ABSTRACT

Noncoding RNAs, including antisense RNAs (asRNAs) that originate from the complementary strand of protein-coding genes, are involved in the regulation of gene expression in all domains of life. Recent application of deep-sequencing technologies has revealed that the transcription of asRNAs occurs genome-wide in bacteria. Although the role of the vast majority of asRNAs remains unknown, it is often assumed that their presence implies important regulatory functions, similar to those of other noncoding RNAs. Alternatively, many antisense transcripts may be produced by chance transcription events from promoter-like sequences that result from the degenerate nature of bacterial transcription factor binding sites. To investigate the biological relevance of antisense transcripts, we compared genome-wide patterns of asRNA expression in closely related enteric bacteria, Escherichia coli and Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium, by performing strand-specific transcriptome sequencing. Although antisense transcripts are abundant in both species, less than 3% of asRNAs are expressed at high levels in both species, and only about 14% appear to be conserved among species. And unlike the promoters of protein-coding genes, asRNA promoters show no evidence of sequence conservation between, or even within, species. Our findings suggest that many or even most bacterial asRNAs are nonadaptive by-products of the cell’s transcription machinery.

IMPORTANCE

Application of high-throughput methods has revealed the expression throughout bacterial genomes of transcripts encoded on the strand complementary to protein-coding genes. Because transcription is costly, it is usually assumed that these transcripts, termed antisense RNAs (asRNAs), serve some function; however, the role of most asRNAs is unclear, raising questions about their relevance in cellular processes. Because natural selection conserves functional elements, comparisons between related species provide a method for assessing functionality genome-wide. Applying such an approach, we assayed all transcripts in two closely related bacteria, Escherichia coli and Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium, and demonstrate that, although the levels of genome-wide antisense transcription are similarly high in both bacteria, only a small fraction of asRNAs are shared across species. Moreover, the promoters associated with asRNAs show no evidence of sequence conservation between, or even within, species. These findings indicate that despite the genome-wide transcription of asRNAs, many of these transcripts are likely nonfunctional.

Introduction

Antisense RNAs (asRNAs) are transcripts encoded on the strand complementary to protein-coding genes. Many of the first bacterial asRNAs were shown to influence horizontally acquired elements by regulating bacteriophage gene expression, controlling plasmid and transposon copy number, and serving as antitoxins that promote plasmid retention (1–5). The recent application of deep-sequencing technologies has revealed that chromosomal antisense transcription is widespread in bacterial genomes (6–8). For example, in diverse bacterial lineages, such as Escherichia coli, Synechocystis, and Helicobacter pylori, between 20% and 50% of protein-coding genes have been found to encode asRNAs (9–11).

Despite the pervasive transcription of antisense sequences, the role of most antisense transcripts is unknown. Of the thousands of proposed asRNAs in E. coli, the functions of only a few have been characterized (12–14). Similarly, in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium, the function of only a single asRNA has been described (15). Despite the paucity of functionally characterized asRNAs, it is often assumed that because it is costly to produce RNA, most asRNAs are likely to perform some function. Alternatively, a major fraction of asRNAs could represent nonadaptive transcriptional noise due to the low information content present in bacterial promoters (16).

The degree of conservation among homologous sequences provides an effective method for discriminating functional from nonfunctional sequences; but to date, no studies have investigated the genome-wide patterns of asRNA conservation in bacterial species or applied a comparative approach to evaluate the functional relevance of asRNAs. To this end, we sequenced in parallel the transcriptomes of E. coli and Salmonella Typhimurium and identified highly expressed transcripts arising from the opposite strand of protein-coding genes in each genome. Although antisense transcription is abundant in both species, only a small fraction of asRNAs are conserved across species, and the promoter elements associated with these transcripts show no evidence of purifying selection. The lack of evolutionary conservation between these two closely related enteric bacteria, combined with comparisons of strains within species, supports the view that many or even most of the asRNAs detected by deep-sequencing techniques are nonfunctional transcripts originating from spurious promoter-like sequences that arise nonadaptively throughout the genome.

RESULTS

Pervasive antisense transcription in E. coli and Salmonella.

We obtained approximately 30 million 35-nucleotide (nt) strand-specific sequencing reads each from exponential-phase E. coli and Salmonella Typhimurium grown in LB medium, with approximately 90% of the reads mapping to the respective genomes (Table 1). The read coverages for the two genomes are nearly identical, with ≈2% of the reads mapping to the antisense strands of protein-coding genes. After applying empirically derived cutoffs to recognize expressed sequences from both genomes (see Materials and Methods), we detected sense and antisense transcripts from ≈75% and ≈28% of protein-coding genes, including transcripts from 14 of 17 previously annotated asRNAs in E. coli (see Table S1 in the supplemental material).

TABLE 1 .

Sequencing reads mapped to E. coli and Salmonella genomes

| Characteristic | Value for genome |

|

|---|---|---|

| E. coli | Salmonellaa | |

| Total no. of reads | 30,206,434 | 29,275,111 |

| Total mapped reads (%) | 88 | 87 |

| Protein-coding genes (%) | ||

| Sense | 30 | 27 |

| Antisense | 2 | 2 |

| Intergenic regions (%) | 54 | 55 |

| Plasmid (%) | No plasmid | 0.4 |

Of 5,313 putative ORFs in the Salmonella Typhimurium 14028S genome, only 4,477 with orthologs in Salmonella Typhimurium LT2 and/or in E. coli MG1655 were considered.

Detection of transcription start sites and quantification of expression levels.

The strand-specific coverage at each genomic position was visualized and manually inspected using the Artemis software tool (17). As observed in previous deep-sequencing studies (18–21), sequencing reads accumulated with a pronounced peak at the 5′ end of each gene (Fig. 1). Although this bias precludes characterizing the read coverage across the whole transcript, it allows the relatively precise identification of transcription start sites (TSSs) based on the 5′ end of mapped reads (Fig. 1). For a sample of 50 highly expressed protein-coding genes, 80% of the TSSs identified with RNA-seq data were within 2 bp of experimentally determined positions (22) (see Table S2 in the supplemental material).

FIG 1 .

Location of an asRNA within the holE coding region of E. coli. Transcripts identified by RNA-seq mapped onto the E. coli genome: reads corresponding to holE mRNA transcripts are in red, and reads corresponding to the antisense transcript are in green. Locations of TSSs and the direction of transcription are shown. Numbering is according to the E. coli MG1655 genome (NC_000913.2).

To verify the relationship between mapping coverage and gene expression, we used a quantitative PCR (qPCR) assay with a set of 4 mRNAs and 18 asRNAs whose maximum read depths spanned several orders of magnitude. We found that maximum read depth was an accurate measure of expression level as estimated by qPCR for both mRNAs (r = 0.920; P < 0.05) and asRNAs (r = 0.814; P ≪ 0.001; see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material).

Highly expressed asRNAs from E. coli and Salmonella.

To compare the most highly expressed asRNAs in E. coli and Salmonella, we identified antisense TSSs within annotated protein-coding genes with a maximum read depth of at least 200. We excluded antisense TSSs within prophage genes and those that were located at the extreme 5′ end of a protein-coding gene and likely represented the TSSs for a divergently transcribed gene on the opposite strand. Based on these criteria, we identified 90 asRNAs in E. coli and 91 in Salmonella. These corresponded to a total of 173 distinct genes, 120 of which have orthologs in both species (see Tables S3 and S4 in the supplemental material).

asRNAs are enriched for σ70 promoters.

Consistent with previous findings (9), the antisense TSSs that we identified by deep sequencing were frequently associated with canonical promoter elements on the antisense strand, further validating the use of RNA-seq to identify TSSs and indicating that most of the identified asRNAs are expressed under the control of the σ70 transcription factor. In both E. coli and Salmonella, >70% of the antisense TSSs had an identifiable −10 promoter element (Fig. 2) (23). This represents a highly significant enrichment (P < 0.001), since only ≈15% of randomly chosen antisense positions have a −10 sequence that met these criteria (Fig. 2). In contrast, similar analyses for σ28, σ32, or σ54 promoters did not yield significant enrichments upstream of antisense TSSs in either species.

FIG 2 .

Enrichment of promoter elements associated with antisense RNAs. Distributions show null expectations for the percentage of randomly selected antisense sites associated with a −10 promoter element in the E. coli (black/right) and Salmonella (gray/left) genomes. For each genome, arrows indicate the percentage of identified antisense TSSs associated with −10 promoter elements.

Most asRNAs are not shared between species.

Among the 120 orthologous gene pairs with a highly expressed asRNA in either E. coli or Salmonella, only 8 (6.7%) showed high antisense expression in both species, and only 3 (2.5%) shared an identical antisense TSS position. Applying relaxed criteria that included any asRNA with a maximum read depth of at least 20 and an antisense TSS within 10 bp, we found that only 17 (14.2%) of the 120 gene pairs shared antisense expression at homologous positions in E. coli and Salmonella (Table 2).

TABLE 2 .

Genes with asRNAs conserved on their noncoding strands in E. coli and Salmonella

| Gene | Product | asRNA expressiona |

Distance between TSS positions (bp) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli | Salmonella | |||

| acrR | DNA-binding transcriptional repressor | 495 | 819 | 0 |

| asd | Aspartate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase, NAD(P) binding | 1,062 | 57 | 0 |

| erfK | l,d-Transpeptidase linking Lpp to murein | 176 | 680 | 1 |

| gloB | Hydroxyacylglutathione hydrolase | 110 | 1,079 | 1 |

| ispB | Octaprenyl diphosphate synthase | 30 | 637 | 1 |

| mdtL (yidY) | Multidrug efflux system protein | 447 | 143 | 0 |

| metB | Cystathionine gamma-synthase, PLP dependent | 502 | 40 | 0 |

| mltC | Membrane-bound lytic murein transglycosylase C | 178 | 657 | 0 |

| napA | Nitrate reductase, periplasmic, large subunit | 419 | 209 | 10 |

| nudF | ADP-ribose pyrophosphatase | 171 | 346 | 0 |

| pflB | Pyruvate formate lyase I | 79 | 214 | 0 |

| treR | DNA-binding transcriptional repressor | 321 | 28 | 0 |

| ybhA | Pyridoxal phosphate (PLP) phosphatase | 270 | 29 | 0 |

| ycdX | Predicted zinc-binding hydrolase | 204 | 3,500 | 10 |

| yhbE | Predicted inner membrane permease | 90 | 243 | 1 |

| yjjX | Inosine/xanthosine triphosphatase | 1,113 | 419 | 0 |

| ytfP | Conserved protein, UPF0131 family | 432 | 550 | 0 |

Maximum depth of mapped reads near asRNA TSS.

For asRNAs that were expressed in one species but not detected in the orthologous gene in the other species, the species lacking the asRNA was less likely to have an antisense −10 promoter element. In such cases, only 26.9% of the homologous positions in E. coli and 31.5% in Salmonella had an identifiable −10 promoter element. Although these values are greatly reduced relative to the frequencies of >70% observed for expressed asRNAs, they still significantly exceed the expectation based on randomly chosen antisense positions (P < 0.05) (Fig. 2). As expected, promoter elements were much less likely to be shared between E. coli and Salmonella if antisense expression was detected in only one of the species (37%) than if it was detected in both (90%) (P = 0.002, Fisher’s exact test).

Lack of purifying selection on antisense promoters.

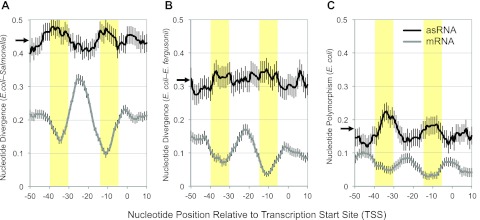

Patterns of DNA sequence divergence provide an effective tool for identifying sequences of functional importance. Such sequences typically experience purifying selection, meaning that most new mutations are deleterious and are therefore eliminated from the population. As a result, functional sequences show lower rates of sequence evolution than their nonfunctional counterparts. Promoters are necessary for the precise control of gene expression, and their sequences are typically under purifying selection and enriched in the regulatory regions of bacterial genomes (23–25). Accordingly, we found that the promoter regions for mRNAs exhibited reduced nucleotide divergence between E. coli and Salmonella relative to third codon position sites within protein-coding sequences. In particular, mRNA promoters exhibited pronounced reductions in divergence around the −35 and −10 elements, important functional regions that are involved in σ factor binding (Fig. 3A).

FIG 3 .

Comparisons of divergence/polymorphism in asRNA and mRNA promoter sequences. Plotted are averages from a 9-bp sliding window of the interspecific sequence divergence between either E. coli and Salmonella (A) or E. coli and E. fergusonii (B) or for the proportion of segregating sites within E. coli (C). Black arrows on y axes indicate average divergence (or polymorphism) for the entire coding sequences of ORFs containing asRNAs. Note that levels of sequence divergence (or polymorphism) in the asRNA promoter regions are statistically indistinguishable from the corresponding levels in the surrounding ORF (P > 0.5 for all three data sets; paired t tests). The 10 bp flanking the −10 and −35 regions have been highlighted. Each error bar represents ±1 standard error of the proportion.

In contrast to the functional constraint acting on promoter regions of mRNAs, there was no evidence of purifying selection on antisense promoter regions in E. coli and Salmonella. This is consistent with the observed differences between these species in antisense expression patterns and in the presence/absence of antisense promoter elements. The levels of sequence divergence in antisense promoter regions were indistinguishable from background levels in the surrounding gene, and unlike the situation for mRNA promoters, there was no indication of specific reductions in the rate of sequence evolution around the −10 and −35 positions (Fig. 3A).

Repeating this analysis with E. coli and its congener Escherichia fergusonii yielded similar results, indicating that even on a more recent evolutionary time scale, there is no evidence of selection on antisense promoter regions (Fig. 3B). Furthermore, we found a similar pattern at the intraspecific level by analyzing 41 completely sequenced E. coli genomes, revealing a reduced frequency of polymorphic sites in promoter regions (particularly around the −35 and −10 positions) for mRNAs but not for asRNAs (Fig. 3C).

DISCUSSION

We detected widespread antisense transcription and strikingly similar numbers of asRNAs in E. coli and Salmonella but found that most individual asRNAs are not shared between these two closely related enteric bacteria. The lack of conservation in asRNAs between these species might be taken to indicate that asRNAs function largely in a species-specific manner; however, we found no evidence of conservation or functional constraint acting within the genus Escherichia or even among different strains of E. coli (Fig. 3). Therefore, we suggest the alternative interpretation that a large fraction of antisense expression in bacterial genomes is nonfunctional.

Promoter-like sequences are expected to arise spontaneously by point mutations over short evolutionary time scales in bacterial genomes because of the low information content in σ70 transcription factor binding sites (16, 26). The underrepresentation of transcription factor binding motifs in bacterial genomes indicates that selection acts to purge spurious promoters (23, 24, 27). However, Hahn et al. (27) found that the average intensity of selection against such elements is weak, falling well within the range of “nearly neutral” mutations, where the effects of genetic drift begin to overwhelm the strength of selection (28, 29). Consequently, many spurious promoter-like sequences are expected to persist within populations and even reach fixation based purely on nonadaptive mechanisms of mutation and drift.

In the context of these observations, the lack of conservation in highly expressed bacterial asRNAs between E. coli and Salmonella and within E. coli suggests that many of these transcripts are the products of transcriptional misfiring resulting from the degenerate nature of the binding site motifs for the housekeeping σ factor. This conclusion parallels a recent examination of the Bacillus subtilis transcriptome, which also found many asRNAs to be products of spurious transcriptional events from evolutionarily less conserved promoter sequences (30).

The recent analysis of transcription in B. subtilis (30) found that asRNAs were highly variable across environmental conditions and originated preferentially with alternative promoters. In contrast to the situation in B. subtilis, we found asRNA expression in E. coli and Salmonella to be predominantly controlled by the housekeeping σ70 factor, consistent with expectations given our sampling at log-phase growing conditions. It is possible that our analysis captured only a fraction of potential antisense expression, which could account for the limited overlap observed between the sets of asRNAs reported in different studies of E. coli (see Table S5 in the supplemental material). The sensitivity of spurious transcription events to minor environmental differences may also explain why antisense TSS positions are weakly but significantly enriched in promoter-like sequences, even in species for which we found no expression of the corresponding asRNA.

Even if most asRNAs do not have a clear role in cellular processes, there are undoubtedly some individual asRNAs that serve some biological function. Previous studies have described functional asRNAs in both E. coli and Salmonella (12–15), and a recent analysis of the transcriptomes of a number of Gram-positive bacteria suggests a role for asRNAs in genome-wide mRNA processing (31). Our findings, however, make it clear that the identification of antisense expression does not, in and of itself, confirm an adaptive role. The future identification of functional asRNAs should ideally link expression data to a combination of genetic, biochemical, and evolutionary data to reject the null hypothesis that expression is a consequence of transcription from spurious promoters.

The existence of pervasive, antisense transcription may be of general consequence to the cell: antisense transcription itself may be metabolically costly or interfere with the expression of the cognate protein-coding gene (32), and asRNA transcripts could potentially serve as raw material for the evolution of new regulatory elements. Noncoding RNAs and regulatory sequences have been found to be involved in short-term evolutionary diversification and adaptation to local environments in both bacteria and eukaryotes (33–36), suggesting that strain-specific evolution of noncoding transcripts has the potential to supply new functions. Pervasive antisense expression may also affect genome contents in that bacterial mutations are biased towards A+T (37, 38) and selection pressure acting to purge AT-rich promoter-like sequences would have a counterbalancing effect on the genomic base composition.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, RNA preparation, library construction, and sequencing.

E. coli K-12 MG1655 (GenBank accession no. NC_000913.2) and Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Typhimurium strain 14028S (GenBank accession no. CP001363.1) were grown in LB medium to log phase (optical density at 600 nm [OD600] of ~0.5). Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 4°C for 5 min, and total RNA was extracted from bacterial pellets using Tri reagent (ABI) and cleaned using Qiagen RNeasy columns. Genomic DNA was removed by DNase treatment, and 16S and 23S rRNAs were eliminated using the MICROBExpress kit (ABI). Directional (i.e., strand-specific) RNA-seq libraries were prepared to maintain strand information (39) and were assayed on a Bioanalyzer 2100 system (Agilent) for quality. Each library was loaded onto a single lane of a flow cell and sequenced using the Illumina GA II platform (35 cycles) at the Yale Center for Genome Analysis. Raw sequencing reads have been deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (accession no. SRA047329.1), and Artemis-ready files are available on request.

Mapping of sequencing reads and quantitative PCR.

Sequencing reads were mapped using the software program MAQ (40) onto the published E. coli (NC_000913.2) and Salmonella Typhimurium (CP001363.1) genomes, allowing up to two mismatches per read. The number of reads mapped to each nucleotide position on each strand was obtained by parsing the MAQ pileup file using a custom Perl script, as previously described (18). The expression levels of genes were estimated by identifying the maximum number of reads that mapped to the sense and antisense strands of annotated open reading frames (ORFs). Background expression levels were calculated for 53 genes (see Table S6 in the supplemental material) that were not expressed in a previous microarray-based study in exponential-phase E. coli in LB (41). Microarray data were downloaded from the Oklahoma University E. coli Gene Expression Database (http://genexpdb.ou.edu/main/). Read depths for these genes ranged from 0 to 19. Based on these, we used a cutoff of 20 reads to designate an asRNA as expressed.

For qPCR validation of expression levels, E. coli was grown in LB medium, and RNA was extracted as described above. After DNase treatment, cDNA was prepared from 1 µg of RNA using an iScript kit (Bio-Rad). Four loci (cdd, ldcC, napF, and ompA) were selected for qPCR, which was performed using SYBR green on a LightCycler instrument (Roche). To assess the similarity between expression estimates from Illumina sequencing and qPCR, we calculated the Pearson correlation coefficient between log-transformed maximum read depth and the qPCR cycle threshold (CT), applying a one-tailed test of significance (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material).

For qPCR validation of asRNAs, three independent E. coli samples were grown in LB and RNA was extracted, as described above. After DNase treatment, cDNA was prepared from 500 ng of RNA and asRNA-specific primers using a SuperScript II reverse transcriptase kit (Invitrogen). Reaction mixtures were incubated at 50°C for 30 min, followed by enzyme inactivation at 70°C for 15 min. qPCR was performed on a Mastercycler instrument (Eppendorf), and the intraclass correlation among the replicate CT values obtained for each sample was determined using the irr package in the software environment R v2.8.0 (see Fig. S2).

Identification of antisense TSSs.

After RNA-seq reads were mapped to the respective genome, the antisense strands of all protein coding genes were scanned using a custom Perl script to identify regions with a read depth of at least 200. These genes were then manually inspected in Artemis to determine the positions of upshifts in coverage to identify putative TSSs (30) (Fig. 1). Antisense TSSs that were located at the 5′ ends of three protein-coding genes (ybaN and STM14_1994 in Salmonella, and yneJ in E. coli) were excluded from further analysis because they potentially represent the TSSs of the divergently transcribed adjacent genes.

Identification of −10 promoter elements.

DNA binding of the σ70 transcription factor is mediated by a promoter region that consists of two short motifs positioned approximately 10 and 35 bp upstream of the TSS (42). The −10 element is particularly indispensable and has a core sequence with the 6-bp consensus TATAAT (43, 44). This motif is highly degenerate, however, since promoter elements often have imperfect matches to the consensus and can be located anywhere in a window ranging from approximately 4 to 18 bp upstream of the TSS (44). Therefore, to identify potential −10 elements associated with antisense TSSs, we searched this 15-bp window for any hexamers that matched at least 4 of the 6 bp in the consensus sequence including the two most highly conserved positions, A2 and T6 (23). This approach could potentially miss some legitimate −10 elements because many documented promoters are too divergent to satisfy these criteria (45).

To produce a null expectation for the observed frequency of −10 elements, we generated 1,000,000 sets of randomly sampled antisense positions in each genome and determined the fraction of sites in each set that contained a −10 element satisfying the criteria described above.

Analysis of nucleotide sequence divergence and polymorphism.

Patterns of nucleotide divergence and polymorphism were analyzed to infer whether promoter regions regulating asRNA expression are subject to functional constraint. To calculate levels of nucleotide sequence divergence, protein-coding gene sequences containing identified antisense TSSs were extracted from the genome sequence of either E. coli (NC_000913.2) or Salmonella (CP001363.1) and aligned with orthologous sequences from the other species. Codon-based nucleotide alignments were generated by aligning translated amino acid sequences using the software program MUSCLE v3.7 and then converting them back to nucleotide sequences (46). Divergence values were calculated using third codon positions only, which are largely synonymous and thus less susceptible to selection acting on the sense-strand-encoded amino acid sequence. Alignment gaps were excluded from divergence estimates.

Average divergence levels between E. coli and Salmonella were calculated based on the distance to the antisense TSS. To test the hypothesis that purifying selection acts to constrain sequence evolution in antisense promoter regions, the divergence data were partitioned into two categories: (i) an antisense promoter region consisting of the TSS along with 50 upstream and 10 downstream nucleotides on the antisense strand and (ii) the rest of the surrounding protein-coding gene. A paired t test was implemented in R v2.8.0 to compare levels of nucleotide divergence between these two partitions. In addition, divergence data within the antisense promoter region were visualized using a sliding-window analysis with a window size of 9 bp and a step size of 1 bp.

The above comparison between E. coli and Salmonella was repeated using E. coli and its more closely related congener Escherichia fergusonii (NC_011740.1). In addition, a similar analysis was performed using the number of segregating sites in multiple alignments generated from complete genome sequences of 41 strains of E. coli (see Table S7 in the supplemental material). Note that this set of genomes included some isolates that are taxonomically placed in the genus Shigella based on their pathogenic properties but are phylogenetically nested within E. coli (47). Only genes that were present in at least 10 of the strains were included in this polymorphism analysis.

To provide a basis of comparison for the patterns of nucleotide divergence and polymorphism observed in antisense promoter regions, we identified TSSs for a set of highly expressed protein-coding mRNAs (maximum read depth of at least 200) in E. coli and Salmonella (67 and 55 loci, respectively). For this set of control loci, we extracted gene sequences along with associated 5′ regions extending 200 bp upstream of the identified TSS from the same sets of genomes described above. Nucleotide alignments were performed in MUSCLE, and sequence divergence and polymorphism values were calculated as described above, except that there was no filtering based on codon position for upstream noncoding sequences. Genes with unalignable upstream regions were excluded from the analysis.

For both interspecific and intraspecific comparisons, putative orthologs were identified as pairs of genes that returned top hits in reciprocal searches between a pair of genomes with NCBI tBLASTn v2.2.24 (48). All analyses were conducted with custom Perl scripts utilizing BioPerl modules (49).

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

Validation by qPCR of asRNA expression levels estimated by RNA-seq. Threshold cycle value for 18 asRNAs is strongly correlated with maximum read coverage. RNA-seq and qPCR values are provided. Download Figure S1, EPS file, 1.1 MB.

Estimates of asRNA expression from multiple E. coli samples are highly reproducible. Correlation between qPCR threshold cycle (CT) values measured for 18 asRNAs from three independent E. coli samples is shown. Download Figure S2, EPS file, 0.7 MB.

Expression of previously annotated asRNAs in E. coli.

Accuracy of TSSs mapped in E. coli by RNA-seq.

E. coli genes containing asRNAs on their noncoding strands.

Salmonella Typhimurium genes containing asRNAs on their noncoding strands.

Overlap of previously detected asRNAs in E. coli.

E. coli genes used to determine background expression level.

Genomes examined for polymorphism analysis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Cindy Barlan for technical help and Kim Hammond for assistance with figures.

This work was supported in part by NIH grant GM74738 to H.O. D.B.S. was supported by an NIH Ruth Kirschstein postdoctoral fellowship (1F32GM099334-01).

Footnotes

Citation Raghavan R, Sloan DB, Ochman H. 2012. Antisense transcription is pervasive but rarely conserved in enteric bacteria. mBio 3(4):e00156-12. doi:10.1128/mBio.00156-12.

REFERENCES

- 1. Tomizawa J, Itoh T, Selzer G, Som T. 1981. Inhibition of ColE1 RNA primer formation by a plasmid-specified small RNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 78:1421–1425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Stougaard P, Molin S, Nordström K. 1981. RNAs involved in copy-number control and incompatibility of plasmid R1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 78:6008–6012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Simons RW, Kleckner N. 1983. Translational control of IS10 transposition. Cell 34:683–691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gerdes K, et al. 1986. Mechanism of postsegregational killing by the hok gene product of the parB system of plasmid R1 and its homology with the relF gene product of the E. coli relB operon. EMBO J. 5:2023–2029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Krinke L, Wulff DL. 1987. OOP RNA, produced from multicopy plasmids, inhibits lambda cII gene expression through an RNase III-dependent mechanism. Genes Dev. 1:1005–1013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Selinger DW, et al. 2000. RNA expression analysis using a 30 base pair resolution Escherichia coli genome array. Nat. Biotechnol. 18:1262–1268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Thomason MK, Storz G. 2010. Bacterial antisense RNAs: how many are there, and what are they doing? Annu. Rev. Genet. 44:167–188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Georg J, Hess WR. 2011. cis-antisense RNA, another level of gene regulation in bacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 75:286–300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dornenburg JE, Devita AM, Palumbo MJ, Wade JT. 2010. Widespread antisense transcription in Escherichia coli. mBio 1(1):e00024-10 http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/mBio.00024-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sharma CM, et al. 2010. The primary transcriptome of the major human pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Nature 464:250–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mitschke J, et al. 2011. An experimentally anchored map of transcriptional start sites in the model cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC6803. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108:2124–2129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Opdyke JA, Kang JG, Storz G. 2004. GadY, a small-RNA regulator of acid response genes in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 186:6698–6705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kawano M, Aravind L, Storz G. 2007. An antisense RNA controls synthesis of an SOS-induced toxin evolved from an antitoxin. Mol. Microbiol. 64:738–754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fozo EM, Hemm MR, Storz G. 2008. Small toxic proteins and the antisense RNAs that repress them. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 72:579–589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lee EJ, Groisman EA. 2010. An antisense RNA that governs the expression kinetics of a multifunctional virulence gene. Mol. Microbiol. 76:1020–1033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mendoza-Vargas A, et al. 2009. Genome-wide identification of transcription start sites, promoters and transcription factor binding sites in E. coli. PLoS One 4:e7526 http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0007526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rutherford K, et al. 2000. Artemis: sequence visualization and annotation. Bioinformatics 16:944–945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Perkins TT, et al. 2009. A strand-specific RNA-Seq analysis of the transcriptome of the typhoid bacillus Salmonella typhi. PLoS Genet. 5:e1000569 http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hansen KD, Brenner SE, Dudoit S. 2010. Biases in Illumina transcriptome sequencing caused by random hexamer priming. Nucleic Acids Res. 38:e131 http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkp868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Raghavan R, Groisman EA, Ochman H. 2011. Genome-wide detection of novel regulatory RNAs in E. coli. Genome Res. 21:1487–1497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Raghavan R, Sage A, Ochman H. 2011. Genome-wide identification of transcription start sites yields a novel thermosensing RNA and new cyclic AMP receptor protein-regulated genes in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 193:2871–2874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Keseler IM, et al. 2011. EcoCyc: a comprehensive database of Escherichia coli biology. Nucleic Acids Res. 39:D583–D590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Huerta AM, Francino MP, Morett E, Collado-Vides J. 2006. Selection for unequal densities of sigma70 promoter-like signals in different regions of large bacterial genomes. PLoS Genet. 2:e185 http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.0020185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Froula JL, Francino MP. 2007. Selection against spurious promoter motifs correlates with translational efficiency across bacteria. PLoS One 2:e745 http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0000745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Arthur RK, Ruvinsky I. 2011. Evidence that purifying selection acts on promoter sequences. Genetics 189:1121–1126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Stone JR, Wray GA. 2001. Rapid evolution of cis-regulatory sequences via local point mutations. Mol. Biol. Evol. 18:1764–1770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hahn MW, Stajich JE, Wray GA. 2003. The effects of selection against spurious transcription factor binding sites. Mol. Biol. Evol. 20:901–906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ohta T. 1992. The nearly neutral theory of molecular evolution. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 23:263–286 [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lynch M. 2007. The origins of genome architecture. Sinauer Associates Inc, Sunderland, MA [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nicolas P, et al. 2012. Condition-dependent transcriptome reveals high-level regulatory architecture in Bacillus subtilis. Science 335:1103–1106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lasa I, et al. 2011. Genome-wide antisense transcription drives mRNA processing in bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108:20172–20177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Shearwin KE, Callen BP, Egan JB. 2005. Transcriptional interference—a crash course. Trends Genet. 21:339–345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Horler RS, Vanderpool CK. 2009. Homologs of the small RNA SgrS are broadly distributed in enteric bacteria but have diverged in size and sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 37:5465–5476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Yu YT, Yuan X, Velicer GJ. 2010. Adaptive evolution of an sRNA that controls Myxococcus development. Science 328:993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. He BZ, Holloway AK, Maerkl SJ, Kreitman M. 2011. Does positive selection drive transcription factor binding site turnover? A test with Drosophila cis-regulatory modules. PLoS Genet. 7:e1002053 http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1002053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ames RM, Lovell SC. 2011. Diversification at transcription factor binding sites within a species and the implications for environmental adaptation. Mol. Biol. Evol. 28:3331–3344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hershberg R, Petrov DA. 2010. Evidence that mutation is universally biased towards AT in bacteria. PLoS Genet. 6:e1001115 http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1001115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hildebrand F, Meyer A, Eyre-Walker A. 2010. Evidence of selection upon genomic GC-content in bacteria. PLoS Genet. 6:e1001107 http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1001107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lister R, et al. 2008. Highly integrated single-base resolution maps of the epigenome in Arabidopsis. Cell 133:523–536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Li H, Ruan J, Durbin R. 2008. Mapping short DNA sequencing reads and calling variants using mapping quality scores. Genome Res. 18:1851–1858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Khankal R, Chin JW, Ghosh D, Cirino PC. 2009. Transcriptional effects of CRP* expression in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Eng. 3:13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Gruber TM, Gross CA. 2003. Multiple sigma subunits and the partitioning of bacterial transcription space. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 57:441–466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Pribnow D. 1975. Nucleotide sequence of an RNA polymerase binding site at an early T7 promoter. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 72:784–788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Huerta AM, Collado-Vides J. 2003. Sigma70 promoters in Escherichia coli: specific transcription in dense regions of overlapping promoter-like signals. J. Mol. Biol. 333:261–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lisser S, Margalit H. 1993. Compilation of E. coli mRNA promoter sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 21:1507–1516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Edgar RC. 2004. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 32:1792–1797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Pupo GM, Lan R, Reeves PR. 2000. Multiple independent origins of Shigella clones of Escherichia coli and convergent evolution of many of their characteristics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:10567–10572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Camacho C, et al. 2009. BLAST+: architecture and applications. BMC Bioinformatics 10:421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Stajich JE, et al. 2002. The Bioperl toolkit: Perl modules for the life sciences. Genome Res. 12:1611–1618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Validation by qPCR of asRNA expression levels estimated by RNA-seq. Threshold cycle value for 18 asRNAs is strongly correlated with maximum read coverage. RNA-seq and qPCR values are provided. Download Figure S1, EPS file, 1.1 MB.

Estimates of asRNA expression from multiple E. coli samples are highly reproducible. Correlation between qPCR threshold cycle (CT) values measured for 18 asRNAs from three independent E. coli samples is shown. Download Figure S2, EPS file, 0.7 MB.

Expression of previously annotated asRNAs in E. coli.

Accuracy of TSSs mapped in E. coli by RNA-seq.

E. coli genes containing asRNAs on their noncoding strands.

Salmonella Typhimurium genes containing asRNAs on their noncoding strands.

Overlap of previously detected asRNAs in E. coli.

E. coli genes used to determine background expression level.

Genomes examined for polymorphism analysis.