Abstract

A convenience sample of 234 colostral specimens, collected directly from the nursing bottle immediately prior to the first feeding, was studied. Samples originated from 6 farms and were collected over 24 months. Routine bacteriologic techniques were used to quantify the bacterial load of the colostrum, as well as to identify the bacteria. Overall, at least 1 microorganism was cultured from 221 colostral samples (94.4%). By using the upper tolerance level of 100 000 bacteria/mL, 84 samples (35.9%) were considered contaminated. Staphylococcus spp. (57.7%), gram-negative rods (47.9%), coliforms (44.0%), and Streptococcus uberis (20.5%) were among the most frequently isolated bacteria. The relative risk (RR) of contamination with more than 100 000 bacteria/mL was significantly greater in warm months [RR = 2.55, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.63 to 4.02] than in cool months and in colostrum offered to male calves (RR = 1.55, 95% CI: 1.09 to 2.20). Bacterial load was also associated with the farm of origin (P < 0.0001). When assessing colostrum management, one should consider bacterial contamination. Multiple factors are likely associated with the degree of contamination, and farm-specific factors may be important. Further studies are necessary to evaluate the impact of bacterial contamination of colostrum on neonatal health.

Introduction

Passive transfer of colostral immunoglobulins (Ig) is imperative for calf survival. Current recommendations for the feeding of colostrum to dairy replacement heifers suggest the use of a nursing bottle or esophageal tube (1). However, the collection, handling, and storage of colostrum introduce risks of microbial contamination. Collection is often by milking techniques that are different from routine hygienic practices for milking, instrumentation, and milk storage. Moreover, storage until the colostrum is fed to the calf may be at room temperature. In 1 study in a tropical environment, milk from term women could be stored for 6 h without a significant increase in bacterial counts, whereas colostrum could be stored for 12 h without significant bacterial growth (2); however, the bacterial contaminants represented normal skin flora, which may or may not be the case in bovine colostrum.

The quality of colostrum refers to its Ig concentration; as the quality increases, passive transfer of immunity, measured by calf serum Ig concentration, improves (3). There is little published information concerning bacterial contamination of colostrum and its potential impact on passive transfer of immunity and neonatal health. In one study, calves fed pasteurized colostrum and waste milk during the preweaning period experienced less morbidity and were 3.7 kg heavier at 180 d of age (4,5,6).

The objectives of this study were to describe the bacteria most frequently isolated from colostrum fed to newborn dairy calves in commercial dairy herds; to quantify the bacterial contamination of the colostrum; and to evaluate associations between bacteria in colostrum and the farm of origin, season of birth, calf gender, and dam parity.

Materials and methods

Origin of the samples

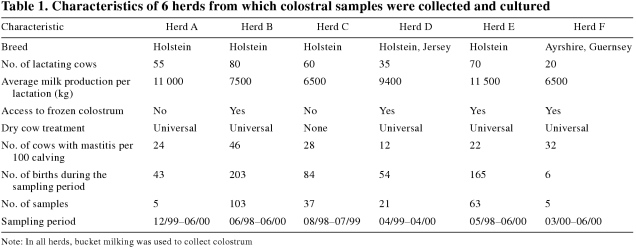

A convenience sample of 234 colostral specimens was obtained from dairy herds belonging to clients of a health surveillance program at the Clinique Vétérinaire St-Louis (CVSL)–Embryobec, St-Louis-de-Gonzague, Québec. Herd owners were recruited on the basis of their interest in participating in a research study on calf management. Six herds participated in the study over a 2-year period (May 1998 to June 2000). Each herd owner was asked to collect samples of colostrum being fed to all calves born during a specific period (Table 1). The sampling period varied among the herds. Relevant characteristics of the participating herds are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Colostrum sampling and bacteriologic analyses

Colostrum was collected by the dairy person with a 10-mL sterile syringe: 10 mL was taken directly from the nursing bottle immediately prior to the first feeding of the calf. Each sample was dated and marked with the calf and cow identification numbers. Samples were rapidly stored at –20°C before submission to the clinical bacteriology laboratory at the Faculté de médecine vétérinaire, Université de Montréal.

For bacteriologic testing, the samples were thawed and transferred to sterile plastic tubes. Two dilutions (1:10 and 1:100) of each specimen were prepared. For each dilution, 10 μL was plated onto trypticase soy agar (TSA; Difco, Detroit, Michigan, USA) with 5% bovine blood. The plates were incubated at 37°C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2. After 24 h of incubation, the different colony types were counted. Each colony type was subcultured on a TSA blood agar plate. The different bacteria were identified according to the routine procedures of the bacteriology laboratory and described procedures (7). In the absence of bacterial growth, plates were incubated for another 24 to 48 h.

Information recorded

For each calf enrolled in the study, the following data were recorded: herd of origin, date of birth, gender, dam identification, and dam parity (all levels of parity ≥ 5 were grouped). Months of birth were categorized as being warm or cold, on the basis of the average temperature, as recorded by Environment Canada. Cold months were those with an average temperature of 4°C or less (November, December, January, February, March) and warm months those with an average temperature greater than 4°C.

Definition of bacterial groups and bacterial count

Microorganisms were classified into 4 groups according to the probable origin of the contamination. Strictly mammary pathogens (MP) included Streptococcus uberis, S. dysgalactiae, and Staphylococcus aureus. Normal inhabitants of bovine skin and mucosa (NI) included Arcanobacterium pyogenes, Corynebacterium spp., Pasteurella spp., Streptococcus spp., Staphylococcus spp., and yeast. Fecal contaminants (FC) included Enterococcus spp., Streptococcus bovis, Proteus spp., Escherichia coli, and other coliforms (Klebsiella spp., Enterobacter spp.). Environmental contaminants (EC) included Micrococcus spp., Bacillus spp., and gram- negative rods (Acinetobacter spp., Pseudomonas spp., Flavobacterium spp.).

For each sample, the total bacterial count and individual counts for each bacterium cultured were recorded, as was a group count, obtained by adding the individual counts from all the bacteria belonging to a particular group.

Degree of contamination was categorized by using a cut-off of 100 000 bacteria/mL. This level is commonly used by the dairy industry for milk entering the processing plant. Group contamination was dichotomized by using an arbitrary level of 1000 bacteria/mL for all groups except the MP group, for which the contamination threshold was 1 bacterium/mL.

Statistical analyses

All statistics were computed on the logarithmic transformation of bacterial counts. Correlation coefficients between bacterial counts among the 4 defined bacterial groups were estimated. The proportion of samples contaminated with more than 100 000 bacteria/mL was compared between cold and warm months, between male and female calves, and between parity levels of the dams by using a Pearson chi-squared test. One-way analysis of variance was used to compare the average bacterial counts per sample for each month and each farm. Student's t-test was used to compare average bacterial counts in colostrum fed to male versus female calves. Relative risk (RR) was computed to compare the risk of colostrum being contaminated with more than 100 000 bacteria/mL in a warm month compared with a cold month and being fed to a bull calf compared with a heifer calf. A 95% confidence interval (CI) was calculated around the RR, assuming a normal distribution. The α level was set at 0.1.

Results

Over the 2-year period (May 1998 to June 2000), 234 colostral samples were cultured; 186 (79.5%) were from colostrum given to heifer calves. The distribution of samples among the dams was as follows: first lactation, n = 63; 2nd lactation, n = 70; 3rd lactation, n = 47; 4th lactation, n = 23; 5th lactation or more, n = 25; and unknown parity, n = 6.

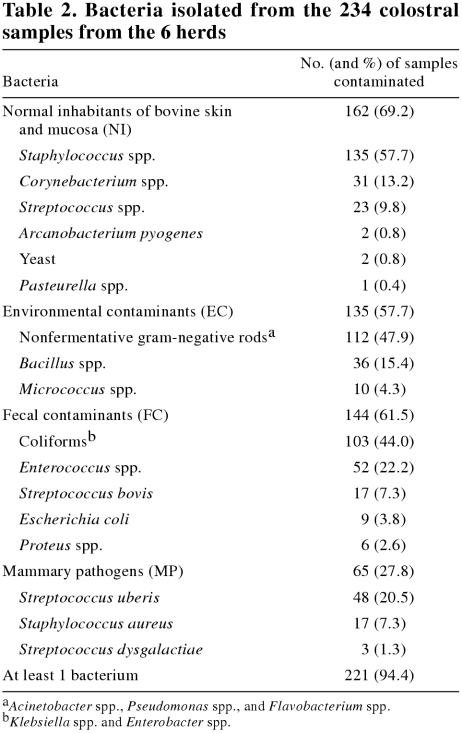

Overall, at least 1 species of microorganism was cultured from 221 colostral samples (94.4%). The total bacterial count for a sample ranged from 0 to 3 × 106 bacteria/mL. The average bacterial count was 2.3 × 104 (95% CI: 15 135 to 34 674) bacteria/mL, and 84 samples (35.9%) had more than 100 000. Table 2 identifies the microorganisms and the frequency with which they were cultured. The bacterial counts of FC were significantly correlated with the bacterial counts of EC (Pearson correlation coefficient = 0.25, P = 0.0001). All other group counts appeared to be independent from each other.

Table 2.

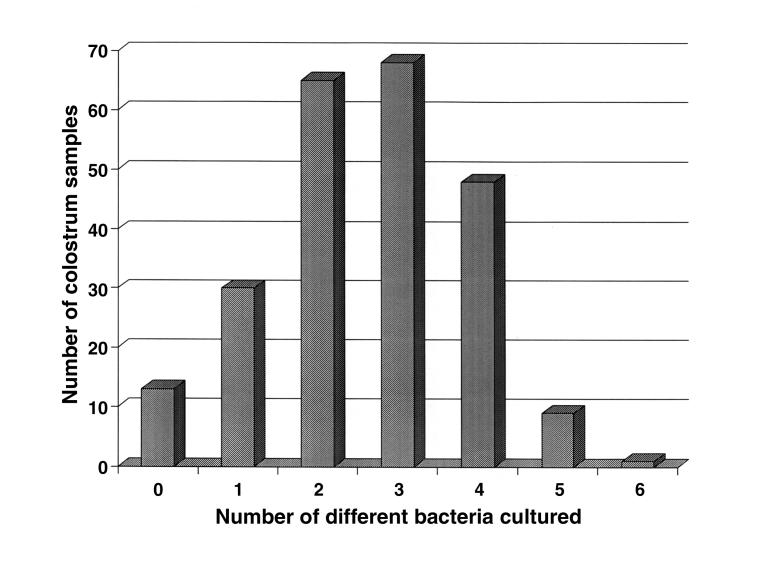

Up to 6 types of bacteria were cultured from a sample (Figure 1) and, most often, bacteria from more than 1 group (MP, NI, FC, or EC) were present. Ten samples had bacteria belonging to all 4 groups, 80 samples had bacteria from 3 groups, 95 samples had bacteria from 2 groups, 36 samples had bacteria from only 1 group, and 13 samples were sterile.

Figure 1. Distribution of the number of different bacteria cultured from colostral samples.

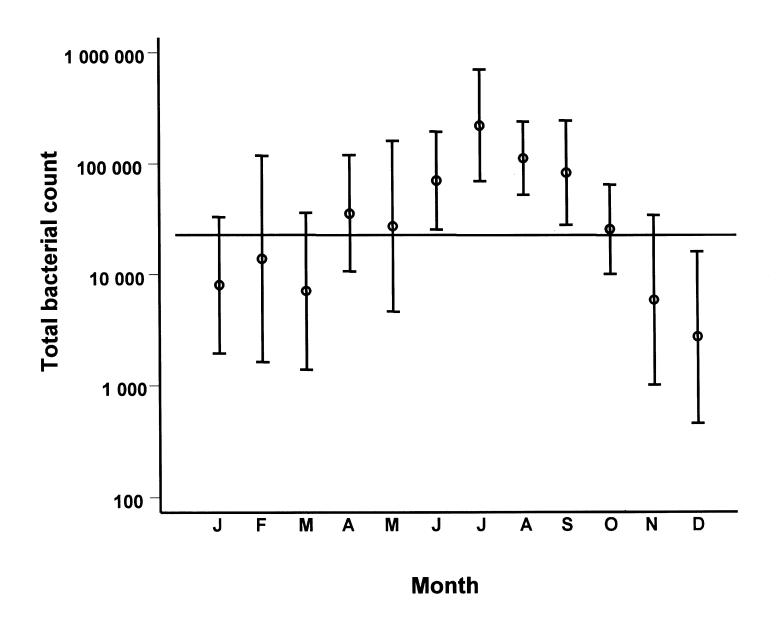

The count was above 100 000 bacteria/mL for 65 samples (27.8%) during warm months but only 18 (7.7%) samples during cold months (P < 0.001). The RR of being contaminated at this level during warm months compared with cold months was 2.55 (95% CI: 1.63 to 4.02) (Figure 2). The average group counts differed between cold and warm months only for FC and EC (MP: P = 0.23; NI: P = 0.54; FC: P < 0.0001; EC: P < 0.0001).

Figure 2. Total bacterial count per sample for each month of the year. Mean and 95% confidence interval.

The colostrum fed to bull calves was more often contaminated above 100 000 bacteria/mL than was the colostrum fed to dairy heifers (25.2% vs 10.3% of the samples, respectively; P = 0.02). The RR of being contaminated at this level was 1.55 (95% CI: 1.09 to 2.20) for colostrum fed to bull calves compared with that fed to heifer calves. The mean count of MP (P = 0.01) and NI (P = 0.03) was significantly higher for the colostrum fed to bull calves than for that fed to heifer calves.

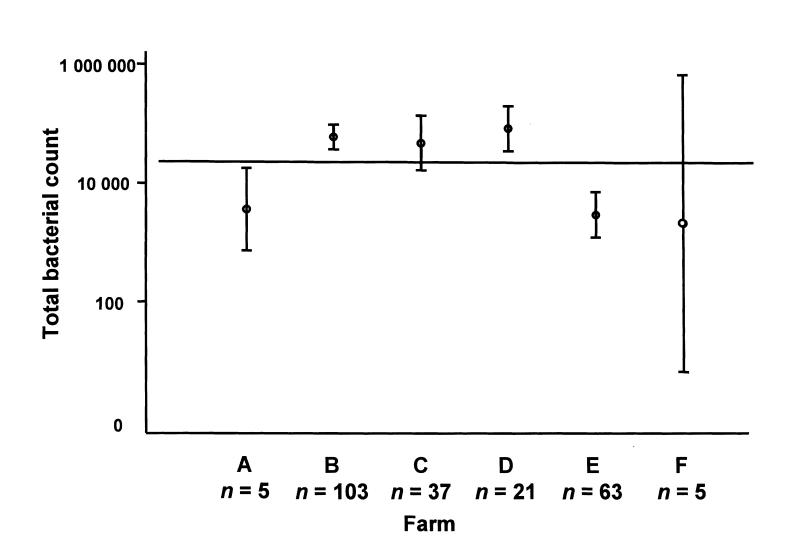

The mean bacterial count for farm E was significantly lower than the means for farms B, C, and D (Figure 3). The mean bacterial count for farm A was significantly lower than the means for farms B and D. The mean group counts were different among the farms except for MP (MP: P = 0.21; NI: P = 0.05; FC: P < 0.0001; EC: P = 0.0001).

Figure 3. Total bacterial count per sample for each of the 6 farms participating in the study. Mean and 95% confidence interval.

No difference (P = 0.87) was observed in the proportion of samples with more than 100 000 bacteria/mL among the parity groups. The group bacterial counts were also homogeneous among the parity groups (MP: P = 0.63; NI: P = 0.84; FC: P = 0.54; EC: P = 0.95).

Discussion

Bacterial contamination of colostrum was frequent in the farms studied (at least 1 type of microorganism was cultured from 94.4% of the samples). While extrapolation of the findings from this study to other farms should be done with caution, the participating herds seem to be representative of dairy farms in eastern Canada.

The magnitude of bacterial contamination of colostrum appeared to be important, with 35.9% of samples showing a count above 100 000 bacteria/mL. As many as 6 types of bacteria were cultured from a sample, and total counts were found to be as high as 3 × 106 bacteria/mL. The relationship between colostral bacterial contamination and calf morbidity and mortality remains to be studied. In one study, the benefits of pasteurization of colostrum on growth and morbidity was significant (4,5). These results are even more interesting, knowing that pasteurization of colostrum may have a detrimental effect on the immune system (8).

Multiple risk factors may have an effect on bacterial contamination. Most likely, general attention to hygiene provided by the calf feeder is important and may vary among farms. The farm personnel may change over time or may have less time, so that the level of contamination varies. In this study, male calves were at greater risk of being fed colostrum with a high bacterial count than were female calves. This suggests that there are differences in the level of care that is taken, depending on the value of the animal. The MP count was higher in colostrum offered to male calves, which may indicate that they received mastitic milk more often than did heifer calves.

Colostrum fed during warm months was contaminated more often than was colostrum fed during cold months. Delay between collection and feeding allows bacterial growth; this delay may have more impact during the warm months. Workload on a farm varies throughout the year, less time being available for calf care during the warm months. Nonetheless, the increased frequency of contamination during the warm months justifies the recommendation that colostrum be maintained at 4°C during summer.

Interestingly, group counts were not correlated, except for the FC and EC groups. Since fecal bacteria may arise directly from fecal material or indirectly from the immediate environment — which, in the cow, is often heavily contaminated with feces — these origins of contamination are likely confounded. Classifying bacteria according to probable origin may facilitate the understanding of the origin of contamination, as in the case of the bull calves, for which the MP group appeared to be responsible for the higher frequency of heavy contamination.

Parity was not associated with the total bacterial count or the group count. One could have hypothesized that heifers would have lower MP counts but higher FC counts, since they tend to be more refractory to milking procedure and may have a dirtier udder for the first few milkings. However, this was not demonstrated in this study.

When assessing colostrum management, one should consider bacterial contamination. Multiple factors are likely associated with the degree of contamination, and farm-specific factors may be important. Further studies are necessary to evaluate the impact on neonatal health. CVJ

Footnotes

This research was funded by Le Fonds du centenaire de la Faculté de médecine vétérinaire de St-Hyacinthe.

Address correspondence and reprint requests to Dr. Gilles Fecteau.

References

- 1.Esser TE, Gay CC, Pritchett L. Comparison of three methods of feeding colostrum to dairy calves. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1991;198: 419–422. [PubMed]

- 2.Nwankwo MU, Offor E, Okolo AA, Omene JA. Bacterial growth in expressed breast-milk. Ann Trop Paediatr 1988;8:92–95. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Morin DE, McCoy GC, Hurley WL. Effects of quality, quantity, and timing of colostrum feeding and addition of a dried colostrum supplement on immunoglobulin G1 absorption in Holstein bull calves. J Dairy Sci 1997;80:747–753. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Jamaluddin AA. Effects of feeding pasteurized colostrum and pasteurized waste milk on mortality, morbidity, and weight gain of dairy calves [PhD dissertation]. Davis, California: University of California, 1995.

- 5.Jamaluddin AA, Hird DW, Thurmond MC, Carpenter TE. Effect of preweaning feeding of pasteurized and nonpasteurized milk on postweaning weight gain of heifer calves on a Californian dairy. Prev Vet Med 1996;28:91–99.

- 6.Jamaluddin AA, Carpenter TE, Hird DW, Thurmond MC. Economics of feeding pasteurized colostrum and pasteurized waste milk to dairy calves. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1996;209:751–756. [PubMed]

- 7.Murray PR, Baron EJ, Pfaller MA, Tenover FC, Yolken RH. Manual of Clinical Microbiology. 7th ed. Washington, DC: Am Soc Microbiol Pr, 1999.

- 8.Lakritz J, Tyler JW, Hostetler DE, et al. Effects of pasteurization of colostrum on subsequent serum lactoferrin concentration and neutrophil superoxide production in calves. Am J Vet Res 2000;61: 1021–1025. [DOI] [PubMed]