Abstract

Biomedical optical imaging is rapidly evolving because of its desirable features of rapid frame rates, high sensitivity, low cost, portability and lack of radiation. Quantum dots are attractive as imaging agents owing to their high brightness, and photo- and bio-stability. Here, the current status of in vitro and in vivo real-time optical imaging with quantum dots is reviewed. In addition, we consider related nanocrystals based on solid-state semiconductors, including upconverting nanoparticles and bioluminescence resonance energy transfer quantum dots. These particles can improve the signal-to-background ratio for real-time imaging largely by suppressing background signal. Although toxicity and biodistribution of quantum dots and their close relatives remain prime concerns for translation to human imaging, these agents have many desirable features that should be explored for medical purposes.

Keywords: in vivo imaging, medical application, molecular imaging, nanoparticles, optical imaging, quantum dot, real-time imaging, upconverting nanoparticle

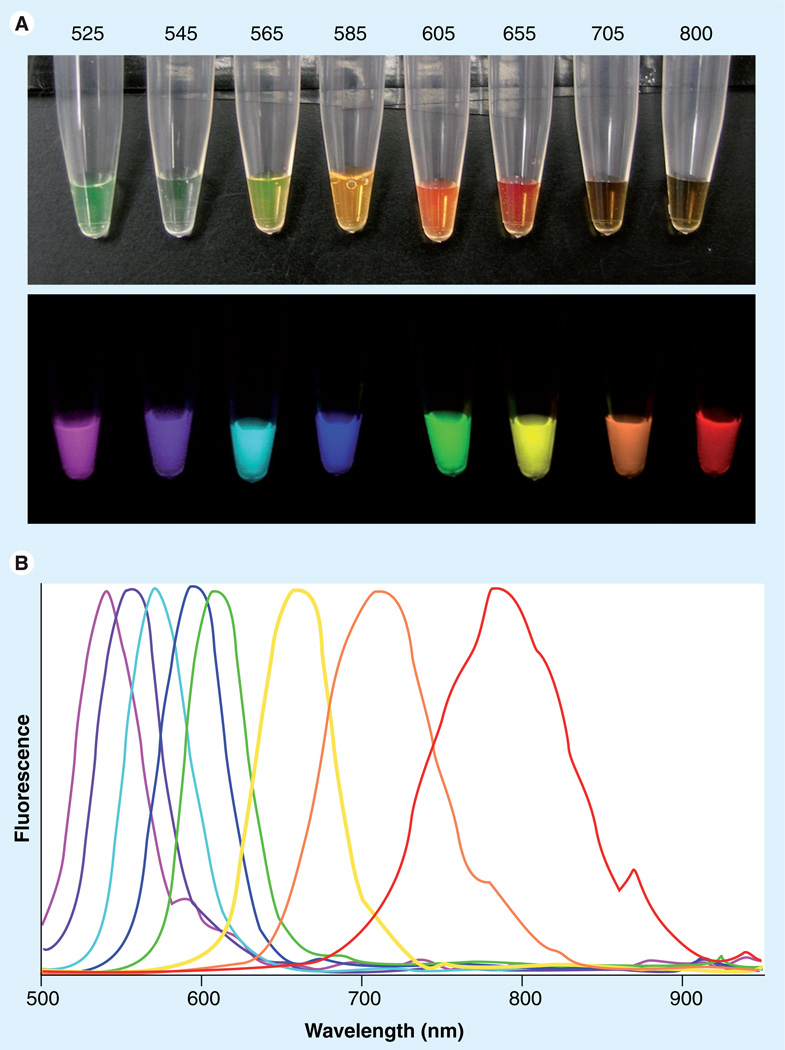

Optical imaging has become a robust tool in biological research, providing both in vitro and in vivo information [1,2]. The advantages of optical imaging are its high sensitivity, high frame rate, relatively low cost, portability, absence of radiation exposure and ability to multiplex several colors at once [3]. Real-time imaging, which is defined as acquiring serial images at frame rates of more than ten frames per second, makes it possible to use imaging during surgery, endoscopy or interventional procedures. For these reasons it is attractive as a method for early cancer detection using various endoscopies and lymphatic imaging as well as for image-guided intervention [3–5]. In order to be suitable for in vivo real-time optical imaging, fluorophores must have high quantum yields resulting in high-intensity emissions and must also be resistant to photobleaching so that continuous imaging can be performed. Bright fluorescence can decrease the exposure time, resulting in higher frame rates. Quantum dots (QDs) are a family of semiconductor fluorescent nanocrystals that have very high quantum yields and demonstrate excellent photo- and bio-stability compared with organic fluorescent dyes [6–8]. Bioapplicable QDs contain at least two semiconductor materials with organic coating in an onion-like structure. The core nanocrystals can tune the basic optical properties. For example, their fluorescence wavelength, quantum yield and lifetime can be altered by addition of an epitaxial-like shell made of another semiconductor. In such core/shell nanocrystals, the shell provides a physical barrier between the optically active core and the surrounding medium, thus making the nanocrystals less sensitive to environmental changes, surface chemistry and photo-oxidation. The shell further provides an efficient passivation of the surface trap states, giving rise to a strongly enhanced fluorescence quantum yield. This effect is a fundamental prerequisite for the use of nanocrystals in applications such as biological labeling and light-emitting devices, which rely on their emission properties [9]. To be biocompatible and feasible for the surface conjugation chemistry, an organic coating on the surface of the shell is necessary to obtain hydrophilicity and avoid aggregation in the buffered aqueous solution. Since QDs are tunable – based on their size and structure – a narrow-width emission light can be generated across the visible and near-infrared (NIR) spectrum depending on the size and doping characteristics of the nanocrystal (Figure 1). QDs of varying emission wavelengths can be excited with one broadband excitation source. This permits multicolor imaging because multiple narrow-band emissions can be distinguished after excitation with a single light source. By contrast, organic fluorophores in the visible range emit with a broader emission profile and generally have narrow Stokes shifts, which can overlap each other. Organic fluorophores have distinct absorption profiles that may require separate excitation of each fluorophore, decreasing the possible frame rate. Here, we review the use of QDs in biomedical imaging, including multicolor applications. The future prospects and possible medical applications of real-time optical imaging using QDs and related nanocrystals will also be discussed.

Figure 1. Wide range of fluorescence can be emitted from quantum dots by a single excitation light with narrow emission peaks.

(A) White light and spectrally unmixed fluorescence images of quantum dots (QD525, 545, 565, 585, 605, 655, 700 and 800; Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, CA, USA) excited by a single blue light. (B) Spectra of emission fluorescence corresponding to each quantum dot.

In vitro imaging using QDs

The biomedical applications of QDs have been steadily progressing since their introduction approximately a decade ago. Although most of the excitement surrounding QDs arises from their potential in vivo applications, nonetheless numbers of important in vitro cell labeling and molecular targeting studies have been conducted prior to the in vivo applications. For successful bioapplication, surface organic coating is needed for QDs to be water soluble and avoid self-aggregation for additional modifications because QDs’ cores/shells are synthesized in nonpolar solvents and are hydrophobic. For targeting specific molecules on the cell surface, further conjugation chemistry between organic coated QDs and targeting bioactive molecules needs to be successfully performed. Therefore, in order to obtain the functional cell-labeling compound, skillful surface and conjugation chemistries are indispensable.

Early in vitro studies focused on using QDs to label cells. Jaiswal et al. labeled HeLa cells with QDs by incubating them with dihydrolipoic acid-capped QDs. After washing away the excess QDs, the remaining cells demonstrated endocytosis of QDs with storage in vesicles. Further analysis of these vesicles revealed that many were located in a juxtanuclear position, later demonstrated to be the microtubule organizing center. Jaiswal et al. also used the avidin–biotin system to label cells with QDs. They biotinylated the membrane of target cells, and added avidin-conjugated QDs to label cells [10]. They demonstrated the potential utility of QDs in cell tracking.

However, in order to use QDs to gather information about specific cellular processes in real time, a more specific cellular target must be sought. Investigators began by attaching antibodies to QDs to target extracellular receptors. Using anti-HER2 antibodies along with a biotinylated secondary antibody, streptavidin-conjugated QDs were shown to effectively and specifically label live HER2-positive cells [11]. Once this method of targeting QDs to extra-cellular targets was established, it afforded researchers the opportunity to specifically label many different antibodies directed at extracellular targets.

To gain more knowledge about cellular dynamics, it is necessary to label a target of interest and follow it over time. This is very feasible with QDs owing to their resistance to photobleaching. Lidke et al. used QDs conjugated to EGF to target the EGF receptor (EGFR) and, thus, follow EGFR dynamics in real time. The EGFR signals downstream to its effectors through a receptor tyrosine kinase signaling cascade. They were able to visualize receptor dimerization, internalization and interaction with downstream effectors in real time [12]. Young et al. performed a similar experiment looking at G-protein-coupled receptors, another major receptor signaling cascade with numerous effectors. QDs were conjugated to bombesin and/or angiotensin II and then used to track receptor internalization [13]. This definitively demonstrated the dynamic environment of the G-protein-coupled receptor and allowed investigators to visualize ligand-induced receptor internalization after ligand binding.

While QDs can be used to monitor the early endocytic process following ligand binding, the fate of the receptor and the QD may diverge. For instance, while receptors are endocytosed and can be recycled, the QD may separate from the bound receptor and become sequestered in endocytic vesicles. Interestingly, neurons rely heavily on vesicle membrane trafficking intracellularly to move cargo to either end of the highly polarized neuron. This presents an opportunity to use QDs to specifically label membrane proteins, and follow the protein as it is shuttled around the neuron. Cui et al. used NGF conjugated to QDs to visualize, in real time, the retrograde motion that NGF-containing vesicles exhibit within the axon. This study demonstrated the intricacies of the movement of NGF within the neuron [14]. Similarly, Dahan et al. used QDs conjugated to the glycine receptor to track the location and dynamic movement of glycine receptors along the neuron [15].

In addition to dynamically visualizing major membrane-bound receptor pathways, QDs have also been used to track the dynamic nature of structural cell-surface proteins. Chen et al. conjugated integrins to QDs to better define differences in integrin mobility between differentiated cells and progenitors [16].

Since QDs are bright enough to visualize as a single crystal with high-resolution microscopes, QDs allow us to observe the kinetics of a single receptor as described above. However, the conventional QDs display their own dynamic behavior in the form of intermittent photoluminescence, also known as blinking, which happens totally at random [17]. The ‘off ’ photoluminescence state can last up to several seconds; therefore, this can be a limitation for continuous real-time observation of a single receptor.

The fact that QDs endocytosed by cells are sequestered in vesicles is a potential limitation to their use. Therefore, methods have been developed to bypass vesicle sequestration. One method is to microinject the conjugated QDs directly into the cell organelle of interest; for instance, into kinesin motors. Kinesin motors were visualized after intracellular microinjection of QDs into HeLa cells and allowed the measurement of cell velocity, processivity and force required to carry a QD [18]. Another means of bypassing endocytotic vesicles is by using cationic lipids to enter cells. This technique has been previously used to transport nucleic acids into cells during transfection [19]. It is hypothesized that the mechanism of entry is similar to that of nucleic acids. Using this method, Voura et al. labeled cells with QDs by using cationic lipids to transport negatively charged QDs into cells [20]. Modifying the coat of the QD can also lead to easier access of the QD to the cytosol. For instance, QDs coated in polyethelene glycol and conjugated to localization sequence peptides were reportedly able to gain access to the nucleus and mitochondria [21]. In addition, peptide conjugates have been used successfully to get QDs to enter cells [22]. Peptide transduction domains are positively charged peptide sequences that bind anionic molecules to assist in transport into cells [23]. One example of a peptide transduction domain that can be conjugated to QDs to facilitate internalization is TAT, a peptide that was first isolated from the HIV-1 virus. Using TAT-conjugated QDs, de la Fuente et al. were able to demonstrate entry of the QD into the nucleus of human fibroblasts [23]. Other cell membrane permeability-enhancing agents that can lead to QD internalization include endosmolytic (endosome-disrupting) surface coatings using multivalent amines that become osmotically active when exposed to the low pH of the endosome, causing it to swell and leading to enhanced membrane permeability [24].

Since QDs were first introduced, their use in biologic experiments has become common and important insights in cell biology have been made. For instance, QDs were used for the first time to document the dynamics of receptor transport at the cell membrane level. QDs have also been used to deliver and monitor siRNA in cells [25].

In vivo imaging using QDs

Since QDs have desirable optical properties, it is natural to apply them to in vivo biological and preclinical investigations of cancer [26,27], lymphatic physiology [28–30], cell-tracking imaging [20,31] and neurological imaging [32,33]. From a practical standpoint, the in vivo real-time imaging of cancer, the lymphatics and cell tracking are the applications that can be most easily translated to the clinic. The ability to acquire images in real time is critical for this in vivo imaging. From a clinical viewpoint, the ability to image and perform procedures in real time is vital to the management of patients.

Cancer imaging with QDs

Cancer imaging requires high specificity and sensitivity, enabling the detection of small cancers. Real-time imaging is used to guide biopsy and treatment procedures. It may also be possible to determine the molecular signature of a cancer using QDs by labeling or detecting receptors’ enzymes and angiogenesis factors [2,34]. Although nontargeted QDs are still occasionally used [35], most QD formulations are now conjugated to targeting ligands to provide molecularspecific information. Targeting and internalization of the conjugated QD leads to accumulation of the agent within the targeted cell.

The first report of in vivo cancer imaging using QDs was made by Akerman et al. They coated QDs with three different peptides that preferentially bound to endothelial cells in the blood and lymphatic vessels, as well as tumor cells. They then injected these peptide QDs into tumor-bearing mice. Based on the ex vivo histological results with fluorescence microscopy, they demonstrated that peptide-coated QDs specifically accumulated within the target tissues, such as cancer [36]. They also reported that polyethelene glycol coating reduced nonspecific accumulations in the reticuloendothelial system. More recently, in vivo targeted cancer imaging probes using peptide-coated QDs have been reported by Cai et al. [26]. QDs were labeled with arginine–glycine–aspartic acid, which binds to integrin αvβ3. Integrin αvβ3 plays a key role in tumor angiogenesis and metastasis; thus, it is significantly upregulated in some invasive tumor cells but not in normal tissue. When arginine– glycine–aspartic acid-labeled QDs were injected into mice with tumors that had high expression of integrin αvβ3 (i.e., U87MG cell line), tumor nodules were clearly depicted by QD fluorescence with a high tumor-to-background ratio at 6 h after injection, while unlabeled QDs failed to visualize tumor nodules.

Another class of targeting agents that can specifically deliver QDs into tumor tissue are monoclonal antibodies. Gao et al. reported detecting prostate-specific membrane antigen in a prostate cancer model in mice using a QD conjugated to an antiprostate-specific membrane antigen antibody [27]. When this QD-conjugated antibody was intravenously injected into nude mice bearing subcutaneous xenografts (C4–2 cell line), the antibody–QD conjugate localized to the tumor. After this pioneering work, the combination of QDs and monoclonal antibodies have been successfully applied to other targets, such as the EGFR [37], α-fetoprotein [38] and HER2/neu [39].

Lymphatic imaging with QDs

Lymphatic imaging, especially sentinel lymph node mapping, is one of the most promising medical applications for real-time optical imaging. The sentinel lymph node is defined as the first lymph node or lymph node group to receive lymphatic drainage from a primary cancer site and is often superficial to the skin in the case of breast cancer or melanoma [40]. The sentinel node is typically the first node to demonstrate lymphatic metastases. Conversely, if there are no cancer foci in the sentinel lymph node, the risk of developing lymphatic metastases elsewhere is low and the patient can avoid potentially debilitating surgery. Sentinel lymph node mapping can be performed with a variety of imaging methods, including blue dye injection, nuclear lymphoscintigraphy, computed tomography and MRI [41]. However, each of these imaging methods has their limitation: the blue-dye injection method is less sensitive to subsurface tissue and has almost no tissue penetration, lymphoscintigraphy has low spatial resolution and requires exposure to radioactivity, and computed tomography/MRI requires a bulky imaging machine that prevents use during surgery. Advantages of optical imaging are that it can be performed without ionizing radiation with sufficient spatial resolution in real time during surgery. Several nanosized molecules, such as immunoglobulin-conjugates [42] and dendrimerconjugates [31,43–45], are employed for in vivo lymphatic imaging in animals because macromolecules larger than approximately 6–10 nm preferentially enter the lymphatic capillaries, and are retained throughout the length of the afferent vessel, resulting in efficient labeling of the vessels and the sentinel lymph nodes [43,44]. Since QDs are already nearly the ideal size for a lymphatic agent, and are very bright, they are very attractive for sentinel lymph node mapping.

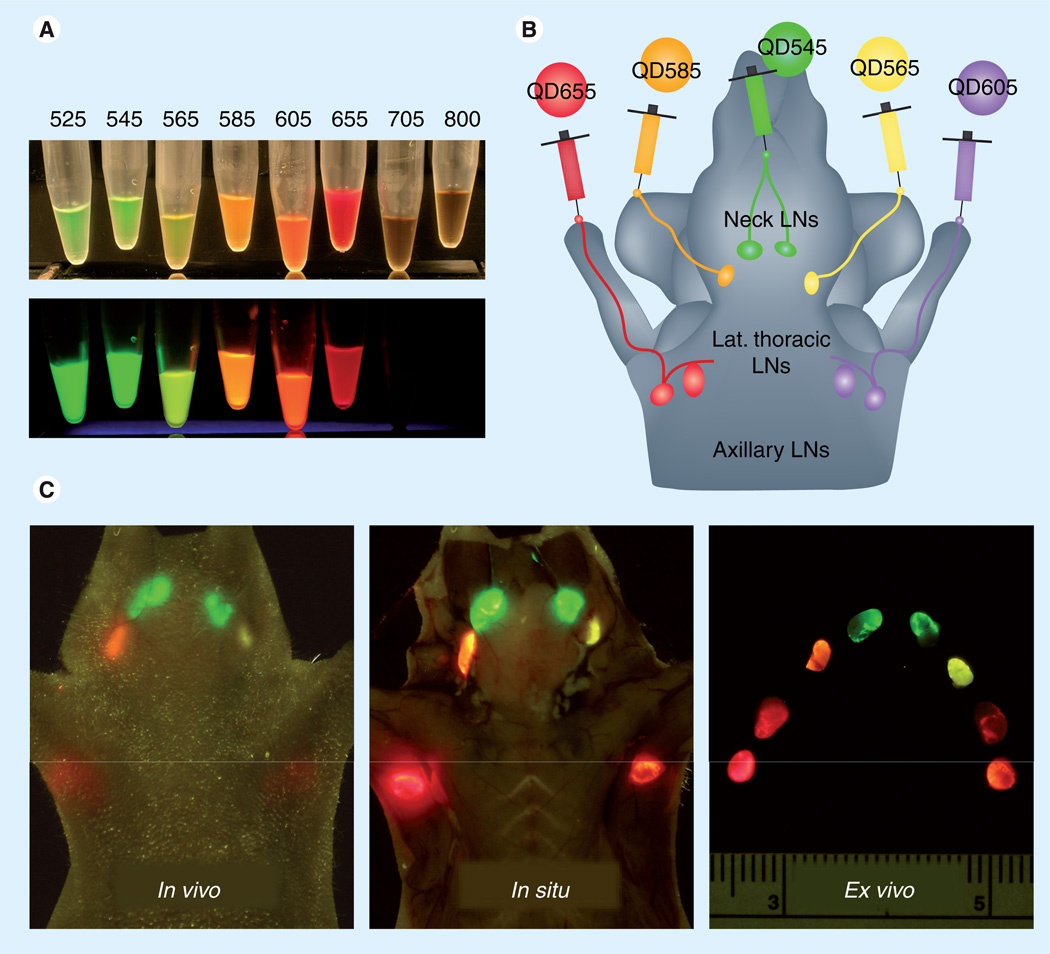

Quantum dot lymph node mapping was first reported by Kim et al. They intradermally injected a NIR QD into the paw of a mouse or thigh of a pig. After injection, sentinel lymph nodes were clearly depicted using QDs in both mice and pigs [29]. Following this first report, the capability of QD sentinel lymph-node mapping was demonstrated in other organs, such as the lung, esophagus and the GI tract [46–48], or with peritumoral/intratumoral injections [28,49]. In these studies, only one type of QD was administrated to map the entire lymphatic system. However, lymphatic systems are very complicated and each lymph node can receive lymphatic fluid from multiple afferent lymphatic channels [42,50]. Moreover, the direction of flow within lymphatic networks is often unpredictable, especially in areas with well-developed ‘watershed’ or overlapping lymphatics. Therefore, to map the entire lymphatic system thoroughly, multiple QDs with different colors are needed. Here, the narrow emission peak of QDs becomes invaluable as it is possible to use multiple different colors in the same mouse at the same time. Kobayashi et al. demonstrated this using five different QDs injected into different sites in anesthetized mice. Using standard spectral unmixing methods [51], five lymphatic basins were successfully depicted by their distinct colors [30]. This multicolor approach to lymphatic imaging may help elucidate the complex human lymphatic system, which has hitherto been difficult to image.

Cell tracking with QDs

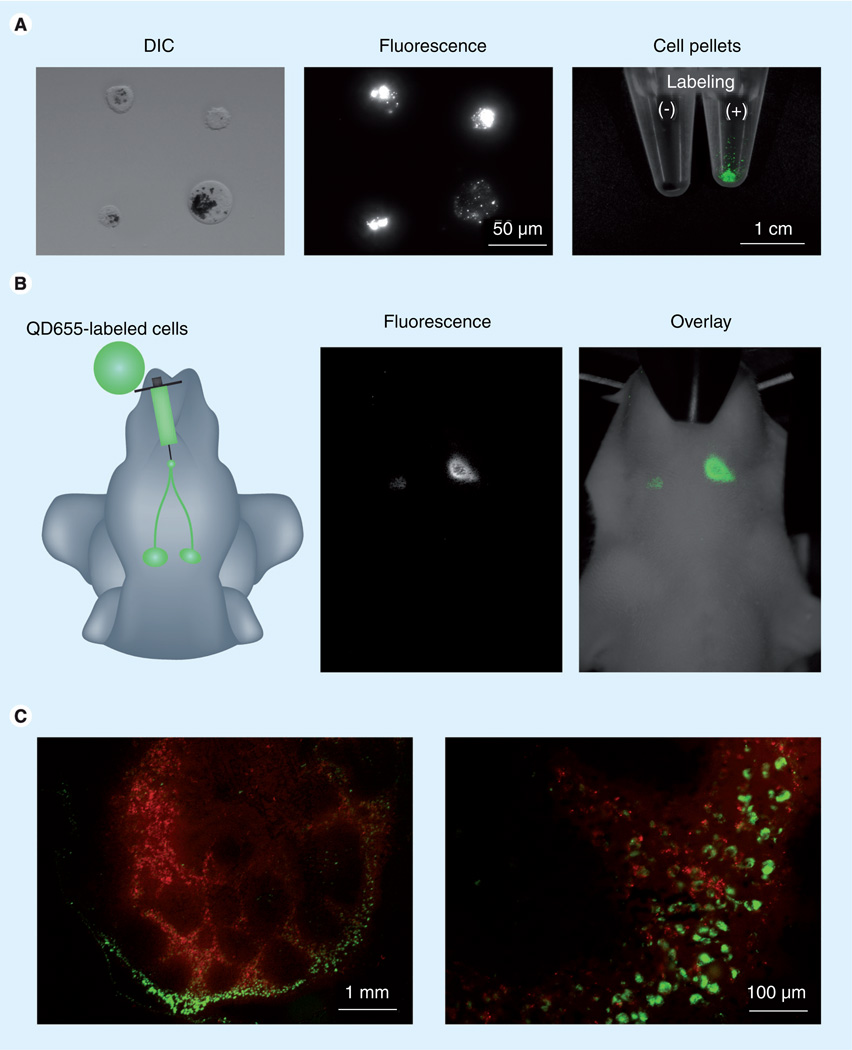

The behavior and fate of injected cells is of great importance in the understanding of migration or metastasis of cancer cells and cell-based therapies, including bone marrow or stem cell transplants. The inability to determine when and where cells migrate and settle or how many viable injected cells are present in the target lesion has been a historical limitation of this approach. Therefore, there is a need for methods of tracking injected stem/progenitor [52] or cancer cells [31]. Currently, there are two principle nanoparticle-based imaging methods for cell tracking; superparamagnetic iron oxide crystals with MRI [53] and QDs with optical imaging. The stability of QDs allows them to be used to follow cells over considerable periods of time. For example, Voura et al. labeled melanoma cells with QDs and injected them into a mouse through a tail vein. After 6 h, labeled tumor cell extravasations were depicted in the ex vivo lung specimens with fluorescence emission-scanning microscopy [20]. Kobayashi et al. injected QD-labeled melanoma cells into the chin of a mouse, and visualized in vivo cancer cell migration to lymph nodes (Figure 2). They also demonstrated that even a single cancer cell could be depicted with QDs [31]. Successful cell tracking with QDs has been reported in experimental animals in controlled circumstances [20,31,54,55]. However, there are at least three major limitations for wider clinical use in humans:

-

▪

Actively dividing cells will decrease rapidly in signal owing to dilution of the agent in progeny cells;

-

▪

The tracked cell may become engulfed by macrophages and, thus, there may be ambiguity with regard to the location of the label;

-

▪

As QDs are metabolized they could become toxic for labeled cells [56].

Figure 2. In vivo cancer cell tracking within the lymphatic system.

(A) B16 CXCR4 melanoma cells labeled with QD655. (B) Cancer cell migration to neck lymph nodes can be tracked by bright QD fluorescence with in vivo optical imaging. (C) Even after tissue processing, QD-labeled cancer cells (green) can be tracked by its bright and stable fluorescence of QDs.

DIC: Differential interference contrast; QD: Quantum dot.

Therefore, currently, cell tracking is most useful in short-term applications when cells are injected into animals for research purposes.

In vivo real-time imaging

Movies and television programs run at 24 frames per second. In order to watch the real-time image and perform image-guided intervention without significant stress, real-time imaging needs to have more than ten frames per second. Therefore, to achieve real-time imaging, the fluorescence signal should be strong enough to minimize the exposure time for each frame to less than 100 ms as well as suppress the background autofluorescence. Therefore, the brightness and long Stokes shift of QDs are favorable for in vivo real-time imaging applications [57]. Despite their favorable imaging features, translating the research experience with QD imaging in small animals into humans will be challenging. Although QDs are bright, in our experience using a reflectal fluorescence imager, their depth penetration is still limited to around 1 cm even with NIR QDs [29,30]. This limits clinical applications to those at or just below the epithelial surface (including internal organs such as the bladder and colon). Consequently, the use of QD imaging in conjunction with surgical and endoscopic procedures is a promising avenue for development. Frangioni et al. and several other investigators have designed an intraoperative NIR fluorescence imaging system for use with large animals, including humans [58]. This system is composed of three excitation lights; one white light and two different NIR excitation lights encompassing a large (15 × 11.3 cm) field of view. The camera simultaneously acquires color video and two NIR fluorescence channels (700 and 800 nm), and these images can be displayed separately or merged in real time (30 images per second). With this system, they have successfully visualized sentinel lymph nodes and defined the anatomy of fine structures during large animal surgery and during limited human surgery with a variety of optical agents [46–49,58–60].

Near-infrared-emitted QDs have deeper penetration of tissue; however, NIR light is invisible to the human eye. Thus, specially designed optical imaging systems are required. However, visible-range QDs can be detected with the naked eye. Moreover, owing to their narrow emission spectra, several QDs in the visible spectrum can be resolved simultaneously (Figure 3, Supplementary Video 1; see online at www.futuremedicine.com/toc/nnm/5/5) [50] using a simple blue-cut filter and the naked eye, without a complex camera system or elaborate image processing.

Figure 3. Real-time, multicolor quantum dots in vivo lymphatic imaging.

(A) Real colors of QDs’ fluorescence excited by UV. Fluorescence of visible-range QDs can be identified and distinguished by their distinct colors. (B) Schematic illustration of injection sites of a mouse. (C) Five different lymphatic basins are depicted by the distinct colors corresponding to the injected QDs in real time (also see Supplementary Video 1).

Lat.: Lateral; LN: Lymph node; QD: Quantum dot.

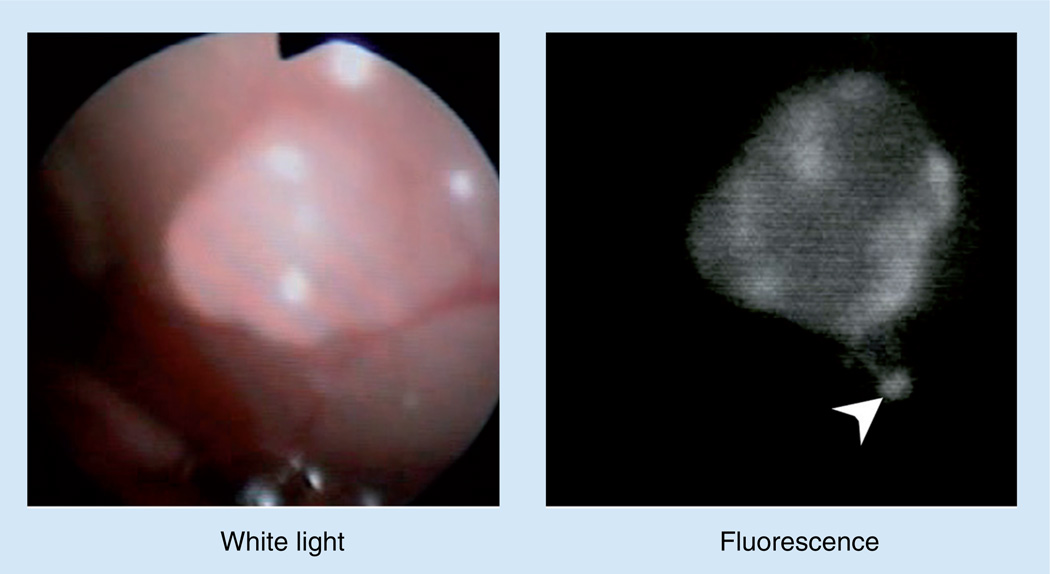

Endoscopy can be readily adapted to permit QD imaging since conventional endoscopy is already a ‘real-time optical imaging instrument’; therefore, with minor refitting, endoscopes can be converted for fluorescence imaging – pre-clinical testing of fluorescence endoscopes has been reported [61–63]. Kobayashi et al. have developed a fluorescence endoscopic system that is suitable for small rodents and potentially for human pediatric applications. In vivo imaging in mice was demonstrated using a wide range of excitation and emission filters on a commercially available clinical endoscopic system (EVIS ExERA-II CLV-180, Olympus Corp., Tokyo, Japan). In one application of this system, tiny peritoneal implants, not visible to the naked eye, were detected with real-time endoscopy in a mouse model of ovarian cancer after incubation with QDs and other optical agents (Figure 4, Supplementary Video 2) [64–66]. Further endoscopic biopsy of the detected cancers was performed using fluorescence targeting for guidance [64].

Figure 4. Real-time in vivo cancer imaging with quantum dots.

Small disseminated cancer foci are endoscopically detected by quantum dot fluorescence (arrow head). Also see Supplementary Video 2.

Nanoparticles beyond QDs

Real-time imaging using QDs has made great strides in the visualization of tumors and the lymphatic system. However, an inherent limitation of the current generation of QDs is that the excitation light also induces autofluorescence (background signal) from intrinsic fluorophores in the normal tissue, lowering the target-to-background ratio. Generally, autofluorescence competes with the exogenous fluorophore in the display of the pathology. Therefore, several techniques have been developed to reduce or eliminate autofluorescence. Spectral unmixing removes the presumed autofluorescence signal from the presumed targeted fluorescence signal [51]. However, because multiple images must be obtained throughout the spectrum, spectral unmixing requires long acquisition times and manual postprocessing, which makes real-time display very difficult. Moreover, there is inherent subjectivity in determining the background ‘autofluorescence pattern’ to be ‘unmixed’ from the targeted fluorescence. Two-photon excitation is another way to eliminate autofluorescence. However, in vivo two-photon imaging has been performed at a microscopic scale and it is difficult to visualize deep and wide objects in real time [67].

Several new technologies, based on nanocrystals related to QDs, are promising alternatives. For instance, upconverting nanoparticles (UCNPs) are unique nanocrystals that emit light at shorter wavelengths than the excitation light in the NIR. This is achieved by converting energy of two photons serially absorbed in the UCNP [68–72]. Conventional fluorophores, including QDs, typically emit light at longer wavelengths than the excitation light. However, the shorter wavelength excitation light also excites autofluorescence, whereas with UCNPs, the longer wavelength excitation light (in the NIR) avoids exciting autofluorescence, while the shorter wavelength emission light is easily detectable with conventional cameras. Moreover, by changing the composition of the doping metals, UCNPs can be synthesized to emit at a variety of specific wavelengths [73]. After subcutaneous injection of UCNPs in mice, Kobayashi et al. successfully performed optical lymphangiography. In this experiment two kinds of UCNPs (Sunstone Biosciences, Inc., PA, USA) were injected into the chin of anesthetized mice, one emitting in the visible range (peak 550 nm) and the other in the NIR range (peak 800 nm). A 980-nm laser was used to excite the UCNPs. In all mice, superficial neck lymph nodes were successfully depicted with no background signal in the visible range or NIR range. Furthermore, with serial injections of the visible- and NIR-range UCNPs, simultaneous lymphatic imaging was achieved in two colors without background signal [74]. UCNPs still have some limitations, including low quantum yield and absorptivity.

Another approach to reducing autofluorescence is to use bioluminescence (BLI). In BLI, cells must first be transfected with the luciferase gene so that when they are exposed later to the substrate of luciferin or a related compound, light is emitted owing to a photochemical reaction by consuming oxygen. Since there is no excitation light, the background signal is reduced and target to background ratios are high, even though the light output from BLI is low. Besides requiring prior cell transfection, another disadvantage of BLI is that the light output is generally too weak and at too short a wavelength for real-time imaging. Thus, BLI is unlikely to be a clinically translatable, real-time imaging technique.

Another strategy to eliminate autofluorescence is to combine technologies in the form of bioluminescence resonance energy transfer QDs (BRET-QD) [75]. The BRET-QD is self-illuminating and employs the substrate, coelenterazine, which reacts with luciferase conjugated on the BRET-QD (Figure 5A). The bioluminescent radiationless energy transfer excites the NIR QD, without inducing autofluorescence. So et al. applied this BRET-QD particle to cancer cell tracking. They conjugated a polycationic peptide to a BRET-QD and labeled C6 glioma cells with the conjugates. After demonstrating successful labeling of the cells in vitro, they injected the labeled cells into nude mice through the tail vein. Migration of cancer cells into lungs was clearly visualized [75]. In our laboratory, BRET-QD655 (QD655 in its core, Zymera, Inc., CA, USA) was injected at various sites (chin, ear, forepaws and hind paws) of anesthetized mice. After the BRET-QD injection, coelenterazine was intravenously injected and imaging was performed without excitation light. In all mice, the sentinel lymph nodes in each lymphatic basin were clearly visualized with no background signals (Figure 5B). Sufficient signal for imaging was present for at least 30 min after coelenterazine injection. Moreover, by changing the QDs within the BRET-QD conjugate, it is possible to alter the emission wavelength, enabling multicolor in vivo lymphatic imaging with BRET-QDs [75].

Figure 5. In vivo lymphatic images with the bioluminescence resonance energy transfer quantum-dot nanoparticle.

(A) Schematic illustration of a BRET-QD nanoparticle (reproduced with permission from Nature Publishing Group, see [75]). (B) Sentinel lymph node (left axillary) can be detected with no background signal (autofluorescence).

BRET: Bioluminescence resonance energy transfer; LN: Lymph node; Lt: Left; QD: Quantum dot; Rt: Right.

Both UCNPs and BRET-QDs markedly reduce autofluorescence, which allows rapid real-time imaging without extensive postprocessing of the images. Theoretically, these particles are suitable for a broad range of imaging applications. A limitation of both particles is that the intensity of the emission light is less than typical QDs, resulting in longer exposure times and reduced frame rates. However, with further improvements in both the formulation of the nanoparticles and increased sensitivity of cameras, these new nanoparicles have potential for in vivo real-time imaging.

Conclusion

Real-time imaging, using fluorescently enhancing QDs and related nanocrystals, is already being exploited for preclinical research. QDs, in particular, have the desirable features of photostability and high-intensity emissions, which enable continuous real-time imaging. Newer nanocrystal-based constructs, such as UCNPs and BRET-QDs, build on the success of QDs by reducing or eliminating autofluorescence. Despite their advantages, these fluorescent nanocrystals also have limitations. Their relatively large size leads to increased circulation times and possible nonspecific uptake by the reticuloendothelial system. Their composition, often containing heavy metals, leads to concern over toxicity in vivo. Topological application of QDs, such as for lymphatic imaging, can minimize the administration dose. Thus, this represents a very feasible application for the clinical practice. The ultimate use of these nanocrystals in the laboratory and in the clinic awaits further exploration of their risks and benefits.

Future perspective

Although QDs have already had considerable impact in laboratory experiments, no clinical investigations of real-time QD optical imaging have been performed. Instead, more widely available organic dyes, such as indocyanine green and methylene blue, have been used in the clinical environment [76,77]. These fluorophores have been selected, mainly owing to their long-term safety record in humans; not for their optical properties. The future of QDs and related nanocrystals in humans rests on the ability to demonstrate that they are nontoxic and are eliminated rapidly and intact from the body. For instance, if QDs can be administered at very low doses and are eliminated rapidly without significant metabolism, then the heavy metal cores (CdSe and CdTe), may not interfere with their use. It may be possible to design QDs and related nanocrystals so as to reduce potential toxicity. For instance, ultra-small QDs (<5.5 nm) have recently been developed that can be excreted from the kidney, even when coated with targeting peptides [78,79]. Moreover, surface modification can alter the biodistribution and clearance from the body [80,81]. Therefore, in the near future, the concerns surrounding QDs and related nanocrystals may become less troubling and the full potential of these unique structures for human disease can be realized more fully.

Supplementary Material

Executive summary.

Introduction

-

▪

The advantages of optical imaging are high spatial resolution, relatively low cost, portability, no radiation exposure, ability to multiplex several colors at the same time and real-time display.

-

▪

Quantum dots (QDs) have desirable optical properties for real-time observation, including very high brightness, photostability and multicolor capability.

In vitro imaging using QDs

-

▪

Photostability and brightness of QDs enables real-time observation of the dynamic changes of transmembrane receptors or other structural cell surface proteins in vitro.

In vivo imaging using QDs

-

▪Cancer imaging with QDs:

-

–QDs conjugated to a specific targeting ligand or monoclonal antibody can provide molecular-specific information on cancers as well as accelerate QD accumulation into targeted tumors.

-

–

-

▪Lymphatic imaging with QDs:

-

–Lymphatic imaging, especially sentinel lymph node mapping, is one of the most promising medical applications for real-time optical imaging;

-

–QDs are ideal lymphatic tracers for sentinel lymph node mapping owing to their size (6–10 nm) and brightness;

-

–Multicolor lymphatic imaging can be obtained with the simultaneous use of multiple QDs.

-

–

-

▪Cell tracking with QDs:

-

–Photo- and bio-stability as well as the brightness of QDs allows efficient labeling and long-term tracking of cells in vitro and in vivo.

-

–

-

▪In vivo real-time imaging:

-

–Since optical imaging is limited to the first 1 cm or more of tissue depth, it is best combined with surgery or endoscopy. Specially designed intraoperative optical imaging and endoscopic systems have been developed;

-

–Multiplexed visible-range QDs have the potential for real-time multicolor imaging with the naked eye.

-

–

-

▪Beyond QDs:

-

–Two unique nanoparticles, upconverting nanoparticles and bioluminescence resonance energy transfer QDs, have great potential for in vivo real-time imaging with higher signal-to-background ratio by eliminating background signals.

-

–

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research and the Clinical Research Training Program, a public–private partnership supported jointly by the NIH and Pfizer Inc. (via a grant to the Foundation for NIH from Pfizer Inc.).

Footnotes

Financial & competing interests disclosure

The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

Bibliography

Papers of special note have been highlighted as:

▪ of interest

▪▪ of considerable interest

- 1.Hoffman RM. The multiple uses of fluorescent proteins to visualize cancer in vivo. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2005;5(10):796–806. doi: 10.1038/nrc1717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weissleder R, Pittet MJ. Imaging in the era of molecular oncology. Nature. 2008;452(7187):580–589. doi: 10.1038/nature06917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kosaka N, Ogawa M, Choyke PL, Kobayashi H. Clinical implications of near-infrared fluorescence imaging in cancer. Future Oncol. 2009;5(9):1501–1511. doi: 10.2217/fon.09.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kitai T, Inomoto T, Miwa M, Shikayama T. Fluorescence navigation with indocyanine green for detecting sentinel lymph nodes in breast cancer. Breast Cancer. 2005;12(3):211–215. doi: 10.2325/jbcs.12.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ntziachristos V, Yodh AG, Schnall M, Chance B. Concurrent MRI and diffuse optical tomography of breast after indocyanine green enhancement. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97(6):2767–2772. doi: 10.1073/pnas.040570597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kobayashi H, Ogawa M, Alford R, Choyke PL, Urano Y. New strategies for fluorescent probe design in medical diagnostic imaging. Chem. Rev. 2010;110(5):2620–2640. doi: 10.1021/cr900263j. ▪ Excellent review of fluorescent probe design in medical diagnostic imaging.

- 7.Michalet X, Pinaud FF, Bentolila LA, et al. Quantum dots for live cells in vivo imaging, and diagnostics. Science. 2005;307(5709):538–544. doi: 10.1126/science.1104274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang H, Yee D, Wang C. Quantum dots for cancer diagnosis and therapy: biological and clinical perspectives. Nanomedicine (Lond.) 2008;3(1):83–91. doi: 10.2217/17435889.3.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reiss P, Protière M, Li L. Core/shell semiconductor nanocrystals. Small. 2009;5(2):154–168. doi: 10.1002/smll.200800841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jaiswal JK, Mattoussi H, Mauro JM, Simon SM. Long-term multiple color imaging of live cells using quantum dot bioconjugates. Nat. Biotechnol. 2003;21(1):47–51. doi: 10.1038/nbt767. ▪▪ Original work for the in vitro cell labeling with quantum dots (QDs).

- 11.Wu X, Liu H, Liu J, et al. Immunofluorescent labeling of cancer marker HER2 and other cellular targets with semiconductor quantum dots. Nat. Biotechnol. 2003;21(1):41–46. doi: 10.1038/nbt764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lidke DS, Nagy P, Heintzmann R, et al. Quantum dot ligands provide new insights into ERBB/HER receptor-mediated signal transduction. Nat. Biotechnol. 2004;22(2):198–203. doi: 10.1038/nbt929. ▪▪ Original work for the in vitro real-time imaging of EGF receptor dynamics with the EGF–QD complex.

- 13.Young SH, Rozengurt E. Qdot nanocrystal conjugates conjugated to bombesin or Ang II label the cognate G protein-coupled receptor in living cells. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2006;290(3):C728–C732. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00310.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cui B, Wu C, Chen L, et al. One at a time, live tracking of NGF axonal transport using quantum dots. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104(34):13666–13671. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706192104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dahan M, Levi S, Luccardini C, Rostaing P, Riveau B, Triller A. Diffusion dynamics of glycine receptors revealed by single-quantum dot tracking. Science. 2003;302(5644):442–445. doi: 10.1126/science.1088525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen H, Titushkin I, Stroscio M, Cho M. Altered membrane dynamics of quantum dot-conjugated integrins during osteogenic differentiation of human bone marrow derived progenitor cells. Biophys. J. 2007;92(4):1399–1408. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.094896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heuff RF, Swift JL, Cramb DT. Fluorescence correlation spectroscopy using quantum dots: advances, challenges and opportunities. Phys. Chem. 2007;9(16):1870–1880. doi: 10.1039/b617115j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Courty S, Luccardini C, Bellaiche Y, Cappello G, Dahan M. Tracking individual kinesin motors in living cells using single quantum-dot imaging. Nano. Lett. 2006;6(7):1491–1495. doi: 10.1021/nl060921t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clark PR, Hersh EM. Cationic lipid-mediated gene transfer: current concepts. Curr. Opin. Mol. Ther. 1999;1(2):158–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Voura EB, Jaiswal JK, Mattoussi H, Simon SM. Tracking metastatic tumor cell extravasation with quantum dot nanocrystals and fluorescence emission-scanning microscopy. Nat. Med. 2004;10(9):993–998. doi: 10.1038/nm1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Derfus A, Chan W, Bhatia S. Intracellular delivery of quantum dots for live cell labeling and organelle tracking. Adv. Mater. 2004;16(12):961–966. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Delehanty JB, Medintz IL, Pons T, Brunel FM, Dawson PE, Mattoussi H. Self-assembled quantum dot–peptide bioconjugates for selective intracellular delivery. Bioconjug. Chem. 2006;17(4):920–927. doi: 10.1021/bc060044i. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhou M, Ghosh I. Quantum dots and peptides: a bright future together. Biopolymers. 2007;88(3):325–339. doi: 10.1002/bip.20655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Duan H, Nie S. Cell-penetrating quantum dots based on multivalent and endosome-disrupting surface coatings. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129(11):3333–3338. doi: 10.1021/ja068158s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yezhelyev MV, Qi L, O’Regan RM, Nie S, Gao X. Proton-sponge coated quantum dots for sirna delivery and intracellular imaging. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130(28):9006–9012. doi: 10.1021/ja800086u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cai W, Shin DW, Chen K, et al. Peptide-labeled near-infrared quantum dots for imaging tumor vasculature in living subjects. Nano Lett. 2006;6(4):669–676. doi: 10.1021/nl052405t. ▪▪ Original work on in vivo cancer targeting with peptide-coated QDs.

- 27. Gao X, Cui Y, Levenson RM, Chung LW, Nie S. In vivo cancer targeting and imaging with semiconductor quantum dots. Nat. Biotechnol. 2004;22(8):969–976. doi: 10.1038/nbt994. ▪▪ Original work on in vivo cancer targeting with monoclonal antibody-conjugated QDs.

- 28.Ballou B, Ernst LA, Andreko S, et al. Sentinel lymph node imaging using quantum dots in mouse tumor models. Bioconjug. Chem. 2007;18(2):389–396. doi: 10.1021/bc060261j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kim S, Lim YT, Soltesz EG, et al. Near-infrared fluorescent type II quantum dots for sentinel lymph node mapping. Nat. Biotechnol. 2004;22(1):93–97. doi: 10.1038/nbt920. ▪▪ Original work for the in vivo sentinel lymph node mapping with QDs.

- 30. Kobayashi H, Hama Y, Koyama Y, et al. Simultaneous multicolor imaging of five different lymphatic basins using quantum dots. Nano Lett. 2007;7(6):1711–1716. doi: 10.1021/nl0707003. ▪▪ Original work on in vivo multicolor lymphatic imaging with QDs.

- 31.Kobayashi H, Ogawa M, Kosaka N, Choyke PL, Urano Y. Multicolor imaging of lymphatic function with two nanomaterials: quantum dot-labeled cancer cells and dendrimer-based optical agents. Nanomedicine (Lond.) 2009;4(4):411–419. doi: 10.2217/nnm.09.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gao X, Chen J, Chen J, Wu B, Chen H, Jiang X. Quantum dots bearing lectin-functionalized nanoparticles as a platform for in vivo brain imaging. Bioconjug. Chem. 2008;19(11):2189–2195. doi: 10.1021/bc8002698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Khalessi AA, Liu CY, Apuzzo ML. Neurosurgery and quantum dots: part I – state of the art. Neurosurgery. 2009;64(6):1015–1027. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000347889.62762.3F. discussion 1027-1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McDonald DM, Choyke PL. Imaging of angiogenesis: from microscope to clinic. Nat. Med. 2003;9(6):713–725. doi: 10.1038/nm0603-713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morgan NY, English S, Chen W, et al. Real time in vivo non-invasive optical imaging using near-infrared fluorescent quantum dots. Acad. Radiol. 2005;12(3):313–323. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2004.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Akerman ME, Chan WC, Laakkonen P, Bhatia SN, Ruoslahti E. Nanocrystal targeting in vivo. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99(20):12617–12621. doi: 10.1073/pnas.152463399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nida DL, Rahman MS, Carlson KD, Richards-Kortum R, Follen M. Fluorescent nanocrystals for use in early cervical cancer detection. Gynecol. Oncol. 2005;99(3) Suppl. 1:S89, S94. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.07.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yu X, Chen L, Li K, et al. Immunofluorescence detection with quantum dot bioconjugates for hepatoma in vivo. J. Biomed. Opt. 2007;12(1) doi: 10.1117/1.2437744. 014008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tada H, Higuchi H, Wanatabe TM, Ohuchi N. In vivo real-time tracking of single quantum dots conjugated with monoclonal anti-Her2 antibody in tumors of mice. Cancer Res. 2007;67(3):1138–1144. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Morton DL, Wen DR, Wong JH, et al. Technical details of intraoperative lymphatic mapping for early stage melanoma. Arch. Surg. 1992;127(4):392–399. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1992.01420040034005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Barrett T, Choyke PL, Kobayashi H. Imaging of the lymphatic system: new horizons. Contrast Media Mol. Imaging. 2006;1(6):230–245. doi: 10.1002/cmmi.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hama Y, Koyama Y, Urano Y, Choyke PL, Kobayashi H. Two-color lymphatic mapping using Ig-conjugated near infrared optical probes. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2007;127(10):2351–2356. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kobayashi H, Kawamoto S, Bernardo M, Brechbiel MW, Knopp MV, Choyke PL. Delivery of gadolinium-labeled nanoparticles to the sentinel lymph node: comparison of the sentinel node visualization and estimations of intra-nodal gadolinium concentration by the magnetic resonance imaging. J. Control. Release. 2006;111(3):343–351. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2005.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kobayashi H, Kawamoto S, Sakai Y, et al. Lymphatic drainage imaging of breast cancer in mice by micro-magnetic resonance lymphangiography using a nano-size paramagnetic contrast agent. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96(9):703–708. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kobayashi H, Koyama Y, Barrett T, et al. Multimodal nanoprobes for radionuclide and five-color near-infrared optical lymphatic imaging. ACS Nano. 2007;1(4):258–264. doi: 10.1021/nn700062z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Parungo CP, Ohnishi S, Kim SW, et al. Intraoperative identification of esophageal sentinel lymph nodes with near-infrared fluorescence imaging. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2005;129(4):844–850. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2004.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Soltesz EG, Kim S, Kim SW, et al. Sentinel lymph node mapping of the gastrointestinal tract by using invisible light. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2006;13(3):386–396. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2006.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Soltesz EG, Kim S, Laurence RG, et al. Intraoperative sentinel lymph node mapping of the lung using near-infrared fluorescent quantum dots. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2005;79(1):269–277. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2004.06.055. discussion 269–277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tanaka E, Choi HS, Fujii H, Bawendi MG, Frangioni JV. Image-guided oncologic surgery using invisible light: completed pre-clinical development for sentinel lymph node mapping. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2006;13(12):1671–1681. doi: 10.1245/s10434-006-9194-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kosaka N, Ogawa M, Sato N, Choyke PL, Kobayashi H. In vivo real-time, multicolor, quantum dot lymphatic imaging. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2009;129(12):2818–2822. doi: 10.1038/jid.2009.161. ▪▪ Original work on in vivo real-time multicolor lymphatic imaging with QDs.

- 51.Levenson RM, Mansfield JR. Multispectral imaging in biology and medicine: slices of life. Cytometry A. 2006;69(8):748–758. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ferreira L, Karp JM, Nobre L, Langer R. New opportunities: the use of nanotechnologies to manipulate and track stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3(2):136–146. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Frank JA, Miller BR, Arbab AS, et al. Clinically applicable labeling of mammalian and stem cells by combining superparamagnetic iron oxides and transfection agents. Radiology. 2003;228(2):480–487. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2281020638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Noh YW, Lim YT, Chung BH. Noninvasive imaging of dendritic cell migration into lymph nodes using near-infrared fluorescent semiconductor nanocrystals. FASEB J. 2008;22(11):3908–3918. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-112896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sen D, Deerinck TJ, Ellisman MH, Parker I, Cahalan MD. Quantum dots for tracking dendritic cells and priming an immune response in vitro and in vivo. PLoS One. 2008;3(9):e3290. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Derfus A, Chan W, Bhatia S. Probing the cytotoxicity of semiconductor quantum dots. Nano. Lett. 2004;4(1):11–18. doi: 10.1021/nl0347334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Xing Y, Rao J. Quantum dot bioconjugates for in vitro diagnostics and in vivo imaging. Cancer Biomark. 2008;4(6):307–319. doi: 10.3233/cbm-2008-4603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Troyan SL, Kianzad V, Gibbs-Strauss SL, et al. The flare intraoperative near-infrared fluorescence imaging system: a first-in-human clinical trial in breast cancer sentinel lymph node mapping. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2009;16(10):2943–2952. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0594-2. ▪ Detailed description of a real-time intraoperative near-infrared optical imager.

- 59.Tanaka E, Choi HS, Humblet V, Ohnishi S, Laurence RG, Frangioni JV. Real-time intraoperative assessment of the extrahepatic bile ducts in rats and pigs using invisible near-infrared fluorescent light. Surgery. 2008;144(1):39–48. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2008.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tanaka E, Ohnishi S, Laurence RG, Choi HS, Humblet V, Frangioni JV. Real-time intraoperative ureteral guidance using invisible near-infrared fluorescence. J. Urol. 2007;178(5):2197–2202. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.06.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.El-Bayoumi E, Silvestri GA. Bronchoscopy for the diagnosis and staging of lung cancer. Semin. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2008;29(3):261–270. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1076746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ito S, Muguruma N, Kimura T, et al. Principle and clinical usefulness of the infrared fluorescence endoscopy. J. Med. Invest. 2006;53(1–2):1–8. doi: 10.2152/jmi.53.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Spiess PE, Grossman HB. Fluorescence cystoscopy: is it ready for use in routine clinical practice? Curr. Opin. Urol. 2006;16(5):372–376. doi: 10.1097/01.mou.0000240312.16324.9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ogawa M, Kosaka N, Choyke PL, Kobayashi H. H-type dimer formation of fluorophores: a mechanism for activatable in vivo optical molecular imaging. ACS Chem. Biol. 2009;4(7):535–546. doi: 10.1021/cb900089j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ogawa M, Kosaka N, Regino CAS, Mitsunaga M, Choyke PL, Kobayashi H. High sensitivity detection of cancer in vivo using a dual-controlled activation fluorescent imaging probe based on H-dimer formation and pH activation. Mol. BioSyst. 2010;6:888–893. doi: 10.1039/b917876g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Urano Y, Asanuma D, Hama Y, et al. Selective molecular imaging of viable cancer cells with pH-activatable fluorescence probes. Nat. Med. 2009;15(1):104–109. doi: 10.1038/nm.1854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Garaschuk O, Milos RI, Konnerth A. Targeted bulk-loading of fluorescent indicators for two-photon brain imaging in vivo. Nat. Protoc. 2006;1(1):380–386. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chatterjee DK, Rufaihah AJ, Zhang Y. Upconversion fluorescence imaging of cells and small animals using lanthanide doped nanocrystals. Biomaterials. 2008;29(7):937–943. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.10.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Nyk M, Kumar R, Ohulchanskyy TY, Bergey EJ, Prasad PN. High contrast in vitro and in vivo photoluminescence bioimaging using near infrared to near infrared up-conversion in Tm3+ and Yb3+ doped fluoride nanophosphors. Nano Lett. 2008;8(11):3834–3838. doi: 10.1021/nl802223f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zijlmans HJ, Bonnet J, Burton J, et al. Detection of cell and tissue surface antigens using up-converting phosphors: a new reporter technology. Anal. Biochem. 1999;267(1):30–36. doi: 10.1006/abio.1998.2965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bentolila LA, Ebenstein Y, Weiss S. Quantum dots for in vivo small-animal imaging. J. Nucl. Med. 2009;50(4):493–496. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.053561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Jiang S, Gnanasammandhan MK, Zhang Y. Optical imaging-guided cancer therapy with fluorescent nanoparticles. J. R. Soc. Interface. 2010;7(42):3–18. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2009.0243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wang F, Liu X. Upconversion multicolor fine-tuning: visible to near-infrared emission from lanthanide-doped nayf4 nanoparticles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130(17):5642–5643. doi: 10.1021/ja800868a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Kobayashi H, Kosaka N, Ogawa M, et al. In vivo multiple color lymphatic imaging using upconverting nanocrystals. J. Mater. Chem. 2009;19:6481–6484. ▪▪ Original work on in vivo multicolor lymphatic imaging with upconverting nanoparticles.

- 75. So MK, Xu C, Loening AM, Gambhir SS, Rao J. Self-illuminating quantum dot conjugates for in vivo imaging. Nat. Biotechnol. 2006;24(3):339–343. doi: 10.1038/nbt1188. ▪▪ Original work for the in vivo imaging with bioluminescence resonance energy transfer QD particles.

- 76.Matsui A, Tanaka E, Choi HS, et al. Real-time, near-infrared, fluorescence-guided identification of the ureters using methylene blue. Surgery. 2010;148(1):78–86. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2009.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sevick-Muraca EM, Sharma R, Rasmussen JC, et al. Imaging of lymph flow in breast cancer patients after microdose administration of a near-infrared fluorophore: feasibility study. Radiology. 2008;246(3):734–741. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2463070962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Choi HS, Liu W, Liu F, et al. Design considerations for tumour-targeted nanoparticles. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2010;5(1):42–47. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2009.314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Choi HS, Liu W, Misra P, et al. Renal clearance of quantum dots. Nat. Biotechnol. 2007;25(10):1165–1170. doi: 10.1038/nbt1340. ▪ Original work on renal clearance of QDs with small sizes.

- 80.Ballou B, Lagerholm BC, Ernst LA, Bruchez MP, Waggoner AS. Noninvasive imaging of quantum dots in mice. Bioconjug. Chem. 2004;15(1):79–86. doi: 10.1021/bc034153y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Choi HS, Ipe BI, Misra P, Lee JH, Bawendi MG, Frangioni JV. Tissue- and organ-selective biodistribution of NIR fluorescent quantum dots. Nano Lett. 2009;9(6):2354–2359. doi: 10.1021/nl900872r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.