Abstract

Background

Diabetic patients may have a higher risk of gastric cancer. However, whether they have a higher incidence of Helicobacter pylori (HP) eradication is not known. Furthermore, whether insulin use in patients with type 2 diabetes may be associated with a higher incidence of HP eradication has not been investigated.

Methods

This is a retrospective cohort study. The reimbursement databases from 1996 to 2005 of 1 million insurants of the National Health Insurance in Taiwan were retrieved. After excluding those aged <25 years, cases of gastric cancer, cases receiving HP eradication before 2005, patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus and those with unknown living region, the reimbursement data of a total of 601,441 insurants were analyzed. Diabetes status and insulin use in patients with type 2 diabetes before 2005 were the main exposures of interest and the first event of HP eradication in 2005 was the main outcome evaluated. HP eradication was defined as a combination use of proton pump inhibitor or H2 receptor blockers, plus clarithromycin or metronidazole, plus amoxicillin or tetracycline, with or without bismuth, in the same prescription for 7-14 days. The association between type 2 diabetes/insulin use and HP eradication was evaluated by logistic regression, considering the confounding effect of diabetes duration, comorbidities, medications and panendoscopic examination.

Results

In 2005, there were 10,051 incident cases receiving HP eradication. HP eradication was significantly increased with age, male sex, diabetes status, insulin use, use of calcium channel blocker, panendoscopic examination, hypertension, dyslipidemia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, stroke, nephropathy, ischemic heart disease and peripheral arterial disease. Significant differences were also seen for occupation and living region. Medications including statin, fibrate, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker and oral anti-diabetic agents were not associated with HP eradication. The adjusted odds ratios for diabetes, insulin use and use of calcium channel blocker was 1.133 (1.074, 1.195), 1.414 (1.228, 1.629) and 1.147 (1.074, 1.225), respectively.

Conclusions

Type 2 diabetes and insulin use in the diabetic patients are significantly associated with a higher incidence of HP eradication. Additionally, use of calcium channel blocker also shows a significant association with HP eradication.

Keywords: Diabetes, Helicobacter pylori, Insulin, Gastric cancer, National Health Insurance, Taiwan

Background

Our population-based cohort study showed that patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) have a significantly higher risk of gastric cancer mortality [1]. Helicobacter pylori (HP) infection is the most important etiology for gastric cancer, and its eradication can significantly reduce gastric cancer in carriers without precancerous lesions [2].

However, the link between diabetes and HP infection has been inconsistently reported. Case-control studies suggested that patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) do not have a higher prevalence of HP infection [3,4] and the prevalence may decrease with longer duration of diabetes [3]. Successful HP eradication rates in patients with T1DM and T2DM are 62% and 50%, respectively, which are much lower than the recommended 80% [5-7]. Furthermore, reinfection rate is higher in patients with T1DM [8,9], and it may deteriorate metabolic control, leading to the requirement of higher insulin dosage and development of diabetic complications [8,9].

Studies regarding HP infection rate in patients with T2DM are still scarce. A hospital-based case-control study from Pakistan enrolling 74 patients with T2DM and 74 non-diabetic controls suggested that diabetic patients have a higher infection rate (73% vs. 51.4%) [10]. Similarly, a higher infection rate is observed in 210 patients with T2DM (vs. 210 controls) in a study from the United Arab Emirates [11]. On the other hand, a Turkish study in 141 patients with T2DM and 142 controls showed no significant difference between the two groups [12].

Based on the above observations, it is reasonable to hypothesize that diabetic patients might have a higher HP infection rate or a higher clinical activity of the infection requiring eradication therapy. It is also possible that patients with T2DM and with poor glycemic control, who require insulin therapy, may represent a group of high risk patients for HP eradication. Population-based study and incidence data evaluating these hypotheses have not been reported. Therefore, by using the population-based reimbursement databases of the National Health Insurance (NHI) in Taiwan, the present study tests these hypotheses by evaluating the incidence and odds ratios of HP eradication in patients with T2DM versus non-diabetic subjects; and in insulin users versus non-users among the patients with T2DM. The effects of diabetes duration, comorbidities, medications and the frequency of panendoscopic examination (PES) were also considered in the analyses.

Methods

Study population

This is a retrospective cohort study using the reimbursement databases of the NHI of Taiwan. According to the Ministry of Interior, >98.0% of the Taiwanese population in 2005 (22,770,383: 11,562,440 men and 11,207,943 women) were covered by the NHI [13]. A random sample of 1,000,000 insurants in 2005 was created by the National Health Research Institute. The National Health Research Institute is the only institute approved, as per local regulations, for conducting sampling of a representative sample of the whole population for the year 2005 with a predetermined sample size of 1,000,000 individuals. The reimbursement databases of these individuals were retrieved and could be provided for academic research after approval. The identification information was scrambled for the protection of the privacy of the individuals.

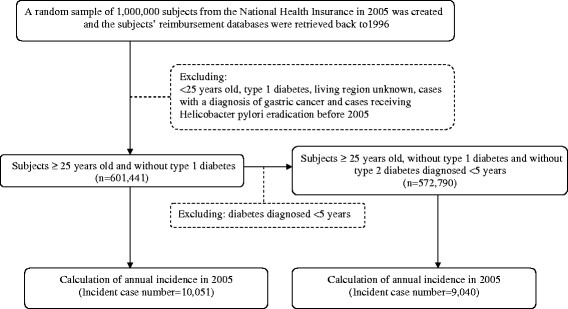

Figure 1 shows a flowchart for selecting cases for the study. After excluding subjects <25 years old, patients with T1DM (in Taiwan, patients with T1DM were issued a “Severe Morbidity Card” after certified diagnosis), living region unknown, cases with a diagnosis of gastric cancer and cases receiving HP eradication before 2005, the data of 601,441 subjects were analyzed.

Figure 1.

Flowchart showing the procedures in the calculation of the annual incidence of Helicobacter pylori eradication in 2005 in Taiwan using the National Health Insurance database.

Data retrieved from NHI databases

The reimbursement databases were available back to 1996. Identification number, sex, birth date, medications and diagnostic codes based on the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) were retrieved. Diabetes was coded 250.1-250.9 and gastric cancer 151. The comorbidities (ICD-9-CM codes) included hypertension (401-405), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (490-496, a surrogate for smoking), stroke (430-438), nephropathy (580-589), ischemic heart disease (410-414), peripheral arterial disease (250.7, 785.4, 443.81, 440-448), eye disease (250.5, 362.0, 369, 366.41, 365.44), obesity (278) and dyslipidemia (272.0-272.4).

Medications included statin, fibrate, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor and/or angiotensin receptor blocker, calcium channel blocker, sulfonylurea, metformin, insulin, acarbose, pioglitazone and rosiglitazone. The NHI insurants were classified according to occupation and this served as a surrogate for socioeconomic status. The living region served as a surrogate for geographical distribution of some environmental exposure. Occupation was categorized as I: civil servants, teachers, employees of governmental or private business, professionals and technicians; II: people without particular employers, self-employed or seamen, III: farmers or fishermen; and IV: low-income families supported by social welfare or veterans. Living region was categorized as Taipei, Northern, Central, Southern and Kao-Ping/Eastern.

The methods for identifying patients receiving HP eradication therapy in a previous study were followed [14]. The details for all therapeutic regimens are shown in the supplementary Table 1 of this earlier paper. In brief, HP eradication therapy was defined as a combination use of proton pump inhibitor or H2 receptor blockers, plus clarithromycin or metronidazole, plus amoxicillin or tetracycline, with or without bismuth, in the same prescription order for 7-14 days.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of study subjects aged 25 years or older by diabetes status

|

Variable |

Diabetes mellitus |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |

No |

Yes |

P value |

||

| n or mean | % or SD | nor mean | % or SD | ||

|

n (%) |

511519 |

85.05 |

89922 |

14.95 |

|

| Age (years) |

43.98 |

14.00 |

58.01 |

14.95 |

<0.0001 |

| Sex (men, %) |

253626 |

49.58 |

39950 |

44.43 |

<0.0001 |

| Hypertension (%) |

79292 |

15.50 |

50549 |

56.21 |

<0.0001 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (%) |

105693 |

20.66 |

36273 |

40.34 |

<0.0001 |

| Stroke (%) |

24744 |

4.84 |

18484 |

20.56 |

<0.0001 |

| Nephropathy (%) |

24780 |

4.84 |

15971 |

17.76 |

<0.0001 |

| Ischemic heart disease (%) |

40465 |

7.91 |

28523 |

31.72 |

<0.0001 |

| Peripheral arterial disease (%) |

15732 |

3.08 |

12683 |

14.10 |

<0.0001 |

| Eye disease (%) |

1170 |

0.23 |

8763 |

9.75 |

<0.0001 |

| Obesity (%) |

4180 |

0.82 |

2410 |

2.68 |

<0.0001 |

| Dyslipidemia (%) |

51126 |

9.99 |

44973 |

50.01 |

<0.0001 |

| Statin (%) |

19608 |

3.83 |

24481 |

27.22 |

<0.0001 |

| Fibrate (%) |

16084 |

3.14 |

19053 |

21.19 |

<0.0001 |

| Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor/ Angiotensin receptor blocker (%) |

6904 |

1.35 |

6638 |

7.38 |

<0.0001 |

| Calcium channel blocker (%) |

34889 |

6.82 |

18908 |

21.03 |

<0.0001 |

| Occupation (%) |

|

|

|

|

|

| I |

282985 |

55.32 |

35103 |

39.04 |

<0.0001 |

| II |

82588 |

16.15 |

17037 |

18.95 |

|

| III |

61580 |

12.04 |

19708 |

21.92 |

|

| IV |

84366 |

16.49 |

18074 |

20.10 |

|

| Living region (%) |

|

|

|

|

|

| Taipei |

193494 |

37.83 |

31534 |

35.07 |

<0.0001 |

| Northern |

74045 |

14.48 |

11182 |

12.44 |

|

| Central |

91087 |

17.81 |

15664 |

17.42 |

|

| Southern |

66785 |

13.06 |

14807 |

16.47 |

|

| Kao-Ping/Eastern |

86108 |

16.83 |

16735 |

18.61 |

|

| Panendoscopic examination in 2005 |

8211 |

1.61 |

2834 |

3.15 |

<0.0001 |

| Panendoscopic examination in 1997-2005 |

37759 |

7.38 |

11762 |

13.08 |

<0.0001 |

|

Diabetic patients only |

|

|

|

|

|

| Sulfonylurea (%) |

- |

- |

37211 |

41.38 |

|

| Metformin (%) |

- |

- |

33106 |

36.82 |

|

| Insulin (%) |

- |

- |

6010 |

6.68 |

|

| Acarbose (%) |

- |

- |

6968 |

7.75 |

|

| Pioglitazone (%) |

- |

- |

2329 |

2.59 |

|

| Rosiglitazone (%) | - | - | 6538 | 7.27 | |

Data are expressed as n (%) or mean (SD). *Occupation categories are explained in “Materials and Methods”.

Statistical analyses

Diabetes status and insulin use were considered as the exposures of interest and HP eradication as the outcome in the study. To assure the correctness of temporal order of exposure and outcome, age, diabetes status, diabetes duration, use of insulin or other medications, and comorbidities were recorded as a status or diagnosis before January 1, 2005; and HP eradication was recorded as a first event occurring in the year 2005. PES done in 2005 and from 1997 to 2005 were both analyzed. The purpose to include PES done in 2005 was to assure the temporal proximity of performing PES which might be related to the conduction of HP eradication.

The baseline characteristics between diabetic and non-diabetic subjects were compared by Student’s t test for continuous variables and by Chi square test for categorical variables.

Chi square test examined the differences of annual incidence of HP eradication among subgroups of age (25-44, 45-54, 55-64 and ≥65 years), sex, diabetes (for all subjects), insulin use (for diabetic patients only), occupation and living region, for all subjects and for the diabetic patients only separately, before and after excluding patients with diabetes diagnosed <5 years (Figure 1).

Logistic regression estimated the mutually-adjusted odds ratios for HP eradication in all subjects and in the diabetic patients only. For the diabetic patients only, the independent variables included age, sex, PES (1997-2005), the above-mentioned comorbidities, living region, occupation and all the above-mentioned medications. For all subjects, the independent variables included age, sex, diabetes, PES (1997-2005), the above-mentioned comorbidities, medications other than anti-diabetic therapies (i.e., statin, fibrate, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor and/or angiotensin receptor blocker, calcium channel blocker), living region and occupation.

Additional logistic models were created to examine whether the magnitude of the odds ratios for diabetes status (for all subjects), diabetes duration (for all subjects) and insulin use (for the diabetic patients only) might change by including different sets of covariates. Model I was adjusted for age and sex; model II for age, sex, occupation and living region; model III for age, sex, occupation, living region, PES (in 2005), hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, stroke, nephropathy, ischemic heart disease, peripheral arterial disease, eye disease, obesity and dyslipidemia; model IV for age, sex, occupation, living region, PES (in 2005), hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, stroke, nephropathy, ischemic heart disease, peripheral arterial disease, eye disease, obesity, dyslipidemia, statin, fibrate, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker and calcium channel blocker (model IV in diabetic patients only was additionally adjusted for oral anti-diabetic agents including sulfonylurea, metformin, acarbose, pioglitazone and rosiglitazone).

Analyses were conducted using SAS statistical software, version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Data were expressed as mean (standard deviation) for continuous variables or number (%) for categorical variables. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Table 1 compares the baseline characteristics between diabetic and non-diabetic subjects. The diabetic patients were older and female predominant, and had higher prevalence rates of comorbidities, medication use and PES (in 2005 or 1997-2005).

The annual incidences of HP eradication in different groups are shown in Table 2. HP eradication rates increased with increasing age, and were higher in men, diabetic patients and insulin users. Significant differences were also seen for occupation and living region.

Table 2.

Annual incidence (per 100,000) of Helicobacter pylori eradication in 2005 in Taiwan

|

Variable |

Excluding diabetes diagnosed <5 years |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |

|

No |

|

|

Yes |

|

| n | Incidence | P | n | Incidence | P | |

|

All subjects |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Age (years) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 25-44 |

3250 |

1009.44 |

<0.0001 |

3066 |

974.82 |

<0.0001 |

| 45-54 |

2370 |

1805.69 |

|

2134 |

1725.63 |

|

| 55-64 |

1687 |

2469.52 |

|

1462 |

2352.68 |

|

| ≥65 |

2744 |

3433.69 |

|

2378 |

3281.67 |

|

| Sex |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Men |

5142 |

1751.51 |

<0.0001 |

4612 |

1648.96 |

<0.0001 |

| Women |

4909 |

1594.53 |

|

4428 |

1510.76 |

|

| Diabetes |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| No |

7129 |

1393.69 |

<0.0001 |

7129 |

1393.69 |

<0.0001 |

| Yes |

2922 |

3249.48 |

|

1911 |

3118.93 |

|

| Occupation* |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| I |

4272 |

1343.02 |

<0.0001 |

3915 |

1277.81 |

<0.0001 |

| II |

1815 |

1821.83 |

|

1640 |

1744.48 |

|

| III |

2023 |

2488.68 |

|

1764 |

2332.50 |

|

| IV |

1941 |

1894.77 |

|

1721 |

1778.46 |

|

| Living region |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Taipei |

3471 |

1542.47 |

<0.0001 |

3123 |

1455.34 |

<0.0001 |

| Northern |

1220 |

1431.47 |

|

1103 |

1349.10 |

|

| Central |

1670 |

1564.39 |

|

1486 |

1461.00 |

|

| Southern |

1623 |

1989.17 |

|

1449 |

1874.95 |

|

| Kao-Ping/Eastern |

2067 |

2009.86 |

|

1879 |

1928.17 |

|

|

Diabetic patients only |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Age (years) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 25-44 |

374 |

1999.57 |

<0.0001 |

190 |

1687.09 |

<0.0001 |

| 45-54 |

568 |

2789.51 |

|

332 |

2598.83 |

|

| 55-64 |

677 |

3435.33 |

|

452 |

3339.24 |

|

| ≥65 |

1303 |

4183.12 |

|

937 |

3953.92 |

|

| Sex |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Men |

1380 |

3454.32 |

0.0020 |

850 |

3260.95 |

0.0818 |

| Women |

1542 |

3085.73 |

|

1061 |

3013.78 |

|

| Insulin use |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| No |

2619 |

3121.13 |

<0.0001 |

1678 |

2979.72 |

<0.0001 |

| Yes |

303 |

5041.60 |

|

233 |

4700.42 |

|

| Occupation* |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| I |

963 |

2743.36 |

<0.0001 |

606 |

2589.96 |

<0.0001 |

| II |

521 |

3058.05 |

|

346 |

3028.98 |

|

| III |

778 |

3947.64 |

|

519 |

3694.74 |

|

| IV |

660 |

3651.65 |

|

440 |

3547.53 |

|

| Living region |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Taipei |

962 |

3050.68 |

0.0002 |

614 |

2910.64 |

<0.0001 |

| Northern |

330 |

2951.17 |

|

213 |

2761.57 |

|

| Central |

489 |

3121.81 |

|

305 |

2870.86 |

|

| Southern |

548 |

3700.95 |

|

374 |

3562.92 |

|

| Kao-Ping/Eastern | 593 | 3543.47 | 405 | 3570.80 | ||

n = case number of Helicobacter pylori eradication.

*Occupation categories are explained in “Materials and Methods”.

Chi-square test was used for the statistical analysis.

The mutually-adjusted odds ratios for HP eradication are shown in Table 3. For all subjects, age, male sex, diabetes, PES (1997-2005), hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, stroke, nephropathy, ischemic heart disease, peripheral arterial disease, dyslipidemia, calcium channel blocker, living region (northern and central) and occupation (III and IV) were significantly associated with a higher incidence. Except for dyslipidemia and living region in northern Taiwan, the significant variables for the diabetic patients only were all the same as in the model for all subjects. Furthermore, insulin use was significantly associated with HP eradication.

Table 3.

Mutually-adjusted odds ratios for Helicobacter pylori eradication in 2005 in Taiwan

|

Study/Variable |

Interpretation |

Adjusted odds ratio (95% confidence interval) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| All subjects | Diabetic patients only | ||

| Age |

Every 1-year increment |

1.014 (1.012, 1.015) |

1.008 (1.005, 1.011) |

| Sex |

Men vs. Women |

1.220 (1.171, 1.270) |

1.155 (1.071, 1.247) |

| Diabetes |

Yes vs. No |

1.133 (1.074, 1.195) |

-- |

| Panendoscope examination (1997-2005) |

Yes vs. No |

8.940 (8.573, 9.321) |

5.592 (5.173, 6.045) |

| Hypertension |

Yes vs. No |

1.199 (1.129, 1.273) |

1.215 (1.098, 1.345) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

Yes vs. No |

1.257 (1.202, 1.314) |

1.214 (1.121, 1.313) |

| Stroke |

Yes vs. No |

1.119 (1.051, 1.191) |

1.096 (1.000, 1.201) |

| Nephropathy |

Yes vs. No |

1.268 (1.193, 1.347) |

1.314 (1.203, 1.435) |

| Ischemic heart disease |

Yes vs. No |

1.246 (1.179, 1.317) |

1.183 (1.086, 1.289) |

| Peripheral arterial disease |

Yes vs. No |

1.126 (1.048, 1.211) |

1.133 (1.025, 1.252) |

| Eye disease |

Yes vs. No |

0.937 (0.833, 1.053) |

0.898 (0.784, 1.029) |

| Obesity |

Yes vs. No |

0.971 (0.816, 1.155) |

0.815 (0.627, 1.061) |

| Dyslipidemia |

Yes vs. No |

1.174 (1.110, 1.242) |

1.034 (0.948, 1.127) |

| Statin |

Yes vs. No |

1.013 (0.946, 1.086) |

1.015 (0.923, 1.116) |

| Fibrate |

Yes vs. No |

1.015 (0.944, 1.091) |

1.007 (0.913, 1.110) |

| Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor/ Angiotensin receptor blocker |

Yes vs. No |

1.011 (0.912, 1.121) |

1.051 (0.913, 1.211) |

| Calcium channel blocker |

Yes vs. No |

1.147 (1.074, 1.225) |

1.108 (1.004, 1.224) |

| Living region |

Northern vs. Taipei |

1.103 (1.042, 1.168) |

1.082 (0.968, 1.208) |

| |

Central vs. Taipei |

1.124 (1.056, 1.195) |

1.140 (1.022, 1.271) |

| |

Southern vs. Taipei |

1.027 (0.969, 1.088) |

1.047 (0.941, 1.165) |

| |

Kao-Ping/Eastern vs. Taipei |

0.988 (0.924, 1.058) |

0.979 (0.859, 1.116) |

| Occupation |

II vs. I |

1.022 (0.961, 1.087) |

1.023 (0.910, 1.148) |

| |

III vs. I |

1.317 (1.235, 1.404) |

1.286 (1.144, 1.445) |

| |

IV vs. I |

1.308 (1.235, 1.386) |

1.205 (1.080, 1.345) |

| Sulfonylurea |

Yes vs. No |

- |

0.978 (0.875, 1.093) |

| Metformin |

Yes vs. No |

- |

0.972 (0.867, 1.091) |

| Insulin |

Yes vs. No |

- |

1.414 (1.228, 1.629) |

| Acarbose |

Yes vs. No |

- |

1.004 (0.863, 1.167) |

| Pioglitazone |

Yes vs. No |

- |

0.999 (0.787, 1.269) |

| Rosiglitazone | Yes vs. No | - | 0.939 (0.800, 1.101) |

*Occupation categories are explained in “Materials and Methods”.

The unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios for HP eradication for diabetes status (for all subjects), diabetes duration (for all subjects) and insulin use (for diabetic patients only) are shown in Table 4. Diabetes was associated with a significantly higher odds ratio of HP eradication in all models, though the odds ratio attenuated when more covariates were adjusted, especially when the comorbidities were considered (models III and IV). The odds ratios attenuated with increasing diabetes duration and with adjustment for covariates, especially when comorbidities and medications were included. The odds ratios became insignificant for diabetes duration of more than 3 years in models III and IV. Insulin use was significantly associated with a higher odds ratio though the magnitude of the odds ratios attenuated slightly after adjustment for covariates.

Table 4.

Odds ratios for Helicobacter pylori eradication for diabetes status, diabetes duration and insulin use

|

Diabetes-related variable |

Odds ratio (95% confidence interval) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |

Unadjusted |

|

Adjusted |

|

|

| Model I | Model II | Model III | Model IV | ||

|

All subjects |

|

|

|

|

|

| Non-diabetes |

1.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

| Diabetes |

2.376 (2.275, 2.482) |

1.644 (1.569, 1.723) |

1.633 (1.558, 1.711) |

1.132 (1.062, 1.208) |

1.137 (1.065, 1.213) |

|

All subjects |

|

|

|

|

|

| Non-diabetes |

1.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

| Diabetes <1 year |

3.596 (3.217, 4.020) |

2.736 (2.444, 3.061) |

2.721 (2.431, 3.045) |

1.772 (1.522, 2.062) |

1.772 (1.522, 2.062) |

| Diabetes 1-3 years |

2.273 (2.062, 2.506) |

1.695 (1.536, 1.871) |

1.681 (1.523, 1.855) |

1.293 (1.139 1.468) |

1.289 (1.135, 1.463) |

| Diabetes 3-5 years |

2.178 (1.977, 2.398) |

1.587 (1.439, 1.750) |

1.575 (1.428, 1.737) |

1.053 (0.927, 1.196) |

|

| Diabetes ≥5 years |

2.303 (2.182, 2.430) |

1.513 (1.428, 1.602) |

1.503 (1.419, 1.592) |

1.022 (0.944, 1.106) |

|

|

Diabetic patients only |

|

|

|

|

|

| Non-insulin users |

1.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

| Insulin users | 1.648 (1.459, 1.862) | 1.495 (1.322, 1.690) | 1.483 (1.311, 1.677) | 1.319 (1.127, 1.543) | 1.389 (1.178, 1.639)* |

I: Adjusted for age and sex.

II: Adjusted for age, sex, occupation and living region.

III: Adjusted for age, sex, occupation, living region, panendoscopic examination (in 2005), hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, stroke, nephropathy, ischemic heart disease, peripheral arterial disease, eye disease, obesity and dyslipidemia.

IV: Adjusted for age, sex, occupation, living region, panendoscopic examination (in 2005), hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, stroke, nephropathy, ischemic heart disease, peripheral arterial disease, eye disease, obesity, dyslipidemia, statin, fibrate, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker and calcium channel blocker.

*Model IV in diabetic patients only was additionally adjusted for oral anti-diabetic agents including sulfonylurea, metformin, acarbose, pioglitazone and rosiglitazone.

Discussion

This study provided for the first time a nation-wide population-based analysis with a large sample size on the association between T2DM and HP eradication. Diabetes was significantly associated with a higher incidence of HP eradication (Tables 2, 3, 4), independent of comorbidities, medications, PES, occupation and living region (Tables 3 and 4). The odds ratios attenuated with increasing diabetes duration, probably due to the increased occurrence of comorbidities, which might also affect the incidence of HP eradication (Table 4). Furthermore, use of calcium channel blockers (Table 3) and insulin use in the diabetic patients (Tables 2, 3, 4) were also significantly associated with HP eradication.

The higher incidence of HP eradication associated with diabetes could be explained by the following possibilities: the diabetic patients might have a higher chance of being detected for HP infection, or they might have a higher HP infection rate or a higher activity of HP infection. A higher detection rate is possible because the diabetic patients were more prone to have PES (Table 1). However, this could not explain the whole picture because the higher incidence of HP eradication associated with diabetes remained significant after adjustment for PES and other covariates (Tables 3 and 4). Currently we do not have HP infection rates in Taiwanese diabetic and non-diabetic subjects. Some studies suggested that the HP infection rates are similar between non-diabetic and diabetic subjects in patients with either T1DM [3,4] or T2DM [12]. If this is the case, the higher incidence of HP eradication associated with diabetes (Tables 234) may implicate that HP infection in the diabetic patients is more clinically active with more severe symptoms, leading to its diagnosis and the use of medications for its eradication.

Insulin use was consistently associated with a higher incidence of HP eradication, but none of the oral anti-diabetic agents was (Tables 234). Insulin use may be a proxy for uncontrollable hyperglycemia with more severe disease. Therefore this observation might be explained in the following ways. HP infected patients might have deteriorated metabolic control [8,9] and required insulin therapy; or they might have more severe diabetic conditions (e.g., diabetic gastroparesis) with gastrointestinal symptoms leading to more aggressive examination and diagnosis of HP infection.

A significantly higher rate of HP eradication was seen in subjects taking calcium channel blockers (Table 3). It is interesting that calcium channel blockers are also associated with gastroesophageal reflux disease, probably due to its relaxation effect on lower esophageal sphincter [15]. HP infection can induce pepsinogen release from chief cells (which may induce and aggravate peptic ulcer disease) via mechanisms involving calcium and calmodulin [16]. However, L-type calcium channel is not responsible for the pepsinogen release induced by HP [16]. Therefore it is unlikely that calcium channel blockers used in clinical practice would affect the peptic ulcers induced by HP. It was possible that the gastrointestinal symptoms associated with its use that led to the diagnosis of HP infection.

Recent studies suggest that HP eradication may reverse atrophic gastritis and improve intestinal metaplasia, which may contribute to the reduction of gastric cancer occurrence [17-19]. Therefore, early diagnosis of HP infection with clinical use of medications to eradicate the infection is not only important for the treatment of the clinical symptoms related to the infection, but also for the prevention of gastric cancer. One clinical implication of the present study is that patients with T2DM, especially those treated with insulin, may belong to a high risk group requiring special medical attention.

HP infection rate in a community-based study in Taiwan was 54.4%, and it showed age-dependency without sexual difference [20]. Although the present study suggested that clinical presentation of HP eradication was age-dependent (Tables 2 and 3), it also demonstrated a higher incidence of HP eradication in the male population (Tables 2 and 3). The reasons for a higher risk of HP eradication in men are still unknown. One possibility is that the activity of HP infection could be higher in men, which is correspondent to the higher risk of gastric cancer in men than in women in Taiwan [1].

Except for eye disease, obesity and dyslipidemia (in diabetic patients only) all other comorbidities were significantly associated with HP eradication (Table 3). This observation explained the attenuated odds ratios with prolonged diabetes duration (Table 4), when chronic complications might set in and interfere with the association between diabetes and HP eradication.

Some studies suggested that people living in crowded condition or with lower socioeconomic status may have a higher risk of HP infection [21-23]. In Taiwan, Taipei City is the most populated area. However, residents in relatively sparse area of Central Taiwan had significantly higher incidence of HP eradication than people living in other regions (Table 3). This suggested that living in crowded condition might not be an important predisposing factor. On the other hand, people with an occupation as farmers or fishermen (occupation III) or with low family income (occupation IV) consistently showed significantly higher odds ratios (Table 3), suggesting a possible role of socioeconomic status or its related condition of hygiene.

This study has several strengths. It is population-based with a large nationally representative sample, therefore, the study is not likely to be biased with respect to diabetes status or records of HP eradication. Because NHI is a universal and mandatory insurance with very high coverage but low co-payments, the detection rate would not tend to differ among different social classes.

Limitations included a lack of actual measurement of some recognized confounders such as personal hygiene, living condition, blood groups and genetic factors. We also did not have biochemical data including blood glucose, hemoglobin A1c and lipid profiles to evaluate whether HP infection can affect metabolic control. This study evaluated the incidence of HP eradication and not the prevalence or incidence of HP infection. However, because most people infected with HP do not develop clinical disease [21], estimation of prevalence or incidence of HP infection may not have clinical relevance as the evaluation of HP eradication does. Another concern is that there might be considerable under-diagnosis and under-treatment of HP infection. However, if the misclassification of the outcome is non-differential, an underestimation of the odds ratios is expected.

Conclusions

This study shows a significantly higher incidence of HP eradication in patients with T2DM and in insulin users among the diabetic patients. The odds ratios attenuated with increasing diabetes duration, probably due to the occurrence of other comorbidities. Additionally, lower socioeconomic status and use of calcium channel blockers consistently show a higher rate of HP eradication, but the uses of oral anti-diabetic agents do not. The underlying causes for the link between T2DM and the use of medications and HP eradication are clinically important but require further investigation.

Abbreviations

HP = Helicobacter pylori; ICD-9-CM = International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification; NHI = National Health Insurance; PES = Panendoscopic examination; T1DM = Type 1 diabetes mellitus; T2DM = Type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Competing interests

The author declares that he has no competing interests.

Author’s contributions

CHT researched data and wrote manuscript.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

Acknowledgments

The study is based in part on data from the National Health Insurance Research Database provided by the Bureau of National Health Insurance, Department of Health and managed by National Health Research Institutes (Registered number 99274). The interpretation and conclusions contained herein do not represent those of Bureau of National Health Insurance, Department of Health or National Health Research Institutes.

References

- Tseng CH. Diabetes conveys a higher risk of gastric cancer mortality despite an age-standardised decreasing trend in the general population in Taiwan. Gut. 2011;60:774–779. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.226522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong BC, Lam SK, Wong WM, Chen JS, Zheng TT, Feng RE, Lai KC, Hu WH, Yuen ST, Leung SY, Fong DY, Ho J, Ching CK, Chen JS. China Gastric Cancer Study Group. Helicobacter pylori eradication to prevent gastric cancer in a high-risk region of China: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291:187–194. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.2.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Luis DA, de la Calle H, Roy G, de Argila CM, Valdezate S, Canton R, Boixeda D. Helicobacter pylori infection and insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 1998;39:143–146. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8227(97)00127-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dore MP, Bilotta M, Malaty HM, Pacifico A, Maioli M, Graham DY, Realdi G. Diabetes mellitus and Helicobacter pylori infection. Nutrition. 2000;16:407–410. doi: 10.1016/S0899-9007(00)00267-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selinger C, Robinson A. Helicobacter pylori eradication in diabetic patients: still far off the treatment targets. South Med J. 2010;103:975–976. doi: 10.1097/SMJ.0b013e3181ee7dce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sargýn M, Uygur-Bayramicli O, Sargýn H, Orbay E, Yavuzer D, Yayla A. Type 2 diabetes mellitus affects eradication rate of Helicobacter pylori. World J Gastroenterol. 2003;9:1126–1128. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v9.i5.1126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demir M, Gokturk HS, Ozturk NA, Serin E, Yilmaz U. Efficacy of two different Helicobacter pylori eradication regimens in patients with type 2 diabetes and the effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication on dyspeptic symptoms in patients with diabetes: a randomized controlled study. Am J Med Sci. 2009;338:459–464. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e3181b5d3cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ojetti V, Migneco A, Nista EC, Gasbarrini G, Gasbarrini A, Pitocco D, Ghirlanda G. H pylori re-infection in type 1 diabetes: a 5 years follow-up. Dig Liver Dis. 2007;39:286–287. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2006.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ojetti V, Pitocco D, Bartolozzi F, Danese S, Migneco A, Lupascu A, Pola P, Ghirlanda G, Gasbarrini G, Gasbarrini A. High rate of helicobacter pylori re-infection in patients affected by type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:1485. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.8.1485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devrajani BR, Shah SZ, Soomro AA, Devrajani T. Type 2 diabetes mellitus: A risk factor for Helicobacter pylori infection: A hospital based case-control study. Int J Diabetes Dev Ctries. 2010;30:22–26. doi: 10.4103/0973-3930.60008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bener A, Micallef R, Afifi M, Derbala M, Al-Mulla HM, Usmani MA. Association between type 2 diabetes mellitus and Helicobacter pylori infection. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2007;18:225–229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demir M, Gokturk HS, Ozturk NA, Kulaksizoglu M, Serin E, Yilmaz U. Helicobacter pylori prevalence in diabetes mellitus patients with dyspeptic symptoms and its relationship to glycemic control and late complications. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53:2646–2649. doi: 10.1007/s10620-007-0185-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health, Taiwan. http://www.doh.gov.tw/CHT2006/DM/DM2_2.aspx?now_fod_list_no=10383&class_no=440&level_no=4 (accessed March 21, 2012)

- Wu CY, Kuo KN, Wu MS, Chen YJ, Wang CB, Lin JT. Early Helicobacter pylori eradication decreases risk of gastric cancer in patients with peptic ulcer disease. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:1641–1648. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.07.060. e1-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedenberg FK, Hanlon A, Vanar V, Nehemia D, Mekapati J, Nelson DB, Richter JE. Trends in gastroesophageal reflux disease as measured by the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:1911–1917. doi: 10.1007/s10620-009-1004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beil W, Wagner S, Piller M, Heim HK, Sewing KF. Stimulation of pepsinogen release from chief cells by Helicobacter pylori: evidence for a role of calcium and calmodulin. Microb Pathog. 1998;25:181–187. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1998.0225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang JM, Kim N, Shin CM, Lee HS, Lee DH, Jung HC, Song IS. Predictive factors for improvement of atrophic gastritis and intestinal metaplasia after helicobacter pylori eradication: a three-year follow-up study in Korea. Helicobacter. 2012;17:86–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2011.00918.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kodama M, Murakami K, Okimoto T, Abe T, Nakagawa Y, Mizukami K, Uchida M, Inoue K, Fujioka T. Helicobacter pylori eradication improves gastric atrophy and intestinal metaplasia in long-term observation. Digestion. 2012;85:126–130. doi: 10.1159/000334684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kodama M, Murakami K, Okimoto T, Sato R, Uchida M, Abe T, Shiota S, Nakagawa Y, Mizukami K, Fujioka T. Ten-year prospective follow-up of histological changes at five points on the gastric mucosa as recommended by the updated Sydney system after Helicobacter pylori eradication. J Gastroenterol. 2012;47:394–403. doi: 10.1007/s00535-011-0504-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin JT, Wang JT, Wang TH, Wu MS, Lee TK, Chen CJ. Helicobacter pylori infection in a randomly selected population, healthy volunteers, and patients with gastric ulcer and gastric adenocarcinoma. A seroprevalence study in Taiwan. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1993;28:1067–1072. doi: 10.3109/00365529309098311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gale EA. A missing link in the hygiene hypothesis? Diabetologia. 2002;45:588–594. doi: 10.1007/s00125-002-0801-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguemon BD, Struelens MJ, Massougbodji A, Ouendo EM. Prevalence and risk-factors for Helicobacter pylori infection in urban and rural Beninese populations. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2005;11:611–617. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2005.01189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoang TT, Bengtsson C, Phung DC, Sörberg M, Granström M. Seroprevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in urban and rural Vietnam. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2005;12:81–85. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.12.1.81-85.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]