Abstract

This article discusses the successful process used to assess the feasibility of implementing the Family Matters program in Bangkok, Thailand. This is important work since adopting and adapting evidence based programs is a strategy currently endorsed by leading prevention funding sources, particularly in the United States. The original Family Matters (Bauman 2001) consists of four booklets designed to increase parental communication with their adolescent children in order to delay onset of or decrease alcohol, tobacco, and other drug use. As part of the program, health educators contact parents by telephone to support them in the adoption of the program. Each booklet addresses a key aspect of strengthening families as well as protecting young people from unhealthy behaviors related to alcohol and other drug use. Adaptation of the program for Bangkok focused on cultural relevance and the addition of a unit targeting adolescent dating and sexual behavior. One hundred and seventy families entered the program, with the majority (85.3%) completing all five booklets. On average, the program took 16 weeks to complete, with families reporting high satisfaction with the program. This article provides greater detail about the implementation process and what was learned from this feasibility trial.

BACKGROUND

Thailand has undergone a shift from an agrarian society to one that features thriving cities that offer employment in the manufacturing and tourism sectors. As a result, youth are experiencing a “dual value system” (Vuttanont, Greenhalgh, Griffin, & Boynton, 2006, p. 2072) where they are embracing modernization while still expected to honor the values, practices and expectations of tradition Thai culture. As reported in other publications from this study (Miller et al., under review; Chamratrithirong et al, 2009) Thai adolescents lifetime alcohol use (outside of family celebrations), is 23% among 13–14 year old youth. This is similar to the rate of lifetime alcohol use among youth in the United States (US) where 23.8% reported lifetime use prior to 13 years old (Centers for Disease Control, 2007). Rate of sexual initiation in Thailand among 13–14 year old adolescents is 2%, significantly lower than the 7.1% figure in the US (Centers for Disease Control, 2008). These findings indicate that it is still possible to tap families to intervene with young adolescents to delay initiation of such risk behaviors. The family remains the primary unit of support and is the single most important force for youth in defining identity and forming values (Vichit-Vadakan, 1994).

Thai parents do not embrace modern views of sexuality (Vuttanont et al., 2006) or accept practices of adolescent substance use, including alcohol (Assanangkornchai, Mukthong, & Intanont, 2009). In studies with Thai families looking at the relationship between parental communication and adolescent sexual risk behavior, the importance of this interaction is significant (Allen et al., 2003; Isarabhakdi, 1999). Parental communication and control reduces the likelihood that child will engage in sex. However, communicating their beliefs and values about these topics requires a skill set that many parents do not possess. Thus, it is no surprise they express great reluctance in introducing such topics.

To the end of supporting parents in addressing such issues with children, the research team has adapted an evidence-based alcohol, tobacco and other drug (ATOD) intervention developed in the US for implementation in Bangkok, Thailand. Because HIV poses such a serious health threat, one method to expedite getting efficacious interventions into the field for replication trials has been to adopt and culturally adapt existing programs that have been shown to reduce risky or encourage safer sexual behaviors. McKay and colleagues adapted and tested the CHAMP family-based program in KwaZulu-Natal, a predominantly Zulu speaking province. Cupp and colleagues (2007) also successfully merged and adapted elements of Reducing the Risk (Barth, 1996) and Amazing Alternatives (Perry, 1996) to produce a school-based program for testing in the same province. Also an NIH-funded team modified, implemented and tested Kelly's peer opinion leader model intervention in China, India, Peru, Russia, and Uganda (NIMH, 2010). Thus, it has been demonstrated that it is possible to adapt programs to be suitable in international settings as a strategy to save time and resources in intervention development.

In keeping with current recommendations to adapt and adopt evidence-based programs, we elected to begin with the Family Matters program, which targets key parent and adolescent risk and protective behaviors that this study has been funded to examine (Bauman et al, 2001). Family Matters addresses ATOD use among adolescents by utilizes fundamental concepts of public health such as the promotion of healthy lifestyles and risk protection through ecological or environmental change. (Byrnes et al 2010). Its key underlying theories are social learning theory, social control theory, and the theory of reason actions. This conceptual model suggests that behavioral effects will be brought about through intervening at two levels (family and adolescent). Specific variables addressed include parental role modeling of alcohol use; the attitudes parents express to children about drinking and engaging in risky sexual behavior; and the setting and monitoring of family rules about risky behaviors and parental monitoring for clues of adolescent alcohol use and risky sexual behavior.

In this paper we discuss issues and procedures relating to this program's implementation. There are three indicators of successful program implementation included in this paper: proportion of families that engaged in the intervention; proportion of families that completed all materials; and qualitative assessments of the program as provided by participating families.

METHODS

Materials Development

Family Matters relies on distributing booklets which support parents in communicating with adolescents about ATOD risk behaviors. For this feasibility study it was necessary to develop a set of culturally appropriate materials in the Thai language. Once the program's four booklets were translated into Thai, they were presented to thirteen focus groups (eight parent groups, five adolescent groups). These groups reviewed each booklet, engaged in selected activities and advised on the appropriateness of language usage, readability and activities. The materials were revised in Thai to reflect the focus groups' input and back-translated to English for final review by project staff prior to printing the final Thai versions.

After examining the existing literature on sexual risk-taking prevention programs for adolescents in Thailand and statements of need for this type of intervention from parents in our focus groups, we elected to develop an additional booklet that draws on the same principles as in the original four booklets, but focuses on issues of dating, sexual decision making and risk behaviors. Due to space considerations, we are not able to fully treat the development of this booklet here but will do so in a forthcoming manuscript (Cupp et al).

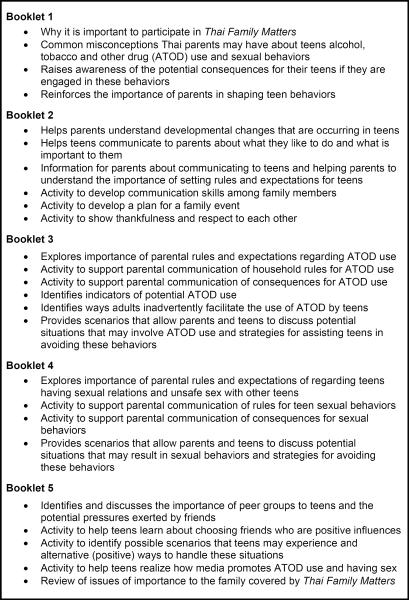

The booklets are designed to facilitate on-going family communication; increase awareness of how teen development affects behaviors and risks; encourage the development of family rules about adolescent ATOD use and sexual activity; and provide support to parents for guiding youth. Figure 1 provides an overview of each booklet's key components.

Figure 1.

THAI FAMILY MATTERS individual booklets' key components

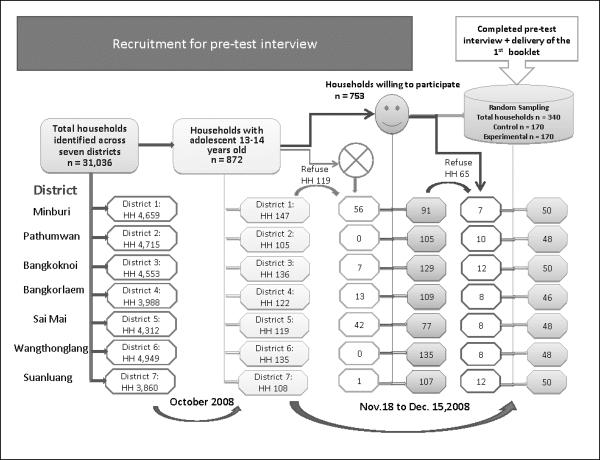

Family Recruitment and Retention

Families were recruited to participate in the research study at the point of the pre-test. Using the probability proportional to size sampling method, 420 families were randomly and proportionally sampled from Bangkok. Families were sampled from seven districts. Thirty-five blocks from each district were sampled, which led to a total of 245 blocks and 4,000 households in each district (31,036 across seven districts). Households with adolescents 13–14 years old were identified by data collection teams who conducted household census and enumerations in each block. (Byrnes et al: 2009). A total of 340 families were recruited with half randomly assigned to an experimental or control condition. Figure 2 shows the total of households in each district; the number of households with adolescents aged 13–14 and the number of households randomly assigned to the experimental and control groups.

Figure 2.

Recruitment for pre-test interview

Research staff called mothers in each household to schedule an appointment to administer the baseline assessment to the mother and her 13–14 year old child. Mothers were chosen as the point of contact since traditionally they have assumed primary responsibility for dealing with children's health- and social-related issues, regardless of the child's gender (Sunthorntada, 2001; Thompson, 2000). This fact was reaffirmed by the mothers we interviewed as they overwhelmingly identified themselves the primary support giver for their children in addressing such issues.

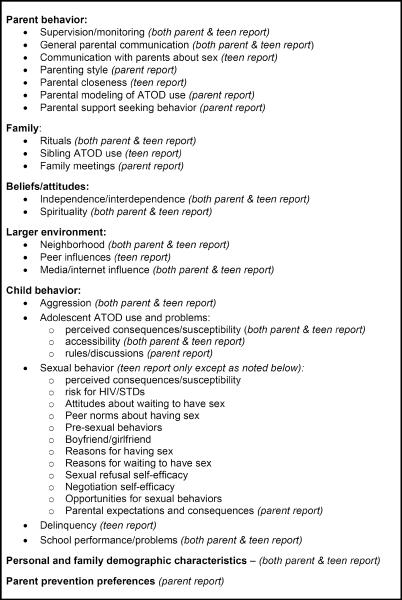

One-hour, person-to-person interviews were conducted privately with mothers and with adolescents. Informed consent for participation was given in writing for all participants, with parents signing on behalf of children. In addition, children also signed an assent form indicating their desire to participate. Figure 3 presents the key survey domains for parents and teen participants.

Figure 3.

Thai Family Matters survey domains

The data collectors explained the objectives of the research study and, for the experimental condition, provided an overview of TFM. A total of 872 mothers were given the TFM overview and 86% (n=753) indicated that they would be willing to participate in the intervention if asked. Reasons mothers (n=119) gave for declining to participate in the study included: time limitations; a belief that their child was not developmentally ready for the program; discomfort with being in a study; and concerns that their lack of education would make it difficult to fully grasp the materials.

After the first assessment, respondents in the experimental and control condition received an incentive ($30 parents, $10 youth). Families in the experimental condition also received the first program booklet and a welcome letter. Data collection staff asked that mothers read through the booklet in the upcoming week and informed them that a member of the project's health educator team would call within two days to welcome them to the program and to answer any questions. Participants were told that each subsequent booklet would be mailed to them upon completion of the prior booklet and that a health educator would call them upon completion of each booklet to discuss their experience. They were also informed that, six-to-nine months after the completion of this initial assessment, data collectors would contact them to conduct another assessment with both parent and children participants.

Staff Orientation, Training and Supervision

Providing Staff Orientation and Training

In order to adequately support parents, track key interactions and log important data for study purposes, a full-time and part-time health educator were trained three months prior to the program's launch. It was the shared opinion of the family participants and the study team that the health educators played a significant role in ensuring a successful implementation.

The training for the health educators provided an overview of duties, a review of individual booklets, and discussion about key program issues (confidentiality, motivating parents and facilitating referrals for services). The health educators were shown how to conduct calls to participants, how a fidelity rating system would be used to monitor the quality of calls, and what forms and procedures would be used to track progress. In addition, health educators were required to complete a recognized US human subjects training.

In a post-implementation debriefing interview with senior staff, health educators reported that program training was key to their success by providing them with the knowledge, skills and confidence to successfully facilitate the program's implementation.

Developing Implementation Protocols and Supporting Materials

Another key factor which contributed to the successful implementation of TFM was that senior staff worked with health educators to develop clear protocols and weekly work plans and to provide for monitoring of important mechanisms. For example, a program database was used to track the frequency and length of calls to participants which were estimated at a ratio of five calls for every completed booklet; however, not all calls involved conversations – some did not connect or received a busy signal.

Providing Ongoing Staff Supervision

Periodic reviews of live and recorded phone interviews were conducted by a team of senior staff to assess the fidelity of each call using a standard rating system. These fidelity ratings allowed staff to measure consistency between the two health educators' performance as well as adherence to the phone interview scripts. The fidelity ratings indicated consistency in both delivery and adherence to the phone protocols (adherence 89.7%, quality 92.8%, overall fidelity 92.2%). Inter-rater reliability consensus equaled 99.05%. This high level of reliability is reflective of the fact that health educators were well-trained in the program's protocol and each demonstrated strong fidelity to the program's established implementation practices. Also, the ratings were done by two senior staff so variance of individual perspectives was limited. Finally, the fidelity rating form employed a three item scale which further contributed to a high inter-rater reliability consensus.

In addition, one senior staff member was assigned the role of program intervention supervisor. This staff member met with the health educators weekly throughout the implementation phase in order to discuss adherence to established program practices, assess progress and support skills development.

RESULTS

The Thai Family Matters program (TFM) was offered to 170 families (49.4% male adolescents, 50.6% female) from November 7, 2008 – April 30, 2009. In order to stagger program participation (and need for program staff support), three cohorts with different start dates were used. Of the 170 families assigned to the experimental group, 145 (85%) completed the entire program.

Impact of Materials

Upon completion of the implementation process, parents and teens completed written post-surveys (approximately 115 and 140 items respectively). In addition 19 parents and 19 teens participated in four focus groups designed to gain a deeper understanding of families' experiences with the program. The manner in which the materials were delivered appeared to have a positive influence on participants. Families reported that having the first booklet personally delivered to them created a sense that this was an important program and their participation was valued. The fact that subsequent booklets were mailed individually was also regarded positively by many participants who noted that they would have felt overwhelmed by the length of the materials if they had received all the booklets at the onset.

The program's health educators conducted follow-up calls with participating parents upon completion of each booklet (using a guided script and live-entry tracking database). In these calls, the parents reported overall satisfaction with the booklets, stating that they enjoyed and benefitted from each. They also noted that the booklets helped them understand the importance of communicating with their children as opposed to bossing or punishing them.

Parents also noted that they particularly enjoyed exercises which provided opportunities to share with children what it was like when they were teenagers.

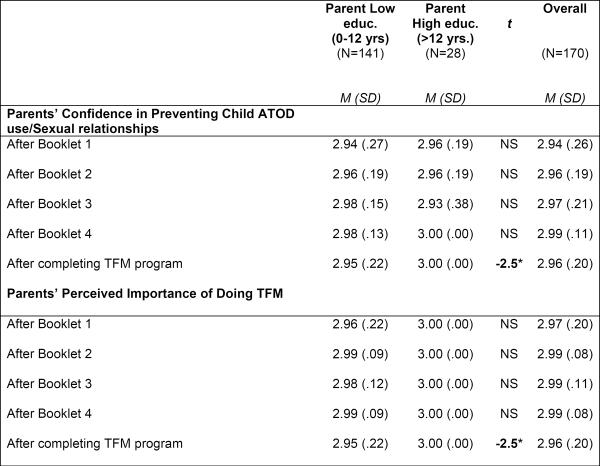

An overwhelming majority of mothers who participated in the program expressed more confidence in addressing ATOD use and sexuality with children upon completion of the program. When rating confidence in discussing the issues addressed in each booklet (using a scale of 1=less, 2=about the same, and 3=more), parent ratings ranged from 2.94 to 2.99. The overall rating for all five booklets combined was 2.96.

With regards to the importance of addressing the issues presented, parents were asked if completing the booklet affected the degree to which they felt it was important to address the topics discussed in each. Working with the same scale used in the confidence rating, parent responses for individual booklets ranged from 2.96 to 2.99, with an overall rating for all five booklets of 2.98. In all instances related to these two measures, there were no differences reported for parents of boys or girls. Figure 4 presents a summary of data on parent confidence and importance of utilizing TFM.

Figure 4.

Parents' report of confidence & importance of using TFM upon completion of booklet

Note. Confidence and importance ratings were 1=less,2=about the same, 3=more.

*p<.05

Parents reported a high degree of satisfaction with all of the booklet's specific activities. Of the total 20 activities included in the five booklets, 19 activities were rated on a likability scale within a range of 3.54 to 3.74 (scale of 1 = “not at all” and 4 = “a lot”). The one activity that fell outside this range with a rating of 3.14 focused on creating family rules for ATOD.

Effectiveness of Implementation Process

Health educators reported the majority of parents demonstrated a strong commitment to completing each booklet in the recommended two-week time allotment. Of the 170 families who entered the program all completed at least Booklet One. Of the 85.3% of the study's parents who completed all five booklets, completion rates for the program's twenty key activities was 99.97%. In addition, when families were informed that the implementation process was coming to an end, many re-doubled their efforts to ensure that they would complete the remaining program materials within the timeframe.

Finally the relationship between participating parents and the health educators appears to have contributed to the program's successful implementation. Throughout the implementation, health educators reported that their rapport with participants deepened. This observation was based on increases in the average length of calls as well as parents' willingness to self-disclose. It was also noted that mothers reported that they looked forward to the calls and regarded the health educators as valuable resources for their family. Although this increased demand for staff time, the health educators believed they were able to maintain a balance between providing each family the attention they required and moving forward each cohort to a successful completion of the program (evidenced by the high completion rate).

Parent and Adolescent Characteristics

Parent Characteristics

Several parent characteristics were identified as bearing on the program's implementation. Health educators commented that parents who were better educated were more likely to report satisfaction with program materials as well as assess overall impact positively. This was confirmed by satisfaction ratings collected during health educator phone calls with parents upon completion of each booklet. Parents with high levels of education (> 12 years) reported that they were more confident that could prevent their child's ATOD use (t = −2.5, p < .05) than were parents with lower levels of education. Similarly, after completion of the program, more educated parents were more likely to report that TFM was more important to do than less educated parents (t = −2.5, p < .05; highly educated parents: M = 3.0, SD = 0.0; less educated parents: M = 2.95, SD = .22). One reason for this difference could be differences in reading ability and comfort.

Another issue that may have affected satisfaction was the comfort level in completing the program activities. A few of the parents in the study stated that they did not have the knowledge or confidence to conduct some program activities; a general apprehension to talk about sensitive issues with children may have also played a role.

Adolescent Characteristics

A number of adolescent characteristics were identified as potentially having an effect on the implementation process. Youth in this age range (13–14) reported significantly less risk behavior related to ATOD or sex than Western counterparts, particularly in the US where the original program was developed and tested. This resulted in a few parents (2%) declining participation because of their beliefs about their child's behavior and the developmental appropriateness of the intervention. It also influenced the nature of the adaptations made to the intervention to make it culturally relevant for the Thai population.

DISCUSSION

The overarching goal of this study was to determine whether, with appropriate cultural modifications, implementing Family Matters in Thailand was feasible. This paper presents substantial evidence that this program designed to prevent adolescent risk behaviors, including substance use and sexual activity, was successfully implemented in Bangkok, Thailand. An indicator of the success of this feasibility trial is the finding that 86% of the mothers agreed to participate in the study when initially asked. Of those assigned to the experimental condition, 85.3% completed all five booklets and all families in the experimental condition completed at least one booklet. This rate of participation and compliance is quite high. These results are impressive given that our study required completion of five booklets rather than four as in the original US program. In the US-based implementation study of Family Matters, 658 families engaged in the program. Of these, 83.4% (n=549) completed at least Booklet One while 61.8% (n=407) completed all four booklets. While participation is important, and indeed a necessary precursor to establish that the program had any impact on the study population, a second indicator of successful implementation was the degree of satisfaction exhibited by families who participated. Mothers indicated that they felt much more confident in discussing these sensitive upon completion of the program. These quantitative ratings were further substantiated by the open-ended responses mothers gave to the health educators, indicating their enthusiasm for the program and the importance of the program to their relationship with their teen.

Finally, assessments of the health educators and the interviewers for the research study indicated that the study overall was well-received and respected. As one parent noted, participating “was like having my own private psychologist to help me.”

Challenges

This study was implemented with very few disruptions, a tribute to willingness of the study population and the dedication of the health educators. However, we did note that it is difficult to find a contiguous block of time in Thailand when there are no major holidays which disrupt families' schedules. While this may be viewed as a potential impediment to the implementation of an intervention (from a scientific perspective), holiday periods may actually offer families time and motivation to discuss important topics. For example, we experienced slight delays in completion of booklets that were distributed during the New Year's periods (Western, Chinese and Thai). However, given that a new year often provokes the desire for change, the intervention could be positioned as a tool to help families do so. In addition, the global financial downturn might have resulted in parents' need to work harder in order to make ends meet, decreasing the available time at home for family activities. Finally, given the small sample size in this pilot feasibility study, we were not able to control for the affects of neighborhood factors or the educational levels of participating families. A larger efficacy trial would allow for consideration of these factors.

CONCLUSION

Given that this feasibility study of TFM reveals excellent completion rates and high levels of satisfaction by families, the next step is to conduct a full-scale randomized controlled trial. This will allow us to determine if changes in family practices result in significantly better short and long-term outcomes for program participants. Ultimately, if the intervention significantly changes families and results in positive outcomes for youth, this program could provide Thai families with a low-cost prevention initiative.

Acknowledgments

Research for and preparation of this manuscript was supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Alcoholism and Alcohol Abuse (Grant No. AA015672, Pamela K. Cupp, Principal Investigator). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- Allen DR, Carey JW, Manopaiboon C, Jenkins RA, Uthaivoravit W, Kilmarx PH, van Griensven F. Sexual health risks among young Thai women: Implications for HIV/STD prevention and contraception. AIDS and Behavior. 2003;7(1):9–21. doi: 10.1023/a:1022553121782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assanangkornchai S, Mukthong A, Intanont T. Prevalence and patterns of alcohol consumption and health-risk behaviors among high school students in Thailand. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2009;33(12):2037–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.01043.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atwood K, Zimmerman R, Cupp PK, Vanderhoff KJ, Chamratrithirong A, Rhucharoenpornpanich O, Fongkaew W, Miller BA, Byrnes H, Rosati M. Correlates of Pre-Coital Behaviors, Intentions, and Sexual Initiation among Thai Youth. Manuscript resubmitted to Journal of Early Adolescence. under review. [Google Scholar]

- Barth R. Reducing the Risk: Building skills to prevent pregnancy, STD, and HIV. ETR Associates; Santa Cruz, CA: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Bauman KE, Foshee VA, Ennett ST, Hicks K, Pemberton M. Family Matters: A family-directed program designed to prevent adolescent tobacco and alcohol use. Health Promotion Practice. 2001;2(1):81–96. [Google Scholar]

- Bauman KE, Ennett ST, Foshee VA, Pemberton M, King TS, Koch GG. Influence of a Family-Directed Program on Adolescent Cigarette and Alcohol Cessation. Prevention Science. 2000;1(4):227–237. doi: 10.1023/a:1026503313188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrnes, et al. The Roles of Neighborhood Disorganization and Social Capital in Thai Adolescents' Substance Use and Delinquency. 2009. in review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrnes, et al. Implementation fidelity in adolescent family-based prevention programs: relationship to family engagement. Health Education Research. 2010;25(4):531–541. doi: 10.1093/her/cyq006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Youth Risk Behavioral Surveillance - United States 2007, Surveillance Summaries. MMWR. 2008;57(No.SS-4):21. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention YRBSS: 2007 National Youth Risk Behavior Survey Overview. 2007 Retrieved March 18, 2010, from http://www.cdc.gov/HealthyYouth/yrbs/pdf/yrbs07_us_overview.pdf.

- Chamratrithirong A, Rhucharoenpornpanich O, Chaiphet N, Rosati MJ, Miller BA, et al. Beginning the Thai Family Matters Project: An aerial analysis of bad neighborhoods and adolescents' problematic behaviors in Thailand. Journal of Population and Social Studies. 2009;18(1) Pub Med: NIHMS134961. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cupp P, Zimmerman R, Bhana A, Feist-Price S, Dekhtyar O, Karnell A, Ramsoomar L. Combining and adapting American school-based alcohol and HIV prevention programmes in South Africa: The HAPS project. Vulnerable Children and Youth Studies. 2008;3(2):134–142. [Google Scholar]

- Cupp P, Miller B, Atwood K, Fongkaew W, Chamratrithirong A, Rhucharoenpornpanich O, Byrnes H, Rosati M, Chookhare W. Adapting a primary prevention family-based intervention to reduce substance use and risky sexual behavior for implementation in Bangkok, Thailand. [Google Scholar]

- Isarabhakdi P. Factors associated with sexual behavior and attitudes of never-married rural Thai youth. Warasan Prachakon Lae Sangkhom. 1999;8(1):21–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperber E, McKay M, Bell C, Petersen I, Bhana A, Paikoff R. Adapting and disseminating a community-collaborative, evidence-based HIV/AIDS prevention programme: Lessons from the history of CHAMP. Vulnerable Children and Youth Studies. 2(3):150–158. doi: 10.1080/17450120701867561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller BA, Byrnes HF, Zimmerman RS, Cupp PK, Chamratrithirong A, Rhucharoenpornpanich O. Validation of a U.S. risk and protective framework for preventing ATOD use and delinquency in Thai adolescents. Manuscript resubmitted to Prevention Science. under review. [Google Scholar]

- NIMH Collaborative HIV/STD Prevention Trial Group Results of the NIMH collaborative HIV/sexually transmitted disease prevention trial of a community popular opinion leader intervention. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome. 2010;54(2):204–214. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181d61def. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry CL, Williams CL, Veblen-Mortenson S, Toomey TL, Komro KA, Anstine PS, McGovern PG, Finnegan JR, Forster JL, Wagenaar AC, Wolfson M. Project Northland: Outcomes of a communitywide alcohol use prevention program during early adolescence. American Journal of Public Health. 1996;86(7):956–965. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.7.956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunthorntada A. Power relations and reproductive health behaviours. In: Buppa Sirirassamee, Benja Yoddumnern- Attig, Gray AN., editors. Manual on the development of a gender-sensitive reproductive health programmes. Institute of Population and Social Research. Mahidol University; Nakhon Pathom: 2001. pp. 63–76. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson S. Sexual dimension: personal aspects. In: Yanrungsri Thongkorn, Fongsiri Thanapan, Sirisritrirak Ratri, Pawanaporn Wipa, Ngo Siriwan Sae, Phusitaporn Usa., editors. Summary of the 7th National Seminar on AIDS. Printing and religion; Bangkok: 2000. pp. 188–90. [Google Scholar]

- Vuttanont U, Greenhalgh T, Griffin M, Boynton P. “Smart boys” and “sweet girls”—sex education needs in Thai teenagers: a mixed-method study. The Lancet. 2006;368(9552):2072. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69836-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vichit-Vadakan J. Women and the family in Thailand in the midst of social change. Law and Society Review. 1994;28(3):515–524. [Google Scholar]