Abstract

This study examined the role of parent depressive symptoms as a mediator of change in behaviorally observed positive and negative parenting in a preventive intervention program. The purpose of the program was to prevent child problem behaviors in families with a parent who has current or a history of major depressive disorder. One hundred and eighty parents and one of their 9-to-15-year old children served as participants and were randomly assigned to a family group cognitive-behavioral (FGCB) intervention or a written information (WI) comparison condition. At two months after baseline, parents in the FGCB condition had fewer depressive symptoms than those in the WI condition and these symptoms served as a mediator for changes in negative, but not positive, parenting at 6 months after baseline. The findings indicate that parent depressive symptoms are important to consider in family interventions with a parent who has current or a history of depression.

Keywords: Parent depression, positive parenting, negative parenting, prevention

Approximately 15 million children in the United States grow up in a household where a parent has experienced one or more episodes of a major depressive disorder (England & Sim, 2009). These children are at an increased risk of developing internalizing and externalizing disorders and symptoms (for reviews, see England & Sim, 2009; Goodman, Rouse, Connell, Broth, Hall, & Heyward, 2011). One of the primary mechanisms for the transmission of risk for psychopathology in these families is parenting (for reviews, see Compas, Keller, & Forehand, 2011; Goodman & Gotlib, 1999; Goodman & Tully, 2006). Of importance, recent preventive intervention research indicates that the parenting of parents with a history of depression can be changed which, in turn, may result in a change in child emotional and behavioral problems (Compas et al., 2010).

The purpose of the current study is to examine the role parent depressive symptoms play in positive and negative parenting within the context of a preventive intervention program for families with current or a history of depression (Compas et al., 2009, 2011). The family group cognitive-behavioral (FGCB) program is designed to prevent problem behaviors of 9- to 15-year-old children living in these families. Although identification of depressive symptoms and understanding of their causes and consequences are part of the program, the focus is not on reducing parental depressive symptoms. Instead, the program focuses on teaching parenting skills based on procedures utilized in behavioral parent training (e.g., praise for appropriate behavior, discipline for inappropriate behavior, monitoring) (e.g., Kazdin, 2010; McMahon & Forehand, 2003) and skills for child coping with stress (e.g., engaging in fun activities and positive thinking).

Our research has demonstrated that, relative to a comparison condition [Written Information (WI)], the preventive intervention program decreases child problem behaviors at 12-month, 18-month, and, for some outcomes, 24-month follow-ups (Compas et al., 2009, 2011). Furthermore, parenting at 6 months post-intervention has been shown to be a mediator of the intervention effects on child problem behaviors at the 12-month follow-up (Compas et al., 2010). The analyses reported in the current study were designed to further our understanding of the role of parent depressive symptoms in change in parenting behavior resulting from the preventive intervention with a larger sample and accompanying increased statistical power than our earlier studies.

In a meta-analytic review of observational studies examining the association of depressive symptoms and parenting, Lovejoy, Graczyk, O’Hare, and Neuman (2000) found strong support for the relationship between parental depressive symptoms and negative parenting (e.g., threatening gestures, expressed anger, intrusiveness). In contrast, the association between parental depressive symptoms and positive parenting (e.g., praise, affectionate contact, play) was “relatively weak” (Lovejoy et al., p. 561). More recently, Dix and Meunier (2009) have examined 13 potential processes that could account for the association between parental depressive symptoms and parenting. Although only weak indirect support was found for many of the processes, some direct support for one of the hypotheses suggests why depressive symptoms may relate to negative parenting: Depressive symptoms promote negative appraisals of a child which, in turn, lead to negative verbal and physical behavior with the child.

When studies that focus on changing parental behavior of non-depressed parents to prevent or remediate child problem behavior are examined, not only do targeted positive and negative parenting behaviors change with intervention but so do non-targeted parental depressive symptoms (e.g., Forehand, Wells, & Griest, 1980; Kazdin & Wassell, 2000; McGilloway et al., 2012; Shaw, Connell, Dishion, Wilson, & Gardner, 2009). Two potential explanations exist for these findings: Changes in parenting lead to the alleviation of parental depressive symptoms; and changes in parental depressive symptoms lead to improved parenting. Although both explanations are plausible, our focus in the current study, consistent with hypotheses offered in the parent depression literature (Gunlicks & Weissman, 2008), is on the latter explanation. Three studies suggest some support for reductions in parental depressive symptoms leading to changes in parenting.

In an intervention study conducted with mothers who were clinically depressed and treated with medication, Foster et al. (2008) found remission of maternal depressive symptoms was associated with improved child reported positive parenting. As maternal depressive symptoms and parenting were collected concurrently at a 3-month follow-up, conclusions about the causal role of depressive symptoms in parenting are limited. In a study with mothers who were clinically depressed and treated with cognitive-behavioral procedures and/or medication, Garber, Ciesla, McCauley, Diamond, and Schloredt (2011) found that, relative to non-remission of maternal depression, remission was associated with higher levels of child reported parenting on one of three measures (e.g., acceptance but not monitoring or psychological control). In a prevention study conducted with recently separated mothers and their sons, Patterson, DeGarmo, and Forgatch (2004) found that a reduction in maternal depressive symptoms following a parenting intervention (e.g., positive involvement with child, appropriate discipline, monitoring) was associated with subsequent improvement in behaviorally observed effective parenting. The construct of effective parenting included behaviors that involved both positive (e.g., positive involvement, skill encouragement) and negative (e.g., inept discipline, negative reinforcement) parenting.

The current study extends the Foster et al. (2008) study by examining change in parent depressive symptoms resulting from a preventive intervention in families with a parent with current or a history of depression and the role of this change in subsequent behaviorally observed parenting. By examining parenting at a subsequent point in time, conclusions can be reached that are more consistent with causal interpretations of the data. The current study extends the Garber et al. (2011) study by examining behaviorally observed negative parenting (e.g., hostility, intrusiveness) and the Patterson et al. (2004) study by considering positive and negative parenting separately rather than as a combined construct. Lovejoy et al.’s (2000) conclusion that parent depressive symptoms are differentially related to these two types of parenting suggests different findings may emerge for positive and negative parenting. Finally, we extended the prior studies by formally examining parent depressive symptoms as a mediator by using procedures recommended by MacKinnon et al. (2002) and Kraemer et al. (2002) and as used in our research (Compas et al., 2010) with children living in families with a parent who has current or a history of depression.

First, we hypothesized that, relative to parents in a comparison condition (provision of written information: WI), those in the family group cognitive-behavioral (FGCB) intervention, which included a major parenting component, would demonstrate higher levels of positive parenting and lower levels of negative parenting at a 6-month assessment after controlling for their baseline levels of parenting. Our prior research indicated that positive, but not negative, parenting differed between the two groups at the 6-month assessment (Compas et al., 2010); however, the means and F value for negative parenting suggested that, with more power, a significant difference may emerge. In the current study we included a larger sample to address the power issue. Second, based on the conclusion from the parenting intervention literature that teaching parents parenting skills results in decreases in depressive symptoms (e.g., Forehand et al., 1980; Kazdin & Wassell, 2000; McGilloway et al., 2012; Shaw et al., 2009), we hypothesized that, although depressive symptoms were not the focus of the intervention, parents in the FGCB intervention would have lower depressive symptoms than those in the WI comparison group at the 2-month assessment after controlling for baseline levels of depressive symptoms. Third, based on Lovejoy et al.’s (2000) conclusion about the strong association of parent depressive symptoms and negative parenting, we expected that the change in parental depressive symptoms at 2-months would mediate the effects of intervention on negative parenting at 6-months, controlling for baseline levels of this type of parenting. In contrast, based on Lovejoy et al.’s conclusions about the weak association of parental depressive symptoms and positive parenting, we expected change in the parent depressive symptoms at 2-months would not mediate positive parenting at 6-months, controlling for baseline levels of this type of parenting. Instead, we hypothesized that our intervention would have a direct effect on positive parenting.

Method

Participants

Participants included 180 parents with current or past major depressive disorder during the lifetime of their child(ren) and one of the children of these parents from the areas in and surrounding Nashville, Tennessee and Burlington, Vermont. This sample includes the 111 families that comprised the sample reported in Compas et al. (2009, 2010, 2011) plus 69 families who enrolled after the original 111 families. For families with multiple children in the target age range, one child was randomly selected for the current analyses (see below), yielding a sample of 180 children.

Target parents with a positive history of depression included 160 mothers (mean age of 41.16, SD = 7.17) and 20 fathers (mean age = 48.30, SD = 7.50). Parents’ level of education included less than high school (6%), completion of high school (9%), some college (30%), college degree (32%), and graduate education (23%). Eighty-two percent of target parents were Euro-American, 12% African-American, 2% Hispanic-American, 1% Asian-American, 1% Native American, and 2% mixed ethnicity. The racial and ethnic compositions of the samples were representative of the regions in Tennessee and Vermont from which they were drawn based on the 2000 U.S. Census data. Annual family income ranged from less than $5,000 to more than $180,000, with a median annual income between $40,000-60,000. Sixty-two percent of parents were married/partnered, 22% were divorced, 5% separated, 10% had never married, and 1% were widowed.

Children enrolled in the study and included in the current analyses ranged from 9- to 15-years-old and included 89 girls (mean age = 11.66, SD = 1.92) and 91 boys (mean age = 11.26, SD = 2.07). Seventy-four percent of children were Euro-American, 13% African-American, 3% Asian American, 2% Hispanic American, 1% Native American, and 7% mixed ethnicity. We targeted ages 9 to 15-years-old in order to intervene with children/adolescents before the documented increase in rates of depression that occurs in early to mid-adolescence (e.g., Hankin et al., 1998) and to include children who were old enough to learn the relatively complex cognitive coping skills taught in the intervention.

Forty-eight parents (27%) were in a current episode of major depression and 132 parents (73%) were not in episode at the time of the baseline assessment and randomization. At baseline, 152 (84%) parents reported experiencing multiple episodes of depression during their child’s life and 27 (15%) reported experiencing only a single episode during their child’s life (one parent did not provide enough information to determine chronicity of depression history).

Families randomized to the family group cognitive-behavioral (FGCB) intervention and to the written information (WI) comparison condition did not differ on any demographic variables. Furthermore, families in the original sample of 111 families (Compas et al., 2009, 2010) and the additional 69 families did not differ on any of these variables.

Setting and Personnel

All study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Boards at Vanderbilt University and the University of Vermont. All assessments and group intervention sessions were conducted in the Department of Psychology and Human Development at Vanderbilt University and the Psychology Department at the University of Vermont. Doctoral candidates in clinical psychology and staff research assistants, who were naive to condition, conducted the structured diagnostic interviews after receiving extensive training. Each group intervention was co-facilitated by one of three clinical social workers and one of nine doctoral-level students in clinical psychology. Facilitators were trained by reading the intervention manual, listening to audiotapes of a pilot intervention, and discussing and role-playing each session with an experienced facilitator. Ongoing supervision was conducted by two Ph.D. clinical psychologists.

Measures

Mediator

Parental depressive symptoms

Parents’ current depressive symptoms were assessed at baseline and two months with the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II), a standardized and widely used self-report checklist of depressive symptoms with adequate internal consistency (α = .91) and validity in distinguishing severity of MDD (Beck et al., 1996; Steer, Brown, Beck & Sanderson, 2001). Internal consistency in the current sample was α = .93 at baseline and .94 at 2-months.

Outcome Measures

Observations of parenting

A global coding system, the Iowa Family Interaction Rating Scales (IFIRS; Melby, Conger et al., 1998), was used to code two videotaped 15-minute conversations for each parent-child dyad, first about a pleasant activity that the target parent and child enjoyed doing together in the past couple of months, and second about a stressful time when the target parent was really depressed, down, or grouchy, which made it difficult for the family. The conversations were videotaped at baseline and 6 months. The IFIRS is a global coding system designed to measure behavioral and emotional characteristics at both the individual and dyadic level. Behaviors are coded on a 9-point scale. In determining the score for each code, frequency and intensity of behavior, as well as the contextual and affective nature of the behavior, are considered. The validity of the IFIRS system has been established using correlational and confirmatory factor analyses (Aldefer et al., 2008; Melby & Conger, 2001).

Training is described in Compas et al. (2010). Raters remained naive to the randomization of families to the FGCB intervention vs. the WI condition. All interactions were double-coded by two independent observers and coders met to establish consensus on any discrepant codes (i.e., codes that were rated greater than 2 points apart on the 9-point scales).

Following procedures used previously with the IFIRS codes (e.g., Lim et al., 2008; Melby et al., 1998), scores were averaged across the two 15-minute interactions and then composite codes were created for positive and negative parenting that reflected the parenting skills that were taught in the FGCB intervention which were based on theory-driven and empirically-supported disruptions in parenting related to depression as well as establishing authoritative parenting skills (i.e., balance of warmth and structure). The positive parenting composite included parents’ warmth, child-centered behaviors, positive reinforcement, quality time, listener responsiveness, and child monitoring (α = .81 at baseline and .85 at 6-months). The negative parenting composite included parental negative affect (sadness and positive mood, reverse scored), hostility, intrusiveness, neglect/distancing, and externalize negative (α = .70 at baseline and .73 at 6-months).

Procedures

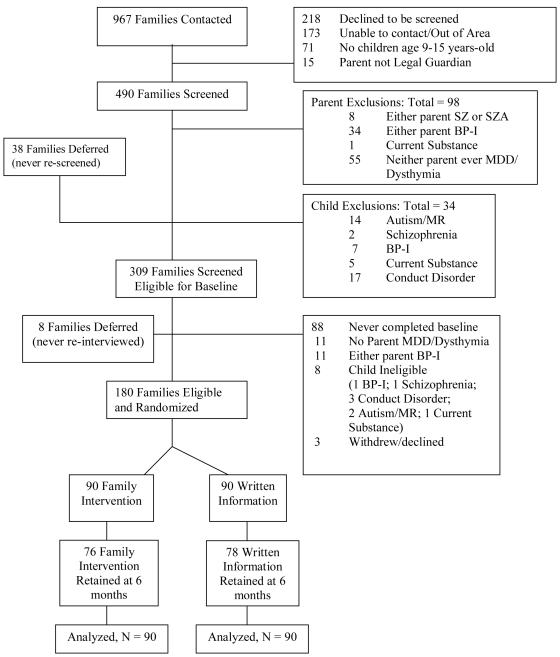

To enroll a broadly representative sample of parents with current or a history of major depressive disorder, we recruited the sample from several sources, including mental health clinics/practices, family and general medical practices, and media outlets. As shown in Figure 1, a total of 967 parents contacted the research teams. Of these, 490 were eligible and available to be screened. The parents were initially screened by telephone and moved to the next stage if the parent met criteria for major depression either currently or during the lifetime of her/his child(ren) and if the following criteria were met: (a) parent had no history of bipolar I, schizophrenia, or schizoaffective disorders; (b) children had no history of autism spectrum disorders, mental retardation, bipolar I disorder, or schizophrenia disorder; and (c) children did not currently meet criteria for conduct disorder or substance/alcohol abuse or dependence. One hundred and eighty families were eligible and were randomized.

Figure 1.

Participant screening and randomization. SZ = schizophrenia; SZA = schizoaffective; BP-I = bipolar I; MDD = major depressive disorder; MR = mental retardation

Measures of parent depressive symptoms and observations of parenting occurred at baseline prior to families being randomly assigned to one of two interventions (see below). Ninety (50%) families were assigned to FGCB and 90 (50%) families were assigned to WI. To model change in the mediator, parent depressive symptoms were assessed again at 2 months (after completion of 8 sessions, the acute phase of the intervention). To model change in outcomes, observations of parenting were conducted at 6 months (after booster sessions). Observations of parenting were not conducted at 2 months because of the expense of the collection and coding of the data. The parent and child were each compensated $40 for an assessment involving an interview, questionnaire completion, and behavioral observation.

Retention rates

Through the 6-month assessment, 86% of the families were retained in the study (see Figure 1), as defined by the provision of data at the 2- or 6-month data collection point. There were no significant differences on demographic or major study variables between retained and non-retained participants. Retention percentages between the two groups did not differ: 85% of families assigned to the intervention and 87% of the comparison group were retained.

Intervention and Comparison Conditions

Family group intervention

The family group cognitive-behavioral (FGCB) intervention is a manualized 12-session program for up to 4 families in each group (Compas et al., 2009). The 12-session program consisted of 8 weekly sessions (followed by the 2-month assessment) and 4 monthly sessions (followed by the 6-month assessment). The program is designed for participation by both parents and all children in the 9-15 year old age range. The purpose of the intervention is to prevent the development of internalizing and externalizing problems of children living in these families. The specific goals are to educate families about depressive disorders, increase family awareness of the impact of stress and depression on functioning, help families recognize and monitor stress (i.e., recognize and monitor behavioral, physical, emotional, and cognitive responses to stress), facilitate the development of adaptive coping responses to stress, (e.g., engage in pleasant activities and positive thinking), and improve parenting skills. Two points are of relevance to this study. First, parents learned the following parenting skills: praise, positive time with children, encouragement of child use of coping skills, structure, and consequences for positive and problematic child behavior. (see Compas et al., 2009, for more details on the intervention, including evaluation of treatment integrity). Second, changing parent depressive symptoms was not the focus of the preventive intervention; however, material on the causes and consequences of these symptoms was included.

Written information condition

The Written Information (WI) comparison condition was modeled after a self-study program used successfully by Wolchik et al. (2000) in their preventive intervention trial for families coping with parental divorce and the lecture information condition used by Beardslee et al. (2007). The WI condition provided families with a minimum level of intervention, providing a more rigorous comparison than a wait-list control. Families were mailed three separate sets of written materials to provide education about the nature of depression, the effects of parental depression on families, and signs of depression in children over the 8 weeks corresponding to the weekly sessions of the FGCB. Material was not mailed to the WI participants over the 4 months corresponding to the monthly sessions of the FGCB (see Compas et al., 2009, for more details).

Data Analytic Approach

Analyses of mediation: Multivariate mixed-effects model

In this section we describe an abbreviated version of the procedures we utilized in Compas et al. (2010) and in this investigation to test mediation. The reader is referred to Compas et al. for a more detailed description.

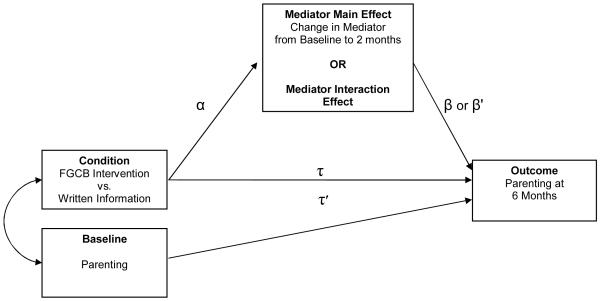

As depicted in Figure 2, MacKinnon et al. (2002) propose that evidence for mediation is found by examining the joint significance of the path from the intervention to the mediator (α) and the path from the mediator to the outcome (β or β’) after accounting for the effects of the intervention. Kraemer et al. (2002) propose that evidence for mediation of an intervention requires random assignment to an intervention and a comparison condition, a significant association between the intervention and change in the mediator (α), and either a significant main effect of change in the mediator on change in the outcome (β) or a significant effect of the interaction between the intervention and change in the mediator on change in the outcome (β’). Further, MacKinnon et al. (2002) and Kraemer et al. (2002, 2008) argue that to establish mediation one must assess for change in the mediator prior to and independent of change in outcome. In prevention research, mediation can be tested by measuring the mediator after completion of the acute phase of the intervention program (i.e., after 8 weeks in FGCB), measuring the outcome variable subsequently (i.e., 6 months after baseline), and controlling for baseline levels for the proposed mediator and the outcome variable. Therefore, in our mediation analyses we calculated a change score from baseline for the mediator variable (at 2-months in the present study), and measured the outcomes at a later assessment (at 6-months in the present study), covarying for the baseline level of the outcome variable.

Figure 2.

Heuristic model of mediation pathways of treatment effects on parenting. The direct effect of intervention on the outcome is depicted by τ and the indirect effect (after controlling for the mediator) is depicted by τ’.

A mixed-effects model was used to test the effects of the intervention on the mediator (α path) and to test the effects of change in the mediator on change in the outcomes (β and β’ paths) (see Figure 2). Most statistical approaches assume that subjects are independent of one another. In the study of interventions delivered in a group format, however, participants assigned to the intervention condition are nested within group. Participants in the same intervention group communicate with each other and may be treated more similarly to each other compared with participants in different treatment groups. Such inevitable processes jeopardize the assumption of statistical independence. Baldwin, Murray, and Shadish (2005) highlighted the need to account for the within-group dependency that likely exists in studies of group-administered interventions, noting that failure to do so can substantially affect Type I error rates. Typical approaches involve participants nested within group in both the intervention condition and the comparison condition. The current design is more complicated, however, in that participants are nested within group only in the intervention condition; there is no such nesting in the comparison condition. As a consequence, we used a mixed-effects model developed for the analysis of treatment effects in the context of partially nested designs (Bauer, Sterba, & Hallfors, 2008). This approach accounts for participants being nested within group only in the intervention condition.

We used the same approach we previously used to test for the effects of the intervention on the outcome measures (Compas et al., 2009, 2011) and mediation of these outcomes (Compas et al., 2010). Specifically, using SAS PROC MIXED with restricted maximum likelihood estimation (i.e., method = REML), we implemented a multivariate, mixed-effects model to test the effect of intervention condition (FGCB vs. Written Information) at 2-month assessment on the mediator. All participants were retained in the data analysis (i.e., intent-to-treat analyses were conducted), including those with partial data. We treated our time 1 (baseline) measure of the outcome as a global covariate. Within the FGCB intervention arm of the study, each set of participants was nested within one of the 23 FGCB intervention cohorts comprised of up to four families per cohort. Within the Written Information comparison arm, there was no such nesting. Fixed effects included our baseline and 2-month intercepts. Intervention (condition) was a random effect at baseline and 2-months, which allowed intervention means at each time point to vary across intervention condition. This amounted to estimating a between-groups random effect variance for intervention at each time point and estimating a within-group residual variance. For information on how the FGCB intervention condition was coded to test for mediation while accounting for partial nesting and for the calculation of dfs across analyses, see Compas et al. (2010).

The effect size for a mediator was calculated by computing a proportion of the effect of the intervention that was accounted for by the mediator.1 The numerator consisted of the difference between the direct effect of the intervention on outcome and the indirect effect of the intervention on outcome after controlling for effects of covariates. The denominator consisted of the direct effect of intervention on the outcome. The proportion-based method of calculating effect size is based on approaches presented by both Shrout and Bolger (2002) and MacKinnon, Fairchild, and Fritz (2007) as a recommended procedure for estimating the effect size of mediation. However, it is important to note that effect size measures for mediation are in their infancy (McKinnon et al.). Although other methods of computing effect sizes are reported in the literature (e.g., Fairchild, MacKinnon, Taborga, & Taylor, 2009), these methods are not appropriate for the current study’s multilevel model with a hierarchical structure that does not use ordinary least squares estimation. We also report the unstandardized estimate (B) and standardized error for the effect of the intervention on the outcome without the mediator and in the presence of the mediator.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Means and standard deviations of the hypothesized mediator at baseline and 2-months and observed parenting at baseline and 6-months are presented in Table 1. Consistent with the expected effects of randomization, there were no significant differences between the FGCB intervention and the Written Information comparison condition at baseline. Parents’ BDI-II scores at baseline reflect mild to moderately elevated levels of current depressive symptoms.

Table 1.

Means and standard deviations of parent depressive symptoms and positive and negative parenting.

| Baseline | 2-months | 6-months | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| Written Information |

FGCB | Written Information |

FGCB | Written Information |

FGCB | |

|

|

||||||

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | |

| Parent Depressive Symptoms | ||||||

| BDI-II | 18.80 (11.20) | 19.66 (13.89) | 16.34 (10,60) | 13.33 (12,23) | ||

| Parenting | ||||||

| Observed Positive Parenting | 27.95 (5.04) | 27.63 (4.89) | 26.98 (5.65) | 27.47 (4,92) | ||

| Observed Negative Parenting | 24.25(5.44) | 23.92 (5.42) | 26.02 (5.73) | 24.92 (5.13) | ||

In some cases more than one child from the same family participated. Not surprisingly, prior research (Compas et al., 2010) indicated that the intraclass correlations (ICCs) for multiple children per family were significant for observed positive and negative parenting at 6-months, indicating that there was significant within-family similarity in parents’ behaviors with their children. Therefore, congruent with the mediational analyses in Compas et al., we conducted our hypothesized directional mediational analyses using a more conservative approach that included only one child (n = 180) randomly selected for each family.

Correlations Between Mediator and Each Outcome at Baseline

Correlations were computed at baseline between parent depressive symptoms (mediator) and both positive and negative parenting. Parents BDI scores were negatively associated with positive parenting (r = −.27, p < .001) and positively associated with negative parenting (r = .26, p = .001). These findings indicate a cross-sectional link between parent depressive symptoms and parenting and provide initial justification for examining how the former variable may mediate change through intervention in the latter variable.

Direct Effects of Intervention on Outcomes

The effects of the intervention on the 6-month positive and negative parenting, controlling for baseline levels of these measures, were examined (τ in Figure 2). A significant effect favoring the FGCB intervention as compared to the Written Information comparison condition was found for positive (F (1, 46.9) = 4.01, p < .05) and negative (F (1, 42.2) = 3.47, p < .05) parenting. It is worth noting that the significant difference which emerged for positive parenting resulted from participants in the FGCB group decreasing less than those in the WI group from baseline to 6 months and the significant difference for negative parenting resulted from the FGCB participants increasing less than the WI participants from baseline to 6 months.

Effects of Intervention on Mediator

The effects of the intervention on the hypothesized mediator at the 2-month assessment, controlling for baseline levels of the mediator, are summarized in the second column of Table 2. A significant effect favoring the FGCB intervention as compared with the WI comparison condition was found: Participants in the FGCB intervention decreased more from baseline in parent depressive symptoms (p < .001). Thus, the hypothesized mediator met the first criterion defined by MacKinnon et al. (2002) as necessary to establish mediation (α path in Figure 1) based on the joint significance test.

Table 2.

Summary of the joint significance test of mediation.

| Mediator | Significant effects of intervention on mediator (α path)? |

6-month Parenting Outcomes |

Significant effects of mediator on outcomes (β and/or β’ paths)? |

Criteria for joint significance met? |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parent Depressive Symptoms |

Yes (F (1, 135) = 5.74** |

Negative Parenting |

No (F (1, 86.7) = 0.00) |

Yes (F (1, 86.6) = 4.63* |

Yes |

|

| |||||

| Positive Parenting |

No (F (1, 85.3) = 0.87) |

No (F (1, 85.7) =.04) |

No | ||

Note: p < .05;

p < .01

Analyses of Mediation of Intervention Effects on Parenting

Tests of the effect of the mediator on the outcomes are presented in the fourth column of Table 2. As outlined by Kraemer et al. (2002), evidence for mediation is provided by either a main effect for the mediator on the outcome (β path in Figure 2) or an interaction between the mediator and the intervention in predicting the outcome (β’ path in Figure 2). We included the main effect of the intervention on the outcomes (path τ in Figure 2) and controlled for baseline levels of the outcomes in the analyses.

A significant effect for parent depressive symptoms was found for negative parenting (F (1,86.6) = 4.63, p < .05), but not for positive parenting (see Table 2). Thus, as summarized in the last column of Table 2, evidence for mediation based on the joint significance test was found for negative, but not positive, parenting. The unstandardized estimate for negative parenting in the absence of the mediator was significant (τ: B = −1.65, SE = .89, p < .05); however, the effects of the intervention was no longer significant for negative parenting in the presence of the mediator (τ’: B = .99, SE = .91).

The effect size (i.e., proportion of the effect of the intervention on the outcome that is accounted for by the mediator) was calculated for parent depressive symptoms serving as a mediator of negative parenting. As inconsistent mediation models emerged (i.e., the direct effect has a different sign than the mediated effect), we followed MacKinnon et al.’s (2007) recommendation and used “absolute values of the direct and indirect effects prior to calculating the proportion mediated…” (p. 603). The effect size was .40, suggesting that the mediator accounted for a substantial portion of the effect of the intervention.

Discussion

The current study found that parent depressive symptoms served as a mediator of change for behaviorally observed negative, but not positive, parenting in a prevention program for families with a parent who has current or a history of major depressive disorder. The findings extended those of Garber et al. (2011) by examining behaviorally observed negative parenting and replicated and extended the Patterson et al. (2004) findings by identifying differential outcomes for positive and negative parenting. Furthermore, collecting data on parent depressive symptoms and parenting at different time points allowed us to extend findings by Foster et al. (2008).

Our first hypothesis was supported in that, relative to the comparison condition (WI), the FGCB intervention was associated with more effective parenting at the 6-month assessment. Additionally, as we have reported previously (Compas et al., 2010), changes in parenting at the 6-month assessment mediated change in child problem behavior at the 12-month assessment, supporting the importance of the parenting component of the intervention. One aspect of our current findings is noteworthy: Relative to the WI condition, the FGCB intervention prevented a deterioration of positive parenting and an increase in negative parenting. The findings suggest that, for parents with a current or history of depression, a more intense parenting intervention may be necessary to promote increases in positive parenting and decreases in negative parenting. Nevertheless, the FGCB intervention was more effective than the WI condition when parenting served as the outcome.

Consistent with our second hypothesis, relative to a comparison group (WI), the FGCB intervention was associated with a reduction in parent depressive symptoms although these symptoms were not the focus of the preventive intervention. These results are congruent with findings from the parenting intervention literature (e.g., Forehand et al., 1980; Shaw et al., 2009). There are at least three potential explanations for our findings. First, although reducing parent depressive symptoms was not the focus of our preventive intervention, the inclusion of material on the causes and, particularly, the consequences of these symptoms may have led to the changes which occurred. Second, by participating in a family-based intervention that addressed concerns about their children’s mental health, the FGCB intervention may have created a sense of optimism among parents, alleviating their depressive symptoms. Third, the behavioral activation inherent in attending a group session, socializing and working on common problems with other group members, and learning new skills may have contributed to a reduction in depressive symptoms. Future research can begin to address which of these potential mechanisms account for the FGCB intervention being associated with a reduction in parental depressive symptoms.

Consistent with our third hypothesis, change in parent depressive symptoms at the 2-month assessment mediated the FGCB intervention effects on negative, but not positive, parenting. This finding is congruent with Lovejoy et al.’s (2000) conclusions about the relative role parent depression may play in negative versus positive parenting. And, as already noted, negative parenting may be a function of depressive symptoms promoting negative appraisals of a child (Dix & Meunier, 2009). On the other hand, group differences in positive parenting with intervention may be more a function of direct skill building (e.g., use of positive reinforcement, monitoring) that is included in parenting programs, including the FGCB intervention. As these behaviors are more directly and intensely targeted than negative parenting in FGCB, they may be less susceptible to the influence of parent depressive symptoms.

There are several limitations in the current study that can be addressed in future research. First, the current sample was somewhat limited in diversity and the findings reported here should be examined in more racially and ethnically diverse samples. Second, the sample included both currently depressed parents (27%) and those with a history of depression but not currently depressed. Differential relationships may emerge for these two groups across child outcomes and the mediator. Unfortunately, there was not sufficient power or distribution of participants across levels of the variables of interest to examine the role of current versus past clinical depression or the role of demographic variables such as gender and marital status of parent. Future research with larger samples should examine these variables and if they influence the conclusions reached in the current investigation. Third, each construct of interest was assessed from only one source: Self-report (parent depressive symptoms) and parenting (behavioral observation). Different findings may have emerged with different sources of information. Fourth, consistent with hypotheses offered in the parent depression literature (e.g., Dix & Meunier, 2009; Gunlicks & Weissman, 2008), the current study examined and found support for parental depressive symptoms mediating intervention effects on parenting. Nevertheless, the current study did not examine if changes in parenting mediated changes in parent depressive symptoms. For example, more effective parenting could serve as a form of behavioral activation to alleviate depressive symptoms. Because behavioral observations of parenting at the 2-month assessment were not collected, we could not test this competing, but equally plausible, hypothesis. Future research should examine this hypothesis. Fifth, it is important to emphasize again that effect size measures for mediation are in their infancy (MacKinnon et al., 2007) and this is the case with a complex mixed-effects model.

There were also several strengths of the current study. First, different reporters of the constructs of interest reduced inflated relationships among measures that can occur with the same reporter. Furthermore, the inclusion of behavioral observations of parenting, the experimental manipulation of change through intervention, and the assessment of parent depressive symptoms and parenting at different points in time are major strengths of the study.

In summary, the current findings provide the first known evidence regarding the role of parent depressive symptoms as a mediator of parenting in preventive interventions for offspring of parents with current or a history of depression. Although not the focus of intervention, parent depressive symptoms changed, and this change was subsequently related to a key component of the intervention: Negative parenting. Although the current findings suggest that positive parenting skills can be enhanced without consideration of parental depressive symptoms, decreasing negative parenting is an equally important goal. Therefore, parental depressive symptoms are important to consider in parenting interventions with parents who are currently depressed or have a history of depression.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants R01MH069940 and R01 MH069928 from the National Institute of Mental Health and gifts from the Ansbacher family and from Patricia and Rodes Hart.

Footnotes

This proportion is not equivalent to an ordinary R2. Rather, this estimate reflects the proportion of the main effect of the intervention on the outcomes accounted for by the mediator.

References

- Alderfer MA, Fiese BH, Gold JI, Cutuli JJ, Holmbeck GN, Patterson J. Evidence-based assessment in pediatric psychology: Family measures. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2008;33:1046–61. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm083. doi:10.1093/jpepsy/jsm083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin SA, Murray DM, Shadish WR. Empirically supported treatments or Type I errors? Problems with the analysis of data from group-administered treatments. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:924–935. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.5.924. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.5.924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer DJ, Sterba SK, Halfors DD. Evaluating group-based interventions when control participants are ungrouped. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2008;43:210–236. doi: 10.1080/00273170802034810. doi: 10.1080/00273170802034810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beardslee WR, Wright BJ, Gladstone TRG, Forbes P. Long-term effects from a randomized trial of two public health preventive interventions for parental depression. Journal of Family Psychology. 2007;21:702–713. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.21.4.703. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.21.4.703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Ball R, Ranieri W. Comparison of Beck Depression Inventories -IA and -II in psychiatric outpatients. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1996;67:588–597. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6703_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compas BE, Champion JE, Forehand R, Cole DA, Reeslund KL, Roberts L. Mediators of 12-month outcomes of a family group cognitive-behavioral preventive intervention with families of depressed parents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2010;78:623–634. doi: 10.1037/a0020459. doi: 10.1037/a0020459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compas BE, Forehand R, Keller G, Champion A, Reeslund KL, Cole DA. Randomized clinical trial of a family cognitive-behavioral preventive intervention for children of depressed parents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77:1007–1020. doi: 10.1037/a0016930. doi: 10.1037/a0016930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compas BE, Forehand R, Champion JE, Keller G, Hardcastle EJ, Roberts L. Family group cognitive-behavioral preventive intervention for families of depressed parents: 18- and 24-month outcomes. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2011;79:488–499. doi: 10.1037/a0024254. doi: 10.1037/a0024254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compas BE, Keller G, Forehand R. Prevention of depression in families of depressed parents. In: Strauman T, Costanzo PR, Garber J, editors. Prevention of depression in adolescent girls: A multidisciplinary approach. Guilford; New York: 2011. pp. 318–339. [Google Scholar]

- Dix T, Meunier LN. Depressive symptoms and parenting competence: An analysis of 13 regulatory processes. Developmental Review. 2009;29:45–68. doi: 10.1016/j.dr.2008.11.002. [Google Scholar]

- England MJ, Sim LJ, editors. Depression in parents, parenting, and children: Opportunities to improve identification, treatment, and prevention. The National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairchild AJ, MacKinnon DP, Taborga MP, Taylor AB. R2 effect-size measures for mediation analyses. Behavior Research Methods. 2009;41:486–498. doi: 10.3758/BRM.41.2.486. doi: 10.3758/BRM.41.2.486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forehand R, Wells KC, Griest DL. An examination of the social validity of a parent training program. Behavior Therapy. 1980;11:488–502. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2011.03.031. [Google Scholar]

- Foster CE, Webster MC, Weissman MM, Pilowsky DJ, Wickramarante PJ, Trivedi MH. Remission of maternal depression: Relations to family functioning and youth internalizing and externalizing symptoms. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2008;37:714–724. doi: 10.1080/15374410802359726. doi: 10.1080/15374410802359726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garber J, Ciesla JA, McCauley E, Diamond G, Schloredt KA. Remission of depression in parents: Links to healthy functioning in their children. Child Development. 2011;82:226–243. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01552.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01552.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman SH, Gotlib H. Risk for psychopathology in the children of depressed mothers: A developmental model for understanding mechanisms of transmission. Psychological Review. 1999;106:458–490. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.106.3.458. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.106.3.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman SH, Rouse MH, Connell AM, Broth MR, Hall CM, Heyward D. Maternal depression and child psychopathology: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Child and Family Psychological Review. 2010;14:1–27. doi: 10.1007/s10567-010-0080-1. doi: 10.1007/s10567-010-0080-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman SH, Tully E. Depression in women who are mothers. In: Keyes CLM, Goodman SH, editors. Women and depression: A handbook for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, UK: 2006. pp. 241–280. [Google Scholar]

- Gunlick ML, Weissman MM. Change in child psychopathology with improvement in parental depression: A systematic review. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2008;47:379–389. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181640805. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181640805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE. Problem-solving skills training and parent management training for oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder. In: Weisz JR, Kazdin AE, editors. Evidence-based psychotherapies for children and adolescents. 2nd ed Guilford; New York: 2010. pp. 211–226. [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE, Wassell G. Therapeutic changes in children, parents, and families resulting from treatment of children with conduct problems. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;39:414–420. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200004000-00009. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200004000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer HC, Kiernan M, Essex M, Kupfer DJ. How and why criteria defining moderators and mediators differ between the Baron & Kenny and MacArthur approaches. Health Psychology. 2008;27:101–108. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.2(Suppl.).S101. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.2(Suppl.).S101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer HC, Wilson GT, Fairburn CG, Agras WS. Mediators and moderators of treatment effects in randomized clinical trials. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2002;59:877–883. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.10.877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim J, Wood BL, Miller BD. Maternal depression and parenting in relation to child internalizing symptoms and asthma disease activity. Journal of Family Psychology. 2008;22:264–273. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.22.2.264. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.22.2.264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovejoy MC, Graczyk PA, O’Hare E, Neuman G. Maternal depression and parenting behavior: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2000;20:561–592. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(98)00100-7. doi: 10.1016/S0272-7358(98)00100-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Fairchild AJ, Fritz MS. Mediation analysis. Annual Review of Psychology. 2007;58:593–614. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085542. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGilloway S, Mhaille GN, Bywater T, Furlong M, Leckey Y, Donnelly M. A parenting intervention for childhood behavioral problems: A randomized controlled trial in disadvantaged community-based settings. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2012;80:116–127. doi: 10.1037/a0026304. doi: 10.1037/a0026304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon RJ, Forehand RL. Helping the noncompliant child: Family-based treatment for oppositional behavior. Guilford Press; New York: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Melby JN, Conger RD. The Iowa Family Interaction Rating Scales: Instrument summary. In: Kerig PK, Lindahl KM, editors. Family observational coding systems: Resources for systemic research. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; Mahwah, NJ: 2001. pp. 33–58. [Google Scholar]

- Melby JN, Conger RD, Book R, Rueter M, Lucy L, Scaramella L. The Iowa Family Interaction Rating Scales. 5th ed. Institute for Social and Behavioral Research, Iowa State University; Ames, Iowa: 1998. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR, DeGarmo D, Forgatch MS. Systematic changes in families following prevention trials. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2004;32:621–633. doi: 10.1023/b:jacp.0000047211.11826.54. doi: 10.1023/B:JACP.0000047211.11826.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw DS, Connell A, Dishion TJ, Wilson MN, Gardner F. Improvements in maternal depression as a mediator of intervention effects on early childhood problem behavior. Development and Psychopathology. 2009;21:417–439. doi: 10.1017/S0954579409000236. doi: 10.1017/S0954579409000236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE, Bolger N. Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:422–445. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.7.4.422. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steer RA, Brown GK, Beck AT, Sanderson WC. Mean Beck Depression Inventory–II scores by severity of major depressive disorder. Psychological Reports. 2001;88:1075–1076. doi: 10.2466/pr0.2001.88.3c.1075. doi: 10.2466/pr0.2001.88.3c.1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolchik SA, West SG, Sandler IN, Tein J-Y, Coatsworth D, Griffin WA. An experimental evaluation of theory-based mother and mother-child programs for children of divorce. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:843–856. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.68.5.843. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]