Abstract

Psychiatric patients frequently exhibit long-chain n-3 (LCn-3) fatty acid deficits and elevated triglyceride (TAG) production following chronic exposure to second generation antipsychotics (SGA). Emerging evidence suggests that SGAs and LCn-3 fatty acids have opposing effects on stearoyl-CoA desaturase-1 (SCD1), which plays a pivotal role in TAG biosynthesis. Here we evaluated whether low LCn-3 fatty acid status would augment elevations in rat liver and plasma TAG concentrations following chronic treatment with the SGA risperidone (RSP), and evaluated relationships with hepatic SCD1 expression and activity indices. In rats maintained on the n-3 fatty acid-fortified (control) diet, chronic RSP treatment significantly increased liver SCD1 mRNA and activity indices (18:1/18:0 and 16:1/16:0 ratios), and significantly increased liver, but not plasma, TAG concentrations. Rats maintained on the n-3 deficient diet exhibited significantly lower liver and erythrocyte LCn-3 fatty acid levels, and associated elevations in LCn-6/LCn-3 ratio. In n-3 deficient rats, RSP-induced elevations in liver SCD1 mRNA and activity indices (18:1/18:0 and 16:1/16:0 ratios) and liver and plasma TAG concentrations were significantly greater than those observed in RSP-treated controls. Plasma glucose levels were not altered by diet or RSP, and body weight was lower in RSP- and VEH-treated n-3 deficient rats. These preclinical data support the hypothesis that low n-3 fatty acid status exacerbates RSP-induced hepatic steatosis by augmenting SCD1 expression and activity.

Keywords: Omega-3 fatty acids, Risperidone, Atypical antipsychotic, Stearoyl-CoA desaturase-1, Oleic acid, Polyunsaturated fatty acids, Triglycerides, Glucose, Liver, Rat

1. Introduction

Treatment-emergent elevations in serum triglyceride (TAG) levels and weight gain are frequently observed in psychiatric patients following chronic exposure to second generation antipsychotic (SGA) medications, including clozapine, quetiapine, olanzapine, and risperidone (RSP)[1-3]. SGA-induced elevations in TAG levels has significant health consequences because it increases risk for metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular disease, obesity, and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), a syndrome characterized by excessive hepatic TAG accumulation (i.e., hepatic steatosis) and increased vulnerability to hepatotoxicity [4]. This is particularly problematic in view of epidemiological data indicating that there has been a 6-fold increase in SGA prescription rates in pediatric and adolescent patients during the past decade [5,6], and prospective studies indicate that youth are highly vulnerable to SGA-induced TAG increases and weight gain [7-10]. Moreover, in clinical practice most children starting SGA medications do not receive recommended regular glucose or lipid screening/monitoring [11]. These data highlight the urgent need to identify modifiable risk and protective factors associated with adverse cardiometabolic effects of SGA medications.

One mechanism that may increase risk for SGA-induced hyperlipidemia is a deficiency in long-chain omega-3 (LCn-3) fatty acids, including eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA, 20:5n-3) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA, 22:6n-3)[12]. Specifically, increasing LCn-3 fatty acid status through dietary supplementation is efficacious for reducing elevated TAG levels [13], and LCn-3 fatty acids are approved by the United States FDA for the treatment of hypertriglyceridemia. Preclinical feeding studies have found that low LCn-3 fatty acid status is associated with greater liver TAG content and secretion in different rodent models [14-19]. Clinical studies have found that red blood cell (RBC) and liver LCn-3 fatty acid levels are positively correlated [20], and patients with obesity and NAFLD exhibit significantly lower liver and RBC LCn-3 fatty acid levels [20-22]. Importantly, schizophrenic [23-25] and bipolar disorder [26-28] patients treated with SGA medications also exhibit significantly lower RBC LCn-3 fatty acid levels compared with healthy controls. Lastly, increasing LCn- 3 fatty acid status through dietary supplementation decreased elevated serum TAG levels in SGA-treated patients [29,30]. Together, these data suggest that low LCn-3 fatty acid status may represent a modifiable risk factor for SGA-induced elevations in TAG production and weight gain.

Translational evidence further suggests that stearoyl-CoA desaturase-1 (SCD1, Δ9-desaturase) plays a pivotal role in regulating lipid and metabolic homeostasis [31]. Preclinical studies have demonstrated that mutation of the SCD1 gene impairs constitutive and diet-induced TAG production [32-34], increases insulin sensitivity [35], and reduces visceral adiposity and increases resistance to diet-induced obesity [36]. Selective pharmacological inhibition of the SCD1 enzyme reduces elevated TAG and glucose levels in rodent metabolic disease models [37,38]. Feeding high-carbohydrate diets is associated with the up-regulation of hepatic SCD1 mRNA expression and elevated fasting and postprandial TAG levels in rodent models [39]. In human subjects, elevations in the plasma product-precursor ratio of oleic acid to stearic acid (18:1/18:0), an index of SCD1 activity (the ‘desaturation index’), is positively correlated with human liver biopsy SCD1 mRNA expression [40], plasma TAG levels [41], and obesity [39]. Together, this body of evidence suggests that SCD1 plays a pivotal role in regulating lipid and metabolic homeostasis.

Converging evidence suggests that LCn-3 fatty acids and SGA medications both converge on SCD1 expression and activity. Specifically, in vitro studies have found that different SGA medications up-regulate SCD1 mRNA expression in human cell lines and rat hepatocytes [42-45], and that chronic SGA treatment increases adipose SCD1 mRNA expression and SCD1 activity indices in rats [46,47]. Schizophrenic patients treated with the SGA olanzapine exhibit greater SCD1 mRNA expression in peripheral blood cells compared with drug-free patients [48]. In contrast to SGA medications, LCn-3 fatty acids down-regulate SCD1 mRNA expression at the level of transcription and mRNA stability [49], and dietary LCn-3 fatty acid supplementation decreases SCD1 activity in rat liver microsomes ex vivo [50] and SCD1 activity indices in human subjects [51,52]. We recently reported that dietary-induced n-3 fatty acid deficiency robustly up-regulated SCD1 mRNA expression and activity in rat liver, and that this effect was positively correlated with postprandial plasma TAG levels and prevented by prior normalization of n-3 fatty acid status [15]. Together, these data suggest that SGA medications and LCn-3 fatty acid have opposing effects on SCD1 mRNA expression and activity.

These translational data suggest that the low LCn-3 fatty acid status may increase vulnerability to elevated TAG production following chronic exposure to SGA medications by augmenting hepatic SCD1 expression and activity. Evaluation of these relationships in clinical populations is complicated by difficult-to-control variables that influence lipid and metabolic homeostasis, including medications and dietary carbohydrate and fatty acid intake, and definitive evaluation requires the use of an animal model so that these variables can be systematically manipulated. The primary objectives of the present study were to evaluate the hypothesis that low LCn-3 fatty acid status is associated with greater TAG elevations in response to chronic RSP treatment, and to evaluate relationships with hepatic SCD1 expression and activity. We additionally investigated relationships with body weight gain and plasma glucose levels. Based on the evidence reviewed above, our specific prediction was that low LCn-3 fatty acid status would be associated with greater RSP-induced elevations in liver and plasma TAG concentrations, and associated increases in liver SCD1 expression and activity.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Diets

The compositions of the α-linolenic acid (ALA, 18:3n-3)-fortified (control, ALA+, TD.04285, Harlan-TEKLAD, Madison, WI) and ALA-(TD.04286) diets are presented in Table 1. Diets were vacuum packaged and stored at 4°C. Both diets provided 3.8 Kcal/g (15.9 kJ/g), and were matched for percent Kcal from protein (19.2%), carbohydrate (64.4%), and fat (16.5%). The control diet was fortified with flaxseed oil (0.6%), which contains the short-chain n-3 fatty acid precursor ALA (18:3n-3). Analysis of diet fatty acid composition by gas chromatography confirmed that both diets were closely matched in saturated fatty acids, monounsaturated fatty acids, and the short-chain n-6 fatty acid precursor linoleic acid (18:2n-6)(Table 1).

Table 1.

Diet Compositions

| Ingredient1 | ALA+ | ALA− |

|---|---|---|

| Casein, vitamine free | 20 | 20 |

| Carbohydrate | ||

| Cornstarch | 20 | 20 |

| Sucrose | 27 | 27 |

| Dextrose | 9.9 | 9.9 |

| Maltose-dextrin | 6 | 6 |

| Cellulose | 5 | 5 |

| Mineral mix | 3.5 | 3.5 |

| Vitamin mix | 1 | 1 |

| L-Cystine | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| Choline bitartrate | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| TBHQ | 0.002 | 0.002 |

| Fat | ||

| Hydrogenated coconut oil | 4.5 | 5.1 |

| Safflower | 1.9 | 1.9 |

| Flaxseed | 0.6 | 0 |

| Fatty acid composition2 | ||

| C8:0 | 4.3 | 5.0 |

| C10:0 | 3.8 | 4.2 |

| C12:0 | 29 | 32.8 |

| C14:0 | 11 | 12.5 |

| C16:0 | 8.3 | 8.7 |

| C18:0 | 9.4 | 10.2 |

| 18:1n-9 | 6.7 | 4.7 |

| 18:2n-6 | 22.7 | 21.9 |

| 20:4n-6 | nd | nd |

| 18:3n-3 | 4.6 | nd |

| 22:6n-3 | nd | nd |

g/100 g diet

wt % of total fatty acids

nd = not detected

2.2. Animals

Male offspring were bred in-house to nulliparous female Long-Evans hooded rats. To generate rats with low LCn-3 fatty acid status, dams were fed the ALA-diet for 1 month prior to mating through weaning, and male offspring were maintained on the ALA-diet post-weaning (P21) to adulthood (P100)(n=20). Controls (i.e., normal LCn-3 fatty acid status) were born to dams maintained on the ALA+ diet, and received the ALA+ diet post-weaning (P21) to adulthood (P100)(n=20). Rats were housed 2 per cage with food and water available ad libitum, and maintained under standard vivarium conditions on a 12:12 h light:dark cycle. Food (g/kg/d) and water (ml/kg/d) intake, and body weight (kg) were recorded over the course of the experiment. Rats were euthanized by decapitation on P100-101 between 9:00-12:00 am in a counter-balanced manner relative to the common removal of food hoppers at 9:00 am. Trunk blood was collected into EDTA-coated tubes and plasma isolated by centrifugation at 4°C, and erythrocytes (red blood cells, RBC) washed 3x with 4°C 0.9% NaCl. Liver samples were uniformly harvested and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen. All biological samples were stored at −80°C. All experimental procedures were approved by the University of Cincinnati Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, and adhere to the guidelines set by the NIH.

2.3. Drug administration

On P60, one half of control (n=10) and n-3 deficient (n=10) rats were randomly assigned to receive chronic treatment with drug vehicle (n=10, 0.1 M acetic acid diluted in deionized water) or risperidone (n=10, 3.0 mg/kg/day; Ortho-McNeil Janssen Pharmaceuticals) through their drinking water, as previously described [47,53]. The 3.0 mg/kg/day dose was selected based on our prior studies finding that it produces therapeutically-relevant risperidone concentrations in rat [53]. We have previously found that low LCn-3 fatty acid status does not alter plasma RSP levels or pharmacokinetics (i.e., 9-OH-RSP/RSP ratio)[53]. For three days prior to drug delivery, 24 h water consumption was determined for each cage using bottle weights (1 g water = 1 ml water), and ml water intake/mean body weight (kg) calculated. Risperidone was dissolved in 0.1 M acetic acid in deionized water to prepare a stock solution (stored at 4°C) which was added to tap water in a volume required to deliver the targeted daily dose. To maintain intake of the targeted daily dose, drug concentrations were adjusted to mean daily fluid intake and mean body weight (ml/kg/day) every 3 days. Dehydration was routinely monitored over the course of the study using the skin tenting method. Red opaque drinking bottles were used to protect drug from light degradation. Rats were maintained on drug until being euthanized on P100 (i.e., 40 days of treatment).

2.4. Liver and plasma TAG concentrations

Liver tissue was homogenized, lipids extracted according to Folch et al. [54], and TAG concentrations (mg/g) assayed with a manual colormetric assay [55]. Plasma TAG concentrations were determined using commercially available kits according to the manufacturer’s instructions (GPO-PAP, RANDOX Laboratories Ltd., Antrim UK). All analyses were performed by a technician blinded to treatment.

2.5. Plasma glucose concentrations

Plasma glucose concentrations were determined using commercially available kits according to the manufacturer’s instructions (GOD-POD, Genzyme Diagnostics P.E.I. Inc., Charlottetown, PE, Canada). All analyses were performed by a technician blinded to treatment.

2.6. Fatty acid composition

The gas chromatography procedure used to determine RBC and liver total fatty acid composition has been described in detail previously [15, 47,53]. Briefly, total fatty acid composition was determined with a Shimadzu GC-2010 (Shimadzu Scientific Instruments Inc., Columbia MD). The column is a DB-23 (123-2332): 30m (length), I.D. (mm) 0.32 wide bore, film thickness of 0.25 μM (J&W Scientific, Folsom CA). The carrier gas was helium with a column flow rate of 2.5 ml/min. Analysis of fatty acid methyl esters was based on area under the curve calculated with Shimadzu Class VP 7.4 software. Fatty acid identification was based on retention times of authenticated fatty acid methyl ester standards (Matreya LLC Inc., Pleasant Gap PA). Analyses were performed by a technician blinded to treatment. Data are expressed as weight percent of total fatty acids (mg fatty acid/100 mg fatty acids). We also determined the composition of the principal substrates (16:0, 18:0) and products (16:1n-7, 18:1n-9) of SCD1, and calculated the liver 16:1/16:0 and 18:1/18:0 ratios as indices of liver SCD1 activity (‘destauration index’)[41]. We additionally calculated the liver 18:3n-6/18:2n-6 (delta6-desaturase), 20:4n-6/20:3n-6 (delta5-desaturase), and 16:0/18:2 (‘de novo lipogenesis’)[56-58] ratios.

2.7. Liver mRNA expression

Frozen liver was homogenized (BioLogics Model 300 V/T ultrasonic homogenizer, Manassas, VA) in Tri Reagent (MRC Inc., Cincinnati, OH), and total RNA isolated and purified using the RNeasy Lipid Tissue Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Total RNA was treated to remove potential DNA contamination using RNase-free DNase (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), and RNA quantified using a Nanodrop instrument (Nanodrop Instruments, Wilmington, DE). RNA quality was verified using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA). cDNA was prepared from 1 μg total RNA using the High-Capacity RNA-to-cDNA Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) along with no RT controls to confirm lack of genomic DNA contamination. Liver mRNA levels of stearoyl-CoA desaturase (SCD1, Rn00594894_g1) were measured by real-time quantitative PCR using an ABI 7900HT500 Real Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The nucleotide sequences of primer/probe sets can be obtained from www.appliedbiosystems.com. Samples were run as quadruplicates in Microamp Fast 96 well reaction plates using 20 μl reaction volumes consisting of 10 μl of 2X TaqMan Fast Universal PCR Mastermix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA), 1 μl of TaqMan gene expression assay, 4 μl of cDNA and 5 μl of DEPC-treated H2O. No template controls (NTC) substituting DEPC-treated water for cDNA were also run with each plate to verify lack of cross contamination. Thermal cycling conditions were: 95°C for 10 min followed by 95°C for 1 sec denaturing step and 60°C for 20 sec, annealing step for 40 cycles. Pilot studies found that the conventional housekeeping genes GAPDH, β-actin, and 18S rRNA were all significantly and selectively lower in the livers of RSP-treated n-3 deficient rats, whereas ribosomal protein L32 (Rn00820748_g1)[59,60] was stable across groups and was used as the reference gene.

Data were analyzed by both the standard curve and delta delta CT methods. For the standard curve method, serial dilutions of pooled sample reference cDNA were used to generate 5 point standard curves run in duplicate on each plate for both L32 and SCD1. Relative quantity values (RQ values) were generated by the Taqman 7900 HT software (7900 HT Sequence Detection System, version 2.3, Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Ca.) based on these curves. The relative expression of SCD1 for each sample was then calculated based on its RQ data normalized to the relative expression of the corresponding reference gene values. This analysis was confirmed by comparing cycle thresholds for both the target and housekeeping genes using the Relative Expression Software Tool (REST Version 2.0.13, Qiagen, Valencia, CA)[61], which employs the delta delta CT method [62] and also calculates efficiency of the reactions based on standard curves.

2.8. Statistical analysis

Group effects in fatty acid composition, product/precursor ratios, and liver gene expression data were evaluated with a two-way ANOVA, with diet (control, deficient) and treatment (vehicle, risperidone) as the main factors. Individual group differences were determined using t-tests (2-tail, α=0.05). The distribution of all dependent variables was examined for normality with Bartlett’s test. Liver Scd1 mRNA and TAG levels, and plasma TAG levels, were log transformed. Parametric (Pearson) correlation analyses were performed to determine relationships between primary outcome measures (2-tail, α=0.05). All analyses were performed with GB-STAT (V.10, Dynamic Microsystems, Inc., Silver Springs MD).

3. Results

3.1. Food/water intake and body weight

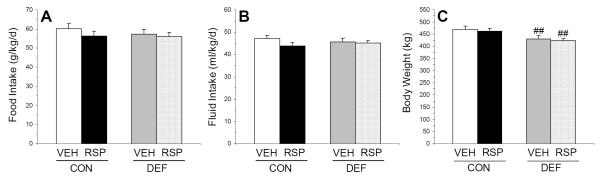

For food intake (g/kg/d), the main effect of diet (p=0.35) and treatment (p=0.19), and the diet x treatment interaction (p=0.50), were not significant (Fig. 1A). For fluid intake (ml/kg/d), the main effect of diet (p=0.91) and treatment (p=0.15), and the diet x treatment interaction (p=0.35), were not significant (Fig. 1B). For baseline (P60) body weight (CON+VEH: 349.9±8.6; CON+RSP: 349±12; DEF+VEH: 345±10; DEF+RSP: 345±9.2 kg), the main effect of diet (p=0.88) and treatment (p=0.68), and the diet x treatment interaction (p=0.85), were not significant. For endpoint (P100) body weight, there was a significant main effect of diet (p=0.004), and the main effect of treatment (p=0.58) and the diet x treatment interaction (p=0.94) were not significant. Compared with CON+VEH, DEF+VEH (p=0.01) and DEF+RSP (p=0.01), but not CON+RSP (p=0.97), rats exhibited significantly lower endpoint body weight (Fig. 1C).

Figure 1.

Effects of chronic treatment with VEH or RSP on (A) food intake (g/kg/d), (B) fluid intake (ml/kg/d), and (C) endpoint (P100) body weight (kg) in rats maintained on the control (CON, ALA+) or n-3 fatty acid deficient (DEF, ALA-) diet. Values are group mean ± S.E.M. ##p≤0.001 vs. same-treatment (VEH, RSP) in the control diet group.

3.2. Liver and plasma TAG concentrations

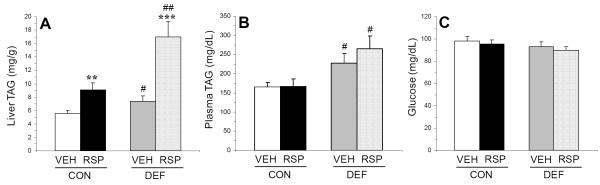

For liver TAG concentrations (mg/g), the main effects of diet (p≤0.0001) and treatment (p=0.0009) were significant, and the diet x treatment interaction was not significant (p=0.16). Compared with CON+VEH, CON+RSP (p=0.005), DEF+VEH (p=0.05), and DEF+RSP (p=0.0002) groups exhibited significantly greater liver TAG concentrations, and DEF+RSP exhibited significantly greater liver TAG concentrations compared with CON+RSP (p=0.006) and DEF+VEH (p=0.001)(Fig. 2A). For plasma TAG concentrations (mg/dL), the main effect of diet was significant (p=0.003), and the main effect of treatment (p=0.53) and the diet x treatment interaction (p=0.49) were not significant. Compared with CON+VEH, DEF+VEH (p=0.04) and DEF+RSP (p=0.01), but not CON+RSP (p=0.93), exhibited significantly greater plasma TAG concentrations, and DEF+RSP (p=0.01), but not DEF+VEH (p=0.39), exhibited significantly greater plasma TAG concentrations compared with CON+RSP (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

Effects of chronic treatment with VEH or RSP on (A) liver TAG concentrations (mg/g), (B) postprandial plasma TAG concentrations (mg/dL), and (C) postprandial plasma glucose concentrations (mg/dL) in rats maintained on the control (CON, ALA+) or n-3 fatty acid deficient (DEF, ALA-) diet. Values are group mean ± S.E.M. #p≤0.05, ##p≤0.01 vs. same-treatment (VEH, RSP) in the control diet group, **p≤0.01, ***p≤0.0001 vs. VEH-treated controls within each diet group. Note that statistical analyses were performed on log transformed liver and plasma TAG data.

3.3. Plasma glucose concentrations

For plasma glucose concentrations (mg/dL), the main effects diet (p=0.15) and treatment (p=0.44), and the diet x treatment interaction (p=0.94), were not significant (Fig. 2C).

3.4. Liver mRNA expression

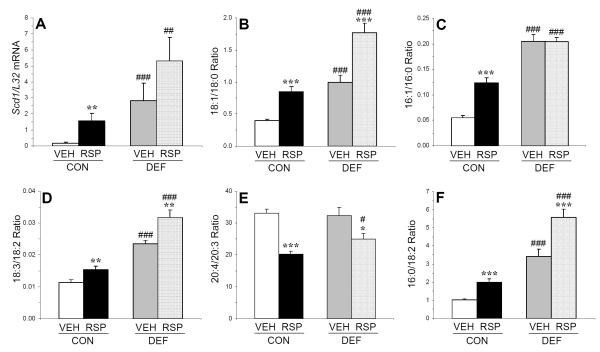

For L32 mRNA expression, the main effects of diet (p=0.69) and treatment (p=0.19), and the diet x treatment interaction (p=0.81), were not significant. For log transformed SCD1/L32 mRNA expression, the main effects of diet (p≤0.0001) and treatment (p=0.001), and the diet x treatment interaction (p=0.04), were significant (Fig. 3A). Compared with CON+VEH, CON+RSP (p=0.003), DEF+VEH (p≤0.0001) and DEF+RSP (p≤0.0001) exhibited significantly greater liver SCD1/L32 mRNA expression. Liver SCD1/L32 mRNA expression in the DEF+RSP group was greater than the CON+RSP group (p=0.01).

Figure 3.

Effects of chronic treatment with VEH or RSP on liver (A) SCD1/L32 mRNA expression, (B) the 18:1/18:0 ratio (C) the 16:1/16:0 ratio, (D) the 18:3/18:2 ratio, (E) the 20:4/20:3 ratio, and (F) the 16:0/18:2 ratio in rats maintained on the control diet (CON, ALA+) or n-3 fatty acid deficient (DEF, ALA-) diet. Values are group mean ± S.E.M. *p≤0.05, **p≤0.01, ***p≤0.0001 vs. VEH-treated controls within each diet group, #p≤0.05, ##p≤0.01, ###p≤0.0001 vs. same-treatment (VEH, RSP) in the control diet group. Note that statistical analyses were performed on log transformed SCD1/L32 mRNA data.

3.5. Liver and RBC fatty acid composition

Group differences in liver total fatty acid composition are presented in Table 2. Mead acid (20:3n-9) was detected in the livers, but not RBCs, of CON+RSP (0.25±0.02%) and DEF+RSP (0.24±0.02%, p=0.84) groups. For the liver 18:1/18:0 ratio (an index of delta9-desaurase activity), the main effects of diet (p≤0.0001) and treatment (p≤0.0001) were significant, and the diet x treatment interaction was not significant (p=0.11)(Fig. 3B). For the 16:1/16:0 ratio (an index of delta9-desaurase activity), the main effects of diet (p≤0.0001) and treatment (p≤0.0001), and the diet x treatment interaction (p=0.0002), were significant (Fig. 3C). For the 18:3/18:2 ratio (an index of delta6-desaurase activity), the main effects of diet (p≤0.0001) and treatment (p=0.0002) were significant, and the diet x treatment interaction was not significant (p=0.18)(Fig. 3D). For the 20:4/20:3 ratio (an index of delta5-desaurase activity), the main effect of treatment (p=0.002) was significant, and the main effect of diet (p=0.07) and the diet x treatment interaction (p=0.25), were not significant (Fig. 3E). For the 16:0/18:2 ratio (an index of DNL), the main effects of diet (p≤0.0001) and treatment (p≤0.0001) were significant, and the diet x treatment interaction was not significant (p=0.07)(Fig. 3F). Group differences in RBC total fatty acid composition are presented in Supplemental Table 1, and correlations between relevant RBC and liver fatty acids and fatty acid ratios are presented in Supplemental Table 2.

Table 2.

Liver fatty acid composition

| Fatty Acid1 | CON+VEH | CON+RSP | DEF+VEH | DEF+RSP |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Myristic acid (14:0) | 0.5 ± 0.03 | 1.1 ± 0.09 *** | 1.6 ± 0.07 ### | 2.4 ± 0.11 *** ### |

| Palmitic acid (16:0) | 18.3 ± 0.24 | 22.6 ± 0.79 *** | 22.7 ± 0.84 ### | 28.2 ± 0.79 ** ### |

| Stearic acid (18:0) | 18.1 ± 0.37 | 17.3 ± 0.51 *** | 15.5 ± 0.52 ### | 12.7 ± 0.58 *** ### |

| Total SFA | 36.9 ± 0.20 | 41.1 ± 0.48 *** | 39.8 ± 0.62 ### | 43.4 ± 0.64 *** # |

| Palmitoleic acid (16:1n -7) | 1.0 ± 0.10 | 2.9 ± 0.31 *** | 4.7 ± 0.41 ### | 5.8 ± 0.23 * ### |

| Oleic acid (18:1n -9) | 7.1 ± 0.25 | 15.2 ± 0.97 *** | 15.0 ± 1.18 ### | 21.9 ± 0.94 *** ### |

| Vaccenic acid (18:1n -7) | 3.1 ± 0.14 | 2.9 ± 0.11 *** | 4.7 ± 0.24 ### | 3.6 ± 0.25 ** # |

| Total MUFA | 11.2 ± 0.42 | 18.6 ± 1.96 ** | 24.4 ± 1.44 ### | 30.9 ± 0.98 ** ### |

| Linoleic acid (18:2n -6) | 18.1 ± 0.78 | 12.1 ± 0.83 *** | 7.3 ± 0.60 ### | 5.3 ± 0.28 ** ### |

| γ-Linoleic acid (18:3n -6) | 0.2 ± 0.01 | 0.2 ± 0.00 | 0.2 ± 0.02 | 0.2 ± 0.01 |

| Homo-γ-linoleic acid (20:3n -6) | 0.7 ± 0.04 | 0.9 ± 0.05 * | 0.6 ± 0.05 | 0.5 ± 0.05 ### |

| Arachidonic acid (AA, 20:4n -6) | 23.1 ± 0.51 | 17.4 ± 0.89 *** | 20.2 ± 1.14 # | 13.5 ± 0.81 *** |

| Docosatetraenoic acid (22:4n -6) | 0.4 ± 0.03 | 0.2 ± 0.02 *** | 0.5 ± 0.04 | 0.3 ± 0.02 ** ## |

| Docosapentaenoic acid (22:5n -6) | 0.2 ± 0.02 | 0.2 ± 0.02 | 4.7 ± 0.23 ### | 3.2 ± 0.19 *** ### |

| Total LCn -6 | 24.6 ± 0.54 | 18.8 ± 0.95 *** | 26.1 ± 1.30 | 17.7 ± 0.99 *** |

| α-Linolenic acid (18:3n -3) | 0.5 ± 0.05 | 0.4 ± 0.05 | nd ### | nd ### |

| Eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA, 20:5n -3) | 0.3 ± 0.02 | 0.4 ± 0.02 ** | nd ### | nd ### |

| Docosapentaenoic acid (22:5n -3) | 0.9 ± 0.03 | 0.7 ± 0.06 ** | nd ### | nd ### |

| Docosahexaenoic acid (DHA, 22:6n -3) | 6.6 ± 0.36 | 6.1 ± 0.23 | 0.5 ± 0.03 ### | 0.3 ± 0.02 ** ### |

| Total LCn -3 | 7.8 ± 0.32 | 7.2 ± 0.27 | 0.5 ± 0.03 ### | 0.3 ± 0.02 ** ### |

| AA/DHA | 3.5 ± 0.12 | 2.8 ± 0.10 *** | 42.9 ± 0.71 ### | 41.7 ± 0.98 ### |

| AA/EPA | 83.1 ± 6.57 | 46.2 ± 3.27 *** | 202.0 ± 9.21 ### | 135.1 ± 8.10 *** ### |

| AA/EPA+DHA | 3.4 ± 0.11 | 2.7 ± 0.09 *** | 35.2 ± 0.39 ### | 31.6 ± 0.73 *** ### |

| LCn -6/LCn -3 | 3.1 ± 0.08 | 2.6 ± 0.06 *** | 55.8 ± 1.20 ### | 54.7 ± 1.30 *** ### |

Data are expressed as mean ± S.E.M. weight percent total fatty acids nd = not detected (below the limit of detection)

P≤0.05

P≤0.01

P≤0.001 vs. VEH-treated controls within each diet group

P≤0.05

P≤0.01

P≤0.001 vs. same-treatment (VEH, RSP) in the control diet group

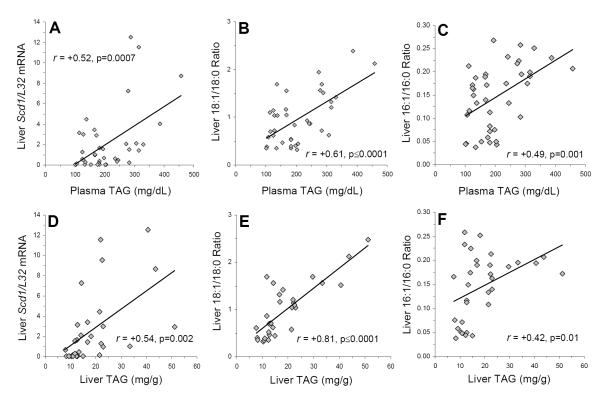

3.6. Correlations among primary outcome measures

Among all rats (n=40), liver SCD1/L32 mRNA expression was positively correlated with liver 18:1/18:0 (r = +0.63, p=0.0001) and 16:1/16:0 (r = +0.48, p=0.002) ratios. LCn-3 fatty acid composition was inversely correlated with Scd1/L32 mRNA expression (r = −0.65, p=0.0001), the liver 18:1/18:0 (r = −0.71, p≤0.0001) and 16:1/16:0 (r = −0.86, p≤0.0001) ratios, as well as liver (r = −0.44, p=0.01) and plasma (r = −0.48, p=0.001) TAG concentrations. Plasma TAG concentrations were positively correlated with liver SCD1/L32 mRNA expression (r = +0.52, p=0.0007)(Fig. 4A), the liver 18:1/18:0 ratio (r = +0.61, p≤0.0001)(Fig. 4B), and the liver 16:1/16:0 ratio (r = +0.49, p=0.001)(Fig. 4C). Liver TAG concentrations were positively correlated with liver SCD1/L32 mRNA expression (r = +0.54, p=0.002)(Fig. 4D), the liver 18:1/18:0 ratio (r = +0.81, p≤0.0001)(Fig. 4E), and the liver 16:1/16:0 ratio (r = +0.42, p=0.01)(Fig. 4F). Liver TAG concentrations were also positively correlated with plasma TAG concentrations (r = +0.35, p=0.05) and the liver 18:3/18:2 ratio (r = +0.61, p=0.0003), but not the liver 20:4/20:3 ratio (r = −0.23, p=0.19). Plasma TAG concentrations were positively correlated with the liver (r = +0.62, p≤0.0001) and RBC (r = +0.59, p≤0.0001) 16:0/18:2 ratio, and liver TAG concentrations were positively correlated with the liver (r = +0.76, p≤0.0001) and RBC (r = +0.37, p=0.03) 16:0/18:2 ratio. Liver and plasma TAG concentrations, liver SCD1/L32 mRNA expression, and the liver 18:1/18:0 and 16:1/16:0 ratios were not significantly correlated with plasma glucose concentrations or body weight.

Figure 4.

Relationships between plasma (A-C) and liver (D-F) TAG concentrations and liver Scd1/L32 mRNA expression (A,D), the liver 18:1/18:0 ratio (an index of SCD1 activity)(B,E), and the liver 16:1/16:0 ratio (an index of SCD1 activity). Pearson correlation coefficients and associated p-values (two-tailed) are presented.

4. Discussion

This preclinical study tested the hypothesis that low LCn-3 fatty acid status would augment treatment-emergent elevations in TAG levels and body weight in male rats following chronic RSP treatment, and investigated relationships with SCD1 expression and activity indices (16:1/16:0, 18:1/18:0). In support of our hypothesis, RSP-treated n-3 deficient rats exhibited significantly greater plasma and liver TAG levels compared with RSP-treated controls, as well as greater liver SCD1 mRNA expression and activity indices. Contrary to the hypothesis, RSP-treated n-3 deficient rats exhibited lower body weight compared with RSP-treated controls. In agreement with prior studies [15,18], VEH-treated n-3 deficient rats exhibited greater plasma and liver TAG levels, and greater SCD1 mRNA expression and activity compared with VEH-treated controls. Together, these preclinical data provide proof-of-concept evidence that low n-3 fatty acid status is a risk factor for greater RSP-induced hepatic steatosis, but not body weight gain or elevated glucose levels, and suggest a strong association with SCD1 expression and activity.

This study has three notable limitations. First, only male rats were employed, precluding evaluation of potential gender differences. However, male rats were selected to obviate potential interactions with rhythmical variations with ovarian hormones which were previously found to influence fatty acid biosynthesis [63]. Second, only one dose of RSP was investigated precluding evaluation of dose-response effects. However, the 3.0 mg/kg/day dose was specifically selected based on our prior studies finding that it produces therapeutically-relevant RSP concentrations in rat plasma [53], and produces only moderate increases in plasma TAG levels [47], thereby permitting evaluation of hypothesized augmenting effects of low LCn-3 fatty acid status. Third, only one type and class of antipsychotic was investigated, and other antipsychotic medications may be associated with different results. It is notably, however, that our prior study found that similar to RSP other SGA medications, including olanzapine and quetiapine, increase the plasma 18:1/18:0 ratio in control rats [47].

Consistent with prior studies finding that male rats do not exhibit treatment-emergent elevations in body weight following chronic exposure to atypical antipsychotic medications including RSP [47,64-66], the present study found that chronic RSP treatment did not significantly increase body weight gain in either control or n-3 deficient rats. Indeed, we found that chronic RSP treatment was associated with lower body weight in n-3 deficient rats. While the present study did not evaluate visceral adiposity, it may be relevant that a previous study found that chronic olanzapine treatment increased visceral adiposity in male rats despite reduced body weight, an effect that may be attributable to reductions in lean muscle mass [67]. However, in the present study RSP-treated rats maintained on the control diet did not exhibit body weight reductions, and VEH-treated rats maintained on the n-3 deficient diet exhibited a reduction in body weight, suggesting the effect can not be solely attributed to RSP-induced reductions in cage activity (i.e., sedation). Our results further suggest that elevated TAG levels are not associated with greater body weight gain. This finding is congruent with a recent study finding that semi-chronic treatment with olanzapine increased serum TAG levels but did not significantly increase body weight in pair-fed female rats [46], as well as clinical observations of elevated TAG levels but not body weight in SGA-treated patients [2,68,69].

Consistent with our prior dose-ranging study [47], the present study found that chronic treatment with RSP (3 mg/kg/d) did not significantly alter postprandial plasma TAG or glucose levels in rats maintained on the n-3 fatty acid-fortified diet. However, in the present study we found that chronic RSP treatment did increase liver TAG levels. Also consistent with our prior report [47], we found that chronic RSP treatment increased liver and RBC eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA, 20:5n-3) composition in rats maintained on the n-3 fatty acid-fortified diet (ALA+). Because this effect was not observed in rats maintained on the n-3 deficient diet (ALA-), this observation indicates that RSP augments ALA-EPA biosynthesis [53]. It is relevant, therefore, that prior studies have found that selectively increasing EPA intake is associated with reductions in liver TAG content and SCD1 mRNA and activity indices in mice fed a high-carbohydrate diet [70], and we previously found that EPA status was inversely correlated with plasma TAG levels in SGA-treated rats [47]. Moreover, EPA supplementation dose-dependently decreased elevated plasma TAG levels in clozapine-treated patients [30]. Therefore, elevations in ALA-EPA biosynthesis in RSP-treated rats maintained on the n-3 fatty acid-fortified diet may have counteracted increases in plasma TAG concentrations, despite greater liver TAG concentrations. These findings further suggest that augmentation of ALA-EPA biosynthesis may have contributed to the blunting of RSP-induced elevations in liver TAG concentrations in RSP-treated controls compared with RSP-treated n-3 deficient rats.

Feeding high-carbohydrate diets leads to significant elevations in the ‘de novo lipogenesis’ pathway, which converts excess carbohydrates to lipids for storage as fatty acids and TAG [57], and is associated with elevated hepatic SCD1 mRNA expression and TAG levels in rodents [33,34,39]. Clinical studies have found that feeding a high-carbohydrate diet is associated with a significant reduction in plasma TAG 18:2n-6 levels, and associated elevations in plasma TAG 16:0 levels and the 16:0/18:2 ratio [56-58]. In the present study, we similarly found that liver 18:2n-6 levels were significantly reduced, and liver 16:0 levels and the 16:0/18:2 ratio significantly increased, in RSP-treated rats despite equivalent carbohydrate intake. Moreover, we found that the liver 16:0/18:2 ratio was positively correlated with liver and plasma TAG levels as well as SCD1 expression and activity. Additionally, the present study found that 18:2n-6 levels were significant reduced, and the 18:3/18:2 ratio significantly increased, in the liver of RSP-treated rats despite similar 18:2n-6 intake, a finding that is consistent with elevated delta-6 desaturase activity [71,72]. It is relevant, therefore, that prior in vitro and in vivo studies have found that 18:2n-6 is a potent inhibitor of SCD1 transcription [49], suggesting that RSP- and diet-induced elevations in delta-6 desaturase-mediated 18:2n-6 consumption may contribute to the augmentation of SCD1 expression and activity. These data may also be relevant to understanding prior clinical evidence that delta-6 desaturase activity indices are positively associated with TAG levels [73].

The present observation that chronic dietary LCn-3 fatty acid deficiency is sufficient to cause excessive hepatic TAG accumulation (i.e., hepatic steatosis) is consistent with prior rodent studies [17,18], as well as the clinical observation that liver biopsies from patients with hepatic steatosis exhibit significantly lower LCn-3 fatty acid composition and a greater LCn-6/LCn-3 fatty acid ratio compared with healthy controls [20,22]. A novel finding of the present study is that prior dietary-induced reductions in liver LCn-3 fatty acid composition significantly augmented the development of hepatic steatosis in response to chronic RSP exposure. The reduction in liver arachidonic acid composition in RSP-treated rats irrespective of diet is also consistent with the finding that liver arachidonic acid composition is lower in patients with hepatic steatosis [22], and may reflect shunting away from fatty acid biosynthesis to cycloxygenase-2-mediated prostaglandin synthesis. This is supported in part by the finding that the fatty acid elongate product of arachidonic acid, docosatetranoic aicd (22:4n-6), was also significantly lower in RSP-treated rats irrespective of diet. It is also relevant that hepatic steatosis increases vulnerability to hepatotoxicity [4]. Although a prior histological study did not observe reductions in hepatocyte number following 42-day RSP treatment in rats maintained on n-3 fatty acid-fortified diet [74], additional histological studies are warranted to investigate whether low LCn-3 fatty acid status additionally increases vulnerability to RSP-induced hepatotoxicity.

In summary, the present study provides preclinical evidence that low n-3 fatty acid status augments RSP-induced hepatic steatosis independent of alterations in body weight or plasma glucose levels, as well as RSP-induced increases in liver SCD1 mRNA expression and activity. This preclinical finding, and the clinical observations that psychiatric patients treated with SGA medications exhibit low RBC LCn-3 fatty acid status [23-28] and increasing LCn-3 fatty acid status reduces TAG levels in patients treated with clozapine [29,30], suggest that low LCn-3 fatty acid status may represent a modifiable risk factor for SGA-induced hepatic steatosis. Indeed, together these data suggest that increasing LCn-3 fatty acid status may represent a viable adjunctive intervention to protect against the development of SGA-induced hepatic steatosis in psychiatric patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by National Institute of Health (NIH) grants MH083924 and AG03617, and a NARSAD Independent Investigator Award (to R.K.M.), and NIH grants DK59630 (to P.T.) and DK056863 (to S.C.B.). The authors thank Ortho-McNeil Janssen Scientific Affairs LLC for providing the risperidone, and S. Hofmann and E. Donelan for their technical assistance.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- [1].Henderson DC. Weight gain with atypical antipsychotics: evidence and insights. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68:18–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Meyer JM. Effects of atypical antipsychotics on weight and serum lipid levels. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62:27–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Newcomer JW. Antipsychotic medications: metabolic and cardiovascular risk. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68:8–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Chatrath H, Vuppalanchi R, Chalasani N. Dyslipidemia in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Semin Liver Dis. 2012;32:22–29. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1306423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Olfson M, Blanco C, Liu L, Moreno C, Laje G. National trends in the outpatient treatment of children and adolescents with antipsychotic drugs. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:679–685. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.6.679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Olfson M, Crystal S, Huang C, Gerhard T. Trends in antipsychotic drug use by very young, privately insured children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49:13–23. doi: 10.1097/00004583-201001000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Bond DJ, Kauer-Sant’Anna M, Lam RW, Yatham LN. Weight gain, obesity, and metabolic indices following a first manic episode: prospective 12-month data from the Systematic Treatment Optimization Program for Early Mania (STOP-EM) J Affect Disord. 2010;124:108–117. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Correll CU, Manu P, Olshanskiy V, Napolitano B, Kane JM, Malhotra AK. Cardiometabolic risk of second-generation antipsychotic medications during first-time use in children and adolescents. JAMA. 2009;302:1765–1773. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Moreno C, Merchán-Naranjo J, Alvarez M, Baeza I, Alda JA, Martínez-Cantarero C, Parellada M, Sánchez B, de la Serna E, Giráldez M, Arango C. Metabolic effects of second-generation antipsychotics in bipolar youth: comparison with other psychotic and nonpsychotic diagnoses. Bipolar Disord. 2010;12:172–184. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2010.00797.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Ratzoni G, Gothelf D, Brand-Gothelf A, Reidman J, Kikinzon L, Gal G, Phillip M, Apter A, Weizman R. Weight gain associated with olanzapine and risperidone in adolescent patients: a comparative prospective study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41:337–343. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200203000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Morrato EH, Druss B, Hartung DM, Valuck RJ, Allen R, Campagna E, Newcomer JW. Metabolic testing rates in 3 state Medicaid programs after FDA warnings and ADA/APA recommendations for second-generation antipsychotic drugs. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:17–24. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].McNamara RK. Modulation of polyunsaturated fatty acid biosynthesis by antipsychotic medications: Implications for the pathophysiology and treatment of schizophrenia. Clin Lipidol. 2009;4:809–820. [Google Scholar]

- [13].McKenney JM, Sica D. Prescription omega-3 fatty acids for the treatment of hypertriglyceridemia. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2007;64:595–605. doi: 10.2146/ajhp060164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Hassanali Z, Ametaj BN, Field CJ, Proctor SD, Vine DF. Dietary supplementation of n-3 PUFA reduces weight gain and improves postprandial lipaemia and the associated inflammatory response in the obese JCR:LA-cp rat. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2010;12:139–147. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2009.01130.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Hofacer R, Magrisso IJ, Rider T, Jandacek R, Tso P, Benoit SC, McNamara RK. Omega-3 fatty acid deficiency increases stearyl-CoA desaturase expression and activity indices in rat liver: Positive association with non-fasting plasma triglyceride levels. Prostogland Leukotrienes Essential Fatty Acids. 2011;85:225–231. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2011.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Lu J, Borthwick F, Hassanali Z, Wang Y, Mangat R, Ruth M, Shi D, Jaeschke A, Russell JC, Field CJ, Proctor SD, Vine DF. Chronic dietary n-3 PUFA intervention improves dyslipidaemia and subsequent cardiovascular complications in the JCR:LA-cp rat model of the metabolic syndrome. Br J Nutr. 2011;31:1–11. doi: 10.1017/S0007114510005453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Pachikian BD, Neyrinck AM, Cani PD, Portois L, Deldicque L, De Backer FC, Bindels LB, Sohet FM, Malaisse WJ, Francaux M, Carpentier YA, Delzenne NM. Hepatic steatosis in n-3 fatty acid depleted mice: focus on metabolic alterations related to tissue fatty acid composition. BMC Physiol. 2008;8:21. doi: 10.1186/1472-6793-8-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Pachikian BD, Essaghir A, Demoulin JB, Neyrinck AM, Catry E, De Backer FC, Dejeans N, Dewulf EM, Sohet FM, Portois L, Deldicque L, Molendi-Coste O, Leclercq IA, Francaux M, Carpentier YA, Foufelle F, Muccioli GG, Cani PD, Delzenne NM. Hepatic n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid depletion promotes steatosis and insulin resistance in mice: genomic analysis of cellular targets. PLoS One. 2011;6(8):e23365. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Qi K, Fan C, Jiang J, Zhu H, Jiao H, Meng Q, Deckelbaum RJ. Omega-3 fatty acid containing diets decrease plasma triglyceride concentrations in mice by reducing endogenous triglyceride synthesis and enhancing the blood clearance of triglyceride-rich particles. Clin Nutr. 2008;27:424–430. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Elizondo A, Araya J, Rodrigo R, Poniachik J, Csendes A, Maluenda F, Díaz JC, Signorini C, Sgherri C, Comporti M, Videla LA. Polyunsaturated fatty acid pattern in liver and erythrocyte phospholipids from obese patients. Obesity. 2007;15:24–31. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Burrows T, Collins CE, Garg ML. Omega-3 index, obesity and insulin resistance in children. Int J Pediatr Obes. 2011;6:e532–539. doi: 10.3109/17477166.2010.549489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Araya J, Rodrigo R, Videla LA, Thielemann L, Orellana M, Pettinelli P, Poniachik J. Increase in long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid n-6/n-3 ratio in relation to hepatic steatosis in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Sci (Lond) 2004;106:635–643. doi: 10.1042/CS20030326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Evans DR, Parikh VV, Khan MM, Coussons C, Buckley PF, Mahadik SP. Red blood cell membrane essential fatty acid metabolism in early psychotic patients following antipsychotic drug treatment. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2003;69:393–399. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2003.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Ranjekar PK, Hinge A, Hegde MV, Ghate M, Kale A, Sitasawad S, Wagh UV, Debsikdar VB, Mahadik SP. Decreased antioxidant enzymes and membrane essential polyunsaturated fatty acids in schizophrenic and bipolar mood disorder patients. Psychiatry Res. 2003;121:109–122. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(03)00220-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Reddy RD, Keshavan MS, Yao JK. Reduced red blood cell membrane essential polyunsaturated fatty acids in first episode schizophrenia at neuroleptic-naive baseline. Schizophr Bull. 2004;30:901–911. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Chiu CC, Huang SY, Su KP, Lu ML, Huang MC, Chen CC, Shen WW. Polyunsaturated fatty acid deficit in patients with bipolar mania. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2003;13:99–103. doi: 10.1016/s0924-977x(02)00130-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Clayton EH, Hanstock TL, Hirneth SJ, Kable CJ, Garg ML, Hazell PL. Long-chain omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in the blood of children and adolescents with juvenile bipolar disorder. Lipids. 2008;43:1031–1038. doi: 10.1007/s11745-008-3224-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].McNamara RK, Jandacek R, Rider T, Tso P, Dwivedi Y, Pandey GN. Selective deficits in erythrocyte docosahexaenoic acid composition in adult patients with bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder. J Affect Disord. 2010;126:303–311. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Caniato RN, Alvarenga ME, Garcia-Alcaraz MA. Effect of omega-3 fatty acids on the lipid profile of patients taking clozapine. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2006;40:691–697. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2006.01869.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Peet M, Horrobin DF, E-E Multicentre Study Group A dose-ranging exploratory study of the effects of ethyl-eicosapentaenoate in patients with persistent schizophrenic symptoms. J Psychiatr Res. 2002;36:7–18. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3956(01)00048-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Paton CM, Ntambi JM. Biochemical and physiological function of stearoyl-CoA desaturase. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2009;297:28–37. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.90897.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Miyazaki M, Kim YC, Gray-Keller MP, Attie AD, Ntambi JM. The biosynthesis of hepatic cholesterol esters and triglycerides is impaired in mice with a disruption of the gene for stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:30132–30138. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005488200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Miyazaki M, Kim YC, Ntambi JM. A lipogenic diet in mice with a disruption of the stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1 gene reveals a stringent requirement of endogenous monounsaturated fatty acids for triglyceride synthesis. J Lipid Res. 2001;42:1018–1024. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Miyazaki M, Dobrzyn A, Man WC, Chu K, Sampath H, Kim HJ, Ntambi JM. Stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1 gene expression is necessary for fructose-mediated induction of lipogenic gene expression by sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1c-dependent and -independent mechanisms. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:25164–25171. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402781200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Rahman SM, Dobrzyn A, Dobrzyn P, Lee SH, Miyazaki M, Ntambi JM. Stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1 deficiency elevates insulin-signaling components and down-regulates protein-tyrosine phosphatase 1B in muscle. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:11110–11115. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1934571100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Ntambi JM, Miyazaki M, Stoehr JP, Lan H, Kendziorski CM, Yandell BS, Song Y, Cohen P, Friedman JM, Attie AD. Loss of stearoyl-CoA desaturase-1 function protects mice against adiposity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:11482–11486. doi: 10.1073/pnas.132384699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Issandou M, Bouillot A, Brusq JM, Forest MC, Grillot D, Guillard R, Martin S, Michiels C, Sulpice T, Daugan A. Pharmacological inhibition of stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1 improves insulin sensitivity in insulin-resistant rat models. Eur J Pharmacol. 2009;618:28–36. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2009.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Uto Y, Ogata T, Kiyotsuka Y, Ueno Y, Miyazawa Y, Kurata H, Deguchi T, Watanabe N, Konishi M, Okuyama R, Kurikawa N, Takagi T, Wakimoto S, Ohsumi J. Novel benzoylpiperidine-based stearoyl-CoA desaturase-1 inhibitors: Identification of 6-4-(2-methylbenzoyl)piperidin-1-yl]pyridazine-3-carboxylic acid (2-hydroxy-2-pyridin-3-ylethyl)amide and its plasma triglyceride-lowering effects in Zucker fatty rats. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2010;20:341–345. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.10.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Flowers MT, Ntambi JM. Stearoyl-CoA desaturase and its relation to high-carbohydrate diets and obesity. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1791:85–91. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2008.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Peter A, Cegan A, Wagner S, Elcnerova M, Königsrainer A, Königsrainer I, Häring HU, Schleicher ED, Stefan N. Relationships between hepatic stearoyl-CoA desaturase-1 activity and mRNA expression with liver fat content in humans. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2011;300:E321–326. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00306.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Attie AD, Krauss RM, Gray-Keller MP, Brownlie A, Miyazaki M, Kastelein JJ, Lusis AJ, Stalenhoef AF, Stoehr JP, Hayden MR, Ntambi JM. Relationship between stearoyl-CoA desaturase activity and plasma triglycerides in human and mouse hypertriglyceridemia. J Lipid Res. 2002;43:1899–1907. doi: 10.1194/jlr.m200189-jlr200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Fernø J, Raeder MB, Vik-Mo AO, Skrede S, Glambek M, Tronstad KJ, Breilid H, Løvlie R, Berge RK, Stansberg C, Steen VM. Antipsychotic drugs activate SREBP-regulated expression of lipid biosynthetic genes in cultured human glioma cells: a novel mechanism of action? Pharmacogenomics J. 2005;5:298–304. doi: 10.1038/sj.tpj.6500323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Lauressergues E, Staels B, Valeille K, Majd Z, Hum DW, Duriez P, Cussac D. Antipsychotic drug action on SREBPs-related lipogenesis and cholesterogenesis in primary rat hepatocytes. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2010;381:427–439. doi: 10.1007/s00210-010-0499-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Polymeropoulos MH, Licamele L, Volpi S, Mack K, Mitkus SN, Carstea ED, Getoor L, Thompson A, Lavedan C. Common effect of antipsychotics on the biosynthesis and regulation of fatty acids and cholesterol supports a key role of lipid homeostasis in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2009;108:134–142. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2008.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Raeder MB, Fernø J, Vik-Mo AO, Steen VM. SREBP activation by antipsychotic- and antidepressant-drugs in cultured human liver cells: relevance for metabolic side-effects? Mol Cell Biochem. 2006;289:167–173. doi: 10.1007/s11010-006-9160-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Skrede S, Fernø J, Vázquez MJ, Fjær S, Pavlin T, Lunder N, Vidal-Puig A, Diéguez C, Berge RK, López M, Steen VM. Olanzapine, but not aripiprazole, weight-independently elevates serum triglycerides and activates lipogenic gene expression in female rats. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2012;15:163–179. doi: 10.1017/S1461145711001271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].McNamara RK, Jandacek R, Rider T, Tso P, Cole-Strauss A, Lipton JW. Atypical antipsychotic medications increase postprandial triglyceride and glucose levels in male rats: relationship with stearoyl-CoA desaturase activity. Schizophr Res. 2011;129:66–73. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2011.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Vik-Mo AO, Birkenaes AB, Fernø J, Jonsdottir H, Andreassen OA, Steen VM. Increased expression of lipid biosynthesis genes in peripheral blood cells of olanzapine-treated patients. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2008;11:679–684. doi: 10.1017/S1461145708008468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Landschulz KT, Jump DB, MacDougald OA, Lane MD. Transcriptional control of the stearoyl-CoA desaturase-1 gene by polyunsaturated fatty acids. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;200:763–768. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.1516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Garg ML, Wierzbicki AA, Thomson AB, Clandinin MT. Dietary cholesterol and/or n-3 fatty acid modulate delta 9-desaturase activity in rat liver microsomes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1988;962:330–336. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(88)90262-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Telle-Hansen VH, Larsen LN, Høstmark AT, Molin M, Dahl L, Almendingen K, Ulven SM. Daily intake of cod or salmon for 2 weeks decreases the 18:1n-9/18:0 ratio and serum triacylglycerols in healthy subjects. Lipids. 2012;47:151–160. doi: 10.1007/s11745-011-3637-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Velliquette RA, Gillies PJ, Kris-Etherton PM, Green JW, Zhao G, Vanden Heuvel JP. Regulation of human stearoyl-CoA desaturase by omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids: Implications for the dietary management of elevated serum triglycerides. J Clin Lipidol. 2009;3:281–288. doi: 10.1016/j.jacl.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].McNamara RK, Able JA, Jandacek R, Rider T, Tso P. Chronic risperidone treatment preferentially increases rat erythrocyte and prefrontal cortex omega-3 fatty acid composition: Evidence for augmented biosynthesis. Schizophr Res. 2009;107:150–157. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2008.09.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Folch J, Lees M, Stanley GH Sloane. A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipides from animal tissues. J Biol Chem. 1957;226:497–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Biggs HG, Erikson JM, Moorehead WR. A manual colormetric assay of triglycerides in serum. Clin Chem. 1975;21:437–441. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Chong MF, Hodson L, Bickerton AS, Roberts R, Neville M, Karpe F, Frayn KN, Fielding BA. Parallel activation of de novo lipogenesis and stearoyl-CoA desaturase activity after 3 d of high-carbohydrate feeding. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87:817–823. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/87.4.817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Chong MF, Fielding BA, Frayn KN. Metabolic interaction of dietary sugars and plasma lipids with a focus on mechanisms and de novo lipogenesis. Proc Nutr Soc. 2007;66:52–59. doi: 10.1017/S0029665107005290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Hudgins LC, Hellerstein M, Seidman C, Neese R, Diakun J, Hirsch J. Human fatty acid synthesis is stimulated by a eucaloric low fat, high carbohydrate diet. J Clin Invest. 1996;97:2081–2091. doi: 10.1172/JCI118645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Cai JH, Deng S, Kumpf SW, Lee PA, Zagouras P, Ryan A, Gallagher DS. Validation of rat reference genes for improved quantitative gene expression analysis using low density arrays. Biotechniques. 2007;42:503–512. doi: 10.2144/000112400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].de Jonge HJ, Fehrmann RS, de Bont ES, Hofstra RM, Gerbens F, Kamps WA, de Vries EG, van der Zee AG, te Meerman GJ, ter Elst A. Evidence based selection of housekeeping genes. PLoS One. 2007;2(9):e898. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Pfaffl MW, Horgan GW, Dempfle L. Relative expression software tool (REST) for group-wise comparison and statistical analysis of relative expression results in real-time PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:e36. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.9.e36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].McNamara RK, Able JA, Liu Y, Jandacek R, Rider T, Tso P. Gender differences in rat erythrocyte and brain docosahexaenoic acid composition: Role of ovarian hormones and dietary omega-3 fatty acid composition. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2009;34:532–539. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.10.013. 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Ota M, Mori K, Nakashima A, Kaneko YS, Takahashi H, Ota A. Resistance to excessive bodyweight gain in risperidone-injected rats. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2005;32:279–287. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2005.04184.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Pouzet B, Mow T, Kreilgaard M, Velschow S. Chronic treatment with antipsychotics in rats as a model for antipsychotic-induced weight gain in human. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2003;75:133–140. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(03)00042-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Minet-Ringuet J, Even PC, Goubern M, Tomé D, de Beaurepaire R. Long term treatment with olanzapine mixed with the food in male rats induces body fat deposition with no increase in body weight and no thermogenic alteration. Appetite. 2006;46:254–262. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2006.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Cooper GD, Pickavance LC, Wilding JP, Harrold JA, Halford JC, Goudie AJ. Effects of olanzapine in male rats: enhanced adiposity in the absence of hyperphagia, weight gain or metabolic abnormalities. J Psychopharmacol. 2007;21:405–413. doi: 10.1177/0269881106069637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Birkenaes AB, Birkeland KI, Engh JA, Faerden A, Jonsdottir H, Ringen PA, Friis S, Opjordsmoen S, Andreassen OA. Dyslipidemia independent of body mass in antipsychotic-treated patients under real-life conditions. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;28:132–137. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e318166c4f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Procyshyn RM, Wasan KM, Thornton AE, Barr AM, Chen EY, Pomarol-Clotet E, Stip E, Williams R, Macewan GW, Birmingham CL, Honer WG, Clozapine and Risperidone Enhancement Study Group Changes in serum lipids, independent of weight, are associated with changes in symptoms during long-term clozapine treatment. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2007;32:331–338. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Kajikawa S, Harada T, Kawashima A, Imada K, Mizuguchi K. Highly purified eicosapentaenoic acid prevents the progression of hepatic steatosis by repressing monounsaturated fatty acid synthesis in high-fat/high-sucrose diet-fed mice. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2009;80:229–238. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2009.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Hofacer R, Rider T, Jandacek R, Tso P, Magrisso IJ, Benoit SC, McNamara RK. Omega-3 fatty acid deficiency selectively up-regulates delta6-desaturase expression and activity indices in rat liver: Prevention by normalization of omega-3 fatty acid status. Nutr Res. 2011;31:715–722. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2011.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].McNamara RK, Rider T, Jandacek R, Tso P, Cole-Strauss A, Lipton JW. Differential effects of antipsychotic medications on polyunsaturated fatty acid biosynthesis in rats: Relationship with liver delta6-desaturase expression. Schizophr Res. 2011;129:56–65. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2011.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Steffen LM, Vessby B, Jacobs DR, Jr, Steinberger J, Moran A, Hong CP, Sinaiko AR. Serum phospholipid and cholesteryl ester fatty acids and estimated desaturase activities are related to overweight and cardiovascular risk factors in adolescents. Int J Obes (Lond) 2008;32:1297–1304. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Halici Z, Keles ON, Unal D, Albayrak M, Suleyman H, Cadirci E, Unal B, Kaplan S. Chronically administered risperidone did not change the number of hepatocytes in rats: a stereological and histopathological study. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2008;102:426–432. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2007.00198.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.