Abstract

The temporal lobe is a common focus for epilepsy. Temporal lobe epilepsy in infants and children differs from the relatively homogeneous syndrome seen in adults in several important clinical and pathological ways. Seizure semiology varies by age, and the ictal EEG pattern may be less clear cut than what is seen in adults. Additionally, the occurrence of intractable seizures in the developing brain may impact neurocognitive function remote from the temporal area. While many children will respond favorably to medical therapy, those with focal imaging abnormalities including cortical dysplasia, hippocampal sclerosis, or low-grade tumors are likely to be intractable. Expedient workup and surgical intervention in these medically intractable cases are needed to maximize long-term developmental outcome.

1. Introduction

The temporal lobe plays a vital role in epilepsy and is the most frequent lobe involved in focal onset seizures. Temporal lobe epilepsy in children and infants has clear clinical features which make it distinct from the fairly homogeneous syndrome seen in adults.

Reported studies of temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) in children are heavily biased towards those with medically intractable epilepsy, and few studies focus on cohorts who are newly diagnosed. This paper will address pediatric-specific aspects of TLE, including clinical semiology in young children, pediatric epilepsy syndromes involving the temporal lobe, medical and surgical management, associated psychiatric and cognitive disorders, and long-term outcomes.

2. Epidemiology

The overall incidence of new-onset epilepsy in children ranges from 33 to 82 per 100,000 children per year, and approximately half- to two-thirds of these children have focal-onset seizures [1–6]. However, the exact incidence of TLE is not known, as the specific lobe of onset is not specified in most incidence studies. Compared to adults, focal seizures in children are more likely to arise from extratemporal foci. Simon Harvey et al. identified 63 children with new-onset TLE over a 4-year period in the state of Victoria, Australia (population 4.4 million) [7]. In our 30-year cohort of new-onset epilepsy in children, 276/468 (59%) had nonidiopathic focal epilepsy. Of these, 20 (7.2%) had a focal lesion on MRI in the temporal region (10: mesial temporal sclerosis, 1: malformation of cortical development, 2: ischemia/gliosis, 1: tumour, and 4: vascular malformation), while 17 (6.1%) had normal imaging and a single focus of epileptiform discharge in the temporal region. Therefore, it was determined that TLE was responsible for 8% of all pediatric epilepsy, and for 13% of all focal seizures in our cohort [1].

3. Semiology of Temporal Lobe Seizures in Children

One of the defining characteristics of TLE is its unique semiology. These features, which have been studied extensively in adults, can help clinicians to localize seizures to the temporal region prior to capturing interictal/ictal epileptiform discharges. Such information is particularly valuable when evaluating patients with medically intractable epilepsy. When concordant with structural magnetic resonance imaging and electroclinical data, seizure semiology can facilitate the identification of candidates for successful surgical interventions [8]. The semiology of temporal lobe seizures in children has previously been investigated, although less robustly than in adults. Like adults, children with TLE are more likely to demonstrate specific semiologies when their seizures arise from specific portions of the temporal lobe (e.g., mesial, lateral, or insular). However, in contrast to adults, the semiology of TLE in children can be profoundly affected by age and brain development. Such changing semiology can present a challenge to physicians attempting to identify (and effectively treat) children with TLE.

3.1. Semiology of TLE in Infants and Toddlers (Age 0–3 Years)

Some of the most difficult temporal lobe seizures to identify utilizing semiology alone are those arising in infants and toddlers. Unlike older children, infants and toddlers are more likely to display seizure semiologies reminiscent of extratemporal and generalized epilepsies. Previous studies have documented an inverse relationship between the occurrences of ictal motor manifestations and age [9–14]. Such motor manifestations include tonic, clonic, myoclonic, and hypermotor seizures, and epileptic spasms [9, 10, 14]. Despite their unilateral origin, such movements can appear bilateral and symmetric, complicating attempts to lateralize seizure onset [9, 13]. They can also be easily mistaken for frontal lobe seizures [9, 13]. The likely reason for the increased motor manifestations of TLE in infants and toddlers is the presence of focal pathology in the setting of incomplete CNS myelination [14, 15]. This is particularly pertinent with regards to the limbic system, which is resistant to synchronization in an immature state [10, 16–19]. The occurrence of epileptic spasms in young children with temporal lobe pathology is likely secondary to rapid secondary generalization of focal onset seizures via dysfunctional cortical-subcortical interactions (particularly involving the thalamus, basal ganglia, and other brain stem structures). This can result in the generalized semiologic and EEG appearances, making identification of the ictal-onset zone problematic (Figure 1) [20, 21].

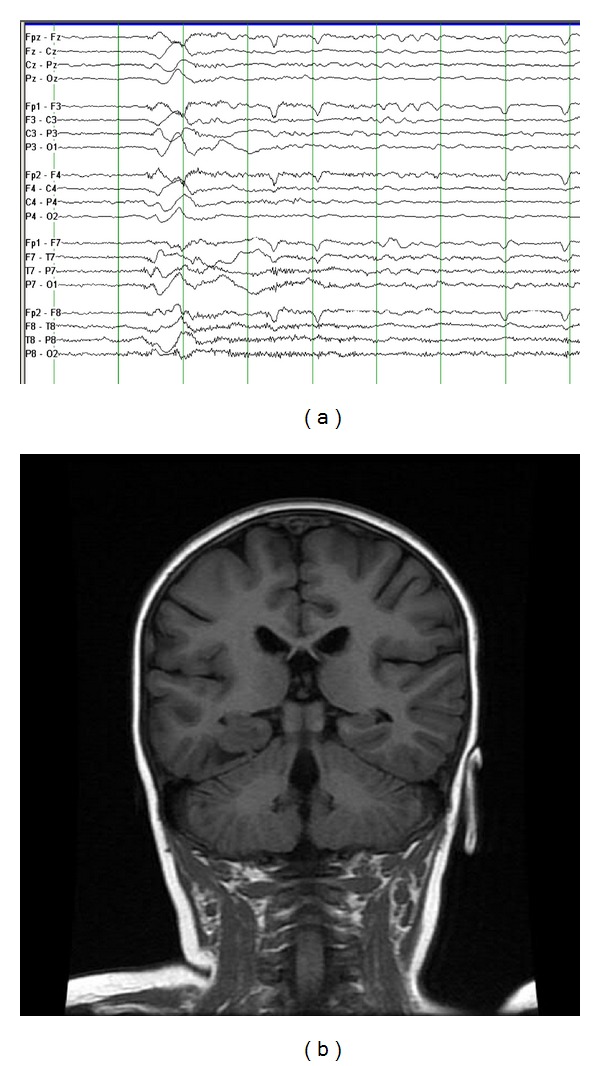

Figure 1.

This 2-year-old girl had onset of infantile spasms at the age 6 months, which were refractory to three antiepileptic medications. During the clusters of spasms, she had head drops, nonforced head turn, and eye deviation to the right, with elevation of both upper extremities. Her EEG (a) shows a generalized sharp wave followed by high frequency and low-amplitude activity during the spasm (50 microvolts/mm, 30 mm/sec). Her coronal FLAIR MRI (b) shows a lesion in the right temporal region, which was found to be a ganglioglioma. She has remained seizure-free since surgery.

One of the hallmarks of TLE in adults is the occurrence of automatisms. Although automatisms can be seen in infants and toddlers with TLE, they are typically simpler than those observed in older children and adults [9, 10, 12, 22–25]. These simpler automatisms include oroalimentary (lip smacking), gestural (hand fumbling), and blinking movements [9, 12, 24, 25]. This difference may arise from the limited repertoire of voluntary fine motor gestures in young children. Once such gestures develop later in life, they can be incorporated into complex automatisms [9, 22]. Given the lack of well-developed verbal communication skills in children aged 0–3 years, it is usually impossible for clinicians to properly assess for auras at seizure onset [9, 12, 26]. Rather, the earliest signs of such seizures in infants and toddlers may be behavioral arrest, staring, and lip cyanosis [25].

3.2. Semiology of TLE in Preschool and Early School-Age Children (Age 3–6 Years)

In contrast to infants and toddlers, preschool and early school-age children with TLE have better developed lateralizing motor manifestations with their seizures [9, 10]. This age group is more likely to demonstrate dystonic posturing, versive/nonversive head turning, and eye/mouth deviation [9, 23, 25, 27]. Dystonic posturing, eye/mouth deviation, and versive head turning have been found to lateralize to the contralateral hemisphere in this population, with correct lateralization in 75–100% of cases [23]. Nonversive early head turning correctly lateralizes to the ipsilateral hemisphere in 80% of cases in this age group [23].

In preschool and early school-age children with TLE, more complex automatisms can be observed. These include the oroalimentary automatisms seen in younger (age 0–3 years) children in addition to staring, looking around, and/or hand clapping [9, 10, 23, 25]. However, more complex automatisms are still less likely to be observed in this age group versus older children (age >6 years) and adults [23, 25]. They are also less likely to correctly lateralize to the ipsilateral hemisphere than in older children (50% versus 100%) [23].

Although children between the ages of 3 and 6 years with TLE are more likely to note auras at seizure onset than their younger counterparts, this can still be difficult to assess (given the subjective nature of such symptoms). Rather than asking children with presumed TLE about auras, it may be more prudent for clinicians to ask parents/caregivers about behaviors associated with such phenomenon. For example, a child who consistently cries or runs to a parent/caregiver at seizure onset may be experiencing ictal fear; this frequently localizes to the mesial temporal region [28, 29]. Conversely, children who demonstrate stereotyped unilateral ear plugging at the onset of seizures may be experiencing an auditory aura localizing to the contralateral superior temporal gyrus [30].

3.3. Semiology of TLE in Older Children and Adolescents (Age >6 Years)

Beyond the age of 6 years, children with TLE display much of the same seizure semiology as their adult counterparts. Some older children with TLE will report a prodrome hours (or potentially even days) prior to seizure onset. Such prodromes can consist of headaches, irritability, insomnia, personality changes, and/or a sense of impending doom [28]. However, children with TLE are less likely to experience such prodromes versus those with generalized tonic-clonic seizures [28]. Auras are common in older children with TLE (particularly mesial temporal lobe epilepsy) [25]. The most common aura reported by older children is an epigastric-rising sensation [28]. Other auras include olfactory, gustatory, somatosensory, auditory, visual, and other visceral (oropharyngeal, abdominal, genital, and retrosternal) alterations in self-perception and psychic (déjà vu, jamais vu, and/or a dreamy state) phenomena [28]. Such auras often yield the most useful information when attempting to localize seizure onset correctly. Seizures associated with macropsia, micropsia, macroacusia, or microacusia typically arise from the lateral temporal region [28]. Olfactory and gustatory hallucinations characteristically arise from the uncus [28]. Even emotions such as fear, strangeness, or embarrassment can represent simple partial seizures, sometimes originating from the amygdala [28].

Compared to children age 0–6 years, older children and adolescents with TLE are more likely to demonstrate automatisms with their seizures [10, 23]. Such automatisms include oroalimentary (lip smacking and swallowing) and gestural symptoms (picking, fumbling, and aimless movements) [28, 31]. When involving a single extremity, automatisms are a reliable lateralizing sign to the ipsilateral hemisphere; one study even reported 100% accuracy in lateralization in this age group [23]. Children age >6 years can also display tonic or dystonic posturing of an extremity (particularly the arm) with TLE, providing the seizure involves the motor strip [28]. Such posturing can assist clinicians in correctly lateralizing seizure onset to the contralateral hemisphere [28, 32]. However, care must be taken not to assume temporal localization with such posturing, as it can also arise from a seizure focus in the frontal lobe [28].

When seizures arising from the temporal lobe in children result in loss of consciousness, it is believed that there has been bilateral limbic involvement [28]. Complex partial seizures of temporal lobe onset can last for several minutes, which is typically longer than complex partial seizures arising from extratemporal (e.g., frontal) regions [28]. Such seizures are also more likely to secondarily generalize than similar seizures in younger children [10, 23]. Postictally, children with complex partial seizures of temporal lobe onset can display confusion, disorientation, fatigue, headaches, and continued automatisms [28]. Such behaviors can last for minutes to hours and can be difficult to clearly delineate from ictal phenomena [28]. However, they tend to be briefer than similar postictal behaviors demonstrated by adults with new onset TLE [27].

3.4. Abdominal Epilepsy of Temporal Lobe Onset in Children

A semiology of TLE which is more common in children versus adults is abdominal epilepsy. These seizures, which are typically accompanied by impairment of consciousness, are accompanied by abdominal pain and emesis [28]. The discomfort is usually periumbilical, colicky, and severe and can be accompanied by headache, dizziness, syncope, and temporary loss of vision [28, 33]. The duration of abdominal pain is usually limited to 10–15 minutes and may be associated with sweating, stomach growling, salivation, and flatus [28]. Such a diagnosis can be difficult for clinicians to make, ultimately requiring prolonged video EEG monitoring to establish [28].

3.5. Autonomic Effects of Childhood TLE

Another potentially useful marker of TLE in children is autonomic (cardiac and respiratory) changes. The most commonly observed autonomic change in temporal lobe seizures in children is ictal tachycardia. This occurs with roughly equal frequencies in children versus adults [34] and can be observed in up to 98% of all childhood temporal lobe seizures [35]. This is particularly true if they are of right hemispheric onset [35]. In contrast, ictal bradycardia is rare in children, occurring in less than 4% of monitored seizures [36]. Such seizures are typically extratemporal in onset [35, 36].

One of the most dramatic autonomic disturbances that can occur during temporal lobe seizures in children is hypoxemia and/or apnea. Nearly half of all children and one-fourth of their seizures captured in inpatient monitoring units are characterized by desaturations <90% [36]. Such desaturations were not trivial, with nearly one-third (32.1%) falling to <60% [36]. Ictal hypoxemia in children is not specific for TLE and is more likely to be observed when partial seizures secondarily generalize [36]. However, in younger children (age 2–6 years), apneic attacks may be the sole manifestation of TLE [28, 37]. Such hypoxemia/apnea could theoretically exacerbate bradycardia induced by carotid chemoreceptors, causing further respiratory suppression.

4. EEG Features of TLE

The scalp EEG in patients with TLE is important for making the initial diagnosis of epilepsy, as well as localizing seizure onset. The value of scalp EEG is improved by ensuring a sleep recording during routine EEG. Furthermore, localization of seizure onset is improved through the use of additional EEG electrodes, either sphenoidal or inferolateral temporal, as well as closely placed electrodes [38–41].

4.1. Interictal EEG Features of TLE

The interictal EEG in TLE is typically characterized by temporal spike or sharp-wave discharges and temporal intermittent rhythmic delta activity (TIRDA). Temporal spike or sharp-wave discharges are highly epileptogenic discharges that are maximal over the anterior temporal region and may prominently involve the ear leads (Figure 2). There is often increased activation of spike and sharp-wave discharges during drowsiness and sleep, with nearly 90% of patients with temporal lobe seizures showing spikes during sleep [42]. The spike-wave discharges may occur independently or synchronously over the bilateral temporal regions. However, most patients with bitemporal interictal EEG patterns are found to have unilateral temporal lobe seizures [39].

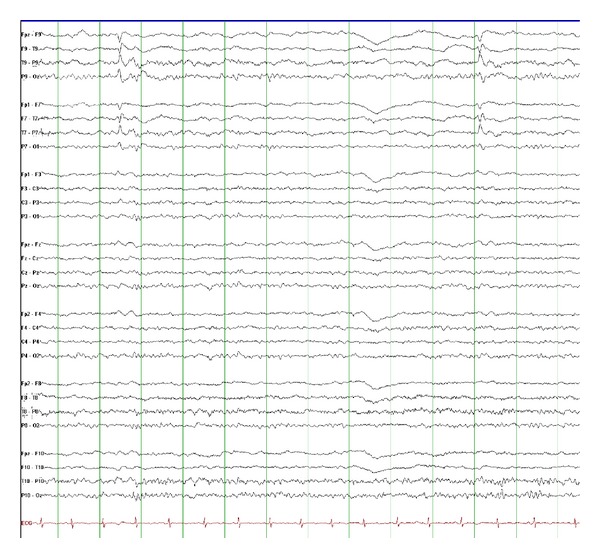

Figure 2.

This EEG shows interictal left temporal spikes recorded from a 13-year-old boy with left temporal lobe epilepsy due to mesial temporal sclerosis (10 microvolts/mm, 30 mm/sec).

TIRDA has also been seen in patients with TLE. Like the spike and sharp-wave discharges, TIRDA is also most prominent during drowsiness and NREM sleep (Figure 3). It is characterized by rhythmic trains of low- to moderate-amplitude, monomorphic delta frequency slow waves over unilateral or bilateral temporal regions. The monomorphic slow waves are without clinical correlate and must be differentiated from the polymorphic delta activity that would be seen with a focal lesion over the temporal region. TIRDA has the same epileptogenic significance as temporal spike and sharp-wave discharges [42].

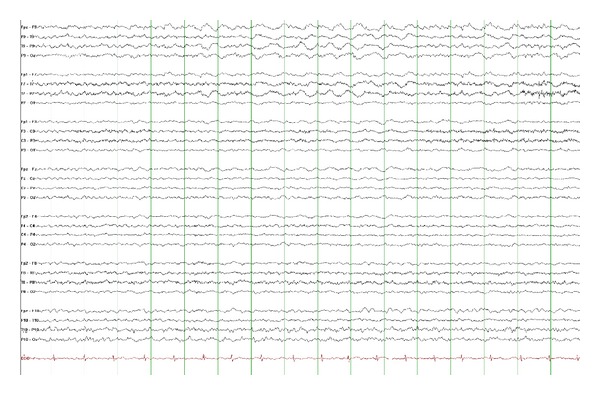

Figure 3.

Left temporal intermittent rhythmic delta activity (TIRDA) in a 12-year-old boy with temporal lobe epilepsy. TIRDA consists of rhythmic trains of low-moderate amplitude monomorphic delta frequency slow waves and is most commonly seen during drowsiness or sleep (15 microvolts/mm, 30 mm/sec).

4.2. Ictal EEG Features of TLE

The temporal lobe has the lowest threshold for seizures. However, it is important to note that scalp ictal and interictal EEG recordings in children may be poorly localizing, even in TLE, due to incomplete or abnormal brain maturation. A focal lesion can present with generalized or multiregional epileptiform discharges in infants and young children (Figure 1). Similarly, the ictal EEG in a focal seizure of anterior temporal lobe origin may initially demonstrate lateralized or generalized scalp EEG changes [43].

Typically, the scalp EEG during a temporal lobe seizure will demonstrate moderate- to high-amplitude rhythmic paroxysmal activity that is maximal over a unilateral temporal region (Figure 4). This may progress to generalized rhythmic slowing that is maximal on the side of seizure onset [44]. Prior to seizure onset and postictally, there may be increased interictal temporal or bitemporal spike wave activity. Postictally there may also be focal temporal or generalized arrhythmic slow wave activity. This must be distinguished from continuing seizure activity.

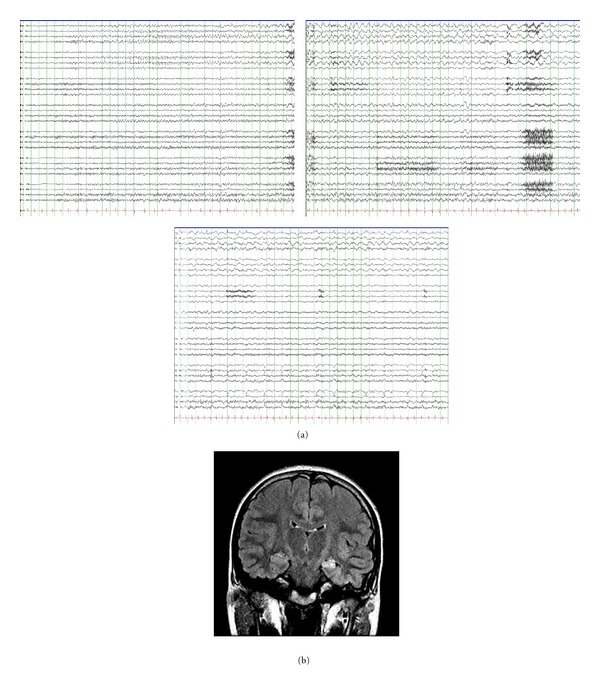

Figure 4.

(a) shows 3 consecutive pages of EEG illustrating the onset of a left mesial temporal seizure in a 13-year-old girl with a history of a prolonged febrile convulsion at the age of 18 months (10 microvolts/mm, 15 mm/sec). Her coronal FLAIR MRI (b) shows left mesial temporal sclerosis. Her seizures were intractable to medical therapy, but she became seizure-free after surgery.

5. Differential Diagnosis

Temporal lobe seizures and temporal EEG discharges are seen in several pediatric epilepsy syndromes. Seizures may be due to structural abnormalities, either congenital or acquired. Classically, mesial temporal lobe seizures are seen with hippocampal sclerosis, often preceded by a history of prolonged or atypical febrile seizures. Mesial TLE with hippocampal sclerosis has been identified as a distinctive constellation in the most recent epilepsy syndrome classification [45].

However, nonlesional temporal lobe syndromes must also be recognized, including autosomal dominant lateral TLE, idiopathic partial epilepsy with auditory features, familial mesial TLE, and partial reading epilepsy.

Autosomal dominant lateral TLE, also known as autosomal dominant partial epilepsy with auditory features, is associated with mutations in the leucine-rich, glioma-inactivated 1 (LGI1) gene in approximately 50% of families [46, 47]. Median age at onset is in late adolescence (range 1–60 years), and the focal seizures have prominent elementary auditory auras. Aphasic seizures are seen in 17% of cases and secondarily generalized seizures in 90%. Neuroimaging is usually normal and the clinical course is benign, with most patients achieving good control with antiepileptic medications. Epilepsy with similar features can be seen without family history and without LGI1 mutations [48].

In review of 100 individuals from 20 families, Crompton et al. characterized the clinical features of familial mesial TLE, which they propose is inherited in a polygenic (rather than autosomal dominant) manner [49]. Median age at seizure onset was 15 years (range 3–46 years), antecedent febrile seizures were seen in 9.8%, and nearly all patients had normal neuroimaging. Semiology is characterized by déjà vu, fear, and nausea, with evolution to a focal seizure with or without loss of awareness. Most patients had a relatively benign course with good response to medication.

Partial reading epilepsy presents with ictal alexia provoked by reading. The seizure is accompanied by left temporal ictal discharge although independent bilateral temporal seizure onset has been reported [50].

TLE must be differentiated from other pediatric epilepsy syndromes in which there is significant activation of spike-wave discharges during sleep. These include Landau Kleffner syndrome (LKS), continuous spike-wave during slow-wave sleep syndrome (CSWS), and benign childhood epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes (BCECTSs). Although epilepsy syndromes such as LKS and CSWS have been proven to be secondary to focal pathology amenable to resection in select children [51, 52], this infrequently localizes to the temporal lobe.

LKS and CSWS are both pediatric epilepsy syndromes that present during preschool or early school years with regression of skills with or without seizures. Early in the presentation, the EEG demonstrates spike and slow-wave discharges maximally over the frontotemporal and centrotemporal regions with increased activation during sleep. However, over time the spike-wave discharges during non-REM sleep become nearly continuous, with discharges occupying nearly 85% or more of sleep. The nearly continuous spike-wave discharge during sleep is termed electrical status epilepticus in slow-wave sleep (ESES). ESES resolves upon awakening and is without clinical accompaniment. The electrical status and seizures resolve in later childhood or adolescence in both LKS and CSWS. With resolution, there is some developmental improvement although development typically does not normalize in either syndrome [53]. Although there are clinical and electrophysiologic similarities in LKS and CSWS, these are clinically distinct syndromes.

LKS presents primarily as language regression and acquired auditory agnosia in children with previously normal development. This progresses over weeks to months and is often accompanied by irritability, hyperkinesia, attention deficit disorder, and autistic-like behavior [54]. Neuroimaging is normal, and the etiology is unknown. Seizures are common in LKS and may include focal seizures with or without loss of awareness, generalized tonic-clonic and atypical absence seizures although the most common seizure is a nocturnal hemiclonic seizure. The seizures are typically infrequent and easily treated. The epileptiform discharges and ESES in LKS occur maximally over the temporal regions, which correlates with receptive language regression [55–61].

In contrast to LKS, CSWS presents with global regression, including difficulties with expressive language, temporo-spatial skills, hyperkinesis, memory deficits, motor deficits, and poor behavior. Language comprehension is typically spared. Development prior to regression may be normal or delayed [56, 62–66]. In addition, radiologic abnormalities including atrophy and cortical migration abnormalities are frequently found in CSWS [56, 61, 67–69]. The majority of children with CSWS present with seizures, including generalized tonic-clonic, typical, or atypical absence, and focal seizures with or without loss of awareness. Atonic seizures can also occur, but tonic seizures do not. The seizures can occur frequently, up to several times per day [56, 57, 70]. The epileptiform discharges and ESES in CSWS occur maximally over the frontal head regions, which correlates with the global regression, expressive language abnormalities, and motor impairment seen in these children.

Finally, temporal lobe epilepsy must also be differentiated from benign childhood epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes (BCECTS). BCECTS presents in early- to mid-childhood with infrequent seizures. The seizures are commonly preceded by paresthesias of the face and hand, followed by speech arrest and excessive salivation, ipsilateral facial myoclonus that spreads to the ipsilateral hand, and hemiclonic or generalized tonic-clonic seizures. They typically occur out of sleep [71–73].

Like LKS and CSWS, the EEG in BCECTS demonstrates dramatic activation of epileptiform discharges during sleep, although typically occupying less than 85% of the sleep record. The epileptiform discharges in BCECTS are high amplitude, blunt, and maximal over the centrotemporal region (Figure 5). Serial EEGs may also demonstrate a shifting asymmetry of the centrotemporal discharges [55, 62, 71].

Figure 5.

This EEG is from an 8-year-old boy with early morning seizures consisting of unilateral facial twitching, drooling, and dysarthria. The EEG during sleep shows bilateral centrotemporal sharp waves (most prominent on the left) suggestive of benign childhood epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes (15 microvolts/mm, 30 mm/sec). These “rolandic” spikes most commonly show a dipole on referential montage, with frontal positivity and temporal negativity.

Children with BCECTS typically have normal cognition, and the seizures respond well to antiseizure medications. Furthermore, due to the infrequent nature of the seizures, medication may not be necessary. The prognosis of BCECTS is excellent, with spontaneous remission occurring in all children during adolescence.

6. Management of TLE in Children

Similar to other focal onset epilepsies, children with temporal lobe epilepsy are often initially treated through medication management. However, temporal lobe epilepsy often does not respond completely to antiseizure medications (AEDs). Therefore, both medical and surgical treatments will be discussed.

6.1. Medical Management

The goal of epilepsy management is long-term seizure freedom with minimal or no unacceptable side effects. Despite the availability of new antiepileptic drugs, there is no single AED that has proven superior efficacy in the management of focal seizures [74]. The choice of which drug to use depends on the individual patient characteristics and medication side effect profile. While newer drugs (e.g., oxcarbazepine, levetiracetam, lamotrigine, topiramate, etc.) are considered to have improved side effect profiles compared to older AEDs (phenytoin, phenobarbital, and carbamazepine), some of the newer medications carry greater risk for cognitive impairment (topiramate, zonisamide) or behavior problems (levetiracetam).

Furthermore, many children continue to have seizures in spite of adequate AED treatment. If two or more appropriate AEDs at adequate doses and duration have failed to control seizures, the probability of seizure freedom is low and diminishes progressively with further unsuccessful medication trials. Among newly diagnosed adults with epilepsy without prior medication trials, 47% to 50% became seizure-free with their first AED, 11% with their second drug, and less than 3% with their third monotherapy or with combination of two drugs [75, 76]. In children, the response to medication is more favorable. Carpay et al. found that 51% of children whose first medication failed for lack of efficacy had a good response to a second agent [77]. However, the likelihood of achieving a remission of longer than one year with subsequent drug regimens was only 29% after two medications failed, and 10% after three medications failed. In a separate study by Berg et al., among children whose seizures persisted despite trials of two AEDs, only 38% achieved a 1-year remission and 23% achieved a 3-year remission at last contact [78]. In children with cryptogenic or symptomatic focal epilepsy, the outcome may be more concerning; only 29% of children became seizure-free with a second monotherapy trial [79].

6.2. Surgical Management

Patients with medically refractory TLE should be evaluated expediently for surgical management, given the poor prognosis with additional medication trials. Hippocampal sclerosis and dual pathology (hippocampal sclerosis and other lesion) were associated with only 11% and 3% seizure freedom at last followup in medically treated cases, respectively [80, 81]. Early surgical intervention is also warranted, as long-term AED use carries risks such as osteopenia and osteoporosis, menstrual irregularities, sexual dysfunction, reduced fertility, cardiovascular illness, and drug-drug interactions. Furthermore, children undergoing temporal lobectomy for intractable epilepsy show improvement in visual memory and attentional functions [82] and quality of life, with complication rates less than 5% [83]. However, successful surgery for epilepsy is dependent upon correctly identifying the ictal-onset zone. Therefore, careful presurgical evaluation is necessary.

6.2.1. Presurgical Evaluations

Prolonged Video EEG —

Ictal scalp EEG monitoring is essential for determining region of seizure onset, especially differentiating mesial versus neocortical onset. This is important for seizure localization as well as having prognostic implications. Patients with mesial TLE may have higher seizure-free outcomes with surgery compared to patients with neocortical temporal and extratemporal lobe epilepsies, particularly if a single MRI lesion is present [84].

Although patients with TLE can have seizures without scalp-recorded ictal EEG patterns, due to insufficient source area (<10 cm2) and lack of synchrony to be detected as ictal activation, this is uncommon [85]. There are several EEG differences that can be identified between mesial- and neocortical-onset temporal seizures.

Distinguishing EEG features of lateral neocortical-onset temporal lobe seizures include a transitional sharp wave [86], as well as irregular ≤5 Hz, or repetitive epileptiform activities at ictal onset [87]. Using simultaneously scalp and intracranial recordings among patients with TLE, intermittent rhythmic delta slowing was highly correlated with the irritative and seizure-onset zones in patients with neocortical temporal epilepsy but poorly correlated with the irritative seizure-onset zone in patients with mesial TLE. The presence of intermittent rhythmic delta slowing among patients with mesial TLE likely represents epileptogenic propagation involving the temporal neocortex [88].

Imaging Modalities —

Neuroimaging is also important for presurgical evaluation, as patients with lesional TLE, such as hippocampal sclerosis or foreign tissue lesions (tumor, vascular anomaly), have a higher probability of seizure freedom after resection than those with normal MRI [89]. Postsurgical seizure-free outcome is seen in 70% to 90% patients with mesial TLE with hippocampal sclerosis compared to lowered seizure-free outcome of 60% in patients with nonlesional TLE [84].

MRI of the brain with seizure protocol includes images oriented in the oblique coronal plane, perpendicular to the long axis of the hippocampal structures [90]. Hippocampal atrophy and T2 signal abnormality seen on fluid-attenuated inversion recovery sequences are suggestive of mesial temporal sclerosis (Figure 4(b)). However, T2 hyperintensity alone in the hippocampus should not be assumed to be the epileptogenic zone because up to 47.5% of healthy volunteers without epilepsy have unilateral or bilateral hippocampal T2 hyperintensity [91]. Quantitative volumetric studies can be helpful in assessing the hippocampal atrophy, particularly when there is a question of bilateral atrophy or hippocampal malrotation [92].

In addition to MRI, multimodality noninvasive imaging techniques are increasingly used to determine the presumed epileptogenic focus when the scalp EEG and MRI are nonlocalizing or normal. These include subtraction ictal SPECT coregistered to MRI (SISCOM), positron emission tomography (PET), magnetoencephalography (MEG), and magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS).

SISCOM is a noninvasive modality to determine the epileptogenic lesion. Intensity differences more than two standard deviations between interictal and ictal images are coregistered onto the individual patient's MRI [93]. This technique produces semiquantitative maps of cerebral perfusion differences between ictal and interictal states and places that information in the context of the patient's own anatomy. The ability of SISCOM to detect epileptogenic lesions is 88% as compared to 39% by ictal SPECT alone [94]. Bell et al. demonstrated that SISCOM abnormality localized to the resection site is predictive of seizure-free outcome among patients with MRI negative TLE [84].

PET is a measure of glucose metabolism using 18 fluorodeoxyglucose. During the interictal state, glucose hypometabolism or reduced glucose uptake is present in the epileptogenic zone. In patients with TLE and normal MRI, unilateral PET hypometabolism has a positive predictive value between 70 and 80% [95]. However, it provided no additional information for patients with localizing ictal scalp EEG findings and concordant MRI.

Among patients with mesial TLE, magnetoencephalogram (MEG) may provide additional localizing information in up to 50% to 60% of patients with nonlocalizing ictal scalp EEG [96, 97]. On proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS), decreased N-acetyl aspartate over creatine ratios is seen ipsilateral to spikes in patients with TLE with or without an MRI-evident lesion [98–100]. Similarly, in children with intractable TLE, decreased N-acetyl aspartate over choline plus creatine ratio is correctly lateralized to the side of seizure focus in 55% of cases [101].

Testings for Language and Verbal Memory Lateralization —

Determination of the dominant hemisphere involved in language and verbal memory is important for presurgical counseling regarding the potential surgical risks. This is typically done through a combination of neuropsychological assessment, intracarotid sodium amobarbital testing, and functional MRI. Neuropsychological assessment prior to pediatric epilepsy surgery includes age-appropriate, standardized tests to evaluate multiple domains: intelligence, language, memory, attention, problem-solving/executive function, visuospatial and perceptual analysis and reasoning, academic skills, motor and sensory function, behavior, personality, emotional status, and adaptive functioning [102]. Such testing identifies areas of existing dysfunction, assists in determining language lateralization, and provides guidance in weighing the risks and benefits of surgery.

While Camfield et al. did not find a specific pattern of impairment in children [103], other studies have noted a similar pattern of memory deficits to what is seen in adults. In 22 right-handed children with intractable TLE, verbal memory dysfunction was worst among children with left foci compared to those with right foci and controls, whereas nonverbal dysfunction was most prominent among children with right foci [102].

In a large study from Germany, pediatric TLE was shown to have long-lasting impact on verbal learning and memory. Compared to controls, children and teens with epilepsy failed to build up an adequate learning and memory performance in their early years, hit their learning peak at a younger age, and reached poor performance levels at a younger age [104]. Furthermore, atypical language lateralization is seen among 12% of epilepsy patients, particularly among those with congenital lesions or left hemispheric insult before the age of 6 years [51, 105].

Intracarotid sodium amobarbital testing (Wada test) is used to determine language lateralization and to screen for verbal memory dominance. Among children who underwent temporal lobectomy, better verbal memory performance after injection ipsilateral to the side of surgery than after contralateral injection (Wada memory asymmetries) predicted preserved postoperative verbal memory capacity [106]. The difficulty of Wada testing in children is cooperation. However, Szabo and Wyllie found that using pretest teaching, emotional preparation, and simplified test items, up to 96% of children, including those with borderline intelligence and moderate mental retardation, could complete at least one injection [107]. Those at greater risk of poor cooperation included children with full-scale IQ <80, age <10 years, and seizures arising from the dominant left hemisphere.

Functional MRI (fMRI) is a noninvasive option to determine language lateralization as well as identify patients at higher risk of verbal memory decline following surgery [108, 109]. In children, the preoperative neuropsychologic testing may identify those who can successfully comply and participate in the functional mapping procedures. If neither Wada nor fMRI is feasible, language lateralization and verbal memory capacity may be determined by neuropsychologic testing.

6.2.2. Surgical Techniques

Once the presurgical evaluation is completed, surgical options are discussed. Classically, resection has been offered. However, less invasive, nonresective surgical techniques are potential treatment options, but need further study.

Resective Surgery —

There are two resective surgical options for mesial TLE. The first is standard anterior temporal resection or “anterior temporal lobectomy.” The resection line extends 4 to 5 cm from the temporal pole in the nondominant hemisphere and 3.5 cm to 4 cm in the dominant hemisphere. Standard anterior temporal lobectomy is preferred when seizure onset occurs in the lateral temporal or neocortical regions. The second option is selective amygdalohippocampectomy, which is selective removal of the mesial temporal structures. One of the primary goals of selective amygdalohippocampectomy is to preserve neuropsychological outcome, but the evidence for this is equivocal, especially in children. Seizure outcome following selective amygdalohippocampectomy is poorer in children than adults, with seizure-free outcome reported in only 33% of children versus 71% of adults, likely due to a greater frequency of pathology outside the hippocampus in younger patients [110]. Furthermore, rates of verbal memory deterioration after left-sided operations have been shown to be low [111].

Lastly, in patients with a presumed epileptogenic lesion in the lateral temporal region, lesionectomy with or without additional hippocampectomy may be performed.

To aid in determination of the optimal resective procedure, intraoperative electrocorticography (ECoG) has been used to localize the irritative zone and guide extent of surgical resection. ECoG is unlikely to influence surgical resection in standard anterior temporal lobectomy in patients with mesial TLE with mesial temporal sclerosis. Among consecutive patients with mesial TLE who underwent standard anterior temporal lobectomy, 72% were seizure-free despite preresection ECoG showing active interictal discharges outside the area of planned resection in 48% [112]. In tailored temporal lobectomies, intraoperative hippocampal ECoG may guide the posterior extent of hippocampal resection. In 140 consecutive patients undergoing this procedure, McKhann et al. showed that removal of all ECoG confirmed epileptogenic hippocampal tissue, but not the size of resection, correlated with seizure-free outcome [113].

Although ECoG may be important in children with dual pathology to ensure complete resection of regions of cortical dysplasia, the intraoperative setting is limited by sampling time. ECoG epileptiform activities are exclusively interictal spikes, as seizures are rarely recorded. Success of epilepsy surgery depends on the resection of the ictal onset zone rather than resection of more restrictive irritative zone suggested by interictal spiking [114].

Complications of dominant temporal lobectomy include language and memory impairments, with naming and fluency deficits seen in 50% [115]. Verbal memory impairment depends on whether resection was done in the dominant hemisphere as well as preoperative level of function—those with higher preoperative function are more likely to show decline. Transient diplopia due to trochlear nerve palsy can occur in 1.5% of cases. Significant contralateral visual field deficits (such as those greater than 90 degrees requiring suspension of driver's license) are seen in about 35% of patients undergoing anterior temporal lobectomy, but approximately 38% of these patients experience improvement within the first year after surgery [116].

Failure of surgical intervention is a disappointment and challenge for the epilepsy treatment team. Seizure recurrence typically occurs within the first year of surgery [117]. Evaluations for additional surgical resection should be considered. Rarely, the presumed postresection seizures are actually nonepileptic in nature. Video EEG recording and clinical semiology may identify a small percentage of patients with nonepileptic seizures.

Nonresective Epilepsy Surgery —

Ablative surgery including radiofrequency and thermal ablation is currently under investigation. Seizure remission is delayed up to 9–12 months after stereotactic radiosurgery for mesial temporal lobe epilepsy, occurring around the time of vasogenic edema on MRI [118, 119]. The risks and benefits of this procedure compared to conventional surgery remain to be determined.

Intermittent stimulation of the vagus nerve using a vagal nerve stimulator is typically reserved for patients who are not amenable to or have failed to respond to resective surgery. Additional studies of the potential efficacy of deep brain stimulation or focal stimulation have been done in adults. Limited studies on deep brain stimulation of thalamic nuclei and hippocampi have demonstrated reduced seizure burden among adult patients [120, 121]. In the prospective, randomized, double-blind, parallel group stimulation of anterior nucleus of thalamus trial, sixty percent of the patient population had TLE. Subjects with seizure origin in one or both temporal regions had a median seizure reduction compared to baseline of 44.2% in the stimulated group versus a 21.8% reduction in subjects receiving control treatment [122]. For those patients with focal seizure onset that occurs in nonresectable cortex, a responsive neurostimulator, which uses seizure detection algorithms to trigger focal stimulation, is currently being studied in adults, but not yet in children [123].

7. Pathology

In many children with new-onset TLE, the etiology remains unknown despite careful neuroimaging. In a community-based cohort of 63 children with new-onset TLE, children fell into three etiological groups [7]. Group 1, which accounted for 16% of cases, had neuroimaging evidence of malformations or long-standing, nonprogressive tumors. Group 2, which accounted for 29% of the cohort, had hippocampal sclerosis or a history of a significant antecedent event, such as focal or prolonged febrile seizure or intracranial infection. Finally, the third group, which accounted for the majority (54%) of cases, had normal neuroimaging and no significant past history. This group was termed cryptogenic.

In surgical series, there are two features that distinguish TLE in children from that of adults. Firstly, the prevalence of hippocampal sclerosis is significantly lower [124]. While this is the sole pathological feature found in two-thirds of surgically treated adult cases, in pediatric series, tumors and malformations of cortical development are more common. Secondly, in children, if hippocampal sclerosis is present, it is frequently associated with extrahippocampal pathology such as cortical dysplasia or low-grade tumors. Such dual pathology has been reported between 31 and 79% of all cases of mesial temporal sclerosis in children [15, 124–126]. Several possible mechanisms could explain this dual pathology. Firstly, factors resulting in cortical dysplasia may also interfere with the development of the hippocampus and its connections. Several authors have reported on the existence of amygdalohippocampal neuronal dysplasia in such children, using the term “dysgenetic mesial temporal sclerosis” [15, 127]. Alternatively, the extrahippocampal lesion could, in itself, predispose the hippocampal neurons to seizure-induced neuronal loss.

Several recent studies have reported on hippocampal malrotation (HIMAL) in a proportion of children with epilepsy [128, 129]. HIMAL results from failure of inversion of the hippocampus within the medial temporal lobe which occurs normally in fetal development and appears to be a rare finding in patients without seizures [130]. Lewis et al. reported a higher frequency of this finding in children with prolonged febrile seizures, indicating that it may play a role in temporal lobe epileptogenesis [129]. However, no study has focused exclusively on this finding in a cohort of children with TLE.

The association between prolonged febrile seizures, acute injury to the hippocampus with resultant hippocampal sclerosis, and intractable temporal lobe epilepsy remains controversial [131], and the frequency of this association is currently being investigated by the ongoing FEBSTAT study.

8. Outcomes

8.1. Seizure Outcome

Long-term seizure outcome in TLE is primarily affected by the underlying etiology. Harvey found that over half of children in his new-onset cohort were cryptogenic [7]. In a recently published population-based, long-term follow-up study of outcomes in nonidiopathic focal epilepsy of childhood, those with a cryptogenic etiology fared much more favorably than the symptomatic group, with lower rates of intractable epilepsy (7% versus 40%, P < 0.001), higher rates of seizure freedom (81% versus 55%, P < 0.001), and higher rates of medication freedom in those who were seizure-free at final followup (68% versus 46%, P = 0.01) [131]. However, some of these cryptogenic cases likely had a form of familial TLE.

Children with neuroimaging abnormalities including low-grade tumors, cortical dysplasia, or mesial temporal sclerosis have a significantly higher likelihood of medical intractability and should be considered early for resective surgery. A recent paper summarized outcomes in children undergoing temporal lobectomy reporting seizure-free rates of 58–78% with mesial temporal sclerosis, and in 60–91% of neocortical temporal resections [132]. Children with dual pathology do not appear to have a poorer prognosis than those with mesial temporal sclerosis alone, providing both the hippocampus and the additional epileptogenic lesion are resected. Failure to resect the second lesion may explain part of the surgical failure rate following surgery for pediatric mesial temporal sclerosis, and as such, selective amygdalohippocampectomy is likely to be less successful in children [110]. Lack of an obvious imaging abnormality or presence of diffuse pathology is predictive of higher rates of recurrence [89].

Following surgery, the steepest decline in the proportion of patients who remain seizure-free is seen in the first postoperative year. However, several long-term studies have identified a risk of late relapse [133, 134]. Jarrar et al. reported that 40% of subjects who were seizure-free at 5 years had recurrence of seizures at the 15-year-follow-up point [133].

8.2. Cognition and Memory

In adults with TLE, cognitive concerns are common, with left-sided foci being associated with deficits in verbal memory and right-sided foci with visual memory problems. However, when chronic TLE begins in childhood, the impact on cognition appears much more significant [135]. In a study which compared neuropsychological testing and quantitative MRI volumetrics in patients with childhood onset chronic TLE, adult onset chronic TLE, and healthy controls, Hermann et al. found the most significant neuropsychological abnormalities in the childhood onset group. Furthermore, in that group, cognitive compromise was widespread and not just limited to memory function, and MRI studies showed significant reductions in volumetric measurements of total cerebrum tissue and total white-matter volumes, consistent with the generalized nature of the cognitive deficits. These findings suggested that early-onset temporal lobe seizures and their treatment and/or factors leading to their development have significant impact on brain regions distant from the region of primary epileptogenesis.

A recent review of neuropsychological outcomes after epilepsy surgery, predominantly based on adult studies, showed specific cognitive changes, such as risk to verbal memory with left-sided surgery but noted that cognitive improvements may also be seen in some patients [136]. Most studies in children suggest greater functional recovery following temporal lobectomy than is seen in adults [82, 137]. In a multicenter study of 82 children less than 17 years at time of surgery, children undergoing left temporal lobectomy overall demonstrated no significant loss in verbal intellectual functioning and significant improvements in nonverbal intellectual functioning. Those undergoing right temporal lobectomy had no overall change in intellectual functioning [138]. However, analysis of individual changes showed that significant changes were seen in verbal functioning in 19% of cases (10% declined, 9% improved), and in nonverbal functioning in 18% (2% declined, 16% improved). Predictors of significant decline included older age at the time of surgery and structural lesions other than mesial temporal sclerosis. In most other studies, factors predictive of postoperative decline in verbal memory include left-sided surgery and higher baseline verbal IQ [137, 139, 140].

Historically, many studies in children have been limited by a relatively short postoperative followup and/or low patient number. Skirrow et al. recently reported on long-term followup of 42 children undergoing temporal lobectomy for intractable epilepsy and compared them to nonsurgical controls [141]. Children were followed for a mean of 9 postoperative years; 86% were seizure-free and 57% off antiepileptic medication. The mean full-scale IQ improved significantly in surgical patients but remained relatively unchanged in controls, with a gain of ten or more IQ points seen in 41% of surgical patients. However, this increase in IQ was only seen after a follow-up period of 6 years or longer and was associated with cessation of antiepileptic drugs and increased brain grey matter volume on MRI. Those with lower IQs showed the most significant improvement. This study highlights that surgery for intractable TLE in children results in favorable cognitive outcome, but that a prolonged period may be required for this recovery and subsequent development.

8.3. Psychiatric Conditions

Children with epilepsy are known to be at higher risk of comorbid psychiatric disorders [142–144], and those with intractable focal seizures may be most vulnerable. In a cohort of children with complex partial seizures, Ott et al. demonstrated psychopathology in 52%, and those with lower IQ were at higher risk [145].

McLellan et al. assessed the rate and nature of psychiatric disorders in a cohort of children undergoing temporal lobectomy and then reevaluated this cohort postoperatively. One or more psychiatric disorders were found in 72% of children preoperatively, but also in an equivalent number postoperatively. Only 16% of children had resolution of their mental health problems after surgery; however, 12% without a preoperative psychiatric diagnosis developed mental health problems after temporal lobectomy [146]. The most common preoperative diagnoses were pervasive developmental delay (38%), ADHD (23%), oppositional defiant disorder (23%), and disruptive behavior disorder, not otherwise specified (42%). While pervasive developmental delay was more common with younger age at seizure onset and a right temporal focus, no other biological predictors were found for any other psychiatric conditions. Surprisingly, this study found no clear relationship between seizure freedom postoperatively and psychopathology. However, other studies have shown reduction in behavior and psychiatric problems following epilepsy surgery in children [147, 148], and further work focusing on children undergoing temporal lobectomy is needed.

Mizrahi et al. assessed whether a delay in surgery impacted psychosocial functioning in children with temporal lobe epilepsy [149]. Higher rates of psychosocial, behavioral, and educational difficulties in those undergoing later versus earlier surgery were found, suggesting that early surgery may ameliorate some of these difficulties.

9. Conclusion

Although TLE is less common in children than adults, it still comprises a significant portion of pediatric epilepsy. Seizures arising from the temporal lobe can be difficult to identify based on semiology alone, particularly in younger children. Up to the age of 6 years, the traditional semiologic hallmarks of TLE in adults (including auras, automatisms, posturing, and head version) are less likely to be observed. Correct diagnosis often necessitates routine or prolonged EEG recordings. Although the interictal EEG hallmarks of TLE (including temporal spike or sharp-wave discharges and TIRDA) are classically seen in older children, young children may present with generalized or multiregional epileptiform discharges, further complicating diagnosis. Once identified, additional workup is warranted to determine if childhood TLE is lesional (classically low-grade tumors, cortical dysplasia, or mesial temporal sclerosis) or nonlesional (including autosomal dominant lateral TLE, idiopathic partial epilepsy with auditory features, familial mesial TLE, and partial reading epilepsy). Care must be taken to differentiate TLE from other conditions in which there is significant activation of spike-wave discharges during sleep, including LKS, CSWS, and BCECTS.

While the majority of children with TLE will achieve seizure freedom with AEDs alone, a significant minority will prove medically intractable. This is especially true when seizures are symptomatic of an underlying lesion. For children with TLE who fail two or more AEDs because of lack of efficacy, expedited epilepsy surgery evaluations are warranted. In addition to prolonged video EEG and MRI, SISCOM, PET, and MEG can be successfully utilized in this population to identify appropriate surgical candidates. Given the greater likelihood of pathology outside the hippocampus in younger patients (including low grade tumors and cortical dysplasia), standard temporal lobectomy (versus selective amygdalohippocampectomy) may portend better outcome. Such intervention can be associated with seizure-free rates as high as 58–91% and improved neuropsychological outcomes. Given the significant morbidity associated with uncontrolled childhood TLE, further research into the efficacy of other interventions (such as radiofrequency/thermal ablation, stimulation of the anterior nucleus of thalamus, and responsive neurostimulation) is warranted.

References

- 1.Wirrell EC, Grossardt BR, Wong-Kisiel LCL, Nickels KC. Incidence and classification of new-onset epilepsy and epilepsy syndromes in children in Olmsted county, Minnesota from 1980 to 2004: a population-based study. Epilepsy Research. 2011;95(1-2):110–118. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2011.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Camfield CS, Camfield PR, Gordon K, Wirrell E, Dooley JM. Incidence of epilepsy in childhood and adolescence: a population-based study in Nova Scotia from 1977 to 1985. Epilepsia. 1996;37(1):19–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1996.tb00506.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adelöw C, Åndell E, Åmark P, et al. Newly diagnosed single unprovoked seizures and epilepsy in Stockholm, Sweden: first report from the Stockholm incidence registry of epilepsy (SIRE) Epilepsia. 2009;50(5):1094–1101. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.01726.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blom S, Heijbel J, Bergfors PG. Incidence of epilepsy in children: a follow-up study three years after the first seizure. Epilepsia. 1978;19(4):343–350. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1978.tb04500.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Christensen J, Vestergaard M, Pedersen MG, Pedersen CB, Olsen J, Sidenius P. Incidence and prevalence of epilepsy in Denmark. Epilepsy Research. 2007;76(1):60–65. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2007.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Doose H, Sitepu B. Childhood epilepsy in a German city. Neuropediatrics. 1983;14(4):220–224. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1059582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Simon Harvey A, Berkovic SF, Wrennall JA, Hopkins LJ. Temporal lobe epilepsy in childhood: clinical, EEG, and neuroimaging findings and syndrome classification in a cohort with new-onset seizures. Neurology. 1997;49(4):960–968. doi: 10.1212/wnl.49.4.960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cascino GD. Surgical treatment for epilepsy. Epilepsy Research. 2004;60:179–186. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2004.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ray A, Kotagal P. Temporal lobe epilepsy in children: overview of clinical semiology. Epileptic Disorders. 2005;7(4):299–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fogarasi A, Tuxhorn I, Janszky J, et al. Age-dependent seizure semiology in temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2007;48(9):1697–1702. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.01129.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fogarasi A, Jokeit H, Faveret E, Janszky J, Tuxhorn I. The effect of age on seizure semiology in childhood temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2002;43(6):638–643. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2002.46801.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bourgeois BF. Temporal lobe epilepsy in infants and children. Brain and Development. 1998;20(3):135–141. doi: 10.1016/s0387-7604(98)00010-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brockhaus A, Elger CE. Complex partial seizures of temporal lobe origin in children of different age groups. Epilepsia. 1995;36(12):1173–1181. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1995.tb01059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Terra-Bustamante VC, Inuzuca LM, Fernandes RM, et al. Temporal lobe epilepsy surgery in children and adolescents: clinical characteristics and post-surgical outcome. Seizure. 2005;14(4):274–281. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2005.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bocti C, Robitaille Y, Diadori P, et al. The pathological basis of temporal lobe epilepsy in childhood. Neurology. 2003;60(2):191–195. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000044055.73747.9f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cavalheiro EA, Silva DF, Turski WA, Calderazzo-Filho LS, Bortolotto ZA, Turski L. The susceptibility of rats to pilocarpine-induced seizures is age-dependent. Brain Research. 1987;465(1-2):43–58. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(87)90227-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cherubini E, de Feo MR, Mecarelli O, Ricci GF. Behavioral and electrographic patterns induced by systemic administration of kainic acid in developing rats. Brain Research. 1983;285(1):69–77. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(83)90110-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holmes GL. Epilepsy in the developing brain: lessons from the laboratory and clinic. Epilepsia. 1997;38(1):12–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1997.tb01074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moshe SL. The effects of age on the kindling phenomenon. Developmental Psychobiology. 1981;14(1):75–81. doi: 10.1002/dev.420140110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kakisaka Y, Haginoya K, Ishitobi M, et al. Utility of subtraction ictal SPECT images in detecting focal leading activity and understanding the pathophysiology of spasms in patients with west syndrome. Epilepsy Research. 2009;83(2-3):177–183. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2008.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chugani HT, Shewmon DA, Sankar R, Chen BC, Phelps ME. Infantile spasms: II. Lenticular nuclei and brain stem activation on positron emission tomography. Annals of Neurology. 1992;31(2):212–219. doi: 10.1002/ana.410310212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Acharya JN, Wyllie E, Lüders HO, Kotagal P, Lancman M, Coelho M. Seizure symptomatology in infants with localization-related epilepsy. Neurology. 1997;48(1):189–196. doi: 10.1212/wnl.48.1.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Olbrich A, Urak L, Gröppel G, et al. Semiology of temporal lobe epilepsy in children and adolescents value in lateralizing the seizure onset zone. Epilepsy Research. 2002;48(1-2):103–110. doi: 10.1016/s0920-1211(01)00326-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wyllie E, Chee M, Granstrom ML, et al. Temporal lobe epilepsy in early childhood. Epilepsia. 1993;34(5):859–868. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1993.tb02103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fontana E, Negrini F, Francione S, et al. Temporal lobe epilepsy in children: electroclinical study of 77 cases. Epilepsia. 2006;47(supplement s5):26–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2006.00873.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oller-Daurella L, Oller LF. Partial epilepsy with seizures appearing in the first three years of life. Epilepsia. 1989;30(6):820–826. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1989.tb05345.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Villanueva V, Serratosa JM. Temporal lobe epilepsy: clinical semiology and age at onset. Epileptic Disorders. 2005;7(2):83–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tuxhorn I, Holthausen H, Boenigk H, editors. Paediatric Epilepsy Syndromes and Their Surgical Treatment. London, UK: John Libbey and Company Ltd; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Feichtinger M, Pauli E, Schäfer I, et al. Ictal fear in temporal lobe epilepsy: surgical outcome and focal hippocampal changes revealed by proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy imaging. Archives of Neurology. 2001;58(5):771–777. doi: 10.1001/archneur.58.5.771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Clarke DF, Otsubo H, Weiss SK, et al. The significance of ear plugging in localization-related epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2003;44(12):1562–1567. doi: 10.1111/j.0013-9580.2003.34103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vendrame M, Zarowski M, Alexopoulos AV, Wyllie E, Kothare SV, Loddenkemper T. Localization of pediatric seizure semiology. Clinical Neurophysiology. 2011;122(10):1924–1928. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kotagal P, Luders H, Morris HH, et al. Dystonic posturing in complex partial seizures of temporal lobe onset: a new lateralizing sign. Neurology. 1989;39(2):196–201. doi: 10.1212/wnl.39.2.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peppercorn MA, Herzog AG. The spectrum of abdominal epilepsy in adults. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 1989;84(10):1294–1296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moseley BD, Wirrell EC, Nickels K, Johnson JN, Ackerman MJ, Britton J. Electrocardiographic and oximetric changes during partial complex and generalized seizures. Epilepsy Research. 2011;95(3):237–245. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2011.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mayer H, Benninger F, Urak L, Plattner B, Geldner J, Feucht M. EKG abnormalities in children and adolescents with symptomatic temporal lobe epilepsy. Neurology. 2004;63(2):324–328. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000129830.72973.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moseley BD, Nickels K, Britton J, Wirrell E. How common is ictal hypoxemia and bradycardia in children with partial complex and generalized convulsive seizures? Epilepsia. 2010;51(7):1219–1224. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2009.02490.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Watanabe K, Hara K, Hakamada S, et al. Seizures with apnea in children. Pediatrics. 1982;70(1):87–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sperling MR, Engel J., Jr Electroencephalographic recording from the temporal lobes: a comparison of ear, anterior temporal, and nasopharyngeal electrodes. Annals of Neurology. 1985;17(5):510–513. doi: 10.1002/ana.410170515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Quesney LF. Extracranial EEG evaluation. In: Engel J Jr, editor. Surgical Treatment of the Epilepsies. New York, NY, USA: Raven Press; 1987. pp. 129–166. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sharbrough FW. Commentary: extracranial EEG monitoring. In: Engel J Jr, editor. Surgical Treatment of the Epilepsies. New York, NY, USA: Raven Press; 1987. pp. 167–171. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sharbrough FW. Electrical fields and recording techniques. In: Daly D, Pedley TA, editors. Current Practice of Clinical Electroencephalography. New York, NY, USA: Raven Press; 1990. pp. 29–49. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Westmoreland BF. The electroencephalogram in patients with epilepsy. In: Aminoff MJ, editor. Neurology Clinics. Philadelphia, Pa, USA: WB Saunders; 1985. pp. 599–613. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wyllie E, Lachhwani DK, Gupta A, et al. Successful surgery for epilepsy due to early brain lesions despite generalized EEG findings. Neurology. 2007;69(4):389–397. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000266386.55715.3f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gotman J, Marciani MG. Electroencephalographic spiking activity, drug levels, and seizure occurrence in epileptic patients. Annals of Neurology. 1985;17(6):597–603. doi: 10.1002/ana.410170612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Berg AT, Berkovic SF, Brodie MJ, et al. Revised terminology and concepts for organization of seizures and epilepsies: report of the ILAE commission on classification and terminology, 2005–2009. Epilepsia. 2010;51(4):676–685. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2010.02522.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Michelucci R, Pasini E, Nobile C. Lateral temporal lobe epilepsies: clinical and genetic features. Epilepsia. 2009;50(supplement 5):52–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2009.02122.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ottman R, Winawer MR, Kalachikov S, et al. LGI1 mutations in autosomal dominant partial epilepsy with auditory features. Neurology. 2004;62(7):1120–1126. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000120098.39231.6e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bisulli F, Tinuper P, Avoni P, et al. Idiopathic partial epilepsy with auditory features (IPEAF): a clinical and genetic study of 53 sporadic cases. Brain. 2004;127(6):1343–1352. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Crompton DE, Scheffer IE, Taylor I, et al. Familial mesial temporal lobe epilepsy: a benign epilepsy syndrome showing complex inheritance. Brain. 2010;133(11):3221–3231. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Maillard L, Vignal JP, Raffo E, Vespignani H. Bitemporal form of partial reading epilepsy: further evidence for an idiopathic localization-related syndrome. Epilepsia. 2010;51(1):165–169. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2009.02247.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Möddel G, Lineweaver T, Schuele SU, Reinholz J, Loddenkemper T. Atypical language lateralization in epilepsy patients. Epilepsia. 2009;50(6):1505–1516. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.02000.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Peltola ME, Liukkonen E, Granstrom ML, et al. The effect of surgery in encephalopathy with electrical status epilepticus during sleep. Epilepsia. 2011;52(3):602–609. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2010.02783.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nickels K, Wirrell E. Electrical status epilepticus in sleep. Seminars in Pediatric Neurology. 2008;15(2):50–60. doi: 10.1016/j.spen.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rossi PG, Parmeggiani A, Posar A, Scaduto MC, Chiodo S, Vatti G. Landau-Kleffner syndrome (LKS): long-term follow-up and links with electrical status epilepticus during sleep (ESES) Brain and Development. 1999;21(2):90–98. doi: 10.1016/s0387-7604(98)00071-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jayakar PB, Seshia SS. Electrical status epilepticus during slow-wave sleep: a review. Journal of Clinical Neurophysiology. 1991;8(3):299–311. doi: 10.1097/00004691-199107010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Galanopoulou AS, Bojko A, Lado F, Moshé SL. The spectrum of neuropsychiatric abnormalities associated with electrical status epilepticus in sleep. Brain and Development. 2000;22(5):279–295. doi: 10.1016/s0387-7604(00)00127-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nieuwenhuis L, Nicolai J. The pathophysiological mechanisms of cognitive and behavioral disturbances in children with Landau-Kleffner syndrome or epilepsy with continuous spike-and-waves during slow-wave sleep. Seizure. 2006;15(4):249–258. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2006.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sheth RD. Electroencephalogram in developmental delay: specific electroclinical syndromes. Seminars in Pediatric Neurology. 1998;5(1):45–51. doi: 10.1016/s1071-9091(98)80018-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tuchman RF, Rapin I. Regression in pervasive developmental disorders: seizures and epileptiform electroencephalogram correlates. Pediatrics. 1997;99(4):560–566. doi: 10.1542/peds.99.4.560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.McVicar KA, Shinnar S. Landau-Kleffner syndrome, electrical status epilepticus in slow wave sleep, and language regression in children. Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews. 2004;10(2):144–149. doi: 10.1002/mrdd.20028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tassinari CA, Rubboli G, Volpi L, et al. Encephalopathy with electrical status epilepticus during slow sleep or ESES syndrome including the acquired aphasia. Clinical Neurophysiology. 2000;111(supplement 2):S94–S102. doi: 10.1016/s1388-2457(00)00408-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tassinari CA, Michelucci R, Forti A, et al. The electrical status epilepticus syndrome. Epilepsy Research Supplement. 1992;6:111–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Perez ER. Syndromes of acquired epileptic aphasia and epilepsy with continuous spike-waves during sleep: models for prolonged cognitive impairment of epileptic origin. Seminars in Pediatric Neurology. 1995;2(4):269–277. doi: 10.1016/s1071-9091(95)80006-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.MacAllister WS, Schaffer SG. Neuropsychological deficits in childhood epilepsy syndromes. Neuropsychology Review. 2007;17(4):427–444. doi: 10.1007/s11065-007-9048-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Debiais S, Tuller L, Barthez MA, et al. Epilepsy and language development: the continuous spike-waves during slow sleep syndrome. Epilepsia. 2007;48(6):1104–1110. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.01015.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tuchman RF. Epilepsy, language, and behavior: clinical models in childhood. Journal of Child Neurology. 1994;9(1):95–102. doi: 10.1177/088307389400900124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.de Negri M. Electrical status epilepticus during sleep (ESES). Different clinical syndromes: towards a unifying view? Brain and Development. 1997;19(7):447–451. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tassinnari CA, Bureau M, Dravet C, Bernardina BD, Roger J. Epilepsy with continuous spikes and waves during slow sleep—otherwise described as ESES. In: Roger J, Bureau M, Dravet C, Dreifuss FE, Perret A, Wolf P, editors. Epileptic Syndromes in Infancy, Childhood and Adolescence. London, UK: John Libbey; 1992. pp. 245–256. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Beaumanoir A. EEG data. In: Beaumanoir A, Bureau M, Deonna T, Mira L, Tassinari CA, editors. Continuous Spikes and Waves During Slow Sleep. London, UK: John Libbey; 1995. pp. 217–223. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Smith MC, Hoeppner TJ. Epileptic encephalopathy of late childhood: Landau-Kleffner syndrome and the syndrome of continuous spikes and waves during slow-wave sleep. Journal of Clinical Neurophysiology. 2003;20(6):462–472. doi: 10.1097/00004691-200311000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Roger J, Dreifuss FE, Martinez-Lage M, et al. Proposal for revised classification of epilepsies and epileptic syndromes. Commission on classification and terminology of the international league against epilepsy. Epilepsia. 1989;30(4):389–399. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1989.tb05316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Willmore LJ, Ueda Y. Genetics of epilepsy. Journal of Child Neurology. 2002;17(supplement 1):S18–S27. doi: 10.1177/08830738020170010301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Panayiotopoulos CP, Michael M, Sanders S, Valeta T, Koutroumanidis M. Benign childhood focal epilepsies: assessment of established and newly recognized syndromes. Brain. 2008;131(9):2264–2286. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.French JA, Kanner AM, Bautista J, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of the new antiepileptic drugs II: treatment of refractory epilepsy: report of the therapeutics and technology assessment subcommittee and quality standards subcommittee of the American academy of neurology and the American epilepsy society. Neurology. 2004;62(8):1261–1273. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000123695.22623.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kwan P, Brodie MJ. Early identification of refractory epilepsy. New England Journal of Medicine. 2000;342(5):314–319. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200002033420503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Mohanraj R, Brodie MJ. Diagnosing refractory epilepsy: response to sequential treatment schedules. European journal of neurology. 2006;13(3):277–282. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2006.01215.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Carpay HA, Arts WF, Geerts AT, et al. Epilepsy in childhood: an audit of clinical practice. Archives of Neurology. 1998;55(5):668–673. doi: 10.1001/archneur.55.5.668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Berg AT, Levy SR, Testa FM, d’Souza R. Remission of epilepsy after two drug failures in children: a prospective study. Annals of Neurology. 2009;65(5):510–519. doi: 10.1002/ana.21642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Elkis LC, Bourgeois BFD, Wyllie E, Kotagal P. Efficacy of second antiepileptic drug after failure of one drug in children with partial epilepsy. Epilepsia. 1993;34(supplement 6):107 pages. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Semah F, Picot MC, Adam C, et al. Is the underlying cause of epilepsy a major prognostic factor for recurrence? Neurology. 1998;51(5):1256–1262. doi: 10.1212/wnl.51.5.1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Dlugos DJ. The early identification of candidates for epilepsy surgery. Archives of Neurology. 2001;58(10):1543–1546. doi: 10.1001/archneur.58.10.1543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gleissner U, Sassen R, Schramm J, Elger CE, Helmstaedter C. Greater functional recovery after temporal lobe epilepsy surgery in children. Brain. 2005;128(12):2822–2829. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sinclair DB, Aronyk KE, Snyder TJ, et al. Pediatric epilepsy surgery at the University of Alberta: 1988–2000. Pediatric Neurology. 2003;29(4):302–311. doi: 10.1016/s0887-8994(03)00307-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Bell ML, Rao S, So EL, et al. Epilepsy surgery outcomes in temporal lobe epilepsy with a normal MRI. Epilepsia. 2009;50(9):2053–2060. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2009.02079.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Tao JX, Baldwin M, Hawes-Ebersole S, Ebersole JS. Cortical substrates of scalp EEG epileptiform discharges. Journal of Clinical Neurophysiology. 2007;24(2):96–100. doi: 10.1097/WNP.0b013e31803ecdaf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Azar NJ, Lagrange AH, Abou-Khalil BW. Transitional sharp waves at ictal onset—a neocortical ictal pattern. Clinical Neurophysiology. 2009;120(4):665–672. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2009.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ebersole JS, Pacia SV. Localization of temporal lobe foci by ictal EEG patterns. Epilepsia. 1996;37(4):386–399. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1996.tb00577.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Tao JX, Chen XJ, Baldwin M, et al. Interictal regional delta slowing is an EEG marker of epileptic network in temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2011;52(3):467–476. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2010.02918.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.McIntosh AM, Kalnins RM, Mitchell LA, Fabinyi GC, Briellmann RS, Berkovic SF. Temporal lobectomy: long-term seizure outcome, late recurrence and risks for seizure recurrence. Brain. 2004;127(9):2018–2030. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Woermann FG, Vollmar C. Clinical MRI in children and adults with focal epilepsy: a critical review. Epilepsy and Behavior. 2009;15(1):40–49. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2009.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Labate A, Gambardella A, Aguglia U, et al. Temporal lobe abnormalities on brain MRI in healthy volunteers: a prospective case-control study. Neurology. 2010;74(7):553–557. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181cff747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Cascino GD. Clinical correlations with hippocampal atrophy. Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 1995;13(8):1133–1136. doi: 10.1016/0730-725x(95)02023-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.O’Brien TJ, So EL, Mullan BP, et al. Subtraction SPECT co-registered to MRI improves postictal SPECT localization of seizure loci. Neurology. 1999;52(1):137–146. doi: 10.1212/wnl.52.1.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.So EL. Integration of EEG, MRI, and SPECT in localizing the seizure focus for epilepsy surgery. Epilepsia. 2000;41(supplement 3):S48–S54. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.2000.tb01534.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Willmann O, Wennberg R, May T, Woermann FG, Pohlmann-Eden B. The contribution of 18F-FDG PET in preoperative epilepsy surgery evaluation for patients with temporal lobe epilepsy. A meta-analysis. Seizure. 2007;16(6):509–520. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kaiboriboon K, Nagarajan S, Mantle M, Kirsch HE. Interictal MEG/MSI in intractable mesial temporal lobe epilepsy: spike yield and characterization. Clinical Neurophysiology. 2010;121(3):325–331. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2009.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Pataraia E, Lindinger G, Deecke L, Mayer D, Baumgartner C. Combined MEG/EEG analysis of the interictal spike complex in mesial temporal lobe epilepsy. NeuroImage. 2005;24(3):607–614. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Shih JJ, Weisend MP, Lewine J, Sanders J, Dermon J, Lee R. Areas of interictal spiking are associated with metabolic dysfunction in MRI-negative temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2004;45(3):223–229. doi: 10.1111/j.0013-9580.2004.13503.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Shih JJ, Weisend MP, Sanders JA, Lee RR. Magnetoencephalographic and magnetic resonance spectroscopy evidence of regional functional abnormality in mesial temporal lobe epilepsy. Brain Topography. 2010;23(4):368–374. doi: 10.1007/s10548-010-0156-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Series W, Li LM, Caramanos Z, Arnold DL, Gotman J. Relation of interictal spike frequency to 1H-MRSI-measured NAA/Cr. Epilepsia. 1999;40(12):1821–1827. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1999.tb01605.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Cross JH, Connelly A, Jackson GD, Johnson CL, Neville BG, Gadian DG. Proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy in children with temporal lobe epilepsy. Annals of Neurology. 1996;39(1):107–113. doi: 10.1002/ana.410390116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]