Abstract

Mitochondrial ability of shaping Ca2+ signals has been demonstrated in a large number of cell types, but it is still debated in heart cells. Here, we take advantage of the molecular identification of the mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter (MCU) and of unique targeted Ca2+ probes to directly address this issue. We demonstrate that, during spontaneous Ca2+ pacing, Ca2+ peaks on the outer mitochondrial membrane (OMM) are much greater than in the cytoplasm because of a large number of Ca2+ hot spots generated on the OMM surface. Cytoplasmic Ca2+ peaks are reduced or enhanced by MCU overexpression and siRNA silencing, respectively; the opposite occurs within the mitochondrial matrix. Accordingly, the extent of contraction is reduced by overexpression of MCU and augmented by its down-regulation. Modulation of MCU levels does not affect the ATP content of the cardiomyocytes. Thus, in neonatal cardiac myocytes, mitochondria significantly contribute to buffering the amplitude of systolic Ca2+ rises.

Keywords: fluorescence energy transfer, calcium hot spots, GFP

Morphological evidence in adult cardiac myocytes demonstrates that a fraction of mitochondria is strategically closely apposed to sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) terminal cisternae where ryanodine receptors (RyR) are localized and Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release is activated (1). Given the close proximity of mitochondria to the SR cisternae, it has been suggested that mitochondria can transiently experience microdomains of high Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]) during systole; the concentrations reached in these microdomains are well above the mean values reached in the bulk cytoplasm and are sufficient to overcome the relatively low affinity of the uniporter for Ca2+ (see ref. 1 for a review). However, the high speed of systolic Ca2+ transients in heart cells may limit the capacity of mitochondria to take up significant amounts of Ca2+, and the involvement of the organelles on a beat-to-beat basis remains to be debated. The situation is somewhat simpler in neonatal cardiomyocytes: Although the organization of SR mitochondria is less ordinate than in adult cells, convincing evidence has been provided in support of the existence of beat-to-beat oscillations of intramitochondrial Ca2+ (2). The average peak rises in mitochondrial [Ca2+] are however quite small, approximately 50% smaller than in the cytoplasm (2). Thus, also in neonatal cardiomyocytes, whether and to what extent the capacity of the organelles to accumulate Ca2+ in their matrix depends on Ca2+ hot spots generated on their surface, their amplitudes, duration, and, most relevant from a physiological point of view, whether Ca2+ uptake by mitochondria can significantly contribute to cytoplasmic Ca2+ buffering is still unknown.

Here, we have addressed these problems by two unique approaches: (i) using a recently developed GFP-based Ca2+ indicator targeted to the outer mitochondrial membrane (OMM) and high-resolution image analysis (3), we have monitored the generation, during spontaneous Ca2+ oscillations in neonatal rat cardiomyocytes, of Ca2+ hotspots selectively on the OMM; (ii) taking advantage of the recent identification of the molecular identity of the mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter (MCU) (4, 5), we have genetically manipulated the level of MCU in mitochondria of cardiomyocytes.

The present data directly demonstrate the formation of Ca2+ hot spots on the OMM during systole. These hot spots can reach [Ca2+] values as high as 20–30 μM. Reducing MCU levels results in a significant increase in the amplitude of beat-to-beat cytoplasmic Ca2+ oscillations, whereas overexpression of MCU significantly reduces them.

Results

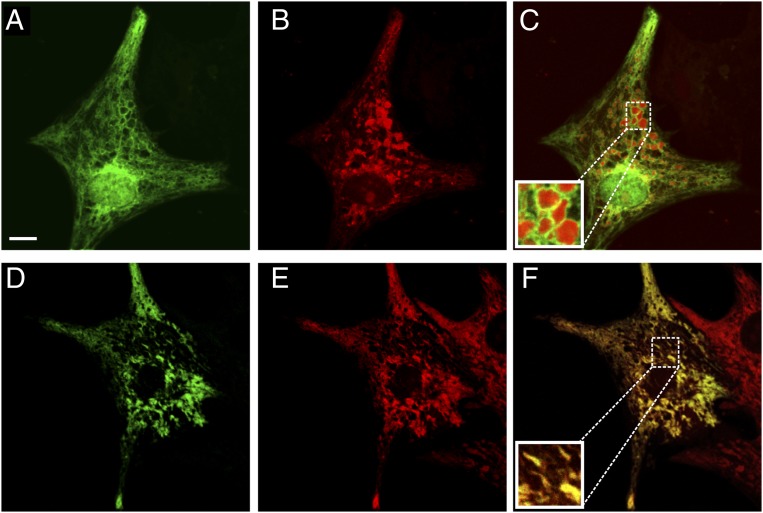

To address and monitor Ca2+ hot spots close to mitochondria in rat neonatal cardiac myocytes, we used two novel Ca2+ probes strategically localized on the cytoplasmic surface of the OMM (N33-D1cpv) or in the nucleus (H2B-D1cpv) (3), hereafter denominated (OMM)D1cpv and (nu)D1cpv. By this approach, bulk cytoplasmic (by monitoring the rapidly equilibrating nucleoplasm) and OMM Ca2+ changes can be evaluated at the same time, with no overlap between the two fluorescent signals. The two probes were expressed by transient transfection of neonatal rat ventricular cardiomyocytes and then imaged at the confocal microscope after 48 h. Fig. 1 A–C shows the distribution of (OMM)D1cpv and (nu)D1cpv, cotransfected in the same cell preparation (Fig. 1A), in comparison with MitoTracker Red (Fig. 1B); the latter probe localized in the mitochondrial matrix. (nu)D1cpv is clearly localized in the nucleus, as observed in other cell types (3). Although the overall gross distribution of (OMM)D1cpv and that of MitoTracker Red are similar (Fig. 1C), the different localization of the two probes is obvious in some favorable planes. In particular in the round mitochondria enlarged in Fig. 1C, Inset, it is clear that the (OMM)D1cpv signal (green) distributes as a ring around a red core (MitoTracker Red). For comparison, Fig. 1D shows the confocal image of a typical cell transfected with 4mtD3cpv, which is localized in the matrix, followed by staining with MitoTracker Red (Fig. 1E). The overlapping distribution of the two probes, in this latter case, is striking (Fig. 1F). Similar results were obtained when the transfected cells were fixed and immunolabeled for a bona fide matrix protein (hsp60).

Fig. 1.

Subcellular distribution of (OMM)D1cpv, (nu)D1cpv, and 4mtD3cpv in neonatal cardiac myocytes. (A–C) Cells were cotransfected with (OMM)D1cpv and (nu)D1cpv (A) and then stained with MitoTracker Red (B) and analyzed by confocal microscopy (Materials and Methods). C shows the merged image (yellow codes for colocalization). In C Inset, an enlarged detail of the figure. (D–F) As above, but cells were transfected with 4mtD3cpv. (D) 4mtD3cpv (green). (E) MitoTracker Red (red). (F) The merged image. (Scale bar: 10 μm.) In this and all subsequent experiments, typical traces or images are representative of at least 20 different cells in four or more independent cultures.

Cytoplasmic, Nucleoplasmic, and OMM Ca2+ Oscillations.

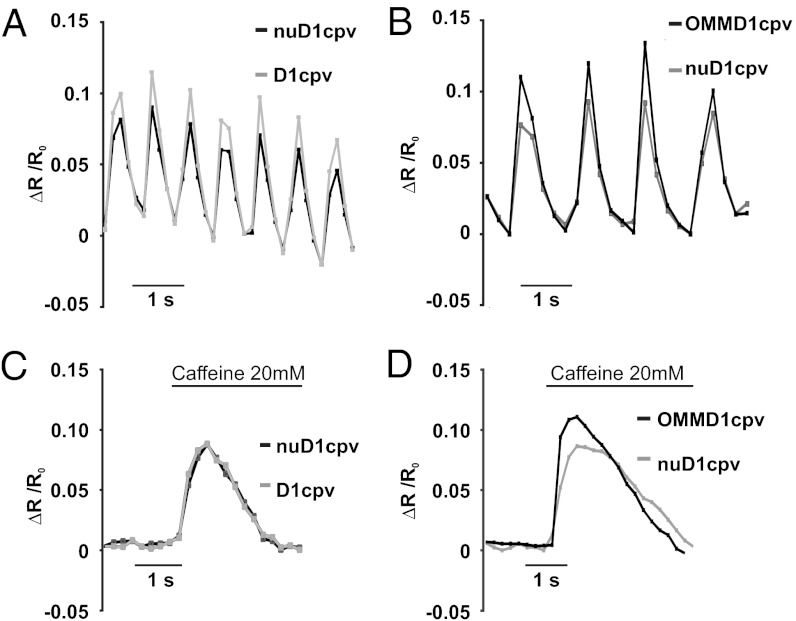

We next investigated the amplitude and frequency of Ca2+ oscillation in the nucleus and cytoplasm. Neonatal rat cardiomyocytes were cotransfected with an untargeted D1cpv and with (nu)D1cpv. A typical Ca2+ oscillations pattern is shown in Fig. 2A. The signals of nucleoplasm and cytoplasm (here expressed as ΔR/R0) oscillate in perfect synchrony for tens of seconds. Alternatively, we took advantage of the fact that, in some cells, D1cpv is localized both in cytoplasm and nucleoplasm (3), and the results were very similar. The comparison of the ΔR/R0 peak values of the cytosolic and nuclear signals occurring in the same cell (within the wide range of ΔR/R0 changes observed in different cells) highlighted a difference between the two compartments. The correlation between the ΔR/R0 peak changes of the cytoplasmic and nuclear signals in cells cotransfected with (nu)D1cpv and D1cpv (Fig. S1A) gave a fitting line whose slope was 1.44. In cells expressing the cytosolic probe mistargeted to the nucleoplasm, the ratio between cytoplasm and nucleus was 1.27. No difference between the cytoplasmic and nucleoplasmic signals (using either approach) was, however, observed upon high KCl (30 mM) depolarization.

Fig. 2.

Correlation among cytoplasmic, nuclear, and OMM Ca2+ signals during spontaneous oscillations and caffeine treatment. (A and C) Cells cotransfected with D1cpv and (nu)D1cpv. (B and D) Cells were cotransfected with (OMM)D1cpv and (nu)D1cpv. The behavior of typical cells during spontaneous beating (A and B) or caffeine treatment (C and D) is presented. The values of ΔR/R0 refer to the mean values of regions of interest (ROI) on the cytoplasm, nucleus, or OMM. In C and D, cells were perfused with extracellular solution (ES), without CaCl2 and 500 μM EGTA, instead. Sixty seconds after addition of EGTA, 20 mM caffeine was added where indicated.

We then compared the perimitochondrial and nuclear Ca2+ oscillations in cells cotransfected with (nu)D1cpv and (OMM)D1cpv. Also in this case, the Ca2+ oscillations were synchronous and the amplitudes of the average ΔR/R0 change were clearly different (Fig. 2B), those on the OMM being larger than those in the nucleus, on average 160.5 ± 14.2% of the nuclear ones (n = 31, P < 0.001, paired t test). Accordingly, the slope of the fitting line correlating the peak amplitude of the nucleoplasmic and OMM peaks is 1.6 (Fig. S1B).

Finally, we triggered Ca2+ mobilization from the SR with caffeine (added in Ca2+-free medium), a signal that takes approximately 600 ms to reach its peak. In this case, the average peak amplitude on the OMM was still larger than in the nucleoplasm (Fig. 2C) (170 ± 15.11% of the nuclear one; n = 23, P < 0.001, paired t test) and the slope correlating the nuclear and OMM peaks was 1.43 (Fig. S1C). On the contrary, the difference between the caffeine-induced peaks in nucleoplasm and cytoplasm (Fig. 2D) was not statistically significant (102 ± 12%) and the slope correlating the cytoplasmic and nucleoplasmic signals was 1.04 (Fig. S1D).

The difference in amplitude between nucleoplasm and OMM average Ca2+ peaks is not due to a different affinity for Ca2+ of the two probes for two reasons. First, we have shown that in HeLa cells, targeting of D1cpv to OMM or nucleus only modestly affect the Kd for Ca2+ of the two probes: if anything, the OMM-located probe has a slightly lower affinity for Ca2+ (and a smaller dynamic range) than that in the nucleoplasm (3). We confirmed this observation also in neonatal rat cardiomyocytes (data not shown). Second, the difference between the two compartments disappears if prolonged increases in Ca2+ are elicited, as upon KCl depolarization (data not shown).

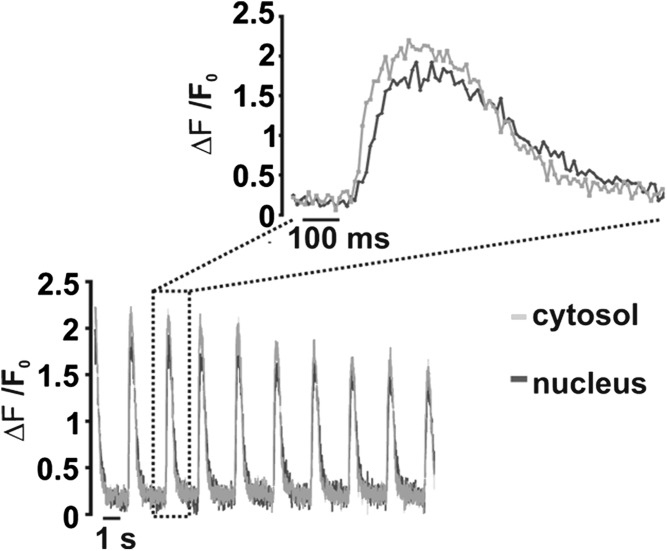

The kinetics of the Ca2+ increase in the two compartments were then compared in cells cotransfected with the nuclear- and OMM-targeted probes: on average (n = 18 cells), the two compartments reached their peak in ≤150 ms in 50% of cells, between 150 ms and 348 ms in 44.5% of cells and 584 ms in one cell. Given the time resolution of these experiments, times to peak shorter than 150 ms could not be resolved. To more precisely analyze the kinetics of nuclear and cytosolic Ca2+ increases, fast time resolution confocal analysis (one image every 20 ms) was thus used. Cardiomyocytes were loaded with the Ca2+ indicator Fluo-4 (that diffuses both in the cytosol and nucleus). Fig. 3 shows that a short delay (Fig. 3, Inset) in the onset of the nuclear signal increase (20 ± 7 ms, n = 35 cells from three different preparations) is observed. Similarly, a short delay was noticed between the peak reached in the nucleus compared with that in the cytoplasm (47 ± 19 ms, n = 35). The whole cycle of spontaneous oscillations took on average ∼600 ms in both compartments (Fig. 3). The peak amplitudes, as measured in the nucleus and cytoplasm (ΔF/F0) were 22 ± 12% (n = 35) larger in the cytoplasm than in the nucleus, similar to what we observed with the genetically encoded probes.

Fig. 3.

Correlation between cytoplasmic and nucleoplasmic spontaneous Ca2+ oscillations measured with fluo-4. Cells were loaded with fluo-4 and analyzed by confocal microscopy (Materials and Methods). Time resolution is 20 ms per image. Inset presents an enlargement of the signal change during the single oscillation indicated by the rectangle. The values of ΔF/F0 refer to the mean values of ROIs on the cytoplasm or nucleus, respectively. ΔF is the change of fluorescence intensity of each ROI at any time point, and F0 is the fluorescence intensity at time 0. The decay in the ΔF/F0 peaks with time is due to bleaching of the fluo-4 signal.

Generation of Ca2+ Hot Spots on the OMM.

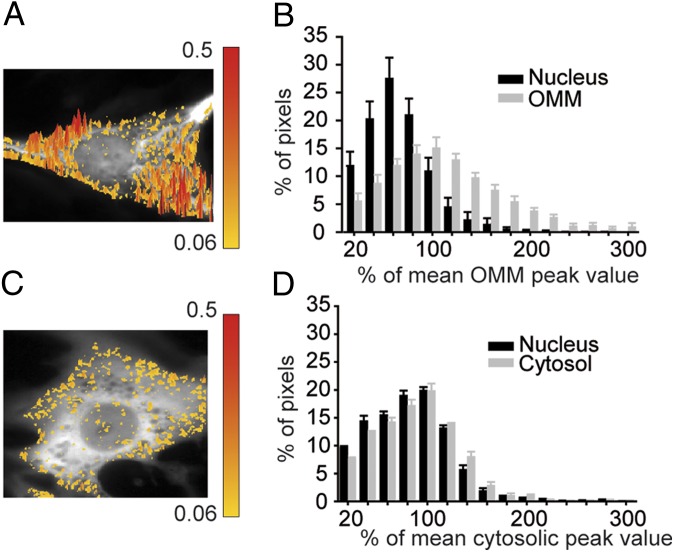

The differences between the average Ca2+ signal on the OMM and nucleoplasm reflect an incomplete equilibration between nucleoplasm and cytoplasm, but they may also depend on the existence of a large number of Ca2+ hot spots on the surface of mitochondria. To further confirm this conclusion and to obtain an estimate of the peak amplitude of the Ca2+ hot spots on the OMM, we carried out the pixel-by-pixel analysis described (3). A slight modification of the approach was necessary to take into account: (i) the high speed of the Ca2+ transients in these cells and (ii) the fact that the nucleoplasm on average reaches smaller peaks than the cytosol (Materials and Methods). Fig. 4A shows the 3D image of ΔRmax/R0 on the OMM and nucleoplasm of a typical cell. A threshold was established so that pixels with ΔRmax/R0 higher than 130% of the mean value of the OMM (taken as 100%) were yellow-to-red color-coded and superimposed to the mitochondrial YFP fluorescence (black and white). The colored pixels refer to all of the pixels exceeding the mean ΔRmax/R0 value on the OMM at the peak of a Ca2+ oscillation. The surface of mitochondria presents a large number of hot spots; as expected, almost no hot pixels were found in the nucleus. Fig. 4B shows the distribution of the pixel values (normalized to the mean OMM value of the same cell) on the OMM and nucleoplasm (average of 10 different cells). The percentage of pixels on the OMM exceeding 130% of the mean peak (again normalized as 100%) during the Ca2+ oscillations was 25.5 ± 6.3%. In terms of absolute Ca2+ values, we calculated that the [Ca2+] at the hot spots on the OMM can reach values as high as 20–30 μM.

Fig. 4.

Comparison of the Ca2+ hot spot distribution on the OMM, nucleoplasm, and cytoplasm at the peak of a Ca2+ oscillation. (A and B) Cells were cotransfected with (OMM)D1cpv and (nu)D1cpv. In A, the 3D image of ΔRmax/R0 on the OMM of a typical cell is presented. Pixels exceeding the mean ΔR/R0 peak amplitude of the OMM by 30% were color coded. On the right side, the scale bar and the corresponding ΔRmax/R0 values are shown. The hot pixel distribution refers to a single image taken at the peak of the Ca2+ oscillation. Although the amplitude of the mean ΔR/R0 peaks in the same cell were rather similar, a significant variability was noticed in the absolute mean peak values among different cells (Fig. 2). On the contrary, the percentage of hot pixels (when referred to the mean value of each cell) was quite reproducible. (B) The histograms represent the normalized ΔRmax/R0 pixel distribution (average from 10 different cells in three different experiments) at the peak of a Ca2+ oscillation. Pixel values were grouped in 20% intensity intervals. The mean ΔR/R0 on the OMM was taken as 100%. (C and D) Conditions as above, but in this case the cells were transfected with D1cpv localized both in the nucleus and cytoplasm. Similar results were obtained in cells cotransfected with D1cpv and (nuD1cpv). The mean ΔR/R0 in the cytoplasm was taken as 100%.

The same analysis was carried out in cells transfected with D1cpv. In this case, the colored pixels refer to all of the pixels with ΔRmax/R0 higher than 130% of the mean value of the cytoplasm at the peak of a Ca2+ oscillation. The number of hot pixels in the cytoplasm was clearly lower than on the OMM; on average (n = 10 cells) the cytoplasmic hot pixels were 8.7 ± 3.5%. As to the hot pixel amplitude, the difference between the cytosolic and the OMM hot spots is even bigger, because: (i) hot pixels on the OMM refer to the mean peak value of the OMM, that is 20–30% higher than the average peak of the cytosol; (ii) a substantial number of OMM hot pixels (approximately 7%) had peak values 2 or 3 times higher than the average, whereas the hot pixels observed in the cytoplasm with similar amplitudes were <0.8% (compare Fig. 4C with Fig. 4A). The small number of hot spots in the nucleoplasm probably reflect hot spots in the rim of cytoplasm above (or below) the nucleus.

Effect of MCU Level Manipulation on Cytoplasmic and Intramitochondrial Ca2+ Oscillations.

The question then arises as to the functional consequences of the hot spots on the OMM, in particular whether mitochondria contribute significantly to cytoplasmic Ca2+ buffering during each oscillation or whether Ca2+ uptake into the matrix is solely relevant for the control of intramitochondrial functions (e.g., the activation of the dehydrogenases). To test this hypothesis, we took advantage of the recent discovery of the molecular identity of MCU that allows to selectively modify the Ca2+ uptake capacity of mitochondria without interfering with bioenergetic properties or organelle structure (4, 5). Thus, MCU expression was either silenced with specific siRNAs or overexpressed. Silencing or overexpression efficiency was verified by Western blot (Figs. 5D and 6D). We also investigated whether MCU modulation affected the ATP level or the total content of Ca2+ mobilizable from the stores. Fig. S2 shows that the cytosolic ATP level, as measured by transfecting the cell with luciferase, was not modified by modulation in the MCU level. Similarly, the amount of stored Ca2+ (measured by monitoring the cytoplasmic Ca2+ increase caused by addition, in Ca2+-free medium, of the Ca2+ ionophore ionomycin) was indistinguishable in controls and in cells whose MCU was down-regulated or overexpressed (Fig. S3).

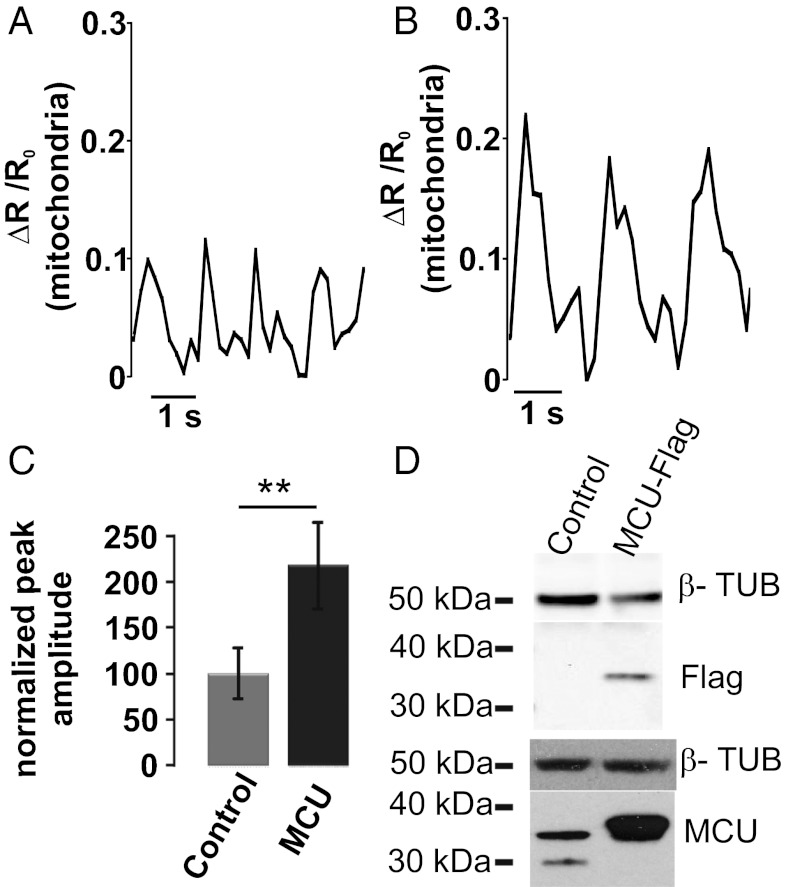

Fig. 5.

Effects on intramitochondrial Ca2+ oscillations of MCU overexpression. (A and B) Cells were cotransfected with 4mtD3cpv together with MCU encoding plasmid or the void vector. The typical kinetics of the intramitochondrial signal of a control cell (A) and of a cell overexpressing MCU (B) are presented. In C, the bars represent the average ΔR/R0 peaks values reached in the mitochondrial matrix of controls and MCU-overexpressing cells. **P < 0.01, Student t test (n = 80 cells). In D, representative Western blots of control and MCU-overexpressing cells are presented in comparison with the housekeeping protein tubulin. MCU was revealed with both an anti-tag (Upper) and a MCU-specific (Lower) antibody. The mean increase calculated by densitometric analysis is 254 ± 21.5% (from three different preparations).

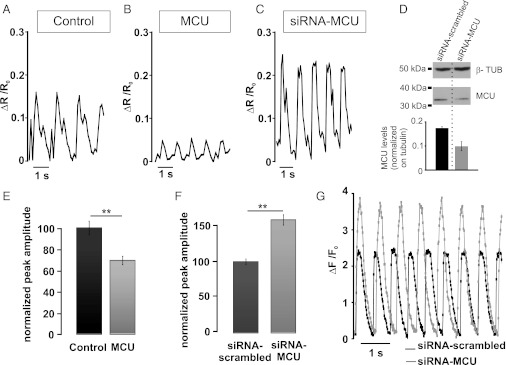

Fig. 6.

Effects on cytoplasmic Ca2+ oscillations of overexpressing or down-regulating MCU. (A and B) Cells were cotransfected with D1cpv together with MCU encoding plasmid or the void vector. The typical cytoplasmic Ca2+ oscillation in controls (A) or MCU-overexpressing cells (B) is presented. In E, the bars represent the average ΔR/R0 peaks reached in the cytoplasm of controls and MCU-overexpressing cells. **P < 0.001, Student t test (n = 80 cells). In C, D, and F, the cells were cotransfected with D1cpv- and MCU-specific siRNA. The typical pattern of the cytoplasmic Ca2+ oscillation in a cell expressing MCU-specific siRNA is presented. The cytoplasmic Ca2+ oscillations were not significantly affected by scrambled siRNA (data not shown and see F). The average ΔR/R0 peak amplitudes in cells transfected with MCU-specific or scrambled siRNA is presented in F. In D, the Western blot of control (siRNA-scrambled) and MCU-specific siRNA transfected cells (revealed with an anti-MCU antibody) is presented in comparison with the housekeeping protein tubulin. The bars represent the average decrease in MCU levels of three different experiments. The endogenous level of MCU was decreased by the siRNA in the whole cell population by approximately 35%. Given that the level of transfection in this cell type is approximately 40%, the efficacy of silencing in the transfected population can be calculated to be approximately 90%. In G, the cells were cotransfected with mitochondrial targeted RFP and with either scrambled or MCU-specific siRNA. The cells were loaded with fluo-4 and analyzed as described in Fig. 3. The assumption was made that cells expressing RFP also received the siRNA. The kinetic changes of ΔF/F0 of two typical cells are presented.

Matrix Ca2+ increases was then assessed [measured by cotransfecting 4mtD3cpv (3) and MCU or the siRNA]. The spontaneous mitochondrial Ca2+ oscillations were barely detectable in siRNA transfected cells (data not shown), whereas in MCU-overexpressing cardiomyocytes (Fig. 5B), they were approximately twice as large as those of controls (Fig. 5A) (control, 0.055 ± 0.035; MCU, 0.116 ± 0.052; n = 35 cells from four different preparations, P < 0.05). Fig. 5C shows the normalized average values.

We then analyzed the cytoplasmic Ca2+ oscillations in cells in which MCU levels were genetically manipulated. If mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake can significantly contribute to the buffering of cytoplasmic Ca2+ during systole, it is predicted that the amplitude of the cytoplasmic Ca2+ oscillations should be reduced in cells overexpressing the MCU compared with untreated controls. Fig. 6 A and B shows the representative traces of cytosolic Ca2+ oscillations of a control and a MCU-overexpressing cell, and in Fig. 6E, the normalized average values. In MCU-overexpressing cells, the cytoplasmic ΔR/R0 peak was on average 69.48 ± 3.88% that of control cells (n = 80 cells from six different preparations; P < 0.01). Fig. 6 C and F, on the contrary, show that in cells in which MCU was silenced by siRNA, the peak amplitude of the cytoplasmic Ca2+ oscillation (ΔR/R0) was increased to 158.7 ± 7.3% (n = 80 cells, from six different preparations; P < 0.01, unpaired t test) compared with that of cells transfected with scrambled siRNA. Moreover, experiments carried out in the whole cell population by using the aequorin Ca2+ probe confirmed the buffering effect of mitochondria on cytosolic Ca2+ transients. Fig. S4 shows that overexpression of MCU, or its down-regulation, similarly affected the peak amplitudes of cytosolic Ca2+ elicited by adding CaCl2 to cells preincubated in Ca2+-free medium. We also investigated the behavior of hot spots in cells where the MCU was down-regulated (by siRNA) or overexpressed. The average number of hot spots was not appreciably modified by modulation of MCU levels (26.1 ± 3.5% in control, 24.7 ± 6.3% in MCU-overexpressing and 27.7 ± 5.7% in siRNA-treated cells, n = 12 cells from three different preparations), as shown in Fig. S5. The final question is whether mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake contributes solely to buffering the maximal peak Ca2+ amplitude or also to modulate the decay rate toward basal, or both. Fast-resolution confocal analysis was thus carried out, as described above, by loading cardiomyocytes with Fluo-4. Fig. 6G shows that down-regulation of MCU increased the peak amplitude of the cytoplasmic signal by 63% (as observed with the D1cpv), whereas the decay rate tended to be slower, although the difference was not statistically significant (control, 219 ± 40 ms; siRNA-MCU, 258 ± 49 ms; n = 40 cells from four different preparations; P = 0.098). As predicted, the changes in the cytosolic Ca2+ peaks elicited by modulating the MCU level modified the amplitude of the cardiomyocyte contraction. As shown in Fig. S6, MCU overexpression reduced, whereas down-regulation increased, the amplitude of contraction. MCU level modulation also affected the frequency of spontaneous cytosolic Ca2+ oscillations: MCU down-regulation caused a significant reduction in the oscillation frequency (from 7.33 ± 0.33 oscillations per 10 s in cells treated with the scramble siRNA to 4.56 ± 0.43 in siRNA-MCU treated cells P < 0.05 (n = 38 cells from five different preparations). Overexpression of MCU had a tendency to increase the oscillation frequency, but the effect was not statistically significant (control: 6.76 ± 0.31/10 s, MCU-overexpressing cells: 7.23 ± 0.45 /10 s; P = 0.08).

Discussion

The importance of mitochondria in heart pathophysiology is undisputed: these organelles are the major source of ATP, and a block of oxygen supply results in a rapid stop of heart beating, followed, if blood flow is not rapidly restored, by necrosis and/or apoptosis of cardiac cells (6, 7). This chain of events can be easily reproduced in vitro by using neonatal cardiomyocytes: Inhibition of mitochondrial ATP synthesis results in a few seconds in the complete block of spontaneous Ca2+ oscillations and contractions, followed within a few hours by cell death. Although the role of oxidative phosphorylation in heart energy supply is undisputed, the function of the other key property of mitochondria, e.g., their capacity to efficiently take up Ca2+ from the cytoplasm under physiological conditions, is still a matter of debate (8, 9). A wide consensus has been reached in the scientific community about the importance of intramitochondrial Ca2+ in the activation of the key dehydrogenases (10–14) that feed electrons into the respiratory chain; however, whether Ca2+ is taken up and released by the organelles on a beat-to-beat basis, or whether Ca2+ uptake occurs slowly, by temporally integrating cytosolic Ca2+ transients is still debated (2, 15–17). Even less clear is the role of mitochondrial Ca2+ accumulation in buffering the amplitude of the systolic Ca2+ peaks (8).

These important issues have been intensively investigated, but with two major limitations: (i) the molecular nature of mitochondrial Ca2+ transporters have been an unresolved enigma for 50 years: The general properties were defined, but the identity of the molecules involved remained elusive (13, 18); (ii) no adequate pharmacological tool was available to act on this process without major side effects. Commonly used procedures, such as the use of uncouplers or inhibitors of the respiratory chain, are unsuited to address this issue, because they inhibit not only Ca2+ uptake, but also ATP synthesis; inhibitors of the Ca2+ release mechanism, in particular the mitochondrial Ca2+/Na+ exchanger, have important side effects on plasma membrane channels and transporters; Ruthenium Red, or Ru360, the only “specific” inhibitors of the MCU, have provided ambiguous results (19). The latter drugs, in fact, not only can inhibit within the cells the RyR and, thus, SR Ca2+ release, but their permeability through the plasma membrane (and accordingly their effect in intact cells) have been strongly challenged (19). The second major limitation has been the lack of suitable probes for measuring [Ca2+] in the microdomains that promote or decode mitochondrial Ca2+ signals. Indeed, it is widely accepted that generation of high [Ca2+] microdomains in proximity of ER/SR-mitochondria contact sites is essential to permit the high rate of Ca2+ uptake observed in many intact living cells (3, 20). The existence of such Ca2+ hot spots in cardiac cells, however, has been challenged, and no consensus has yet been reached (1).

Here, we addressed four fundamental issues (i) are microdomains of high [Ca2+] generated at the SR/mitochondria contacts in cardiomyocytes? (ii) what is the amplitude of these Ca2+ hotspots? (iii) is the MCU repertoire limiting for mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake in heart cells? and (iv) does mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake affect the cytoplasmic Ca2+ transients?

The first, partially unexpected, information obtained by the use of the genetically encoded probes is that, unlike what is observed in many cultured cell types challenged with IP3 generating agonists, in cardiomyocytes, during spontaneous Ca2+ oscillations, the peak amplitude of the Ca2+ rise is smaller in the nucleoplasm compared with the cytosol. This difference is presumably due to the fact that the high speed of the Ca2+ transient in cardiomyocytes does not allow complete equilibration of the two compartments. This conclusion is supported by the following observations: (i) The difference between the Ca2+ levels in the two compartments does not depend on different Ca2+ affinity of the two probes, because it disappeared when slower and more prolonged Ca2+ increases were followed, such as upon caffeine challenge or KCl-induced depolarization; (ii) such a difference was observed both in cells cotransfected with the nuclear and cytosolic probes and in cells where the cytosolic probe was mistargeted also to the nucleoplasm; (iii) a difference in the peak Ca2+ amplitude between nucleus and cytoplasm was observed, also by using a fluorescent dye such as Fluo-4. The data obtained with the genetically encoded Ca2+ indicators and the intracellularly trappable fluorescent probes are complementary. The GFP-based protein indicators, unlike the dyes, can be selectively targeted and should more closely mimic the diffusion rate within the cytoplasm of endogenous mobile Ca2+ buffers; however, their lower fluorescence intensity and relatively high speed of bleaching partially limit the achievable time resolution. Ca2+ dyes, on the contrary, allow a very good time resolution, but accelerate substantially the speed of Ca2+ diffusion within the cells (21). Despite this latter limitation, most often neglected, the Ca2+ indicators directly demonstrate that a significant delay exists between the Ca2+ peaks during spontaneous oscillations in the two compartments and that the cytoplasmic peak amplitude during spontaneous oscillations in the cardiomyocytes is larger than in the nucleoplasm. Because of the acceleration of the Ca2+ diffusion caused by the dye, such differences are probably underestimated.

As to Ca2+ hot spot generation, we show not only that the average Ca2+ peaks during systole (or caffeine treatment) measured on the OMM are significantly higher than those measured in the nucleus and, to a lesser extent in the cytoplasm, but also that a large part (∼25%) of the OMM is covered by microdomains of high [Ca2+] that can reach values as high as 30 μM.

Then, we used genetic manipulation of MCU to investigate the contribution of mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake in buffering cytoplasmic Ca2+ during systole. We show that down-regulation of the MCU and, thus, of mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake capacity, results in a substantial amplification of the cytoplasmic Ca2+ peaks during spontaneous oscillations, whereas overexpression of MCU drastically reduces the amplitude of such peaks. The data unambiguously demonstrate that, at least in the neonatal cells, a significant fraction of the Ca2+ released during systole is taken up by mitochondria and then released back into the cytoplasm during diastole, resulting in a significant buffering of the Ca2+ peaks. Thus, the first analysis of a physiologically relevant cell type indicates that MCU is the key rate-limiting molecule of organelle Ca2+ handling and that transcriptional control and/or pathological alterations of its expression may have a direct impact on key cell functions. It is clear that the data obtained in neonatal cell need to be confirmed in adult cardiomyocytes, however: (i) Most findings on Ca2+ handling initially obtained in neonatal cells have been confirmed in adult cardiac myocytes; (ii) the SR–mitochondria interactions are far more ordinate and tighter in adult cells and, accordingly, one may expect that Ca2+ transfer between the two organelles should be, if anything, more efficient in adult compared with neonatal cardiomyocytes.

Overall, the data demonstrate that, also in cardiomyocytes, mitochondrial Ca2+ loading strictly depends on the subcellular architecture and that the tight and highly controlled Ca2+ coupling between SR and mitochondria allows the latter organelles to act as significant buffers shaping the cytosolic Ca2+ transient and, thus, the amplitude and timing of cell contraction. In this situation, mitochondrial Ca2+ homeostasis emerges as an important regulatory mechanism of cardiac physiology that may be affected in pathological conditions and be targeted by new drugs.

Materials and Methods

Cardiomyocyte Culture.

Cultures of cardiomyocytes were prepared form ventricles of neonatal Wistar rats (0–2 d after birth) as described (2).

Fluorescence Imaging.

Cells expressing the different probes were analyzed 48 h after transfection in an inverted Leica DMI 600 CS microscope equipped with a 63×/1.4 N.A. oil objective. Excitation from a Hg 100-W light source was selected by a BP filter (436/20) and a 455 DCXR dichroic mirror. Emission light was acquired through the beam splitter (OES srl; dichroic mirror 515 DCXR; emission filters ET 480/40M for CFP and ET 535/30M for YFP) by using an IM 1.4C cooled camera (Jenoptik Optical Systems). Images were collected with continuous illumination and an exposure time of 100 ms per image. The temperature was maintained at 37 °C by using a temperature-controlled chamber (OKOlab). Images were then analyzed with custom-made software (3, 22). For Fluo-4 measurements, cells were loaded with 2 μM Fluo-4/AM for 30 min in standard medium and washed three times before analysis.

Pixel-by-Pixel Analysis.

We used the same assumptions and algorithms described (3). Two minor modifications were introduced, however: (i) We considered the peak value (ΔRmax /R0) of each pixel only at the peak of a spontaneous oscillation; (ii) because the mean amplitude of the ΔR/R0 changes was substantially larger in the cytoplasm (or on the OMM) than in nucleoplasm, “hot” spots were defined as those pixels that were at least 30% larger than the average of the OMM or cytoplasmic peak values. This definition leads to a small underestimation of “hot” pixel number, whereas assuming as hot pixels those that were 30% larger than the average ΔRmax /R0 of the nucleoplasm, as in ref. 3, would have led to a substantial overestimation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank P. Magalhães for useful comments. We acknowledge the financial support from Progetti di Rilevante Interesse Nazionale (PRIN) Project 2009CCZSES and Fondo Investimenti Ricerca di Base (FIRB) Project RBAP11X42L from the Italian Ministry of Research (to T.P. and R.R.); European Research Council (ERC) Advanced grants, Cassa di Rispamio di Padova e Rovigo (CARIPARO) Foundation, Telethon Italy, and Associazione Italiana Ricerca sul Cancro (AIRC) (to R.R.); and FIRB Project Nanotechnology and the Italian Institute of Technology, ITT (to T.P.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1210718109/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Franzini-Armstrong C. ER-mitochondria communication. How privileged? Physiology (Bethesda) 2007;22:261–268. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00017.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Robert V, et al. Beat-to-beat oscillations of mitochondrial [Ca2+] in cardiac cells. EMBO J. 2001;20:4998–5007. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.17.4998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Giacomello M, et al. Ca2+ hot spots on the mitochondrial surface are generated by Ca2+ mobilization from stores, but not by activation of store-operated Ca2+ channels. Mol Cell. 2010;38:280–290. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Stefani D, Raffaello A, Teardo E, Szabò I, Rizzuto R. A forty-kilodalton protein of the inner membrane is the mitochondrial calcium uniporter. Nature. 2011;476:336–340. doi: 10.1038/nature10230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baughman JM, et al. Integrative genomics identifies MCU as an essential component of the mitochondrial calcium uniporter. Nature. 2011;476:341–345. doi: 10.1038/nature10234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pacher P, Hajnóczky G. Propagation of the apoptotic signal by mitochondrial waves. EMBO J. 2001;20:4107–4121. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.15.4107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nakagawa T, et al. Cyclophilin D-dependent mitochondrial permeability transition regulates some necrotic but not apoptotic cell death. Nature. 2005;434:652–658. doi: 10.1038/nature03317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maack C, et al. Elevated cytosolic Na+ decreases mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake during excitation-contraction coupling and impairs energetic adaptation in cardiac myocytes. Circ Res. 2006;99:172–182. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000232546.92777.05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sedova M, Dedkova EN, Blatter LA. Integration of rapid cytosolic Ca2+ signals by mitochondria in cat ventricular myocytes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2006;291:C840–C850. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00619.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Denton RM. Regulation of mitochondrial dehydrogenases by calcium ions. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1787:1309–1316. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2009.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McCormack JG, Denton RM. The role of mitochondrial Ca2+ transport and matrix Ca2+ in signal transduction in mammalian tissues. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1990;1018:287–291. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(90)90269-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robb-Gaspers LD, et al. Integrating cytosolic calcium signals into mitochondrial metabolic responses. EMBO J. 1998;17:4987–5000. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.17.4987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rizzuto R, Pozzan T. Microdomains of intracellular Ca2+: Molecular determinants and functional consequences. Physiol Rev. 2006;86:369–408. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00004.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duchen MR. Mitochondria and Ca(2+)in cell physiology and pathophysiology. Cell Calcium. 2000;28:339–348. doi: 10.1054/ceca.2000.0170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Trollinger DR, Cascio WE, Lemasters JJ. Mitochondrial calcium transients in adult rabbit cardiac myocytes: Inhibition by ruthenium red and artifacts caused by lysosomal loading of Ca(2+)-indicating fluorophores. Biophys J. 2000;79:39–50. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76272-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pacher P, Thomas AP, Hajnóczky G. Ca2+ marks: Miniature calcium signals in single mitochondria driven by ryanodine receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:2380–2385. doi: 10.1073/pnas.032423699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sharma VK, Ramesh V, Franzini-Armstrong C, Sheu SS. Transport of Ca2+ from sarcoplasmic reticulum to mitochondria in rat ventricular myocytes. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2000;32:97–104. doi: 10.1023/a:1005520714221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Drago I, Pizzo P, Pozzan T. After half a century mitochondrial calcium in- and efflux machineries reveal themselves. EMBO J. 2011;30:4119–4125. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hajnóczky G, et al. Mitochondrial calcium signalling and cell death: Approaches for assessing the role of mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake in apoptosis. Cell Calcium. 2006;40:553–560. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2006.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Csordás G, et al. Imaging interorganelle contacts and local calcium dynamics at the ER-mitochondrial interface. Mol Cell. 2010;39:121–132. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.06.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gabso M, Neher E, Spira ME. Low mobility of the Ca2+ buffers in axons of cultured Aplysia neurons. Neuron. 1997;18:473–481. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81247-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zampese E, et al. Presenilin 2 modulates endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-mitochondria interactions and Ca2+ cross-talk. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:2777–2782. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1100735108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.