Summary

Background

Candiduria is common in hospitalized patients but the clinical relevance is still unclear.

Objective

This study was done to further our knowledge on detection of and host responses to candiduria.

Patients

Urines and clinical data from 136 patients in whom presence of yeast was diagnosed by microscopic urinalysis were collected. Diagnosis by standard urine culture methods on blood and MacConkey agar as well as on fungal culture medium (Sabouraud dextrose agar) was compared. Inflammatory parameters (IL-6 and IL-17, Ig) were quantified in the urine and compared to levels in control patients without candiduria.

Results and Conclusions

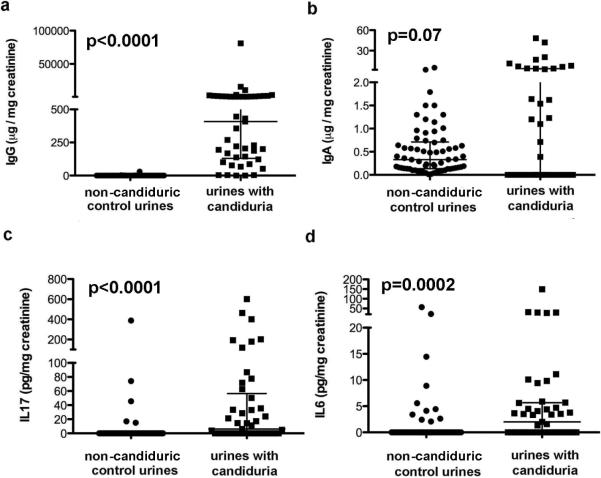

Standard urine culture methods detected only 37% of Candida spp. in urine. Sensitivity was especially low (23%) for C. glabrata and was independent of fungal burden. Candida specific IgG but not IgA was significantly elevated when compared to control patients (p<0.0001 and 0.07, respectively). In addition, urine levels of IL-6 and IL-17 were significantly higher in candiduric patients when compared to control patients (p<0.001). Multivariate analysis documented an independent association between an increased IgG (odds ratio (OR) 136.0, 95% confidence interval (CI) 25.7 to 719.2; p<0.0001), an increased IL-17 (OR 17.4, 95% CI 5.3–57.0; p<0.0001) and an increased IL-6 level (OR 4.9, 95% CI 1.9–12.4; p=0.001) and candiduria. In summary, our data indicate that clinical studies on candiduria should include fungal urine culture and that inflammatory parameters may be helpful to identify patients with clinically relevant candiduria.

Introduction

C. albicans is the most common fungal pathogen implicated in nosocomial urinary tract infection (UTI) (1, 2). Predisposing risk factors for patients to develop candiduria are old age, female sex, prior antibiotic usage and indwelling urinary draining devices (3, 4). Although candiduria is commonly associated with a benign outcome (5), some large studies of hospitalized patients have reported decreased survival of candiduric patients when compared with respective control populations (4, 6). Candidemia is associated with candiduria only in 0 to 8% of the cases (7–9). Thus, it remains unclear if candiduria contributes directly to mortality or alternatively merely constitutes a surrogate marker. Current treatment guidelines for candiduria (10) are based only on a few randomized studies. These showed that anti-fungal treatment commonly failed to successfully clear candiduria long-term, and that some patients cleared candiduria without treatment if urinary draining devices were removed (3, 9). This may explain why physicians do not follow treatment guidelines consistently (11).

One overlooked problem is the enigmatic definition of candiduria in epidemiologic and treatment studies. For example cut offs for defining candiduria can vary between 103–105 yeast cells per ml urine, and may even differ for men and women (9, 12). In the clinical setting, candiduria is usually diagnosed by standard urine culture methods on blood agar and MacConkey plates. These are culture media that best support growth of bacteria but are not optimal for yeast detection. Furthermore, although subjective symptoms and objective criteria such as biomarkers can be used to differentiate bacterial urinary tract colonization from infection, there is no clear understanding whether such criteria can be applied to differentiate harmless colonization from true disease in patients with candiduria. Therefore the objective of this study was to investigate diagnosis and inflammatory response of candiduria.

Material and Methods

Study design and urinalysis

Our data were generated from an initial pilot study followed by a cross-sectional design. Unrelated results of the initial pilot study are described elsewhere (13). Urines obtained at hospital out- and inpatient settings and sent for urinalysis and culture to the clinical laboratory at Montefiore Medical Center in the Bronx, NY were collected and medical records of included subjects were reviewed. The pilot study only included urine samples of candiduric patients (n=79). In the cross-sectional study urines from candiduric (n=54) and non-candiduric uninfected control (n=68) patients were included. For both studies the inclusion criteria were request and performance of microscopic urinalysis (UA) and standard urine culture. If yeast was documented by microscopy in the clinical laboratory then the urine sample was assigned to the “candiduria” group. If no microorganism were detected then the urine sample was assigned to the “control group” (cross sectional study only). Samples with bacterial co-infection (defined as bacteria CFU count >104/ml) were excluded. Urines were stored at 4°C prior to pickup and sent in parallel to the microbiology and research laboratory. Time before plating in research or clinical laboratory was comparable and usually occurred on the same day. Standard urine culture was performed by culture of 1 μl of urine on blood and Mac Conkey agar plates according to laboratory-based guidelines. Growth of Candida is only expected on blood agar plates. Patient data on age, underlying diagnosis, hospital course symptoms such as fever, dysuria, and mental status, as well as the presence of an indwelling urinary draining device, therapy, and hospital outcome were collected by retrospective chart review. For comparison of clinical data of candiduric patients diagnosed by standard vs fungal urine culture only, outpatients were excluded, because their medical records were incomplete for relevant clinical data. The protocol was reviewed and approved by the Albert Einstein College of Medicine IRB. Consent was waived by the IRB under 45 CFR 46.116(d).

CFU determination and speciation

In the research laboratory urine was spun at 2000 RPM to remove the yeast and stored in aliquots at minus 20°C for creatinine, cytokine and immunogobulin (Ig) quantification. Creatinine was quantified by a Chemistry Immuno Analyzer AU400 (Olympus Cooperation of the Americas, PA). Yeast cells in urines were enumerated by hemocytometer. Fungal urine cultures and colony forming units (CFU) were done on Sabouraud dextrose agar (SDA). Yeast species were determined by culture on Cornmeal-/BBL CHROM-agar (BD, NJ), and confirmed in unclear cases by VITEC based biochemical methods. Additional tests were done on subset of urines in both laboratories. They included plating with 1μl and 100μl inoculum on SDA and blood agar in the research laboratory, longer (72h) incubation on blood and MacConkey agar (BD, NJ) in the clinical laboratory, incubation at higher and lower (37°C and 30°C) temperatures, and culture on SDA with buffered pH to 7.5 by addition of sodium hydroxide.

Detection and quantifications of IgG, IgA, Interleukin 6 (IL-6) and Interleukin 17 (IL-17) in urine

IgG and IgA were measured by capture ELISA in a subset of candiduric patients (n= 48) and compared to values obtained from non-candiduric control urines (n= 68). For quantification by ELISA commercially available human IgG or IgA preparations were used as standard with a lower cutoff of 0.005 μg/ml. Ig levels were corrected for variable urine concentration by expressing the value as mg or μg of IgG or IgA per mg of creatinine. Westernblot was done to confirm that Abs were specific for Candida proteins. as described (14). In addition, Candida cells from urine were stained with immunofluorescence-labeled anti-human IgA and IgG Abs and visualized under 1000× on a fluorescent microscope.

IL-17 and IL-6 were measured in duplicates by ELISA (eBioscience, CA and R&D systems, MN) as per manufacturer's instruction. Lower limit of detection was 10 pg/ml and 1.25 pg/ml, respectively. Values of non-candiduric urines served as controls for measurement of Ig, IL-17 and IL-6 levels. Quantification of cytokine, chemokines, and IgA and IgGs was calculated as per mg creatinine in urine to adjust for the considerable variability of urine concentration.

Statistical analysis

Candiduric patients diagnosed either by fungal or standard urine culture were pooled together. For univariate analysis, depending on distribution, we used the t test for normally distributed variables and the Mann-Whitney U test for skewed variables. For categorical variables we used the chi-square test without correction for continuity. Multivariate logistic regression models were constructed to test whether there was an independent association between the outcome variable candiduria and other variables. Our main dependent variables of interest were Ig and cytokine levels. In the initial multivariate model, variables with p-value < 0.2 in the univariate analysis were included and those that are known to have an impact on Ig or cytokine expression. STATA statistical software, version 9.1 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas) was used for all statistical analyses.

Results

Recovery of Candida from patients that exhibited yeast on urinalysis

To compare sensitivity of standard vs fungal urine culture, urines from both studies (pilot and cross-sectional) were combined. A total of 136 urine samples with yeast on UA were sent for standard urine culture and also to the research laboratory for fungal urine culture. Fungal urine culture recovered Candida spp. in 133 (98%) urine samples. These included 79 patient samples from pilot and 54 from candiduric patients in the cross- sectional study. Candida spp distribution was as follows: C. albicans (51%), C. glabrata (40%), followed by C. tropicalis (8%) and C. parapsilosis (1%). Nineteen (13.5%) urines grew more than one Candida spp. Concomitant bacteriuria were reported in 13 (11%) patients, which were excluded. Comparison of recovery by standard and fungal urine culture demonstrated that only 37% of standard urine cultures grew Candida versus 98% of fungal urine cultures (p<0.001). Sensitivity of standard urine culture was lowest for C. glabrata (23%), followed by C. albicans (46%) and C. tropicalis (73%), respectively (Table1). Separate analysis of sensitivity of standard urine culture from urine samples collected for pilot and cross-sectional study yielded similar results (32% and 44%, p= 0.13). Urine fungal burden varied between 104 and 107 CFU/ml urine. Importantly, urine samples that grew in standard vs fungal urine culture only, exhibited comparable fungal burden (log CFU 5.62± 0.96 vs 5.64±1.0, p=0.4). Number of counted yeast cells correlated with cultured CFU, indicating that visualized yeasts on microscopy were viable. Neither pH of agar medium (pH 7.5 vs 5.5) nor incubation temperature (30° vs 37°C) or inoculation technique (1μl vs 100μl) affected the ability to grow Candida spp. on standard urine culture media (data not shown).

Table 1.

| Candida species | Growth supported on fungal culture medium | Growth supported on standard culture medium | p-value (Chi-square) |

|---|---|---|---|

| All Candida spp (n=136) | 133 | 48 | <0.001 |

| Candida albicans (n=66) | 66 | 30 | <0.001 |

| Candida glabrata (n=48) | 48 | 11 | <0.001 |

| Candida tropicalis (n=10) | 10 | 7 | NS |

| Other Candida spp (n=6) | 6 | 0 | <0.001 |

Characteristics of patients with candiduria diagnosed by standard vs fungal urine culture only

Characteristics of hospitalised patients only (n=109) with candiduria diagnosed by standard (n=44) vs fungal urine culture (n=65) only were compared (Table 2). Outpatients and patients with bacterial co-infection were excluded (n=24). Patients diagnosed by standard vs fungal urine culture only were comparable with respect to most characteristics. The majority of patients did not present with concomitant fever or dysuria. Of 4 patients that developed candidemia, Candida was not cultured by standard urine culture in 2. In those patients Candida was grown from blood at day 2, 11, 19, 22 respectively, after Candida was detected in urine. Only 1 candidemic patient had documented fever. Altered mental status was documented in both groups equally and could have interfered with accurate assessment of subjective symptoms. Noteworthy, hospital day of diagnosis, and antibiotic usage differed significantly between patients in whom candiduria was diagnosed by standard vs fungal urine culture alone. Only 4 of 22 (9%) patients, who received antifungal therapy met the definition of symptomatic candiduria (documentation of fever and/or dysuria). Leukocyte values were available in all patients. Only 22/109 (20%) of the patients exhibited large leukocyturia defined as >50 WBC /hpf. Their mean fungal burden in the urine was slighlty higher than in urines of patients without leukocyturia (6.18±0.86 vs 5.48 ± 0.99 log CFU/ml, p=0.003).

Table 2.

| Candiduric Patients diagnosed | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| by standard (n =44) | only by fungal (n =65) | p-value | |

| urine culture | |||

| Median age in years (range) | 77 (2–96) | 73 (15–95) | NS |

| Female (%) | 33 (75) | 52 (80) | NS |

| Day of Diagnosis of candiduria (range) | 10 (1 – 91) | 2 (0 – 44) | |

| Nursing home resident (%) | 16 (36.4) | 23 (35.4) | NS |

| Hemodialysis (%) | 3 (7) | 6 (9) | NS |

| ICU days, (median) | 14 (31.8) | 18 (35.1) | NS |

| Diabetes mellitus (%) | 24 (54.5) | 41 (63.1) | NS |

| Organ Transplant (%) | 0 | 1 (1.5) | NS |

| Neutropenia (%) | 2 (4.5) | 2 (3.1) | NS |

| Malignancy (%) | 7 (15.9) | 9 (13.8) | NS |

| Immunosuppression (%) | 4 (9) | 3 (4.6) | NS |

| Prior Antibiotics(%) | 32 (72.7) | 32 (49.2) * | 0.015 |

| Hospital admission in last 6 months (%) | 22 (50) | 34 (52.3) | NS |

| Surgery (%) | 9 (20.5) | 12 (18.5) | NS |

| Central line (%) | 16 (36.4) | 18 (27.7) | NS |

| Total parenteral nutrition (%) | 0 | 2 (3.1) | NS |

| Foley during hospital stay (%) | 29 (65.9) | 36 (55.4) | NS |

| Expired (%) | 7 (15.9) | 10 (15.4) | NS |

| Anatomical abnormalities (%) | 3 (7) | 12 (18.5) | NS |

| Fever(%) | 5 (11.4%) | 7 (10.8%) | NS |

| Dysuria (%) | 0 | 2 (3%) | NS |

| Altered Mental Status (%) | 11 (25%) | 7 (10.8%) | NS |

| Concomitant candidemia (%) | 2 (4.5%) | 2 (3%) | NS |

| Leukocyturia | 12 | 10 | NS |

Comparison of urine cytokine and Ig levels between candiduric and non-candiduric control patients

For the cross-sectional study control urines (n=68) were also collected as outlined. Creatinine, Ig and cytokine levels were quantified in urines of patients in both groups (Table 3). Creatinine levels in individual urines varied and also between the two groups. To adjust for variable urine concentration measured Ig and cytokine levels were expressed as μg/mg creatinine.

Table 3.

Comparison of candidunc patients with control patients

| Variables | candidunc patients (n=48) N (%) | non-candiduric control patients (n=68) N (%) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median age (years) | 59 (2–96) | 60.5 (14–89) | NS |

| Female | 40 (83) | 42 (62) | .01 |

| Nursing home resident (%) | 8 (17) | 1 (1.5) | .002 |

| Hemodialysis (%) | 2 (4) | 0 | NS |

| ICU (%) | 9 (19) | 2 (3) | .004 |

| Diabetes mellitus (%) | 20 (42) | 22 (33) | NS |

| Cardiac Disease (%) | 12 (25) | 28 (41) | NS |

| Malignancy (%) | 5 (10) | 8 (12) | NS |

| HIV+ (%) | 1 (2) | 1 (1.5) | NS |

| Prior Antibiotics (%) | 17 (42) | 3 (4.4) | <.0001 |

| Surgery (%) | 10 (21) | 3 (4.4) | .005 |

| Central venous line (%) | 3 (6) | 0 | NS |

| Foley at hospitalization (%) | 11 (23) | 6 (9) | .04 |

| Mortality (%) | 4 (9) | 1 (1.5) | NS |

| Leukocyturia (>50WBC/hpf) (%) | 9 (19) | 0 | .0002 |

| Proteinuria (%) | 22 (67) | 0 | <.0001 |

| Median creatinine in urine ug/ml (range) | 62 (6–374 ug/ml). | 105 (26 –39ug/ml) | 0.02 |

| IL-6 pg/mg Crea,mean (±SD) | 2.07 (UD-149) | 0 (UD-21.5) | 0.0002 |

| IL-17 pg/mg Crea, median (range) | 6.08 (UD-600) | 0 (UD-389) | < 0.0001 |

| IgG μg/mg Crea, median (range) | 408 (UD-81012) | 0.8 (0.1–31) | < 0.0001 |

| IgA μg/mg Crea, median (range)* | 0 (UD-48) | 0.33 (0.01–5.1) | 0.07 |

UD undetected

Urinary Ig level

We sought to determine if patients with candiduria excrete IgG and IgA into urine analogous to patients with bacteriuria. IgG was detectable in all candiduric urine samples and levels varied up to 10.000 fold. Most patients exhibited urine IgG levels 30–50 fold lower than IgG levels in serum (normal value 7–16 mg/ml) but individual patients excreted serum like quantities in their urine IgG (up to 5.8 mg/ml). Corrected median IgG levels in urine were significantly higher among candiduric than in control urine samples (median Ig 408 μg/mg vs 0.8 μg/mg, p<0.0001; Table 2). Importantly, IgG levels in candiduric patients did not correlate significantly with concomitant fungal burden in urine. In contrast, IgA levels were detected only in 65% of urine samples and were not significantly higher than those of control urines. In candiduric patients, the corrected median IgA levels were significantly lower than the IgG levels (p<0.0001). Westernblot analysis demonstrated that urine derived IgG recognized Candida proteins. Urines with low IgG levels exhibited less reactivity to Candida proteins and so did urines from patients infected with C. glabrata. Furthermore fluorescent staining with anti-human Ig Abs demonstrated that Candida derived from urine was coated with IgG (data not shown).

Cytokine response in urines of candiduric patients

IL-17 was detected in 54% of candiduric urine samples by ELISA with a cut off at 10 pg/ml. IL-17 was detected both in funguric patients diagnosed by standard or fungal urine culture. Adjusted by creatinine median IL-17 level was 6.08 pg/mg creatinine with a range of undetectable to 600 pg/mg and thus signicantly higher than in control urines (p<0.001). IL-17 was detected only in 5 (7.3%) control patients. IL-6 levels in urine were detected in 57% of candiduric urine samples with a cut off at 1.25 pg/ml. Adjusted median IL-6 level were 2.07 pg/mg with a range of undetectable to 149 pg/mg however. They were significantly higher (p=0.002) than IL-6 levels in control urines (13.%) with corrected levels ranging from undetected to 21.5 pg/mg.

Independent association of Ig and cytokine levels with the presence of candiduria

The underlying hypothesis that candiduric patients have significantly increased IgA and IgG levels as well as cytokine levels when compared to uninfected controls was then tested by multivariate analysis. Possible confounders that may affect cytokine and Ig excretion were tested and included age, gender, and indwelling catheter. Due to skewed distribution, Ig and cytokine levels were dichotomized with the cut-off based on the median values for all subjects. The cut-off value for IgG was 0.9 and for IgA 0.3 ug/mg creatinine. The median values for both IL-17 and IL-6 were 0 pg/mg creatinine, therefore a cut-off of 1 was chosen for both cytokines. We found an independent association between an increased IgG (odds ratio (OR) 136.0, 95% confidence interval (CI) 25.7 to 719.2; p<0.0001), an increased I-17 (OR 17.4, 95% CI 5.3–57.0; p<0.0001) and an increased IL-6 level (OR 4.9, 95% CI 1.9–12.4; p=0.001) and candiduria. In contrast, there was no significant association between an increased IgA level and candiduria.

Discussion

We demonstrate that candiduria is not adequately diagnosed by standard urine culture methods, which are optimized to support growth of bacteria. Patients whose candiduria did not grow on standard urine culture plates exhibit comparable urinary fungal burdens and similar clinical characteristics when compared to those whose candiduria is detected by standard methods. Although most candiduric patients in this study were asymptomatic, significantly elevated urine levels for IL-17, IL-6 and IgG were detected in candiduric patients when compared to non-candiduric control patients. In multivariate analysis increased IgG, IL-17 and IL-6 levels remained significantly associated, with candiduria after adjustment for age, sex and indwelling Foley. This indicates that multicenter prospective studies with larger numbers of patients should be undertaken to determine if biomarkers can be identified that help differentiate colonization and true disease in candiduric patients.

Most published clinical studies require 103–105 CFU/mL urine but either do not specify their culture methods or employ standard urine culture to identify patients with candiduria. The finding that urine but not blood derived Candida fail to grow on blood agar could indicate in vivo metabolic adaptation to specific microenvironments (reviewed in (15)) as been described for SAP among invasive and non-invasive C. albicans isolates (16). Regardless, our data suggests that only a fraction of candiduric patients were included in most published studies. This diagnostic dilemma has been acknowledged by experts in the field (17) and are consistent with observations made decades ago (18). Therefore, we propose that studies on candiduria should either employ fungal urine culture or incorporate diagnosis of candiduria by microscopic visualization, which would only identify only patients with CFU above 104/ mL.

Clinical studies on bacteriuric patients have defined “symptomatic” catheter related UTI as a positive urine culture (□104 CFU/mL) accompanied by any of the following symptoms: fever, urgency, frequency, dysuria, suprapubic tenderness, altered mental status, or hypotension (19). It is noteworthy that the defining clinical symptoms could not easily be ascertained in our patient population because they commonly had altered mental status and indwelling Foley catheters. Nevertheless, similar to other studies only few candiduric patients in our study regardless of how they were diagnosed exhibited symptoms such as fever (15%) and dysuria (2). Therefore the diagnosis “symptomatic” vs “asymptomatic” candiduria is not be useful. The significance of objective criteria such as leukocyturia has not been established in candiduric patients. High-level leukocyturia was detected in a small fraction of candiduric patients and was not different among those candiduric patients diagnosed by standard vs fungal culture.

We explored inflammatory markers in the urine of candiduric patients, because murine data demonstrates that host-pathogen interactions at the mucosal surface determine the outcome of urinary tract infection (20). Our goal was to determine if there was enough evidence to ultimately justify a larger multicenter prospective study to determine if inflammatory biomarkers could help identify the subgroup of candiduric patients that would benefit from treatment. We would expect such marker to exhibit an expression profile that is distinct from non-candiduric patients as well heterogenous in candiduric patients since the majority of patients are colonized and will not require treatment. In this study we chose not to explore Interleukin 1 and 8 because they are predominantly associated with presence of leukocyturia, which is rare in candiuric patients.

IgG was significantly higher in urine of candiduric patients when compared to levels in urines of control patients. In contrast, urine IgA levels did not significantly differ among candiduric and non-candiduric patients but were only detectable in two thirds of candiduric patients. While an increased IgG level was significantly and independently associated with candiduria, an increased IgA level was not. Both Westernblot results, and direct visualization of antibody coated yeast cells in urine demonstrate that IgGs are Candida specific and reflect current disease. The very high odds ratio for the association between an increased IgG level and candiduria in multivariate analysis adjusting for potential confounders is also consistent with that conclusion, Next, we explored IL-6. Induction of IL-6, an acute phase pro-inflammatory chemotactic cytokine that causes fever and malaise if systemic is strongly associated with UTI in both humans and mice (21–24). IL-6 levels have not been investigated in candiduric patients. Previous studies in children with bacterial urinary tract infections (25) have suggested that urinary levels of IL-6 are useful in differentiating between upper and lower urinary tract infection. In that clinical setting, a value >15 pg/mL was a strong indicator of acute pyelonephritis. Of note is that this study did not correct IL-6 levels for urine concentration, but compromised glomerular filtration rate may be less of a problem in tchildren. Our data indicate that urine concentration varies greatly in the elderly patient population. Our study documented elevated IL-6 expression in a subset of candiduric patients but was not limited to patients with leukocyturia or indwelling Foley catheters. Nevertheless, although with a lower odds ratio than for IgG or IL-17, an increased IL-6 level was significantly and independently associated with candiduria.

IL-17 has emerged as an immunomodulatory cytokine that plays a role in both arms of the immune system. IL-17 acts by indirectly enhancing neutrophil migration to infected tissue (26). Although the exact microbe-associated molecular patterns that trigger secretion of IL-17 are not defined, TLR-related signaling pathways are implicated (27). Aside from being secreted by CD4+ Th17 helper cells, other cell types have been reported to secrete IL-17 including cytotoxic T cells, iNK T cells, neutrophils, eosinophils, and monocytes (28). IL-17 or the IL-17 receptor has been shown to play a critical role in diverse bacterial infections (29–31), fungal (27, 32–36), and viral (37) infection. Recently IL-17 has also been implicated in the pathogenesis of uropathogenic Escherichia coli mediated UTI infection in a murine model (38). In this pilot study significantly levels of IL-17 were detected in urine of a subset of candiduric patients, whereas the majority of control patients had no detectable levels in urine. In multivariate analysis an increased IL17 level remained highly and significantly associated with candiduria.

Our study was not powered to determine if differences of inflammatory response in the host predict the outcome of candiduria. Data from this pilot study should encourage efforts to pursue larger prospective studies. Such studies would have to be carefully planed and incorporate differences in urinary concentration in elderly patients and also fungal burden, because both are highly variable. Decision-making in critically ill patients with candiduria is important (39), because candiduria may be the only indication for invasive candidemia and prolonged length of stay is even documented for non-invasive candidiasis (40). In addition, inadequate diagnostic criteria may lead to mislabeling of colonization as nosocomial infection. Precise outcome criteria, accurate diagnostic inclusion criteria and creatinine adjusted cytokine analysis may ultimately allow us to differentiate between candiduria that causes disease and should be treated versus colonization that causes no damage to the host and does not warrant further intervention.

Fig 1.

a. demonstrates significant differences in urine IgG levels in candiduric and non candiduric patients but no differences in IgA levels (b). c. and d. Quantification of IL-17 and IL-6 by ELISA demonstrated significant higher levels in candiduric patients.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by NIH 2 RO1 AI059681-06, R21AI087564-01, AI-067665 to J.M.A. and T32 AI 07506 to X.W and in part by pilot funds from the Einstein-Montefiore Center for AIDS NIH AI-51519.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest none

References

- 1.Richards MJ, Edwards JR, Culver DH, Gaynes RP. Nosocomial infections in pediatric intensive care units in the United States. National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance System. Pediatrics. 1999;103(4):e39. doi: 10.1542/peds.103.4.e39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Richards MJ, Edwards JR, Culver DH, Gaynes RP. Nosocomial infections in combined medical-surgical intensive care units in the United States. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2000;21(8):510–5. doi: 10.1086/501795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kauffman CA, Vazquez JA, Sobel JD, Gallis HA, McKinsey DS, Karchmer AW, et al. Prospective multicenter surveillance study of funguria in hospitalized patients. The National Institute for Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) Mycoses Study Group. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30(1):14–8. doi: 10.1086/313583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alvarez-Lerma F, Nolla-Salas J, Leon C, Palomar M, Jorda R, Carrasco N, et al. Candiduria in critically ill patients admitted to intensive care medical units. Intensive Care Med. 2003;29(7):1069–76. doi: 10.1007/s00134-003-1807-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sobel JD. Management of asymptomatic candiduria. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 1999;11(3–4):285–8. doi: 10.1016/s0924-8579(99)00031-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Safdar N, Slattery WR, Knasinski V, Gangnon RE, Li Z, Pirsch JD, et al. Predictors and outcomes of candiduria in renal transplant recipients. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40(10):1413–21. doi: 10.1086/429620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bougnoux ME, Kac G, Aegerter P, d'Enfert C, Fagon JY. Candidemia and candiduria in critically ill patients admitted to intensive care units in France: incidence, molecular diversity, management and outcome. Intensive Care Med. 2008;34(2):292–9. doi: 10.1007/s00134-007-0865-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ang BS, Telenti A, King B, Steckelberg JM, Wilson WR. Candidemia from a urinary tract source: microbiological aspects and clinical significance. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;17(4):662–6. doi: 10.1093/clinids/17.4.662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sobel JD, Kauffman CA, McKinsey D, Zervos M, Vazquez JA, Karchmer AW, et al. Candiduria: a randomized, double-blind study of treatment with fluconazole and placebo. The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) Mycoses Study Group. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30(1):19–24. doi: 10.1086/313580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pappas PG, Kauffman CA, Andes D, Benjamin DK, Jr., Calandra TF, Edwards JE, Jr., et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of candidiasis: 2009 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48(5):503–35. doi: 10.1086/596757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen SC, Tong ZS, Lee OC, Halliday C, Playford EG, Widmer F, et al. Clinician response to Candida organisms in the urine of patients attending hospital. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2008;27(3):201–8. doi: 10.1007/s10096-007-0427-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Colodner R, Nuri Y, Chazan B, Raz R. Community-acquired and hospital-acquired candiduria: comparison of prevalence and clinical characteristics. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2008;27(4):301–5. doi: 10.1007/s10096-007-0438-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jain N, Kohli R, Cook E, Gialanella P, Chang T, Fries BC. Biofilm formation by and antifungal susceptibility of Candida isolates from urine. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73(6):1697–703. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02439-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen LC, Goldman DL, Doering TL, Pirofski L, Casadevall A. Antibody response to Cryptococcus neoformans proteins in rodents and humans. Infect Immun. 1999;67(5):2218–24. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.5.2218-2224.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown AJ, Odds FC, Gow NA. Infection-related gene expression in Candida albicans. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2007;10(4):307–13. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2007.04.001. Epub 2007/08/21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Naglik JR, Rodgers CA, Shirlaw PJ, Dobbie JL, Fernandes-Naglik LL, Greenspan D, et al. Differential expression of Candida albicans secreted aspartyl proteinase and phospholipase B genes in humans correlates with active oral and vaginal infections. J Infect Dis. 2003;188(3):469–79. doi: 10.1086/376536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kauffman CA, Fisher JF, Sobel JD, Newman CA. Candida urinary tract infections--diagnosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(Suppl 6):S452–6. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir111. Epub 2011/04/22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ahearn DG, Jannach JR, Roth FJ., Jr. Speciation and densities of yeasts in human urine specimens. Sabouraudia. 1966;5(2):110–9. doi: 10.1080/00362176785190201. Epub 1966/10/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cope M, Cevallos ME, Cadle RM, Darouiche RO, Musher DM, Trautner BW. Inappropriate treatment of catheter-associated asymptomatic bacteriuria in a tertiary care hospital. Epub 2009/03/19. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48(9):1182–8. doi: 10.1086/597403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hannan TJ, Mysorekar IU, Hung CS, Isaacson-Schmid ML, Hultgren SJ. Early severe inflammatory responses to uropathogenic E. coli predispose to chronic and recurrent urinary tract infection. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6(8):e1001042. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001042. Epub 2010/09/03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hedges S, Anderson P, Lidin-Janson G, de Man P, Svanborg C. Interleukin-6 response to deliberate colonization of the human urinary tract with gram-negative bacteria. Infect Immun. 1991;59(1):421–7. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.1.421-427.1991. Epub 1991/01/01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Godaly G, Hang L, Frendeus B, Svanborg C. Transepithelial neutrophil migration is CXCR1 dependent in vitro and is defective in IL-8 receptor knockout mice. J Immunol. 2000;165(9):5287–94. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.9.5287. Epub 2000/10/25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Man P, van Kooten C, Aarden L, Engberg I, Linder H, Svanborg Eden C. Interleukin-6 induced at mucosal surfaces by gram-negative bacterial infection. Infect Immun. 1989;57(11):3383–8. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.11.3383-3388.1989. Epub 1989/11/01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mysorekar IU, Mulvey MA, Hultgren SJ, Gordon JI. Molecular regulation of urothelial renewal and host defenses during infection with uropathogenic Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(9):7412–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110560200. Epub 2001/12/18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Manzano-Gayosso P, Hernandez-Hernandez F, Zavala-Velasquez N, Mendez-Tovar LJ, Naquid-Narvaez JM, Torres-Rodriguez JM, et al. Candiduria in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients and its clinical significance. Candida spp. antifungal susceptibility. Rev Med Inst Mex Seguro Soc. 2008;46(6):603–10. Candiduria en pacientes con diabetes mellitus tipo 2. Sensibilidad antifungica in vitro. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hartupee J, Liu C, Novotny M, Li X, Hamilton T. IL-17 enhances chemokine gene expression through mRNA stabilization. J Immunol. 2007;179(6):4135–41. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.6.4135. Epub 2007/09/06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van de Veerdonk FL, Marijnissen RJ, Kullberg BJ, Koenen HJ, Cheng SC, Joosten I, et al. The macrophage mannose receptor induces IL-17 in response to Candida albicans. Cell Host Microbe. 2009;5(4):329–40. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.02.006. Epub 2009/04/22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bettelli E, Korn T, Oukka M, Kuchroo VK. Induction and effector functions of T(H)17 cells. Nature. 2008;453(7198):1051–7. doi: 10.1038/nature07036. Epub 2008/06/20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hamada S, Umemura M, Shiono T, Tanaka K, Yahagi A, Begum MD, et al. IL-17A produced by gammadelta T cells plays a critical role in innate immunity against listeria monocytogenes infection in the liver. J Immunol. 2008;181(5):3456–63. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.5.3456. Epub 2008/08/21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shibata K, Yamada H, Hara H, Kishihara K, Yoshikai Y. Resident Vdelta1+ gammadelta T cells control early infiltration of neutrophils after Escherichia coli infection via IL-17 production. J Immunol. 2007;178(7):4466–72. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.7.4466. Epub 2007/03/21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Umemura M, Yahagi A, Hamada S, Begum MD, Watanabe H, Kawakami K, et al. IL-17-mediated regulation of innate and acquired immune response against pulmonary Mycobacterium bovis bacille Calmette-Guerin infection. J Immunol. 2007;178(6):3786–96. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.6.3786. Epub 2007/03/07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huang W, Na L, Fidel PL, Schwarzenberger P. Requirement of interleukin-17A for systemic anti-Candida albicans host defense in mice. J Infect Dis. 2004;190(3):624–31. doi: 10.1086/422329. Epub 2004/07/10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Conti HR, Shen F, Nayyar N, Stocum E, Sun JN, Lindemann MJ, et al. Th17 cells and IL-17 receptor signaling are essential for mucosal host defense against oral candidiasis. J Exp Med. 2009;206(2):299–311. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zelante T, Bozza S, De Luca A, D'Angelo C, Bonifazi P, Moretti S, et al. Th17 cells in the setting of Aspergillus infection and pathology. Med Mycol. 2009;47(Suppl 1):S162–9. doi: 10.1080/13693780802140766. Epub 2008/07/09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bozza S, Zelante T, Moretti S, Bonifazi P, DeLuca A, D'Angelo C, et al. Lack of Toll IL-1R8 exacerbates Th17 cell responses in fungal infection. J Immunol. 2008;180(6):4022–31. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.6.4022. Epub 2008/03/07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zelante T, De Luca A, Bonifazi P, Montagnoli C, Bozza S, Moretti S, et al. IL-23 and the Th17 pathway promote inflammation and impair antifungal immune resistance. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37(10):2695–706. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737409. Epub 2007/09/28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hamada H, Garcia-Hernandez Mde L, Reome JB, Misra SK, Strutt TM, McKinstry KK, et al. Tc17, a unique subset of CD8 T cells that can protect against lethal influenza challenge. J Immunol. 2009;182(6):3469–81. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0801814. Epub 2009/03/07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sivick KE, Schaller MA, Smith SN, Mobley HL. The innate immune response to uropathogenic Escherichia coli involves IL-17A in a murine model of urinary tract infection. J Immunol. 2010;184(4):2065–75. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902386. Epub 2010/01/20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hollenbach E. To treat or not to treat - critically ill patients with candiduria. Mycoses. 2008;51(Suppl 2):12–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2008.01570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Slavin M, Fastenau J, Sukarom I, Mavros P, Crowley S, Gerth WC. Burden of hospitalization of patients with Candida and Aspergillus infections in Australia. Int J Infect Dis. 2004;8(2):111–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2003.05.001. Epub 2004/01/21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]