Abstract

Background

Airway mucus hypersecretion is a key pathophysiological feature in number of lung diseases. Cigarette smoke/nicotine and allergens are strong stimulators of airway mucus; however, the mechanism of mucus modulation is unclear.

Objectives

Characterize the pathway by which cigarette smoke/nicotine regulates airway mucus and identify agents that decrease airway mucus.

Methods

IL-13 and gamma-aminobutyric acid receptors (GABAARs) are implicated in airway mucus. We examined the role of IL-13 and GABAARs in nicotine-induced mucus formation in normal human bronchial epithelial (NHBE) and A549 cells, and secondhand cigarette smoke and/or ovalbumin-induced mucus formation in vivo.

Results

Nicotine promotes mucus formation in NHBE cells; however, the nicotine-induced mucus formation is independent of IL-13 but sensitive to the GABAAR antagonist picrotoxin (PIC). Airway epithelial cells express α7/α9/α10 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) and specific inhibition or knockdown of α7- but not α9/α10-nAChRs abrogates mucus formation in response to nicotine and IL-13. Moreover, addition of acetylcholine or inhibition of its degradation increases mucus in NHBE cells. Nicotinic but not muscarinic receptor antagonists block allergen or nicotine/cigarette smoke-induced airway mucus formation in NHBE cells and/or in mouse airways.

Conclusions

Nicotine-induced airway mucus formation is independent of IL-13 and α7-nAChRs are critical in airway mucous cell metaplasia/hyperplasia and mucus production in response to various pro-mucoid agents, including IL-13. In the absence of nicotine, acetylcholine may be the biological ligand for α7-nAChRs to trigger airway mucus formation. α7-nAChRs are downstream of IL-13 but upstream of GABAARα2 in the MUC5AC pathway. Acetylcholine and α-7-nAChRs may serve as therapeutic targets to control airway mucus.

Keywords: cigarette smoke, nicotine, nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, gamma-aminobutyric acid receptors, acetylcholine, airway mucus

Introduction

Normal mammalian airway epithelium produces and is coated by mucins such as MUC5B and MUC5AC and, following stimulation by an allergen/infection, MUC5AC is the predominant mucin produced in human airways. These mucins assist in clearing inhaled particulate matter from the airways1. However, excessive mucous cell metaplasia and mucus hypersecretion contribute to the pathology of many respiratory diseases such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), asthma, and cystic fibrosis2. In addition, excessive mucus production prolongs lung infections and decreases lung function3. Cigarette smoke is a strong inducer of airway mucus production and a major risk factor for asthma, bronchitis, and COPD4, 5. Moreover, recent studies suggest that nicotine promotes airway mucus formation6, 7; however, the mechanism by which cigarette smoke/nicotine promotes mucus formation is not well-established. Studies have demonstrated that Th2-cytokines, particularly IL-13, are key mediators of mucous cell metaplasia/hyperplasia and mucus production8–10; however, in a rat allergic asthma model, chronic nicotine treatment strongly downregulated IL-4 and IL-13 production, but increased mucous cell metaplasia and mucus production in the lung11. Thus in this model of allergic asthma, nicotine might stimulate mucus formation independent or semi-independent of IL-13.

A number of non-neuronal cells, including T cells, macrophages, and lung epithelial cells, express nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) and may synthesize acetylcholine12, 13. Mucus-producing lung epithelial cells from rats, mice, and humans also express several different GABAA receptor (GABAAR) subunits14, which have been implicated in airway mucus formation14. Nicotine is a major constituent of cigarette smoke and in the central nervous system nicotine activates GABAAR in some neurons. Moreover, the α7/α9/α10-nAChR antagonist methyllycaconitine (MLA) moderates mucus formation in the monkey lungs6. We hypothesized that in airway epithelial cells nicotine activated GABAARs, through nAChRs, thereby promoting mucus formation. In this communication, we show that while normal human bronchial epithelial (NHBE) cells express α7, α9, and α10-nAChR subunits, α7-nAChRs play a critical role in mucous cell metaplasia and mucus formation in NHBE cells. Moreover, (a) nicotine promotes mucus formation independent of IL-13, (b) the normal biological ligand for the nAChRs in the bronchial epithelial cells for mucus formation may be acetylcholine, and (c) antagonists of nAChRs but not muscarinic receptors suppress mucus formation in vivo and in vitro.

METHODS SUMMARY

NHBE and A549 cells were cultured using standard procedures15. DO11.10 OVA-TCR transgenic on a BALB/c background were exposed to air, secondhand smoke (SS) or Nicotine (1.5 mg total particulate material/m3), heat-aggregated OVA aerosol (5 mg/m3), or OVA plus SS or nicotine for 2 weeks (6 h/day, 5 days/week). In some experiments, normal (wild-type) BALB/c mice were sensitized to Aspergillus fumigatus extract as described previously16. Where indicated mice were subcutaneously implanted with mecamylamine (MM) containing mini-osmotic pumps (2 mg/kg body weight/day) 3 weeks prior to exposure17. In another group of BALB/c mice, animals were first exposed subcutaneously to saline- (control) or MM-containing Alzet pumps for 2 wk and then sensitized with the allergen Aspergillus fumigatus extracts as in the Methods section of this article’s Online Repository. To determine the effects of nicotine, IL-13, or acetylcholine on NHBE or A549 cells, cells were treated with nicotine base (100 nM), recombinant human IL-13 (10–50 ng/ml), or indicated concentrations of neostigmine bromide (NB) respectively, and the cultures were harvested approximately 48 h later. GABAAR, nAChR, or muscarinic receptor inhibitors were added at the indicated concentrations 2 h prior to the addition of IL-13, nicotine, or NB. NHBE cells (5-μm-thick sections) were stained using alcian blue-periodic acid-Schiff’s (AB-PAS) staining for mucus18, 19, MUC5AC, or GABAARα2 using appropriate reagents, and the cell number and mucus volume were determined by microscopy11, 20. Mouse lung sections were stained for Muc5ac- and GABAARα2 using Immunohistochemistry (IHC). Total RNA was isolated from lung tissues, NHBE cells, and A549 cells using TRI-Reagent. GABAARα2-specific mRNA was assayed by using SuperScript™ III One-Step RT-PCR with Platinum® Taq. RT-PCR primers for GABAARα2 were: forward 5′-AGGCTTCCGTTATGATACAG, reverse 5′-AGGACTGACCCCTAATACAG and GAPDH: forward 5′-CCCATCACCATCTTCCAGGAG and reverse 5′-TTCACCACCTTCTTCTTGATGTCAT. qPCR was performed using a TaqMan One-Step RT-PCR kit containing AmpliTaq Gold® DNA polymerase with ABI primers and probes. Fold differences were determined by the 2(−ΔΔCT) method21. nAChR subtypes were knocked down by specific siRNAs; changes in specific mRNAs were determined 48 h after siRNA treatment. Protein levels of GABAARα2 were determined by Western blot analysis17. GraphPad Prism Software 5.03 was used to determine statistical significance by two-way ANOVA. Detailed methods are given in the Methods section of this article’s Online Repository.

RESULTS

Nicotinic receptors are critical in mucus formation

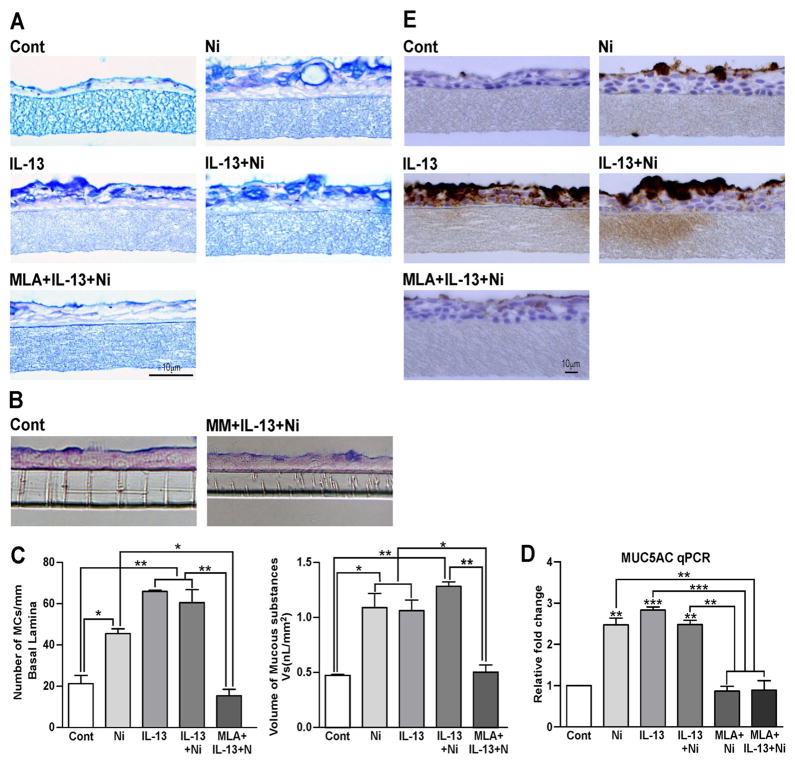

We examined the effects of nicotine (100 nM) on mucus formation in NHBE cells grown at Air Liquid Interface (ALI). This is a realistic concentration of nicotine and is severalfold lower than the EC50 concentrations (10–100 μM) of nicotine/nicotine agonists required to activate the ligand-gated cationic channel in neurons22. As seen by AB-PAS mucus staining (Fig. 1A), control (Cont) NHBE cells have a low baseline level of mucus; however, when the cells were treated with nicotine, IL-13, or IL-13 + nicotine for 48 h (predetermined optimal time), the mucus content in these cells increased strongly. Furthermore, the α7/α9/α10-nAChR-specific antagonist MLA (Fig. 1A) as well as the non-selective nAChR antagonist MM (Fig. 1B) suppressed the nicotine + IL-13-induced mucus formation in NHBE cells. MLA also blocked the increase in mucus formation in NHBE cells in response to either nicotine or IL-13 (see Fig E1). To determine whether nicotine and/or IL-13 affected mucous cell hyperplasia and metaplasia, we measured the number of mucous cells/mm basal lamina and the volume of mucus-containing cells (mucus volume/mm3 basement membrane), respectively. Nicotine and IL-13 significantly increased both mucous cell numbers (Fig. 1C, left panel) and volume (Fig. 1C, right panel), and these effects were blocked by MLA. These results suggest that both nicotine and IL-13 affect mucous cell physiology and require the activation of nAChRs (α7 and/or α9/α10). Although in some experiments a combined treatment with nicotine and IL-13 appeared to increase cell volume over the individual treatment with IL-13 or nicotine, these differences varied from experiment to experiment and were not statistically significant (data not shown). Thus nicotine and IL-13 may affect the same downstream pathway(s) for mucous cell hyperplasia/metaplasia and mucus production.

Figure 1. Nicotine and IL-13 promote mucus formation in NHBE cells through nicotinic and GABAA receptors.

In NHBE cells IL-13/nicotine (Ni)-induced mucus is suppressed by: 1 μM MLA (A) and 1 μM MM (B). MLA blocks mucous containing cells (C, left panel), mucus cell volume (C, right panel), MUC5AC mRNA (D), and MUC5AC-positive cells (E). Experiments were repeated at least five times and bars represent ±SEM.

Nicotine and IL-13 increase MUC5AC

Mucin glycoproteins are the major constituents of airway mucus. MUC5AC is the dominant mucin gene expressed in airway goblet cells23, and IL-13 is known to increase MUC5AC expression in these cells24. To ascertain whether nicotine and/or IL-13 also induced the expression of MUC5AC, NHBE cells were treated with nicotine and/or IL-13, and MUC5AC expression was examined by qPCR and IHC staining using the MUC5AC-specific antibody. Nicotine as well as IL-13 significantly increased the mRNA expression of MUC5AC; however, combined treatment with nicotine and IL-13 did not cause significantly higher MUC5AC expression than nicotine or IL-13 alone, and pretreatment with MLA blocked the increase in MUC5AC by nicotine + IL-13 (Fig. 1D). Similar results were observed by scoring for MUC5AC protein by IHC staining (Fig. 1E).

Nicotine-induced MUC5AC is independent of IL-13

IL-13 is the critical cytokine in mucus formation and MUC5AC expression8–10, 25. Although unlikely, it was possible that nicotine promoted MUC5AC/mucus formation by inducing IL-13 in NHBE cells. To ascertain this possibility, we determined IL-13 mRNA by qPCR in NHBE cells before and after nicotine treatment. Unlike human Jurkat cells (positive control), qPCR analysis of NHBE cells (up to 40 cycles) did not show any detectable expression of IL-13 mRNA in the presence or absence of nicotine (Fig. E2). Thus, while both nicotine and IL-13 induce mucus formation and MUC5AC expression in NHBE cells, the nicotine-induced MUC5AC expression and mucus formation do not necessarily require IL-13.

α7-nAChRs are required for mucus formation

Neuronal nAChRs are pentameric structures and, in mammals, nAChRs are derived from eight α subunit (α2–α7, α9, and α10) and three β subunit (β2–β4) genes; however, α7 and α9 form functional homomeric receptors26. Moreover, α10 subunits are functional only in the presence of α9 subunit27; α7 and α10 co-localize in rat sympathetic neurons28. Many non-neuronal cells, including T cells29, mast cells30, and macrophages express nAChRs; mast cells express full-length α7, α9, and α10 nAChRs that respond interdependently to low concentrations of nicotine30. To ascertain whether a specific nAChR subtype mediated the effects of nicotine on mucus formation in NHBE cells, we determined the expression of nAChR subunits (α3, α4, α5, α7, α9, α10, and β4) in these cells. Examining the expression of α3, α4, and α7 nAChR subunits was warranted because they are expressed in the lung tracheal tissue31, and genome-wide association studies show single nucleotide polymorphisms in the gene cluster encoding α3/α5/β4 nAChR subunits in lung cancer32. Our qPCR analysis suggested that α3, α4, α5, and β4 were essentially undetectable in NHBE cells (not shown); however, the cells expressed α7-, α9-, and α10-nAChR subunits (Fig. E3). After normalizing with GAPDH, the mRNA expression of α7 was much higher than α9 and α10 (i.e., α7 was detectable around 27 while α9/α10 around 35 cycle of qPCR analysis). Thus, NHBE cells express much higher levels of α7- than α9/α10- mRNA.

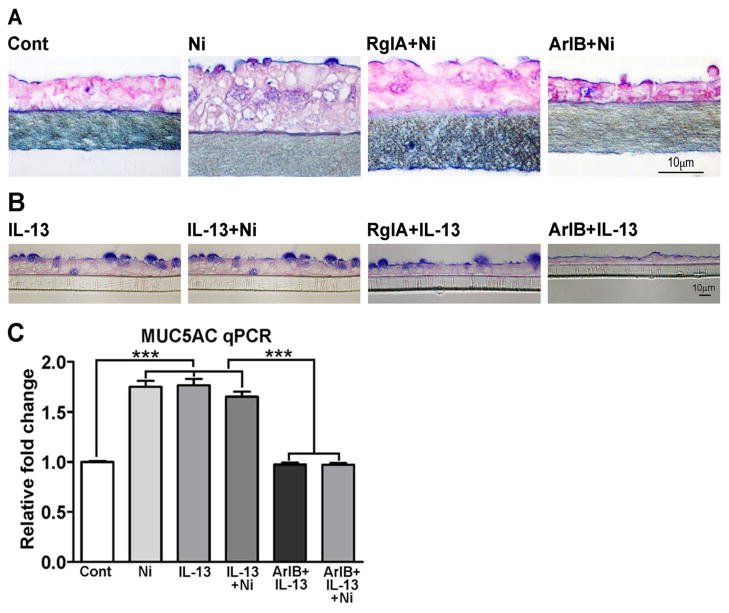

NHBE cells are generally refractory to various transfection/transduction approaches and we were unable to knock down the expression of α7-, α9-, or α10- nAChR subunits in these cells by siRNA (not shown). Therefore, to evaluate the role of α7- and/or α9/α10-nAChR subunits in mucus production, we used receptor subtype-specific conotoxin peptides to inhibit α7- and α9/α10-nAChRs in NHBE cells. At lower concentrations, the conotoxin peptides ArIB[V11L, V16D] and RgIA preferentially inhibit α7- and α9/α10-nAChRs, respectively33, 34. Using these peptides at concentrations that showed minimum cross inhibition, only ArIB[V11L, V16D] significantly reduced both nicotine- (Fig. 2A) and IL-13-induced (Fig. 2B) mucus production. Moreover, ArIB[V11L, V16D] (Fig. 2C), but not RgIA (not shown) also suppressed nicotine- and/or IL-13-induced expression of MUC5AC mRNA by qPCR. Thus, α7-nAChRs are critical in the induction of airway mucus by nicotine and IL-13.

Figure 2. α7-nAChR-specific conotoxin peptides suppress nicotine/IL-13-induced mucus in NHBE cells.

Effects of RgIA (500 nM) and ArIB[V11L, V16D] (500 nM) on Ni-induced (A) and IL-13-induced (B) mucous cell responses, and on Ni/IL-13-induced MUC5AC mRNA by qPCR (C). Each experiment was repeated at least three times, and bars on MUC5AC are mean ± SEM from three inserts.

GABAARs are downstream of α7-nAChRs

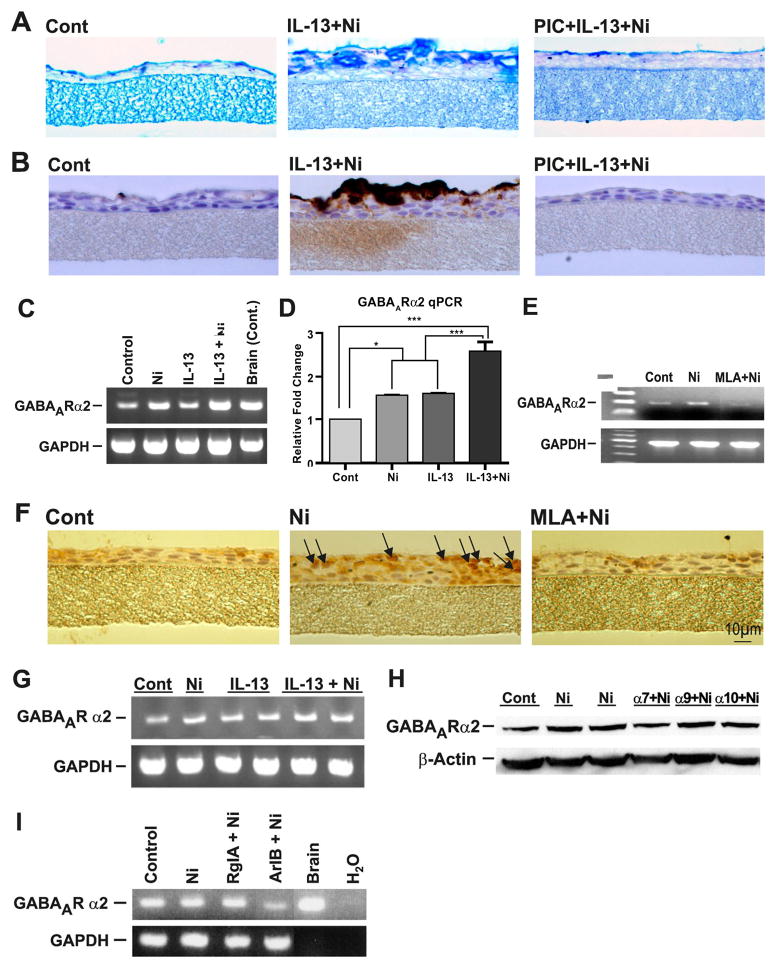

IL-13 has been shown to induce GABAARs in the human bronchial epithelial cell line A54914. Although A549 cells do not produce mucus, they contain mRNAs for α7-, α9-, and α10- (Fig. E4) as well as α3-, α4-, and β2-nAChRs (not shown). Inhibiting GABAARs with picrotoxin (PIC) also blocked mucus production in NHBE cells14. We used three approaches to determine whether the effects of nicotine on mucus formation involved GABAARs. First, we showed that the non-selective GABAAR antagonist PIC inhibited the IL-13 + nicotine-induced mucus (AB-PAS staining, Fig. 3A) and MUC5AC proteins (IHC staining, Fig. 3B) in NHBE cells or by IL-13 and nicotine individually (see Fig E1). Similarly, PIC also blocked the IL-13 + nicotine-induced mucous cell hyperplasia (Fig. E5A), metaplasia (Fig. E5B), and MUC5AC mRNA expression (Fig. E5C) in NHBE cells. Second, in NHBE cells, nicotine and/or IL-13 induced the expression of GABAARα2 as detected by RT-PCR (Fig. 3C) and qPCR (Fig. 3D); the nicotine-induced expression of GABAARα2 mRNA seen by RT-PCR was blocked by the α7,α9,α10-nAChR-specific antagonist MLA (Fig. 3E). Moreover, as assayed by IHC, MLA also blocked the nicotine-induced expression of GABAARα2 in NHBE cells (Fig. 3F). Third, A549 and NHBE cells express a number of GABAAR subtypes. RT-PCR analysis suggested that both nicotine and IL-13 upregulated the expression of GABAARα2 in A549 cells (Fig. 3G). Indeed, among several GABAAR subtypes (GABAARα2, GABAARβ2, GABAARγ, and GABAARπ) only the expression of GABAARα2 was consistently upregulated by IL-13 and nicotine in these cells (not shown). Moreover, MLA suppressed the GABAARα2 expression in A549 cells (Fig. E6). Thus, α7- and/or α9/α10-nAChRs are involved in the increased expression of GABAARα2 by nicotine in A549 cells. To identify the type of nAChR subtype among α7, α9, and α10 that regulates GABAARα2 expression and mucus formation, we used siRNA approach to individually knockdown α7-, α9-, and α10-nAChRs in A549 cells. Specific siRNA treatment selectively decreased the mRNA expression of α7-, α9-, and α10-nAChRs by approximately 65%, 80%, and 70%, respectively (Fig. E7). As seen by Western blot (Fig. 3H), the knockdown of α7, but not α9 and α10 significantly decreased nicotine-induced expression of GABAARα2 in A549 cells. In these cells, the nicotine-induced expression of GABAARα2 mRNA was also blocked by the α7-specific ArIB[V11L, V16D] but not α9/α10-specific RgIA conotoxin peptide (Fig. 3I). Because MLA blocked both nicotine- and IL-13-induced expression of GABAARα2, activation of nAChRs must precede the activation of GABAARα2 during mucus formation.

Figure 3. GABAARs and α7-nAChRs are critical in nicotine/IL-13-induced mucus formation.

In NHBE cells, effects of 50 μM picrotoxin (PIC) on mucus- (A) and MUC5AC-positive cells (B); Ni/IL-13-induced GABAARα2 expression is detected by RT-PCR (C), qPCR (D), and IHC (E), and blocked by 1 μM MLA (F). In A-549, Ni/IL-13-induced GABAARα2 (G) is blocked by Si-RNA knockdown of α7-nAChRs (H) and α7-nAChR-specific conotoxin peptide ArIB[V11L-V16D] (I).

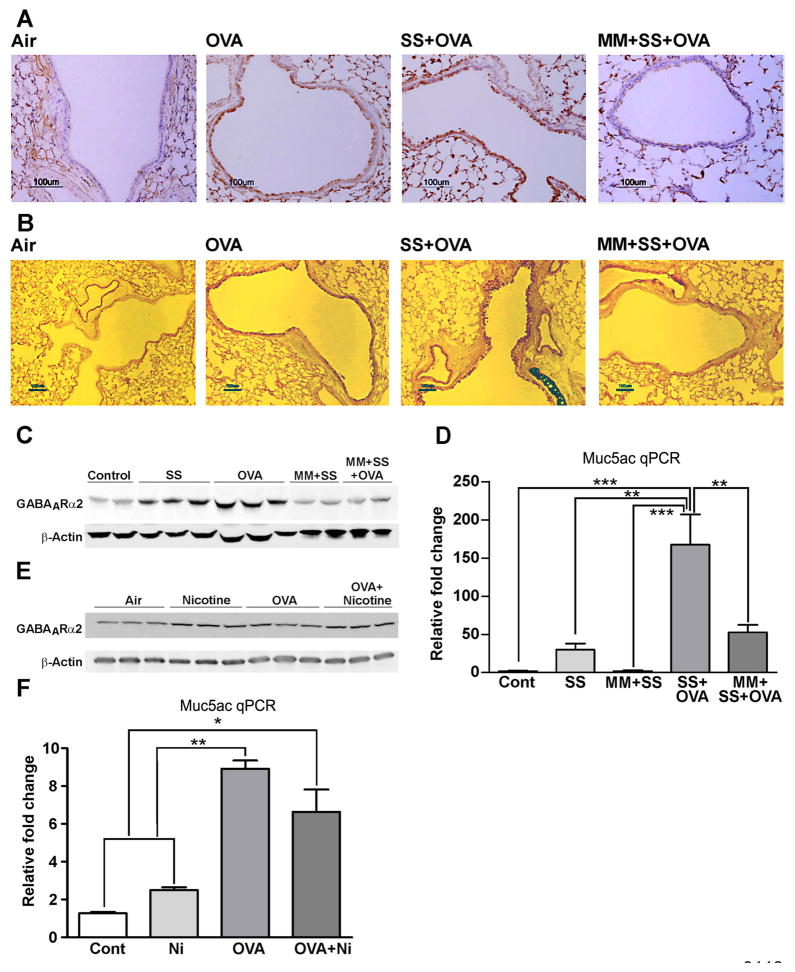

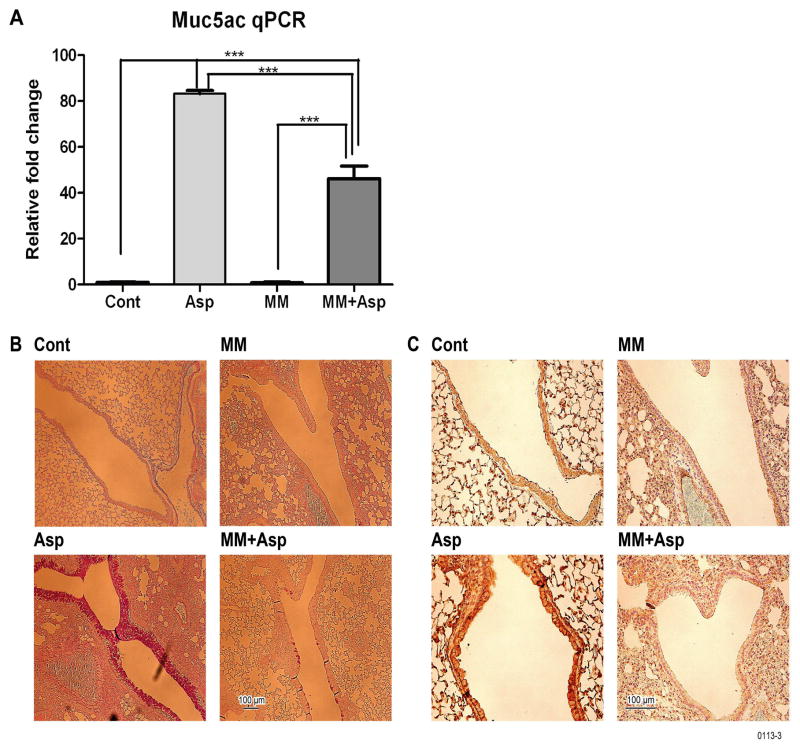

Mecamylamine blocks GABAARα2 and mucus production in mice

Cigarette smoke promotes goblet cell hyperplasia and mucus formation35. Similarly, sensitization with allergens such as OVA, ragweed, and Aspergillus extracts promotes mucus formation in airways11, 16. As seen by immunostaining, a 2-week inhalation exposure of OVA-TCR transgenic mice on the BALB/c background to OVA and/or SS strongly upregulated GABAARα2 expression (Fig. 4A) and mucus formation (Fig. 4B) in the airways. However, when the animals were pretreated with the nAChR antagonist MM prior to exposure to SS + OVA, the amplifying effects of SS + OVA on GABAARα2 expression (Fig. 4A) and airway mucus formation (Fig. 4B) were lost. Moreover, Western blot analysis of the lung extracts also indicated that MM blocked the OVA- and SS-induced expression of GABAARα2 (Fig. 4C). MM by itself had no detectable effect on normal bronchial epithelium, such as gross histopathology or nuclear condensation (not shown). Similarly, qPCR analysis indicated that MM also blocked the SS- and/or OVA-induced Muc5ac mRNA expression in the lung (Fig. 4D). In a separate experiment, lungs from BALB/c mice, exposed to air (control) or nicotine inhalation (1.5 mg/m3, 6 h/day) for 2 weeks, exhibited increased expression of GABAARα2 protein by Western blot analysis (Fig. 4E) and Muc5ac expression by qPCR (Fig. 4F). Although OVA T cell receptor transgenic mouse model has been used extensively for delineating the mechanism of allergic asthma, a weakness of this model is that more than 90% of the peripheral T cells in these mice are directed to OVA and does not necessarily require sensitization with an allergen36. Therefore, it is possible that the results may not be applicable to normal antigenic/allergic responses. To address this possibility, we used Aspergillus fumigatus extracts containing the allergen in allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis37 as the sensitizing allergen in normal BALB/c mice16. Results presented in Fig. 5 suggest that, as in the OVA transgenic system, MM suppressed the mucus formation in response to Aspergillus in normal BALB/c mice, including the increase in expression of Muc5ac (Fig. 5A), airway mucus formation by AB-PAS (Fig. 5B), and GABAARα2 IHC staining (Fig. 5C). In addition, MM inhibited the inflammatory response and Aspergillus-induced rise in eosinophils and lymphocytes by BAL cell differential count (Fig. E8A), the expression of the proinflammatory cytokines IL-13 (Fig. E8B) and IFN-γ (Fig. E8C) in the lung. Together these results suggest that nicotine promotes GABAARα2 and mucus expression similar to that of cigarette smoke, and nAChRs play a critical role in both allergen- and cigarette smoke/nicotine-induced airway mucus formation in vivo.

Figure 4. MM blocks OVA/SS/Ni-induced airway mucus, Muc5ac, and GABAARα2 expression in OVA-transgenic mice.

Mice received indicated treatments and lungs were tested for: GABAARα2 by IHC (A), mucus by AB-PAS (B), GABAARα2 Western blots of lung extracts (C), lung Muc5ac qPCR (D), GABAARα2 Western blots of lung extracts (E), and lung Muc5ac qPCR (F). The results represent two independent experiments (3–6 mice/group).

Figure 5. Aspergillus induces mecamylamine-sensitive GABAARα2 expression and mucus formation in the lung.

BALB/c mice were sensitized with Aspergillus fumigatus extracts, and where indicated received MM. Lungs were tested for: Muc5ac by qPCR (A), mucus by AB-PAS staining (B), and GABAARα2 by IHC (C). The results represent two independent experiments with 3–6 mice/group.

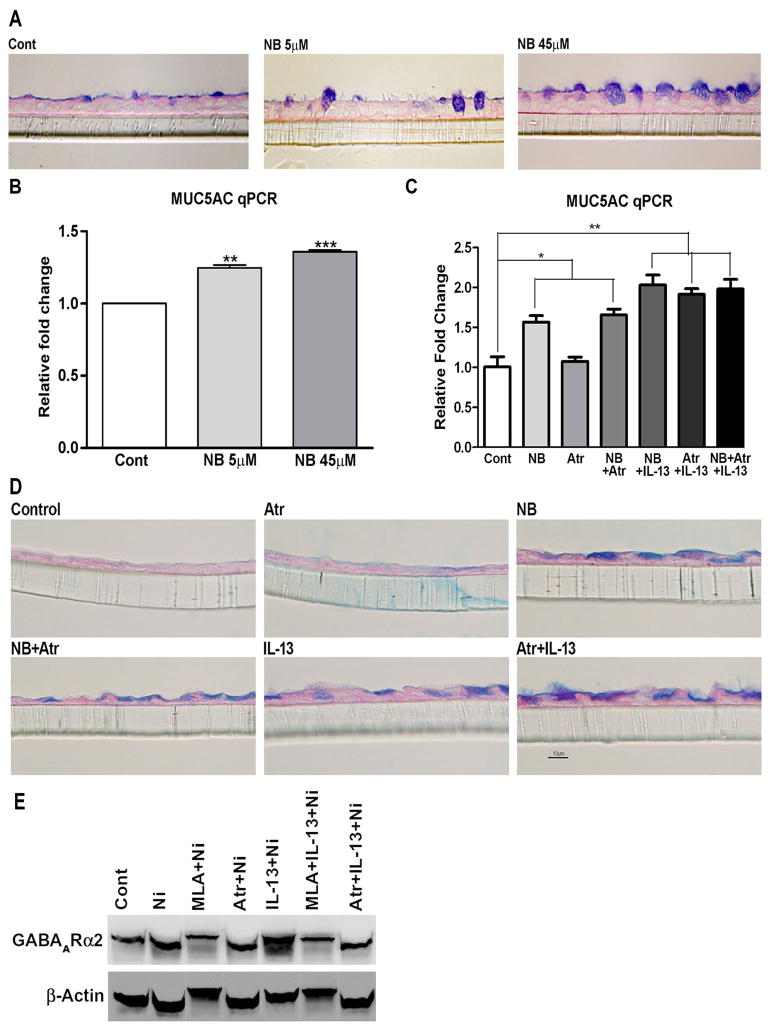

Role of acetylcholine in mucus formation in NHBE cells

If the activation of nAChRs on airway epithelial cells were to play a decisive role in mucus formation even in the absence of nicotine/cigarette smoke (e.g., nonsmokers), it is important to understand how mucus-promoting molecules such as allergens would activate nAChRs in vivo. Nicotine is not normally found in mammals; rather nicotinic cholinergic transmission is mediated by the neurotransmitter acetylcholine38. There is increasing evidence that airway epithelial cells have the enzymes to synthesize, degrade, and transport acetylcholine12, 39. qPCR analysis indicated that NHBE cells express primarily M3 and lower levels of M1 and M2 muscarinic receptors (Fig. E9A). Acetylcholine is a highly labile molecule and difficult to assay. Therefore, to ascertain that acetylcholine promotes mucus formation in airway epithelial cells, we determined: (a) whether inhibiting the degradation of acetylcholine by the acetylcholinesterase inhibitor neostigmine bromide (NB) promoted mucus formation in NHBE cells. NHBE cells were treated with indicated concentrations of NB in the absence of IL-13 or nicotine. As little as 5 μM NB (Fig. 6A) significantly upregulated the mucus formation in NHBE cells. NB also increased MUC5AC mRNA to less impressive but highly statistically significant level (Fig. 6B). (b) Acetylcholine (100 μM) was added to NHBE cells and 48 h later the cells were analyzed for MUC5AC and GABAARα2 mRNA expression by qPCR. Compared to control cells, addition of acetylcholine significantly increased the expression of both MUC5AC and GABAARα2 by approximately 2 fold (Fig. E9B and E9C). These results suggest that acetylcholine is a trigger for mucus formation in airway epithelial cells. However, it should be noted that we were unable to detect acetylcholine in NHBE cells in the presence of NB and IL-13. It is likely that the cellular level of acetylcholine in these cells is lower than the sensitivity of our HPLC assay.

Figure 6. Neostigmine bromide (NB) promotes mucus and formation in NHBE cells.

NHBE cells were treated with indicated concentrations of NB or 1 μM atropine (Atr) and scored for: NB-induced mucus (A) and MUC5AC (B). Atropine effects on NB/IL-13-induced MUC5AC (C), mucus (D) and GABAARα2 protein expression (E). The experiment in A/B/E was repeated twice. Bars represent mean ± SEM from 3 separate inserts.

Acetylcholine is the biological ligand for both nicotinic and muscarinic receptors. To ascertain that acetylcholine mediates its pro-mucoid effects through nAChRs, NHBE cells were treated with the non-selective muscarinic receptor antagonist atropine prior to NB or IL-13. Fig. 6C shows that atropine had no significant effect on the MUC5AC mRNA expression induced by NB, IL-13, or NB + IL-13. Similarly, atropine did not affect mucus formation (AB-PAS staining) in NHBE cells in response to NB or IL-13 (Fig. 6D). Moreover, unlike MLA, the increased level of GABAARα2 in NHBE cells in response to nicotine or IL-13 + nicotine was not affected by atropine treatment (Fig. 6E). These results suggest that, in the absence of nicotine or nicotine-containing substances, acetylcholine may be the critical molecule in the activation of nAChRs for mucus production in NHBE cells.

DISCUSSION

Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors are seen in tissues from both vertebrates and invertebrates such as nematodes and insects40. In the central nervous system nAChRs are ligand-gated ion channels that mediate fast synaptic cholinergic transmission and these properties are strongly conserved across species. nAChRs are present in neuronal32 and many non-neuronal cell types13, 29, 30. At least in some non-neuronal cell type nAChRs are not ligand-gated ion channels but signal through second messengers29. So far, the function nAChRs in non-neuronal cells is described primarily as regulatory41; however, the near ubiquitous presence of nAChRs in various cell types and their evolutionary conservation suggest that these receptors may have some critical functions outside the central nervous system42. Results presented herein indicate that nAChRs are essential for airway mucus production as well as mucous cell hyperplasia and metaplasia in response to nicotine and allergen in vivo and/or in vitro, and it is likely that nAChRs are critical in other cellular functions.

Nicotine is immunosuppressive and anti-inflammatory41 and our previous in vivo experiments indicated that chronic low-dose nicotine exposure significantly inhibited some parameters of allergic asthma, including a dramatic reduction in Th2 cytokines/chemokines such as IL-13, IL-4, IL-5, eotaxin, and atopy, yet the nicotine treated rats exhibited increased mucous cell metaplasia and mucus formation in the airways11. Possible explanations for these paradoxical results are that nicotine either decreased the amount of IL-13 required or substituted for IL-13 in mucus production. Our results clearly indicate that nicotine acts independent of IL-13 in promoting mucus formation and mucous cell metaplasia/hyperplasia. The ability of nAChR inhibitors to block nicotine- and IL-13-induced mucus production suggest that both IL-13 and nicotine activate nAChRs to trigger mucus formation, and IL-13 effects are upstream of nAChRs.

Previous studies have shown that IL-13 affects mucus by increasing GABAAR expression in NHBE cells14. We showed that GABAAR activation is downstream of nAChR activation in mucus formation and MUC5AC expression, and of the known GABAAR subtypes expressed in NHBEC, GABAARα2 was the only one that was significantly upregulated by IL-13 and nicotine in NHBE cells. GABAARα2 was also the only GABAAR subtype whose expression was increased by OVA and/or secondhand cigarette smoke in OVA-TCR transgenic BALB/c mice. The interaction between nAChRs and GABAARs has been shown in the central nervous system43 and, in C. elegans, cholinergic motor neurons activate GABAergic neurons44. Moreover, rhesus monkeys exposed prenatally to nicotine show increased GABA signaling in the lungs6; however, the significance of this observation is not clear because prenatal nicotine exposure also affects development of several organs including the lung45. Thus, while the mechanism by which nicotine promotes GABAergic response has not been fully delineated, it is clear that GABAARα2 are critical in nicotine and IL-13 mediated mucus formation.

To ascertain the role of nAChRs in the regulation of airway mucus in vivo, we used two models of allergic asthma to trigger mucus formation. OVA TCR transgenic BALB/c mice (a frequently used model for the lung allergic responses) were exposed to OVA and/or SS. These treatments promoted airway inflammation (leukocytic infiltration in the lung), airway mucus formation, and increased expression of Muc5ac and GABAARα2 in the lung. However, when the animals were treated with the non-selective nAChR antagonist MM, the inflammatory and mucoid responses to OVA and/or SS were significantly reduced, suggesting that nAChRs are intimately involved in the regulation of allergen-induced inflammation and mucus formation. The major question about the suitability of using OVA TCR transgenic animals to study the regulation of allergic asthma is that while normal naïve (unimmunized) animals have extremely low frequency of antigen-specific T cells46, the majority of the peripheral T cells in the OVA transgenic animals are directed to OVA and do not require immunization to detect OVA-induced T cell proliferation36, although in the absence pre-sensitization by OVA, the cells may not differentiate into Th2 type cells. Therefore, we used normal (wild-type) BALB/c mice and the allergen - Aspergillus fumigatus extracts that requires sensitization to induce airway responses16 and causes allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis in humans47. In these animals, MM was able to ameliorate Aspergillus-induced airway inflammation and various indices of airway mucoid response. Thus, activation of nAChRs is critical in allergen-induced mucous cell metaplasia and airway mucus formation.

Recently, MLA was shown to suppress mucus formation in monkey lungs6. Although MLA was believed to preferentially block α7-nAChRs, recent reports suggest that MLA also reacts with α9/α10-nAChRs48. NHBE cells express α7-, α9- and α10- nAChR, and α10 are functional only in the association with α9 subunits27; moreover, α7 and α9 colocalize in rat sympathetic neurons28. In rat mast cells, the suppressive effect of nicotine on leukotriene production is mediated by an interdependent action of α7-, α9- and α10- nAChR30. Therefore, to identify the nAChR subtype(s) that regulated mucus formation, we used specific conotoxin peptides to inhibit α9/α10- and α7-nAChRs and observed that only the α7-specific conotoxin peptide ArIB[V11L,V16D]33, 34 blocked the nicotine- and IL-13-induced mucus production in NHBE cells. This inference was further confirmed by the demonstration that knockdown of α7- but not α9-/α10-specific mRNA blocked the nicotine- and IL-13-induced expression of GABAARα2 in A549 cells.

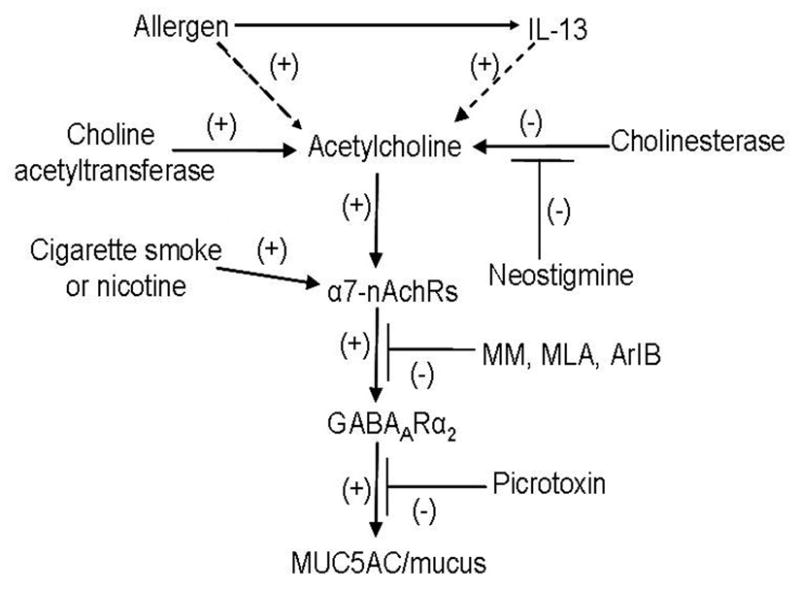

While these results clearly implicate α7-nAChRs in mucous cell physiology and mucus production, it was important to understand how the activation of these receptors would be regulated in nonsmokers (i.e., in the absence of nicotine). In vivo cholinergic transmission involves both nicotinic and muscarinic receptors and is mediated by acetylcholine. There is increasing evidence that many non-neuronal cells, including airway epithelial cells express enzymes to synthesize, degrade, and transport acetylcholine12, 39. Indeed, blocking the degradation of acetylcholine by the cholinesterase inhibitor NB promoted mucus formation and increased MUC5AC expression in NHBE cells in the complete absence of IL-13 or nicotine. Acetylcholine is the biological ligand for both nAChRs and muscarinic receptors, and the bronchial epithelial cells have functional muscarinic receptors49. Results with MLA and the atropine suggest that muscarinic receptors are not involved in the IL-13 or NB (acetylcholine)-induced mucus formation in bronchial epithelial cells. Although with the use of nAChR inhibitors we were able to show that the effects of IL-13 on mucus formation in NHBE cells is regulated by nAChRs, we were unable to show that IL-13 induces detectable levels of acetylcholine in these cells. Nonetheless, it is likely that in the absence of nicotine, acetylcholine is important in airway mucus formation and mucous cell hyperplasia/metaplasia. Together, our results suggest that α7-nAChRs, GABAARα2, and the acetylcholine metabolic pathway(s) may serve as potential targets to control airway mucus formation. A tentative scheme by which nAChRs may regulate airway mucus is presented in Fig. 7.

Figure 7. Potential relationship between nAChRs and mucus formation in NHBE cells.

Allergens or IL-13 directly or indirectly increase acetylcholine in airway epithelial cells. Acetylcholine activates α7-nAChRs that increases GABAARα2 expression that is blocked by nAChR antagonists (MM, MLA, ArIB[V11L-V16D]). Increased GABAARα2 stimulates mucus formation that is blocked by the GABAAR antagonist PIC. Dashed lines represent: not formally proven interactions.

Key Message.

This study shows that nicotine and acetylcholine promote mucus formation independent of IL-13, and totally dependent on the activation of α7-nAChRs. Moreover, nicotinic receptor antagonists block mucus formation.

Acknowledgments

Support: This work was supported in part by grants from the US Army Medical Research and Material Command (GW093005), National Institutes of Health (R01-DA017003) and funds from Lovelace Respiratory Research Institute (IMMSPT).

List of Abbreviations

- AB-PAS

Alcian blue-periodic acid-Schiff

- ALI

Air liquid interface

- COPD

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- GABAAR

γ-aminobutyric acid type A receptor

- IHC

Immunohistochemistry

- MLA

Methyllycaconitine

- MM

Mecamylamine

- nAChRs

Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors

- NHBE

Normal human bronchial epithelial

- NB

Neostigmine bromide

- PIC

Picrotoxin

Footnotes

AUTHOR DISCLOSURES: The authors have no financial conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hovenberg HW, Davies JR, Carlstedt I. Different mucins are produced by the surface epithelium and the submucosa in human trachea: identification of MUC5AC as a major mucin from the goblet cells. Biochem J. 1996;318 (Pt 1):319–24. doi: 10.1042/bj3180319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Turner J, Jones CE. Regulation of mucin expression in respiratory diseases. Biochem Soc Trans. 2009;37:877–81. doi: 10.1042/BST0370877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vestbo J. Epidemiological studies in mucus hypersecretion. Novartis Found Symp. 2002;248:3–12. discussion -9, 277–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schuster EA. Environment needs nurses who care. As I see it Am Nurse. 1992;24:25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Markewitz BA, Owens MW, Payne DK. The pathogenesis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Med Sci. 1999;318:74–8. doi: 10.1097/00000441-199908000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fu XW, Wood K, Spindel ER. Prenatal nicotine exposure increases GABA signaling and mucin expression in airway epithelium. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2011;44:222–9. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2010-0109OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gundavarapu S, Wilder JA, Rir-Sima-Ah J, Mishra NC, Singh SP, Jaramillo R, et al. Modulation of Mucus Cell Metaplasia By Cigarette Smoke/Nicotine Through GABAA Receptor Exression [Abstract] Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;181:A5442. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grunig G, Warnock M, Wakil AE, Venkayya R, Brombacher F, Rennick DM, et al. Requirement for IL-13 independently of IL-4 in experimental asthma. Science. 1998;282:2261–3. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5397.2261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuperman DA, Huang X, Koth LL, Chang GH, Dolganov GM, Zhu Z, et al. Direct effects of interleukin-13 on epithelial cells cause airway hyperreactivity and mucus overproduction in asthma. Nat Med. 2002;8:885–9. doi: 10.1038/nm734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wills-Karp M. Interleukin-13 in asthma pathogenesis. Immunol Rev. 2004;202:175–90. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.00215.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mishra NC, Rir-Sima-Ah J, Langley RJ, Singh SP, Pena-Philippides JC, Koga T, et al. Nicotine primarily suppresses lung Th2 but not goblet cell and muscle cell responses to allergens. J Immunol. 2008;180:7655–63. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.11.7655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Proskocil BJ, Sekhon HS, Jia Y, Savchenko V, Blakely RD, Lindstrom J, et al. Acetylcholine is an autocrine or paracrine hormone synthesized and secreted by airway bronchial epithelial cells. Endocrinology. 2004;145:2498–506. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fujii T, Takada-Takatori Y, Kawashima K. Basic and clinical aspects of non-neuronal acetylcholine: expression of an independent, non-neuronal cholinergic system in lymphocytes and its clinical significance in immunotherapy. J Pharmacol Sci. 2008;106:186–92. doi: 10.1254/jphs.fm0070109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xiang YY, Wang S, Liu M, Hirota JA, Li J, Ju W, et al. A GABAergic system in airway epithelium is essential for mucus overproduction in asthma. Nat Med. 2007;13:862–7. doi: 10.1038/nm1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Atherton HC, Jones G, Danahay H. IL-13-induced changes in the goblet cell density of human bronchial epithelial cell cultures: MAP kinase and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase regulation. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2003;285:L730–9. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00089.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Singh SP, Gundavarapu S, Pena-Philippides JC, Rir-Sima-Ah J, Mishra NC, Wilder JA, et al. Prenatal secondhand cigarette smoke promotes th2 polarization and impairs goblet cell differentiation and airway mucus formation. J Immunol. 2011;187:4542–52. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1101567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Singh SP, Kalra R, Puttfarcken P, Kozak A, Tesfaigzi J, Sopori ML. Acute and chronic nicotine exposures modulate the immune system through different pathways. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2000;164:65–72. doi: 10.1006/taap.2000.8897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Singh SP, Mishra NC, Rir-Sima-Ah J, Campen M, Kurup V, Razani-Boroujerdi S, et al. Maternal exposure to secondhand cigarette smoke primes the lung for induction of phosphodiesterase-4D5 isozyme and exacerbated Th2 responses: rolipram attenuates the airway hyperreactivity and muscarinic receptor expression but not lung inflammation and atopy. J Immunol. 2009;183:2115–21. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.El-Zimaity HM, Ota H, Scott S, Killen DE, Graham DY. A new triple stain for Helicobacter pylori suitable for the autostainer: carbol fuchsin/Alcian blue/hematoxylin-eosin. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1998;122:732–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harkema JR, Hotchkiss JA. In vivo effects of endotoxin on intraepithelial mucosubstances in rat pulmonary airways. Quantitative histochemistry. Am J Pathol. 1992;141:307–17. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–8. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fucile S, Sucapane A, Eusebi F. Ca2+ permeability of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors from rat dorsal root ganglion neurones. J Physiol. 2005;565:219–28. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.084871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fahy JV. Goblet cell and mucin gene abnormalities in asthma. Chest. 2002;122:320S–6S. doi: 10.1378/chest.122.6_suppl.320s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Curran DR, Cohn L. Advances in mucous cell metaplasia: a plug for mucus as a therapeutic focus in chronic airway disease. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2010;42:268–75. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2009-0151TR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Izuhara K, Ohta S, Shiraishi H, Suzuki S, Taniguchi K, Toda S, et al. The mechanism of mucus production in bronchial asthma. Curr Med Chem. 2009;16:2867–75. doi: 10.2174/092986709788803196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boyd RT. The molecular biology of neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Crit Rev Toxicol. 1997;27:299–318. doi: 10.3109/10408449709089897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sgard F, Charpantier E, Bertrand S, Walker N, Caput D, Graham D, et al. A novel human nicotinic receptor subunit, alpha10, that confers functionality to the alpha9-subunit. Mol Pharmacol. 2002;61:150–9. doi: 10.1124/mol.61.1.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lips KS, Konig P, Schatzle K, Pfeil U, Krasteva G, Spies M, et al. Coexpression and spatial association of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunits alpha7 and alpha10 in rat sympathetic neurons. J Mol Neurosci. 2006;30:15–6. doi: 10.1385/JMN:30:1:15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Razani-Boroujerdi S, Boyd RT, Davila-Garcia MI, Nandi JS, Mishra NC, Singh SP, et al. T cells express alpha7-nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunits that require a functional TCR and leukocyte-specific protein tyrosine kinase for nicotine-induced Ca2+ response. J Immunol. 2007;179:2889–98. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.5.2889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mishra NC, Rir-sima-ah J, Boyd RT, Singh SP, Gundavarapu S, Langley RJ, et al. Nicotine inhibits Fc epsilon RI-induced cysteinyl leukotrienes and cytokine production without affecting mast cell degranulation through alpha 7/alpha 9/alpha 10-nicotinic receptors. J Immunol. 2010;185:588–96. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dorion G, Israel-Assayag E, Beaulieu MJ, Cormier Y. Effect of 1,1-dimethylphenyl 1,4-piperazinium on mouse tracheal smooth muscle responsiveness. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2005;288:L1139–45. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00406.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tournier JM, Birembaut P. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors and predisposition to lung cancer. Curr Opin Oncol. 2011;23:83–7. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e3283412ea1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ellison M, Haberlandt C, Gomez-Casati ME, Watkins M, Elgoyhen AB, McIntosh JM, et al. Alpha-RgIA: a novel conotoxin that specifically and potently blocks the alpha9alpha10 nAChR. Biochemistry. 2006;45:1511–7. doi: 10.1021/bi0520129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Whiteaker P, Christensen S, Yoshikami D, Dowell C, Watkins M, Gulyas J, et al. Discovery, synthesis, and structure activity of a highly selective alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor antagonist. Biochemistry. 2007;46:6628–38. doi: 10.1021/bi7004202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Churg A, Cosio M, Wright JL. Mechanisms of cigarette smoke-induced COPD: insights from animal models. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2008;294:L612–31. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00390.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Murphy KM, Heimberger AB, Loh DY. Induction by antigen of intrathymic apoptosis of CD4+CD8+TCRlo thymocytes in vivo. Science. 1990;250:1720–3. doi: 10.1126/science.2125367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Knutsen AP, Bush RK, Demain JG, Denning DW, Dixit A, Fairs A, et al. Fungi and allergic lower respiratory tract diseases. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129:280–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.12.970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McGehee DS, Role LW. Physiological diversity of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors expressed by vertebrate neurons. Annu Rev Physiol. 1995;57:521–46. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.57.030195.002513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lips KS, Luhrmann A, Tschernig T, Stoeger T, Alessandrini F, Grau V, et al. Down-regulation of the non-neuronal acetylcholine synthesis and release machinery in acute allergic airway inflammation of rat and mouse. Life Sci. 2007;80:2263–9. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2007.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jones AK, Sattelle DB. Diversity of insect nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunits. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2010;683:25–43. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-6445-8_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sopori M. Effects of cigarette smoke on the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:372–7. doi: 10.1038/nri803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jones AK, Sattelle DB. Functional genomics of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor gene family of the nematode, Caenorhabditis elegans. Bioessays. 2004;26:39–49. doi: 10.1002/bies.10377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang J, Berg DK. Reversible inhibition of GABAA receptors by alpha7-containing nicotinic receptors on the vertebrate postsynaptic neurons. J Physiol. 2007;579:753–63. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.124578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jospin M, Qi YB, Stawicki TM, Boulin T, Schuske KR, Horvitz HR, et al. A neuronal acetylcholine receptor regulates the balance of muscle excitation and inhibition in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Biol. 2009;7:e1000265. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rehan VK, Asotra K, Torday JS. The effects of smoking on the developing lung: insights from a biologic model for lung development, homeostasis, and repair. Lung. 2009;187:281–9. doi: 10.1007/s00408-009-9158-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Carneiro J, Duarte L, Padovan E. Limiting dilution analysis of antigen-specific T cells. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;514:95–105. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-527-9_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McCormick A, Loeffler J, Ebel F. Aspergillus fumigatus: contours of an opportunistic human pathogen. Cell Microbiol. 2010;12:1535–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2010.01517.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Verbitsky M, Rothlin CV, Katz E, Elgoyhen AB. Mixed nicotinic-muscarinic properties of the alpha9 nicotinic cholinergic receptor. Neuropharmacology. 2000;39:2515–24. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(00)00124-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Profita M, Bonanno A, Montalbano AM, Ferraro M, Siena L, Bruno A, et al. Cigarette smoke extract activates human bronchial epithelial cells affecting non-neuronal cholinergic system signalling in vitro. Life Sci. 2011;89:36–43. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2011.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]