Abstract

Objective To determine, in one low income country (Nepal), which characteristics of medical students are associated with graduate doctors staying to practise in the country or in its rural areas.

Design Observational cohort study.

Setting Medical college registry, with internet, phone, and personal follow-up of graduates.

Participants 710 graduate doctors from the first 22 classes (1983-2004) of Nepal’s first medical college, the Institute of Medicine.

Main outcome measures Career practice location (foreign or in Nepal; in or outside of the capital city Kathmandu) compared with certain pre-graduation characteristics of medical student.

Results 710 (97.7%) of the 727 graduates were located: 193 (27.2%) were working in Nepal in districts outside the capital city Kathmandu, 261 (36.8%) were working in Kathmandu, and 256 (36.1%) were working in foreign countries. Of 256 working abroad, 188 (73%) were in the United States. Students from later graduating classes were more likely to be working in foreign countries. Those with pre-medical education as paramedics were twice as likely to be working in Nepal and 3.5 times as likely to be in rural Nepal, compared with students with a college science background. Students who were academically in the lower third of their medical school class were twice as likely to be working in rural Nepal as those from the upper third. In a regression analysis adjusting for all variables, paramedical background (odds ratio 4.4, 95% confidence interval 1.7 to 11.6) was independently associated with a doctor remaining in Nepal. Rural birthplace (odds ratio 3.8, 1.3 to 11.5) and older age at matriculation (1.1, 1.0 to 1.2) were each independently associated with a doctor working in rural Nepal.

Conclusions A cluster of medical students’ characteristics, including paramedical background, rural birthplace, and lower academic rank, was associated with a doctor remaining in Nepal and with working outside the capital city of Kathmandu. Policy makers in medical education who are committed to producing doctors for underserved areas of their country could use this evidence to revise their entrance criteria for medical school.

Introduction

Doctors tend to migrate from medically less well served areas to better served areas. This paradoxical flow occurs over a continuum that includes internal migration (often from rural to urban areas) and external migration (from low income to high income countries). Both result in adverse outcomes for patients in the areas of origin.1 2 In recent policy documents, the World Health Organization and others have issued calls to “build the evidence base” on retention of healthcare workers in underserved areas.3 4 5 6

Existing retention studies, mainly from high income countries, report associations of rural upbringing and male sex with career practice in a rural setting.7 8 9 10 International migration studies likewise usually derive their data from destination (high income) countries, and none has compared the rates of emigration with medical students’ characteristics.11 12 13 14 15 16 17

Nepal is an Asian country with a population of 28 million; its mountainous topography and poverty (annual gross domestic product $300 (£193; €245) per capita) pose barriers to adequate healthcare. According to WHO’s statistics, Nepal ranks near the bottom of countries in the region,18 and like many other nations it struggles with inequitable distribution of its health workers.19 In 1978 Nepal’s Institute of Medicine, which was founded with an ethos of serving the country’s remote population, admitted Nepal’s first class of medical students. Initially, the institute selected students from rural Nepal and admitted only those with a paramedical background. In Nepal, two possible pre-medical tracks exist: “paramedical” education involves three years of training after high school and leads to clinical practice; “intermediate science” involves two years of purely classroom education with no medical exposure. Although it remained Nepal’s sole medical college for 13 years (and was still the country’s premier medical college at the time of this study), the Institute of Medicine gradually shifted away from its original selection system, eventually taking only intermediate science students on the basis of their entrance examination scores.

Certain characteristics of medical students—sex, age at matriculation, rural upbringing, type of pre-medical education, and academic rank—may be associated with doctors choosing to practise in Nepal rather than abroad or in Nepal’s rural areas rather than in the capital city of Kathmandu. To test this hypothesis, we tracked the graduate doctors of the first 22 classes (1983-2004) of the Institute of Medicine to determine their eventual locations of practice. If associations between medical students’ characteristics and career practice location are validated, they could be used to construct admission criteria for medical schools that favour subsequent practice in less well served areas.

Methods

Selection of medical student related factors

To determine which characteristics of medical student predicted location of practice in underserved areas, we analysed seven factors. We chose to study place of birth, place of high school, and sex to test the conclusions of previous studies done in high income countries. We also included type of pre-medical education because of the undocumented observation in Nepal that more doctors from a paramedical background seemed to stay in Nepal. We included year of graduation in the analysis to account for historical trends. Finally, we included final academic score and age at matriculation because these were potential confounders.

Data collection

We did this study in partnership with the Nepal Institute of Medicine’s Dean’s Office, Research Department, and Examination Control Division. We collected data continuously from August 2008 to July 2010 (24 months) in three phases: a review of records at the Institute of Medicine, a written questionnaire from graduates, and reporting by classmates. The study depended on extensive cooperation from the Institute of Medicine and its network of alumni.

We chose to collect data covering the institute’s first to 22nd graduating classes (1983 to 2004), thereby leaving a minimum of four years of post-graduation follow-up. This was to allow for “settling” in a doctor’s practice location. We derived data from three sources.

Institute of Medicine records

The Examination Control Division provided complete lists of the first 22 entering classes of its Bachelor of Medicine Bachelor of Surgery (MBBS) student doctors. Data included class number and graduation year, name, sex, type of pre-medical education, and final examination score.

Questionnaire from graduates

We developed a standardised three page questionnaire and uploaded it for online response. We recruited respondents through newspaper advertisements, the NepalNews internet site, social networks, and personal contacts. If no response came through internet or email, we used phone interviews to complete questionnaires. Questionnaire data included each doctor’s class number, birthplace, place of high school, and pre-medical training (paramedical or intermediate science); spouse’s birthplace; postgraduate work history, current practice location, and postgraduate degrees; perceived personal factors influencing career practice location; and contact information for classmates.

Because after one year we had received filled questionnaires from just over half of all graduates, we added a “mop-up” phase. This final phase, which simultaneously collected questionnaires and took classmates’ reports, required an additional 12 months to complete.

Classmates’ reports

For those doctors who did not complete questionnaires, we used multiple methods to collect “proxy” information from fellow graduates. All questionnaire respondents received a list of non-responders from their class and from the four nearest classes. We also re-contacted questionnaire respondents by phone to ask about classmates. In each class, we interviewed multiple graduates to provide cross validation. Data in this phase included only current practice location.

Participants

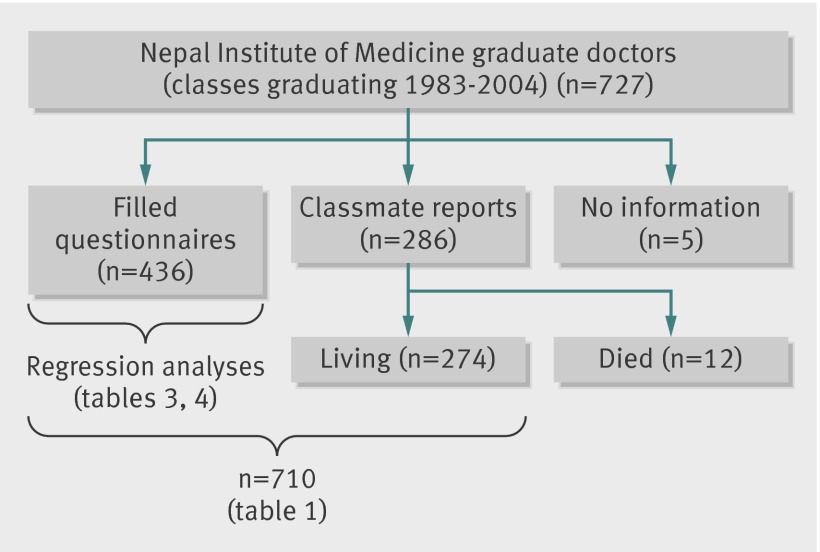

The first 22 classes of Nepal’s Institute of Medicine had 727 graduates. Of this total, we obtained filled data questionnaires from 436 (60.0%), classmates’ reports on an additional 286 (39.3%), and no information on 5 (0.7 %) (fig1). Twelve were reported to have died.

Fig 1 Study participants

Our data contained two subsets. For the 60% (n=436) of graduates who completed questionnaires, we had information on their career location as well as all seven medical student related factors. For the 38% (n=274) of graduates whose career location came from classmates’ reports, we had data for only four of the seven factors (sex, type of pre-medical education, year of graduation, and final examination score). Table 1 shows the compilation of both data subsets, including the characteristics of all 710 graduates. The regression analyses include only those graduates for whom we had data on all seven factors (the “filled questionnaire” subset). We did case-wise deletion for all analyses and made no attempt to impute missing data. All numbers in tables reflect the number of observations with complete data available for analysis.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Institute of Medicine graduates. Values are numbers (row percentages) of doctors in each practice location

| Characteristics | Practice location | Total (n=710) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| District | Kathmandu | Foreign | ||

| Graduation era: | ||||

| 1983-87 (paramedical intake) | 47 (38) | 60 (48) | 17 (14) | 124 |

| 1988-2002 (paramedical + science intake) | 140 (28) | 167 (33) | 193 (37) | 500 |

| 2003-04 (science intake) | 6 (7) | 34 (40) | 46 (53) | 86 |

| Sex: | ||||

| Male | 182 (29) | 230 (37) | 215 (34) | 627 |

| Female | 11 (13) | 31 (37) | 41 (49) | 83 |

| Pre-medical education: | ||||

| Paramedical | 155 (40) | 157 (41) | 71 (19) | 383 |

| Science | 38 (12) | 104 (32) | 185 (57) | 327 |

| Academic class rank: | ||||

| Upper third | 44 (18) | 84 (34) | 121 (49) | 249 |

| Middle third | 70 (29) | 87 (36) | 82 (34) | 239 |

| Lower third | 79 (36) | 90 (41) | 53 (24) | 222 |

| Birthplace: | ||||

| District | 126 (41) | 122 (39) | 61 (20) | 309 |

| Kathmandu | 13 (11) | 67 (55) | 42 (34) | 122 |

| Foreign | 1 (50) | 1 (50) | 0 (0) | 2 |

| Missing data | 53 (19) | 71 (26) | 153 (55) | 277 |

| Place of high school graduation: | ||||

| District | 112 (43) | 104 (40) | 45 (17) | 261 |

| Kathmandu | 21 (14) | 82 (53) | 51 (33) | 154 |

| Foreign | 8 (50) | 3 (19) | 5 (31) | 16 |

| Missing data | 52 (19) | 72 (26) | 155 (56) | 279 |

| Age (years) at medical school matriculation: | ||||

| 16-20 | 11 (11) | 44 (43) | 48 (47) | 103 |

| 21-25 | 63 (37) | 85 (50) | 23 (13) | 171 |

| >25 | 49 (53) | 40 (43) | 4 (4) | 93 |

| Missing data | 70 (20) | 92 (27) | 181 (53) | 343 |

Data analysis

To explore the relation between medical students’ characteristics and doctors’ current location of practice, we did two separate logistic regressions. The first compared doctors who remained in Nepal with those who practised in foreign countries (reference group). The second compared doctors who practised in Nepal’s rural districts with those who practised in Kathmandu (reference group). We report odds ratios for the likelihood of remaining in Nepal and for working in the rural districts for both unadjusted and adjusted models. Fully adjusted models include all the variables in table 1. Because of the small sample size, we excluded respondents whose birthplace or place of high school graduation was outside of Nepal (foreign). We modelled academic class rank as a continuous variable standardised within the graduating class. We also modelled age at matriculation as a continuous variable. We used SAS 9.2 for all analyses.

Results

Practice location

Of 710 living graduates, we found that 193 (27.2%) worked in districts of Nepal outside of Kathmandu, 261 (36.8%) in Kathmandu, and 256 (36.1%) outside of Nepal. Of the 256 graduates working outside Nepal, we received reports on the specific country for all of them: 188 (73%) doctors were working in the United States, 20 (8%) in the United Kingdom, 8 (3%) in Australia, 8 (3%) in South Africa, and 32 (13%) in other countries (table 2).

Table 2.

Foreign country practice location

| Country | No (%) (n=256) |

|---|---|

| United States | 188 (73) |

| United Kingdom | 20 (8) |

| Australia | 8 (3) |

| South Africa | 8 (3) |

| China | 7 (3) |

| Canada | 4 (2) |

| Japan | 4 (2) |

| Bangladesh | 2 (1) |

| India | 2 (1) |

| New Zealand | 2 (1) |

| Sweden | 2 (1) |

| Brunei | 1 (<1) |

| Cambodia | 1 (<1) |

| Holland | 1 (<1) |

| Hong Kong | 1 (<1) |

| Korea | 1 (<1) |

| Maldives | 1 (<1) |

| Myanmar | 1 (<1) |

| Norway | 1 (<1) |

| Sri Lanka | 1 (<1) |

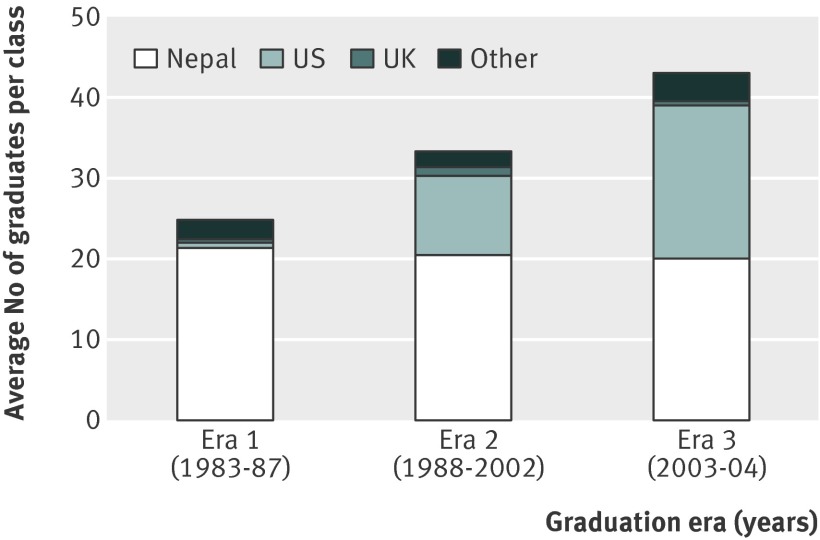

Figure 2 shows the proportion of doctors located in different countries by their era of graduating class. The number of Institute of Medicine graduates going to the United States increased over the period that this study covered, while decreasing numbers went to the UK and to other countries. We noted some “clustering” of graduates within an era: for example, a group of graduates in the early classes went to South Africa, and in later years a group went to China.

Fig 2 Country location by graduation era

Of the 436 graduates who filled in questionnaires, 332 (76%) were in Nepal; of the 274 whose location data came by classmates’ reports, 122 (44%) were in Nepal. That is, full questionnaire data was more readily available for those doctors whom we could contact directly inside the country. Although these two data subsets (filled questionnaire and classmate reported) thus differed in terms of practice location, for the four characteristics of medical students available for all graduates, the odds ratios for the two subsets were similar.

Factors associated with practice location

Over the span of 22 classes, doctors graduating in later years were more likely to practise in foreign countries (53% of era 3 students versus 14% of era 1 students) and less likely to practise in rural Nepal (7% v 38%) (table 1). Male students made up 88.3% of all graduates. Compared with their female classmates, men were twice as likely to remain in Nepal and to work in rural areas.

For the first five classes (era 1), the institute admitted only students with a paramedical background; from the sixth class onwards, intermediate science students were admitted. Compared with those with science background, students with a paramedical background were twice as likely to remain in Nepal and 3.5 times as likely to practise in rural Nepal.

To graduate, students at the institute had to pass an academic examination (written and oral), and this final examination score determined their rank in the class. Compared with students ranked in the top third of their class, those who ranked in the lower third of their classes were twice as likely to remain in rural areas of the country.

Data on birthplace, place of high school, and age at matriculation were available only for the subset of doctors who completed questionnaires. Students with rural birthplace and graduation from rural high school were three to four times as likely to work in rural Nepal, compared with students raised in Kathmandu.

For a contemporaneous comparison between students with paramedical and intermediate science backgrounds, we analysed the subset of graduates from the era 1988 to 2002—the period of mixed intake of the two pre-medical streams. For this period, those with a paramedical background were twice as likely to eventually work in Nepal (79% v 42%) and three times as likely to be in rural Nepal (42% v 13%) compared with those with a science background.

Table 3 gives the odds ratio for doctors remaining in Nepal (versus emigrating to work in a foreign country) for each of the seven medical student related factors. Of 351 graduates included in this analysis, 71 (20%) were working in foreign countries. The unadjusted odds ratios for the subset of doctors who provided complete data were similar to the crude ratios for the four common factors (graduation era, sex, pre-medical education, and final examination score) shown in table 1 (the whole cohort of graduates).

Table 3.

Odds ratio of remaining in Nepal (versus working in foreign countries) (n=351)

| Covariates | Unadjusted | Adjusted | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio (95% CI) | Wald χ2 P value | Odds ratio (95% CI) | Wald χ2 P value | |

| 1. Graduation era: | ||||

| 1983-87 (reference) | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| 1988-2001 | 0.2 (0.1 to 0.5) | <0.001 | 0.5 (0.2 to 1.8) | 0.33 |

| 2002-03 | 0.1 (0.0 to 0.2) | <0.001 | 0.5 (0.1 to 2.4) | 0.42 |

| 2. Sex: | ||||

| Female (reference) | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Male | 2.4 (1.1 to 5.2) | 0.03 | 1.1 (0.4 to 2.9) | 0.82 |

| 3. Pre-medical education: | ||||

| Science (reference) | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Paramedical | 12.0 (6.3 to 22.8) | <0.001 | 4.4 (1.7 to 11.6) | 0.003 |

| 4. Final academic score | 0.6 (0.4 to 0.8) | <0.001 | 0.8 (0.6 to 1.1) | 0.18 |

| 5. Birthplace: | ||||

| Kathmandu (reference) | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| District | 2.0 (1.2 to 3.5) | 0.01 | 0.7 (0.3 to 1.7) | 0.39 |

| 6. Place of high school: | ||||

| Kathmandu (reference) | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| District | 2.6 (1.6 to 4.5) | <0.001 | 1.7 (0.7 to 4.2) | 0.27 |

| 7. Age at matriculation | 1.5 (1.3 to 1.6) | <0.001 | 1.1 (1.0 to 1.3) | 0.09 |

Odds ratios are from logistic model for specified outcome and adjusted for all covariates listed; model No represents case-wise deletion based on all covariates.

When adjusted for each of the other characteristics of medical students, the only factor found to have a significant independent association with retention in Nepal was paramedical background. After adjustment, the odds ratio for paramedical background (versus intermediate science) was 4.4 (95% confidence interval 1.7 to 11.6).

Among those doctors who stayed in Nepal, table 4 gives the odds ratio for working in rural areas (versus in Kathmandu). Without adjustment, all of the factors except sex were associated with working in rural Nepal. The unadjusted odds ratios were again similar to the crude ratios for these same factors in table 1 (the total sample). When adjusted for each of the other characteristics, the two factors found to have a significant independent association with rural retention were rural birthplace (odds ratio 3.8, 1.3 to 11.5) and older age at matriculation (1.1, 1.0 to 1.2).

Table 4.

Odds ratio of working in rural Nepal (versus Kathmandu) (n=280)

| Covariates | Unadjusted | Adjusted | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio (95% CI) | Wald χ2 P value | Odds ratio (95% CI) | Wald χ2 P value | |

| 1. Graduation era: | ||||

| 1983-87 (reference) | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| 1988-2001 | 1.3 (0.8 to 2.2) | 0.32 | 1.6 (0.9 to 2.8) | 0.14 |

| 2002-03 | 0.3 (0.1 to 1.0) | 0.04 | 0.9 (0.2 to 4.0) | 0.91 |

| 2. Sex: | ||||

| Female (reference) | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Male | 2.2 (0.8 to 6.2) | 0.14 | 0.8 (0.2 to 2.6) | 0.67 |

| 3. Pre-medical education: | ||||

| Science (reference) | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Paramedical | 2.8 (1.5 to 5.2) | <0.001 | 1.2 (0.5 to 3.0) | 0.66 |

| 4. Final academic score | 0.8 (0.6 to 1.0) | 0.10 | 0.9 (0.7 to 1.2) | 0.57 |

| 5. Birthplace: | ||||

| Kathmandu (reference) | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| District | 7.1 (3.2 to 15.5) | <0.001 | 3.8 (1.3 to 11.5) | 0.02 |

| 6. Place of high school: | ||||

| Kathmandu (reference) | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| District | 4.9 (2.6 to 9.2) | <0.001 | 1.7 (0.7 to 4.2) | 0.29 |

| 7. Age at matriculation | 1.2 (1.1 to 1.3) | <0.001 | 1.1 (1.0 to 1.2) | 0.02 |

Odds ratios are from logistic model for specified outcome and adjusted for all covariates listed; model No represents case-wise deletion based on all covariates.

Discussion

We tracked graduates of Nepal’s first medical college, the Institute of Medicine, to their current locations of practice. Diverse modes of communication applied over a two year period, a tight knit alumni network, and the cooperation of the college authorities enabled us to locate 98% of the doctors 4-26 years after their graduation. They were approximately distributed in thirds: located in Nepal’s rural districts, in the capital Kathmandu, or in foreign countries. The institute’s changing admission policy over the decades provided an internal comparison to study the effects of different intake criteria for medical students on the eventual practice location of graduates. We found an association between rural birthplace, paramedical pre-medical education, lower academic rank, male sex, and older age at matriculation and eventually working in a relatively underserved area.

The WHO’s and other recent reviews on international and internal migration of health workers highlight the paucity of evidence, particularly for low income countries and with regard to potential interventions.3 4 5 6 20 Most studies on international migration use databases from destination (high income) countries rather than indexing from source countries.11 12 14 Dovlo studied Ghanaian medical students and found that 9.5 years after graduation, 75% had left their home country.13 Two South African studies located doctors by their postal addresses, and one found that rural service was associated with rural birthplace.9 21 Others mentioned successful retention among graduates of certain medical colleges in low income countries, but evidence was not presented.22 23 24

Across the Institute of Medicine’s first 22 classes (1983-2004), graduates from later years were more likely to work abroad or, if they stayed in Nepal, to work in Kathmandu. It is tempting to relate their foreign migration to the increased availability of postgraduate training posts in the United States or to Nepal’s civil war (1996-2006). However, in our study, location of practice was not independently associated with a student’s era of graduation but was linked to several other factors.

High income countries have documented the association of rural upbringing with doctors’ eventual rural practice, although in those cohorts selection of students on the basis of rural background was usually part of a mixed intervention that included scholarships and career practice incentives.7 8 25 26 A review study found that male sex was also associated with rural practice of doctors.27

In Nepal, we collected data on factors that could be evaluated at the time of medical school attendance: age at matriculation, sex, places of birth and high school, type of pre-medical education, and final academic score/class rank. The data on rural background and matriculation age were available only for the 60% of the graduates who completed questionnaires; data on the other four factors were available for 98% of the institute’s graduates.

Our study validated the independent association of rural birthplace with the eventual rural practice of the doctor. Compared with other studies, in Nepal this association was not complicated by overlaid incentives for rural practice: few such programmes existed in the country over the previous decades. Students who have spent all or part of their childhood in a rural setting may feel more at home in a remote medical practice. Selecting students with this background does not guarantee eventual rural practice, but it seems to increase the likelihood.

The Institute of Medicine began by admitting only students with a paramedical background (usually health assistants) whose pre-medical training and work experience were in clinical medicine; it later also admitted pre-medical science students. We found a significant, independent association between students from a paramedical background and doctors remaining to work in Nepal. In other words, the alternative pre-medical track of intermediate science made it more likely that an admitted student would eventually establish a practice abroad. This association was independent of historical era and persisted for the years (1988-2002) when students from both types of background were admitted into the same classes.

Paramedical students’ previous experience of working in rural healthcare institutions may have encouraged them to choose to work (and stay) in underserved areas after they became doctors. Vietnam and China have medical school programmes that enable paramedical intake.3 Although Nepal’s Institute of Medicine did not use any “catch-up” academic programmes, others have reported successful bridging programmes that bring students from alternative pathways up to an acceptable academic standard.24 28

WHO categorised interventions to redress inequitable distribution of doctors into four areas: education, regulation, financial incentives, and personal support.3 Our study focused on factors that could be targeted at the time of selection for medical school (the education phase).

Although each of the six medical student related factors in our study—along with earlier era of graduation—was associated with practice either in Nepal or in its rural areas, the multivariable analyses showed that these were mostly clustered, rather than isolated, factors. For example, a common profile of a paramedical student included rural upbringing, later entry into medical school, and lower academic rank. One could interpret this as being a student with broader practical experience but not necessarily the highest academic prowess or ability to take tests. The experience of the Institute of Medicine would argue that this did not promote mediocrity in medical practice: rather, over the decades, both the institute’s paramedical graduates and its science graduates have a solid track record in a wide range of practice settings.29 Furthermore, we found that higher academic rank in the class was not independently associated with foreign migration but was clustered with other factors. Selection for medical school based less on entrance examination scores and more on non-academic factors could produce a graduating class of doctors more likely to serve the wider, local population, without forfeiting professional excellence.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. Firstly, for our regression analyses, we used the data from the 60% of graduates who provided full information on questionnaires. Because that group was somewhat more likely to be in Nepal at the time of our study, they may not fully represent the whole population of graduates. Nevertheless, for the students’ characteristics that we measured, the crude ratios of the full cohort were very similar to the odds ratios of the questionnaire subset.

Secondly, as a measure of academic ability, we had access to final academic examination scores. Entrance examination scores would have been more relevant to selection criteria for medical school.

Thirdly, we placed doctors into three categories of location of practice: Nepal districts, Kathmandu, and foreign. Because Nepal has other cities, the first category is not purely “rural.” However, a distinct drop-off in medical service and living conditions occurs on leaving the city of Kathmandu.

Finally, we located doctors only at one point in time. This left open the possibility that doctors were still in transit when we located them or that they had worked in several sectors over their career. We tried to minimise this source of error by leaving a minimum of four years’ lead time from graduation to our study contact time. Our experience is that most Nepalese doctors do not move to and from overseas locations after a period of settling.

Application of findings

The findings of our retrospective study in one low income country in Asia need to be validated in others settings, perhaps through interventions in selection for medical school. Policy makers in medical education who are committed to producing doctors for underserved populations could consider adjusting their selection of students. An intake process that gives higher emphasis to rural birthplace, rural high school, and paramedical education—while using an academic minimum cut-off criterion, rather than entrance scores—may result in more of the graduating class “staying home.”

What is already known on this topic

Migration of doctors from low income to high income countries and from rural to urban areas is extensive

In high income countries, doctors with rural backgrounds are more likely to work in rural locations of their own countries

What this study adds

For Nepalese graduate doctors, an association existed between rural birthplace, paramedical pre-medical education, lower academic rank, male sex, and older age at matriculation and eventually working in a relatively underserved area

Policy makers in medical education who are committed to producing doctors for underserved areas of their country could use this evidence to revise entrance criteria for medical school

We acknowledge the contributions of Robert Gerzoff, who did the statistical analysis of the data. We also acknowledge Dikshya Adhikari for recruitment of participants and Arjun Karki for the conceptual challenge.

Contributors: MZ and BMP were involved in the conception and design of the study; data collection, analysis, and interpretation; and writing the paper. RS was involved in study conception and design and in data collection, analysis, and interpretation. NE was involved in study design, data analysis and interpretation, and writing the paper. BPR and RNS were involved in study conception and in data collection and interpretation. AS was involved in study conception and design and in data interpretation. MZ is the guarantor.

Funding: Funding came entirely from the Nick Simons Institute, a charitable organisation that works to train and support healthcare workers for rural Nepal (www.ndi.edu.np). Neither the Nick Simons Institute nor the authors stands to receive material gain from the publication of this study. The Nick Simons Institute carried out this study as part of its mission to train and support healthcare workers for rural Nepal. It will use the study results to lobby for changes in medical education policy, in Nepal and internationally.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: the submitted work was supported by the Nick Simons Institute; BMP, BPR, RNS, and AS are all on the faculty of the Institute of Medicine; AS is the Dean; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: The Institute of Medicine (Nepal) Research Committee, which functions as that institution’s ethics review board, approved this study in July 2008. The Research Committee also approved the “mop-up phase” and use of data from non-responding doctors.

Data sharing: The spreadsheet containing the data for this study can be downloaded from ftp://nsi.edu.np (user name: iom_data@nsi.edu.np; password: admin123).

Cite this as: BMJ 2012;345:e4826

References

- 1.Joint Learning Initiative. Human resources for health: overcoming the crisis. Harvard College, 2004 (available at www.healthgap.org/camp/hcw_docs/JLi_Human_Resources_for_Health.pdf).

- 2.Speybroeck N, Kinfu Y, Dal Poz MR, Evans DB. Reassessing the relationship between human resources for health, intervention coverage and health outcomes. World Health Organization, 2006 (available at www.who.int/hrh/documents/reassessing_relationship.pdf).

- 3.World Health Organization. Increasing access to health workers in remote and rural areas through improved retention: global policy recommendations. WHO, 2010 (available at http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2010/9789241564014_eng.pdf). [PubMed]

- 4.World Health Organization. Global code of practice on the international recruitment of health personnel. (Sixty Third World Health Assembly WHA63.16 Agenda item 11.5 21 May 2010.) WHO, 2010 (available at http://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA63/A63_R16-en.pdf).

- 5.Grobler L, Marais BJ, Mabunda S, Marindi P, Reuter H, Volmink J. Interventions for increasing the proportion of health professionals practicing in rural and other underserved areas. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009;(1):CD005314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilson NW, Couper ID, De Vries E, Reid S, Fish T, Marais BJ. A critical review of interventions to redress the inequitable distribution of healthcare professionals to rural and remote areas. Rural Remote Health 2009;9:1060. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rabinowitz HK, Diamond JJ, Markham FW, Rabinowitz C. Long-term retention of graduates from a program to increase the supply of rural family physicians. Acad Med 2005;80:728-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matsumoto M, Inoue K, Kajii E. Long-term effect of the home prefecture recruiting scheme of Jichi Medical University, Japan. Rural Remote Health 2008;8:930. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Vries E, Reid S. Do South African medical students of rural origin return to rural practice? S Afr Med J 2003;93:789-93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Woloschuk W, Tarrant M. Do students from rural backgrounds engage in rural family practice more than their urban-raised peers? Med Educ 2004;38:259-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mullan F. The metrics of the physician brain drain. N Engl J Med 2005;353:1810-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hagopian A, Thompson MJ, Fordyce M, Johnson KE, Hart LG. The migration of physicians from sub-Saharan Africa to the United States of America: measures of the African brain drain. Hum Resour Health 2004;2:17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dovlo D, Nyonator F. Migration by graduates of the University of Ghana Medical School: a preliminary rapid appraisal. Human Resources for Health Development Journal 1999;3(1):40. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clemens MA, Pettersson G. New data on African health professionals abroad. Hum Res Health 2008;6:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Awofeso N. Improving health workforce recruitment and retention in rural and remote regions of Nigeria. Rural Remote Health 2010;10:1319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Akl EA, Maroun N, Major S, Chahoud B, Schunemann HJ. Graduates of Lebanese medical schools in the United States: an observational study of international migration of physicians. BMC Health Serv Res 2007;7:49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Adkoli BV. Migration of health workers: perspectives from Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka. Reg Health Forum 2006;10:49-58. [Google Scholar]

- 18.World Health Organization. World health statistics 2011. www.who.int/gho/publications/world_health_statistics/2011/en/index.html.

- 19.Nepal Ministry of Health and Population. Nepal Health Sector Programme—implementation plan II, 2010-15. Government of Nepal, 2010.

- 20.Dieleman M, Kane S, Zwanikken P, Gerretsen B. Realist review and synthesis of retention studies for health workers in rural and remote areas. WHO, 2011 (available at http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2011/9789241501262_eng.pdf).

- 21.Igumbor EU, Kwizera EN. The positive impact of rural medical schools on rural intern choices. Rural Remote Health 2005;5:417. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Christobal F, Worley P. Can medical education in poor rural areas be cost-effective and sustainable: the case of the Ateneo de Zamboanga University School of Medicine. Rural Remote Health 2012;12:1835. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huish R. Going where no doctor has gone before: the role of Cuba’s Latin American School of Medicine in meeting the needs of some of the world’s most vulnerable populations. Public Health 2008;122:552-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iputo JE. Faculty of Health Sciences, Walter Sisulu University: training doctors from and for rural South African communities. MEDICC Review Fall 2008;10(4):25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eley D, Baker P. Does recruitment lead to retention? Rural clinical school training experiences and subsequent intern choices. Rural Remote Health 2006;6:511. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Walker JH, Dewitt DE, Pallant JF, Cunningham CE. Rural origin plus a rural clinical school placement is a significant predictor of medical students’ intentions to practice rurally: a multi-university study. Rural Remote Health 2012;12:1908. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laven G, Wilkinson D. Rural doctors and rural backgrounds: how strong is the evidence? A systematic review. Aust J Rural Health 2003;11:277-284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Polasek O, Kolcic I. Academic performance and scientific involvement of final year medical students coming from urban and rural backgrounds. Rural Remote Health 2006;6:530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dixit H. Nepal’s quest for health. Educational Publishing House, 2005.