (A) or GAPDH (B). C, control; T, TGF-β1. (C) Immunocytochemical examination reveals 5-LOX translocation to the nuclear envelope (arrows) in astrocytes after exposure to 10 ng/ml TGF-β1. Scale bar, 50 μm. (D) ELISA shows the production of CysLTs was significantly increased with a peak at 12 h after exposure to 10 ng/ml TGF-β1. Data are reported as mean ± S.E.M.; n = 4 (A and B) 8 (D); **P <0.01 compared with control.

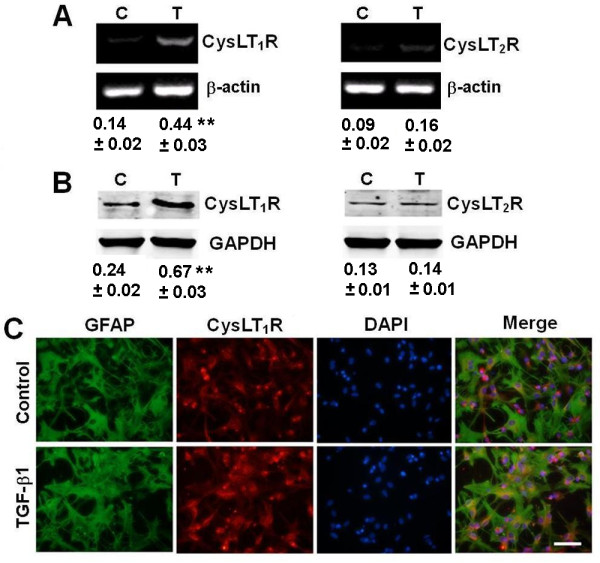

TGF-β1-regulated expression of CysLT receptor in astrocytes

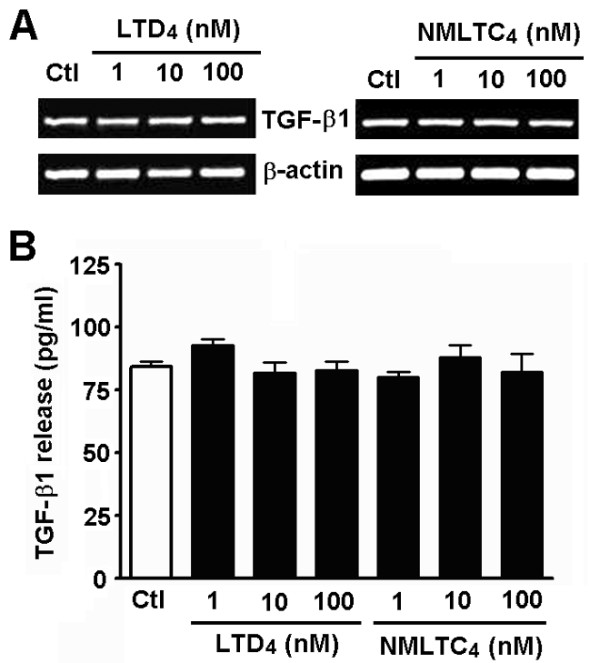

Finally, we determined whether TGF-β1 regulates the expression of CysLT1R and CysLT2R mRNA and protein in astrocytes, and whether LTD4 regulates TGF-β1 expression and release. RT-PCR and Western blot showed weak expression of CysLT1R and CysLT2R in control astrocytes. Exposure to 10 ng/ml TGF-β1 for 24 h induced about three-fold increase in the mRNA (Figure 8A) and protein expression (Figure 8B) of CysLT1R, but did not significantly change the expression of CysLT2R. Immunofluorescence staining confirmed the enhancement of CysLT1R by TGF-β1 (Figure 8C). On the other hand, treatment with various concentrations of LTD4 or NMLTC4 for 24 h did not affect the TGF-β1 mRNA expression in astrocytes (Figure 9A) and its content in the culture medium (Figure 9B). Thus, TGF-β1 might up-regulate CysLT1R but is not regulated by LTD4.

Figure 8.

Effect of TGF-β1 on expression of CysLT receptors in astrocytes. (A, B) RT-PCR and Western blotting results showing that the mRNA (A) and protein expression (B) of CysLT1R, but not CysLT2R, in astrocytes increased after exposure to 10 ng/ml TGF-β1 for 24 h. Data are reported as mean ± S.E.M.; n = 4; **P <0.01 compared with control. Results are expressed as the ratios to β-actin (A) or GAPDH (B). C, control; T, TGF-β1. (C) Double immunofluorescence staining showing that TGF-β1 increased the expression of CysLT1R in GFAP-positive astrocytes. Scale bar, 100 μm.

Figure 9.

Effects of LTD4and NMLTC4on TGF-β1 mRNA expression and TGF-β1 release in astrocytes. (A), RT-PCR analysis showing mRNA expression of TGF-β1 after treatment with 1, 10 and 100 nM LTD4 or NMLTC4 for 24 h. There was no significant difference in TGF-β1 expression after treatment with LTD4 and NMLTC4 (n = 4 for each group, P >0.05). (B) TGF-β1 release in the culture supernatants after exposure to LTD4 and NMLTC4 measured by ELISA. Neither LTD4 nor NMLTC4 affected TGF-β1 expression and release. Data are reported as mean ± S.E.M.; n = 6.

Discussion

In the present study, we revealed that TGF-β1-induced astrocyte migration is, at least in part, mediated by enhanced endogenous CysLTs through activation of CysLT1R. The evidence is that TGF-β1-induced astrocyte migration was potentiated by LTD4 but attenuated by a 5-LOX inhibitor and a CysLT1R antagonist, and TGF-β1 activated 5-LOX and increased CysLT1R expression. Our observations have confirmed the TGF-β1-induced migration of rat astrocytes as reported [6], and indicated another mechanism underlying TGF-β1-induced astrocyte migration in addition to the pathways through activation of the Smad family [47,48] or the ROS-dependent ERK/JNK-NF-κB pathway [6]. In addition, we found that both TGF-β1 and LTD4 did not alter astrocyte proliferation during 24 h. It has been reported that TGF-β1 inhibits astrocyte proliferation [47,49,50] and LTD4 induces the proliferation via activating CysLT1R [30]. This difference between these reported results and ours may result from different assessment timing [30] and methods [47,49,50]. However, in our experimental conditions, TGF-β1 and LTD4 regulate astrocyte migration rather than proliferation.

TGF-β1-induced astrocyte migration might be mediated by the CysLT signal pathway in at least two ways, that is, TGF-β1 potentiates the activity of both 5-LOX and CysLT1R. On one hand, TGF-β1 increased 5-LOX expression and induced its translocation to the nuclear envelope (Figure 7C), a key step for 5-LOX activation [51-53] and, thereby, increased the production of endogenous CysLTs (Figure 7D). Consistent with this, it has been reported that TGF-β1 induces 5-LOX expression in myeloid cell lines [54-58]. The notion is also supported by the finding that the TGF-β1 effect was inhibited by the 5-LOX inhibitor zileuton (Figure 5A). On the other hand, TGF-β1 potentiates the expression of CysLT1R, enhancing the activity of endogenously-produced or exogenous CysLTs as previously reported [37,39]. Therefore, one of the mechanisms underlying TGF-β1-induced astrocyte migration may be activation of endogenous 5-LOX/CysLT1R signals.

Here, we demonstrated that the receptor subtype that mediated the TGF-β1 effect was CysLT1R. The evidence was from the different effects of agonists and antagonists, and the effect of RNA interference. The non-selective agonist LTD4 induced a moderate migration of astrocytes at lower concentrations (0.1 to 10 nM), but not at the higher concentrations 100 nM (Figure 2A, C) and 1,000 nM (data not shown). This concentration-response relationship indicated that CysLT1R might mediate the effect of LTD4, because CysLT1R is activated at 1 to 10 nM while CysLT2R is activated at 100 to 1,000 nM in astrocytes [30]. This is also supported by the finding that the selective CysLT2R agonist NMLTC4[46] had no effect on astrocyte migration (Figure 3). With regard to receptor antagonism, the effect of TGF-β1 was attenuated by the CysLT1R antagonist montelukast but not by the CysLT2R antagonist Bay cysLT2. Bay cysLT2 is at least 100- to 500-fold more selective for CysLT2R versus CysLT1R; its pA2 value indicates that at least 5 μM would act on the CysLT1R [59,60]. Thus, lacking the effect of 5 μM Bay ctsLT2 in our study may be due to cell specificity and response difference. On the other hand, interference with CysLT1R siRNA inhibited both TGF-β1- and LTD4-induced astrocyte migration by down-regulating the expression of this receptor (Figure 6). These findings are consistent with reports that CysLT1R mediates the migration of other types of cells [31-36]. Therefore, CysLT1R is an important regulator of astrocyte migration in addition to its regulation of astrocyte proliferation [29,30].

The interaction between TGF-β1 and CysLTs was also investigated by determining the action of LTD4 or NMLTC4 on TGF-β1 expression and release. Unlike the action of TGF-β1 on the production of CysLTs and LTD4 effects, LTD4 or NMLTC4 affected neither TGF-β1 expression nor its release in astrocytes (Figure 9). This may depend on specific cell types because LTD4 induces TGF-β1 mRNA expression in human bronchial epithelial cells [61,62] and in fibroblasts from asthmatics [63], and LTC4 induces TGF-β1 production in airway epithelium [62] in a CysLT1R-dependent manner. Anyway, the effect of LTD4 on TGF-β1 in astrocytes remains to be further investigated, especially in animal models of chronic brain injury. Since both levels of TGF-β1 and CysLTs are increased after brain injury [24,64,65] and involved in glial scar formation [25,65,66]; which of them is determinant in glial scar formation should be clarified for their therapeutic implications. Herein, our results suggest that activation of the endogenous 5-LOX/CysLT1R signals might be an intermediate event in TGF-β1-regulated astrocyte migration, but not the initial event. Since TGF-β1 signaling is mainly modulated by Smad-dependent [67-75] and Smad-independent pathways [6,76-81], whether the regulation mode is mediated by the Smad or other pathways requires investigation.

Astrocyte migration is a critical step in the formation of a densely-packed glial scar [1,2], and TGF-β1 is closely associated with glial scar formation [64,66,82-84]. Thus, CysLT receptor antagonists or 5-LOX inhibitors may be beneficial in the prevention and attenuation of glial scar formation after brain injury. Actually, we have reported that the CysLT1R antagonist pranlukast attenuates glial scar formation in the chronic phase of focal cerebral ischemia in mice [28] and rats [25], and the 5-LOX inhibitor caffeic acid has this effect in rats with focal cerebral ischemia [85] and in mice with brain cryoinjury [86]. Moreover, montelukast inhibits the astrocyte proliferation induced by mild ischemia-like injury and low concentrations of LTD4[30]. The present study highlights the previous findings and clarifies the mode of action of endogenous CysLTs/CysLT1R in the critical step of glial scar formation.

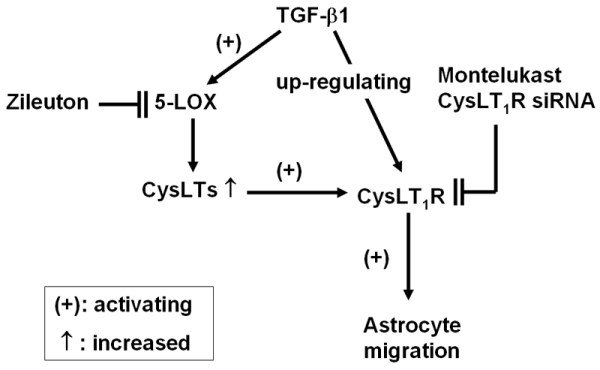

In conclusion, in the present study we found that TGF-β1-induced astrocyte migration is, at least in part, mediated by enhanced endogenous CysLTs through activating up-regulated CysLT1R (Figure 10). These findings indicate that the interaction between the cytokine TGF-β1 and pro-inflammatory mediators (CysLTs) are involved in the regulation of astrocyte function relevant to glial scar formation. However, the detailed mechanisms underlying this interaction need investigation.

Figure 10.

Diagram showing the roles of TGF-β1 and 5-LOX/CysLT1R in induction of astrocyte migration. TGF-β1 activates 5-LOX to produce CysLTs; the latter activates CysLT1R. Meanwhile, it also up-regulates CysLT1R expression, which enhances the activity of CysLT1R. The activated CysLT1R mediates TGF-β1-induced astrocyte migration.

Abbreviations

5-LOX, 5-lipoxygenase; CNS, central nervous system; CysLT1R, cysteinyl leukotriene receptor 1; CysLT2R, cysteinyl leukotriene receptor 2; CysLTs, Cysteinyl leukotrienes; FBS, fetal bovine serum; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase; GFAP, glial fibrillary acidic protein; LTD4, leukotriene D4; MFI, mean fluorescence intensity; NMLTC4, N-methyl leukotriene C4; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; siRNA, small interfering RNA; TGF-β1, transforming growth factor- β1.

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

XQH designed the study, performed the main parts of the experiments, analyzed the data, and prepared the manuscript. XYZ performed the immunofluorescence staining experiments and prepared the figures. XRW performed the cell migration experiments and analyzed the data. SYY performed the RT-PCR experiments and analyzed the data. SHF, YBL and WPZ contributed to the design of the study, to interpretation of the results and to the writing of the manuscript. EQW made essential contributions to the design of the study and interpretation of the results, and completed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Xue-Qin Huang, Email: huangxueqin2008@163.com.

Xia-Yan Zhang, Email: zhangxiayan1987@126.com.

Xiao-Rong Wang, Email: 407844982@qq.com.

Shu-Ying Yu, Email: shuying.101@163.com.

San-Hua Fang, Email: fangsanhua@gmail.com.

Yun-Bi Lu, Email: yunbi@zju.edu.cn.

Wei-Ping Zhang, Email: weiping601@zju.edu.cn.

Er-Qing Wei, Email: weieq2006@zju.edu.cn.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. T. Jon Seiders, Amira Pharmaceuticals Inc., USA, for supplying BAY cysLT2; Dr. John Obenhain, Merck Research Laboratories, USA, for montelukast; and Dr. IC Bruce for critically reading and revising this manuscript. This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81072618, 81173041, 30772561 and 30873053), the Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation (Y2090069), the Zhejiang Provincial “QianJiangRenCai Research Plan” (2010R10055), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2009QNA7008).

References

- Fawcett JW, Asher RA. The glial scar and central nervous system repair. Brain Res Bull. 1999;49:377–391. doi: 10.1016/S0361-9230(99)00072-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saadoun S, Papadopoulos MC, Watanabe H, Yan D, Manley GT, Verkman AS. Involvement of aquaporin-4 in astroglial cell migration and glial scar formation. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:5691–5698. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faber-Elman A, Lavie V, Schvartz I, Shaltiel S, Schwartz M. Vitronectin overrides a negative effect of TNF-alpha on astrocyte migration. FASEB J. 1995;9:1605–1613. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.9.15.8529840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Striedinger K, Scemes E. Interleukin-1beta affects calcium signaling and in vitro cell migration of astrocyte progenitors. J Neuroimmunol. 2008;196:116–123. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2008.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao H, Crabb AW, Hernandez MR, Lukas TJ. Modulation of factors affecting optic nerve head astrocyte migration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51:4096–4103. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-5177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh HL, Wang HH, Wu WB, Chu PJ, Yang CM. Transforming growth factor-beta1 induces matrix metalloproteinase-9 and cell migration in astrocytes: roles of ROS-dependent ERK- and JNK-NF-kappaB pathways. J Neuroinflammation. 2010;7:88. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-7-88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flanders KC, Ren RF, Lippa CF. Transforming growth factor-betas in neurodegenerative disease. Prog Neurobiol. 1998;54:71–85. doi: 10.1016/S0301-0082(97)00066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unsicker K, Strelau J. Functions of transforming growth factor-beta isoforms in the nervous system. Cues based on localization and experimental in vitro and in vivo evidence. Eur J Biochem. 2000;267:6972–6975. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01824.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bottner M, Krieglstein K, Unsicker K. The transforming growth factor-betas: structure, signaling, and roles in nervous system development and functions. J Neurochem. 2000;75:2227–2240. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0752227.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massague J. How cells read TGF-beta signals. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2000;1:169–178. doi: 10.1038/35043051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vivien D, Ali C. Transforming growth factor-beta signalling in brain disorders. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2006;17:121–128. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2005.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leivonen SK, Kahari VM. Transforming growth factor-beta signaling in cancer invasion and metastasis. Int J Cancer. 2007;121:2119–2124. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt BM, McPherson JM. TGF-beta in the central nervous system: potential roles in ischemic injury and neurodegenerative diseases. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 1997;8:267–292. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6101(97)00018-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehrmann E, Kiefer R, Christensen T, Toyka KV, Zimmer J, Diemer NH, Hartung HP, Finsen B. Microglia and macrophages are major sources of locally produced transforming growth factor-beta1 after transient middle cerebral artery occlusion in rats. Glia. 1998;24:437–448. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1136(199812)24:4<437::AID-GLIA9>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruocco A, Nicole O, Docagne F, Ali C, Chazalviel L, Komesli S, Yablonsky F, Roussel S, MacKenzie ET, Vivien D, Buisson A. A transforming growth factor-beta antagonist unmasks the neuroprotective role of this endogenous cytokine in excitotoxic and ischemic brain injury. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1999;19:1345–1353. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199912000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuelsson B, Dahlen SE, Lindgren JA, Rouzer CA, Serhan CN. Leukotrienes and lipoxins: structures, biosynthesis, and biological effects. Science. 1987;237:1171–1176. doi: 10.1126/science.2820055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanaoka Y, Boyce JA. Cysteinyl leukotrienes and their receptors: cellular distribution and function in immune and inflammatory responses. J Immunol. 2004;173:1503–1510. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.3.1503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenzel SE. The role of leukotrienes in asthma. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2003;69:145–155. doi: 10.1016/S0952-3278(03)00075-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vannella KM, McMillan TR, Charbeneau RP, Wilke CA, Thomas PE, Toews GB, Peters-Golden M, Moore BB. Cysteinyl leukotrienes are autocrine and paracrine regulators of fibrocyte function. J Immunol. 2007;179:7883–7890. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.11.7883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brink C, Dahlen SE, Drazen J, Evans JF, Hay DW, Nicosia S, Serhan CN, Shimizu T, Yokomizo T. International union of pharmacology XXXVII. Nomenclature for leukotriene and lipoxin receptors. Pharmacol Rev. 2003;55:195–227. doi: 10.1124/pr.55.1.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rovati GE, Capra V. Cysteinyl-leukotriene receptors and cellular signals. Scientific World Journal. 2007;7:1375–1392. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2007.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang SH, Zhou Y, Chu LS, Zhang WP, Wang ML, Yu GL, Peng F, Wei EQ. Spatio-temporal expression of cysteinyl leukotriene receptor-2 mRNA in rat brain after focal cerebral ischemia. Neurosci Lett. 2007;412:78–83. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2006.10.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang YJ, Zhang L, Ye YL, Fang SH, Zhou Y, Zhang WP, Lu YB, Wei EQ. Cysteinyl leukotriene receptors CysLT1 and CysLT2 are upregulated in acute neuronal injury after focal cerebral ischemia in mice. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2006;27:1553–1560. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2006.00458.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y, Wei EQ, Fang SH, Chu LS, Wang ML, Zhang WP, Yu GL, Ye YL, Lin SC, Chen Z. Spatio-temporal properties of 5-lipoxygenase expression and activation in the brain after focal cerebral ischemia in rats. Life Sci. 2006;79:1645–1656. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2006.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang SH, Wei EQ, Zhou Y, Wang ML, Zhang WP, Yu GL, Chu LS, Chen Z. Increased expression of cysteinyl leukotriene receptor-1 in the brain mediates neuronal damage and astrogliosis after focal cerebral ischemia in rats. Neuroscience. 2006;140:969–979. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.02.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao CZ, Zhao B, Zhang XY, Huang XQ, Shi WZ, Liu HL, Fang SH, Lu YB, Zhang WP, Tang FD, Wei EQ. Cysteinyl leukotriene receptor 2 is spatiotemporally involved in neuron injury, astrocytosis and microgliosis after focal cerebral ischemia in rats. Neuroscience. 2011;189:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.05.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu GL, Wei EQ, Zhang SH, Xu HM, Chu LS, Zhang WP, Zhang Q, Chen Z, Mei RH, Zhao MH. Montelukast, a cysteinyl leukotriene receptor-1 antagonist, dose- and time-dependently protects against focal cerebral ischemia in mice. Pharmacology. 2005;73:31–40. doi: 10.1159/000081072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu GL, Wei EQ, Wang ML, Zhang WP, Zhang SH, Weng JQ, Chu LS, Fang SH, Zhou Y, Chen Z, Zhang Q, Zhang LH. Pranlukast, a cysteinyl leukotriene receptor-1 antagonist, protects against chronic ischemic brain injury and inhibits the glial scar formation in mice. Brain Res. 2005;1053:116–125. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.06.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciccarelli R, D’Alimonte I, Santavenere C, D’Auro M, Ballerini P, Nargi E, Buccella S, Nicosia S, Folco G, Caciagli F, Di Iorio P. Cysteinyl-leukotrienes are released from astrocytes and increase astrocyte proliferation and glial fibrillary acidic protein via cys-LT1 receptors and mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;20:1514–1524. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03613.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang XJ, Zhang WP, Li CT, Shi WZ, Fang SH, Lu YB, Chen Z, Wei EQ. Activation of CysLT receptors induces astrocyte proliferation and death after oxygen-glucose deprivation. Glia. 2008;56:27–37. doi: 10.1002/glia.20588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woszczek G, Chen LY, Nagineni S, Kern S, Barb J, Munson PJ, Logun C, Danner RL, Shelhamer JH. Leukotriene D(4) induces gene expression in human monocytes through cysteinyl leukotriene type I receptor. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121:215–221. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.09.013. e211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thivierge M, Stankova J, Rola-Pleszczynski M. Toll-like receptor agonists differentially regulate cysteinyl-leukotriene receptor 1 expression and function in human dendritic cells. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117:1155–1162. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.12.1342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thivierge M, Stankova J, Rola-Pleszczynski M. Cysteinyl-leukotriene receptor type 1 expression and function is down-regulated during monocyte-derived dendritic cell maturation with zymosan: involvement of IL-10 and prostaglandins. J Immunol. 2009;183:6778–6787. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaetsu Y, Yamamoto Y, Sugihara S, Matsuura T, Igawa G, Matsubara K, Igawa O, Shigemasa C, Hisatome I. Role of cysteinyl leukotrienes in the proliferation and the migration of murine vascular smooth muscle cells in vivo and in vitro. Cardiovasc Res. 2007;76:160–166. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2007.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paruchuri S, Broom O, Dib K, Sjolander A. The pro-inflammatory mediator leukotriene D4 induces phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and Rac-dependent migration of intestinal epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:13538–13544. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409811200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan YM, Fang SH, Qian XD, Liu LY, Xu LH, Shi WZ, Zhang LH, Lu YB, Zhang WP, Wei EQ. Leukotriene D4 stimulates the migration but not proliferation of endothelial cells mediated by the cysteinyl leukotriene cyslt(1) receptor via the extracellular signal-regulated kinase pathway. J Pharmacol Sci. 2009;109:285–292. doi: 10.1254/jphs.08321FP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espinosa K, Bosse Y, Stankova J, Rola-Pleszczynski M. CysLT1 receptor upregulation by TGF-beta and IL-13 is associated with bronchial smooth muscle cell proliferation in response to LTD4. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;111:1032–1040. doi: 10.1067/mai.2003.1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asakura T, Ishii Y, Chibana K, Fukuda T. Leukotriene D4 stimulates collagen production from myofibroblasts transformed by TGF-beta. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114:310–315. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paiva LA, Maya-Monteiro CM, Bandeira-Melo C, Silva PM, El-Cheikh MC, Teodoro AJ, Borojevic R, Perez SA, Bozza PT. Interplay of cysteinyl leukotrienes and TGF-beta in the activation of hepatic stellate cells from Schistosoma mansoni granulomas. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1801:1341–1348. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2010.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi LL, Fang SH, Shi WZ, Huang XQ, Zhang XY, Lu YB, Zhang WP, Wei EQ. CysLT2 receptor-mediated AQP4 up-regulation is involved in ischemic-like injury through activation of ERK and p38 MAPK in rat astrocytes. Life Sci. 2011;88:50–56. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2010.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deleyrolle LP, Harding A, Cato K, Siebzehnrubl FA, Rahman M, Azari H, Olson S, Gabrielli B, Osborne G, Vescovi A, Reynolds BA. Evidence for label-retaining tumour-initiating cells in human glioblastoma. Brain. 2011;134:1331–1343. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quah BJ, Parish CR. New and improved methods for measuring lymphocyte proliferation in vitro and in vivo using CFSE-like fluorescent dyes. J Immunol Methods. 2012;379:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2012.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogie JF, Stinissen P, Hellings N, Hendriks JJ. Myelin-phagocytosing macrophages modulate autoreactive T cell proliferation. J Neuroinflammation. 2011;8:85. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-8-85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo JY, Zhang Z, Yu SY, Zhao B, Zhao CZ, Wang XX, Fang SH, Zhang WP, Zhang LH, Wei EQ, Lu YB. Rotenone-induced changes of cysteinyl leukotriene receptor 1 expression in BV2 microglial cells. Zhejiang Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2011;40:131–138. doi: 10.3785/j.issn.1008-9292.2011.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang LP, Zhao CZ, Shi WZ, Qi LL, Lu YB, Zhang YM, Zhang LH, Fang SH, Bao JF, Shen JG, Wei EQ. Preparation and identification of polyclonal antibody against cysteinyl leukotriene receptor 2. Zhejiang Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2009;38:591–597. doi: 10.3785/j.issn.1008-9292.2009.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan D, Stocco R, Sawyer N, Nesheim ME, Abramovitz M, Funk CD. Differential signaling of cysteinyl leukotrienes and a novel cysteinyl leukotriene receptor 2 (CysLT) agonist, N-methyl-leukotriene C, in calcium reporter and beta arrestin assays. Mol Pharmacol. 2011;79:270–278. doi: 10.1124/mol.110.069054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stipursky J, Gomes FC. TGF-beta1/SMAD signaling induces astrocyte fate commitment in vitro: implications for radial glia development. Glia. 2007;55:1023–1033. doi: 10.1002/glia.20522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schachtrup C, Ryu JK, Helmrick MJ, Vagena E, Galanakis DK, Degen JL, Margolis RU, Akassoglou K. Fibrinogen triggers astrocyte scar formation by promoting the availability of active TGF-beta after vascular damage. J Neurosci. 2010;30:5843–5854. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0137-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindholm D, Castren E, Kiefer R, Zafra F, Thoenen H. Transforming growth factor-beta 1 in the rat brain: increase after injury and inhibition of astrocyte proliferation. J Cell Biol. 1992;117:395–400. doi: 10.1083/jcb.117.2.395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klaver CL, Caplan MR. Bioactive surface for neural electrodes: decreasing astrocyte proliferation via transforming growth factor-beta1. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2007;81:1011–1016. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge QF, Wei EQ, Zhang WP, Hu X, Huang XJ, Zhang L, Song Y, Ma ZQ, Chen Z, Luo JH. Activation of 5-lipoxygenase after oxygen-glucose deprivation is partly mediated via NMDA receptor in rat cortical neurons. J Neurochem. 2006;97:992–1004. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03828.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li CT, Zhang WP, Lu YB, Fang SH, Yuan YM, Qi LL, Zhang LH, Huang XJ, Zhang L, Chen Z, Wei EQ. Oxygen-glucose deprivation activates 5-lipoxygenase mediated by oxidative stress through the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway in PC12 cells. J Neurosci Res. 2009;87:991–1001. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Y, Wei EQ, Zhang WP, Ge QF, Liu JR, Wang ML, Huang XJ, Hu X, Chen Z. Minocycline protects PC12 cells against NMDA-induced injury via inhibiting 5-lipoxygenase activation. Brain Res. 2006;1085:57–67. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.02.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinhilber D, Radmark O, Samuelsson B. Transforming growth factor beta upregulates 5-lipoxygenase activity during myeloid cell maturation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:5984–5988. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.13.5984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brungs M, Radmark O, Samuelsson B, Steinhilber D. On the induction of 5-lipoxygenase expression and activity in HL-60 cells: effects of vitamin D3, retinoic acid, DMSO and TGF beta. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;205:1572–1580. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.2846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brungs M, Radmark O, Samuelsson B, Steinhilber D. Sequential induction of 5-lipoxygenase gene expression and activity in Mono Mac 6 cells by transforming growth factor beta and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:107–111. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.1.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harle D, Radmark O, Samuelsson B, Steinhilber D. Calcitriol and transforming growth factor-beta upregulate 5-lipoxygenase mRNA expression by increasing gene transcription and mRNA maturation. Eur J Biochem. 1998;254:275–281. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1998.2540275.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seuter S, Sorg BL, Steinhilber D. The coding sequence mediates induction of 5-lipoxygenase expression by Smads3/4. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;348:1403–1410. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni NC, Yan D, Ballantyne LL, Barajas-Espinosa A, St Amand T, Pratt DA, Funk CD. A selective cysteinyl leukotriene receptor 2 antagonist blocks myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury and vascular permeability in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2011;339:768–778. doi: 10.1124/jpet.111.186031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carnini C, Accomazzo MR, Borroni E, Vitellaro-Zuccarello L, Durand T, Folco G, Rovati GE, Capra V, Sala A. Synthesis of cysteinyl leukotrienes in human endothelial cells: subcellular localization and autocrine signaling through the CysLT2 receptor. FASEB J. 2011;25:3519–3528. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-177030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosse Y, Thompson C, McMahon S, Dubois CM, Stankova J, Rola-Pleszczynski M. Leukotriene D4-induced, epithelial cell-derived transforming growth factor beta1 in human bronchial smooth muscle cell proliferation. Clin Exp Allergy. 2008;38:113–121. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2007.02873.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perng DW, Wu YC, Chang KT, Wu MT, Chiou YC, Su KC, Perng RP, Lee YC. Leukotriene C4 induces TGF-beta1 production in airway epithelium via p38 kinase pathway. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2006;34:101–107. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2005-0068OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eap R, Jacques E, Semlali A, Plante S, Chakir J. Cysteinyl leukotrienes regulate TGF-beta(1) and collagen production by bronchial fibroblasts obtained from asthmatic subjects. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2012;86:127–133. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2011.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita K, Gerken U, Vogel P, Hossmann K, Wiessner C. Biphasic expression of TGF-beta1 mRNA in the rat brain following permanent occlusion of the middle cerebral artery. Brain Res. 1999;836:139–145. doi: 10.1016/S0006-8993(99)01626-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle KP, Cekanaviciute E, Mamer LE, Buckwalter MS. TGFbeta signaling in the brain increases with aging and signals to astrocytes and innate immune cells in the weeks after stroke. J Neuroinflammation. 2010;7:62. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-7-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohta M, Kohmura E, Yamashita T. Inhibition of TGF-beta1 promotes functional recovery after spinal cord injury. Neurosci Res. 2009;65:393–401. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2009.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massague J, Wotton D. Transcriptional control by the TGF-beta/Smad signaling system. EMBO J. 2000;19:1745–1754. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.8.1745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kloos DU, Choi C, Wingender E. The TGF-beta–Smad network: introducing bioinformatic tools. Trends Genet. 2002;18:96–103. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9525(02)02556-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Yang GH, Bu H, Zhou Q, Guo LX, Wang SL, Ye L. Systematic analysis of the TGF-beta/Smad signalling pathway in the rhabdomyosarcoma cell line RD. Int J Exp Pathol. 2003;84:153–163. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2613.2003.00347.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ten Dijke P, Hill CS. New insights into TGF-beta-Smad signalling. Trends Biochem Sci. 2004;29:265–273. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2004.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy L, Hill CS. Smad4 dependency defines two classes of transforming growth factor beta (TGF-{beta}) target genes and distinguishes TGF-{beta}-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition from its antiproliferative and migratory responses. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:8108–8125. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.18.8108-8125.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaminska B, Wesolowska A, Danilkiewicz M. TGF beta signalling and its role in tumour pathogenesis. Acta Biochim Pol. 2005;52:329–337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finnson KW, Parker WL, Chi Y, Hoemann CD, Goldring MB, Antoniou J, Philip A. Endoglin differentially regulates TGF-beta-induced Smad2/3 and Smad1/5 signalling and its expression correlates with extracellular matrix production and cellular differentiation state in human chondrocytes. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2010;18:1518–1527. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2010.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M, Lv Z, Jiang S. The effects of triptolide on airway remodelling and transforming growth factor-beta/Smad signalling pathway in ovalbumin-sensitized mice. Immunology. 2011;132:376–384. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2010.03392.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lampropoulos P, Zizi-Sermpetzoglou A, Rizos S, Kostakis A, Nikiteas N, Papavassiliou AG. TGF-beta signalling in colon carcinogenesis. Cancer Lett. 2012;314:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2011.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park BJ, Park JI, Byun DS, Park JH, Chi SG. Mitogenic conversion of transforming growth factor-beta1 effect by oncogenic Ha-Ras-induced activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway in human prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2000;60:3031–3038. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai C, Yang J, Liu Y. Transforming growth factor-beta1 potentiates renal tubular epithelial cell death by a mechanism independent of Smad signaling. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:12537–12545. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300777200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YK. TGF-beta1 induction of p21WAF1/cip1 requires Smad-independent protein kinase C signaling pathway. Arch Pharm Res. 2007;30:739–742. doi: 10.1007/BF02977636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niculescu-Duvaz I, Phanish MK, Colville-Nash P, Dockrell ME. The TGFbeta1-induced fibronectin in human renal proximal tubular epithelial cells is p38 MAP kinase dependent and Smad independent. Nephron Exp Nephrol. 2007;105:e108–e116. doi: 10.1159/000100492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane NM, Jones M, Brosens JJ, Kelly RW, Saunders PT, Critchley HO. TGFbeta1 attenuates expression of prolactin and IGFBP-1 in decidualized endometrial stromal cells by both SMAD-dependent and SMAD-independent pathways. PLoS One. 2010;5:e12970. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins SJ, Borthwick GM, Oakenfull R, Robson A, Arthur HM. Angiotensin II-induced cardiomyocyte hypertrophy in vitro is TAK1-dependent and Smad2/3-independent. Hypertens Res. 2012;35:393–398. doi: 10.1038/hr.2011.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes FC, Sousa Vde O, Romao L. Emerging roles for TGF-beta1 in nervous system development. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2005;23:413–424. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2005.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss A, Pech K, Kakulas BA, Martin D, Schoenen J, Noth J, Brook GA. TGF-beta1 and TGF-beta2 expression after traumatic human spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2008;46:364–371. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3102148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komuta Y, Teng X, Yanagisawa H, Sango K, Kawamura K, Kawano H. Expression of transforming growth factor-beta receptors in meningeal fibroblasts of the injured mouse brain. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2010;30:101–111. doi: 10.1007/s10571-009-9435-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y, Fang SH, Ye YL, Chu LS, Zhang WP, Wang ML, Wei EQ. Caffeic acid ameliorates early and delayed brain injuries after focal cerebral ischemia in rats. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2006;27:1103–1110. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2006.00406.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Zhang WP, Chen KD, Qian XD, Fang SH, Wei EQ. Caffeic acid attenuates neuronal damage, astrogliosis and glial scar formation in mouse brain with cryoinjury. Life Sci. 2007;80:530–537. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2006.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]