Abstract

Contrary to intuition, no environmental exposure has been proved to cause human germ line mutations that manifest as heritable disease in the offspring, not among the children born to survivors of the American atomic bombs in Japan nor in survivors of cancer in childhood, adolescence, or young adulthood who receive intensive chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or both. Even the smallest of recent case series had sufficient statistical power to exclude, with the usual assumptions, an increase as small as 20 % over baseline rates. One positive epidemiologic study of a localized epidemic of Down syndrome in Hungary found an association with periconceptual exposure to a pesticide used in fish farming, trichlorfon. Current population and occupational guidelines to protect against genetic effects of ionizing radiation should continue, with the understanding they are based on extrapolations from mouse experiments and mostly on males. Presently, pre-conceptual counseling for possible germ cell mutation due to the environment can be very reassuring, at least based on, in a sense, the worst-case exposures of cancer survivors. Prudence demands further study. Future work will address the issue with total genomic sequencing and epigenomic analysis.

Keywords: Germ line mutations, Genetic counseling, Cancer survivors, Human environmental mutagens

Your child had a spontaneous change or mutation in the egg or sperm that led to her. It is nothing you did or did not do during your pregnancy or before conception, it just happens.

These words are repeated in medical genetics clinics every week, when a child presents with a single gene mutation, such as neurofibromatosis 1 or achondroplasia, as a new case in a family with no other affected relative. This explanation is in line with the fact that no environmental agent has been proved to cause germ cell mutations that manifest as hereditary disease in the offspring. To biologists, the term “spontaneous” is ignoble and was discarded three centuries ago when referring to the “spontaneous” generation of life, but continues to be used when talking about mutations. One might better say the causes of human germ line mutations are unknown or “agnogenic.”

History: one positive epidemiologic study

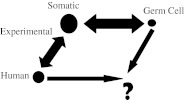

The Nobel-winning work of H. J. Muller was on the effects of X-radiation on genes in Drosophila (Muller 1927). The sustained work of James V. Neel and his colleagues was the search for genetic changes in the children of the American atomic bomb survivors in Japan (Neel and Schull 1991; Schull 2003). More than two decades ago, Sobels made a parallelogram that emphasized the void in understanding human germ cell mutagenesis (Sobels 1993; modified as Fig. 1). The figure points out that much is known about mutagenesis in experimental somatic cell systems and some about its relevance to human somatic changes and experimental germ cell mutagenesis (Russell and Shelby 1985), but there is not even one point of calibration that relates human germ cell mutagenesis to human somatic cell mutagenesis or animal work!

Fig. 1.

Filling the void in understanding human germ cell mutagenesis (adapted from Sobels 1993)

Apart from the unlikely possibility that there are no environmental human germ cell mutagens, the reasons for the disparity between human and animal studies are many: insufficient numbers of human subjects, insensitive methods to detect mutations, the diversity and lack of specificity of defects induced by radiation in DNA and chromosomes, inadequate length, intensity, or type of environmental exposure, inadequate dosimetry, and the possible lethality of germ cells injured by environmental mutagens. Maybe there are mechanisms of DNA repair in human germ cells that are not present in rodent germ cells or human somatic cells that could account for the failure to document a human germ cell mutagen. Yet, biologic intuition would say that it would not be prudent to put the issue aside from further consideration.

The one epidemiologic study that suggested an environmentally induced episode of human germ cell mutagenesis involved chemical exposure acting on the ovary (Czeizel et al. 1993), not radiation acting during male gametogenesis. In a rural village in Rinya, Hungary, an excess of Down syndrome was spotted by monitoring national birth defect rates. The epidemic correlated with the introduction of new methods for raising pond fish commercially. Residents realized that the local fish farm had begun using a pesticide that paralyzed fish causing them to float to the surface temporarily, where they were accessible, especially for their Easter feasts which demanded fresh fish. Molecular studies showed that all aneuploidies that could be tested were due to errors in the second meiotic division (which occurs just weeks before fertilization), not the first (which is typical of most Down syndrome babies and occurs in the fetal ovary as primary oocytes are being produced in third trimester). When the farming practice was changed, the epidemic ceased.

The episode points to the merit of population-based birth defects monitoring and interdisciplinary studies and the need to interpret the findings on human germ cell mutagenesis with an eye toward molecular mechanisms of actions. It also illustrates possible ambiguity between teratogenesis (exposures that affect the already conceived organism) and mutagenesis (exposures before conception to the reproductive system of the parent). This review excludes teratogenicity.

Of course, environmental factors are constantly interacting with individual genomes at all life stages to produce the types of diseases individuals develop and their ages of onset: gametogenesis, embryonic and fetal development, infancy, childhood, adolescence, and adult. There are macro-environmental challenges, chronic or cyclical, like air, water, or soil pollution, global warming, and various types of natural and man-made radiation. Usually, mutagenesis is difficult to study, often because the timing and doses of exposure to individuals are not known.

Detecting germ cell mutagenesis in offspring—theory

Heritable mutagenesis is a process that, in theory, has both a background component that is intrinsic to an individual and an induced component that results from environmental exposures. An as yet unidentified fraction of hereditary human disease is almost certainly attributable to the environment, but likely very little, at least in the case of ionizing radiation. In the absence of adequate human data, modeling and extrapolation have guided public policy and occupational health guidelines.

For over two decades, Sankaranarayanan (Sankaranarayanan and Wassom 2008; Sankaranarayanan and Nikjoo 2011) advanced several model concepts that could be used to develop or modify a way to assess human genetic risk from exposure to ionizing radiation. The existing paradigm is based on the assumption that adverse effects of radiation will be manifested in progeny of exposed individuals as genetic diseases similarly distributed as those that occur naturally in the population. With limited human data, risk is generally estimated using three components: the doubling dose for radiation-induced germ cell mutations in male mice, the background rate of “sporadic” genetic disease in human beings, and population genetics theory. Recent estimates suggest that the genetic risk associated with chronic low-dose ionizing radiation is 3,000 to 4,700 cases per million first generation offspring per Gy. This rate represents 0.4 % to 0.6 % of the baseline frequency of affected births (738,000 cases per million births). The baseline estimate includes chronic multifactorial diseases in the population (650,000 per million, mostly of adult onset), congenital malformations (60,000 per million), Mendelian diseases (24,000 per million), and chromosomal diseases (4,000 per million) (National Research Council 2006).

Detecting germ cell mutagenesis in offspring—practice

There are three available populations that are suitable to serve as an “exposed” group for the study of germ cell mutagenesis and other adverse genetic effects, namely a cohort approach. [A case–control approach starts with people with clearly de novo germ line mutation, such as sporadic Mendelian skeletal dysplasias or phakomatoses, versus controls without such mutations. That approach is impractical because of the bias of recalling events that could be important in gametogenesis. For example, if first meiosis of oocytes is deemed a possibly important stage of egg production, one would have to interview the maternal grandmother of events in her third trimester, when the eggs of the proband's mother were dividing in the fetal ovary (Mulvihill 1982).]

One type of exposed cohort is a population residing in areas of high background ionizing radiation, the most studied group to date being in Kerala on the southwest coast of India, that has a 55 × 0.5-km belt of high-level background radiation due to thorium and its decay products in the monazite-bearing sands. Although no excess of infant mortality has been seen, a possibly higher increased rate of Down syndrome, but not other congenital malformations, has been documented (Jaikrishan et al. 1999). No excess of mitochondrial DNA mutations were seen in exposed women (Forster et al. 2002).

A second type of exposed cohort consists of the Japanese survivors of the American atomic bombs as a prototype for nuclear bomb tests, as mentioned above (Neel and Schull 1991; Schull 2003), and of other events or accidents involving ionizing radiation, e.g., in power generation disasters in Chernobyl and after the Fukushima, Japan earthquake and tsunami of 2011, and weapons testing in Russia (Dubrova et al. 2002; Dubrova 2003). The work in Hiroshima and Nagasaki revealed no adverse pregnancy outcomes by multiple endpoints: congenital malformations, stillbirths, neonatal deaths, cytogenetic abnormalities, sex ratio at birth, childhood cancer death, protein polymorphisms, and microsatellite variants (Neel and Schull 1991; Schull 2003).

A third type of exposure is medical, both drugs and ionizing radiation. Czeizl, mentioned above with regard to the epidemic of Down syndrome in Hungary, has separately pursued work on the offspring of young adults who survived suicidal events (and failed to die), but went on to reproduce (Czeizel 1994). His focus has been on teratogenicity (Czeizel 2011), but the rationale and preliminary findings addressed germ cell mutagenicity as well (Czeizel 1996). The rationale is that a suicidal effort is a very high-dose exposure to a single agent and that the individuals are known to the healthcare system. He has seen no excess of genetic disease in limited studies (Czeizel et al. 1999).

We have pursued another medical exposure, namely cancer survivors, as a sustained, high dose scenario of gonadal exposure, where the dose of specific agents can be retrieved because individuals are in the healthcare system.

Pre-conceptual exposure to cancer therapy

As cancer survivorship increases, especially in children and young adults, there are increasing numbers of people of reproductive age who have survived cancer and its treatment in infancy, childhood, teenage years, and young adult life. They were exposed to very high levels of ionizing radiation, alkylating agents, and other drugs with mutagenic potential in experimental systems, even to the point of temporary or permanent infertility. Their doses can be accurately known for they are in the healthcare system and records are available, even the original port film and radiotherapy doses. There is increasing public interest and advocacy on the issue, especially in the US, with the Lance Armstrong Foundation and the concern for quality of life issues in survivors including in matters of sexuality and reproduction. These factors produce good cooperation for studies of germ cell mutagenesis (see volunteer's video at http://www.uhatok.com/news/video-news-releases/276-genetic-impact-of-radiation-exposure).

After we and others assembled small case series, all with negative findings summarized elsewhere (Mulvihill 1993), our first analytic epidemiologic effort was called the Five Center Study of 2,300 survivors of cancer diagnosed under age 20 years between 1945 and 1975 in five areas of the US (Byrne et al. 1998). Genetic disease was defined as a cytogenetic defect, single gene defect, or a common multifactorial birth defect (specifically, those tracked by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). Genetic disease occurred in 3.4 % of 2,198 offspring of childhood and adolescent cancer survivors compared with 3.1 % of 4,544 offspring of controls, not statistically significantly different. Numbers were sufficient to exclude, with the usual assumptions, an increase as small as 20 % over baseline rates. The comparisons of survivors treated by potentially mutagenic therapy (ionizing radiation below the diaphragm and above the knees or an alkylating agent or both), with survivors not so treated showed no association with sporadic genetic disease.

This design was enlarged about ninefold by the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (CCSS) launched in 1994, and still underway (Robison et al. 2002) (Table 1). It is a consortium of pediatric oncology centers at 26 North American institutions that enrolled 14,357 cases from 20,691 eligible five-year survivors of six major tumor sites and types (leukemia, lymphoma, most brain tumors, sarcomas, neuroblastoma, and kidney cancers), diagnosed under the age of 21 years between 1970 and 1986. Clinical information was gathered by questionnaire, some personal interviews, and abstracts of medical records. Preliminary results of the retrospective cohort analysis were similar to those of the five-center study, namely genetic disease in 2.6 % of 6,129 children of survivors and in 3.6 % of 3,101 offspring of controls (Mulvihill et al. 2001). A refined analysis yielded similar negative results and omitted the controls, but sought a dose–response effect over a wide range of estimated doses of ionizing radiation to the survivors' gonads, as well as semi-quantitative estimates of their doses of alklyating agents. The mean dose of radiation was 126 cGy to ovaries and 26 cGy to the testes (Signorello et al. 2012).

Table 1.

Genetic disease in children of cancer survivors (<35 years at diagnosis) and sibling controls from the combined Danish and Finnish study and the Childhood Cancer Survivors Study (CCSS) of the US and Canada (all children were born after the cancer diagnosis of their parent)

| Adverse pregnancy outcomeb | Survivors (n = 20,617) | Sibling controls (n = 48,173) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survivor children (n = 35,801) | Sibling children (n = 104,523) | |||

| No. (%) children with genetic disease | RRa | 95 % CI | ||

| All cytogenetic abnormalities | 113df (0.32 %) | 292df (0.28 %) | 1.23c | 1.00–1.61 |

| All single-gene (Mendelian) disorders—Denmark and CCSS only | 178 (0.50 %) | 361 (0.34 %) | 1.22 | 1.00–1.48 |

| Simple malformation-10 specific typese | 448 (1.25 %) | 832 (0.80 %) | 1.06 | 0.90–1.26 |

| Stillbirths and neonatal deaths <28 days | 195 (0.54 %) | 350 (0.33 %) | 1.15 | 0.84–1.57 |

| Childhood leukemia (all types) <15 yearsg | 12 (0.03 %) | 63 (0.06 %) | 0.89 | 0.47–1.65 |

| Childhood cancer <15 yearsfg | 47 (0.13 %) | 177 (0.17 %) | 1.05 | 0.74–1.47 |

aAdjusted for country (not CCSS)

bA child with more than one outcome has been counted in the category of genetic condition with the highest genetic component (as listed); i.e., a child with a cytogenetic abnormality and a single-gene disorder was counted as a child with cytogenetic abnormality

cAdjusted for maternal age, to account for age effect in aneuploidy

dIncludes diagnoses from the Danish Cytogenetic Registry (live births, fetal terminations, and/or prenatal testing) and both numeric and structural chromosome aberrations

eMost likely to have a relatively high mutation component: anencephaly, spina bifida, hydrocephalus, transposition of the great vessels, septal defects, cleft lip (without cleft palate), tracheo-esophageal fistula, rectal atresia/stenosis, limb-reduction deformity, renal agenesis. Does not include hip dislocation, patent ductus, clubfoot, and hypospadias

fNon-hereditary outcomes, i.e., outcomes explained by heredity are excluded

gCCSS not included

Parallel to these findings from North America are studies of offspring of cancer survivors in two nations that include individuals with all tumor types diagnosed between 1950 and 1996 (Denmark) or 1993 and 2004 (Finland), but with the age of diagnosis extended up to 35 years of age, an age range never studied before, but still in the range of reproductive capacity (Table 1). The Scandinavian studies differ also by being population-based, embracing each entire nation, and by producing associated outcomes through linking data from long established registries of the population, vital records, and diseases, including cancer, birth defects, all hospitalizations, abortions, and stillbirths together with some special registries, for example, of cytogenetic abnormalities. Again, the comparison groups were similar data gained by record linkage of the offspring of siblings of the cancer survivors and seeking the same adverse pregnancy outcomes. The Scandinavian findings are largely negative, with a frequency of 1.8 % in the 23,889 children of 14,519 survivors compared to 1.4 % in the 98,465 children of 45,037 controls (Madanat-Harjuoja et al. 2010; Winther et al. 2004, 2009, 2010, 2012) (Table 1). Definitive analysis is underway, but to date, observed differences in percentages seem not to be significant and are attributable to differing definitions among the studies. In Denmark, a broad look at all birth defects, indeed all hospitalizations, of offspring of cancer survivors adds support, although the focus goes beyond disorders with conspicuous genetic determinants (Winther et al. 2010).

Principles and practice of counseling

The audience for counseling about possible mutagenic exposures may be, most typically, a woman or couple who already have a child with a genetic or congenital condition. Perhaps the condition is a known syndrome, clearly diagnosed, even with characterization of the cytogenetic anomaly or DNA mutation; or, the disorder may be clearly congenital, but not a recognized eponymic syndrome. Or, the focus of this special issue, a person, or couple may present for preconception advice, in general or with a concern for a specific environmental hazard they encountered. Or, a recent accident or revelation about a potentially harmful environmental exposure or contamination may have surfaced and public health official or the news media seek an expert opinion. In all cases, the succinct bottom line message is, “No environmental exposure has been proved to cause human germ line mutation seen as a hereditable disorder in the offspring, but additional research is warranted.”

In my opinion, the impact of that reassuring message varies with how it is delivered. The issue illustrates the tough task of giving personal or public reassurance about the lack of a harmful effect, in the face of limited information. The rebuttal, “But, counselor, how can you be sure?” must be answered, “I cannot be; life is full of uncertainties.” This is how I handle an inquiry.

Listen. If it is a couple in clinic, a reporter on the telephone, or a public health or government official at a meeting, they have to feel they have been heard and that I took time to learn what details they think are important about their concern. Elicit specifics about the exposure: What agent(s)? At what age? For how long? Were they or others acutely injured in any way? Probe the area of concern about a possible adverse outcome: Birth defect? Cancer? Infertility? Intellectual deficit? Probe for deeper levels of reasoning or association of the putative exposure with the possible adverse outcome: Is there guilt over some other issue? Unlawful exposures? Intent for litigation or other legal action? Intellectualization over the situation? False paternity? Intent or bias to have an abortion or to avoid an abortion?

Where possible, affirm the credibility or validity of some aspect of the initial concern. Yes, radiation has been associated with a risk for birth defects, but not from electromagnetic radiation of cell phones or high voltage transmission lines, nor from ultrasound, just for ionizing radiation, but not at doses received by dental examinations, and not X-rays before conception, but only after conception, that is, during pregnancy. Be sure to distinguish teratogenicity (adverse reproductive outcome due to transplacental exposure or maternal disorder present during the pregnancy, not addressed in this review) from mutagenesis (sudden and permanent change in genetic material, typically before conception).

Establish your interest and authority. “I'm especially interested in this issue and try to read everything about it. I've been on the Environmental Hazards Committee of the American Academy of Pediatrics. I've written some articles about.” Or, “I don't feel like an expert in the area, but I will find out who is, either in this area, or nationally, so you can run your concerns by a real pro.”

Give some related data or scientific knowledge and admit the absence or paucity of specific scientific information. “There was a report from Hungary years ago that linked Down syndrome occurrence to eating poisoned fish around the time of conception, but it has not been observed anywhere else.” “We know 4 % of pregnancies result in some adverse outcome in the baby, and know only some of the causes. I don't recognize those causes in your history and am not aware of a valid scientific study of offspring of men who chewed tobacco for several years before starting a pregnancy. That would be a nearly impossible study to do in America.” “Yes, ionizing radiation to adult male mice has caused mutations seen in their offspring, but mice are not human beings.”

- Tell the story of the lack of adverse reproductive outcomes in offspring of cancer survivors. The atomic bombs in Japan are known to most people, hence the story of six decades of research that show no genetic (germline) effects can be compelling because it contradicts expectations. Of course, the bombs were single exposures, with few survivors receiving large doses. Obviously, my bias is to tell the story of the offspring of survivors of cancers of early life, as a sustained exposure, often to radiotherapy and high-dose chemotherapy, often with temporary impairment of fertility, and sometimes with obvious evidence of somatic cell mutation, seen as additional primary malignant neoplasms. “If no effect was seen in 24,000 offspring of 15,000 cancer survivors with such toxic therapy, I think it is reasonable to conclude that the exposure you suffered would not have adverse effects” (Table 1). If pressed for details about offspring of cancer survivors, you can add:

- There is a known impairment of fertility, more in men than women, more in those with alkylating agents than other treatment that probably has to do with germ cell killing and not mutagenesis (Byrne et al. 1987). Still, sperm of treated males have abnormal chromosomes (Wyrobek et al. 2007), but such sperm may have diminished capacity to fertilize because cancer survivors seem to have no excess of children with cytogenetic disorders.

- There is a risk of prematurity, low birthweight, and stillbirths in the females (but not in conceptuses of males) treated with ionizing radiation to the pelvis in infancy and childhood, probably attributable to radiation damage to the infantile uterus, either connective tissue or vascular supply, not to germ line mutation (Signorello et al. 2010; Winther et al. 2012).

- There is a known excess of cancer due to the rare hereditary genetic predispositions to cancers such as retinoblastoma, nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome, and neurofibromatosis 1. Some of the syndromes that predispose to cancer present with congenital problems (Mulvihill 1999; Madanat-Harjuoja et al. 2010; Winther et al. 2010). So, therapy given to a parent with cancer complicating a syndrome should not be blamed for birth defects that are part of the syndrome that a child inherited.

Future work

In sum, the clinical epidemiologic studies are now large and reassuring for clinical and public health purposes, but subset analyses and improved measures of genomic damage are directions worth pursuing to add scientific rigor. One future direction for germ cell mutagenesis lies in combining a genomics approach with the present clinical studies. To be more specific, it has now been shown, as proof of principle, that a family of four can be totally sequenced (Roach et al. 2010; Conrad et al. 2011). A strategy for the future would be to sequence the cancer survivor (or other environmentally exposed individual), as well as his or her biological children and their other parent, to seek sequence abnormalities that seem de novo. Sequencing and haplotype construction would identify the parent of origin and the simple test would be whether or not the variants that are more frequent in the parent who was the cancer survivor.

There are many considerations that need to be resolved before such a strategy could be implemented, but it is now financially within reach. An ad hoc Working Group on what they call ENIGMA (Environmentally Induced Germline Mutation Analysis) is urging more research on the hazards of the environment on the human genome and epigenome (Yauk et al. 2012). There is an unknown correlation between the classic genetic laboratory measures of mutation and how well they are detected by sequencing: What does chromosomal breakage look like on a sequence or will all translocation chromosomes be detected? We know insertions and deletions can be picked up as copy number variations, but will sequencing detect chromosomal non-disjunction such as occurred in the Hungarian episode of Down syndrome? What if the mutation is a small increase in tandem repeat nucleotides?

As for study subjects, which cancer survivors or exposed people should be included? It has been a design weakness, accepted in the name of feasibility, that germ cell mutagenesis had been more frequently studied in male than female rodents. There is some suspicion that germ cell mutagenesis in males might vary with pubertal status, perhaps owing to the resting nature of the spermatogonia until puberty. Would the first test cases of families preferentially have radiotherapy only or chemotherapy only or some combinations? Which classes of chemotherapy are more suspect? At first, it would seem to be the alkylating agents, because of their lethal effect on gonial cells, but mouse work indicates that the post-gonial gametes might be more susceptible to environmental mutagenesis. The human analog would be to study offspring conceived by men who received chemotherapy within the 120 days before they sired the pregnancy. Of course, one advantage of cancer survivors is the availability of dosimetry. Should the cancer survivor show evidence of susceptibility to environmental mutagenesis, seen most blatantly as a second primary neoplasia, for example, a breast cancer in the field of ionizing radiation in a survivor of Hodgkin's lymphoma? To validate the credibility of a molecular observation of mutagenesis, it might be helpful to insist for the first study subjects that the child have a clinical manifestation of adverse pregnancy outcome as a sentinel event. Any family studied would have to be scrutinized for all the other etiologies of adverse pregnancy outcomes. Other exposures of legitimate concern, like tobacco use and atmospheric or local air pollution are fraught with the weakness of knowing exact dose and timing of exposure and the identification of suitable controls.

The exact laboratory methods need to be discussed. Total genomic sequencing is needed and feasible, but much information can be gained by limiting sequence to the 1 % that comprises the exome, perhaps with some adjacent sequences. But, in a sense, the thorough searches for clinical phenotypes could be considered an exomic screen. The recent sequence of a quartet revealed that much information is gained by having two offspring and a family structure that might obviate the need for deep repetitive coverage of the sequence so that, for example (Roach et al. 2010), fourfold may be sufficient instead of the usual standard of some 30- to 60-fold coverage. It would be probably helpful to go ahead with karyotyping, chromosomal assays, and, of course, paternity testing in any research strategy. It would be desirable to have sperm available on the father, so that, if the father is passing on a germ cell mutation, it will be discoverable in a recent ejaculate. Because of the explosion in epigenetics, it would be desirable to have appropriate samples and methods to address that hypothesis.

The informatics issues address, besides sequence coverage, the pursuit of inevitable variants and technical error rates, with an enormous falsely positive rate. The required numbers of families for study as well as their structure, that is the power calculations, deserve discussion. How much better are quartets than trios? Should half-siblings be preferentially sought?

Whatever study is launched might well be the opportunity for additional research on the ethical, legal, and social implications of genomics and human genetics in germ cell mutagenesis, and the strategies for genetic counseling. Issues of patient knowledge as well as their satisfaction with such research, their ability to consent, to understand the results, and to receive them, if they so desire, all need to be discussed.

In summary, the bulk of human evidence, quite contrary to intuition, suggests that the human germ cell genome is much more resistant to environmental mutagens than the usual murine models or even human somatic cells. This exceptionality may have evolutionary consequences, either favorable or unfavorable. It remains to be seen in another several eons after this industrial modern era.

Acknowledgments

Original work supported, in part, by the US National Cancer Institute (Grants U24CA55727 and 5R01CA104666).

Conflicts of interest

The author declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

A contribution to the special issue on Genetic Aspects of Preconception Consultation in Primary Care.

References

- Byrne J, Mulvihill JJ, Myers MH, Connelly RR, Naughton MD, Krauss MR, Steinhorn SC, Hassinger DD, Austin DF, Bragg K, Holmes GF, Holmes FF, Latourette HB, Weyer PJ, Meigs JW, Teta MJ, Cook JW, Strong LC (1987) Effects of treatment on fertility in long-term survivors of childhood and adolescent cancer. N Engl J Med 317:1315–1321 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Byrne J, Rasmussen SA, Steinhorn SC, Connelly RR, Myers MH, Lynch CF, Flannery J, Austin DF, Holmes FF, Holmes GE, Strong LC, Mulvihill JJ. Genetic disease in offspring of long-term survivors of childhood and adolescent cancer. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;62:45–52. doi: 10.1086/301677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrad DF, Keebler JE, DePristo MA, Lindsay SJ, Zhang Y, Casals F, Idaghdour Y, Hartl CL, Torroja C, Garimella KV, Zilversmit M, Cartwright R, Rouleau GA, Daly M, Stone EA, Hurles ME, Awadalla P, 1000 Genomes Project Variation in genome-wide mutation rates within and between human families. Nat Genet. 2011;43:712–714. doi: 10.1038/ng.862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czeizel AE. Budapest registry of self-poisoned patients. Mutat Res. 1994;312:157–163. doi: 10.1016/0165-1161(94)90021-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czeizel AE. Human germinal mutagenic effects in relation to intentional and accidental exposure to toxic agents. Environ Health Perspect. 1996;104(Suppl 3):615–617. doi: 10.1289/ehp.96104s3615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czeizel AE. Attempted suicide and pregnancy. J Inj Violence Res. 2011;3:45–54. doi: 10.5249/jivr.v3i1.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czeizel AE, Elek C, Gundy S, Métneki J, Nemes E, Reis A, Sperling K, Tímár L, Tusnády G, Virágh Z. Environmental trichlorfon and cluster of congenital abnormalities. Lancet. 1993;341:539–542. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)90293-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czeizel AE, Hegedüs S, Tímár L. Congenital abnormalities and indicators of germinal mutations in the vicinity of an acrylonitrile producing factory. Mutat Res. 1999;427:105–123. doi: 10.1016/S0027-5107(99)00090-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubrova YE. Long-term genetic effects of radiation exposure. Mutat Res. 2003;544:433–439. doi: 10.1016/j.mrrev.2003.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubrova YE, Grant G, Chumak AA, Stezhka VA, Karakasian AN. Elevated minisatellite mutation rate in the post-Chernobyl families from Ukraine. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;71:801–809. doi: 10.1086/342729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forster L, Forster P, Lutz-Bonengel S, Willkor H, Brinkmann B. Natural radioactivity and human mitochondrial DNA mutations. PNAS. 2002;99:13950–13954. doi: 10.1073/pnas.202400499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaikrishan G, Andrews VJ, Thampi MV, Koya PKM, Rajan VK, Chauhan PS. Genetic monitoring of the human population from high-level natural radiation areas of Kerala on the Southwest coast of India. I. Prevalence of congenital malformations in newborns. Rad Res. 1999;152:S149–S153. doi: 10.2307/3580135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madanat-Harjuoja LM, Malila N, Lähteenmäki P, Pukkala E, Mulvihill JJ, Boice JD, Jr, Sankila R. Risk of cancer among children of cancer patients: a nationwide study in Finland. Int J Cancer. 2010;126:1196–1205. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller HJ. Artificial transmutation of the gene. Science. 1927;66:84–87. doi: 10.1126/science.66.1699.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulvihill JJ. Towards documenting human germinal mutagens: epidemiologic aspects of ecogenetics in human mutagenesis. In: Sugimura T, Kondo S, Takabe H, editors. Environmental mutagens and carcinogens (Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Environmental Mutagens) New York: Alan R Liss; 1982. pp. 625–637. [Google Scholar]

- Mulvihill JJ. Genetic counseling of the cancer patient. In: DeVita VT Jr, Hellman S, Rosenberg SA, editors. Cancer principles and practice of oncology. 4. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott; 1993. pp. 2529–2537. [Google Scholar]

- Mulvihill JJ (1999) Catalog of human cancer genes: McKusick's Mendelian inheritance in man for clinical and research oncologists (OncoMIM). Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, 646 pp

- Mulvihill JJ, Strong LC, Robison LL. Investigators of the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study: genetic disease in offspring of survivors with childhood and adolescent cancer. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;69:A391. [Google Scholar]

- Health risks from exposure to low levels of ionizing radiation: BEIR VII phase 2. Washington: National Academies Press; 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neel JV, Schull WJ. The children of the atomic bomb survivors: a genetic study. Washington: National Academy Press; 1991. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roach JC, Glusman G, Smit AA, Huff CD, Hubley R, Shannon PT, Rowen L, Pant KP, Goodman N, Bamshad M, Shendure J, Drmanac R, Jorde LB, Hood L, Galas DJ. Analysis of genetic inheritance in a family quartet by whole-genome sequencing. Science. 2010;328:636–639. doi: 10.1126/science.1186802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robison LL, Mertens AC, Boice JD, Breslow NE, Donaldson SS, Green DM, Li FP, Meadows AT, Mulvihill JJ, Neglia JP, Nesbit ME, Packer RJ, Potter JD, Skiar CA, Smith MA, Stovall M, Strong LC, Yasui Y, Zeltzer LK. Study design and cohort characteristics of the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study: a multi-institutional collaborative project. Med Pediatric Oncol. 2002;38:229–239. doi: 10.1002/mpo.1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell LB, Shelby MD. Tests for heritable genetic damage and for evidence of gonadal exposure in mammals. Mutat Res. 1985;154:69–84. doi: 10.1016/0165-1110(85)90020-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sankaranarayanan K, Nikjoo H. Ionising radiation and genetic risks. XVI. A genome-based framework for risk estimation in the light of recent advances in genome research. Int J Radiat Biol. 2011;87:161–178. doi: 10.3109/09553002.2010.518214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sankaranarayanan K, Wassom JS. Reflections on the impact of advances in the assessment of genetic risks of exposure to ionizing radiation on international radiation protection recommendations between the mid-1950s and the present. Mutat Res. 2008;658:1–27. doi: 10.1016/j.mrrev.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schull WJ. The children of atomic bomb survivors: a synopsis. J Radiol Prot. 2003;23:369–384. doi: 10.1088/0952-4746/23/4/R302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Signorello LB, Mulvihill JJ, Green DM, Munro HM, Stovall M, Weathers RE, Mertens AC, Whitton JA, Robison LL, Boice JD. Stillbirth and neonatal death in relation radiation exposure before conception: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2010;376:624–630. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60752-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Signorello LB, Mulvihill JJ, Green DM, Munro HM, Stovall M, Weathers RE, Mertens AC, Whitton JA, Robison LL, Boice JD., Jr Congenital anomalies in the children of cancer survivors: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(3):239–245. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.37.2938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobels FH. Approaches to assessing genetic risks from exposure to chemicals. Environ Health Perspect. 1993;101(Suppl 3):327–332. doi: 10.1289/ehp.93101s3327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winther JF, Boice JD, Jr, Mulvihill JJ, Stovall M, Frederiksen K, Tawn EJ, Olsen JH. Chromosomal abnormalities among offspring of childhood-cancer survivors in Denmark: a population-based study. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;74:1282–1285. doi: 10.1086/421473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winther JF, Boice JD, Jr, Frederiksen K, Bautz A, Mulvihill JJ, Stovall M, Olsen JH. Radiotherapy for childhood cancer and risk for congenital malformations in offspring: a population-based cohort study. Clin Genet. 2009;75:50–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2008.01109.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winther JF, Boice JD, Jr, Christensen J, Frederiksen K, Mulvihill JJ, Stovall M, Olsen JH. Hospitalizations among children of survivors of childhood and adolescent cancer: a population-based cohort study. Int J Cancer. 2010;127:2879–2887. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winther JF, Olsen JH, Wu H, Shyr Y, Mulvihill JJ, Stovall M, Nielsen A, Schmiegelow M, Boice JD Jr (2012) Genetic disease in the children of Danish survivors of childhood and adolescent cancer. J Clin Oncol 30(1):27–33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Wyrobek AJ, Mulvihill JJ, Wassom JS, Malling HV, Shelby MD, Lewis SE, Witt KL, Preston RJ, Perreault SD, Allen JW, DeMarini DM, Woychik RP, Bishop JB; Workshop Presenters (2007) Assessing human germ-cell mutagenesis in the postgenome era: a celebration of the legacy of William Lawson (Bill) Russell. Environ Mol Mutagen 48:771–795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Yauk CL, Argueso JL, Auerbach SS, Awadalla P, Davis SR, DeMarini DM, Douglas GR, Dubrova YE, Elespuru RK, Glover TW, Hales BF, Hurles ME, Klein CB, Lupski JR, Manchester DK, Marchetti F, Montpetit A, Mulvihill JJ, Robaire B, Robbins WA, Rouleau G, Shaughnessy DT, Somers CM, Taylor JG VI, Trasler J, Waters MD, Wilson TE, Witt KL, Bishop JB (2012) Harnessing genomics to identify environmental determinants of heritable disease. In Review