Abstract

Transgenic (mRen2)27 rats are hypertensive with impaired baroreflex sensitivity for control of heart rate compared to Hannover Sprague-Dawley rats. We assessed blood pressure and baroreflex function in male hemizygous (mRen2)27 rats (30-40 wks of age) instrumented for arterial pressure recordings and receiving into the cisterna magna either an Ang-(1-7) fusion protein or a control fusion protein (CTL-FP). The maximum reduction in mean arterial pressure achieved was -38 ± 7 mm Hg on day 3, accompanied by a 55% enhancement in baroreflex sensitivity in Ang-(1-7) fusion protein-treated rats. Both the high frequency alpha index (HF-α) and heart rate variability increased, suggesting increased parasympathetic tone for cardiac control. The mRNA levels of several components of the renin-angiotensin system in the dorsal medulla were markedly reduced including renin (-80%), neprilysin (-40%) and the AT1a receptor (-40%). However, there was 2 to 3 increase in the mRNA levels of the phosphatases PTP-1b and DUSP1 in the medulla of Ang-(1-7) fusion protein-treated rats. Our finding that replacement of Ang-(1-7) in the brain of (mRen2)27 rats reverses in part the hypertension and baroreflex impairment is consistent with a functional deficit of Ang-(1-7) in this hypertensive strain. We conclude that the increased mRNA expression of phosphatases known to counteract the phosphoinositol 3 kinase (PI3K) and mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK), as well as the reduction of renin and AT1a receptor mRNA levels may contribute to the reduction in arterial pressure and improvement in baroreflex sensitivity in response to Ang-(1-7).

Keywords: Angiotensin-(1-7), hypertension, baroreflex, (mRen2)27, phosphatases

INTRODUCTION

Transgenic (mRen2)27 rats overexpressing a murine Ren2 gene develop fulminant hypertension at an early age despite low concentrations of active renin in plasma and kidney 1-3. Hemizygous female (mRen2)27 rats have elevated angiotensin (Ang) II and reduced Ang-(1-7) in the medulla oblongata and high levels of both peptides in hypothalamic tissue compared with normotensive control Hannover Sprague Dawley (SD) rats 4. The two peptides have opposing roles in support of resting arterial pressure, since acute intracerebroventricular (ICV) administration of an Ang II antibody reduces mean arterial pressure (MAP), whereas antisera to Ang-(1-7) further increases MAP in homozygous female (mRen2)27 rats previously treated with a converting enzyme inhibitor 5. Infusion of Ang-(1-7) into the lateral ventricle of (mRen2)27 rats but not SD rats lowers MAP 6, which suggests that increasing Ang-(1-7) in this form of hypertension is an effective means of therapy. At the level of the solitary nucleus tract (nTS), endogenous Ang II attenuates baroreceptor reflex sensitivity (BRS) for control of heart rate (HR) while endogenous Ang-(1-7) enhances BRS 7. In (mRen2)27 rats, the elevated arterial pressure is associated with impaired BRS and is not lowered further with Ang-(1-7) blockade in the nTS 8. Collectively, these data led us to hypothesize that there may exist a functional deficit in lower brain stem Ang-(1-7) levels in the (mRen2)27 rat that contribute to the attenuated BRS and the hypertension.

Investigations of the potential signaling pathways involved in control of resting arterial pressure and BRS in the dorsal medulla during hypertension identified both phosphoinositol 3 kinase (PI3K) and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways in a wide range of cellular responses to Ang II within the rostral ventrolateral medulla of spontaneously hypertensive rats 9. In the nTS, PI3K is involved in maintenance of resting arterial pressure in (mRen2)27 rats and blockade of this kinase improves BRS in these animals, while there is no effect on either arterial pressure of the BRS in SD animals 10. Protein tyrosine phosphatase (PTP-1b) and dual specificity phosphatase 1 (DUSP1; also known as MKP-1) constitute a complex negative regulatory network that influences PI3K and MAPK activities, respectively 11-14. In this regard, Ang-(1-7) increased DUSP-1 activity in vascular tissue 15. Since brain Ang II and Ang-(1-7) have opposite actions on blood pressure and BRS, we hypothesize that Ang-(1-7) exerts counterregulatory actions in Ang II-activated signaling pathways in the transgenic (mRen2)27 rat.

To begin to test these hypotheses, we explored the effects on blood pressure and baroreflex function by in vivo expression of Ang-(1-7) through gene transfer of a fusion protein that forms Ang-(1-7). The advantage of this approach is that Ang-(1-7) is generated directly and independently of the concerted actions of the enzymes normally involved in its synthesis. The plasmid sequence chosen results in the release of Ang-(1-7) directly from the cell by means of a cleavage site at the carboxyl terminus recognized by the enzyme furin 16-18. This technique was successfully applied for specific and constitutive expression of several angiotensin peptides including Ang-(1-7), Ang II and Ang IV in heart, brain, kidney and other cell types 17-22. The current study was designed to establish the influence of Ang-(1-7) on baroreflex function and blood pressure control by the in vivo expression of the heptapeptide in the brain of male hemizygous (mRen2)27 transgenic rats. Furthermore, we sought to establish the impact of Ang-(1-7) expression on the components of the renin-angiotensin system (RAS), as well as the phosphatases DUSP1 and PTP-1b in hypothalamus and dorsal medulla oblongata.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Animals and surgical procedures

Fourteen (30-40 week old) male transgenic (mRen2)27 rats obtained from the Hypertension and Vascular Research Center of Wake Forest University were housed in an America Association for Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AALAC) approved facility with controlled temperature, light-dark cycles (12 h), and food and water ad libitum. The animals were randomly assigned to two study groups, either receiving an injection of 20 μL of the Ang-(1-7) fusion protein [Ang-(1-7)-FP, 1.3 micrograms/μl, n = 9] or a control fusion protein [CTL-FP, 1.7 micrograms/μl, n = 5] plasmid into the cisterna magna. All procedures were approved by the Wake Forest University School of Medicine Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Anesthesia was induced with a combination of ketamine/acepromazine injected intraperitoneally (15 mg Ketamine/0.3 mg Acepromazine/100 g of body weight) for all surgical procedures. Polyethylene catheters (PE-50 tubing; Clay Adams) were placed into a femoral artery and vein, exteriorized at the sub-scapular area and secured. The animals were allowed to recover for at least 48 h before baseline MAP and HR were measured over three consecutive days. The Ang-(1-7)-FP or CTL-FP plasmid were injected in anesthetized rats placed in a stereotaxic frame. After exposure of the atlanto-occipital membrane, a needle was inserted into the cisterna magna for injection of the plasmids. Blood pressure and HR were monitored daily in one rat for six days for information on time course, where it was determined that the peak effect was 3-4 days after injection of the plasmid before MAP returned to pre-injection values. All subsequent rats were monitored for 3 days post-injection. Rats were euthanized by decapitation on day 4 and medullary and hypothalamic tissues were collected.

Ang-(1-7) fusion protein plasmid generation

The Ang-(1-7)-FP and the CTL-FP were designed as previously reported 16;17;22. The construct contained the human prorenin signal peptide and the immunoglobulin fragment from mouse IgG2b linked to a portion of the human prorenin prosegment. The furin cleavage site and the coding sequence for Ang-(1-7) followed by a stop codon were inserted after the prorenin segment into a BglII site. An intron and polyadenylation cassette of SV40 virus from pΔLux was inserted 3’ of the stop codon 16. The construct was cloned into the pcDNA3.1 vector (Invitrogen, Karlsruhe, Germany) placed under the control of the cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter/enhancer.

Blood pressure recording and spontaneous baroreflex study

Pulsatile arterial pressure was monitored via a strain gauge transducer connected to an arterial catheter and data acquisition system (Acknowledge software; V 3.7.2; BIOPAC System Inc.) in conscious rats. HR was determined from the arterial pressure wave. Spontaneous BRS was calculated by the frequency-domain analysis method using newly developed software designed for rats (Nevrokard SA-BRS, Medistar, Ljubljana, Slovenia) as reported in our previous work 23;24.

Immunoblots

At the time of euthanasia, hypothalamic samples were dissected according to the following landmarks: the optic chiasm (anterior), the mammillary bodies (posterior), the hypothalamic sulcus (lateral), and the anterior commissure (dorsal). The medullary samples corresponded to the dorsal half of the medulla oblongata between 4 mm rostral and caudal from the obex. Medullary and hypothalamic samples from CTL-FP, Ang-(1-7)-FP and naive animals were homogenized in a buffer containing 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), 0.1% Triton, and a protease inhibitor cocktail with broad specificity for the inhibition of serine, cysteine and aspartic proteases and aminopeptidases containing 4-(2-aminoethyl) benzenesulfonyl fluoride (AEBSF), pepstatin A, E-64, bestatin, leupeptin, and aprotonin. Samples were centrifuged at 10,000 g for 15 min at 4°C. Protein concentration was measured by the bicinchoninic acid assay (BCA) method (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Samples of anti-mouse IgG2b protein (1 ng), control rat medulla, control rat medulla spiked with 1 ng of IgG2b protein, and hypothalamus and medulla from rats injected with the CTL-FP or Ang-(1-7)-FP (90 micrograms of the total protein) were separated by gel electrophoresis and proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Pierce) for 1 h at 120 V. Nonspecific binding was blocked by fat free milk in 0.1% Tween 20 in HEPES for 60 min at room temperature. The blots were reacted with a monoclonal anti-mouse IgG2b (1:1,000; M8067, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) overnight at 4°C. After several washings in PBS and Tween-PBS, the blots were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-labeled secondary anti-mouse (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ) at a 1:10,000 dilution, for 60 min at room temperature. After the final washings, the blots were incubated with Pierce Super Signal West Pico chemiluminescent substrate and exposed to Hyperfilm ECL (Amersham Biosciences). An antibody to actin was used to normalize protein content.

Reverse transcriptase (RT) real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis

RNA was isolated from tissue using the TRIZOL reagent (GIBCO Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), as directed by the manufacturer. The RNA concentration and integrity were assessed using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer with an RNA 6000 Nano LabChip (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA). Approximately 1 μg of total RNA was reverse transcribed using AMV reverse transcriptase in a 20 μL reaction mixture containing deoxyribonucleotides, random hexamers and RNase inhibitor in reverse transcriptase buffer. Heating the reverse transcriptase reaction product at 95°C terminated the reaction. For real-time PCR, 2 μL of the resultant cDNA was added to TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) with the appropriate gene-specific primer/ probe set (Applied Biosystems) or with an ACE2 primer/probe set (forward primer 5’-CCCAGAGAACAGTGGACCAAAA-3’; reverse primer 5’-GCTCCACCACACCAACGAT-3’; and probe 5’-FAM-CTCCCGCTTCATCTCC-3’) and amplification was performed on an ABI 7000 Sequence Detection System. The mixtures were heated at 50°C for 2 min, at 95°C for 10 min followed by 40 cycles at 95°C for 15 sec and 60°C for 1 min. All reactions were performed in triplicate and 18S ribosomal RNA, amplified using the TaqMan Ribosomal RNA Control Kit (Applied Biosystems), served as an internal control. The results were quantified as Ct values, where Ct is defined as the threshold cycle of PCR at which amplified product is first detected, and defined as relative gene expression (the ratio of target/control).

Statistical analysis

Two-way ANOVA was used to determine the statistical significance of differences by time and treatment (p < 0.05). One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s Post-test was employed to test the statistical significance across time and unpaired t-tests assessed differences between the two treatment groups. Values are presented as the mean ± SEM and PRISM software (GraphPad, San Diego, CA) was used for data analysis.

RESULTS

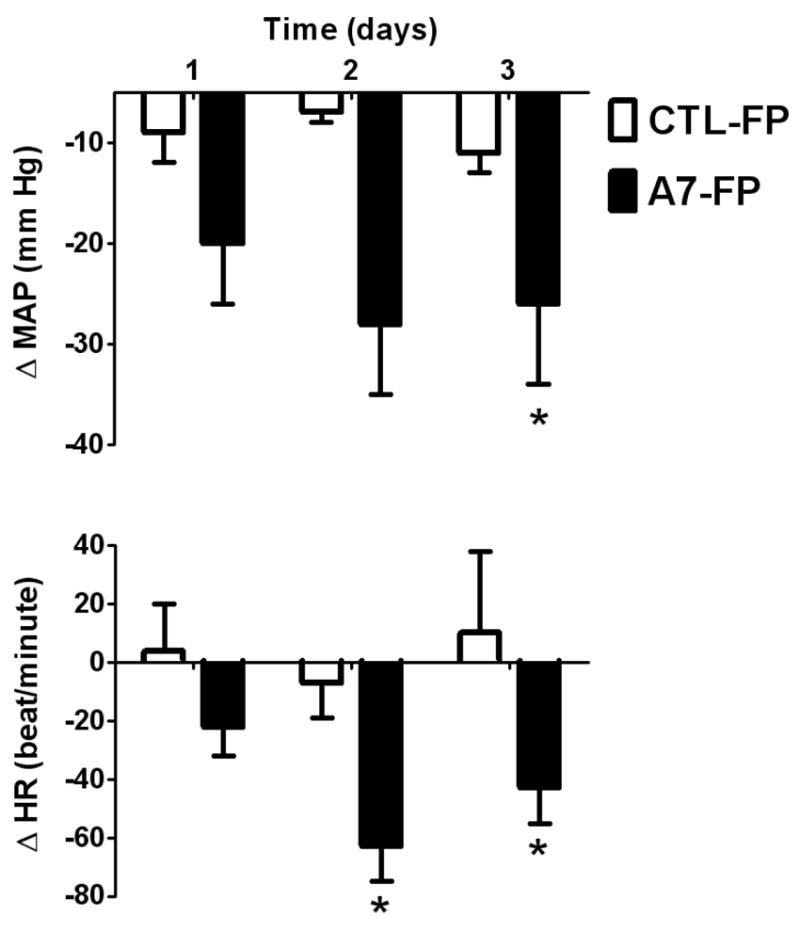

At baseline, mean arterial pressure (MAP) averaged 152 ± 6 mm Hg and HR averaged 328 ± 10 beats/min prior to assignment to the individual treatment groups. Two groups were established to study the effect of the Ang-(1-7)-FP (n = 9) or CTL-FP (n = 5) injections into the cisterna magna. There was a sustained decrease in MAP (Figure 1) reaching a maximum value of -38 ± 7 mm Hg on day 2 in the group receiving the Ang-(1-7)-FP (p < 0.034). There was no significant fall in MAP in the animals that received CTL-FP. HR followed a similar pattern of changes as observed for the MAP. The (mRen2)27 rats that received Ang-(1-7)-FP had a significant fall in HR (-63 ± 12 beats/min, day 2; (p < 0.005) whereas the CTL-FP group had no significant change in HR.

Figure 1.

Changes in mean arterial pressure (MAP) and heart rate (HR) in (mRen2)27 rats after injection into the cisterna magna of Ang-(1 7)-FP (solid bars) and CTL-FP (open bars). The MAP was monitored for 3 days following injection of the Ang-(1-7)-FP (n = 9) or CTL-FP (n = 4). * P < 0.05 vs CTL-FP.

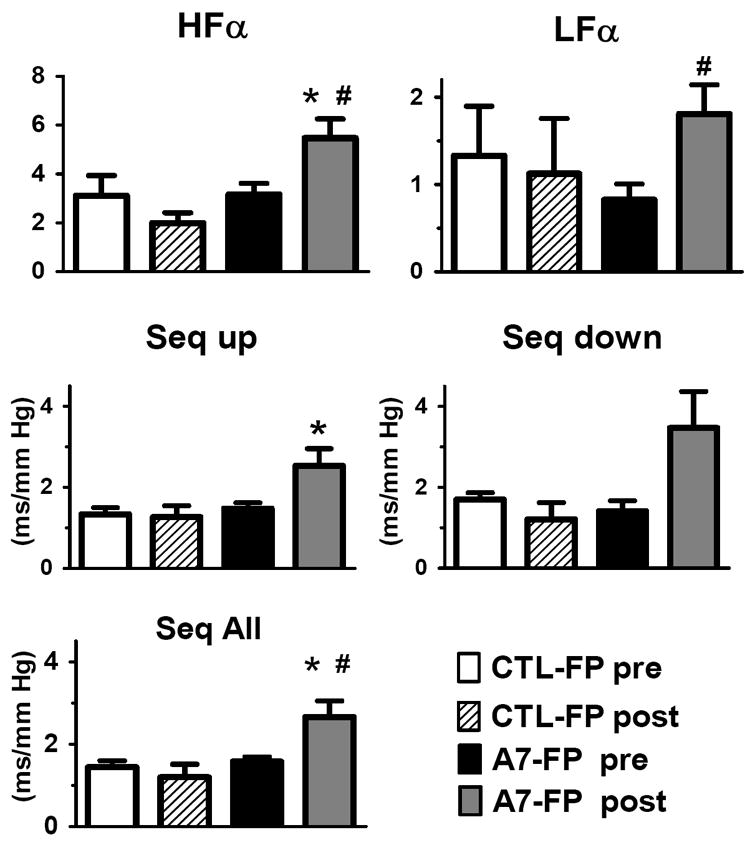

There was no difference between the two groups (Figure 2) before the injection in the BRS, HRV or BPV. Following intracisternal administration of Ang-(1-7)-FP, there was an enhancement in BRS when values from before and two days after the injection of plasmid were compared using both spectral analysis and sequence methods (Figure 2). In the Ang-(1-7)-FP group, both HF-α and LF-α increased significantly compared to pre-injection values and HF-α on day 2 was significantly higher compared to the rats that received the CTL-FP (Figure 2). BRS measured by the sequence method (sequence up, down and total) was increased in the Ang-(1-7)-FP injected animals compared to pre-injection (Figure 2) and both up sequence and total sequence were significantly enhanced in this group at day 2 compared to the control group.

Figure 2.

Frequency domain and sequence analysis of spontaneous baroreflex function, low frequency alpha (LFα), high frequency alpha (HFα), sequence up (Seq Up), sequence down (Seq Down), sequence all (Seq ALL) parameters calculated for CTL-FP and Ang-(1-7)-FP before (A7-FP pre) and after (A7-FP post) injection into the cisterna magna. CTL- FP pre (white bars), CTL- post (diagonal bars) correspond to parameters before and day 2 after intracisternal injection the CTL-FP, whereas A7-FP pre (black bar) and A7-FP post (grey bar) correspond to before and day 2 after intracisternal injection of the A7-FP. * p < 0.05 vs CTL-FP post, # p < 0.05 vs pre.

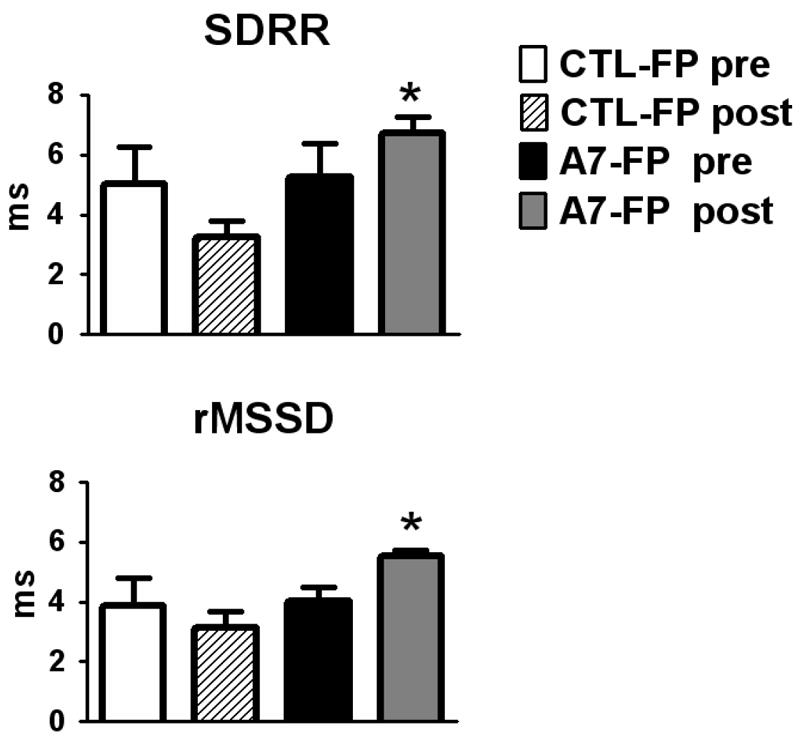

HRV increased significantly from pre-injection values measured by the time domain method as SDRR and rMSSD (Figure 3) in the Ang-(1-7)-FP treatment group and compared to the control group at 2 days post injection. There was no significant difference between the Ang-(1-7)-FP group and the control rats in HFRRI, LFRRI or the sympathovagal balance index (LFRRI/HFRRI): (0.51 ± 0.3 vs 0.36 ± 0.13) at 2 days post infusion and no pre- vs post-injection effect. There was no significant difference between the Ang-(1-7)-FP group and the control rats in BPV measured by spectral analysis as LFSAP a time domain analysis as SDMAP at 2 days post injection (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Standard deviation of the beat to beat interval (SDRR, panel A) and rMSSD (panel B) calculated for CTL-FP and Ang-(1-7)-FP (A7-FP) before and after (post) injection into the cisterna magna. CTL-pre (white bar), CTL-post (diagonal bars) correspond to parameters before and after intracisternal injection the CTL-FP, whereas A7-FP pre (black bar) and A7-FP post (grey bar) correspond to before and after intracisternal injection of the A7-FP. *p < 0.05 vs. CTL-FP post.

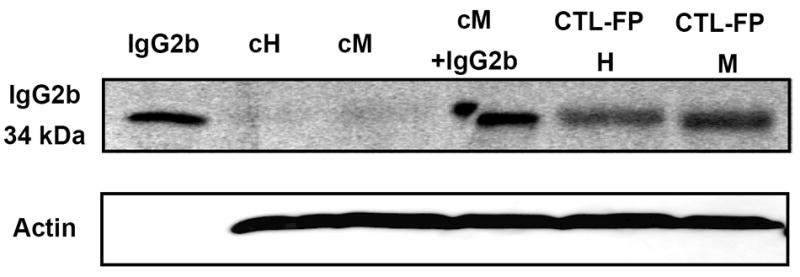

Samples of hypothalamus and medulla taken on the third day after Ang-(1-7)-FP or CTL-FP injection were assessed using for the presence of the plasmid incorporation through the detection of its reporter protein mouse IgG2b. A representative immunoblot is shown in Figure 4 and was assessed with an antibody against mouse IgG2b; the portion of the IgG2b used for the Ang-(1-7)-FP plasmid has a molecular weight of 34 kDa. The blot reveals an appropriate band of 34 kDa for the IgG2b standard but not the hypothalamic (cH) or medullary (cM) tissue from control rats. The IgG2b was detected in hypothalamus and medulla from CTL-FP treated rats, as well as cM tissue with exogenous IgG2b added (Figure 4). The expression of IgG2b was detected in both hypothalamus and dorsal medulla of CTL-FP and Ang-(1-7)-FP treated rats (n = 3 hypothalamus and n = 3 medulla, in each group), but not in the naive or control rat tissues (n = 3).

Figure 4.

Western blot showing the expression of the fusion protein in hypothalamus and dorsal medulla. The IgG2b protein generated from the construct has a molecular weight of 34 kiloDaltons (kDa). Lanes: IgG2b standard alone (1 ng); hypothalamic and medullary tissue from control rats (cH and cM, respectively); control medulla spiked with IgG2b (cM +IgG2b, 1 ng); hypothalamus and medulla from the CTL-FP administration (CTL-FP H and CTL-FP M, respectively). Tissues were collected at day 3 following CTL-FP administration when the maximal hemodynamic effect was observed Data are representative of three independent experiments for each treatment group.

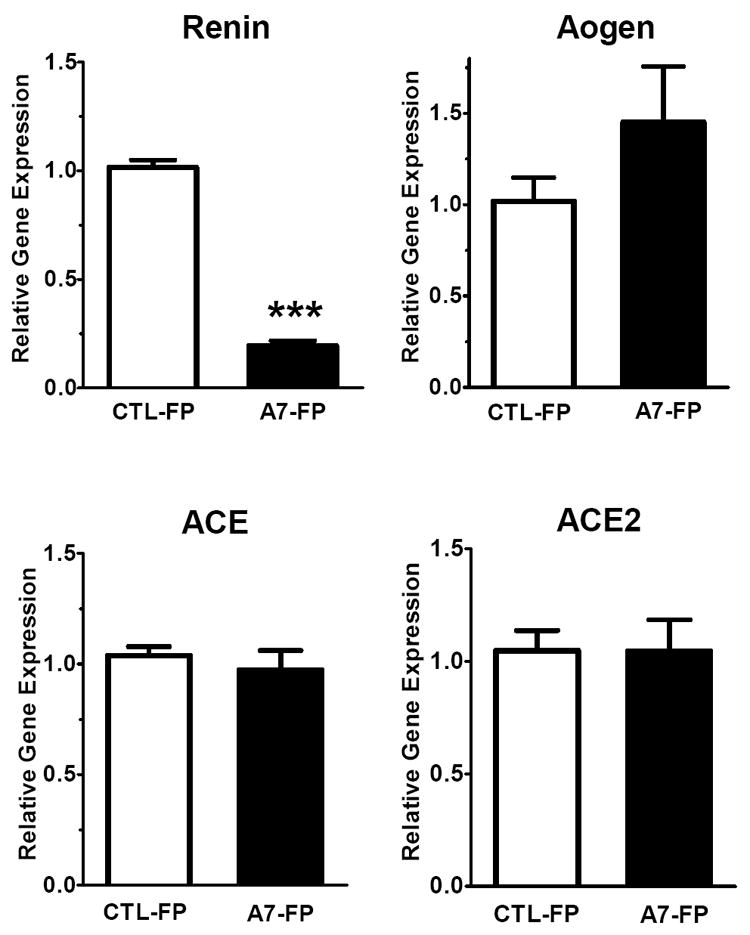

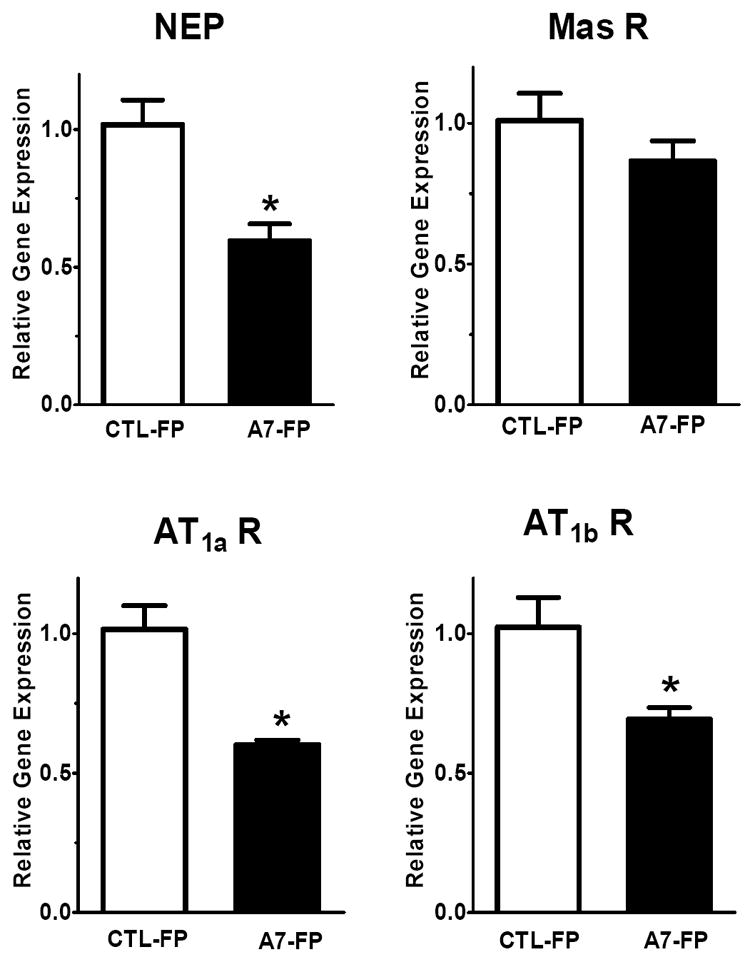

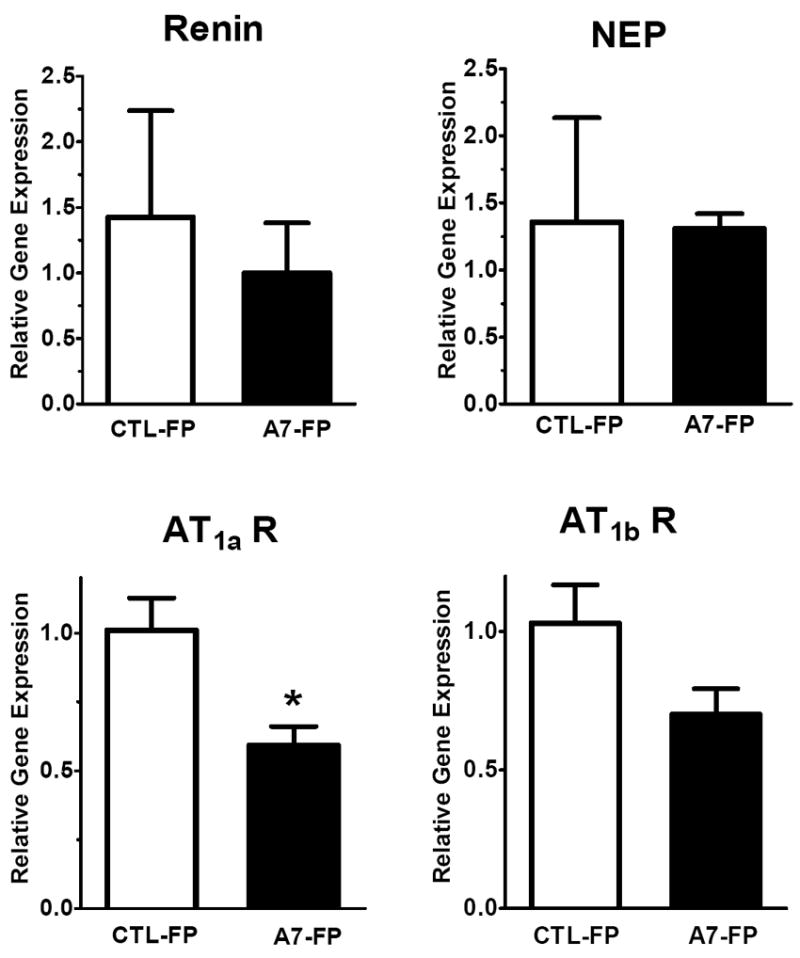

As shown in Figure 5, administration of Ang-(1-7)-FP in dorsal medulla was associated with an 80% reduction in mRNA levels of renin (-80%; 1.02 ± 0.04 vs. 0.19 ± 0.02, p<0.05, n= 4 per group) but no change in the precursor protein angiotensinogen (Aogen) or the processing enzymes ACE or ACE2 as compared to the CTL-FP group. The mRNA levels of the endopeptidase neprilysin (NEP) were significantly reduced by 40% (1.02 ± 0.02 vs. 0.59 ± 0.06, p<0.05, n = 4 per group) in the Ang-(1-7)-FP group, as was the mRNA expression for the AT1a receptor (1.02 ± 0.09 vs. 0.60 ± 0.02, p<0.05, n = 4 per group) and a 30% reduction in AT1b mRNA levels (1.03 ± 0.11 vs. 0.69 ± 0.04, p<0.05, n = 4 per group); however, we detected no difference in the Ang-(1-7)/mas receptor (Figure 6). In the hypothalamic tissues, we again found a 40% reduction in mRNA levels of the AT1a receptor (1.01 ± 0.12 vs. 0.59 ± 0.07, p<0.05, n = 3-4 per group) and a tendency for lower levels of the AT1b receptor, but no changes in renin, neprilysin (Figure 7) or other RAS components (Aogen, ACE, ACE2 - data not shown).

Figure 5.

Dorsal medulla oblongata mRNA levels of renin, angiotensinogen (Aogen), ACE and ACE2 following 3 days of Ang-(1-7)-FP treatment. The values for control (CTL-FP) and Ang-(1-7) treated animals (A7-FP) are expressed as relative target gene expression (n=4, each group). *P<0.05 and ***P<0.001 vs. CTL-FP group.

Figure 6.

Dorsal medulla oblongata mRNA levels of neprilysin (NEP), Mas receptor, AT1a and AT1b receptor isoforms following 3 days of Ang-(1-7)-FP treatment. The values for control (CTL-FP) and Ang-(1-7) treated animals (A7-FP) are expressed as relative target gene expression, (n=4, each group). *P<0.05 vs CTL-FP group.

Figure 7.

Hypothalamic mRNA levels of renin, neprilysin (NEP), Mas receptor, AT1a and AT1b receptor isoforms following 3 days of Ang-(1-7)-FP treatment. The values for control (CTL-FP) and Ang-(1-7) treated animals (A7-FP) are expressed as relative target gene expression, (n=3-4 per group). *P<0.05 vs. CTL-FP group.

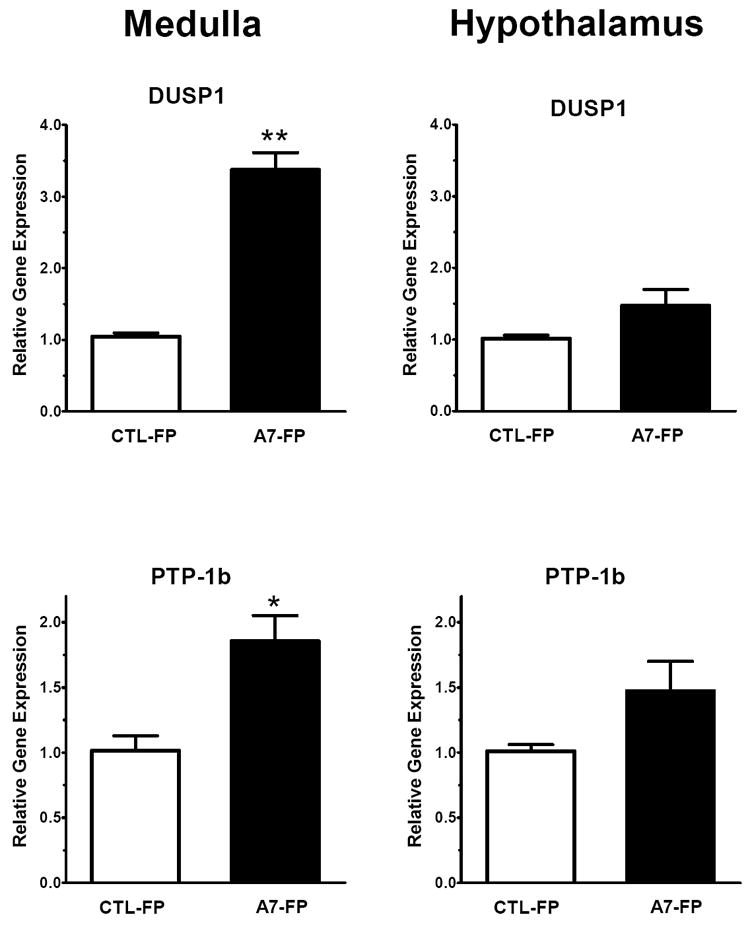

Finally, medullary mRNA levels of the phosphatases DUSP1 (1.05 ± 0.05 vs. 3.37 ± 0.24, p<0.05, n = 4 per group) and PTP-1b (1.02 ± 0.11 vs. 1.86 ± 0.2, p<0.05, n = 4 per group) were significantly increased above controls in the Ang-(1-7)-FP treated group (Figure 8, upper and lower left panels). In the hypothalamus, both DUSP1 and PTP-1b mRNA levels showed a tendency to increase in the Ang-(1-7)-FP group, but this did not reach statistical significance (Figure 8, upper and lower right panels).

Figure 8.

Dorsal medulla oblongata and hypothalamic mRNA levels of the phosphatases DUSP1 and PTP-1b following 3 days of Ang-(1-7)-FP treatment. The values for control (CTL-FP) and Ang-(1-7) treated animals (A7-FP) are expressed as relative target gene expression, (n=4, each group). *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 vs. CTL-FP group.

DISCUSSION

The administration of the Ang-(1-7)-FP vector in the cisterna magna of male hemizygous (mRen2)27 rats produced a significant decrease in MAP over the span of three days, concomitant with expression of the IgG2b reporter protein in the dorsal medullary tissue. There was a parallel improvement of the spontaneous BRS associated with enhancement of indices of HRV parasympathetic/vagal function. It is not known whether the lowering of blood pressure indirectly, or local expression of Ang-(1-7) directly influences the reflex control of HR and improvement of vagal tone. However, Ang-(1-7) exerts a tonic facilitation of the BRS at the nTS without changes in resting MAP25. Ang-(1-7) lowers blood pressure in the (mRen2)27 rat during infusion into the lateral cerebral ventricles 6 and intracerebroventricular Ang-(1-7) improves BRS 26. Therefore, actions of Ang-(1-7) in the medulla and potentially the hypothalamus may contribute to the lowering of blood pressure, as well as the enhanced baroreflex function observed in the present study.

The Ang-(1-7)-FP expression in brain corrects the deficit in baroreflex function in the hypertensive (mRen)27 strain. The lower BRS in the (mRen2)27 rats is accompanied by loss of endogenous tone for Ang-(1-7) facilitation of BRS in the nTS since direct injection of the Ang-(1-7) receptor antagonist D-Ala7-Ang-(1-7) fails to reduce BRS 8. We previously showed that nTS administration of an ACE inhibitor but not an AT1 receptor antagonist improves the BRS in the transgenic rats 27. Moreover, the beneficial effects of the ACE inhibitor were blocked by D-Ala7-Ang-(1-7) but not a bradykinin B2 receptor antagonist 27. Indeed, these findings are consistent with our observations in older SD rats where the impaired BRS is associated with the loss of Ang-(1-7) influence in the nTS 28. The older SD rats have reduced mRNA for the Ang-(1-7) forming enzyme neprilysin in dorsal medulla, suggesting a potential mechanism for the loss of locally produced Ang-(1-7) 28. While young (mRen2)27 rats have impaired reflexes with no difference in expression of Ang-(1-7) forming enzymes such as neprilysin and ACE2 in the dorsal medulla, the current experimental animals are 30 - 40 weeks of age and they may be influenced by the aging process 8. Interestingly, 60 week old (mRen2)27 rats have significantly lower mRNA levels of ACE2, neprilysin, ACE, and the mas receptor in the dorsal medulla as compared to younger (mRen2)27 rats 28. In contrast, hypothalamic mRNA levels of neprilysin are higher in old animals and we found no changes in ACE2 or mas receptor mRNA expression 29. Altered expression of ACE and neprilysin may directly influence the imbalance of tissue Ang II and Ang-(1-7) levels in the dorsal medulla and a lower density of the mas receptor may reduce sensitivity to Ang-(1-7). Therefore, the combination of reduced expression of the peptide and its receptor may lead to diminished actions of Ang-(1-7) and the poor BRS observed in the (mRen2)27. Indeed, this local environment may particularly facilitate the beneficial effects of Ang-(1-7)-FP administration to restore BRS and normalize blood pressure.

The improvement in BRS and HRV during Ang-(1-7)-FP treatment in (mRen2)27 transgenic rats was characterized by a high HF-α (compared to the control rats) as calculated by cross-spectral analysis. Furthermore, time domain measurement of spontaneous BRS and the sequence Up-BRS, an accepted measure for tonic parasympathetic cardiac control, was also higher following Ang-(1-7)-FP administration 30-33. Indeed, the Seq BRS-UP is improved to a greater extent by Ang-(1-7)-FP than the Seq BRS-DOWN which is mainly linked to the sympathetic system 34. The slight increase in LF-α could be due to activation of the sympathetic system as a result of the decline in MAP. Reduced HRV is an independent predictor for cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular mortality 7;35. In this study, both SDRR and rMSSD indices of HRV, which primarily reflect the vagal activity of the heart, were significantly increased following Ang-(1-7)-FP injection 35. Together, these data support the tenet that Ang-(1-7) may facilitate activation of the parasympathetic system. Ang-(1-7) improves bradycardia in response to an increase in blood pressure, a vagally mediated effect and the opposite effects occurs following blockade of the peptide in the nTS of the SHR and Wistar rats 6;37;38.

The systemic administration of Ang-(1-7) reduces blood pressure in male SHR, although this is likely a transient effect 39. Central Ang-(1-7) also lowers MAP when infused into the cerebral lateral ventricles of hypertensive (mRen2)27, but not SD rats 6. Therefore, the reduction in blood pressure the current study is consistent with the local and continuous generation of Ang-(1-7) in the brain of the hypertensive (mRen2)27 rats that may counteract the central actions of an activated Ang II-AT1 receptor axis. The replacement of Ang-(1-7) using the fusion protein approach is not a permanent effect since the plasmid is degraded over time; however, probe expression (IgG2b) was detected at 3 days post-injection - a time point when the physiological effects on MAP and BRS were evident.

Ang II activates both PI3K and MAPK pathways to exert cardiovascular actions in the central nervous system 40-42. MAPK may contribute to the resting MAP at the level of the RVLM in normotensive animals; however, PI3K signaling pathways are more evident in hypertensive animals 9;43. Indeed, blockade of the PI3K pathway in the nTS reduces MAP and improves BRS in the (mRen2)27 rats 42. Abundant evidence suggests that Ang-(1-7) counteracts the cellular actions of Ang II potentially through reduced ERK1/2 activation, and the cellular mechanism for this effect may involve activation of cellular phosphatases such as DUSP1 44-47. In fact, the animals treated with the Ang-(1-7)-FP exhibited higher mRNA levels of the phosphatases DUSP1 and PTP-1b in the dorsal medulla that were associated with lower blood pressure and an improved BRS. Moreover, Arnold et al. demonstrate that nTS injection of a PTP-1b inhibitor impaired BRS in normotensive rats suggesting that PTP-1b tone is important for preservation of the resting baroreflex 48. Presently, we do not know whether the increased mRNA levels of DUSP1 and PTP-1b result from the alterations in hemodynamics or reflect the direct actions of Ang-(1-7). The PI3K inhibitor LY294002 administered into the nTS of the (mRen2)27 improved BRS and lowered MAP 10. Since DUSP1 and PTP-1b influence MAPK and PI3K, respectively, we propose that the activation of PTP-1b in medulla may be one mechanism contributing to the improvements in hemodynamic function by Ang-(1-7) 13;49.

In the present study, administration of Ang-(1-7)-FP in the (mRen2)27 strain reduced the mRNA levels of renin, neprilysin and the AT1a receptor subtype in medullary tissue while other components including angiotensinogen, mas receptor, ACE and ACE2 were not changed. Lower expression of the AT1a receptor, the predominant isoform in the rodent brain, would shift activity of the RAS away from the Ang II-AT1 receptor axis. We clearly acknowledge the extent of a reduction in the AT1 receptor mRNA that leads to functional changes in the receptor protein or contributes to the differences in the balance of the kinases/phosphatases and the cardiovascular improvements are not presently known. We previously demonstrated that Ang-(1-7) treatment in the kidney reduced AT1 receptor binding which was blocked by the D-Ala7-Ang-(1-7) receptor antagonist 50. Moreover, transgenic mice that do not express the mas receptor exhibit markedly higher expression of the AT1 receptor 51. The reduction in mRNA levels for renin and neprilysin in the medulla may reflect feedback inhibition by Ang-(1-7) as these enzymes would be involved in the formation of the peptide, although the reduction in renin would tend to reduce Ang II as well. Moreover, neprilysin has peptide substrates other than Ang I that may exhibit cardiovascular actions 52. Additional studies are required to verify the functional consequences that were associated with changes in the mRNAs of the RAS components, as well as their potential contribution to the improved MAP and BRS. The lack of an effect of Ang-(1-7)-FP on the mRNA levels of RAS components apart from the AT1a receptor in the hypothalamus may reflect relatively lower Ang-(1-7) content in this area as the injection site was more proximal to the dorsal medulla; however, we did not quantify the extent of IgG2b expression at this site. Moreover, further studies are required to quantify the local changes in Ang-(1-7) content in these areas following the administration of the vector.

In summary, our results support the tenet that a deficit in Ang-(1-7) in the brain of hypertensive (mRen2)27 rats may be a contributing factor to higher blood pressure and altered autonomic balance in this strain. The novel technique of gene transfer of a selective fusion protein capable of releasing Ang-(1-7) lowers blood pressure and restores normal autonomic balance. Furthermore, expression of the Ang-(1-7)-FP was associated with higher medullary mRNA levels of the phosphatases DUSP1 and PTPb1 known to be involved in counteracting the signaling pathways known downstream of Ang II (Figure 7). We conclude that central regulation of Ang-(1-7) may be an important therapeutic target to improve cardiovascular outcome and autonomic function.

Acknowledgments

We particularly acknowledge Dr. Timothy Reudelhuber for providing the fusion protein and his comments to the manuscript. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grants HL51952 and HL56973. Maria A. Garcia-Espinosa was supported in part by a COSEHC Warren Trust Fellowship during these studies. The support of Unifi, Inc., Greensboro, NC, and Farley-Hudson Foundation, Jacksonville, NC is also acknowledged. Dr. Hossam Shaltout is a faculty member in the department of Pharmacology, School of Pharmacy, University of Alexandria, Egypt.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No relationships to disclose.

References

- 1.Mullins JJ, Peters J, Ganten D. Fulminant hypertension in transgenic rats harbouring the mouse Ren-2 gene. Nature. 1990;344:541–544. doi: 10.1038/344541a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barrett GL, Mullins JJ. Studies on blood pressure regulation in hypertensive Ren-2 transgenic rats. Kidney Int. 1992;41(Suppl.37):S-125–S-128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moriguchi A, Brosnihan KB, Kumagai H, Ganten D, Ferrario CM. Mechanisms of hypertension in transgenic rats expressing the mouse Ren-2 gene. Am J Physiol. 1994;266:R1273–R1278. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1994.266.4.R1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Senanayake PD, Moriguchi A, Kumagai H, Ganten D, Ferrario CM, Brosnihan KB. Increased expression of angiotensin peptides in the brain of transgenic hypertensive rats. Peptides. 1994;15:919–926. doi: 10.1016/0196-9781(94)90051-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moriguchi A, Tallant EA, Matsumura K, Reilly TM, Walton H, Ganten D, Ferrario CM. Opposing actions of Angiotensin-(1-7) and Angiotensin II in the brain of transgenic hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 1995;25:1260–1265. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.25.6.1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dobruch J, Paczwa P, Lon S, Khosla MC, Szczepanska-Sadowska E. Hypotensive function of the brain angiotensin-(1-7) in Sprague Dawley and renin transgenic rats. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2003;54:371–381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Diz DI, Arnold AC, Nautiyal M, et al. Angiotensin peptides and central autonomic regulation. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2011;11:131–137. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2011.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Diz DI, Garcia-Espinosa MA, Gallagher PE, Ganten D, Ferrario CM, Averill DB. Angiotensin-(1-7) and baroreflex function in nucleus tractus solitarii of (mRen2)27 transgenic rats. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2008;51:542–548. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e3181734a54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seyedabadi M, Goodchild AK, Pilowsky PM. Differential role of kinases in brain stem of hypertensive and normotensive rats. Hypertension. 2001;38:1087–1092. doi: 10.1161/hy1101.096054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Logan EM, Aileru AA, Shaltout HA, Averill DB, Diz DI. The functional role of PI3K in maintenance of blood pressure and baroreflex suppression in (mRen2)27 and mRen2.Lewis rat. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2011;58:367–373. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e31822555ca. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Owens DM, Keyse SM. Differential regulation of MAP kinase signalling by dual-specificity protein phosphatases. Oncogene. 2007;26:3203–3213. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dickinson RJ, Keyse SM. Diverse physiological functions for dual-specificity MAP kinase phosphatases. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:4607–4615. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Camps M, Nichols A, Arkinstall S. Dual specificity phosphatases: a gene family for control of MAP kinase function. FASEB J. 2000;14:6–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pearson G, Robinson F, Beers Gt, Xu BE, Karandikar M, Berman K, Cobb MH. MAPK pathways: regulation and physiological funcitonas. Endocr Rev. 2001;22:153–183. doi: 10.1210/edrv.22.2.0428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tallant EA, Gallagher PE. Angiotensin-(1-7) upregulates the mitogen activated phosphatase DUSP1 in vascular smooth muscle cells. Hypertension. 2007;50:E77. Abstract. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Methot D, LaPointe MC, Touyz RM, Yang XP. Tissue targeting of angiotensin peptides. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:12994–12999. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.20.12994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Kats JP, Methot D, Paradis P, et al. Use of a biological peptide pump to study chronic peptide hormone action in transgenic mice. Direct and indirect effects of angiotensin II on the heart. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:44012–44017. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106132200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Botelho-Santos GA, Sampaio WO, Reudelhuber TL, et al. Expression of an angiotensin-(1-7)-producing fusion protein in rats induced marked changes in regional vascular resistance. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;292:H2485–H2490. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01245.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ferreira AJ, Pinheiro SV, Castro CH, et al. Renal function in transgenic rats expressing an angiotensin-(1-7)-producing fusion protein. Regul Pept. 2006;137:128–133. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2006.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Santos RA, Ferreira AJ, Nadu AP, et al. Expression of an angiotensin-(1-7)-producing fusion protein produces cardioprotective effects in rats. Physiol Genomics. 2004;17:292–299. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00227.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang Y, Qian C, Roks AJ, Silversides DW, Reudelhuber TL. Circulating rather than cardiac angiotensin-(1-7) stimulates cardioprotection after myocardial infarction. Circ Heart Fail. 2010;3:286–293. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.109.905968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Botelho-Santos GA, Sampaio WO, Reudelhuber TL, et al. Expression of an angiotensin-(1-7)-producing fusion protein in rats induced marked changes in regional vascular resistance. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;292:H2485–H2490. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01245.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mancia G, Omboni S, Parati G. Assessment of antihypertenisve treatment by ambulatory blood pressure. J Hypertens. 1997;15:S43–S50. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199715022-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shaltout HA, Chappell MC, Rose JC, Diz DI. Exaggerated sympathetic mediated responses to behavioral or pharmacological challenges following antenatal betamethasone exposure. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2011;300:E979–E985. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00636.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chaves GZ, Caligiorne SM, Santos RAS, Khosla MC, Campagnoles-Santos MJ. Evidence that endogenous angiotensin-(1-7) participates in the modulation of the baroreflex at the nucleus tractus solitarii. Hypertension. 1995;25:1389. abstract. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Campagnole-Santos MJ, Heringer SB, Batista EN, Khosla MC, Santos RAS. Differential baroreceptor reflex modulation by centrally infused angiotensin peptides. Am J Physiol. 1992;263:R89–R94. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1992.263.1.R89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Isa K, Arnold AC, Westwood BM, Chappell MC, Diz DI. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition, but not AT(1) receptor blockade, in the solitary tract nucleus improves baroreflex sensitivity in anesthetized transgenic hypertensive (mRen2)27 rats. Hypertens Res. 2011;34:1257–1262. doi: 10.1038/hr.2011.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gilliam-Davis S, Gallagher PE, Payne VS, et al. Long-term systemic angiotensin II type 1 receptor blockade regulates mRNA expression of dorsomedial medulla renin-angiotensin system components. Physiol Genomics. 2011;43:829–835. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00167.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garcia-Espinoza MA, Gallagher PE, Ferrario CM, Ganten D, Diz DI. Increase in neprilysin activity in the hypothalamus of the (mRen2)27 transgenic rat. FASEB J. 2006;20:A360. Abstract. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mitchell KD, Bagatell SJ, Miller CS, Mouton CR, Seth DM, Mullins JJ. Genetic clamping of renin gene expression induces hypertension and elevation of intrarenal Ang II levels of graded severity in Cyp1a1-Ren2 transgenic rats. J Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone Syst. 2006;7:74–86. doi: 10.3317/jraas.2006.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Parati G, Frattola A, Di RM, Castiglioni P, Pedotti A, Mancia G. Effects of aging on 24-h dynamic baroreceptor control of heart rate in ambulant subjects. Am J Physiol. 1995;268:H1606–H1612. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1995.268.4.H1606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shaltout HA, Abdel-Rahman AA. Mechanism of fatty acids induced suppression of cardiovascular reflexes in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;314:1328–1337. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.086314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang YP, Cheng YJ, Huang CL. Spontaneous baroreflex measurement in the assessment of cardiac vagal control. Clin Auton Res. 2004;14:189–193. doi: 10.1007/s10286-004-0192-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Parati G, Di RM, Mancia G. Dynamic modulation of baroreflex sensitivity in health and disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001;940:469–487. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb03699.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stein PK, Bosner MS, Kleiger RE, Conger BM. Heart rate variability: a measure of cardiac autonomic tone. Am Heart J. 1994;127:1376–1381. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(94)90059-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sgoifo A, De Boer SF, Westenbroek C, et al. Incidence of arrhythmias and heart rate variablitly in wild-type rats exposed to social stress. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2011;273:H1754–H1760. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.273.4.H1754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chaves GZ, Caligiorne SM, Santos RAS, Khosla MC, Campagnole-Santos MJ. Modulation of the baroreflex control of heart rate by angiotensin-(1-7) at the nucleus tractus solitarii of normotensive and spontaneously hypertensive rats. J Hypertens. 2000;18:1841–1848. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200018120-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Laitinen T, Hartikainen J, Niskanen L, Geelen G, Lansimies E. Sympathovagal balance is major determinant of short-term blood pressure variability in healthy subjects. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:H1245–H1252. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.276.4.H1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Benter IF, Ferrario CM, Morris M, Diz DI. Antihypertensive actions of angiotensin-(I-7) in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol. 1995;269:H313–H319. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1995.269.1.H313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Daniels D, Yee DK, Fluharty SJ. Angiotensin II receptor signalling. Exp Physiol. 2007;92:523–527. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2006.036897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hunyady L, Catt KJ. Pleiotropic AT1 receptor signaling pathways mediating physiological and pathogenic actions of angiotensin II. Mol Endocrinol. 2006;20:953–970. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mehta PK, Griendling KK. Angiotensin II cell signaling: physiological and pathological effects in the cardiovascular system. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;292:C82–C97. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00287.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Veerasingham SJ, Yamazato M, Berecek KH, Wyss JM, Raizada MK. Increased PI3-kinase in presympathetic brain areas of the spontaneously hypertensive rat. Circ Res. 2005;96:277–279. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000156275.06641.b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gallagher PE, Ferrario CM, Tallant EA. MAP kinase/phosphatase pathway mediates the regulation of ACE2 by angiotensin peptides. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2008;295:C1169–C1174. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00145.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tallant EA, Landrum MH, Gallagher PE. Angiotensin-(1-7) attenuates mitogen activated protein kinase activation. FASEB J. 2001;15:A778. Abstract. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gava E, Samad-Zadeh A, Zimpelmann J, et al. Angiotensin-(1-7) activates a tyrosine phosphatase and inhibits glucose-induced signalling in proximal tubular cells. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009 doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfn736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sampaio WO, Henrique de CC, Santos RA, Schiffrin EL, Touyz RM. Angiotensin-(1-7) counterregulates angiotensin II signaling in human endothelial cells. Hypertension. 2007;50:1093–1098. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.106.084848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Arnold AC, Nautiyal M, Diz DI. Protein phosphatase 1b in the solitary tract nucleus is necessary for normal baroreflex function. J Card Pharm. 2012 doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e31824ba490. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cheng A, Dube N, Gu F, Tremblay ML. Coordinated action of protein tyrosine phosphatases in insulin signal transduction. Eur J Biochem. 2002;269:1050–1059. doi: 10.1046/j.0014-2956.2002.02756.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Clark MA, Tommasi EN, Bosch SM, Tallant EA, Diz DI. Angiotensin-(1-7) reduces renal angiotensin II receptors through a cyclooxygenase dependent pathway. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2003;41:276–283. doi: 10.1097/00005344-200302000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pinheiro SV, Ferreira AJ, Kitten GT, et al. Genetic deletion of the angiotensin-(1-7) receptor Mas leads to glomerular hyperfiltration and microalbuminuria. Kidney Int. 2009;75:1184–1193. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rice GI, Thomas DA, Grant PJ, Turner AJ, Hooper NM. Evaluation of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE), its homologue ACE2 and neprilysin in angiotensin peptide metabolism. Biochem J. 2004;383:45–51. doi: 10.1042/BJ20040634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]