Abstract

Anorexia nervosa is a serious mental illness that affects women and men of all ages. Despite the gravity of its chronic morbidity, risk of premature death, and societal burden, the evidence base for its treatment—especially in adults—is weak. Guided by the finding that family-based interventions confer benefit in the treatment of anorexia nervosa in adolescents, we developed a cognitive-behavioral couple-based intervention for adults with anorexia nervosa who are in committed relationships that engages both the patient and her/his partner in the treatment process. This article describes the theoretical rationale behind the development of Uniting Couples in the treatment of Anorexia nervosa (UCAN), practical considerations in delivering the intervention, and includes reflections from the developers on the challenges of working with couples in which one member suffers from anorexia nervosa. Finally, we discuss future applications of a couple-based approach to the treatment of adults with eating disorders.

Keywords: eating disorders, anorexia nervosa, couple therapy, psychotherapy, cognitive-behavioral

The interpersonal context of anorexia nervosa

Anorexia nervosa (AN) is a serious and perplexing psychiatric disorder that strikes females and males of all ages. Briefly, AN is marked by low body weight, fear of weight gain, and disturbance in the way in which one’s body size is perceived, denial of illness, or undue influence of weight on self-evaluation. Demographic trends in AN are changing. No longer just the province of young females, women and men of all ages are presenting with the disorder and posing new treatment challenges as the impact of AN on families and partners varies depending on the age and interpersonal situation of the patient.

Family members and partners are deeply challenged to understand how their loved one can starve before their eyes. Complicated by high comorbidity (Fernandez-Aranda et al., 2007; Godart, Flament, Perdereau, & Jeammet, 2002; Halmi et al., 1991; Kaplan, 1993; Katzman, 2005; Kaye et al., 2004; Sharp & Freeman, 1993), around 25% of individuals with AN develop a chronic, relapsing course (Berkman, Lohr, & Bulik, 2007). It is rarely appreciated that AN ranks among the ten leading causes of disability in young women (Mathers, Vos, Stevenson, & Begg, 2000) and has the highest mortality rate of any psychiatric disorder (Birmingham, Su, Hlynsky, Goldner, & Gao, 2005; Millar et al., 2005; Papadopoulos, Ekbom, Brandt, & Ekselius, 2009; Sullivan, 1995; Zipfel, Lowe, Reas, Deter, & Herzog, 2000). Individuals with AN are 57 times more likely to commit suicide than individuals in the general population (Keel et al., 2003).

These statistics allow one to envision the devastating and often long-term effect that AN can have on families and partners. AN is associated with considerable and prolonged caregiver stress. People with AN become more dependent on their families and partners, both financially and emotionally, as AN is associated with loss of employment or underemployment and social isolation due to weight loss, malnourishment, and high treatment utilization (Treasure et al., 2001). Caregiving for AN is reported to be more stressful than for bulimia nervosa (Santonastaso, Saccon, & Favaro, 1997) and schizophrenia (Treasure, et al., 2001). Disorder specific factors including managing difficult eating behaviors such as refusal to eat and purging, dependency of the patient on the caregiver, relapse, chronicity, secrecy, stigma, and cost of treatment are particularly challenging for families and partners (Santonastaso, et al., 1997; Treasure, et al., 2001; Treasure, Whitaker, Todd, & Whitney; Whitney et al., 2005). Partners report an array of emotional responses to dealing with a loved one with AN including anger, grief, shame, anxiety, depression, and guilt.

Again defying stereotypes, individuals with AN enter into committed relationships at rates comparable to healthy peers (Maxwell et al., 2011). Over 70% of women with AN aged 31-40 report being married, separated, divorced, or in de facto relationships indicating that at some point in their adult lives, they are in committed relationships. Recovered patients identify a supportive relationship as a key “driving force” in recovery (Tozzi, Sullivan, Fear, McKenzie, & Bulik, 2003). Likewise, a distressed, critical, or hostile relationship elevates the risk for illness persistence and relapse in many psychiatric disorders (Hooley & Hiller, 2001). Unfortunately, adults with eating disorders often report difficulties and distress in their marriages or committed relationships (Van den Broucke, Vandereycken, & Vertommen, 1995a, 1995b; Woodside, Lackstrom, & Shekter-Wolfson, 2000). Women with AN who are in relationships report longer duration of illness, a greater number of past treatments, and greater eating disorder pathology (i.e., vomiting frequency) than those without stable partners (Bussolotti et al., 2002). Thus, focusing treatment on individuals with AN who have partners includes a substantial portion of adults with AN and a group with severe pathology.

Few empirically supported treatments for anorexia nervosa in adults exist

Despite the gravity of its morbidity, risk of premature death, and societal burden (Birmingham, et al., 2005; Mathers, et al., 2000; Millar, et al., 2005; Papadopoulos, et al., 2009; Sullivan, 1995; Zipfel, et al., 2000), the evidence base for the treatment of AN—especially in adults—is weak (Berkman et al., 2006; NICE, 2004). Hospitalization is recommended by the American Psychiatric Association for adults with AN who are at or below 75% of their ideal body weight (American Psychiatric Association, 2006). Although successful at achieving gains of 2-4 lbs. per week (Lund et al., 2009), this approach is costly (Krauth, Buser, & Vogel, 2002; McKenzie & Joyce, 1992) (~$1500-$2000/day) averaging $24,394 per inpatient stay (Nozoe et al., 1995; Striegel-Moore, Leslie, Petrill, Garvin, & Rosenheck, 2000; Wiseman, Sunday, Klapper, Harris, & Halmi, 2001). Moreover, weight gain is only the beginning of treatment for AN. The pernicious cognitive and emotional symptoms of AN persist after initial weight gain, necessitating ongoing care (Carter et al., 2009; Pike, Loeb, & Vitousek, 1996; Pike, Walsh, Vitousek, Wilson, & Bauer, 2003). Ultimately, ~35-42% of AN patients relapse (Carter, Blackmore, Sutandar-Pinnock, & Woodside, 2004; Carter, et al., 2009; Pike, 1998; Strober, Freeman, & Morrell, 1997) within the first 12-18 months following discharge (Carter, et al., 2004; Herzog et al., 1999; Isager, Brinch, Kreiner, & Tolstrup, 1985; Pike, 1998), placing additional caregiver and financial burden on families and partners. Readmission exerts exorbitant financial and emotional burdens on patients, families, and insurers.

A critical additional point is that drop-out in clinical trials for adult AN is unacceptably high: ~40% in medication trials and ~25% in behavioral trials (Berkman, et al., 2006). Clinical trials for adolescent AN report lower drop-out rates (10%-20%) which has been attributed to parents’ ability to compel a child’s treatment (Halmi, 2008). An alternative explanation is that family engagement may enhance patients’ motivation to remain in treatment and recover. Whether engaging partners in treatment could have a similar effect on treatment retention is a question that is addressed by our couple-based approach.

The evolving role of the family in treatment for anorexia nervosa

After an unfortunate history of blaming families and excluding families from the treatment of AN, there has been a 180 degree reversal in the role of family members in the treatment and recovery process. Family-based treatment (FBT) has shown considerable promise in treating younger AN patients (Couturier, Isserlin, & Lock, 2010; Doyle, Le Grange, Loeb, Doyle, & Crosby, 2010; Eisler et al., 2000; Eisler et al., 1997; I. Eisler, Simic, Russell, & Dare, 2007; Lock, 2002; Lock, Agras, Bryson, & Kraemer, 2005; Lock, Couturier, & Agras, 2006; Lock, Couturier, Bryson, & Agras, 2006; Lock, Le Grange, Agras, & Dare, 2001; Loeb et al., 2007; Paulson-Karlsson, Engström, & Nevonen, 2009; Russell, Szmukler, Dare, & Eisler, 1987), is acceptable by both patients and parents (Couturier, et al., 2010; Krautter & Lock, 2004), and therapeutic alliance is commonly rated as strong (Pereira, Lock, & Oggins, 2006). Family therapy techniques have been applied to samples of both adolescents and adults with AN (Crisp et al., 1991; Dare, Eisler, Russell, Treasure, & Dodge, 2001; Eisler, et al., 2000; Eisler, et al., 1997; Geist, Heinmaa, Stephens, Davis, & Katzman, 2000; Gowers, Norton, Halek, & Crisp, 1994; Robin, Siegel, Koepke, Moye, & Tice, 1994; Robin, Siegel, & Moye, 1995; Russell, et al., 1987). Overall, family therapy that includes parents of the patient appears to be most effective for younger patients with earlier onset than for older patients with a more chronic course (Eisler, et al., 1997; Russell, et al., 1987). A particular form of family therapy, the Maudsley method in which parents take initial control of renourishment of their ill child, has garnered both empirical support and popular enthusiasm (Lock, et al., 2001). This form of therapy is currently being tested in older adolescent and young adult patients (le Grange, personal communication). However, with adult patients in committed romantic relationships, this model—in which the partner takes control of re-nutrition—may not be an optimal approach. Placing the patient’s partner in a position of control over the patient’s eating has the potential to disrupt egalitarian relationships typifying many romantic relationships and contribute to power/control inequities and struggles. Thus, including a partner in treatment must take into account differences between a parent/child and romantic partner relationship.

Nonetheless, we appreciate the substantial value that enlisting family members in treatment has for youth with AN and have attempted to recreate that support structure by developing an intervention that included partners in the treatment of adults with AN. Our couple-based intervention for adult AN entitled Uniting Couples (in the treatment of) Anorexia Nervosa (UCAN), leverages the centrality of interpersonal relationships in a developmentally appropriate manner to address the treatment challenges of AN (Bulik, Baucom, Kirby, & Pisetsky, 2011).

Conceptual basis of UCAN

In selecting a couple-based intervention to integrate into the treatment of AN, we considered several factors. First, we were committed to adapting a couple-based approach that has strong empirical support across a number of patient populations, beyond treating relationship distress per se. Second, we sought an approach that would teach couples specific skills and provide them with concrete strategies for addressing AN together as a team. Third, any approach we developed would have to integrate well with the patient’s individual treatment in order to provide consistent perspectives and approaches across providers. Cognitive-behavioral couple therapy (CBCT) fulfilled all of these criteria. CBCT, the most widely researched couple intervention (Baucom & Epstein, 1990), targets relationship functioning by teaching partners communication and problem-solving skills, enhancing understanding of relationship interactions, and addressing emotions adaptively. CBCT promotes concrete behavioral change to increase the frequency of specific positive interactions while minimizing targeted negative exchanges. CBCT is consistently more efficacious than a waiting list control in improving marital functioning (Baucom, Hahlweg, & Kuschel, 2003; Baucom, 1982, 1986; Baucom, Sayers, & Sher, 1990; Hahlweg, Revenstorf, Schindler, & Brengelmann, 1982; Jacobson et al., 1984; Snyder & Wills, 1989). The application of CBCT to mental illness recognizes the social context in which psychopathology presents and argues that effective intervention necessarily includes working within the natural social environment (e.g., the partner) to optimize change. Intervening at the couple-level promotes changes crucial for the reduction of illness behavior. CBCT has been used successfully with several medical (Baucom et al., 2005; Keefe et al., 2005; Keefe et al., 2004; Porter et al., 2009) and psychiatric disorders (Baucom, Shoham, Mueser, Daiuto, & Stickle, 1998), including two highly comorbid with AN—depression and anxiety (Arnow, Taylor, Agras, & Telch, 1985; Beach & O’Leary, 1992; Cobb, Mathews, Childs-Clarke, & Bowers, 1984; Emanuels-Zuurveen & Emmelkamp, 1996; Emmelkamp, de Haan, & Hoodguin, 1990; Emmelkamp & de Lange, 1983; Emmelkamp et al., 1992; Hand, Angenendt, Fischer, & Wilke, 1986; Jacobson, Dobson, Fruzzetti, Schmaling, & Salusky, 1991; Leff et al., 2000; Mehta, 1990; O’Leary & Beach, 1990; Oatley & Hodgson, 1987). CBCT also has demonstrated efficacy in couples in which one member has problems with emotion dysregulation (Kirby & Baucom, 2007). Whereas many partners are willing and eager to assist their loved ones with AN, they report not knowing how to do so and fear exacerbating the illness. UCAN assists the couple with developing a clear blueprint of how to engage the partner meaningfully in treating AN.

Developing UCAN

To develop and implement a couple-based intervention for AN required knowledge and expertise in several domains represented by the current authors. First, expertise in the treatment of AN per se was needed so that the couple could understand their goals and challenges relative to treatment (CB). Second, since this is a couple-based intervention, an understanding of broad relationship dynamics and how to intervene with couples in general was essential (DB and JK). Third, an understanding of how AN affects the couple and how couple functioning affects AN in a reciprocal manner was important in order to integrate knowledge on AN individual treatment with relationship functioning into a couple-based AN intervention (CB, BD, JK).

While accounting for the above considerations, it was also important to bear in mind that the concept of a couple-based intervention is not synonymous with couple therapy. As we have noted elsewhere (Baucom, Kirby, & Kelly, 2009; Baucom, Shoham, Mueser, Daiuto, & Stickle, 1998) couple-based interventions can assume one or a combination of three forms. First, in partner-assisted interventions the partner serves as a coach or support to the patient, assisting the patient in making changes that the patient needs to make in order to recover from the disorder (e.g., helping the patient plan routine times to eat a healthy lunch; note that this approach does not focus on the couple’s relationship per se). Second, in disorder-specific interventions, the couple’s relationship is the focus of treatment but only in domains in which couple functioning affects the disorder or the disorder affects the couple (e.g., planning how the couple can go out to eat together while minimizing subsequent purging resulting from consuming atypically high number of calories). Neither partner-assisted nor disorder-specific interventions assume that the couple has relationship distress but instead focuses on the eating disorder per se. Third, if the couple is experiencing relationship distress, then some amount of couple therapy can be required for two reasons: (a) to facilitate successful partner-assisted and disorder-specific interventions which can become disrupted by hostility or lack of cooperation between the partners, and/or (b) to alleviate relationship discord which can be a global, chronic stressor that contributes to exacerbation and maintenance of eating-disordered behavior.

We deliberated as to whether to develop UCAN as a stand-alone intervention for AN or a component of a broader multi-disciplinary intervention. Ultimately, we created UCAN to be an augmentation treatment based on the complexity of the disorder and the necessity of medical, dietary, and individual psychological treatment as documented in the treatment guidelines which underscore the need for a multi-disciplinary approach to the treatment of AN (American Psychiatric Association, 2006). Thus, we recommend a comprehensive intervention for adults with AN, that includes the couple-based component, individual cognitive-behavior therapy, medical treatment, and nutritional counseling.

UCAN is undergoing extensive testing for individuals who are in committed relationships and are living together. Patients and partners can be of any sex or sexual orientation. As an augmentation therapy, and unlike family-based treatment for adolescent AN, partners are not asked to take responsibility for monitoring patient weight and eating. This developmentally appropriate approach avoids power imbalances that could emerge if the partner were in a position of complete authority. The UCAN therapist works with each couple to tailor the optimal stance of the partner with reference to the eating disorder. Close collaboration with an individual therapist, a dietitian, and a treating psychiatrist enables UCAN to focus primarily on working with the couple towards recovery.

The UCAN model

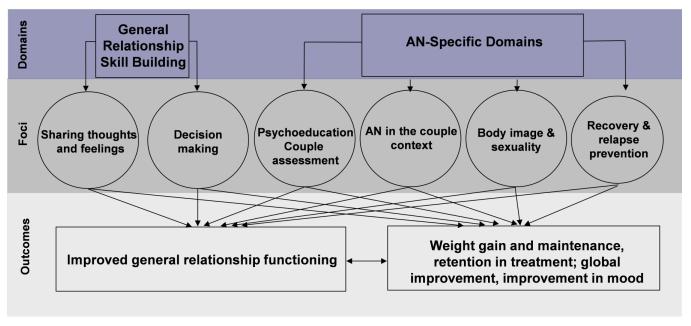

The UCAN model is presented in the figure. On the left side of the model are the general relationship functioning domains. Intervention in these areas impacts general functioning and develops fundamental couple skills to enhance their ability to address AN-specific concerns. The right side of the model includes AN-specific domains: understanding AN in the couples context (including all core AN symptoms); body image; affection and sexuality; and relapse and recovery. Partner participation in treatment contributes to change in several ways including: providing an overall source of support to the patient; reinforcing appropriate eating and other health-related behaviors while avoiding punishment; functioning effectively as a couple in addition to working individually to approach AN; and increasing comfort and acceptance of the body without providing inappropriate reassurance. AN is a stressor on relationships, and as AN improves, the overall relationship is likely to benefit as well.

Figure.

The UCAN Model.

UCAN session content

Phase one: Creating a foundation for later work

The UCAN treatment begins by helping the couple build a supportive foundation for addressing AN effectively as a team by targeting three goals: (1) understanding the couple’s experience of AN; (2) providing psychoeducation about AN and the recovery process; and (3) teaching the couple effective communication skills. At the outset of treatment, the UCAN therapist conducts an extensive assessment of the couple’s relationship history, both partners’ experience of AN, and how the eating disorder has influenced and been influenced by the couple’s relationship. The psychoeducation component consists of AN symptoms and associated comorbidities, biological and environmental risk factors, and the recovery process. By discussing this psychoeducation material with both members of the couple, UCAN works to create a comprehensive and shared understanding of AN to help foster the couple’s teamwork. This teamwork is further developed by teaching communication and problem-solving skills that are central to successful couple-based interventions. Through didactic instruction and extensive in- and out-of-session practice, the couple learns how to express thoughts and feelings, listen responsively, and solve problems/make decisions as a team. The couples’ enhanced communication skills along with their shared understanding of AN and the treatment process equip the couple to address issues central to anorexia, which are discussed in phase 2 of UCAN.

Phase two: Addressing anorexia nervosa within a couple context

Resuming a healthy body weight and developing healthy eating behaviors (e.g., avoidance of restricting and purging) are major treatment goals for individuals with AN. Phase two of UCAN parallels the patient’s efforts in individual therapy by concurrently helping the couple develop an effective support system for this individual work. With the help of their UCAN therapist, the couple is guided in a thoughtful consideration of AN features they find most challenging, and then how to employ their communication skills in responding to these challenges more effectively as a team. For example, partners can be guided in supporting the patient during meals by sitting with her/him or providing encouragement and therefore not adopting the role of food monitor. By discussing eating in a supportive way consistent with the recovery process, the couple can develop more positive interactions around eating within their relationship, which promotes the development of healthier eating and help partners feel more hopeful and better equipped to continue in the treatment process.

Phase two of UCAN broadens the AN focus to body image and sexual issues. Applying their communication skills, the couple discusses body image issues and how they can better interact around this challenging domain (e.g., how can the patient describe to the partner how she feels about her body without focusing on “ being fat;” how can the partner best respond in such instances). This begins with an in-session conversation in which the patient shares how she experiences her body image with the partner. Body image distortions and body dissatisfaction can be two of the most puzzling features of AN for the partner, so it is important that the couple has an opportunity to increase understanding and empathy for each other’s body image experiences. Once they have a greater appreciation of how each partner experienced this challenging domain, the couple can use their decision-making skills to create more effective ways of interacting around body image within their relationship.

The body image work is a natural entrée into the couple’s physical relationship. Phase two concludes with consideration of how the couple’s physical relationship can affect and be affected by the patient’s experience of negative body image and the eating disorder. Included in this exploration is how the couple experiences challenges within their physical relationship more broadly as well as specifically related to the AN. Because couples vary widely in their physical and sexual relationships, UCAN is tailored to the patient’s and couple’s current level of functioning and assists them in developing healthier patterns within their physical relationship.

Phase three: Relapse prevention and termination

Phase three of UCAN brings the treatment to a close, focusing upon relapse prevention and the couple’s next steps in the AN recovery process. Psychoeducation topics include recovery and relapse prevention, information which is then used to help the couple develop effective responses should a slip or full relapse occur. The treatment concludes with a review of the UCAN experience and a consideration of how the couple needs to continue working together toward recovery from AN.

Personal Reflections from the Developers of UCAN

In this section, we reflect on our experiences merging our two fields. The members of the team who are couple researchers and therapists (DB and JK) did not have extensive prior experience with eating disorders. The eating disorder researcher was trained in family therapy but not couple therapy. Our coming together to create UCAN was illuminating for both sides. In this next section, we describe our individual experiences with merging our fields and clinical approaches.

Reflections on the couple-based approach by the eating disorders professional (CB)

Historically and typically, partners are not systematically included in the treatment of adults with AN. Inpatient models may at best include partners at admission and discharge, in family weekends, or family meetings either face to face or by phone. Often family sessions are tailored more for parents than partners, and they inform rather than engage. The partner may be enlisted in times of crisis, to assist with financial matters, or for instrumental support; however, typically they remain in the dark about the complexities of the recovery process.

Not including partners in treatment perpetuates a culture of secrecy and maintains “no talk zones” around many aspects of the eating disorder. In many ways, allowing this secrecy to continue colludes in maintaining the disorder. In developing and piloting the UCAN trial, it became clear how poorly informed partners were about the illness. Many believed their loved ones were choosing to starve and failed to appreciate the underlying biological aspects of the illness. Most partners had preconceived expectations that recovery would be linear and had great difficulty appreciating, but also great relief when they learned, that recovery from AN was anything but a linear process. AN effectively mutes partners. Their deep concern is often trampled by the force with which the illness pummeled or scared them into silence. Partners clearly appreciated the gravity of the illness and feared for the patients’ lives, but they were often cornered into positions of learned helplessness, unable to find strategies or approaches that could “get through” to their loved one.

Traditional approaches in which the partner was not included are clearly highly frustrating and confusing for partners. The patient is hospitalized, in residential treatment, or in outpatient treatment, and none of the details of the therapeutic work is shared with the partner. The partner does not know when weight is increasing, when exchanges are being skipped, what is enough exercise, etc. They are effectively shut out of everything related to the eating disorder which permeates most aspects of life and have no idea what is therapeutic and what is not. Without guidelines partners remain deeply fearful that no matter what they say, they will do harm. AN mutes them and rules the relationship.

A useful parallel to consider is a patient with diabetes. Imagine if the partner had no information about what caused diabetes, what was an appropriate diet, when insulin or glucagon was required, and what a diabetic crisis looked like. The partner would live in constant fear and be ill-prepared to deal with the medical crises that would emerge if the patient was non-compliant with treatment recommendations. With no point of reference or anchor in “normality,” partners of individuals with AN simply have no idea what patients need to eat to maintain weight, how they need to curtail exercise, or how damaging laxative use can be, for example. Precisely because they love and care for the patient, they struggle with when to believe them and when to challenge. AN erodes the basic trust essential to a healthy relationship.

Partners also sacrificed their own health for the well-being of the patient. Many partners gained weight as they attempted to “eat with” the patient, hoping that this joint activity would encourage her to eat more. Others stopped exercising because the patients would be envious of their time at the gym or compete for who exercised more. Other partners became completely exhausted by not only having to be the primary or sole wage earner, but also taking over all shopping, cooking, and family feeding activities because they were too triggering for the patient. We have done a disservice to partners for years by not appreciating the magnitude of their co-suffering and proving them with a blueprint for dealing with AN.

One heartening observation from the UCAN trial is the dedication that the partners showed to the patients and their recovery. These partners gave their all once they knew what and how to give. In most cases, their love and dedication survived the challenges posed to the relationship by the complexities of the illness. For some, the distrust, secrecy, and distance were simply too pervasive to recover from. Occasionally AN creates irreparable damage to relationships arguing for earlier rather than later partner involvement in treatment.

Hopefully the inclusion of the partner in treatment also can help to address a major challenge in treating AN, a high rate of treatment drop-out and premature discontinuation. In part this high drop-adult in adults stems from patient ambivalence about recovery and deep-seated fear and discomfort with weight gain. Unlike other forms of psychopathology in which the patient is eager to achieve symptom remission, individuals with AN desperately cling to the starvation state. Theoretically, many believe this is because food restriction and exercise serve an anxiolytic role in these individuals who tend to be temperamentally anxious and dysphoric. Our treatments and the weight gain that entails, rather than leading to a greater sense of calm and decreased anxiety, actually can increase anxiety and dysphoria until other approaches at emotion regulation can be effectively implemented. We have observed that engaging the partners in treatment is clearly associated with lower drop-out. Their presence can help the patient keep her “eye on the prize” and weather the temporary discomfort and recrudescence of anxiety associated with renutrition and weight gain with an eye towards biological normalization and the eventual ability to manage anxiety and dysphoria by more effective means than starvation. There were many points during the UCAN clinical trial where, had patients been in individual therapy, we may never have seen them in the clinic again. But the partners, after already putting so much effort into team recovery, played an active role in keeping the patients in treatment. Remaining in treatment is a critical outcome for the treatment of adult AN and perhaps the greatest contribution of the UCAN approach.

Reflections on anorexia nervosa by the couple intervention team (DB, JK)

Providing a couple-based intervention for AN results in several challenges, some inherent to treating AN, and some more unique to the couple intervention format. First helping the couple work together to treat AN is complicated by the fact that there are no established efficacious interventions for adult AN. In many instances, our couple-based interventions for individual psychopathology build upon well-established, efficacious individual treatments, attempting to make these interventions more robust and with greater maintenance of gains by including a partner. For example, in a different context, DB is involved in evaluating a couple-based intervention for obsessive- compulsive disorder (OCD). Exposure and response prevention has been demonstrated to be a highly efficacious individual intervention for OCD. Our couple-based interventions build upon this strategy, having the partner assist in exposure outings, helping the couple incorporate exposure to anxiety-provoking aspects of life into their everyday routines in an informal fashion, and helping the partner understand how to avoid providing inappropriate, anxiety-reducing strategies such as providing reassurance to the patient. Because such well-documented individual interventions for AN have not been demonstrated, what to include in couple-based interventions for AN is less certain and must build upon the current state of the field, even though limited.

Second, as noted previously, the couple therapist is only one of several persons providing psychosocial intervention for the patient, with involvement from an individual therapist, dietitian, and psychiatrist. For many couple therapists, this is an atypical treatment context. In many of our previous interventions for psychopathology (e.g., anxiety disorders) or health concerns (e.g., osteoarthritis, cancer, cardiovascular disease), the couple-based intervention is the sole psychosocial intervention. In treating AN, there must there be frequent, ongoing communication among all these treatment providers in order to clarify roles and maintain a consistent treatment approach across providers. In addition, the couple therapist must become comfortable with the world of hospitals and, perhaps, eating disorder programs. Due to rapid psychological deterioration or complicating medical conditions, at times patients with AN need a high level of care such as partial hospitalization or inpatient treatment, and such decisions need to be made quickly. The couple therapist must learn how to function in this complex medical system that requires rapid communication and response. This is in contrast to many couple-based interventions in other contexts in which the therapist sees the couple weekly, with little communication or coordination between sessions.

Third, a major complicating factor in a couple-based intervention for AN results from the fact that many patients with AN are not motivated to recover or at least have strong ambivalence regarding making eating-related changes. This is a complicating factor in treating AN in general but poses additional challenges in a couple-based intervention. In a couple-based intervention, a partner’s role is to help a patient make needed changes. However, this becomes difficult if the patient does not want to make these changes. Contrasting goals between the two members of the couple in terms of eating-related changes runs the risk that their interactions might come adversarial and a power struggle can ensue. That is, the patient can experience the partner is attempting to control the patient’s eating behaviors. Given that the theme of control is central to many individuals with AN (Bruch, 1980), this can provide a context for reactance from the patient who feels the need to assert her autonomy and challenge her partner’s attempts to change her eating behavior. This can solidify her commitment to maintain her eating disorder and shut her partner out of the process. Our experience is that a skilled couple therapist can address these issues and help the couple avoid control and power issues relating to eating, but it is a complex and challenging issue even for a skilled therapist.

Clinical issues and observations

There is a great deal of variability among couples in which one partner has AN. Whereas we do not yet have sufficient empirical evidence to clarify which couples will benefit most from UCAN, we have observed both individual and relationship factors that might alter the duration of treatment needed or could interfere with optimal treatment gains unless these issues are handled skillfully.

Regarding relationship factors, the ease with which the partners can work as a team around the challenges of AN and their level of relationship adjustment vary considerably across couples. High relationship distress with negative, critical comments can affect whether the person with AN is comfortable or willing to share intimate details about AN. Also an angry or resentful partner may have difficulty empathizing with the patient regarding struggles around AN. This does not suggest that relationship distress contraindicates UCAN, although it can make the treatment more challenging. On the other hand, giving the couple a specific targeted area such as AN to address as a couple can provide them with an opportunity to work together as an effective team which can potentially generalize to other areas of relationship functioning. For example, our couple-based investigation in which one partner experienced severe emotion dysregulation resulted in a notable increase in partners’ relationship satisfaction at the end of treatment and at follow-up (Kirby & Baucom, 2007). Also, in our work with cardiac patients, our couple-based intervention was particularly beneficial to more maritally distressed couples in promoting health behavior changes (Sher, et al. 2011). Whereas both the couple and the therapist can be challenged by a high level of relationship distress in addressing the patient’s AN, UCAN holds promise not only in addressing AN, but also has the potential to improve general relationship functioning.

Individual factors in both partners also appear to influence the implementation and experience of UCAN. AN is commonly comorbid with depression and anxiety, and these comorbidities also become a target of treatment. Skilled therapists address these concerns as they influence the ability of the patient and couple to address AN or impact long term change and maintenance. In addition, Axis II symptomatology (in particular, difficulty regulating emotions) or characteristics mimicking Axis II pathology (that may be described more accurately as exacerbations of traits secondary to starvation), can interfere with a smooth course of treatment. When difficult issues arise in treatment, patients experiencing emotion dysregulation might skip sessions, avoid interacting with the treatment team, decide to drop out of treatment (at least temporarily), increase eating-disordered behavior (e.g., purging), or engage in other maladaptive emotion regulation behaviors such as heavy alcohol use. Emotion dysregulation occurs not only when specifically addressing eating-related issues; in addition, it can be triggered by other topics intertwined with AN, such as addressing physical affection and sexuality. Support from a skilled UCAN therapist, along with an integrated response from the full treatment team, often can assist the couple and patient during these difficult times in treatment.

The future of treatment for adult eating disorders

The current state of treatment for adults with AN is of widespread concern. Based on the results of published clinical trials, the options are few; results are unacceptably poor, and treatment dropout is exceedingly high. Should UCAN prove to be efficacious, it has the potential to change the standard care for the many adults with AN with partners. Ultimately, if the addition of UCAN to standard individual treatment proves to be superior to individual approaches alone in reducing core AN pathology, enhancing couple functioning, and maximizing retention in treatment, we would be on solid footing to propose changes to treatment guidelines for adults with AN. In addition, we would be well positioned to consider adapting UCAN for bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder, and, ultimately, test their effectiveness in the community. As the research progresses, however, our clinical observations clearly suggest that the systematic inclusion of partners in the treatment process is of enormous value—to the patient, the partner, and the relationship.

Footnotes

Cynthia Bulik, Department of Psychiatry and Nutrition, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Donald Baucom and Jennifer Kirby, Department of Psychology, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health Grants (R01 MH082732). We also thank all of the participating couples and our project coordinator Emily Pisetsky, M.A.

References

- American Psychiatric Association Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Eating Disorders Third Edition. 2006 from http://www.psychiatryonline.com/pracGuide/loadGuidelinePdf.aspx?file=EatingDisorders3ePG_04-28-06.

- Arnow B, Taylor C, Agras W, Telch M. Enhancing agoraphobia treatment outcome by changing couple communication patterns. Behavior Therapy. 1985;16:452–467. [Google Scholar]

- Baucom D, Hahlweg K, Kuschel A. Are waiting-list control groups needed in future marital therapy outcome research? Behavior Therapy. 2003;34:179–188. [Google Scholar]

- Baucom DH. A comparison of behavioral contracting and problem-solving/communications training in behavioral marital therapy. Behavior Therapy. 1982;13:162–174. [Google Scholar]

- Baucom DH. Treatment of marital distress from a cognitive behavioral perspective; Paper presented at the annual conference of the North Carolina Psychological Association; Asheville, NC. 1986, October. [Google Scholar]

- Baucom DH, Epstein N. Cognitive-behavioral marital therapy. Brunner/Mazel; New York, NY: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Baucom DH, Heinrichs N, Scott JL, Gremore TM, Kirby JS, Zimmermann T, Keefe FJ. Couple-based interventions for breast cancer: Findings from three continents; Paper presented at the 39th Annual Convention of the Assocation for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies; Washington, D.C. 2005, November. [Google Scholar]

- Baucom DH, Kirby JS, Kelly JT. Couple-based interventions to assist partners with psychological and medical problems. In: Hahlweg K, Grawe M, Baucom DH, editors. Enhancing couples: The shape of couple therapy to come. Göttingen; Hogrefe: 2009. pp. 79–93. [Google Scholar]

- Baucom DH, Sayers SL, Sher TG. Supplementing behavioral marital therapy with cognitive restructuring and emotional expressiveness training: an outcome investigation. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1990;58:636–645. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.58.5.636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baucom DH, Shoham V, Mueser KT, Daiuto AD, Stickle TR. Empirically supported couple and family interventions for marital distress and adult mental health problems. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:53–88. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.1.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baucom DH, Shoham V, Mueser KT, Daiuto AD, Stickle TR. Empirically supported couples and family therapies for adult problems. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:53–88. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.1.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beach SRH, O’Leary KD. Treating depression in the context of marital discord: Outcome and predictors of response of marital therapy versus cognitive therapy. Behavior Therapy. 1992;23:507–528. [Google Scholar]

- Berkman N, Bulik C, Brownley K, Lohr K, Sedway J, Rooks A, Gartlehner G. Management of Eating Disorders. Rockville, MD: 2006. Management of Eating Disorders. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No. 135. AHRQ Publication No. 06-E010. (Prepared by the RTI International-University of North Carolina Evidence-Based Practice Center under Contract No. 290-02-0016.) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkman ND, Lohr KN, Bulik CM. Outcomes of eating disorders: A systematic review of the literature. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2007;40:293–309. doi: 10.1002/eat.20369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birmingham C, Su J, Hlynsky J, Goldner E, Gao M. The mortality rate from anorexia nervosa. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2005;38:143–146. doi: 10.1002/eat.20164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruch H. Predonditions for the development of anorexia nervosa. American Journal of Psychoanalysis. 1980;40:169–172. doi: 10.1007/BF01254810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulik CM, Baucom DH, Kirby JS, Pisetsky E. Uniting couples (in the treatment of) anorexia nervosa (UCAN) International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2011;44:19–28. doi: 10.1002/eat.20790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bussolotti D, Fernandez-Aranda F, Solano R, Jimenez-Murcia S, Turon V, Vallejo J. Marital status and eating disorders: an analysis of its relevance. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2002;53:1139–1145. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00336-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter J, Blackmore E, Sutandar-Pinnock K, Woodside D. Relapse in anorexia nervosa: a survival analysis. Psychological Medicine. 2004;34:671–679. doi: 10.1017/S0033291703001168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter JC, McFarlane TL, Bewell C, Olmsted MP, Woodside DB, Kaplan AS, Crosby RD. Maintenance treatment for anorexia nervosa: A comparison of cognitive behavior therapy and treatment as usual. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2009;42:202–207. doi: 10.1002/eat.20591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobb J, Mathews A, Childs-Clarke A, Bowers C. The spouse as a cotherapist in the treatment of agoraphobia. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1984;144:282–287. doi: 10.1192/bjp.144.3.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couturier J, Isserlin L, Lock J. Family-based treatment for adolescents with anorexia nervosa: a dissemination study. Eating Disorders. 2010;18:199–209. doi: 10.1080/10640261003719443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crisp A, Norton K, Gowers S, Halek C, Bowyer C, Yeldham D, Bhat A. A controlled study of the effect of effect of therapies aimed at adolescent and family psychopathology in anorexia nervosa. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1991;159:325–333. doi: 10.1192/bjp.159.3.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dare C, Eisler I, Russell G, Treasure J, Dodge L. Psychological therapies for adults with anorexia nervosa: randomised controlled trial of out-patient treatments. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;178:727–736. doi: 10.1192/bjp.178.3.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle PM, Le Grange D, Loeb K, Doyle AC, Crosby RD. Early response to family-based treatment for adolescent anorexia nervosa. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2010;43:659–662. doi: 10.1002/eat.20764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisler I, Dare C, Hodes M, Russell G, Dodge E, Le Grange D. Family therapy for adolescent anorexia nervosa: the results of a controlled comparison of two family interventions. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2000;41:727–736. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisler I, Dare C, Russell G, Szmukler G, le Grange D, Dodge E. Family and individual therapy in anorexia nervosa. A 5-year follow-up. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1997;54:1025–1030. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830230063008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisler I, Simic M, Russell GF, Dare C. A randomised controlled treatment trial of two forms of family therapy in adolescent anorexia nervosa: a five-year follow-up. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2007;48:552–560. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01726.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emanuels-Zuurveen L, Emmelkamp PM. Individual behavioral-cognitive therapy v. marital therapy for depression in maritally distressed couples. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1996;169:181–188. doi: 10.1192/bjp.169.2.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmelkamp P, de Haan E, Hoodguin C. Marital adjustment. and obsessive-compulsive disorder. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1990;156:55–60. doi: 10.1192/bjp.156.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmelkamp P, de Lange I. Spouse involvement in the treatment of obsessivecompulsive patients. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1983;21:341–346. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(83)90002-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmelkamp P, van Dyck R, Bitter M, Heins R, Onstein E, Eisen B. Spouse-aided therapy with agoraphobics. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1992;160:51–56. doi: 10.1192/bjp.160.1.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Aranda F, Pinheiro A, Tozzi F, Thornton L, Fichter M, Halmi K, Bulik C. Symptom profile and temporal relation of major depressive disorder in females with eating disorders. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;41:24–31. doi: 10.1080/00048670601057718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geist R, Heinmaa M, Stephens D, Davis R, Katzman D. Comparison of family therapy and family group psychoeducation in adolescents with anorexia nervosa. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;45:173–178. doi: 10.1177/070674370004500208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godart N, Flament M, Perdereau F, Jeammet P. Comorbidity between eating disorders and anxiety disorders: a review. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2002;32:253–270. doi: 10.1002/eat.10096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gowers S, Norton K, Halek C, Crisp A. Outcome of outpatient psychotherapy in a random allocation treatment study of anorexia nervosa. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1994;15:165–177. doi: 10.1002/1098-108x(199403)15:2<165::aid-eat2260150208>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahlweg K, Revenstorf D, Schindler L, Brengelmann JC. Current issues in marital therapy. Analisis y Modificacion de Conducta. 1982;8:3–27. [Google Scholar]

- Halmi K, Eckert E, Marchi P, Sampugnaro V, Apple R, Cohen J. Comorbidity of psychiatric diagnoses in anorexia nervosa. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1991;48:712–718. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810320036006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halmi KA. The perplexities of conducting randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled treatment trials in anorexia nervosa patients. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2008;165:1227–1228. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08060957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hand I, Angenendt J, Fischer M, Wilke C. Exposure in-vivo with panic management for agoraphobia:Treatment rationale and longterm outcome. In: Hand I, Wittchen H, editors. Panic and Phobias. Springer; Berlin: 1986. pp. 104–128. [Google Scholar]

- Herzog D, Dorer D, Keel P, Selwyn S, Ekeblad E, Flores A, Keller M. Recovery and relapse in anorexia and bulimia nervosa: a 7.5-year follow-up study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1999;38:829–837. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199907000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooley JM, Hiller JB. Family relationships and major mental disorder: Risk factors and preventive strategies. In: Sarason BR, Duck S, editors. Personal Relationships: Implications for Clinical and Community Psychology. John Wiley; New York: 2001. pp. 61–87. [Google Scholar]

- Isager T, Brinch M, Kreiner S, Tolstrup K. Death and relapse in anorexia nervosa: survival analysis of 151 cases. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1985;19:515–521. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(85)90061-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson NS, Dobson KS, Fruzzetti AE, Schmaling KB, Salusky S. Marital therapy as a treatment for depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1991;59:547–557. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.4.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson NS, Follette WC, Revenstorf D, Baucom DH, Hahlweg K, Margolin G. Variability in outcome and clinical significance of behavioral marital therapy: a reanalysis of outcome data. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1984;52:497–504. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.52.4.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan A. Medical Aspects of Anorexia Nervosa and Bulimia Nervosa. In: Kennedy SH, editor. Handbook of Eating Disorders. University of Toronto; Toronto: 1993. pp. 22–29. [Google Scholar]

- Katzman D. Medical complications in adolescents with anorexia nervosa: a review of the literature. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2005;37:S52–59. doi: 10.1002/eat.20118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaye W, Bulik C, Thornton L, Barbarich BS, Masters K, Group PFC. Comorbidity of anxiety dsorders with anorexia and bulimia nervosa. American Jounal of Psychiatry. 2004;161:2215–2221. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.12.2215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keefe FJ, Ahles TA, Sutton L, Dalton JA, Baucom DH, Pope MS, Scipio C. Partner-guided cancer pain management at end-of-life: A preliminary study. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2005;29:263–272. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2004.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keefe FJ, Blumenthal J, Baucom DH, Affleck G, Waugh R, Caldwell D, Lefebvre JC. Effects of spouse-assisted coping skills training and exercise training in patients with osteoarthritic knee pain: A randomized controlled study. Pain. 2004;110:539–549. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keel P, Dorer D, Eddy K, Franko D, Charatan D, Herzog D. Predictors of mortality in eating disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60:179–183. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.2.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby JS, Baucom DH. Integrating dialectical behavior therapy and cognitive-behavioral couple therapy: A couples skills group for emotion dysregulation. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2007;14:394–405. [Google Scholar]

- Kirby JS, Baucom DH. Treating emotional dysregulation in a couples context: A pilot study of a couples skills group intervention. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 2007;33:375–391. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2007.00037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krauth C, Buser K, Vogel H. How high are the costs of eating disorders - anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa - for German society? European Journal of Health Economics. 2002;3:244–250. doi: 10.1007/s10198-002-0137-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krautter T, Lock J. Is manualized family-based treatment for adolescent anorexia nervosa acceptible to patients? Patient satisfaction at the end of treatment. Journal of Family Therapy. 2004;26:66–82. [Google Scholar]

- Leff J, Vearnals S, Brewin CR, Wolff G, Alexander B, Asen E, Everitt B. The London depression intervention trial. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;177:95–100. doi: 10.1192/bjp.177.2.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lock J. Treating adolescents with eating disorders in the family context. Empirical and theoretical considerations. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2002;11:331–342. doi: 10.1016/s1056-4993(01)00009-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lock J, Agras WS, Bryson S, Kraemer HC. A comparison of short- and long-term family therapy for adolescent anorexia nervosa. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2005;44:632–639. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000161647.82775.0a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lock J, Couturier J, Agras WS. Comparison of long-term outcomes in adolescents with anorexia nervosa treated with family therapy. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2006;45:666–672. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000215152.61400.ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lock J, Couturier J, Bryson S, Agras S. Predictors of dropout and remission in family therapy for adolescent anorexia nervosa in a randomized clinical trial. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2006;39:639–647. doi: 10.1002/eat.20328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lock J, Le Grange D, Agras W, Dare C. Treatment manual for anorexia nervosa: A family-based approach. Guilford Press; New York: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Loeb KL, Walsh BT, Lock J, Le Grange D, Jones J, Marcus S, Dobrow I. Open trial of family-based treatment for full and partial anorexia nervosa in adolescence: evidence of successful dissemination. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2007;46:792–800. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e318058a98e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund BC, Hernandez ER, Yates WR, Mitchell JR, McKee PA, Johnson CL. Rate of inpatient weight restoration predicts outcome in anorexia nervosa. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2009;42:301–305. doi: 10.1002/eat.20634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathers CD, Vos ET, Stevenson CE, Begg SJ. The Australian Burden of Disease Study: measuring the loss of health from diseases, injuries and risk factors. Medical Journal of Australia. 2000;172:592–596. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2000.tb124125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell M, Thornton LM, Root TL, Pinheiro AP, Strober M, Brandt H, Bulik CM. Life beyond the eating disorder: Education, relationships, and reproduction. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2011;44:225–32. doi: 10.1002/eat.20804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie JM, Joyce PR. Hospitalization for anorexia nervosa. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1992;11:235–241. [Google Scholar]

- Mehta M. A comparative study of family-based and patient-based behavioural management in obsessive-compulsive disorder. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1990;157:133–135. doi: 10.1192/bjp.157.1.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millar HR, Wardell F, Vyvyan JP, Naji SA, Prescott GJ, Eagles JM. Anorexia nervosa mortality in Northeast Scotland, 1965-1999. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;162:753–757. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.4.753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NICE 2004 http://www.nice.org.uk/page.aspx?o=101239.

- Nozoe S, Soejima Y, Yoshioka M, Naruo T, Masuda A, Nagai N, Tanaka H. Clinical features of patients with anorexia nervosa: assessment of factors influencing the duration of in-patient treatment. Addictive Behaviors. 1995;39:271–281. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(94)00141-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary KD, Beach SRH. Marital therapy: A viable treatment for depression and marital discord. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1990;147:183–186. doi: 10.1176/ajp.147.2.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oatley K, Hodgson D. Influence of husbands on the outcome of their agoraphobic wives’ therapy. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1987;150:380–386. doi: 10.1192/bjp.150.3.380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papadopoulos F, Ekbom A, Brandt L, Ekselius L. Excess mortality, causes of death and prognostic factors in anorexia nervosa. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;194:10–17. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.108.054742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulson-Karlsson G, Engström I, Nevonen L. A pilot study of a family-based treatment for adolescent anorexia nervosa: 18- and 36-month follow-ups. Eating Disorders. 2009;17:72–88. doi: 10.1080/10640260802570130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira T, Lock J, Oggins J. Role of therapeutic alliance in family therapy for adolescent anorexia nervosa. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2006;39:677–684. doi: 10.1002/eat.20303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pike K, Loeb K, Vitousek K. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. In: Thompson J, editor. Eating Disorders, Obesity, and Body Image: A Practical Guide to Assessment and Treatment. APA Books; Washington, DC: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Pike K, Walsh B, Vitousek K, Wilson G, Bauer J. Cognitive behavior therapy in the posthospitalization treatment of anorexia nervosa. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;160:2046–2049. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.11.2046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pike KM. Long-term course of anorexia nervosa: Response, relapse, remission, and recovery. Clinical Psychology Review. 1998;18:447–475. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(98)00014-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter LS, Keefe FJ, Baucom DH, Hurwitz H, Moser B, Patterson E, Kim HJ. Partner-assisted emotional disclosure for patients with gastrointestinal cancer: results from a randomized controlled trial. Cancer. 2009;115(18 Suppl):4326–4338. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robin A, Siegel P, Koepke T, Moye A, Tice S. Family therapy versus individual therapy for adolescent females with anorexia nervosa. Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 1994;15:111–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robin AL, Siegel PT, Moye A. Family versus individual therapy for anorexia: impact on family conflict. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1995;17:313–322. doi: 10.1002/1098-108x(199505)17:4<313::aid-eat2260170402>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell GFM, Szmukler GI, Dare C, Eisler I. An evaluation of family therapy in anorexia and bulimia nervosa. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1987;44:1047–1056. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1987.01800240021004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santonastaso P, Saccon D, Favaro A. Burden and psychiatric symptoms on key relatives of patients with eating disorders: a preliminary study. Eating and Weight Disorders. 1997;2:44–48. doi: 10.1007/BF03339949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp C, Freeman C. The medical complications of anorexia nervosa. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1993;162:452–462. doi: 10.1192/bjp.162.4.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher TG, Braun LT, Domas A, Bellg A, Tennant J, Baucom DH, Houle TT. The Partners for Life Program: A couples approach to cardiac risk reduction. Manuscript submitted for publication. 2011 doi: 10.1111/famp.12061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder DK, Wills RM. Behavioral versus insight-oriented marital therapy: Effects on individual and interspousal functioning. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1989;57:39–46. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.57.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Striegel-Moore RH, Leslie D, Petrill SA, Garvin V, Rosenheck RA. One-year use and cost of inpatient and outpatient services among female and male patients with an eating disorder: evidence from a national database of health insurance claims. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2000;27:381–389. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(200005)27:4<381::aid-eat2>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strober M, Freeman R, Morrell W. The long-term course of severe anorexia nervosa in adolescents: survival analysis of recovery, relapse, and outcome predictors over 10- 15 years in a prospective study. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1997;22:339–360. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199712)22:4<339::aid-eat1>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan PF. Mortality in anorexia nervosa. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1995;152:1073–1074. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.7.1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tozzi F, Sullivan PF, Fear JL, McKenzie J, Bulik CM. Causes and recovery in anorexia nervosa: the patient’s perspective. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2003;33:143–154. doi: 10.1002/eat.10120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treasure J, Murphy T, Szmukler G, Todd G, Gavan K, Joyce J. The experience of caregiving for severe mental illness: a comparison between anorexia nervosa and psychosis. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2001;36:343–347. doi: 10.1007/s001270170039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treasure J, Whitaker W, Todd G, Whitney J. A description of multiple family workshops for carers of people with anorexia nervosa. European Eating Disorders Review. doi: 10.1002/erv.1075. e-pub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van den Broucke S, Vandereycken W, Vertommen H. Marital communication in eating disorder patients: a controlled observational study. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1995a;17:1–21. doi: 10.1002/1098-108x(199501)17:1<1::aid-eat2260170102>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van den Broucke S, Vandereycken W, Vertommen H. Marital intimacy in patients with an eating disorder: a controlled self-report study. British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1995b;34(Pt 1):67–78. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1995.tb01437.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitney J, Murray J, Gavan K, Todd G, Whitaker W, Treasure J. Experience of caring for someone with anorexia nervosa: qualitative study. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;187:444–449. doi: 10.1192/bjp.187.5.444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiseman CV, Sunday SR, Klapper F, Harris WA, Halmi KA. Changing patterns of hospitalization in eating disorder patients. I British Journal of. 2001;30:69–74. doi: 10.1002/eat.1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodside DB, Lackstrom JB, Shekter-Wolfson L. Marriage in eating disorders comparisons between patients and spouses and changes over the course of treatment. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2000;49:165–168. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(00)00154-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zipfel S, Lowe B, Reas DL, Deter HC, Herzog W. Long-term prognosis in anorexia nervosa: lessons from a 21-year follow- up study. Lancet. 2000;355(9205):721–722. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)05363-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]