Abstract

Systemic acquired resistance (SAR) is a broad-spectrum resistance mechanism in plants that is activated in naive organs after exposure of another organ to a necrotizing pathogen. The organs manifesting SAR exhibit an increase in levels of salicylic acid (SA) and expression of the PATHOGENESIS-RELATED1 (PR1) gene. SA signaling is required for the manifestation of SAR. We demonstrate here that the Arabidopsis thaliana suppressor of fatty acid desaturase deficiency1 (sfd1) mutation compromises the SAR-conferred enhanced resistance to Pseudomonas syringae pv maculicola. In addition, the sfd1 mutation diminished the SAR-associated accumulation of elevated levels of SA and PR1 gene transcript in the distal leaves of plants previously exposed to an avirulent pathogen. However, the basal resistance to virulent and avirulent strains of P. syringae and the accumulation of elevated levels of SA and PR1 gene transcript in the pathogen-inoculated leaves of sfd1 were not compromised. Furthermore, the application of the SA functional analog benzothiadiazole enhanced disease resistance in the sfd1 mutant plants. SFD1 encodes a putative dihydroxyacetone phosphate (DHAP) reductase, which complemented the glycerol-3-phosphate auxotrophy of the DHAP reductase–deficient Escherichia coli gpsA mutant. Plastid glycerolipid composition was altered in the sfd1 mutant plant, suggesting that SFD1 is involved in lipid metabolism and that an SFD1 product lipid(s) is important for the activation of SAR.

INTRODUCTION

Plants have evolved constitutive and inducible defense mechanisms to counter pathogens. In many cases, initial recognition of the pathogen occurs via the products of a specific plant resistance gene and a corresponding pathogen avirulence (avr) gene (Scofield et al., 1996; Tang et al., 1996; De Wit, 1998). Recognition of the pathogen leads to the coordinated activation of a plethora of plant defense responses. In many cases, a hypersensitive response (HR), characterized by a localized programmed host cell death and tissue collapse, is observed (Goodman and Novacky, 1994; Hammond-Kosack and Jones, 1996). Subsequently, systemic acquired resistance (SAR) is activated in the naive distal organs of these plants (Hunt and Ryals, 1996; Ryals et al., 1996; Hammerschmidt, 1999; Van Loon, 2000). SAR confers broad-spectrum resistance to pathogens. An unknown signal(s) produced in the pathogen-challenged tissue traverses to the distal naive organs, where it activates SAR (Ross, 1966). The SAR-conferred enhanced resistance is accompanied by the elevated level of expression of a subgroup of the PATHOGENESIS-RELATED (PR) genes, which encode proteins with antimicrobial activities (Klessig and Malamy, 1994; Hunt and Ryals, 1996; Kombrink and Somssich, 1997). The expression of these PR genes has served as a good molecular marker to follow the activation of SAR. There is an increase in the content of salicylic acid (SA) in the pathogen-inoculated tissues and the distal organs that manifest SAR (Malamy et al., 1990; Métraux et al., 1990; Rasmussen et al., 1991). The increase in SA content in the distal organs is essential for the activation of SAR (Vernooij et al., 1994). The Arabidopsis thaliana SA biosynthesis–deficient eds5/sid1 and eds16/sid2 mutants and the transgenic nahG plants that express the SA-degrading salicylate hydroxylase are unable to activate SAR (Delaney et al., 1994; Nawrath and Metraux, 1999). Moreover, the application of SA or its functional analog, benzothiadiazole (BTH), induces expression of the PR genes and a SAR-type response in the tissue to which it is applied (Hunt and Ryals, 1996; Lawton et al., 1996; Ryals et al., 1996). The A. thaliana NPR1/NIM1 gene is a key component of SA signaling in plant defense. The npr1/nim1 mutations block the activation of PR1 expression by applied SA and BTH and confer enhanced susceptibility to bacterial and oomycete pathogens (Cao et al., 1994; Delaney et al., 1995; Glazebrook et al., 1996; Shah et al., 1997). In addition to its requirement in basal resistance, NPR1 is needed for the activation of SAR (Cao et al., 1994; Delaney et al., 1995). SA signaling also occurs via NPR1-independent mechanism(s) in addition to the NPR1-dependent pathway (Shah et al., 1997, 1999; Clarke et al., 2000; Nandi et al., 2003a).

The A. thaliana ssi2 (for suppressor of SA-insensitivity2) mutant and ssi2 npr1 double mutant plants contain high levels of SA, constitutively express the PR1 gene, and exhibit enhanced resistance to bacterial and oomycete pathogens (Shah et al., 2001). However, in comparison with the ssi2 single mutant plant, the ssi2-conferred accumulation of PR1 transcript is weaker in the ssi2 npr1 double mutant. Thus, both NPR1-dependent and -independent defense mechanisms are constitutively active in the ssi2 plant. The high SA level is partly required for the ssi2-conferred PR1 expression and enhanced disease resistance; ssi2-conferred PR1 expression and enhanced disease resistance is depressed in ssi2 nahG and ssi2 eds5 plants (Shah et al., 2001; A. Nandi and J. Shah, unpublished data). In addition to altering defense responses, the ssi2 and the allelic fab2 mutants are dwarf and develop lesions containing dead cells (Kachroo et al., 2001; Shah et al., 2001). The recessive sfd1-1 and sfd1-2 mutant alleles suppress the ssi2-conferred NPR1-independent expression of PR1 and the enhanced resistance to Pseudomonas syringae pv maculicola (Nandi et al., 2003b). In addition, sfd1 ssi2 npr1 plants don't manifest ssi2-conferred spontaneous cell death, high levels of SA accumulation, and dwarfing. The sfd1 mutant alleles also suppress the ssi2-conferred PR1 expression in NPR1-containing sfd1 ssi2 plants. Interestingly, SA and BTH application are not effective in restoring ssi2-conferred PR1 expression in the sfd1 ssi2 and sfd1 ssi2 npr1 plants (Nandi et al., 2003b). This suggests that in addition to SA, another factor is required for ssi2-conferred PR1 expression.

SSI2 encodes a plastid-localized stearoyl-acyl carrier protein desaturase (Kachroo et al., 2001). In comparison with the wild-type plant, fatty acid and complex lipid composition is altered in the ssi2 mutant (Kachroo et al., 2001; Nandi et al., 2003b), thus suggesting the involvement of a lipid(s) and/or lipid compositional dynamics in SA signaling. More support for the involvement of lipids in the ssi2-conferred NPR1-independent defense responses is provided by studies on the three different complementation groups of sfd mutants, which suppress the ssi2-conferred NPR1-independent PR1 expression and enhanced resistance to P. s. maculicola (Nandi et al., 2003b). A common physiological alteration observed in the sfd1 ssi2 npr1, sfd2 ssi2 npr1, and sfd4 ssi2 npr1 plants is the lowered level of lipids containing the fatty acid hexadecatrienoic acid (16:3), suggesting a role for 16:3-containing lipids in the ssi2-conferred SA-mediated NPR1-independent defense phenotypes. Moreover, the SFD4/FAD6 gene encodes a plastidic ω6-desaturase involved in the synthesis of 16:3 and 18:3 (Nandi et al., 2003b). A role for lipids in SA signaling also is supported by pharmacological studies in Nicotiana tabacum (tobacco) that suggest a role for lipid peroxidation in the SA-activated expression of PR1 (Anderson et al., 1998). Furthermore, SA activates expression of the A. thaliana αDOX1 gene, which encodes a 16- and 18-C fatty acid–oxidizing α-dioxygenase (De León et al., 2002). Suppression of αDOX1 expression confers enhanced susceptibility to P. syringae. Moreover, mutations in the EDS1 and PAD4 genes, which encode proteins with homology to the catalytic domain of eukaryotic lipases, impair SA-regulated defense responses in A. thaliana (Falk et al., 1999; Jirage et al., 1999). Studies of the SAR-deficient dir1-1 mutant have suggested a role for lipids in SAR as well. The DIR1 gene encodes a putative protein with homology to eukaryotic lipid transfer proteins (Maldonado et al., 2002).

In plants, the first step in glycerolipid synthesis is the trans-acylation of glycerol-3-phosphate (G3P) by acyl transferases to yield lysophosphatidic acid (Somerville et al., 2000; Wallis and Browse, 2002). Lysophosphatidic acid is further converted into other glycerolipids. G3P is synthesized from dihydroxyacetone phosphate (DHAP) by DHAP reductases in the plastids and cytoplasm and from glycerol by glycerol kinases located in the cytoplasm (Hippman and Heinz, 1976; Gee et al., 1988; Ghosh and Sastry, 1988; Kirsch et al., 1992). Two major pathways synthesize glycerolipids: the prokaryotic pathway, which is localized on the plastid inner envelope, and the eukaryotic pathway, which is localized on the endoplasmic reticulum (Somerville et al., 2000; Wallis and Browse, 2002). In A. thaliana, the prokaryotic pathway synthesizes the plastidic lipids phosphatidylglycerol (PG), monogalactosyldiacylglycerol (MGDG), digalactosyldiacylglycerol (DGDG), and sulfoquinovosyldiacylglycerol. By contrast, the eukaryotic pathway synthesizes phosphatidylcholine (PC), phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), phosphatidylinositol (PI), and phosphatidylserine. A fraction of the PC or PC-derived moieties are returned to the plastid, where an acyl-glycerol component is used to synthesize some species of the plastid-localized lipids MGDG, DGDG, and sulfoquinovosyldiacylglycerol, for example 36:6 (18:3-18:3 acyl combination)-MGDG and 36:6-DGDG (Browse et al., 1986; Mongrand et al., 2000). The relative positions and extent of desaturation of the 16- and 18-C acyl species esterified to glycerol, and the lipid head group classes formed in the two compartments are determined by the differences in enzymes present in the two compartments. For example, in A. thaliana, the desaturation of 16-C acyl chains occurs primarily on plastidic glycerolipids. Hence, 16:3 is predominantly found in the plastidic lipid 34:6 (18:3-16:3 acyl combination)-MGDG (Wallis and Browse, 2002).

Here, we show that recessive mutations in the SFD1 gene compromise the activation of SAR but not local defense responses. This inability of the sfd1 mutants to activate SAR is because of the lack of SAR-associated SA accumulation in the distal organs. However, unlike the eds5/sid1 and eds16/sid2 mutants, sfd1 is not defective in SA biosynthesis per se; SA accumulated to high levels in the pathogen-inoculated leaves of the sfd1 mutants. SFD1 encodes a DHAP reductase that is required for the synthesis of plastidic glycerolipids, suggesting the involvement of lipids and/or lipid compositional dynamics in the activation of SAR.

RESULTS

The sfd1 Single Mutant Alters Glycerolipid Composition

We have shown previously that in comparison with the wild-type plant, the total leaf lipid content in the ssi2 and ssi2 npr1 mutants was depressed (Nandi et al., 2003b). This decrease was attributable to a lower content of the plastid-synthesized PG, MGDG, and DGDG. The total leaf lipid content was partly restored in the sfd1 ssi2 npr1 triple mutant, primarily as a result of increase in the content of 36:6 (18:3-18:3 acyl combination)-MGDG. By contrast, in comparison with the ssi2 npr1 plant, the content of 34:6 (18:3-16:3 acyl combination)-MGDG, which is synthesized exclusively in the plastids, was 17% lower in the sfd1 ssi2 npr1 plant. In addition, in comparison with the ssi2 npr1 plant, levels of the 34:3-containing extraplastidic phospholipids, PC, PE, and PI also were depressed in the sfd1 ssi2 npr1 plant. These results suggest the involvement of SFD1 in lipid metabolism. However, some of these alterations in the sfd1 ssi2 npr1 plants could be secondary changes resulting from suppression of the ssi2-conferred phenotypes by the sfd1 mutant alleles. To determine the role of SFD1 in lipid metabolism, we generated sfd1-1 and sfd1-2 single mutant plants. Electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry (ESI-MS/MS) was used to compare the molecular species of glycerolipids in leaves of the sfd1-2 and wild-type plants. No significant changes were observed in the molecular composition of the nonplastidic glycerolipids PC, PE, and PI between wild-type and sfd1-2 leaves (see Figure 1 in supplemental data online). However, changes in the molecular composition of plastid-localized lipids were observed between the wild type and sfd1-2 (Figure 1). In A. thaliana, MGDG is the most abundant glycerolipid class and is found primarily in the plastids (Somerville et al., 2000; Wallis and Browse, 2002). The two major MGDG species in A. thaliana are 34:6 (18:3-16:3) and 36:6 (18:3-18:3). In comparison with the level of 34:6-MGDG in the wild-type plant, the level of 34:6 MGDG in sfd1-2 was 45% lower. By contrast, the content of 36:6-MGDG doubled, and the levels of 36:6-DGDG increased by 20% in sfd1-2 leaves.

Figure 1.

Major Plastidic Glycerolipids in Leaves of Wild-Type and sfd1-2 Mutant Plants.

Individual glycerolipids are characterized by their head groups, MGDG, DGDG, and PG, and the total number of acyl carbons and double bonds. Lipid concentrations are expressed as nanomoles of lipids per milligram of dry weight of leaf tissue. All values are the mean of five samples ± sd. See Figure 1 in the supplemental data online for a comparison of the composition of nonplastidic glycerolipids in wild-type and sfd1-2 mutant plants.

SAR-Coupled PR1 Expression Is Compromised in sfd1

The sfd1-1 and sfd1-2 mutant alleles suppress the ssi2-conferred PR1 expression and enhanced resistance to P. s. maculicola (Nandi et al., 2003b). To determine the role of SFD1 in plant defense, we compared PR1 expression in the pathogen-inoculated and distal leaves of the sfd1-1 mutant with the wild-type and npr1 mutant. As shown in Figure 2A, inoculation with avirulent (Avr) and virulent (Vir) strains of P. syringae strongly activated PR1 expression in the pathogen-inoculated leaf of sfd1. The extent of PR1 expression in the pathogen-inoculated leaf of sfd1 was only marginally weaker than that in the leaf of a similarly treated wild-type plant. By comparison, as shown previously (Shah et al., 1997), the expression of PR1 in the pathogen-inoculated leaf of the npr1 mutant was delayed and lower than that in the wild-type plant. PR1 transcript was undetectable in leaves of the wild-type, sfd1-1, and npr1 plants inoculated with 10 mM MgCl2 (Mock), which was used to dilute the pathogen culture.

Figure 2.

PR1 and SFD1 Gene Transcript Accumulation in Pathogen-Challenged and Distal Leaves of Wild-Type and Mutant Plants.

(A) PR1 gene transcript accumulation in pathogen-inoculated leaves. PR1 transcript accumulation was monitored at 0, 1, and 2 DAI in the pathogen-inoculated leaves of wild-type, sfd1-1, and npr1-5 (npr1) plants. Four fully expanded leaves of each plant were inoculated with a suspension containing 2 × 105 cfu/mL of the avirulent strain P. s. tomato DC3000 carrying avrRpt2 (Avr) or the virulent strain P. s. maculicola (Vir) in 10 mM MgCl2. As a control, in parallel, RNA also was extracted from leaves treated with 10 mM MgCl2 (Mock). The blots were hybridized with a radiolabeled PR1 probe.

(B) PR1 gene transcript accumulation accompanying the activation of SAR. PR1 transcript accumulation in the distal uninoculated leaves of wild-type, sfd1-1, and npr1 plants that had two other leaves previously inoculated either with a suspension containing 107 cfu/mL of P. s. tomato DC3000 carrying avrRpt2 (Avr) or 10 mM MgCl2 (Mock). RNA was extracted at 1, 2, and 3 DAI. The blot was hybridized with a radiolabeled PR1 probe.

(C) SFD1 gene transcript accumulation in leaves of the wild-type plant. SFD1 transcript accumulation was monitored in leaves infiltrated with 10 mM MgCl2 (Mock; Local) and in leaves inoculated with 2 × 105 cfu/mL of P. s. maculicola (Vir; Local) and P. s. tomato DC3000 carrying avrRpt2 (Avr; Local). SFD1 transcript accumulation also was monitored in the uninoculated leaves (Distal) of plants that had two other leaves infiltrated with 10 mM MgCl2 (Mock; Distal) or 2 × 105 cfu/mL of P. s. tomato DC3000 carrying avrRpt2 (Avr; Distal). Blots were hybridized with a radiolabeled SFD1 probe.

In (A), (B), and (C), gel loading was monitored by photographing the ethidium bromide (EtBr)–stained gel before transfer to the membrane.

In contrast with the pathogen-inoculated leaves, the SAR-coupled PR1 expression was undetectable in the distal uninoculated leaves of a sfd1-1 plant, which had two other leaves previously inoculated with an avirulent strain of P. syringae pv tomato (Figure 2B). Similar results were observed with the sfd1-2 mutant (data not shown). This resembles the pattern of PR1 expression observed in the distal uninoculated leaves of the npr1 mutant. By contrast, in the distal leaves of the control wild-type plant, the elevated expression of PR1 that accompanies SAR was observed at 2 and 3 d after inoculation (DAI) of two other leaves with the avirulent pathogen. As expected, PR1 expression was negligible in the distal leaves of wild-type, sfd1-1, and npr1 plants that had two other leaves previously infiltrated with 10 mM MgCl2 (Mock).

SAR, but Not Basal Resistance, Is Compromised in sfd1

Because PR1 expression that accompanies SAR is compromised in sfd1 mutants, we compared the SAR-conferred enhancement of resistance to the virulent pathogen P. s. maculicola in sfd1-1 and wild-type plants. The npr1 mutant served as the SAR-deficient control for this experiment. To activate SAR, two fully expanded leaves of each 4-week-old plant were infiltrated (1° inoculation) with a suspension containing P. s. tomato carrying the avirulence gene avrRpt2. In parallel, plants that were similarly infiltrated with 10 mM MgCl2 served as the controls. Two days later, four other leaves of each plant were challenged with a suspension containing P. s. maculicola. P. s. maculicola numbers were monitored on the day of challenge inoculation (0 DAI) and 3 DAI. As shown in Figure 3A, at 0 DAI, comparable numbers of bacteria were present in the distal leaves of wild-type, sfd1-1, and npr1 plants in which the 1° inoculation was either 10 mM MgCl2 (Mock) or the avirulent pathogen (Avr). At 3 DAI, the average count of P. s. maculicola had increased 5000-fold in the wild-type plant that received a 1° mock treatment. By contrast, only a 40-fold increase in P. s. maculicola number was observed at 3 DAI in the leaves of wild-type plants, in which SAR was activated by a prior exposure to the avirulent pathogen. As expected, the SAR-conferred enhanced resistance to P. s. maculicola was not observed in the npr1 mutant plant; comparable numbers of P. s. maculicola were present at 3 DAI in plants that received a 1° mock treatment or a 1° exposure to the avirulent pathogen. In comparison with the 1° mock-treated sfd1-1 plant, 1° inoculation with the avirulent pathogen conferred only a small reduction in P. s. maculicola number, indicating that SAR was compromised in the sfd1-1 mutant. Similarly, SAR was compromised in the sfd1-2 mutant (data not shown). The SAR deficiency in sfd1-1 is not caused by its insensitivity to the Rpt2 avirulence factor. The HR-associated tissue collapse was observed in leaves of the sfd1-1 plant that were inoculated with P. s. tomato containing the avirulence gene avrRpt2 (Figure 3C). The timing of the onset of HR was comparable between the wild-type and sfd1-1 mutants.

Figure 3.

Pathogen Growth and HR in Leaves of Wild-Type and Mutant Plants.

(A) Growth of the virulent pathogen P. s. maculicola with or without the prior induction of SAR. Two fully expanded leaves of wild-type, sfd1-1, and npr1-5 (npr1) plants either were injected with 10 mM MgCl2 (Mock) (open bar) or inoculated with a suspension containing 107 cfu/mL of P. s. tomato DC3000 carrying the avirulence gene avrRpt2 (Avr) (black bar). Two days later, four other leaves of each plant were challenge-inoculated with a suspension containing 2.5 × 105 cfu/mL of P. s. maculicola. P. s. maculicola numbers in leaves were monitored on the day of challenge inoculation (0 DAI) and 3 DAI. All values are the mean of five samples ±sd.

(B) Growth of the avirulent pathogen P. s. tomato DC3000 containing avrRpt2. Four fully expanded leaves of wild-type, sfd1-1, and npr1 plants were injected with a suspension containing 2 × 105 cfu/mL of P. s. tomato DC3000 carrying the avirulence gene avrRpt2. Bacterial growth in the pathogen-inoculated leaves was monitored at 0 and 3 DAI. All values are the mean of five samples ±sd.

(C) HR in leaves of the wild-type and sfd1-1 mutant. Fully expanded leaves of the wild-type and the sfd1-1 mutant were inoculated with a suspension containing 107 cfu/mL of P. s. tomato carrying the avirulence gene avrRpt2 (Pst avrRpt2). As a control, in parallel, leaves from the wild-type and sfd1-1 plants also were inoculated with the virulent strain P. s. tomato (Pst). The HR-associated tissue collapse was monitored over a period of 24 h. The photographs shown were taken at the same magnification, 16 h after inoculation with the pathogen.

In contrast with the SAR-conferred resistance, basal resistance to P. s. maculicola was not compromised in the sfd1-1 mutant. At 3 DAI, comparable numbers of P. s. maculicola were present in the leaves of the 1° mock-treated wild-type and sfd1-1 plants (Figure 3A). Similarly, as shown in Figure 3B, basal resistance to P. s. tomato carrying the avirulence gene avrRpt2 was comparable between the wild-type and sfd1-1 plants. By contrast, as previously shown (Shah et al., 1997, 1999, 2001), the npr1 mutant compromised basal resistance to this avirulent pathogen. Thus, although basal resistance is unimpaired, SAR is compromised in the sfd1 mutants.

Increase in SA Level That Accompanies SAR Is Compromised in sfd1

The increase in SA level that accompanies SAR is important for the SAR-conferred enhanced resistance. Previously, we have shown that the ssi2-conferred accumulation of elevated SA levels was suppressed in the sfd1-1 ssi2 npr1 plant (Nandi et al., 2003b). A lack of SA accumulation may account for the SAR deficiency of sfd1-1. Therefore, we measured the levels of SA plus its glucoside, SAG, in the distal leaves of the sfd1-1 mutant plant, 2 DAI of two other leaves with P. s. tomato carrying the avrRpt2 gene. The similarly treated wild-type plant served as the control. SA levels in the leaves of untreated wild-type and sfd1-1 plants provided a measure of the basal SA levels. As shown in Figure 4, the total SA content in the distal leaves of a wild-type plant that had two other leaves previously inoculated with the avirulent pathogen were 2.5-fold higher than the total SA content in the leaves of the control wild-type plant. By contrast, no increase in the total SA content was observed in the distal leaves of the sfd1-1 plant. However, sfd1-1 is not deficient in SA synthesis per se; like the wild type, the total SA content increased >25-fold in the pathogen-inoculated leaves of the sfd1-1 mutant (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Total SA Content in the Leaves of Pathogen-Inoculated Wild-Type and sfd1-1 Mutant Plants.

Total SA (SA + SAG) accumulation in the wild-type (gray bars) and sfd1-1 (black bars) plants. Leaf samples were taken from untreated plants (Control) and from the pathogen-inoculated (Local) and uninoculated leaves (Distal) of a plant inoculated 2 d earlier with a suspension containing 107 cfu/mL of P. s. tomato DC3000 carrying the avirulence gene avrRpt2. The total SA concentration is expressed as micrograms of total SA per gram of fresh weight of leaf tissue. All values are the mean of five samples ±sd. The difference between any two bars with different letters at the top is statistically significant (>95% confidence), whereas bars with the same letter indicates that the difference between the two values is statistically insignificant.

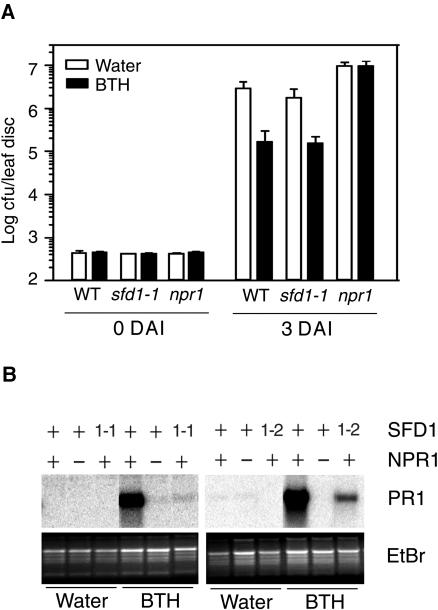

SA and BTH application activate a SAR-like response in A. thaliana. Therefore, we tested if BTH application enhanced resistance in the sfd1-1 plant. As shown in Figure 5A, in comparison with control plants that were previously treated with water, prior exposure to BTH conferred a comparable 30-fold reduction in the growth of P. s. maculicola in the sfd1-1 mutant and wild-type plants. By contrast, as expected, BTH was unable to enhance resistance in the SA/BTH nonresponsive npr1 mutant. Thus, the SAR deficiency in leaves of the sfd1-1 plant is most likely attributable to the lack of SAR-associated SA accumulation. Interestingly, however, as in the npr1 mutant, BTH was a poor inducer of PR1 expression in the leaves of the sfd1-1 and sfd1-2 mutants (Figure 5B). Similarly, SA was a poor inducer of PR1 expression in the sfd1-1 and sfd1-2 mutants (data not shown). This is in agreement with our earlier observation that the sfd1 mutant alleles affect PR1 expression in the ssi2-containing sfd1 ssi2 and sfd1 ssi2 npr1 plants at two steps (Nandi et al., 2003b). First, the sfd1 mutant alleles block the ssi2-conferred SA accumulation, and second, the sfd1 alleles compromise the ability of applied SA and BTH to restore PR1 expression in the sfd1 ssi2 and sfd1 ssi2 npr1 plants (Nandi et al., 2003b).

Figure 5.

Growth of P. s. maculicola and PR1 Transcript Accumulation in BTH-Treated Leaves of Wild-Type and Mutant Plants.

(A) Growth of P. s. maculicola in leaves of plants treated with BTH. Wild-type, sfd1-1, and npr1 plants were treated either with a suspension containing 100 μM BTH (black bar) or water (open bar). Two days later, four leaves of each plant were inoculated with a suspension containing 2.5 × 105 cfu/mL of P. s. maculicola. P. s. maculicola numbers in leaves were monitored on the day of challenge inoculation (0 DAI) and 3 DAI. All values are the mean of five samples ±sd.

(B) PR1 gene transcript accumulation in BTH-treated leaves. Fully expanded leaves from wild-type, npr1, sfd1-1 (1-1), and sfd1-2 (1-2) plants were floated on a suspension containing BTH or water. PR1 transcript accumulation was examined in RNA extracted from leaves 24 h after flotation in BTH or water. Blots were hybridized with a radiolabeled PR1 probe. The wild-type genotype at the NPR1 and SFD1 loci is designated by a plus sign. A minus sign designates the npr1-5 mutant allele, whereas 1-1 and 1-2 refer to the sfd1-1 and sfd1-2 mutant alleles. Gel loading was monitored by photographing the ethidium bromide (EtBr)–stained gel before transfer to the membrane.

Cloning of sfd1

Previously, the allelic sfd1-1 and sfd1-2 mutations were mapped to chromosome II in a 4.7-centimorgan (cM) interval spanned by the simple sequence length polymorphism (Bell and Ecker, 1994) marker nga168 and the SSI2 gene, 2.1 cM from nga168 and 2.6 cM from SSI2 (Nandi et al., 2003b). Additional PCR-based cleaved amplified polymorphic sequence (CAPS) (Konieczny and Ausubel, 1993) markers spanning this region were generated (see Methods). The mapping populations used consisted of F2 progeny plants derived from crosses involving the sfd1-1 ssi2 npr1 and sfd1-2 ssi2 npr1 plants with the fab2 (allelic with ssi2) mutant (ecotype Columbia), which is wild type at the SFD1 and NPR1 loci (see Methods). Recombination analysis with these markers placed sfd1 within a 237-kb region that is spanned by the PCR markers T2P4-1 and T3K9-1 (see Figure 2 in supplemental data online).

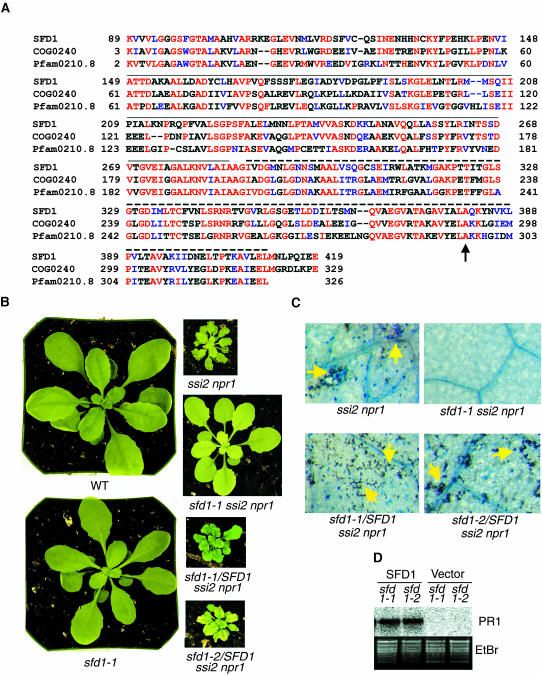

The altered glycerolipid composition in sfd1-2 (Figure 1) suggested the involvement of SFD1 in lipid metabolism. A scan of the 237-kb region on chromosome II between T2P4-1 and T3K9-1 identified the open reading frame (ORF) encoded by At2g40690 as a possible ORF involved in lipid metabolism (see below). An ∼1.6-kb At2g40690 transcript was detected in RNA gel blot experiments with RNA extracted from leaves of wild-type and sfd1-2 plants. In comparison with the mock-inoculated leaf, the At2g40690 transcript level was depressed in the pathogen-inoculated leaf of the wild-type plant (Figure 2C). Moreover, the basal level of this transcript was very low in RNA prepared from the untreated sfd1-1 plant (data not shown). This suggested that At2g40690 is SFD1. Sequencing of At2g40690 from the wild-type Nössen and the sfd1-1 and sfd1-2 mutants identified single nucleotide changes in this gene from sfd1-1 and sfd1-2. In sfd1-1, there is a G → A transition in a predicted splice acceptor site between intron 2 and exon 3 (see Figure 2 in supplemental data online), which may result in alternate splicing and thus explain the very low level of the At2g40690 transcript in sfd1-1. Reverse transcription–coupled PCR analysis has identified alternatively spliced cDNA clones from sfd1-1, supporting this hypothesis (A. Nandi and J. Shah, unpublished data). As shown in Figure 6A, in sfd1-2, a G → A transition is expected to cause an Ala381 to Thr381 missense mutation in the corresponding protein. The mutations in sfd1-1 and sfd1-2 result in Bsr1A and MseI restriction polymorphisms, respectively (see Figure 3 in supplemental data online), confirming that sfd1-1 and sfd1-2 contain mutations in At2g40690. A 5-kb wild-type genomic HindIII fragment that contains only the At2g40690 gene, when transformed into the sfd1-1 ssi2 npr1 and sfd1-2 ssi2 npr1 plants, restored the ssi2-conferred dwarfing (Figure 6B), development of spontaneous lesions (Figure 6C), and constitutive expression of the PR1 gene (Figure 6D). By contrast, the insert-less vector, when transformed into sfd1-1 ssi2 npr1 and sfd1-2 ssi2 npr1, did not restore these ssi2-phenotypes, confirming that At2g40690 is indeed SFD1.

Figure 6.

Cloning of SFD1.

(A) Alignment of the SFD1 sequence with the consensus sequence from COG0240 and Pfam0210.8. Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLASTp) analysis of the predicted SFD1 protein sequence revealed homology to DHAP reductases/G3P dehydrogenases in the COG2040 and Pfam0210.8 protein family data sets. The alignment of SFD1 amino acids 89 to 419 to the consensus sequence from COG2040 and Pfam0210.8 is shown. Solid and dashed lines above the SFD1 sequence mark the predicted NAD+ and substrate binding domains, respectively. The arrow indicates the Ala381 that is mutated to yield Thr381 in sfd1-2. Amino acids that are identical to SFD1 are shown in red and those that are similar are shown in blue.

(B) Complementation of the sfd1-1 and sfd1-2 mutants by SFD1. Comparison of the morphology of 4-week-old, soil-grown wild-type sfd1-1, ssi2 npr1, and sfd1-1 ssi2 npr1 plants and the sfd1-1/SFD1 ssi2 npr1 and sfd1-2/SFD1 ssi2 npr1 plants. sfd1-1/SFD1 ssi2 npr1 and sfd1-2/SFD1 ssi2 npr1 plants are sfd1-1 ssi2 npr1 and sfd1-2 ssi2 npr1 plants transformed with a 5-kb HindIII fragment containing the genomic SFD1 clone. The photographs were taken from the same distance.

(C) Restoration of the ssi2-conferred cell death by SFD1. Leaves from 4-week-old, soil-grown ssi2 npr1, sfd1-1 ssi2 npr1, sfd1-1/SFD1 ssi2 npr1, and sfd1-2/SFD1 ssi2 npr1 plants were stained with trypan blue. sfd1-1/SFD1 ssi2 npr1 and sfd1-2/SFD1 ssi2 npr1 plants are sfd1-1 ssi2 npr1 and sfd1-2 ssi2 npr1 plants transformed with a 5-kb HindIII fragment containing the genomic SFD1 clone. Trypan blue–stained leaves from the transgenic plants and from the ssi2 npr1 plants show intensely stained dead cells (yellow arrows). All of the photographs were taken at the same magnification.

(D) Restoration of the ssi2-conferred constitutive PR1 expression by SFD1. PR1 expression was monitored in 4-week-old, soil-grown sfd1-1 ssi2 npr1 (sfd1-1) and sfd1-2 ssi2 npr1 (sfd1-2) plants transformed with pBI121 (Vector) or with pBI121 containing a 5-kb HindIII genomic fragment spanning SFD1 (SFD1). Blots were hybridized with a radiolabeled PR1 probe. Gel loading was monitored by photographing the ethidium bromide (EtBr)–stained gel before transfer to the membrane.

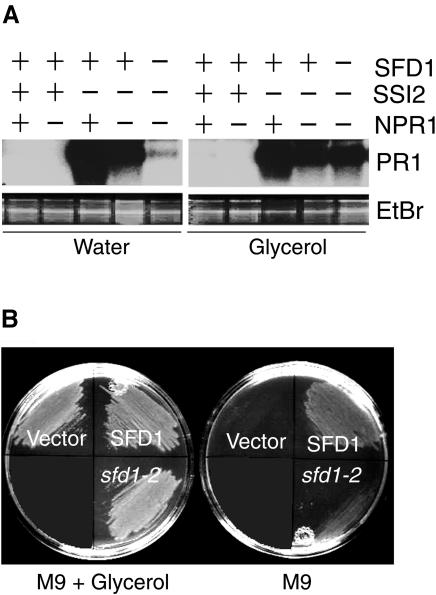

SFD1 Encodes a DHAP Reductase

As shown in Figure 6A, the predicted SFD1-encoded protein contains large stretches that exhibit homology to the consensus sequence of the protein family (Pfam) 0210.8 and cluster of orthologous groups (COG) 0240 (Tatusov et al., 1997, 2001). These two data sets contain prokaryotic and eukaryotic DHAP reductases/G3P dehydrogenases, which catalyze the interconversion of DHAP to G3P. In particular, the stretch of amino acids between positions 149 to 284 and 288 to 411 of SFD1, exhibit homology to the predicted NAD+ and substrate binding domain, respectively, of enzymes in COG0240 and Pfam0210.8. In sfd1-2, the highly conserved Ala residue, at position 381 in the putative substrate binding domain, is replaced by Thr. The lipid profile of sfd1-2 is similar to the lipid profile of the A. thaliana gly1 mutant (Miquel et al., 1998). Moreover, gly1 maps to the BAC T7D17, which contains SFD1, suggesting that sfd1 and gly1 are allelic (Miquel, 2000). Based on the lipid composition, it was predicted that the gly1 mutation affects G3P availability in plastids. Exogenously applied glycerol restored lipid composition in the gly1 mutant (Miquel et al., 1998), presumably because of its conversion to G3P by glycerol kinase, providing support to this hypothesis. Therefore, we tested whether glycerol application would restore the ssi2-conferred constitutive PR1 expression in the leaves of the sfd1-1 ssi2 npr1 plant. As shown in Figure 7A, although glycerol application was ineffective in activating PR1 expression in the wild-type and npr1 plants, it restored the ssi2-conferred constitutive PR1 expression in the leaves of the sfd1-1 ssi2 npr1 plant.

Figure 7.

SFD1 Encodes a DHAP Reductase.

(A) Loss of the constitutive PR1 expression phenotype of the sfd1-1 ssi2 npr1 plant is rescued by the application of glycerol. PR1 transcript levels were monitored in leaves of wild-type, npr1-5, ssi2, ssi2 npr1, and sfd1-1 ssi2 npr1 plants 48 h after treatment with glycerol (1%) or water. The plus and minus signs indicate wild-type and mutant genotypes, respectively, for the indicated genes. Blots were hybridized with a radiolabeled PR1 probe. Gel loading was monitored by photographing the ethidium bromide (EtBr)–stained gel before transfer to membrane.

(B) Functional complementation of the G3P auxotrophy of a DHAP reductase–deficient bacterial strain by SFD1. Growth of the E. coli DHAP reductase–deficient strain BB20-14 on minimal medium (M9) and minimal medium supplemented with 1% glycerol (M9 + Glycerol). BB20-14 was transformed with either the wild-type SFD1 or the sfd1-2 mutant cDNA clones. pGEM-T Easy (Vector)–transformed cells provided the negative control.

A bioassay was used to determine if SFD1 is indeed a DHAP reductase. Lack of DHAP reductase activity in the Escherichia coli gpsA mutant strain BB20-14 causes G3P auxotrophy, which can be complemented by exogenously provided glycerol (Cronan and Bell, 1974). We transformed constructs expressing the wild-type SFD1 cDNA and an identical cDNA construct containing the sfd1-2 mutation into E. coli BB20-14. As shown in Figure 7B, the wild-type SFD1 cDNA from ecotype Nössen complemented the DHAP reductase deficiency of BB20-14. By contrast, the insert-less vector did not complement the gpsA mutation. The sfd1-2 cDNA construct showed only weak complementation, thus indicating that SFD1 has DHAP reductase activity, which is compromised by the Ala381 to Thr381 alteration in SFD1-2.

DISCUSSION

Role of SFD1 in Glycerolipid Metabolism

The SFD1 gene encodes a DHAP reductase involved in glycerolipid metabolism. In comparison with the wild-type, the composition of leaf plastid-localized glycerolipids was altered in sfd1-2 (Figure 1). However, no significant changes were observed in the molecular composition of the nonplastidic glycerolipids PC, PE, and PI in the leaves of sfd1-2 (see Figure 1 in supplemental data online), suggesting that SFD1 functions in the plastid. Indeed, the iPSORT tool (http://www.hypothesiscreator.net/iPSORT/) predicts a plastid targeting sequence at the N terminus of the SFD1 protein (A. Nandi and J. Shah, unpublished data). Some glycerolipid synthesis by the prokaryotic pathway was retained in the sfd1 mutants, suggesting that either the sfd1-1 and sfd1-2 alleles have partial activity or that the residual prokaryotic glycerolipid biosynthesis is attributable to the existence of a functionally redundant activity. A. thaliana contains at least one additional plastid-localized DHAP reductase, AtGPDHp, encoded by At5g40610 (Wei et al., 2001). However, the role of AtGPDHp in glycerolipid metabolism is not known. Furthermore, G3P biosynthetic pathways also are present in the cytoplasm. However, the contribution of G3P synthesized in the cytoplasm to the plastidic G3P content and, hence, plastid lipid biosynthesis is not known. The fact that glycerol application restores the plastid lipid composition in the A. thaliana gly1-1 mutant (Miquel et al., 1998) and restores the ssi2-conferred PR1 expression in the sfd1 ssi2 npr1 plants (Figure 7A) suggests that some exchange between the cytosolic and plastidic G3P pools may occur.

The amount of the 18:3-16:3–containing 34:6-MGDG was lower in the leaves of the sfd1-2 mutant than in the leaves of wild-type plants (Figure 1). In parallel, there is an increase in the amount of the 18:3-18:3–containing 36:6-MGDG and -DGDG. A similar glycerolipid composition was observed in the gly1-1 mutant (Miquel et al., 1998). The gly1-1 mutant maps to the same BAC, T7D17, which contains SFD1 (Miquel, 2000). In addition, glycerol application complements the gly1-1 glycerolipid deficiency (Miquel et al., 1998) and overcomes the sfd1-conferred block of ssi2-mediated PR1 expression in the sfd1-1 ssi2 npr1 and sfd1-2 ssi2 npr1 plants (Figure 7A), suggesting that sfd1 and gly1-1 are allelic. As previously noted for gly1-1, in the sfd1 mutant, the reduction in glycerolipid synthesis by the prokaryotic pathway is accompanied by an increase in the incorporation into plastidic glycerolipids of moieties synthesized by the eukaryotic pathway. Similar changes also have been observed in the act1 mutant, which is deficient in a plastid-localized G3P-acyl transferase activity (Kunst et al., 1988). Interestingly, despite the lesion in the prokaryotic glycerolipid biosynthesis pathway in the sfd1-1, sfd1-2, gly1-1, and act1-1 mutants, these plants do not exhibit any obvious morphological, growth, and developmental deficiencies. This suggests that membrane lipid composition in A. thaliana is tightly regulated but flexible.

In A. thaliana leaves, the 34:3-containing nonplastidic lipid species PC, PE, and PI are primarily represented by a 16:0-18:3 acyl combination, but small amounts of 16:1-18:2 and 16:3-18:0 acyl combinations also are present (Welti et al., 2002; Nandi et al., 2003b). We previously have reported that in comparison with the ssi2 npr1 plant, the total content of 34:3-PC, 34:3-PE, and 34:3-PI were depressed in leaves of the sfd1 ssi2 npr1 plant (Nandi et al., 2003b). However, our study of the sfd1 single mutant plant indicates that the alterations in levels of these nonplastidic species in the sfd1 ssi2 npr1 plant may not be a direct result of the sfd1 mutation; no significant alterations in the level of 34:3-PC, 34:3-PE, and 34:3-PI were observed between the wild-type and the sfd1 single mutant plants (see Figure 1 in supplemental data online).

Role of SFD1 in Plant Defense Response

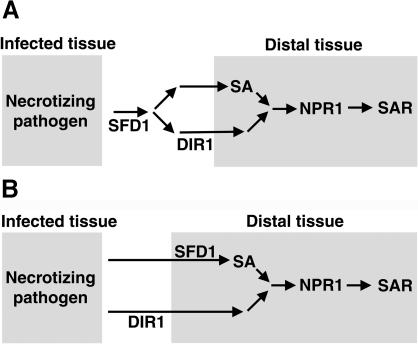

The sfd1 mutation compromises SAR. Similarly, SAR also is compromised in the SA-nonresponsive npr1/nim1 (Cao et al., 1994; Delaney et al., 1995) and the SA biosynthesis–deficient eds5/sid1 and eds16/sid2 mutants (Nawrath and Metraux, 1999). However, unlike the sfd1 mutants, these other mutants also depress basal resistance to pathogens. The failure of SAR in sfd1 is associated with the inability of the mutant to accumulate SA in the distal leaf (Figure 4). However, unlike EDS5/SID1 and EDS16/SID2, SFD1 is not involved in SA biosynthesis per se; SA does accumulate to high levels in the pathogen-inoculated leaves of the sfd1 mutants (Figure 4). Thus, an SFD1-dependent signal functions to regulate SA accumulation in the SAR-expressing wild-type leaf. The SAR deficiency phenotype of the sfd1 mutant is less severe than that of the npr1 mutant (Figure 3A). However, the SAR deficiency phenotype of sfd1-1 npr1 and sfd1-2 npr1 double mutants is comparable to that of the npr1 single mutant, suggesting that NPR1 is required downstream of SFD1 in the activation of SAR-conferred enhanced resistance to P. s. maculicola (A. Nandi and J. Shah, unpublished data). Our results with the sfd1 mutant indicate that the upstream signaling leading to the accumulation of SA during the activation of SAR differs slightly from that in basal resistance to pathogens. Past studies have suggested the presence of a phloem mobile signal, which traverses from the pathogen-inoculated tissue to the distal tissue where SAR is activated (Ross, 1966). SFD1 could be directly or indirectly required for the synthesis of this mobile signal in SAR. It is equally likely that SFD1 is required for the transmission of the mobile signal or for its perception/signal transmission in the distal organs. Alternatively, SFD1 may be required in parallel with the mobile signal for the activation of SAR. Like the sfd1 mutants, the dir1-1 mutant also is compromised in the activation of SAR (Maldonado et al., 2002). However, unlike the sfd1 mutants, dir1-1 does not compromise the SAR-associated accumulation of elevated SA levels. Studies with petiole exudates suggest that a DIR1-dependent factor/signal may be required for the generation/transmission of a factor that is needed in parallel with SA accumulation for the activation of SAR. SFD1 could be required at a point before the requirement of DIR1 in the activation of SAR (Figure 8A). DIR1 is a putative lipid transfer protein. A lipid molecule generated by an SFD1-dependent pathway may be the lipid moiety transferred by DIR1. Alternatively, SFD1 and DIR1 may define two arms of the SAR activation mechanism. Although SFD1 is required for the activation of SA synthesis in the tissue expressing SAR, a DIR1-dependent factor may be required for the generation/transmission of a mobile signal that is needed in parallel with SA accumulation for the activation of SAR (Figure 8B).

Figure 8.

Working Model: Interaction of SFD1, DIR1, and NPR1 in SAR.

SFD1, DIR1, and NPR1 are required for the activation of SAR-conferred enhanced resistance to P. s. maculicola. Although NPR1 functions downstream of SA, DIR1 is required for the generation/transmission of a mobile signal that is needed in parallel to SA accumulation for the activation of SAR-conferred enhanced resistance to P. s. maculicola. By contrast, SFD1 is required upstream of SA in the activation of the SAR-conferred enhanced resistance to P. s. maculicola. In comparison with the npr1 mutant, the residual SAR that is prevalent in the sfd1-1 and sfd1-2 mutants is lost in the sfd1-1 npr1 and sfd1-2 npr1 double mutants, suggesting that NPR1 is required downstream of SFD1 in the activation of the SAR-conferred enhanced resistance to P. s. maculicola. The genetic interaction between SFD1 and DIR1 is not known. Two alternative models are discussed in (A) and (B).

(A) In response to infection by a necrotizing pathogen, SFD1 is required for the generation/transmission of a factor that is involved in the activation of SA synthesis in the distal tissue and for the generation of the DIR1-dependent signal/factor in the SAR-conferred enhanced resistance to P. s. maculicola. Whether SFD1 functions in the pathogen-infected tissue or outside the pathogen-infected tissue is not known. SA plus a DIR1-dependent factor(s) activate signaling through the NPR1 pathway leading to the activation of SAR-conferred enhanced resistance to P. s. maculicola.

(B) In this model, the pathogen-infected tissue is shown to synthesize two signals. One of these signals is required for the activation of the DIR1-dependent arm, upstream of SAR, and the other stimulates the SFD1-dependent activation of SA synthesis in the distal tissue. Though SFD1 is shown to function in the distal tissue, it is equally possible that SFD1 functions outside the distal tissue. SA plus the DIR1-dependent factor(s) activate signaling through the NPR1 pathway leading to the activation of SAR-conferred enhanced resistance to P. s. maculicola.

The sfd1-1 and sfd1-2 mutants were identified as suppressors of ssi2 (Nandi et al., 2003b), suggesting that SAR is one of the defense mechanisms that is constitutively active in the ssi2 mutant. SSI2 encodes a fatty acid desaturase, which primarily catalyzes the desaturation of stearic acid to oleic acid in the plastids (Kachroo et al., 2001). Previously, we have shown that lowered levels of 16:3-containing lipids is a common alteration associated with the suppression of ssi2-conferred defense phenotypes by mutant alleles in the sfd1, sfd2, and sfd4/fad6 complementation groups (Nandi et al., 2003b). These studies provided strong evidence for the involvement of a lipid(s) in the ssi2-conferred enhanced disease resistance. Here, we have shown that recessive mutations in SFD1 simultaneously alter leaf plastid glycerolipid metabolism and the activation of SAR. Therefore, we hypothesize that the altered composition of one or more lipids in the sfd1 mutants compromises the activation of SAR. A role for lipid(s) in SAR also is consistent with the observation that loss of the DIR1-encoded putative lipid-transfer protein activity compromises the activation of SAR in A. thaliana (Maldonado et al., 2002). Similarly, the RNA interference–mediated suppression of expression of the N. tabacum SA BINDING PROTEIN2 gene, which encodes an SA binding and SA-activated lipase, compromises the activation of SAR in transgenic N. tabacum (D. Kumar and D. F. Klessig, personal communication).

We have reported previously that exogenously applied SA and BTH were poor inducers of PR1 expression in the sfd1 ssi2 and sfd1 ssi2 npr1 plants (Nandi et al., 2003b). This result, combined with the poor expression of PR1 observed in BTH-treated leaves of the sfd1 single mutant plant (Figure 5B), suggests that a SFD1-dependent factor is required for the SA/BTH induced high level expression of the PR1 gene in wild-type plants. The involvement of a lipid-derived factor in the SA/BTH-mediated activation of PR1 expression is consistent with a previous study in which it was shown that inhibitors of lipid peroxidation depressed the SA-activated expression of the N. tabacum PR1 gene (Anderson et al., 1998). However, despite the poor expression of PR1 in BTH-treated sfd1 leaves, BTH application was equally effective in enhancing the basal resistance to P. s. maculicola in the wild-type and the sfd1 mutant plants (Figure 5A). These results suggest that the low level of SA/BTH-activated PR1 expression observed in the sfd1 mutant is sufficient for enhancing resistance to P. s. maculicola. Alternatively, PR1 expression may not be important for the enhanced resistance to P. s. maculicola conferred by SA and BTH application. Similarly, studies with the A. thaliana ssi1 and cpr mutants have disassociated the ssi1- and cpr-conferred high level PR1 expression from the enhanced resistance to P. s. maculicola prevalent in these mutants (Clarke et al., 2000; Nandi et al., 2003a).

SFD1 transcript accumulation is repressed in leaves inoculated with pathogens (Figure 2C). Similarly, the accumulation of the A. thaliana NHO1 transcript is repressed by pathogen inoculation (Kang et al., 2003). NHO1 encodes a glycerol kinase involved in G3P metabolism. Interestingly, the nho1 mutant exhibits enhanced susceptibility to avirulent and nonhost strains of Pseudomonas (Lu et al., 2001). Moreover, overexpression of NHO1 enhances basal resistance to P. syringae. Along with results presented here, these data suggest that G3P metabolism in A. thaliana is an important target for pathogenesis by P. syringae.

In summary, we show here that mutations in the SFD1 gene, which affect plastidic glycerolipid composition, simultaneously compromise the activation of SAR without impacting basal resistance to P. syringae, suggesting that lipids may be involved in the activation of SAR. Though the exact identity of the SFD1-dependent molecule(s) and the mechanism by which it exerts its effects on SAR is unclear, the profiling of metabolic changes in pathogen-challenged and distal organs of wild-type and mutant plants should facilitate our understanding of the role of SFD1 in SAR.

METHODS

Cultivation of Plants and Pathogens

A. thaliana plants and P. s. maculicola ES4326 were cultivated as previously described (Nandi et al., 2003a). P. s. tomato DC3000 containing avrRpt2 was grown in King's medium (King et al., 1954) with 25 mg/L of rifampicin and 50 mg/L of kanamycin.

Bacterial Inoculation of Plants

Four-week-old, soil-grown plants were used for inoculation with P. s. maculicola ES4326 and P. s. tomato DC3000 containing avrRpt2. Bacterial inoculations were performed as previously described (Shah et al., 1997; Nandi et al., 2003a). To activate SAR, two fully expanded leaves of each plant were infiltrated (1° inoculation) with a suspension containing 107 colony-forming units (cfu) per milliliter of P. s. tomato carrying the avirulence gene avrRpt2. In parallel, plants that were similarly infiltrated with 10 mM MgCl2 served as the controls. To monitor the SAR-conferred enhanced resistance, 2 d after the 1° inoculation with P. s. tomato carrying avrRpt2 or mock treatment, four other leaves of each plant were challenged with a suspension containing 2.5 × 105 cfu/mL of P. s. maculicola. Bacterial growth was monitored at 0 and 3 DAI of P. s. maculicola. For each time point, 15 (five replications of three leaves in each sample) leaf disks (0.38 cm2) were harvested. Leaf samples were ground in 10 mM MgCl2 and bacterial counts determined as previously described (Shah et al., 1997; Nandi et al., 2003a). Bacterial counts are expressed as colony-forming units per leaf disc.

Map-Based Cloning of SFD1

sfd1-1 ssi2 npr1 and sfd1-2 ssi2 npr1 plants (Nössen ecotype) were crossed with the fab2-1 (allelic with ssi2) mutant, which is in the ecotype Columbia. The large F2 segregants, lacking macroscopic lesions and not expressing PR1, were presumed to be homozygous for the sfd1 mutant alleles. These were used for mapping. DNA from these F2 sfd1 homozygous plants were tested by PCR for linkage to the polymorphic markers nga168 and Bio2, (http://www/arabidopsis.org) and the derived CAPS marker for ssi2 (Kachroo et al., 2001). Additionally, the following CAPS markers were designed for the interval between nga168 and Bio2 on chromosome II: T2P4-1 at 16,830 kb (PCR amplification with the primers 5′-ACCAGACAAAAGTTCTTAGCC-3′ and 5′-ATTTGATCTACCCCACTCTCC-3′ followed by restriction digestion with AflII), T2P4-2 at 16,893 kb (PCR amplification with the primer pair 5′-GAACCGAAACTAAACGCCTAC-3′ and 5′-ACTTGACCACTGAAGATTGCC-3′ followed by restriction digestion with XmnI), T7D17-1 at 16,940 kb (PCR amplification with the primer pair 5′-CTATACTCACCCGATCAGACC-3′ and 5′-TGTTCTTAACCCATTCAAGCC-3′ followed by restriction digestion with NlaIV), T20B5-1 at 17,006 kb (PCR amplification with the primer pair 5′-CGTGCCGCTTTTTGTTTTT-3′ and 5′-CGTTACTTACATGCGTACC-3′ followed by digestion with AseI), and T3K9-1 at 17,067 kb (PCR amplification with the primer pair 5′-GCTGACCCCAATGCTCTAAAG-3′ and 5′-ATGCAACCAACAGATCCAAAG-3′ followed by digestion with MboII).

The genomic DNA spanning ORF T7D17.13, which is a putative DHAP reductase, was amplified from the wild-type Nössen and the sfd1-1 and sfd1-2 mutants with several primer pairs. The amplicons were purified and sequenced. BLAST analysis was used for pair-wise alignment of sequences from Nössen and the sfd1-1 and sfd1-2 mutants. The sfd1-1 allele can be distinguished from the wild-type SFD1 allele by PCR amplification with the primer pair G3P-F1 (5′-CAGAGAGGTAGACGACATAGA-3′) and G3P-R1 (5′-GGATATTATCATAGCCCAGCAG-3′) followed by restriction digestion with the restriction enzyme Bsr1A (New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA) and resolution of bands on a 1.5% agarose gel. The sfd1-2 allele can be distinguished from the wild-type SFD1 allele by PCR amplification with the primer pair G3P-F3 (5′-GTCTCAGATCATTCCCATTGC-3′) and G3P-R2 (5′-AACGAATGCAAAGCTCTTGCCG-3′) followed by digestion with the restriction enzyme MseI (New England Biolabs) and resolution of bands on a 2.0% agarose gel.

Complementation Analysis and Plant Transformation

The BAC T7D17 was obtained from the Arabidopsis Stock Center at Ohio State University. The DNA was digested with HindIII (New England Biolabs) and ligated into pBluescript SK+ (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) that had been linearized with HindIII. The ligated DNA was electroporated into the E. coli strain TG1. Colony hybridization was used to identify transformants containing the SFD1 DNA. A 5-kb HindIII fragment then was further subcloned into the HindIII site of the binary vector pBI121 (Clonetech, San Fransisco, CA). The resultant plasmid pBI121-SFD1 was electroporated into the Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101. Gentamycin (25 mg/L) plus kanamycin (50 mg/L) resistant transformants were selected. Presence of the SFD1 gene in the GV3101 transformants was confirmed by PCR. A pBI121-SFD1 containing GV3101 transformant was used to transform sfd1-1 ssi2 npr1 and sfd1-2 ssi2 npr1 plants by the floral dip method (Clough and Bent, 1998). Kanamycin-resistant seeds were selected on MS agar plates (Gibco BRL, Bethesda, MD) supplemented with kanamycin (50 mg/L). Presence of the transgene was confirmed by PCR analysis.

Lipid Extraction and ESI-MS/MS Analysis

Lipid extraction and ESI-MS/MS analysis of glycerolipids was performed as previously described (Welti et al., 2002).

E. coli Complementation Assay

Full-length SFD1 and sfd1-2 cDNA were generated by reverse transcription PCR and cloned into the pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega, Madison, WI). The clones were sequenced and sequence compared with the genomic sequence of SFD1. The vector and full-length SFD1 and sfd1-2 clones were transformed into the E. coli gpsA strain BB20-14 (Cronan and Bell, 1974), which was obtained from the E. coli Genetic Stock Center at Yale University. BB20-14 was maintained in M9 medium (Sambrook et al., 1989) supplemented with 0.4% glucose, 10 mM MgSO4, and 0.1% glycerol (v/v). BB20-14 transformants were washed and suspended in 500 μL of sterile water. A volume of 10 μL was streaked in M9 plates with or without glycerol (1%), supplemented with 0.4% glucose and 10 mM MgSO4. Plates were incubated at 37°C.

Chemical Treatment of Leaves and Plants

BTH (100 μM) treatments were performed as previously described (Shah et al., 1997). For glycerol treatment, excised leaves from 4-week-old plants were floated on 5 mL of 1% glycerol in a tissue culture plate and incubated at 22°C in growth chambers programmed for a 14-h-light (90 μE/m2/s) and 10-h-dark cycle. After 24 h, leaves were harvested and RNA was extracted as previously described (Shah et al., 1997; Nandi et al., 2003a).

Trypan Blue Staining

Leaves excised from 4-week-old plants were stained with trypan blue as previously described (Rate et al., 1999).

SA Quantitation

For each sample, 0.2 g of leaves were harvested and quickly frozen in liquid N2. Frozen samples were ground and extracted once with 3 mL of 90% methanol and once with 3 mL of 100% methanol. The combined extracts were dried under N2 gas and suspended in 2.5 mL of 5% trichloroacetic acid. The samples were acid hydrolyzed by adding 200 μL of HCl and incubating in a boiling water bath for 30 min. SA was extracted with 5 mL of a mixture containing cyclohexane:ethylacetate:isopropanol (50:50:1). The sample was dried under N2 gas and dissolved in 0.5 mL of the mobile phase (69:27:4 mix of water:methanol:glacial acetic acid) (Dadgar et al., 1985). Samples were filtered through a 0.22-μm filter, and 20 to 100 μL were used for high performance liquid chromatography. Samples were passed over a 4.6 × 250-mm C18 reverse-phase column, and SA was eluted with the mobile phase at a flow rate of 0.8 mL/min. Absorbance of the eluted samples was recorded at 310 nm, and SA concentrations were determined by comparison with SA standards.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank M.R. Roth for assistance with the SA analysis, C.M. Buseman for assistance with lipid data analysis, J. Morton and H. Smith for assistance with DNA extractions, T.D. Williams for acquiring the mass spectral data, and X. Wang for discussions. This material is based upon work supported by the Cooperative State Research, Education, and Extension Service of the USDA under Agreement 2002-35319-11655 and Grant MCB-0110979 from the National Science Foundation to J.S. and R.W. and is supported by Kansas National Science Foundation Experimental Program to Stimulate Competitive Research. Fellowships from the Kansas Biomedical Research Infrastructure Network provided support for C.M. Buseman and J. Morton. J.S. also would like to acknowledge the National Science Foundation for Major Research Instrumentation Grant DBI-0079539, which provided for plant growth chambers to carry out this work. This is Kansas Agricultural Experimental Station contribution number 03-413-J.

On-line version contains Web-only data.

The author responsible for distribution of materials integral to the findings presented in this article in accordance with the policy described in the Instructions for Authors (www.plantcell.org) is: Jyoti Shah (shah@ksu.edu).

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at www.plantcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1105/tpc.016907.

References

- Anderson, M.D., Chen, Z., and Klessig, D.F. (1998). Possible involvement of lipid peroxidation in salicylic acid-mediated induction of PR1 gene expression. Phytochemistry 47, 555–566. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, C.J., and Ecker, J.R. (1994). Assignment of 30 microsatellite loci to the linkage map of Arabidopsis. Genomics 19, 137–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browse, J., Warwick, N., Somerville, C.R., and Slack, C.R. (1986). Fluxes through the prokaryotic and eukaryotic pathways of lipid synthesis in the ‘16:3’ plant Arabidopsis thaliana. Biochem. J. 235, 25–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao, H., Bowling, S.A., Gordon, A.S., and Dong, X. (1994). Characterization of an Arabidopsis mutant that is nonresponsive to inducers of systemic acquired resistance. Plant Cell 6, 1583–1592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, J.D., Volko, S.M., Ledford, H., Ausubel, F.M., and Dong, X. (2000). Roles of salicylic acid, jasmonic acid, and ethylene in cpr-induced resistance in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 12, 2175–2190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clough, S.J., and Bent, A.F. (1998). Floral dip: A simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 16, 735–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronan, J.E., and Bell, R.M. (1974). Mutants of Escherichia coli defective in membrane phospholipid synthesis: Mapping of the structural gene for L-glycerol 3-phosphate dehydrogenase. J. Bacteriol. 118, 598–605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dadgar, D., Climax, J., Lambe, R., and Darragh, A. (1985). High-performance liquid chromatographic determination of certain salicylates and their major metabolites in plasma following topical administration of a liniment to healthy subjects. J. Chromatogr. 342, 315–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaney, T.P., Friedrich, L., and Ryals, J.A. (1995). Arabidopsis signal transduction mutant defective in chemically and biologically induced disease resistance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92, 6602–6606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaney, T.P., Uknes, S., Vernooij, B., Friedrich, L., Weymann, K., Negrotto, D., Gaffney, T., Gut-Rella, M., Kessmann, H., Ward, E., and Ryals, J. (1994). A central role of salicylic acid in plant disease resistance. Science 266, 1247–1250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De León, I.P., Sanz, A., Hamberg, M., and Castresana, C. (2002). Involvement of the Arabidopsis alpha-DOX1 fatty acid dioxygenase in protection against oxidative stress and cell death. Plant J. 29, 61–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Wit, P.J.G.M. (1998). Pathogen avirulence and plant resistance: A key role for recognition. Trends Plant Sci. 2, 452–458. [Google Scholar]

- Falk, A., Feys, B.J., Frost, L.N., Jones, J.D.G., Daniels, M.J., and Parker, J.E. (1999). EDS1, an essential component of R gene-mediated disease resistance in Arabidopsis has homology to eukaryotic lipases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 3292–3297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gee, R.E., Byerrum, R.U., Gerber, D.W., and Tolbert, N.E. (1988). Dihyroxyacetone phosphate reductases in plants. Plant Physiol. 86, 98–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, S., and Sastry, P.S. (1988). Triacylglycerol synthesis in developing seeds of groundnut (Arachis hypogaea): Pathway and properties of enzymes of sn-glycerol-3-phosphate formation. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 262, 508–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glazebrook, J., Rogers, E.E., and Ausubel, F.M. (1996). Isolation of Arabidopsis mutants with enhanced disease susceptibility by direct screening. Genetics 143, 973–982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman, R.N., and Novacky, A. (1994). The Hypersensitive Response in Plants to Pathogens: A Resistance Phenomenon. (St. Paul, MN: American Phytopathological Society Press).

- Hammerschmidt, R. (1999). Induced resistance: How do induced plants stop pathogens? Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 55, 77–84. [Google Scholar]

- Hammond-Kosack, K.E., and Jones, J.D.G. (1996). Resistance gene-dependent plant defense responses. Plant Cell 8, 1773–1791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hippman, Z., and Heinz, E. (1976). Glycerol kinase in leaves. Z. Pflanzenphysiol. 79, 408–418. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt, M., and Ryals, J. (1996). Systemic acquired resistance signal transduction. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 15, 583–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jirage, D., Tootle, T.L., Reuber, T.L., Frost, L.N., Feys, B.J., Parker, J.E., Ausubel, F.M., and Glazebrook, J. (1999). Arabidopsis thaliana PAD4 encodes a lipase-like gene that is important for salicylic acid signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 13583–13588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kachroo, P., Shanklin, J., Shah, J., Whittle, E.J., and Klessig, D.F. (2001). A fatty acid desaturase modulates the activation of defense signaling pathways in plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 9448–9453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang, L., Li, J., Zhao, T., Xiao, F., Tang, X., Thilmony, R., He, S.-Y., and Zhou, J.-M. (2003). Interplay of the Arabidopsis non-host resistance gene NHO1 with bacterial virulence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 3519–3524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King, E.O., Ward, M.K., and Raney, D.E. (1954). Two simple media for the demonstration of phycocyanin and fluorescein. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 44, 301–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirsch, T., Gerber, D.W., Byerrum, R.U., and Tolbert, N.E. (1992). Plant dihyroxyacetone phosphate reductases. Plant Physiol. 100, 352–359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klessig, D.F., and Malamy, J. (1994). The salicylic acid signal in plants. Plant Mol. Biol. 26, 1439–1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kombrink, E., and Somssich, I.E. (1997). Pathogenesis-related proteins and plant defense. In Plant Relationships. G.C. Carroll and P. Tudzynski, eds (Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag), pp. 107–128.

- Konieczny, A., and Ausubel, F.M. (1993). A procedure for mapping Arabidopsis mutations using co-dominant ecotype-specific PCR-based markers. Plant J. 4, 403–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunst, L., Browse, J., and Somerville, C. (1988). Altered regulation of lipid biosynthesis in a mutant of Arabidopsis deficient in chloroplast glycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferase activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 85, 4143–4147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawton, K.A., Friedrich, L., Hunt, M., Weymann, K., Delaney, T., Kessmann, H., Staub, T., and Ryals, J. (1996). Benzothiadiazole induces disease resistance in Arabidopsis by activation of the systemic acquired resistance signal transduction pathway. Plant J. 10, 71–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu, M., Tang, X., and Zhou, J.-M. (2001). Arabidopsis NHO1 is required for general resistance against Pseudomonas bacteria. Plant Cell 13, 437–447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malamy, J., Carr, J.P., Klessig, D.F., and Raskin, I. (1990). Salicylic acid: A likely endogenous signal in the resistance response of tobacco to viral infection. Science 250, 1002–1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maldonado, A.M., Doerner, P., Dixon, R.A., Lamb, C.J., and Cameron, R.K. (2002). A putative lipid transfer protein involved in systemic resistance signaling in Arabidopsis. Nature 419, 399–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Métraux, J.-P., Signer, H., Ryals, J., Ward, E., Wyss-Benz, M., Gaudin, J., Raschdorf, K., Schmid, E., Blum, W., and Inverard, B. (1990). Increase in salicylic acid at the onset of systemic acquired resistance in cucumber. Science 250, 1004–1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miquel, M. (2000). Complex lipid biosynthesis: The Kennedy pathway. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 28, 675–677. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miquel, M., Cassagne, C., and Browse, J. (1998). A new class of Arabidopsis mutants with reduced hexadecatrienoic acid fatty acid levels. Plant Physiol. 117, 923–930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mongrand, S., Cassagne, C., and Bessoule, J.J. (2000). Import of lyso-phosphatidylcholine into chloroplasts likely at the origin of eukaryotic plastidial lipids. Plant Physiol. 22, 845–852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nandi, A., Kachroo, P., Fukushige, H., Hildebrand, D.F., Klessig, D.F., and Shah, J. (2003. a). Ethylene and jasmonic acid signaling pathways affect NPR1-independent expression of defense genes without impacting resistance to Pseudomonas syringae and Peronospora parasitica in the Arabidopsis ssi1 mutant. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 16, 588–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nandi, A., Krothapalli, K., Buseman, C.M., Li, M., Welti, R., Enyedi, A., and Shah, J. (2003. b). Arabidopsis sfd mutants affect plastidic lipid composition and suppress dwarfing, cell death, and the enhanced disease resistance phenotypes resulting from the deficiency of a fatty acid desaturase. Plant Cell 15, 2383–2398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nawrath, C., and Metraux, J.P. (1999). Salicylic acid induction-deficient mutants of Arabidopsis express PR-2 and PR-5 and accumulate high levels of camalexin after pathogen inoculation. Plant Cell 11, 1393–1404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen, J.B., Hammerschmidt, R., and Zook, M.N. (1991). Systemic induction of salicylic acid accumulation in cucumber after inoculation with Pseudomonas syringae. Plant Physiol. 97, 1342–1347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rate, D.N., Cuenca, J.V., Bowman, G.R., Guttman, D.S., and Greenberg, J.T. (1999). The gain-of-function Arabidopsis acd6 mutant reveals novel regulation and function of the salicylic acid signaling pathway in controlling cell death, defense, and cell growth. Plant Cell 11, 1695–1708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross, A.F. (1966). Systemic effects of local lesion formation. In Viruses of Plants. A.B.R. Beemster and J. Dijkstra, eds (Amsterdam, The Netherlands: North-Holland), pp. 127–150.

- Ryals, J.A., Neuenschwander, U.H., Willits, M.G., Molina, A., Steiner, H.-Y., and Hunt, M.D. (1996). Systemic acquired resistance. Plant Cell 8, 1809–1819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook, J., Fritsch, E.F., and Maniatis, T. (1989). Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual, 2nd ed. (Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press).

- Scofield, S.R., Tobias, C.M., Rathjen, J.P., Chang, J.H., Lavell, D.T., Michelmore, R.W., and Staskawicz, B.J. (1996). Molecular basis of gene-for-gene specificity in bacterial speck disease of tomato. Science 274, 2063–2065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah, J., Kachroo, P., and Klessig, D.F. (1999). The Arabidopsis ssi1 mutation restores pathogenesis-related gene expression in npr1 plants and renders defensin gene expression SA dependent. Plant Cell 11, 191–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah, J., Kachroo, P.K., Nandi, A., and Klessig, D.F. (2001). A recessive mutation in the Arabidopsis SSI2 gene confers SA- and NPR1-independent expression of PR genes and resistance against bacterial and oomycete pathogens. Plant J. 25, 563–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah, J., Tsui, F., and Klessig, D.F. (1997). Characterization of a salicylic acid-insensitive mutant (sai1) of Arabidopsis thaliana, identified in a selective screen utilizing the SA-inducible expression of the tms2 gene. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 10, 69–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somerville, C., Browse, J., Jaworski, J.G., and Ohrologge, J.B. (2000). Lipids. In Biochemistry and Molecular Biology of Plants. B. Buchanan, W. Gruissem, and R. Jones, eds (Rockville, MD: American Society of Plant Biologists), pp. 456–527.

- Tang, X., Frederick, R.D., Zhou, J., Halterman, D.A., Jia, Y., and Martin, G.B. (1996). Initiation of plant disease resistance by physical interaction of AvrPto and the Pto kinase. Science 274, 2060–2063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatusov, R.L., Koonin, E.V., and Lipman, D.J. (1997). A genomic perspective on protein families. Science 278, 631–637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatusov, R.L., Natale, D.A., Garkavtsev, I.V., Tatusova, T.A., Shankavaram, U.T., Rao, B.S., Kiryutin, B., Galperin, M.Y., Fedorova, N.D., and Koonin, E.V. (2001). The COG database: New developments in phylogenetic classification of proteins from complete genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 29, 22–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Loon, L.C. (2000). Systemic induced resistance. In Mechanisms of Resistance to Plant Diseases. A.J. Slusarenko, R.S.S. Fraser, and L.C. Van Loon, eds (Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Press), pp. 521–574.

- Vernooij, B., Friedrich, L., Morse, A., Reist, R., Kolditz-Jawhar, R., Ward, E., Uknes, S., Kessmann, H., and Ryals, J. (1994). Salicylic acid is not the translocated signal responsible for inducing systemic acquired resistance but is required in signal transduction. Plant Cell 6, 959–965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallis, J.G., and Browse, J. (2002). Mutants of Arabidopsis reveal many roles for membrane lipids. Prog. Lipid Res. 41, 254–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Y., Periappuram, C., Datla, R., Selvaraj, G., and Zou, J. (2001). Molecular and biochemical characterization of a plastidic glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase from Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 39, 841–848. [Google Scholar]

- Welti, R., Li, W., Li, M., Sang, Y., Biesiada, H., Zhou, H.-E., Rajashekar, C.B., Williams, T.D., and Wang, X. (2002). Profiling membrane lipids in plant stress response. Role of phospholipase D alpha in freezing-induced lipid changes in Arabidopsis. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 31994–32002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.