Abstract

Context

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a common hematologic malignancy and is associated with symptom burden and impairments in health-related quality of life (HRQL).

Objectives

To develop a disease-specific, patient-reported outcomes (PRO) measure for the assessment of HRQL among patients with MM as part of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT) measurement system.

Methods

HRQL concerns and symptoms associated with MM were tabulated based on a literature review, and 52 candidate PRO items were identified. Expert clinicians (n=13) rated 52 items on relevance to HRQL for MM patients (0-3 scale). Experts added 11 items for comprehensive PRO assessment in MM. A list of 63 candidate items was rated (0-3 scale) by 13 MM patients enrolled through the International Myeloma Foundation website. Qualitative data and quantitative item ratings were reviewed to select FACT-MM scale items.

Results

Expert clinicians provided the highest HRQL relevance ratings for bone pain, bodily pain, difficulty walking (2.9), tiring easily (2.6), feeling discouraged (2.5), interference with activities and difficulty with self-care as a result of bone pain (2.5), and fatigue (2.5). Mean age of patients was 57 years; Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status was 0 (38%), 1 (31%) or 2 (31%). Quantitative ratings by patients identified sexual function (1.3), uncertainty about health (1.2), fatigue (1.0), weight gain (1.0), and emotional concerns such as worry about new symptoms and difficulty planning for the future (1.0) as most relevant to HRQL.

Conclusion

The 14-item FACT-MM PRO measure was developed based on expert clinician and patient data, ensuring relevance to HRQL for MM patients.

Keywords: Multiple myeloma, health-related quality of life, patient-reported outcomes, patient self-report

Introduction

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a common hematologic malignancy, comprising an estimated 0.8% of all cancers. Clonal proliferation of malignant plasma cells leads to suppression of normal bone marrow function, with secondary progressive bone marrow failure. Furthermore, it typically leads to destruction of bone, renal failure, and impaired immune function leading to fatal infections (1).

Newly diagnosed patients have a five-year survival rate of 32%, with males faring somewhat better than females. To date, there are no known risk factors for MM. There is, however, compelling evidence for ethnic variation in disease incidence, with MM being twice as common among individuals of African origin. There are well-established diagnostic tests and clinical criteria for the disease, which facilitate case recognition and disease monitoring (1).

Existing literature indicates that the most common physical symptoms reported by patients or physicians at presentation are pain, particularly bone pain, and fatigue (1-3). An examination of pain, mood disturbance and health-related quality of life (HRQL) among a convenience sample of 206 multiple myeloma survivors found elevated levels of pain and mood disturbance in comparison to patients with other cancer diagnoses (4). High levels of pain and mood disturbance were predictive of lower HRQL. Impairments in HRQL also have been reported among a sample of 32 multiple myeloma patients who received autologous peripheral blood stem cell transplantation (5).

Significant progress in the treatment of MM has been achieved in the past five years. New biologic therapies, specifically lenalidomide and bortezomib, have been shown to induce prolonged MM remissions in the relapsed and, more recently, in the initial disease presentation. Some of these new treatments also have provided improvement in patient symptoms and functioning, at least for those who respond to treatment (6, 7). Emerging literature suggests this should be the case, because the symptom manifestations and functional impairments caused by disease processes should be by-products of neoplastic pathogenesis. Improvement in HRQL is a relevant treatment goal in MM, as therapy is still rarely curative (6, 8).

In 2005, the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) launched a clinical trial (E1A05) to evaluate a new treatment regimen for MM. HRQL was determined to be a secondary goal for this trial with the purpose to quantify treatment-induced reduction of disease-specific symptoms as well as treatment-related symptoms and toxicities. Based on a comprehensive literature search, the authors concluded that no HRQL instrument existed to adequately capture key MM symptoms and concerns from the patient perspective. This led to collaboration between the ECOG Myeloma, Patient Outcomes and Survivorship, and Patient Representative Committees to develop a patient-reported outcomes (PRO) measure to assess MM symptoms and concerns.

We used the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy (FACIT) measurement system, an established system for the development of PRO measures, as a foundation for the development of an MM-specific PRO scale. FACIT refers to the overall measurement system developed by Cella and colleagues (see www.facit.org) for the assessment of HRQL among adults with various diseases and concerns. The FACIT system includes standard practices for the development of disease- and symptom-specific PROs and standardized instructions for instrument administration and response scales (9-10). The cancer-specific FACIT measure is the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General (FACT-G), developed by Cella and colleagues (9, 10). The FACT-G uses a seven-day recall period, considered to be enough to ensure accurate patient recall while allowing enough time for variability in important symptom experience (11). Responses are based on a five-point Likert scale. Subscales have been developed as part of the FACIT measurement system for administration with the FACT-G to provide targeted assessment of disease-specific concerns (e.g., FACT-Breast, FACT-Lung). Using FACIT measurement system principles for PRO development, FACT subscale item content is developed based on the convergence of findings from qualitative and quantitative research methods employed with patients and expert clinicians (9-11). The purpose of this study was to conduct the initial research necessary to understand the most salient HRQL issues for adults with MM and to develop the relevant content for the FACT-MM, the MM subscale for use with the FACT-G.

Methods

Study Design

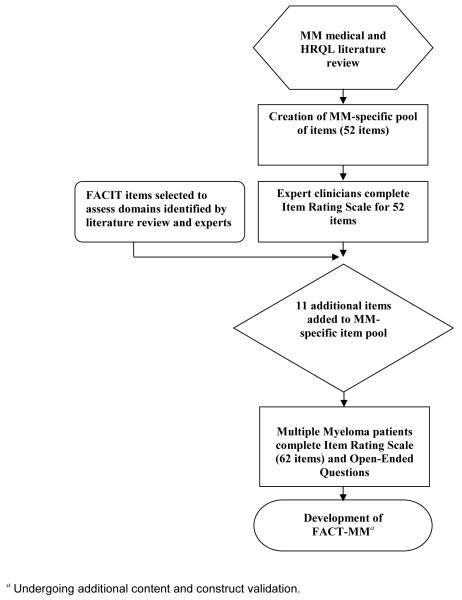

Institutional Review Board approval was obtained to comply with human participant research requirements prior to study initiation. The disease-specific subscale, the FACT-MM, was developed through a triangulation or convergence approach based on the established FACIT method of patient questionnaire construction (9, 10, 12-15). Several sources of information were gathered or generated de novo through a sequential, iterative process involving narrative literature review, primary open-ended text analysis and quantitative survey data. This information was pooled and reconciled in an inclusive process that held patient opinion as primary for the identification of questions that would be listed in the cancer-specific “Additional Concerns” section of the FACT-MM (Appendix A; Fig. 1). The close involvement of myeloma survivors and the International Myeloma Foundation ensured that patient concerns were adequately represented on the FACT-MM instrument. A diagram depicting the FACT-MM development process is presented in Fig. 1.

Figure 1. FACT-MM Content Development Process.

a Undergoing additional content and construct validation.

Literature Review and Pilot Questionnaire Creation

The first step in this process was a comprehensive narrative review of the HRQL literature for multiple myeloma patients. In 2005, the PubMed literature database was used to identify potentially important symptoms, concerns and related HRQL issues across the disease continuum, from newly-diagnosed to advanced stage, using the search terms: “myeloma,” “symptoms,” “quality of life” and “health-related quality of life.” Multiple myeloma clinical studies that captured HRQL information were included whereas studies that were not available in English or had a patient sample size of 20 or less were excluded.

Based on the literature review, a list of common symptoms and HRQL concerns were identified. The FACIT item inventory was reviewed to select 46 existing FACIT items to assess symptoms and HRQL issues identified through the literature review. Six new items were written to assess issues uncovered in the literature review that were not already available in the FACIT inventory. A pool of 52 potential items was created. The inclusion criteria for item entry into the item pool were: 1) item assessed disease symptoms and 2) item assessed physical, mental, emotional or social functioning issues related to disease symptoms. This item pool formed the basis for 52 candidate items for the FACT-MM scale.

Provider Survey

The list of 52 potential FACT-MM items resulting from the literature review was then presented in the form of a paper-based item rating survey to thirteen expert clinicians, specifically, health care providers with expertise in the diagnosis and treatment of multiple myeloma as well as familiarity with HRQL issues in MM. Expert clinicians were recruited by participating researchers from the ECOG Myeloma Committee, the Mayo Clinic in Scottsdale, Arizona, the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, and the Marshfield Clinic of Marshfield, Wisconsin. Expert clinicians evaluated candidate FACT-MM items for comprehensiveness and clinical relevance (Fig. 1). Medical provider characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristic of Participating Multiple Myeloma Hematologists and Oncologists

| Hem/Onc Physicians (n = 13) |

|

|---|---|

| Years of Practice, n (%) | |

| 2-5 years | 1 (7.7) |

| 6-9 years | 2 (15.4) |

| 10+ years | 10 (76.9) |

| Practice setting, n (%) | |

| Academic medical center | 9 (69.2) |

| Community based practice | 4 (30.8) |

| Number of myeloma patients treated | |

| 200 patients | 4 (30.8) |

| 300 patients | 3 (23.1) |

| 500+ patients | 6 (46.2) |

All data self-reported at time of survey completion.

Percentages may not equal 100 due to rounding.

Expert clinicians were asked to rate the initial list of HRQL items on 1) how common the symptom is among patients with multiple myeloma and 2) how important the symptom or concern is to HRQL. Ratings were based on a 0-3 scale, with 0 indicating rare or not at all important and 3 indicating extremely common or extremely important to HRQL. Expert clinicians were asked to review the list of 52 items and identify any gaps in questionnaire content by writing in additional symptoms or concerns. Expert clinicians were asked to circle up to 20 of the most frequent and most important items (including new symptoms/concerns added by the clinician) affecting patients with MM. Free-text comments could be provided for each item, as well as suggestions for new items or issues not already included in the item rating survey. Based on provider ratings and free-text comments, 11 additional items were added to the pool of candidate items for the FACT-MM.

Patient Survey

The resulting list of 63 candidate symptoms or health concerns based on the literature review and expert input were presented to multiple myeloma survivors for review, using a web-based survey. A total of 13 patients recruited by advertisement in a weekly, opt-in email available on the International Myeloma Foundation website (www.myeloma.org) and advertised through a weekly email called the “Myeloma Minute” participated. Patients were entered into the cohort in sequence of electronically-received responses to the survey until reaching the pre-specified sampling frame (n=13). A patient sample of 13 was considered adequate for this content validation research based on qualitative research practices as well as investigator experience (13, 16). Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Participating Multiple Myeloma Patients (n = 13)

| Characteristic | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age, years | |

| Mean (SD) | 57 (9) |

| Median | 58 |

| Gender | |

| Male | 7 (54) |

| Female | 6 (46) |

| Race | |

| White | 12 (92) |

| Asian | 1 (8) |

| Overall Health | |

| Excellent | 3 (23) |

| Very good | 3 (23) |

| Good | 4 (31) |

| Fair | 3 (23) |

| Poor | 0 (0) |

| ECOG PS | |

| Normal activity, no symptoms (0) | 5 (38) |

| Some symptoms, no daytime rest (1) | 4 (31) |

| Rest required, less than half the day (2) | 4 (31) |

| Rest required, more than half the day (3) | 0 (0) |

| Unable to get out of bed (4) | 0 (0) |

| MM Treatment Status | |

| Treated for first time | 3 (23) |

| Previously treated, in remission, with no treatment | 5 (38) |

| Previously treated, in remission, with maintenance treatment |

1 (8) |

| Previously treated, relapsed, and receiving treat treatment |

4 (31) |

| Disease duration, mean (SD) years | 5 (5) |

| Median years | 3 |

ECOG PS = ECOG Performance Status (self-reported); SD = standard deviation. All data patient-reported at time of survey. Percentages may not equal 100 due to rounding.

The survey used a semi-structured interview format to elicit personal experiences about how multiple myeloma and its treatment may affect physical and emotional health, functioning in life, family/social issues, sexuality/intimacy, work status, and future aspirations. Patients were first provided with an open-ended, free-text space to comment broadly on what “quality of life” meant to them as they coped with multiple myeloma.

After securing their open ended responses on how MM impacted their lives, patients were asked to complete item ratings for the list of 52 FACT-MM candidate items with the addition of 11 disease issues identified by providers. Patients were asked to rate each item from 0-3 based on how important the symptom or concern is to HRQL, anchored between “Not at all important” (0) and “Extremely important” (3). As described above, patients completed study questionnaires via the internet and study questionnaires were administered using a web-based program. As with providers, patients had the opportunity to provide free-text comments on any of the questions as well as suggest additional symptoms or issues that were not covered in the list of candidate items. Standard demographic and clinical questions were included in the patient survey to characterize the study population. Patients also reported on their current and previous multiple myeloma therapies as well as present supportive care treatment. Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the MM patient sample.

Item Review and Scale Generation

Information from the provider and patient surveys was summarized and the frequency of items receiving a “top 20” score was tabulated. Qualitative data, including free-text comments regarding candidate items, symptoms and concerns that were added to the list of candidate items, and patient responses to open-ended questions regarding HRQL were tabulated and summarized. Descriptive statistics were performed on the item rating surveys for both the experts and patients. A mean importance comparison tabulation was created for all items to evaluate concordance between provider and patient item ratings.

Final Item Review

A final list of items was then reviewed by the FACIT Multilingual Translation Team to screen for potential translation issues, and suggest item wording in problematic instances. Wording was changed on three items in order to have a more inclusive measurement of functioning and for consistency with FACIT items. Items were then formatted according to the five-point Likert scale used for FACIT measures (Appendix A).

Results

Provider Survey

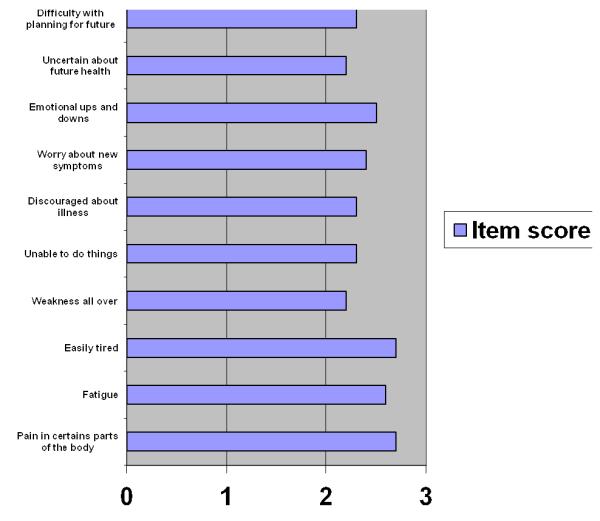

A total of 13 physicians with expertise in the clinical management of myeloma participated. As shown in Table 1, the majority of expert clinicians had been in practice for more than 10 years, treated 500 or more patients with myeloma, and practiced in academic medical centers. Figure 2 presents provider ratings of the most common disease-related symptoms. As shown in Fig. 2, pain, fatigue and associated symptoms (becoming easily tired, weakness) and distress and worry secondary to health were the most common disease-related symptoms. Pain, particularly bone pain, and fatigue dominated the item importance rankings for providers.

Figure 2. Top 10 most frequent multiple myeloma health issues according to expert clinicians (n = 13).

Mean item ratings of the most common health issues. Item scores based on categorical responses: Rare (0), Occasional (1), Common (2) or Extremely Common (3).

Table 3 lists the 10 candidate items with the highest item rating with regard to importance to HRQL. As shown in Table 3, having bone pain, experiencing pain in “certain parts of my body” and difficulty walking because of bone pain had the highest mean scores for importance to HRQL (x = 2.9, standard deviation [SD] = 0.3) on a scale from 0 (not at all important) to 3 (very important). The next highest item on importance to HRQL assessed fatigue. The item “tiring easily” had a mean rating of 2.6 (SD = 0.1) and the item “I feel fatigued” had a mean rating of 2.5 (SD = 0.5). The impact of bone pain on daily living was clearly recognized by providers, who rated the need for assistance with usual activities because of bone pain (x = 2.5, SD = 0.5) and interference in ability to care for oneself because of bone pain (x = 2.5, SD = 0.5) as in the top symptoms and concerns affecting HRQL. Expert clinicians also acknowledged the emotional aspects of MM as important to HRQL. The mean item rating for the item to assess “feeling discouraged” was also 2.5 (SD = 0.7).

Table 3.

Top 10 Health Issues in Multiple Myeloma by Mean Rating of Importance to HRQL by Providers and Patients with Content Development Decision

| Provider Top 10 Items | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Item | Mean (n = 13) | SD | Item Retained in FACT-MM |

| I have bone pain | 2.9 | 0.3 | X |

| I have certain parts of my body where I experience pain |

2.9 | 0.4 | X |

| I have trouble walking because of bone pain | 2.9 | 0.4 | X |

| I get tired easily | 2.6 | 0.1 | X |

| I feel discouraged about my illness | 2.5 | 0.7 | X |

| I need help doing my usual activities because of bone pain |

2.5 | 0.5 | X a |

| Bone pain interferes with my ability to care for myself |

2.5 | 0.5 | |

| I have bone pain even when I sit still | 2.5 | 0.8 | |

| I am forced to rest during the day because of bone pain |

2.5 | 0.7 | |

| I feel fatigued | 2.5 | 0.5 | X |

| Patient Top 10 Items b | |||

| Item | Mean (n= 13) | SD | Item Retained in FACT-MM |

| I am satisfied with my sex life | 1.3 | 1.0 | c |

| I feel uncertain about my future health | 1.2 | 0.8 | c |

| I have gained weight | 1.0 | 1.2 | X |

| I get tired easily | 1.0 | 1.0 | X |

| I worry that I might get new symptoms of my illness |

1.0 | 1.0 | X |

| Because of my illness, I have difficulty planning for the future |

1.0 | 0.9 | X |

| I have emotional ups and downs | 0.9 | 0.9 | X |

| I have trouble concentrating | 0.9 | 1.1 | X |

| I worry about getting infections | 0.9 | 1.0 | X |

| I feel weak all over | 0.8 | 1.0 | X |

Provider and patient scores are based on a 0-3 scale, where 0 indicated “not at all important” and 3 indicated “extremely important”; n=13 for all.

A modified version of this item was retained based on an existing FACIT item.

Reporting only disease-based health issues and not those related to satisfaction with treatment or provider communications.

These items are already captured in the FACT-G which is typically administered along with the MM subscale

Patient Survey

Patient characteristics are presented in Table 2. Of the 13 patients respondents, seven were male (54%) and 12 were Caucasian (92%), with an average age of 57 years and a median disease duration of three years. Four (31%) had been previously treated for multiple myeloma but had relapsed and were undergoing treatment at the time of the survey. Most patients (n=8; 62%) were either receiving front-line treatment or were in remission from previous therapy. Almost half (n = 6; 46%) considered their overall health as either excellent or very good. Patient-rated ECOG performance status (PS) was roughly divided between an asymptomatic life of normal activity (PS = 0; 38%), having symptoms, but not requiring daytime rest (PS = 1; 31%), or rest required less than half of the day (PS = 2; 31%).

Patients reported previous treatment with bisphosphonates, dexamethasone, interferon-alpha, lenalidomide, melphalan, stem-cell transplantation, thalidomide, and vincristine/adriamycin/dexamethasone. Current therapeutic regimens included bisphosphonates, cyclophosphamide, dexamethasone, lenalidomide, and prednisone, sometimes in various combinations. At the time of the survey, six (43%) reported current steroid use, five (36%) reported pain medication use, and two (14%) reported fatigue treatment. The described prescription pain medications included acetaminophen with codeine, oxycodone, morphine and gabapentin. Erythropoietin alpha for management of anemia and secondary fatigue, methylphenidate for management of fatigue, and benzodiazepines for management of anxiety and insomnia also were reported.

Based on a summary of qualitative data, patients identified a set of themes or issues when asked semi-structured questions about their perceptions of HRQL while living with MM. Patient responses are summarized in Table 4. The majority of respondents defined HRQL as the ability to perform daily activities (69%) and engage in pleasurable, recreational activities (54%). Five participants described the absence of symptom burden as important to HRQL and the two most important physical symptoms were pain and fatigue (tiredness, lack of energy). In response to the question “What do you think is important when you think of quality of life?,” a total of six participants described emotional distress, including depression, anxiety, despair, and worry. With regard to the most important aspects of MM that affect HRQL, one participant commented, “Managing the depression and despair, especially because the disease requires daily management. I get reminded all the time.” In response to a semi-structured question regarding mental and cognitive issues associated with MM, seven participants reported either that providers should educate patients about cognitive dysfunction associated with treatment, providers should assess for cognitive decline, or participants should directly reported experiencing cognitive deficits. Given the opportunity to provide general input on HRQL concerns, participants spontaneously reported the importance of addressing family and caregiver issues. When asked to describe which aspect of the disease experience was the most bothersome with regard to symptoms, feelings or other concerns, patients ranked symptom intensity most significant (11; 85%), followed by symptom duration (8; 62%) and frequency of symptoms (7; 54%).

Table 4.

Top Five Patient-Defined HRQL Issues, Overall and Important (n = 13)

| Definition of HRQL a | Important to HRQL b | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency n (%) |

Health Issue | Frequency n (%) |

Health Issue |

| 9 (69) | Performing ordinary, day-to-day activities |

6 (46) | Emotional distress d |

| 7 (54) | Enjoying life and able to do enjoyable activities |

5 (38) | Daily, normal physical activities |

| 3 (23) | Absence of pain | 4 (31) | Pain |

| 3 (23) | Feeling emotionally well | 3 (23) | Recreational activities |

| 2 (15) | Having energy c | 2 (15) | Fatigue e |

Responding to the question, “What does quality of life mean to you?”

Responding to the question, “What do you think is important when you think of quality of life?”

Described as being able to participate in social activities, also reported by two patients.

Described as anxiety, worry, depressed mood, and despair.

Interference of fatigue in enjoying relationships with family and friends (2) and eating normal food (2) described.

Patient mean ratings of the importance of candidate items to HRQL are listed in Table 3 for the 10 items with the highest mean ratings. As shown in Table 3, sexual function (x = 1.3, SD = 1.1), weight gain (x = 1.0, SD = 1.2), and fatigue (x = 1.0, SD = 1.0) are among the 10 items with the highest mean rating. Items assessing uncertainty about future health (x = 1.2, SD = 0.8), worry about new symptoms (x = 1.1, SD = 1.0), difficulty planning for the future (x = 1.0, SD = 0.9) and emotional ups and downs (x = 0.9, SD = 0.9) were among the top items based on ratings of importance to HRQL.

Patient and Provider Agreement

Table 3 lists the items identified as most important to HRQL based on mean ratings of importance, from 0 (“not at all important”) to 3 (“extremely important”) for expert clinicians and patients. As shown in Table 3, one item appeared in both the patient and provider list of the 10 most important concerns (“I get tired easily”).

Final Item Selection

Table 3 indicates items from expert clinician and patient mean rankings of importance to HRQL that were retained for the FACT-MM scale. Of expert clinician ratings, six were included in the FACT-MM scale and one item was modified and retained. Based on expert clinician ratings, a total of seven items related to bone pain and interference in function because of bone pain were ranked highly with regard to importance to HRQL. Among these seven items, the three items that assess bone pain that received the highest “importance to HRQL” rating were retained. An additional three items that assess bone pain were not retained because of an excess of questions in this domain. One item identified by providers as an important concern (needing help with usual activities due to bone pain) is included in the FACT-MM subscale without the phrase “due to bone pain” because this item exists in the FACIT measurement system as part of the FACT-Anemia scale. This item assesses the need for assistance with usual activities without regard to the specific symptom or symptoms causing impairment. The selection of existing FACIT items when possible to assess domains identified as important to HRQL will allow for comparison across samples and across studies.

Of the 10 most important symptoms and concerns identified by patients based on mean item ratings, one item was also among the 10 most important symptoms identified by expert clinicians and was selected for inclusion in the FACT-MM scale. Based on patient ratings of importance to HRQL, an additional seven items were selected for inclusion in the FACT-MM scale. Two items identified by patients as important to HRQL were not retained because of redundancy. One item is already included in the FACT-General scale (“I am satisfied with my sex life”). The second item not included in the FACT-MM scale (feel uncertain about future health) was redundant with similar items assessing health-related concerns (e.g., difficulty planning for the future, worry about new symptoms) that were retained for the scale. A final list of 14 items was created.

To ensure that the most relevant symptoms and concerns to HRQL were adequately assessed by items selected for the FACT-MM scale, a separate list of candidate scale items was created using expert clinicians’ nominations of items as being among the “top 20” most important symptoms and concerns as part of the item rating survey. This list was compared to the list of 14 items selected for the FACT-MM scale draft. A total of 10 items had a 50% or greater endorsement rate. Of these items, five were included in the 14-item myeloma scale. These items assess bone pain, pain, fatigue, feeling discouraged, and emotional ups and downs. Five items were not selected for the FACT-MM scale because of FACT-G overlap (sexual function, sleep, able to do the things I want to do) or as a result of being primarily treatment-related (neuropathy, constipation).

Review of FACIT Measurement System

The list of 14 candidate items selected for the FACT-MM was reviewed for content overlap with items that already exist in the FACIT measurement system. A total of 13 items from nine disease- and treatment-related scales were identified and determined to adequately assess symptoms and concerns identified as important to HRQL by expert clinicians and patients. These 13 items were selected from the FACIT measurement system for inclusion in the FACT-MM scale. Items that were retained for the FACT-MM scale include three items from the FACT-Leukemia scale (feeling discouraged, difficulty planning, and worry about the future), four items from the FACT-Anemia scale (weakness, fatigue, help with activities, trouble concentrating), and items from the following FACT scales: Prostate (bodily pain), Bone Marrow Transplant (tire easily), Neutropenia (worry about infection), Biologic Response Modifier (emotional ups and downs), Bone Pain (bone pain), and Endocrine symptoms (weight gain). A new item was created for the FACT-MM, “I have trouble walking because of pain.”

Discussion

The FACT-MM was developed through a structured, iterative process that drew upon several information sources to identify the relevant content for a disease-specific HRQL questionnaire in multiple myeloma. The multi-modal method incorporated open-ended questions with classic survey methods, eliciting both known and new HRQL issues from MM patients and the health care providers who treat them.

Both physicians and patients rated physiologic disease manifestations as frequent and important but patients also considered their mental health and sexual function as vital to their lives. This was particularly so with respect to their emotional well-being, depression, anxiety, despair, worry and uncertainty about the future. The lack of consistency between provider and patient ratings of symptoms and concerns most relevant to HRQL suggests that patients may not discuss more personal aspects of their illness experience (e.g., anxiety, uncertainty, sexual function) with oncology providers. One of the most important aspects in the current treatment milieu of MM is the chronicity of treatment and availability of multiple treatment options. This, paired with heightened anxiety regarding blood tests, amplifies the emotional effects of disease. However, provider and patient ratings were generally similar with regard to bothersome physical symptoms. Consistent with the literature review, the most important physical health issues reported by patients were pain, fatigue and interference with daily as well as recreational activities (4, 5).

There are several limitations to this study. The number of MM patients providing insight into their disease-specific health issues is small and constitute a U.S. convenience sample. Patients who participated in the study were younger and higher-functioning than the general U.S. multiple myeloma population. Thirty-eight percent of the sample was currently in remission and not receiving treatment and may have underreported disease-related symptoms. In addition, the sample predominantly included Whites. Consequently, the applicability of these findings to minority U.S. populations, those of other countries, and patients with greater morbidity is unknown. Additional content development work among larger, more heterogeneous patient samples from clinical settings is needed, especially to avoid the potential bias associated with internet surveys (14, 17, 18). Follow-up research should evaluate whether the same symptoms and concerns included in the FACT-MM scale are the most important concerns with regard to HRQL among diverse samples of adults living with multiple myeloma.

Clinical data, such as treatment stage, time since diagnosis, and supportive care utilization is patient-reported and may not be complete or correspond to medical records. Patient scoring of the pain items must be placed in context of analgesic usage, although some patients indicating current opioid medication still rated pain as an important disease issue. These patients commented on the importance of strong opioids in handling their pain in the free-text field.

Despite these limitations, it is likely the most relevant HRQL issues associated with multiple myeloma were identified through this research process because we utilized a synthesis of information from multiple sources including qualitative and quantitative data. In doing so, we have followed a “best practices” model in the initial steps for developing a patient-reported outcomes measure (13-16). The diagnosis-specific HRQL subscale developed through this process assesses pain, fatigue, physical activity, emotional health and cognitive capacity. When the multiple myeloma subscale is added to the FACT-G to create the FACT-MM, it provides a comprehensive assessment of health from the patient perspective. When combined with clinical assessments, the FACT-MM can provide a broader, more complete picture of patient health status and will capture data on domains most relevant to patient’s well-being (6, 8).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We greatly appreciated the participation of the multiple myeloma patients and providers in this project. The authors also wish to thank Kimberly Webster and Katie Langfeld for valuable contributions to data review and interpretation.

Support for this research was provided in part by funding from the National Cancer Institute (U10 CA037403) awarded to the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group.

Footnotes

Disclosures The authors have no conflicts of interest or financial relationships to disclose.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Alexander DD, Mink PJ, Adami H-O, et al. Multiple myeloma: a review of the epidemiologic literature. Int J Cancer. 2007;120(Suppl 12):40–61. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sherman AC, Simonton S, Latif U, Spohn R, Tricot G. Psychosocial adjustment and quality of life among multiple myeloma patients undergoing evaluation for autologous stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transpl. 2004;33:955–962. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1704465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kyle RA, Rajkumar SV. Multiple myeloma. Blood. 2008;111:2962–2972. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-10-078022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Poulos AR, Gertz MA, Pankratz VS, Post-White J. Pain, mood disturbance, and quality of life in patients with multiple myeloma. Oncol Nur Forum. 2001;28:1163–1171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Slovacek L, Slovackova B, Pavlik V, et al. Health-related quality of life in multiple myeloma survivors treated with high dose chemotherapy followed by autologous peripheral blood progenitor cell transplantation: a retrospective analysis. Neoplasma. 2008;55:350–355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anderson KC, Kyle RA, Rajkumar SV, et al. on behalf of the ASH/FDA Panel on Clinical Endpoints in Multiple Myeloma Clinically relevant end points and new drug approvals for myeloma. Leukemia. 2008;22:231–239. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2405016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.San-Miguel J, Harousseau JL, Joshua D, et al. Individualizing treatment of patients with myeloma in the era of novel agents. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:2761–2766. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.2546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Victorson D, Soni M, Cella D. Meta-analysis of the correlation between radiographic tumor response and patient-reported outcomes. Cancer. 2006;106:494–504. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cella DF, Tulsky DS, Gray G, et al. The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy scale: development and validation of the general measure. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11:570–579. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.3.570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Webster K, Cella D, Yost K. The Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy (FACIT) Measurement System: properties, applications, and interpretation. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003;1:79. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-1-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chang CH, Cella D, Clarke S, et al. Should symptoms be scaled for intensity, frequency, or both? Palliat Support Care. 2003;1:51–60. doi: 10.1017/s1478951503030049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Russell CK, Gregory DM. Evaluation of qualitative research studies. Evid Based Nurs. 2003;6:36–40. doi: 10.1136/ebn.6.2.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cresswell JW. Research design: Qualitative, quantitative and mixed method approaches. 3rd ed Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Groves RM, Fowler FJ, Jr., Couper MP, et al. Survey methodology. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; Hoboken, NJ: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schaeffer NC, Presser S. The science of asking questions. Ann Rev Sociology. 2003;29:65–88. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mays N, Pope C. Assessing quality in qualitative research. BMJ. 2000;320:50–52. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7226.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Couper MP. Web surveys: a review of issues and approaches. Public OpinQ. 2000;64:464–494. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dillman DA. Mail and internet surveys: The tailored design method. Wiley; New York: 2000. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.