Abstract

Although the ketogenic diet (KD) has been widely accepted as a legitimate and successful therapy for epilepsy and other neurological disorders, its mechanism of action remains an enigma. The use of the KD causes major metabolic changes. The most significant of them seems to be the situation of chronic ketosis, but there are others as well, for instance, high level of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs). These “primary” influences lead to “secondary”, in part adaptive, effects, for instance changes in mitochondrial density and gene expression. Clinically, the influences of the diet are considered as anticonvulsive and neuroprotective, although neuroprotection can also lead to prevention of seizures. Potential clinical implications of these mechanisms are discussed.

1. Introduction

The value of the ketogenic diet (KD) has been recognized in the treatment of epilepsy, although the exact mechanisms by which it exerts its effect remain an enigma [1]. They seem to be different from those of regular antiepileptic medications (AEDs) [2], and discovering what they are may lead to its use in clinical situations other than epilepsy as well [3].

The KD is comprised of four elements, the changes of any of them can potentially lead to losing its anticonvulsant effect: (1) increased amount of fat, usually in a ratio of 3 to 4 grams of fat for each gram of protein and carbohydrates, (2) as low a consumption of glucose as possible, (3) caloric restriction, and (4) fluid restriction [1]. Although there is some debate about the last component [4], clinical practice has shown that stopping fluid restriction can lead to seizure recurrence much in the same way as when stopping glucose restriction.

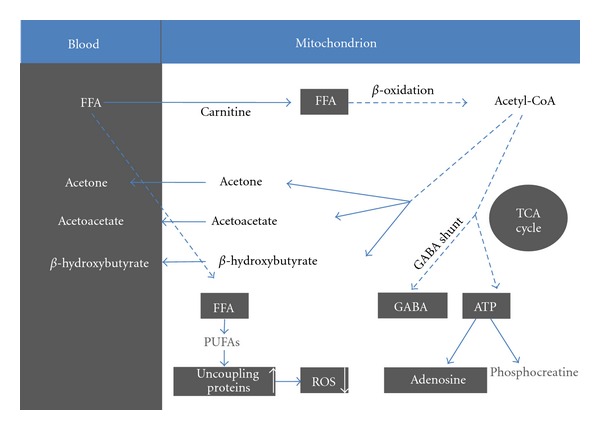

Stringent observation of the KD leads to chronic ketosis [5] in the following way. The most important result of observing the diet is the increased blood level of free fatty acids (FFAs). The FFAs are transferred into the mitochondria, a process which requires the presence of an appropriate amount of carnitine, where they are degraded into ketone bodies through β oxidation. These ketone bodies include β hydroxybutyrate, acetoacetate, and acetone [5] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Main metabolic changes which take place during the use of the ketogenic diet.

1.1. Role of Ketone Bodies

The effect of the increased amount of ketone bodies seems to be the most prominent of all other suggested antiepileptic mechanisms of the KD. The degradation of the ketone bodies delivers acetyl-CoA directly to the tricarboxylic acid cycle, thus increasing its turnover while bypassing the need to depend on acetyl-CoA coming from glycolysis to produce ATP. Unlike glucose, which requires a transporter to cross the blood brain barrier, the ketone bodies penetrate it easily. When this transporter is deficient, as in glut 1 deficiency, the KD is the preferred way of antiepileptic treatment, since it allows for bypassing the need for glucose [1]. Children in whom the conversion of pyruvate to acetyl-CoA is blocked, for instance, in pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) deficiency, will also benefit from bypassing this route [3]. β hydroxybutyrate is the predominant ketone body measured in the blood, and it is used to monitor the degree of ketosis during therapy. The degradation of β hydroxybutyrate leads to increased production of acetone [6]. The breath of a patient who is ketotic while on the diet will often even smell of acetone. Acetone is one of the ketone bodies that have an anticonvulsant effect in several types of mouse seizure models [7]. The mechanism of this effect is unknown, although an effect on K2p channels has been proposed [5].

By means of the TCA cycle, acetyl-CoA increases the level of the neurotransmitters glutamate and γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) and the major excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmitters in brain, respectively. A net effect of increased GABAergic influence can be responsible for an anticonvulsant action [5].

1.2. Role of Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids

Another product of an elevated level of free fatty acids is polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs). The potential ability of PUFAs to block seizure activity in the brain is speculated to be associated with some rather more complicated mechanisms, including (1) directly inhibiting voltage-gated sodium and calcium channels, (2) activating a lipid-sensitive potassium channel, (3) enhancing the activity of the sodium pump to limit neuronal excitability, (4) activating peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-α (PPARα), and (5) inducing the expression and activity of brain-specific uncoupling proteins in the mitochondria, thereby inducing a neuroprotective effect [5]. This last effect works through limiting reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation.

1.3. The Concept of Bioenergetics and Neuroprotection

The ketogenic diet is primarily anticonvulsant. However, in several aspects the KD is also neuroprotective. Neuroprotection can contribute to the anticonvulsant effect, but it may have other effects as well, which can lead to other clinical uses of the KD [3]. Overall, the use of the KD enhances energy production in the brain. Appleton and De vivo [8] reported that the KD increased the total quantity of bioenergetic substrates (adenosine triphosphate (ATP)) and elevated the energy charge in rat brain. Acetoacetate, a product of β hydroxybutyrate dehydrogenation, is transferred into acetyl-CoA which enters the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle. The increased turnover of the TCA cycle generates protons and electrons that are channeled to the electron transport chain. This, in turn, drives the formation of ATP from adenosine phosphate (ADP) by ATP synthase. Enhanced ATP can either be converted to phosphocreatine for energy storage or broken into adenosine. Enhanced ATP levels provide energy reserves for a neuron to continue functioning under stress. Increased extracellular adenosine offers a neuroprotective buffer against insults, reduces excitation, and averts excessive ATP demands, thus providing local seizure control and neuroprotection [6].

It was also suggested that the KD influences toward an upregulation of transcripts encoding energy metabolism enzymes and increase in the density of mitochondria in neuronal process, leading to heightened energy reserves. An improved energetic status can support seizure prevention, for instance, by supporting GABAergic inhibition [9]. It is suggested that adaptive processes to the metabolic changes induced by the diet lead to changes in gene expression which in turn result in some of the above-noted changes.

Other path of neuroprotection is modulated through decreased generation of ROS which is considered to be related to PUFAs effect on uncoupling proteins [5].

1.4. Other Clinical Applications of the Ketogenic Diet

The fact that the KD is considered a proven therapy with relatively few adverse affects and wide clinical experience, particularly in children, led to recent studies investigating new potential uses for other neurological disorders [3]. One of the most intriguing and active fields of research is the effect of a high-fat caloric-restricted diet on the survival of brain tumors cells. Brain cancer cells have restricted metabolic flexibility and are dependent mainly on glucose metabolism. It is hypothesized that mitochondrial abnormalities impair the ability of brain tumors to generate energy from ketone bodies. Unlike normal cells, malignant tumor cells have impaired genetic adaptability due to their genetic abnormalities and, therefore, increased susceptibility to environmental stress, such as fasting or caloric restriction. The same genomic defects that are involved in the creation of brain tumors can be exploited for their destruction [3, 10, 11].

In 1995, Nebeling et al. [12] reported two young girls with unresectable advanced stage brain tumors who had poor response to radiation and chemotherapy. They were treated with a KD and their response was remarkable, both clinically and according to positron emission tomography follow-up scans. Zuccoli et al. [13] described a patient with glioblastoma multiforme whose tumor, which is very malignant, improved on the KD. Surprisingly, despite the appealing efficacy of this treatment, no further human studies or clinical trials on the KD as a therapy for brain tumors have been conducted. Several laboratory studies in mouse and rat models have recently confirmed that inhibition of brain tumor growth is directly related with reduced levels of glucose and elevated levels of ketone bodies. Moreover, the KD was shown to reduce reactive oxygen species (ROS) in the brain [5]. Cancer cells need high levels of ROS for the induction of angiogenesis and the production of tumor growth factors [11], thus, through this mechanism the KD can be protective.

2. Illustrative Case

A 12-year-old girl was diagnosed as having neurocutaneous melanosis with CNS involvement. The tumor was highly malignant and had a very rapid course of progression. The clinical manifestations were mainly intractable seizures that necessitated repeated admissions to the intensive care unit, as well as severe cognitive and alertness decline. After the oncologists decided that antitumor treatment would be ineffective, she was started on the KD. After four weeks of trial, it did not have any effect on the tumor progression. Seizure frequency and severity improved, but she was being treated concomitantly with AEDs. However, it did have a notable improving effect on cognition, alertness, and mood of the girl, in spite of her devastating condition. The patient expired several weeks after the initiation of the diet.

The beneficial effect of the KD on cognition, alertness, and mood is well recognized [1], and clinical experience shows that in many times it is not less important than the anticonvulsant effect. This may be especially true for youngsters at progressive stages of their oncologic disease.

The potential neuroprotective effect of the KD was what motivated investigations into its potential as a treatment option in other neurologic disorders [3]. There are increasing numbers of reports that ketosis achieved by starvation or administration of a KD has a consistent neuroprotective effect after various brain injuries in animal models. One human pilot study and several animal model studies have shown improvement in autistic behavior parameters with KD treatment. It remains to be further clarified whether this improvement is related to reduced epileptic activity found in up to 30% of these patients or to a primary effect of the KD [3].

A factor that can be crucial for the application of the KD in medical conditions other than intractable epilepsy is the inherent difficulties in its use [14]. Dietary restriction can pose a significant problem in a child with a progressive tumor that undergoes massive chemotherapy, who may already be cachectic. The KD may not be an option in a grown-up hyperactive autistic child. Thus, the neurologist must evaluate the appropriate clinical, familial, and environmental situations very cautiously prior to the recommendation of the KD.

In conclusion, the major metabolic effect of the KD is in supplying the brain with an increased amount of free fatty acids. Their degradation into ketone bodies, together with the load of PUFAs, leads to major changes in the metabolic, bioenergetic, mitochondrial, and even genetic constellation. These primary and secondary changes have anticonvulsant and neuroprotective effects. The KD is now a significant component of the armamentarium of the pediatric epileptologists. Whether it may also be effective in other pathologies, especially in treating malignancies, awaits future research.

References

- 1.Hartman AL, Vining EPG. Clinical aspects of the ketogenic diet. Epilepsia. 2007;48(1):31–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.00914.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hartman AL, Freeman JM. Does the effectiveness of the ketogenic diet in different epilepsies yield insights into its mechanisms? Epilepsia. 2008;49(supplement 8):53–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.01835.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barañano KW, Hartman AL. The ketogenic diet: uses in epilepsy and other neurologic illnesses. Current Treatment Options in Neurology. 2008;10(6):410–419. doi: 10.1007/s11940-008-0043-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wirrell EC. Ketogenic ratio, calories, and fluids: do they matter? Epilepsia. 2008;49(supplement 8):17–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.01825.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bough KJ, Rho JM. Anticonvulsant mechanisms of the ketogenic diet. Epilepsia. 2007;48(1):43–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.00915.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Masino SA, Kawamura M, Wasser CA, Pomeroy LT, Ruskin DN. Adenosine, ketogenic diet and epilepsy: the emerging therapeutic relationship between metabolism and brain activity. Current Neuropharmacology. 2009;7(3):257–268. doi: 10.2174/157015909789152164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hasebe N, Abe K, Sugiyama E, Hosoi R, Inoue O. Anticonvulsant effects of methyl ethyl ketone and diethyl ketone in several types of mouse seizure models. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2010;642:66–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2010.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Appleton DB, De Vivo DC. An experimental animal model for the effect of ketogenic diet on epilepsy. Proceedings of the Australian Association of Neurologists . 1973;10:75–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bough K. Energy metabolism as part of the anticonvulsant mechanism of the ketogenic diet. Epilepsia. 2008;49(supplement 8):91–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.01846.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seyfried BT, Kiebish M, Marsh J, Mukherjee P. Targeting energy metabolism in brain cancer through calorie restriction and the ketogenic diet. Journal of Cancer Research and Therapeutics. 2009;5(supplement 1):S7–15. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.55134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stafford P, Abdelwahab MG, Kim DY, Preul MC, Rho JM, Scheck AC. The ketogenic diet reverses gene expression patterns and reduces reactive oxygen species levels when used as an adjuvant therapy for glioma. Nutrition and Metabolism. 2010;7, article 74 doi: 10.1186/1743-7075-7-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nebeling LC, Miraldi F, Shurin SB, Lerner E. Effects of a ketogenic diet on tumor metabolism and nutritional status in pediatric oncology patients: two case reports. Journal of the American College of Nutrition. 1995;14(2):202–208. doi: 10.1080/07315724.1995.10718495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zuccoli G, Marcello N, Pisanello A, et al. Metabolic management of glioblastoma multiforme using standard therapy together with a restricted ketogenic diet: case report. Nutrition & Metabolism. 2010:p. 33. doi: 10.1186/1743-7075-7-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cross JH, Mclellan A, Neal EG, Philip S, Williams E, Williams RE. The ketogenic diet in childhood epilepsy: where are we now? Archives of Disease in Childhood. 2010;95(7):550–553. doi: 10.1136/adc.2009.159848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]